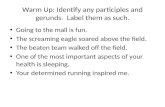

From participles to gerunds

Transcript of From participles to gerunds

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.1 (46-124)

From participles to gerunds*

Io Manolessou

El gerundio llegó a ser un tumor maligno en el cuerpo del idioma. . .Muñío Valverde (1995:9)

This article examines the passage from the inflected Ancient Greek (AG) activeparticiple to the uninflected Modern Greek (MG) active gerund, by offering asynchronic morphological and syntactic description period-by-period. It claimsis that this evolution can be satisfactorily explained only if set in a wider context,taking into account (a) similar evolutions in other languages, namely, the passagefrom partiple to gerund in Romance, Slavic and Baltic and (b) other evolutionsinvolving the participle within Greek, namely, the transformation of the Greekpassive participle into a nominal (adjectival) category. The change is interpretedas the split of a “mixed” category (the participle), possessing both verbal andnominal features, to a purely verbal category (the active gerund) and a purelynominal one (the passive participle).

. Introduction

The present paper investigates the transition from the complex AG participle system,which involves full nominal agreement (gender, number, case), multiple tenses and 3voices (active, middle and passive), to the MG system, where the active voice possessesonly an indeclinable gerund.1 It also proposes a general, cross-linguistic motivation forparticiple evolution, and sets down the implications of historical research for currenttheoretical approaches to Greek gerunds.

The MG gerund is quite different from the English one,2 and therefore, the largestpart of current research on the syntax of gerunds is irrelevant to it. Similarly, there is agap in the research on the historical evolution of the Greek gerund as well,3 since mostof the work done is now several decades old, not extensive and in some cases factuallyinaccurate or lacking a theoretical framework.

The main claim in this paper is that gerund evolution in Greek can be properlyinterpreted only if viewed in a wider context, and not examined as an isolated phe-nomenon. What must also be taken into account is (a) similar evolutions in otherlanguages and (b) other evolutions involving the participle within Greek.

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.2 (124-180)

Io Manolessou

Section 2 gives a stage-by-stage account of the parallel evolutions of the gerundand the passive participle, and Section 3 a short exposition of similar developments inother languages. In Section 4 the various theories concerning the development of theMG gerund are evaluated. Finally, in Section 5 the theoretical implications of the dataare set out.

. The data and the historical process of development

What follows is an overview of the developments leading from the AG to the MGparticipial system in a series of stages/steps, from both a morphological and a syntacticviewpoint. This hopes to supplement the only available information until now, whichcomes either from a limited set of examples in standard Grammars or the at timesinaccurate account by the only comprehensive article on the topic, Mirambel (1961).

It should be noted that in order to acquire a secure picture of the linguistic sit-uation in each period – especially of the earlier stages, where the origins of the de-velopment are to be sought – scanning of large textual samples would be desirable,for checking the distribution of the various alternative morphological and syntacticoptions. Unfortunately, such data are unavailable,4 and their collection goes muchbeyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, an effort was made to back up thedescription with substantial cross-checking from texts.

. Stage 1 – Ancient Greek

MorphologyAG has two types of participle: active (consonant-stem) and middle/passive (o-stem),both fully inflected for gender, number and case, and also indicating aspect and tense.5

The active participle shows a tendency to imitate the large sub-classes of consonant-stem adjectives which have a common form for both masculine and feminine, andto exhibit the same usage. This is shown by Rupprecht (1926), Langholf (1977) andPetersmann (1979), who examine the appearance of masculine forms of the participlewith feminine subjects in Classical and Post-Classical authors, (1):

(1) a. Khlo:raigreen

deptcl

skiadestesters.nom.pl.fem

brithontesabounding.nom.pl.masc.act

anne:thou.dill‘And leafy testers well-dressed with dill.’ (Theocr.Idyll.15.119)

b. Hepta. . .seven. . .

pyra:n. . .funeral.pyres.gen.pl.fem . . .

telesthento:n.having.been consumed.gen.pl.masc.act‘When the seven funeral pyres had been consumed.’ (Pind.Olymp.6.15)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.3 (180-241)

From participles to gerunds

This usage is especially frequent in the corpus Hippocraticum (5th–4th c BC) and caneasily be observed in the gynaecological treatises, where the subject is unambiguouslya woman and where the masculine form is very often used for the active participle butnever for the passive one (Langholf 1977:300–302), (2):

(2) a. Myrsine:smyrtle

phyllaleaves

embalo:n. . .having.placed.on.nom.sg.masc.act. . .

ito:.go.imper.3sg

prosto

tonthe

andra.man

‘Having placed myrtle leaves (on herself). . . let her go to the man.’(Hp.Mul.I.viii.168.11–12)

b. Rhidzasroots

anadzesa:s. . .having.boiled.nom.sg.masc.act

kaiand

lu:samene:. . .having.bathed.nom.sg.fem.mid.

ito:go.imper.3sg

prosto

tonthe

andraman

‘Having boiled roots. . . and bathed. . . let her go to the man.’(Hp.Steril.VIII.434.7–10)

Thus, what previous accounts usually consider a “first evidence” of indeclinability is afeature of spoken language,6 already present in AG.

SyntaxThe participle, both active and passive, has three uses (cf. Smyth 1965:454–479 andSchwyzer 1950:387–403 for details): attributive (adjectival modifier), complement (ofverbs), and adverbial (temporal, causal, manner, concessive, conditional, final etc).In all three cases it behaves like an adnominal modifier, agreeing in case, numberand gender with its subject (cf. (1) and (2)). The participle is either “conjoined”, ifits subject is co-referential with a constituent in the main clause, in which case theparticiple agrees with this constituent, or “absolute”, if its subject is unrelated with allconstituents of the main clause, in which case both the participle and its subject appearin the genitive case. Circumstantial participles can be introduced by a variety of con-junctions: temporal (hama), causal (hate, hoion, ho:s), final (ho:s), concessive (kaiper,kai tauta) etc.

. Stage 2 – Koine (NT & papyri)

MorphologyThe AG system is maintained in general, but papyri show frequent cases of mascu-line forms for feminine, and of occasional errors of formation (cf. Dieterich 1898:207;Mayser 1934:35, 194; Mandilaras 1973:353–358; Gignac 1981:131–132). Also, the pa-pyri often display the nominative form of the participle in preference to cases, some-thing which happens with other consonant stem adjectives as well (r-stems, s-stemsetc.). However, several of the examples of lack of agreement proposed by Grammars

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.4 (241-307)

Io Manolessou

(refs. above) are not true cases of lack of agreement, but instances of analogical re-formations of endings. For example, the masculine nominative plural ending [-es]instead of the accusative [-as] in the participle (e.g. autu:s. . . tithentes BGU.1122, 14–5,13 BC, tu:s philu:ntes P.Fay.119.26, 100 AD) is not a case of nominative being substi-tuted for the accusative, but of the new analogical accusative ending, which had begunto spread already in the Hellenistic period.7

Mirambel (1961:50) claims that the first stage of development is the disappearanceof inflection, followed only later by confusions of gender, something that is inexact. Asshown in 2.1, masculine forms in place of feminine ones are a feature of AG already,and, as will be described in 2.3, masculine forms instead of neuter ones (i.e., [-onta]instead of [-on]) are not a phenomenon of gender change, but of morphological inno-vation, i.e. a new neuter termination. Furthermore, some of his examples do not belongto this period at all (to:n riθen, ton sximatisθen quoted from Dieterich (1898:207) comefrom documents of the 12th c. AD). So in this period, participle inflection seems to berather well maintained.8

In order to acquire a clearer picture of the functioning of the participial system inthe papyri, a closer look at the primary data is required, as the standard Grammars of-fer no quantitative information concerning the frequency of “incorrect” usage, whichwould give one an idea of the extent to which the change was beginning to spread.

A search of two 3rd c. BC corpora, P.Cair.Zen I–IV and P.Hibeh I, which containboth official and private documents show that breaches of participial agreement arevery rare: among the hundreds of instances of participles occurring in the large corpusof these documents, one can hardly find 4–5 examples. These include: use of the mas-culine instead of the feminine form, (3a), appearance of the masc. nom. plural ending[-es] instead of acc. [-as] as described above, (3b), use of the participle instead of theinfinitive, (3c), and, once, use of the masc.nom.sing instead of the fem.acc.sing., (3d).

