FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

Transcript of FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 1/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

1

FORES POLICY BRIEF

Carbon Taxes to Solve the

Sovereign Debt Crisis

By Ulrika Stavlöt1

As many governments face the

challenge of implementingnecessary fiscal consolidation

while avoiding slowing down the

recovery, carbon pricing is an

attractive alternative. It could

finance substantial parts of the

fiscal consolidation with fewer

distortions than most other forms

of taxation, while the tax burden is

shared with fossil fuel producers.

Reductions in debt and in carbon

emissions (and carbon tax revenues)

may move in parallel.

1Ulrika Stavlöt is the research director atFORES

The global financial crisis and the following

economic collapse resulted in a sharpdeterioration of public finances in most

industrialised countries. According to the

EEAG (2011) the debt-to-GDP ratio in the

G7 countries is expected to increase by 40

percentage points by 2015 as compared to

the pre-crisis level in 2007. Part of the

increase in deficits can be attributed to

automatic stabilisers, in particular to a

drop in tax revenues and, to a lesser degree,

to increases in public spending. Part can be

attributed to fiscal stimulus packages like

Keynesian recovery programmes and

generous bank rescue operations.

Double need for urgent action

The recent years economic and political

discussion has been centred on how the

sovereign debt crisis in Europe and how the

unsustainable fiscal developments in the

United States will evolve. Although there is

a strong consensus on the need to

undertake strong measures to reduce

deficits and stabilise public debt, fiscal

consolidation in 2011 is still expected to be

modest in advanced economies. As a result,

the adjustment required to restore debt

ratios to prudent debt levels remains

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 2/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

2

substantial, especially in advanced

economies (IMF, 2011a).

Parallel to the policy debate on the content

and intensity of fiscal correction measures

the international debate on the problem of

global warming has resurfaced after being

temporarily subdued by the turmoil of the

global financial crisis. Estimates from the

International Energy Agency claim that,

despite the most serious global recession

for 80 years, greenhouse gas emissions

increased by a record amount last year

(The Guardian, 2011). This means that the

two-degree target of global warming will be

almost out of reach. To mitigate the

greenhouse effect drastic measures and

international cooperation are necessary

and urgent.

Although the current economic crisis

temporarily shifted focus off the problems

of global warming, the crisis also provides

opportune circumstances to fix

inefficiencies on resource allocation. The

global need for fiscal consolidation and the

search for efficient fiscal correction

measures may in fact facilitate

international agreements that previously

would have been politically infeasible.

The governments face the challenge of

implementing necessary fiscal policy measures while avoiding significantly

slowing down the recovery in domestic

demand and creating another round of

contraction. Reduced public spending and

broadened tax bases notwithstanding, new

taxes and increasing tax rates are

inevitable, while tax cuts to stimulate

growth become less viable. Given an

internationally coordinated policy

implementation, a carbon pricing makes

very good sense from a fiscal perspective as

well as from an environmental perspective.

Carbon tax – the fiscal

perspective

Starting with the fiscal perspective, a

consumption tax, such as a carbon tax2, has

some distinct advantages in general over an

income tax and is therefore advocated by

2Carbon tax is here used as synonymous withall forms of public pricing of carbon. For thefollowing arguments it does not matter whether there is a cap on emissions andemission rights are auctioned off by the state toemitters resulting in a certain price - or if acarbon tax is decided ex-ante hoping toachieve a certain level of emissions. In practicepublic carbon pricing through emission tradingis in many cases more politically feasible andefficient than a carbon tax.

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 3/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

3

many economists. All taxes affect the

allocation of resources. However, whereas

an income tax distorts good behaviour andcauses people to work less and pursue

more leisure activities, a consumption tax

discourages consumer spending and

encourages people to save more.

Differently put, the benefit of consumption

taxes over income taxes is that they do not

distort the intertemporal allocation of

consumption. There is also empirical

evidence that confirm that consumption

taxes affect growth less than income taxes

(See Milesi-Ferretti and Roubini, 1998, for

an overview of the literature).

