First parturition of tigers in a semi-arid habitat, western India

Transcript of First parturition of tigers in a semi-arid habitat, western India

SHORT COMMUNICATION

First parturition of tigers in a semi-arid habitat, western India

Randeep Singh & Paul R. Krausman & Puneet Pandey &

Qamar Qureshi & Kalyanasundaram Sankar &

Surendra Prakash Goyal & Anshuman Tripathi

Received: 14 August 2013 /Revised: 11 November 2013 /Accepted: 17 November 2013# Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013

Abstract Long-term data of large felids is important tounderstand their reproductive biology and behavior foreffective conservation planning. We used camera trapdata and direct sightings from 2005 to 2013 to estimatethe age of the first parturition of Bengal tigers(Panthera tigris ) in a semi-arid habitat in India. Wemonitored 11 females in the Ranthambhore TigerReserve (RTR) from when they were 2–6 months old.The mean age at first reproduction (impregnation lead-ing to cubs) was 51.3±(SE) 4.5 months. The tigerpopulation in RTR is an important source populationand genetic pool in the western most distribution oftiger. Thus, continuous monitoring of tiger populationsis important to develop an understanding of reproduc-tive biology.

Keywords Camera trap . Cubs . India . Ranthambhore TigerReserve . Tiger . Reproductive biology

Introduction

The knowledge of reproductive parameters (e.g., the age atfirst reproduction, reproductive rate, litter size, and interbirthinterval) are fundamental for managing wildlife, especially forcarnivores with low reproductive rates (Carter et al. 1999).Reproductive data collected over long periods are required forconservation planning of endangered species (Kelly 2001;Balme et al. 2012). Reproductive parameters are importantindicators also to detect the lineage persistence in a population(i.e., lineage loss, individual fitness, population viability;Kelly 2001). Gompper et al. (1997) suggested that lineagepersistence is inversely related to age at first reproduction of aspecies and can be used to calculate rate of lineage loss pergeneration and generation timings (i.e., the average spanbetween the birth of individuals and the birth of their off-spring). The importance of lineage and heterozygosity loss innatural populations has been identified as important for con-servation when considering risks (Shaffer 1981). Small andisolated populations (<50 individuals) are vulnerable to suchlosses (i.e., genetic viability) if matriline losses are excessive;genetic diversity may be lost at a much more rapid rate insmall and isolated populations than expected (Berger andCunningham 1995).

The tiger (Panthera tigris) is an endangered and umbrellaspecies and their populations continue to decline at a fasterrate than at any time in their history (Seidensticker et al. 1999;Dinerstein et al. 2007). The knowledge of reproductive pa-rameters of wild tigers is poorly understood (Kerley et al.2003) and research on reproductive ecology of wild tigerpopulations has received very little attention in Indian-subcontinent (Sunquist 1981; Chundawat et al. 2002; Singhet al. 2013a); more literature is available in the Russian range.The western most distribution of the surviving tiger’s range isin Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve (RTR), India, which is isolat-ed and limited to 344 km2 of forests, with a population of <50

Communicated by C. Gortázar

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article(doi:10.1007/s10344-013-0784-x) contains supplementary material,which is available to authorized users.

R. Singh (*) : P. Pandey :Q. Qureshi :K. Sankar : S. P. GoyalWildlife Institute of India, Post Box #18,Dehradun 248001, Uttrakhand, Indiae-mail: [email protected]

P. R. KrausmanBoone and Crockett Program in Wildlife Biology Program,University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA

A. TripathiNMDC Limited, Dantewada 494556, Chhatishgarh, India

Eur J Wildl ResDOI 10.1007/s10344-013-0784-x

individuals (Jhala et al. 2011). Our objective was to gatherinformation about reproductive parameters of Bengal tigers,especially the age of first reproduction.

Materials and methods

Study area

Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve (25°54′ to 26° 12′N and 76°22′to 76°39′E) is situated in the semi-arid part of western India.The vegetation of RTR corresponds to those of northerntropical dry deciduous forests and the northern tropical thornforest (Champion and Seth 1968). The region receives anaverage annual rainfall of 800 mm, and temperatures can below as 2 °C in January and as high as 47 °C in May. Theterrain is highly undulating; the elevation gradient is from 200to 500 m. Other than tiger, large predators include the leopard(Panthera pardus), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus ), and stripedhyaena (Hyaena hyaena). The wild prey of the tiger consistsof the chital (Axis axis ), sambar (Rusa unicolor ), nilgai(Boselaphus tragocamelus ), chinkara (Gazella bennettii ),and wild pig (Sus scrofa ). The RTR consists of two manage-ment units: a core area which includes RanthambhoreNational Park (392 km2) and a buffer area including SawaiMann Singh (330 km2) and Kailadevi (KD, 672 km2) wildlifesanctuary (Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Fig. S1).

