Franzosi. the Return of the Actor. Interaction Networks Among Social Actors During Periods of Higs...

-

Upload

miguel-gutierrez -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Franzosi. the Return of the Actor. Interaction Networks Among Social Actors During Periods of Higs...

131

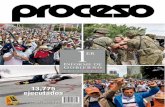

THE RETURN OF THE ACTOR. INTERACTION NETWORKS AMONG SOCIAL ACTORS DURING PERIODS OF HIGH MOBILIZATION (ITALY, 1919-1922) Roberto Franzosi† In a book titled Le retour de l'acteur (The Return of the Actor), French sociologist, Alain

Touraine, writes that "the object of sociology is to explain the behavior of actors by the social relations in which they are placed . . . . It is the relation, not the actor, that we must study." In this paper, I follow up on the prescriptions of that view of sociology's mission. I illustrate the empirical results of statistical analyses based on network models of event data for the years of high working-class mobilization (1919-20, the "red years") and Fascist counter-mobilization (1921-22, the "black years") in Italy. The data were collected from a newspaper on the basis of a "semantic grammar," the simple linguistic structure centered around subjects, actions, objects and their attributes. That structure, which has at its core Touraine's concern with social actors and relations, allows investigators to go "from words to numbers." The analysis of those numbers confirms the historians' view of that period, the dramatic shift in patterns of collective behavior from the "red years" to the "black years." The analyses also provide some preliminary evidence on the explanatory power of various social science theories of mobilization and of Fascism. More broadly, the paper explores some of the epistemological consequences of relying on story grammars and network models as tools for the collection and analysis of narrative data.

In a 1984 book titled Le retour de l'acteur (The Return of the Actor), French Sociologist Alain Touraine (1984: 107, 111; my translation) wrote: All inquiries that refuse an analysis of relations among social actors are

extraneous to sociology or even opposed to it. . . . The sociology of action is at the core of sociological analysis. . . the object of sociology is to explain the behavior of actors by the social relations in which they are placed . . . . It is the relation, not the actor, that we must study.

By no means was this the first proposal of a relational manifesto for sociology. Simmel, von Wiese, Park, Ross, Burgess had already done that many decades earlier. But in spite of this rich theoretical tradition, sociologists have been quite slow in following up on the prescriptions of a relational view of the sociological enterprise. For decades, variables and structures, rather than actors, have made up sociology's empirical and theoretical world. In this paper I show how new methodological tools, such as semantic grammars and network models, help to refocus ________________________________ * Data collection for this project was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation (grant SESB8511632). Data analysis has benefitted from another National Science Foundation grant (SBRB9411739). I am indebted to William Bainbridge and Andrea Kline for their help in transferring the NSF grant to Oxford. I would like to thank Desmond King, Ruud Koopmans, Dieter Rucht, and Charles Tilly for their insightful comments, and Pier Paolo Mudu and Mauro Giorgetti for their help with data analysis. assistance. † Roberto Franzosi is Professor of Sociology, University of Reading, Whiteknights, PO Box 218, Reading, RG6 6AA, Great Britain, email: [email protected] © Mobilization: An International Journal, 1999, 4(2): 131-149

Mobilization

132

sociologists' attention back on the actor. I used these tools to collect and analyze narrative data taken from some 15,000 newspaper articles on the 1919-22 period of Italian history, a period which "may well have produced the highest level of involvement in collective violence . . . in Italy's modern history" (Tilly, Tilly, and Tilly 1975: 126). In the span of just four years, Italy went from a revolutionary situation culminating in the vast factory occupation movement of September 1920 (the biennio rosso or "red years" of 1919-1920) to a reactionary period that ended with Mussolini's "March on Rome" and the Fascist takeover of power in October 1922 (the biennio nero or "black years" of 1921-1922). The empirical evidence strongly confirms the historians' view of the period, the dramatic (and to a large extent sudden) shift in the patterns of mobilization and counter-mobilization processes.1 Beyond the substantive-historical issues, the paper also tackles a number of epistemological issues. In a series of methodological articles, I have asserted that a linguistics approach to text coding based on semantic grammars has a number of advantages over more traditional approaches (e.g., Franzosi 1989, 1994). The statistical analyses presented here using "real" data, rather than toy examples, certainly support those assertions. But the analyses also highlight perhaps an even greater advantage of semantic grammars: the relational structure of a data collection grammar—one centered on actors, actions, and the attributes of both actors and actions—makes it possible to abandon the regression model as a tool of statistical analysis and to adopt network models. The shift in the use of statistical tools represents more than a change in strategies of data analysis. The methodological shift from "variables" to "networks" and "relations" entails a parallel epistemological shift from a conception of social reality as structures (namely measured by "variables") to one of social actors and their actions, "a . . . crucial watershed period in "American sociology" (Emirbayer and Goodwin 1994: 1417). STORY GRAMMARS AND NETWORK MODELS The traditional study of protest movements has focused its attention on the explanation of event counts (e.g., number of strikes, number of riots). The question of interest to social scientists was: Which factors explain the temporal (e.g., month-to-month, year-to-year) or geographic (e.g., city-to-city, state-to-state) variation in the number (or intensity) of protest events observed? To find an answer to that question, social scientists have typically used event counts as dependent variables in regression models with a set of independent variables (e.g. unemployment, prices) as explanatory factors. Even studies that focused on event characteristics (rather than event counts; e.g., type of events, type of actors) still attempted to relate those characteristics to recognizable properties of the context of protest.2 In recent years, however, social scientists working on processes of mobilization have begun to shift their attention away from the properties and characteristics of individual actors and toward the network of interactions among those actors (Emirbayer and Goodwin 1994). Thus Gould (1991), in his study of the insurgency of the Paris Commune of 1871, shows how the network of formal and informal social ties in Parisian neighborhoods provided the basis for solidarity among the insurgents. Padgett and Ansell (1993), using data on marital, economic, political, and personal ties among Florentine families of the first quarter of the 15th century, reconstructed the structure of social relations among Florentine families that eventually allowed Cosimo de' Medici to consolidate power. 1 Social scientists refer to the involvement of a large number of actors in protest movements as "mobilization" (or "primary mobilization") and as "counter mobilization" (or "secondary mobilization") to the reaction of other actors. 2 Tarrow's work (1989) provides a rich map of the properties of the mobilization process during the 1968-73 Italian cycle of protest (e.g., actors, demands, tactics) and attempts to link movement properties to political context.

