Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food ...

Transcript of Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food ...

239

季刊地理学 Vol. 66(2015)pp. 239-254Quarterly Journal of Geography

*Hitotsubashi University

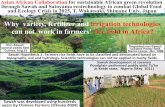

Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food

Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

Shiro Kodamaya*

Abstract This paper discusses the development of dry season irrigation farming in the village. I first reviews government agricultural policies in Zambia since the 1960s, which have

substantially influenced farming in the village. And then I sheds new light on the ongo-

ing discussion on the positive effects of irrigation systems on the use of improved maize

seeds and fertilizer. “Green Revolution” types of innovations have been partially real-

ized in the village, but that have expanded income disparities among farmers. Conse-

quently, farmers’ reliance on subsidized inputs has increased, which has brought about a

new type of vulnerability.

Keywords Irrigation farming, Green revolution, Zambia, vulnerability, smallholder

1. Introduction

The paper explores how a Green Revolution

type of agricultural innovation such as the use of

chemical fertilizers and the development of small-

scale irrigation is effective in improving small-

holder household food security in Zambia. While

utilization of this innovation has been limited in

small-scale farming, it is indispensable for the

countr y’s food secur i ty and agr icu l tura l

development.

The paper takes the case of a village in central

Zambia where the majority of farmers practice

small-scale irrigation farming in the dry season,

together with upland maize farming in the rainy

season. Farming in the village is a combination

of different types : rainfed and irrigated ; upland

farming and wetlands gardening ; maize farming

and vegetable growing ; subsistence farming and

production for the market ; and crop production

and livestock rearing. In this context, small

farmer household food security is not a simple

function of staple food production and consump-

tion, but it should be set in groups of different

farming activities. Furthermore, small farmers

engage in non-farming activities which also affect

the food security of their households. The paper

aims to explore how policies to support the use of

chemical fertilizer and irrigation development for

small-scale farmers can affect the household food

security of these people in the context of multi-

component farming. It will illustrate how access

to fertilizer and irrigation influences different

components of small farming.

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

240

1.1 Household food security of small-

scale farmers

The food security of small-scale farmers is

basically dependent on their ability to produce suf-

ficient amounts of food crops in their fields for

their own consumption (subsistence farming).

However, other farm and non-farm activities can

contribute to food security by providing sources of

purchasing food. Those farmers who do not pro-

duce enough for subsistence can purchase food.

The sources of income to purchase food include

off-farm work, sales of natural or processed prod-

ucts, and remittances (UN Millennium Project

2005 : 153). One can add cash crop production

as a source of income to purchase food. Cash

crop production and non-farm activities can also

contribute to improvement in household food

security through providing sources of income to

purchase inputs for food production such as seeds

and fertilizer.

The paper focuses on the importance of farm

and non-farm activities which can affect house-

hold food security by providing income sources for

two functions : to purchase food for consumption

and inputs for food production.

1.2 Multiple farming components and the

market, policy and ecological environ-

ment

Smallholder livelihood activities are composed

of multiple farming and non-farming activities.

Traditionally, people utilized natural resources in

multiple ways such as farming (crop cultivation),

livestock rearing, and hunting and gathering, and

one of the functions of this multiplicity was risk

aversion under ecological uncertainties, which

made their livelihood resilient. While tendencies

to specialize on one activity exist in the present

day context, factors such as integration of rural

areas into national and global economies and poli-

tics, the development of a market economy, urban-

ization and migration, and development interven-

tions of government and non-governmental

organizations have contributed to new activities.

These include production for the market ; farming

with modern inputs such as hybrid seeds, chemi-

cal fertilizer and irrigation ; and non-farm eco-

nomic activities such as trading in agricultural

produce, and employment in urban centers.

1.3 Improved seeds and fertilizer

A Green Revolution type of agricultural innova-

tion combining the use of chemical fertilizers and

improved varieties of seeds on the one hand, and

the development of irrigation on the other, con-

tributed to the increased food production and

improved food security in many countries of Asia

and Latin America. However, it has had limited

impact on small-scale farmers in sub-Saharan

Africa. In Asian countries the Green Revolution

was regarded as making a significant contribution

to sustained yield growth, but experience in Africa

was mixed in terms of raising rural incomes and

lowering rura l vulnerabi l i ty (El l is et a l .

2009 : 34).

One explanation for the differences in perfor-

mance may be the lack of an irrigation develop-

ment component in Af r i can agr icu l tura l

innovations. In African countries including Zam-

bia, the policy to propagate the improved seeds

and fertilizer technology among small-scale farm-

ers was promoted without the development of

small-scale irrigation. It might be the case that

sustained yield growth from increased use of

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

241

improved seeds and fertilizer has not materialized

in Africa because it often resulted in crop failure

under the unstable and unpredictable conditions of

rainfed agriculture.

1.4 Irrigation

Scholars and development practitioners advo-

cate irrigation as an important means to achieve

increased agricultural production and food secu-

rity in Africa. In a region such as sub-Saharan

Africa where droughts are prevalent, irrigation

could be a key factor in enhancing food security.

In the publication African Environment Outlook, it

is argued that rapidly increasing the area under

irrigation, especially small-scale irrigation, will

provide farmers with opportunities to raise output

on a sustainable basis (UNEP 2006 : 84-5). Irri-

gation (mainly small-scale) is advocated as an

example of “sustainable intensification” of agricul-

ture in southern Africa, where agricultural growth

depends upon intensification rather than “extensi-

fication” (FFSSA 2004 : 68). Thus irrigation is

considered to be “sustainable” and contribute to

poverty reduction among small farmers.

