FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL: A STATUS REPORT · FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL:...

Transcript of FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL: A STATUS REPORT · FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL:...

FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL:

A STATUS REPORTBaitadi

Surkhet

Banke

Dang

Palpa

Sarlahi

Makwanpur

SindhupalchokDolakha

Ramechhap

Okhaldhunga

Khotang

TaplejungKavrepalanchok

SirahaDhan

usha

Rautahat

Mahotari

Rupandehi

Kanchanpur

Kailali

Bardiya

Doti Achham Kalikot

Darchula

Bajhang

Bajura

Dailekh Jajarkot

Dolpa

RukumMyagdi

Baglung

Parbat

Lamjung

Parsa

Rasuwa

Nuwakot

KtmBhaktapur

Solukhumbu

Udaypur

Saptari

Bhojpur

Dhankuta

Terathum

Pancht

har

Morang

Lalitpur

Manang

Syangja

Rolpa

Pyuthan

Kapilbastu

Arghakhanchi

Salyan

Mugu

Mustang

Kaski

Gorkha

Dhading

Gulmi

Tanahu

NawalparasiChitwan

Bara

Sindhuli

Sunsari

Ilam

Jhapa

Sankhuwa

shabha

Humla

JumlaDadeldhura

FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY IN NEPAL:

A STATUS REPORT

Report byMinistry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics for

the Nepal component of the FAO Project“Building statistical capacity for quality food security and nutrition information

in support of better informed policies TCP/RAS/3409”

January 2016Kathmandu, Nepal

Foreword

It gives me a great pleasure to see the publication of the Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal:

a Status Report,prepared jointly by the Ministry of Agricultural Development (MOAD), Central

Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Let me express at

the outset my thanks to all who contributed to the project and the preparation of this report.

The report is largely based on statistics and information produced by a joint MoAD/CBS/FAO

project designed to strengthen national capacity in generating and analyzing food and nutrition

security information. The two main statistical frameworks focused by the project and utilized by

this report are the freshly compiled Supply Utilization Accounts/Food Balance Sheets(SUA/FBS) for Nepal for 2008 to 2013, and the Nepal Living Standards Survey 2010-11 OtrLSSIII) which provided valuable food and nutrition statistics. Compiling the FBS and extracting and

processing the data from the NLSS III were valuable contributions of the project.

Based on these databases, the study finds that the overall aggregate level of food availability in

Nepal is higher than previously assumed. This also implies lower rates of prevalence of

undernutrition and food inadequacy, which are welcome news. On the other hand, the cross-

sectional analyses based on the NLSS III data show that there are marked gaps in food and

nutrition security status across Nepal's regions and income levels of households. These findings

point to the need for paying as much attention to addressing these gaps in food insecurity as to

enhancing food production at the national level. The study also points to some serious

deficiencies as regards nutrition indicators for under-five children.

The MoAD assigns high priority to enhancing food security through a range of programs that

encompass all the four dimensions of food insecurity. The MoAD is also one of the main

partners of the Multi-sector Nutrition Plan of the Government of Nepal. Availability of high

quality statistics covering all the dimensions of food security, and on a timely basis, is essential

for policy deliberations and fine-tuning of national programmes and projects. The outputs of the

project are valuable in this regard. Let me once again express my appreciation to all who

implemented the project successfully as well as produced this Status Report. Finally, I would

also like to express my thanks to FAO for its technical assistance and overall coordination of this

important work.

December,2015Government of Nepal

Uttam K BhattaraiSecretary

Ministry of Agricultural Development

Table of Contents

I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1

II. FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY STATUS REPORT – PART 1: TRENDS AND

EVOLVING PICTURE .................................................................................................................. 3

2.1 The availability dimension of food security ......................................................................... 3

2.1.1 Trends in cereals production .......................................................................................... 3

2.1.2 Food availability and adequacy of the DES relative to requirements ............................ 5

2.1.3 Availability of food energy, proteins and fats based on the new FBS ........................... 6

2.1.4 Trends in food import dependency based on the new FBS ........................................... 8

2.2 The access dimension of food security ............................................................................... 11

2.2.1 Prevalence of undernourishment and food inadequacy ............................................... 11

2.3 The utilization dimension of food security ......................................................................... 12

2.4 The stability dimension of food security ............................................................................ 14

2.4.1 Trends in instability in selected food security indicators............................................. 15

2.4.2 Climate change risks to food security .......................................................................... 16

2.5 Summary of the main findings ............................................................................................ 17

III. FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY STATUS REPORT – PART 2: VARIATIONS IN

HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY, 2010-11 .......................................................................... 20

3.1 Food expenditure as a share of total expenditure................................................................ 20

3.2 Variations in food nutrient intakes by income and regions ................................................ 22

3.3 Food consumption pattern by major food sub-groups ........................................................ 24

3.4 Variations in the cost of food nutrients ............................................................................... 26

3.5 Extent of the reliance on own food production versus market ........................................... 28

3.6 Variation in market price of foodstuffs ............................................................................... 30

3.7 Indicators of malnutrition of children ................................................................................. 31

3.8 Severity of food insecurity based on Integrated Food Security Phase Classification ......... 33

3.9 Summary of the main findings ............................................................................................ 35

IV. SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS .................................................................. 37

References ……………………………………………………………………………………… 41

Annexes ………………………………………………………………………………………….44

List of figures, tables and annexes

List of figures

Figure 2.1: Trends in per capita cereals production in Nepal, 2000-2013 (in kg/capita/year)

Figure 2.2: Trends in the DES and their adequacy levels for Nepal and other South Asian countries

Figure 2.3: Import dependency rates for food energy, protein and fat derived from cereals and non-

cereals

Figure 2.4: Prevalence of undernourishment in Nepal and South Asia (%)

Figure 3.1: Engle ratio – expenditure on food to total consumption expenditure (in %) by deciles

Figure 3.2: Income elasticity of demand for food by decile

Figure 3.3: Variation in caloric intake levels by TCE decile, 2010/11

Figure 3.4: Variation in intakes of proteins, fats and calories by TCE quintiles, 2010/11

Figure 3.5: Household food expenditure patterns in rural and urban areas, 2010-11

Figure 3.6: Variation in expenditures on cereals and non-cereals by income levels

Figure 3.7: Sources of food consumption, 2010-11

Figure 3.8: Sources of food from markets and own production by income decile, 2010-11

Figure 3.9: Food prices paid by urban and rural households (Rs/kg)

List of tables

Table 2.1: Trends in cereals production in Nepal on a per capita basis, 2000-13

Table 2.2: Trends in the availability of food energy (calories/per capita/day), 2008-13

Table 2.3: Trends in the availability of proteins (grams/per capita/per day), 2008-13

Table 2.4: Trends in availability of fats (grams/per capita/per day), 2008-13

Table 2.5: Import dependency rates (%) measured in terms of food energies supplied by various food

products (average 2008-13)

Table 2.6: Progress made in reducing child undernutrition in Nepal and some South Asian countries

Table 2.7: Six indicators of the stability dimension of food security in Nepal

Table 3.1: Food consumption patterns in Bangladesh, India and Nepal

Table 3.2: Cost of nutrients from various food sub-groups by place of residence and income

Table 3.3: Prevalence rates of stunting, underweight and wasting among under-5 children, 2010/11

Table 3.4: Food insecurity prevalence rates for 13 sub-regions as per the IPC classification, 2014

List of Annexes

Annex 2: A note of the discrepancy on aggregate food supplies in the FAO database and the new

SUA/FBS

Annex 3.1: NLSS III and ADePT-FSM for extracting food consumption statistics

Annex 3.2: Selected key statistics extracted from NLSS III with Adept-FSM software

Annex 4.1: Project activities on capacity building through training and workshop

Annex 4.2: Nepal‘s Multi-sector Nutrition Plan for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and

Child Under-nutrition, 2013-2017

Annex 4.3: Food and nutrition policy, legislations and institutions

Annex 4.4: Food security and nutrition: An Approach Paper to the Thirteenth Plan

Annex 4.5: Report of the final workshop on sharing of the outputs of the Project

Acronyms

ADePT-FSM ADePT-Food Security Module

ADER Average dietary energy requirement

ADSA Average dietary supply adequacy

CBS Central Bureau of Statistics, Nepal

CEF Consumption expenditure on foods

CFI Chronic Food Insecurity

D1-D10 Decile (income groups in NLSS)

