French and Italian Sing Styles

-

Upload

marcelo-cazarotto-brombilla -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

1

Transcript of French and Italian Sing Styles

How the French Viewed the Differences between French and Italian Singing Styles of the18th CenturyAuthor(s): Elizabeth HehrSource: International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Jun.,1985), pp. 73-85Published by: Croatian Musicological SocietyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/836463 .Accessed: 31/05/2011 13:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=croat. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Croatian Musicological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toInternational Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music.

http://www.jstor.org

E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

HOW THE FRENCH VIEWED THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FRENCH AND ITALIAN SINGING STYLES OF THE 18TH CENTURY

ELIZABETH HEHR UDC: 781.7:7.034.7(=40/-50) Izvorni znanstveni clanak Original Scientific Pa,per

9 rue Villedo, 75001 PARIS, France Prispjelo: 8. prosinca 1984. Received: December 8, 1984 Prihvadeno: 7. sije/nja 1985. Accepted: January 7, 1985

With the professed influence of Italian musicians and composers in France, French theorists, musicians and informed amateurs felt compelled to defend their point of view concerning what they considered the proper, if not the more interesting, style of singing. Definitely the fmost contro- versial trends of the eighteenth century were found in France and in Italy. Though numerous turn-abouts in what was considered correct or fashion- able did take place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the culminating flamboyant vs. refined styles of performance existed for the better part of this latter century.

Much has been written about the 'Guerre des Bouffons'. Yet it is fascinating to read in the basic treatises on singing, music appreciation or even in the introductions to song books to what extent the French found it necessary to explain their preference for a more subtly embellished style. In general, most of these disputes center around ornamentation, whether written or free. Harpsichordists today have a definite advantage over most instrumentalists, and especially singers, because modern editions often include tables of the composers' own ornaments. Nevertheless, much has been explained about French vocal ornamentation on a surprisingly specific level. One only has to look in Jean Antoine Berard's L'Art du chant, dedicated to Mme de Pompadour, to find a description of the actual physi- cal movements of the vocal anatomy used to produce his published list of ornaments.1 As for the actual execution of the preferred embellishments, there is no lack of suggestions, even of specifically how many notes should be used; for example, in L'Ecuyer's Principes de l'art du chant:

i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135. i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135. i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135. i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135. i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135. i Jean Antoine BERARD, L'Art du chant, Paris, 1755, pp. 112-135.

73 73 73 73 73 73

74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 74 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85

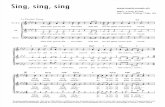

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

>La cadence parfaite a trois parties, sgavoir, sa preparation, son batte- ment & sa terminalson: sa preparation doit toujours se faire avec un martellement, ... quand la Note qui la precede est inf6rieure d'un ou plusieurs degres.

Jr' r 1F-- - FIK I r' martellement

On ne la place qu'a la fin d'une phrase. Remarquez que toutes les fois qu'il reste deux syllabes apres une ca- dence parfaite, il faut doubler la premiere de ces deux syllabes.<<2 >The perfect trill has three parts, that is, its preparation, its trilling and its ending. Its preparation must always start with a 'martellement' [pince], . .. when the preceding note is lower by one or more steps. It is only used at the end of a phrase. Note that every time that there follow two syllables after a perfect trill, it is necessary to double the first of these two syllables.<

In M. David's Methode nouvelle the idea of a very precise interpretation of the ornament is indicated by the author, although a fair amount of liberty is left up to the performer.

>>La Cadence prepar6e Iprend son appui du ton, ou du demi ton audes- sus du celle qu'on veut cadenoer, & sa preparation doit durer la moi- tie de la valeur de la Note cadencee, & marteller ensuite sur l'autre moitie de sa valeur, de mmee que si l'on vouloit exprimer plusieurs croches d'un degre a l'au,tre, du meme coup de gosier & sur le declin de la Cadence, de me&me que si l'on vouloit exprimer des doubles, & des triples croches, terminant la Cadence, ou les battements par un repos, ou soutien du ton de la Note cadencee.?3 *The prepared trill takes its support from the whole or the half step above the note to be trilled. Its preparation must take half the value of the note to be trilled and then trilled for the other half of its value, using several eighth notes from one degree to another, or a turn at the end of the trill, or even if one would like to use sixteenth and thirty- second notes, ending the trill or the beats by a rest or holding the note to be trilled.< Yet despite this surprising exactness, French vocal composers were in

no way consistent about whether or not their ornaments were included in their music; some expected the singer to have the necessary 'bon gout' to know where they would be appropriate. Not were they precise about how many varieties of these specific embellishments existed. Writers, like Be-

2 ,L'CUYER, Principes de l'art du chant, Paris, 1769, pp. 11-12. 3 Frangois DAVIID, Methode nouvelle ou Principes generaux pour apprendre fa-

cilement la musique, e 'at art echanter, Lyon, 1737, p. 133.

