Featured Aircraft - War Eagles Air Museum

Transcript of Featured Aircraft - War Eagles Air Museum

1 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

From the Director

W e’ll always be primarily an

aviation museum. However,

we’re starting to emphasize

our automobile collection more. Thanks

to the knowledge and hard work of Carl

Wright, our 1954 MG-TF, 1960 Nash

Rambler, 1935 Auburn Boattail Speed-

ster, 1929 Ford Model A, 1970 Jaguar E-

Type and 1956 Cadillac are now running.

We were proud to show them off at our

recent car show. We’ll bring more of our

cars “up to speed,” and we’re looking for

volunteers to take them for spins around

the ramp. Also, we’re re-starting our old

Crew Chief program for the aircraft and

cars. Volunteer Crew Chiefs will help us

maintain the appearance and functionali-

ty of our collection. If you’re interested,

let anyone at the Museum know.

The Museum has always been hard

to find, but three new hangars and a haz-

ardous material facility recently erected

around us now almost completely hide us

from the airport entrance road. To help

visitors find us, we installed prominent

new signs on the hangar. Also, age final-

ly caught up with our 25-year-old plumb-

ing, and we’re replacing much of it. “An-

dy the Plumber” has become a familiar

figure around these parts. These upgrades

have cost nearly $5,000. We tell you this

to inform you about what’s going on, and

to let you know that we’re seeking spon-

sors for projects like this. If you’d like to

help us accomplish some of the exciting

things we have planned, please call me.

Bob Dockendorf

Inside This Issue From the Director ....................... 1

Featured Aircraft ........................ 1

Editorial ...................................... 2

The Aviation Media Shelf ........... 6

Membership Application ............. 7

Tom Lea’s Aviation Artwork ....... 7

Car Clubs Meet at Museum ....... 8

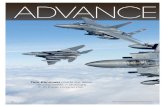

The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum

Third Quarter (Jul - Sep) 2012

Volume 25, Number 3

Featured Aircraft (Continued on Page 2)

Featured Aircraft

A lmost everyone has heard of the

Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey. The

infamous $60-million vertical-

takeoff-and-landing (VTOL) tilt-rotor re-

cently entered service with the U.S. Mar-

ine Corps and Air Force after 26 years of

development. What most people don’t

know is that the U.S. had a VTOL trans-

port that could carry as many troops and

nearly as much cargo as the Osprey, at

higher speed, for longer range and at less

cost—and that this airplane could have

been in service almost 50 years ago!

Almost 50 years ago, the Vought-Hiller-

Ryan XC-142A vertical-takeoff-and-landing

tilt-wing transport proved the military value

of VTOL technology. Today, Bell-Boeing’s

V-22 Osprey cannot match the performance

the XC-142A demonstrated so long ago.

2 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

Editorial I

f you’ve been reading Plane Talk for

a while, you’re going to notice some

changes in future issues. Over the

last 10 years or so, War Eagles Air Mu-

seum’s quarterly membership publication

has morphed from a fairly chatty “news-

paper” filled with information about local

events, Museum volunteer and staff pro-

files, new exhibits, reports on ongoing

projects, aviation humor, and so on, into

a strictly aviation- and military history-

oriented publication. In many previous

issues, the “Featured Aircraft” article and

Robert Haynes’ “Historical Perspectives”

column took up virtually all of the space,

leaving little room for current news items

and upcoming Museum-related events.

That’s about to change, as we dial back

the aviation technology and history con-

tent of Plane Talk in favor of more cov-

erage of what’s going on at the Museum.

This is all part of our new strategy to

increase the Museum’s physical and on-

line presence and, hopefully, to boost the

number of people who visit us. We plan

to host many more events, such as “mov-

ie nights” and car shows, and we’ll parti-

cipate in more activities, in partnership

with other local museums, clubs and org-

anizations, which we hope will make us

better known to potential visitors. Our

Facebook page is one way we’re dissemi-

nating current, up-to-date information on

what’s happening at the Museum. While

it won’t have the same immediacy, since

we’ll continue to publish it every three

months, Plane Talk will be another.

Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum Third Quarter 2012

Plane Talk Published quarterly by:

War Eagles Air Museum

8012 Airport Road

Santa Teresa, New Mexico 88008

(575) 589-2000

Author/Executive Editor: Terry Sunday

Senior Associate Editor: Frank Harrison

Associate Editor: Kathy Sunday

and turboprops did not exist at the time.

