Fear of water in children and adults: Etiology and familial effects

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

jacqueline-graham -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

4

Transcript of Fear of water in children and adults: Etiology and familial effects

Pergamon S0005-7967(96)00086-1

Behav. Res. Ther. Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 91-108, 1997 Copyright © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd

Printed in Great Britain. All fights reserved 0005-7967/97 $17.00 + 0.00

F E A R O F W A T E R I N C H I L D R E N A N D A D U L T S :

E T I O L O G Y A N D F A M I L I A L E F F E C T S

JACQUELINE GRAHAM ''2 and E. A. GAFFAN ~'* ~Department of Psychology, University of Reading, Reading RG6 6AL, U.K. and -'Department of Clinical Neurology, University of Sheffield, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield S10 2JF, U.K.

(Received 26 August 1996)

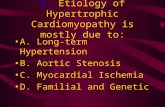

Summary--Water-fearful children (non-swimmers, 5-8 yr) and adults (non-swimmers or late learners, 23-73 yr) were compared with non-fearful controls of similar swimming ability. Parallel assessments were carried out with children and adults to investigate water-related experiences, water fear and com- petence in parents and siblings, and the relationship of water fear to other fear dimensions. Children were assessed behaviorally and by self and mother's report, adults by self-report. In neither children nor adults was there clear evidence that fearful and non-fearful groups differed in incidence of aversive water-related experience before fear onset. Parents usually believed that children's fear was present at first contact. In both samples, we found parent-offspring and sibling resemblances in fear. Analysis of details of children's contact with parents suggested that social learning within the family decreased water fear rather than increasing it; when both child and parent showed fear, that was as likely to reflect genetic influences as modeling. Young children's water fear forms part of a generic cluster, fear of the Unknown or Danger, while in adults it becomes independent of generic fears. Copyright © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Many accounts of the origin of specific fears and phobias have proposed a role for associative learning. Such learning might take many forms. The 'three pathways' posited by Rachman (1977) were classical conditioning, where the potential phobic stimulus is experienced in conjunc- tion with another, genuinely painful or frightening situation; vicarious learning, where another person is seen showing fear or distress toward the phobic stimulus; and information, where the association of the phobic stimulus with danger is acquired via words or pictures, not direct ex- perience. McNally and Steketee (1985) and Barlow (1988) suggested that, in conditioning, the critical associate might be one's own fearful reaction (S-R association) rather than a genuine external threat (S-S association). Others have emphasized different kinds of associative event, and considered the role of predispositions and of prior and subsequent experience also (Cook & Mineka, 1991; Davey, 1992; Ohman, Dimberg & Ost, 1985). All these accounts, while varying in detail, assume that associative experience of some kind is crucial to the instigation of phobias.

That assumption is rejected by an alternative, nonassociative account, originating with the speculations of Darwin (1877), further developed by others such as Marks (1987) and Gray (1971), and most recently by Menzies and Clarke, 1993b, 1995b. According to this view, stimuli such as darkness, heights, deep water, strangers, certain animals, separation from parents, and so forth do (or did in the past) represent genuine threats to humans or their ancestors--perhaps more so at some stages of development than at others. Some degree of fear toward such stimuli promotes survival, and we all tend to fear them without the need for associative learning. Life events such as emotional states or stressors may modulate the fears, but are not primary causes. Some such fears (strangers, darkness) naturally wax and wane during childhood. Others nor- mally habituate over time (Clarke & Jackson, 1983), or become redundant because we acquire other ways of coping, but some people lose them less completely than others, and are left with a fear which seems extreme or irrational compared to the norm.

*Author for correspondence.

91

92 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

Any discussion of the etiology of fears and phobias must take into account the evidence for a genetic component, particularly from twin studies, (e.g. Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath & Eaves, 1992; Stevenson, Batten & Cherner, 1992; Torgersen, 1979). Fyer e t al. (1990) found that the incidence of simple phobias was higher among all first-degree relatives of probands with simple phobia than among relatives of controls without psychiatric diagnosis. The correlation among relatives, which is also seen in the case of social phobia and agoraphobia, is specific to each class of phobia, i.e. it does not merely reflect generalized susceptibility to anxiety disorders (Fyer, Mannuzza, Chapman, Martin & Klein, 1995). Familial aggregation of a given type of phobia could, of course, reflect shared genes, vicarious learning or other common experiences within the family.