2. History of Rainfed Maize Production

with Improved Seeds and Fertilizers in

Zambia

2.1 1960s to 1980s : state guaranteed

market and diffusion of maize produc-

tion

At the time of Independence in 1964 Zambia

inherited an economy heavily dependent on cop-

per-mining that contributed to 90% of the total

exports. The agriculture sector had the dual

structure composed of a small number of large-

scale commercial farms and a large number of

small-scale farms that were engaged in subsis-

tence farming. Since Independence, develop-

ment of maize farming by small-scale farmers ─

the majority of the rural inhabitants ─ was the

centerpiece of the agricultural and rural develop-

ment of Zambia. The government promoted

improved maize seed varieties and chemical fertil-

izers among small-scale farmers. In the period

of Kaunda-UNIP rule from the 1960s to 1980s,

government policies to support maize production

with hybrid seeds/chemical fertilizer technologies

among small-scale farmers included marketing,

and policies to subsidize both producer and fertil-

izer prices. The development of irrigation was

not integrated into the package of improved seeds/

fertilizer technologies which aimed to enhance

maize production and productivity. Conse-

quently, small-scale farming remained reliant on

rainfed maize production, which was vulnerable to

weather conditions such as droughts and rainfall

patterns. During the period of the Second

Republic, marketing boards such as the Namboard,

and cooperatives provided a guaranteed market,

purchasing maize at a fixed pan-territorial price

(Dorosh et al. 2010 : 186).

In the 1970s and 1980s government support for

maize production among small-scale farmers

resulted in increased maize production as well as

spatial diffusion of marketed production of maize

toward remote areas. Government initiatives,

including price and marketing support, resulted in

increased government expenditure on subsidies.

By the 1980s structural adjustment programs

made continued expenditures on subsidies for

maize production difficult, and then unsustainable

(Howard & Mungoma 1997 : 45).

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

242

Lack of diffusion of irrigation among small-scale

farmers could have undermined the effects of high

yielding varieties and chemical fertilizers on

increased production and productivity. The adop-

tion of high-yielding varieties and chemical fertil-

izers failed to achieve stable food production and

increased productivity due to weather conditions

such as drought.

2.2 Liberalization of maize marketing and

input distribution : 1990s.

After the 1991 multi-party general election,

President Chiluba and the Movement for Multi-

party Democracy (MMD) came to power. This

government implemented economic liberalization

and de-regulation policies. Economic stagnation

continued, with the deterioration of formal sector

employment due to economic liberalization

policies.

Following the 1991 election, the government

embarked on agricultural policy reforms as part of

the structural adjustment programs. The main

change in agricultural policy entailed liberalization

of the maize price and marketing. Although the

Zambian government liberalized marketing of

agricultural produce, with regard to agricultural

inputs government continued its involvement in

marketing through various programs.

2.3 Input subsidies : 2000s

In 2001 President Mwanawasa’s government

came to power with a slogan of New Deal seeking

to fight poverty and corruption. President Mwa-

nawasa stressed the importance of agriculture in

his vision of agriculture-centered development

(Zambia 2002b). The Zambian economy recov-

ered and grew, thanks to a series of events such

as increased copper production since 2000, surg-

ing copper prices in the world market since 2004,

and cancellations of external debt in 2005.

The prescriptions for structural adjustments

that donors have imposed on Africa led to the

elimination of fertilizer subsidies in the 1990s.

However, fertilizer subsidies attracted renewed

attention in Africa in the 2000s with arguments in

favor of using input subsidies as a way of stimulat-

ing increased agricultural productivity growth or

achieving welfare goals (Morris et al. 2007 : 113).

Zambia has re-established national fertilizer sub-

sidies (the Fertilizer Support Program, FSP), as

well as introducing an input package scheme (the

Food Security Pack) specifically aimed at farmers

who are too poor to purchase fertilizer, even at

subsidized prices (Ellis et al. 2009 : 33). In

2002, the Government of Zambia initiated FSP,

which aimed to improve viable resource access to

agricultural inputs by poor smallholder farmers

organized in cooperatives (FFSSA n.d.). Instead

of providing fertilizer through agricultural credit,

FSP was to subsidize fertilizer purchases by farm-

ers’ groups.

In 2009/2010, 292,662 FSP beneficiaries pur-

chased 69,100 tons of fertilizer, compared with

350,935 farmers who purchased 94,028 tons of

fertilizers through commercial purchases (FSRP/

ACF & MACO/Policy and Planning Department

2010). Thus, FSP contributed 40-50% of fertil-

izer distribution.

A review of the FSP (ZACF 2009), led by senior

civil servants in the ministries of the Zambian

government, noted a number of concerns about

the past performance of the FSP, which included :

Poor targeting of farmers (beneficiaries) ;

Impact on household and national food security

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

243

(because of weak monitoring mechanisms, it was

not easy to measure the FSP impact) ;

[Negative] effect on private sector investment

and participation (a limited number of fertilizer

companies have been able to participate) ;

[Concerns on] the program’s long-term

sustainability ; and

Policy inconsistencies (especially with regards

to level of subsidy and farmer graduation).

(ZACF 2009 : 6 ; Gould 2010 : 136)

2.4 Promotion of irrigation farming

In Zambia irrigation development policies were

formulated and implemented independently of

improved seeds/fertilizer technologies for maize.