The companies usually built only one of

each, which limited flight test time. Thus,

these aircraft could not provide any indi-

cation of VTOL’s operational suitability

in the “real world.” Nor could they ad-

dress the military utility of VTOL, since

they did not have the equipment or capa-

bilities needed to perform realistic mili-

tary missions. Such operational suitabili-

ty testing was the focus of the next round

of VTOL aircraft, one of which is this is-

sue’s Featured Aircraft—the XC-142A.

In early 1959, the Department of De-

fense (DoD) formed a committee to eval-

uate the state-of-the-art of VTOL aircraft

technology, and to look at how the mili-

tary services could use VTOL aircraft.

The committee concluded that the servi-

ces could use VTOL aircraft, and that the

Air Force, Army and Navy requirements

matched best in the light transport area.

The committee recommended a VTOL

transport program be set up. The services

formed a group to examine the needs of

each and come up with joint operational

requirements that satisfied all three. The-

oretically, an aircraft designed to meet

the requirements would support military

utility evaluations while having useful

transport capabilities, the idea being that

From 1945 to 1960, the U.S. military

services spent more than $142.5 million

on more than 50 VTOL research aircraft.

These were basically testbeds to demon-

strate feasibility. No operational require-

ments for VTOL aircraft existed at the

time, so none was ever slated for produc-

tion. Their major contribution was the in-

vestigation of virtually every conceivable

vertical lift concept. These aircraft have

faded into obscurity, but a quick survey

of them reveals the variety of methods

they used to achieve VTOL flight.

For example, the Navy’s turboprop

Convair XFY-1 and Lockheed XFV-1

Pogo tail-sitters first flew in the 1950s.

McDonnell’s XV-1 Convertiplane was

an Army/Air Force compound helicopter

with a jet-powered rotor and fixed wings.

Bell’s Army-sponsored XV-3 tilt-rotor,

which first flew in 1955, was very similar

to the Osprey, with articulated rotors in

tilting pods on the wingtips. Bell’s X-14,

built for the Air Force, used thrust divert-

ers behind two horizontally mounted tur-

bojets to direct the jet exhaust downward

for vertical lift. Using company funds,

Bell also built the diminutive ATV (Air

Test Vehicle), cobbled together from off-

the-shelf parts of other aircraft, that fea-

tured two swiveling jet engines for verti-

cal and horizontal thrust. By 1958, Ryan

had tested the deflected-slipstream Army/

Navy VZ-3RY Vertiplane and the Air

Force X-13 Vertijet, a tail-sitter similar to

the Pogo but with a turbojet engine. Boe-

ing-Vertol used a tilting wing on its twin-

propeller Army/Navy VZ-2, which first

flew in 1958. Finally, Hiller’s Air-Force-

funded X-18, the largest VTOL aircraft

of its time, used two turboprop engines

(salvaged from the Pogo program) on a

tilting wing. It first flew late in 1959.

These aircraft showed there was no

“best” VTOL approach. All the designs

more-or-less worked, and they all provid-

ed valuable performance data, especially

on stability and control during transition

between vertical and horizontal flight.

But they all had several shortcomings.

Most used existing parts where possible,

so they were not optimized for VTOL.

High-performance, lightweight turbojets

Featured Aircraft (Continued from page 1)

The Hiller X-18 accumulated many hours

of flight test data that provided much of the

technical foundation for the XC-142A.

3 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

contractor should build it. The Navy de-

manded a tilting ducted prop design. The

Army wanted a tilt-wing. The Air Force

flip-flopped. When the Air Force and Ar-

my finally agreed, the Navy representa-

tive walked out in a huff.

Despite the internecine friction, the

Military Selection Board recommended

procurement of the Vought-Hiller-Ryan

VHR-447, a four-engine tilt-wing design.

Program management responsibility went

from BuWeps to the Tri-Service VTOL

Systems Program Office (SPO), at Aero-

nautical Systems Division, Wright-Pat-

terson Air Force Base, Ohio. Seeing itself

possibly shut out of the proceedings, the

Navy reluctantly agreed to join the pro-

gram, but never really got on board.

On January 5, 1962, DoD awarded

the Vought Aeronautics Division of the

LTV Aerospace Corporation a contract to

deliver five XC-142A VTOL transports.

