Fish Weirs, Salmon Productivity, and Village Settlement in an Upper Skeena River Tributary, British...

-

Upload

paul-prince -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

4

Transcript of Fish Weirs, Salmon Productivity, and Village Settlement in an Upper Skeena River Tributary, British...

Fish Weirs, Salmon Productivity, and Village Settlement in an Upper Skeena River Tributary,British ColumbiaAuthor(s): Paul PrinceSource: Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie, Vol. 29, No. 1(2005), pp. 68-87Published by: Canadian Archaeological AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41103517 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 13:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Canadian Archaeological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toCanadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fish Weirs, Salmon Productivity, and Village Settlement in an Upper Skeena River Tributary, British Columbia

Paul Prince1^

Abstract. A group of fish weirs at Kitwan- cool Lake in northern British Columbia, ranging in date from 770 ±40 BP to historic times, provides evidence of an intensive fishing economy, potentially exploiting at least four species of salmon. Although they are located in an ecologically vulnerable position on a single stem of the Skeena River, and modern fish stocks at the lake fluctuate significantly, I suggest that the variety of salmon entering the weir sites alleviated fluc- tuations in individual species abundance and enhanced the viability of fishing as a basis for permanent settlement. I also argue that exa- mining the relationship between intensive fishing technology and the structure of the resource contributes to our understanding of risk reduction in hunting-fishing-gathering economies in general, and of the organiza- tion of local group territories in the upper Skeena drainage in particular.

Résume. La découverte d'un ensemble de fascines ou enclos pour la pêche au lac Kitwan- cool dans le nord de la Colombie-Britannique datant de 770 ±40 BP jusqu'à la période his- torique indique une économie basée sur la pêche intensive, avec l'exploitation d'au moins quatre espèces différentes de saumons. L'en- droit sur la rivière Skeena, où se trouvent les fascines, est situé dans une position écologique vulnérable parce qu'elle se trouve sur une seul branche de la rivière, et les poissons présents dans le lac aujourd'hui fluctuent de façon importante. Je suggère que la variété d'espèces de saumon qui entraient dans les enclos aidait à diminuer les fluctuations de chaque espèce particulière et augmentait ainsi la viabilité

d'un établissement permanent à cet endroit. Je propose aussi que l'analyse de la relation entre la technologie de la pêche intensive et la structure de la ressource aide à mieux comprendre la réduction des risques économi- ques chez les chasseurs-pêcheurs-cueilleurs en général ainsi qu'elle permet en particulier de comprendre l'organisation des territoires des groupes locaux dans le haut Skeena.

PAPER REPORTS ON ARCHAEO-

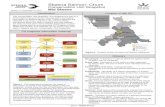

logical salmon weirs at the outlet of Kitwancool Lake, located 240 km inland on the Skeena River system in northern British Columbia (Figure 1). Historically, this area falls within the ter- ritory of the Gitanyow local group of the Gitksan. The Gitksan are a Northwest Coast culture, with an economic focus on intensive salmon fishing and storage. This economy supported large popula- tions residing in permanent planked- house villages, and making seasonal use of resource extraction sites and camps within well-defined local group and line- age ("House") territories (Cove 1982; Halpin and Seguin 1990). The position of the Gitanyow is unique among the Gitksans in that a single tributary of the Skeena - the Kitwanga River and Kitwan- cool Lake at its head - is the major area of settlement, while other historic Gitk- san villages tend towards the junctions f Department of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9J 7B8 [[email protected]]

Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29: 68-87(2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 69

Figure i. Map showing the location of the study area and ethnographic villages in northern British Columbia.

of the Skeena and its main tributaries. It has been argued that these villages were positioned to take advantage of the abundance and variety of migrating salmon in the Skeena and to control individual spawning streams (Adams 1973; Ames 1979; Morrell n.d.).

Kitwancool Lake has rich fish resources, including rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and dolly varden {Salvelinus malma), which were Aborigi- nally important (<Ksan 1980: 30), but

only salmon occur in large enough numbers to be intensively harvested and stored. Salmon may be overempha- sized in Northwest Coast archaeology and ethnography (Ames 1994; Monks 1987), but were crucially important to inland people, and are clearly the eco- nomic underpinning of Gitksan culture. Salmon, however, are subject to fluctua- tions in availability for a host of reasons, which places people dependent upon them at economic risk (Butler 2000;

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70 • PRINCE

Cannon 1996). This is a problem of broad relevance. Environmental vari- ability is commonplace, and can create uncertainty in crucial food sources (Halstead and O'Shea 1989; Wolverton 2005). A society's ability to buffer such variability is integral to its existence, and a common strategy is to use a wider range of resources (Cannon 1996; Halstead and O'Shea 1989; Wolverton 2005). A buffering mechanism taking advantage of variation between salmon populations is assumed to be built into the ethnographic Gitksan social and settlement systems.

The conventional ethnographic interpretation is that the people of the upper Skeena were successful in main- taining their economy because their local group and House territory system ensured access to the resources of vari- ous tributaries and compensated for the potentially disastrous effects of a shortfall in the fishery of a single stream. House territories are said to range up side tribu- taries, both to ensure access to all salmon species through exchange at the village and to meet the house's needs for the various other resources of the tributary valleys (Cove 1982: 4; Halpin and Seguin 1990: 271). The establishment of village sites at the Skeena's confluences and their catchment areas up side streams is thus argued to have been crucial to the successful adaptation of Northwest Coast culture to this riverine setting (Ames 1979: 230; Ives 1990).