Data collection

We monitored the tiger population in RTR through cameratraps (1 camera trap/km2) in the core area from April 2005 toJune 2011 (ESM Fig. S1). We established a database of 647photo captures of 22 female tigers in RTR from April 2005 toJune 2011 (Singh et al. 2011, 2013a, b). From this database,we identified the distribution ranges of individual femaletigers, which allowed us to collect information about thereproductive parameters of 15 breeding female tigers (i.e.,litter size, interbirth interval; Singh et al. 2013a) and theapproximate home ranges of individual female tigers.

The dataset (i.e., photographs) of individual tigers collectedfrom the reserve authorities and tourist guides who regularly(twice in a day) visit the tiger reserve was also compiled. Thescanty vegetation and a good road network in RTR providedideal conditions for tiger sightings. Females are philopatricand likely remain in the same areas for their entire life, whilemales often disperse from their natal ranges (Smith et al.1987). Our long-term monitoring project ended in December2011 but, thereafter, sighting records, individual photographsof tigers, mating pair photographs, and females with cubsfrom the reserve management authorities and individualguides and drivers was regularly collected. We used thisinformation to reconstruct life histories of individual tigers

in RTR. Since these data were gathered frommultiple sources,the identity of individual tigers was also confirmed throughour photographic dataset of tigers using unique coat patternsfor identification (Karanth 1995).

Age at first parturition

We used photos from camera traps and direct sightings fromApril 2005 to May 2013 to estimate the age at first parturitionfor female tigers. The age at primiparity was only estimated forfemales that were monitored since they were cubs (months old).Maternity was confirmed by seeing a mother with her cubs inphotographs that could be matched to photographs within ourdataset. Knowing the exact age of cubs in free-ranging tigers aredifficult to determine, therefore, the breeding month for eachfemale tiger (those who were born during our study period) wasestimated by back dating (i.e., 2 months from the first appear-ance of cubs because tiger cubs start moving with their motherwhen they are 2 months old; Smith et al. 1987). One femaledied due to cardiac attack and three females were translocated toSariska Tiger Reserve (STR). The translocated females in STRwere monitored using radiotelemetry and camera traps.

Results

We conducted 12 camera trapping sessions from 2005 to 2011that included 33,340 trap nights (Singh et al. 2013a) and wealso compiled 171 photograph of female tigers from differentsources during 2011–2013. Eleven females were monitoredsince they were cubs (2–6 months old; Table 1). The remain-ing seven female tigers survived through the study and hadtheir first litter. The minimum age at which one of the femalescopulated (TF-11) for the first time was 33 months, and sixfemales gave birth by the time they were more than 48 monthsof age (Table 1). One female (TF-37) died at 63 months butdid not breed. The mean age of females at first parturition was51.3±4.5 months. The maximum age at which a female tigerstarts breeding in semi-arid habitat of RTR was 66 months.

Discussion

Smith and MacDougal (1991) observed the mean age of firstreproduction of female tigers at 40.8 months (n =5) in Nepal. A40-month-old female did not produce a litter in Royal ChitwanNational Park (RCNP) (McDougal 1977). Similarly, two 48-month-old Amur tigers did not produce litters yet the averageage at which females started to reproduce for the first time was48 months (n =4; Kerley et al. 2003). In a semi-arid habitat ofPanna and the moist habitat region of Pench Tiger Reserve,India, females gave birth to their first litter, on average, at theage of 39.8 months (n =5; Chundawat et al. 2002) and

Eur J Wildl Res

31 months (n =1; Majumder et al. 2012), respectively. Theearliest record of a female with her first litter was at 33 months(n =1) in our study (Singh 2011) and is close to what wasobserved in Panna and Pench Tiger Reserve (Chundawatet al. 2002; Majumder et al. 2012).

The translocated female TF-01 in STR was firstphototrapped with cubs in August 2012 at 92 months old;similarly, TF-44 and TF-18 females were at least 67 and79 months old, respectively, although they did not produce alitter during the study. Thus, the age at parturition in STR isrelatively higher than the ages determined in any other studyin India. Data from zoos also indicate that tigers usually reachsexualmaturity or produce their first litter when 36–60monthsold (Sankhala 1967; Schaller 1967).

