Deputy General Counsel NCRH 20 / P.O. Box 1551 Raleigh, NC ...

Frank Ghery Tapestry Essay Final With Appendices 181111 1551

-

Upload

jongnam-shon -

Category

Documents

-

view

109 -

download

0

Transcript of Frank Ghery Tapestry Essay Final With Appendices 181111 1551

Tapestry and Architecture:

The Historical Context of the Eisenhower Memorial

Jonathan Warner

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission

August 10, 2011

Page 2

Introduction

Frank Gehry’s proposed design for the Eisenhower Memorial innovatively combines a

“tapestry,” woven of stainless steel, with an outdoor colonnade. There is nothing quite like it

anywhere in Washington or even the world. While this design may seem too experimental for a

presidential memorial, it is actually quite fitting for Eisenhower, a man of great depth and

complexity. Ike was the last president born in the 19th century, yet he was a modern man,

receptive to change and open to new ideas. He was a Kansan who left his home to serve his

country. He was a General who hated battle. Few men knew war better than he, and fewer did

more to prevent it. Gehry’s use of tapestry and architecture expresses the subtle nuances of

Eisenhower – the boy, the soldier, and the statesman. In fact, the history of tapestry, as well as

colonnaded spaces, reveals that Gehry’s design is uniquely appropriate for Ike.

Tapestry

The word tapestry comes to us from Ancient Greek, transmitted through Latin and then

French.1 In its most basic, technical definition, it involves the weaving of weft threads through

perpendicular warp threads in an “over-one, under-one sequence.”2 Separate weft threads of

different colors are woven independently of one another, starting and stopping periodically, to

form images. Often this is done using a “paint-by-number” method; different colors are assigned

to different parts of the figure, first drawn on the “cartoon,” which comes to life through

weaving.3

In its execution, Gehry’s design may not fit the exact technical definition of tapestry – its

images are not formed by multicolored wefts on perpendicular warps – but historically the word

has encompassed a broad range of subjects. For instance, the Bayeux Tapestry is no tapestry at

all but an embroidery, stitching done on a previously woven fabric.4 “Ressaut,” the wandering of

1 ταπης ταπητιον tapetium tapiz tapisser tapisserie tapissery tapestry; Francis Paul Thomson, Tapestry: Mirror of History (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc.), 11. 2 Harvey, Tapestry Weaving: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Loveland, Colorado: Interweave Press, 1991), 8; see appendix A, figure 1. 3 Ibid., 32-33. 4 John D. Anderson, “The Bayeux Tapestry: A 900-Year-Old Latin Cartoon,” The Classical Journal 81.3 (Feb. – Mar., 1986): 253.

Page 3

wefts from the perpendicular pattern, has defied the limits on tapestry from as early as the second

century A.D.5 More recently, the popular definition of tapestry has broadened, and new

questions have arisen about the limits of the craft.6 This year, one landscaper created several “6-

by-24-foot floral tapestry panels…using a plant-by-the numbers system.”7 This use of

landscaping has no direct connection to tapestry, except maybe in terms of function and the use

of color, yet it is dubbed “tapestry.” The definition of tapestry is so flexible that in the 19th

century it took on the meaning, still used, of “an intricate or complex combination of things or

sequence of events.”8 Rather than seek to preserve an orthodox definition of tapestry, the

Eisenhower Memorial’s designer considered the unique requirements of the memorial, as well as

historical precedent, and created an exceptionally appropriate design.

Timelessness

One chief concern for a presidential memorial is preservation. It must be built to endure

and to remain relevant for centuries. For this task, tapestry is appropriate; it has persisted as an

art-form for thousands of years, “especially closely bound up with the life of every time.”9

Weaving itself dates to prehistory. Some have postulated that early man, inspired by intertwined

weeds, fastened together grasses to fashion materials for use. One such woven basket found in

Egypt is over 7,000 years old.10 The earliest example of a woven textile was found in

Switzerland and dates to about 12,000 BC.11 The characteristics of tapestry production –

weaving perpendicular warp and weft threads of different colors to form images – are first seen

in Egyptian wall paintings and hieroglyphics from 3,000 BC.12 This sort of textile had obvious

advantages over animal skins and other types of cloth. It does not smell, when used as a

covering or wall hanging its density prevents draughts, and, depending on conditions, it can have

a longer lifespan than other forms of art, such as painting. In fact, the oldest surviving tapestry-

5 Thomson, Tapestry, 41. 6 Ibid., 9. 7 Dean Fosdick, “‘Living walls’ great backdrops for floral tapestry,” accessed August 3, 2011, http://www.timesunion.com/living/article/Living-walls-great-backdrops-for-floral-tapestry-1682116.php. 8 Oxford Dictionaries, “Tapestry,” accessed July 19, 2011, http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/tapestry?region=us. 9 Phyllis Ackerman, Tapestry: The Mirror of Civilization (New York: AMS Press, 1970), v. 10 Thomson, Tapestry, 27. 11 Ibid., 29. 12 Ibid., 25; see appendix A, figure 2.

Page 4

weavings were found in Egypt, in the tomb of Tuthmosis IV.13 These linen textile scraps, over

3,500 years old, are thought to have been used as ceremonial garments or as furniture

coverings.14 Greek vases and Roman wall paintings, as well as the remains of Coptic textiles,

show that tapestries continued to be produced in the Mediterranean through antiquity and into the

medieval period.

Besides material culture, classical literary sources provide ample evidence of the

significance of weaving to ancient culture and society. Weaving figures prominently in Homer’s

Odyssey; Penelope famously delays her work at the loom to thwart her vile suitors.15 In Greek

myth, Arachne competes with Athena in a weaving competition, only to be turned into a spider,

nature’s spinner of thread.16 Again, in Roman legend, Livy has Lucretia, a paragon of female

virtue, dutifully weave even as the other men and women gorge themselves with wine.17 In the

Judeo-Christian tradition, tapestries also are important. The original tabernacle was to be made

of costly textiles, and, according to the New Testament, this was “a copy and shadow of what is

in heaven.”18 In the temple, a linen veil partitioned the holy of holies, a cloth which is torn in the

Synoptic Gospels.19

As can be seen, weaving and tapestry has had a lasting effect upon western culture. For

thousands of years, tapestries have been used as a way to decorate, to depict scenes, and to tell

stories. This historic longevity is complemented by the excellent preservation of tapestry. In the

deserts of Egypt and Syria, as well as the arid coastal regions of Peru, dry climates have allowed

organic textiles to survive for thousands of years. The oldest extant tapestry, found in Thutmosis

IV’s tomb, still had bright blue and red hues upon discovery.20 Likewise, medieval and

Renaissance tapestries generally maintain much of their original vivid color. The Bayeux

Tapestry, one of the most famous examples of textile art, has survived for nearly one-thousand

years, almost having been used in 1792 as a wagon cover during the French Revolution!21

13 Rosalind M. Janssen, “The ‘Ceremonial Garments’ of Tuthmosis IV Reconsidered,” Studien zur Altagyptischen Kultur Bd. 19 (1992): 217, see appendix A, figure 3. 14 Ibid., 223. 15 Homer, Odyssey, 2.100-114. 16 Ovid, Metamorphoses, 6.5-54, 6.129-145. 17 Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 1.57. 18 Exodus 25:4, 35:6; Hebrews 8:5, NIV. 19 Matthew 27:51, Mark 15:38, Luke 23:45. 20 Janssen, “The ‘Garments’ of Tuthmosis IV,” 217. 21 Joan Edwards, foreword to Conquest and Overlord: The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry and the Overlord Embroidery, by Brian Jewell (New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1981), 9.

Page 5

Currently, Gehry Partners is planning for a lifespan of at least two-hundred years for the

stainless steel tapestry. This long-term vision for the memorial is appropriate considering

tapestry’s timelessness and remarkable survivability. An ancient art steeped in classical and

religious traditions is a fitting way to commemorate the deeds of a great American for future

generations.