Although the Gitanyow people's traditional house territories historically include a large part of the Nass drainage (Duff 1959; Sterrine al 1998), which reduces the risk of being dependent on a single tributary of the Skeena for salmon, the residential focus (winter vil- lages), where most salmon were stored and consumed, was on Kitwancool Lake

and the Kitwanga River. I argue from modern fisheries studies that the salmon resources there were rich enough in terms of abundance and variety to offset the potential risks of failure in an individual run. I also provide evidence from recently documented harvest- ing facilities (i.e., weirs), and historic and prehistoric village components, that - regardless of the antiquity of the details of the Gitanyow House-territory system - the salmon fishery supported long-term village settlement at the lake. This means assumptions about the basis for village settlement in the broader area derived from the ethnographic settlement system should be rethought. A single, minor tributary could and did support village settlement because it had the variety and abundance of salmon resources to do so. This may prove to be the case in other stems of the Skeena and upper Nass, once they see archaeo- logical research, and the recognition of fish weirs could be an important line of evidence.

THE KITWANCOOL LAKE SURVEY PROJECT

Settlement survey was undertaken at Kitwancool Lake in 2002 in order to pro- vide greater context for a small pithouse community, GiTa-2, dated to 490 ± 70 BP (Beta 174053) and determine how it fit within the settlement tradition of the area (Table 1; Figure 1). One of the specific objectives of the survey was to locate a previously recorded site, GiTa-1. This site on the east side of the outlet of the lake (Figure 2) was described as an historic village containing the remains of six cabins, a barn, and smokehouse (McMurdo 1975: 8). The buildings rep- resented Native use of the site for agricul- ture and fishing in the early to mid^O* century (Derrick 1977), but in Gitksan

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 71

Table i. Summary of radiocarbon dates reported in text

l4CAge Ô1SC Site Context (BP) (%c) Sample Type CalAge*(2o) Lab No.

GiTa-28 Weir stake 160±40 -25.0 Waterlogged AD 1660-1950 Beta 194850 wood

GiTa-21 Weir Stake 540±70 -25.0 Waterlogged AD 1290-1460 Beta 174051 wood

IBIllB^

GiTa-20 Adzed cedar 180±60 -25.0 Waterlogged AD 1640-1950 Beta 178280 wood

GiTa-19 Midden 2240±40 -26.6 Charred 380-170 BC Beta 194846

-y- ^^_:m3cmmm S«f - i|^^^

GiTa-19 Weir stake 50±50 -25.0 Waterlogged Outside Range Beta 194847 wood

GiTa-23 Hearth 1300±60 -25.0 Charred wood AD 640-880 Beta 174052 ♦Calibrated ages were obtained using the data set INTCAL98 (Stuiver et al 1998).

oral tradition the settlement is described as the upper end of a very large ancient village (Duff 1959: 12). Although details of the size of the village can not be taken literally, the oral traditions indicate a shift in permanent settlement from the lake, downstream to the confluence of the Kitwanga and Kitwancool Rivers (Figure 1), as a consequence of episodes of conflict with pithouse-dwelling people from the northern interior loosely referred to as the Tsetsaut (Duff 1959: 31;Sterritt et al 1998: 24). I thus wished to know if deposits contemporary with GiTa-2 were present at GiTa-1, and if a process of conflict and contraction was evident.

In the course of searching the outlet of the lake, wooden stakes were discov- ered, representing the remains of two

fish weir locations - GiTa-20 and GiTa- 21 (Figure 2). While the fish weirs do not directly inform the primary research questions of the project, they could not be overlooked as they provide evidence for the economic underpinning of North- west Coast settlement in the study area, and are associated with nearby villages. A stake collected from GiTa-21 dated to 540±70BP (Beta 178280), while the weir at GiTa-20 seemed to be historic in age, having axe-manufactured stake tips (Table 1). This weir is situated between the remains of a prehistoric village with rectangular house platforms on the west (GiTa-19), and a water-logged multi- component village (considered part of GiTa-20) dating to 540±60BP (Beta 174050) on the east. Historic GiTa-1 lies further to the east. In 2004, three other

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 • PRINCE

Figure 2. Archaeological sites recorded at the outlet of Kitwancool Lake.

fish weir locations were documented. One is directly off-shore from GiTa-19, and is multi-component with an historic fence (50±50BP, Beta 194847), and portions of an earlier fence-and-basket funnel trap dated to 770 ±40 BP (Beta 194849). The other two weirs are down- steam from GiTa-21, and samples from them date to 160 ±40 BP (Beta 194850) and 420±40BP (Beta 194851). Given the limited sampling conducted, and the common practice of repairing weirs by replacing stakes (Johnston and Cassavoy 1978: 707; Tveskov and Erlandson 2003: 1026), each of these sites could have been used for a prolonged time around these dates. As discussed below, the time span of the weirs, the amount of labour invested in their construction, and length and intensity of settlement nearby suggest a sustainable and productive fishery, despite undoubtedly unpredict- able fluctuations, and have implications

for the validity of the ethnographic model for settlement.

THE STRUCTURE OF HISTORIC FISH WEIRS

Ethnographies of the Northwest Coast describe a wide range of wooden weirs and inter-tidal stone traps used for the mass harvesting of salmon. Details of the construction and operation of wooden weirs specifically are illus- trated in Stewart (1982) and reviewed by Moss et al. (1990) and Tveskov and Erlandson (2003), who make compari- sons to inter-tidal archaeological weirs in Alaska and Oregon. A growing number of archaeological fish weirs are being recorded on coastal streams (Byram 2003; Cassavoy 2003; Eldridge and Acheson 1992; Hobler 1976; Schalk and Burtchard 2003; Seiber 2003), but little has been published on more interior, upriver wooden weirs.