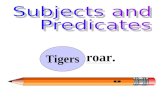

Published data on other large felids reported the mean age atwhich a female reproduces for the first time was 26–48 monthsfor the African lion (Panthera leo; Schaller 1972), leopards (P.

pardus ; Balme et al. 2012), mountain lions (Puma concolor;Logan and Sweanor 2001),cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus; Kellyet al. 1998), and jaguar (Panthera onca; Desbiez et al. 2012).There is a moderately correlation between (R2=0.3; Fig. 1) ageat first reproduction of females with body mass (i.e., tiger,leopard, African lion, cheetah, jaguar, and puma); however, bodymass is positively correlated with mean litter size (Singh et al.2013a). The RTR holds a high density of wild prey biomass(6,429.8 kg/km2) (Bagchi et al. 2003), and the principal preydensities across different tiger reserves in India did not influencereproductive parameters (Singh et al. 2013a). The higher age atfirst parturition of female tiger in semi-arid habitat region (RTRand STR) might be due to the influence of harsh climaticconditions during summer and the low annual precipitation(<800 mm) compared to other reserves (Singh et al. 2013a).

Considering the gestation period of 108 days, it is assumedthat females come into estruses at about 36 months, although

Table 1 Age at first reproduction of female tigers in Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, India during 2005–2013

FemaleID

Approximatedate of birth

Approximate age firsttime sighted (months)

Approximate age at firstbreeding (±2 months)

First time sightedwith cubs

Source; first timesighted with cubs

Approximate age of females atfirst their parturition (months)

TF-08 October 2006 6 February, 2011 April, 2011 Tourist guide 52

TF-11 February 2006 6 November, 2008 February, 2009 Camera trap 33

TF-13 October 2004 6 October, 2008 December, 2008 Camera trap 48

TF-17 October 2006 2 April, 2012 June, 2012 Tourist guide 66

TF-19 October 2006 2 March, 2011 May, 2011 Tourist guide 53

TF-39 September 2008 2 March, 2012 April, 2012 Tourist guide 42

TF-41 October 2007 2 March, 2013 May, 2013 Tourist guide 65

TF-37 December 2007 2 Died in March, 2013

Mean age of first reproduction 51.3±4.5 months

TF-01a October 2004 6

TF-18a October 2006 2

TF-44a October 2007 2

a Translocated in Sariska Tiger Reserve between July 2008 and July 2010

y = 0.099x + 28.88 R² = 0.3

0

10

20

30

40

50

0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200

Age

in m

onth

s

Body weight of large felids (kg)

Age at first reproduction (months)

Linear (Age at first reproduction (months))

Tiger

Lion

Jaguar

Leopard

Cheetah

Puma

Fig. 1 Mass (in kilogram) in relation to the age at first reproduction ofdifferent large felids. (source data: body mass (Carbone and Gittleman2002), age of first parturition and lion (Schaller 1972), cheetah (Kelly

et al. 1998), puma (Logan and Sweanor 2001), jaguar (Desbiez et al.2012), and tiger (Smith and MacDougal 1991 and present study))

Eur J Wildl Res

Sunquist (1981) and Chundawat et al. (2002) observed thatfemales come into estruses at ∼29months. In RTR, one female(TF-18) came into heat (in February 2009) and started matingat 28 months, which is close to what earlier studies havereported. The information about conception rate is not availablefor wild tigers but data from zoos reveals that the conceptionrate of tigers is 29 % (Kleiman 1974).

The tiger population in RTR is an important source popu-lation in the western-most part of their range; therefore, toensure long-term conservation goals, we suggest continuousmonitoring of tiger populations to develop better understand-ing of reproductive biology.

Acknowledgments We thank the Director and Dean of the WildlifeInstitute of India for their support. We thank the Rajasthan ForestDepartment and the reserve officials and field staff at RTR for permis-sions and for facilitating this work. We especially thank nature guides ofRTR and our field assistants, M. S. Gurjar and S. Sharma, for providingsupport. The Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun provided financialsupport for this work.

References

Bagchi S, Goyal SP, Sankar K (2003) Prey abundance and prey selectionby tiger (Panthera tigris) in a semi arid, dry deciduous forest inwestern India. Journal of Zoology 260:285–290

Balme GA, Batchelor A, Britz NDEW, Seymour G, Grover M, Hes L,Macdonald DW, Hunter LTB (2012) Reproductive success of fe-male leopards Panthera pardus : the importance of top-down pro-cesses. Mammal Review 43:221–237

Berger J, Cunningham C (1995) Multiple bottlenecks, allopatric lineagesand bad lands bison Bos bison : consequences of lineages mixing.Biological Conservation 71:13–22

Carbone C, Gittleman JL (2002) A common rule for the scaling ofcarnivore density. Science 295:2273–2276

Carter J, Ackleh AS, Leonard BP, Wang H (1999) Giant panda(Ailuropoda melanoleuca) population dynamics and bamboo (sub-family Bambusoideae) life history: a structured population approachto examining carrying capacity when the prey are semel parous.Ecological Modelling 123:207–223

Champion HG, Seth SK (1968) A revised survey of forest types of India.Government of India, New Delhi

Chundawat RS, Gogate N,Malik PK (2002) Understanding tiger ecologyin the tropical dry deciduous forests of Panna Tiger Reserve. Finalreport, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun

Desbiez ALJ, Traylor-Holzer K, Lacy B, Beisiegel BM, Breitenmoser-Würsten C, Sana DA, Moraes EA Jr, Carvalho EAR Jr, Lima F,Boulhosa RLP, De Paula RC, Morato RG, Cavalcanti SMC, DeOliveira TG (2012) Population viability analysis of jaguar popula-tions in Brazil. Cat News 7:35–37

Dinerstein E, Loucks C, Wikramanayake E, Ginsberg J, Sanderson E(2007) The fate of wild tigers. BioScience 57:508–514

Gompper ME, Stacey PB, Berger J (1997) Conservation implications ofthe natural loss of lineages in wild mammals and birds.Conservation Biology 11:857–867

Jhala YV, Qureshi Q, Gopal R, Sinha PR (2011) Status of tigers, co-predators and prey in India. National Tiger Conservation Authority,Govt of India, New Delhi and Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun.TR 08/001, 151 p

Karanth KU (1995) Estimating tiger (Panthera tigris) populations fromcameras trap data using capture–recapture models. BiologicalConservation 71:333–338

Kerley LL, Goodrich JM, Miquelle DG, Smirnov NYE, Quigley HB,Hornocker MG (2003) Reproductive parameters of wild femaleAmur (Siberian) tigers (Panthera tigris altaica). Journal ofMammalogy 84:288–298

Kelly MJ (2001) Lineage loss in Serengeti cheetahs: consequences ofhigh reproductive variance and heritability of fitness on effectivepopulation size. Conservation Biology 15:137–147

Kelly MJ, Laurenson MK, FitzGibbon CD, Collins DA, Durant SM,Frame GW, Bertram BCR, Caro TM (1998) Demography of theSerengeti cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) population: The first 25 years.Journal of Zoology 244:473–488

Kleiman D (1974) The estrous cycle of the tiger (Panthera tigris). In:Eaton RL (ed). The world’s cats Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle,Washington, pp 60–75

Logan KA, Sweanor LL (2001) Desert puma: evolutionary ecology andconservation of an enduring carnivore. Island Press, Washington,D.C

Majumder A, Basu S, Sankar K, Qureshi Q, Jhala YV, Nigam P (2012)Home ranges of the radio-collared Bengal tigers (Panthera tigristigris L.) in Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, Central India.Wildlife Biology in Practices 8:36–49

Mcdougal C (1977) The face of the tiger. Rivington Books, London, UKSankhala K (1967) Breeding Behavior of the Tiger, Panthera tigris, in

Rajasthan. International Zoo Yearbook 7:133–147Schaller GB (1967) The deer and the tiger. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, 384 pSchaller GB (1972) The Serengeti lion. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, 504 pSeidensticker J, Christie S, Jackson P (1999) Preface. Riding the tiger:

tiger conservation in human dominated landscape. In: SeidenstickerJ, Christie S, Jackson P (eds) Preface. Riding the tiger: Tigerconservation in human dominated landscapes. CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, UK, pp xv–xix

Shaffer ML (1981) Minimum population sizes for species conservation.BioScience 31:131–134

Singh R (2011) Assessment of tiger population status and habitat suit-ability using non-invasive and geospatial tools at landscape level inRanthambhore National Park. Ph.D. Dissertation, Gurukula KangriVishvavidhyala, Haridwar, India

Singh R, Nigam P, Goyal SP, Joshi BD, Sharma S, Shekhawat RS (2011)Survival of dispersed orphaned tiger cubs (Panthera tigris tigris) infragmented habitat of Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve In India. IndianForester 137(10):1171–1176

Singh R,Mazumdar A, Sankar K, Qureshi Q, Goyal SP, Nigam P (2013a)Interbirth interval and litter size of free-ranging Bengal tiger(Panthera tigris tigris) in dry tropical deciduous forests of India.European Journal of Wildlife Research 59:629–636

Singh R, Qureshi Q, Sankar K, Krausman PR, Goyal SP (2013b)Use of camera traps to determine dispersal of tigers in a semi-arid landscape, western India. Journal of Arid Environments 98:105–108

Smith JLD, McDougal CW (1991) The contribution of variance inlifetime reproduction to effective population size in tigers.Conservation Biology 5:484–490

Smith JLD, Wemmer C, Mishra HR (1987) A tiger geographic informa-tion system: the first step in global conservation strategy. In: TilsonRL, Seal U (eds) Tigers of the world: biology, bio-politics, manage-ment and conservation of an endangered species. Noyes, Park Ride,pp 464–474

Sunquist ME (1981) Social organization of tigers (Panthera tigris) inChitwan National Park, Nepal. Smithsonian Contributory Zoology336:1–98

Eur J Wildl Res