Under rainfed agriculture, the seeds/fertilizer

technologies require complementary circum-

stances to reduce vulnerability, particularly

because the amount and pattern of rainfall must

be favorable for crop growth and maturation (Ellis

et al. 2009 : 33). When events are not so favor-

able, input (fertilizer/seeds) subsidies are an

expensive way to fund crop failure (Ellis et al.

2009).

The PRSP (Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper)

of 2002–2004 has stated that the expansion of irri-

gation would not only improve food security but

would a lso help reduce pover ty (Zambia

2002a : 91). The Fifth National Development

Plan 2006-2010 (FNDP) set a target of doubling

the acreage under irrigation to 200,000 ha by 2010

(Zambia 2006 : 49). The National Irrigation Plan

(NIP), formulated in 2005, proposed a strategy for

efficient and sustainable exploitation of water

resources by promoting irrigation. As an inter-

vention to improve the policy and legal environ-

ment, the NIP proposes a reduction in energy and

irrigation equipment costs and improved incen-

tives for investing in irrigation.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organi-

zation (FAO) of the United Nations, about 100,000

ha were estimated to be under so-called tradi-

tional irrigation in 1992 (Daka 2006). These

wetlands and dambo (low-lying, shallow wetlands)

in traditional areas of land tenure have been used

for rice, fruit, and vegetable production.

There have been several programs promoting

small-scale irrigation that were supported by the

government, non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) and donors. NGOs have played a partic-

ularly important role in mobilizing traditional

farmers and emergent farmers to adopt irrigation

practices (Daka 2006).

3. Agriculture in Village C

3.1 Research site

The study area is a village in Chibombo District

of Zambia’s Central Province. Recently, field

research was carried out in August 2009 and

December 2010 when at each round of research

16 and 13 household heads or their wives were

interviewed to collect data on such items as har-

vests of maize and other crops, and consumption

and sales of maize. The households interviewed

were not selected following the random sampling

procedure, and as such, they are not statistically

representative sample.

The village studied (hereafter called “Village

C”) was established in the mid-1970s. The loca-

tion was previously covered with forest, which

was gradually cleared for villages as people

migrated into and settled in the area. Village C

included approximately 120 households by the

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

244

mid-1990s, and 150 households with a population

of 1,300 in 2010.

Maize continues to be the most important cash

crop as well as food crop for the majority of small

farmers in Zambia. While maize is an important

crop in Village C, vegetable production is one of

the main farming activities. The area around the

village is abundant in dambo, which are utilized by

farmers for growing crops such as tomatoes,

watermelons, and rape. In Village C many farm-

ers combine rainfed farming in the uplands with

irrigation farming in dambo, with the latter being

conducted mainly in the dry season. In the early

1990s when we first conducted field research in

the village, around half of the farmers there uti-

lized dambo for vegetable production (Hanzawa

1995).

Both farming activities can be complementary

in two respects. First, dambo gardening is a dry-

season activity that does not compete for labor

and land with upland farming and other activities.

Second, the two activities can be interconnected

in such a way that the revenues from vegetable

sales are used for purchasing maize production

inputs for the rainy season. Combining both

types can provide farmers with the basis for more

stability in income and farming by increasing the

resistance to various shocks emanating from

weather changes and market fluctuations. Prac-

ticing two different types of farming can contrib-

ute to stability in food availability and income of a

farming household by increasing the sources of

food and income.

However, rainfed maize farming and vegetable

growing can both face a different set of climatic

uncertainties (related to environmental shocks)

and market uncertainties (related to market and

policy shocks). Even after the liberalization of

maize marketing system, the maize price fluctua-

tions were more predictable than those of

vegetables. In contrast, while vegetable produc-

tion in dambo land is more drought-resistant than

upland cultivation, farmers are faced with volatile

prices at vegetable markets. This makes reve-

nues realized from vegetable growing less

predictable. Since vegetables are perishable, and

given the lack of cold storage facilities, vegetable

growers face the risk of being forced to sell their

produce at giveaway prices or see their crops rot-

ting away in their gardens.

Both rainfed maize farming and irrigated dambo

farming demand resources and inputs to gain

higher production and productivity. In addition

to land and labor, cattle and implements such as

ploughs are required to cultivate land. In the

Central Province as well as in the Southern and

Eastern Provinces, maize and other major crops

are cultivated using ox-drawn ploughs. For

dambo farming, if one wants to expand vegetable

cultivation or the stable irrigated production of

crops, equipment such as treadle and engine

pumps, are required.

4. The Development of Irrigation Farm-

ing in Village C

4.1 Bucket irrigation in seepage zones of

dambo

While government policies to promote small-

scale irrigation started to develop only after the

2000s, farmers in the areas of Village C practiced

irrigated vegetable production in the dry season

before the 2000s, when most of them depended

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

245

upon bucket irrigation. Since the plots of crops

are located in dambo, and the system does not

accompany any development of specific plots for

irrigation and furrows, water control is limited.

As such, the plots were often flooded and crops

damaged by floods when the rainy season started.

This type of irrigation places some limits on the

duration and areas of cropping, which is confined

to the mid-period of the dry season when the land

surface becomes dry without flooding, and is

restricted in area to the low wetlands.

