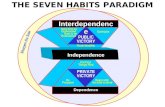

TEAM BUILDING. INTERDEPENDENCE Task Interdependence Goal Interdependence Feedback and Reward.

From Dependence to Interdependence (2006)

Transcript of From Dependence to Interdependence (2006)

Latin America R. James Ferguson © 2006

Lecture 12:

The Quest for Stability - From Dependence to Interdependence

Topics: -1. Societies in Transition2. Partial Achievements, Partial Failures3. Leverage Towards a Better Future4. From Dependence to Interdependence5. Bibliography and Resources

1. Societies in Transition

In many ways, the countries and societies of Latin America can still be viewed as nations in transition. Although the key elements of statehood have been developed for almost two centuries of independence (see lectures 1 & 2), the main historical and economic forces are still reshaping conditions in much of the region, in part through transition to electoral democracy, more participation based societies, and in part via the opening of major national economies towards regional trade areas (e.g. NAFTA, CAFTA, Mercosur and the proposed FTAA), and in general towards the reduction of barriers to global trade flows. This makes Latin America politics very much a part of the global network, even as the retains its unique cultures, diversified communities, and remote, partially integrated rural and indigenous societies.

This means that much remains to be done to meet the aspirations and needs of Latin Americans, and in reaching stable conditions of relative prosperity across the region. Likewise, the path towards modernity taken by Latin America has been somewhat different to that found in Europe, North America and Australasia, impacting on current debates about national identity and valid aspirations for the future (see Larrain 1999). At present it is not possible to build a narrow Latin American identity on notions of indigenous revival, nor just on the Ibero-American tradition, nor on the Christian/Catholic traditions (Larrain 1999, p183). The future goals for the region, though having high consensus on some broad outlines, e.g. continued growth and greater democratisation, are still intensely debated. Issues such as social justice, wealth distribution, civil society engagement, the role of the military in resolving political disputes, and the degree to which Latin America should remain under the past 'tutelage' of the U.S. and Europe are still highly controversial (though this is turning towards a more complex engagement model, in part driven by US security concerns and by Mercosur's dialogue with the EU). Likewise, several different models of regional engagement based on different trade alignments (including Mercosur, the proposed FTAA, NAFTA and CAFTA groupings) have been intensely debated through 2004-2006, in part based on differential regional benefits, and in part on the interest of large key players including the U.S., Brazil, Argentina (see lectures 9 & 11) and tensions in energy alignments generated by Venezuela foreign policy efforts under President Chavez.

Lecture 12 1

2. Partial Achievements, Partial Failures

It is possible to summarise the major trends of Latin America through accessing the strengths and weakness of key developments within the region. It some cases, policies can be viewed as both partial success and partial failures, depending of the level of expectation behind a given reform or program.

A sample of successes and partial successes might include: -

1) Latin American high art (literature, films, classical composition, and Latinjazz music) and popular culture (popular music, television) remain extremely vigorous and have become a major export that also heightens the prestige of the region (for examples, see lectures 3 & 4). As we have seen, names like Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges, Isabel Allende, Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda have become major literary figures recognised globally (for samples, see Caracciolo-Trejo 1971; Skidmore & Smith 2001, p421). Although this flow of cultural influence does not match North American influence, it has begun to have a clear global dimension. At the very least, in spite of the strong market for American pop culture, this has meant that a strict nordomanía (love of everything North American) is no longer favoured among educated Latin Americans (Larrain 1999, p189). Likewise, the large-scale diaspora of Latin Americans into the U.S. (and to a lesser extent Europe), has begun to shape a strong 'Latino' element in North-American politics and cultural tastes, e.g. large Mexican, Cuban and Haitian ethnic minorities. Even Jamaica and the Dominican Republic sent around half a million migrants into the U.S. over recent decades (see Klaks 1999, p120). Such groups form transnational linkages that have serious implications ranging from remittance returned to home countries, impact on exile groups on political relations (e.g. Cuban exile communities), and changing patterns of popular culture.

2) Latin America 'has also made a great contribution in the field of race relations' with a 'relative social harmony' that, for all its problems, is still an achievement (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p422). Here the mestizos of Mexico, Central America and the Andean region, and the mulattoes of Cuba, Brazil and the Caribbean have demonstrated considerable social mobility (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p422), in spite of ongoing forms of economic and educational disparity. The mestizos in particular remain an important component of modern Mexican identity (see lecture 3) and form one focus of social reform (see Larrain 1999, p189). However, limited, masked forms of racism do continue, more in the

2

'exaggerated valuation' of whiteness, 'whitening' policies that seek to discount indigenous or African descendent, and in remaining negative visions of 'Indians and blacks' (Larrain 1999, p198). Even in Brazil, the myth of a ‘racial democracy’ masques subtle forms of discriminations that have only slowly been addressed through ‘affirmative action’ programs.

3) In general terms, countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and to some degree Chile and Colombia have become successful industrial producers of automobiles, machinery, consumer goods and electrical components (see lectures 3, 6, 8, 11), as well as a limited place in aircraft and armaments production. This has often done in connection with major transnational firms that remain sensitive to global markets and to financial flows, linking these sectors in part into near global level of design and production, with Mexico, Brazil and Argentina playing major regional roles. However, Brazil and Argentina still have problems coordinating their production within Mercosur frameworks, and have not yet created a balanced regional productive base for small partners such as Uruguay and Paraguay (see lecture 11).

4) A partially successful strategy has been the idea of finding effective market niches in the current global system whereby some existing advantage can be utilised. For example, Dominica has been able to use low labour costs to be boost a range of non-traditional activities ranging from assembly operations and data processing to the production of seafood and flowers (Klak 1999, p114), and Costa Rica 'has benefited from the smooth flow of microelectronic products' and circuits-assembly production (Stanley & Bunnag 2001). Panama has also sought to become a major internet host for Latin America, with new optical fibre networks able to provide for 10,000 network servers (BBC 2001a). However, such niche specialisation and efforts at diversification can also lead to new vulnerabilities (see Stanley & Bunnag 2001; Klak 1999). As experienced in Jamaica when it entered the data-processing sector: -

The development prospect of this sector entails incorporating local labor and nurturing local firms to take advantage of expanding opportunities in the global data-processing industry that earns US$1 trillion yearly, of which information-processing services is a component. Mullings (1995, 1998) draws on a detailed analysis of the rise and fall of information services in Jamaica to explain why this industry, which has real potential (however narrow) for growth in employment wages, managerial expertise and backward linkages into the local economy, has stagnated in terms of all these criteria. She identifies the problem in terms of inadequate state support for local firms; continued policy steering and dampening by traditional, nondynamic private elite; investment fear on the part of foreigners; and an extremely narrow role

Lecture 12 3

allotted to Jamaican firms and workers by US outsourcing firms. Rather than propelling Jamaica to a heightened position in the international division of labour as the neo-liberal model predicts, the information services sector has slumped and entrenched the gender, class and international inequalities that have long characterized this peripheral capitalist nation. (Klak 1999, p116)

5) Some Latin American countries have demonstrated partial successes in the creation of grass-root organisations and a level of solidarity among the urban poor or mobilised rural groups, e.g. in parts of Mexico, Bolivia and Brazil. This has been viewed by Anibal Quijano as an alternative type or ‘reason’ that can mobilise collective effort and reciprocity (Larrain 1999, p194). At the same time, the overall ability of Latin American civil society to influence governments remains limited (Larrain 1999, p199). There are limits to how far the ‘resources of the poor’ can overcome an overall decline in local employment in dislocated communities (De La Rocha 2001). In other words, partially successful social mobilisation does not always lead to firm, long-term outcomes for the poor or indigenous groups (as in the Chiapas area of Mexico and the poor in Venezuela). Overall growth in the national economy within competitive regional and global trading conditions still remain one essential (but not sufficient by itself) factor for positive social change.