(3) a. To:nthe

aigo:ngoats.gen.pl.fem

tiktonto:n.giving.birth.gen.pl.masc.act

(P.Cair.Zen.59338.2)b. Ginoske. . .

know.2sg.impupotenever

eile:photeshaving.taken.nom.pl.masc.act

he:mas.we.acc.pl.masc

‘Know that we never took.’ (P.Cair.Zen.59343.7)c. Eneukhomai

1sg.pressoi. . .you.dat.sg. . . .

apheisleaving.nom.sg.masc.act

te:nthe

gynaikawife

mu.my‘I am ordering you. . . to leave my wife.’ (P.Cair.Zen.59482.5)

d. Apestalkasend.1.sg.perf

soiyou.dat.sg

te:nthe

gynaikawoman.acc.sg.fem

phero:nbringing.nom.sg.masc.act

soiyou.dat.sg

te:nthe

epistole:n.letteracc.sg

‘I have sent you the woman bringing you the letter.’ (P.Cair.Zen.59443.12)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.5 (307-375)

From participles to gerunds

On the contrary, the 2nd c. corpus of the Tebtunis papyri (P.Tebt.I and II) containsdozens of instances of failing agreement. A crucial point is that they do not con-cern only 3rd declensions participles, although, in the standard literature it is usuallyassumed that it is the difficult declension pattern of the 3rd declension (consonant-stem), that has caused the eventual fossilization of the active participle into thegerund, (4):

(4) a. Tothe

hypomne:mareport

epidedomenondelivered

paraby

Mestasytmios. . .Mestasytmis.gen.sg.masc. . .

hypiskhnu:menos.promising.nom.sg.masc‘The report delivered by Mestasytmis, promising. . . ’ (P.Tebt.58)

b. Ge:sland.gen.sg.fem

kle:rukhike:scleruchic

syno:rismene:n.bordered.acc.sg.fem.pass

‘Of cleruchic land, bordered. . . ’ (P.Tebt.82)

A comparison with another 2nd c. corpus, UPZ I and I.II, shows that this high fre-quency is rather above the norm; in the UPZ corpus breaches of agreement occur only5–6 times as well. Similarly, the papyrological specimens of the Christian era examined(Pap.Cair.Masp.I and III, BGU XV) contain very few instances of aberrant participialusage. The conclusion to be drawn from the above overview is that the image pre-sented by the papyri depends mainly on whether the writer’s native idiom is Greek (asin most of the Zenon and UPZ papyri) or Egyptian (as in most of the Tebtunis corpus)or on the level of his education (as in the Christian era documents, which are mostlylegal texts).

SyntaxSome uses of the participle are reduced: Thus, the predicative participle (i.e., in thefunction of a verbal complement) is radically restricted in the NT, confined almost en-tirely to Luke and Paul (BDF §414). Of the circumstantial meanings, some are retained(temporal, causal, concessive) and some are on their way to disappear (conditional,final), and the same is valid for the papyrological data as well (Mayser 1926:348–352, BDF §411; Jannaris 1897:506). However, other uses are still quite strong, ifnot increased- extensive participle usage is a characteristic feature of the Koine (cf.Horrocks 1997:46; Mayser 1934:62). Most of the conjunctions accompanying partici-ples disappear or are retained only when the participle is used absolutely (BDF §425,Mayser 1934:64, 74).

An important syntactic innovation is the increase of unclassical “absolute” par-ticipial constructions,9 in two different structures: use of genitive absolute participlesalthough the participial subject is co-referent with a term in the clause (5a and b)and “hanging” nominative, a participle whose subject is not co-referent with anyterm in (5c):

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.6 (375-430)

Io Manolessou

(5) a. Apestale:nsend.1sg.aor.pass.

eisto

tonthe

hypounder

soiyou

nomon. . .nome. . .

emu:I-gen

aite:samenu:having.petitioned.gen.sg.masc.act‘I was sent to your district, having asked for it myself.’

(P.Giss.11.4 (118 AD))b. Me:

negekhontoshaving.gen.sg.masc.act

autu:he.gen.sg

apodu:nai,to-give back,

ekeleusenordered

autonhim.acc.sg

hothe

kyriosmaster

autu:.his

‘He being unable to give it back, his master ordered him. . . ’(Ev.Matt.18.25)

c. Ekballu:sakicking.out.nom.sg.fem.act

hemasus

anekho:re:samen.left.1pl

‘After she kicked us out, we left.’ (UPZ 18.17 (163 BC))

This “breach” of the classical norm is not a Hellenistic evolution, as it already existed toa certain degree in AG – Spieker (1885) and Schwyzer (1942) provide several examples.The innovation lies in the heightened frequency of the phenomenon. An examinationof the 4 Gospels of the NT, for example, shows that the norm is to use the absoluteconstruction whenever the participle is not subject-oriented, and to employ the con-joined participle when it refers to the main clause subject (in which case it appearsin the nominative) or to an infinitival clause subject (in which case it appears in theaccusative). In the same vein, Whaley (1990), examining the choice of the absolutevs. the conjoined construction in the NT, establishes that absolute participles occureven when their subject is a constituent of the matrix clause when (a) the participialsubject is co-referent with a non-primary term, such as an indirect object, a preposi-tional complement or noun raised out of a participial or subordinate clause or (b) theparticiple belongs to an unaccusative or unergative verb.

. Stage 3 – Late post-classical / early medieval (4th–6th c.)

MorphologyThe first concrete signs of inflectional erosion are neuter nom./acc. singular forms end-ing in [-onta] instead of [-on], appearing ca. the 4th c. (Kapsomenakis 1938:40), (6).

(6) a. Zoðion. . .animal.acc.sg.neut. . . .

katexontaholding.acc.sg.masc.act

lampaða.torch

‘An animal holding a torch.’ (PGM.II.36.179, 4th c. AD)b. To

thepraγmathing.acc.sg.neut

tothe

ðiaby

EvðemonosEudaimon

lekθenta.said.acc.sg.masc.pass

‘The thing that was said by Eudaimon.’ (POxy.1348, late 3rd c. AD)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.7 (430-484)

From participles to gerunds

It is unclear whether this ending is an extension of the neuter plural nom./accusativeor of the masculine singular accusative, as both end in [-onta]. The second alterna-tive is much likelier, both because the masculine is more frequent in speech than theneuter, and also because of a possible analogy with the 2nd declension (o-stem) passiveparticiples:10 in the 2nd declension, the masculine singular acc. ending is identical tothe neuter singular nom. and acc. (being in all cases [-menon]), so this formal identitybetween masculine and neuter might have been carried over to the 3rd declension aswell. In texts, active participles with the new ending frequently occur side by side withmedio-passive ones, (7):

(7) a. Cektimepossess.1sg.perf

ktimapossession.acc.sg.neut

miteneither

fθiromenondecaying.acc.sg.neut.pass

miteneither

liγonta.ending.acc.sg.masc.act

‘I possess a possession which neither decays nor ends.’(Acta Thomae 136.15)

b. Lutronbath.acc.sg.neut

mineg

ypoceomenonburning.under.acc.sg.neut.pass

alla. . .but

parexonta.offering.masc.sg.acc.act‘A bath not heated underneath, but offering. . . ’ (Malalas 178.65)

In early Medieval Greek (MedG) texts, such neuter forms occur occasionally.11 Thereare no quantitative studies on the extent of the phenomenon, and indeed it is almostimpossible for them to exist or to form a solid basis for conclusions, due to the tex-tual tradition of these linguistic monuments: the evidence for spoken language for theperiod between the 6th and the 12th c. is very meager, and in most cases preserved inmanuscript copies several centuries posterior to the date of composition. The differentmanuscripts preserving a text of the period may present several variant readings in thepassages in question, some maintaining the “classical” form and others showing theinnovative one.

To give some examples: the text of the critical edition of the Life of St. John theAlmsgiver, 6th c. (Gelzer 1893) prints 6 cases of the neuter participle with the new-onta ending (cf. the editor’s Grammatisches Verzeichnis, entry Participia), and thereare alternative readings in -onta in 3 more cases, to be spotted only by checking theapparatus (at 50.6, 87.22 and 97.15). However, the manuscript tradition (the 6 mss.,ABCDEF, used in the edition) is unanimous in none of these eight cases: three appearonly in A, two only in C, one only in E, one in ACEF and one in ABCE. It is thusimpossible to guess which and how many of those stood in the original text, and whichare readings introduced by a later copyist. On the other hand, the text of Malalas,a main source for the low-register language of the period, is preserved in only onemanuscript, of the 12th c., and thus the lack of corroborating manuscript evidencemakes it another kind of insecure textual witness.