4.2 Treadle pumps and plot development

Irrigation farming in Village C entered a new

stage with the start of the new millennium. In

2001 an NGO came to the village and organized

some farmers into a group to initiate a small-scale

irrigation project. The NGO introduced a new

irrigation method utilizing treadle pumps and spe-

cific plots with furrows for irrigation. It extended

credit for farmers to buy treadle pumps, and

trained them in irrigation management and treadle

pump operation and maintenance.

The introduction of the treadle pumps had some

important social and economic implications in the

village. Those farmers who were assisted by the

NGO obtained a material and technological base

for modern irrigation farming, as they acquired a

treadle pump and were trained in plot develop-

ment and irrigation methods. Thanks to the

credit, the farmers were able to get pumps which

could contribute to the expansion of their irriga-

tion farming. The new irrigation method

entailed a plot development for irrigation which

enabled effective water control, leading to more

stable production. Treadle pump irrigation

enabled expansion of irrigation farming of the

project member farmers and contributed to their

material accumulation, while non-project member

farmers were left out of the development and

accumulation.

4.3 Engine pumps

Another development in irrigation methods in

Village C occurred around 2005, when a growing

number of farmers began to purchase engine

pumps. By 2008, about 12 farmers were practic-

ing irrigation farming using these pumps. In

fact, many of the engine pump owners were those

who had bought treadle pumps in 2001. In other

words, there was a shift from treadle to engine

pumps among those farmers who practiced pump

irrigation. This implied the further development

and accumulation in farming by those who first

improved their irrigation with the use of treadle

pumps. In fact, some of those farmers with

engine pumps invested in building a small dike or

dam in their land, while others in constructing

water tanks or water reserve to pool water for

irrigation.

5. Household Food Security in Village C

5.1 Rainfed maize in the uplands

As already noted, farmers in Village C practice

rainfed maize cultivation in the uplands, with the

majority growing crops in dambo in the dry

season. For farmers to obtain staple food─ that

is, maize ─ directly, they can grow maize in the

uplands, while some grow dry-season irrigated

maize in dambo.

One of the most salient features of rainfed

maize farming is the volatility of maize production.

The field research has found that at household

level, harvests from rainfed maize farming in the

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

246

uplands fluctuated annually depending mainly on

fertilizer availability and weather conditions, but

also other factors such as availability of labor and

cattle for ploughing.

As shown in Table 1, most of the farmers inter-

viewed experienced fluctuations in upland maize

harvests. For most of the years between

2007/2008 and 2009/2010 most of the households

were deficient in upland maize, in the sense that

the upland maize harvest was less than the

amount of maize required to feed the members of

the household. While 13 out of 14 households

interviewed were deficient in maize (maize pro-

duction in dambo was not included in calculation)

in 2007/08, 13 out of 17 sample households in

2008/09 were deficient. The 2009/2010 season

saw bumper harvests all over Zambia, and also out

of 13 sample households of Village C, 7 house-

holds recorded maize surplus, although 6 house-

holds were maize deficient. Maize harvests at

household level fluctuated widely. For instance,

maize harvests of Household A ranged from

250 kg in 2008 to 4,300 kg in 2010. Maize har-

vests of Household P decreased from 500 kg in

2008 to 200 kg in 2009, and increased to 1,610 kg

in 2010. Since 750-1,000 kg of maize was esti-

mated to be required for the annual consumption

for the household, the harvest of 200 kg in 2009

was not sufficient to feed the family throughout a

year. They bought 400 kg of maize with their

revenue from vegetable sales.

5.2 Factors causing fluctuations in maize

production

The fluctuations in production included both

ecological and economic factors among which

weather changes (such as flood and drought) and

shortages of fertilizer were the two reasons most

frequently mentioned by the farmers of the inter-

viewed farmers were concerned.

Some farmers reported declines in maize pro-

duction in 2009 due to floods. Both drought and

excessive rain or flooding affected farm produc-

tion of the area, depending on the season.

Availability of inputs such as fertilizer and seeds

affected maize production. Farmers in Village C

had several ways to obtain these. In the mid-

1990s, just after the liberalization of maize mar-

keting, some schemes and lending institutions

extended agricultural credit and some farmers in

Village C obtained this credit. However, many

farmers failed to repay because they did not

achieve sufficient maize production due to drought

or late delivery of fertilizer. Nevertheless, pri-

vate lending institutions were strict in collecting

repayment from farmers, including confiscation of

debtors’ assets such as ox-carts and ploughs.

After some years of these events, there were few

agricultural credits extended in Village C, and the

majority of farmers obtained inputs through

purchase. Many of those farmers with vegetable

production in dambo purchased inputs with reve-

nues from irrigation farming in these lands.

Some farmers depended on their relatives in

urban areas to buy fertilizer.

Another way to purchase inputs was to apply

for government and NGO input support schemes.

In 2010 there were three farmers’ groups in the

village with access to the government’s FSP.

However, they had problems such as late delivery

of fertilizers and the small amount of fertilizer

provided. While the late delivery of fertilizer

was caused by factors at the national level, it

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

247

aroused a suspicion among some members who

suspected that leaders of their group misappropri-

ated some fertilizer.

Some farmers suffered from lack of livestock,

which caused low production of maize. As those

farmers without draught animals could plough and

plant their fields only after owners of cattle had

done theirs, they face delays in planting maize.

Shortages of labor affected the farming of some

from Village C. A female farmer aged around 60,

who lived with her sister, mother, daughter and

two grand-children, also faced fluctuation of maize

harvests (Household D). She managed to har-

vest 500 kg (10 bags) of maize in 2009 and 200 kg

(4 bags) in 2010, but had no harvest of maize in

2008 because she planted late (in late December).