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 73

Ethnographies indicate river weirs were basically systems of fences built across shallow streams. They were usually constructed of substantial stakes, driven into the river bed at roughly regular intervals, which were left in place as per- manent structures (Drucker 1963: 35; Emmons 1991: 105; Rosdund 1952: 101; Stewart 1982: 99). Downstream from these, diagonal truss-like posts often sup- ported the structure against the current (Stewart 1982: 100, 103). Spaces between the permanent support stakes could be filled with a removable lattice-work of smaller twigs or staves, fastened against the upstream end of the fence and held in place by the current (Stewart 1982: 99), and/or woven with a network of slender branches.

A wide range of variation is possible in the orientation and alignment of weir stakes based on the method of capturing migrating fish. Weirs could be arranged in parallel rows, forcing salmon to jump the downstream fence or navigate a gate and become impounded between

the two where they could be netted or speared (Stewart 1982: 106). Fish could also be netted from fixed platforms or canoes as they swam up against a single row barrier (Emmons 1991: 105; 'Ksan 1980: 30; Stewart 1982: 104). Alterna- tively to impounding fish, weirs could be arranged to direct fish towards traps, which were typically positioned at the upstream end of an opening (Emmons 1991: 105; Rostlund 1952: 101; Stewart 1982: 99, 107, 111). Traps could also be arranged to catch tired fish as they were swept back downstream. The traps themselves could be either permanent structures, built into the river bed, or removable basketry constructions of sticks or staves (Drucker 1963: 36; Stew- art 1982: 115), held in place by rocks, or lashed to posts.

A photograph taken in 1918 of a weir used by the Gitanyow in the Kitwanga River shows a single row of large stakes driven into the river bed and braced by long poles placed diagonally down- stream (Figure 3). A removable lattice

Figure 3. Fish weir and basket traps on the Kitwanga River as photographed by Louis Shotridge in 1918 (Courtesy of the Canadian Museum of Civilisation, 71-8442).

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74 • PRINCE

was held in place against the upstream side of the support stakes. This weir was used in conjunction with long basketry funnel traps, which can be seen rest- ing on the shore. Part of the lattice was probably removed to position the trap on the upstream side of the weir. These details provide clues to interpreting the archaeological fish weirs at the outlet of Kitwancool Lake.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FISH WEIRS AT KITWANCOOL LAKE

The waters at the outlet of Kitwancool Lake are very clear in mid- to late- summer, with visibility of three to four meters. Fish weirs were searched for during this season by scanning the lake and river bed through a glass viewer from a boat, and wading in the shallows. Once detected, stakes were flagged with floats and then measured and samples collected by wading and snorkeling. Their locations were plotted with a com- bination of GPS, tape-and-compass, and transit. These methods are not intended to provide an exhaustive inventory of weirs, but do provide an accurate repre- sentation of the features detected and an indication of their dates, although each could have a longer period of use. The following sites were recorded in this manner.

GiTa-28 This site is situated 500 meters down- stream from the lake, at a point where the outlet narrows to a shallow river 1.25 to 0.5 meters deep (Figure 2). The river bed is active here, with shifting sand bars that have both damaged and obscured the weir. Eleven long, slender dislodged stakes were mapped, ranging from 3-5 cm in diameter by 20-100 cm in length, along with several cut branches from its woven fabric and the nubs of

four in-situ stakes, but no pattern was detected in their distribution. One of the dislodged stakes dates to 160 ±40 BP (Beta 194850). This specimen has a very large 2-sigma-calibrated age range, AD 1660-1950, and could be historic (Table 1). However, since the stake tips lack the distinctive metal tool marks visible on recent specimens, the late prehistoric to protohistoric part of this age range seems likely.

GiTa-29 Site GiTa-29 is upstream from GiTa-28 at the first constriction in the Kitwanga River in 1 to 1.5 meters of water. A small logjam had formed at this point, and six dislodged stakes and one in-situ stake were visible on the river-bottom. The dislodged stakes were very long and slender (4 cm in diameter by 60-220 cm in length). The sharpened ends of the stakes lack clear tools marks, but are uniformly worked to a dull tip. A section of one dates to 420±40 BP (Beta 194851, Table 1).

GiTa-21 GiTa-21 is located 70 meters above GiTa- 29 (Figure 2). The weathered nubs of 37 stakes were observed protruding from the river bed in water that measured 1-1.3 m deep in late-summer. Two addi- tional stakes were dislodged and could be seen lying on the river bed, along with several slender curved branches with cut ends. The tips of these stakes are eroded, but lack cut marks indicative of working with metal tools (Figure 4) . The dislodged stakes are 7 cm in diam- eter, and (although not measured) the in-situ stakes seem to be about the same thickness. Most are the remains of the permanent upright posts of a weir fence. A very stout stake (18 cm diameter) was discovered dislodged downstream.

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 75

If associated with the weir, it may have been a brace. The cut branches probably were part of the fabric of the weir. One of the dislodged stakes in the fence row was collected, and radiocarbon dated to 540±70BP (Beta 174051).

The distribution of stakes is obscured by a thick weed-bed near the eastern shore, but the weir can be projected to have spanned the entire river (Figure 5). The map shows the weir fence trending northwest, rather than precisely per- pendicular to the shoreline. This may, in part, be an adaptation made by the builders to the configuration of the river bed and the depth of water, but is also exaggerated by our mapping procedures, which saw floats positioned above the weir stakes on a day when the prevailing wind was northward. Most of the stakes to the north (upstream) are vertical, while those to the south tend to be angled towards them and are probably down-

stream braces. The weir was thus prob- ably a single row of permanent upright stakes, trending slightly northwest across the river, with supports arranged down- stream. It is difficult to determine the locations of openings, but a break in a cluster of stakes near the eastern shore may represent one such position.

