Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun: a Therapeutic ... · Fighting Witchcraft before the...

Transcript of Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun: a Therapeutic ... · Fighting Witchcraft before the...

-

4X0

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun: a Therapeutic Ritual from Neo-Babylonian Sippar

Daniel S C H W E M E R

Ceremonial anti-witchcraft rituals usually include the presentation o f offerings and the recitation o f prayers to a deity (sometimes to a pair or small group of deities), the symbolic destruction of the witches who are represented by substitute figurines and the purification of the patient him-self by washing, putting on pristine clothes and other symbolic gestures. By contrast, instructions for the preparation of medications or apotropaic devices effective against witchcraft, such as potions, salves, phylacteries or necklaces, are mostly given as succinct prescriptions which detail the drugs to be used, briefly describe their processing (which may include the recita-tion of an incantation) and provide information on the application of the fi-nal product1.

There are, however, exceptions to this overall picture: a few of the in-structions for the preparation of anti-witchcraft salves or necklaces take the form of complex ceremonies during which the remedies are consecrated in the presence of the deities addressed in the ritual. Only two examples o f this type o f ceremonial anti-witchcraft ritual are known; both contain prayers addressed to Marduk and have been the object o f repeated study.

The ritual BMS 12+ II2 was used for preparing a necklace and two salves3 effective against witchcraft. The ritual included the usual offerings and a recitation of the prayer 'Marduk 5'; furthermore, a short incantation addressed to the personified anhullü-plant was spoken over the necklace (a linen thread on which beads and artificial leaves7 o f the anhullü-plant had been strung). The purpose clause at the beginning of the text shows clearly that the necklace and the salves were considered to have apotropaic and purifying power (line 1), a notion that finds further support in the de-

1 For a general overview of witchcraft therapies, see Schwemer 2007a: 194-246. 2 For an edition of the text, see Mayer 1993; for a discussion of the development of the text,

see Abusch 1987: 61-74. 'The preparation of a salve is described in lines 8-11; the preparation of a second salve

containing powder left over from the materials which were used to prepare the artificial leaves7 of the anhullü-p\an\s described in lines 14-15. This second salve is again referred to in lines 101-102, while lines 116-17 probably refer to the first salve.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 481

scription and Interpretation o f the salves and of the amulet necklace given in the text of the prayer which, in contrast to the purpose clause, describes the patient as already having been afflicted by witchcraft (lines 67-78). Marduk's role is to lend divine approval to the proceedings and to activate the power of the apotropaic substances.

Another ritual against witchcraft and various other evils, KAR 26 / / 4 , was performed before Marduk and his consort ZarpanTtu. It included, like BMS 12+//, the usual offerings and a recitation of a prayer addressed to Marduk ('Marduk 24'), but the main purpose of the ritual was the ceremo-nial preparation of a necklace with a pendant in the shape of an urdimmu ( 'Wi ld Dog' ) 5 . The short recitation addressed to the urdimmu indicates that the function of the necklace was both therapeutic and apotropaic: mimma lemna ... ina zumrTya ukkis lä tusathä lä tusasnaqa "expel all evil ... from my body, do not let it come near me, do not let it approach me" (rev. 31-33). This chimes well with the beginning o f the text whose symptom de-scription suggests a therapeutic intention of the ritual (obv. 1-10), while its purpose clause seems to indicate an apotropaic objective (obv. 10). A t the end of the ritual, a we/w-pouch and, apparently, a salve are used, but their contents and purpose are not specified6.

An anti-witchcraft ritual of a similar type can now be reconstructed based on unpublished fragments from Neo-Babylonian Sippar housed in the Istanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri, Istanbul7. The five fragments numbered as Si 34, 722, 725, 745 and 818 belong to the group of tablets that was exca-vated in 1894 at ancient Sippar (modern Abu Habba) by Vincent Scheil and subsequently brought to what was then the imparatorluk Müzesi at Is-tanbul. The fragments remained unpublished, but were identified by Scheil as "Fragment de siptu avec hymne" (Si 34), "Fragments de textes reli-gieux" (Si 722 and others), "Fragment de siptu" (Si 725) and "Fragment de siptu, insignifiant" (Si 745) in the catalogue of texts that was published in Scheil's report on his work at Sippar8. Fritz Rudolf Kraus, during his

4 For an edition of the text, see Mayer 1999 with previous literature; for a new copy of KAR 26, see Schwemer 2007b, no. 21.

5 On the urdimmu and its identification, see Ellis 2006 with previous literature. 6 Unexpectedly, the instruction to put on the necklace refers to the neck of the exorcist (the

second-person referent in this like in many other rituals): ina seri gassa ramänka tullal annä ana (var.: ina) kisädika tasakkan "in the morning you purify yourself with gypsum, you put this (necklace) around your neck" (rev. 36-37). Perhaps kisädika may be regarded as a mistake for ki-sädisu; but since both extant manuscripts have kisädi{Gv)-ka (KAR 26 rev. 36 / / C T N 4, 180 obv. 1 17') one would have to assume that this mistake had become part of the transmitted text.

71 would like to thank the Turkish authorities for the permission to work in the collec-tions of the Istanbul Museum. I owe a Special debt of gratitude to Director Zeynep Kiziltan and to Ms Asuman Dönmez, the curator of the collection of cuneiform tablets.

"See Scheil 1902: 104, 138-39.

-

482 Daniel Schwemer

stay at Istanbul (1937-49), joined Si 722 and Si 725; it is unknown wheth-er the jo in of Si 745 and Si 818 is also owed to him 9 . The fragments were then copied by Frederick W. Geers, but these drawings, like all of Geers' copies, remained unpublished. In 1969 and 1973, within the framework of his work on Babylonian anti-witchcraft rituals, Tzvi Abusch examined the Geers collection at the Oriental Institute, Chicago, and was able to add, among many others, the above-mentioned fragments to his list o f tablets relevant to his project. Shortly afterwards, Veysel Donbaz, then curator of the cuneiform tablet collections at Istanbul, graciously made available to him photographs of these and other Si-collection tablets of interest to him. Abusch put these photos at my disposal for our Joint work on the Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals, and in 2010 I had the opportunity to study and copy the fragments during a stay at the Istanbul museum. It then became clear that not only, as had always been recognised, Si 34 and Si 722 + 725 are duplicates, but also that Si 745 + 818 preserves the be-ginning of the same text which can now be almost completely reconstruct-ed. Despite their rather different appearance and, apparently, slightly dif-ferent length of lines, it seems possible that Si 34 and Si 745+ belonged to the same tablet (though a 'direct j o in ' is excluded). A l l fragments, whether originally two or three tablets, are inscribed in first-millennium Babylonian script, and, given that they were probably found in the same context as Si 1, a tablet inscribed with an anti-witchcraft ritual for Samas-sumu-ukTn, king of Babylon, they very likely date to the early mid-seventh C e n t u r y 1 0 .

The ritual text itself begins with a brief symptom description: a pa-tient is suffering from a series of various illnesses, and his 'way', i.e., his condition and its appropriate diagnosis, cannot be determined by means o f divination (line 1)"; in the broken part of this line, there is enough space for the restoration of a purpose clause or a short witchcraft diagnosis.

The ritual instructions begin with an indication of when and where the ceremony should be performed: before the moon-god Sin and the sun-god Samas at a time when both the (füll) moon and the sun are visible at the same time on the western and eastern horizons (line 2) 1 2 . It is hoped

' The museum number "Si 745 + 818" is written on only one of the two fragments; perhaps the join was already made when the fragments were registered.