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.8 (484-569)

Io Manolessou

Table 1.

Text Century Attributive Complement Adverbial

Malalas 6th 15 2 4Leontios of Neapolis 6th 4 0 2Chronicon Paschale 5th 3 0 0Vita Epiphanii 6th 3 0 0Apocalypses Apocryphae 2nd–6th 5 1 0Funerary inscriptions 5th–7th formulaic – –Digenis E 12th 0 2 5Chronicle of Morea (6000vv.) 14th 0 9 45War of Troy (4000vv.) 14th 0 2 17Velthandros 14th 0 3 7Livistros V 14th–15th 0 0 2Machairas (40pp) 15th 2 0 49

Nevertheless, considering that the new neuter -onta ending appears in almost allthe near-vernacular texts we possess from the period, even if not in unanimous textualtradition, and even if less frequently than the classical ending, it should be consideredas established in the spoken language by this time. The inscriptional evidence from thesame period (cf. Section 2.4 below) corroborates this assumption.

A further development in the active participle is the obsolescence of the Perfectform (in -o:s, -yia, -os). It occurs very rarely in early MedG texts, often conjoined withAorist forms (e.g. elθo:n. . . ce eorako:s Mal.221.62, pyisas ce. . . katesxiko:s Mal.372.15),showing that the feeling for a special meaning of the Perfect had been lost. This se-mantic development in the Perfect (cf. Hatzidakis 1892:204–205; Wolf 1911:65–66,and esp. Moser 1988 for details), which led to the loss of monolectic Perfect formsand the evolution of periphrastic ones, left also the Passive Perfect Participle withoutparadigm support. Gradually, one of its main characteristics, initial reduplication, waslost, and this marked a step away from verbal properties.

SyntaxThe new neuter form is still an agreeing participle, employed mostly with attributivemeaning. This can be gauged from the Table 1 which lists the usage of -onta/-ontasforms in earlier vs. later MedG texts. All [-onta] forms in earlier texts are neuter nom.or acc. singular, while those in the later texts are of any gender/number.

“Attributive usage” includes cases where the participle is used as:

– an attributive modifier, equivalent to a relative clause, (8):

(8) a. Etiçisefortify.1sg.aor

tothe

ðoras,Doras.acc.sg.neut,

xorionvillage

onta.being.acc.sg.masc.act‘He fortified Doras, which is a village. . . .’ (Mal.326.54)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.9 (569-637)

From participles to gerunds

b. Tothe

paraksenonbeautiful

lutronbath.acc.sg.neut.

tuof the

xrisokastrou/golden-castle/

tothe

jemontafilled.acc.sg.masc.act

tasthe

iðonas.pleasures

‘The beautiful bath of the Golden Castle / filled with every kind of plea-sure.’ (Kallimachos 1720)

– a substantivised adjective, (9):

(9) Meligoing.to.3sg

tothe.acc.sg.neut

poteonce

apoθanontadead.acc.sg.masc.act

ceand

anastanta. . .having.risen.acc.sg.masc.act. . .

apelefsesθe.leave.inf

‘That which has died and risen again is going to leave.’ (Vit.Epiph.89A)

– a predicative modifier (i.e. a small clause), (10):

(10) Peðariuchild.gen.sg.neut

teleftisantos,having died,

zontaliving.acc.sg.masc.act

apeðocegive.3sg.aor

tito the

mitri.mother

‘A little child having died, he gave it back to its mother alive.’ (Chron.Pasch.181)

“Complement” includes cases where the participle is the complement of a verb, (11):

(11) a. θeoruntonseeing.pl.gen

totheθirionbeast.neut.sg.acc

ekfevγonta.escaping.masc.sg.acc.pres.act

‘Seeing the beast escape.’ (Romanus Melodus 72.κδ.2)b. Fenome

appear.1sg.prespipraskontaselling.acc.sg.masc.act

tonthe

emonmy

ambelona.vineyard

‘I declare that I am selling my vineyard.’ (Guillou, Messina 5, 1135 AD)

“Adverbial usage” includes cases where the participle is used as an adverbial, expressingmanner, cause, concession, etc., (12):

(12) a. ðeçetegreet.1sg.pres

aftonhim

jyneonwoman.nom.sg.neut

prospiptontafalling.down.acc.sg.masc.act

ceand

leγonta.saying.acc.sg.masc.act

‘A woman greets him by falling on her knees and saying.’ (Leontios 64.1)b. Kleonta

crying.acc.sg.masc.actceand

oðiromenoswailing.nom.sg.masc.pass

citelie.3sg.pres

isat

tothe

klinarin.bed

‘He lies on the bed, crying and wailing.’ (Digenis E 393)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.10 (637-708)

Io Manolessou

The old forms of the participle (masculine, feminine, other cases of the neuter), per-fective and imperfective stem, are still in full use and extremely frequent.

In early MedG the unclassical usage of absolute participles observed in the previ-ous period continues and even increases (cf. Jannaris 1897:500; Weierholt 1963:70–75). At the same time, a more clear-cut indication of the breakdown of agreementbetween the matrix clause and the participial clause appears: the participle often seemsto agree with the element immediately adjacent to it instead of with its subject (cf. alsoWolf 1912:27–28), (13).

(13) a. Emineremained

tothe

jenoskin.nom.sg.neut

tuof

PerseosPerseus.gen.sg

vasilevontos [for vasilevon].ruling.gen.sg.neut.act‘The kin of Perseus remained ruling (in power).’ (Mal.28.24)

b. Apelθontahaving-left.acc.sg.masc.act

ceand

tothe

riγontishivering.dat.sg.masc.act

synantisanti [for synantisanta].met.dat.sg.masc.act‘When he left and he met the shivering one.’ (Leontios 48.8)

c. Erosobe.healthy.2sg.imp.

myme.dat,

cyrielord

mumy

pater,father,

eftyxuntibeing.happy.dat.sg.masc.act

my [for eftyxon].me.dat

‘Be healthy, my lord father, being happy for my sake.’ (Rev.Eg.1919.201)

Another potential symptom of a purely “verbal” re-interpretation of the participle isthe tendency to equate it with a finite verb, able to be coordinated with it (cf. Jannaris1897:§2168b; Wolf 1911:56; Frisk 1928; Schwyzer 1950:407; Mandilaras 1973:372;Kavcic 2001, and esp. Cheila-Markopoulou 2003), (14).

(14) γrapsashaving.written.nom.sg.masc.act

ðeand

othe

Zakçeos. . .Zacchaeus. . .

ceand

leγi.say.3sg.pres

‘Zacchaeus has written. . . and says.’ (Evang.Thomae B 7.1)

. Stage 4 – Middle Byzantine

MorphologyThe next step in the evolution is the spread of the [-onta] ending to masculine andfeminine forms. Early examples occur in inscriptions from Asia Minor (Klaffenbach1933). A search in inscriptional corpora12 shows that early Christian funerary inscrip-tions standardly contain the formula mnimion/mnimorion/cymitirion ðiaferonta tu X(‘grave.neut belonging to X’, cf. Bees 1910). There are abundant attestations fromCorinth, Thessaly, Macedonia, Attica etc., evidence of the spread of the new neuterending. In the inscriptions from Korykos (5th and 6th c., Keil & Wilhelm 1931), the fu-

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.11 (708-775)

From participles to gerunds

nerary formula is feminine: θici/somatoθici ðiaferusa tu X (‘coffin.fem belonging.femto X’). In many cases, it has changed to θici ðiaferonta. These are the earliest consis-tent13 attestations of the spread of [-onta] to the feminine. The earliest securely dated(9th c.) occurrence of the [-onta] suffix in an adverbial function with a masculinenoun occurs in the Proto-Bulgarian inscriptions (Beshevliev 1963), (15):

(15) Isat

tisthe

PlskasPlska.gen

tonthe

kamponplain

menontaremaining.acc.sg.masc.act,

epyisenmake.3sg.aor

avlin.court

‘Remaining in the plain of Plska, he built a court.’ (56.5–7, 822 AD)

SyntaxUnfortunately, texts close to spoken language are insufficient in this period, and thusdo not allow reliable conclusions. The -onta form seems to be still mainly attribu-tive; however, the adverbial usage of the gerund form has already appeared. The AGparticiple form is still extensively used, mainly in temporal and causal function.