Return of the Actor

133

The shift of focus in social scientists' interest from social structures to social interactions was partly made possible by the development of new tools of data analysis, network models, that operate on data that measure relationships among actors rather than properties of actors. In this paper I show how the development of another methodological tool—a tool of data collection rather than data analysis, "story grammars"—delivers data that are not only centered on event properties rather than event counts, but are also ideally suited to be analyzed with the use of network models. " A story grammar" is the linguistic structure <subject> <action> <object> and respective <modifiers> that characterizes simple narrative text (Franzosi 1989, 1998a, in press). The <modifiers> are attributes of either the subject, the action, or the object (e.g.,<type of actor>, <number of actors>, <organization of actor> for the subject and object; <time>, <space>, <type of action>, <outcome>, <instrument>, <demands> for the action). The advantage of an approach to content analysis based on story grammars is that coding scheme design is not dependent upon the investigator's theoretical or substantive interests but on the inherent linguistic properties of the text itself. In fact, a "story grammar" delivers skeleton narrative sentences (or <semantic triplets>). Typically, both the <Subject> and <Object> of a semantic triplet are social actors or agents, as in the skeleton sentence "employer dismisses two workers." The information in a story grammar is organized according to a relational format, with subjects related to their actions, actors and actions related to their modifiers, and subjects and objects (both social actors) related to one another via their actions. A story grammar is an ideal tool for the collection of event data from narrative sources (e.g. newspaper articles, police reports). It not only makes possible the journey "from words to numbers," i.e., to analyze narrative information with the help of statistics (Franzosi 1994, 1997a, 1997b, 1998b, in press). More to the point, the relational nature of the information collected via a story grammar allows researchers to address Touraine's fundamental concern with social relations. It is a story grammar of this kind that I have used to record information on all instances of protest or violence that occurred in Italy during the years 1919-22 as reported in every issue of Il Lavoro, a Socialist newspaper published in Genoa. THE HISTORICAL PROBLEM: BIENNIO ROSSO AND BIENNIO NERO There is no single graph that provides a clearer picture of the mobilization and counter-mobilization processes of the "red" and "black" years than that of figure 1, where the number of semantic triplets of both working-class and Fascist mobilizations are plotted on the same graph. The plots reveal that, no sooner had working-class mobilization died out, the Fascists started mounting their reaction. But within those two broad cycles of mobilization and counter-mobilization, the plots reveal peaks of activity, such as the cycles of June-July 1919 and September 1920 during the "red years" and the cycles of March-May 1921 and October 1922 during the "black years." The first cycle in mid 1919 saw the Italian working class involved in the struggle against caroviveri (cost of living) in a crescendo of mobilization that ended with the general strike of July 20-21, 1919. The peak of workers' mobilization in September 1920 represents "the watershed between the revolutionary and reactionary phases of the postwar crisis," or the factory occupation movement (Lyttleton 1973: 36).3 Official

3 On these three peaks of mobilization, see Maione (1975: 25-31, 91-178, 179-290); on the factory occupation movement, see Spriano (1964).

Mobilization

134

Figure 1. Workers' Mobilization and Fascists' Counter-mobilization 1919-1922 by Number of Triplets

strike data confirm that these were the highest levels of working-class protest since those data had been kept (1879). Other indicators attest to the rising tide of mobilization during the "red years." Membership in the Socialist Party (PSI) soared from 50,000 before the war to 200,000 in 1918; 156 deputies were elected in 1919 compared to 50 in 1913 (Tilly et al. 1975: 168; Chabod 1961: 45-6). At the November 1920 administrative elections the PSI won 2,162 communes out of 8,059, and 25 provinces out of 69 (compare this to 1913, when the Socialists controlled only 300 communes and 22 provinces). The reactionary phase started in earnest in the Fall of 1920, with two peaks, March-May 1921 and October 1922. The peak of October 1922 coincides with the "March on Rome" and the Fascist takeover of power. The first peak (March-May 1921) comes on the eve of the political elections of May 15, 1921. The coincidence is not accidental. The Fascists practically made their debut on the stage of history in October and November 1920, around the time of the administrative elections. According to Colarizi, Fascist violence and terrorism spread in Apulia "before and especially during the electoral campaign. . . . The elections are held in Apulia in a climate of unprecedented maddening illegality and savage violence" (Colarizi 1977: 105; my emphasis). According to De Felice (1965: 608; see also 1966: 30), "The electoral competition had a great influence [on the growth of Fascist violence]." In the span of one year, the number of local Fascist organizations jumped from 88 at the end of 1920 to 834 of the end of 1921, and members from 20,615 to 249,036. By March 21 1921, the Fascist organizations were 317 with 80,476 members. "During the month of April [1921]

