Freezing the fertility clock

-

Upload

virginia-hughes -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Freezing the fertility clock

40 | NewScientist | 14 April 2012

pla

inpi

ctu

re

a controversial technology could be the end of the biological clock, says Virginia Hughes

Frozen in time

120414_F_OvaryBank.indd 40 4/4/12 17:11:48

14 April 2012 | NewScientist | 41

The clock started ticking for T. Wilson* in 2008, when she turned 36. She had been divorced for seven years, and as a

trainee surgeon she barely had time to sleep, let alone date. But her waning fertility was not interested in reasons for putting off a pregnancy. Faced with the possibility that she might never be a mother, Wilson was afraid.

She wanted to preserve her fertility but didn’t like what technology had to offer. At that point, the preferred option for thousands of women all over the world was to freeze their eggs, but Wilson was daunted by the prospect of hormone injections, high cost and the time off work. Then she consulted Sherman Silber, a surgeon in St Louis, Missouri, who suggested she might like to bank one of her ovaries.

It is a highly experimental option. So far, it has been successful only for the very small number of women whose fertility has been destroyed by diseases such as cancer. But a growing number of clinics, including Silber’s, are beginning to offer it to healthy women who, like Wilson, are seeking a fertility insurance policy.

Extending the use of the technology to healthy women in this way is proving to be controversial because it is so untested, but it is a potentially attractive option. Because it promises a more reliable way to extend women’s fertile years, banking ovarian tissue could finally fulfil the early promise of the birth control pill: it will buy women ample time to decide when and indeed whether to choose parenthood. This, however, is only part of the appeal. More provocatively, the technology could usher in a fundamental revolution in the way women age.

To call the birth control pill revolutionary would almost be a cliché. Between 1970 and 2006, the average age of first-time mothers in the US rose from 21.4 to 25 years and the number of women who had their first child at 35 and beyond increased nearly eight times. The trend was reflected throughout Europe, Asia and most of the developed world (see graphic, p 43). Free to pursue higher education

and spend more time on their career before starting a family, the number of women in the workforce skyrocketed, particularly in professions previously dominated by men, such as science and medicine.

But for all these advances, birth control also introduced the oppressive notion of the ticking biological clock. In the 1990s, reproductive doctors began to talk of an infertility epidemic: today, an estimated 10 per cent of couples worldwide cannot conceive within a year.

Buying timeFor about a third of couples, the problem arises because of the natural decline of women’s fertility. A newborn girl has about 300,000 immature eggs, or oocytes, in each ovary. We used to think that this reserve represented all the eggs a woman would ever have. Although this dogma was overturned in February (see “The ovary bank”, p 42), egg reserves do unquestionably decline over time. This means that for the average woman, the chance of conceiving in a given month drops, between the ages of 25 and 40, by a factor of five.

In the 1970s, fertility treatments such as egg freezing emerged as a way to extend the upper limit of the childbearing years. But these came with caveats of their own. For Wilson, egg freezing would have required two weeks of hormone pills and injections, and frequent ultrasounds to monitor the ripening eggs – a regime that can cause mood swings and didn’t fit into her gruelling work schedule. And each of these expensive, time-consuming, hormone-heavy cycles would only yield around 12 eggs.

By contrast, if you bank ovarian tissue, you can theoretically preserve thousands of eggs after one short laparoscopic surgery.

Silber explained to Wilson that he would make three small incisions in her lower stomach. It would take him only about 15 minutes to remove most of her right ovary. Then, back in the lab, he would dissect its egg-rich outer layer into about a half a dozen >

Never too late to start?

*Name has been changed

120414_F_OvaryBank.indd 41 4/4/12 13:33:35

42 | NewScientist | 14 April 2012

tiny strips, soak them in antifreeze-like chemicals and preserve them inside a tank of liquid nitrogen (MHR, vol 18, p 57).

Once Wilson was ready to have a child, Silber would reimplant the thawed ovarian tissue on top of her remaining ovary. If all went well, within a few months, it would begin to generate relatively young eggs, making it possible for her to conceive naturally.

Wilson had the money for the surgery and freezing – about $7000 – so two months after her 37th birthday, she had the operation. With tissue in the freezer, Wilson says, “I’ve basically halted time”.

At least, that is the promise. The technology is only in its earliest days. Since 2004, only 19 babies have been born from frozen ovarian tissue, three of them to the same woman. All were born to mothers who had been left with no other option because of cancer (Annals of Medicine, vol 43, p 437).