Table 1 Growing Maize in the Uplands and Dambo for three years from 2007/2008 Village C

house- hold

Rainfed upland maize harvests (kg)maize in dambo

2008 2009 2010

C 400 500 Grown in 2009

D 0 500 200 Growing maize in 2010 that is the only crop in dambo. For con-sumption.

E 50 500 600 No crops grown in dambo because of labor shortage.

F 500 150 500 No crops grown because he was sick.

G 1,500 1,500 to 2,000 750 No maize in dambo.

H 900 100 - No maize in dambo.

I 0 250 - No maize in dambo.

J 540 450 - Sales of green maize raised K1.2 mil. Ten units# of green maize consumed.

K 750 1,000 750 Some maize grown

P 500 200 1,610 Green maize in 2009, but no crops in 2010.

A 250 450 to 600 4,300 Maize for home consumption was grown. No sales of produce in dambo gardens in 2009. Shortage of water in dambo.

B 3,000 400 7,500 Sales of 1500 units# of green maize in 2009 raised K15 mil. Sales of 800 units of green maize in Sept. 2010 raised K8 mil..

L 1500 5,500 4,388 In 2009 200 units# of green maize harvested, out of which 182 units sold.

M - 1,400 2,300 No maize in dambo.

N - 3,000 1,000 No maize in dambo.

O - 500 1,000 No maize in dambo.

Note : Cells in light shade indicate that the household was in maize deficits, that is : upland maize harvests were not sufficient to feed the household member.Cells in deep shade indicate the household was in maize surplus ; that is : upland maize harvest was more than required for consumption.K= kwacha (the Zambian currency).Mil.= million.-= no data or data was not collected.#Unit of green maize is composed of 10 maize cobs.

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

248

The household suffered a problem of labor short-

ages as there was no adult male labor in the

household.

Shortages of labor were sometimes caused by

sickness of relatives, and resulted in declines in

maize production. An interviewed farmer

reported that his maize production declined

because his brother and sister, who lived in urban

areas, became sick and he had to go and attend

them (Household C).

As the majority of respondents indicated more

than one factor that caused declines in production,

it seemed that often several factors combined to

cause declines in maize harvests, such as short-

age of fertilizer and labor ; excessive rain and

labor shortage ; and lack of fertilizer and cattle.

5.3 Dry season maize

Growing winter maize (dry-season maize) is a

new development which began in around 2000,

and the number of growers increased during the

course of the 2000s, although farmers growing

winter maize in dambo are the minority even

today. In addition, winter maize is grown not

only for home consumption, but is sold as “green

maize” (maize cobs) mainly at the urban markets.

For instance, household L of Table 1 sold 182

units of green maize out of 200 units harvested.

Green maize from dambo can be sold at higher

prices than rainfed upland maize sold in May or

June. One farming household (Household L)

sold 3,500 kg of maize harvested from the uplands

at 3.5 million kwacha, whereas sales of green

maize from dambo fetched 4.48 million kwacha.

While a farmer of Household B sold 7,500 kg (150

bags) of maize harvested from his upland fields

which raised 4.5 million kwacha, green maize from

dambo raised 15 million kwacha (1,500 units) in

2010 and 8 million kwacha (800 units) in 2009.

Green maize from dambo is mainly for sale, but

can be consumed as an additional food to supple-

ment home consumption.

5.4 Income sources to purchase food

Some farmers purchased food or fertilizer with

the money earned by selling vegetables grown in

their dambo gardens, while others made their pur-

chases with off-farm income. The most popular

off-farm economic activity was petty trading. In

some households, women were engaged in the

petty trade of selling vegetables at the roadside

market about 5 km away from the village.

As shown in Table 2, sources of money to pur-

chase food or inputs to produce food included sell-

ing vegetable and other crops grown in gardens,

petty trading and remittances. Household P,

when faced with food shortages, bought maize

with the money realized by selling vegetables

grown in its dambo garden. The households E

and H bought maize with money earned by selling

watermelons and other vegetable.

Some households were dependent on the remit-

tances of their relatives who lived in urban areas.

Households D and F bought maize and fertilizer

with the remittances from relatives living in

towns. A farmer interviewed depended on her

son who lived in an urban area to buy fertilizer for

m a i z e p r o d u c t i o n , a n d m a i z e m e a l f o r

consumption.

5.5 Irrigation

Irrigated farming can relieve the risks of rainfed

maize farming and contribute to improved food

security either through food or income smoothing

or by financing input purchase for rainfed maize

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

249

Table 2 Harvests of maize and strategies to get food (maize)

House- hold

Harvests of rainfed upland maize (kg) Vegetable grown in dambo Non-farm income such as

petty trade Strategies2008 2009 2010

C 600 400 500 Tomato sales K40,000 in 2009.

Wife's sister sells toma-toes at roadside -

D 0 500 200 Has a garden but no crops grown in 2008. Selling knitted clothes

Maize and fertilizer were bought with remittances from relatives living in

towns

E 50 500 600

No crops grown in 2008 because the household head was busy securing

maize

Bought maize with money earned from sales of

watermelons.

F 500 150 500No crops grown in 2008 because the household

head was sick.

A daughter of household head sells vegetable at

roadside.

Remittances from another daughter of household

head who lives in a town

G 1,500 1,500 to 2,000 750

K6.4 mil. of watermelons sold in 2010.K 0.1 mil. of tomatoes and K0.2 mil. of

watermelons in 2008.