1 0 An edition of Si 1 (with its duplicate Si 738) is in preparation for the Corpus of Mesopota-mian Anti-witchcraft Rituals (see Abusch-Schwemer 2011). Note that Si 1, like PBS 1/2, 120, another anti-witchcraft ritual written for Samas-sumu-ukTn, is dated to the 24* of Tebetu. It is rather intriguing that there is a fragmentarily preserved collection of usburruda rituals written in Neo-Assyrian script among the tablets excavated by Scheil at Sippar (Si 96). For the group of ri-tual texts that can be assigned to Samas-sumu-ukTn, see Parpola 1983: 164.

" For this Interpretation of the symptom description, see infra, note on line 1. 1 2 For this Special constellation and its Interpretation in ritual lore and divination, see infra,

notes on lines 2 and 3.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 48^

that at this time, when Sin and Samas decide the fate of the people of the land, they w i l l also render a favourable verdict for the patient. After a comparatively frugal offering arrangement has been set up (lines 3-6), the exorcist prepares a linen bündle filled with various types of 'wood' and mixes a potion by stirring several drugs into beer; both medications are then placed at the side of the ritual arrangement.

The following section is a straightforward anti-witchcraft ritual: clay figurines representing warlock and witch are made, inscribed with their names and presented before Sin and Samas. Then the patient steps upon the figurines and recites three times a prayer addressed to the two gods (lines 12-14). The prayer, whose text is given in füll, asks for a favourable decision of the patient's fate and for the destruetion of the evildoers by means of their own witchcraft that is to be returned to them (lines 15-30). After the recitation of the prayer the patient squashes the figurines with his foot and washes himself over the squashed figurines, thereby enacting the return of the witchcraft to its originators requested in the prayer (lines 31-32). Then he strews a flour made of kasü-spice on the figurines, a gesture that is not attested in other anti-witchcraft rituals. Maybe the kasü-f\om should symbolically bind warlock and witch 1 3 ; alternatively, one could ar-gue that the layer of pungent-smelling flour served as an apotropaic sealing that isolated the figurines from the patient1 4.

After the destruetion of warlock and witch has thus been aecom-plished, the patient purifies himself wi th water, smoke and fire ("holy wa-ter vessel, censer and torch") and is then led by the exorcist to the offering arrangement; apparently, the destruetive rites are performed at a distance from the offering arrangement15 (lines 31-34). Now the exorcist has the pa-tient speak a second prayer to Sin and Samas in which the patient asks again for a favourable verdict and the removal o f the evil that has befallen him (the füll text o f the prayer is given in lines 35-42). Finally, the linen pouch and the potion that had been prepared at the beginning of the pro-ceedings are put to use: the exorcist places the linen pouch filled with var-ious kinds of 'wood' on the patient's neck (probably he actually hangs it around the patient's neck by means of a cord), and the patient drinks the potion containing the anti-witchcraft drugs (lines 43-44).

1 3 Cf. the connection made between the kasü-phnt and kasü "to bind" in Maqlü V 34 (see Schwemer 2007a: 198).

1 4 Cf. the use of gypsum in a similar context in Farber 1977: 231, line 48' (see Schwemer 2007a: 217).

" Cf. STT 256 rev. 34, where the exorcist is advised to withdraw from the offering arrange-ment before making figurines of warlock and witch.

-

484 Daniel Schwemer

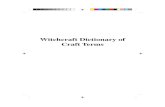

Fig. 1: Si 34 (ms. a,)

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 485

Fig. 2: Si 745 + 818 (ms. a 2)

The last few lines, which are only fragmentarily preserved, give a positive prognosis: the patient w i l l be well for the rest o f his life; he w i l l be treated with favour by fellow-humans and obtain propitious omens from the diviners (line 43-45a). This last part of the prognosis corresponds with the Statement o f the symptom description that the patient's condition can-not be determined by means of divination. It also ties in well with the em-phasis that is placed throughout the whole ritual on obtaining a favourable verdict for the patient. The introductory phrase o f the prognosis, adi üm baltu "as long as he lives", indicates that the ritual had not only a ther-apeutic, but also an apotropaic function.

In contrast to the two Marduk-rituals BMS 12+ / / and KAR 26 / / , the Sippar-text includes a symbolic destruetion of the witches. But like the

-

486 Daniel Schwemer

Marduk-rituals it embeds the preparation of medications and apotropaic de-vices into a complex ceremony; it also shares the combination of ther-apeutic and apotropaic objectives that is characteristic of the two Marduk-rituals.

Transliteration

The line division of the transliteration follows Si 34 (ms. a„ flg. 1) (+) ? Si 745 + 818 (ms. a2, flg. 2); several lines can be restored with the help of Si 722 + 725 (ms. b, figs. 3-4). There are remarkably few variants between the two (or three) sources, which mostly agree even in their divi-sion of the lines (cf. the notes on lines 27-28, 35-36 and 40-41). It seems likely that the present manuscripts were copied from the same original, quite possibly by young scribes as part of their training.

1 a2b summa(ois) amelu(~NA) mwrsä«F ' (GiG) m e ä marus{G\G)-ma alakta (A.RA)-SÜ / ä ( N u ) pär-sat [x x x x]

2 a2b e-nu-ma dsin(30) u dsamas{uT\j) it-ti a-h[a-mis innammarü-ma] 3 a2b purusse(BS.BAR) mäti(KVR) da-num u d e / / / / (BAD) iparrasüivjj^"

ina x x x [x x x] 4 a2b [qaqq]ara([K]i) tasabbit(sAR) me(A) ellüti(Kv) tasallah(sv) sina(2)

patiri{G\.D\i%) tukän(GTN)a" sina{2) g i ä [x (x) tasakkan(GAR)a"C?)] 5 a2b [ a f t a / w ( N i N D A ) e]l-lu tarakkas(KEs)-su-nu-ti sikaru (restü)

( K A S . S A G ) el-lu tu-n[aq-qa(-sü-nu-ti)] 6 a2b [tu]sken([K.]i.zA.zA)-ma kam taqabbi(pvsn.GA)-sü-nu-ti i-lut-ku-

nu rabite{GA\)" llud^-luP] a2b • —

7 a2b ^ W S W ^ E S I 1 ) /Ä(GIS) / ? / M ( B Ü R ) sinni{zv) piri(AM.s\) zistaskarinnu(rTASKARm~l) gismesu(MEs) giimusukkannu(MES.RMÄ1. K A N . [ N A ] )

8 a2b [x x] x es-mä-ru-ü ^kur-ka-nam simkikkiränu(sE.Li) 9 a2b [an7-hu]l!-lu4-u issT(Gis)mc's an-nu-ti ina rtg^Ye(GADA) tarakkas

( K E S ) ina let(TE) riksi(KEs) tasakkanP"GAR1)'""' a2b • —

10 a2b ["xj-x " a t ö ' w « ( K U R . K U R ) Har-mus5 Hmhur{\G\)-lim Hmhur(\G\)-es-ra(20)

11 a2b [ l , x-x] -x welO-kul-la istenis(Y)"'s ina sikari{KAs) tamahhas(siG)a* ina let(TE) riksi(KEs) tasakkan{GAR)°"

a2b — — 12 a2b [sina(2) salmT{n\j) ]ikassäpi(vsn.zu) m u n u s A:a i ] iäp /z ' (u ] s l l . zu) sä

tidi(\M) teppus(DÜ)UI sumsunu(MV.NE.NE)

Kighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 487

13 a :b [ina naglab(MAS.s\L) sumeli(\5Q)-sü-nu] ta[sattar](s[AR]y"r-ma^ ana mahar(\G\) dsin($0) u dsamas(uT\j) tuszäs(GUB)-su-nu-ti

14 a,b [ina muhhi(vGu) salmT(Nu)mei sü-nu-ti(?) iz]zäz(G\j]B)--ma kiarn (URJ.GIM) iqabbi(ouu.GA)

a2b 15 a2b [dsi]n(3]0) «^(""ZÄLAG" 1 ) same(TA^R)V hO erseti(rKp)['im m]u-nam~

mir uk-lu 16 a,b [dsamas(vru) s a ] r ( L U G ] A L ) same(A^y u erseti(Ki)'m d e / / [ z / ( E N . L [ i L )

j ' ] / i ( D i ] N G i R ) m 4 ä mu-sim srmäti(NAM)MTI 17 a,b [ ;7ö (DiNGiR) m e ä g]as-ru-tü sä ina qe-reb same(AN)V ellüti

(rKÜi)mpä]?-r„mi rz-z?_z/T?_[z]M?

