Fourteen Bagatelles for piano op. 6: No. I, III, IV, V, VI ...

Transcript of Fourteen Bagatelles for piano op. 6: No. I, III, IV, V, VI ...

Fourteen Bagatelles for piano op. 6: No. I, III, IV, V, VI, VIII, and XI

by

Michaela Eremiášová

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the

Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy

Supervised by

Professor and Chair of Theory Department Jonathan Dunsby

Department of Composition Eastman School of Music

University of Rochester Rochester, New York

2011

Copyright©2010 by Michaela Eremiášová

All Rights Reserved

iii

Biography

Michaela Eremiášová (1974) was born in Prague, Czech Republic. Throughout

her studies and professional experiences as a composer of concert, jazz, and film music

she has had the opportunity to compose for various types of vocal and instrumental

ensembles, from soloists to orchestra, and in various genres and styles such as opera,

jazz, ethnic, and electro-acoustic music. Her personal study and research of various

musical traditions and techniques of composition is exemplified in the eclecticism of her

music.

Eremiášová’s music has been performed by ensembles such as Phil Wilson's

Berklee Rainbow Band, New York City Opera, the Arabesque Winds, ITB (Institut

Teknologi Bandung) Choir from Indonesia, Chamber Choir Hymni from Denmark, Duo

vio-Link-oto, Eastman Triana, Eastman Chorale, Eastman Trombone Choir, and the

Novus Quartet, among others. Here collaborations include work not only with great

performers but also with contemporary painters, poets, modern dance choreographers as

well as with experimental and mainstream film makers. One of her closest collaborators

is her colleague and husband, Colombian composer Jairo Duarte-Lopez, who is also a

PhD candidate in Composition at Eastman. Together, they co-composed and produced

the orchestral theme for the Toronto Blue Jays for the 2008 and 2009 baseball season as a

commission by Rogers Sportsnet (Toronto, Canada). In 2008, this score was broadcast

during 102 games on Canadian cable television. They also co-composed and produced

music for two documentaries for Discovery Channel Latin America. In addition, their

co-composed chamber work Car Crash Opera, for an animated film by Skip Battaglia,

iv

was selected as one of eight out of eighty submissions to be showcased at the 2009 New

York City Opera’s VOX Festival. In 2010, Michaela and Jairo were commissioned by

the Kurt-Weill Festival, the Eastman School of Music, and the George Eastman House, to

write music scores for live performance to eight short silent films from the 1910s to

1930s by renown European film makers Lotte Reiniger, Walter Ruttman, and László

Moholy-Nagy. The total program was over sixty minutes of music and was premiered at

the Arsenal Theater in Berlin’s Sony Center in January 2011. These scores were also

performed live at the George Eastman House and the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Eremiášová’s collaborative works with experimental film makers such as Stephanie

Maxwell, Jean Detheux, Skip Battaglia, Peter Byrne and Carole Woodlock, have been

featured in over sixty national and international film festivals such as Siggraph Computer

Animation Festival - Visual Music in New Orleans, Anima Mundi Festival in Sao Paolo,

Brazil, backup_festival in Weimar, Germany, and 27e édition des Rendez-vous du

cinéma québécois in Québéc, Canada, among others. Several of the collaborative projects

have been recognized with awards including the ASIFA Award for Excellence in

Experimental Techniques, Best Experimental/Animation/ Music Video award, Best New

Art Award, Best Impact of Music in Experimental, Performance Art and Art Films: Gold

Medal for Excellence, and Best Experimental Short award.

Since the fall of 2008, Eremiášová has been co-instructor, along with her husband, of

Film Scoring Techniques for the Department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media at

Eastman and has been teaching the same course at the Eastman Community Music

v

School since the fall of 2010.

Eremiášová holds a Bachelor of Music in Composition from the Conservatory of

Jaroslav Ježek; a Diploma Degree in Jazz Composition from Berklee College of Music,

and a Masters in Musicology from Charles’ University in Prague. She pursued doctoral

studies at the Eastman School of Music while serving as a teaching assistant in

orchestration, and Renaissance and Baroque music history courses. She also worked as a

teaching instructor in film scoring techniques and composition. Her composition teachers

at Eastman were David Liptak and Carlos Sanches-Gutierrez. She had additional study

with Mario Davidovsky.

vi

Abstract

This essay is dedicated to an analytical study of the Fourteen Bagatelles op. 6 by

Béla Bartók. The main focus is based on the impact of Slovak and Hungarian folk music,

and its modal heritage, upon Bartók’s fourteen Bagatelles: No. I, III, IV, V, VI, VIII, and

XI. These pieces are analyzed with an emphasis on folk-music sources, which are the

core of Bartók’s Bagatelles. The structure and modal content of folksong are the main

characteristics of his compositional style, newly developed during the years 1904 - 1908.

The goal of this research paper is to examine Bartók’s use of modes, their

transformations and the influence of folk music on these seven Bagatelles. The selected

Bagatelles are each based on one primary mode or set of notes. The further development

of the modal property has a crucial impact on the formal and harmonic structure of the

pieces.

vii

Table of Contents

Section Title Page

I. Introduction 1

Béla Bartók – Life and Work in 1904-1908 2 II. Slovak and Hungarian folk music, and its modal heritage 4 Slovak and Hungarian folk music 4 Tone systems 11

III. Analyses of seven Bagatelles 16

Bagatelle No. I 16 Bagatelle No. III 19 Bagatelle No. IV 24 Bagatelle No. V 26 Bagatelle No. VI 33 Bagatelle No. VIII 36 Bagatelle No. XI 43 IV. Conclusion 44 Bibliography 46

viii

List of Examples

Example # Title Page

Example 1 Maqăm Hijăz, Maqăm Şehnaz and Verbunkos modes 7

Example 2 Pentatonic scale 8

Example 3 Pure Pentatonic scale in folksong 9

Example 4 Pentatonic scale with scale degrees 2 and 6 as ornamental 9 notes Example 5 Pentatonic scale with scale degrees 2 and 6 as real notes 10

Example 6 Byzantine Modes versus Gregorian Modes 12

Example 7 Diatonic, Soft Chromatic, Hard Chromatic and 12-13 Enharmonic Genus

Example 8 The I. authentic Byzantine mode with the letters of the 13 Greek alphabet Example 9 Hard Chromatic versus Maqām Şehnaz 14

Example 10 Diatonic First Authentic versus Maqăm Bayyăti 14

Example 11 Turkish, Arabic, Byzantine and Western notes 15 between whole-tones Example 12 Bagatelle No. I: mm. 1 – 2 16