Head is a mechanic To buy maize with money earned as a mechanic

H 900 100 -Watermelons and toma-

toes. K0.52 mil. of watermelons sold in 2008.

NoneTo buy maize with money

earned by selling veg-etables

I 0 250 - Tomatoes and rape Selling fish. Sells fish at home.

J 540 450 -Tomatoes, water melons and rape. Tomato sales

K.0.25 mil. None

Shortage of food is not a problem because you just

go to dambo to plant vegetables to sell.

Q 300 500 - Impwa*, green pepper and watermelons

Wife of the head sells veg-etable at roadside

Bought maize with revenues from ox-cart

hiring out

K 750 1,000 750

Green pepper, tomatoes, rape and onions sold in 2010 with a total sales

K1.2 mil.

Petty trade selling tomatoes and maize

P 500 200 1,610 Green pepper and cabbage sales K1.9 mil. in 2008.

Head’s wife sells veg-etable

Bought maize with money from sales of dambo

vegetable

A 250 450 to 600 4,300 Tomatoes, water melons.

Sales K3 mil.

Selling vegetable at roadside raises K0.4 mil.

per month

B 3,000 400 7,500Tomatoes, green pepper

and butternuts. Sales K1.35 mil. in 2009

Head’s wife sells veg-etable.

L 1,500 5,500 4,388 Tomatoes, impwa* Head’s wife sells veg-etable

Note : Cells in light shade indicate that the household was in maize deficits, that is : upland maize harvests were not sufficient to feed the household member.Cells in deep shade indicate the household was in maize surplus ; that is : upland maize harvest was more than required for consumption.K= kwacha (the Zambian currency).Mil.= million.-= no data or data was not collected.*Impwa is a local vegetable that is a type of eggplant.

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

250

production. In the case study village, the devel-

opment of dry-season irrigation farming combined

with rainfed maize production contributed to

increased income and improved food security.

However, irrigation farming has its own vulnera-

bilities such as price fluctuation and damages by

floods and crop disease. In addition, it requires

resources to purchase inputs and invest in pumps

and development of plots, dams, and water tanks.

Relatively well-off farmers can afford such pur-

chases and investment. To reduce the risk of

price fluctuations of produce and crop disease, it is

useful to grow a variety of crops in irrigated plots.

In the mid-1990s crops grown by Village C farm-

ers in their dambo gardens included tomatoes,

watermelons and rape. In the course of the

2000s some farmers diversified irrigated farming

by introducing new crops such as maize, cabbage,

green pepper, okra, and onions.

Those farmers engaged in small-scale irrigated

farming often grow just one or two crops, and thus

susceptible to damage by floods, insects and pests,

and price fluctuations. Vegetable farming is quite

input intensive and requires substantial amounts

of agrochemicals such as insecticides, fungicides

and pesticides. Thus, after deducting the cost of

inputs, it is not as profitable as it appears from

sales.

6. Differential Vulnerability of Farmers

According to Strata

How resistant or vulnerable a farm is to exter-

nal shocks varies from one farmer to another, and

village farmers can be broadly grouped into three

strata according to their vulnerability or resil-

ience.

6.1 Most vulnerable stratum of farmers

The most vulnerable stratum of farmers was

found in those households who were reliant on

rainfed farming and who were with limited

resources such as land or labor, which resulted in

low and unstable production of maize. Since few

of this type own cattle and a plough, they tend to

be late in planting maize. Their rainfed maize

production was volatile due to several factors

including weather changes and shortages of labor

and land, and in many years deficits were recorded

in maize balance sheets.

Some of these farmers depended on remit-

tances of relatives living in urban areas. The rel-

atives in urban areas buy mealie-meal (ground

maize) for farmers to supplement the farm’s

maize production and to buy fertilizers and seeds.

6.2 Lower stratum of those households

combining rainfed maize in the

uplands with irrigated farming in

dambo

Although this type of farmers combined two

types of farming, the potential gain of the combi-

nation was not realized because their rainfed

maize production was small scale and unstable,

and/or their dambo farming was small scale and

not diversified, hence susceptible to loss by price

fluctuations or damage by crop disease.

6.3 Upper stratum of farmers combining

rainfed maize and dambo farming

A small minority of farmers combined larger

scale rainfed farming in the uplands with irrigated

farming using engine pumps. These well-off

farmers had cattle and could afford to buy

fertilizers. They could plough and plant on time

and apply fertilizers on their fields. Thus they

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

251

could run more stable farming with higher produc-

tivity for upland rainfed farming. With regard to

dambo irrigated land, their farming was more sta-

ble and large scale through the use of engine and

treadle pumps and improved canals. Since their

irrigated farming was more diversified in terms of

crops grown, it was more resistant to crop disease

and price fluctuations.

7. Conclusion

Food production using a Green Revolution type

of innovation was developed in Zambia by using

improved seed varieties of maize, the staple food,

and chemical fertilizers. This was spread among

small farmers by state support in marketing and

prices of produce and inputs. Lack of an irriga-

tion component undermined the stability of maize

production, while limited supply of agricultural

credit and shortages of resources to purchase

inputs on the part of small-scale farmers curtailed

diffusion of the improved seeds/chemical fertilizer

innovations. Input subsidies including FSP and

small-scale irrigation could break these con-

straints. In the case study village, the develop-

ment of dry-season irrigation farming in dambo,

and its combination with rainfed maize production,

contributed to increased income and improved

food security by providing income sources to buy

food or food production inputs as well as additional

food. This makes combined farming more resis-

tant to shocks and fluctuations. However, irriga-

tion farming has its own vulnerability such as

price fluctuations and damage by floods and crop

disease, and it requires resources to purchase

inputs and invest in pumps and plot development.

