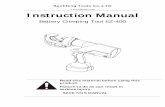

Feminist power tool instruction manual

-

Upload

architecturephilosophy -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Feminist power tool instruction manual

FEMINIST POWER TOOL INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Architecture + Gender Elective studio at KTH , year 4-5

Autumn 2013Sofia Wollert-Olsson

2

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

POWER TOOL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

FEMINIST MANIFESTOS

ALTERING PRACTICES

BODY-BUILDING

ARCHI-TECHNO-GIRLS

ÉCRITURE FEMININE

MATERIALIST ETHICS

123456

5

7

9

11

13

15

17

4

Examples:

• Writing a manifesto.

A manifesto is a written statement that describes the policies, goals, and opinions of a person or group. (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/manifesto)

In the essay “Women’s environmental rights: a manifesto” the writer Leslie Kanes Weisman points out that for a very long time our culture have associated different gender with different chores. For example a woman takes care of the children and the house and the man goes to work and is the bread provider. These chores have demanded different kinds of space. In time characteristics of the space and the gender have been intertwined. Result-ing in stereotypes and cultural word association. What we need to understand today is that these links between gender, occupation and space has changed. But still the stereotypes are left behind.

Leslie Kanes Weisman writes: “It is the responsibility of architectural feminism to heal this schizophrenic spatial schism- to find a new architectural language in which the “words”, “grammar” and “syntax” synthesize work and play, intellect and feeling , action and compassion. “(Kanes Weisman, 2000 : 2)

These deeply incorporated stereotypes prevent us from creating space that collab-orates with its users. The gender roles that initially was strongly linked to the City is now locked by these old approaches and not developing fast enough. Much have happened but yet much remains and especially in when it comes to mothers in the public room.

“Women must demand public buildings and spaces, transportation and housing which support our lifstyles and income and respond to the realities of our lives , not the cultural fantasies about them. “ (Kanes Weisman, 2000 : 3)

“The kind of spaces we have, don’t have , or are denied access to can empower us or render us powerless /…/ We must demand the right to architectural setting which will support the essential need of all women. (Kanes Weisman, 2000 : 4)

I agree with a lot that Weisman says even though I feel that we have come much further than she implies. I think that we do what we know till we know better. Therefore I think it is vital to give the experience of for example handicapped peo-ple to architects by letting them go around in a wheelchair for a day.

5

FEMINIST MANIFESTOSPOWER TOOL 1

6

Examples:

• Recognizing practices that doesn’t work desirably.

• Suggest ways of altering these practices for a more desirable output.

• Alter them

In the text “Feminist Practices Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architec-ture “ Lori A. Brown writes about noticing that there were far fewer women and minorities in positions of power in her profession as an architect. She notices some-thing that feels wrong and looks for ways to alter that. How could we improve och just change a behavoir or practice.

There are many things in our society that function in a certain way because “it has always worked like that”, or just because no one was there to make sure it was corrected from the beginning. Sometimes things just stay as they are because hab-its are considered so hard to change. But small interventions could create big improvements.

Lori A. Brown divides the feminist practices into four cathegories; design, pedago-gy, design research and communities.

7

ALTERING PRACTICESPOWER TOOL 2

8

Examples:

• Challenging and raising important questiones about the role and representation of women in society.

• Exploring the relation between the body and the public and private space in terms of property, propriety and the proper. What are we shielding or protecting and from whom?

In resembling the female body with a shirt Elisabeth Diller challenge our thinking in the essay “Bad Press”.

The thought that to be socially adequate in the public sphere it is important to iron your shirt in the same way as everyone else. Having a properly ironed and clean shirt gives us social codes that we use to scan our surroundings and feel integrated. When the shirt has been washed it is wrinkled, even when it dries it is wrinkled. Cloth is wrinkly in its natural state. But we have changed our expectations on what a shirt should look like and therefore we spend countless hours on ironing it into a form that is socially viable with the argument, that is how it should look.

Likewise, the female body is altered from its natural state, while the male body has remained the same, only changing clothes. Corsettes, Bras, Plastic surgery, Push-ups, Make-up, Hair-extentions, Lip-fillers, Retushing, all of them changing the view of what the female body looks like in its natural state. Unlike an ironed shirt that has always been ironed in a certain way, the female body as a fashion element has changed often with the fashion trends.

Elisabeth Diller gives us pictures and manuals of alternative ways of ironing shirts, broadening our perception of what a shirt should look like. But wouldn’t it be best if we just stopped ironing all together. It is a task like Sisyfos’s.

The female body has been shielded and contained to protect society from its sex-uality. But in shielding and containing said to protect itself from the sex drive of men. In both cases the alteration lies with the female .

9

BODY-BUILDINGPOWER TOOL 3

10

Examples:

• Strengthen the female perspective in the technical design pro-cess

• Design and invent technique designated for women at the same degree as we design for men.

• Reload technical terms/terms in general associated with the feminine with more power and force.

• Rethinking or relabeling technical tool-utencils as potentional-ly feminine, instead of writing them all of as masculine. With-out labeling them good or bad.