18 a,b [ina] as-ru sip-TtP iparrasü(YJj5)su [purussä(ES.BAR)] 19 AjB [ina ümi(u4)mi] an-ni-i ana ni-is qätiya(su']:-MU) i-ziz-[za-nim-

ma] 20 a^ [si-ma]-a tes-li-tum kas~sä-pi u kas-sap-[t]i 21 a,b [sä kis]pi(v]sn) ruhe(usu) ruse(vsn) up-sä-se-e lemnüti(mjE)mil sä

amelüti(w)mti Tpusü(E>\jyi-nin-ni 22 a,b salmr(Nü)[mef-sü-nu epus(E>\j)m~ ina mahrl{\G\)-ku-nu e-li-sü-nu

az-ziz 23 a,b di-[n]i di-na purussä(ES.BAR)-a-a pursä(KV5)s["] 24 a,b ina qibrti(nvU.GA)-ku-nu sir-tü Sä /Ö(NU) uttakkaru(KVR)[ri] 25 a,b ii an-ni-ku-nu ki-nim sä /Ö(NU) innennü(BAE)[U] 26 a,b kis-pi-sü-nu xru}-he-e-sü-nu ru-su-Hü-niP 27 a,b /Ö(NU) täbüti(r>um)mei sü-nu ana lmulp-hi-sit-[n)u Ui-tu-ru-ma? 28 a,b su-nu-ti li-is-[ba-i\u-sü-nu-ti 29 a,b / /M (DINGIR) sarru(20) kabtu(iviM) u A-M/>M(NUN) li-is-^bu-su1

eli([u]Gu)-sü-nu 30 a,b [ana]-ku arad(\R)-ku-nu lu-ub-lut lu-us-Him-ma dä-lP-[li-k]u-

xnu lud-luP a,b — — _

31 a,b saläsi(3)-sü imannü(*s\T^)nY\-ma salam(N\j) likassäpi(vsnJzu]) '^""^kassäpti^vs^.[z]u) ina sepi(TGlR1)-rsü P-[ser]

32 a,b /we ( R A 1 ) [ M ] E Ä ina muhhi(vGv)-sii-nu i~ra-muk ^ » / ' ( K U ) kasi ( G A z [ i ] ) [ s a ] r i-sa-raq-su-n[u-ti]

33 a,b egubbä{fA.GÜB1.BA) nignakka(mG.NA) g / z i 7 / d ( G i . i z i . r L Ä 1 ) ü-tal-la[l]

34 a,b [ana A-]/fe/([K]E§) tu~qar-rab-sü-ma ki-a-a[m] tu-sad-bab-sü a,b — . .

35 a,b [ / / ] w ( [ D i N G i R ] ) [ m ] e ä rabütu(GAE)m^ i-lit-ti da-nim sä nap-har same(AN) u erseti{Ki)

36 a,b [a]t-tu-nu as-hur-ku-nu-si e-se-e'-ku-nu-si

-

488 Daniel Schwemer

Fig. 3: Si 722 + 725 obverse (ms. b)

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 489

Fig. 4: Si 722 + 725 reverse (ms. b)

Oiienlalia - 32

-

490 Daniel Schwemer

37 a,b [sä- l]a- dumqa(sic5) Tpusa(Düyä ti-da-a {sä)7 kispT(vsn) ruhe(vsn) ruse(usn) up-sä-se-e lemnüti{wv)mki ipusa(n\j)'™"

38 a,b [amä]^([iNi]M) lemutti(mjL.)'< is-hu-ra i-se-a-a 39 a,b [ / /Q(DINGIR)] R « 1 Hs%-tär ü-za-an-^niP-u it-ti-ia 40 a[b [ma-ha]r-ku-nu az-ziz arki(EGiR)-ku-nu al-lak

a,b 41 a,b [x x] m c ä - /o/-«w saknü(GAR)nu lum-ni-iä Hip-siß-su ek-le-ti-ias li-

nam-mi-ru 42 a,b [e-sä-t]i-ia5 li-za-ku-ma dä-li-li-ku-nu lud-lul

a,b 43 a tb [issT(Gis)mis(!) rik]si(K]Es) ina kisädi(GÜ)-sü tasakkan(GAR)an sam-

m f ( r u l ) [ m e ] ä ina sikari(KAs) isattT(NAG)-ma Ö J / ( E N ) üm(v4)um baltu(Ti)

44 a,b [ki-ma] '^samasiviv) namir(zÄEAG)ir d[a-bi-ib] ittiO~Ki])-rsu1 kit-tu i-da-bu-ub

45 a (b r j7wra5Sw(ES .BAR)(? ) ] - r 5w' u71 dinP~T>i[1)-sü x [x x x (x) / / ( D I N G I R ) -sü] '

-

492 Daniel Schwemer

36 I have turned to you, I have sought you out! 37 [The one who] has acted malevolently against me, you know (him) -

(the one who) has performed witchcraft, magic, sorcery (and) evil machinations against me,

38 (who) has turned to (and) sought evil [wor]d(s) against me, 39 (who) has caused (my) [god] and goddess to be angry with me. 40 I have come [be]fore you, I w i l l follow you (devoutly)!"

41 "Your [...]s are put in place. May they cancel my evils, may they i l -luminate my darkness,

42 may they clear up my [conjfusion, so that I may sing your praise!"

43 You place [the (various kinds of) wood in the bun]dle on (or: around) his neck, he drinks the plants in beer; then, as long as he lives,

44 he w i l l be as bright(ly happy) as Samas; whoever [talks] to him w i l l speak sincerely;

45 his [decision] and his verdict... [...; his god] and his goddess w i l l be friendlily inclined to him, he [wi l l be in good] repute;

45a [his (oracular) decision] obtained from diviner and see[r w i l l turn out well].

Notes

1: Pluralized Gio m e ä can stand for simmü "wounds" or mursänü "illnesses". In a few passages simmu clearly is used as a more general term for "illness" 1 6, so that a translation "is suffering from illnesses" would not be excluded even i f a reading simmi (rather than mursäni) could be ascer-tained beyond doubt. The plural of mursu is mostly used with regard to many individual cases of an illness, but the present text with its reference to a number of different illnesses suffered by one individual is not unique; cf. Surpu I V 82-83: mämätüsu liptassirä bu(llutu sullumu Marduk ittTkäma), mursänü(GiG)m,:i-sü littakkisü bu(llutu sullumu Marduk ittikäma) "May his curses be undone — re(viving and healing rest with you, Marduk), may his illnesses be driven away — re(viving and healing rest with you, Marduk)" (Reiner 1958: 28; cf. Reiner 1956: 136, lines 78-79).