Example 13 Bagatelle No. I: mm. 1 – 3 17

Example 14 Bagatelle No. I: mm. 16 – 18 17

Example 15 Bagatelle No. I: mm. 5 – 6 18

Example 16 Bagatelle No. I: G half-diminished (Locrian) scale 19

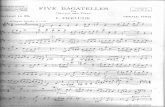

Example 17 Bagatelle No. III – score 20-21

Example 18 Bagatelle No. III -Verbunkos Phrygian scale 22

ix

Example 19 Bagatelle No. III - melodic structure 22

Example 20 Two harmonic entities in the Verbunkos Phrygian mode 23

Example 21 Bagatelle IV in D minor pentatonic 24

Example 22 Bagatelle IV – modal transformation in mm. 1 – 2 25

Example 23 Bagatelle IV – modal transformation in m. 8 25-26

Example 24 Slovak folk song 27

Example 25 Bagatelle No. V – score 28-30

Example 26 Bagatelle No. V - Gm and Dm harmonic entities 31

Example 27 Bagatelle No. V – modal transformations 31

Example 28 G Minor Pentatonic scale 32

Example 29 Bagatelle No. V: mm. 51 – 64 32

Example 30 Bagatelle No. VI: mm. 1 - 7 34

Example 31 Bagatelle No. VI - Verbunkos Phrygian scale 34

Example 32 Bagatelle VI – modal transformation 35

Example 33 Bagatelle VI - symmetrical modal formation 35

Example 34 Bagatelle No. VIII: mm. 1 – 10 37

Example 35 Bagatelle No. VIII: mm. 1 – 4 38

Example 36 Bagatelle VIII – main motif 38

Example 37 Bagatelle VIII – axis system 39

Example 38 Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 24 40

Example 39 Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 25 40

Example 40 Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 26 40

x

Example 41 Bagatelle VIII – score 41-42

Example 42 Bagatelle XI: mm. 1 – 7 43

Example 43 Bagatelle XI: mm. 8 – 16 43

1

I. Introduction

In the introduction of the score for the Fourteen Bagatelles op. 6, Béla Bartók

described his compositional style as “a reaction against the exuberance of the romantic

piano music of the 19th century, a style stripped of all unessential decorative elements,

deliberately using only the most restricted technical means.”1 As this quote suggests,

Bartók felt a need for change in his musical compositional style that would differ from

the traditional romantic style. The Bagatelles were composed in 1908 and are considered

the first series of short piano pieces which exposed Bartók’s elaborate new musical

language. 2 This new language involved a combination of folk and contemporary

techniques and concepts, as noted by Antokoletz in the article “The Musical Language of

Bartók’s 14 Bagatelles for Piano.”3

The Bagatelles clearly represent Bartók’s unique compositional style, which he

developed between 1904 and 1908. This stage of Bartók’s compositional career is

specifically important for two reasons. These years indicate the beginning and the

development of his folk music interest, and the rise of his new compositional style

starting in piano music, which is primarily influenced by his ethno-musicological

research.

1 Peter Bartok, “Notes of the Editor in 14 Bagatellen für Klavier,” in Béla Bartók’s 14 Bagatellen für Klavier (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1998), 40-47. The words come originally from Béla Bartók and were part of his introduction for the publication of 14 Bagatelles in 1940 which were not used in this edition. 2Grove Music Online, “Bartók, Béla, §3: 1908-14,” by Malcolm Gillies, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/. 3 Elliott Antokoletz, “The Musical Language of Bartók’s 14 Bagatelles for Piano,” Tempo, New Series, No. 137 (Jun. 1981).

2

The Fourteen Bagatelles, op. 6, is a collection of unconnected short piano

compositions. In other words, it is not a multi-piece that provides an organic unity of the

pieces.4 In my analysis, I am particularly interested in modal property that is primarily

based on an Eastern European modal heritage. Thus I have selected only certain

Bagatelles (No. I, III, IV, V, VI, VIII, and XI), because they best display this modal

property as a major base for the harmonic content and the structure of the pieces.

Béla Bartók – Life and Work in 1904-1908

In 1904, after his graduation from the Budapest Academy of Music, Bartók

revealed his interest in folklore for the first time. He felt that his musical language was

influenced by Romantic composers. For instance, his first opus-numbered pieces,

Rhapsody op.1 for piano and Scherzo op. 2 for piano and orchestra stylistically and

formally reflected Brahms, Strauss, and Liszt. Bartók was truly inspired by folk music

after he heard Lidi Dósa, a Transylvanian-Hungarian peasant girl singing a popular

Hungarian art song based on more complicated formal and tonal transformations. 5

Affected by Lidi Dósa’s songs, Bartók revealed himself in a letter to his sister in

December 1904: ”Now I have a new plan: to collect the finest Hungarian folksongs and

raise them, adding the best possible piano accompaniments, to the level of art-song.”6

The first sign of this change in Bartók’s compositional style can be seen in his first

4 “The idea of the multi-piece entails a sense of incompleteness in the individual pieces, but it does not automatically follow that a multi-piece thereby forms a complete whole that corresponds to a multi-movement work.” From Grove Music Online, “Multi-piece,” by Peter Foster, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/. 5 Bartók transcribed this folk song for voice and piano, and it was published as “Székely Folk song” in Magyar Lant, from Benjamin Suchoff, “Bartók’s Odyssey in Slovak Folk Music in Bartók Perspectives,” in Bartók perspectives: man, composer, and ethnomusicologist, 16. 6 Grove Music Online, “Bartók, Béla, §3: 1908-14,” by Malcolm Gillies.

3

publications, dated in February 1905: the setting of a Székely (Transylvanian) song Piros

alma (Red Apple) BB34, and a collection of settings of four folksongs BB37.

In 1905, Bartók received a grant for research on folk song in Transylvanian

villages and also established a collegial relationship with Zoltán Kodály. In 1906 he

collected about 120 tunes in the village of Grlice (now Gemerská, located in Slovakia in

the time of Bartók, Grlice represented a Slovak-Hungarian language border) and together

with Kodály made the first volume of transcribed Hungarian folk songs.

In the compositions written between 1908 and 1910, such as Fourteen Bagatelles,

Two Elegies, Two Roumanian Dances and Ten Easy Piano Pieces, folksong in Bartók’s

music became more than just a melody with an accompaniment; he incorporated it into a

more complicated compositional scheme, based on the formal and modal or tonal unity of

folksong. As noted by Dobszay, the greatest effect of folk music is an attachment to

modality, the great synthesis within which Bartók managed to unify the free use of

twelve notes and the widening of the results of permutational functional thinking.7 As

expressed by John Weissmann, Fourteen Bagatelles and Ten Easy Piano Pieces “may be

considered the best of introductions to modern music.”8

7 László Dobszay,“The Absorption of Folksong in Bartók’s Composition,” Studia Musicologica Adademiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 24 (Budapest 1981). 8 John Weissmann, “Bartók’s Piano Music,” Tempo, New Series, No. 14, Second Bartók Number (1949-1950).