The program seemed to be getting off the

ground. But the DoD’s goal of buying an

aircraft suitable for all three services re-

mained unmet. Inter-service rivalries and

roles-and-missions disputes raged at the

time; none of the services was about to

put up with real or imagined infringe-

ments by the others. Thus the Air Force

continued to fund Curtiss-Wright to fin-

ish its X-19 tilt-prop, the Navy pursued

Bell’s ducted-prop X-22A, and the Army

proceeded with Lockheed’s augmented-

jet-ejector XV-4A Hummingbird and Ry-

an’s fan-in-wing XV-5A Vertifan. The

Army’s projects were just small technol-

ogy demonstrators—the X-19 and X-22A

were thinly disguised, small-scale VTOL

transports, each built solely for its own

military sponsor. The Air Force and Na-

vy gave lip service to “Tri-Service,” and

each contributed money to the XC-142A,

but each also funded its own aircraft at

the same time. The idea of saving taxpay-

er money by cooperating on a joint proj-

ect fell victim to selfish parochialism.

Vought managed the other contract-

ors and built the main fuselage, wing and

landing gear. The remaining work went

to Hiller and Ryan in amounts proporti-

onal to their contributions to the propo-

sal. Hiller built the complex power trans-

mission system (drawing on its X-18 ex-

perience), the tail propeller, the ailerons

the services would buy a few aircraft,

assess their operational suitability in field

trials, and then, if the tests were success-

ful, move it right into production. By Oc-

tober 1960, the group had finalized the

preliminary requirements for what soon

became the Tri-Service VTOL transport.

The Air Force, Army and Navy each

contributed $1 million (paltry by today’s

standards) to start the program, under the

overall management of the Navy Bureau

of Weapons (BuWeps). BuWeps imme-

diately ran into problems writing the Re-

quest for Proposal (RFP), because it had

no flying qualities requirements for such

an aircraft. DoD had separate fixed-wing

aircraft and helicopter specifications, but

none for a flying machine that could be

both. BuWeps finally hedged, referenced

both specs and distributed the RFP to in-

dustry on February 1, 1961, with a two-

month turnaround time. The RFP called

for construction of five test aircraft, with

no guarantee of production (although Bu-

Weps tacitly dangled the carrot of a big

production contract before the bidders).

The RFP’s requirements were so

tough that even experienced aircraft com-

panies found them hard to meet, but 15

firms rose to the challenge—Douglas,

Boeing-Vertol, Boeing-Wichita, Bell, Si-

korsky, North American, and teams of

Bell-Lockheed, Grumman-Kaman, Mc-

Donnell-Canadair and Vought-Hiller-Ry-

an. DoD had hoped to select a contractor

quickly, but inter-service squabbles de-

layed the decision. The services fought

over the type of aircraft to buy and which

Third Quarter 2012 Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum

and flaps. Ryan took care of the aft fuse-

lage, tail assembly and nacelles.

The XC-142A was the world’s big-

gest VTOL aircraft until Dornier’s all-jet

Do.31E3 flew in Germany in July 1967.

It could carry 32 troops, 24 litter patients

or 8,000 pounds of cargo. Its cabin was

the same size as a Boeing-Vertol CH-1B

Chinook helicopter’s, with a similar inte-

gral cargo door and loading ramp. The

hydraulically actuated wing tilted from

zero to 100 degrees relative to the fuse-

lage, its slight backward tilt allowing the

XC-142A to hover in a 20-knot tailwind.

It had full-span slats and flaps, with the

outer flap segments acting as ailerons. A

horizontal tail propeller controlled pitch

during hovering and transition flight.

Power came from four 2,850-horse-

power General Electric T64-GE-1 turbo-

prop engines. Cross-shafts, clutches and

gearboxes connected the engines togeth-

er, so if an engine failed, all four 15.5-

foot-diameter Hamilton Standard propel-

lers kept turning1. Another shaft drove

the tail propeller. Imagine the complexity

of this “mechanical nightmare”—and it

was all mechanical, not computerized.

Remember, this was back when NASA’s

Featured Aircraft (Continued on page 4)

Vought/Hiller/Ryan XC-142A General Characteristics

Powerplants

Four (4) 2,850-horse-power General Electric T64-GE-1 turboprops

Maximum speed 479 miles per hour

Service Ceiling 25,000 feet

Length 58 feet 1½ inches

Wingspan 67 feet 6 inches

Ferry Range 3,800 miles

Weight (empty) 23,045 pounds

Weight (VTOL) 37,474 pounds

1 In cruising flight, the pilot could shut down the two outboard engines to save fuel, while the cross-

shafts drove all four propellers.