The passive participle is used mainly attributively, and often as a verbal comple-ment, being very frequent in perfect periphrases with the verbs “to be” and “to have”(cf. Browning 1983:32–34; Aerts 1965; Moser 1988 for an overview).

. Stage 5 – Later Byzantine (12th–15th c.)

MorphologyThe [-onta] gerund becomes established for all genders and cases. From the 14th c.onwards, a final -s is added to the ending, giving it the standard MG form [-ontas].14

This is in all likelihood an adverbial suffix, appearing in other adverbs as well, e.g.totes ‘then’, potes ‘never’, tipotas ‘nothing’ (Hatzidakis 1934; Horrocks 1997:229), andnot the [-s] suffix of the nominative (as in Schwyzer 1950:410). The forms with andwithout [-s] coexist in texts of the period, but distributional data are lacking.

This period sees an important evolution in the passive participle, the extension ofpassive perfect forms to active morphology verbs with stative, inchoative, unaccusativeor unergative meaning, something that is maintained in MG (Tzartzanos 1989:330–331; Moser 1988:145–152; Alexiadou & Anagnostopoulou 1999:25), (16):

(16) pinao → pinazmenos I am hungrytroo → faγomenos I eatnistazo → nistaγmenos I am sleepyγonatizo → γonatizmenos I kneelkitrinizo → kitrinizmenos I grow yellow

This was not the case in AG, except for a couple of isolated instances; it is a Medievalevolution (details in Hatzidakis 1924, 1927) but there is no information on when these

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.12 (775-850)

Io Manolessou

participles first appeared. Examples do occur in the first vernacular medieval texts(12th–13th c.), (17).

(17) Ipate,go.2sg.imp

kinijisetehunt.2sg.imp

opuwhere

isteare.2pl

maθimeni.learned.nom.pl.masc.pass

‘Go hunt where you used to.’ (Digenis E 1303)

It also seems that passive participles with active meanings are a Balkan Sprachbundphenomenon, appearing in some Balkan languages as well (cf. Lindstedt 2002); thiswould point to a medieval datation of this evolution as well.15

SyntaxThe main function of the active participle is adverbial – complement usage is rare, andattributive almost non-existent. The active form can now be properly called a gerund,as it is not an acceptable nominal modifier any more, (18):

(18) a. Taftathat

iponsaying.nom.sg.masc.act

estraficeturned.3sg

jelontalaughing.acc.sg.masc.act

prostowards

ecinin.her

‘Having said that, he turned to her laughing.’ (Velthandros 861)b. Utos

heexontahaving.acc.sg.masc.act

jinekan,wife,

tothe

ðiceonlaw

orizi.dictate.3sg

‘If he has a wife, the law dictates. . . ’ (Assizai.146.15–6)

However, the complement usage is not yet extinct, (19):

(19) a. Totethen

nasub

iðessee.2sg.aor

arxondises. . .noblewomen

kratuntaholding.acc.sg.masc.act

tathe

peðia tus.children-their‘Then you could have seen. . . noblewomen holding their children.’

(War of Troy 1101)b. Fenome

appear.1sg.prespipraskontaselling.acc.sg.masc.act

tonthe

emonmy

ambelona.vineyard

‘I declare that I am selling my vineyard.’ (Guillou, Messina 5, 1135 AD)

The only attributive usages appear with the neuter (cf. the formula xorion to onta ceðiacimenon ‘the village being and located’ in S. Italian documents.16

The passive participle is mainly used adjectivally (details in Moser 1988:229–235).The AG forms are still used side by side with the gerundival ones, their frequencydepending on the register of the text.

With the loss of case from the gerund, the ancient type of “absolute” participles(in the genitive or hanging nominative) disappear. However, vestiges of absolute par-ticiples in the genitive survive in conservative MG dialects, such as Cypriot and Cretan,

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.13 (850-900)

From participles to gerunds

in the form of gerunds having genitive subjects (Menardos 1925b:64; Giakoumaki1993) (20):

(20) a. Poθanontadying.acc.sg.masc.act

tuthe

pappugrandfather.gen.sg.

mu,my,

epiramenget.1pl.aor

tothe

spitin.house‘Upon my grandfather’s dying, we got the house.’

b. Kateontasknowing

muI.gen.sg.

indawhat

muflusisbankrupt

ine,is,

ðenot

duhe.gen.sg

ðuðogive.1sg.pres

ðanika.loan

‘Knowing what kind of a loser he is, I’m not giving him a loan.’

Alternatively, these examples of deviant dialectal syntax, unacceptable in standard MG,could be viewed not as archaic survivals but as new independent evolutions; in thisconnection, the parallel with the structures evolved in languages such as English orHebrew, where genitive subjects for indeclinable gerunds are the norm is quite striking.However, it has to be noted that these constructions date at least to late MedG, as theycan be found in works of the period, (21):

(21) a. Ithe

rijenaqueen.nom.sg.fem

ithe

Alis. . .Alice

pijenontagoing.acc.sg.masc.act

tisshe.gen.sg

isto

tonthe

Maçeran. . .Machairas

eθelisewant.3sg.aor

nasub

bi.enter.3sg.aor

‘Queen Alice, upon her going to Machairas. . . wanted to enter.’(Machairas 54.18)

b. Strefontaturning.acc.sg.masc.act

tusthey.gen.sg

ithe

mandatofori. . .envoys . . .

eðokangive.3pl.aor

tastheγrafas.letters

‘Upon their returning, the envoys gave the letters.’ (Machairas 94.36)

Apart from these dialectal constructions with the genitive, the gerund does have “ab-solute” uses, in that its subject is not co-referential with that of the main clause, (22):

(22) a. ðiavonta γarhaving.passed.acc.sg.masc.act

enasa

ceros,time.nom.sg.masc

ejirisenreturn.3sg.aor

ecinos.that.nom.sg

‘Some time having passed, he returned.’ (Chr.M.1048)b. Ce

andlalontaspeaking.acc.sg.masc.act

tonthe

loγon,word,

ekaθarisenclear.3sg.aor

ithe

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.14 (900-965)

Io Manolessou

γlosatongue.nom.sg

tis.hers

‘And as she spoke the word, her tongue was freed.’ (Machairas 68.21)

This continues into the next period as well, and is maintained up to MG (details of thisusage in MG literature in Nakas 1985), cf. two examples from the 17th c., (23):

(23) a. Ontasbeing.acc.sg.masc.act

aftoshe.nom.sg

peðionchild

akomi,still,

tonhe.acc.sg

estilensend.3sg.aor

othe

paterasfather

tu.he.gen.sg

‘When he was still a child, his father sent him. . . ’ (BGV III, 362.21)b. Angaliazontas

embracing.acc.sg.masc.actenaa

ðendro. . .tree. . .

meI.acc.sg

ektipusanhit.3pl.imperf

ethe

petre.rocks.nom.pl

‘As I was holding on to a tree. . . the rocks were hitting me.’ (BGV I, 331)

. Stage 6 – Post-Byzantine Greek

MorphologyThe next stage in the evolution of the gerund is the loss of tense. In the previous periodactive participles could be formed both from aorist and present stems, (24):17

(24) a. Staθontahaving.stood

katatowards

anatolaseast

anaγnoseread.2sg.imp

ceand

ipetell.2sg.imp

ton.he.acc.sg‘First stand facing east, and then read and tell him.’ (War of Troy 561)

b. Iðontashaving.seen

tutothat

othe

ajios.holy

‘The holy father, having seen that. . . ’ (Chr.M.18)

After the end of the MedG period, gerunds can only be formed from present stems,except for the Greek dialects of S. Italy. In some of these dialects, aorist gerunds areused only with the verb “to be” in perfect periphrases and the present stem is employedin all other functions (Katsoyannou 1995); however, in others the Aorist gerund is stilla living category (Karanastasis (1997:144), (25).

(25) Vletsontahaving.seen

othe

cero,weather,

ennot

ixahave.1sg

pantagone

Luppiu.Lecce

‘If I had seen the weather, I wouldn’t have gone to Lecce.’