Return of the Actor

135

the number of Fasci [fascist organizations] reached 417 with 98,399 members and soared by the end of May, i.e., right after the political elections, to 1,001 Fasci and 187,098 members." (De Felice 1965: 607) NETWORKS OF INTERACTIONS The basic picture of the "red years" and the "black years," as captured by the plots of figure 1, is clear enough. For all the bias of newspapers as sources of socio-historical data, the tempo of mobilization and counter-mobilization revealed by these plots is remarkably consistent with other available evidence. Further simple exploratory analyses of my event data based on "who does what and why" tell us a great deal about the 1919-22 period in Italy (Franzosi, 1997a). In this paper, however, I want to exploit more fully the relational characteristics of these data and to trace more systematically the interactions of social actors. I turn to network analysis for help. For the sake of simplicity, I will focus here on a handful of networks around the following spheres of action: communication, request, conflict, violence, and control. Each network graph measures the direction and intensity of the interaction between social actors. The direction of the relationship is indicated by the arrow in the line. A double-arrow line indicates a reciprocal relationship. The intensity of a relationship is indicated by the relative thickness of the line. Thus, a directed line (i.e., a line with an arrow at the end) from workers to employers in a network graph of conflict tells us that workers have been involved in actions of conflict against employers. The network graphs for the sphere of action of communication (figure 2) give a dramatic picture of the increasing isolation of the working class. Workers and unions are at the center of a complex network of interactions with the government and employers in 1919, but are disconnected from public discourse by 1921-1922.4 The network graphs for request (figure 3) similarly highlight the dwindling capacity of the working class to make claims on employers and the state. We go from the rich networks of 1919 and 1920, with unions and workers making a barrage of claims, to the empty picture of 1921 where no actors reach the minimum 5% threshold necessary to be graphed.5 That same story is basically told by the graphs centered around the sphere of action of conflict (figure 4), with a great deal of conflict in the economic arena during 1919 and 1920, and with the emergence of a distinct political arena of conflict during the "black years" (Fascists vs. Socialists and, especially, unions). In fact, the total amount of political conflict born out by the network graphs is grossly underestimated because most actions performed by the Fascists are classified under violence. Again, the revival of conflict in the economic arena hides the basic fact that the nature of conflict shifts from offensive to defensive in the four-year period. Furthermore, while in the early years the total number of actions of conflict that workers carry out against employers is roughly equal to that of employers against workers (as

4 The information contained in figure 2 must to be taken with a grain of salt. After all, my reliance on a Socialist newspaper is likely to distort the real amount of communication for actors other than workers and unions (e.g., Fascists, Communists). Nonetheless, the fact that the information contained in figure 2 as provided by a working-class paper points to an increasing isolation of the working class, that, in my opinion, can be taken as serious evidence of the increasing difficulties of the Italian working class. 5 Surprisingly, the graph of 1922 seems to point to a renewed capacity of the Italian working class to advance demands. What the picture does not show, however, is that, first, the sheer number of actions of request plummeted to a fourth of what they had been, and that, second, the nature of the demands changed from "offensive" to "defensive," from demands mostly centered in the market to demands centered in the political arena.

Return of the Actor

141

Typically, local landlords relied on outside Fascist organizations from the city to carry out punitive expeditions in the country side (e.g., Cardoza 1982: 317-20; Snowden 1986: 186-7; Kelikian 1986: 133). By mid-1921, these small, night-time excursions into the countryside took on the character of full-scale military-style operations involving thousands of Black Shirts and large cities (e.g., Salvemini 1928: 113-4; Snowden 1986: 80). War veterans, particularly army officers, and youth "grown up amidst the rumble of war and inclined to look at it as a fun game" made up the hit squads. It was such membership that gave the early Fascist movement the impression of youthfulness and vitality (Lyttleton 1977: 71-2; Snowden 1986:183-5; 1989: 157-60).7 It also gave the movement the know-how for violent, military-style operations to subdue political opponents where they were particularly strong (Salvemini 1928: 107; Chabod 1961: 70; Snowden 1989: 80; Linz 1976: 36-40). For this reason, Linz argued that Fascism may be viewed as a generational revolt, based on the emotional appeal to the idealists and the young (Linz 1976: 34-6). Just as the Fascists' tactics changed in the course of the "black years," so did the targets of their violence. According to Salvemini (1928: 110), the nascent Fascist movement started out by attacking, first, the economic strongholds of the working class, intimidating, beating, killing trade union leaders and individual workers, attacking and destroying their houses and their organizational headquarters. Within a few months, sometimes weeks, of systematic recourse to violence, village after village, entire provinces and regions would be "purged" (Del Carria 1975: 183). Then, the Fascists moved on to political leaders and political headquarters. "What matters to the agricultural landlords is smashing the proletarian economic organizations and organizations of resistance, even more than their political organizations" (Del Carria 1975: 183). The network graphs for control (figure 6) for 1919, 1920, and 1921 show the typical "star" shape that we already encountered in the network graphs of violence. The number of actors involved in the network for the year 1920 highlights the effervescent climate of the "red years," when the Left, protesters, strikers, unions, Socialists, workers, other people (bystanders, apolitical persons) all came under the stick of law enforcement agencies, particularly, the Left, workers, and strikers. The picture changes drastically in 1921, when economic actors (workers, strikers, unions) and other collective actors (participants in collective action and people) retreat from the stage of history to leave it to political actors, especially political extremists. By 1922, that picture becomes further polarized, with the police trying to keep both Communists and Fascists at bay. This last finding is somewhat surprising. Surprising, that is, in light of overwhelming evidence that the army, the police, and the carabinieri often supplied trucks, arms, and know how to the Fascists for their military-style "punitive expeditions." Much Fascist violence occurred with police compliance if not outright collusion.8 Salvemini reports a memorandum of October 20, 1920 that came from the General Staff and that encouraged divisional commanders "to show active favor to the Fascist organizations" (Salvemini 1928: 78). Tasca (1950: 187) reports the content of a late 1920 memorandum by the Minister of Justice Fera that "invites [the magistry] to stall the dossiers against Fascists' criminal acts." Truckloads of carabinieri would drive into towns behind the Fascists (Salvatorelli and Mira 1964: 179). Courts began to treat as "extortions" the boycotts and fines set by the workers' leagues against employers and strike breakers (Cardoza 1982: 356). I could continue with this exercise, faithfully describing the network graphs for each sphere of action, each new graph adding more or less detail to, shedding a dimmer or brighter 7 College students, city clerks, bailiffs of large estates, and, often, just plain criminals also joined in (Snowden 1986: 185; Cardoza 1982: 294). 8 De Felice (1966: 27-34); Corner (1975: 119-20); Kelikian (1986: 119-120, 142-3, 201-2); Cardoza (1982: 308-9, 354-5; 1989: 198); Colarizi (1977: 98-101, 108-9, 112-6).