4 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum Third Quarter 2012

lines’ ardor, and a civil version was never

more than a tantalizing pipe dream.

The XC-142A program was complex

and convoluted. Here’s a short summary

of what happened...

No. 1 first flew on March 26, 1965

(it was the third to fly). In May 1966, it

left Dallas for Cat II testing at Edwards

Air Force Base, California. During the

ferry flight, it refueled in El Paso, where,

in a crowd-pleasing display, it hovered

for 10 minutes before landing.

On October 7, 1966, after becoming

the first XC-142A to notch 100 flights,

No. 1 flew nonstop from Edwards back

to Dallas. Air rescue testing with dum-

mies at nearby Mountain Creek Lake

soon began, culminating in the “rescue”

of Vought security guard John Narra-

more from a raft in the lake while pilot

John Omvig hovered No. 1 at 125 feet.

On its 149th flight, on May 10, 1967,

No. 1 crashed in heavily wooded marsh-

land near Mountain Creek Lake, killing

the contractor crew of Stuart Madison,

Charles Jester and John Omvig. The test

plan for the fatal flight involved a rapid

descent to simulate a profile that would

minimize exposure to ground gunfire. At

low altitude, the aircraft pitched over, hit

the ground and burned. Investigation re-

vealed that the tail propeller control sys-

tem had failed.

No. 2 was the first XC-142A to fly,

the first to hover and the first to transition

between vertical and horizontal flight. It

had its share of accidents. On March 21,

1965, while flying low-and-slow at the

Apollo spacecraft were about to fly to the

moon with less onboard computing pow-

er than in a modern digital watch.

The flight control system was even

more complicated. It was a clever mecha-

nical design—without computers. In hor-

izontal flight, the controls operated in the

usual way. In hovering, it was different—

the tail propeller controlled pitch, the

outboard flaps controlled yaw, and differ-

ential engine thrust handled roll. So far,

so good. The challenge was to make the

airplane behave during transitions be-

tween vertical and horizontal flight. The

key was a mechanical integrator that sent

the pilot’s stick and rudder inputs to the

appropriate flight controls as a function

of wing tilt. It was “transparent” (using

the term as it was originally intended),

requiring no extra pilot thoughts or ac-

tions. For example, during transitions,

roll control came from both the outboard

flaps and differential thrust in proportion

to the angle of the wing. Even when this

complex, sensitive mechanical control

system worked properly, the XC-142A

was still a handful for its pilot to fly2.

By early 1963, with the design well

in hand and fabrication underway, seri-

ous funding problems caused Vought to

slip the first flight date from March to

July 1964, because there was no money

to pay for overtime labor. On the positive

side, January 1964 saw the first wing-fu-

selage mating. By that June, XC-142As 1

and 2 were complete, and 3, 4 and 5 were

coming along nicely.

XC-142A No. 1 rolled out at the

Vought plant in Dallas on June 17, 1964,

and went through its paces under the blue

Texas sky, demonstrating a full 100-de-

gree wing tilt cycle. Flight testing started

immediately. The test plan had two pha-

ses—Category (Cat) I, contractor tests, to

prove airworthiness, and Cat II, military

tests, to evaluate operational suitability.

Featured Aircraft (Continued from page 3)

The No. 2 XC-142A was the first to

fly, on September 29, 1964, at the skilled

hands of Vought’s chief test pilot John

Konrad and senior test pilot Stuart Madi-

son. They took off conventionally, using

only 1,700 feet of runway, with the en-

gines at 60% power. On the 38-minute

hop, they climbed to 10,000 feet, hit 175

miles per hour and landed with a rollout

of just 1,000 feet. The Tri-Service Tilt-

wing’s maiden flight was a big success.

No. 2 flew Cat I tests at Dallas into

early 1965, when No. 3 joined it after its

first flight on December 11, 1964. No. 2

performed the program’s first hover on

December 29, 1964, and the first conver-

sion from vertical to horizontal flight and

back again on January 11, 1965. The test

card for this flight was simple: “(1) Lift

to hover, (2) Do it, (3) Undo it.” Madison

did it and undid it in No. 2 twice with no

problems. Later, he did it and undid it a

third time in No. 3. On that flight, the

landing gear would not extend. He set the

aircraft down on its belly so gently that

the only damage was bent radio antennas

and a few dents in the main gear pods.