As far as the passive participle is concerned, the Present form of the participle(-omenos) becomes gradually reduced in use, and in fact ceases to be an integrated

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.15 (965-1030)

From participles to gerunds

part of the participial system. Apart from a few analogically created popular formsin -amenos and -umenos, (e.g. trexamenos ‘running’, petumenos ‘flying’), which havealmost exclusively attributive function,18 the present passive participle in MG is aformation re-introduced in the language via the kathareuousa (see below 2.7).

So the system of the participle, as presented in the first Grammar of MG, NikolaosSofianos (ca.1544), is as follows (Papadopoulos 1977:76):

all the participles of the old Greeks are analysed with the finite verb of the tensewhich the participle would be in, plus [the relative complementiser] opu. . . In allactive tenses. . . there is only one non-finite participle, γrafontas, kratontas. . . Asfor the passive verbs, the perfect participle has been maintained up to our time,and it is inflected in the three genders, o γramenos, i γrameni, to γrameno. . .

Around the 16th c., therefore, the active voice possessed only the active gerund in[-ontas], while in the passive voice only the perfect participle survived. The situationdescribed by Sofianos is easily exemplified by a recent study on the transposition of AGparticiples in 17th c. vernacular translations of the lives of Aesop (Karla 2002). In thiscase, the large majority of participles of the original, post-classical, text have been re-placed by finite clauses or adjectives, and only 11% of them have been retained (eitheras archaic declinable participles or as gerunds).

SyntaxThe MG situation, with the active gerund having predominantly adverbial usage andthe passive participle predominantly adjectival, has been reached.

. Stage 7 – Modern Greek

MorphologyStandard MG sees a new regularisation/filling out of the participial and gerundivalparadigm. Side-by-side with the “present” gerund, a periphrastic perfect form is cre-ated, using the gerund of the auxiliary verb “to have” along with a perfective infinitiveform (e.g. exontas γrapsi). There are no data concerning the date of appearance andthe spread of this new formation (Nakas 1991:178), but older Grammars (Triantafyl-lidis 1941:373; Tzartzanos 1989:339) recognise its innovative, “artificial”, status, andstatistical analyses of participial usage in MG (Iordanidou 1985; Rydå 1988) show thatit is very rare; some Grammars (including school grammars) do not mention it at all.

In the passive domain, the present participle is re-introduced. This is generally ac-cepted to be a feature of kathareuousa, and not a direct inheritance from AG (Nakas1991:182–187). Earlier Grammars explicitly state that it is an element foreign to “de-motic”, and statistical investigations also show that its use is limited. Furthermore, it isfar from productive; thus, verbs of modern/demotic origin rarely if ever have presentparticiples (e.g. *lavonomenos, *viðonomenos, *leronomenos, *spazomenos) and verbswhich have both a kathareuousa and a demotic variant possess a present participleonly for the first (liomenos vs. *linomenos, enðiomenos vs. *dinomenos, feromenos vs.

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.16 (1030-1095)

Io Manolessou

*fernomenos etc.). The passive present participle cannot therefore be considered as fullyintegrated into the verbal paradigm, on a par with any other verbal form.

Another evolution belonging to the MG period is the appearance of a periphrasticpassive gerund, formed by the gerund of the verb to have and a perfective passive in-finitive (e.g. exontas γrafθi). This is yet another new and not extensively used form,frequently absent from Grammars of MG because of its rarity. The evolution of thisform is one more indication of the non-verbal character of the monolectic passive par-ticiple: it is this new periphrastic formation, and not the inherited “perfect participle”,that unambiguously expresses the categories of “perfect tense” and/or “perfect aspect”,as well as of “passive voice”. But it is a gerundival, and not a participial form, showingonce more that verbal and nominal features are incompatible in MG participles.

SyntaxThis topic is extensively treated in Tsoulas (1996), Tsimpli (2000), Sitaridou andHaidou (2002), Moser (2002) and Tsokoglou and Kleidi (2002) and will therefore notbe developed in any detail here.

The MG gerund has only adverbial meaning and cannot appear in argument po-sitions.19 Its temporal interpretation is dependent on the meaning of the verb and thegeneral context (cf. Tsimpli 2000; Moser 2002 for details). Contrast (26a) with (26b):

(26) a. Efijeleave.3sg.aor

klinontasshutting

ðinataloudly

tinthe

porta.door

‘He left, banging the door loudly.’ (anteriority)b. Klinontas

shuttingtinthe

porta,door,

iðesaw

tinthe

efimeriðanewspaper

stoat

katofli (simultaneity)the threshold

“As he was shutting the door, he saw the newspaper on the threshold.”

Furthermore, the gerund is often considered exclusively subject oriented, althoughit is possible to find gerund subject which are: (a) null and non-co-referential withthe main clause subject in the case of impersonal or arbitrary/generic reference (27a)(b) co-referential with another term in the clause (27b and c) “nominative abso-lute” subjects different to that of the main clause, which must always appear after thegerund (27c):

(27) a. Troγontaseating

erçetecome.3sg.pres

ithe

oreksi.appetite.nom.sg

‘The appetite comes with eating.’b. Telionontas

finishingtothe

Panepistimio,University,

tonhe.acc.sg

piranetake.3pl.aor

stoto

strato.the army

‘When he finished the University, he was drafted in the Army.’c. Fevγontas

leavingithe

ðaskala,teacher.nom.sg,

jelasanlaugh.3pl.aor

tathe

peðjia.children

‘As the teacher left, the children laughed.’

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.17 (1095-1174)

From participles to gerunds

As for the passive participle, there is a relative consensus that it has a number ofnominal properties which make its distinction from a simple adjective difficult. Theseinclude (Moser 1988:167–168; Anagnostopoulou (2001:2–4):

a. it can occur in pre-nominal position as noun modifiersb. it can have comparative and superlativec. it can be conjoined (with ce (‘and’)) with true adjectivesd. it can occur as predicate with verbs like fenome (‘look’), mnjiazo (look like’) etc.e. the agent can be incorporated, e.g. iliomavrismenos (with suntan)f. it can be intensified with para-(‘too’) , e.g. paramavrismenos (with too much

suntan)g. it can form adverbials with -a, e.g. θlimenos > θlimena (‘sad’ > ’sadly’)h. its derivation is irregular, i.e. several active morphology verbs form it, and several

passive form verbs do not.

The passive participial clauses quoted in Tsimpli (2000:159) are no different fromother adjective small clauses, which attribute a “temporary” property to the modifiednoun. Thus, compare the sets of sentences in (28a, b) and (29a, b):

(28) a. Mewith

ðemenatied

tathe

çerjiahands

ðenneg

borusacan.1sg.imperf

nasub

ksisto.scratch.1sg.aor.pass‘With my hands tied, I couldn’t scratch myself.’

b. Mewith

elefθerafree

pjaat.last

tathe

çerjia,hands

boresacan.1sg.aor

nasub

ksisto.scratch.1sg.aor.pass‘With my hands free at last, I managed to scratch myself.’

(29) a. Kinijimenoshunted

//

ðjoγmenoskicked.out

othe

Jianis,John,

anangastikeforce.3sg.aor.pass

nasub

fiji.leave.3sg.aor‘John, hunted / kicked out, was forced to leave.’

b. Etimosready

jiafor

olaeverything

othe

Jianis,John,

arniθicerefuse.3sg.aor

nasub

fiji.leave.3sg.aor

‘John, ready for anything, refused to flee.’

So the syntactic roles of the passive participle are identical to those of the adjective.20

. Summary of evolution

On the basis of the above, the evolution of the Greel participial system can be sum-marised as follows:

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.18 (1174-1221)

Io Manolessou

1. The active participle already showed diminished gender agreement from AGtimes, but maintained its functionality until the first centuries AD. The first sign ofevolution is syntactic, namely the increase in absolute constructions in the Koineperiod, an indication that the agreement mechanism of the participle with the ma-trix clause is breaking down. Around the 4th c. the first morphological effects ofchange become evident, with the reduction in the inflectional system representedby the innovative neuter ending -onta (arising probably from collocations withthe accusative of the passive participle). This spreads to masculine and femininenouns during the 6th–8th c., as testified by inscriptional evidence. The next stepin the evolution, after the loss of agreement, is the loss of tense (in reality of theimperfective/perfective distinction), occurring around the 14th c. The addition ofthe adverbial -s suffix marks the final and definitive reanalysis of the gerund as anadverb. The MG gerund has neither Agreement, nor Tense – however, it is in theprocess of acquiring a new aspectual distinction.