6) Perhaps the biggest success for the region has been the increasing trend towards democratisation, in spite of some limitations in the depth of democratic culture in the region (see lecture 9). Thus democracy is now the norm in Latin America, even if it is disturbed by past financial instability (Argentina), by perceptions of corruption (Brazil), by presidentialism and political polarisation (Venezuela), by ongoing political violence (Colombia), by a 'deficit in collective leadership' (Cooper & Legler 2001), and by the bitter struggle for a more open media over the last thirty years (see Look 2004). Thus it can be noted that: -

In spite of the above mentioned weaknesses of democratic institutions in Latin America, in spite of corruption, terrorism and human rights violations, the democratic system has recently emerged as the only legitimate framework for political action. Even in Central America, where authoritarianism, open or otherwise, has been endemic for many years, there has been a strong movement towards democracy in the 1990s (Larrain 1999, p201)

7) International wars within Latin America are now a thing of the past, and borders throughout the region have been largely stabilised (see lectures 2, 9). On this basis, Latin America has been able to evolve a number of relatively effective regional organisations, including the OAS,

4

Summit of the Americas, the Rio Group, and Mercosur. Such organisations are crucial in meeting the regional challenges of globalisation and democratisation (Orango 2000). However, as we have seen, no single organisation or group of these organisations really provides comprehensive governance, requiring a need for further institutional reform. Likewise, Mercosur will need to go through another round of innovation if it wishes to the main driver of economic cooperation in South America, e.g. the proposal of the single currency for the region, or for a supranational parliament, ideas being considered in Brazil (Sader 2003; Pang 2003; see lectures 5, 11). As we have already seen, from 1995 Mercosur hoped to create a South American Free Trade Area (SAFTA), a vision which has gained some reality via negotiations with Chile, Bolivia and Peru, and the rest of the Andean Community of Nations (CAN, also known as the Andean Pact) through 2004-2005. However, at present Mercosur itself has had serious problems in meeting the needs of Uruguay and Paraguay, and seems to concerned with Argentina-Brazil internal balancing to provide a strong core for wider integration, at least in the near future.

8) Economic reform has continued to generate increased growth in GDP, but this may not be enough to ensure political and social stability. Estimated extra growth from reforms was suggested to be in the range of 1.9-2.2 percent, though this may need to re-estimated at only 1.3% for the 1991-3 period, and only 0.6% for the 1997-1999 period (Lora & Panizza 2002, p12). Economic growth is important, but has not generated all that was hoped for in terms of balanced social gains (Petras 1999; see further below). In general terms, only countries with strong institutions, good rule of law, and effective regulatory frameworks can easily benefit from the reform process - otherwise a post-liberalisation crisis may occur, e.g. via a weak or poorly controlled banking system, problems that in part generated the Mexican and Argentinian financial crises (Lora & Panizza 2002, pp13-17). Furthermore, at this rate, even with sustained growth at around 3%, it would still take most Latin American countries as much as 50 years to reach the current standard of living of OECD countries (Lora & Panizza 2002, p21).

Partial failures, moreover, continue to hobble the development and prospects of many Latin American states. We can see this in a number of factors: -

1) Ongoing poverty remains a problem for the region, especially in depressed rural areas and in the informal

Lecture 12 5

settlements that have grown up around all the major cities. Although Latin America and the Caribbean has only 6.5% of the total of world's poor (via the rough measure of income of below $1 a day), almost 20 million new poor were added to those in Latin America during the period 1987-1998 (World Development Report 2000-2001). Poverty rates across the region vary from 20-60%, with Central American states and Haiti falling in the top of the range (Klak 1999, p112). By one estimate, 214 million in the region lived in poverty, and 9.8 (18.6%) million were destitute through 2001 (Sader 2003). At the same time, we should not exaggerate this into an image of overall poverty. In terms of the Human Development Index (HDI, including life expectancy, literacy, education, and per capita purchasing power factors), Central America and Caribbean, for example, fall in the top two thirds of the rating (Klak 1999, p103), with the exception of Haiti. Likewise, although growing GDP can slowly reduce average poverty, vulnerable groups may be worse off, income differentials can increase, and there is no guarantee of distribution to the poorest levels (Lora & Panizza 2002, p20). Thus the gap between rich and poor continues to increase in Brazil, even as the bottom level has had income levels lifted to some degree. Figures from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean 'show that the proportion of Latin Americans living in poverty decreased from 41 percent in 1990 to 36 percent in 1997' (Fraser 2000). Thus poverty and inequality reduction remained major themes in the 13th Latin American-Iberian Summit, held in November 2003 (Xinhua 2003b).

2) Economic reform, though occurring throughout the region and generating continued growth, has uneven effects and has not yet created stable, balanced economies, though considerable improvement has occurred in countries such as Chile over the last decade. The state-guided or hybrid capitalism that was common in much of the region through the early and mid-20th century, whereby the state is a major player in investing and controlling capitalistic development, has been rolled back with a wave of uneven privatization, e.g. in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p418). From the mid-1990s, for most of the region (excluding Cuba and Venezuela), neo-liberal policies have dominated, with an effort to create open economies that are viable under conditions of accelerating economic globalisation. Thus import duty levels on average fell from about 40% in the mid-1980s to approximately 10% in the late 1990s (Lora & Panizza 2002, p4).

6

The neo-liberal model implies a limited role for state economic activity, with a key role for the state in 'promoting exports and competing for investments' (Klak 1999, p100), but otherwise leaving as much as possible to market forces. Unfortunately, progress in this area has not been even, with privatisation schemes not always being effectively carried through, and with major problems for these economies as they are de-regulated, e.g. for the private banking systems of Mexico and Argentina. Likewise, privatisation also tends to create at least temporary increases in unemployment, e.g. over 110,000 workers were dismissed in the privatisation drive in Argentina (Lora & Panizza 2002, p21). It seems likely that many of these were pushed into the informal sector (Lora & Panizza 2002, p21), and in effect will receive lower wages and become relatively under-employed, and least in the short and medium term. Although defensible in term of long term gains, this trend indicates the possibility that rapid economic reform can generate new cycles of political turmoil, which eventually makes the ongoing economic reform process itself unsustainable (see Lora & Panizza 2002). Thus, in the case of Argentina, though it seemed to be one of the most progressive in terms of economic reform (including trade liberalisation, financial reform, privatisation, labor market reform, though not in the area of effective tax reform), the country still went through a massive currency crisis that spilled over into political crisis through 2001-2002 (see Lora & Panizza 2002, pp2-3). Problematic areas included difficulties in tax reform, and the elimination of corruption from privatisation schemes. Thus, public perception of reform, especially among the middle classes, became more negative: -

Dissatisfaction with the economic situation pervades the region. According to a Latinbarometer public opinion survey of 17 countries in the region, two of every three Latin Americans believe that economic conditions are bad or very bad, only one in four believes that the economy will improve in the future, and three of every four believe that poverty has increased in the last five years. (Lora & Panizza 2002, p8)

3) Although there has been a renewed social awareness of the rights and needs of indigenous people, and some selective efforts to help native languages survive in a secondary role, this has not translated in large-scale sustainability of native peoples economically and socially. In general, 'urbanization in Latin America is engulfing or liquidating the rural and provincial', and Indian cultures are only likely to operate strongly in parts of the Andes, southern Mexico, and Guatemala (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p420), and in a more fractured way in small pockets of the Amazon. However, indigenous groups have been able

Lecture 12 7

to mobilise grass roots and international attention to a wide range of social and ecological problems that need better management within Latin America as a whole. These movements have been particularly important in Ecuador and Bolivia (Sader 2003; Barthélémy 2003), as well as of great significance in Mexico and Guatemala. One example of this have been indigenous protests against a new development plan, the 'Puebla-Panama' Plan (PPP), that has been viewed as a new form of colonialism, constructing 'a vast network of roads and communication networks, several power plants and extensive tourism projects' (Ecologist 2002). This plan is part of a Central American 'infrastructural development plan designed to prepare the region for the Central American Free Trade Agreement' (Engler 2003), plus reduce the impact of the Chiapas rebellion on the southern areas of Mexico. Lack of consultation and negative impact on local farmers were reasons for the rejection of this project by many grass root organisations: -