DES Dietary energy supplies

FBS Food Balance Sheets

FNS Food and nutrition security

GoB Government of Bangladesh

GoI Government of India

GoN Government of Nepal

HBS Household budget survey

IDR Import dependency ratio

IPC Integrated Food Security Phase Classification

Kcal Kilocalorie

MDER Minimum dietary energy requirement

MT Metric tonne

NDHS Nepal Demographic Health Survey

NLSS Nepal Living Standards Survey

NPC National Planning Commission, Nepal

p.a. Per annum

PoFI Prevalence of food inadequacy

PoU Prevalence of undernourishment

Q1-Q5 Quintiles (income groups in NLSS)

SUA Supply Utilization Account

TCE Total consumption expenditure

WFP World Food Programme of the United Nations

1

I. INTRODUCTION

This report on Nepal‘s food and nutrition security is one of the three main outputs of an

analytical and capacity building regional project coordinated by the FAO Regional Office for

Asia and the Pacific. Besides Nepal, the project is also implemented in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Lao

PDR, the Philippines and Timor-Leste. The main objective of the project is to strengthen national

capacity for generating quality indicators of food and nutrition security (FNS) and analyzing them

for improving policies and programmes. The project was a response by FAO to requests made by

Member countries at the 31st Asia Pacific Regional Conference (APRC) in 2012 for the provision

of technical assistance in strengthening national FNS information systems.

FAO has a long tradition of undertaking analytical and statistical works aimed at improving the

capacity of Member countries to generate essential statistics and indicators, and to use them for

improving food and nutrition policies and programmes. As part of this work, FAO collates a wide

range of indicators on the FNS information system and makes them available in public domain.

One crucial statistical framework that provides a range of FNS indicators is Food Balance Sheets

(FBS). FAO collaborates with its Members in compiling, updating and maintaining national

FBS, currently for about 180 countries. The FBS also provide the core information for

monitoring global trends in hunger, one of the MDG1 target. The FBS is also widely used by

national and international researchers and policy makers. For this reason, FAO devotes a

considerable amount of resources for improving the database.

National consumption, expenditure or income surveys, also called household budget surveys

(HBSs), are also being increasingly used to collect statistics for the FNS information system.

Across the world, the coverage of food and nutrition aspects is being expanded considerably in

recent HBSs. Given the wealth of information available in a HBS, FAO has been promoting its

use for expanding the range of indicators beyond those that are available in the FBS. In order to

facilitate this task, FAO and the World Bank collaborated and produced a software for extracting

FNS statistics from the HBS database. The software is called ADePT-Food Security Module

(ADePT-FSM), which evolved from the Food Security Statistics Module (FSSM) used earlier by

the FAO.

Accordingly, the FAO regional project focused its capacity building activities around these two

statistical frameworks. The project provisioned a number of activities to strengthen national

capacity in utilizing these two sources of statistics. Thus, the three main components of the

project, which correspond to the three project outputs, are:

- Compiling/updating SUA and FBS using FAO harmonized methodological framework;

- Deriving FNS statistics from HBS using the ADePT food security module; and

- Analysing these and other relevant statistics to prepare for Nepal a Status Report on FNS.

2

The rest of this report is structured as follows. Sections II and III present the Status Report,

which is split into two sections considering the different nature of the statistical and analytical

inputs. The analyses are based on two broad categories of statistics. One is time-series data and

related information for documenting the evolution of the food security status over time along its

four dimensions, i.e. availability, access, utilization and stability. The FBS is the principle source

of information for this, along with other time-series indicators for the four dimensions. This

study also makes the most use of the wide range of these statistics available in the FAO database

on food security. The FAO data also helps assessing Nepal‘s progress on FNS in a comparative

manner, e.g. by also comparing the progress made by some neighbouring South Asian countries.

This is the kind of analyses reported in Section II.

The other source of statistics is the NLSS III data as extracted with the Adept software as part of

this project. This data is valuable for understanding cross-sectional variations in food and

nutrition status in Nepal for the survey year, 2010/11 in this report.

From an analytical standpoint, it made a good sense analysing these two sources of statistics

separately, and draw the inferences from both assessments. This is the main reason for splitting

the status report into two sections. Having done this, Section IV summarizes the main findings

and conclusions. A number of Annexes provide further information on the project activities and

supplementary information.

A final workshop was held in Kathmandu on 28 December for sharing the outputs of the Project. It

was attended by members of the task force who directly and indirectly supported the

implementation of the project as well as other government officials and members of the media.

Participants commented on the project activities and main results of various analyses and their

implications. Annex 4.5 presents the report of the workshop.

3

II. FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY STATUS REPORT – PART 1: TRENDS

AND EVOLVING PICTURE

As said at the end of the previous section, this section presents the status report using time-series

data and related analysis. The assessment is structured along the four dimensions of food

security, namely availability, access, utilization and stability. The analysis makes maximum use

of the wide range of statistics on FNS indicators made available by FAO. It also makes use of the

newly compiled SUA/FBS as part of the FAO project. The newly compiled FBS provide data for

2008 to 2013 while FAO indicators begin in 1990. In addition, national sources are also used

where necessary. As said in Section I, while the focus is on Nepal, several tables and graphs also

show similar statistics for some South Asian countries in order to provide a comparative picture

on the progress being made. The section is organized along the four dimensions of food security,

namely food availability, access, utilization and stability, with the last sub-section summarizing

the main findings. The next section continues with the status report based on the NLSS III data

as extracted with the Adept software.

2.1 The availability dimension of food security

Food availability, the first pillar of food security, refers to the physical availability of adequate

levels of food in a particular location, including the country as a whole. For most countries,

production is the main source of availability, with imports augmenting the shortfalls. The same is

true at the household level, with own production supplemented by market purchases. FAO‘s

suite of food security indicators provides time-series data for five indicators: food production,

levels of the Dietary Energy Supplies (DES) and adequacy, protein supply, share of the DES

from cereals, and share of protein of animal origin. This sub-section reviews availability for

Nepal based on two sets of indicators: i) trends in per capita production of cereals and some

other foods; and ii) availability and adequacy of the DES.

2.1.1 Trends in cereals production

Despite the decade-long insurgency, political instabilities and large-scale outmigration of youths

from rural areas, cereal production does not seem to have suffered as much as many in Nepal

perceived or speculated. Total cereal production (paddy, maize and wheat, with paddy in rice

equivalent) in 2011-13 was 33% higher than in 1999-01 (6.9 versus 5.2 million MT). The growth

rate of 2.3% p.a. recorded for the 1990s was largely sustained during the 2000s also (with 2%

p.a. growth rate during 2000-13).1 In the 2000s, cereal output performed even better in the later

years, with 3% p.a. growth rate during 2007-13. So, overall, the performance was not as bad as

often perceived given the adverse environment as noted above.

1 Unless otherwise stated, all annual growth rates reported in this study are trend growth rates estimated by

regressing the log of the variable concerned on time trend, including all the years covered. In other words, these are

not averages of annual percentage changes.

4

The largely sustained performance of the cereals sub-sector in the 2000s was mainly due to

markedly improved performance of maize and sustained growth rate in wheat production. As for

paddy, the growth rate during the 2000s decelerated to one-third of the rate attained in the 1990s

(0.8% p.a. versus 2.4% p.a.). However, paddy production has picked up from 2007. Yet another

positive development was that for all three cereals, it was mostly the growth in yield rather than

area that was behind the growth in output.

For the sake of comparability with the overall food supply trends reviewed in the next sub-

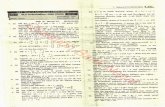

section, Figure 2.1 shows trends in cereals production on a per capita basis, separately for the

three main cereals and their sum, with paddy in rice equivalent. Table 2.1 summarizes related

statistics.

Figure 2.1: Trends in per capita cereals production in Nepal, 2000-2013 (in kg/capita/year)

Note: Cereals total is the sum of paddy, maize and wheat, with paddy in rice equivalent (with a conversion rate of

0.65).

Source: Based on the production data from FAOSTAT.