2. The passive participle maintained its full nominal agreement system throughoutthe history of Greek. The development went rather in the way of loss of ver-bal characteristics. Thus, Koine times see a reduction in the types of participleavailable (loss of final, concessive, causal etc. participles), as well as of the subordi-nating conjunctions/complementisers introducing them. Also, the Tenses becomereduced, with the loss first of the Future and the Aorist, and later of the Present. Inlater stages, the uses of the participle become further reduced, until it is reservedonly for attributive functions. At some point in the Medieval Period, the categoryof Voice is lost as well, since Passive participles begin to be formed also from activemorphology verbs with unaccusative or unergative meaning.

Thus it is crucial misconception that “the active participle changed and disappeared”,while “the passive participle did not change and was maintained”. In fact, the passiveparticiple has changed; an indication of this are the numerous studies examining thesimilarities and differences between “passive participles” and adjectives, and propos-ing criteria of differentiation, e.g. Laskaratou and Philippaki (1984), Setatos (1985),Sklavounou (2000), Anagnostopoulou (2001). The evolution examined here is not achange affecting one part of the participle system while leaving the other intact, but arestructuring of the whole system, affecting both parts in different ways.

. Parallel evolution in other languages

The change from participle to gerund is a phenomenon not unique to Greek, but cross-linguistically well attested. In the words of Haspelmath (1995:17):

Converbs [=nonfinite verb forms functioning as adverbial modifiers] seem toarise from two main types of sources: (a) . . . verbal nouns which have becomeindependent from their original paradigm; and (b) . . . participles which lost theircapability for agreement.

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.19 (1221-1283)

From participles to gerunds

As will be shown below, process (b) appears in Slavic, Baltic and Romance, where,independently, the active present participle has become a gerund, as in Greek.

. Romance

The historical syntax of the Romance languages displays a pattern very similar toGreek: the indeclinable gerund acquires all the verbal functions of the active participle,and the latter becomes a pure adjective, outside the verbal system (Harris 1978:199–203). More specifically: Classical Latin possessed a triple opposition between (a) anagreeing passive gerundive, (b) a non-agreeing active gerund, similar to a verbal nounand (c) an agreeing, active present participle. The gerundive disappeared completely,and so did three out of the four cases of the noun-like gerund (genitive, dative andaccusative). The ablative case of the gerund, however, originally denoting only in-strumental notions such as manner, accompaniment etc., gained ground widely, andrivalled the present participle as an adverbial modifier to the main verb. Already inClassical Latin it was possible to find present participles co-coordinated with ablativegerunds (Kühner-Stegman 1966:753), (30).

(30) incendium. . .fire. . .

inin

editahigh

assurgensclimbing.neut.nom.sg.pres.act

etand

rursusthen

inferioralower

populandodevastating.ger.abl

‘The fire. . . climbing first to the high places and then devastating the lowerones.’ (Tacitus 15.38)

Later Latin sees: (a) the reduction of the active present participle to adjectival uses (b)the extension of absolute constructions, even when the subject is a term of the clause(c) the use of the participle as a finite verb (three developments identical to Greek)and (d) the passing over of the adverbial uses of the participle to the ablative of thegerund.21 For example, in Medieval Spanish translations of Latin texts, the participle,especially in absolute usages, is often glossed by the gerund (Muñío Valverde 1995:12).

ignorans: glosed as non sapiendoignoring-masc.sg.nom.pres.act: glossed as not knowing-gerund.abl

In French, the gerund and the participle coalesced morphologically, to give one form,ending in -ant, which is used either indeclinably as a gerund or declinably as anadjectival participle, (31):

(31) Je viens en chantant (‘I come singing)’La femme chantante vient (‘The singing woman comes’)

In the other Western Romance languages, Spanish and Portuguese, the two forms arestill morphologically separate, but (a) the gerund (-ndo) has both retained its originalgerundival functions (as a manner adverbial) and taken over all the verbal functionsof the present participle as well, including all occurrences with periphrastic verbal

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.20 (1283-1340)

Io Manolessou

paradigms; and (b) the still agreeing present participle (-nte) is wholly adjectival, lyingoutside the verbal system proper and unable to express any circumstantial notion.

. Slavic and Baltic

The Russian gerund (deeprichastiye) evolved out of the active present participle, andis, in the modern language a tenseless and nonfinite form (Babby & Franks 1998). Firsttraces of this development appear already in Old Church Slavonic translations of theGospels, and become more frequent in later texts (Vaillant 1964:252–253).

Examining the Bulgarian participle, Hult (1991:100) offers an overview of the par-ticiple evolution in the Slavic languages. According to him, the gerund of Russian,Czech and Slovenian goes back to the Old Church Slavonic masculine/neuter nomina-tive form of the present active participle, while the gerund of Ukrainian, Byelorus-sian, Polish, Slovak, Serbo-Croatian and Bulgarian to the oblique case stem of thesame form.

Taube (1981:128–129) describes the environments where the breach of agreementbetween subject and participle, is most frequent in Old Russian texts (chronicles ofthe 15th c. AD. According to him, it is exceptional when the participle has adjectival(attributive) function, or is used as a predicate with a copula or an auxiliary verb; it isoccasional when the participle is absolute and it is regular when the participle has anadverbial function.

Although the Lithuanian participial system is more complex than that of other ex-amined languages, the general evolution is similar: a language which did not originallypossess gerund forms develops them out of active participles with adverbial mean-ing.22 As in Greek, the change starts from active neuter forms in the accusative, laterspreading to masculine and feminine nouns and pronouns (Ambrazas 1990:253).

So the developments in the participle of other languages bear a hitherto unnoticed,but striking similarity to Greek: in the environments where the participle has a morestrongly “verbal” meaning (i.e. imparts a temporal, causal etc. sense) it tends to loseits nominal characteristics and become a pure indeclinable adverbial, whereas in caseswhere its attributive function is strong it verges towards total loss of verbal features.23

. The evolution from participle to gerund

. Introduction

The evolution described in Sections 2 and 3 constitutes a potentially fruitful testingground for theories of syntactic change. It involves a radical change in a specific syn-tactic category – a change which takes place over a long period of time, appears inseveral languages, has not up to now been sufficiently investigated, and does not fallunder the heading of grammaticalisation, the kind of change most commonly exam-

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.21 (1340-1401)

From participles to gerunds

ined in diachronic syntax. However, the restricted amount of interest it has generatedis, to a certain extent, a limiting factor for its in-depth investigation.

More specifically, as discussed in 2.1, there are no studies offering syntactic ac-counts of the complex AG participial system or the quantitative data necessary forthem, and even the comparatively simpler MG gerund is an object of controversy(see Section 5); thus, neither the beginning nor the end of the process are at all se-curely established. Furthermore, none of the well-studied modern languages possessesa participial system similar to the AG one, and so the analyses covering the partici-ples of other languages cannot apply to AG without considerable further elaboration.Moreover, current analyses of participles tend to focus on the question either of in-ternal participial structure or of participles in auxiliary verb structures; thus they havevery little to say on topics that are crucial for the evolution under investigation, whichinvolves mainly participles in adverbial function.

. Previous accounts

The standard interpretation of the evolution of the Greek active participle is based onmorphological considerations. According to this view (cf. Jannaris 1897:206; Dieterich1898:206; Horrocks 1997:122–124), the active participle, which belongs to the com-plex AG 3rd (consonant-stem) declension and shows widely differing endings accord-ing to person and tense, has limited learnability, in contrast to the passive participle,which belongs the much simpler 2nd declension (o-stem). The “unwieldy” activeform, after going through a period of instability, as attested by numerous errors ofagreement in papyri, ends up in total indeclinability, whereas the passive form ismaintained throughout the history of Greek.

There are a number of problems with this account. First, as shown in 2.2, thepapyrological data are not conclusive: errors of agreement occur also with 2nd de-clension forms, and are much more common when the writer is not a native speakerof Greek – so the picture of declensional instability presented in Grammars of papyricannot be relied upon without systematic textual investigations. However, the maindifficulty with this account is that “indeclinability” is not an option for Greek, whoseoverall system depends on overt case differentiation; in cases of “difficult” declensionpatterns, the evolution is metaplasm, i.e. analogical re-formation according to a sim-pler inflectional pattern. Thus, as Hatzidakis (1928:635) notes, the corresponding 3rddeclension nt-stem nouns such as drako:n, gero:n, Kharo:n, have had a totally differentevolution from the participle: they have not lost inflection, but have been reformed to1st or 2nd declension ones (ðrakos, γeros/γerontas, Xaros), and the same goes for sub-stantivised participles as well (arkho:n, patho:n > arxontas, paθos). And generally, thewhole of the AG 3rd, consonant-stem, noun declension, has changed over to a simplervowel-stem paradigm in MG, apart from certain subclasses (cf. Seiler 1958).

Similarly, 3rd declension adjectives with comparable inflection patterns (e.g. s- orr-stems) also show break-down of agreement (cf. Gignac 1981:138–141) in the papyri,without ever ending up in indeclinability. These too are re-formed analogically, fol-

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.22 (1401-1466)

Io Manolessou

lowing the vowel stem declensions (Browning 1983:78), e.g. melas > melanos, ale:the:s> aliθinos etc. In other words, the process of indeclinability affects only participles, andnot nouns and adjectives of similar inflectional patterns.

The morphology-based interpretation of the participle > gerund evolution hasthe added disadvantage that it cannot account for two main claims made in this pa-per, namely that: (i) this evolution is not an exclusively Greek phenomenon, but, asdemonstrated in Section 2, is to be found in several languages, thus precluding aGreek-specific causation and (ii) the parallel developments in the domain of the pas-sive participle, i.e. the evolution participle > adjective (crucially, also not an exclusivelyGreek phenomenon) show that we are dealing with a larger change, which affects thewhole participial and agreement system.

. Origins of the change

If one rejects the standard view of gerund evolution, an alternative interpretation,not involving a direct morphological trigger and taking into consideration the cross-linguistic extent of the phenomenon is desirable. In this section, we will pursue apotential alternative interpretation, based on the syntactic mechanism of control inparticipial subjects.

Some initial assumptions on the analysis of participles must be made:

– All participles must have a subject of their own, due to theta-role considerations.– This subject may be a full lexical noun phrase (in the case, e.g., of absolute partici-

ples) but is usually a null phrase (in the case of conjoined adverbial participles).When the subject of the participle is null, it is standardly assumed to belong to thecategory PRO (cf. Kester 1994; Alexandrova 1995), i.e. it is a null pronoun appear-ing as the subject of non-finite forms, which acquires reference through a controlmechanism.

– Participles agree with their subjects. Gender and number features are transmit-ted from the subject to the participle. Case, however, depends on the syntacticfunction of the participle.

On the basis of the above, the following analysis of AG participles can be attempted:Participles have three main functions, as described in 2.1:

I. Attributive modifiers, functioning as adjectives or relative clauses.II. Complements of verbs, functioning as non-finite complement clauses.III. Adverbial modifiers, functioning as clausal adjuncts.

In case (I) participial syntax is relatively simple, as participles appear in the same syn-tactic positions as adjectives. Presumably, adjectival participles are located in somefunctional specifier within the noun phrase (DP). They therefore acquire their φ-features in the same way as adjectives do, from spec-head agreement with the headnoun. Attributive participles have a PRO subject, which is always co-indexed with thehead of the nominal projection DP where the participle occurs. So: adnominal partici-

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.23 (1466-1533)

From participles to gerunds

ples obtain number, gender and case from the head of the nominal projection withinwhich they are.

In case (II), things are straightforward again: participial complements functionlike infinitival ones, with the added proviso that they agree with their subject. Presum-ably, participles are complements of VP, and acquire case from the main verb, (32).

(32) a. De:losobvious

e:mibe.1sg

erkhomenos.coming.nom.sg.masc.pass

‘I am seen to be coming.’b. Eidon

see.1sg.aorautonhe.acc.sg

erkhomenon.coming.acc.sg.masc.pass

‘I saw him coming.’c. E:kusa

hear.1sg.aorautu:he.gen.sg

erkhomenu:.coming.gen.sg.masc.pass

‘I heard him coming.’

Gender and number on the participle do not originate from the main verb, but fromthe participial subject. Case on the participial subject can be interpreted as originatingeither from the participle, once it has acquired it from the matrix verb, or as in regularraising/ECM constructions, where the participial subject gets case from the main verbas well. So, in case II, participles acquire two f-features from their subject (gender andnumber) and one from the verbal projection of which they are complements (case). Ifthe participial subject is PRO, it can be controlled and co-indexed since it occurs in ac-commanded position.

On the other hand, construction (III), namely, participles functioning as adverbialmodifiers presents a number of difficulties. Most analyses agree that adverbial par-ticiples and gerunds are clausal adjuncts (see e.g. Kester 1994; Pires to appear). Thisfollows from their free position in the clause, but also from semantic considerations:what they modify by their adverbial meaning (cause, consequence, aim, concessionetc.) is a verbal action and not a noun. This becomes obvious in sentences containingsequences of participles, which all refer to the same subject, but which modify differentverbal actions, (33):

(33) a. Eteteleute:keidie.3sg.pluperf

pharmakonmedicine

pio:nhaving.drunk.nom.sg.masc

pyresso:n.having.fever.nom.sg.masc‘He died after having drunk a medicine, because he had a fever.’

(X.Anab.6.4.11)b. Hois

which.dat.plpa:siall.dat.pl

khro:menoiusing.nom.pl.masc

kreameats.acc.pl

epsontesroasting.nom.pl.masc

e:sthion.eat.3pl.imperf

‘Using all the said wood, roasting meat, they ate.’ (X.Anab.2.1.6)

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.24 (1533-1590)

Io Manolessou

Under this analysis, adverbial participles occupy a peripheral position within the verbalprojection of the main clause, the same as adverbs do. This would be either an externaladjunct to CP, VP or IP, or a special functional projection hosting the relevant adverbialfunction (cause, manner etc.) – cf. 4.3 below for discussion. Such a peripheral position,however, entails difficulties for the establishment of agreement and control betweenthe participle and the matrix term to which it refers.24

“Conjoined” participles have a PRO subject, co-referential with a term in the ma-trix clause, usually the subject but not always. However, relationship between PRO andthis term must work on a very loose basis: the structural position of PRO is such thatit does not allow any formal mechanism of control or licensing – as argued above, theadverbial participle will be in the specifier of projection functioning as an adverbialadjunct: it is neither within a nominal projection, nor in a complement position. Fur-thermore, since the participle displays case, gender and number features, which are infact the overt indications of its co-reference with a matrix term, one would have toassume that they have somehow been transmitted from this matrix term to the par-ticipial subject, and thence on to the participle. There is no other source for them, asadverbial adjuncts are not case-marked positions and as gender and number have to beidentical with those of the matrix term. Now, assuming that participial subject is PRO,which by definition carries null case, and invariable gender and number features (3rdsing. masc. in the case of arbitrary reference) the agreement mechanism of adverbialparticiples becomes even more complex.25

On the other hand, absolute adverbial participles do not present any problems:they obtain gender and number from their subjects, which are full lexical nounphrases. And they acquire case (genitive) by default, so their position within the ma-trix clause is immaterial. No relationship with the matrix clause is established; theabsolute participle is completely independent and its agreement mechanisms are lo-cal. From the perspective of agreement, therefore, the conjoined adverbial participleis a marked and complex construction, possessing a much simpler equivalent in theabsolute participle.

Crucially, as discussed in Sections 1 and 2, the history of both Greek and the Ro-mance languages displays a growing preference for the absolute over the conjoinedconstruction. This can be interpreted, following Roberts and Roussou (2002), as anormal result of the make-up of the human language learning device, which is con-servative and has an inherent tendency for unmarked representations (marked in thesense of less economical, requiring additional movement or realisation of features). Inthe presence of two equivalent constructions, one marked26 and one unmarked, di-achronic change will go in the direction of the unmarked option, and in the presenceof less and less evidence to the contrary, the simpler structure will be attributed to allinstantiations of the construction. In this particular case, the radical increase in ab-solute participles will in the end limit the input evidence for agreement between theparticiple and the matrix clause to such a degree that this will be in the end unlearnableto next generations of language learners.

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.25 (1590-1656)

From participles to gerunds

So, in the case of the participle > gerund evolution, language change can be seento be inherently connected with language acquisition (for this cf. Kroch 2001). Thechange will not affect passive participles in the same way, as, due to their resulta-tive meaning (Haspelmath 1994), they will much more frequently modify nouns thanverbs, and will thus occur much more rarely in adverbial function.

. From participle to gerund

In more detail, the evolution from participle to gerund can be viewed as a three-stageprocess. In the first, initial, stage, adverbial participles have an agreement requirementwith a term in the main clause, usually the subject but not necessarily so. The al-ternative of the absolute participle exists in AG, even when the participial subject isco-referential to a term in the clause; so a “more economical” alternative was alreadyin place in the language.

In step II, the agreement requirement with the matrix clause is dropped, some-thing which is mirrored in the radical increase of absolute participles. In this step, theparticipial clause is independent, and thus equivalent to an infinitival or subordinateclause. In this connection, one should mention the view of Mandilaras (1973:352–373), according to which the indeclinability of the active participle is caused by itsconfusion with the infinitive. He provides a considerable amount of evidence for aninterchange of functions between infinitive and participle in the non-literary papyri.Examples include prepositional participles instead of prepositional infinitives, (34a),participles as complements of verbs which in AG were construed with the infinitive,(34b), and infinitive as complement of verbs which in AG were construed with theparticiple, (34c):

(34) a. Diafor

tothe.acc.sg.neut

emei.acc.sg

metrio:smediocrely

ekhonta.having.masc.sg.acc.act

‘Because I am in mediocre health.’ (P. Lips.108.5–6, 3rd c. AD)b. Sy

you.nom.sgikanoscapable.nom.sg.masc

e:be.2sg

dioiko:n.managing.masc.sg.nom.act‘You are capable of managing.’ (P. Cair.Zen.59060.11, 257 BC)

c. Tynkhaneishappen.2sg

ekhein.have.inf.pres

‘You happen to have.’ (P. Grenf.ii.57.8, 168 AD)

Of course, none of the “interchanged” constructions appearing in the papyri are foundlater, i.e. articular participles are very rare,27 and there are no verbs which prefer theparticipial over the AG infinitival syntax; however, there are several verbs which preferthe infinitival over the AG participial syntax (cf. Jannaris 1897:493), something whichgoes hand-in-hand with the general reduction in the uses of the participle. What is

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.26 (1656-1722)

Io Manolessou

more, the infinitive was also undergoing change and weakening in the same period.Especially the declarative infinitive (corresponding to oti (‘that’) complement clauses),had all but disappeared by the start of the medieval period, when the first instances ofthe gerund appear (cf. Jannaris 1897:572–574; Mackridge 1997). Thus the confusion ofparticiple and infinitive cannot have been the cause, but rather the result of the evolu-tion of the former towards the gerund. An additional indication of the break-down ofagreement between the matrix and the participial clause are the multiple examples offaulty agreement of the participle with the constituent immediately adjacent to it, andan indication of the more clearly verbal status of the participle is its use in conjunctionwith finite form (for both phenomena cf. Section 2.3).

Step III. If the participle is a non-finite verbal element independent from the ma-trix clause, it need have no agreement at all – therefore, its form becomes fixed, inthe form most frequently used. It is here that morphological considerations can play arole: not to motivate the freezing of a form, but to explain which particular form it willtake. In this respect, one should bear in mind the evolutions described in Section 3 forRomance and Slavic: in each case, it was a different case-form of the present active par-ticiple that constituted the origin of the gerund; in some cases it was the nominative,in others the oblique form.

The -onta ending had by then become the most frequent one because: (a) it was anaccusative ending, and the accusative was by far the most common case, as it becamemore and more the default oblique case, due to the loss of the dative and the restrictionof the genitive to adnominal usages (Horrocks 1997:122); (b) conjoined participles, ifoblique, would almost never be co-referent with a non-primary term in the clause,such as an indirect object or a participial complement (cf. Whaley 1990); and (c) the-onta ending had spread to the neuter singular as well, as described in 2.3.

On a more speculative level, considering also the fact that the consonant-stem 3rddeclension was passing over to the a-stem 1st declension due to its formal identity inthe accusative case (cf. Hatzidakis 1892:379–380), even the participial genitive ending,could, at some point in the Medieval period, have passed from -ontos to -onta, whichwould then be the unique oblique ending of a 1st declension form. The example below,could, e.g., be interpreted as an absolute participle in the genitive case, (35):

(35) Syyou.nom.sg

autosself

pantaeverything

hyperthemenosputting.aside

e:ke,come,

ekeinu:he.gen.sg

tothe

sonyour

ergonwork

poiu:nta.doing.acc.sg.masc.act

‘Put everything aside and come yourself, letting him do your work.’(P.Oxy.120, 4th c. AD)

Another potential piece of evidence for the existence of absolute genitive participles in[-onta] is the existence of gerunds with genitive subjects in MedG and contemporaryMG dialects such as Cypriot and Cretan, as in (20) and (21).

A further contributing factor in the preference for the -onta oblique ending musthave been the final vowel -a, which is an ending characteristic of adverbs: superlative

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.27 (1722-1766)

From participles to gerunds

(arista ‘best’, takhista ‘fastest’) and irregular adverbs (mala ‘well’) end in -a since AGtimes, and this form becomes generalised for all adverbs in the early MedG period.28

The external similarity of the oblique masculine (and neuter) participle to an adverbmust have promoted the possibility of its being interpreted as an indeclinable adverbialmodifier (for this view cf. Hatzidakis 1928 and Horrocks 1997:123). The adverbialinterpretation of the participle was strengthened by the fact that, as was discussed in2.2, it is possible, since the time of the Koine, to observe a gradual limitation in the usesof the participle – though not in its frequency –, as some of its meanings are graduallyreplaced by finite subordinate clauses.29 In any case, the adverbial use is considered,in standard Grammars, to be the main function of the participle even from AG times(Schwyzer 1950:387).

Summing up, the change from participle to gerund could be interpreted, for allthe languages involved, as originating in the domain of the adverbial participle: thiswas first analysed as an independent participial clause without reference to the matrixclause, fulfilling its agreement requirement in a local domain, and then as a non-finite,exclusively verbal non-agreeing element, fixed in the most frequently appearing form.

. Implications for syntactic theory

The above account of the consecutive stages in the evolution of the gerund and themotivation behind it have repercussions on our conception of gerundival and particip-ial syntax. The discussion does not aim to innovate in current views of Verb Phrasestructure. Rather, it aims to tabulate the implications of the historical research con-ducted above for the extant proposals concerning the representation of MG gerunds(Rivero 1994; Tsoulas 1996; Tsimpli 2000; Sitaridou & Haidou 2002), and to constitutea stepping stone for further theoretical elaboration on this topic.

. The status and external syntax of MG gerunds

The structural position standardly assumed for gerund clauses is that of adjuncts toone of the verbal projections of the matrix clause, e.g. VP or IP (Tsoulas 1996:445;Spyropoulos & Philippaki 2001:157; Pires to appear) or even CP (Tsokoglou & Kleidi2002:279). On the other hand, an analysis of gerunds as adverbial modifiers in linewith current analyses of adverbs such as Alexiadou (1997) allows one to capturethe connection between gerunds and adverbs on the one hand, and participles andadjectives on the other in a more systematic way.

According to Alexiadou (1997), adverbs and adjectives are in reality manifesta-tions of one and the same category, with standard similarities and differences. Theadverbial ending -ly (or MG -a, -os) is in reality an agreement marker with the verb,equivalent to the case endings of the adjective, which mark agreement with the noun.A corresponding situation obtains with gerunds and participles in MG, i.e. the de-

Unc

orre

cted

pro

ofs

- J

ohn

Ben

jam

ins

Publ

ishi

ng C

ompa

ny

JB[v.20020404] Prn:24/11/2004; 14:41 F: LA7608.tex / p.28 (1766-1829)

Io Manolessou

scription proposed for the nominal domain can also apply to the verbal one: theparticiple can be informally termed as the “verbal adjective”, and the gerund as the“verbal adverb”, with the ending -ontas being interpreted as an agreement markerwith the verb.

In more detail: Adjectives and adverbs form a single category. The category A canbe realised either as an adjective or an adverb, depending on its location. Thus, if it islocated in a verbal Specifier (Tense, Aspect etc., according to meaning) it is an Adverb.If it is located in a nominal functional Specifier (which hosts the agreement featuresof the noun phrase), it is an adjective. Both realisations of A enter into Spec-Headrelationships with the corresponding lexical head, V or N, resulting in the first case inthe licensing of the adverbial ending and in the other in agreement with the noun.