Four Cultural Narratives for Managing Social-ecological ... · effectively to complexity. Keywords...

Transcript of Four Cultural Narratives for Managing Social-ecological ... · effectively to complexity. Keywords...

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01320-6

Four Cultural Narratives for Managing Social-ecological Complexityin Public Natural Resource Management

Nick A. Kirsop-Taylor 1● Adam P. Hejnowicz2 ● Karen Scott1

Received: 29 July 2019 / Accepted: 15 June 2020 / Published online: 7 July 2020© The Author(s) 2020

AbstractPublic Natural Resource Management (NRM) agencies operate in complex social-ecological domains. Thesecomplexities proliferate unpredictably therefore investigating and supporting the ability of public agencies to respondeffectively is increasingly important. However, understanding how public NRM agencies innovate and restructure tonegotiate the range of particular complexities they face is an under researched field. One particular conceptualisation ofthe social-ecological complexities facing NRM agencies that is of growing influence is the Water–Energy–Food (WEF)nexus. Yet, as a tool to frame and understand those complexities it has limitations. Specifically, it overlooks how NRMsrespond institutionally to these social-ecological complexities in the context of economic and organisational challenges—thus creating a gap in the literature. Current debates in public administration can be brought to bear here. Using anorganisational cultures approach, this paper reports on a case study with a national NRM agency to investigate how theyare attempting to transform institutionally to respond to complexity in challenging times. The research involved 12 eliteinterviews with senior leaders from Natural Resources Wales, (NRW) and investigated how cultural narratives are beingexplicitly and implicitly constructed and mobilised to this end. The research identified four distinct and sequential culturalnarratives: collaboration, communication, trust, and empowerment where each narrative supported the delivery ofdifferent dimensions of NRW’s social-ecological complexity mandate. Counter to the current managerialist approaches inpublic administration, these results suggest that the empowerment of expert bureaucrats is important in respondingeffectively to complexity.

Keywords Public agency ● Water–Energy–Food nexus ● Organisation ● Environment ● Culture ● Social-ecological complexity

Introduction

The significant majority of contemporary public organisa-tions operate in increasingly complex policy domains(Cairney et al. 2019). They must negotiate issues arisingfrom an array of social, economic, and ecological systemsand the interactions between them (Capra and Luisi 2016).

Complex systems such as these are highly diverse anddynamic by nature and characterised by properties such asnon-linearity, multiscalarity, feedbacks, tipping points,self-organisation, emergence, path dependency, adaptation,and uncertainty (Mobus and Kalton 2014). Consequently,because they are open to continual change and interact withother systems in unanticipated ways, complex systemsdisplay a high degree of unpredictability in their responsesto different drivers of change, which makes the task ofmanaging and governing them particularly demanding(Young 2017).

Public natural resource management (NRM) agencies, inparticular, face a difficult situation in managing multiplecomplexities (Kennedy and Quigley 1998; Belcher 2001;Koontz and Bodine 2008). First, like other organisations,they have to address organisational and operational com-plexities such as human resource and strategic developmentissues (Stacey 2015) and executive accountabilities (Tho-mann et al. 2017; Gravey et al. 2018; Schoenefeld and

* Nick A. [email protected]

1 Politics Department, University of Exeter, Penryn, Cornwall TR109FE, UK

2 Department of Biology, University of York, Wentworth WayYO10 5DD, UK

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01320-6) contains supplementarymaterial, which is available to authorised users.

1234

5678

90();,:

1234567890();,:

Jordan 2019). Second, like other public policy deliveryagencies, they have to tackle the complexities of policyimplementation and evaluation (Cairney et al. 2019) whilstunder the increasing pressure of political and economicchallenges and public expectations (Van Wart 2013; Tayloret al. 2019; National Audit Office 2018). Third, they havean additional layer of complexity to manage, in the form ofthe local and global sustainability challenges such as thoseposed by climate change, biodiversity loss, and land-usechange (e.g., Vince 2014; Steffen et al. 2018) that involvethe governance of complex social-ecological systems(Young 2017). In other words, interrelated environmentalsystems (e.g., marine, freshwater, and terrestrial ecosys-tems) and social systems (e.g., fisheries, agriculture, andforestry) (Cortner et al. 1998; Belcher 2001; Rammel et al.2007; Biggs et al. 2015; Young 2017).

These complexities proliferate unpredictably (at thetime of writing we are in the middle of the COVID-19pandemic), therefore investigating and supporting theability of public agencies to respond effectively isincreasingly important (Eppel and Rhodes 2018). How-ever, understanding how public NRM agencies innovateand restructure to negotiate the range of particular com-plexities they face is an under researched field. One par-ticular conceptualisation of the social-ecologicalcomplexities facing NRMs that is of growing influence isthe Water–Energy–Food (WEF) nexus. Yet, as a tool toframe and understand those complexities it has limita-tions. Specifically, it overlooks how NRMs respondinstitutionally to these complexities in the context ofeconomic and organisational challenges—thus creating agap in the literature. Current debates in public adminis-tration can be brought to bear here. Using an organisa-tional cultures approach, this paper reports on a case studywith a national NRM agency to investigate how they areattempting to transform institutionally to respond tocomplexity in challenging times. The research involvedsenior leaders from the Welsh national natural resourceagency—Natural Resources Wales (NRW), and focusseson how narratives are being explicitly and implicitlyconstructed to create a better organisational culture foraddressing complexity.

Responding to Complexity

Socio-ecological Complexity Frameworks

Understanding how organisations in general develop,operate, respond, and behave falls within the realm oforganisational studies and public administration (Stacey2015; Mullins 2016). Traditionally, public administrationscholarship has focused on organisational and operational

complexity and how increased challenges in servicedelivery often test the boundaries of political trust andbureaucratic autonomy and empowerment (Peters 2010:29–72; Thomann et al. 2017). Some scholars work from theperspective that rising complexity is best managed throughan increasingly professional bureaucracy who can makeautonomous expert situational decisions (Randolph 1995;Jamil et al. 2016; Kim and Fernandez 2015). Others arguefrom more managerial approaches that stricter account-abilities will endow bureaucrats with the tools necessary tomeet complex situations (e.g., audit cultures) (Halligan2007; Bovens et al. 2014; Schillermans, van Twist 2016).These differing perspectives reflect a wider debate aboutthe optimal modality for exercising control and ensuringaccountability in a bureaucracy (Peters 2010: 263–302).

More recently, there has been a broadening of scopebeyond these traditional perspectives, including an increasedfocus on how public NRMs govern in relation to the complexsocial-ecological systems under their remit (Barton et al.2010; Cilliers et al. 2013; Scott et al. 2015). A challenge thatdemands significant organisational and epistemic changefrom NRM agencies that are often sectorally organised, havedifficulty integrating social and natural science research, andremain at the whim of political economies and ideologies(Leck et al. 2015). The ecosystem approach, arising from theConvention on Biological Diversity (Jenkins et al. 2015),provided an early attempt to design a holistic, non-sectoral,and decentralised framework for integrated NRM based on asuite of fundamental principles (CBD 1998; Waylen et al.2015). Indeed, as we outline later, the ecosystem approachwas the foundation NRW adopted as an organisationalframing to navigate social-ecological complexity (Kirsop-Taylor and Hejnowicz 2020). In relation to natural resourceuse, scarcity, and management, the WEF nexus provides amore recent conceptual framing of social-ecological com-plexity that has garnered widespread policy traction (e.g.,Ringler et al. 2013; Scott et al. 2015). In many respects, theWEF nexus represents a contemporary social-ecologicalproblematic that previously saw efforts at reconciliationthrough the ecosystem approach (Leck et al. 2015; Bhaduriet al. 2015; Bizikova et al. 2013).

The WEF emphasises the complex interconnectionsbetween related biophysical systems (i.e., water, energy,and food), economic sectors, and policy domains as theyaffect human wellbeing and public welfare (Scott et al.2015). In that regard, the WEF provides an approach tothink systematically (so-called ‘nexus thinking’) about theinterdependencies underlying the functioning of social-ecological systems as well as a means to adopt multi-disciplinary systems perspectives (Ringler et al. 2013; Lecket al. 2015; Albrecht et al. 2018). Whilst the utilisation ofthe WEF as a particular framing of contemporary social-ecological challenges and a form of enquiry is not without

420 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

criticism (Wiegleb and Bruns 2018; Simpson and Jewitt2019) it resonates strongly with national policy-actors (Lecket al. 2015; Kirsop-Taylor and Hejnowicz 2020).