Mobilization

142

light on basically the same picture of a drastic change in the number and type of actors involved and in the forms of their interactions from the "red" to the "black" years. We can safely leave those analyses without fear of compromising the picture. It is important, however, to make one final observation. The search for the actor seems to have slowly turned into a search for the action. To the extent that patterns of interaction seem to change according to specific spheres of action, the initial concern with actors and their characteristics has turned into a concern with actions and the patterned network of their relationships along specific spheres of action. The concept of inter-action among actors implies definite sets of relations among social actors (inter) on specific spheres of action. Indeed, as Touraine argues, the return of the actor implies a return of the action and of social relations. DISCUSSION Historians and social scientists have put forward a number of interpretations of Fascism (De Felice 1995). By and large, these different interpretations are based on the role that different social classes played in determining the final outcome and on the network of alliances and coalitions between these classes, as summarized below.

1. Fascism is the result of a class alliance between the landed elite, the industrial bourgeoisie, and the state (Barrington Moore 1966);

2. Fascism is the result of a class alliance between the industrial bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie (Poulantzas 1979);

3. Fascism is the political outcome of the reaction to Socialism by the petty bourgeoisie (Lipset 1981);

4. Fascism is the political outcome of the reaction to Socialism by the industrial bourgeoisie (Lenin, Third Communist International; see De Felice 1995: 63-69).

On whose side does the empirical evidence available in my database fall? Which of the theories of Fascism does it corroborate? Certainly, the timing of events seems to give face-value credence to Lenin's view: it was the urban industrial bourgeoisie who reacted against the industrial proletariat. Such a dramatic event as the factory occupation movement brought full page newspaper titles across the country. The first episodes of Fascist violence occurred immediately after that event in the Fall of 1920. While labor mobilization subsided, Fascist violence kept growing throughout 1921 and 1922, till Mussolini's "March on Rome" in October 1922 which marked the beginning of Fascism. And yet, this interpretation of Fascism as a reaction to Socialism leaves the role of many other actors in darkness. The problem, as De Felice (1995: 174) put it, is "reaction by whom and against whom?" Although Fascism was first born in the cities, and the factory occupation movement was largely an urban phenomenon, during the crucial "black years" Fascist violence struck mostly in the countryside. A number of historical studies of local situations provide compelling evidence on the reliance of rural Fascism on physical violence and its early spread, starting in the Fall of 1920. "Thanks to agrarian Fascism, the Fascist movement became a national reality in all respects," wrote De Felice (1966: 5-6; see also, Chabod 1961: 59; Del Carria 1975: 177-8; Corner 1975: x; Cardoza 1982). The urban bourgeoisie had been more reluctant (at least until the factory occupation) to embrace the Fascist ideology and its tactics. Despite the urban origin of Fascism (Lyttleton 1973: 51), Fascist inroads into the urban world of industry came late and slow. Kelikian shows that agrarian terrorism in the Brescian countryside started as early as the winter of