E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73--85 7

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

rard, even expressed amazement at this indeterminate number of 'agre'- mens' as stated in his aforementioned book: >*II est surprenant qu'on ne soit point avise jusqu'ici ide de'terminer le nombre des agre'mens, & d'en expliquer la nature.-<4 (>*It is surprising that up until now, one has not found it advisable to determine the -exact number of ornaments and their meanings..,x) For indeed, not only were there differ-ences in the r-ealization of a given -orn-ament, but also in its name.5 Monteclair, in his Principes complains that naturally this becomes most confusing for the student who although he learns from one mast-er, may be unable to interpret another. He then adds:

>>La musique e'tant la me'me pour les Voix comme pour les instrumens, on devroit s-e s-ervir des memes noms., et convenir unanimemt. des figu- res les plus propres 'a repre'senter les agre6mens du, chant..*.6 >>.As music is the same for voices as for instruments, one should use the same names for them and unanimously agree upon the proper signs to represent ornam*ents.-(<

He then proce-eds to list eighteen 'agre'mens' while Be'rard lists twelve; L'Ecuyer, six;7 L'Affillard, fourteen;8 and so on.

Most agreed, however, that these ornaments were only extra flourishes which shojuld not be added to the detriment of either the music or the text. Le Cerf in his Comparaison criticised the overabundant use of embellish- ments as inexcusable.9 Likewise, the reknowned author of the Encyclope6- die., Denis Diderot, voiced his opinion specifically in connection to opera singers under the heading 'Chant', by s-aying:

>>*Presque jamais les sons ne sont donne' ni avec Ila justesse, ni avec I'aisance, ni avec les iagre'mens dont uls sont susceptibles. On voit par- tout 1'effort; & toutes les fois que 1'effort se montre, l'agr6ment disp-a- roit.-<40 >*Almost never are notes in tune, nor produced with ease, nor with the ornaments suited to, them. Everywhere an effort 'is apparent; and every-time effort is'shown, pleasure disappears.-<<

Naturally, many olf the same remarks heard today also existed in the eighteenth century, such as that of bad p-ronunciation or the accompanist's

4 J. A. BPDRARD, op. cit., p. 112. ' L'TCUYER, Ordinaire cde L'Acad6mie Royale de Musique, views it more a-s a

problem of identical signs used for different interpretations (op. cit., p. 11). 6 Michel Pignolet de MONTECLAIR, Principes de musique, Paris, '1738, p. 78. 7L'UCUYER, op. cit., pp. 10~-18. 8 Michel L'AFFTTLLARD, Principes tr~s-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique,

Paris, 1717, pp. 2,5-.27. 9 Jean-Laurent LE CERF DE LA VIEVILLE SIEUR D)E FRESNEUSE, Compa-

raison de la musique italienne et de la musique frangoise, Bruxelles, 1706, tome IV, p. 127: '>Les ornamens ne sont point de l'essence ides Pie'ces, le -su-perflu devient ais&' ment incommode, & d'abord qu'il est incommode, il est inexcusable.x (>'Ornaments are not the essence of music. The isuperfluous easily becomes awkward; and as soon as it is awkward, it is inexcusable.()

10 Denis DIDEROT, Encyclop6die, ou Dictionnaire raisonne' des sciences, des arts et des m6tiers, par une societ6 de gens de lettres, Paris, 1761-1765, P. '145.

75 75 75 75 75 75

76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85 76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85 76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85 76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85 76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85 76 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1965), 1, 73-85

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

domination of the singer. Nevertheless, as L'Ecuyer reasons for most of these incomprehensible performances: '>cela vient encore plus de ce que l'on donne trop aux agrements & de ce que l'on sacrifie le sens a des Sons"<l (>>that mostly comes from making too much out of the ornaments and thereby sacrificing the meaning for sounds?).