4

II. Slovak and Hungarian folk music, and its modal heritage

Slovak and Hungarian folk music

Bartók’s intensive ethnomusicological research first focused on folk song in

Slovakian and Hungarian regions. Thus, it is suitable to assume that Slovakian and

Hungarian folk music was the main source for the Fourteen Bagatelles. This is apparent

mainly because of the fact that Bagatelles No. IV and V are actually based on folk

melodies from Slovakia and Hungary. 9 In order to better understand Bartók’s

compositional concepts in the Fourteen Bagatelles, it is important to reveal some of the

basic points of historical background and characteristics of Slovakian and Hungarian folk

music.

Slovakia is surrounded by Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary. It was a part of

the Czechoslovak Republic (Czechs, Moravians, and Slovaks) from 1918-1989. There are

three historical periods that had an impact on folk music in Slovakia. The first stage (ca

6th – 9th centuries) is characteristic for “pre-harmonic, old-style” songs that are mainly

associated with rituals to influence fate and control nature. Songs of this time were

generally based on a range of a second or third with short, repeated rhythmic formulas.

An ambitus of a fourth can be found in a repertoire of farmers’ fieldwork and harvest

songs, and songs for weddings and other rituals. A range of a fifth can be traced in old-

style shepherds’ songs in mountainous areas with improvisatory techniques. The second

stage (A.D. 863 – ca. 18th century) includes monophonic songs mainly based on Lydian,

9 Suchoff, 17 – 22.

5

Mixolydian, Hypoionian, and Dorian modes. Byzantine culture had its impact on Slavic

culture since the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius brought Christianity to the

Great Moravian Empire. The last stage (before 19th century) includes three types of

songs:

1. Songs with old-style rhythms and open construction (ABCD, AABB),

2. “New-Hungarian” style syncopated songs,

3. Songs reflecting Western melodic and harmonic influences.

The second and third types are based on closed forms such as AA5BA (A5 refers to

phrase A repeated a fifth higher). All three types of songs are based on major-minor tonal

principles.10

There was a long period of time (1526 - 1914) when Hungary, Slovakia, Moravia

and Bohemia were together as possessions of the Habsburg Empire, and later the

Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Therefore it is possible to find some musical similarities,

especially in Hungarian and Slovak folk music, in terms of strophic form, ornamentation,

modal quality, rhythm and mixed meter. The oriental aspect found in Hungarian folk

music is very peculiar however, and can be traced to different ethnic groups such as

Genghis Khan’s Mongols who reached the Carpathians in 1241, the Turks who ruled

Hungary from 1526 – 1686 (Ottoman domination) and the Gypsies who might have come

along with the Turks.

10 The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe,“Czech Republic and Slovakia,” by Magda Ferl Želinská and Edward J. P. O’Connor, 722-726.

6

Due to constant interaction with various ethnic groups, political, economic and

religious changes, Hungarian folk music is certainly a great source of multiple cultural

elements. The oldest songs come from peasant music that includes old-style songs based

on the pentatonic mode, songs found in the “psalmody” style, and the “lament” style

(children’s and ritual songs, funeral laments). According to Judith Frigyesi, it is possible

to assume that these old-style songs were based on Finno-Ugric (Magyarorszāg –

originally the Finno-Ugric nation) musical elements that existed before the Hungarian

conquest. 11

During the period of the Hungarian kingdom (11th – 15th centuries) the music of

the Magyars was influenced by Gregorian chants and European melodic styles. Although

there is no surviving evidence of the repertoire sung in this time, based on the influences

of all these cultures we can assume that the music had to involve Finno-Ugric, Turkish,

and medieval European folk and chant elements.12

According to Peter Manuel,13 the Gypsy community had a special impact on

secular Hungarian music. Gypsy musicians were kept as slaves by Ottoman and Eastern

European aristocrats. They specialized in a varied mixture of “exotic” and novel-

sounding melodies from different regions. They had preserved some Turkish musical

material. This may explain the occurrence of the Turkish modes, Maqām Hijāz and

11 The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe, “Hungary: History of Folk Music,” by Judith Frigyesi, 736-739. 12 Ibid. 13Peter Manuel, “Modal Harmony in Andalusian, Eastern European, and Turkish Syncretic Musics,” Yearbook for Traditinal Music vol. 21 (1989).

7

Maqām Şehnaz, in 17th century Hungarian folksongs.14 The existence of the so-called

Verbunkos modes15 might have developed from these types of Turkish scales, especially

the Verbunkos mode, called Kalindra. Comparing the modes Kalindra with Maqām

Hijāz, we can see the identical pitch content. See example 1.

Example 1: Maqām Hijāz, Maqām Şehnaz and Verbunkos modes

Maqām Hijāz Kalindra (Harmonic minor with lowered 2 and raised 3)

Maqām Şehnaz (with Western tempered intervals)

Verbunkos Minor (Harmonic minor with raised 4) Verbunkos Aeolian (Natural minor with raised 4)

Verbunkos Dorian (Natural minor with and raised 4 and 6)

Hungarian vocal songs are characteristic for being established on a strophic

structure, and for two rhythmic styles they are usually played in: the style parlando-

rubato and the style giusto. Parlando-rubato theoretically refers to the natural rhythm of

the spoken text. Speaking of practice, the music reflects metrical line-schemes based on

poetic rhythm. When asymmetrical rhythmic formations appear, they become steady

14 “Modal Harmony in Andalusian, Eastern European, and Turkish Syncretic Musics.” 15 W. Marvin, handout, “Scales, Modes and Collections in Western Music,” from Loya Shay, “The Verbunkos Idiom in Liszt’s Music of the Future: Historical Issues of Reception and New Cultural and Analytical Perspectives” (Ph. D. diss., King’s College, London, 2006).

8

patterns within the performance. Bartók called this phenomenon frozen rubato. The

rhythm in giusto style is based on a metric framework; however, there is certain

flexibility in the durational values. Parlando-rubato occurs mainly in solo performance,

giusto is typical for choral performance. It is important to note that Hungarian songs are

usually syllabic; however, ornamentation is in many cases crucial. According to older

recordings, ornaments were much longer and structurally more substantial before the 20th

century.16

The various melodic types of Hungarian folk music include several general

characteristics such as fifth-shifting,17 the use of the pentatonic scale, and related types

such as major-mode, descending, octave-range types, psalmody and lament styles.18 All

these styles were simply divided by Bartók and Kodály into old, new and mixed styles.19

As I already mentioned, the mode of tunes in the old style can be found in the pentatonic

scale. See example 2.

Example 2: Pentatonic scale

(F) G Bb C D F (G) (Bb)

According to Bartók, there are three basic forms of the pentatonic scale in old

style Hungarian songs:

16The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe, “Hungary: Genre, Style and Performance,” by Judith Frigyesi, 740-741. 17 Ibid. In other words, fifth-shifting refers to a melodic structure where the second half of a melodic line appears a fifth lower in the exact or tonally adjusted version of the 1st melodic line, found in László Vikár, “What Is Old and What Is New in the Traditional Music of the Volga-Kama Region,” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 37, Fasc. 2/4 (1996). 18 The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe, “Hungary: Melodic Types,” by Judith Frigyesi, 741-742. 19 Béla Bartók, “Hungarian Folk Music,” transl. by M. D. Calvocoressi (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), 11.