Return of the Actor

143

1920 with "punitive expeditions" by imported "black shirts" (Kelikian 1986: 133, 142-3, 151-3). But it is not until 1923 that Fascism started making incursions into Brescian industry (Kelikian 1986: 144, 176). According to Cardoza, the Bolognese bourgeoisie would express less support to the fascist organizations and other vigilante groups every time the liberal Giolitti government hinted at negotiating a settlement between workers' leagues and employers (Cardoza 1982: 300). In the industrial town of Sesto San Giovanni, one of Italian labor's traditional strongholds, the Fascists relied less on the use of violent tactics than on cultural forms (Bell 1986: 160). As late as April 1921, the Sesto fascist organizations apologized for a Milanese Fascist attack (Bell 1986: 162). The first raid against the Socialist Party headquarters did not occur until September 1922, a month before the March on Rome. Only on October 31, after the March on Rome, did Fascists from Sesto, Milan, and the Lomellina occupy the Sesto town hall (Bell 1986: 177-8).9 De Felice (1995: 268) provides the final absolution for the Italian bourgeoisie: "Despite the advantages that Fascism offered, the large industrialists never fully accepted Fascism, for psychological and cultural reasons, but also for a question of style and taste." Furthermore, the industrial bourgeoisie was leery of the Fascist state's inclination to interfere in economic matters and of Fascist military expansionism. Other evidence basically supports that picture. A quantitative study by Szymanski (1973), based on regional and provincial level data, found a strong positive correlation between the number of Socialist votes in the 1919 parliamentary elections and the number of acts of Fascist violence between January and June 1921, and a negative correlation between the number of acts of Fascist violence and the level of industrialization (as measured by the percentage of industrial workers). Szymanski took those results to mean that Fascism was an agricultural reaction to Socialism. Szymanski's emphasis on political elections helps us to shift the focus from such events as the factory occupation movement (which may lead to overemphasize the role of the industrial bourgeoisie and the proletariat) to other events, such as political elections (which point to the role of the landed elite and the peasantry). In this respect, the November 1920 administrative elections marked a fundamental shift in the rural balance of power with close to 27% of the communes and 36% of the provinces going to the Socialists (Snowden 1972: 274). The Socialist electoral victory came at a time when landlords had been forced by the agricultural leagues to sign a series of costly pacts which granted major concessions (in particular, imponibile di mano d'opera, the compulsory hiring of a specific number of men per hectare and per crop, and collocamento di classe, a roster of men to work the fields in turn). These pacts undermined landlord prerogatives, particularly their ability to keep wages down, and threatened the very basis of property relations, representing a genuinely revolutionary threat (Chabod 1961: 36; Snowden 1972: 274-5; Tilly et al. 1975: 176). In fact, Snowden writes: "It is no accident that in such crucial centers as Cremona, Bologna, and Ferrara the development of the Fascist squads began in earnest in the Autumn of 1920, after the local elections." (Snowden 1972: 275) Thus, if there was a reaction to Socialism, it did not involve the industrial bourgeoisie and proletariat, as claimed by Third Communist International; but rather drew upon support of the landed elite, the rural middle classes, and the landless peasantry. In fact, even the Italian Communists of the time moved away from the cruder view of "Fascism as a reaction to Socialism" to embrace a more nuanced view of the class struggle. The text of the message to the Italian workers approved on November 5, 1922 at the Fourth Congress of the Communist International reads: "The Fascists are, first and foremost, a weapon in the hands of the large land owners. The industrial and financial bourgeoisie follows with anxiety that 9 Perhaps, only in Tuscany the cities were a greater source of Fascist power than in most of Italy (Snowden 1989: 121-3). Heavy industry supported financially Florence Fascist organizations and newspapers, and many leading companies colluded with the Fascist unions (Snowden 1989: 133).

Mobilization

144

experiment of vicious reaction, and considers it as black Bolshevism" (cited in De Felice 1995: 69). Yet, even that picture of Fascism as a rural, rather than urban phenomenon, may be too crude. It assumes an agricultural social structure where an economically and politically backward landed elite faces a well-organized and radicalized landless peasantry. That picture is distorted. Different types of land tenure created a regionally varied social structure, rarely as polarized as the crude thesis of the reaction to Socialism implies: from capitalist agriculture in the Po Valley, to small tenants and sharecropping (mezzadria) in parts of the north and, especially in the center, and latifundia in the south (Snowden 1972: 276; 1986; Brustein 1991: 654-5). In the south, where latifundia prevailed, an organized Socialist threat never developed (with the exception of the Apulia region). There was never any need for Fascism, as the armed retainers of the landlords were sufficient to maintain order. Thus, southern Fascism only developed when it was already a mass movement elsewhere.10 In other regions, however, a middle peasantry of small tenants and sharecroppers stood in between the landed elite and a landless peasantry. And that middle peasantry had grown in size since the end of the war. Between 1918 and 1919, land redistribution schemes had passed into the hands of some half a million peasants an estimated one million hectares of land (Snowden 1972: 280-1). Many of these peasants had previously supported the Socialists while pressing their demands for land and for better conditions. But they gradually turned away from the Socialists when it became clear that Socialist plans for land collectivization threatened the interests of owning peasants. This conflict was sharpened by the Socialist Party's tactics of treating as class enemies all employers and owners, regardless of the amount of land owned (e.g., Snowden 1972: 277; Maier 1975: 310-2; Szymanski 1973: 401; Corner 1975: 102). Where Fascism could play on the differential interests of intermediate strata of the peasantry, like in the Po Valley, Fascism was particularly effective (e.g., for Ferrara see Corner 1975: 162-3). For Brustein (1991) it is this ability of Fascism to satisfy the material interests of social groups differently situated in the rural social structure that explains its success. In a quantitative study based on electoral results for the years 1919, 1920, and 1921, Brustein finds a substantial correlation between Socialist and Fascist voting: 0.655, 0.625 and 0.309 in 1919, 1920 and 1921 respectively. He takes the drop in the correlation in 1921, as well as the fact that the Fascists were the only major political newcomer that year, as evidence that the Fascists were the principal beneficiary in the decline of Socialist votes (Brustein 1991: 660-1). From these findings, Brustein draws the conclusion that, far from being merely a reaction to fear of Socialism, support for Fascism was the result of a proactive rational choice. If voters were switching directly from voting Socialist to voting Fascist, Brustein concludes that this must be a choice based on interests. The Fascist agricultural program better represented the interests of the middle and upwardly aspiring lower peasantry (Brustein 1991: 662). That may well be, but systematic resort to violence by the Fascists during the pre-electoral period (starting with the 1919 election) in many cases left voters in small peasant communities with little choice, regardless of the Fascist agricultural program; which, of course, does not make voters any less rational. The real prospect of being killed or victimized provides as much or more of an incentive as a promising electoral platform. Thus, the picture of Fascism as a reaction to Socialism, either by the industrial bourgeoisie in its struggle with the proletariat or by the landed elite in its struggle with the peasantry, is not entirely accurate. It does not properly account for the interests of the rural 10 It was also financially unsteady, and often absent from entire areas. Snowden argues that it was merely a parasitic transplanted product of Northern Fascism (Snowden 1972: 289-90). Furthermore, Southern Fascists soon became embroiled in factional struggles between local political cliques, and many landowners thus joined the strong Nationalist movement as a counterweight to Fascism (Lyttelton 1976: 134).