The phrase alaktasu lä parsat has a number of parallels in Babylonian literary and medical texts. In all of these passages, the literal meaning of alakta paräsu "to cut off the course", "to block the way", "to stop the ad-

See CAD S 277b-78a, though not all passages cited there represent this usage.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 493

vance", which is well attested in a variety of texts, does not produce a sat-isfactory sense:

usabri barä terti d[alhat] us'al sa'ila alakti ul [parsat]

I consulted a diviner, my omen [was] ob[scure], I asked a seer, my ... [was] not [. . .] .

K 2765 obv. 8-9 (ed. Lambert 1960: 288)

dalha teretu'a nuppuhu uddakam

The organs inspected for my extispicies are obscure, they are ambiguous every day17,

itti bäri u sä'ili alakti ul parsat with the diviner and the seer my ... is not ... . Ludlul bei nemeqi I 51-52 (ed. Lambert 1960: 32-33)18.

Building upon W. G. Lambert's discussion of these passages (1960: 284), T. Abusch argued in an article published in 1987 that alaktu ul par-sat s h o u l d be unders tood as a Spec ia l idiom meaning "an o r a c u l a r d e c i s i o n is not made"1 9. In Support o f his argument he pointed to the lexical equa-tion o f alaktu ("way", "course", then also "course of action", "way for-ward") with temu "planning", "decision", "instruetion" and the use of alaktu in this sense with regard to the (usually unfathomable) 'ways' of the gods. He also drew attention to the fact that alakti limad "learn of my alaktu" and alakti dummiq "improve my alaktu", both stock phrases o f Ba-bylonian prayer language, regularly co-occur with pleas for a favourable divine judgement 2 0. Moreover, he interpreted the phrase alaktasu ana lamä-di in the purpose clause of therapeutic texts as "that an oracle be manifest for h im" 2 1 .

Abusch's argument that the idiom alakti ul parsat, as used in Ludlul I 52 and related passages, must refer in one way or another to the un-successful consultation of divination experts and cannot, in these contexts, have its usual meaning "my way is not blocked" is certainly persuasive22

1 7 The interpretation of nuppuhü follows CAD T 365b-66a. 1 8 Line 52 is quoted in an inscription of Nabonidus; see Schaudig 2001: 493, 498, III 1. " See Abusch 1987 passim; for his discussion of the passages quoted above, see pp. 29-30. 2 0 See Abusch 1987: 18-27; for a collection of the relevant attestations in prayers, see Mayer

1976: 218, 285. 2 1 See Abusch 1987: 27-28; for a discussion of these passages, see the following. 2 2 For a critical review of the translation proposals predating Abusch 1987, see there p. 29

Ins. 46 and 49. Lambert favoured a translation "the omen of the diviner and the dream priest does not explain my condition", but, as rightly pointed out by Abusch, the comparable phrases in therapeutic texts with their logographic spelling of itti(Ki) rule out an interpretation of it-ti as "omen", "sign" (ittu). The translation "I cannot stop going to the diviner and the dream Inter-preter" (e.g., CAD A I 299a) is rather bland and difficult to reconcile with the normal use of itti "with". Schaudig 2001: 498, without further discussion, translates "with diviner and dream Inter-preter my severe condition was not brought to an end" ("mit Opferschauer und Traumdeuter wurde mein schlimmer Zustand nicht beendet"). But this interpretation, which takes its starting point from the literal translation "my course was not stopped", is hard to Square with the phrase ////' bäri u sä'ili alaktasu ana lamädi in BAM 446 obv. 8-9 (see infra). It also does not agree well with the expected diagnostic (rather than therapeutic) role of the divination experts.

-

494 Daniel Schwemer

and was later taken up by B. Böck. Reviewing the evidence recently pre-sented in PSD A I 148-51, Böck argues that Sumerian a - r ä too in some passages should be translated as "oracular decision", "omen". In support of her argument she refers to the lexical equation of a - r ä with Akkadian temu "planning", milku "counsel", sibqu "plan" and tasimtu "discernment"; the correspondence l ü - a - r a - m e - e n : sa te-er-ti-i[m ... ] in an unpub-lished OB bilingual quoted by PSD is regarded by her as unambiguous proof for a - r ä meaning "omen", though she does not provide any con-textual evidence supporting her translation of the phrase as "the one in charge o f extispicy" (rather than, e.g., "officeholder"; cf. bei terti)n. The overall contextual evidence for a - r ä in the meaning "omen" is not com-pelling, and Böck fails, in my view, to disprove convincingly the trans-lations offered by PSD for the relevant passages24.

I would still maintain that an interpretation that stays closer to the ba-sic meaning of alaktu is more appropriate for the phrase alaktu ul parsat and translate "my condition cannot/could not be determined (by means of divination)" 2 5 . The meaning "condition", which is well attested for Sumer-ian a - r ä and, within Akkadian, easily derived from the basic meaning of alaktu "passage", "way(s)", fits all contexts discussed by Abusch, in-cluding those where alaktu is used with lamädu or dummuqu. It then be-comes unnecessary to posit with Abusch a meaning "to reveal", "to make known" for the G-stem of lamädu "to learn" in the translation of the phrase alakti limad in prayer language (alakti limad "become aware of my condition", not: "reveal my oracular decision") 2 6.

2 3 Böck 1995 passim. For her discussion of l ü - a - r a - m e - e n : sa te-er-ti-i[m ... ], see p. 156; the phrase, attested in Ni 2765 col. I 5 (non vidi), remained untranslated in PSD A I 150-51.

2 4 For Inannaka to Nintinugga line 13, see now also Römer 2003: 244, 248 who translates ü - u g - a - u g - a a l - g e n - n a - g u 1 0 a - r ä - b i n u - z u as "kenne ich, wenn ich unter 'Ach' (und) 'Weh' einhergehe, deren (= der Krankheit) Verlauf nicht" (following PSD A I 150); different Black et al. 1998-2006, no. 3.3.10, who translate " I do not yet know the divine oracle concerning my being in agonies". Note that ePSD (http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/, Version last updated 26 June 2006) lists "omen" as one of the meanings of a - r ä (without comment or relevant attestations).

2 5 Lambert 1960: 284 considered a similar translation: "My 'way' has not been determined with (= by? or, at the place of?) He remarked that this interpretation would give "satis-factory sense", but rejected it because he found it difficult to accept that alakta paräsu should have two idiomatic usages with a "totally different sense". Later, W. von Soden gave preference to this interpretation in his translation of Ludlul: "bei Opferschauer und Traumdeuter blieb mein Weg ungeklärt" (von Soden 1990: 117).

2" See Abusch 1987: 24-25. In support of his argument he cites K 128 rev. 22-24 (prayer of the diviner to Ninurta). I disagree with his interpretation of these lines; following Mayer 2005 (cf. also Annus 2002: 207-208), I would translate: "the (extispicy) judgement (di-i-nu) was im-pcnetrable and difficult to comprehend (a-na la-ma-da äs-tü), determining the matter (pa-ra-

-

496 Daniel Schwemer

11 MMH(SU.SI) damiqti(siG5)""' arki(EGm)-sü t[a-ra-si] 12 libbi(SA) / / / (DINGIR) ze-ni-i s w / / w m / ( s i L i M ) ™ ki-sir libbi(sÄ) / / / T D I N G I R ) -

[sü patäri(pu%)rl] (instructions for drugs to be worn around the neck follow)

B M 64174 obv. 9 - lo.e. 12 (ed. Geller 1988: 21-22, Abusch 1999: 118-19)

A very similar symptom description and purpose clause, preserved in BAM 446 obv. 1-9, confirms that the concern for the patient's condition re-sulted from the fact that attempts at clarifying the patient's Situation by means of divination had failed. In this passage, the term alaktu "con-dition" is not only used in the symptom description (alaktasu marsat, line 1), but also taken up in the purpose clause where it is associated with C o n -sulting divination experts (itti bäri u sä'ili alaktasu ana lamädi, lines 8-9):