The figure shows that the overall trend in cereal production on a per capita basis during 2000-13

has been positive for maize, wheat and cereals as a whole but negative for paddy until around

2008 after which the trend has been positive and fairly strong (1.9% p.a. during 2007-13). Paddy

output per person at 174 kg in 2011-13 was actually lower than in 2001-03 (177 kg). The table

also shows good performance for potatoes, soybeans and lentils. The other impression from the

figures is that fluctuations of production around the trends seem to be increasing in more recent

years. The assessment in the following sub-section shows that the overall food supply, i.e.

counting all foods consumed in Nepal, has been improving. In part this was due to growing

imports but the share of imports in total food supply is small, and so most of the credit for

improved aggregate food situation in the country should go to domestic production.

y = 0.1585x2 - 0.4726x + 234.75

210

230

250

270

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Cereals (paddy in rice equivalent), kg/capita/year

y = 0.3172x2 - 5.201x + 187.79

140

160

180

200

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Rice, kg/capita/year

y = -0.0529x2 + 1.9281x + 61.027

60

65

70

75

80

85

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Maize, kg/capita/year

y = 0.0052x2 + 0.9799x + 51.656

50

55

60

65

70

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Wheat, kg/capita/year

5

Table 2.1: Trends in cereals production in Nepal on a per capita basis, 2000-13

1/ Cereals total is the sum of paddy, maize and wheat, with paddy in rice equivalent (with a conversion rate of 0.65).

Source: Production data from FAOSTAT.

2.1.2 Food availability and adequacy of the DES relative to requirements

The dietary energy supplies (DES) is the most popular metric for measuring the sum total of all

food available for human consumption in a country, after deduction of all other uses (exports,

animal feed, industrial use, seed and wastage). It is derived from a FBS and is expressed in

kilocalories per person per day (kcal/person/day). The level of the DES tends to be around 3,000

kcal in countries with virtually zero or very low prevalence of hunger, e.g. in developed

countries as well as in many countries in Latin America. The average for the ASEAN region, for

example, was 2,764 kcal in 2012-14 and 2,769 kcal in developing countries as a whole. The

DES, together with the parameter expressing the distribution of the DES among the population

and a normative minimum requirement, determines the prevalence of undernourishment or of

food inadequacy for a country. FAO‘s food security indicators provide these prevalence rates.

Figure 2.2 shows the levels and growth rates of the DES for Nepal (the lower panel in the figure,

the adequacy rate, is discussed next). Also shown are the data for some other South Asian

countries for comparing the status. The average level of the DES in South Asia-5 was 2,270 in

1991-93, which rose to 2,350 by 1999-01 and to 2,450 by 2011-13. Nepal‘s average DES was

mostly lower than those of the other South Asian countries during 1990-01and 1999-01. But

during 2001-2013, Nepal‘s DES grew the fastest among the five countries and, as a result, was

highest at 2,544 kcal in 2011-13.

As said, the level of the DES needs to be judged against the requirements. FAO provides

indicators for assessing the adequacy of the DES against two levels of requirements. One of them

is Average Dietary Supply Adequacy (ADSA) which expresses the DES as a percentage of the

Average Dietary Energy Requirement (ADER). The ADER covers food requirements associated

with normal physical activity. It is about 25% higher (depends on country factors) than another

level of food requirement, called Minimum Dietary Energy Requirement (MDER) which

indicates the amount of energy needed for light activity. The MDER is the one used for

computing the traditional FAO prevalence of undernourishment. FAO added the ADER in 2012.

2013 over 2013 over 2001 to 2001 to 2007 to

2001-03 2005-07 2011-13 2001 2006 2013 2006 2013

Paddy 177 164 174 -1 6 -0.5 -0.7 1.9

Maize 65 71 78 20 9 1.7 2.0 1.0

Wheat 53 59 66 24 13 1.8 2.6 2.1

Potatoes 61 76 97 57 27 4.7 6.1 3.9

Lentils 6 7 8 27 22 1.7 0.9 5.1

Mustard 6 6 6 3 3 0.0 0.0 0.7

Soybeans 1 1 1 38 29 2.8 1.9 5.3

Cereals total 1/ 233 236 257 10 9 0.7 0.8 1.7

Average values (kg) Percent change Growth rate, % p.a.

6

Figure 2.2: Trends in the DES and their adequacy levels for Nepal and other South Asian

countries

Source: Based on the FAO data.

A value of ADSA greater than 100 indicates that, on average, the total DES available in a

country is more than enough to meet the needs of the population for a healthy and active life. An

important proviso, of course, is how these supplies are distributed among the population. A level

of ADSA of 100 or more would ensure adequate food for all only if the available food is

perfectly equally distributed to all, which hardly happens in real life. In reality, ADSA levels

have to be higher than 100% for lower levels of hunger (discussed below).

The lower panel of Figure 2.2 shows the levels of the ADSA and their trends during the 1990s

and 2000s. The average ADSA for Nepal was 118% in 2011-13 which means that, on average,

the available DES was 18% more than the average requirement (ADER). Nepal‘s ADSA levels

in 1991-93 and 1998-01 were similar to those in other South Asian countries, but surged in the

2000s, growing at the rate of 0.80% p.a., the highest rate among the five South Asian countries.

An ADSA of 118% is indeed similar to that for the developing countries as a whole and thus it

could be said to be on the higher side for a country at Nepal‘s level of development.

2.1.3 Availability of food energy, proteins and fats based on the new FBS

One substantive work under the FAO regional project was the compilation of the SUA/FBS for

six years, 2008 to 2013, based on updated FAO methodology. It was a comprehensive exercise

that required, inter alia, putting together a wide range of statistics from production to trade as

well as various technical coefficients. Nepal‘s FBS maintained by FAO provided the initial basis

for this work. However, the new FBS is much more comprehensive in its coverage of food

products as well as in its use of better statistics and technical coefficients. Hence the indicators

Average DES, kcal/caput/day

Growth rate, % p.a.

1991-93 1999-01 2011-13 1991-00 2001-13

Bangladesh 2,077 2,272 2,454 1.00 0.53

India 2,291 2,359 2,453 0.52 0.73

Nepal 2,218 2,279 2,544 0.38 1.01

Pakistan 2,318 2,365 2,442 0.42 0.58

Sri Lanka 2,165 2,343 2,492 1.05 0.67

SA-5 2,270 2,349 2,454 0.55 0.69

Adequacy of the DES, %

Growth rate, % p.a.

1991-93 1999-01 2011-13 1991-00 2001-13

Bangladesh 97 103 108 0.70 0.22

India 106 107 108 0.28 0.52Nepal 106 108 118 0.24 0.80

Pakistan 109 109 108 0.17 0.28

Sri Lanka 96 102 110 0.82 0.76

SA-5 105 107 108 0.31 0.47

Average values

Average values

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka SA-5

Adequacy of the DES, %

Avg1991-93 Avg1999-01 Avg2011-13

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka SA-5

Average DES, kcal/caput/day

Avg1991-93 Avg1999-01 Avg2011-13

7

from the new FBS should reflect Nepal‘s FNS status more realistically than the picture that

emerges from the current FAO database.

Food energy (DES) – Similar to the trends shown by the FAO database, the new FBS data also

shows steady, albeit modest, growth in aggregate DES during 2008-13, from 2,772 Kcal in 2008

to 2,922 Kcal in 2013, the growth rate being 1.4% p.a. (Table 2.2). Unlike with the FAO

database, the new FBS database is highly disaggregated and so permits reviewing the sources of

the DES from various foods. It shows that the contribution of cereals in the total DES was 65%

during 2008-13 (30% by rice, 20% by maize, 12% by wheat and 3% by other cereals). The

database also shows that not only is the aggregate DES high but also that there have been marked

improvements in the quality of the diet as well. For example, the share of cereals has been

declining, from 68% in 2008 to 61% in 2013, while the growth rate of the share of non-cereals in

total DES has been impressively high (3.4% p.a.). The non-cereals with relatively large

contributions include edible oils (with a 4.8% p.a. growth in its DES), potatoes/yams (5.6% pa),

milk/dairy products (6.1% p.a.) and pulses/beans (9% p.a.). There have been increases also for

sugar and vegetables. Overall, thus, the FBS data show significant positive trends in living

standards.

Table 2.2: Trends in the availability of food energy (calories/per capita/day), 2008-13

Note: Growth rates are computed from log-linear trend regressions with data for 2008-13.

Source: Based on newly compiled FBS for 2008 to 2013.