In the text “Container Technologies” Sofia Zoe encourage women to become more visible on the technical field. Men are often considered to be “more tech-nical” . For a very long time most of the technical tools, machines etc have been designed for men since they have been the users. Today there is a shift. Women could be considered to be as interested in technique as men when it comes to tech-nique that deals with subjects that interest them . Since we havn’t been integrated in the design of technique as long as men, there are still areas of interest for us to suggest.

Since this has been an area mainly dominated by men for a very long time their in-terests have also dominated the resource and words associated with technique has been associated with men. Sofia Zoe gives an example of a female associated word that she says we have to strengthen “container” refering to the female womb. However I do not agree that container is a female word when it could just as well be something as general as a stomach.

Today we lable most of our technique with a gendreless “it” and we can see the advantages of designing in a way that appeals to all sexes. Sofia Zoe gives an example of male driven design in the “smart house”, a house with lots of gadgets appreciated by men in relation to the GaBe house designed by a women focusing on being a self-cleaning house. This example is good but today very stereotype.

11

ARCHI-TECHNO-GIRLSPOWER TOOL 4

12

Examples:

• Writing and describing experiences and thoughts.

Who has the right to write? Who has the right to take up space on a paper, in a book, in a magazine , on a wall and manifest their thoughts to the world?

In a democracy we say “everyone”. We learn that it is vital for our political system to work, for our society to work.

So she wrote.

Why did you write that? Do you really think that way? What do you think others think about what you wrote?

In a society we can say what we want but we will also be evaluated and judged after what we say.

So she hesitated in writing.

Hélène Cixous writes in her text ‘Coming to Writing’ about all she wants to write about but hesitate writing. She struggles with the feeling of not feeling entitled to speak up and share her voice with the world. At the same time it is clear that she has so much to tell. Her language is rich and passionate. The words are loaded and ful of allegories.

I think writing is a very powerful tool but we have to be clear about what is in the toolbox. Words are powerful and could give different associations and meaning in different surroundings. This could create misunderstandings. To be sure our inten-tion come accross we should know our reader and also be clear about what we want to say.

This could make us hesitate in writing. The fear of being misunderstood or being confronted when we’re not 100% sure what we want to say could be paralyzing. I have many times heard the distinction that girls are afraid of confrontation while boys like search for it. This leading to boys speaking straight out without thought or fear of being questioned and girls hesitating.

13

ÉCRITURE FEMININEPOWER TOOL 5

14

Examples:

• Reading philosophy and theory and using it for design ideas in architecture.

• Using philosophy and theory as a critical framework for prac-tice.

In the book “Irigaray for Architects” Peg Rawes describes the work of Luce Iriga-ray. Irigaray is interesting for architects since “she examines how gender and sub-jectivity construct our experiences of Western culture and architecture”(Rawes, 2007 : 2)

Irigaray has a theory of sensing subjects and spaces that explores the importance of sense-based interaction with architectural design. Irigaray claims that “touch is the new way of expression for describing the sexed subject’s interactions with oth-er people, and understandings of materials and space.” (Rawes, 2007 : 51)“Sensory experiences of the world, space and architecture are generated our of tactile and non-verbal relations” (Rawes, 2007 : 53)

Sensory and tactile experiences are aspecially important when designing for the blind. We all rely on our eyes perhaps too much. Instead of touching we might imagine the feel of touching a surface just by looking at it.

At the end of the text by Peg Rawes she presents a few questiones for dialogue and we can clearly see how these questiones might help in a design process. Stimu-lating new ways of looking at things.

“How do intimate spaces enable productive social relationships?Why are non-visual perceptions of space important for architects?What value do multi-sensory methods have for making architectural space benefit the user? What can touch-based sensory perceptions offer to contemporary design?What is required in design to make urban spaces places of constructive encounters?What are the important considerations for designing spaces for women and(or tac-tile interaction, e.g. hospitals and maternity wards?” (Rawes, 2007 : 61)

15

MATERIALIST ETHICSPOWER TOOL 6

16

17

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1

2

3

4

5

6

Leslie Kanes Weisman, ‘Women’s Environmental Rights: A Mani-festo’ in Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, Iain Borden, eds, Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, London: Routledge, 2000, pp. 1-5.

Lori Brown, ‘Introduction’ Lori Brown, ed., Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture, London: Ashgate, 2011.

Elizabeth Diller, ‘Bad Press’ in Francesca Hughes, ed. The Architect Reconstructing her Practice, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996, pp. 74-95.

Zoe Sofia, ‘Container Technologies’ in Hypatia Vol. 15, No. 2, Spring 2000, pp. 181-200.

Hélène Cixous, ‘Coming to Writing’ in Hélène Cixous, Coming to Writing and Other Essays, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Peg Rawes, ‘Introduction’; ‘Touching and Sensing’ in Peg Rawes, Irigaray for Architects, London: Routledge, 2007.

![DXM Configuration Tool Instruction Manual [ 158447 ]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/589d7f031a28abc24a8ba31e/dxm-configuration-tool-instruction-manual-158447-.jpg)