Although FSP contributed to increased maize pro-

duction through increases in fertilizer availability

and subsidies in its prices, only a minority of farm-

ers in the village had access to it. Only this

minority of relatively affluent farmers managed to

benefit from combining rainfed maize production

with improved inputs, some through subsidies,

and irrigation farming with diversified crops and

treadle and engine pumps.

(Accepted, 2014.12.18)

References

Benson, T. (2004) : Africa’s Food and Nutrition Security

Situation : Where Are We and How Did We Get Here?

Washington DC : Internat ional Food Pol icy

Research Institute.

Burke, W.J., Jayne, T.S. & Chapoto, A. (2010) : Factors

Contributing to Zambia’s 2010 Maize Harvest. Food Security Research Project, Policy Synthesis Paper

No. 42, September 2010.

Chambers, R. and Conway, G. (1992) : Sustainable rural

livelihoods : practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Brighton : IDS.

Cliggett, L., Colson, E., Hay, R., Scudder, T. & Unruh, J.

(2007) : Chronic Uncertainty and Momentary

Opportunity : A half century of adaptation among

Zambia’s Gwembe Tonga. Human Ecology 35.

Daka, A.E. (2006) : Experiences with Micro Agricultural

Water Management Technologies : Zambia (Report

submitted to the International Water Management

Institute, Southern Africa Sub-regional Office).

http://sarpn.org.za/documents/d0002066/Zambia_

AWM_Report.pdf (accessed December 2008)

Dorosh, P.A., Dradri, S. & Haggblade, S. (2010) :

Regional trade and food security : recent evidence

from Zambia. In : Sarris, A. & Morrison, J. eds. Food Security in Africa. Cheltenham : FAO &

Edward Elgar.

Earth Trends (2003) : Water Resources and Freshwater

Ecosystems – Zambia. Washington : World

Resources Institute.

Ellis, F. (2000) : Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Devel-

oping Countries. Oxford : Oxford University

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

252

Press.

Ellis, F., Devereux, S. & White, P. (2009) : Social Protec-

tion in Africa. Cheltenham, UK & Northampton,

MA, USA : Edward Elgar.

Fabricius, C., Folke, C., Cundill, G. and Schultz, L.

(2007) : Powerless Spectators, Coping Actors, and

Adaptive Co-managers : A Synthesis of the Role of

Communities in Ecosystem Management. Ecology

and Society vol. 12, no. 1.

FFSSA (Forum for Food Security in Southern Africa)

(2004) : Achieving Food Security in Southern

Africa : Policy Issues and Options. FFSSA Syn-

thesis Paper, Forum for Food Security in Southern

Africa. http://www/odi/org/uk/food-security-forum

FFSSA n.d. : Zambia Food Security Issues Paper. Forum for Food Security in Southern Africa.

http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resource

s/70B81E34FDA0CBFCC1256D5E0047321D-odi-

zam-25jun.pdf

FSRP/ACF (Food Security Research Project/ Agricul-

tural Consultative Forum) and MACO/Policy and

Planning Department 2010 Analysis of the 2009/10

Maize Production Estimate from the Crop Forecast

Survey, Lusaka.

Gould, Jeremy (2010) : Left Behind : Rural Zambia in

the Third Republic. Lusaka : Lembani Trust.

Haller, T. & Merten, S. (2008) : We are Zambians – Don’t

Tell Us How to Fish! Institutional Change, Power

Relations and Conflicts in the Kafue Flats Fisheries

in Zambia. Human Ecology no. 36 : 699-715.

Hanzawa, K. (1995) : Agricultural Production and Eco-

nomic Activity in Chinena Village : Economical Sig-

nificance of Dambo Use. In : Shimada ed. (1995)

Agricultural Production.

IMF (2006) : Zambia : Selected Issues and Statistical

Appendix. IMF Country Report no.06/118.

IMF (2008) : Zambia : Statistical Appendix. IMF

Country Report no. 08/30. Kajoba, G.M. (1995) : Changing Perceptions on Agricul-

tural Land Tenure under Commercialization among

Small-scale Farmers : the Case of Chinena Village

in Chibombo District (Kabwe Rural), Central

Zambia. In : Shimada ed. (1995) Agricultural Pro-

duction.

Kajoba, G.M. (2007) : Vulnerability and Resilience of

Rural Society in Zambia : From the Viewpoint of

Land Tenure and Food Security. In : Vulnerability

and Resilience of Social-Ecological Systems : Annual

Project Report, Kyoto : RIHN.

Kodamaya, S. (1995) : Migration, Population Growth and

Ethnic Diversity of a Village in Central Zambia. Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies vol. 27, no. 2.

Kodamaya, S. (2009) : Recent Changes in Small-scale

Irrigation in Zambia : the Case of a Village in Chi-

bombo District. In : Vulnerability and Resilience of

Social-Ecological Systems, FR2 Project Report

Kyoto : RIHN.

Kodamaya, S. (2011) : Agricultural Policies and Food

Security of Smallholder Farmers in Zambia. Afri-

can Studies Monograph, Supplementary Issue No. 42.