Spurred by these successes, Vought

quickly demonstrated the aircraft to sev-

eral major US airlines, and started talking

to the FAA about approval of a civil ver-

sion. These demonstrations wowed the

airlines, who foresaw using VTOL air-

craft for short-haul, high-density routes,

such as from Boston Common to the Pan

Am Building in New York City. Issues of

costs, fares and the risks of operations in

metropolitan areas finally cooled the air-

2 If your eyes glaze over at this aeronautical en-gineering digression, just think of it this way: the

XC-142A successfully flew like both a convention-

al airplane and a helicopter solely under the control of the pilot and some rods, gears and levers. It was

an impressive accomplishment for its day.

In this pre-Photoshop paste-up photo-

montage, XC-142A number 3 takes off verti-

cally, starts forward and transitions to hori-

zontal flight, with the wing tilting through

about a 90-degree angle.

The No. 1 XC-142A transitions from ver-

tical to horizontal flight at Vought’s Dallas

facility. Note the angle of the all-moving tail,

the ramps that smoothed airflow around the

wing pivot and the deflected flaps.

5 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

factory, it oscillated sharply before hit-

ting the ground hard. None of the crew-

men were injured, but the wingtips, ailer-

ons and outboard engine tailpipes were

damaged. It turned out that the deflected

propwash produced erratic aerodynamic

disturbances and loss of directional con-

trol. Seven months later, a propeller went

into flat pitch right at touchdown, result-

ing in a hard landing and damage to the

landing gear and wing. Authorization for

repair was not forthcoming, since money

was very tight. But, after an accident

damaged the fuselage of No. 3 in January

1966, the Air Force told Vought to put

No. 3’s undamaged wing on No. 2.

On August 16, 1966, No. 2 joined 1,

4 and 5 at Edwards. The change of venue

didn’t end its jinx, however. On one of its

first flights, the pilot had to make an

emergency conventional landing, during

which the brakes caught fire. Then an

engine gearbox failed—on the ground,

fortunately—because of a weak support

shaft. Vought designed a fix and modi-

fied the gearboxes of all the aircraft.

No. 2 then had no problems for more

than a year. One of its most impressive

accomplishments during that time was a

three-ship test, with Nos. 4 and 5, called

a tactical field demonstration. Many mili-

tary and Government representatives wit-

nessed the highly successful test, which

showed conclusively that the XC-142A

excelled in performing realistic military

missions, such as assault landings, cargo

drops, transporting troops and more.

On October 9, 1967, while testing a

flight control system change, No. 2 land-

ed hard and sustained major damage, al-

though with no injuries to the crew. This

time there was no money to repair it. The

last flight of No. 2—the 488th of the pro-

gram—was the last of any XC-142A. It

seems fitting that the same aircraft that

made the first flight nearly three years

earlier also made the last.

The brief career of No. 3 began with

its first flight on December 11, 1964. It

was the first XC-142A to be flown by a

full military crew. On August 6, 1965, it

flew to Edwards by way of Tucson. On

January 3, 1966, having made only 14

flights, it suffered major fuselage damage

in a hard landing. After transplanting its

Third Quarter 2012 Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum

wing onto No. 2 and cannibalizing other

parts, the Air Force junked what was left.

If any XC-142A can be said to have

enjoyed a distinguished career, it would

have to be No. 4, which flew for nearly

two years with no major problems. It was

the only remaining flightworthy aircraft

at the end of the program and is the only

example of the breed in existence today.

No. 4 first flew on June 17, 1965.

Some of the things it accomplished in-

cluded VTOL operations on wet runways

and at night, off-runway operations, land-

ings on a rubberized membrane, use of

forward-area landing mats and dozens of

cargo and personnel pickups and drops.

By early 1967, an XC-142A trip to

the Paris Air Show, a long-time gleam in

Vought’s corporate eye, was in the off-

ing. No. 4 got the nod for the job, and

received a new, stunning red, white and

blue paint job with American flags and

bold “United States of America” letter-

ing. On April 26, the spruced-up machine

flew to Florida and landed on the carrier

USS Saratoga, which sailed for Europe

and arrived off Spain on May 10. A short

hop took it to the Navy base at Rota on

its way to Paris. Meanwhile, back in Dal-

las, No. 1 had just crashed, and the fleet

was grounded. When the grounding was

lifted on May 17, No. 4 was cleared for

conventional flight only. With a new tail

prop control system installed in Paris, it

was cleared for full vertical operations.