Yet there is still another underlying thought which is very evident when composers or writers speak 'of the French style of singing and that is one of a desired sense of nobility12 or subtleness even to the point of restraint (mostly referred to as 'bon gofit', which for them was so necessary for a correct interpretation of their music). Monteclair expresses this quality in the following way:

>>La musique Latine perfectionne la Science, et la Musique Frangoise perfectione le gout. I1 ne suffit pas pour bien chanter le Frangois, de savoir bien la musique, ni d'avoir de la voix, il faut encore avoir du gouit, de l'ame, de la flexibilite dans la voix, et du discernement pour donner aux paroles l'expression qu'elles demandent, suivant les diffe- rents caracteres.<l3 >Latin music perfects science and French music perfects 'gout'. It does not suffice in order to sing French well, to know the music well, nor to have a good voice. It is still necessary to have 'gout', soul, vocal flexibility and insight in order to give the words their necessary expression according to their different meanings.<

Eighteen years earlier, Blainville, like so many others, explained his feelings about this essential point by first taking a poke at the contrasting Italian style when he wrote: >l'imagination sembleroit suffire pour compo- ser de la Musique Italienne: mais pour en composer de la Frangoise, il faut y joindre un gout exquiss.14 (>imagination would seem to suffice in order to compose Italian music; but in order to compose French, it is necessary to add to that an exquisite 'gout'?). Sieur Lambert was highly praised by Bourdelot and Bonnet in their Histoire when it was said that he [Lambert] well-illustrated the French manner of singing, even to the point of perfect- ing the art

t1 L']CUYER, op. cit., p. 7. 12 RAPARLIER, Principes de musique, des agr6ments du chant et un essai sur

la prononciation, I'articulation et la prosodie de la langue frangaise, Lille, 1772, p. 16: -Le Genre de l'Opera Francois ou de 1'Academie Royale de Musique doit etre noble, les Port-de-voix marques & isensibles, les Agr6ments du Chant detaches, les Paroles bien articulees en doublant les consonnes, & c.< !(>>The style of the 'Opera Francois' or of the Royal Academy of Music must be noble, the 'Port-de-voix' accented and sensitive, the vocal ornamentation detached, and the text well articulated by doubling the consonances, etc.<<) Raparlier is not the only author who also classifies the differ- ent idioms in individual sets of acceptable flourishes. He goes on to say: >>Le genre de l'Op6ra-Bouffon, doit etre vif & lger, dans lequel les Roulades, Passages, tours de Gosiers, sont les Agrements les plus usites.- (-The style of the 'Opera-Bouffon' must be lively and light, in which runs, passage notes and turns are the most common ornaments.c)

13 M. P. de MONTECLAIR, op. cit., p. 77. 14 Charles Henri de BLAINVILLE, L'Esprit de I'art musical ou Reflexions sur

la musique et ses differentes parties, Geneva, 1754, pp. 3-4.

E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85 E. HEHR, FRENCH VIEW OF 18TH-CENT. SINGING STYLES, IRASM 16 (1985), 1, 73-85

>soit pour la finesse & la delicatesse des ports de voix, des passages, des diminutions, des tremblemens, des tenues, des mouvemens et de tous les ornaments du chant qui peuvent flater le plus agreablement l'oreille, avec une m6thode admirable, & audessus de tout ce que les regles ordinaires de la Musique avoiet pu trouver jusqu'a ce tems-la en France.l15 >be it for the subtlety and delicacy of the 'port de voix', the passage

notes, the diminutions, the trills, the held notes, the 'movements' and all the vocal ornaments which can flatter the ear in the most agreable way, by an admirable method and furthering all the ordinary rules of music which had been found until that time in France<. As for the final ornamented version, a great deal of the responsibility

for portraying these expected qualifications seemed to lie with the composer. Le Cerf even feared that listeners would reject a composer if he abandoned this usual reservedness, lor if he used an overabundance of flourishes and thereby >si le soin de chatouiller leurs oreilles, le d6tourne d'aller a leur coeur.1<6 (>if the need to tickle their ears diverts it from going to their heart<<). Again, like Raparlier, he continues his argument by attesting that: >Dans la Musique des Opera, le badinage est fade & gro- tesque: dans celle d'Eglise, il l'est bien davantage, & il est outre cela impie et odieux.Al7 (>>In opera music, playfulness is pointless and grotesque. In that of the church, it is even more so, and furthermore it is impious and odious.<<) Just as so many others preferred, he would rather hear a less ornamented version, as long as it did not make the performance dry. In some cases, restraint, though, can be almost translated into more of a kind of tolerance, than an actual obligation tio add ornaments, and there- fore only added in order to make it more interesting for the singer.I8 This tendency for restraint also can be found in the Dictionnaire by the much disputed Jean Jacques Rousseau, under the heading

>- BRODERIES, DOUBLE, FLEURIS... La vocale Francoise est fort retenue sur les BRODERIES; . .. le Chant Frangois ayant pris un ton plus trainant & plus lamentable encore depuis quelques annees, ne les comporte plus. Les Italiens s'y donnent carriere: C'est chez eux a qui en fera davantage; 6mulation qui mene toujours a en faire trop.019 >-- EMBELLISHMENTS, DOUBLES, FLOURISHES... French vocal [music] is very reserved about EMBELLISHMENTS; ... French song,

15 Pierre BOURDELOT and Pierre BONNET, Histoire de la musique et des ses effets, depuis son origine jusqu'd present: & en quoi consiste sa beautY, Tome I, Amsterdam, 1715, p. 226.