GiTa-20 Located just below the outlet of Kitwan- cool Lake (Figure 2), this site includes the remains of a fish weir in the river bed, two stratified waterlogged occu- pation components on the eastern shoreline, and an historic agricultural component in an open meadow to the east (Figure 6). A high terrace on the western shore contains the prehistoric settlement GiTa-19, which seems associ- ated with an earlier weir upstream.

The weir at GiTa-20 has been badly disturbed by use of the site as a boat

Figure 4. Dislodged stakes at GiTa-21.

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

76 • PRINCE

Figure 5. Map of site GiTa-21.

Figure 6. Map of site GiTa-20.

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 77

launch, ice scour, and beaver activity, with stakes being incorporated into the fabric of a nearby beaver lodge. As a result, most of the stakes have been dislodged and lie on the river bottom. These stakes have tips with large, angu- lar scars indicative of manufacture with a metal axe (Figure 7) . An axe handle, and various other items of European manufacture were observed among the stakes. Although the weir would seem to be primarily historic in age, a relatively long sequence of occupation was discov- ered on the adjacent eastern shore.

The stakes at GiTa-20 are comparable in size to the prehistoric stakes at GiTa- 21, ranging from 5 to 10 cm in diameter. Details of the weir's configuration, and operation, however, are impossible to reconstruct because of the amount of disturbance, and perhaps periodic reju- venation. This could account for the tight, irregular clusters of in-situ stakes

near the eastern shore. A pile of stones was also noted at the eastern end of the weir, and this may have helped support a platform for spearing or netting fish, or for hauling traps out of the water.

GiTa-19 Remnants of at least two weirs are evi- dent at GiTa-19. One spans the outlet of the lake in 2.5-1.42 meters of water and is in excellent condition, but obscured by water lilies. Thirty-eight in-situ stakes were visible, including two tight clumps (Figure 8). All of these stakes are slender and upright. A section of one dates to 50 ±50 BP (Beta 195847), indicating his- toric period construction. Downstream braces are not readily apparent and may not have been necessary as the current in the deep water is slow.

There are several dislodged stakes, the remains of a collapsed basket funnel trap, and a few in-situ stakes a short

Figure 7. Dislodged stake at GiTa-20 showing axe sharpened tip.

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

78 • PRINCE

Figure 8. Map of the fish weir at site GiTa-19.

distance downstream in 1.97 meters of water (Figure 9). These represent the fragmentary remains of an earlier weir. The trap consists of more than 75 staves of cedar, up to 2 meters in length, and a number of shorter pieces. A sample from the trap dates to 770±40BP (Beta 194849, Table 1).

TERRESTRIAL COMPONENTS Immediately to the east of the weirs is a large clearing formerly used for pasture and cultivation. It was burned over in the 1980s and is currently cov- ered in a dense growth of fîreweed. The remains of the buildings recorded by McMurdo (1975: 8) as GiTa-1 are located somewhere in this clearing, per- haps 200 meters from shore, but eluded our detection due to the vegetation, a heavy overburden of floodplain silt, and deep cultivation. Nonetheless, several

wire nails, one machine-cut nail, fence wire, and pieces of agricultural imple- ments (including a hay mower, horse harness, and shovel) were recovered on a terrace at the eastern edge of GiTa-20, and reflect the agricultural use of the area.

Test pitting a slumped bank adjacent to the water at GiTa-20 revealed two water-logged components. The presence of the later component was first indicated by mortise-and-tenon shaped cedar tim- bers protruding from the bank into the water. Shovel testing indicated an exten- sive deposit of hand-adzed cedar pieces beneath the current sod line. A sample of this material returned a radiocarbon date of 180±60 BP (Beta 178280). The calibrated 2-sigma-range, AD 1640-1950 (Table 1), indicates it has a likelihood of being historic in age. We also recovered short sticks with sawn ends and shaved

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 79

Figure 9. Collapsed basket trap lying on the lakebed at GiTa-19.

circumferences, and short staves of cedar, with one convex surface and one flat surface. These carefully shaped pieces of cedar may represent the remains of wooden traps, drying racks, or a weir lattice. The larger pieces of adzed cedar and the architectural members may rep- resent a boardwalk in front of a village, parts of planked houses, or a smoke- house. McMurdo (1975: 8) indicated a smokehouse still stood in the general area in the 1970s. Below these materials were layers of peat and sedge. A second deposit of water-logged adzed cedar fragments rests on a buried sod. This lower component yielded a radiocarbon date of 540 ±60 BP (Beta 174050) from a sample of worked cedar, and probably represents the remains of an earlier vil- lage. It is contemporary with the weir downstream at GiTa-21, but whether GiTa-20 was also used as a fishing site at this time is uncertain.

Shovel testing of the eastern shore adjacent to the weir at GiTa-21 pro- duced a single burned mammal bone. Further evidence of settlement or pro- cessing areas associated with this weir may have escaped detection due to the heavy overburden of cultivated soil. The terrain on the western shore is extremely steep and is unlikely to have been the primary means of access to the weir. This topography extends southward to the weirs at GiTa-28 and GiTa-29, where no test pitting was conducted.

The village on the western bank of the outlet, GiTa-19, is a multi-com- ponent prehistoric settlement. Shovel testing identified a thin midden deposit, 10-35 cm thick, fronting the edge of the river terrace for a distance of 80 meters. Midden deposits are deepest towards the south end of the site, where a sample of charred wood from the basal layer returned a date of 2240 ±40 BP

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

80 • PRINCE

(Beta 194846), and a sample associ- ated with a dense layer of bone dates to 1500±50 BP (Beta 196684, Table 1). The terrace descends in elevation towards the north of the site in a series of five step-like gradations, forming rectangu- lar platforms of level ground fronting the river, typical of planked houses. Test excavations recovered a large quantity of faunal remains, fire-cracked-rock, various lithic raw materials, and archi- tectural features suggesting a substantial prehistoric village occupation. A sample of charred cedar timbers from the upper layer on one of the platforms yielded a date of 320±30 BP (Beta 194845, Table 1). Although these dates are not contemporary with those from the weirs, further sampling of both the weirs and the intervening occupation layers at GiTa-19 may prove them to be directly associated.