Technology

One of the most exciting elements of the Eisenhower Memorial is the technological

challenges which the tapestry concept has overcome. Once no more than an idea, the stainless

steel woven tapestry is becoming more and more of a reality. Three different efforts, two in

America and one in Japan, assisted in discovering the best and most efficient way to produce a

tapestry that is durable, transparent, and artful. Historically, technology has always pushed the

boundaries of tapestry production forward. What began as a “low-warp” loom, consisting of

four stakes stuck in the ground to keep the warp threads taut, eventually became a complex

machine allowing for the speedy production of complex tapestries incorporating cotton, wool,

silk, metal, and other materials. The challenges confronted by the makers of the Eisenhower

Memorial’s tapestries are another chapter in the art-form’s story of technological innovation.

As trade and technology have evolved, the materials available to weavers have increased.

Early on, the simplest material available to weavers was flax, but soon other materials gained

prominence.22 In Egypt, the abundance of cotton encouraged the production of cotton

tapestries.23 In the orient, silk was available and proved to be a quite versatile substance,

providing a depth of color which cotton lacked.24 As cultures interacted and traded, a wider

variety of fibers were woven into tapestries, allowing for more richness of texture and vibrancy

of color. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, wool threads wrapped in precious metals began

to be woven into fabrics.25 Metal in tapestries is nothing new, but a tapestry woven entirely of

stainless steel has few predecessors. This feat will be a testament to modern technology and

innovation: an outdoor tapestry which is not a textile and a memorial which is a work of art. For 22 Thomson, Tapestry, 28; during the French Revolution, many such tapestries were burned in order to recover the gold and silver inside. 23 “American Tapestry,” The Decorator and Furnisher 20.2 (May, 1892): 55. 24 Ibid. 25 Harvey, Tapestry Weaving, 9.

Page 6

Eisenhower, a president who was no stranger to innovation, a stainless steel tapestry is

appropriate.

The looms on which tapestries are weaved have changed significantly over time. When

tapestry weaving first began over 5,000 years ago, it was done on a low-warp loom, parallel to

the ground and supported by a wooden stake at each of the four corners.26 “High-warp” looms,

looms perpendicular to the ground on which the weaver works top to bottom, developed soon

afterwards and initially used weights to keep the warp threads taut. These weights, attested on

Greek vases and later on in Norse mythology, allowed the weaver of the tapestry the freedom to

change the tension of the loom, a useful ability for executing various weaving techniques.27 In

antiquity, the crude low-warp loom was eventually phased out in favor of the high-warp loom.

The high-warp loom remained virtually unchanged until it was replaced with the “treadle-

operated low-warp loom.”28 It is unknown precisely when this change occurred, since between

the second and thirteenth centuries A.D. there are virtually no depictions of looms in art.29 In

this new loom, foot pedals raised and lowered the odd-numbered or even-numbered warp

threads, allowing the weaver to throw the shuttle with weft thread across the loom more easily.

This mechanical loom, the “direct precursor of the modern loom,” may have emerged as early as

the late third century A.D.30

The “treadle-operated low-warp loom” had obvious advantages over the high-warp loom.

It permitted the weaver to keep both hands free to move the shuttle, allowing for greater speed

and efficiency. In the nineteenth century, low-warp was 33 percent faster than high-warp.31 In

fact, the Gobelins workshops in Paris, one of the most famous producers of tapestries in Europe

from the seventeenth century onward, employed low-warp looms after Henry IV became

unhappy with the inefficiency of the high-warp loom.32 Even so, the high-warp loom had some

benefits. It tended to be wider than its low-warp counterpart, permitting more flexibility of

design.33 William Morris, a tapestry-maker of the late nineteenth century, critical of the

26 Thomson, Tapestry, 25; from an Egyptian wall painting. 27 Ibid., 25-26. 28 Diane Lee Carroll, “Dating the Foot-Powered Loom: the Coptic Evidence,” American Journal of Archaeology 89.1 (Jan., 1985): 168. 29 Ibid., 169. 30 Ibid., 173. 31 “The History of Tapestry,” The Art Amateur 2.10 (Oct., 1907): 34. 32 Thomson, Tapestry, 120. 33 Carroll, “Dating the Foot-Powered Loom,” 171.

Page 7

Gobelins workshop’s methods, insisted that “only the high-warp loom” was sufficiently versatile

and exposed to light for the production of tapestries.34

Among artisans, flexibility in adopting and adapting existing looms has continued to the

present day. During the industrial revolution, the flying shuttle (1733), the power loom (1784),

and the Jacquard loom (1805) changed the face of commercial textile production forever.35

Punch cards allowed weavers to automate repetitive patterns, and they inspired Charles Babbage

to conceptualize the “analytical engine,” a primitive computer. Today, with new technological

developments, computers permit ever more complex patterns and weavings. But as an art-form,

textile weaving remains the domain of the artisan. The current attempt to produce a massive

stainless steel tapestry for the Eisenhower Memorial must negotiate technological requirements

and the need for artistry.

Broad Appeal

Tapestry and, more generally, weaving has developed everywhere, not just in the West.

From Berlin to Beijing, from Cairo to Kentucky, woven objects and textiles are used functionally

and aesthetically. For this reason tapestry resonates at not merely a cultural level but at a more

human level. Since prehistory, people have crafted baskets, rugs, and wall hangings using

weaving techniques which are fundamentally the same as those used today. Doric columns and

triglyphs may be relevant in Greece and Rome, but tapestry focuses on a more basic and broad-

based human experience. Although significant to Western cultures, tapestry is not exclusive to

any one people but is the shared treasure of all mankind.

This is appropriate for President and General Eisenhower, a true internationalist and a

“citizen of the world.”36 He was the first president to travel by jet and the first to average four

foreign trips a year in office. He established programs aimed at protecting peace by building

international cooperation, and he made personal diplomacy a model for the presidency. This

outward-looking attitude makes tapestry a good choice for Eisenhower’s memorial, since its

history is international and not confined to any one culture.

34 Ibid., 158-159. 35 “Jacquard Loom,” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, accessed 26 Jul. 2011, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/299155/Jacquard-loom. 36 David Eisenhower, Eisenhower: At War, 1943-1945 (New York: Random House, 1986), 822.

Page 8

Many non-European cultures have created stunning tapestries. In East-Asia, for instance,

extremely fine silk tapestries began to be produced before A.D. 700.37 In contrast to their

European counterparts, the warp runs vertical with respect to the pattern. Contact with the

Middle East through the Silk Road may have influenced Chinese designs which often juxtaposed

heroic images with graceful landscapes filled with smaller figures.38 The Japanese adapted the

“k’o-ssu” tapestries of China to their own purposes. Instead of weaving entirely from silk,

Japanese weavers wrapped cotton wefts with silk to create rougher but more vibrant designs.

These oriental tapestries in turn influenced European weavers who, in accordance with

contemporary fashion, copied elements of Chinese and Japanese patterns, often at the expense of

the distinct historical and cultural significance of the original style. In Asia, these traditions

continue to remain relevant to the present and continue to influence the weaving of wall-

hangings and garments.

Our knowledge of Native American weaving is severely limited by the lack of written

sources. However, archaeological remains and current practices provide us with a basic

knowledge of weaving in the Americas. In the northern parts, a harsh environment meant that

there was little time for purely decorative textiles. Among the Aleuts, for instance, most

weaving was, and still is, functional, used as blankets or baskets.39 However, farther south,

textiles had more decorative and ceremonial functions. The Incans are probably most famous for

their woven designs, but their lack of a written language and the paucity of material culture make

dating such textiles difficult. Few examples of tapestry remain, but a plethora of other weaving

techniques – including embroidery, cross-stitch, and plain weave – has survived. Pre-Columbian

weaving technology was quite limited; it consisted of a “backstrap loom,” wooden needles, and

spindles with stone whorls. Despite primitive equipment and relative isolation – the Incans were

separated not only from the “Old World” but also, to a certain degree, from the Aztecs and

Mayans – textile production developed as a vibrant art and rivaled, or even surpassed, European

tapestry weaving in terms of complexity of technique and range of colors.40

37 Thomson, Tapestry, 44. 38 Ibid., 49; for an example, see appendix A, figure 4. 39 Ibid., 32. 40 Ibid., 37; for an example, see appendix A, figure 5.

Page 9

Egypt became an important producer of textiles during the Roman Empire, when the

Coptic Egyptians Christianized in the second or third centuries A.D.41 This had an interesting

effect upon Coptic textiles, which would often use Christian imagery to depict Pagan scenes or

figures.42 For instance, a tapestry commissioned by a Roman elite but crafted by a Christian

Copt, might feature a Pagan god with a halo. Later on, after the fall of the Roman Empire and

the rise of Islam, Coptic weavers continued to make tapestries. As non-Muslims they were

permitted to weave images of humans or animals without violating Islamic religious restrictions.

The history of weaving in Egypt and the Levant closely follows important religious changes, but

even as religious transformations took place, tapestry continued to be significant, underlying its

relevance to people of all backgrounds and cultures.43

In light of the broad based appeal of tapestries, the use of woven metal as an integral

element of the Eisenhower Memorial is appropriate. Eisenhower grew up in Abilene, Kansas, a

small town in the middle of America. The son of a mechanic, he grew to appreciate the value of

hard work and craftsmanship for a tightly knit local community. Once Eisenhower appeared on

the world stage, he emphasized the commonalities which bring people together. In the city of

London, in his first major public speech, Eisenhower remarked that when we consider important

values, “then the valley of the Thames draws closer to the farms of Kansas and the plains of

Texas.”44 Eisenhower’s actions, as general and president, show how earnestly he believed in

trying to forge bonds of friendship between nations. How appropriate, then, that he should be

memorialized with a tapestry, an art-form appealing to people of every creed and color, a craft

which calls to mind the ingenuity and thrift of hard-working Americans and people the world

over.

Tapestry as Communicator

The power of tapestry goes beyond aesthetic appeal. Far from purely decorative,

tapestries are used to tell stories and to inform. This makes the Eisenhower Memorial’s tapestry

much more meaningful, since it tells the story of Eisenhower’s small town roots and juxtaposes 41 Ibid., 39. 42 Ibid., 40. 43 For an example of Coptic tapestry, see figure 6. 44 The Eisenhower Memorial Commission, “Guildhall Address,” accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/pages.php?pid=91.

Page 10

those with the magnitude of his accomplishments in war and peace. The tapestry will not be a

high tech billboard that clutters the memorial area. Rather, it will, like other tapestries before it,

play an important role in telling a story and informing the viewer.

Narrative elements are central to the art-form of tapestry. During the Middle Ages and

Renaissance, historical, biblical, and mythological scenes were quite popular among weavers

who produced tapestries for ecclesiastical settings and increasingly for secular contexts.45

Scenes from Herodotus,46 Ovid,47 and other classical writers48 adorned the walls of castles and

the halls of estates as wealthy men attempted to tie the present to the pagan past,49 even as

beautiful tapestries with biblical and hagiographic scenes advertised their piety.50 The

coexistence of Christian and classical themes on tapestry during the Renaissance speaks to the

power of tapestries to communicate both religious and secular messages.

The narrative purpose of tapestries is underscored by the use of captions to denote

figures, describe scenes, and record ownership. The 3,500-year-old textile found in the tomb of

Tuthmosis IV was emblazoned with hieroglyphs meant to inform the viewer of the owner. Much

more than a “property of Tuthmosis” caption, the text tells the story of the Pharoah’s legitimacy

and power, describing him as “son of....., his beloved, lord of the crowns, who fights against a

multitude.”51 The mere fact that he could afford a costly textile is evidence of his wealth. Other

tapestries are also meant to convey specific messages. The Bayeux Tapestry is a running

narrative, which, assisted by Latin captions, tells the story of William’s 1066 invasion of

England. The message of the tapestry is clear and powerful because “the Latin…is simple; the

context visually exciting; the content historically significant.”52 A clear agenda is also at work in

the tapestry; it is meant to portray Harold as a treacherous king and William a justified

conqueror. On account of its clarity of message and narrative, the tapestry has been described by 45 “American Tapestry,” 55. 46 Life of Cyrus, King of Persia (16th c.) is still displayed in the home of the Marquess of Bath at Longleat House; Thomson, Tapestry, 74-75; see appendix A, figure 7. 47 Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1545) designed by Battista Dossi and completed by Hans Karcher, now hangs in the Louvre; ibid., 96. 48 Theagenes and Chariclea depicts scenes from the little-known Heliodorus’ Aethiopica and became quite popular in the 17th c.; ibid., 117; see appendix A, figure 8. 49 For instance, in the 15th c. tapestry, Hercules Initiating the Olympic Games, Hercules resembles Philip the Good of Burgundy, and a mounted figure beside him appears to be his son, Charles the Bold; ibid., 66; see appendix A, figure 9. 50 Consider Peter van Aelst’s Acts of the Apostles (1519), based on Raphael’s cartoons, and its considerable impact on 16th c. tapestry; ibid., 89-94; see appendix A, figure 10. 51 Janssen, “The ‘Garments’ of Tuthmosis IV,” 218. 52 Anderson, “The Bayeux Tapestry,” 257; see appendix A, figure 11.

Page 11

one scholar as “one of the most powerful pieces of visual propaganda ever produced.”53 In other

works, text supports the narrative elements. In a fifteenth century set of tapestries, War of Troy,

captions inform the viewer of characters, assisting the narrative process.54 Diomedes,

Agamemnon, and Achilles, decked in medieval armor, are indistinguishable from contemporary

warriors, so written aids help identify characters. Moreover, Greek text lets the viewer know that

the scene is from classical literature, even if the reader does not know the language.

In other instances, tapestries move beyond depicting simple scenes and narratives to

communicating more complex ideas. This can be done through the inclusion of a simple motto,

as was done in the Cordoba Armorial Tapestry: “nothing is done without himself.”55 Symbols

also have an important function in tapestry-art. Coats of arms, found in armorial tapestry, not

only denote ownership but also symbolize the power, values, and traditions of the family. In the

Cordoba Tapestry, crests of different families are included to celebrate the union of marriage. In

the Americas, symbolism was even more important. The Incans, lacking a written language,

may have used tapestry as a medium to record religious information.56 So powerful has textile

art been as a communicator that, in some cases, it was used as a replacement for language!

In light of the versatility of tapestry as a communicator, the Eisenhower Memorial’s

tapestry, integrated with text, will tell a story with clarity. The Commission wishes to inspire

visitors with Ike’s “leadership, integrity, life-long work ethic and self-improvement, and

especially his total devotion to the values and processes of democracy.”57 The interplay between

Eisenhower’s quotations, inscribed on stone, and the tapestry, mounted on columns, displays

Eisenhower’s values and accomplishments for all to see.

Tapestry as Celebrator

Tapestry is not only an established way to communicate ideas but also an effective

medium to commemorate great events and people of the past. This has often been done with a

53 Suzanne Lewis, The Rhetoric of Power in the Bayeux Tapestry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), xiii. 54 Thomson, Tapestry, 68-69; see appendix A, figure 12. Ackerman, Tapestry, 80-81; the set was hugely popular, and over a dozen pieces still survive. 55 Ibid., 106; “sine ipso factum est nihil,” translation my own; see appendix A, figure 13. 56 Ibid., 38. 57 The Eisenhower Memorial Commission, “Our Mission,” accessed August 3, 2011, http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/menu.php?mid=28.

Page 12

focus on martial subjects. In this regard, tapestry is a doubly effective way to honor Eisenhower.

The historical nexus between warfare and tapestry makes the art fitting for a military man just as

the display of a peaceful Abilene landscape reflects Eisenhower’s commitment to peace and

aversion to war.