Protein - Table 2.3 shows similar trends for protein as above for the DES. The national average

level of protein availability increased from 52 gm in 2008 to 60 gm in 2013, equivalent to a

growth rate of 3.3% p.a. Eight products made up 90% of the total during 2008-13, with cereals

Grw. rate

S.N. Product groups 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Av08-13 % Cum % % p.a.

1 Rice 891 837 818 819 831 878 846 30 30 -0.3

2 Maize 525 535 537 604 608 507 553 20 49 1.0

3 Wheat 386 326 406 340 318 321 350 12 62 -3.4

4 Edible oils/oilseeds 217 197 242 253 254 259 237 8 70 4.8

5 Potatoes/yams 126 151 156 158 166 176 155 5 76 5.6

6 Milk/dairy products 118 122 147 142 155 158 140 5 81 6.1

7 Pulses/beans 77 79 72 89 84 134 89 3 84 9.0

8 Spices 65 79 87 88 105 86 85 3 87 6.4

9 Other cereals 90 81 81 81 80 89 84 3 90 -0.3

10 Sugar 75 75 84 82 80 92 81 3 93 3.3

11 Vegetables 64 66 69 74 77 77 71 3 95 4.2

12 Meats 60 69 61 59 59 65 62 2 97 -0.4

13 Fruits 55 57 33 34 49 48 46 2 99 -3.2

14 Nuts 7 7 27 17 11 15 14 0.5 99 12.2

15 Alchol. beverages 10 11 13 13 13 12 12 0.4 100 3.9

16 Fish 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 0.1 100 -1.5

17 Coffee/tea 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0.0 100 6.8

All total 2,772 2,698 2,837 2,855 2,894 2,922 2,830 100 - 1.4

Cereals total 1,892 1,779 1,842 1,844 1,837 1,795 1,832 65 - -0.5

- cereals share % 68 66 65 65 63 61 65 - - -1.8

Non-cereals total 879 919 995 1,012 1,057 1,126 998 35 - 4.8

- non-cereals share % 32 34 35 35 37 39 35 - - 3.4

Food energy -kcal/capita/day

8

contributing 60%. As with the DES, the share of cereals has been declining (at the rate of

negative 2.5% p.a.) while that of the non-cereals increased at the rate of 3.7% p.a., from 25 gm in

2008 to 34 gm in 2013. The food products whose contributions increased markedly are pulses,

milk and dairy products, and potatoes/yams. So, overall, the outcome has been positive for food

security.

Table 2.3: Trends in the availability of proteins (grams/per capita/per day), 2008-13

1/ Sum of fruits, fish, nuts, alcoholic beverages, sugar and tea/coffee.

Note: Growth rates are computed from log-linear trend regressions with data for 2008-13.

Source: Based on newly compiled FBS for 2008 to 2013.

Fats - There has been a marked increase in the national average supply of fats, from 52 gm in

2008 to 60 gm in 2013 (annual growth rate of 3.3%) (Table 2.4). Six groups of foodstuffs

contributed to 90% of the total, with edible oils accounting for 46%, followed by milk/dairy

(18%), maize (9%), meat (8%), rice (5%) and wheat (4%). The data show some notable shifts

taking place, the most prominent being the contribution of milk/dairy, with a trend growth rate of

4.7% p.a. While fats supplied by edible oils increased at the rate of 3.3% p.a., its share in the

total has remained flat. What is somewhat surprising is the negative growth rate for meats despite

the popular perception in Nepal that meat consumption has been growing rapidly.

2.1.4 Trends in food import dependency based on the new FBS

This sub-section highlights trends in food import dependency based on the data from the newly

compiled FBS. One emerging picture of food supply in Nepal is that aggregate availability has

increased considerably during the 2000s but this is also associated with increasing dependency

on imports. The FBS provides highly disaggregated data for reviewing trends in self-sufficiency

rates, or its inverse import dependency rates (IDRs), for individual food products. By converting

Grw. rate

S.N. Product groups 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Av08-13 % Cum % % p.a.

1 Rice 18 16 16 16 16 17 17 23 23 -0.3

2 Maize 13 13 13 15 15 12 14 19 42 1.0

3 Wheat 11 10 12 10 9 9 10 14 56 -3.3

4 Pulses/beans 5 5 5 6 6 9 6 8 64 9.0

5 Meat 5 5 5 5 5 6 5 7 72 1.0

6 Milk/dairy products 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 7 79 2.5

7 Vegetables 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 6 84 1.6

8 Potatoes/yams 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 89 5.6

9 Spices 2 2 3 2 3 2 2 3 93 6.5

10 Other cereals 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 96 -0.2

11 Edible oils/oilseeds 0 0 1 2 2 2 1 1 97 65.4

12 Other 6 groups 1/ 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 100 1.9

All total 70 68 71 72 74 76 72 100 - 2.0

Cereals total 44 41 43 43 43 42 43 60 - -0.6

- cereals share % 64 61 61 59 58 55 60 - - -2.5

Non-cereals total 25 27 27 29 31 34 29 40 - 5.7

- non-cereals share % 36 39 39 41 42 45 40 - - 3.7

Proteins - per capita per day

9

Table 2.4: Trends in availability of fats (grams/per capita/per day), 2008-13

1/ Sum of fruits, potatoes/yams, sugar, fish, coffee/tea and alcoholic beverages.

Note: Growth rates are computed from log-linear trend regressions with data for 2008-13.

Source: Based on newly compiled FBS for 2008 to 2013.

the volume data for individual food items into common metrics, such as calories and protein,

IDRs can be reviewed at the aggregate sub-groups of foods. For example, there are 15 lines of

individual products in the sub-category called ―other cereals‖, for which an IDR can be

computed by first converting the individual foods into the common metrics and aggregating them

to the sub-group.

Figure 2.3 shows, first, the results for the IDRs of three aggregates: cereals, non-cereals and all

foods, and, second, Table 2.5 shows the same results for major food products. The figure shows

that during 2008-13, the IDR for food energy sourced from all foods taken together was 11%, but

only 4% for energy derived from cereals and 25% from non-cereals. The IDR is much higher for

fats, at 37%, due largely to 45% IDR for fats that come from non-cereals. This is also an

indication that as household incomes rise and more nutrients are sourced from non-cereals, the

IDR is likely to increase, unless of course the production of non-cereals expands proportionately.

The results in Table 2.5 show strong positive trends in the IDRs for wheat and rice, with the

value of the IDR being as high as 11% for rice in 2013 and 13% for wheat in 2010. Among other

major products, the IDR for edible oils is very high, at 71%, although the IDR has been stable

during 2008-13. Interestingly, Nepal has been experiencing high IDRs for potatoes, a product for

which Nepal is considered to have natural comparative advantage for production and trade.

Fruits, another important food product and considered to have immense production potentials in

Nepal, also stand out in terms of a strong positive trend in the IDR. For some products with zero

values for 2011 (rows 12 to 16 in the table) the data seem suspect and need to be rechecked

carefully while updating the FBS.

Grw. rate

S.N. Product groups 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Av08-13 % Cum % % p.a.

1 Edible oils/oilseeds 24.4 22.2 26.7 27.0 26.8 27.4 26 46 46 3.3

2 Milk/dairy products 8.2 8.5 11.3 10.8 11.8 12.0 10 18 64 8.0

3 Maize 4.9 5.1 5.0 5.6 5.6 4.7 5 9 73 0.8

4 Meat 4.2 5.2 4.2 4.1 4.1 4.5 4 8 81 -1.1

5 Rice 3.2 3.0 2.9 2.9 3.0 3.1 3 5 86 -0.6

6 Wheat 2.0 1.8 3.5 2.1 1.8 1.8 2 4 90 -3.1

7 Spices 1.6 1.8 1.8 1.7 2.2 1.7 2 3 93 2.8

8 Nuts 0.3 0.3 2.5 1.5 1.0 1.2 1 2 95 28.1

9 Other cereals 0.8 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.8 1 1 96 -0.6

10 Vegetables 0.5 0.6 0.5 0.5 0.6 0.6 1 1 97 1.3

11 Pulses/beans 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.5 0.5 0.8 1 1 98 9.4

12 Sum of 6 groups 1/ 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.7 0.7 1 1 100 5.7

All total 52 51 60 58 59 60 57 100 - 3.3

Cereals total 11 11 12 11 11 10 11 19 - -0.4

- cereals share % 21 21 20 19 19 17 20 - - -3.7

Non-cereals total 41 40 48 47 48 49 46 81 - 4.1

- non-cereals share % 79 79 80 81 81 83 81 - - 0.9

Fat - per capita per day

10

Figure 2.3: Import dependency rates for food energy, protein and fat derived from cereals

and non-cereals (average values for 2008-13)

Note: The numbers indicate what percentage of food energy, protein or fats is derived from cereals, non-cereals and

all foods.