1 [summa(Dis) amelu{NA) balit(i\)-ma a-lak]-ta-su marsat(GiG)a' ka x 3 1 [x x x x x x]

2 [iz-zi-ir-ti] pi(KA) «wf(uN) m e 5 ma-a'-da-t[i* x x x x x x] 3 [ M j p i ä i J e ^ N i G . A K j / A 1 ) bel(EN) amätT(imM)-sü ana / ä ( N u ) kasädi

(SÄ.SÄ)-SW ubän(su.s\) dam[iqti(si[G5*)'im arkisu ana taräsi] 4 [libbi(sk) / / / (DINGIR) z]e-ni-i ana sul-lu-mi ki-sir lib-bi / / / ( D I N G I R ) -

[sü ana patäri] 5 [amät(TNiMy le]mutti(H]uL)'"" ana mahar(iGi) ameli(NA) lä(Nu) paräki

( G I B ) 5 M « ä r z ( M Ä s . G E 6 ) M " damqäti(siG5)mei ana su-[ub-se-e(?)] 6 [//Ö(DINGIR) i a r ] r a ( L U G ] A L * ) kabta(iDiM) rubä(~NVN], text: L Ü ) ana

su-tam-gu-ri-sü12 da-bi-ib itti(Ki)-sü kit-tü ana d[a-ba-bi] 7 *hu-ucT- lib-bi ana ra-se-e dsed(AEAE>) dumqi(sics) dlamassi(EkMA)

dumqi(siG5) itti(YA)-sü ana ara/ /[w/c/](D[u.DU* 1 ])

8 / / ( D I N G I R ) — u distar(l5)-sü ina qaqqadT(sAG.Du)-sü ana izuzzi (GUB) Z I / / / / ( K I ) l ü / 3än (HAL) u i ä [ ' / / / ] ( E [ N S i ] )

9 alakta^A^.RAj-sü ana lamädi(rsj)dm di-in-sü purussä(ES.BAK)(-sü) rana* sur*~*-[se-e]

[ I f a man has recovered (or: is in good health?), but] his (future) [con]dition (determined by divination) is troublesome, [the curse of] the mouth of the many people [ . . . ] , so that [the machination]s of his adversary not reach him, [so that he be] in go[od] repute, so that (his) angry [god] be reconciled, so that (the god's) anger [be re-

-" Note that this sign does not look like U [N ; the second vertical is clearly not broken. Read pcrhaps ii'//fa?u(KA. rfi' 1 .[GAL) ...] "slan[der ...]"?

" Cf. fragmentary BAM3\6 rev. V 17: [... / / ^ ( D I N G I R ) ] sarra(20) kabta(iD\M) [u raöä(NUN)] ana su-iam-gu-ri (see Abusch 1985. 99).

" Borger 2003: 252 no. 15 does not include lamädu among the Akkadian readings of logo-graphic zu. But in light of the phonetic complement here and in BAM 316 obv. 1115' there can be no doubt that, as assumed by Abusch 1987 and 1999, lamädi rather than ede is intended.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 497

moved], so that evil [talk] not obstruct (that) man, so that favourable dreams [be there (for him)], so that [god, kin]g, nobleman (and) magnate be in agreement with him, so that whoever talks to him [speak] sincerely, so that he acquire happiness, so that a good sedu-spirit (and) a good lamassu-spirit [always] accompany him, so that his god and his goddess stand by him, so that his condition be ascer-tained by Consulting the diviner and the se[er], so that he ob[tain] his verdict (and) decision.

BAM 446 obv. 1-9 (collated)

That a diviner would be consulted to determine the course of an illness also transpires from Ludlul I I 110-11: ul usäpi äsipu sikin mursTya u adanna silVtiya bärü ul iddin "the exorcist has not diagnosed the nature of my illness, nor has the diviner established the term of my disease" (Lambert 1960: 44).

To conclude: The passages quoted suggest that alaktu "course", "ad-vance", "way" could be used with a meaning "condition" ( < course, de-velopment o f a person's Situation). Gods could be asked to become aware of or to improve a person's condition (alakta lamädu, alakta dummuqu). A person's condition could be investigated by Consulting divination experts (alakta lamädu); it could be found to be troublesome (alaktu marsat), even i f Symptoms of illness could not yet be observed. Finally, the consultation of divination experts in such matters could fail to produce a satisfactory and favourable result (alaktu ul parsat). That the unsuccessful consultation of the divination experts in such a Situation was regarded as a typical S y m p -tom of people who had been bewitched by their adversaries is confirmed by the following symptom description: summa(uis) amelu(NA) bel(EN) le-mutti(HUE)'m irsi(TUK)s> ... Z / / / (KI) lübäri(HAE) u 1 Ü£Ö'Z7/(ENSI) din(E>\)-sü u purussä(ES.BAK)-sü la sur-si " I f a man has acquired an adversary, ... (and) he cannot obtain a verdict and a decision for himself by Consulting the diviner and the seer"34.

The phrase alaktasu lä parsat in the symptom description of the pre-sent text should be understood in the light of these passages: the patient is suffering from a number o f illnesses, and the nature of his condition, his future 'course' cannot be determined by means of a positive oracle that would assure the patient o f a soon end to his suffering. This interpretation flts well with the final prognosis at the end of the text that the patient w i l l

1 4 SpTU 2, 22 + 3, 85 obv. II 8, 15; I regard sur-si as a by-form or corrupted spelling of the slalive sursu (rasü S; perhaps this can be compared to the irregulär D-stem statives surri and kurri, for which see GAC § 105 1*); Mayer 2008: 105 understands the form as a representation

sursu. but also eonsiders an interpretation as a corruption of süsur (eseru S).

-

498 Daniel Schwemer

obtain a favourable oracular decision from diviner and seer (line 45a, par-tially restored).

At the end of the line, one could either restore a purpose clause (e.g., ana bullutisu " i n order to heal him") or a short witchcraft diagnosis (e.g., amelu sü kasip "that man is bewitched").

2: The phrase Sin u Samas itti ahämis innammarü is regularly used in astrological reports to refer to the simultaneous visibility of the sun and the moon. Reports on the observation of this phenomenon are restricted to days 13-16 of a given month, indicating that only the simultaneous visibil-ity o f the füll moon and the sun in (approximate) Opposition to each other was regarded as significant. Only a simultaneous visibility on the 14,h day was interpreted as a favourable omen 3 5, while the observation o f the same phenomenon on the 13*, 15th or 16th day indicated misfortune 3 6. Thus it seems likely that the present ritual was to be performed on days when the (almost) füll moon could be seen in the morning and evening on the hori-zon opposite to the sun. This assumption finds support in the fact that an anti-ghost ritual addressed to Sin and Samas had to be performed "on the 15th day, the day when Sin and Samas stand together": ina U 4 .15.KÄM Um (v4)"m dszrt(30) u Asamas(vTü) istenis(X)niS izzazzü(GUB)zu (KAR 184 = BAM 323 rev. 93 / / , ed. Scurlock 2006: 305-307, no. 91). There, the proceedings take place in the early morning, when the sun appears on the eastern hori-zon, while the füll moon can still be seen in the west (cf. rev. 96-97, 99). The present ritual does not specify the time of the day at which it is to be performed; perhaps one could carry it out either at sunrise or at sunset (cf. KAR 80 = KAL 2, 8 rev. 19 / / , ed. CMAwR I , 8.4: 62) 3 7 .