Return of the Actor

145

middle classes and the active role these middling classes played. The rural middle strata joined forces with the traditional urban petty bourgeoisie, who were dissatisfied and displaced in their traditional status by the war and industrialization. The social background of early Fascist party members betrays the strong petty bourgeois roots of Fascism (De Felice 1995: 264). Chabod (1961: 63-4) fully embraces the view of Fascism as "a complex phenomenon," the result of an alliance among the industrial bourgeoisie and the agricultural landlords—both hurt in their material interests—and the petty bourgeoisie, deeply shaken in their moral values. EPISTEMOLOGICAL REFLECTIONS Historian G.R. Elton writes that quantitative approaches to historical studies "operate only by suppressing the individual, by reducing its subject matter to a collectivity of human data in which the facts of humanity have real difficulty in surviving" (1983: 118-9). If the agents of history are nowhere to be seen in sociology's world, historical time is also often nowhere to be seen. Even as sympathetic a historian as Fernand Braudel wrote: "It is not history which sociologists, fundamentally and quite unconsciously, bear a grudge against, but historical time' (Braudel 1980: 49, 79; see also De Felice 1995: 113, 114). These critics have a point. Sociologists, and social scientists more generally, have indeed turned the subjects of history into statistical variables and structures. As for time, it is often just an excuse for statistical exercises, the dates in article titles being no more than the end points of a sample period for econometric models (1920-1930, 1860-1980, 1960-1975). Furthermore, popular tools of analysis of time series data (e.g., econometrics, ARIMA) provide a single coefficient for series characterized by different behavior at different frequency bands (e.g., long-term trend, cycles of a few year duration, seasonal cycles). The methodological tools described in this paper—story grammars and network models—go some way in overcoming these drawbacks, potentially leading to a rapprochement of the historian's and sociologist's worlds. After all, a concern with actors and actions, agents and agency, is at the core of both semantic grammars and network analysis.11 As for time, the narrative nature of the data delivered by semantic grammars foregrounds time as a major category of action (on time and narrative, see Franzosi 1998a, in press). Contrary to traditional modes of statistical analysis of time series data, network models can also be estimated over short sample periods, greatly reducing the risk of masking intra-sample temporal change.12 Yet, for all their power, these new tools for the collection and analysis of narrative data are not without problems. For one thing, given the high costs of collecting event properties rather than event counts from a potentially large number of narratives, the use of story grammars may force researchers to target only a handful of years for investigation.13

11 For network analysis, see Emirbayer and Goodwin (1994). Yet, language can be very effective in keeping even close worlds apart. Thus, in the network jargon, history's actors become nodes and actions become relations. Furthermore, there is a tendency among users of network analysis to focus on structural analysis which, like factor analysis, crunch networks of interaction across several spheres of action. 12 Thus, had I estimated the models over the entire four-year sample I would have missed the sudden turn of fortunes among social actors, the dividing line between mobilization and counter-mobilization—the "red years" and the "black years." The use of network models, however, does not necessarily result in a more historical conception of time. A concern with "structures" may lead network investigators to estimate their models over long stretches of time, no differently than econometric investigators and with no less harmful effects on their ability to detect points of historical break and change (e.g., see Padgett and Ansell 1993; Tilly 1997). 13 Thus, the sample period of this project is four years (1919-22), that of my other project on service sector vs. industrial sector conflict is two years (1986-87), that of Tarrow (1989) on the Italian postwar cycle of protest is eight