But the PPP's success depends on indigenous Mexicans' willingness to abandon their rural homes and farms, something they may well refuse to do. Shortly after the PPP was officially presented, representatives of 131 organizations from southern Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador gathered in Tapachula, a city on the Chiapas-Guatemala border to develop a coordinated response. In a joint statement they said, "Given that any development plan must be the result of a democratic process and not an authoritarian one, we firmly reject the Plan Puebla-Panama .... We condemn all strategies geared toward the destruction of the national, peasant and popular economy, and/or food self-sufficiency." (Call 2002)

However, through 2005, PPP has continued to make progress, in part because of the real need to link energy production and electrical grids in the region, where electrical prices have begun to increase in the order of 5-20%, a real problem for poorer communities (NotiCen 2005; see further below)

Another example where indigenous groups have had a strong impact is Bolivia, where Evo Morales won elections in late 2005 with an absolute majority, in part on the basis of the votes of the poor and indigenous groups, but also because richer groups in the east of the country and middle class elements feel his rule may be less than corrupt than previous governments (Economist 2006). This has been interpreted as a move toward populist government, in part due to government problems that reached breaking point through 2002-2004: -

Since the resignation of President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada on 17 October 2003, Boliviahas entered a phase of populist government that is transforming the country's political landscape.

Civil society and the indigenous majority have, for the first time in Bolivia's history, found their political voice. . . .

8

. . . Bolivia is the poorest country in South America, with 10 per cent of the population owning 90 per cent of the country's wealth. It is profoundly divided between the minority white and mestizo (mixed race) population, which controls the majority of the country's resources, and the indigenous Indian majority, many of whom are homeless and live on less than US$2 a day. . . .

Sánchez de Lozada's second term in office, which began in September 2002, was a disaster for the country as a whole. At the election, he won only 22.46 per cent of the national vote but was re-elected as president following days of wheeling and dealing within Congress. He eventually took office with an approval rating of a mere nine per cent and, in February 2003, unveiled a new income tax that was widely interpreted as being anti-poor.

The tax lead to widespread riots in the streets of La Paz during which rioters were aided by large numbers of police who joined in an attack on the presidential palace. The military came to the defence of the state and, in the ensuing carnage, 31 people were killed and at least 100 seriously injured. When the president stood down the military, 24-hours of mob rule followed.

In September 2003, violence erupted again following the announcement that Bolivia would export natural gas to the US and Mexico through a port in Chile, its historic rival. Protesters from El Alto, the impoverished city above La Paz, blockaded the capital. For at least three weeks, the country teetered on the brink of anarchy. (Smith 2004)

For a time ‘Sánchez de Lozada was replaced by his Vice-President, Carlos Mesa, a television journalist and historian’ and Bolivia ‘maintained a degree of stability’ (Smith 2004). Through 2004 a referendum on gas exports backed greater government control of energy resources, and a deal was signed to allow Bolivia to export through a Peruvian port (rather than Chile), but mass protests of fuel prices and local control of energy resources continued through January-June 2005 (BBC 2005). Former President Mesa resigned in June 2005 on the basis of the country being ungovernable, leading to a short caretaker president (Eduard Rodriguez), with elections thereafter (BBC 2005).

Bolivia, in spite of having South America's second largest gas and oil reserves, remains one of its poorest in the region, and has had to cope with the issue of the tradition growing of coca by indigenous groups (Economist 2005). Morales speeches over the last several years have spoke of nationalising the energy sector, but living up to the contracts made with companies and other countries (such as Petrobras of Brazil), as well as the plan to de-criminalise the growing and use of coca, the leaf, thus ending the forced eradication of the crop, while at the same time still banning cocaine, the refined product (Economist 2005; Economist 2006). However, this could lead to a 'decertification' of Boliva's anti-drug efforts, and reduced aid and trade flows (Economist 2005). Morales' party, the Movement to Socialism (MAS) was based on unions, social movements, and his own coca growers union, has promised to boost the guidance and ownership

Lecture 12 9

role of the state in the economy, finance new smaller firms, and promote the use of new technology in manufacturing, agriculture and mining sectors, as well as triple the minimum wage to around $190 a month (Economist 2005; Economist 2006), but will thus need to control government spending, possible future inflation, and also find ways to maintain some flow of investment into the country. Morales will also need to balance the power of the central government with the new elected prefectos (governors) of the 9 semi-autonomous departments, who want a greater share of control of government revenues: they control only around 25% at present (Economist 2005). From June 2006 MAS also wishes to proceed with a constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution, perhaps allowing some land redistribution and greater indigenous rights. Morales, in spite of seeming to lean towards a Venezuelan model, also needs to keep positive relations with the US to support a small manufacturing sector (mainly clothing and jewellery) exporting under favourable conditions into the US through 2006, but best supported in the long run by some kind of free trade agreement, with the US also offering some $593 million in infrastructure development aid (Economist 2005). This sector is worth around $150 million in exports and some 100,000 (Economist 2005). Likewise, foreign aid, largely from the US, accounts for a total of 10% of GDP (Economist 2006).

4) Certain strategies have been used to try to boost the well-being of small farmers in Latin America. Rural poverty remains a major problem for much of the region. One of these has been the transfer from traditional crops (sugar, coffee, bananas) to non-traditional agricultural exports (NTAEs) such as tropical fruits, vegetables and flowers (Klak 1999, p115). Though useful in some areas, the NTAEs have not been a sweeping solution to rural poverty for small scale producers, largely due to highly competitive markets, costs of production and transportation, and the need for high levels of pesticides for these specialised crops (Klak 1999, p115). Likewise, as we have seen, the redistribution of land has often been limited, or when it is done does not necessarily produce viable farming communities, e.g. in Mexico and Brazil. In the end, agricultural exports remains highly competitive and do not automatically guarantee social stability for small farmers.

5) The ongoing problem of drugs, including growing, production, taxing, export of the product, and the related issues of political violence, corruption, money laundering, violent crime, and policing. This is a destabilising factor for the Andean nations, as well for Mexico, Brazil and Haiti. To date, the market for drugs remains robust, and policing often simply

10

moves the problem to another part of the hemisphere. Likewise, the militarisation of the response to this problem begins to look like another round of counter-insurgency warfare in Colombia, and can also draw in nations along the Amazonian border into a military response to the problem (see lectures 7 and 10). There has been a trend for the militarisation of social problems in some of these countries, at first through use of armed forces first against Communism, then against the drug problem, and most recently against the threat of terrorism.

6) Though defence spending has dropped through much of the region, this military option has meant that the appropriate role for armed forces has not yet been fully defined (see lecture 10). U.S. military support and training for Latin America armies in the past has tended to compound this problem, while Argentinian moves for a more cooperative defence system in the southern cone of South America has not yet emerged as a successful policy (see Pion-Berlin 2000). The Southern Cone, and Latin America as a whole, have not yet emerged as a coordinated Security Community that has secure prospects of peaceful transition, though the southern states are sometimes viewed as a nascent or emerging zone of Cooperative Security (see Tickner & Mason 2003).

7) The environmental record for Latin America is also extremely mixed. Despite increased social awareness, some slowing of the impact on the Amazon forest and improved management of preservation areas, as well as some effort at resource planning in Chile, Latin American farming and production has not yet moved to an environmentally sustainable mode. Long term damage to urban and rural environments will constitute a major remediation cost to these societies in the future (for the impact of new farming methods on deforestation levels, see Klepeis & Vance 2003). Likewise, provision of simple necessities such as clean water and sanitation remains problematic for many cities in the region (see Nunan & Satterthwaite 2001). Even a Chile, a country with strong economic and democratic credentials, the success of the country has been based on a highly extractive approach to resources, an approach only being modified in recent years, with the economy based on mining, extraction of forest resources, intensive agricultural and fishing patterns, with some shift to fish farming and plantation timbre (for a critique, see Carruthers 2001). Likewise, in Ecuador, in spite of the wealth boom promised by increased oil exports, there were controversies over a lack of community consultation and environmental assessments into major new pipelines, leading to severe political turmoil and intense bargaining over these issues through 1993-2004 (see Barthélémy 2003), though this has been partly modified through the new use of new pipeline technologies.