At present, there is little faunal evi- dence for salmon fishing at GiTa-19. The faunal assemblage is highly fragmented, and salmon bone is semi-cartilaginous and subject to more rapid destruction than denser bone (Butler and Chatters 1994), especially in non-shell midden contexts on the Northwest Coast. The Gitksan are also reported to have ritually disposed of salmon bone in fire or water to propagate the species, which could also bias recovery rates. Nonetheless, small quantities of salmon vertebrae frag- ments have been recovered from bulk samples associated with the 320 ±30 BP and 1500 ±50 BP dates, and intervening layers. While the contribution of salmon to the economy of the village cannot be quantified from these remains, the mere presence of salmon, and the position of this village at a prime salmon fishing location is surely not coincidental, and it was likely supported by the fishery throughout its occupation.

MODERN SALMON RESOURCES AT KITWANCOOL LAKE

Data on salmon runs in the Kitwancool Lake drainage have been collected by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans since 1950, and by the Gitanyow Fisheries Authority since 2001. These combined data indicate that the Kitwanga drainage is a very rich salmon spawning habitat. All six species of Pacific salmon - pink (O. gorbuscha), sockeye (O. nerka), chi- nook (O. shawytscha), coho (O. kisutch), chum (O. keta) and steelhead (O. Onco- rhynchus mykiss) - ascend the Kitwanga River to reach their spawning grounds.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans salmon escapement figures indicate the modern pink salmon run in the Kit- wanga River is one of the largest in the entire Skeena River system. These fish display a bimodal distribution in abun- dance, with a very high overall mean (Table 2). Pink salmon typically spawn in lakes and streams fed by lakes. Most of these fish pass through the weir sites at the outlet of Kitwancool Lake, where the Gitanyow Fisheries Authority (GFA) has observed them from early-mid August (Mark Cleveland, pers. comm. 2003). Sockeye spawn in rivers that feed lakes, and have been seen at Kitwancool Lake in late July-early October. Coho gener- ally spawn in smaller streams, and ascend to the creeks and wetlands above Kitwan- cool Lake, at the end of September (GFA 2004). Steelhead enter the lake over sev- eral months, beginning in August, over- winter there and leave in February, but there are no reliable estimates of their numbers. Chinook also have a long run, spawning between May and September, and are most abundant in mid-August. They have been observed one kilometer below Kitwancool Lake (GFA 2004). This is close to GiTa-28, but whether Chinook populations ever reached the

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 81

Table 2. Average salmon escapements, 1950-2004, and spawning seasons.

Species Range Std. Dev. Mean Spawning Season Pink Overall 5,000-400,000 92,422.52 139,477.77 Early-mid August Odd Years 15,000-400,000 95,016.24 167,909.09 Even Years 5,000-300,000 82,973.55 112,282.60 Chinook 0-2,500 550.67 379.22 May-September Coho 0-3,500 739.24 650.00 Late September Sockeye 0-3,126 640.00 267. 1 0 Late July-Early Oct

weirs is uncertain. Chum salmon prefer to spawn in small side streams and chan- nels duringJuly-August. They have been observed four kilometers below Kitwan- cool Lake (GFA 2004), peaking at the end of August to mid-September.

If earlier salmon populations and spawning behaviours were comparable, the fish weirs at Kitwancool Lake were able to take four species of salmon -

pink, sockeye, coho, and steelhead - from July through to early October, and may have had access to chinook as well during these months. Of these fish, sockeye is the most prized by modern Native fishermen for its high fat content and firm flesh, followed by coho and chinook. Chum and pink salmon ranked lowest on the Gitksan's traditional food scale ('Ksan 1980: 30), but are easily dried and a valuable stored resource (Ames 1979: 226). All species were thus economically important (Halpin and Seguin 1990: 271).

While the modern salmon stocks of the lake present a rich, and seasonally clumped resource, the individual species are not uniformly abundant, either on average, or from year to year (Table 2). Escapement figures display extreme fluc- tuations in the size of individual species runs. This may be influenced by a host of poorly understood modern variables, but prehistoric salmon stocks can also be expected to have fluctuated. This under-

lines the importance of having access to, and harvesting all available species (Halpin and Seguin 1990: 271).

Pink salmon were likely a mainstay, to judge from their fairly constant high modern escapements (Table 2), but if they were the only species present, people would be at the risk of a dra- matic resource crash. The economically prized sockeye occur in consistently modest numbers with severe spikes during exceptionally poor and good years (Cox-Rogers 2004; DFO 2003). Interestingly, Gitanyow Fisheries Author- ity habitat studies estimate the produc- tivity of the drainage should yield an escapement of 25,000-75,000 sockeye per year (GFA 2002), despite pressures from commercial and sport fishing, yet they continue to oscillate (Kingston and Williams 2004). Whether the system produced such numbers in pre-contact times is uncertain, but it is apparent the resource is sensitive and may have been richer. If sockeye stocks were generally moderate-sized in prehistory as well, the effects of fluctuations may have been amplified for human fishers. However, short falls in a sockeye run could have been compensated for with other spe- cies reaching the lake. If they did not reach the weir, chinook and chum could have been captured a short distance downstream to round out the variety of salmon and provide further insurance of

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82 • PRINCE

winter stores. This tendency for modern fish stocks to fluctuate independent of one another, and the likelihood that prehistoric resources fluctuated too, suggests to me that the variety of salmon species available at the outlet of the lake, and not just the abundance of individual runs, made this a viable location for intensive harvesting facilities and perma- nent settlement.