Hence, there is increasing emphasis on understandingcomplex social-ecological challenges through a WEF lens(Dodds and Bartram 2016). And, in particular, addressingthe challenges posed by interconnected and inter-dependent systems through a governance imperative(Weitz et al. 2017; Pahl-Wostl 2019). However, whilst theWEF is particularly useful as a means of examining bio-physical and cross-sectoral linkages within a system, inrelation to the issue of governance, the WEF is generallymore concerned with understanding the external role andactions of actors, such as NRM agencies, involved ingoverning social-ecological systems. As such, it offerslimited insights into how public NRM agencies shouldinternally reconcile emerging knowledges of andaccountabilities for social-ecological complexity along-side the economic, political, and operational challenges ofmaintaining funding, capacity, and capabilities. In addi-tion, the focus on system perspectives for organisationalchange management, which often goes hand in hand withthe WEF approach, has been criticised for its rationalistand reductionist approach (Tsoukas and Hatch 2001;Mowles et al. 2008; Simpson 2012). The tendency toframe organisations as a set of structures and agents wheredifferent levers can be pulled by change managersneglects the ‘day-to-day difficulties of trying to achievethings together, which is what it would mean to under-stand the process of organising as complex processes ofrelating’ (Mowles et al. 2008: 816; Simpson 2012). Inthese circumstances, which concern matters of internalorganisational dynamics and behavioural responses, it isnecessary to turn to other approaches that can be appliedto examine these issues, notably ‘organisational culture’(Peters 2010: 33–78).

Organisational Culture

There is a long-held view that the field of public adminis-tration should be considered as a form of culture science(e.g., Kulturwissenschaft—see Ringeling 2017) thatacknowledges the criticality of culture in shaping the publicsphere. Within this perspective public organisational cultureis a versatile and powerful theoretical framing for under-standing how public organisations manage and reconcilemultiple complexities (e.g., Parker and Bradley 2000; Parryand Proctor-Thomson 2010; Stanford 2010; Dartey-Baahet al. 2011; Lowndes and Roberts 2013). Culture exists atall levels of an organisation (Rez and Gati 2004) and inrelation to all issues and operations. Therefore, it is a usefullens to examine both broadly and deeply across multiplecomplex and intersecting domains within organisations.

Smircich (1983) reviewed the cultural turn in organisationaltheory and developed a five-pronged typology to categoriseunderstandings of organisational culture. In order to bringclarity to the field she linked ontological assumptions aboutculture and organisations from anthropology and organisa-tional theory respectively to create five views of organisa-tional culture: comparative management, corporate culture,organisational cognition, organisational symbolism,unconscious processes and organisation. This typologyallows researchers to interrogate their own ontologicalunderstandings of both ‘culture’ and ‘organisation’. In thispaper we broadly follow an organisational cognition modelwhere organisations are ‘systems of knowledge’ and cultureis a ‘system of shared cognitions’ where both systemsfunction in relation to ‘rules’ (Smircich 1983: 342). Thisresonates closely with Schein’s well-known definition oforganisational culture:

‘Culture can now be defined as (a) a pattern of basicassumptions, (b) invented, discovered, or developedby a given group, (c) as it learns to cope with itsproblems of external adaptation and internal integra-tion, (d) that has worked well enough to be consideredvalid and, therefore (e) is to be taught to new membersas the (f) correct way to perceive, think, and feel inrelation to those problems’. (Schein 1990, p 113)

Viewed in this manner, culture can help and encouragethe building of adaptivity and learning into public organi-sations (Costanza et al. 2015). Equally, organisationalcultures can help organisations transition away from toxicand intolerant practices (e.g., UK Police foundation 2018)towards cultures that tolerate mistakes as gateways tolearning and innovation (Betts and Holden 2004; Maria2003; Wodcka-Hyjek 2014; Olejarski et al. 2019). Theembedding of cultural values has also been identified to besignificant for business performance and management inthe face of external threats (Mansol et al. 2014), as well asmoderating internal organisational behavioural dynamicsand communication (Fischer and Smith 2006; Sagiv andSchwartz 2007).

Cultural Narratives

In recent decades there has been a steadily increasingacademic and policy interest in the potential power thatnarratives have in shaping, informing, and constructingorganisational cultures (Doolin 2003; Rowlinson et al.2014) for improving management (Browning 1991;Rhodes and Brown 2005), especially during periods ofchange and complexity (Bevir and Krupicka 2007;Strandberg and Vigsø 2016). Narratives have been shownto influence policy-making (e.g., Rhodes 2002; Stevens

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 421

2011; Lowndes 2016), constitute evidence (Epstein et al.2014), and shape policy cultures (e.g., Rhodes 2018).Organisational cultural narratives are the accounts of con-nected events and ideas that create a value-laden storyrelevant to a particular collections of individuals (Eisenberget al. 2001; Dettori 2011; Utoft 2020). They are the storiesthat help to build, change, and/or sustain shared meaningsin an organisation. Organisational cultural narratives canmanifest as crisp linear stories (Labov 1972; Hones 1998)or as mosaics of commonly associated collection of themes,aspirations, and observations that collectively account andconstruct the ‘associative determinants’ of narrative (as perFulford 1999).

Whilst certainly there is a critical counter-literatureabout narrative approaches to policy analysis (e.g., Jonesand McBeth 2010), the weight of scholarly activity in thisfield is focussed on how narrative approaches can offer animportant conceptual lens for understanding complexity incontemporary public agencies (Browning 1991; Lämsäand Sintonen 2006; Denning 2011; Pekar 2011; Morrell2006; Dalhstrom 2014; Vaara et al. 2016). The prolifera-tion of narrative approaches to organisational studies (andto a lesser degree public administration) literatures hasfacilitated an increasing sophistication in the methods ofnarrative analysis (e.g., Riessman 1993; Daiute andLightfoot 2004). In a systematic review Sahni and Sinha(2016) acknowledge the growing use of narrativeapproaches in organisational analysis but find that under-standing the role and significance of narratives withinorganisations is an under researched field. Furthermore,there are few contributions to this literature exploringnarratives for culture in public NRM agencies (e.g.,Dalhstrom 2014) who, as already noted, face a somewhatunique set of challenges.

We build on the view that narrative themes that influ-ence communications, organisational relationships,visions and values, and where leaders are deeply embed-ded in a process of change, can be the basis for new typesof organisational cultures to emerge (Simpson 2012;Stacey 2015). We therefore argue that cultural narrativesshould be a useful tool for constructing or re-aligningpublic organisational cultures towards the challenges ofgrappling with social-ecological complexities. As men-tioned above, popular system-based approaches forchange management in organisations dealing with uncer-tainty and complexity have limitations. Simpson (2012)argues that these approaches tend to characterise leader-ship as the key to success, usually framing this as a one-step removed change management ‘hero’ that can use theirexpertise of how systems work to guide the organisationthrough difficult transitions. Instead they argue for atten-tion to ‘the evolving dynamics of relating that make anorganisation what it is and how it is continuously

evolving’. That is a focus on the multiple everydayinteractions through language that build complex patternsof how an organisation thinks about itself, what it canachieve and how it should act. We explore this argumentthrough the case of NRW.

Case Study

NRM and the Challenges of the Current UK PoliticalLandscape

The United Kingdom (UK) offers an interesting setting forunderstanding complexity in public NRM agencies. Since2016 until the time of writing the discourse regardingagency capabilities for dealing with complexity hasfocused on their preparedness for ‘Brexit’ i.e., the UK’sdeparture from the European Union (EU) (e.g., Rutter andMcCrae 2016; Jessop 2017) and the requirement for newand replacement policies (see: UK Government’s IndustrialStrategy and 25-Year Environment Plan, both launched in2018). Moreover, when combined with systematic agencyunderfunding following 10 years of public sector austerity(National Audit Office 2018; Kirsop-Taylor et al. 2020)and uncertainties around post-Brexit ‘zombie legislation’(Burns and Carter 2018: 25) the current situation is parti-cularly challenging. These relatively ‘acute’ political andeconomic issues co-exist, and to some degree overshadow,the longer-term challenge of responding to and governingsocial-ecological complexity through remodelling howpublic NRM agencies function and behave (Kirsop-Taylorand Hejnowicz 2020).