3: The text suggests that the simultaneous presence of the moon-god and the sun-god on the western and eastern horizons was considered to co-incide with the determining of the fate by Anu and Enli l , the traditional heads o f the Babylonian pantheon. Within the present context, however, Anu and Enlil are certainly to be understood as honorifics of Sin and Sa-mas themselves. The patient expects the moon-god and the sun-god to de-cide his own fate together with the fate of the population of the land as a whole. The association o f Sin with Anu and of Samas with Enlil is not

1 5 See SAA 8, 15 obv. 6-rev. 4 and passim in that volume; see also S A A 10, 116 obv. 5-9. 13"- day: SAA 8, 194 obv. 1-3, 266 obv. 1-3, 360 obv. 1-5; 15lh day: SAA 8, 23 obv. 1-4, 24

obv. 1-5 and often in that volume; 16* day: SAA 8, 25 obv. 6-rev. 3, 111 obv. 1-5, 168 obv. 1-5, 327 obv. 5-7. The chief exorcist Marduk-sakin-sumi mentions a namburbi ritual that could be per-formed to counter the evil portended by a simultaneous visibility of the moon and the sun on the 13* day (SAA 10, 238 rev. 13-19).

"CMAwR 1 = Abusch-Schwemer 2011.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 499

only found here: the moon-god is identified with the sky-god Anu in a b i -lingual su'ila-prayer ( IV R 2 9 obv. 3, ed. Sjöberg 1960: 166-79, cf. Borger 1971: 81-83), and Samas is called the Enlil o f the gods in the present text (line 16) and one other Samas prayer (ABRT 2, 18(+) r. col. 9 11, ed. CMAwR I , 7.8, 7.: 27', cf. also Tallqvist 1938: 26). The role of adminis-tcring justice and deciding the fate o f the people features prominently not only in the prayer to Sin and Samas that was recited within the present rit-ual (lines 15-30), but also in the two other surviving prayers addressed to the two gods: in KAR 184 = BAM 323 rev. 100 (ed. Scurlock 2006: 306) they are called pärisü(KV5)su purusse(ES.BAR) ana m'sf(uN)m e ä rapsäti ( D A G A L ) M E Ä "makers of the decision for the widespread people"; in PBS 1/2, 106 rev. 5-7 (ed. Ebeling 1949: 178-83) one reads: purusse(ES.BAR) same(AN)e u erseti(Ki)'im at-tu-nu-ma (taparrasä) ... ta-sim-tü mä-/ « / / ( K U R . K U R ) sin(30) u samas(20) at-tu-nu-ma ta-sim-ma " I t is you who make the decision for heaven and earth, it is you, Sin and Samas, who decree the destiny for the lands." The same moti f also occurs in the heme-rology KAR 178, albeit in fragmentary context (obv. I I I 4-5): d ! s/«(30) u dsamas(vrv) purussä(E$.BAR) i-par-ra-su (cf. also KAR 178 obv. I I I 30-31, 59-60 / / 176 rev. I I 2-3, 31).

At the end of the line a phrase like ina seri asar sepu parsat " i n the steppe, at a secluded place" is expected. While the second sign after ina could well be read asar(Ki), the first fragmentary sign (perhaps L U H or ü , certainly not E ) poses difficulties. A n emended reading ina ü(-ri) asar(Ki) s[epu(G[iR) parsat], [qaqq]ara([K]i) tasabbit(sAR) "on the roof, i n a se-cluded place, you sweep the ground" i s not entirely excluded, even though üra tasabbit "you sweep the r o o f and qaqqara tasabbit "you sweep the ground" usually exclude each other; cf. PBS 10/2, 18 rev. 29' (collated): lu ina üri(üR) lu ina sen'(EDiN) qaqqara(Ki) tasabbit(sAR) "either on the roof or in the steppe you sweep the ground".

4: Two portable reed altars (patiru) are set up before Sin and Samas (the expected phrase ana Sin u Samas i s omitted). One more item, appar-ently made o f wood, is arranged before each god ( g i ä [x (x) . . . ] ; o f course, /.s-[x (x). . . ] i s equally possible). It remains unclear which Utens i l should be restored in the break: gi'spassüri(BANSVR) "tables" would fit the available space and the preserved determinative, but it is unlikely that two types o f table, patiru and passüru, were used at the same time. Other implements which one would expect to be mentioned i n the present context (e .g., nig-nakku "censer", adagurru "libation vessel" or egubbü "holy water vessel") are excluded by the determinative for wooden items, clearly preserved in ms. b obv. 4.

-

500 Daniel Schwemer

5-6: The use of -sunüti for the dative {tarakkassunüti "you prepare for them", taqabbisunüti "you say to them", cf. also restored tun[aqqä-sunüti]) is not common in Standard Babylonian, but known from Middle and Late Babylonian texts (see AHw 1278a, Aro 1955: 58). Partly restored qem' kasi isarraqsun[üti] in line 32 is best understood as a double accusa-tive construction ("he sprinkles them with /tosu-flour"), c f , e.g., sina nig-nakki riqqi tasarraq "you strew two censers with aromatics" {KAR 26 rev. 15, ed. Mayer 1999: 153).

8: The inclusion of the silver-alloy esmarü within the present list o f various kinds o f 'wood' (line 9) is surprising, but note that the precious types of 'wood' listed in the preceding line (including ivory) were all used for pieces of furniture and their decoration, and the same is true for esma-rü. The spelling of esmarü with mä is not without parallel (see Frahm 1997: 76, line 129: es-mä-re-e).

9: The restoration of anhullü, usually speit ( U ) A N . H Ü L ( . L A ) , is un-certain. The anhullü-plant was regarded as effective against witchcraft (see Schwemer 2007a: 198), but alternatively one could restore [üpi\l-luA-u "mandrake". Note that the list in lines 7-9 comprises eleven items; thus, a reading [x]-x-lum 10 Gism e ä an-nu-ti seems unlikely.

10-11: Potions containing seven drugs are common in Babylonian medicine, and there is no shortage of prescriptions o f this type for potions effective against witchcraft (e.g., LKA 144 rev. 23-28 // , ed. CMAwR I , 2.5, 3.: 1-27; BAM 434 rev. I V 61-69 // , ed. CMAwR I , 7.10.1, 1.: 151"'-59"' ; BAM 161 obv. V 8'-10', ed. CMAwR I , 7.10.1, 3.: 1-3); but none of these prescriptions has exactly the same sequence o f drugs as the present text.

12-13: The restorations follow numerous parallel passages in other anti-witchcraft rituals (for a discussion and a collection of the relevant at-testations, see Schwemer 2007a: 201-202).

14: For the tentative restoration at the beginning of the line, cf. line 22 of the following prayer (salmisunu epus ina mahrikunu elisunu azzTz " I have made figurines representing them, before you I have stepped upon them") and the ritual actions to be performed after the recitation of the prayer (line 31: salam kassäpi kassäpti ina sepisu i[ser] "he [squashes] the figurines of the warlock and witch with his foot").

15-16: The beginnings of these two lines are broken. Given that line 15 must have contained the initial invocation of Sin, while line 16 had a parallel address to Samas, the names of the gods can be safely restored in the breaks; the traces preserved at the beginning of each line are un-ambiguous enough to allow for a confident restoration of the gods' epi-thets. From line 17 to the end of the prayer Sin and Samas are addressed together.

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 501

17: The traces at the end of the line suggest izzizzü; cf. K U B 4, 47 rev. 37 (comm. W. R. Mayer): [sa] rP-na sa-me-e iz-zi-iz-zu "(stars) [that] have appeared in the sky".

18: The collocation asar sipti "site o f judgement" is well known (see CAD S I I I 91b). The form as-ru is probably better interpreted as a con-struct State o f the locative-adverbial than as an irregulär spelling o f asar. Instead of pleonastic ina one could also restore sä at the beginning of the line.