Important events, particularly military scenes have often been displayed on tapestry. The

Bayeux Tapestry, the most famous example of this, records the momentous events of the

Norman conquest of England. Some of the most famous battles in world history are recorded on

tapestry. For instance, the tapestry series known as the Defeat of the Spanish Armada, was

commissioned to recount the English victory in 1588 and was hung in the Royal Wardrobe of the

Tower of London and later on in the Houses of Parliament.58 Contemporaries considered the

battle the greatest English victory since Agincourt; the event marked a decisive shift in naval

power from Spain to England. The Prestonpans Tapestry, currently the longest tapestry in the

world, was completed in 2010 to commemorate the 1745 battle and to impart the values of

“hope, ambition, and victory” to future generations.59 Another hugely important military event,

the June 6, 1944 invasion of Normandy, is recorded in textile art through the Overlord

Embroidery. Commissioned in 1968 by Lord Dulverton, this piece of art has a direct connection

to Eisenhower, both because he appears in three panels and because he himself organized and led

the force, the largest armada in history, which turned the tide of the war.60

Tapestry is also employed to honor great people, especially military leaders. In fifteenth

century France, tapestries glorified Caesar, Clovis, Charlemagne, and Roland, all of whom were

considered to have played a pivotal role in French military history.61 Julius Caesar’s life has

been the subject of several other tapestries,62 and William the Conqueror has the distinction of

58 These Tapestries were lost in a fire in 1834, but engravings survive; Thomson, Tapestry, 107; see appendix A, figure 14. 59 The Prestonpans Tapestry, accessed August 3, 2011, http://www.prestoungrange.org/tapestry/The_Tapestry.aspx; see appendix A, figure 15. 60 Lady Mark Fitzalan Howard, Foreword to Conquest and Overlord: The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry and the Overlord Embroidery, by Brian Jewell (New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1981), 52; Stephen Brooks and Eve Eckstein, Operation Overlord: The History of D-Day and the Overlord Embroidery (London: Danilo Printing Ltd., 1983), panels 9, 15, 28; see appendix A, figure 16 or Appendix C for more detailed information on the Overlord Embroidery. 61 Ackerman, Tapestry, 78-80. 62 The workshops in Milan produced several panels of Caesar in the 15th c., and at Mortlake, the Triumps of Julius Caesar (17th c.) were produced, modeling Mantegna’s painting; Thomson, Tapestry, 95, 111.

Page 13

being the key figure in the Bayeux Tapestry. Is it not fitting that Eisenhower should join the

only two other men to lead successful cross-channel attacks63 in being the subject of a tapestry?

But there is so much more to Eisenhower than his military career. He was a statesman

and a devoted public servant. As is fitting for Eisenhower’s life, the history of tapestry is not

tied solely to military subjects but has relevance in a wide range of contexts. Commoners often

show up in medieval and Renaissance tapestries,64 and religious subjects are perhaps more

frequent than martial.65 Currently, plans are moving forward to complete The Great Tapestry of

Scotland, a textile that will celebrate the accomplishments of the people of Scotland. The

makers of the tapestry, inspired by the recently created Prestonpans Tapestry, seek to use textile

art to narrate history and to honor the people of Scotland.66

Likewise, the Eisenhower memorial will celebrate the deeds of a great man who left a

legacy of peace and democracy for America. The centrality of the Abilene landscape in the

Eisenhower Memorial will highlight the fact that Eisenhower was a man of peace who hated war.

It also calls to mind Eisenhower’s identity as an American. There is a strong tradition of

landscape art in the United States, so the selection of a peaceful frontier scene, as opposed to a

battle narrative, is highly appropriate. The historic use of tapestry to celebrate significant

historic events and people makes tapestry an excellent choice for Eisenhower’s memorialization.

Architectural Elements

Another aspect of the Eisenhower memorial which deserves some consideration is the

architecture. The current design features ten unfluted columns, each one about 80 feet tall. The

columns support the tapestry and form a “U” shape, defining the memorial precinct. Overall, the

memorial will take up nearly four acres, a significant plot of land for downtown Washington, and

the project will revitalize a public space south of the National Mall and near the Capitol.

63 Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier and President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000), 144; see De Bello Gallico, 4.25-27 for Caesar’s account of the 54 B.C. amphibious landings. 64 For instance, the mid-15th c. work, Labors of the Months, features agricultural activity; Thomson, Tapestry, 60. 65 Ibid., 51; in the early middle ages, tapestries were limited to liturgical contexts, for the church was “the sanctuary, the place of refuge…for literature, artwork, and even money.” 66 David Robinson, “Author plans to tell story of Scotland with one of world’s biggest tapestries,” accessed August 4, 2011, http://news.scotsman.com/scotland/Author-plans-to-tell-story.6746688.jp.

Page 14

Memorials and Public Structures

A structure of this size will require a significant investment of time and resources.

Current estimates put the cost of the memorial at $120 million. At a time when budgets are tight

and fiscal restraint is needed, it is important to understand why we build memorials in the first

place. They are celebrations of human achievement, tangible representations of the legacy which

past Americans have left us. In Washington, we dedicate memorials to presidents,67 soldiers,68

and responsible citizens.69 Eisenhower fits into all of these categories; his memorial is entirely

consistent with past projects in Washington.

The tradition of celebrating human achievement through public buildings has a long

history. In antiquity, victorious generals would dedicate spoils in public temples and erect

trophies to celebrate victory. This “euergetism,” as it has been called, was as much an attempt at

self-promotion as it was a genuine act of munificence. Whatever the motives of such behavior, it

resulted in a host of magnificent structures adorning the ancient city. Paul Zanker describes

these as Volksbauten or “buildings for the people.”70 These could develop as loci for sharing and

expressing community identity. The construction of public buildings by private individuals

waned in late antiquity, but the notion that a community could celebrate its shared values at a

particular monument or memorial persisted.

Many of the same principles apply to the urban landscape of Washington. For instance,

the National Mall has developed a special place in the national psyche. Once every four years,

the country’s eyes turn towards the Capitol to witness the inauguration of a president, and

periodically, the people of America look to the other end of the Mall to behold demonstrations

and speeches at the Lincoln Memorial. Every spring, when the cherry blossoms around the Tidal

Basin bloom, the area around the Jefferson Memorial comes alive with visitors. One of the

beautiful things about the city of Washington is that its monuments and memorials have become

integrated into the fabric and life of the city. The Eisenhower Memorial, adjacent to the Mall

and just blocks from the Capitol, will certainly develop its unique role in the cityscape, it will 67 Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Teddy Roosevelt Island, FDR Memorial, the Kennedy Center. 68 World War II Memorial, Korean War Memorial, Vietnam War Memorial, African American Civil War Memorial, District of Columbia World War I Memorial. 69 George Mason Memorial, Martin Luther King Memorial, Boy Scouts Memorial, etc. 70 Carlos F. Norena, “Medium and Message in Vespasian’s Templum Pacis,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 48 (2003): 27.

Page 15

mark the farthest West that America is nationally celebrating a president, bringing the heartland

to the Capitol.

Columns, Outdoor Spaces, and Art

Much ink has been spilled discussing, debating, and criticizing the design of the

Eisenhower Memorial. One group, the National Civic Art Society, has gone so far as to launch a

design counterproposal competition.71 Apparently, the Eisenhower Memorial does not live up to

the classical ideals of ancient Greece and Rome. This could not be further from the truth. Using

columns to create outdoor spaces for enjoying art is a Greek and Roman tradition. The design

for the Eisenhower Memorial, while certainly modern, does not substantially deviate from past

methods of framing public space.

Although columns and pillars have been used in many societies to support structures in a

“post and lintel” manner, the Greeks and Romans were among the first to use columns for purely

aesthetic reasons. From an early date, colonnaded spaces were associated with commemorative

artwork. For instance, the Stoa Poikile, the “Painted Stoa,” had paintings fronted by 2 rows of

columns.72 The stoa, situated in the Athenian Agora, was completed by 460 B.C. during the

Pentacontaetia, a period of great properity for Athens.73 One of its four paintings celebrated the

recent victory over the Persians at Marathon and is thought to have served as a source for the

historian Herodotus.74 As “a well known and prominent building” over 44 meters in length, the

Stoa Poikile had an important role in the life of Athens.75 The covered pavilion became a place

for philosophical discussions and was the birthplace of Stoicism. The topographical connection

to nearby statues and structures strengthened this monument’s significance. Aeschines writes,

“pass on in imagination to the Stoa Poikile; for the memorials of all our noble deeds stand

dedicated in the Agora.”76 The ancient Athenians thought a colonnade coupled with painted

71 National Civic Art Society, “Eisenhower Memorial Competition: 2011,” accessed August 4, 2011, http://www.civicart.org/eisenhower.html. 72 John McKesson Camp, “Excavations in the Athenian Agora,” The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 76.4 (Oct.-Dec., 2007): 647; see appendix A, figure 17. 73 E. D. Francis and Michael Vickers, “The Oenoe Painting in the Stoa Poikile, and Herodotus’ Account of Marathon,” The Annual of the British School at Athens 80 (1985): 100. 74 Ibid., 109. 75 Camp, “Excavations in the Athenian Agora,” 650. 76 Aeschines, 3.186, translated by Charles Darwin Adams (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1919), accessed August 8, 2011,

Page 16

images was a fitting memorial for those who gave their lives in the service of the community.