Source: Based on newly compiled FBS for 2008 to 2013.

Table 2.5: Import dependency rates (%) measured in terms of food energies supplied by

various food products (average 2008-13)

Note: A dash (-) for some growth rates indicates that these could not be computed using logs as some numbers

(IDRs) are zero. Annual growth rates are for 2008 to 2013.

Source: Computed from newly compiled FBS for 2008-13.

4 36

25

11

45

11

7

37

0

10

20

30

40

50

Energy Protein Fats

Import dependency rates (%), 2008-13 average

From cereals From non-cereals From all products

Grw.rate

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2008-13 % p.a.

1 Wheat 0.6 0.7 12.5 6.7 1.9 3.2 4.5 30

2 Rice 3.8 4.0 3.6 4.7 7.6 10.6 5.8 21

3 Maize 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 -11

4 Other cereals 1.7 1.6 2.3 2.1 2.8 3.3 2.3 15

5 Potaoes/yams 2.8 2.7 4.6 3.9 6.8 9.0 5.2 24

6 Sugar 18.7 24.8 26.3 21.7 12.9 20.8 20.9 -5

7 Pulses 1.5 42.6 22.5 30.8 24.1 20.4 23.5 34

8 Nuts 66.1 63.4 98.2 107.1 94.7 78.6 90.5 6

9 Edible oils 73.5 75.0 73.5 67.9 68.3 69.7 71.1 -2

10 Vegetables 7.2 5.1 6.0 6.8 8.2 8.2 7.0 6

11 Fruits 6.9 2.8 13.4 2.9 14.0 17.2 9.4 23

12 Tea/coffee 58.8 69.2 72.3 0.0 69.4 68.1 64.7 -

13 Spices 8.5 12.6 7.4 0.0 8.5 18.6 9.2 -

14 Meat 0.8 11.3 0.2 0.0 0.1 0.2 2.3 -

15 Milk/dairy products 1.6 2.0 3.1 0.0 2.9 2.7 2.1 -

16 Fish 0.9 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.3 -

17 Alcoh. drinks 16.1 34.3 34.1 27.1 30.2 45.3 31.5 13

Cereals 2.0 2.2 4.5 3.4 3.9 6.0 3.7 20

Non-cereals 22.9 26.0 27.6 24.8 24.3 26.3 25.4 1

All total 8.7 10.3 12.6 11.0 11.4 13.8 11.3 7

Import dependency rate , %

11

2.2 The access dimension of food security

Access, the second pillar of food security, is crucial for ensuring food security. Even if food is

physically available in a region or country, it may not be accessible if households lack

purchasing power. Thus, access is essentially a problem for low-income households not being

able to buy adequate food that is physically available in the country or local markets. Typical

determinants of access would thus include income levels of the poor, overall distribution of

income in the country, food inflation, employment programmes and social safety nets for the

poor.

FAO provides time-series data for 9 indicators under the access dimension. These include

indicators of the state of transport and market (paved road, road density, rail lines), income

growth and food price index and share of food expenditure of the poor. Two of the other three

indicators are prevalence rates (of undernourishment and of food inadequacy) while the third is

also a related indicator, the depth of food deficit.

This section reviews the state of access to food based on the two prevalence rates, of

undernourishment and of food inadequacy. The former is the main indicator of hunger monitored

by FAO for decades. Note that although these appear as outcomes and hence seem to belong to

the utilization dimension of food security, in reality the prevalence rates are indicators of access

as they tell what percentage of the population, obviously the poorest ones, fail to access

minimum or adequate foods. Besides this sub-section, most of the analysis reported in Section III

is about access, based as it is on household income and expenditure survey data.

2.2.1 Prevalence of undernourishment and food inadequacy

The prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) is the traditional FAO indicator of hunger, as well as

one of the MDG1 indicators. The PoU measures the percentage of population that is at risk of not

covering the food requirements associated with normal physical activity, also the level associated

with a ―hunger‖ threshold (the MDER). FAO also provides since 2012 a new prevalence rate

based on a higher level of food requirement (the ADER) (but using the same level of the DES).

This is called the prevalence of food inadequacy (PoFI).

Figure 2.4 shows the evolutions of the PoFI and PoU for Nepal as well as for four other South

Asian countries. The figures and the associated statistics show the following two main results.

First, the prevalence rates are lowest for Nepal, with 19% for the PoFI and 13% for PoU in 2011-

13, versus 24% and 15% for India and 25% and 16% for South Asia-5 as a whole, respectively.

Second, Nepal achieved sharp reductions in the prevalence rates in the 2000s, not in the 1990s.

The reduction rates for Nepal in the 2000s were 4.5% p.a. for the PoFI and 5.7% p.a. for the

PoU. These rates are several times higher than those attained by other countries in South Asia. In

contrast to Nepal, other countries attained steeper reductions in the 1990s.

The depth of food deficit is yet another useful indicator of food deprivation among the suite of

FAO indicators. It indicates the amount of calories that would be needed to lift the

12

Figure 2.4: Prevalence of undernourishment in Nepal and South Asia (%)

Source: Based on the data from FAO Food Security Indicators.

undernourished from their status, other things being the same. The data show that the depth of

food deficit, at 79 kcal/capita/day in 2012-14, is lowest for Nepal, versus 110 for India and 118

for South Asia-5. It means that Nepal needs to raise food supply on average equivalent to 79

kcal/capita/day so as to lift the remaining population just above the hunger line.

Thus, overall, Nepal‘s food security situation based on the indicators of food supply appears

much better than those of other South Asian countries. Note that the main reason for Nepal‘s

relatively lower levels of the PoFI and PoU is the food adequacy rate of 118% (the ADSA), as

reviewed above. Distribution remaining the same, food adequacy level has to be raised further to

reduce the prevalence rates to even lower levels.2 Even at the current level of food adequacy,

Nepal fares better than many other developing countries with higher levels of per capita GDP.

2.3 The utilization dimension of food security

The reason utilization is considered to be a separate dimension of food security is that even if the

quantity of the dietary energy intake is adequate, human body may not properly utilize the food

due to factors such as illness and infection, prolonged inadequacy of food intake, repeated

episodes of infections, repeated episodes of acute undernutrition etc. Other factors that affect

utilization include micronutrient deficiencies, food quality and safety during preparation and

access to safe water and hygienic conditions. The two prevalence rates – the PoU and PoFI -

measure food shortages in terms of caloric deficits but do not tell the full story of malnutrition. In

2 For a sample of 123 pairs of the ADSA and PoFI for 41 sub-Saharan African countries, the estimated regression

relationship was found to be as follows: % PoFI = 161.5 - 1.2 * % ADSA (Konandreas et al. 2015). Thus, an ADSA

of 118% (Nepal‘s) gives a PoFI of 20%. An ADSA of 126% is required to reduce the PoFI to 10% and of 130% for

a PoFI of 5%.

Prevalence of food inadequacy (%)

Growth rate, p.a.

1991-93 1999-01 2011-13 1991-00 2001-13

Bangladesh 42 34 27 -1.9 -0.8

India 32 26 24 -2.9 -1.8

Nepal 32 31 19 -0.4 -4.5

Pakistan 33 30 30 -1.4 -1.0

Sri Lanka 43 39 33 -1.2 -1.6

SA-5 33 28 25 -2.5 -1.7

Prevalence of undernourishment(%)

Growth rate, p.a.

1991-93 1999-01 2011-13 1991-00 2001-13

Bangladesh 34 24 17 -3.3 -1.2

India 23 17 15 -3.8 -2.5

Nepal 23 22 13 -0.3 -5.7

Pakistan 25 23 22 -1.6 -1.4

Sri Lanka 31 30 25 -0.3 -1.8

SA-5 24 19 16 -3.4 -2.3

Average values

Average values

0

10

20

30

40

50

Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka SA-5

Prevalence of food inadequacy (%)

Avg1991-93 Avg1999-01 Avg2011-13

0

10

20

30

40

Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka SA-5

Prevalence of undernorishment (%)

Avg1991-93 Avg1999-01 Avg2011-13

13

diets consisting mainly of staple cereals or root crops, it is possible to consume enough calories

without consuming enough micronutrients.