Mobilization

146

And the temptation, of course, would be to target years particularly rich in events; years where micro-events and actions14 ultimately sow the weft of a larger cloth, of a macro-event, such as my "red years" and "black years," or Tarrow's cycle of protest around the Italian "hot autumn" of 1969 (Tarrow 1989). It is those larger events that drive the overall narrative of the analyses. Second, the very richness of the data on a large set of concrete historical events may push investigators toward the traditional descriptive approach to issues of socio-historical explanation, back to the explanatory strategy of the histoire evenementielle based on the chronological narrative of the unfolding of events, on the role of actors and their actions (for a critique, see Braudel 1980). The application of new tools of data analysis such as network models does not necessarily improve things on this score. Laumann (1979: 394) wrote that "the hallmark of network analysis . . . is to explain, at least in part, the behavior of network elements (i.e., the nodes) and of the system as a whole by appeal to specific features of the interconnections among the elements." Such emphasis on explanation (rather than des-cription) is certainly part and parcel of our disciplinary mottos and of the legacy bequeathed to us by our "founding fathers" (Franzosi in press). But a focus on the system of interconnections alone is unlikely to lead us beyond the descriptive. Emirbayer and Goodwin observe, "The network approach investigates the constraining and enabling dimensions of patterned social relationships among social actors within a system" (1994: 1418). A full understanding of those constraining and enabling dimensions would require a full under-standing of the context. Without consideration of the interests of the actors involved, of their resources, of the cultural frames they use to interpret their (and others') actions, of the openings and opportunities that the social, economic, and political systems provide, "explanation" may not be forthcoming. Engrossed by our narratives, we can certainly provide a rich texture for the unfolding of the event (e.g., the "red years"), but the event itself we cannot explain. To explain the event we would have to consider it in the context of possibly other such events scattered in time (and space).15 And this means extending our attention beyond the single transformative event to longer temporal spans. It also means looking at a wider range of events beyond protest events. Thus the decline in working-class mobilization in 1921 and the rise of Fascist counter-mobilization cannot be understood without reference to the changing economic climate from the red years to the black years. By the end of 1920 the economic crisis was sweeping through European countries. Unemployment was growing rapidly every month with massive layoffs, as companies started reconverting to peace production, drastically altering class relations of power. And a proper explanation of an event may require not only a consideration of other than protest events (e.g., the passing of a bill, the inauguration of a new president, the sale of a company) and of longer temporal spans, but also of the cultural meaning that social actors attach to their actions (Franzosi in press). Story grammars, as data collection tools, work well only when applied to purely narrative clauses, clauses centered on actors and their actions. As such, they would be ill suited to capture the ideological meaning of evaluative clauses and texts. A focus on network properties should, by no means, come at the expense of a focus on the properties of the actors, their actions, and their environment. The two types of data and of data analysis should in no way be mutually exclusive. years (1966-73). 14 On the different types of event and the transition from micro-event or action to macro-event, see Franzosi (1998a, in press). 15 The "event" here refers to the macro-event (the "red years," the "hot autumn"), not the individual actions or micro-events; that is the real crux of the explanation.

Return of the Actor

147

CONCLUSIONS In this article I have illustrated the power of two new and different methodological tools for the collection and analysis of narrative data: story grammars and network models. The tools allow researchers to analyze narrative information quantitatively, or to go "from words to numbers." The empirical results of data collected from some 15,000 newspaper articles on the 1919-22 period in Italy, a period characterized by intense working-class mobilization during the "red years" (1919-20) and by violent Fascist reaction during the "black years" (1921-22), provide strong evidence on the power of these techniques. Semantic grammars deliver data that 1) are much richer that traditional event counts; 2) are very well suited for the application of such tools of data analysis as network models. Both semantic grammars and network models are fundamentally concerned with actors and their actions, with agents and agency. As such, these methodological tools should draw sociology closer to history, a discipline traditionally much more concerned with issues of agency. But these advantages hide potential drawbacks: 1) to focus scholarly attention on particularly transformative events, given the cost of data collection on longer historical periods; and 2) to resort to descriptive modes of explanation, the narrative of the evidence imposing its form on the mode of explanation. The questions are: Is the return of the actor inextricably linked to the return of the action and of the event? And does the return of the event necessarily imply a descriptive, rather than explanatory approach to solving puzzles of socio-historical nature? At the substantive level, the analyses of my data based on network models confirm the historical record of changing patterns of behavior. They clearly highlight the unfolding of the cycle of protest: from the early crisscrossing of mobilization of different groups, to the later counter-mobilization of threatened groups. The numbers have less to say about which specific theory of Fascism obtains, although they do highlight specific spheres of conflict (in the economic, social, and political arenas with specific sets of actors involved), specific points of tension in the social structure (from the obvious ones, such as workers and unions versus employers, to the less manifest ones, such as working-class women versus storekeepers). The identification of those points of tension and of those arenas of conflict does reveal that certain types of alliances among social actors may be more likely than others. And the numbers are just about silent about specific theories of mobilization, in particular, cultural framing. Story grammars are too crude a tool to capture the nuances of meaning of the ideologies embraced by mobilizing groups, the cultural framing involved in mobilization and counter-mobilization processes. For all that our data and methods reveal, much remains in darkness. There is no escape from a multiple-evidence and multiple-method approach to a study of history that would go beyond the simple game REFERENCES Bell, Donald H. 1986. Sesto San Giovanni: Workers. Culture and Politics in an Italian Town, 1880-1922.

New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. Braudel, Fernand. 1980. On History. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Brustein, William. 1991. "Red Menace and the Rise of Italian Fascism." American Sociological Review. 56:

652-664. Cardoza, Anthony L. 1982. Agrarian Elites and Italian Fascism: The Province of Bologna 1901-1926.

Princeton: Princeton University Press. Chabod, Federico. 1961. L'Italia contemporanea (1918-1948). Turin: Einaudi.

Mobilization

148

Colarizi, Simona. 1977. Dopoguerra e fascismo in Puglia (1919-1926). Bari: Laterza. Corner, Paul. 1975. Fascism in Ferrara 1915-1925. Oxford: Oxford University Press. De Felice, Renzo. 1965. Mussolini il rivoluzionario, 1883-1920. Turin: Einaudi. __________. 1966. Mussolini il Fascista. Vol. 1. La conquista del potere. 1921-1925. Turin: Einaudi. __________. 1995 [1969]. Le interpretazioni del Fascismo. Bari: Laterza. Del Carria, Renzo. 1975. Proletari senza rivoluzione. Storia delle classi subalterne italiane dal 1860 al

1950. Vol. III. Milan: Savelli. Elton, Geoffrey R. 1983. "Two Kinds of History." Pp. 71-121 in Which Road to the Past? Two Views of

History, Robert William Fogel and G. R. Elton, eds. New Haven: Yale University Press. Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Jeff Goodwin. 1994. "Network Analysis, Culture, and the Problem of Agency."