9

1) The pure pentatonic scale – see example 3.20

Example 3: Pure pentatonic scale in folksong

2) The pentatonic scale, in which the scale degrees 2 and 6 appear as ornamental

notes – see example 4.21

Example 4: Pentatonic scale with scale degrees 2 and 6 as ornamental notes in folksong

3) The pentatonic scale, in which the scale degrees 2 and 6 appear as real notes.

However they usually appear on a weak beat, never at the end of a melody. The

20 Bartók, 10-11. 21 Ibid.

10

appearances of additional scale degrees transform the pentatonic scale to Dorian,

Aeolian, or Phrygian modes. See example 5. 22

Example 5: Pentatonic scale with scale degrees 2 and 6 as real notes in folksong

The dominance of pentatony in Hungarian peasant music was first recognized by

Kodály. As he points out, pentatony is the fundamental layer of the Hungarian melopoeia.

The rhythmic aspect comes from dance and language. 23

22 Bartók, 17 – 18. 23 Zoltán Kodály, “Folk Music and Art Music in Hungary,” Tempo, New Series, No. 63 (Winter, 1962-1963). “Melopoeia is the art of forming melody; melody; -- now often used for a melodic passage, rather than a complete melody.” found in http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Melopoeia.

11

II. Tone systems

There are two important tone systems that had a crucial impact on Eastern

European modal development: the Byzantine and Arab systems. Both systems share the

same heritage of the Greek tone system.

The Byzantine system of eight modes, the Oktoechos, is ascribed to John

Damascene (676 – ca754 A.D.). In fact, it goes back to Oktoechos of Severus, the

Monophysite Patriarch of Antioch (ca. 512-19 A.D.). The Oktoechos also means a

liturgical book of the Eastern Churches, in which the hymns for the cycle of eight

consecutive Sundays are arranged in accordance with the eight modes. It is a remnant of a

calendar system used by the Sumerians, Akkadians and other ancient nations of West

Asia. The origin of this calendar, called the Pentecontades Calendar has a conception of

seven seasons and seven winds. Each wind corresponds to a god. The Ogdoas, a supreme

divinity ruled over these seven gods as it is mentioned in the Eighth Book of Moses.24

The set of eight notes consists of two sub-groups, the authentic tones and the

plagal tones. Each of the plagal tone is related to its corresponding authentic tone.

Therefore, the first four tones are the authentic tones and the second four are the plagals.

24 Hans Wilhelm Haussig, A History of Byzantine Civilization (New York: New York Press, 1971), 70.

12

Example 6: Byzantine Modes versus Gregorian Modes

Byzantine modes Gregorian modes

I. authentic I. Dorius

II. authentic III. Phrygius

III. authentic V. Lydius

IV. authentic VII. Mixolydius

I. plagal II. Hypodorius

II. plagal IV. Hypophrygius

III. plagal mode or Barys VI. Hypolydius

IV. plagal VIII. Hypomixolydius

Regarding the species of modes, Byzantine music does not recognize major and

minor scales as western music does. Byzantine music instead identifies four main modal

species: Diatonic, Enharmonic, Soft Chromatic, and Hard Chromatic. The Diatonic

category includes four modes: I. authentic and I. plagal, IV. authentic and IV. plagal.

The Enharmonic category consists of two modes: III. authentic and III. plagal. The

Chromatic category appears in two kinds of modes: Soft Chromatic mode applied to II.

authentic mode, and Hard Chromatic mode to II. plagal mode.25 See example 7.

Example 7: Diatonic, Soft Chromatic, Hard Chromatic and Enharmonic Genus: 26

Diatonic:

25 H. J.W. Tillyard, “The Modes in Byzantine Music,” The Annual of the British School at Athens vol. 22 (1916/1917-1917/1918). 26 Byzantine scales have precise tunings that have some intervals smaller than the Western semitone. The quartertones notated in example 7 are only approximations of a more complex intervallic structure found in Byzantine and Greek modes.

13

Soft Chromatic:

Hard Chromatic:

Enharmonic:

Byzantine civilization dates from the reign of the first Christian emperor,

Constantine the Great (ca. 300 A.D.). It is based on three primary factors: extension and

continuation of the Roman Empire,27 Greek tradition, and Christian religion.28 As already

mentioned, Byzantine civilization is considered to be a continuation of ancient Greece.

The notes of the I. authentic Byzantine mode are named after the first seven letters of the

Greek alphabet. See example 8.

Example 8: The I. authentic Byzantine mode with the letters of the Greek alphabet

The notes of the I. authentic mode: D E F G A B C

The first letters of the Greek alphabet: pa vu ga dhi ke zo ni

The first letters of the Greek alphabet in Greek: πα βου γα δι κε ζω νη'

27 Steven Runciman, Byzantine style and civilization (London: E. Arnold & co., 1933), 27. 28 Egon Wellesz, A History of Byzantine Music and Hymnography, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961), 31.

14

In opposition to the theory about Byzantine civilization being a continuation of

ancient Greece, the influence of Semitic and even Iranian civilizations was emphasized

on the Hellenized countries, which were the most important part of the Byzantine

Empire. 29 There is no doubt of the oriental impact on Byzantine music, which is

especially noticeable due to the chromatic and tuning alterations in the modes presented

in example 7. The Arabo-Turkish names were applied to the Byzantine modes by Greek

theorists, as for example Christodulus Georgiades.30 Therefore, it is hardly a coincidence

that the Hard Chromatic II. plagal mode versus the Turkish Maqăm Şehnaz, and

descending Diatonic I. authentic mode versus the Arabic Maqăm Bayyăti are identical.

See examples 9 and 10.

Example 9: Hard Chromatic versus Maqăm Şehnaz

Hard Chromatic:

Maqăm Şehnaz (with Western tempered intervals)

Example 10: Diatonic First Authentic versus Maqăm Bayyăti

Diatonic I. authentic:

Maqăm Bayyăti:

29 Haussig, 35. 30 Tillyard.

15

In comparison with the Western tone system, which distances notes by the same

interval (100 cents = half-tone) and therefore divides the octave into twelve tones, the

Byzantine, Arab and Turkish tone systems use microtones, three tones between each

whole-tone. 31 See example 11.

Example 11: Turkish, Arabic, Byzantine and Western notes between whole-tones32

Turkish, Arabic, and Byzantine notes between whole-tone

Western notes between whole-tone

31 Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, The Middle East, “The Eastern Arab System of Melodic Modes in Theory and practice: A Case Study of Maqām Bayyātí: The Invervals of Modern Arab Music,” by Scott Marcus, 36. 32 Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, The Middle East, “Contemporary Turkish Makam Practice: The Abstract Level: Makam Theory,” by Karl Signell, 48.