FAO database provide statistics for 10 indicators related to utilization. These include access to

improved water sources and sanitation facilities, prevalence rates for wasting, stunting and

underweight among under-5 children, underweight among adults, prevalence of anaemia among

pregnant women and under-5 children, and deficiencies in vitamin A and iodine. The assessment

below focuses on the three most prominent indicators of utilization - prevalence of wasting,

stunting and underweight among the children under five years. Nepal‘s most recent

comprehensive household survey (NLSS III) also provides data on these and other indicators

based on anthropometric measurements (NPC/CBS/WFP 2013). These data are reviewed in

Section III.

Stunting (low height for age) refers to an outcome when the height-for-age of a child under 5

years of age falls below 2 standard deviations below WHO‘s 2006 child growth standards.

Wasting is measured similarly for low weight for height. Underweight refers to low weight for

age and is a composite indicator based on stunting and wasting. Table 2.6 shows the progress

made by Nepal in reducing child undernutrition. Also shown are the outcomes for some South

Asian countries for a comparative picture.

Table 2.6: Progress made in reducing child undernutrition in Nepal and some South Asian

countries

Note: A dash "-" indicates missing data for that (or nearby) year. For India, the data is for 1999 (not 2001); and for

Sri Lanka for 2000 (not 2001) and 2009 (not 2011).

Source: Prevalence rates from FAO food security indicators database; annualized rates computed.

2001 to 2006 to 2001 to

2001 2006 2011 2006 2011 2011

-------- Stunting --------- ------------ Stunting --------------

Bangladesh 55.4 47.0 41.4 -3.3 -2.5 -2.9

India 51.0 47.9 - -0.9 - -

Nepal 57.1 49.3 40.5 -2.9 -3.9 -3.4

Pakistan 41.5 - 43.0 - - 0.4

Sri Lanka 18.4 - 19.2 - - 0.5

--------- Wasting --------- ------------ Wasting --------------

Bangladesh 13.2 12.4 15.7 -1.3 4.7 1.7

India 19.8 20.0 - 0.1 - -

Nepal 11.3 12.7 11.2 2.3 -2.5 -0.1

Pakistan 14.2 - 14.8 - - 0.4

Sri Lanka 15.5 - 11.8 - - -3.4

------- Underweight ------- ------------ Underweight -----------

Bangladesh 45.4 39.8 36.8 -2.6 -1.6 -2.1

India 44.4 43.5 - -0.3 - -

Nepal 43.0 38.8 29.1 -2.1 -5.8 -3.9

Pakistan 31.3 - 30.9 - - -0.1

Sri Lanka 22.8 - 21.6 - - -0.7

Prevalence rates (%) Annualized growth rates (% p.a.)

14

In cross-country comparisons, Nepal is considered to be one of the top ten countries in the world

with the highest prevalence of stunting. The data in the table show high levels of stunting for

Nepal as well as other South Asian countries with the exception of Sri Lanka. Nepal‘s prevalence

of stunting was higher than that in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan in 2001 and 2006 but declined

to below the levels of Bangladesh and Pakistan by 2011. The annualized growth rates show that

the rate of decline was highest for Nepal among the five countries. Most notably, Nepal‘s

prevalence of stunting declined rather impressively by 3.9% p.a. during 2006-11.

Nepal had the lowest prevalence of wasting in 2001 among the five South Asian countries. The

rate increased slightly in 2006 but came down again in 2011 when it was lowest again. As with

stunting, the rate of reduction was high during 2006-11. In contrast, Bangladesh has experienced

an increase in the prevalence of wasting.

Nepal had relatively high rate of prevalence of underweight in 2001 but the rate of reduction has

been impressive and as a result the prevalence rate fell to low levels, lower than in Bangladesh

and Pakistan. In 2009, Nepal‘s prevalence rate was also lower than India‘s by 5 percentage

points.

While the overall outcome for Nepal as a whole has been positive, there is a wide variation in

undernutrition rates across the country, as is the case with other indicators. Nepal Demographic

and Health Survey shows that stunting among rural children is 15% points higher than among

urban children (42% versus 27%). In contrast, the prevalence rates in the hills and the Tarai

regions are not that different: in the Tarai, 37% stunting, 11% wasting and 29% underweight and

in the hills 42% stunting, 11% wasting and 27% underweight. However, the prevalence rate is

very high (53%) in the mountains.

2.4 The stability dimension of food security

Stability is a cross-cutting concern in that stability is sought across all the three other dimensions

of food security, including in the outcomes and the inputs that contribute to the outcomes. One

could thus say that stability is ensured when food availability, access and utilization remain

secure throughout the year and for the long-term. The indicators of stability should in principle

include all the main key drivers of availability, access and utilization, e.g. stable food production,

ensuring that food import capacity is stable and that household incomes and market prices are

not subject to large fluctuations.

For the stability dimension, FAO provides, in its suite of food security indicators, time-series

statistics for the following seven indicators. Two are related to production shocks - percent of

arable land equipped for irrigation and per capita food production variability. Two others

concern with food imports - cereal import dependency ratio and value of food imports over total

merchandise exports. The fifth is domestic food price volatility while the sixth is about the

stability of the overall food supply – the per capita food supply variability. The indicators also

include political stability and absence of violence and terrorism.

15

Besides these traditional indicators of stability, climate change as a source of production shocks

is also pertinent to stability concerns of food security. A great deal of interest is being taken in

Nepal on the subject of climate risk and agriculture/food security, as evidenced by fresh

publications and field projects.

In view of this, this sub-section has two parts. The first reviews the traditional indicators of

stability, using the FAO data. The second highlights some issues on climate risks and food

security.

2.4.1 Trends in instability in selected food security indicators

Table 2.7 shows for Nepal, as well as for two other South Asian countries, the progress being

made on six of the seven FAO indicators of stability. The two trade indicators (1 and 2) together

show a worsening of the situation for Nepal. Indicator 1 tells that cereal import dependency has

been increasing since the early 2000s (while declining for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, for

example). This is a common knowledge in Nepal as food imports have been surging in recent

years. While import dependency increased, the capacity to import foods (indicator 2) has

worsened, with the ratio of food imports to merchandise exports surging from 31% in the early

2000s to 52% in the recent years, amounting to a 7.5% p.a. growth rate of the ratio. Nepal‘s

exports have been faltering in recent years and that partly explains the worsening of the food

import capacity. The status would appear somewhat better if exports also included services as

Nepal‘s situation on this is better.

Indicator 3 shows some improvement, i.e. an increase in irrigated area. While irrigation

contributes to some stability for water-intensive crops, indicator 5 shows that there has been an

increase in the volatility of per capita food production as a whole. Indicator 4 shows an

improvement, with stable or slightly negative trend in food price volatility, in contrast to the

situation in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka for example, where volatility has been growing. But note

that the level of price volatility is higher for Nepal. The positive outcome for Nepal owes, most

presumably, to food price stability in India. The trend rate of the volatility index for India (-0.3%

p.a.) was almost the same as for Nepal (-0.2% p.a.) although the level of the volatility for India is

about half the level for Nepal (4.8 for India versus 9.7 for Nepal).

Finally, indicator 6 shows some slight improvement in the volatility of the overall food (DES)

supply. In contrast, marked declines were recorded for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. One could

argue that Nepal‘s status on this indicator could have been worse given the slight increase in the

variability of food production. Most likely, domestic production shortfalls were offset by surging

food imports, in turn financed by large increases in remittances. Thus, it could be argued that

while trade indicators in themselves appeared negative, they could be responsible for the positive

outcome on overall food supply.

16

Table 2.7: Six indicators of the stability dimension of food security in Nepal

Note: Exports in Indicator 2 refer to merchandise exports. Indicator 5 measures production in constant 2004-06

international USD prices. Indicator 6 measures supply in terms of kcal/caput/day, i.e. the DES values.

Growth rates are percentage per annum, estimated from a log-linear regression on time trend using all the

observations available.

Source: Based on the FAO data on food security indicators.