To this day, “the simple pavilion…is the time-honored, respected form of memorial.”77 The

recently completed Prestonpans Tapestry is intended to be displayed in the “Prestonpans

Pavillion,” a circular portico which, much like the Stoa Poikile, protects the artwork from the

elements but uses columns to open up an outdoor space.78

The connection between outdoor colonnades and public art is also evident in the Roman

period. Imperial fora were often associated with the display of art. The Forum of Augustus,

dedicated in 2 B.C., was surrounded by colonnaded porticoes which housed statues of the summi

viri, famous men from Rome’s past.79 At the center of the plaza was a statue of Augustus. The

Templum Pacis, the Temple of Peace, completed by Vespasian in 75 A.D., consisted of a large

colonnaded square with a series of buildings coming off of the south-eastern end.80 The central

square contained a garden area with flower beds or water features. Greek works of art and spoils

taken from Jerusalem adorned the inside of the portico, making the complex a sort of “open-air

museum,” a public space where Romans could engage with art and architecture.81 Emperor

Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli has other fine examples of the synthesis of colonnades and artwork.

Hadrian chose to model many of the buildings after famous structures in the Greek world, so he

made his own Stoa Poikile.82 He also constructed a “Canopus,” a reflecting pool which imitated

a waterway in Egypt.83 Columns surrounding the water were topped by alternating arched and

flat stones. These columns served no functional purpose and were solely meant to define the

edge of the pool and to frame a number of Greek and Egyptian statues. In Classical Greece, the

Hellenistic World, and the Roman Empire, columns were used to create outdoor spaces to view

and enjoy artwork.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0002%3Aspeech%3D3%3Asection%3D186. 77 Thomas H. Creighton, The Architecture of Monuments: The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial Competition (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1962), 106. 78 Baron Courts of Prestoungrange & Dolphinstoun, “Displaying the Prestonpans Tapestry – in Prestonpans,” accessed August 9, 2011, http://www.globalartsandtourism.net/prestoungrange/html/news/show_news.asp?newsid=2992; see appendix A, figure 18. 79 Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Augustan Rome, (Bristol Classical Press: London, 2000), 56. 80 Norena, “Medium and Message in Vespasian’s Templum Pacis,” 26; see appendix A, figure 19. 81 Ibid., 27. 82 Charles W. Moore, “Hadrian’s Villa,” Perspecta 6 (1960): 24. 83 Ibid., 26; see appendix A, figure 20.

Page 17

In a similar manner, the Eisenhower Memorial will synthesize columns with artwork, in

this case a tapestry. The columns will be both functional – they hold up the tapestry – and

aesthetic – their sheer scale is appropriate for a man of Eisenhower’s achievements and status.

Together, the tapestry and columns define the memorial precinct. Surely columns are fitting for

a presidential memorial in Washington; they are central to the Jefferson Memorial, the Lincoln

Memorial, and nearly all government buildings in the city.

One should not be concerned that the columns, unfluted and void of capitals, depart from

classical paradigms. Similar, truncated columns were originally designed for the World War II

memorial before being replaced by pillars.84 In fact, a brief survey of classical architecture will

reveal just how much flexibility there is in the use of columns. In ancient buildings, we find both

fluted and unfluted columns, varying degrees of entasis, different materials and methods of

construction, and five categories of capitals – Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite –

each one differing in style depending upon the period. Hadrian was innovative, even eccentric,

when he made his “Canopus” using forms unattested in Greek, Roman, or Egyptian

architecture.85 In the American neo-classical tradition, we can see experimentation with different

sorts of columns at an early date. Benjamin Latrobe, appointed Surveyor of Public Buildings by

President Jefferson, designed corn and tobacco capitals – acanthus was the orthodox choice – for

part of the U.S. Capitol Building.86 These capitals’ incorporation of native vegetation celebrates

our independence and unique identity. Likewise, the clean, simple, and colossal limestone

columns of the Eisenhower Memorial will call to mind a man of unswerving integrity and

principle.

Synthesis of Tapestry and Architecture

Historically, economic and practical considerations have limited the audience of

tapestries. The fine threads and artisanship required to produce tapestry made it prohibitively

expensive for everyone but the most privileged of individuals. Moreover, the massive size of

tapestries means that few can display them. Consequently, only churches, castles, and private

84 Thomas B. Grooms, World War II Memorial: Washington, DC (Washington: U.S. General Services Administration: 2004), 68. 85 Moore, “Hadrian’s Villa,” 26. 86 Joseph Downs, “The Capitol,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1.5 (Jan., 1943): 172; see appendix A, figure 21.

Page 18

estates could afford large tapestries until recently. The emergence of art museums has allowed a

greater number of people to view famous tapestries. In Washington, the Smithsonian,

Dumbarton Oaks and the Textile Museum have collections of textile art from all over the world.

Nevertheless, the material limits on tapestries continue to restrict viewing audiences. For

obvious reasons, textiles cannot be kept outdoors. Even when stored inside, they must be stored

in special environments to stay in good condition. Their large size also makes it difficult for

some museums to display them. The genius of Gehry’s memorial design is that it overcomes the

traditional limits on tapestry. By using stainless steel as the primary material and integrating it

with architecture, Gehry is able to create a public square where tapestry is accessible to all

people. No longer confined to cramped rooms in dusty museums and castles, tapestry can now

move into a centralized and outdoor space. This egalitarian shift is fitting for Eisenhower, a man

dedicated to the values of equality and democracy.

Conclusion

Frank Gehry’s design is fitting for Eisenhower’s memorialization. It is a difficult task to

reflect in brick and mortar a legacy as complex and multifaceted as Eisenhower’s. The

achievements and character of the general and president deserve a timeless and powerful

monument which embodies his values. Tapestry, spanning time as an art and craft, resonates

fundamentally at a human level. By combining it with columns, Gehry has given tapestry the

gravitas and scale fitting of a presidential memorial. In fact, the meaning caught up in tapestry –

its association with military victory and its shift from the private sphere to the public square –

makes the design uniquely appropriate for Ike.

Page 19

Bibliography Ackerman, Phyllis. Tapestry: The Mirror of Civilization. New York: AMS Press, 1970. Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier and President. New York: Simon and Schuster: 1990. “American Tapestry.” The Decorator and Furnisher 20.2 (May, 1892): 55-56. Anderson, John D. “The Bayeux Tapestry: A 900-Year-Old Latin Cartoon.” The Classical

Journal 81.3 (Feb. – Mar., 1986): 253-257. Baron Courts of Prestoungrange & Dolphinstoun. “Displaying the Prestonpans Tapestry – in

Prestonpans.” Accessed August 9, 2011, http://www.globalartsandtourism.net/prestoungrange/html/news/show_news.asp?newsid=2992.

BBC. “’Longest’ tapestry tells story of Bonnie Prince Charlie.” Accessed August 11, 2011,

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-10764176. Brooklyn College Classics Department. “The Painted Stoa.” Accessed August 11, 2011,

http://depthome.brooklyn.cuny.edu/classics/dunkle/athnlife/poikile.htm. Brooks, Stephen and Eve Eckstein. Operation Overlord: The History of D-Day and the Overlord

Embroidery. London: Danilo Printing Ltd., 1983. Camp II, John McKesson. “Excavations in the Athenian Agroa: 2002-2007.” Hesperia: The

Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 76.4 (Oct. – Dec., 2007): 627-623.

Carroll, Dianne Lee. “Dating the Foot-Powered Loom: The Coptic Evidence.” American Journal

of Archaeology 89.1 Centennial Issue (Jan., 1985): 168-173. Clarke, C. Purdon. “A Piece of Egyptian Tapestry.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin

2.10 (Oct., 1907): 161-162. Creighton, Thomas H. The Architecture of Monuments: The Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Memorial Competition. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1962. Downs, Joseph. “The Capitol.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1.5 (Jan., 1943): 171-174. Dumbarton Oaks, “All T’oqapu Tunic,” accessed August 11, 2011,

http://museum.doaks.org/VieO23071?sid=381&x=21331.

Page 20

Edwards, Joan. Foreword to Conquest & Overlord: The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry and the Overlord Embroidery, by Brian Jewell, 8-9. New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1981.

Eisenhower, David. Eisenhower: At War, 1943-1945. New York: Random House, 1986. The Eisenhower Memorial Commission, “Guildhall Address,” accessed August 11, 2011,

http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/pages.php?pid=91. The Eisenhower Memorial Commission. “Our Mission.” Accessed August 3, 2011,

http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/menu.php?mid=28. Eisenhower, Susan. Foreword to Eisenhower College: The Life and Death of a Living Memorial

by David L. Dresser, xix. Interlaken, New York: Heart of the Lakes Publishing, 1995. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. “Jacquard Loom.” Accessed July 26, 2011,

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/299155/Jacquard-loom. Fosdick, Dean. “‘Living walls’ great backdrops for floral tapestry.” Accessed August 3, 2011,

http://www.timesunion.com/living/article/Living-walls-great-backdrops-for-floral-tapestry-1682116.php.

Francis, E. D. and Michael Vickers. “The Oenoe Painting in the Stoa Poikile, and Herodotus’

Account of Marathon.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 80 (1985): 99-113. Grooms, Thomas B. World War II Memorial: Washington, DC. Washington: U.S. General

Services Administration, 2004. Harvey, Nancy. Tapestry Weaving: A Comprehensive Study Guide. Loveland, Colorado:

Interweave Press, 1991. “The History of Tapestry.” The Art Amateur 2.2 (Jan., 1880): 34-36. Howard, Lady Mark Fitzalan. Foreword to Conquest and Overlord: The Story of the Bayeux

Tapestry and the Overlord Embroidery, by Brian Jewell, 52-53. New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1981.

Janssen, Rosalind M. “The ‘Ceremonial Garments’ of Tuthmosis IV Reconsidered.” Studien zur

Altagyptischen Kultur, 19 (1992): 217-224. Lewis, Suzanne. The Rhetoric of Power in the Bayeux Tapestry. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1999. Mercati e Foro di Traiano: Archaeological Area, “The Temple of Peace,” accessed August 11,

2011, http://en.mercatiditraiano.it/sede/area_archeologica/tempio_della_pace. Moore, Charles W. “Hadrian’s Villa.” Perspecta 6 (1960):16-27.

Page 21

National Civic Art Society. “Eisenhower Memorial Competition: 2011.” Accessed August 4,

2011, http://www.civicart.org/eisenhower.html. Norena, Carlos F. “Medium and Message in Vespasian’s Templum Pacis.” Memoirs of the

American Academy in Rome 48 (2003): 25-43. Oxford Dictionaries. “Tapestry.” Accessed July 19, 2011,

http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/tapestry?region=us. The Prestonpans Tapestry. Accessed August 3, 2011,

http://www.prestoungrange.org/tapestry/The_Tapestry.aspx. Robinson, David. “Author plans to tell story of Scotland with one of world’s biggest tapestries.”

Accessed August 4, 2011, http://news.scotsman.com/scotland/Author-plans-to-tell-story.6746688.jp.

Russel, Carol K. The Tapestry Handbook: An Illustrated Manual of Traditional Techniques.

Asheville, North Carolina: Lark Books, 1990. Stubbs, Angela. “The Villas and Gardens of Lazio.” Accessed August 15, 2011,

http://www.cornwallgardenstrust.org.uk/journal/cgt-journal-2008/the-villas-and-gardens-of-lazio/.

Thomson, Francis Paul. Tapestry: Mirror of History. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1980. Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Augustan Rome. Bristol Classical Press: London, 2000.

Page 22

Appendix A: Images for Reference

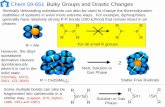

Figure 1: “Plain weave,” shown here is fundamental to tapestry, the interlocking of perpendicular warp and weft threads in an over-under pattern.87

Figure 2: This image, one of the earliest depictions of weaving, comes from the tomb of Beni-Hassan in Egypt (3000 BC). The figures on the top are shown spinning thread in preparation for weaving done on a simple high-warp loom.88

Figure 3: These tapestry fragments, dating to the 15th century BC, bear the name of Amenhotep III, a Pharaoh of Egypt. They are the oldest extant examples of tapestry we have.89

87 Harvey, Tapestry Weaving, 8. 88 Thomson, Tapestry, 25. 89 Janssen, “The ‘Ceremonial Garments’ of Tuthmosis IV,” 225.

Page 23

Figure 4: This nineteenth century Chinese k’o-ssu tapestry depicts a princess being greeted by Immortals and scholars as she descends from the sky on a bird. Taoist themes and symbols appear throughout the piece.90

Figure 5: An Incan weaving, intended to be worn as a tunic. This garment would have been a symbol of status for its wearer. In fact, so fine were textiles, that they were valued more highly than gold in the Incan Empire. The pattern of images may be significant symbolically. The Incans never developed a written language, so tapestry gave a way to communicate and to record.91

90 Thomson, Tapestry, 151. 91 Dumbarton Oaks, “All T’oqapu Tunic,” accessed August 11, 2011, http://museum.doaks.org/VieO23071?sid=381&x=21331.

Page 24

Figure 6: A Coptic tapestry from the 2nd to 3rd c. AD. A number of tapestries survived from antiquity in Egypt due to the dry conditions in the desert. This tapestry shows evidence of “ressaut,” or the technique of weaving without being constrained by the perpendicular warps and wefts.92

Figure 7: The Life of Cyrus, as it would have originally been displayed, currently sits in the home of the Marquess of Bath near Warminster. Tapestries were not meant to stand alone but were intended to be integrated with the furniture and architecture of the room.93

92 C. Purdon Clarke, “A Piece of Egyptian Tapestry,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 2.10 (Oct., 1907): 162. 93 Thomson, Tapestry, 75.

Page 25

Figure 8: This tapestry, woven of wool and silk at the Gobelins manufactory in Paris, depicts a scene of Theagenes and Chariclea from the Aethiopica, a tale written by Heliodorus of Emesa. The story was a popular subject of tapestries in the seventeenth century. The extremely ornate border, typical of baroque tapestries, has the effect of crowding the central scene.94

Figure 9: This wall hanging, made of silk and wool, depicts Hercules initiating the Olympic Games. The garb in the scene, however, is suggestive of the fifteenth century, when the tapestry was made. The central figures resemble Phillip the Good of Burgundy and Charles the Bold, his son, an obvious attempt to connect the owners of the tapestry to the mythological hero.95

94 Ibid., 117. 95 Ibid., 66.

Page 26

Figure 10: This cartoon, commissioned by Pope Leo X, was painted by Raphael between 1515 and 1516. It was part of a series from the Acts of the Apostles. This image depicts The Healing of the Lame Man by St. Peter and St. John at the Beautiful Gate of the Temple. According to Thomson, these cartoons mark the beginning of the Renaissance for tapestry.96

Figure 11: The Bayeux Tapestry, technically an embroidery, is one of the most famous examples of textile art. The tapestry tells the story of Harold’s treachery and William the Conqueror’s invasion of Britain. The scene shown here comes from the segment depicting the Battle of Hastings. The tapestry ends abruptly with the flight of Harold’s army, and many scholars believe that a scene depicting Williams coronation was originally at the end.97

96 Ibid., 92. 97 Jewell, Conquest and Overlord, 44.

Page 27

Figure 12: Detail from one of the War of Troy tapestries woven in 1475 by the Tournai workshop. The text inscribed on the characters, banners, and tent, as well as the captions at the base of the tapestry, informs the viewer of the scene depicted.98

Figure 13: The Cordoba Armorial Tapestry, woven in Salamanca by Pedro Gutierrez, features the crests of Cordoba, Santillan, Carrillo, and Mendoza de la Vega, celebrating the union of two Spanish nobles.99

Figure 14: A 1789 engraving by John Pine of an English tapestry celebrating the victory over the Spanish armada. The tapestries were lost when parliament burned down in 1834.100

98 Thomson, Tapestry, 69. 99 Ibid., 106. 100 Ibid., 107.

Page 28

Figure 15: In the tradition of the Bayeux Tapestry, this embroidery, the recently completed Prestonpans Tapestry, has captions and gives a narrative of the events leading up to the 1745 battle.101