The biennial Paris Air Show was the

premier showcase for military and com-

mercial aircraft of manufacturers from all

over the world, and the 1967 show was a

huge success. No. 4 went through its pa-

ces in two exciting 12-minute demonstra-

tions. Meanwhile, Vought’s representa-

tives went all-out to rekindle airline inter-

est in a commercial version, even coming

up with the catchy name “Downtowner,”

but the XC-142A program ended soon af-

ter No. 4 returned to Dallas. Only one of

the several VTOL aircraft exhibited in

Paris had a bright future—the small Brit-

ish Hawker-Siddeley P.1127, which later

became justly famous as the Harrier.

No. 5 first flew on March 19, 1966,

and chalked up some significant accom-

plishments in its short but active career.

Its main claim to fame was its Navy ship-

board flights. In May, it made 50 short

and vertical takeoffs and landings on the

deck of the training aircraft carrier USS

Bennington cruising off San Diego. An

Army pilot with no experience in carrier

operations also flew some tests. No. 5

operated at sea again in November and

December 1966, flying from the USS Og-

den and the USS Yorktown. Sadly, on De-

cember 28 at Edwards, it slammed into a

hangar door while taxiing and banged up

the nose section, thus ending its career.

XC-142A No. 5 lands on the carrier USS

Bennington on May 18, 1966, with the wing

tilted up to an intermediate position.

Despite the accidents that wrecked

four of the five XC-142As, the test pro-

gram showed that a VTOL cargo aircraft

had real military utility. The problems it

experienced were the types common in

development programs. So why did the

XC-142A not go into production? The

reason is simple—money. At the time,

Vietnam was sapping America’s resour-

ces at the highest level since World War

II. President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered

the Defense Department to cut its budget.

The fiscal environment in Washington

simply could not support a major VTOL

production program. Also, some military

leaders still considered VTOL “not ready

for prime time.” Thus, the lofty goals of

the Tri-Service tilt-wing remained unmet,

and development of a later VTOL trans-

port started anew, resulting in the costly,

problem-plagued Bell-Boeing V-22 Os-

prey. The only remaining example of the

airplane that demonstrated it could do the

same job almost five decades ago—the

No. 4 XC-142A—is in the Museum of

the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, still

resplendent in its “Paris Paint.”

6 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum Third Quarter 2012

North American AT-6 Texan advanced

trainers, but most of the aerial scenes in-

volve PT-17 Stearman primary trainers.

Virtually all American World War II pi-

lots, whether ultimately assigned to fight-

ers, bombers or transports (and many for-

eign pilots also, as Thunder Birds accur-

ately depicts) had their first flying experi-

ences in these venerable blue-and-yellow

biplanes. Scenes of these graceful aircraft

soaring over the desert are stunning. And

they’re the real thing—there are no spe-

cial effects here. Other than a few close-

up shots of the pilots in the cockpits, the

aerial action really happens as shown.

In all, Thunder Birds is a feel-good

film made when the worst war in history

raged in Europe and Asia, and when Am-

erica seemed isolated, alone and not cer-

tain to prevail over the enemy. Viewers

at the time surely were inspired by its

scenes of tight formations of dozens of

aircraft and by its depictions of the fresh

young kids who signed up in droves to

answer their nations’ needs. The breadth

and depth of America’s wartime mobili-

zation is on full view in Thunder Birds,

and even today’s jaded, cynical viewers

can get a thrill seeing so many of these

historic aircraft in flight. With so few of

them flying today, it’s worth it for the

aviation buff to see this film just for these

scenes. Check it out if you’re interested

in classic aircraft, military flight training

or 1940s-vintage Hollywood stars.

Only the Wing by Russell Lee

M any students of World War II

German aviation technology

know about the pure “flying

wing” aircraft built by brothers Reimar

and Walter Horten. Their designs were

intended to reduce an aircraft to its most

fundamental element, a concept called, in

German, Nurflügel—‟only [the] wing.”

Horten aircraft mostly flew well without

such conventional appurtenances as a fu-

selage, horizontal and vertical stabilizers,

elevator and rudder.

Reimar Horten started building all-

wing aircraft as a teenager. Like many

young Germans in the 1930s, he had a

passion for gliders and sailplanes, which

were about the only types of aircraft the

Versailles Treaty permitted German man-

ufacturers to produce. Reimar believed

all-wing aircraft were far more efficient

than conventional designs, and would fly

better in the sailplane competitions that

were of great interest to him and Walter.