3. Leverage Towards a Better Future

It can therefore be argued that continued transition is required in the Latin American context. It is important that this transition be guided both towards sustainable social costs and towards genuinely productive outcomes. Here, certain

Lecture 12 11

key areas of investment and political management may help maximise human outcomes in the 21st century. These areas of leverage include: -

1) Continued investment in education, both in the technical/professional areas and the general awareness of populations who need to become 'stakeholders' in their national futures even during times of instability. Education does not automatically guarantee political reform, e.g. Argentina and Chile had some of the highest educational levels in the region but still succumbed to military dictatorships in the 1970s (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p399). Nonetheless, educational gaps remains problematic for the development of all the poor nations of Latin America, and even remains a problem in Brazil, where highly uneven patterns of education are found (Gordon 2001, p133). Pessimism about the future of these nations, especially among the middle class and educated groups, can make it very hard to mobilise the social resources needed to ensure a better future.

2) Demographic transition will also continue to have a selective effect on Latin America. In the past, rapid population growth may have been needed to build viable nations, but soon became a major burden on the resilience of nations to provide infrastructure, resources and education to their growing populations, e.g. in Brazil and Mexico. Today, birth rates have begun to slow throughout much of the region, especially in urban areas. Thus population growth rate for Brazil fell from 2.0 percent in 1980-1990 to 1.4 percent in 1997, while in Mexico growth rates declined from 2.3 to 1.8 percent (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p412). Basically, urbanisation, increased living standards (or the aspiration to them), and education will be likely to continue to restrain growth rates. However, a large number of young people are now trying to flow into the workforces, creating an enormous challenge that will not be fully met by developing economies of the region in terms of full-time, stable employment. For example, in Mexico about 1.4 million new job seekers join the labour market every year, but in the best of years perhaps only about 1 million new jobs can be generated (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p412). Up to half of those in the growing urban conglomerations will either remain unemployed, or seek informal employment in the huge informal sectors that have developed (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p413). In general terms, however, population growth will being to slow, and a large workforce will be available to Latin American countries in the next two decades. Depending on wider economic conditions, this short term problem may become a long-term asset, if accompanied by education and skills-development.

12

3) The problem of external debt and debt servicing still remains a major problem for many of the Latin American crises. Although the great debt crisis of the 1980s has been partly managed through 'debt renegotiation, export growth, and return of capital inflow', one in every three dollars generated by Latin American exports still goes back to merely service earlier loans (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p413). Thus, in 1996 total Latin American and Caribbean foreign debt stood at $622 billion, more than that of 1987 (Klak 1999, p109). The problem remained critical if marginally manageable: -

By the 1990s, when the flow of capital to the region had significantly changed in composition (equity rather than debt), the IFIs [International Financial Institutions] trumpeted the end of the debt crisis, notwithstanding the fact that the majority of countries still had to service their external debts at a level (50 percent of export earnings) that the world bank defined as "critical." However . . . the problem of the external debt, although now regarded as "manageable," is by no means over. By 1998, the total external debt held in Latin America climbed to 698 billion dollars, an increase on . . . the debt outstanding in 1987, the peak year of the debt crisis. What is significant about this debt is not so much its size (about 45 percent of the regional GNP), but the sheer volume of interest payments made to U.S. banks and the huge drain of potential capital. In just one year (1995) the banks received 67.5 billion dollars in income from this source and, over the course of the decade, well over six hundred billion dollars - a figure equivalent: to around 30 percent of total export earnings generated over the period. (Petras 1999, square brackets added)

In this context, even well-intended efforts by agencies such as the IMF need to be carefully monitored for the level of debt they project into the future for countries such as Argentina. Fortunately, international institutions and foreign banks also realise the great dangers of a general debt default in Latin America as whole. The IMF in particular, has tried to improve its responsiveness to the social dimensions of financial crisis, though debts are still carried forward into the future (see below).

4) The vision of immediate solutions through violent change has faded throughout much of the region. The optimism of Cuba's revolution, though having some social and educational successes within Cuba (see lecture 4), has not been found be a viable model for economic development for most of Latin America. Radical guerrilla forces remain strong only in Colombia, while more moderate forms of social rebellion found in Mexico and Brazil aim at providing benefits to landless and indigenous people. The turn away from revolutionary socialist solutions, partly based on external pressures, has been noted: -

Lecture 12 13

Thanks in large part to pressure by the United States and its allies, the list of Middle American countries that have undergone failed experiments with alternatives to mainstream capitalist development reads like an epitaph to Third World socialism: Guatemala 1945-1954 under Juan Jose Arevalo and Jacobo Arbenz, Guyana 1961-64 under Cheddi Jagan, Jamaica 1972-1980 under Michael Manley, Grenada 1979-83 under Maurice Bishop, and Nicaragua 1979-90 under Daniel Ortega. Enemies from within and without (mainly the United States) worked to capitalize on any of the inevitable errors in leadership and to sabotage these experiments before their developmental capabilities could be ascertained. (Klak 1999, p105)

In part, this turn around is due to the difficulty of building socialism within a capitalist world economy, as well as a sense of weariness in the struggle to find social justice within struggling economies. This can be further seen in the case of Nicaragua: -

By 1990 Nicaragua's war-weary voters rejected the Sandinistas in favor of the United States' preferred candidate, Violeta Chamorro. On her watch the country reversed policy direction and began what William Robinson characterized as 'a close U.S. tutelage in the process of reinsertion into the global system.' Nicaragua's USAID program leapt to become the world's largest, and included funds to replace Sandinista textbooks . . . By the late 1990s, more than half of all Nicaraguan workers were unemployed or underemployed. And the US$500 million dollars worth of international aid keeping the Nicaraguan economy afloat has made current conservative-populist President Arnoldo Alemán highly subordinate to the wishes of core capitalist countries. Despite Nicaragua's 'economic straitjacket,' however, it has managed to retain some meaningful vestiges of the Sandinista period. These include vibrant grass-roots activism, politically-astute citizens, gender equality laws, and autonomy laws protecting its culturally distinct Atlantic Coast people. (Klak 1999, p113)

However, at a more general level, Marxist, socialist (see Lemoine 1998) and popularist traditions (see lecture 6) have left a strong sense of social claims and popular mobilisation that Latin American governments cannot ignore, e.g. in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. Governments will need to meet some of these aspirations, or at least draw these mobilised groups into dialogue, if they wish to avoid future political and social crises.

5) Likewise, military regimes and dictatorial states have become discredited as long-term solutions to problems in the hemisphere. This means that more moderate forces can be mobilised towards patterns of productive activity or practical compromise, e.g. politics in Chile, or the pragmatic approach taken by strong labour movements in Brazil and Argentina (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p414). Most militaries in the region wish to position themselves in a more professional role, while still at some level wishing to guarantee the survival and stability of their home states. Although the 'shadow effect' of the military on politics and strong security agendas in the region (see week 9), there has been a

14

popular dis-investment in authoritarian solutions to political and social problems.

6) Religion has also been mobilised as a social and sometimes progressive force in many countries if Latin America, though this remains controversial. Thus the Catholic Church has been involved in land reform and monitoring human rights in Brazil, Chile, Central America and Haiti, while Castro has sought dialogue with the Vatican to reduce the partial isolation of Cuba. At the same time, the more radical aspects of 'liberation theology' have begun to be eroded from two directions (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p416). Under Pope John Paul II the Catholic Church has turned towards a more conservative social role, while throughout the continent Protestant and Evangelical movements have made serious inroads. Likewise, there has been a recent charismatic revival within the Catholic movement in Latin America, using television and other media to complete with the Protestant Pentecostal movement (see Chesnut 2003). Thus, liberation theology can no longer provide a main engine for social reform, though Churches generally remain important watchdogs on human rights and in providing care agencies that help the poor. They also have a role in shaping moderate left political parties, e.g. Christian Democratic parties (see Lynch 1998).

7) It now seems possible that a more sophisticated pattern of neo-liberal reform is being applied to Latin America. Traditional neo-liberal reform towards a market economy, called the 'Washington Consensus', was based on 'fiscal discipline, "competitive" exchange rates, the liberalisation of trade, inward investment, privatisation and deregulation' (Sader 2003, footnote 2). There is now debate about adapting this formula. Thus a recent study conducted in part through the Inter-American Development Bank Research Department has suggested that new lessons need to be derived from the last decade of structural reform including (adapted from Lora & Panizza 2002, pp21-23). Through 1997-1998, a group of Latin American thinkers developed a 'third way' aimed at creating a more humane form of neo-liberal economic development, called the Buenos Aires Consensus, though this was not fully adopted (Sader 2003). This aimed at creating a 'strong, active and healthy state', eradication of poverty and corruption, selective and effective privatisation which is not merely used to pay off foreign debt, and avoiding the creation of private 'semi-monopolies' (Andres 1998). Elsewhere, these approaches are termed 'post-neoliberal models' (Sader 2003). Likewise, the regular social forums at Porto Alegre have been an important

Lecture 12 15

way of focusing on the need for cooperation on a host of social issues that support political and economic stability (Sader 2003). It must be remembered that sizeable sections of export revenues end up paying for interest on ongoing debt, e.g. in Ecuador, large proportions of revenues from increased oil production ended up paying interest on foreign debt, e.g. in 2000 of $2.4 billion of revenues through state-owned oil companies, some $1.3 billion went to debt servicing (Barthélémy 2003).

8) Some of these ideas are now converging on creating what might be calle a 'Washington Consensus' plus governance reform process that will lead to more stable outcomes (adapting Lora & Panizza 2002, p22, and the Buenos Aires Consensus): -

a. Structural reforms and economic growth are 'a necessary but not sufficient condition to improve the economic well-being of the poor'.b. Structural reforms are not enough by themselves to cause high growth as compared to the fastest developing economies.c. Not all market reforms and privatisation programs are successful - without strong legal and regulatory frameworks market or financial collapses can occur.d. Strong institutions are needed to manage change, including strong public organisations.e. Equity and social issues need to be considered if economic reform is to be sustainable, which includes the continued political will to support reform.f. Alongside market reforms, social reforms need to begin to reduce 'economic vulnerability, poverty, exclusion and inequality'. Put simply, poverty and inequality are bad for growth (Lora & Panizza 2002, p22).

It seems, then, that the 21st century has opened with a much deeper knowledge of the processes of structural change available to decision makers and institutions. Whether this will be mobilised for a better future will in part rely on the ability for Latin American countries and social groups to become a partner in global processes and decision making, rather than just a subject (or victim) of them.

4. From Dependence to Interdependence

As we have seen, Latin America was first subject to conquest by Europeans, then dominated under a colonial system which exploited mineral, agricultural and human resources as part of the emerging global capitalist system (see Braudel 1986). Even when nationalism became to shake off the control of Spain (and more gradually Portugal), these new states were still linked into the emerging world economy as primary producers and secondary markets. Thus it is possible to conceptualise the

16

current period of globalisation as simply an intensification of the centre-periphery that have been running for over four centuries. Thus it must be recognised that the Caribbean, for example, has been subject to economic control by outside powers from the 1500s onward, with all plantation crops oriented to exports and almost all other necessities imported (Klak 1999, p110). Thus, current '"globalizing" trends represent another round of powerful external influences for a region historically shaped by exogenous decisions and events' (Klak 1999, p110).

This was particularly true for the smaller countries of Central America and the Caribbean, which became highly vulnerable as export-dependent, small states: -

Within Latin America, Middle American countries have over time remained especially vulnerable owing to their distorted, underdeveloped and peripheral economies. As the example of bananas illustrated, these countries have overemphasized a few export-orientated primary products, particularly agriculture and in a few cases mining. They have also relied on imported industrial and commercial goods and on foreign capital and expertise to feed people, to service industry, and to finance internal capital expansion. (Klak 1999, p108)

From the 20th century onwards, larger Latin American countries sought to build their own modern industries, and to reverse this dependence by producing their own manufacturing through import substitution industrialisation (ISI) programs whereby the state would have a central role in planning, especially in areas of heavy industry and energy production (Klak 1999, p100). Although this effort did produce a large industrial base in countries such as Mexico and Brazil, this program still required strong imports of technology and key components, and did not necessarily result in highly competitive economies when compared to those of North America, Europe, and Japan. In part this is due to the relative subordinate role of manufacturing (Gereffi & Hempel 1996), compared to areas such as services, design, information, and financial resources that have become the new 'command' areas in the current period of financial capitalism.

Direct foreign investment, in particular from the U.S., Europe and Japan, has been crucial in building modern Latin American economies. Direct foreign investment, especially when combined with technological and skills transfer, can be crucial in buoying developing economies. At the same time, as we have seen in the case of Mexico and Central America, certain types of plants (the maquiladoras) can shift the pattern of industrialisation and employment in disconcerting ways, producing a new types of dependence (Ochoa & Wilson 2001, p7; Kunhardt 2001, p53; Cooney 2001, p55). Even more dangerous is the 'hot money' of portfolio funds which invests in the liquid assets of stocks, bonds, and leasing agreements (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p410). These funds can be rapidly pumped into a country if it is viewed as a good investment area, but also can be rapidly moved out if there is a perception of instability or better opportunities elsewhere. Hot money, for example, was directly implicated as a major factor in the Asian financial crisis, especially for Thailand (see Rosenberger 1997). Thus, although 'helpful in the short run (by improving the balance of payments and increasing foreign exchange reserves) such funds became a timebomb, ready to leave at the first sign of trouble. That is what happened in Mexico in 1994 and Brazil in 1998-99.' (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p410). There may have been some learning curve here since 1998 by investment institutions, e.g. there was little regional contagion from the Argentine financial crisis.

Lecture 12 17

These factors had led to the formulation of dependency theory, which was actively promoted from the 1950s down through the 1970s: -

Then, in the early 1950s, the pioneering economic work of the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA) focused on the existence of a center-periphery world system which favored the central industrial countries. According to ECLA's analysis those countries specialized in the production of industrial goods grew faster than those specialized in the production of raw materials and therefore the gap between central and peripheral economies was becoming increasingly wider. This is why it propounded the idea that the countries of Latin America had to modernize their societies by switching from raw material export-orientated economy to an industrial-led economy in order to lessen their dependency on the external demand for raw materials and to substitute for it the expansion of the internal demand. This meant for ECLA a change from a model of development 'towards the outside' to a model of development 'towards the inside'. The political and economic initiative to bring about modernization and industrialization had to be mainly in the hands of the state. (Larrain 1999, p192)

Ironically, though dependency theory could outline the problem for these developing states, it did not find a genuine solution to the problem. In a general sense, Latin American countries remained highly dependent upon and influenced by the 'foreign sector', including foreign investors and corporation, as well as international agencies such as the IMF, the World Bank (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p401) and the Inter-American Development Bank. At times, this foreign dependence could be highly helpful, e.g. in sustaining automotive manufacturing in Brazil and Argentina, or in stabilising currencies, e.g. help in stabilising the Mexican peso. However, in the long run this meant that Latin America remained dominated by the enormous power of the foreign sector, subject to shocks generated in the international system, and highly in debt to foreign institutions.