Figure 16: The Overlord Embroidery, in the tradition of The Bayeux Tapestry, celebrates the successful invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. The tapestry resides in the D-Day Museum in the UK, but the cartoons are displayed in the Pentagon.102

Figure 17: The Stoa Poikile (Painted Stoa), built in the Athenian Agora after the Persian Wars of the early 5th c. BC, celebrated victory at Marathon and other battles. Behind the front colonnades were displayed images from history and mythology, as well as shields captured during various wars.103

Figure 18: The Prestonpan Tapestry, just completed in 2010, will be displayed in a circular pavilion, open to a central park area. The use of an outdoor space to display tapestry looks forward to Gehry’s innovative design for the Eisenhower Memorial.104

101 BBC, “’Longest’ tapestry tells story of Bonnie Prince Charlie,” accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-10764176. 102 Stephen Brooks and Eve Eckstein, Operation Overlord: The History of D-Day and the Overlord Embroidery, London: Danilo Printing Ltd., 1983. 103 Brooklyn College Classics Department, “The Painted Stoa,” accessed August 11, 2011, http://depthome.brooklyn.cuny.edu/classics/dunkle/athnlife/poikile.htm. 104 Baron Courts of Prestoungrange & Dolphinstoun, “Displaying the Prestonpans Tapestry – in Prestonpans.”

Page 29

Figure 19: The Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace) in Rome. It defined a large public space with water features and shrubbery. The columns on the side created an area to view statuary, paintings from Greece, and spoils from the Jewish Revolt. One scholar has described the structure as “an open air museum.”105

Figure 20: The “Canopus” at Hadrian’s Villa was surrounded by a series of columns. They had no practical function, but were used aesthetically to define the outdoor space and to frame a series of Greek sculptures and Egyptian works of Art, many of which now sit in the Vatican Museum. The architrave alternates between an arched and a “post and lintel” design.106

105 Mercati e Foro di Traiano: Archaeological Area, “The Temple of Peace,” accessed August 11, 2011, http://en.mercatiditraiano.it/sede/area_archeologica/tempio_della_pace. 106 Angela Stubbs, “The Villas and Gardens of Lazio,” accessed August 15, 2011, http://www.cornwallgardenstrust.org.uk/journal/cgt-journal-2008/the-villas-and-gardens-of-lazio/.

Page 30

Figure 21: One of Latrobe’s “Corn Cob Capitals.” American architects liked to use variants of classical designs that resonated with the nation’s identity. In this case, Latrobe felt that corn and tobacco were more appropriate plants than acanthus, the classical choice for Corinthian capitals.107

107 Joseph Downs, “The Capitol,” 173.

Page 31

Appendix B: Criticism and Counter-arguments: A number of commentators have come

forward and criticized Gehry’s design. The main lines of argument against the memorial are:

1. The design is not faithful to L’Enfant’s plan for the city

Counter-argument: L’Enfant’s highly esteemed plan for the city of Washington had its

critics and has undergone numerous changes (Ellicot, McMillan, etc.). Even so, Gehry’s

design is faithful to the basic elements of L’Enfant’s plan. It preserves the viewshed

along Maryland Avenue to the Capitol, as well as the orthogonal street grid. It does not

violate L’Enfant’s plan “by striving to create an additional square.”108 The area in front

of the Department of Education is already a public square, and Gehry’s design will more

effectively delineate the Maryland Avenue viewshed.

2. The design fails to incorporate classical elements

Counter-argument: As demonstrated in the narrative’s examples, tapestry is an ancient

art, and its use in a memorial is innovative without departing from traditional art.

Moreover, the use of colonnaded architecture to frame works of art dates to the classical

period (e.g. Stoa Poikile, 5th century BC; Templum Pacis, 75 AD; Villa Adriana, 117-125

AD; etc.). In fact, this established classical form is unknown in Washington. Bringing a

colonnade integrated with a work of art to the capital will add flavor to the city’s

architecture.

3. The woven metal tapestry will not work aesthetically or practically

Counter-argument: Recent tests done by contractors have shown the feasibility of the

tapestry design. Samples show that complex artistry is feasible and permits visibility for

the Department of Education. Indeed the subject, an Abilene landscape, is appropriate

considering Eisenhower’s background and the significance of landscape to American art.

108 Dhiru Thadani, “A misshapen memorial to President Eisenhower,” New Urban Network.

Page 32

4. Gehry is too controversial an architect for a presidential memorial

Counter-argument: Controversy surrounding monuments in Washington is nothing

new. John Russell Pope, the designer of the Jefferson Memorial, was criticized for his

classical design which was considered dull and stale, not fitting of our modern age. It is

normal for disagreements to arise during the process of creating monuments. Even the

celebrated Pierre L’Enfant had critics. He ultimately lost his job as the planner of

Washington and died in obscurity. Regardless of what one thinks of Frank Gehry’s

architectural resume, it is evident that he takes his job seriously and wants the monument

to have gravitas, capturing the essence of Eisenhower’s life and celebrating his

accomplishments.

5. The design is not fitting for Eisenhower’s humility and personality

Counter-argument: This is always a concern when building memorials to presidents.

The Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials were both considered too grandiose for presidents

of rural backgrounds. Likewise, conflicts emerged over the FDR memorial. Roosevelt

himself declared, “If they are to put up any memorial to me, I should like it to be placed

in the center of that green plot in front of the Archives Building. I should like it to consist

of a block about the size [of this desk].” But, despite the professed humility of

presidents, Americans have seen fit to memorialize great presidents. The proposed

memorial to Eisenhower celebrates the man’s life, while emphasizing his values and

origins. No togate colossal statue will dominate the public space. Instead, the colonnade

and tapestry will democratically create a park with images from the “heart of America,”

bringing a hero and statesman from Abilene to the nation’s capital.

6. Money should not be used for a memorial in Washington. There are already too

many.

Counter-argument: This criticism has been brought up before. In the 1960s, one critic

Page 33

of the planned FDR memorial declared that the city was “becoming a free-for-all for

memorials.”109 To be sure, we need to show restraint when we construct memorials, but

this will only be the seventh national presidential memorial in Washington. Its size and

cost are appropriate for a great American who destroyed Hitler and won eight years of

peace and prosperity for his country. The new memorial will revitalize space in the SW

quadrant of D.C. and will bring tourists to explore more of the city.

7. Money should not be used for a memorial. The federal government has enough on

its hands.

Counter-argument: In times of economic difficulty, restraint and prudence are needed.

At the same time, it is important to commit ourselves to celebrating our nation’s history

and honoring great Americans. Historically, crises have not prevented this. The capitol

dome was constructed in the Civil War and the Jefferson Memorial was begun during the

Great Depression and completed during World War II. The Eisenhower Memorial is

only asking for 80 percent government funding (the rest private), where many past

memorials have gotten 100 percent. Even as our government faces debts and deficits, it

is still important to commemorate Eisenhower’s far-reaching legacy.

109 Creighton, The Architecture of Monuments, 40.

Page 34

Appendix C: The Overlord Embroidery

The Overlord Embroidery has a special significance for Eisenhower. Not only does he

appear on it, but he organized and commanded the invasion. In light of this special connection,

as well as the Eisenhower Memorial Commission’s proposed “tapestry,” the Overlord

Embroidery deserves separate consideration.

In 1968, Lord Dulverton commissioned the embroidery to serve as “a tribute to the part

played by our country and countrymen in defeating a great evil that sprang upon the Western

World.” In many ways “the modern day counterpart” of the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry,

the Overlord Embroidery tells the story of the June 6, 1944 invasion of Normandy. The aim of

the tapestry is to “bring home to succeeding generations the message of sacrifice and selflessness

displayed by those who took part in Overlord.”

The embroidery is currently displayed in the D-Day Museum in Portsmouth, England. At

272 feet, it is one of the longest wall hangings of its type. The 34 panels trace the story of the

invasion from the start of the war to the defeat of the Germans in France. In many ways, this

tapestry provides a “broader view of war and its effects” than the Bayeux Tapestry, for the

Overlord Embroidery incorporates scenes from not just military but also civilian life. Mindful of

the contributions made by private citizens, the makers of the tapestry depict industry and

agriculture, as well as the hardships brought on by the war. Lord Dulverton wrote that the

tapestry was never meant to be “a tribute to war, but to our people in whom it brought out in

adversity so much that is good in determination, ingenuity, fortitude and sacrifice.”

