Feature article on guitarist and composer vahagni on Fingerstyle 360

-

Upload

vahagn-turgutyan -

Category

Documents

-

view

162 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Feature article on guitarist and composer vahagni on Fingerstyle 360

29

VahagniWorld Flamenco

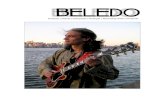

Vahagn Vahagni Turgutyan was born in Yerevan, Armenia in 1985 and was raised ina family of Artists; Vahagni’s father Sarkis Turgutyan was a guitar soloist for theNational Philharmonic of Armenia, mother Satenik ShahNazaryan, a theatricalactress, and Uncle Artur Shahnazaryan, an Ethno!Musicologist and National ArtisticDirector of Armenia. All influenced and nourished Vahagni’s musical development.

Vahagni (pronounced vah!hog!knee) began playing guitar at the age of nine underthe instruction of his father. At a very young age, he showed a great interest in fla!menco music. After several years of studies with his father, Vahagni embarked onthe first of his numerous trips to Andalusia, Spain. Under the guidance of worldfamous flamenco guitarist Paco Serrano, he spent over two years mastering hiscraft, and participating in numerous Festivals in Andalusia. During the CursosSuperior del Guitarra Flamenca held in Malaga, Vahagni got the opportunity to playfor his childhood idol and legendary flamenco guitarist, Manolo Sanlucar. It wasVahagni’s original and unique sound that impressed the maestro, which led to a rareoffer to study as a disciple of Sanlucar.

Vahagni’s guitar playing has taken him on several World Tours, Festivals, Clinics andappearances on TV and Radio shows. He has been featured by the CaliforniaPhilharmonic and was the feature soloist for the Pacific Shores Philharmonic. Asidefrom performing, Vahagni also writes a column for Fingerstyle 360 guitar magazineentitled Flamenco!ology, and is currently a Teaching Assistant for the guitar depart!ment at California Institute of the Arts where he has earned his MFA degree.Vahagni is proudly endorsed by La Bella strings, Godin guitars and German VazquezRubio guitars.

I’m very impressed by your new recording. Please tell me about the writing andrecording of this new project.We recorded the album in April of 2011, and I wrote the material about a yearbefore that. We went into the studio and tracked everything live in three orfour days. It was myself on guitar, Tigran Hamasyan on piano, Jimmy Branly ondrums, Hamilton Price on bass, Artyom Manukyan on cello, and GerardoMorales on percussion.Most of the music is influenced by the fla!menco tradition, but I’ve lived in LosAngeles since I was six years old so Ihave been exposed to a lot of otherinfluences. We rehearsed for aboutthree days before the session. When wewent in, we just knocked it out – it wasa lot of fun!I hear the flamenco tradition and tech-niques, but I also hear harmonic ele-ments that I do not hear in tradition-al flamenco. Would this beaccurate?Yes, of course. Many peo!ple think of flamencomusic as folk music, butit’s not. Like jazz, it’s agenre that comes from aspecific culture inAndalusia.As a composer, you haveto feel free to expressyourself, just like otherforms of music. The onlydifference is that in flamen!co you have to stay true tocertain forms and structures.I have many influences — Ilisten to jazz, classical, andjust about anything youcan imagine. The wayI hear flamencomusic is a little dif!ferent than someothers. I’m notSpanish and I didnot grow up in

31

Spain.Also, my own Armenian culture influences me greatly.I’ve always had a flirtation with jazz, rock, and classicalmusic but I would never call myself any of these. Mytechnique and approach is definitely flamenco — but

the way I hear music is more open.You say your Armenian culture has had an influence onyour music, will you expand on that thought?Well, I grew up listening to Armenian music and it’salways been part of my life. Part of it is just an uncon!scious process. It’s in your blood whether you like it or

not. Some of it is more deliberate. I’ve analyzed andstudied Armenian music. There are many interestingways you can melodically approach the music and feelthe music. I also arranged an Armenian folk song that Irecorded on the album.There are some unusual clusters ofsounds in the recording. As far asnotating the music, did you use chordsymbols or just write out all the notesand voicings?Both. When you are trying to notateflamenco music, it becomes very diffi!cult. Flamenco has always been anaural culture, not a scholastic culture.It’s very unique and you just run outof ways to notate something or it’sjust unclear. I use standard chordnotation when it’s clear, but when itis not I write out all the notes. Evencertain bass lines will be written out.It’s very difficult to write a lead sheetfor flamenco. I’m still trying to per!fect that, it’s an art. Thank God, wehave time to rehearse! The track “De!construction” is a tra!ditional bulerias and was improvised.The transcription “Orion” is a shorterexample of a traditional bulerias. Onthe CD Gerardo Morales played fla!menco cajon and palmas, TigranHamasyan played piano. Tigranlearned the entire piece by ear! Wejust spent hours playing and talkingthrough it. This track just had to havea traditional bulerias approach.After listening to your recording, Iwatched a few YouTube videos on theart of palmas. One had a graph indi-

cating the beats as the examples were demonstrated,very impressive! Please tell us about that tradition andhow you learned the art.In Spain, there are certain people who specialize in pal!mas, that’s what they get called for. It’s definitely an artand not just clapping! (Laughter). It’s literally like