History and Development of NRW

Within the UK Wales (see Fig. 1) is a (non-federal) nationthat operates under a reserved model of devolved govern-ance. This provides a degree of power for drafting legisla-tion, managing budgets, and setting rules within certainpolicy areas (Trench 2015) and the fully devolved ‘envir-onment’ policy-area. Following a widespread consultationand listening exercise the ‘Sustaining a Living Wales’ greenpaper (2012) articulated the challenges and vision fortwenty-first century NRM agency in Wales. This led to anambitious policy and institution-building agenda (St.Denny2016; Moon and Evans 2017) legislated through the Well-being of Future Generations Act (2015) and the Environ-ment (Wales) Act (2016).

The Environment (Wales) Act (2016) built on previousambitions1 by consolidating the three separate NRM

1 Especially the ‘Natural Resources Body for Wales EstablishmentOrder’ (2012)

422 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

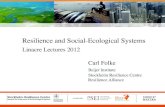

agencies (the Welsh Environment Agency, the CountrysideCouncil for Wales, and the Welsh Forestry Commission)into a unified national agency called NRW. Each of thelegacy agencies brought unique and differentiated activ-ities, processes, leadership styles, and cultures to the newagency (Waylen et al. 2015). The Environment (Wales) Act(2016) legislated for the design and adoption of a newmultiple-scale framework approach for national NRMmindful of the need to be better attuned to social-ecologicalcomplexity (as expressed in the consultation). This newapproach, called the ‘sustainable management of naturalresources’ (SMNR), was based upon instantiating anadapted form of the Malawi Principles of the ecosystemapproach from the Convention on Biological Diversity(Jenkins et al. 2015). Figure 2 highlights how NRWadapted the principles of an ecosystem approach into theirSMNR programme to meet the challenges posed bymanaging social-ecological complexity.

The principles of the SMNR approach are activated byNRW through a mix of discretionary and legislative powers,and executive expectations for implementation. The oper-ationalisation of these principles into the processes, archi-tectures, and activities of NRW is an evolving process oflearning, iteration, and adaptation.

Justification for Focusing on NRW

We selected NRW as a case study for a unique combi-nation of reasons, which together provide a useful andinteresting context in which to consider the role of culturalnarratives in building and facilitating organisational per-formance for complexity. First, they are a newly created

NRM organisation with a fresh organisational mandate.Second, they are currently explicitly transforming theirorganisational processes and functions to increase theircomplexity-capacity through the SMNR approach. Third,they are at a global first-mover disadvantage in imple-menting the SMNR approach. Fourth, they have a level ofpolitical patronage that has provided an enabling envir-onment to act and operate in an innovative way. More-over, they are operating within highly fiscally constrainedconditions as a result of public austerity. No UK publicNRM agency has faced such a significant disparity offunding between their initial business case (2013) andcurrent funding settlements as NRW (Reynolds andNinnes 2017). Finally, as noted by Waylen et al. (2015),organisational legacies, such as those from the threeagencies that constituted NRW, can create hurdles forintegration and innovation that require significant effort toovercome (Kirsop-Taylor and Hejnowicz 2020). In NRWthis has produced an environment ripe for structural,functional, and cultural innovation, as well as for con-tention, failure(s), and potential for learning.

Whilst the combination of justifications for case selc-tion evidence the uniqueness of NRW as a case, thechallenges it faces in terms of meeting socio-ecologicalcomplexities, change management, and building cultureare near universal to all other international NRM agen-cies. Therefore, this case-based research may help otherorganisations interested in such transformational aspira-tions and facing similar conditions and constraints, toanticipate and understand the opportunities and barriersinvolved in such processes from an organisational cul-tures perspective.

Fig. 1 Devolved Wales. Source:Business Wales 2019

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 423

Method

The focus of this research was on organisational culturalnarratives to create more effective responses to complex-ity. Similar research within large public agencies hashighlighted the value of the elite interview method forunderstanding complex organisational change manage-ment situations (Schara and Common 2016). Hochschild(2009) notes that fewer focussed interviews with respon-dents chosen for their detailed knowledge of a subject arelikely to yield richer data than other sampling approaches.Congruent with the normative rationale of elite case-basedresearch methods (Leuffen 2007; Luton 2010: 26-28;Boggards 2018) this small sample of elite managers were,in all probability, the only interviewees who could offersuch detailed insights into the phenomena under investi-gation. They were the ones tasked with, and responsiblefor, organisational change with a focus on changingorganisational culture and the organisational messagingaround that. This therefore necessitated a qualitativeresearch design with a small n sample of NRW organisa-tional elites (as per Luton 2010). The drawbacks of eliteinterviewing in terms of accessibility, positionality, andsmall n sample sizes (Harvey 2011) were offset by thebenefits of gaining first-hand accounts that were highlydetailed and nuanced.

Twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted withsenior managers within NRW. The primary contact within

NRW was established through an existing organisationalgatekeeper, which led to opportunity and snowball sam-pling. The interview sample comprised members of thesenior management team (n= 3), departmental heads (n=4), team leaders (n= 2), and senior members of the changemanagement team (n= 3). The sample included repre-sentatives from each of the three legacy agencies thatcomprised NRW, and from former members of WelshGovernment now working in NRW. A semi-structuredinterview method was employed that raised specific issueswhilst giving flexibility for elite-led dialogue (see Sup-porting Information). Empirical data were collectedbetween March and May 2018 through a combination ofSkype based interviews and telephone calls (see Support-ing Information). Interviews were recorded using the italkapplication and produced 10 h of data for transcription andanalysis. The data were analysed in NVivo 11 (QSRInternational 2018) against a partially pre-set, but emer-gent and iterative node framework based on parent nodessuch as ‘culture’, and child nodes such as ‘leadership’,‘legacies’, and ‘narratives of culture’ (see SupportingInformation).

Findings

Interviewees considered that the development of an effec-tive and appropriate culture was essential in meeting their

Fig. 2 From the Convention on Biological Diversity’s ecosystem approach to NRW’s principles of SMNR

424 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

legislative mandate to govern complex socio-ecologicalsystems. They expressed how the development of culture inNRW was a long-term project that incorporated bothexisting activities, as well as aspirational elements.

Organisational Culture and Leadership

Members of the senior team at NRW had a solid under-standing of what the SMNR principles were and how theyhelped them address social-ecological complexities. Seveninterviewees considered that whilst building the processes,forms and structures of the new joint agency was impor-tant, these would ‘only take NRW so far in its journey’(Int. 3) and all interviewees considered ‘culture’ to be acritical element in delivering the SMNR approach.

Most interviewees expressed the view that culturechange in the organisation was necessary to develop sharedunderstandings of SMNR and how to deliver it. This wasachievable through education, training, mentoring, coach-ing, collaboration, and communication:

‘We’ve got the training, bringing everybody up to acommon understanding of what it all means … We’llcontinue on that for the next couple of years as we gothrough the next phase of organisational design. Thereis a growing understanding that SMNR is the placewhere we could start to move away from our legacytraditions and build the new NRW traditions andculture. [Interview 5]

A majority of ten interviewees were critical of the notionthat organisational culture could be created in a top-downfashion. Some of these interviewees pointed towards theannual NRW ‘People surveys’ of 2015 and 2016 as evidenceof staff perceptions of the coercive nature of managementduring the formation stage of NRW. Nine intervieweesexpressed the view that the emergence of culture was anatural evolutionary process that was hard to create thoughimposition. However, there was some recognition that thepressing legislative mandate and political pressures for deli-vering the SMNR approach necessitated and legitimised top-down efforts at shaping or supporting culture, even if thisentailed a degree of coercion. Interviewee Four describedshaping culture ‘a nettle that we have to quickly grasp’ (Int.4) and Interviewee Seven noted:

‘it’s hard to build a culture for an organisation whichhas gone through rapid change, perhaps it needssomething stronger’

Three interviewees indicated that their new organisa-tional culture was a long-term project that would only

emerge through ‘a supportive environment’ as IntervieweeEight noted:

‘I think you can create the conditions to allow cultureto emerge, though I think you can’t necessarily shapeit through a hard process. It takes time, it’s a lot oftime, but you can certainly create the conditions foremergence’.

Unsurprisingly, several interviewees (n= 5) suggestedthat this ‘supportive environment’ had to be constructed atthe intersection of senior management leadership, and thevalues and behaviours of bureaucrats in NRW as a whole.Eight interviewees drew attention to the critical role of theagency leadership and leaders in taking responsibility forthe emergence of a culture to meet complexity. Six inter-viewees described the characteristics of leadership in termsof being able to communicate a consistent vision for theagency (n= 3). Two interviewees expressed that their rolewas to work to create an organisational sense of sharedmission and endeavour, or what Interviewee Nine called ‘asense of us’. As Interviewee Eight said:

‘I think leadership vision is critical. The troops … arequite attached to some of their old stuff and they see it[leadership for culture] as corporate nonsense. It takesa little while before you get used to it and you realise… that it’s not corporate nonsense. I think it’s criticalto support in the future of the organisation.’

Narratives for Culture Change

Interviewees offered a range of comments about narrativesfor cultural change. Seven interviewees noted a number ofdifferent and intersecting narratives about addressing social-ecological complexity through SMNR. Four of theseinterviewees further argued that these narratives were key tobuilding the culture that NRW needed to adopt if it wasgoing to meet its legislative mandate:

‘We have to be better at building the stories todemonstrate the difference that it [SMNR] makes. It’sabout the narrative… If we tell the stories in a moreengaging way, in a more live, real way … and the realdifference that the SMNR outcome will have, that isthe trick that we need to be able to pull off, I think’.[Interview 5]

‘It [culture change] does take a while and you have tobe really consistent in narrative. You have to

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 425

essentially keep saying the same thing for a longtime.’ [Interview 2]

‘It’s all about making sure people are doing the rightthing. A lot of this is our own narrative. Narrative ismuch more important, in my experience of workingaround the UK … I think [this] is the way to makesure that we get this metamorphosis or accept changeinto doing the right things … I don’t think that theway that people using some behavioural insights workis probably the way that we will make sure theorganisation is moving in the right direction.’[Interview 12]

Interviewees generally expressed a sense that the cultureof NRW would necessarily emerge from aspects of thelegacy cultures that comprised NRW, and from the activ-ities of the different parts of the organisation. Four of theinterviewees argued that there were widely understoodstories that constructed a sense of organisational identityand purpose attached to each of the legacy agencies, forexample, Interviewee Eight noted how:

‘the story of the Countryside Council for Wales being‘the advocates’, the Forestry Commission being ‘theproblem-solvers’, and the Welsh EnvironmentAgency being ‘the enforcers’; and that these shouldnever meet, or could never get on was quite powerful’.

Three interviewees commented on how narratives aboutorganisational identity that constructed the legacy agenciescould now act as barriers for working together to meetsocial-ecological complexity in the new agency, for exam-ple, Interviewee Four who noted how:

‘I think you will always have teams with a differentfocus. I wouldn’t say, I wouldn’t talk about them(cultures) emerging. I think it’s more a case of how dowe overcome the different cultures of the threeagencies so far and some people find that easier thanothers depending where you were in that agency.People in environment agency don’t have any troubleunderstanding the Countryside Council of Walesbiodiversity people.’

Narrative Themes for Creating NRW Culture

We found that the above discussions coalesced around fourinterconnected narrative themes about the identity andpurpose of the agency: communication, collaboration, trust,and empowerment. Whilst we review these themes

separately for clarity and expediency, they need to beappreciated in terms of their integration with one another,and it is important to note how these themes are inter-connected and variously interwoven through discussions ofcultural change. This can be illustrated in the aspirations ofInterviewee Eight below which was a fairly typical narra-tive for cultural change. This includes common themes ofchanging the structure of the organisation for greatercommunication and collaboration, and empoweringemployees to take risks and having trust they will not bepunished for this:

‘This is a question that I’m really keen to exploreactually is how do you evaluate how connected aperson or an organisation is? … It’s about how canyou really demonstrate that connectedness is whichI’m convinced is an [important]part of dealing withcomplexity … I would like there to be less structurearound teams and disciplines and more multi-workplace based teams, multi-disciplinary teams,and really keen to work horizontally across theorganisation with other parts of the business to trythose outcomes and also externally taking perhapsmore risks to get to those outcomes.’

Seven interviewees (in different ways) considered thatthese narrative themes might be key in forming an agency-level culture. Three other interviewees expressed how thesenarratives could help them deliver SMNR and meet theemerging social-ecological challenges identified. Respon-dents discussed various activities and responsibilities con-ducted by particular actors to help build and or deliver thesenarratives. These discussions covered what the leadershipsaid and did, and the behaviours and values of individualsand teams in the whole organisation. There was a differ-entiation between those narrative themes that were alreadycommonly adopted by the organisation, and those that theleadership aspired towards. Therefore, a narrative patternemerged about who NRW already were culturally, and whothey might yet become to meet SMNR. Figure 3 shows thefour distinct, yet connected, narratives that NRW eliteinterviewees considered were already evident, or aspiredtowards. We now discuss each of those narrative themes inturn acknowledging that the narrative themes were inter-woven with each other.

Communication

Interviewees conceptualised NRW becoming a commu-nicative organisation in terms of how they, the leadership,would have to communicate consistently about a unifiedcultural vision for the organisation. They expressed a hopethat this endeavour would feed into the wider evolving

426 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

value system of the organisation, which could be evidencedthrough staff behaviours inclined towards high levels ofcommunication in relation to problem-solving activities.Four Interviewees commented on how individual beha-viours would also need to reflect a culture of rapid, open,and free-flowing interdisciplinary communications. Inter-viewee Nine offered a comment that captured this:

‘we should be an organisation that talks to itself atevery level, with no barriers.’

This included a belief that communication would have tobe framed as a story about regularity of contact and co-creation of solutions to complexity through team discourse(Int. 8). This was part of a wider conversation about how thesuccess of this approach would be evidenced in the colla-borative and multi-team behaviours team members dis-played (n= 3). Interviewee One discussed this in terms of:

‘I know it’s not all about structures, but we are tryingto design structures that would make (communication)easier, we’re looking to bring (people) together in(local area-based) teams. …. then connect upwards toanother more national team to provide the overarchingpolicies and priorities for the whole of Wales …

culturally its in people’s behaviours and things likethat—we’ve still got a way to go.’

Collaboration

Interviewees considered their role in part was to foster asense of NRW being an intensely professional agency that

had a culture of continual learning and growing individualexpertise through strong joint working:

‘That is the biggest improvement that I have toachieve before I retire, that we’ve changed the cultureof the organisation in such a positive way that thewhole thing works as a system…We’ve got a holisticsystem within the organisation that enables everybodyto work together to the common good, if you like.’(Interview 6)

The interview discourse revealed how the narrative ofCollaboration is already evident in the actions and messagesof the NRW leadership:

‘If you look at the areas around collaboration andintegration, those principles there, that requires anopen culture of listening to others. It also requiresbusiness processes and system constraints that happenwith the organisation to allow those things to takeplace… [If] You have individual targets on perfor-mance. If you develop a very individually competitiveculture within an organisation, nobody’s ever going tocollaborate.’ [Interview 3]

This narrative has likely already been mobilised, asseen in values and behaviours of the NRW team—evi-denced in part by the findings of the 2015 and2016 ‘People surveys’, the process of delivering theNRW State of Natural Resources Report and ‘flatten-ing’ the structure of the organisation into place-basedarea teams (as shown in Kirsop-Taylor and Hejnowicz2020).

Fig. 3 Four cultural narratives of NRW

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 427

‘The second version of that is the area statements,which we’re doing at the moment. They are bringingmuch more staff together which creates the numbers.You can see that culture prodding out now betweenthe eco side of things.’ [Interview 4]

Four interviewees discussed how NRW needed to fostera staff-wide sense that collaboration was essential to solvingcomplex social-ecological challenges. Three of these inter-viewees considered that collaboration had to be more thanjust a behaviour that could be easily witnessed by com-munication practices, but a deep value that shaped alldecision-making and activity.

Trust

Interviewees considered Trust as a multi-directionaldynamic that infused all levels of NRW, and was mani-fested in three principal areas. It was primarily considered interms of how the leadership offered trust to the widerorganisation based on their skills, experiences, and capa-cities to make autonomous decisions free from direct andinstantaneous oversight. Others considered that the leader-ship characteristics would also have to reflect a sense ofTrust in the wider organisation to own and take responsi-bility for mistakes when they occur. For two other inter-viewees there was a third dimension to Trust, thatbureaucrats could trust the leadership to deliver a certaintyof vision. The story of Trust in NRW was considered as abidirectional and reciprocal relationship between bureau-crats and leadership—so as to loosen the overly prescribedbonds of accountability in the interests of increasing agility,responsiveness, and innovation. As Interviewee Elevendescribed:

‘we trust you, you trust us, and together we all actquickly, decisively, and innovate in response tocomplex problems.’

Trust was seen as multi-dimensional, and conceived interms of intra-organisational social trust and extra-organisational public trust, or, as Interviewee Ten sug-gested: ‘we trust each other, and the public should trust us’.Interviewees considered this would make NRW more resi-lient and adaptive to evolving WEF problems andaccountabilities, as well as more likely to be evidence-basedin their decision-making. Three interviewees expressed howNRW could not meet its legislated mandate to deliverSMNR without a culture of trust that circumvented (legacy)managerialism and associated cultures of blame and riskaversion. Critically, however, they considered that a narra-tive of Trust needed to be partnered with, and lead to, anarrative of Empowerment.

Empowerment

Four interviewees described how a key characteristic ofleadership in NRW should be to trust members of the teamto problem-solve complex issues. For two interviewees thiswas predicated upon a growing sense of bureaucratic pro-fessionalism and expertise for meeting complexity throughtraining, learning, and development. Four intervieweesperceived that this had to be coupled with a responsibility tohelp empower agency members to go beyond traditionalknowledges towards interdisciplinarity, for example Inter-viewee Nine who argued that:

‘we need to be helping colleagues feel comfortablewith going out of their intellectual comfort zone,which let’s be honest, is mostly based on what they’velearnt before!’

Three other interviewees also expressed how part of theirrole as leaders was to set a climate in which team membersfelt empowered to use their increased professionalism andexpertise to make informed expert decisions without fear ofblame. Two others argued how despite this being a difficultchallenge, due to the nature of UK civil service culture, thiswas a key job for them as leaders if they were going to trustindividuals to problem-solve complex issues.

Interviewees also described how the culture for addres-sing complexity would need to be actualised through thebehaviours that individual members of NRW team dis-played. This included the behaviours associated withincreased individual autonomy (n= 3). Coupled to thenotion of increased autonomy were comments (n= 3) aboutthe fear of failure that comes with increased autonomy. Twointerviewees related how they had to therefore build anarrative about an acceptance of failure, insomuch as failureis a gateway to rapid learning or what Interviewee Threedescribed as ‘failing fast’.

Interviewees also discussed the underlying values thatwould support these behaviours and characteristics of lea-dership. Two other interviewees expressed comments onhow re-framing failure as a positive outcome needed to bedeeply embedded in values that individuals held. Forexample, Interviewee Six argued that if this was not thecase ‘it wouldn’t work, people need to know that getting itwrong is OK sometimes’. The depth of internalised valueswas expressed by Interviewee Four when describing howthey wanted leaders to have a genuine ‘tolerance of mis-takes’, or Interviewee Nine (one of three interviewees) whoargued that the flipside of tolerance was responsibility, andthat ‘we need everyone to own their mistakes’. Twointerviewees noted that this would have to be linked toevidence of learning and improvement to assuage executiveand public expectations for accountability; though the

428 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

natural conflict this might cause with the narrative for Trustwas not discussed.

Discussion

The development of a certain ‘culture’ was an explicittheme in the aspirations of NRW leadership for the future.The interviewees’ conceptions of culture and their desire toexplicitly change/develop/work with certain cultures reso-nated well with Schein’s definition as set out in the intro-duction. Congruent with Parker and Bradley (2000), Parryand Proctor-Thomson (2010), Stanford (2010), and others(see: Schein 1990; Dartey-Baah et al. 2011; Lowndes andRoberts 2013) we found that interviewees considered cul-ture a critical component in building a successful publicNRM organisation. Interviewees considered that whilstleadership in public NRM agencies might play an importantrole in creating support structures for the development of aparticular culture (as per Parker and Bradley 2000), thedelivery and emergence of culture had to be a collaborativeendeavour across all layers of the organisation (Rez andGati 2004; Mowles et al. 2008). As noted in the Introduc-tion, the general paucity of literature on organisationalcultural narratives in public NRM agencies (and especiallythose seeking to tackle social-ecological challenges) madethe nature of Findings, and this Discussion, in many waysexploratory in nature. Narratives for cultural change wereexpressed in the form of sequential and associative structurein the discussed themes, aspirations, and expectations of thediscourse, as per Fulford’s (1999) account of organisationalnarratives.

Organisational Cultural Narratives for SociologicalComplexity

Of course, the question remains how will/can these narra-tives be practically employed to help NRW develop as anorganisation in a form attuned to handle social-ecologicalcomplexity? In Table 1, we outline how the four distinctivecultural narratives we identified can help facilitate andinstantiate specific SMNR principles (illustrated in Fig. 2),thus providing a pathway to enable NRW to meet its

statutory mandate and the challenges of governing complexsocial-ecological resource systems.

Our findings chime with Pekar (2011) in that inter-viewees considered that building characteristics, values, andbehaviours that would make NRW a communicative orga-nisation were perhaps one of easier endeavours. The valueof communication in social-ecological management activ-ities has similarly been well-documented (e.g., Johnson andKarlberg 2017) as has the value of communicative publicorganisations (e.g., Canel and Luoma-aho 2018). Inter-viewees expressed aspirations for NRW being a ‘commu-nicative organisation by nature’ (Int. 1) that moved beyondpure public relations-style communications to inculcating anarrative of ongoing open and honest dialogue with citizensand colleagues.

The narrative of Collaboration (both within NRW andbetween NRW and other agencies) was found to be themost important cultural narrative element for meetingaspects of social-ecological complexity, a finding supportedby the wider literature (e.g., Ringler et al. 2013; Leck et al.2015; Tanaguchi et al. 2017). Mobilising the narrative of acollaborative organisation has the potential to help NRWmeet their SMNR mandate of being participatory, recog-nising the multiple benefits from natural resource decision-making, and managing for the long-term. Though, ofcourse, simply mobilising a narrative in a superficial waywould not necessarily be the sole and automatic determinantof it happening. A theme which emerged from the findingswas a desire to have these narrative themes emerge fromand embedded in internalised values rather than a moresuperficial, top-down, abstract change management strat-egy. As such this chimes well with Stacey’s work andarguments about narrative and change processes in organi-sations (Stacey 2015; Mowles et al. 2008).

The discussions of narrative themes around trust andempowerment were interesting where it engaged with theaforementioned debate in public administration theoryabout the optimal modalities for ensuring accountability(Peters 2010: 263–302). There is a longstanding tension inhow public agencies and bureaucrats are held accountablebetween the degree of autonomy they enjoy to make pro-fessional decisions free from oversight; and the degree ofcontrol that their controlling authority holds them under(see: Romzek and Dubnick 1987). Excessive bureaucraticautonomy can lead to the emergence of unaccountable elitecadre, but in contrast limited bureaucratic autonomy canlead to inflexibility, risk aversion, and calcification (Leydenand Link 1993). Betts and Holden (2004) and Kittle (2017)have noted how limiting autonomy can precipitate bureau-cratic risk aversion which can, in due course, stymie risk-taking as an opportunity for organisational learning. Thereis long and well-developed public administration literaturehighlighting the criticality of trust within complex public

Table 1 Narratives facilitating SMNR

Narrative SMNR principles

Communication Adaptivity, participation, multiple benefits

Trust Resilience, adaptivity, evidence

Empowerment All

Collaboration Collaboration, participation, multiple benefits,long-term

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 429

organisations (Hindmoor 2002; Chen et al. 2013; Brown2018). In this case, elites considered that NRW are mobi-lising this narrative so that it might become an organisationthat exhibits trust between all members of the organisation.This trust will act as a facilitator for the connected culturalnarrative of empowerment.

Interviewees suggested that a cultural story of accep-tance towards reasonable failure should be promoted whereit supported NRW adopting the wider outcome of becom-ing a learning organisation (as per Maria 2003; Betts andHolden 2004; Jamil et al. 2016; Olejarski et al. 2019). Thiswas not described by interviewees as a ‘no blame culture’(see: Boviard and Quirk 2013; Wise 2018) such as thatseen in the UK Police Foundation (2018). Instead theintention expressed by interviewees was for a form ofcultural story that NRW would tell about itself in whichbureaucrats were empowered to make complex decisionsbased on their training and knowledge and blame for fail-ures could be apportioned insomuch as failure wasreframed as a learning exercise.

Interviewees did not consider the narrative of Empow-erment as being associated with meeting any specific aspectof SMNR (and more broadly social-ecological complexity).Rather, Empowerment was considered a critical determinantfor individual bureaucrats deploying their skills andexperiences to make complex decisions without fear ofover-management or excessive blame for mistakes. If NRWcould conceptualise itself as an organisation that trusts andempowers its staff to make decisions, take responsibility,fail fast, and that tolerates mistakes, then it might be able tomeet current and future social-ecological sustainabilitychallenges. This builds upon Kirsop-Taylor (2018) whosuggested that meeting today’s complex sustainabilitychallenges might require a reconceptualisation of publicmanagerialism (e.g., notions of public and executiveaccountability, and empowerment of bureaucrats) in NRMagencies, and that the failure to do this might result inagencies becoming unresponsive and increasingly ineffec-tive in meeting their respective mandates.

To the majority of interviewees there was a sequentialand layered nature to these narratives, with Trust andEmpowerment being built upon a foundation of Colla-boration and Communication. This sequential con-ceptualisation meant that some interviewees alreadyconsidered that NRW were exhibiting the narratives ofCollaboration and Communication, that a narrative of Trustwas starting to emerge, and that potentially in the future thismight lead to NRW telling itself the story of its Empow-erment. This means that NRW is more likely to meet theSMNR principles of Adaptivity, Collaboration, Participa-tion, Long-term, and Multiple benefits in the short term;whilst the principles of Adaptivity, Resilience, and Evi-dence might take longer (as the narratives of Trust and

Empowerment are mobilised). Thus, what was discerned inthis research offers a snapshot of a process of narrativeevolution within NRW towards a more conscious effort tocreate a culture to meet contemporary social-ecologicalchallenges.

Conclusion

In this paper we have offered an original empirical con-tribution to extant theorisation about the use of narratives inpublic NRM organisations. It advances current under-standings about how public NRM agencies can adaptreflexively to new and emerging complexity challengesthrough culture and narrative. The findings of our researchsuggest that the narratives of Communication, Collabora-tion, Trust and Empowerment might be utilised to mobilisethe cultural changes needed to meet complex configura-tions of social-ecological expectations within challengingpolitical and economic contexts. Collaboration was high-lighted to be the central cultural narrative for encouragingand developing a coherent organisational level of a com-mon and recognisable mutual culture. Our results alsodiscerned a social-ecological driven dynamic tensionbetween the narratives of Empowerment and Trust, andprevailing norms of bureaucratic accountability. This ten-sion suggests a loosening of the bonds of formal account-abilities in favour of greater informal accountabilitiesdriven by the need for bureaucrats to be empowered tomanage and solve social-ecological complexity at the streetlevel. This is an emancipatory aspiration that would makeprofessional bureaucrats more accountable to informalmandates of expertise and professionalism as opposed tostrict formal accountability.

Public NRM agencies internationally are facing thesesame challenges and the findings here from one leading-edge organisation have highlighted one approach and itsemergent impacts. The counter to this might suggest that theincreasing social-ecological complexity pressures might bemet through other innovations such as natural capitalapproaches or tighter and developed managerialism. Thismight precipitate a conflict of ideas about how best torespond to meeting social-ecological complexity—throughthe re-empowerment of bureaucrats or doubling-down onmanagerialism. To recapitulate, there is increasing emphasison formulating NRM social-ecological complexities andchallenges through a WEF lens, which has more recentlyfocused on the importance of advancing the considerationof the governance foundations of these interconnected andinterdependent systems. Consideration of social-ecologicalcomplexities through a WEF lens can be useful to articulate,in particular, the physical and cross-sectoral connectionswithin these systems, and for examining how actors operate

430 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

within these systems from an external perspective. How-ever, it offers very limited insights into how actors such aspublic NRM agencies should, at an institutional level andfrom an internal organisational dynamic, reconcile emer-ging knowledges, and accountabilities for complexity withthe economic, political, and operational challenges ofmaintaining funding, capacities, and capabilities. Systems-based approaches which have gained popularity with publicagencies to help them deal with complexity and changemanagement often fail to deal with the everyday realitiesand complexities of organisational culture. We stress theimportance of further research as vital to inform thesedebates and to understand how NRM agencies can respondeffectively to the increasing expectations on them in thechallenging political and economic context of the 21stcentury. Ultimately, the findings offer important insights forpublic administrators attempting to address social-ecological complexity within their agency; and for PublicAdministration scholars at the intersection of narrative,organisation, and culture.

Acknowledgements This paper was funded through a Research Fel-lowship from The Centre for the Evaluation of Complexity Across theNexus, a UK Economic and Social Research Council large centre [ES/N012550/1]. Research was conducted with the generous support ofNatural Resources Wales. The data that comprised this research isstored at the UK Data Service but safeguarded due to its sensitivenature.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts ofinterest.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard tojurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative CommonsAttribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, aslong as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and thesource, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate ifchanges were made. The images or other third party material in thisarticle are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unlessindicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is notincluded in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intendeduse is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitteduse, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyrightholder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Albrecht TR, Crootof A, Scott CA (2018) The Water–Energy–FoodNexus: a systematic review of methods for nexus assessment.Environ Res Lett 13(4):043002

Barton M, Ullah I, Bergin S (2010) Land use, water and Mediterraneanlandscapes: modelling long-term dynamics of complex socio-

ecological systems. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 368.https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0193

Belcher JM (2001) Turning the ship around: changing the policies andculture of a government agency to make ecosystem managementwork. Conserv Pract 2(4):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4629.2001.tb00018.x

Betts J, Holden R (2004) Organizational learning within the publicsector: avoiding the middle ground. Dev Learn Organ 18(1):18–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777280410510409

Bevir M, Krupicka B (2007) Police reform, governance, and democ-racy. In: O’Neill, M, Marks M, Singh A (eds) Police occupationalculture (Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance: 8). EmeraldGroup Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 153–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1521-6136(07)08006-

Bhaduri A, Ringler C, Dombrowski I, Mohtar R, Scheumann W(2015) Sustainability in the water–energy–food nexus. WaterInt 40(5–6):723–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2015.1096110

Biggs R, Rhode C, Archibald S, Kunene LM, Mutanga SS, Nkuna N,Ocholla PO, Phadima LJ (2015) Strategies for managing complexsocial-ecological systems in the face of uncertainty: examplesfrom South Africa and beyond. Ecol Soc 20(1):52. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07380-200152

Bizikova L, Dimple R, Swanson D, Verema HD, McCandless M(2013) The Water–Energy–Food Security Nexus: towards apractical planning and decision-support framework for landscapeinvestment and risk management. International SustainableDevelopment Institute. http://www.cilt.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/91/Bizikova%20et%20al.%20wef_nexus_2013%20IISD.pdf

Boggards M (2018) Case-based research on democratization. Demo-cratisation 26(1):61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1517255

Bovens M, Schillemans T, Goodin RE (eds) (2014) In: oxford hand-book of public accountability. Oxford Handbook of PublicAccountability, Oxford.

Boviard T, Quirk B (2013) Risk and resilience. University of Bir-mingham: Institute of Local Government Studies. Birmingham,UK

Brown R (2018) The citizen and trust in the (trustworthy) state. PublicPolicy & Administration. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076718811420

Browning LD (1991) Organisational narratives and organisationalstructure. J Organ Change Manag 4(3):59–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000001199

Burns C, Carter N (2018) Brexit and UK environmental policy andpolitics. Fr J Br Stud XX111:3. https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.2385

Business Wales (2019) Regions of Wales. https://businesswales.gov.wales/walesscreen/locations/regions-wales

Cairney P, Heikkila T, Wood M (2019) Policy making in a complexworld. Cambridge Elements. Cambridge University Press,Cambridge

Canel M-J, Luoma-aho (2018) Public sector communication: closinggaps between citizens and public organizations, 1st ed. Wiley,London

Capra F, Luisi PL (2016) The systems view of life: a unifying vision.Cambridge Uninversity Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511895555.

Chen C-A, Hsieh C-W, Chen D-Y (2013) Fostering public servicemotivation through workplace trust: evidence from public man-agers in Taiwan. Public Adm 92:4. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12042

Cilliers P, Biggs HC, Blignaut S, Choles AG, Hofmeyr JS, JewittGPW, Roux DJ (2013) Complexity, modeling, and naturalresource management. Ecol Soc 18(3):1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05382-180301

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 431

Convention for Biological Diversity (1998) The Ecosystem Approach.Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/ea-text-en.pdf

Cortner HJ, Wallace MG, Burke S, Moote MA (1998) Institutionsmatter: the need to address the institutional challenges of eco-system management. Landsc Urban Plan 40(1–3):159–166.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00108-4

Costanza D, Blacksmith N, Coats M, DeCostanza A (2015) The effectof adaptive organizational culture on long-term survival. J BusPsychol 31:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9420-y

Daiute C, Lightfoot C (2004) Narrative analysis: studying the devel-opment of individuals in society. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Dalhstrom MF (2014) Using narratives and storytelling to commu-nicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(4):13614–13620. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Dartey-Baah K, Amponsah-Tawiah K, Sekyere-Abankwa K (2011)Leadership and Organisational Culture: Relevance in PublicSector Organizations in Ghana. Bus Manag Rev 1(4):59–65

Denning S (2011) How do you change an organizational culture?Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/07/23/how-do-you-change-an-organizational-culture/#221584e839dc

Dettori G (2011) Supporting knowledge flow in web-based environ-ments by means of narrative. In: Technology and knowledge flow,pp 51–66 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-646-3.50003-4

Dodds F, Bartram J (eds) (2016) The water, food, energy and climateNexus: Challenges and an agenda for action. London: Routledge

Doolin B (2003) Narratives of change: discourse, technology andorganization. Organisation 10(4):751–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084030104002

Eisenberg EM, Riley P (2001) Organisational culture. In: Jablin FM,Putnam LL (eds) The new handbook of organisational commu-nication. Sage Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986243.n9

Eppel EA, Rhodes ML (2018) Complexity theory and public man-agement: a ‘becoming’ field. Public Manag Rev 20(7):949–959.https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1364414

Epstein D, Farina C, Josiah H (2014) The value of words: narrative asevidence in policy making. Evid Policy-Mak 10(2):243–258.https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13990325021128

Fischer R, Smith PB (2006) Who cares about justice? The moderatingeffect of values on the link between organisational justice andwork behaviour. Appl Psychol 55 4:541–562

Gravey V, Burns C, Carter N, Cowell R, Eckersley P, Farstad F,Jordan A, Moore B, Reid C (2018) Northern Ireland: challengesand opportunities for post-Brexit environmental governance. UKin a Changing Europe, London

Fulford R (1999) The triumph of narrative: storytelling in the age ofmass culture, 1st. Broadway Books, New York

Halligan J (2007) Accountability in australia: control, paradox, andcomplexity. Public Adm Q 31(3/4):453–479

Harvey W (2011) Strategies for conducting elite interviews. QualitativeRes 11(4):431–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111404329

Hindmoor A (2002) The importance of being trusted: transaction costsand policy network theory. Public Adm 76(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00089

Hochschild JL (2009) Conducting intensive interviews and eliteinterviews. Workshop on Interdisciplinary Standards for Sys-tematic Qualitative Research. https://scholar.harvard.edu/jlhochschild/publications/conducting-intensive-interviews-and-elite-interviews

Hones D (1998) Known in part: the transformational power of nar-rative inquiry. Qualitative Inq 4(2):225–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049800400205

Jamil D, Khoury G, Sahyoun H (2016) From bureaucratic organizationsto learning organizations: an evolutionary roadmap. Learn Organ13(4):337–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470610667724

Jenkins R, Drewett H, Bialynicki-Birula N, De’Ath R (2015) Deli-vering biodiversity through natural resource management. Report.Natural resources Wales board paper, Cardiff, NRW B 43.15

Jessop B (2017) The organic crisis of the british state: putting Brexit inits place. Globalisations 14(1):133–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1228783

Johnson O, Karlberg L (2017) Co-exploring the Water–Energy–FoodNexus: facilitating dialogue through participatory scenariobuilding. Front Environ Sci 5(Article):24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2017.00024

Jones MD, McBeth MK (2010) The narrative policy framework: clearenough to be wrong? Policy Stud J 38(2):329–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x

Kennedy JJ, Quigley TM (1998) Evolution of USDA Forest Serviceorganizational culture and adaptation issues in embracing anecosystem management paradigm. Landsc Urban Plan 40(1–3):113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00103-5

Kim SY, Fernandez S (2015) Employee empowerment and turnoverintention in the U.S. Federal Bureaucracy. Am Rev Public Adm47 1:4–22

Kirsop-Taylor N (2018) Street level influences affecting implementa-tion of an ecosystem approach within the North Devon UNESCObiosphere reserve. Dissertation, University of Exeter

Kirsop-Taylor N, Hejnowicz A (2020) Designing adhocratic publicagencies for 21st century nexus complexity: the case of NaturalResources Wales. Public Policy and Administration. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076720921444

Kirsop-Taylor N, Russel D, Winter M (2020) The contours of stateretreat from collaborative environmental governance underausterity. Sustainability 12(7):2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761

Kittle N (2017) Succeed fast by failing faster government innovatorsnetwork. https://www.innovations.harvard.edu/blog/succeed-fast-failing-faster

Koontz TM, Bodine J (2008) Implementing ecosystem management inpublic agencies: lessons from the US Bureau of Land Manage-ment and the Forest Service. Conserv Biol 22(1):60–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00860.x

Labov W (1972) Sociolinguistic patterns. University of PennsylvaniaPress, Philadelphia (PA)

Lämsä A-M, Sintonen T (2006) A narrative approach for organiza-tional learning in a diverse organisation. J Workplace Learn 18(2):106–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610647818

Leck H, Conway D, Bradshaw M, Rees J (2015) Tracing theWater–Energy–Food Nexus: description, theory and practice.Geogr Compass 9(8):445–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12222

Leuffen D (2007) Case selection and selection bias in small-n research.In: Gschend T, Schimmelfennig F (eds) Research design inpolitical science, 1st ed. Palgrave MacMillan, London

Leyden DP, Link AN (1993) Privatization, bureaucracy, and riskaversion. Public Choice 76(3):199–123

Luton L (2010) Qualitative research approaches for public adminis-tration. Sharpe, London

Lowndes V, Roberts M (2013) Why institutions matter: the newinstitutionalism in political science. Red Globe Press, London

Lowndes V (2016) Storytelling and narrative in policymaking. In:Stoker G, Evans M (eds) Evidence based policymaking in thesocial sciences: methods that matter. Policy Press, Bristol

Mansol NH, Alwi NHM, Ismail W (2014) Embedding OrganisationalCulture Values Towards Succesful Business Continuity Man-agement Implementation. In Proceedings of the 6th InternationalConference on Information Technology and Multimedia, Putra-jaya - Malaysia. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Embedding-organizational-culture-values-towards-Mansol-Alwi/03537e866e419562867d694d570b09c320d58e3b

432 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434

Maria R-F (2003) Innovation and organizational learning culture in theMalaysian Public Sector. Adv Dev Hum Resour 5(2):205–214.https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422303005002008

Mobus GE, Kalton MC (eds) (2014) Principles of systems science(understanding complex systems). Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1920-8

Moon D, Evans T (2017) Welsh devolution and the problem of leg-islative competence. Br Politics 12(3):335–360. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-016-0043-3

Morrell K (2006) Policy as narrative: new labour’s reform of thenational health service. Public Adm 84(2):367–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00006.x

Mowles C, Stacey R, Griffin D (2008) What contribution can insightsfrom the complexity sciences make to the theory and practice ofdevelopment management? J Int Dev 20:804–820

Mullins LJ (2016) Management and organisational behaviour, 11thedn. Pearson, London

National Audit Office (2018) Implementing the UK’s Exit from theEuropean Union: The Department for Environment, Food &Rural Affairs. National Audit Office. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/implementing-the-uks-exit-from-the-european-union-the-department-for-environment-food-rural-affairs/

Olejarski AM, Potter M, Morrison RL (2019) Organizationallearning in the public sector: culture, politics, and performance.Public Integr 21(1):69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2018.1445411

Pahl-Wostl C (2019) Governance of the Water–Energy–Food SecurityNexus: a multi-level coordination challenge. Environ Sci Policy92:356–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.017

Parker R, Bradley L (2000) Organisational culture in the public sector:evidence from six organisations. Int J Public Sect Manag 3(2):125–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550010338773

Parry K, Proctor-Thomson S (2010) Leadership, culture and perfor-mance: the case of the New Zealand public sector. J ChangeManag 3 4:376–399

Pekar T (2011) The Benefits of Building a Narrative Organisation.Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_benefits_of_building_a_narrative_organization#

Peters G (2010) Politics and the Bureaucracy: An Introduction toComparitive Public Administration. London: Routledge

Police Foundation (2018) How do we move from a blame culture to alearning culture in policing? KPMG, London

QSR International. NVivo 11 (mac). Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-dataanalysis-software/about/nvivo

Rammel C, Stagl S, Wilfing H (2007) Managing complex adaptivesystems — A co-evolutionary perspective on natural resourcemanagement. Ecol Econ 631:9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.12.014

Randolph WA (1995) Navigating the journey to empowerment.Organisational Dyn 23(4):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(95)90014-4

Reynolds N, Ninnes R (2017) Creation of natural resources wales—realising the Business Case benefits. Natural Resources Wales,Cardiff. cdn.naturalresources.wales/media/684421/creation-of-natural-resources-wales-realising-the-benefits.pdf

Rez M, Gati E (2004) A dynamic, multi-level model of culture: fromthe micro level of the individual to the macro level of a globalculture. Appl Psychol 53(4):583–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00190.x

Ringeling, A (2017) Public administration as a study of the publicsphere: a normative view, Eleven International Publishing, TheHague, Netherlands

Rhodes C, Brown AD (2005) Narrative, organizations and research.Int J Manag Rev 7:167–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00112.x

Rhodes RAW (2002) The governance narrative: key findings andlessons from the ERC’s Whitehall Programme. Public Adm 78(2):345–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00209

Rhodes RAW (2018) Narrative policy analysis: cases in decentredpolicy. Palgrave MacMillan, London

Riessman CK (1993) Narrative analysis. Qualitative Research Meth-ods Series 30. SAGE, London

Ringler C, Bhaduri A, Lawford R (2013) The nexus across water,energy, land and food (WELF): potential for improved resourceuse efficiency? Curr Opin Sustainability 5(6):617–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.002

Romzek B, Dubnick MJ (1987) Accountability in the Public Sector:Lessons from the Challenges Trajedy. Public Adm Rev 47(3):227–238

Rowlinson M, Casey A, Hansen PH, Mills AJ (2014) Narratives andmemory in organizations. Organization 21(4):441–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414527256

Rutter J, McCrae J (2016) Brexit: organising Whitehall to deliver.Briefing paper. Institute for Government, London. www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Brexit%20Briefing%20paper%20web.pdf

Sagiv L, Schwartz SH (2007) Cultural values in organisations: insightsfor Europe. European. J Int Manag 1 3:176–190

Sahni S, Sinha C (2016) Systematic literature review on narratives inorganizations: research issues and avenues for future research.Vision 20(4):368–379

Schara T, Common R (2016) Leadership and elite interviews:researching the challenges of EU rail integration in a singleEuropean Rail Area. Int J Public Leadersh 12(1):32–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-03-2016-0007

Schein E (1990) Organizational culture. Am Psychologist 452:109–119

Schillermans T, van Twist M (2016) Coping with complexity: internalaudit and complex governance. Public Perform Manag Rev 40(2):257–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2016.1197133

Schoenefeld J, Jordan A (2019) Environmental policy evaluation inthe EU: between learning, accountability, and political oppor-tunities? Environ Politics 28(2):365–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549782

Scott C, Kurian M, Wescoat J (2015) The Water–Energy–Food Nexus:enhancing adaptive capacity to complex global challenges. In:Kurian M, Ardakanian R (eds) Governing the Nexus, 1st ed.Springer, London

Simpson P (2012) Complexity and change management: analysingchurch leaders’ narratives. J Organ Change Manag 25(2):283–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811211213955

Simpson G, Jewitt G (2019) The development of theWater–Energy–Food Nexus as a framework for achievingresource security: a review. Front Environ Sci 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00008

Smircich L (1983) Concepts Cult Organ Anal, Adm Sci Q ume: 28(Issue: 3):339–358

St. Denny E (2016) What does it mean for policy to be ‘made inWales?’. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/what-does-it-mean-for-public-policy-to-be-made-in-wales/

Stacey RD (2015) Strategic management and organisational dynamics,7th ed. Pearson Education, London

Stanford N (2010) Organisational culture: getting it right. EconomistBooks, London

Steffen W, Rockström J, Richardson K et al. (2018) Trajectories of theearth system in the anthropocene. PNAS 115(33):8252–8259.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

Stevens A (2011) Telling policy stories: an ethnographic study of theuse of evidence in policy-making in the UK. J Soc Policy 40(2):237–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279410000723

Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434 433

Strandberg JM, Vigsø O (2016) Internal crisis communication an employeeperspective on narrative, culture, and sensemaking. Corp Commun:Int J 21(1):89–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-11-2014-0083

Tanaguchi M, Endo A, Gurdak J, Swarzenski P (2017)Water–Energy–Food Nexus in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hydrol:Regional Stud 11:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2017.06.004

Taylor A, Dessai S, Bruine W (2019) Public priorities and expectationsof climate change impacts in the United Kingdom. J Risk Res 22(2):150–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1351479

Thomann E, Hupe P, Sager F (2017) Serving many masters: publicaccountability in private policy implementation. Governance 31(2):299–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12297

Trench A (2015) Delivering a reserved powers model of devolutionfor Wales. www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/publications/tabs/unit-publications/165

Tsoukas H, Hatch J (2001) Complex thinking, complex practice: thecase for a narrative approach to organizational complexity. HumRelat 54(8):979–1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701548001

Utoft EA (2020) Exploring linkages between organisational cultureand gender equality work—an ethnography of a multinationalengineering company. Eval Program Plan 79:101791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101791

Vaara E, Soneschien S, Boje D (2016) Narratives as sources of sta-bility and change in organizations: approaches and directions forfuture research. Acad Manag Ann 10:495–560. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1120963

Van Wart M (2013) Changing public sector values. Routledge,London

Vince G (2014) Adventures in the anthropocene: a journey to the heartof the planet we made. Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis

Waylen K, Blackstock K, Holstead K (2015) How does legacycreate sticking points for environmental management?Insights from challenges to implementation of the ecosystemapproach. Ecol Soc 20(2):21. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07594-200221

Weitz N, Strambo C, Kemp-Benedict E, Nilsson M (2017) Closing thegovernance gaps in the Water–Energy–Food Nexus: insightsfrom integrative governance. Glob Environ Change 45:165–173.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.06.006

Wiegleb V, Bruns A (2018) What Is Driving the Water-Energy-FoodNexus? Discourses, Knowledge, and Politics of an EmergingResource Governance Concept. Front Environ Sci 6(128). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00128

Wise J (2018) Survey of UK doctors highlights blame culture withinthe NHS. British Medical Journal 362. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4001

Wodcka-Hyjek A (2014) A learning public organization as the con-dition for innovations adaptation. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 10(24):40–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.857

Young OR (2017) Governing complex systems: social capital forthe anthropocene (Earth System Governance). MIT Press,Cambridge

434 Environmental Management (2020) 66:419–434