Trends in variability in annual harvests of paddy, maize and wheat as well as cereals can be

visually appreciated from graphs in Figure 2.1 earlier. The figures show that fluctuations around

the trend lines were much lower during 2000-06 but were magnified after 2006, besides

becoming more frequent. For example, paddy output slumped by 10% in 2007 and, after

recovering for two seasons, by 12% in 2010 and again by 12% for the third time in 2013. Maize

suffered largest slump of 16% in 2009 but again a decline of 8% in 2013. Because of these recent

events, the link between climate risks and food security is attracting a great deal of attention -

discussed next.

2.4.2 Climate change risks to food security

How climate change impacts agriculture and livelihoods in Nepal has become an increasingly

researched subject in recent years. There are several recent studies on this subject, some of them

focused on food security. The later include WFP (2014) on climate risks and agriculture and

Krishnamurthy et al. (2013) published by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change,

Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). NPC/CBS/WFP (2013), which was the study that

analysed the NLSS III data for food security and nutrition, also has a section devoted to climate

change and food security. GoN (2011) is Nepal‘s National Framework on Local Adaptation

Plans for Action, prepared by all LDCs as part of a work programme of the UN framework for

climate change. FAO has also an ongoing project in Nepal on this subject. What follows

highlights some aspects of climate change and food security drawn from some of these studies.

2. Food imports to exports ratio (%)

Growth Growth

2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a. 2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a.

Nepal 1.4 3.6 13.4 Nepal 31.0 52.0 7.5

Bangladesh 10.5 9.4 -1.4 Bangladesh 23.0 21.3 -1.3

Sri Lanka 38.0 33.3 -1.8 Sri Lanka 13.3 17.7 4.4

4. Volatility of domestic prices (index) Growth

Growth 2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a.

2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a.

Nepal 50.0 59.3 2.1 Nepal 10.3 9.7 -0.2

Bangladesh 55.3 66.8 2.4 Bangladesh 4.1 7.9 5.5

Sri Lanka 61.4 47.3 -3.2 Sri Lanka 7.3 8.7 3.0

5. Per capita food production volatility (index) 6. Per capita food supply volatility (index)

Growth Growth

2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a. 2000-02 Latest 3 yrs rate % p.a.

Nepal 2.6 3.2 3.1 Nepal 26.7 25.3 -0.6

Bangladesh 4.4 3.8 -0.3 Bangladesh 57.0 22.7 -9.9

Sri Lanka 3.6 4.1 2.8 Sri Lanka 40.7 24.7 -7.7

1. Cereal import dependency ratio (%)

Average values

Average values

Average values

Average values Average values

Average values

3. Arable land irrigated (%)

17

There is a consensus that Nepalese agriculture, and farm livelihoods as a whole, is highly

vulnerable to climate risks and that this risk will continue to elevate in the coming years. It has

been claimed based on an analysis of the historical data that almost 50% of the variability in crop

yields in Nepal during 1965-2005 could be explained by variations in temperature and

precipitation. Further, this correlation is much higher than those found in global analyses,

highlighting the high sensitivity of food production in Nepal to climatic variability. Over the last

decade, the data reveal that around 30,845 hectares of land owned by almost 5% of households

became uncultivable due to climate-related hazards. Moreover, climate-related disasters such as

inundations, landslides and droughts have increased and had a significant impact on livelihoods

and food security. For example, the 2008 floods affected over 6 million people (30% of the

population) and the 2008/2009 drought resulted in over a 15% decline in winter crop production.

It is noted in particular that under a climate change scenario, food access in the mountain areas

would suffer more, not only through significant declines in winter crops due to low precipitation

but also through disruptions to the functioning of markets from events such as landslides and

floods. The disaster reports from the OCHA suggest that over the last 25 years the impacts of

floods occurring during the monsoon months have increased.

One main official document of the GoN on response measures to climate risk is National

Framework on Local Adaptation Plans for Action. Many programmes and activities on climate

change adaptation are being implemented by the government as well as other agencies, with

enthusiastic support from development partners. FAO has also an ongoing project in Nepal on

this subject. Climate risks have now been recognized as one of the core elements of the stability

dimension of food security.

2.5 Summary of the main findings

This section presented a status report on food and nutrition security (FNS) in Nepal based on an

analysis of the evolution of the FNS indicators since the 1990s. The analysis was largely based

on FNS indicators from FAO, supplemented by data from the newly compiled SUA/FBS and

other national sources. The assessment was structured along the four dimensions of food

security, namely availability, access, utilization and stability. In order to provide a comparative

picture, Nepal‘s rate of progress was also compared to those for some other South Asian

countries, which was insightful. This status report continues to the next section with analysis

based on the NLSS III data.

Trends in food availability were assessed based on two indicators, cereals production and dietary

energy supplies (DES). First, the overall growth rate of per capita cereal production during

2000-13 has been positive for maize, wheat and cereals as a whole despite being negative for

paddy. But paddy production also picked up since 2008. The production growth was mainly due

to yield rather than area expansion. There were notable increases in the outputs of potatoes,

soybeans and lentils. Second, the FAO data on the availability of all foods in terms of the DES

averaged 2,544 kcal in 2011-13, which is markedly higher than the average level for other four

18

South Asian countries. Nepal had lagged behind others in the 1990s but made good progress in

raising the level of the DES during the 2000s.

While this picture is impressive in both the absolute and relative sense, the new data on food

availability from the freshly compiled SUA/FBS for 2008-13 shows a superior performance. The

new FBS estimates give an average DES level for 2008-13 of 2,830 kcal, higher by 297 kcal or

12% over the FAO number (also higher levels of protein and fats). This is indeed a large

difference. The DES level estimated from the NLSS III data (2,725 kcal) lies in-between the

above two estimates.

One important output of the Project is the compilation of fresh SUA/FBS for 2008-13. This work

was valuable in identifying several shortcomings in the FBS maintained by the FAO. A number

of important discrepancies were also noted. Annex 2 provides a brief on the reasons for these

discrepancies. One source was obvious – 20% of the discrepancy in the estimated DES levels (as

well as protein, fats etc.) was due to population numbers used, with FAO using higher numbers

(and hence lower DES level) and the revised SUA/FBS using lower numbers (hence higher DES

level). Other discrepancies were related to differences in production data, coverage of food

products, differences in trade data and trade coverage, assumptions on various uses of food,

conversion rates, and so on.

In the traditional FAO method, prevalence rate for hunger is estimated based on three statistics:

the DES, a parameter for the distribution of the DES, and food energy requirement. Higher the

DES, lower is the prevalence rate, holding the other two parameters constant. Using the same

level of energy requirement (2,200 kcal) and distribution parameter, the resulting prevalence

rates for 2010-11 are as follows: 17% using the DES from the new FBS, 22% using the DES

level from the NLSS III and 31% using the DES level in the FAO database. The prevalence rates

for undernourishment (PoU), similarly computed based on 1,724 kcal as the requirement, are

2.5%, 3.8% and 6.8% with the three DES estimates, respectively. These differences are

substantive.

Even with the lower DES level in the FAO data, Nepal stands out among four other South Asian

countries in having the lowest prevalence rate during 2011-13. Nepal attained this position by

significantly lowering the prevalence rates during the 2000s, not in the decade of the 1990s,

whereas the rates of hunger reduction for the other countries were slower during the 2000s than

in the 1990s.

The three indicators for the utilization dimension of food security assessed in this section were

stunting, wasting and underweight. On these, Nepal is generally considered to have relatively

high prevalence rates compared to countries at similar levels of development. While the levels

may be high in an absolute sense, the data for 2001, 2006 and 2011 (the survey years) show that

Nepal attained impressive rates of reduction of stunting and wasting, with even higher rates of

reduction during 2006-11. While the overall outcome has thus been positive, there is a wide

19

variation in these indicators across the country with some regions suffering from very high rates

(discussed further in Section III).

Finally, the stability dimension of food security was assessed based on seven indicators. These

pointed to different outcomes. Two trade indicators showed worsening trends - cereal import

dependency has been rising, while Nepal‘s capacity to import food (in terms of export earnings

from goods) has been falling. The data show some progress with the extension of the irrigated

area, which is a positive factor for stability. In the meantime, the volatility of food production

has increased in recent years, with climate shocks increasingly seen as the main reason.

However, on a positive note, the volatility of the overall food availability (the DES) has not

increased over time despite an increase in the volatility of food production, most presumably

because imports offset the supply shortfalls quickly and efficiently. It seems that one price Nepal

has been paying for higher aggregate food supplies is increasing dependency on food imports.