DISCUSSION Some ecologically oriented ethnogra- phers, such as Piddocke (1965), have argued that variability in the abundance of salmon resources in the Pacific North- west explains the potlatch as a resource circulating mechanism. Adams (1973: 90) joined a number of ethnographers who questioned the severity of salmon resource variation, and argued the Gitksan House-territory system provided insurance against resource shortages. This kind of thinking became pervasive, with many archaeologists and ethnog- raphers in the 1960s to 1990s assuming salmon were an inexhaustible and abun- dant resource that "permitted" intensive exploitation and storage and inevitably led Northwest Coast people to evolve complex sedentary societies (Drucker 1963: 7; Kew 1992; Matson 1983; Matson and Coupland 1995; Moss and Erlandson 1990: 143, 153). Variability was down- played, except for a general dichotomy in the abundance and distribution of the resource between the northern and southern Northwest Coast, which may have influenced the scale and intensity of use and ownership of salmon steams (Matson 1985; Suttles 1987; Schalk 1981). Donald and Mitchell's (1975) correlation of Kwakiutl local group rank- ing and the productivity of their salmon streams, also emphasizes geographic, rather than temporal variability.

More recent zooarchaeological research has pointed out a high degree of variation in Northwest Coast econo- mies and their degree of reliance on salmon (Ames 1994; Cannon 1995; Monks 1987; Moss 1993), as well as tem- poral fluctuations in salmon abundance, and a need for long-term management of resources and flexibility in economic strategies (Butler 2000; Cannon 1996, 1998, 2000; Yang et al 2004). These observations relate to recent interpreta- tions of hunter-gatherer economic risk reduction strategies in broader contexts (Halstead and O'Shea 1989; Wolverton 2005), which emphasize the ameliorat- ing benefits of a varied resource base when experiencing environmental fluctuations. Fish biology research is also raising our awareness of the ten- dency for salmon stocks to fluctuate and the complexity of factors influenc- ing them (Beamish et al. 1995; Miller 2000; Tadokoro et al 1997; Waples et al 2001). This makes understanding the settlement strategies employed in inte- rior parts of the Northwest Coast that lacked abundant, storable resources other than salmon all the more impor- tant, especially where the residential focus was on a single stream. This situation is not adequately explained by the literature on the ecology of the Gitksan settlement system that Ames (1979) and Cove (1982) built upon Adams' work, which emphasizes that resources from a variety of watersheds were required.

In the case of Kitwancool Lake, modern salmon populations fluctuate significantly. Although modern industry and commercial fishing may amplify the degree of variability, we can expect the resources fluctuated in the past too. In a good year, there may be more than enough of any single species of

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 83

salmon to support a large village. If the watershed lacked variety in salmon spe- cies, however, and one of the periodic crashes occurred, the economy would be placed in an unstable position. I argue, therefore, that the risks associated with such fluctuations were lessened by the variety of salmon at Kitwancool Lake. Flexibility in salmon use is, of course, only possible barring some catastrophic event, including over-fishing at the weirs, affecting the entire watershed and all of its salmon populations. In such a case, people would need to take short-term measures to compensate for the shortfall (Cannon 1996; Butler 2000), such as fishing another watershed, trade, raid- ing, or using low-yield resources while waiting for the salmon to rebound. The presence of historic and prehistoric villages at Kitwancool Lake and fixed intensive harvesting technology requir- ing considerable investment in manufac- ture and maintenance, however, suggests the fishery was sufficient to compensate for fluctuations and sustain settlement. I have also argued (Prince 2004) that a pattern of ridge-top caching of salmon at the lake, and the presence of a lookout platform extending back to 1300 ±60 BP (Beta 174052, Table 1), are indirect indications of the value and antiquity of the fishery, and of a perceived need to defend it and the settlements it sup- ported. Storage would have been of special importance at Kitwancool Lake because of the relatively short duration of salmon spawning, despite the abun- dance and variety of species.

CONCLUSIONS The fish weirs recorded at Kitwancool Lake were permanent structures whose core was a wooden fence. Although four of the six weirs are in poor condition, each probably operated in conjunction

with a removable lattice and basket traps or nets. Taken together, the weirs pro- vide direct evidence for intensive har- vesting of salmon from 770 BP to historic times. There may have been episodes of rejuvenation at the recorded sites, and other, even earlier weirs may have gone unpreserved, or undiscovered. It is thus likely that the outlet of the lake saw intensive salmon fishing for a much longer time.

Due to poor conditions of fish bone preservation, limited archaeological excavation, and technical difficulties in the precise identification of salmon species (Cannon 1988; Yang et al. 2004), it is presently not certain unequivocally which species were harvested at the weir sites. Fisheries studies, however, indicate four species of salmon pass through the weir locations today, with pink salmon being particularly abundant. While indi- vidual stocks have been demonstrated to fluctuate, the variety and abundance of salmon at the outlet made it a viable position for the operation and mainte- nance of harvesting facilities. This har- vesting strategy was sufficient to support long-term substantial settlements at the outlet of the lake (GiTa-1, GiTa-19, and GiTa-20), and may have yielded surplus stores that people felt worth taking extra measures to conceal and protect (Prince 2004). Documenting the fishing facilities at the outlet of the lake in the context of the modern salmon popu- lations available helps to explain the seemingly anomalous residential focus of ethnographic and prehistoric settle- ment there, despite its tenuous position on a single stem of the Skeena. There are, thus, potentially more locations that could support intensive settlement than could be predicted from the ethnogra- phy of the upper Skeena alone. These observations also suggest that seeking

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84 • PRINCE

diversity in staple resources, rather than strictly abundance, is an effective risk reduction strategy in hunting-fishing- gathering settlement systems in general.