We can see some of these issues in the troubled path charted by Panama. Panama is a unique case in that its location at the isthmus linking two oceans made it of strategic interest to Spain, Colombia and the U.S. even before the Panama canal was built, first being used as a land route between naval ports, followed by an 'American' railway built in the 1850s. It thus was subject to enormous outward forces, mainly the U.S., that charted an early path towards modernisation but not towards full independence, even after nominal independence was achieved in 1903. The result was a contested sense of national identity that would emerge slowly, and leave a strong cleavage among the rich elite, ordinary citizens, and indigenous groups, which include the Cuna, Choco and Guaymi peoples (see Szok 2002). It must be remembered, however, that through 1821 Panama had thrown off Spanish control, and sought voluntary union with Gran Colombia, and would then break away with U.S. help in 1903 (Szok 2002).

Panamanians would come to resent exclusive U.S. control of the Canal Zone (an 8 km wide area on each side of the canal, established via the Hay-Brunau-Varilla Treaty), and likewise have mixed feelings over the U.S. invasion in 1989 to remove dictator Manuel Noriega, a former CIA intelligence informant involved in drug networks, to some degree created by U.S. policies of the 1980s (see timeline below). Through 1979-1999 the U.S. had 14 bases in Panama, hosting between 3,600-10,000 troops, both defending the Canal and representing a strong military presence in the region (Lemoine 1999). By 31st December 1999 (through the Carter-Torrijos treaties

18

signed in September 1977), Panama once again gained full control of the Canal, though treaties with the U.S. still insist that the Canal must remain under a neutral administration and must not be threatened by external control, otherwise the U.S. is allowed to 'unilaterally' intervene (Lemoine 1999). Indeed, through 2001 as the PRC normalised ties with Panama, and both PRC and Hong Kong investments flowed into Panama, there were some fears in the U.S. that this would give China too much influence on the region (Xinhua 2001a). Through March 2003, Panama was placed on 'yellow alert' in response to possible security threats in relation to the war in Iraq (Xinhua 2003a).

Furthermore, the possession of one of the world's most strategic waterways has not solved all economic problems: indeed, the small state has had to work very hard to upgrade railways, and has tried with some success to diversify away from agricultural products (bananas, sea food, sugar, coffee) and over-reliance on Canal revenues into manufacturing, international banking, tourism, communications and Internet services provision (BBC 2003a). Panama has also sought to open up trade flows by preparing to sign free trade agreements with the U.S., Taiwan and Singapore through 2003-2004 (UPI 2004a).

Panama: Canal Zone (Courtesy http://MondeDiplo.com/maps/panamadpl1999)

Lecture 12 19

Although the all Panamanian 'Panama Control Authority' has done well in managing the 13,000 ships that pass through its waters and the canal earned $1 billion dollars in revenues in 2004 (BBC 2005a), there is still a need to upgrade and or widen the canal (which cannot handle ships larger than the Panamax class, 294.1 meters in length and 32.1 meters wide, with 40% of cargo ships now larger than this) and its port facilities (Lemoine 1999; NotiCen 2001a). This would cost something in the order of $4 billion dollars (NotiCen 2001a), with later estimates running as high as $6-8 billion. Through December 2004: -

Panama's government is considering an $8 billion expansion of the 90- year-old Panama Canal to allow bigger ships to cross to and from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Possible upgrades include adding a third "lane" to make way for a new generation of mammoth, post-Panamax ships spanning 180-feet across that can haul twice as much as the current Panamax ships. Panamax is the term for the largest-sized ships that can now pass through the Panama Canal. The canal now has two "lanes"--one for ships moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the second for traffic in the opposite direction. (Carlson 2004)

Panama has tried to diversify its economy in a number of ways including boosting tourism, developing types of eco-, rainforest and marine tourism, plus maintaining a primary exports sector including bananas and hard wood timbres. Beyond this, it has a strong offshore finance system of banks (now subject to tighter tax-evasion and money laundering controls), plus 'manufacturing and a shipping registry generate jobs and tax revenues', while it also benefits from 'the Colon free trade zone, home to some 2,000 companies and the second largest in the world' (BBC 2006). In recent years it has also sought to become a hub of telecommunications and Internet servers within the Americas.

Moreover, Panama still suffers from ongoing environmental and social problems: problems in maintaining water levels crucial to keep the Canal operating, has been a trans-shipment location for drugs, has had problems with money laundering, with a total of 65 banks cooperating through late 2001 to reduce funds that might have been directed towards terrorist groups (Gonzalez 2001; reformed through late 2002), has had to deal with flows of illegal immigrants, has a poverty rate of approximately 37-40% (with 60% of indigenous groups such as the Ngobe-Bugle, the Kuna, and Embera living in poverty), and has not yet developed a national plan that adequately represents the desires of its indigenous and campesino population, many of whom are threatened by new dam and canal improvement projects (BBC 2003a; NotiCen 2001a; NotiCen 2001b). The government has promised to address these issues as well as investigate the human rights abuses of earlier regimes through a truth commission, but economic problems and corruption issues have continued to plague the government (BBC 2003a; BBC 2006). Likewise, Plan Puebla Panama (PPP), connecting southern Mexico through Central America onto Panama, though it aims to reduce regional poverty, to preserve the environment and to establish 'a hemispheric energy grid' has yet to accepted by indigenous groups, the poor and campesinos, leading to ongoing protests through 2004 in Guatemala and Mexico (NotiCen 2004a). However, through mid-2005 the Plan did get further government support regionally on the basis of increased energy prices and energy shortages: -

The region's energy ministers met . . . in Guatemala to confront spiking energy prices. Electricity and fuel costs have come to be regarded as threats to the stability

20

of regional governments as these costs are passed on to an increasingly resistant public.

Participants in the meeting represent the countries included in Plan Puebla-Panama (PPP), the megadevelopment scheme frequently attributed to Mexico's President Vicente Fox. The logic of PPP is to integrate the region in matters of energy, transportation, tourism, and other common concerns. Whether PPP projects could, or would, result in decreased consumer costs remains problematic, but the slow-moving plan could get a boost by linking to this growing issue. Popular resistance has been one reason for the PPP's lethargic pace.. . . Observers from Brazil and Colombia were present at the meeting, making it probable that those countries will be well-disposed to the proposals that involve them. The Brazilian delegation suggested and explained the use of biocombustibles. Colombia asked for formal inclusion in the PPP. That country has participated in PPP meetings for more than a year. The request will be taken up at the Cumbre de Tuxtla, as the presidents' meeting is called, in Honduras. Colombia will participate at the summit, along with member states Mexico, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize. (NotiCen 2005)

Timeline: Panama 1502-2003 (based on BBC 2003b; 2004; 2005a)

1502 - Spanish explorer Rodrigo de Bastidas visits Panama, which was home to Cuna, Choco, Guaymi and other indigenous peoples.1519 - Panama becomes Spanish Vice-royalty of New Andalucia1821 - Panama becomes independent of Spain, joins Gran Colombia. 1830 - Panama becomes part of Colombia following the collapse of Gran Colombia.1846 - Panama signs treaty with US allowing it to build a railway across the isthmus.1880s - France attempts to build a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, but fails due to financial difficulties and the deathmof more than 20,000 workers from tropical diseases.1903 - Panama splits from Colombia and becomes fully independent. US buys rights to build Panama Canal and is given control of the Canal Zone in perpetuity.1914 - Panama Canal opened.1939 - Panama ceases to be a US protectorate.1968-81 - General Omar Torrijos Herrera, the National Guard chief, overthrows the elected president and imposes a dictatorship.1977 - US agrees to transfer the canal to Panama as from 31 December 1999.1983 - Former intelligence chief and one-time US Central Intelligence Agency informant Manuel Noriega becomes head of the National Guard, builds up the size of the force, renamed the Panama Defence Forces, and greatly increases its power over Panama's political and economic life.1988 - US charges Noriega with drugs smuggling; Noriega declares state of emergency in the wake of a failed coup.1989 - Opposition wins parliamentary elections, but Noriega declares results invalid. Noriega declares "state of war" in the face of increased threats by Washington. US invades Panama, ousts Noriega and replaces him with Guillermo Endara.1991 - Parliament approves constitutional reforms, including abolition of standing army; privatisation begins.1992 - US court finds Noriega guilty of drug offences and sentences him to 40 years imprisonment, to bo served in a US prison.1998 - Referendum rejects constitutional amendment that would permit the president to run for a second term.1999 - Mireya Moscoso becomes Panama's first woman president.1999 December - Panama takes full control of the Panama Canal, ending nearly a century of American jurisdiction over one of the world's most strategic waterways. 2000 - Moscoso announces creation of a panel to investigate crimes committed while military governments were in power between 1968 and 1989.2002 January - President Moscoso sets up a commission to investigate corruption. The move follows large street protests against alleged graft in government circles.