Correcting the market failures

A carbon consumption tax has all the

advantages of a consumption tax.3

However, in addition it corrects for the

market failure of carbon emissions. Thus,

instead of distorting economic activity as

3Like other flat taxes, a carbon consumptiontax can be regressive with respect to income,i.e. the tax imposes a greater burden on low-income than on high-income households sincelow-income household consume more of theirincome. This is a common objection toreplacing the income tax with a consumptiontax. However, by allocating some of the taxrevenues to compensate the less affluent, thenegative implications of the incomedistribution can be offset.

most other taxes do, a carbon tax

internalises the marginal externalities

from global warming and thereby reallocates resources more efficiently.

Which brings us to the environmental

perspective of carbon taxes. The basic

policy conclusion of the Stern Review is

that a worldwide tax on the consumption

of carbon would hold global warming to

safe levels.

By means of imposing a price on carbon

emissions the demand for fossil fuels

would decrease and the development of

renewable-energy technologies would

accelerate. Depending on the reaction of

the suppliers and thus on the elasticity of

the supply curve, the reduced demand for

fossil fuels reduces emissions and

mitigates global warming. Since it seems

reasonable that the supply curve, at least in

the long run, is elastic, the price of fossil

fuels increases, and, according to standard

tax analysis, the tax burden is shared

between consumers and fossil fuel

producers.

A global tax more efficient

Economic theory provides two important

insights on how an optimal carbon tax

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 4/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

4

scheme should be constructed. Firstly, for

maximum efficiency, a carbon tax should

be global, or at least involving key pollutingcountries. If one country, or a subset of

countries, introduces a carbon tax and

thereby reducing their demand of fossil

fuels, world price of energy would be

reduced. Then other countries excluded

from the agreement would increase their

energy demand and the level of emissions

would be unchanged (Sinn 2008). This

phenomenon – when domestic demand is

replaced by foreign demand – is referred to

as carbon leakage. Another version of

carbon leakage is when production moves

offshore to countries with lower

environmental standards. However,

empirical estimates of carbon leakage show

that the problem with leakage is minor. The

OECD (2009) estimates that a EU

unilateral emission reduction by 50 per

cent by 2050 would result in a carbon

leakage of 13 per cent in 2020 and 16 per

cent in 2050. If all developed countries

undertake similar measures, the leakage of

greenhouse gas would be only 0.7 per cent.

Moreover, if also Brazil, China and India

took comparable actions, the leakage

would be no more than 0.2 per cent. In

addition to carbon leakage, a carbon tax

could have a negative short-run impact on

the international competitiveness of the

front-runners.

A time decreasing tax

Secondly, a robust finding from recent

economic modelling is that the optimal

carbon tax path is falling. More specifically,

a carbon tax must not increase over time.

The intrinsic aim of a carbon tax is to

flatten the carbon supply path over time,

i.e. to slow down the fossil fuel extraction

pace. If fossil fuel resource owners expect

future price cuts due to increasing

environmental standards, resource owners

will have an incentive to extract the fossil

fuel earlier and global warming problems

will even accelerate. Another force behind

this result is that the size of the tax should

be in proportion to the size of the marginal

externality. Since oil use must eventually

be declining over time and as long as there

is some mean reversion in carbon

concentration, the size of the marginal

externality will eventually be declining

over time.

Given these restrictions on the

construction of a carbon tax scheme, a

worldwide time-decreasing carbon tax rate

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 5/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

5

would solve the two most important

problems governments are facing. By

imposing a high carbon tax rate thatgradually diminishes over time resource

owners would be induced to delay fossil

fuel extraction by increasing the return to

keeping oil in the ground. Meanwhile, the

tax revenues that would be falling over

time, mainly as a result of a decreasing tax

base, would match the fiscal needs of the

governments that also would be declining

over time as public finances improve.

An optimal level taxation

What level of carbon tax rate would be

efficient? According to standard Pigou

arguments an optimal tax on carbon

emission would induce the consumer to

internalize the externality. That is, an

optimal tax will equal the marginal

externality damage of emissions. The

marginal externality damage of emissions

depends on various factors like

discounting, the damage function, the

structure of carbon depreciation in the

atmosphere, future values of output,

consumption, and the atmospheric CO2

concentration, as well as on the future

paths of technology and population.