This is despite the positive trends in the production of cereals and several other foods –

obviously, the supply response is inadequate to meet the surging demand for food in Nepal.

20

III. FOOD AND NUTRITION SECURITY STATUS REPORT – PART 2: VARIATIONS

IN HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY, 2010-11

Nepal‘s third comprehensive survey of living standards, the Nepal Living Standards Survey

(NLSS III), is a unique source of information on various aspects of food consumption by

households living in different parts of the country and belonging to different income groups. For

this reason, one core activity under the FAO regional project was to utilize this information for

profiling food and nutrition security (FNS) status. This was done with the help of a software

specifically designed for this purpose, the ADePT-Food Security Module (ADePT-FSM), jointly

developed by FAO and the World Bank (see Annex 3.1 for an introduction to the NLSS III and

Adept-FSM module). The documentation of the FNS status in this section is mostly based on the

NLSS III data extracted with the Adept-FSM. Annex 3.2 presents most of the statistics used in

this section.

The following six topics are discussed in this section: i) food expenditure as a share of total

expenditure; ii) variations in food nutrient intakes by regions and income; iii) food consumption

pattern by major food sub-groups; iv) variation in the cost of macro food nutrients; v) extent of

the reliance on market versus own production; and vi) variation in market price of food products.

In addition, the results of the 2014 survey of chronic food insecurity undertaken with the IPC

tool are also summarized in one sub-section. In terms of the four dimensions of food security,

most of the topics discussed below belong to the access dimension, specifically household access

to food.3

3.1 Food expenditure as a share of total expenditure

The share of total income or total consumption expenditure (TCE) on food, also called the Engle

ratio, is one of the closely monitored indicators of household wellbeing. This is also included

among the FAO suite of indicators for the access dimension of food security. An established

pattern throughout the world is the decline in the Engle ratio as income rises – the main

empirical questions asked are how high is the ratio for the low income groups and how rapidly

does the ratio decline with rises in income.4

The Engel ratio for Nepal as a whole in the 2003/2004 NLSS was 39% for urban and 63% for

rural areas. Seven years later, in 2010/11 (NLSS III), the ratio has barely changed – slightly

worsening for urban areas (to 40%) and slightly improving for the rural areas (to 61%). By

3 Having similar dataset for the previous NLSS would have considerably enriched the analyses, as this would allow

an assessment of the progress made between the two survey years, as well as the drivers of the changes. There are

however some written works that provide some information on changes between the two surveys – that literature is

consulted for the writeup here. 4 Note that Engle ratio is traditionally associated with income. Income, however, is relatively difficult to measure

accurately, and so most household surveys use consumption expenditure for analyses, as a proxy for income. Income

and total expenditure are often used interchangeably in studies based on such surveys, including in this section, but

the correct variable is total consumption expenditure and not income.

21

development region, the ratio for 2010/11 was lowest for the central region (49%) and around

60% for the other four regions. It is obvious that the figure for the central region is heavily

influenced by the weight of Kathmandu valley, where the ratio is lower on account of higher

incomes.

The main source of variation in the Engle ratios is TCE. The NLSS III provides data on the TCE

as well as consumption expenditure on foods (CEF) by 10 income groups (deciles) which

provides the shape of the Engle curve. This is shown in Figure 3.1 (also shown for comparison

the corresponding trend for Bangladesh based on 2010 household survey). For Nepal, the Engle

ratio drops from 72% for the poorest 10% of the population (first decile, called D1) (by a

coincidence, the ratio is the same for both the urban and rural areas) to 32% and 41% for the

richest 10% population (called D10) in the urban and rural areas, respectively. The following

points may be noted.

Figure 3.1: Engle ratio – expenditure on food to total consumption expenditure (in %) by

deciles (2010-11 for Nepal, 2010 for Bangladesh)

Source: NLSS III as generated by Adept-FSM for Nepal and GoB (2010) for Bangladesh.

First, while the ratio was the same, 72%, for D1 in both areas, it falls more rapidly for urban

households. For example, the ratio for D4 was 61% in urban but 68% in rural areas, with the

rural households reaching that level only when the TCE rises to a level between D7 and D8.

Second, the graphs show that the declines in the Engle ratios are not linear. For rural households

in particular, the declines are slow until D7 after which the ratio falls rapidly. For urban area, the

declines are much more linear with rises in TCE, notably from D3 to D9. An inspection of the

TCE and CEF data shows that while the TCE changed similarly by deciles, the CEF drops faster

for urban household. This could be due to several reasons, such as the availability of various

foods, food preferences as well as prices. Such an analysis requires finely disaggregated data and

a suitable analytical framework, something worth undertaking as a follow up work.

Comparing Nepal with Bangladesh, the graphs show superior food access status for the urban

households in Nepal, with Nepal‘s Engle ratios being consistently smaller, by 5-8 percentage

points, than Bangladesh‘s. The opposite is the case for the rural households, with the exception

of those in the D9 and D10 deciles, but the differences are small. Note also that for Bangladesh

too, the rate of decline in the Engle ratios is much slower for the rural than for the urban

households, similar to Nepal‘s case.

30

40

50

60

70

80

D 1 D 2 D 3 D 4 D 5 D 6 D 7 D 8 D 9 D 10

Engle ratio (%) - urban

Nepal Bangladesh

30

40

50

60

70

80

D 1 D 2 D 3 D 4 D 5 D 6 D 7 D 8 D 9 D 10

Engle ratio - rural

Nepal Bangladesh

22

The Adept software also generates income elasticity of demand for food by income deciles.

Figure 3.2 shows that, as expected, the values of the elastcities fall with increases in the TCE.

The elasticity dropped from 0.46 for D1 to 0.23 for D10 for rural households and from 0.30 to

0.18 for the urban households. Note that the differences in the values of the elasticities for urban

and rural households belonging to the same decile are marked, by about 0.15 for lower deciles

and by about 0.08 for higher deciles.

Figure 3.2: Income elasticity of demand for food by decile

Source: NLSS III data as extracted with Adept-FSM.

3.2 Variations in food nutrient intakes by income and regions

The Adept-FSM provides data from the NLSS III that enables an analysis of the relationship

between the levels of food energy intake and TCE, graphed in Figure 3.3. The graph shows

positive relations between TCE and kcal, as expected, but the relationship is not linear

throughout the income levels (note that the levels corresponding to Q10 are very high, clearly so

for rural households (4,151 kcal), and so the data are highly suspect and could be ignored until

this matter is re-checked and resolved). For urban areas, the kcal rises markedly up to Q3 and

then increases only slowly. For the rural areas, the relationship is stronger but with variations at

different levels of the TCE.

One way to summarize the response of the kcal to changes in the TCE is to compute anelasticity.

Although somewhat crude, a simple way is to regress the log of the kcal on the log of the TCE.

The results are as follows:

ln (kcal) = 6.94 + 0.19 ln (TCE) (for urban area)

ln (kcal) = 6.48 + 0.34 ln (TCE) (for rural area)

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0.40

0.45

0.50

D 1 D 2 D 3 D 4 D 5 D 6 D 7 D 8 D 9 D 10

Income elasticity of demand for food concumption

Nepal

Urban

Rural

23

Figure 3.3: Variation in caloric intake levels by TCE decile, 2010/11

Source: NLSS III data as extracted with Adept-FSM. Note that the levels corresponding to Q10 are very high,

clearly so for rural households (4,151 kcal), and so the data are highly suspect and could be ignored until the matter

is re-checked and resolved.

The implied elasticity values are 0.19 and 0.34. This means that for every 10% increase in the

TCE, the kcal level rises by 1.9% for the urban and 3.4% for the rural areas. The higher elasticity

for the rural area is obvious from the graph also. While these values are similar to those from

other studies in South Asia and elsewhere, why the response is almost double for rural

households is not as clear. The difference in the sources of the calories obtained from different

foods may explain this to some extent, but available data do not allow further analysis of this

matter. It is also possible that there could be some bias in the kcal data as the gaps between the

rural and urban intakes are too wide to be explained by similar levels of the TCE for various

deciles.

As regards other macro nutrients (proteins and fats), data are available for income quintiles only.

The relationships are shown in Figure 3.4 (also shown is the graph for calories by quintiles, for

comparison sake). The graphs show that for all three nutrients, consumption levels increase with