Unschooled in the principles of aircraft

design until much later in his life, young

Reimar nevertheless created remarkable

aircraft that flew well and had few vices.

His most famous design was the jet-pow-

ered H-IX, three prototypes of which the

Luftwaffe tested. It handily outperformed

Messerschmitt’s Me.262 jet fighter. The

“jet wing” was a brief departure from the

Horten brothers’ real love, sailplanes.

Russell Lee’s history of the Horten

brothers and the aircraft they built in Hit-

ler’s Germany and, later, in Argentina

(more than 65 aircraft of 27 different de-

signs) is comprehensive and highly read-

able. It also covers in detail a big aerody-

namic problem of tailless aircraft—“ad-

verse yaw,” which is the tendency of an

aircraft to turn, or “yaw,” in the opposite

direction than the pilot intends when she

or he moves the control stick to turn. All

aircraft have adverse yaw, but, in con-

ventional designs, pilots correct for it by

using the rudder. All-wing aircraft have

no rudder, so other techniques are need-

ed, including drag flaps, Friese ailerons

and differential aileron gearing. If you’re

interested in such engineering minutia,

Only the Wing should be just your cup of

tea, and would make a great addition to

the bookshelf of any aviation enthusiast,

especially those interested in esoteric as-

pects of the field.

Thunder Birds (DVD)

T hunder Birds would never win an

Academy Award. This short (78-

minute) 1942 film, released just a

few months after the Pearl Harbor attack

plunged America into war, is simply a

decent piece of propaganda that may

have inspired young viewers to join the

U.S. Army Air Corps. Director William

Wellman filmed Thunder Birds at a real

USAAC flight training base in Arizona,

and the harsh desert scenery is awesome

in Technicolor. Preston Foster stars as

Steve Britt, a hard-as-nails civilian flight

instructor with a heart of gold. John Sut-

ton gives a low-key performance as Roy-

al Air Force student pilot Peter Stack-

house, whose fear of flying threatens to

wash him out of the program. The lovely

Gene Tierney is Kay, the woman they

both love. You can imagine the romantic

triangle that ensues…

As with many films of this type, a lot

of peripheral activities surround the flight

sequences. Talking, horseback riding,

barn-dancing and barbecue eating take up

at least half of the film. But the aerial ac-

tion makes up for its brevity with great

quality. There are a few shots of Vultee

BT-13 Valiant basic trainers (known dis-

paragingly as the “Vultee Vibrator”) and

Editor’s Note: We are unable to pub-

lish Robert Haynes’ “Historical Per-

spectives” column in this issue. In-

stead, we hope you enjoy these media

reviews that should be of interest to

many aviation enthusiasts.

The Aviation Media Shelf

Movies at the Museum

D o you enjoy classic aviation

movies? Have you lost track

of how many times you’ve

seen Twelve O'clock High? This Fall,

when it’s cool and dark in the early

evening, join us at the Museum for

our new monthly aviation film series.

We won’t reveal the titles now, but

you’re sure to enjoy them, plus some

extra special features. Call or check

our Facebook page for details.

7 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

Third Quarter 2012 Plane Talk—The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum

Membership Application War Eagles Air Museum

War Eagles Air Museum memberships are tax-deductible to the extent provided by law, and include the following privileges:

Free admission to the Museum and all exhibits.

Free admission to all special events.

10% general admission discounts for all guests of Member.

10% discount on all Member purchases in the Gift Shop.

To become a Member of the War Eagles Air Museum, please fill in the information requested below and note the category of mem-

bership you desire. Mail this form, along with a check payable to “War Eagles Air Museum” for the annual fee shown, to:

War Eagles Air Museum

8012 Airport Road

Santa Teresa, NM 88008

NAME (Please print) ____________________________________________ ADDRESS ___________________________________________________ CITY _________________________ STATE _____ ZIP _____________ TELEPHONE (Optional) _________________________ E-MAIL ADDRESS (Optional) _____________________________________ Will be kept private and used only for War Eagles Air Museum mailings.

Membership Categories

Individual $15

Family $25

Participating $100

Supporting $500

Benefactor $1,000

Life $5,000

Dobie’s books Apache Gold and Yaqui

Silver and The Longhorns. In 1940, Tom

won a Rosenwald Fellowship that would

have provided him with a year of free-

dom to paint whatever he wanted, but he

turned it down after the Editor of Life in-

vited him to join the magazine’s staff as

an Accredited War Artist-Correspondent.