Two of the most well-known studies that

have parameterized and computed the

optimal tax of carbon is Nordhaus (2007)and the Stern report (Stern, 2007). The

estimates amount to a tax of $30 and $250

dollar per ton coal, respectively, which

corresponds to a tax of $8 and $68 dollar

per ton CO2 emission, considering that a

kilo of CO2 contains 0.27 kilos of carbon.

The key difference between the two

proposed tax rates is that they use very

different discount rates, which means that

they put different weight on the future. In a

recent study by Golosov et al (2011), the

optimal tax rate varies between $7 to $1151

dollars per ton CO2, depending on

discount rate and on whether future

consequences of global warming turn out

to be moderate or catastrophic.

It is useful to relate these numbers to taxes

used in practice. Swedish taxes on private

consumption of fossil fuel are in

comparison with the estimated optimal tax

rates actually in the higher range, assuming

market based discount rates and middle

values of future damages. In 2010, the tax is

1.05 SEK per kilo emitted CO2 (Swedish

Tax Agency, 2010) corresponding to a tax

per ton of emitted CO2 of $167, using an

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 6/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

6

exchange rate of 6.30 SEK/$. Carbon taxes

implemented in other countries, for

example in India, Denmark, Finland,Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and

Switzerland, are in general considerably

lower, mainly around $10 - $30.

The estimates tax rates can also be related

to the price of emission rights in the

European Union Emission Trading System,

covering large CO2 emitters in the EU.

After collapsing during the great recession

of 2008-09, the price has hovered around

15 Euro per ton CO2 which, using an

exchange rate of 1.4 dollar per Euro,

corresponds to $21 per ton CO2.

Revenues from a carbon tax

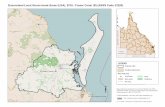

Table 1 (page 8) depicts the revenue

potential from a CO2 tax based on three

different tax rates; $20 that is close to

observed values of trades emission rights

in the EU and to optimal tax rate by

Golosov et al (2011), $60 which is in line

with the proposed policy by Stern review

and $150 per ton emitted CO2 which is

close to the Swedish tax rate. In the

estimations we assume that the tax base,

i.e. the CO2 emissions, is fixed. Obviously,

this can only be true in the short run, since

emissions will decline over time. The pace

and the magnitude of changes in the fossil

fuel usage is however rather difficult toapproximate. Recent estimates of oil

demand price elasticities are indeed very

inelastic since there has not been any

substantial substitution away from oil in

recent years. However, as IMF (2011b)

argues in a recent report new backstop

technologies are emerging and a big switch

at which alternative options become

economically viable cannot be ruled out

over the medium term. In addition,

experience from Sweden show that the

sizable tax rate seem to have reduced CO2

emissions rather substantially, at least in

some sectors (Miljödepartementet, 2009).

By raising a tax to an optimal level, Golosov

et al (2011) show that the optimal

allocation of fossil fuel usage is decreasing

by one third in short run and by half in half

a decade as compared with laissez faire.

To the extent that carbon taxes induce

higher fossil-fuel use elsewhere, carbon

leakage could also be a source of over-

estimation of tax revenues. Irrespective of

the proper price responsiveness of fossil

fuel demand or carbon leakage effects on

tax revenues, table 1 give us an idea of the

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 7/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

7

magnitudes by relating tax revenues to

governmental debt changes during the

global financial and economic crisis.Between 2007 and 2010, all countries in

table 1 except Sweden have increased their

sovereign debt substantially. Debt-ridden

countries like the United States, Ireland

and Japan could in particular benefit by

raising government revenues. A carbon tax

of $20 would be able to meet 3, 1.4 and 2.5

per cent respectively of sovereign debt

deteriorations. On the other hand, a radical

tax increase in line with Swedish carbon tax

rates, would in one time period wipe out 22,

10 and 19 per cent, respectively, of

accumulated government debt. Although

the computations are sketchy, the numbers

are in line with simulated tax revenues

from calibrated models (around 2.5 per

cent of GDP). Real or estimated tax

revenues from already implemented or

proposed national carbon taxes are

obviously problematical as comparison.