27-28: The independent pronouns sunu and sunüti seem redundant. One might suspect that sunu after lä täbüti is a corrupt addition, triggered by the preceding sequence kispisunu ruhesunu rusü[sunu]; but since both manuscripts agree in their wording, one should refrain from rashly emending the text. The translation offered here is based on the assumption that sunu "they" refers back to the sequence beginning with kispisunu, while sunüti "them" refers to warlock and witch (as does the suffixed pronoun in lisbatüsunüti) and serves to emphasize the object {GAG § 42 f ) .

31: For the use of the verb seru "to Hatten, squash, crush" in contexts such as the present one, cf. KAR 80 = KAL 2, 8 rev. 18 / / (CMAwR I , 8.4: 61), VAT 35 rev. 5-6 (CMAwR I , 8.12: 17-18) and B M 40568 rev. 5 (ed. Schwemer 2009: 58-66).

32: The Akkadian reading of K U preceding kasi remains uncertain, though qemu(z\) "flour", "powder" or siktu "powder" seem most likely (see Borger 2003: 425 ad no. 808 with previous literature). For the con-struction o f saräqu wi th two accusatives, see the note on lines 5-6.

35-36: Even though both manuscripts break the line after same u erseti, there can be no doubt that attunu at the beginning of line 36 be-longs syntactically to the preceding line. I f the object of the sentence be-ginning with ashurkunüsi was expressed by an independent pronoun, it would have to be käsunu (cf. kasi ashurka, see Mayer 1976: 136). The phrase sa naphar same u erseti seems to be an epithet o f Sin and Samas rather than of Anu within the present context.

37-39: Lines 37-38 contain a number of verbal forms ending in -a whose subject must be the evildoers ( D Ü I D twice, is-hu-ra, i-se-'a-a); at the same time it is certain that the subject o f ü-za-an-nu-u in line 39 must be the evildoers too. I f all these verbal forms are interpreted as be-longing to non-subordinate clauses, ü-za-an-nu-u must be interpreted as a 3"' masc. pl . D pret., while the forms ending in -a would have to be taken as 3"' fern. pl. (Tpusä etc.). The only way of avoiding a gender (or number) incongruity between the forms ending in -a and uzannü is to interpret all relevant passages as subordinate clauses; then ipusa, ishura and ise'a

-

502 Daniel Schwemer

would represent 3 r d masc. sg. G pret. forms with the pronominal suffix of the l s t sg. dative ("against me"; subordinative unmarked), while uzannü could be interpreted as 3 r d masc. sg. D pret. wi th the subordinative marker —u (note that no pronominal suffix is expected as the reference to the Speaker is given with ittiyd). I f this interpretation of the verbal forms is correct, a restoration of sa preceding lä dumqa Tpusa at the beginning of line 37 is called for: [sa P\ä dumqa Tpusa tidä "[The one who] has acted malevolently against me, you know (him)". While there seems to be just enough space in the break to allow for this restoration, a syntactical prob-lem is posed by the continuation of the relative clause after tidä without the expected repetition o f sa, and, within this hypothesis, an emendation of the text (preserved only in ms a,) seems inescapable.

40: For the phrase arki D N aläku, see Mayer 1976: 113 and 139. 40-41: I cannot offer a plausible explanation for the presence of the

paragraph divider between these two lines; it is clearly preserved in both manuscripts which, however, may well have been copied from the same original.

41: It remains unclear to me how the beginning o f the line should be restored. It seems not excluded that the line is corrupt; i f so, one could consider the following reading: [purussü(ES.BAR)(?)]mii-ku-nu sä /Ä(NU) (uttakkarü(YJjR)rü) lum-ni-iä rlip-su~i-su... "May your [decision]s that (can)not (be changed) cancel my evils, ... . "

42: Instead of [e-sä-t]i-ia5 one could also restore [dal-ha-t]i-ia5. 43: The object of ina kisädisu tasakkan is certainly the therapeutic

package filled with various kinds of wood whose preparation is detailed in lines 7-9. Traces of K E S are preserved in both manuscripts, with space for one sign or, at the most, two short signs in the preceding break. The tenta-tive restoration [issi ri]ksi is inspired by the wording of the following clause (sammi ina sikari isattimd), taking into account that there is not enough space for a restoration issi ina riksi. Alternatively, one could re-store just [rik]sa([KA.K]Es), but K A . K E S is only rarely used as a logogram for riksu and not attested otherwise within the present text.

44: For the beginning of the line, cf. the prognosis kima ümi inammer "he w i l l be as bright(ly happy) as the day" (LKA 146 rev. 21 / / BAM 313 B line d). For the second half of the line, cf., e.g., BAM 446 obv. 6 (see supra), SpTU 2, 22 + 3, 85 obv. I 37-38 or I V R 2 55/2 obv. 3 (ed. CMAwR I , 8.13); for further relevant attestations and a discussion o f the motif, see Abusch 1985: 97-98, who argues that the phrase should be translated "the one who speaks to him w i l l say 'So be i t ' " (i.e., w i l l react favourably to the patient's requests).

Fighting Witchcraft before the Moon and Sun 503

45: I am unable to give a plausible reading for the damaged sign fol-lowing r D i 1 ? - s « in ms. b. The restoration of the beginning of the line pro-posed above remains highly uncertain, especially since dinu usually pre-cedes purussü when the two words are paired up.

45a: The restoration follows BAM 315 rev. I I I 15 and SpTU 2, 22 + 3, 85 obv. I 45' (prognoses for bewitched persons, ed. Abusch 1999: 42, 43-44); cf. the phrase itti bäri u sä'ili dinsu lä isser "his (oracular) de-cision obtained from diviner and seer does not turn out wel l " in a number of symptom descriptions, most of them relating to witchcraft-induced illnesses; in addition to BAM 315 rev. I I I 7-8 / / Bu 91-5-9, 214: 9' (ed. Abusch 1999: 40-42), cf. BAM 315 obv. I I 15, BAM 468 obv. 2 and STT 95 + 295 rev. I I I 136 / / B M 64174 obv. 6 (ed. Abusch 1999: 38-39). For a brief discussion of these passages, see Mayer 2008: 104-5.

References

Abusch, T. 1985. Dismissal by Authorities: suskunu and Related Matters, JCS 37: 91-100.

Abusch, T. 1987. Alaktu and Halakhah. Oracular Decision, Divine Revelation, Har-vard Theological Review 80: 15-42.

Abusch, T. 1999. Witchcraft and the Anger of the Personal God, in: Mesopotamian Magic. Textual, Historical, and Interpretative Perspectives (AMD 1), ed. T. Abusch - K. van der Toorn, Groningen, 83-121.

Abusch, T. and D. Schwemer 2011. Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Ritu-als, vol. I (AMD 8/1), Leiden/Boston.

Annus, A. 2002. The God Ninurta in the Mythology and Royal Ideology of Ancient Mesopotamia (SAAS 14), Helsinki.

Aro, J. 1955. Studien zur mittelbabylonischen Grammatik (StOr 20), Helsinki. Black, J. A. - G. Cunningham - J. Ebeling - E. Flückiger-Hawker - E. Robson -

J. Taylor - G. Zölyomi, G. 1998-2006. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sume-rian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford.

Uöck, B. 1995. Sumerisch a.rä und Divination in Mesopotamien, Aula Orientalis 13: 151-59.

Uorger, R. 1971. Zum Handerhebungsgebet an Nanna-Sin IV R 9, ZA 61: 81-83. Borger, R. 2003. Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon (AOAT 305), Münster. Kbeling, E. 1949. Beschwörungen gegen den Feind und den bösen Blick aus dem

Zweistromlande, ArOr 17/1: 172-211. Kllis, R. S. 2006. Well, Dog My Cats! A Note on the Uridimmu, in: If a Man

Builds a Joyful House. Assyriological Studies in Honor of Erle Verdun Leichty, ed. A. Guinan et al. (CM 31), Leiden/Boston, 111-26.