During World War II, Tom traveled over

100,000 miles as an eyewitness reporter

for Life. He went to many of the places

where American forces fought, including

the North Atlantic, the South Pacific and

China. Life published his first-person ar-

ticles and paintings between 1942 and

1945. He documented his experiences of

landing on Peleliu with the 7th Marines in

his 1945 book Peleliu Landing.

Tom Lea died on January 29, 2001.

His legacy includes hundreds of paint-

ings, sketches and literary works that re-

flect his fascination with the Southwest

and his involvement in chronicling the

greatest conflict of the 20th century.

Join us at War Eagles Air Museum

on October 14, 2012, for a special pro-

gram about Tom Lea’s aviation artwork,

presented by retired Marine Corps avia-

tor “Mac” Greeley, Jr. Then take a guid-

ed tour to see the actual types of aircraft

he painted, and learn about the thrill of

flying the Curtiss Warhawk from Eric

Mingledorff, former owner and restorer

of our P-40E. Call the Museum or check

our Facebook page for more details.

Tom Lea’s Aviation Artwork

T om Lea III was born in El Paso,

Texas, on July 11, 1907. He at-

tended the Art Institute of Chica-

go from 1924 until 1926. After graduat-

ing, he worked as a muralist and com-

mercial artist until 1933, when he moved

from Chicago to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In Santa Fe, while working for the

Works Progress Administration, he did

illustrations for Santa Fe Magazine. Back

in El Paso in 1936, Tom became a well-

known muralist, and soon won commis-

sions to paint murals across the U.S., in-

cluding at the Benjamin Franklin Post

Office in Washington, D.C., the Federal

Courthouse in El Paso, the Burlington

Railroad Station in Lacrosse, Wisconsin,

and Post Offices in Pleasant Hill, Mis-

souri, and Odessa and Seymour, Texas.

In El Paso, Tom met book designer

Carl Hertzog and noted Texas writer J.

Frank Dobie. These friendships spawned

many collaborative projects, including

Detail from “Fighter in the Sky,” by Tom

Lea, oil on canvas, , 14¼” x 23¼”, January

1960. Image used by permission of the Tom

Lea Institute, El Paso, Texas.

8 www.war-eagles-air-museum.com

War Eagles Air Museum

Doña Ana County Airport at Santa Teresa 8012 Airport Road Santa Teresa, New Mexico 88008 (575) 589-2000

Car Club Show Draws a Big Crowd by Bob Dockendorf

W hat an incredible asset is the

War Eagles Air Museum! A

lot of great history is present

here, and it’s not just the airplanes. Auto-

mobiles are a big part of our collection

also. As a simple matter of demograph-

ics, far more people have a passion for

automobiles than have the knowledge, in-

terest and enthusiasm for aviation. It’s

fascinating to see, though, that, once car

enthusiasts are introduced to the excite-

ment of aviation, most of them develop a

greater interest in aircraft. In the past, I

think it would be fair to say that our clas-

sic and historic vehicles were true muse-

um pieces—they were well cared for cos-

metically, but many were not in running

condition. But that’s where the fun is—

getting behind the wheel, hearing the en-

gine and remembering the sights, sounds

participated. All of the attendees enjoyed

the cars, the wonderful, balmy afternoon

and each other’s company.

Thanks to meteorologist “Doppler

Dave” and our friends at KVIA-TV, the

event was well-advertised. A live-remote

weather broadcast brought lots of traffic

to the museum, and we had the best day

ever in our gift shop and admissions.

and smells of automobiles in their glory

days. On April 15, we hosted a car dis-

play involving several local car clubs,

which joined forces to meet at the Muse-

um and show off their rides. We had 75

cars show up, and, thanks to the tireless

efforts of Carl Wright, six of our own ve-

hicles were running in time for the event.

Cars as old as 1917 and as new as 2012

On April 15, 2012, War Eagles Air Museum hosted a gathering of more than 75 classic,

historic and exotic automobiles on the ramp. In addition to the lineup of Chevrolet Corvettes of

various model years in the first row, Ford Mustangs are well represented (check out the classic

‘65 in the back), as well as Ferraris, Lamborghinis and other rare and beautiful marques.

![Desperado [Eagles]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/56d6be511a28ab3016919a17/desperado-eagles.jpg)