The carbon or energy tax schemes are

implemented on different tax bases with

various exemptions.

Apart from being crude, the potential tax

revenues computed in Table 1 do not

account for already implemented national

carbon tax schemes or active emission

trading programs. The most obvious

example is the EU Emissions TradingSystem, which already covers

approximately half of the European

Union’s carbon emissions. From the start

of the third trading period in 2013 about

half of the carbon allowances are expected

to be auctioned. Preliminary computations

of the scale of revenues show that under

the currently proposed structure of EU

ETS Phase III the auctions would raise

€150-190bn ($210-266bn, using an

exchange rate of 1.4 $/€) across the EU to

2020. With a commitment to move to a

30% target the revenues would rise to

€200-310bn ($280-430bn) (Cooper and

Grubb, 2011). Projections from the

European Commission (2010) suggest that

auctioning revenue might increase by a

third, because carbon prices are expected

to increase by more than the reduction of

allowances auctioned.

Conclusion

Realistically the prospects of pulling off an

optimal worldwide time-decreasing carbon

tax scheme seem rather bleak. It is

apparent from rounds of global

negotiations that it is difficult to establish

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 8/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

8

agreement on a global policy. In addition,

judging from harsh industry reactions, it is

also reasonable to believe that it would bepolitically more feasible to gradually

increase carbon tax rates over time.

However, by calling attention to the fiscal

arguments of a carbon tax, which includes

small distortionary economic effects and

tax burden partly carried by foreign oil

producers, national government should be

more easily convinced and maybe also

decide to unilaterally impose a carbon tax,

at least as a substitute for even less popular

tax increase or to finance more growth-inducing tax cuts elsewhere. The risk for

carbon leakage seems to be minor. After all,

it is not bad to achieve fiscal consolidation

while saving the planet for future

generations.

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 9/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

9

References

Cooper, S. and M. Grubb (2011), Revenuedimensions of the EU ETS Phase III,Climate Strategies, 12th May 2011.

EEAG (2011), The EEAG Report on theEuropean Economy, CESifo, Munich 2011.

European Commission (2010), “Analysisof options to move beyond 20%

greenhouse gas emission reductions andassessing the risk of carbon leakage”,Communication from the Commission tothe European parliament, the Council, theEuropean Economic and SocialCommittee and the Committee of theregions, COM(2010) 265 final.

Golosov, M., Hassler, J., Krusell, P. och A.

Tsyvinski (2011), "Optimal Taxes on Fossil

Table 1. Carbon tax revenue and government debt

MtCO2e Carbon taxrevenue

Governmentdebt difference

2007-2010(Million $)

Carbon tax revenueas share of debtdifference (%)