It was to help these women that the technique was initially developed. Chemotherapy or radiation can destroy a woman’s reproductive organs. But if she is too young to menstruate, no eggs can be harvested for freezing. So instead of leaving girls infertile, researchers tried to figure out a way to save the entire egg-making apparatus.

Thanks to rapid advances in cryoscience and transplant medicine, it worked. The first baby was born in 2004 to a 32-year-old Belgian woman who had frozen her ovarian tissue before going through chemotherapy and radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Jacques Donnez, a surgeon at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCL), in Belgium, reimplanted the six-year-old tissue, and within the year, the woman conceived naturally (The Lancet, vol 364, p 1405). Ten more babies came from three clinics – Donnez’s, Silber’s and the fertility clinic at Copenhagen University

Hospital in Denmark, led by reproductive physiology professor Claus Andersen – and the rest from a smattering of clinics across Europe. Donnez and Andersen have each banked tissue from more than 500 women, and Silber from 68. Most of the ovarian tissue comes from young girls with cancer, who won’t need it for a decade or more.

That raises a serious problem. Because the experimental population has been so small, any conclusions have had to be extrapolated from a small number of babies. Donnez says the success rate for pregnancy at his clinic and Andersen’s is about 30 per cent, comparable with far more established procedures such as egg freezing and IVF. However, he cautions that this estimate is necessarily based on a relatively small number of attempts.

That lack of data is the main barrier to offering the technology to healthy women. For cancer survivors, ovarian freezing has often been their one chance of conceiving later, which puts failure in context. For

women who are able to conceive naturally, putting off pregnancy and relying on a transplant seems much more risky. Therefore, medical societies caution against elective ovary banking.

But for Wilson, the caveats were irrelevant. “What other option did I have?” she says. “Somebody has to be the first to step outside the norm.”

Any healthy woman who banks ovarian tissue is taking a gamble. First, the risks of surgery, including bruising and infection, are not minimal. A bad reaction to the anaesthetic left Wilson sore and vomiting for a week.

More importantly, however, it remains unclear how much ovarian tissue is damaged during freezing, and consequently how long the thawed ovary will continue to produce hormones and eggs. Andersen’s research shows that it could be as long as five years (Reproductive Biomedicine Online, in press).

But perhaps the biggest question is whether the eggs that led to pregnancy came from reanimated frozen tissue or ovaries that, despite all the odds, were still functioning.

That is the question Mary Zelinski, an associate scientist at the Oregon National Primate Research Center in Beaverton, is tackling with her colleagues in work with rhesus monkeys. These animals have similar menstrual cycles to women. Zelinski removes the monkeys’ ovaries, freezes the tissue, and then transplants it beneath the skin of the animal’s arm or abdomen. This way, she can be sure that any eggs come from the transplant, and not from ovaries that might still be functioning. Zelinski says that the results so far have been promising.

Beyond the mechanics, however, Zelinski worries about the lack of long-term data on

Reintroduction of ovarian tissue can kickstart hormone production

MED

ICA

L RF

.CO

M/S

CIEN

CE P

HO

TO L

IBR

ARY

THE OVARY BANK

How much do we really know about women’s fertility? A recent study threw that question into sharp relief.

It was thought that a girl is born with all of the eggs she will ever have. But in February, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston discovered a new kind of stem cell in ovaries taken from six women between the ages of 22 and

33. These cells produced eggs. The researchers don’t

know yet whether these eggs are capable of producing a child, and laws surrounding human embryo research may prevent them from answering that question for a long time. However, none of this has stopped widespread speculation about how the new findings might affect assisted reproductive

technologies. In the most common

procedure, doctors retrieve about a dozen mature eggs for fertilisation in the lab. If the stem-cell approach pans out, they could theoretically tap into an unlimited supply of eggs. If not, however, there is another way to increase the egg supply, and it involves freezing ovarian tissue (see main feature).

120414_F_OvaryBank.indd 42 4/4/12 17:20:41

14 April 2012 | NewScientist | 43

the health of the babies. Her fear is not unfounded. For instance, a 2010 study of 2.4 million births found that babies conceived via IVF are more likely to have childhood cancers. It is unclear whether the difference can be traced to the procedure itself, or whether it is a consequence of their parents’ infertility problems (Pediatrics, vol 126, p 270).