Acknowledgments. This research has been funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Regular Grant. I thank Sandra Sisson of the Trent University Finance Office for administering the funds. The research was also made possible with the cooperation of Chief Philip Daniels and the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs Office. I thank my field crews: Waylon Daniels, Tyson Dan- iels, Sheri McLean, Kerby Goode, Shannon Taylor, Nathan Contant, and Doug Nixon, and lab assistants, Adam Menzies, Krissy Graham, Katie Miles, Laura Kake and Robin Walton. I greatly appreciate the helpful com- ments made on earlier drafts of this paper by Aubrey Cannon and Susan Jamieson. The editor and reviewers of the Canadian Jour- nal Archaeology also suggested changes that improved this paper. The French translation of the abstract was provided by Christiane Leroux. I also thank Mark Cleveland of the Gitanyow Fisheries Authority for information on modern fish stocks and habitats and Gayle Mclntyre of Fleming College for the conser- vation of water-logged materials. Finally, this research would not be possible, or enjoyable, without the understanding and support of my family, Christiane and Nicholas.

REFERENCES CITED Adams, J. 1973 The Gitksan Potlatch: Population Flux, Resource Ownership and Reciprocity. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Toronto.

Ames, K. 1979 Stable and Resilient Systems Along the Skeena River: The Gitk- san/ Carrier Boundary. In Skeena River Prehistory, edited by R. Inglis and G. MacDonald, pp. 219-243. National

Museum of Man, Mercury Series Paper No. 87, Ottawa.

1994 The Northwest Coast: Complex Hunter-Gatherers, Ecology, and Social Evolution. Annual Review of Anthropol- ogy 12: 1-40.

Beamish, R., C. Neville, B. Thompson, P. Harrison, and M. St. John 1995 A Relationship Between Fraser River Discharge and Interannual Production of Pacific Salmon and Pacific Herring in the Strait of Geor- gia. Océanographie Literature Review 42: 1136.

Butler, V. 2000 Resource Depression on the Northwest Coast of North America. Antiquity 74: 649-661.

Buder, V., and J. Chatters 1994 The Role of Bone Density in Structuring Prehistoric Salmon Bone Assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Science 21: 413-424.

Byram, S. 2003 The Economic Context of Tidewa- ter Weir Fishing on the Oregon Coast Paper Presented at the 10th Internation- al Meeting of the Wetlands Archaeology Research Project, Olympia.

Cannon, A. 1988 Radiographie Age-Determina- tion of Pacific Salmon Species and Seasonal Inferences. Journal of Field Archaeology 15: 103-108.

1995 The Ratfish and Marine Resource Deficiencies on the North- west Coast. Canadian Journal of Archae- ology 19: 49-60.

1996 Scales of Variability in North- west Salmon Fishing. In Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherer Fishing Strategies, edited by M. Plew, pp. 25-40. Boise State University, Boise.

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 85

1998 Contingency and Agency in the Growth of Northwest Coast Maritime Economies. Arctic Anthropology 35: 57-67. 2000 Assessing Variability in North- west Coast Salmon and Herring Fish- eries: Bucket-Auger Sampling of Shell Midden Sites on the Central Coast of British Columbia. Journal of Archaeo- logical Science 27: 725-737.

Cassavoy, K. 2003 Kennedy Lake Prehistoric Fish Weir: Project Report 2002. Report to Pacific Rim National Park, Torino, British Columbia.

Cove,J 1982 The Gitksan Traditional Con- cept of Land Ownership. Anthropo- logica 24: 3-17.

Cox-Rogers, S. 2004 Skeena Sockeye Review. Paper Presented at the 2004 Northern Fisheries Review Symposium, Prince Rupert, B.C.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) 2003 Salmon Management Records, 1950-2003. Report on File at Depart- ment of Fisheries and Oceans, Prince Rupert, B.C.

Derrick, M. 1977 Kitwancool Lands Research. Report to the Minister of Indian Affairs, November 7, 1977, Kitwan- cool, British Columbia.

Donald, L., and D. Mitchell 1975 Some Correlates of Local Group Rank Among the Southern Kwakiutl. Ethnology 14: 325-346.

Drucker, P. 1963 Indians of the Northwest Coast. Natural History Press, New York.

Duff, W. 1959 Histories, Territories and Laws of the Kitwancool British Columbia Provincial Museum Memoir No. 4, Virtnria

Eldridge, M., and S. Acheson 1992 The Antiquity of Fish Weirs on the Southern Coast: A Response to Moss, Erlandson and Stuckenrath. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 16: 112-116.

Emmons, G. 1991 The Tlingit Indians. Douglas and Mclntyre, Vancouver.

Gitanyow Fisheries Authority (GFA) 2002 Sockeye Stocks in the Kitwanga River System. Aboriginal Fisheries Jour- nal, June 2002: 5. 2004 Salmon Habitats in Gitanyow House Territories. Map on File at the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs Office, Kitwancool, British Columbia.

Halpin, M., and M. Seguin 1990 Tsimshian Peoples: Southern Tsimshian, Coast Tsimshian, Nishga and Gitksan. In Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7, Northwest Coast, edited by W. Suttles, pp. 267- 284. Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

Halstead, P., andJ.M. O'Shea 1989 Bad Year Economics: Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hobler, P. 1976 Wet Site Archaeology at Kwatna. In The Excavation of Water-Saturated Archaeological Sites, Wet Sites, on the Northwest Coast of North America, edited by D. Croes, pp. 146-157. National Museum of Man, Mercury Series Paper No. 50. Ottawa.