Vahagni

32

treating your hands like an instrument. There are twoseparate sounds — Sordas is the more bass sound thatyou do with the palm of your hand. Claras is the moretreble sound where you use your fingers to clap intothe palm. To master the art and get it consistent is verydifficult. You have to really understand the metric cycleand the form. In Spain where I studied, I sat in on danceclass to learn how to play accompaniment and at firstthey did not want me to play guitar, they just wantedme to clap. You try to feel the metric cycle and therhythm before actually playing the guitar. Once youhave that going, they’ll let you play (laughter). It’s animportant art that should be taken seriously.Let’s talk about your study in Spain.I started playing when I was nine years old. For as longas I can remember, I’ve had the guitar in my hands. Myfather is a great classical guitarist and interpreter offlamenco music. He started teaching me seriously whenI was nine. I started playing flamenco right away, that’swhat attracted me. I stuck to it and only wanted to playanything and everything that had to do with flamencomusic. When I was eighteen I went to Andalusia, Spainto study with the great flamenco guitarist Paco Serrano.Even though I had been playing flamenco for years,once I was exposed to the culture, it was like learninghow to play flamenco all over again. It was a very vitalexperience for me. I spent hours upon hours playingand taking lessons, that’s all I did. I also had the privi!lege of studying with Manolo Sanlucar who was one ofmy idols growing up and still is. He taught me a lotabout composition and being an artist. When I camehome, I had all this information to digest. Eventually itall started to blend in with my own experiences — myown approach started to form. I go back as often aspossible to stay in touch and feed that flamenco soul. You said the culture affected your flamenco playing.Please expand on that thought.It’s not just about the playing aspect. You have tounderstand that flamenco is a culture. When you go toAndalusia and walk in the streets or go to what theycall tabloa, which are little flamenco clubs, you feel thatculture. If it’s hanging out with those musicians orbeing under that sun, I don’t know, but there is some!thing about that location that gives you something spe!cial, an energy, it’s very important. It helps so muchwith your playing, just being there and understandingthat culture. I practiced all day and went out at night,watched shows, drank beer, hung out with other fla!menco artists, and talked about flamenco. That wasmore important than locking myself up and just practicing.

My music has so many influences — I think of myselfjust as a guitar player and not a flamenco guitarist.Even though flamenco is my foundation, I am alwayscareful of calling my music flamenco. I have a lot ofrespect for that culture and I would not want to distortit in anyway. With regard to marketing, it must make it difficult todescribe the music.It really is because it cannot be put in a box. You cannotsay this is what it is and put a label on it. Unless you areplaying a straight!up style that has a long history itmakes it hard to define. Most of the time, I do not knowwhat to call it. I guess the closest term would be worldmusic.One of the things that’s exciting about flamenco is therapid-fire scale technique. Not many classical guitaristsever reach that kind of speed. Will you address this?It’s part of the game. You develop these techniquesbecause that’s what the music calls for. It’s never mis!cellaneous or just for the sake of playing fast and loud.A lot of the flamenco repertoire is just built that way.From a very young age when you start working onthese techniques, you start to develop these skillsbecause it’s a big part of the music. You’re using yourhands in almost every possible way, you’re using yourextensor muscles from playing all the rasqueados.I’ve heard that a big part of why flamenco players canplay fast, ‘machine gun like lines,’ is because their exten-sor muscles are so developed from playing rasqueados. Isthat a big factor?It helps because you are developing the full potential ofyour hand, but conceptually you have to understandhow to do these techniques to get the right sound, andthat takes a little more work. It’s not just about playingfast. Many people can play fast, but very few can playvery clean, very staccato, very aggressively. The bestexample of this is Paco de Lucia. When you say machinegun, Paco is the first that comes to mind. When he playsit’s depressing in a sense. You just want to give up andsay, you know what…to hell with this! It takes a lot ofhard work and really understanding how to do it.When you say, understanding how to do it, are you refer-ring to the staccato playing and getting your fingersback to the strings quickly? I would love to do a column on flamenco scale tech!nique and really get in depth with it. It’s a technique

called picado. It’s basically like the classical rest strokebut the flamenco way. There are a couple differentapproaches, but the way I play comes from the Paco deLucia school of trying to minimize movement. It’s also