Eisenhower also understood the sweeping effects of war. He said, “I hate war as only a

soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity.” Far

from glorifying war, Eisenhower understood the importance of sacrifice and the call of duty. In

his role as Supreme Allied Commander, he led the invasion of Normandy and the subsequent

“Crusade in Europe.” For his central role in the invasion, Eisenhower appears in three different

panels:

Page 35

The Overlord Embroidery, with its explicit relationship to the Bayeux Tapestry, is a

magnificent testament to the achievements of the allies in World War II. The Eisenhower

Memorial’s tapestry continues this tradition and adapts it to an American context. Suspended

from 80-foot columns, the monumental tapestry will feature the Abilene landscape, calling to

mind Eisenhower’s small town roots and juxtaposing those with his achievements in war and

peace. Indeed, Eisenhower’s story is that of the quintessential American. Like Washington, he

left his home to serve the state in war and, having secured peace, returned to private life. With

reluctance, he returned to public service as president, leading with vision and unswerving

integrity. Ike’s far-reaching legacy as a soldier and statesman deserves a splendid memorial,

steeped in tradition and powerful in meaning.

Page 36

Appendix D: Tapestry and the Eisenhower Memorial – A Commentary

The task of building a memorial to President and General Eisenhower is a daunting one, filled

with important new challenges. Perhaps the largest problem facing the Eisenhower Memorial

Commission is that Eisenhower was a complex man, a soldier, a statesman, and a citizen. In

many ways his life is made up of paradoxes. He was the last president born in the 19th century,

a man principled and devoted to tradition, yet he was a modern leader, receptive to change and

open to new ideas. He was a Kansan who left his home to serve his country. He was a general

who hated battle. Few men knew war better than he and fewer did more to prevent it.

A fitting memorial for Eisenhower must express Eisenhower’s strongest convictions, his

monumental achievements, and his modest background. This general and president was a man

from middle-America, upon whose heart was inscribed the value of “Duty, Honor, Country.”

The values embodied in the Kansas landscape would serve as the background for the overall

canvas on which Eisenhower’s life played out. His is the story of “a barefoot boy” who left his

home to serve his country. With unswerving integrity, he led an army of allies to total victory

and continued serving his country until retiring to private life. “Called to a higher duty” he

returned to the service of his country as the first NATO commander. He then became president

and presciently led the United States to eight years of peace and prosperity.

The Eisenhower Memorial Commission selected a design by world-renowned architect Frank O.

Gehry. The design features ten monumental 80-foot columns supporting a metal “tapestry” with

scenes from Abilene, Kansas, Eisenhower’s boyhood home. The core memorial area will have

statuary of Eisenhower as a boy, as a general, and as a president. Stones inscribed with

quotations will articulate Eisenhower’s views on peace, democracy, and freedom. This design –

especially the tapestry – is uniquely appropriate to memorialize Eisenhower:

Tapestry’s lengthy history testifies to its survivability, longevity, and continued

relevance. The art of weaving dates to prehistory, and tapestry is over 5,000 years old.

It has remained an important element of Western culture in our history, literature, and art.

Page 37

Ancient and medieval tapestries have survived for hundreds – even thousands – of years,

often retaining much of their vivid color. Currently, Gehry Partners is planning for a

lifespan of at least two-hundred years for the stainless steel tapestry. This long-term

vision for the memorial is appropriate considering tapestry’s timelessness and remarkable

survivability.

Tapestry resonates not merely culturally but fundamentally at a human level. Since

prehistory, people have crafted baskets, rugs, and wall hangings using weaving

techniques which are fundamentally the same as those used today. According to one

scholar, “tapestry has been especially closely bound up with the life of every time.” The

simplicity and beauty of this craft calls to mind Eisenhower’s experience in the

heartland—his boyhood in Abilene—where he learned the value of hard work,

dedication, and teamwork.

The art form’s broad cultural appeal is fitting for Eisenhower, a “citizen of the

world.” Although significant to Western cultures, tapestry is not exclusive to any one

people but is the shared treasure of all mankind. From Berlin to Beijing, from Cairo to

Kentucky, woven objects and textiles are used functionally and aesthetically.

Eisenhower’s actions, as general and president, show how earnestly he believed in trying

to forge bonds of friendship between nations. How appropriate, then, that he should be

memorialized with tapestry, an art form appealing to people of every creed and color, a

craft which calls to mind the ingenuity and thrift of hard-working Americans and people

the world over.

Tapestry has always evolved to meet new technological challenges, so a stainless

steel “tapestry” is a positive new step. What began as a “low-warp” loom, consisting

of four stakes stuck in the ground to support the warp threads, eventually became a

complex machine allowing for the speedy production of complex tapestries incorporating

cotton, wool, silk, metal, and other materials. The challenges confronted by the makers

of the Eisenhower Memorial’s tapestries are another chapter in the art form’s story of

Page 38

technological innovation. This is an apt approach for a memorial to Eisenhower, a

modern president who was receptive to change.

Historically, tapestry has been used to depict a wide variety of themes. Far from

being purely decorative, tapestries are used to tell stories and to inform. Mythological,

biblical, and historical scenes were popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The

Eisenhower Memorial will tell the story of Ike’s small town roots and juxtapose those

with a physical representation of the magnitude of his accomplishments in war and peace,

as a five-star general and as president of the United States.

Integrated with text, tapestry can be a powerful communicator. The Bayeux

Tapestry, described by one scholar as “one of the most powerful pieces of visual

propaganda ever produced,” uses Latin captions to narrate the story being played out in

the art. Likewise, the Eisenhower Memorial will use quotations by Eisenhower to give

context to the tapestry of the Abilene Landscape, the background for the overall canvas

upon which Ike’s life played out.

The use of columns to delineate an outdoor space for the public to view art is an

established classical paradigm. The Stoa Poikile, Forum Augustum, Templum Pacis,

and Canopus at Hadrian’s Villa all use columns to define outdoor space and facilitate the

enjoyment of art. In a similar way, the Eisenhower Memorial harmonizes artwork – the

tapestry – with a colonnade and, in doing so, creates an outdoor public space in which

people can engage with the life story and values of Eisenhower. Using this classical

paradigm to celebrate Eisenhower in a modern setting is particularily fitting to honor the

last president born in the 19th century, a man who laid the foundation for successful

transition to the 21st century.

• The synthesis of architecture and a stainless steel tapestry allows the viewing public

to experience this significant art form. Gehry’s design overcomes the traditional limits

on tapestry and makes it something public, for all to see. No longer confined to cramped

rooms in dusty museums and castles, tapestry can now move into a centralized outdoor

Page 39

space. This egalitarian shift is fitting for Eisenhower, a man dedicated to the values of

equality and democracy. It is appropriate that it is designed by Frank Gehry, who has

shared art forms with people throughout the world.

The integration in the Eisehower Memorial of tapestry, landscape, and statuary for

memorialization is unique and unprecedented. American monumental architecture has

always creatively adapted existing styles and art-forms into new designs. Even the

Lincoln Memorial, a seemingly conservative monument, deviates from the traditional

alignment and proportion of a Doric temple in order to create a uniquely American

monument. The Jefferson Memorial, although based on the Pantheon, is actually quite

unique in terms of material and layout. Likewise, the WWII, Vietnam, and Korean War

Memorials have no equals in design. The Eisenhower Memorial's unprecedented

integration of diverse elements - tapestry, landscape, and statuary - will make it a

memorable Washington site with deep connections to Eisenhower.

Frank Gehry’s design is fitting for Eisenhower’s memorialization. It is a difficult task to reflect

in brick and mortar a legacy as complex and multifaceted as Eisenhower’s. The achievements

and character of the general and president deserve a timeless and powerful monument which

embodies his values. Tapestry, spanning time as an art and craft, resonates fundamentally at a

human level. By combining it with columns, Gehry has given tapestry the gravitas and scale

fitting of a presidential memorial. In fact, the meaning caught up in tapestry – its association

with military victory and its shift from the private sphere to the public square – makes the design

uniquely appropriate for Ike.