Lecture 12 21

2002 April - Panama removed from list of uncooperative tax havens, drawn up by Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, after promising to make its tax system more transparent. 2003 September - National strike over management of social security fund paralyses public services. More than 40 hurt in clashes. 2004 May - Martin Torrijos, son of former dictator Omar Torrijos, wins presidential elections.2004 August/September - President Moscoso pardons four Cuban exiles Havana accuses of plotting to kill Cuban President Fidel Castro. Cuba severs diplomatic ties. Newly-inaugurated President Martin Torrijos pledges to repair relations; both countries agree in November to restore ties.2004 November - Panama Canal earns record revenues of $1 billion for the financial year.2005 May-June - Plans to increase pension contributions and raise the retirement age spark weeks of protests and strikes. President Torrijos had promised to reform the cash-strapped social security system.

We can see, then, that even a state such as Panama, with control of a key resource and a fair service sector, has found it difficult to generate a balance between different internal and external forces. The issue here is not so much a question of throwing off dependency, but rather shaping it into an interdependence whereby Latin America nations can begin to influence the terms of transnational activity in turn. Only in this way will Latin America be able to set and maintain their own national policies in the long term: -

This overview of the country studies can offer several basic clues for predicting trends and outcomes. One is that Latin America's future development will depend on how these countries respond to the rapidly changing outside world. The latter brings frequent shocks over which Latin America has no control, such as the price of oil or an Asian financial crisis. There are also the often erratic messages from Wall Street, the World Bank, or the U.S. government.

Second, the capacity of Latin American countries to respond to the world economic trends will depend upon their ability to set their own developmental priorities. The information revolution is a prime example. Will Latin America adapt to this revolution rapidly enough? If not, it will be quickly marginalized in world commerce. And the key to information technology, as for all productivity gain, is education. Yet Mexico and Brazil, Latin America's most populous nations, cling to elitist approaches to education which leave their populations more than 20 percent functionally illiterate. Will they have created the human capital need to compete in the new millennium? The question will be how much these countries choose to use foreign resources, such as foreign investment, and how much of their domestic resources they will decide to mobilise for the badly needed investment. (Skidmore & Smith 2001, p410)

As we have seen, new suggestions have been put forward for a more socially aware pattern of economic and political reform in Latin America. This will boost human resources, buffer vulnerable groups, and place a new emphasis on investments which have high social returns (Lora & Panizza 2002, p25). Likewise, varying patterns of regionalism have been viewed as a way of enhancing localised decision making while opening up to globalisation, as well as balancing different north and south agenda in the hemispheric system of politics (see lectures 2, 10, 11). This is going to be a slow process, needing decades of consistent effort. However, the 21st century may very well be the time when Latin America as whole passes into a more developed status that is modern, resilient, moderately prosperous, and culturally unique.

22

5. Bibliography and Resources

Resources: -A range of useful papers on economic and financial reform will be found at the Center for Economic Policy Analysis, at http://www.newschool.edu/cepa/papers/index.htmA range of topical articles on Latin America, politics will be found in Le Monde diplomatique (in English) at http://MondeDiplo.com/]. Approximately one-quarter can be read without charge.Most lectures from the Latin America in the International Relations 2006 subject will be soon come on-line in the International Relations Portal, via www.international-relations.comA range of data and research on indigenous languages of the Americas can be found through the homepage of the Indigenous Languages Institute, located at http://www.indigenous-language.org/Slightly dated but still useful annotated Reviews of Latin American Electronic Information, compiled and reviewed by Rhonda L. Neugebauer, will be found at http://home.earthlink.net/~rhondaneu/eresources/eresources1.htmlNew views on reform for Latin America will be found via the International Monetary Fund homepage at http://www.imf.org/external/index.htm

Further Reading: -

LOOK, Ann Marie "The Democracy/Media Link in Latin America", World and I, 19 no. 12, December 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database]

PANG, Eul-Soo " AFTA and MERCOSUR at the crossroads: security, managed trade, and globalization", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 25 no. 1, April 2003, pp154-181 [Access via Infotra Database]

SKIDMORE, Thomas E. & SMITH, Peter H. Modern Latin America, Oxford, OUP, 2000SMITH, W. Rand "Critical Debates: Privatization in Latin America - How Did It Work and

What Difference Did it Make", Latin American Politics & Society, 44 no. 4, Winter 2002, pp153-167 [Access via Ebsco Database]

TICKNER, Arlene B. & MASON, Ann C. "Mapping Transregional Security Structures in the Andean Region", Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 28 no.3, June-July 2003, pp359-391 [Access via Infotrac Database]

Bibliography

Agra Europe " Mercosur and Andean Pact strike new trade deal", April 8, 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database]

ANDRES, Oppenheimer "Seeking a 'New Path'", Hemisphere, 8 no. 2, Winter/Spring 1998 [Access via Ebsco Database]

ARANGO, Andres Pastrana "The Rio Group and the Millennium Summit", UN Chronicle, 37 no. 3, 2000, pp53-54

Australian "Chavez Returns to Rule in Caracas", 15 April 2002, p8BARTHÉLÉMY, Françoise "Ecuador's Pipeline Out of Debt", Le Monde Diplomatic, January 2003

[Internet Access]BBC "Panama Seeks Digitial Dividend", BBC News, 6 September 2001a [Internet Access]BBC “Bolivia Timeline”, BBC News, 20 December 2005 [Internet Access]BBC "Country Profile: Panama", BBC News, 2003, and 6 January 2006 [Internet Access]

Lecture 12 23

BBC "Timeline: Panama", BBC News, 14 December 2005a [Internet Access]BRAUDEL, Fernand Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century: Volume 3 - The Perspective of the

World, London, William Collins, 1986CALL, Wendy "Plan Puebla Panama", NACLA Report on the Americas, 35 Issue 5, Mar/Apr2002,

pp24-26CARACCIOLO-TREJO, E. (ed.) The Penguin Book of Latin American Verse, Harmondsworth,

Penguin, 1971CARLSON, Heather J. "Panama Leaders Considering Canal Upgrade: Waterway May Gain Third

"Lane", World and I, 19 no. 12, December 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database]CARRUTHERS, David "Environmental Politics in Chile: Legacies of Dictatorship and Democracy",

Third World Quarterly, 22 no. 3, June 2001, pp343-358 [Access via Ebsco Database]CHESNUT, R. Andrew " A preferential option for the spirit: The Catholic Charismatic Renewal in

Latin America's new religious economy", Latin American Politics and Society, 45 no. 1, Spring 2003, pp55-76 [Access via Infotrac Database]

COONEY, Paul "The Mexican Crisis and the Maquiladora Boom: A Paradox of Development or the Logic of Neoliberalism?", Latin American Perspectives, 28 no. 3, May 2001, pp55-83

COOPER, Andrew F. & LEGLER, Thomas "The OAS Democratic Solidarity Paradigm: Questions of Collective and National Leadership", Latin American Politics and Society, 43 no. 1, Spring 2001, pp103-126 [Access via BU Databases]