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86 • PRINCE

IvesJ. 1990 A Theory of Northern Athapaskan Prehistory. Westview Press, Colorado.

Johnston, R., and K. Cassavoy 1978 The Fish Weirs at Atherly Nar- rows, Ontario. American Antiquity 43: 697-709.

Kew, M. 1992 Salmon Availability, Technology and Cultural Adaptation in the Fraser River Watershed. In A Complex Culture of the British Columbia Plateau: Tradi- tional StVatVimx Resource Use, edited by B. Hayden, pp. 177-221. UBC Press, Vancouver.

Kingston, D., and B. Williams 2004 The 2004 Kitwanga River Sock- eye Story. Paper Presented at the 2004 Northern Fisheries Review Sympo- sium, Prince Rupert, B.C.

'Ksan, People of 1980 Gathering What the Great Nature Provided: Food Traditions of the Gitksan. Douglas and Mclntyre, Vancouver.

Matson, R. G. 1983 Intensification and the Devel- opment of Cultural Complexity: The Northwest versus the Northeast Coast. In The Evolution of Maritime Cultures on the Northeast and Northwest Coasts of North America, edited by R. Nash, pp. 125-148. Simon Fraser University Archaeology Press Publication No. 11, Burnaby, B.C.

1985 The Relationship Between Sed- entism and Status Inequalities Among Hunter-Gatherers. In Status, Structure and Stratification: Current Archaeological Reconstructions, edited by M. Thomp- son, M. Garcia and F. Kense, pp. 245- 252. Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary, Calgary.

Matson, R.G., and G. Coupland 1995 The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast. Academic Press, San Diego.

McMurdo,J. 1975 Archaeological Resources and Culture History in the Kitwanga-Mezia- din Corridor. Report to the British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria.

Miller, K. 2000 Pacific Salmon Fisheries: Cli- mate, Information and Adaptation in a Conflict Ridden Context. Climatic Change 45: 37-61.

Monks, G. 1987 Prey as Bait: The Deep Bay Example. Canadian Journal of Archaeol- ogy 11: 119-142.

Morrell, M. n.d. Fieldnotes on Gitksan Fishing Stations. Report on file with the Gitk- san-Wetsuweten Tribal Council, Hazel- ton, British Columbia.

Moss, M. 1993 Shellfish, Gender and Status on the Northwest Coast: Reconciling Archaeological, Ethnographic and Ethnohistorical Records of the Tlingit. American Anthropologist 95: 631-652.

Moss, M., J. Erlandson, and R. Stuckenrath 1990 Wood Stake Weirs and Salmon Fishing on the Northwest Coast: Evi- dence From Southeast Alaska. Cana- dian Journal of Archaeology 14: 143-158.

Piddocke, S. 1965 The Potlatch System of the Southern Kwakiutl: A New Perspec- tive. Southwest Journal of Anthropology 21: 244-264.

Prince, P. 2004 Ridge-Top Storage and Defen- sive Sites: New Evidence of Conflict

Canadian Journal of Archaeology 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FISH WEIRS, SALMON PRODUCTIVITY, AND VILLAGE SETTLEMENT • 87

in Northern British Columbia. North American Archaeologist 25: 35-56.

Rostlund, E. 1952 Fresh Water Fish and Fishing in Native North America. University of California Publications in Geography 9.

Schalk, R. 1981 Land Use and Organizational Complexity Among Foragers of Northwestern North America. Senri Ethnological Studies 9: 53-75.

Schalk, R., and G. Burthchard 2003 The Newskah Fish Trap Com- plex, Grays Harbour, Washington. Paper Presented at the 10th Inter- national Meeting of the Wetlands Archaeology Research Project (WARP), Olympia, WA.

Seiber, F. 2003 Inventorying Fish Traps and Wet Sites in the Cheewhat River, Ditidaht Territory. Paper Presented at the 10th International Meeting of the Wet- lands Archaeology Research Project (WARP), Olympia, WA.

Stewart, H. 1982 Indian Fishing: Early Methods on the Northwest Coast. Douglas and Mclntyre, Vancouver.

Sterritt, N., S. Marsden, R. Galois, P. Grant, and R. Overstall 1998 Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed. UBC Press, Vancouver.

Suttles, W. 1987 Variation in Habitat and Culture on the Northwest Coast. In Coast

Salish Essays, pp. 26-44. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Tadokoro, K., Y. Ishida, and N. Davis 1997 Change in Chum Salmon Stom- ach Contents Associated With Fluctua- tions in Pink Salmon Abundance in the Central Subarctic Pacific and Ber- ing Sea. Océanographie Literature Review 44: 61.

Tveskov, M., and J. Erlandson 2003 The Haynes Inlet Weirs: Estua- rine Fishing and Archaeological Site Visibility on the Southern Cascadia Coast. Journal of Archaeological Science 30: 1023-1035.

Waples, R.S., R.G. Gustafson, L.A. Weitkamp, J. Myers, O.Johnson, P. Busby, J. Hard, G. Bryant, F. Waknitz, and K. Neely 2001 Characterizing Diversity in Salmon From the Pacific Northwest. Journal of Fish Biology 59: 1-41.

Wolverton, S. 2005 The Effects of the Hypsithermal on Prehistoric Foraging Efficiency in Missouri. American Antiquity 70: 91-106.

Yang, D., A. Cannon, and S. Saunders 2004 DNA Species Identification of Archaeological Salmon Bone From the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Journal of Archaeological Science 31: 619-631.

Manuscript received October 4, 2004. Final revisions February 24, 2005.

Journal Canadien d'Archéologie 29 (2005)

This content downloaded from 62.122.72.20 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 13:45:24 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions