FORMORETHANHALFACENTURY, they have served as guards ...366thspsk-9.com/Misc/parade.pdf · COVER...

Transcript of FORMORETHANHALFACENTURY, they have served as guards ...366thspsk-9.com/Misc/parade.pdf · COVER...

February 1918, he roused a sleepingsergeant to warn of a gas attack, givingsoldiers time to don masks. On sentryduty, he clamped his teeth into a Germaninfiltrator, who was then captured. Inno-man’s-land he was wounded by

shrapnel but recovered to join the 102ndin battles at Chateau Thierry, the Marneand the Meuse-Argonne. The men ofthe 102nd hung a Victory Medal fromhis collar. French women fashioned ablanket for “The Hero Dog” to wear,and with each offensive, more medalswere pinned to Stubby’s cloak.

After 17 battles, Stubby sailed backto America, where hisvictorious command-er, Gen. John “BlackJack” Pershing, award-ed the dog a specialgold medal. As a lifemember of both the American Legion andthe Red Cross, Stubbymarched in paradesacross the countryand met PresidentsWilson, Harding andCoolidge. When oldage felled the warriorin 1926, his body waspreserved and dis-played for 30 years atthe Red Cross Muse-um in Washington,D.C. But time woreaway at his skin, his

fur and the memory of his countrymen:Stubby moldered thereafter in a packingcrate in a Smithsonian storeroom. Still,his legacy endured in the thousands oflives saved by dogs in subsequent Amer-ican wars.

PAGE 4 • APRIL 1, 2001 • PARADE MAGAZINE

FTER MORE THAN A half-century of ser-vice—and despite arecord of document-ed heroism and Amer-ican lives saved—one

group of U.S. veterans has been accord-ed no honor in our nation’s capital.

Thousands of dogs who served withthe Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines andCoast Guard have been denied a mon-ument in Washington, D.C. Last year,their fellow veterans sought permissionto commemorate their service with asingle tree at Arlington National Cem-etery. That request was denied.

Most Americans know nothing of therecord of their war dogs—to say noth-ing of the final chapter of their saga,which some consider a stain on thehonor of the U.S. armed forces.

LIKE SO MANY GREAT Ameri-can stories, the history of our war dogsbegan with a small act of rebellion. InWorld War I, the British, Belgian, Ital-ian and French armies trained thousandsof dogs as sentries and messengers orto find and comfort wounded men onthe battlefield. On the other side, theGermans deployed 7000 dogs, withthousands more in reserve. (The famousRin Tin Tin was a German dog foundin a trench after an attack.) But the U.S.Army had no such program.

Nevertheless, a small, stray bull ter-rier named Stubby was adopted by the

102nd Infantry and smuggled aboard atroop ship to France. There, he wouldprove his mettle.

Stubby carried messages under fire,sought out the wounded and stayed withthem until help arrived. One night in

FOR MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY, they have served as guards, scouts, messengers and fighters during wartime.Yet there is no national memorial to remember our country’s war dogs. YOU CAN HELP.

B Y R I C H A R D B E N C R A M E R

VIETNAM: Army Spec. 4Charlie Cargo andWolf. The dog oncesaved Cargo’s lifeby biting himbefore he could setoff a booby trap. “I learned never tosecond-guessWolf,” says Cargo,who still has a bitescar on his hand.

A

They Were HEROES TOO

Cou

rtes

y of

Cha

rlie

Car

go

HELP HONOR K-9 VALORThe Vietnam Dog HandlerAssociation, a veterans group,is spearheading the drive tohonor America’s war dogswith a national memorial. To learn more or to make adonation, swipe the cue belowor visit www.vdhaonline.orgon the Web; you can also write to the National War DogMemorial Fund, c/o VietnamDog Handler Association,P.O. Box 5658, Dept. P,Oceanside, Calif. 92052-5658.

C 62 00 00 00 00 53 76

COVER PHOTOGRAPH FROM ANIMAL IMAGE

PARADE MAGAZINE • APRIL 1, 2001 • PAGE 5

WITHIN A MONTH after the attackon Pearl Harbor in December 1941,America’s canine trainers had estab-lished DFD—Dogs for Defense—andsoon began to work with the CoastGuard (saboteurs were expected to sur-face from submarines at any moment).By April 1942, dogs were serving assentries at Army depots and defenseplants. That summer, Secretary of WarHenry Stimson directed all branches ofthe service to explore the use of dogs,and the rush was on—for dogs to workas guards, medics, MPs, mine-sniffers,scouts, messengers, even tactical fight-ers; for dogs to walk patrol in Pacificjungles and mush supplies across Arc-tic ice. One year after America went towar, the military announced that theArmy, Navy, Marines and Coast Guardwould need about 125,000 dogs.

Canine combatants were recruited justas men were. But no draft was required.Tens of thousands of dogs were shippedvoluntarily to DFD centers, where theywere measured, evaluated, examinedand trained for duty. A few owners mayhave fobbed off bad pets, but most werepatriots who sent a dog off to war just asthey would a son. (That spirit posed anunexpected problem. Mail poured in,

approaching on a road. Rowell and hiscomrades took them all as prisoners—and Chips became a hero.

Chips was awarded the Silver Star forvalor and a Purple Heart for his wounds.U.S. papers exulted: Yank Hero DogTakes 14 Italos! Then the trouble began.The commander of the Order of the Pur-ple Heart complained to President Roo-sevelt that bestowing the medal on a dogdemeaned all the men who had receivedPurple Hearts. Both of Chips’ medalswere revoked, and no U.S. war dogwould ever again win official decoration.

The only recognition Chips couldkeep, when he was returned to the Statesand his owner, was his honorable dis-charge. Still, that was better than dogsin later wars. When the Pentagon learnedhow much trouble it took to retrain adog for civilian life, there would be nomore discharges. After 1946, any dogwho “enlisted” was a war dog for life.

BY THE TIME American soldiersscrambled to save South Korea in 1950,the World Wars’canine lessons had beenforgotten. The entire U.S. military hadonly one platoon of true war dogs—theArmy’s 26th Scout Dog Platoon, which

The militaryrecognized thedogs’ “unbrokenrecord of faithfuland gallant performance.”

WORLD WAR II: Andy, aDoberman pinscher (picturedwith an unidentified Marine),saved a tank platoon pinneddown on the island ofBougainville by flushingJapanese machine-gunnersfrom their nest.

Len And Rin: A Boy And His Dog Go To War

AFEW MONTHS AFTER PEARL HARBOR, Len Brescia of Watertown, Mass., heard that the armed forces needed

dogs. Len, 17, was certain his friendly pup,a German shepherd mutt named Rin, couldmake the grade as a guard dog. “So I got intouch, and they sent a gentleman out to ourhouse, and he asked me to bring Rin out ona leash.” Then he pulled out a starter’s pis-tol and fired a shot in the air. “Rin turned onhim right away—and if I hadn’t had thatleash, he would have gone for the guy whomade that noise. And, of course, that’sexactly what they wanted to see.”

Rin “enlisted” in 1942. Len wasn’t farbehind—by 1943 he’d joined the Navy. (Later,

asking for news of K-9 recruits—orbearing cards, biscuits or bones.)

The only news the owners could getcame from handlers in the field and occa-sionally in newspaper stories. One suchstory concerned Chips, a mixed-breeddonated from Pleasantville, N.Y., andshipped overseas with the 30th Infantry.With his handler, Pvt. John P. Rowell,Chips took part in the July 1943 invasionof Sicily. Near Licata, on the island’ssouthern coast, Rowell and Chipsworked inland in the light before dawn. continued

About 300 yards from the beach, amachine gun disguised with thatchopened fire on Rowell. Chips broke freeand streaked for the gunners’ pillbox.Soon, an Italian soldier emerged, withChips biting at his arms and throat.Three more Italian soldiers followedwith hands up. Chips suffered a scalpwound and powder burns—proof thatthe Italians had tried to kill him—butthe dog prevailed. After being treatedand returned to duty that same night,Chips discovered 10 Italian soldiers

LEN BRESCIAwith a photoof his dog, Rin,and Rin’s Armydischargecertificate.Brescia,himself a Navyveteran ofWorld War II,volunteeredhis dog forserviceshortly afterJapan’sDecember 1941attack onPearl Harbor.

Ani

mal

Im

age

Ed

Qui

nn

Len learned that if they’d enlisted togeth-er, he and his dog might have served togeth-er.) Both were remembered in their home-town—Len with a red, white and blue starin his folks’ window, Rin with a red, whiteand blue paw print.

Len did his duty in the Pacific, winding upin a motor pool on Okinawa. Rin did his ser-vice with the Army—no one would saywhere. And both made it through to thewar’s end. In fact, Rin lived into the 1950swith Brescia’s family in Watertown. Even inold age, Rin still served—as baby-sitter.“We’d sit the baby in the carriage out in thesun, and Rin would sit or lie down next toit. No one was getting near that carriage.”

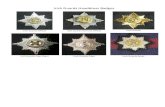

NEMO

Vietnam hero:Despite losingan eye togunfire, Nemo,an Air Forcesentry, threwhimself on fourViet Cong tosave his handlerin 1966. Bothsurvived.

CHIPS

The call of duty:Army dog Chipsattacked apillbox on Sicilyin 1943, takingfour prisoners.He earned aSilver Star anda Purple Heart,both laterrevoked.

STUBBY

The originalwar dog: The102nd Infantry’sStubby was in 17battles duringWorld War I,saving U.S. lives,capturingGermans andcomforting thewounded.

America’s Best FriendsDuring Times Of WarAlthough their exploits arelargely unknown, tens ofthousands of dogs haveserved this country faithfully since World War I.Here’s a brief look at threecanine heroes.

Ani

mal

Im

age

Nat

iona

l Arc

hive

s

Bet

tman

n/C

orbi

s

shipped out in June 1951 and compiled a record ofdistinction. The fear the animals created among Chi-nese and North Korean troops was evidenced by thepropaganda they blared through loudspeakers at night:“Yankee! Take your dog and go home!”

The war dogs and their handlers spent almost twoyears in Korea, patrolling at night, when no other unitcould match their success. As cease-fire negotiationsbegan, the Army recognized that the dogs’ “unbrokenrecord of faithful and gallant performance...savedcountless casualties.” Still, by the time the last dogcame home from Korea, nuclear war was the big threat.The last training center, at Fort Carson, Colo., wasshut down in 1957, and the Army abandoned war dogs.

Vietnam changed all that. As the war escalated in the1960s, first the Air Force and then the Army employedhundreds of canine sentries to guard against Viet Conginfiltration. Marine and Armyscout dogs led patrols throughjungles, rice paddies and pied-mont hills. Once Americantroops discovered that they sel-dom lost a man while a dogwalked along, there were neverenough of the animals. Even-tually, 4000 war dogs wouldserve and protect our troops.

“When we were sick, theywould comfort us, and whenwe were injured, they protect-ed us,” said a former Vietnamdog handler, Tom Mitchell ofSan Diego. “They didn’t carehow much money we had orwhat color our skin was. Heck,they didn’t even care if wewere good soldiers. Theyloved us unconditionally. Andwe loved them. Still do.”

Stories of the bond betweenhuman and canine soldiers aretold on Web sites devoted tothe war dogs. Along with theanimals’heroics, the sites haveanother theme in common: out-rage at the fate of those dogswho laid down their lives forAmerican troops.

When the U.S. pulled outof Vietnam, the Pentagon con-sidered dogs “war equip-ment”—and ordered them“abandoned in place.” AsMichael Lemish, official his-torian for the Vietnam DogHandler Association (VDHA),notes: “Officially, no oneknows what happened to

is picking up steam. In 1999, a documentary about wardogs aired on the Discovery Channel. The first unofficialU.S. memorial was a sculpture unveiled last February atMarch Field Air Museum in Riverside, Calif. An iden-tical sculpture—man and dog on patrol—was dedicated

in October at Georgia’s FortBenning Infantry Museum.And a new photo book aboutwar dogs is being produced byOpen Books of Annapolis, Md.

But as yet there is no memo-rial that will serve for thenation, as the war dogs did.

Veteran dog handlers col-lected 100,000 signatures butwere turned down for a postagestamp. (Bugs Bunny madeit—the war dogs did not.) TheSmithsonian is now renovat-ing the National Museum ofAmerican History, but thereare no plans to mention wardogs in the new Armed ForcesHistory Hall. (They even sentStubby packing to a NationalGuard armory in Connecticut.)And when the veteran dog han-dlers applied to plant a tree atArlington National Cemetery,they were denied. Says JohnBurnam, the president of theVDHA: “We wanted it to bea team memorial—for the wardogs and the men who servedwith them. But they just won’tdo it. The bias is simply ‘Hu-mans Only.’They didn’t wantto let us inside the gate or any-where near it.”

them—the only questions that really remain are howmany were killed, eaten or just simply starved to death.”

THE SHAME OF THAT CHAPTER in the wardogs’history fuels the drive for recognition—a drive that

“They didn’t care how muchmoney we had or what thecolor of our skin was. Theyloved us unconditionally.”

THEY WERE HEROES TOO/continued

P

AP

/Wid

e W

orld

ANOTHER SCOUT DOGnamed Wolf—one of about 4000 canines whoserved with U.S. forces in Vietnam—leads hishandler through a ricepaddy near Saigon in 1968.

Pulitzer Prize-winning jour-nalist Richard Ben Cramer isthe author of the best-sellingbiography “Joe DiMaggio:The Hero’s Life” (Simon &Schuster).