Because monkeys have shorter life cycles, Zelinski’s work could also shed light on this question. “I’d be more confident about it after I saw a monkey grow up to be a normal adult, and saw that monkey have its own normal child,” she says.

None of these caveats have kept fertility researchers all over the world from beating a path to the doors of the surgeons who have performed the procedures. Andersen gets so many requests that he has started scheduling workshops for six or eight visitors at once. He has taught at least 50 researchers so far, from countries including Jordan, Brazil, Singapore and the Netherlands. These visitors want to offer the technology to healthy women.

Silber, who has done elective procedures for seven women, including Wilson, isn’t surprised by their enthusiasm. “There’s no harm done in this procedure,” he says. In fact, ovarian tissue banking could have a benefit that goes far beyond delaying fertility. The technique offers the astonishing possibility of ending menopause as we know it.

Despite the controversy surrounding the reproductive potential of ovarian transplants, there is little doubt that the procedure restores hormone activity. This was clear from the first successful transplant of frozen ovarian tissue, undertaken to revive hormone production in a 29-year-old woman, who had been sent into early menopause by the removal of both ovaries. She found a doctor who would

reimplant tissue that she had banked, and with the help of hormone treatments, she began to menstruate (The New England Journal of Medicine, vol 342, p 1919). Like her, almost every woman who received the transplant produces her own hormones within six months.

This raises an intriguing possibility for women whose ovaries have stopped functioning because of their age. A transplant could be given when menopausal symptoms

begin, with more thawed strips of tissue added every few years if necessary. It would eliminate the mood swings, hot flushes and insomnia characteristic of menopause. More profoundly, prolonging natural hormone production for 10 or 20 years could delay or even prevent osteoporosis, the weakening of the bones that is commonly caused by a lack of oestrogen in older women. With banked ovarian tissue, a woman could delay menopause long into her 50s or even early 60s.

And yet, no one predicts a surge in older mothers beyond what is already possible with today’s assisted technologies. “Women are already putting off childbearing until their late 30s to mid-40s, when they realise they want children,” Silber says. “I don’t think this is going to make them hit that point any later.” Instead, he says, ovarian freezing will offer a better chance of success.

However, the age question might be moot. One of the most surprising possible outcomes of this technology is that more women, absolved from society’s pressure to “use it or lose it”, may choose not to have children at all. “It could allow women a heck of a lot more time to think: ‘Is this what I really want?’” says Beth Burkstrand-Reid, a law professor at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln who specialises in reproductive technologies.

There is little doubt that the procedure will soon spread beyond the world of cancer treatment. Even many sceptics say that if the technology were proven to be more reliable, and women were fully informed of its risks and benefits, their reservations would diminish. IVF was also initially greeted with scepticism, notes Nanette Elster of the Spence & Elster fertility law practice in Chicago. But after 4 million babies were successfully carried to term, the stigma of “test-tube babies” vanished. The same gradual acceptance is likely for ovarian tissue transplants, she says. “If it were further along, there would be less concern about doing this.”

For now, the task of pushing it further along will be left to early pioneers like Wilson. Four years after her surgery, she got married, and the couple has since tried every possible route to pregnancy. But in late January, her pregnancy test was negative. “It’s devastating,” she says.

If IVF fails, she plans to have the banked ovarian tissue re-implanted. “There is consolation in knowing that I’ve got some younger eggs out there,” Wilson says.

Meanwhile, the number of pregnancies from frozen ovarian tissue steadily grows: number 20, at Donnez’s clinic, is due this summer. n

Virginia Hughes is a journalist in New York City

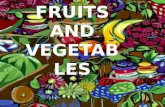

Stopping the clockAfter the introduction of the birth control pill in 1960, women in many countries started having children later in life.This dovetailed with greater female representation in higher education and the workforce

US

Age

FRANCE CANADA DENMARK NETHERLANDS JAPAN SWITZERLANDSWEDENITALYIRELANDBRITAIN30

20

10

0

1970 2006 1970 2006

21.425.0 23.0

27.0 24.427.8

23.728.0

23.828.4

25.328.7 28.7

25.028.8

24.829.0

25.6 25.329.429.2

25.9

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Council of Europe, Vienna Institute of Demography, Statistics Canada, and Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

AVERAGE AGE OF MOTHER AT FIRST BIRTH

”With banked ovarian tissue, women could put off menopause into their early 60s, thereby delaying or preventing osteoporosis”

120414_F_OvaryBank.indd 43 4/4/12 17:30:22