16 J.-L. LE CERF, op. cit., p. 64. 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid., pp. 61-62: >Mais de meme qu'on lui pardonnera de s'y amuser & d'y

couler un petit ornament, pourvu que cela n'aille pas au badinage; on lui pardonnera, & plus aisement encore, de les negliger, pourvu que cela n'aille pas a la secheresse.<< (>But even if he will be forgiven for having fun and adding a little ornament [here and there] as long as it does not develop into further playfulness, still he will be pardonned more readily for neglecting them, as long as that does not become dry.<) 19 Jean-Jacques RIOUStSEAU, Dictionnaire de musique, Paris, 1768, pp. 59-60.

>soit pour la finesse & la delicatesse des ports de voix, des passages, des diminutions, des tremblemens, des tenues, des mouvemens et de tous les ornaments du chant qui peuvent flater le plus agreablement l'oreille, avec une m6thode admirable, & audessus de tout ce que les regles ordinaires de la Musique avoiet pu trouver jusqu'a ce tems-la en France.l15 >be it for the subtlety and delicacy of the 'port de voix', the passage

notes, the diminutions, the trills, the held notes, the 'movements' and all the vocal ornaments which can flatter the ear in the most agreable way, by an admirable method and furthering all the ordinary rules of music which had been found until that time in France<. As for the final ornamented version, a great deal of the responsibility

for portraying these expected qualifications seemed to lie with the composer. Le Cerf even feared that listeners would reject a composer if he abandoned this usual reservedness, lor if he used an overabundance of flourishes and thereby >si le soin de chatouiller leurs oreilles, le d6tourne d'aller a leur coeur.1<6 (>if the need to tickle their ears diverts it from going to their heart<<). Again, like Raparlier, he continues his argument by attesting that: >Dans la Musique des Opera, le badinage est fade & gro- tesque: dans celle d'Eglise, il l'est bien davantage, & il est outre cela impie et odieux.Al7 (>>In opera music, playfulness is pointless and grotesque. In that of the church, it is even more so, and furthermore it is impious and odious.<<) Just as so many others preferred, he would rather hear a less ornamented version, as long as it did not make the performance dry. In some cases, restraint, though, can be almost translated into more of a kind of tolerance, than an actual obligation tio add ornaments, and there- fore only added in order to make it more interesting for the singer.I8 This tendency for restraint also can be found in the Dictionnaire by the much disputed Jean Jacques Rousseau, under the heading

>- BRODERIES, DOUBLE, FLEURIS... La vocale Francoise est fort retenue sur les BRODERIES; . .. le Chant Frangois ayant pris un ton plus trainant & plus lamentable encore depuis quelques annees, ne les comporte plus. Les Italiens s'y donnent carriere: C'est chez eux a qui en fera davantage; 6mulation qui mene toujours a en faire trop.019 >-- EMBELLISHMENTS, DOUBLES, FLOURISHES... French vocal [music] is very reserved about EMBELLISHMENTS; ... French song,

15 Pierre BOURDELOT and Pierre BONNET, Histoire de la musique et des ses effets, depuis son origine jusqu'd present: & en quoi consiste sa beautY, Tome I, Amsterdam, 1715, p. 226.

16 J.-L. LE CERF, op. cit., p. 64. 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid., pp. 61-62: >Mais de meme qu'on lui pardonnera de s'y amuser & d'y

couler un petit ornament, pourvu que cela n'aille pas au badinage; on lui pardonnera, & plus aisement encore, de les negliger, pourvu que cela n'aille pas a la secheresse.<< (>But even if he will be forgiven for having fun and adding a little ornament [here and there] as long as it does not develop into further playfulness, still he will be pardonned more readily for neglecting them, as long as that does not become dry.<) 19 Jean-Jacques RIOUStSEAU, Dictionnaire de musique, Paris, 1768, pp. 59-60.

>soit pour la finesse & la delicatesse des ports de voix, des passages, des diminutions, des tremblemens, des tenues, des mouvemens et de tous les ornaments du chant qui peuvent flater le plus agreablement l'oreille, avec une m6thode admirable, & audessus de tout ce que les regles ordinaires de la Musique avoiet pu trouver jusqu'a ce tems-la en France.l15 >be it for the subtlety and delicacy of the 'port de voix', the passage