using the third joint as much as possible instead ofmoving the whole finger from the knuckle. This helpsminimize the movement. The aggressive attack has todo with how you place the finger. You do not want toomuch flesh because you don’t want that double bumpwith the nail. Yet, you also do not want all nail. Youwant the string to be played from the place where theflesh meets the nail. You pluck up and in at the sametime and that produces a snappy sound. You have todevelop placing the finger in the same place no matterhow fast or slow you play. Once you get the correctapproach, speed works itself out over time.I have a feeling that many people have wasted a lot of

time not approaching the development of speed with thecorrect approach.I like to break it up into two ways of thinking: One isthe actual approach, the science. You haveto understand how your finger should bemoving, how your nail is shaped, the posi!tioning of the right hand, how you’re attack!ing the string, etc. The speed aspect is acompletely different thing. Once you do thework, I look at speed almost as a sport. Youdo it the same way an athlete trains. Youdon’t quit and you give it the time itdeserves. If you do it the right way, you willbe productive and not have to play yourhand off. The force also comes from your wrist. Thewrist is the foundation of your hand. Whenusing more of your first joint you can leaninto the string. The upper joint is going tomove if you like it or not but you’re tryingto minimize the motion. You’re trying tolean into the string. Sabicas was more oldschool and actually used more of the upperjoint. It worked fine for him. He was justflawless and an amazing guitarist. I have amore contemporary approach like Paco deLucia.

I’m not an expert on flamenco, but I loveSabicas.Oh yeah. There are so many important gui!tarists of his generation such as NinoRicardo and Melchor de Marchena, but Sabicas put abig dent in the flamenco guitar. From his refined tech!nique to his compositions, his style changed the game.Each generation has a group of players who elevate theart. Then Paco de Lucia came along and took it tensteps further.

I assume there are many respected flamenco guitaristswho are better known for their accompaniment tosingers and dancers than as soloists. Yes, that’s a very important art. They all play their assoff, but they put their focus on accompaniment whileothers focus on solo playing. I cannot say one is more

33

Vahagni

34

important than another. They are equally important tothe art of flamenco.Have you played behind flamenco singers and dancers?I have, when I was younger. It’s a crucial part of learn!ing to play flamenco. You get a lot of the rhythm andthe soul of flamenco from playing behind singers anddancers. After all, this was the original purpose of fla!menco guitar, there were no soloists.When you want to playsomething that is cultural,you need to start at thebeginning. You may want tobe an abstract painter, butyou have to learn to paintfirst.How do you handle the guitarbeing heard when you areplaying live with piano, bass,and drums?It’s difficult with the acousticguitar, but I try to blend themic sound with the LR BaggsHex pickup through a RolandAcoustic amp. It’s alsoimportant that the musiciansunderstand dynamics andknow how to play with theacoustic guitar. It’s almostlike playing chamber music.Who built your guitar?German Vasquez Rubio — he is a very well knownbuilder in LA. He is very precise with his work and avery sweet person. He puts a lot of care into his instru!ments. I have loved his guitars for a long time.Please tell me about your approach to practicing.I like to break my practice into group, technique, reper!toire, improv, and composing. When I practice, I have aroutine of warming up, stretching and basic warm up. Ilike to be pretty agile once I dig in. You can waste a lotof time practicing if you do not have a focus. I try topractice with a goal. I set a goal and do what I can toachieve that goal. I’m still young, but as you get older,your time becomes more valuable.You mentioned your father and that he is also a great

guitarist. Please tell me a little bit about him.His name is Sarkis Turgutyan. My father started playingguitar very young, in Armenia. At that time, Armeniawas part of the Soviet Union and in those days therewas no conservatory or school that taught classicalguitar. He was pretty much self!taught. He worked veryhard at it and it led him to being the guitar soloist forthe National Philharmonic. He was very successful! Hewas a diplomatic artist as they called it in those times.

When he saw Paco de Lucia, he was blown away andstarted to investigate flamenco guitar. It was very diffi!cult at that time to learn another culture’s musicbecause the Soviet Union was very strict. It was almostimpossible to get any information. He would occasion!ally get a few rare recordings and learn from them. Itwas the breakup of the Soviet Union that opened thingsup. My father is the most important teacher I’ve had. Hetaught me everything I know about playing the guitar.I’ve always said he is one of my favorite guitarists.[Editor’s note: Solitude is available as of August 28th,2012 on Ingrooves/Fontana- Universal Music]Broken Compass will be released October 9th, 2012 onLMS Records. Pre!sales are available now athttp://lmsrecords.bandcamp.com/album/broken!compass—Bill Piburnwww.vahagni.com