Farber, W. 1977. Beschwörungsrituale an Istar und Dumuzi. Attl Istar sa harmasa Dumuzi (Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Veröffentlichungen der orientalischen Kommission 30), Wiesbaden.

Frahm, E. 1997. Einleitung in die Sanherib-Inschriften (AfO Beiheft 26), Wien. Geller, M. .). 1988. New Duplicates to SBTU II , AfO 35: 1-23.

-

504 Daniel Schwemer

Lambert, W. G. 1960. Babylonian Wisdom Literature, Oxford. Mayer, W. R. 1976. Untersuchungen zur Formensprache der babylonischen „ Ge-

betsbeschwörungen " (Studia Pohl, series maior 5), Rome. Mayer, W. R. 1992. Das "gnomische Präteritum" im literarischen Akkadisch, OrNS

61: 373-99. Mayer, W. R. 1993. Das Ritual BMS 12 mit dem Gebet "Marduk 5", OrNS 62: 313-

37. Mayer, W. R. 1999. Das Ritual KAR 26 mit dem Gebet "Marduk 24", OrNS 68:

145-63. Mayer, W. R. 2005. Das Gebet des Eingeweideschauers an Ninurta, OrNS 74: 51-

56. Parpola, S. 1983. Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and As-

surbanipal. Part I I : Commentary and Appendices (AOAT 5/2), Kevelaer/ Neukirchen-Vluyn.

Reiner, E. 1956. Lipsur Litanies, JNES 15: 129-49. Reiner, R. 1958. Surpu. A Collection of Sumerian and Akkadian Incantations (AfO

Beiheft 11), Graz. Römer, W. H. Ph. 2003. Miscellanea Sumerologica V Bittbrief einer Gelähmten um

Genesung an die Göttin Nintinugga, in: Literatur, Politik und Recht in Meso-potamien. Festschrift für Claus Wilcke (Orientalia Biblica et Christiana 14), ed. W. Sallaberger - K. Volk - A. Zgoll, Wiesbaden, 237-49.

Schaudig, H. 2001. Die Inschriften Nabonids von Babylon und Kyros' des Grossen samt den in ihrem Umfeld entstandenen Tendenzschriften. Textausgabe und Grammatik (AOAT 256), Münster.

Scheil, V 1902: Une saison de fouilles ä Sippar (MIFAO 1/1), Cairo. Schwemer, D. 2007a: Abwehrzauber und Behexung. Studien zum Schadenzauber-

glauben im alten Mesopotamien (Unter Benutzung von Tzvi Abuschs Kri-tischem Katalog und Sammlungen im Rahmen des Kooperationsprojektes Cor-pus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals), Wiesbaden.

Schwemer, D. 2007b: Keilschrifttexte aus Assur literarischen Inhalts I I : Rituale und Beschwörungen gegen Schadenzauber (WVDOG 117), Wiesbaden.

Schwemer, D. 2009: Washing, Defiling and Burning: Two Bilingual Anti-witchcraft Incantations, OrNS 78: 44-68.

Scurlock, J. 2006. Magico-Medical Means of Treating Ghost-Induced Illnesses in Ancient Mesopotamia (AMD 3), Leiden/Boston.

Sjöberg, Ä. 1960. Der Mondgott Nanna-Suen in der sumerischen Überlieferung. I . Teil: Texte, Stockholm.

Soden, W. von. 1990. "Weisheitstexte" in akkadischer Sprache, in: Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testamentes Will, ed. O. Kaiser, Gütersloh, 110-88.

Tallqvist, K. 1938. Akkadische Götterepitheta. Mit einem Götterverzeichnis und einer Liste der prädikativen Elemente der sumerischen Götternamen (StOr 7), Helsinki.

School of Oriental and African Studies Dept. of the Near and Middle East Thornhaugh Street - Russell Square London WC1H OXG

Orientalia Stylesheet

1. Contributions should be sent to The Bditor, Orientalia, Pontifical Biblical Institute, Via della Pilotta 25, 1-00187 Rome, I taly.

2. Contributions should be typewritten, with double-spacing, on one •ide of the paper only, wi th ample margins all around. For articles, foot-notes should be placed on separate pages with consecutive numeration. I n reviews, footnotes are not used; all material should be i n the main text.

3. (a) I n referring to books and articles, authors should use the abbrevia-. tions of Orientalia 36 (1987) xxii i -xxvii i or those contained in a Standard list for a particular field of studies: for Egyptian and Coptic, the Lexikon der Ägyptologie, and as far as this lacks Coptic titles, also Koptisches Handwörter-buch; for Mesopotamian studies, Chicago Assyrian Dictionary and von Soden, Akhadisches Handwörterbuch; for Hitt i te, Friedrich-Kammenhuber, Hethi-tisches Wörterbuch* and Chicago Hittite Dictionary.

(b) Titles not i n the Standard lists should be given fully on their first occurrence, and in an abbreviated form thereafter.

(c) Examples of bibliographic references on first occurrence: [book] A. Falkenstein, Grammatik dpr Sprache Gudeas von Logas": I . Schrift- und For-menlehre (AnOr 28; Rom »1978) 128-133. rpart of a book] W. G. Lambert, "The Problem of the Love Lyrics", in: H . Goedicke - J. J. M. Roberts (ed.), Unity and Diversity (Baltimore/London 1975) 98-135. [article] P. Steinkeller, "Notes on Sumerian Plural Verbs", Or 48 (1979) 54-67.

(d) Examples of later abbreviated reference: Falkenstein, Grammatik I 53; Lambert, in: Unity and Diversity 104; Steinkeller, Or 48, 65-66.

4. Special types are indicated for the printer by underlining as follows: italics - SMAW, CAPS - sP_a_ced - darkfoce. Authors are requested not to

indicate these in any other way (for instance with I B M italic element). 5. Please note (3 above) that authors' names are given in roman [not

•mall caps). Note also that Latin abbreviations are given in roman, not Italics: cf., e.g., et al., etc., ibid., i.e., loc. cit., N.B., s.v. Please use "loc. cit." (op. cit., a.a.O.) only in reference to an immediately preceding mention.

6. When Egyptian hieroglyphs are included in an article, the author •hould add in pencjl an interlinear identification of each hieroglyph according to the Gardiner classification System. When a Special hieroglyph (one not included in Gardiner's list) is needed, a drawing suitable for engraving should accompany the manuscript. Such cliches however should be used only when ubsolutely indispensable.

7. Contributors are expected not to make additions or deletions on proofs. 8. In reading proofs, contributors are asked to correct false word-diyision

at ends of lines.

Thll periodical is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, published by American Theological Library Association, 250 S. Wacker Dr., 16,h Fix., ago, I L 60606. E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.ada.com/

-

Addendum (25 x 2012) Since the publication of this article, a photo of BAM 326 has been published on the CDLI website. Collation of the photo confirms most of the readings and the overall interpretation given on p. 495: line 7′: read baliṭ(TI.LA)-ma line 12′: The reading ki-ṣir libbi(ŠÀ) ilī(DINGIR)-šú is confirmed; no emendation is required. At the beginning of the line, one could also simply read itti(KI) instead of the proposed emendation libbi(ŠÀ![ki]). As H. Stadhouders points rightly out to me, instead of šú-lum-me, a reading ana SILIM-me seems more likely. line 13′: The proposed reading ana paṭāri is confirmed: [a-n]a ⌈DU8-ri⌉.