20 60 150 20 60 150

Australia 400,4 8008 24024 60060 -75937 10,5 31,6 79,1

Austria 73,6 1472 4416 11040 -17963 8,2 24,6 61,5

Belgium 117,2 2344 7032 17580 -35715 6,6 19,7 49,2

Canada 573,7 11474 34422 86055 -194581 5,9 17,7 44,2

Czech Republic 120,7 2414 7242 18105 -22314 10,8 32,5 81,1

Denmark 52 1040 3120 7800 -30389 3,4 10,3 25,7

Estonia 17,4 348 1044 2610 -329 105,7 317,0 792,6

Finland 58,1 1162 3486 8715 -17882 6,5 19,5 48,7

France 395,3 7906 2 3718 59295 -300381 2,6 7,9 19,7

Germany 833,1 16662 49986 124965 -66389 25,1 75,3 188,2

Greece 109,8 2196 6588 16470 -101448 2,2 6,5 16,2

Hungary 56,2 1124 3372 8430 -5756 19,5 58,6 146,4

Ireland 47,4 948 2844 7110 -69570 1,4 4,1 10,2

Italy 468,1 9362 28086 70215 -79521 11,8 35,3 88,3

Japan 1214,4 24288 72864 182160 -981027 2,5 7,4 18,6

Luxembourg 11,5 230 690 1725 -6208 3,7 11,1 27,8

Netherlands 175,7 3514 10542 26355 -93672 3,8 11,3 28,1

Poland 323,9 6478 19434 48585 -30815 21,0 63,1 157,7

Portugal 59,5 1190 3570 8925 -36743 3,2 9,7 24,3

Slovak Republik 39,8 796 2388 5970 -11621 6,8 20,5 51,4

Slovenia 17,9 358 1074 2 685 -6077 5,9 17,7 44,2

Spain 337,5 6750 20250 50625 -268379 2,5 7,5 18,9

Sweden 50,4 1008 3024 7560 10495 9,6 28,8 72,0

Turkey 297,1 5942 17826 44565 -22399 26,5 79,6 199,0

UK 536,7 10734 32202 80505 -837690 1,3 3,8 9,6

United States 5912,6 118252 354756 886890 -3980021 3,0 8,9 22,3

Note: Data on Government Debt extracted on 15 Aug 2011 15:00 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat. Governmental debt difference

for Japan is calculated for 2009 – 2007 since data for 2010 was unavailable. Data on total CO2 Emissions in 2008 is extracted

on 1 September 2011 from Climate Analysis Indicators Tool (CAIT UNFCCC) Version 4.0.

(Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2011).

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 10/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

10

Fuel in General Equilibrium", NBER Working Paper 17348.

The Guardian (2011), ”Worst ever carbonemissions leave climate on the brink”,

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 29 May 2011 22.00BST.

International Monetary Fund (2011a),Fiscal Monitor April 2011, ”Shifting Gears,Tackling Challengeson the Road to Fiscal Adjustment”.

International Monetary Fund (2011b), World Economic Outlook April 2011,“Tensions from the Two-Speed Recovery.Unemployment, Commodities, andCapital Flows”.

Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. and N. Roubini(1998), ”Growth Effects of Income andConsumption Taxes”, Journal of Money,Credit and Banking 30(4), pp. 721-744.

Miljödepartementet (2009), “Sverigesfemte nationalrapport omklimatförändringar”, Regeringskansliet,Miljödepartementet Ds 2009:63.

Nordhaus, William (2007), ”To Tax or Notto Tax: The Case for a Carbon Tax”,Review of Environmental Economics and Policy.

OECD (2009), “The Economics of Climate Change Mitigation – policies andoptions for global action beyond 2012”.

Available at:http://www.oecd.org/document/56/0,3746,en_2649_34361_43705336_1_1_1_1,00.html

Stern, Nicholas (2007), The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,UK.

Swedish Tax Agency (2010), Skatter iSverige, Skattestatistisk Årsbok 2010,http://www.skatteverket.se.

8/3/2019 FORES POLICY BRIEF Carbon Taxes to Solve the Sovereign Debt Crisis

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/fores-policy-brief-carbon-taxes-to-solve-the-sovereign-debt-crisis 11/11

FORESPOLICYBRIEF:CarbonTaxestoSolvetheSovereignDebtCrisis

11

About FORES

FORES - Forum for Reforms,Entrepreneurship and Sustainability - isan independent research foundation andthink tank devoted to evidence-basedresearch mainly centred on environmental

economics, migration, structuraleconomic reforms and foreign policy. Weengage academics and experts to proposeconcrete policy proposals and endeavourto bring facts and research to the broaderpublic. FORES functions as a link betweencivil society, entrepreneurs, policymakersand academia, producing research papers,policy briefs and books, and hostingseminars and policy debates.

FORES is based in Stockholm, Sweden,and governed by an independent board of directors and a research board composedof respected academics. Our work is basedon broad principles of liberal democracy and the rights of each person to shape heror his own lives.

Contact

Martin Ådahl, director FORES,[email protected]

Ulrika StavlötResearch director, [email protected]

Daniel Engström StensonProgramme director [email protected]

www.fores.se