American Journal of Sociology. 99(6):1411-54. Franzosi, Roberto. 1987. "The Press as a Source of Socio-Historical Data: Issues in the Methodology of

Data Collection from Newspapers." Historical Methods. 20(1):5-16. __________. 1989. "From Words to Numbers: A Generalized and Linguistics-Based Coding Procedure for

Collecting Event-Data from Newspapers." Pp. 263-98, in Sociological Methodology, Clifford Clogg, ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

__________. 1994. "From Words to Numbers: A Set Theory Framework for the Collection, Organization, and Analysis of Narrative Data." Pp. 105-36, in Sociological Methodology, Peter Marsden, ed.. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

__________. 1997a. "Mobilization and Counter-Mobilization Processes: From the 'Red Years' (1919-20) to the 'Black Years' (1921-22) in Italy. A New Methodological Approach to the Study of Narrative Data." 26(2-3):275-304, Special issue of Theory and Society. Roberto Franzosi and John Mohr, eds. New Directions in Formalization and Historical Analysis.

__________. 1997b."Labor Unrest in the Italian Service Sector: An Application of Semantic Grammars." Pp. 131-145, Text Analysis for the Social Sciences: Methods for Drawing Statistical Inferences from Texts and Transcripts, Carl W. Roberts, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

__________. 1998a."Narrative Analysis B Why (And How) Sociologists Should Be Interested in Narrative." Pp. 517-54, in The Annual Review of Sociology, John Hagan, ed.. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews.

__________. 1998b. "Narrative as Data. Linguistic and Statistical Tools for the Quantitative Study of Historical Events." 43:9-32, Special issue of International Review of Social History, "New Methods in Historical Sociology/Social History" M. van der Linden and Larry Griffin, eds.

__________. In press. From Words to Numbers: Narrative as Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gould, Roger. 1991. "Multiple Networks and Mobilization in the Paris Commune, 1871." American Sociological Review. 56(6): 716-29.

Kelikian, Alice A. 1986. Town and Country Under Fascism: the Transformation of Brescia, 1915-1926. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laumann, Edward. 1979. "Network Analysis in Large Social Systems: Some Theoretical and Methodological Problems." Pp. 379-402 in Perspectives on Social Network Research, Paul W. Holland and Samuel Lenhardt, eds. New York: Academic Press.

Linz, Juan. 1976. "Some Notes Towards a Comparative Study of Fascism in Sociological Perspective." Pp. 3-121 in Fascism: A Reader's Guide: Analyses, Interpretations, Bibliography, Walter Laqueur, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1981 [1959]. Political Man. The Social Bases of Politics. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Lyttleton, Adrian. 1973. The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy. 1919-1929. NY: Charles Scriber. Lyttleton, Adrian. 1977. "Revolution and Counter-revolution in Italy, 1918-1922." Revolutionary Situations

in Europe, 1917-1922: Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary. C. Bertrand, ed. Montreal: Inter-university Centre for European Studies.

Return of the Actor

149

Maier, Charles S. 1975. Recasting Bourgeois Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Maione, G. 1975. Biennio Rosso. Autonomia e spontaneità operaia nel 1910-1920. Bologna: Il Mulino. Moore, Barrington. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy : Lord and Peasant in the Making

of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press. Padgett, John, and Christopher Ansell. 1993. "Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400-1434."

American Journal of Sociology. 98(6): 1259-1319. Poulantzas, Nicos. 1979 [1970]. Fascism and Dictatorship. London: Verso. Salvatorelli, Luigi, and Giovanni Mira. 1964. Storia d'Italia nel periodo fascista. Turin: Einaudi. Salvemini, Gaetano. 1928. The Fascist Dictatorship in Italy. London: Jonathan Cape. Snowden, Frank M. 1972. "The Origins of Agrarian Fascism in Italy." Achives Européenes de Sociologie.

13: 268-95. __________. Violence and the Great Estates in the South of Italy: Pulia, 1900-1922. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. __________. 1989. The Fascist Revolution in Tuscany. 1919-1922. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. Spriano, Paolo. 1964. L'occupazione delle fabbriche. Turin: Einaudi. Szymanski, Albert. 1973. "Fascism, Industrialism, and Socialism: The Case of Italy." Comparative Studies

in Society and History. 15: 395-404. Tarrow, Sidney. 1989. Democracy and Disorder. Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965-1975. Oxford:

Clarendon Press. Tasca, Angelo. 1950. Nascita e avvento del fascismo: l'Italia dal 1918 al 1922. Florence: La Nuova Italia. Tilly, Charles. 1989. "Collective Violence in European Perspective." In Violence in America. Volume 2:

Protest, Rebellion, Reform, Ted Robert Gurr, ed. Newbury Park: Sage. Tilly, Charles. 1997. "Parliamentarization of Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758-1834." 26(2-3):245-

73, Special issue of Theory and Society. Roberto Franzosi and John Mohr, eds. New Directions in Formalization and Historical Analysis.

Tilly, Charles, Louise Tilly, and Richard Tilly. 1975. The Rebellious Century 1830-1930. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Touraine, Alain. 1984. Le retour de l'acteur: essai de sociologie. Paris: Fayard.

![Indian Conjuring ([1922])](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/55cf99d8550346d0339f7848/indian-conjuring-1922.jpg)