Larmer, Miles, and Fraser, Alastair (2007) : Of Cabbages

and King Cobra : Populist Politics and Zambia’s

2006 Election. African Affairs vol. 106, no. 425 :

611-637.

Mason, N.M. & Jayne, T.S. (2009) : Staple Food Con-

sumption Patterns in Urban Zambia : Results from

the 2007/2008 Urban Consumption Survey. Food

Security Research Project. Available on-line at

http://aec.msu.edu/fs2/zambia/index.htm

McPherson, M.F. (2004) : The Role of Agriculture and

Mining in Sustaining Growth and Development in

Zambia. In : Hill, C.B. & McPherson, M.F. eds.

Promoting and Sustaining Economic Reform in

Zambia. Cambridge and London : Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Morris, M., Kelly, V.A., Kopicki, R.J. & Byerlee, D.

(2007) : Fertilizer Use in African Agriculture : Les-

sons Learned and Good Practice Guidelines. Wash-

ington DC : The World Bank.

Mungoma, C. & Mwambula, C. (1996) : Drought and

Low N in Zambia : The Problems and a Breeding

Strategy. In : Edmeades, G.O. et al. eds. Develop-

ing Drought- and Low N-Tolerant Maize : Procee d i-

n gs of a Symposium, March 25-29, 1996, CIMMYT,

El Batan, Mexico. CIMMYT (International Wheat

and Maize Research Center) and UNDP (United

Nations Development Program). Noyoo, Ndangwa (2008) : Social Policy and Human

Development in Zambia. Lusaka, Zambia : UNZA

Press, University of Zambia.

Shiro Kodamaya : Fertilizer and Irrigation in Improving Smallholder Food Security : The Case of One Village in Central Zambia

253

O’Brien K.L. & Leichenko, R.M. (2000) : Double

Exposure : assessing the impacts of climate change

within the context of economic globalization. Global

Environmental Change, no. 10 : 221-232.

Simatele, M.C.H. (2006) : Food Production in Zambia :

The Impact of selected structural adjustment

policies. AERC Research Paper 159, African Eco-

nomic Research Consortium, Nairobi, Kenya. Available on-line at http://www.aercafrica.org/docu-

ments/RP159.pdf

Shimada, S. ed. (1995) : Agricultural Production and

Environmental Change of Dambo. Sendai : Tohoku

University/ University of Zambia.

Shimada, S. (2007) : Gendai Africa Nouson (Rural Tran-

sition in Modern Africa : Challenge of Area Study to

Read Change) Tokyo : Kokon-Shoin. (in Japanese)

Thurlow, J. and Wobst, P. (2004) : The Road to Pro-Poor

Growth in Zambia : Past Lessons and Future

Challenges. In : Operationalising Pro-Poor

Growth : A Country Case Study on Zambia. A joint

initiative of AFD, BMZ, DFID, and the World Bank.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) 2006

Africa Environment Outlook 2 : Our Environment,

Our Wealth. Nairobi : UNEP.

UN Millennium Project (2005) : Halving Hunger : It

Can Be Done. Task Force on Hunger. UNDP

(United Nations Development Program) London :

Earthscan.

World Bank (2010) : Zambia : Impact Assessment of the

Fertilizer Support Program : Analysis of Effectiveness

and Efficiency. Report No. 54864-ZM World Bank,

Africa Region. Available on-line at http://wds.

worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/

WDSP/IB/2010/07/16

ZACF (Zambia Agricultural Consultative Forum)

(2009) : Report on Proposed Reform for the Zam-

bian Fertilizer Support Programme. Available

online at www.aec.msu.edu/fs2/zambia/FSP_

Review_Report_feb_09.pdf

Zambia (2002a) : Ministry of Finance and National Plan-

ning, Zambia Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper 2002-

2004. Lusaka.

Zambia (2002b) : “Agriculture-centered Development :

The New Deal Vision in Agriculture”. Lusaka :

State House Press and Public Relations Unit.

Zambia (2004) : Ministry of Agriculture and Co-opera-

tives, National Agricultural Policy 2004-2015. Lusaka.

Zambia (2005) : Ministry of Agriculture and Co-opera-

tives, National Irrigation Plan (NIP). Lusaka.

Zambia (2006) : Fifth National Development Plan 2006-

2010. Lusaka.

季刊地理学 66-4(2015)

254

小規模農民の食料安全保障を改善する肥料と灌漑農業

── ザンビア中央州の 1農村の事例から ──

児玉谷 史 朗*

本稿では化学肥料の使用と灌漑がアフリカの小規模農民の食料安全保障に与える効果についてザンビア中央部の一つの村を事例として検討した。事例村では,近年注目されている湿地帯を利用した小規模灌漑が広く行われている。本稿では小規模農民世帯の食料安全保障には,自家消費用の食料作物の生産だけでなく,それ以外の農業活動や非農業活動が食料確保の原資を提供する形で貢献し得る点に注目した。調査の結果,トウモロコシの生産は気象条件(旱魃等)と化学肥料の入手状況に影響されること,

灌漑による乾季のトウモロコシ作は限定的であり,むしろ灌漑による野菜生産,小規模ビジネス,親類からの送金が重要な役割を果たしていることが明らかとなった。これらによる現金収入が化学肥料等の購入または食料の購入に使われ,食料安全保障が改善した。

キーワード : 灌漑農業,「緑の革命」,ザンビア,脆弱性,小規模農民

*一橋大学