16

III. Analyses of seven Bagatelles

Bagatelle No. I

Regarding the modality of the Bagatelle No. I, there is some unique pitch content

based on two modes: C# Aeolian in the right hand and C Phrygian in the left hand.33 The

combination of both modes offers several modal formations. In mm. 1 – 2, the first three

ascending notes in the right hand and the first three descending notes in the left hand

together create a 5-note set of the C# symmetrical (whole – half – half –whole) modal

formation. It is identical to Messiaen’s third mode of limited transposition. See example

12.

Example 12: Bagatelle No. I: mm. 1 - 2

W H H W - P - (PALINDROME)

In mm. 1 – 3 the pitch content expands into a 7-note set of C symmetrical (half –

whole – half – half – whole – half) modal formation. 34 See example 13.

33 The score of the Bagatelle No. I is written in the dual key signature, with four sharps in the upper staff and four flats in the lower staff. 34 The term “symmetrical modal formation” is based on author’s theoretical construct and is not derived from an existing theory.

17

Example 13: Bagatelle No. I: mm. 1 - 3

H W H H W H

- P - The same pitch material also appears at the end of the piece (mm. 16 – 18) in a

more extended version. The entity of the type of the octatonic mode formed from this

content also can be considered symmetrical. See example 14.

Example 14: Bagatelle No. I: mm. 16 – 18

W H W H H W H W

- P -

18

The combination of C# Aeolian and C Phrygian, illustrated in the examples 12 –

14, creates a new modal symmetrical formation, surrounding note E. This pitch becomes

the center of a palindrome, the first and last note of two related Octatonic partials:35

I. = E, F, G, Ab, Bb

II. = E, D#, C#, C, Bb

Partial II is the second transposition of partial I. 36

M. 5 in the right hand and the first part of m. 6 in the left hand include a 5-note set

of the whole-tone scale. See example 15.

Example 15: Bagatelle No. I: mm. 5 – 6

The descending G half-diminished (Locrian) mode appears in the left hand in the

mm. 9, 11, and 15 – 17. See example 16.

35 Octatonic, as a designation for the scale or pitch class collection, is generated by alternating whole tones and semitones. A scalar order of the collection can begin with the semitone or the whole tone (the forms were termed ‘Model A’ and ‘Model B’ by van den Toorn). Only three distinct transpositions are possible. The collection is therefore a ‘mode of limited transposition’ under Messiaen’s definition (1944). From Grove Music Online, “Octatonic,” by Charles Wilson, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/. 36 E Octatonic mode based on partial I: E F G Ab Bb B C# D E

1st transposition: F F# G# A B C D D# F 2nd transposition based on partial II: F# G A Bb C C# D# E F#

19

Example 16: Bagatelle No. I: G half-diminished (Locrian) scale

In the 1920s scholars approached the Bagatelle No. I as a bitonal composition

because of the dual key signature. This view tended to divide the piece into two distinct

layers operating simultaneously yet separately. It is more accurate, however, to view this

Bagatelle as a united entity based on transformations of one particular mode. The pitch

material at the beginning and end of the piece can be considered a type of a C

symmetrical modal formation (see the examples 13 and 14). As László Somfai points out,

Bartók himself did not classify this piece as “bitonal,” or “polytonal.” He presented this

work as “simply a Phrygian colored C major.”37 Thus, the function of the dual key

signature in this Bagatelle offers a combination of two separate voices that creates a third

layer of cohesive chromatic material that resembles the melodic color of Hungarian and

Slovak folksong.

Bagatelle No. III

Although Bagatelle No. III does not include any reference to specific folksong

material; the piece carries certain folk elements such as the periodic character of the

melody, repetition, basic song structure, monophony, modality, melodic downward

motion, and static accompaniment. Because of these characteristics, it is possible to

37 László Somfai, “Nineteenth-Century Idea Developed in Bartók’s Piano Notation in the Years 1907 – 14,” 19the-Century Music, vol. 11 (1997).

20

assume that the folk elements implied in Bagatelle No. III come from folk song found in

Hungarian or Slovak regions. See the score in example 17.38

Example 17: Bagatelle No. III – score

38 Score in public domain, score analysis is by Michaela Eremiášová.

21

In this piece there is a prominence of one mode that can be found with many

names. The so-called Verbunkos Phrygian scale (Phrygian with raised 3)39 does not

appear only in the Hungarian Gypsy music repertoire, but also in the Arabic repertoire as

39 W. Marvin, handout, “Scales, Modes and Collections in Western Music,” from Loya Shay, “The Verbunkos Idiom in Liszt’s Music of the Future: Historical Issues of Reception and New Cultural and Analytical Perspectives” (Ph. D. diss., King’s College, London, 2006).

22

Maqām Hijāz.40 Its first tetrachord also corresponds with the following modes: the Arabic

Maqăm Şehnaz, and the Byzantine Hard Chromatic mode. See example 18.

Example 18: Bagatelle No. III -Verbunkos Phrygian scale

According to the mode, the tonal center is B. However, regarding the melodic line

in the left hand; there are two pitches that frequently appear throughout the piece: F# and

C. Although the note B occurs on weak beats, together with F# it creates a melodic frame

of the periodic antecedents. The note C appears in consequents. See example 19.

Example 19: Bagatelle No. III - melodic structure

The range of the B Verbunkos Phrygian mode is emphasized by a frequent

appearance of B4 as the highest note in the right hand, and B3 as the lowest note in the left

40 Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, The Middle East, “The Eastern Arab System of Melodic Modes in Theory and practice: A Case Study of Maqām Bayyātí: The Invervals of Modern Arab Music,” by Scott Marcus, 36-44.

23

hand (except one occurrence of A3 in the left hand in m. 22). Thus it is possible to assume

that the Bagatelle is centered on B.

The melodic line in the left hand together with some of the pitches in the right

hand (G, A, B) offers two harmonic entities, derived from the mode: B7 ( I ) and CMaj7

( bII ). See example 20.

Example 20: Two harmonic entities in the Verbunkos Phrygian mode

The B Verbunkos Phrygian mode appears in several transformations to other

modes, such as the octatonic and chromatic modes. In mm. 3 – 10, pitch material in the

left hand is based on five notes of the Verbunkos mode. In mm. 11 – 14, the mode is

transformed to five notes of an octatonic collection, and it is further transformed in mm.

15 – 18 to a 6-note chromatic collection that completes, with the music material in the

right hand, an aggregate.

In the Bagatelle No. III I peruse the pitch content through chromatic pitch space

with the main interest in Bagatelle’s modal material, based on one particular mode

derived from Hungarian modal heritage, which includes the Byzantine, Arabic, Turkish

tone systems and the Verbunkos modes. Example 19 illustrated the pitch content with an

emphasis on the B Verbunkos Phrygian mode, its modal transformation, and its impact

on the harmonic and formal structure of the piece. See examples 19 and 20.

24

Bagatelle No. IV

As noted by Antokoletz, the Bagatelle No. IV uses an old Hungarian folksong as

the source, collected by Bartók in 1907 in Felsöiregh.41 If we only consider the pitches on

down beats in the melodic line of the right hand, then the song is based on the D minor

pentatonic scale. Referring to Bartók’s idea of three basic forms of the pentatonic scale in

old style Hungarian songs, this Bagatelle is based on the third type of the pentatonic scale

(cf. example 5 in section II - Slovak and Hungarian folk music), in which the scale degree

six appears as a real note. This note Bb occurs only on off-beats. See example 21.

Example 21: Bagatelle IV in D minor pentatonic

In mm. 1 – 2, the appearances of the additional scale degrees (E, Bb) from the

melodic line and chordal accompaniment transform the pentatonic scale into the Aeolian

mode. See example 22.

41 Elliott Antokoletz, “The Musical Language of Bartók’s 14 Bagatelles for Piano.”

25

Example 22: Bagatelle IV – modal transformation in mm. 1 - 2

On the first beat of m. 8, the pitches in the right and left hands include an almost

complete G Mixolydian mode. See example 23. On the second and third beats of m. 8, the

notes in the right and left hands create a symmetrical modal formation. See the 2nd part of

example 23.

Example 23: Bagatelle IV – modal transformation in m. 8

26

W min3 H H H H min3 W - P –

It is understandable that Antokoletz approaches this Bagatelle from a harmonic

point of view. His focus is primarily on intervallic properties of the chordal

harmonization of the Hungarian tune. However the modal content of the song, built on

the D minor pentatonic scale, is the essence for the chordal harmonization and the modal

transformation.

Bagatelle No. V

Bagatelle No. V includes a Slovak folk song that is actually a Hungarian tune,

published in the second volume of Bartók’s Slovak folk songs collection. See example

24.42

42 Benjamin Suchoff, “Bartók’s Odyssey in Slovak Folk Music in Bartók Perspectives,” in Bartók perspectives: man, composer, and ethnomusicologist (London; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 17.

27

Example 24: Slovak folk song

The translated text43 of the Slovakian folk song is as follows:

Oh, in front of our house, in front of our house,

in front of our doors, in front of our doors,

Oh, a handsome lad, a handsome lad is planting a white rose.

According to Benjamin Suchoff the structure of this Slovak folk song is based on

the symmetrical Hungarian pentatonic scale. The circled notes in example 24 suggest the

scale degrees A and E are neighbor and passing tones that switch the pentatonic scale into

the Dorian mode.44 This modal transformation is typical in old-style folk melodies, as is

noted by Bartók in his book, Hungarian Folk Music. If the other degrees of the

pentatonic scale appear as real notes (usually on weak beats), they change the pentatonic

scale into a different mode. It is possible to notice that in terms of rhythm, the basic

pattern is preserved in a simplified version. This Slovak folk song is based on a mixture

of duple and triple meter, while the Bagatelle no. V is simply in duple meter. Regarding

the modal content, Bagatelle No. V is based on the G and D minor pentatonic scales and

their transformations: the Aeolian and Dorian modes. See the score in example 25.

43 Peter Bartok, “Notes of the Editor in 14 Bagatellen für Klavier,” in Béla Bartók’s 14 Bagatellen für Klavier (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1998), 40-47. 44 Suchoff, 17.

28

Example 25: Bagatelle No. V – score:45

45 Score in public domain, score analysis is by Michaela Eremiášová.

29

30

The melodic line of the entire piece is based on asymmetrical periodic structure,

in which the antecedent is built on the D pentatonic/Dorian modes, and the consequent is

built on the G pentatonic/Dorian modes. The property of the modes has an evident

impact on the structure of the chord in the right hand, which accompanies the main

31

melody in mm. 1 – 20. Its harmonic function implies two harmonic entities, G and D

minor, derived from the D pentatonic/Dorian and G pentatonic/Dorian modes. See

example 26.

Example 26: Bagatelle No. V - Gm and Dm harmonic entities

The modal transformation from the D minor pentatonic to the D Aeolian in the

left hand occurs in mm. 5 -11, and the G minor pentatonic scale is established in mm. 12

– 19. See example 27.

Example 27: Bagatelle No. V – modal transformations

The passage in mm. 20 – 27 is based on the G minor pentatonic scale. See

example 28.

32

Example 28: G Minor Pentatonic scale

The same melody appears in the right hand in mm. 28 – 45 with a different

chordal accompaniment. For the first time there is an appearance of a harmonic

progression derived from the G Dorian mode.

The chordal accompaniment in the right hand (in mm. 51 – 56) changes the

character of the G pentatonic mode to the G Mixolydian mode, and in mm. 57 – 62 to the

D Dorian mode. A short transition to the G minor pentatonic mode appears in mm. 63 –

64. See example 26.

Example 29: Bagatelle No. V in mm. 51 – 64

The main melody appears again in the left hand in m. 54 and is based on the G

minor pentatonic scale.

33

As Suchoff correctly points out, the chordal accompaniment is derived from the

melody.46 As with the Bagatelle No. IV, Bagatelle No. V is another example of the use of

folk song modal material, which has a crucial influence on the harmonic and formal

structure of the piece.

Bagatelle No. VI

The melodic framework of the Bagatelle No. VI resembles folk song. This can be

assumed because of its modality, repetition, variation and its clear repeated rhythmic

pattern. See example 30.

46 Quote from Benjamin Suchoff, Bartók’s Odyssey in Slovak Folk Music, 17.

34

Example 30: Bagatelle No. VI: Sentence47 in mm. 1 – 7

The modal content at the beginning of the Bagatelle (mm. 1 – 2) in the right hand,

is built on a 6-tone set (B C D# E# F# A#). The first five pitches of the set, except the

scale degree four (circled in the following example), correspond with the Verbunkos

Phrygian scale. See example 31.

Example 31: Bagatelle No. VI - Verbunkos Phrygian scale

47 Sentence is a musical term adopted from linguistic syntax that represents a complete musical idea. The construction of the beginning (the presentation of a basic idea and its repetition) determines the construction of the continuation. From Arnold Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, (Oxford: Alden Press, 1973).

35

At the end of m. 2, the 6-tone set in the right hand gets expanded into another

modal formation, which consists of two overlapped tetrachords, based on B octatonic and

D# pentatonic modes. See the modal transformation in example 32.

Example 32: Bagatelle VI – modal transformation

By the end of m. 7, the modal content in both hands creates an 11-tone

symmetrical modal formation. See example 33.

Example 33: Bagatelle VI - symmetrical modal formation

H H H H H W H H H H H

36

Although we do not know if this Bagatelle is based on a folk song source,

Bartók’s compositional procedure follows the same steps, traced in previous Bagatelles

No. I, III, IV and V.

Bagatelle No. VIII

Bagatelle No. VIII represents Bartók’s more complicated compositional concept

of folk song. According to Forte, the overall structure has an “unfolding” character based

on a primary set of notes. 48 As Forte explains the unfolding in his analysis, there is a set

of three predominant tones in mm. 1 - 4: C, G, and B. The role of C can be considered as

a preparation to B. The next important tones are Eb (D#) in m. 5, followed by B in mm. 6

– 8, and G in mm. 9 – 10. 49 As Forte points out in his sketch 37, these structural notes (G

– B – Eb – B – G) are not only prominent in mm. 1 – 10, but they also continue to appear

throughout the rest of the Bagatelle in slightly different groupings: G – Eb – B – G (in

mm. 16 – 24), and G – B – G (in 25 – 32).50 These notes clearly reflect an equal division

of the octave in three major thirds (G – B – D#/Eb – G) and are obviously the main

pillars of the Bagatelle’s melodic and harmonic structure according to Forte’s theory. In

my analysis, I focus on a single primary motif, its elaboration and its impact on harmonic

and melodic structure of the Bagatelle. See Example 34.51

48 Allen Forte, Contemporary tone-structures, (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1955), 75. 49 Forte, 75-76. 50 Forte, 169. 51 The first three systems of example 34 are based on the score from public domain, the score analysis and the fourth system in the same example were made by Michaela Eremiášová.

37

Example 34: Bagatelle No. VIII: mm. 1 – 10

In mm. 1 - 6, there is a clear embellished statement that ends in the middle of m.

6. (There is a breath mark in the score). The passage in mm. 1 - 6 consists of two parts

based on the main motif in mm. 1 - 2 and its slight variation in mm. 3 - 4, and therefore

the tones C#, B, A, C and D# are predominant in this part. See example 35.

38

Example 35: Bagatelle No. VIII – mm. 1 - 4

The framework of the main motif (C#5 - B4 - A4 - C4) is C#5 - A4 - C4, if we

consider B4 as a passing tone. It is transposed into the bass in the left hand (G#3 – E2 –

G2), and has an important harmonic and structural role in the first section (mm. 1 - 10).

See examples 36 and 37.

Example 36: Bagatelle VIII – main motif

This section A (mm. 1 - 10) can be perceived as a kind of asymmetrical period

with its antecedent (mm. 1-6) and consequent (mm. 6 - 10). The predominant tones in

section A are C# (m. 1), E (m. 5), G (m. 9) and Bb (m. 10), and are based on the axis

system.52 See example 37.

52 Axis system is based on the circle of fifths. If, in the circle of fifths, C is considered the tonic, than F will be the sub-dominant, G the dominant. D is the relative of F (S function), A the relative of C (T function) and E the relative of G (D function). This can be applied to the whole circle of fifths, in which case the three principal functions are periodically repeated. The 'axis' grouping consists of minor-third-related tonalities that split the octave symmetrically into four parts. From Roy Howat, “Bartók, Lendvai, and the principles of proportional Analysis,”Music Analysis 2/1 (March 1983), András Szentkirályi, “Some aspects of Bartók’s Compositional Techniques,” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 20 (March 31, 2008), Ernö Lendvai, Tonal Principles in Béla Bartók. An analysis of his music, (England: Stanmore Press, 1971), 1 -16.

39

Example 37: Bagatelle VIII – axis system

Section B (mm. 12 - 23) can be considered as a sort of development. In mm. 12 -

15 the main motif appears again in a transposed version, and is partly inverted (m. 12).

The leaps of the motif are expanded and are based on the AUG8/or Min9 that is the frame

of the main motif in its original version. It is interesting to follow some modal formations

in this section: the octatonic triad (G, Ab, Bb) in upward motion in the right hand in m.

16, an octatonic tetrachord (F#, F, Eb, D) in downward motion in the right hand in m. 17,

an octatonic hexachord (Ab, Bb, Cb, Db, Eb, E) in upward motion in the right hand in m.

18, a whole tone 5-note set (E, D, C, Bb, Ab) in downward motion the right hand in m.

18, and two overlapping tetrachords (F#, G, Bb, B / B, C, Eb, E) in upward motion in the

right hand in m. 21, which correspond with the first tetrachords of the Turkish Maqăm

Hijăz, the Arabic Maqăm Şehnaz, the Byzantine Hard Chromatic mode, the Verbunkos

Phrygian mode and the Verbunkos Kalindra mode.

40

The original motif in mm. 1 - 2 appears again in a rhythmic diminution in m. 24.

See example 38.

Example 38: Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 24

In m. 25 the motif occurs in a transposed and slightly varied version. The basis of

this motif is on G - Eb - G. See example 39.

Example 39: Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 25

In m. 26 the same motif appears in a modified and transposed version. See

example 40.

Example 40: Bagatelle VIII – main motif in m. 26

As Forte noted, the last section A1 consists of two phrases, which create a period,

antecedent in mm. 24 - 25 and consequent in mm. 26 - 27. They are related to section A.

41

The last part in mm. 28 - 32 can be perceived as a coda. It is obvious from this

part that Bartók wanted to emphasize the tonal centre of the piece based on the tone G.

Also, the important appearance of F# in m. 28 and m. 31 has an evident tonal resolution

to G. See the score – example 41.53

Example 41: Bagatelle VIII – score

53 Score in public domain, score analysis is by Michaela Eremiášová.

42

43

Bagatelle No. XI

The Bagatelle No. XI is the last example of Bartók’s compositional procedure,

based on more intricate modal content, and its impact on the melodic and formal structure

of the piece. For instance, an 8-note set of a symmetrical modal formation, based on

octatonic pentachords at the beginning of the piece, creates a foundation for the first

section A (mm. 1 – 16) of the Bagatelle’s song-form (AA1BA). The melody based on this

formation occurs in mm. 1 – 7 in the right hand, harmonized in fourths. (See example

42.) In mm. 8 – 16 the melodic line transforms into a transposed and slightly modified

version and creates another symmetrical modal formation. (See example 43.) The circled

notes in example 43 are the modifications of the melody in example 42.

Example 42: Bagatelle XI: mm. 1 - 7

H W H W W H W H - P -

Example 43: Bagatelle XI: mm. 8 – 16

H W W H W W H H

44

IV. Conclusion

The crucial characteristic of Bartók’s elaborate new musical language in seven of

the Fourteen Bagatelles is the use of modal symmetrical formations and transformations.

As I already emphasized, folk song plays a crucial role in Bartók’s compositional

procedure. As noted by Manuel, there are significant categories of secular, modal,

monophonic or heterophonic folk songs in Eastern Europe, which include different

formal sections in discrete modes and often use various tonic ground-notes.54 This aspect,

described by Manuel, is followed by Bartók in his seven Bagatelles. The pitch content of

each separate piece is built on one particular mode, or set, that is expanded and therefore

transformed into other modes. The primary mode, or set, allows for further modal

transformations and symmetrical formations, chordal harmonization and the overall form

of the individual Bagatelle. As brought up by Suchoff, the chordal accompaniment in

Bagatelle No. IV is derived from the melody, based on the Hungarian folk song. We

already know from the analysis that the melody is based on one specific mode--D Minor

Pentatonic mode--which creates a foundation for the piece.

The most effective analyses, therefore, should take the source of the music as a

point of departure. Some published articles refer to individual Bagatelles, 55 but

54 Peter Manuel, “Modal Harmony in Andalusian, Eastern European, and Turkish Syncretic Musics,”75. 55 Elliott Antokoletz, “The Musical Language of Bartók’s 14 Bagatelles for Piano,” [article on-online], Zoltán Kodály, “Folk Music and Art Music in Hungary,” [article on-online], László Dobszay, “The Absorption of Folksong in Bartók’s Composition,” [article on-line], Friedemann Sallis, “La transformation d’un heritage: Bagatelle op. 6 no 2 de Bela Bartok et Invencio (1948) pour piano de Gyorgy Ligeti,” Revue de Musicologie, T. 83e, No. 2e (1997), László Somfai, “Invention, Form, Narrative in Béla Bartók’s Music,” [article on-line], László Somfai, “Nineteenth-Century Ideas Developed in Bartók's Piano Notation in the Years 1907-14,” Vol. 11, No. 1, Special Issue: Resolutions II (Summer, 1987), János Kárpáti, “Perfect and Mistuned Structures in Bartók’s Music,” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum

45

nevertheless most of the analytical treatises, such as Forte’s analysis of Bagatelle No.

VIII 56 and Antokoletz’s analyses of six Bagatelles,57 focus on a harmonic content, and

exclude the importance of modal quality that has such a crucial impact on the overall

structure in Bartók’s Bagatelles.

Bartók himself hinted about his compositional thinking when he said that

Bagatelle No. I is written in “simply a Phrygian colored C major.”58 There is a reason he

did not characterize his work as a bitonal composition. Bartók’s compositional approach

followed the monophonic or heterophonic aspect, so essential in folk song.

Hungaricae, T. 36 (July, 1995), [article on-line], Suchoff, Bartók’s Odyssey in Slovak Folk Music in Bartók Perspectives, Allen Forte, Contemporary tone-structures. 56 Forte, 75. 57 Antokoletz, “The Musical Language of Bartók's 14 Bagatelles for Piano.” 58 László Somfai, “Nineteenth-Century Ideas Developed in Bartók's Piano Notation in the Years 1907-14.”

46

Bibliography:

Antokoletz, Elliott. “The Musical Language of Bartók’s 14 Bagatelles for Piano.” Tempo, New Series, No. 137 (Jun. 1981). Antokoletz, Elliott, Fischer, Victoria, and Suchoff, Benjamin, eds. Bartók Perspectives. Man, Composer, and Ethnomusicologist. London; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Bartók, Béla. 14 Bagatellen für Klavier. Budapest: Editio Musica, 1998.

Bartók, Béla. Hungarian Folk Music. Trans. by M. D. Calvocoressi. London: Oxford University Press, 1931. Dobszay, László.“The Absorption of Folksong in Bartók’s Composition.” Studia Musicologica Adademiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 24 (Budapest 1981). Forte, Allen. Contemporary tone-structures. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1955. Foster, Peter. “Multi-piece,” From Grove Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/. Frigyesi, Judith. “Hungary.” The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe, Vol. 8, New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2000. Gillies, Malcolm. “Bartók, Béla, §3: 1908-14,” Grove Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/. Haussig, Hans Wilhelm. A History of Byzantine Civilization. New York: New York Press, 1971.

Kárpáti, János. “Perfect and Mistuned Structures in Bartók’s Music.” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 36 (July, 1995).

Kodály, Zoltán. “Folk Music and Art Music in Hungary.” Tempo, New Series, No. 63 (Winter, 1962-1963). Lendvai, Ernö. Tonal Principles in Béla Bartók. An analysis of his music. England: Stanmore Press, 1971. Manuel, Peter. “Modal Harmony in Andalusian, Eastern European, and Turkish Syncretic Musics.” Yearbook for Traditional Music vol. 21 (1989). Marcus, Scott. “The Eastern Arab System of Melodic Modes in Theory and practice: A Case Study of Maqām Bayyātí: The Intervals of Modern Arab Music,” The Garland

47

Encyclopedia of World Music, The Middle East, Vol. 6, New York and London: Routledge, 2002. Marvin, W., handout, “Scales, Modes and Collections in Western Music,” from Shay, Loya, “The Verbunkos Idiom in Liszt’s Music of the Future: Historical Issues of Reception and New Cultural and Analytical Perspectives.” Ph. D. diss., King’s College, London, 2006. Runciman, Steven. Byzantine style and civilization. London: E. Arnold & co., 1933. Sallis, Friedemann. “La transformation d’un heritage: Bagatelle op. 6 no 2 de Bela Bartok et Invencio (1948) pour piano de Gyorgy Ligeti.” Revue de Musicologie, T. 83e, No. 2e (1997). Schoenberg, Arnold. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. Oxford: Alden Press, 1973. Signell, Karl. “Contemporary Turkish Makam Practice: The Abstract Level: Makam Theory.” The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, The Middle East, Vol. 6, New York and London: Routledge, 2002.

Somfai, László. “Invention, Form, Narrative in Béla Bartók’s Music.” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 44, Fasc. 3/4 (2003).

Somfai, László. “Nineteenth-Century Ideas Developed in Bartók's Piano Notation in the Years 1907-14,” 19th-Century Music, Vol. 11, No. 1, Special Issue: Resolutions II (Summer, 1987).

Suchoff, Benjamin. “Bartók’s Odyssey in Slovak Folk Music in Bartók Perspectives.” In Bartók perspectives: man, composer, and ethnomusicologist. London; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Szentkirályi, András, “Some aspects of Bartók’s Compositional Techniques.” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 20, Fasc. 1/4 (1978). Tillyard, H. J.W. “The Modes in Byzantine Music.” The Annual of the British School at Athens vol. 22 (1916/1917-1917/1918). Weissmann, John. “Bartók’s Piano Music.” Tempo, New Series, No. 14, Second Bartók Number (1949-1950). Wellesz, Egon. A History of Byzantine Music and Hymnography. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961.

Wilson, Paul. The Music of Béla Bartók. Yale University Press, 1992.

Wilson, Charles. “Octatonic.” Grove Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/.

48

Želinská, Magda Ferl and O’Connor, Edward J. P. “Czech Republic and Slovakia,” The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Europe,Vol. 8, New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2000.

![14 Bagatelles [Sz.38 ; BB 50 ; Op.6] · Title: 14 Bagatelles [Sz.38 ; BB 50 ; Op.6] Author: Bartók, Béla Subject: Public Domain Created Date: 10/20/2015 1:03:34 PM](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/611ad2d2f54f7438ac6cb06c/14-bagatelles-sz38-bb-50-op6-title-14-bagatelles-sz38-bb-50-op6.jpg)