DE LA ROCHA, Mercedes Gonzáles "From the Resources of Poverty to the Poverty of Resources? The Erosion of a Survival Model", Latin American Perspectives, 28 no. 4, July 2001, pp72-100

Ecologist "Protesting Plan Puebla", 32 no. 10, December 2002, p8 [Access via Ebsco Database]Economist "Hard times, same old politics; Argentina's presidential election", March 22, 2003 [Access

via Infotrac Database]Economist "A Champion of Indigenous Rights - and of State Control of the Economy; Bolivia", 17

December 2005, p35 [Access via Infotrac Database]Economist "Enter the Man in the Stripey Jumper; Bolivia", 21 January 2006, p40 [Access via Infotrac

Database]ENGLER, Mark "Pay or Die", New Internationalist, Issue 353, , Jan/Feb2003 pp8-11 [Access via

Ebsco Database]FAURIOL, Georges A. Thinking Strategically About 2005: The United States and South America,

Washington, CSIS, 1999 [Executive Summary available via http://www.csis.org]FRASER, Barbara "Rich world, Poor World", National Catholic Report, 14 January 2000 [Internet

Access via www.findarticles.com]GEREFFI, Gary & HEMPEL, Lynn "Latin America in the Global Economy: Running Faster to Stay in

Place", NACLA Report on the Americas, Jan-Feb. 1996GONZALEZ, David "Changed Panama Banks Root Out Terror Funds", New York Times, 26 October

2001, pA8GORDON, Lincoln Brazil's Second Chance: En Route Toward the First World, Washington,

Brookings Institution Press, 2001GWYNNE, Robert N. & KAY, Cristobal (eds.) Latin America Transformed: Globlization and

Modernity, London, Arnold, 1999HANSEN-KUHN, Karen "Free Trade Area of the Americas", Foreign Policy, 6 no. 12, April 2001

[Internet Access via www.foreignpolicy-infocus.org/]KLAK, Thomas "Globalization, Neoliberalism and Economic Change in Central America and the

Caribbean", in GWYNNE, Robert N. & KAY, Cristobal (eds.) Latin America Transformed: Globlization and Modernity, London, Arnold, 1999, pp98-126

KLEPEIS, Peter & VANCE, Colin "Neoliberal Policy and Deforestation in Southeastern Mexico: An Assessment of the PROCAMPO Program", Economic Geography, 79 no. 3, July 2003. p221-240 [Access via Infotrac Database]

KUNHARDT, Jorge Basave "Accomplishments and Limits of the Mexican Export Project", ", Latin American Perspectives, 28 no. 3, May 2001, pp38-54

LARRAIN, Jorge "Modernity and Identity: Cultural Change in Latin America", in GWYNNE, Robert N. & KAY, Cristobal (eds.) Latin America Transformed: Globlization and Modernity, London, Arnold, 1999, pp181-202

LEMOINE, Maurice "In the Footsteps of Saint Karl", Le Monde diplomatique, May 1998 [Internet Access at http://www.en.monde-diplomatique.fre/1998/05/15lemoine]

LEMOINE, Maurice "Panama Gets Its Canal Back", Le Monde diplomatique, August 1999 [Internet Access]

24

LOOK, Ann Marie "The Democracy/Media Link in Latin America", World and I, 19 no. 12, December 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database]

LORA, Eduardo & PANIZZA, Ugo Structural Reforms in Latin America Under Scrutiny, Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department, Paper for the Reforming Reforms Seminar, Fortaleza, Brazil, 11 March 2002 [Internet Access via http://www.iadb.org/exr/topics/article_state_reform.htm]

LYNCH, Edward, A. "Catholic social thought in Latin America", Orbis, Winter 1998 [Internet Access via www.findarticles.com]

MONTES, Javier "Tackling Terrorism", Americas, 54 no. 2, March-April 2002, p52 NotiCen "Panama: Government Proposes US4billion Modernization Project to Enlarge The Canal",

Central American and Caribbean Affairs, 8 November 2001a [Access via Infotrac Database]NotiCen "Panama: Government Declares States of Emergency in Indian Zones", Central American and

Caribbean Affairs, 16 August 2001b [Access via Infotrac Database]NotiCen "Mexican President Vicente Fox Touts Plan Puebla Panama to Too Few Presidents, Too Many

Protesters", NotiCen: Central American & Caribbean Affairs, April 1, 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database]

NotiCen "Region's Ministers Met Under Plan Puebla-Panama Banner to Avert Crisis", NotiCen: Central American & Caribbean Affairs, 16 June 2005 [Access via Infotrac Database]

NUNAN, Fiona & SATTERTHWAITE, David "The Influence of Governance on the Provision of Urban Environmental Infrastructure and Services for Low-income Groups", International Planning Studies, 6 no. 4, 2001, pp409-426 [Access via Ebsco Database]

OCHOA, Enrique C. & WILSON, Tamar Diana "Introduction: Mexico in the 1990s", Latin American Perspectives, 28 no. 3, May 2001, pp3-10

PANG, Eul-Soo " AFTA and MERCOSUR at the crossroads: security, managed trade, and globalization", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 25 no. 1, April 2003, pp154-181 [Access via Infotra Database]

PETRAS, James " Latin America at the End of the Millennium", Monthly Review, July-August, 1999PION-BERLIN, David "Will Soldiers Follow? Economic Integration and Regional Security in the

Southern Cone", Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, 42 no. 1, Spring 2000, pp43-69

RAMONET, Ignacio "Viva Brazil!", Le Monde diplomatique, January 2003 [Internet Access]Reuters "Venezuela's Chavez Looks Set to Return in Triumph", 13 April 2002 [Internet Access]ROSENBERGER, Leif Roderick “Southeast Asia’s Currency Crisis: Diagnosis and Prescription”,

Contemporary Southeast Asia, 19 no. 3, December 1997, pp223-252SADER, Emir "Latin America: A Critical Year for the Left", Le Monde diplomatique, February 2003

[Internet Access via http://MondeDiplo.com/]SKIDMORE, Thomas E. & SMITH, Peter H. Modern Latin America, Oxford, OUP, 2000SMITH, W. Rand "Critical Debates: Privatization in Latin America - How Did It Work and What

Difference Did it Make", Latin American Politics & Society, 44 no. 4, Winter 2002, pp153-167 [Access via Ebsco Database]

SMITH, Chris “Bolivia Teeters under Populism”, Jane’s Intelligence Review, 1 November 2004STANLEY, Denise L. & BUNNAG, Sirima "A new look at the benefits of diversification: lessons

from Central America", Applied Economics, 33 no. 11, Sept 15, 2001 [Access via Infotrac Database]

STEVENSON, Jonathan Preventing Conflict: The Role of Bretton Woods Institutions, Adelphi Paper 336, London, IISS, 2000

SZOK, Peter "Beyond the Canal: Recent Scholarship on Panama", Latin America Research Review, 37 no .3, 2002, pp247-260 [Access via Ebsco Database]

TICKNER, Arlene B. & MASON, Ann C. "Mapping Transregional Security Structures in the Andean Region", Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 28 no.3, June-July 2003, pp359-391 [Access via Infotrac Database]

UPI "Panama on Aggressive Trade Agenda", United Press International, February 17, 2004a [Access via Infotrac Database]

WEINSTEIN, Michael A. "Testing the Currents of Multipolarity", Eurasia Insight, 16 December 2004 [Access via www.eurasianet.org]

World Development Report, Attacking Poverty: Opportunity, Empowerment and Security, 2000-2001Xinhua "Normalization of China-Panama Ties Benefits Both Peoples: Li Peng", Xinhua News Agency,

12 July 2001 [ Access via Infotrac Database]Xinhua "Panama Maintains Security Alert Over Iraq", Xinhua, 21 March 2003a [ Access via Infotrac

Database]

Lecture 12 25

Xinhua "Annan Calls for Support Against Poverty in Latin America", Xinhua News Agency, Nov 15, 2003b [Access via Infotrac Database]

26