In this study we focused on fear of water and swimming, a common problem of childhood (Menzies, in press) which falls in the category of survival-relevant fears to which the nonassocia- tive account seems most applicable. It also plausibly offers scope for vicarious learning, because children commonly have their early experience of deep water and swimming in the company of parents or other family members. We set out to investigate whether there is any evidence that fears of water and swimming, in children and adults, result from specific associative experiences, vicarious or otherwise. We also examined relationships between respondents' fear of water, and the water-related competence of their parents and siblings, which as noted above may reflect either genetic or social learning influences.

The only logically secure way to find whether associative experiences are causal would be a prospective study of what life experiences predict later development of a phobia (Ost, 1991). That method is clearly impracticable for most types of phobia. Another approach is to study the after-effects of known traumatic events; for example, Yule, Udwin and Murdoch (1990) found that children who had survived the sinking of a ship 5 months earlier, reported strong fear of deep water, swimming and other related stimuli, compared to control groups. That study shows that fear of water can be elevated by a conditioning experience, but not that it commonly arises that way. Nearly all research on phobic etiology has used retrospective methods, and we used them also. The problems of retrospective research in this field are formidable (Menzies & Clarke, 1994). Many studies, including the well-known series by Ost and colleagues (Ost, 1991; Ost & Hugdahl, 1981, 1983, 1985) have asked a sample of fearful or phobic respondents to report experiences which might be responsible for the onset of their fear, using a questionnaire (Ost & Hugdahl, 1981) or a structured interview (McNally & Steketee, 1985). The experiences are classified into one of the putative categories of associative learning, such as conditioning, vicarious learning etc, and conclusions are drawn on the basis of the proportion of respondents who nominate various pathways or, by contrast, can recall no relevant experience at all. For example, between 40 and 80% of phobic clients tested by Ost and colleagues endorsed 'conditioning' items, from which it was inferred that conditioning is the most important single pathway to acquisition.

There are many problems with such inferences. Phobics might fail to remember, or misreport experiences which did occur, or wrongly believe them to have occurred before onset of the pho- bia whereas in fact they occurred later. The classification of experiences may be questionable and be constrained by researchers' preconceptions (Menzies & Clarke, 1994). Moreover, studies of the aforementioned kind lack control groups. Even if the proportion of phobic patients who had a particular associative experience prior to the onset of the phobia could be validly measured, we cannot infer that the experience had a causal role unless we have evidence that phobic patients are more likely to have had such experiences than are comparable non-phobic people.

Examples of controlled comparisons which used adult respondents focused on fear of dogs (Di Nardo, Guzy, Jenkins, Bak, Tomasi & Copland, 1988; Doogan & Thomas, 1992), dental anxiety (Davey, 1989; de Jongh, Muris, ter Hurst & Duyx, 1995), fear of heights (Menzies & Clarke, 1993b, 1995a), and public-speaking or social anxiety (Hofmann, Ehlers & Roth, 1995; Stemberger, Turner, Beidel & Calhoun, 1995). They too are subject to methodological pitfalls. Control respondents cannot be asked about experiences to which they attribute onset of a non- existent fear or phobia. So, if the same questionnaire or checklist is given to both groups, it

Fear of water in children and adults 93

must be neutrally worded, but then it may not be clear whether the fearful group's experiences preceded or followed onset of the fear.

Even bearing the above in mind, the results imply a need to reconsider the inferences drawn from uncontrolled studies. The proportions of non-phobic controls who report conditioning and other associative experiences are often high, sometimes equal to the proportions of phobics who do so (Di Nardo et al., 1988; Menzies & Clarke, 1993b, 1995a). Even where they do differ, the differences may be ambiguous, because some reported experiences certainly occurred after pho- bia onset (cf. Hofmann et al., 1995).

Because of the problem of the long time-span, leading to uncertainty about when experiences occurred, some controlled studies have examined fears and phobias in children, nearer to the time of onset. Ollendick and King (1991) selected ten fears which are common among 9-14 yr old children, and compared the proportions of low and high-fear respondents who reported direct conditioning, vicarious and informational experiences. Doogan and Thomas (1992) asked 8-9 yr old children with low and high fear of dogs about a similar range of experiences. Ollendick and King found that low and high-fear children differed in that those with high fear were more likely to report mult iple types of experiences, for example conditioning plus informa- tional; but it is implausible that all these occurred before the onset of fear. The only group differences observed by Doogan and Thomas were on items which could have resulted from already-present fear, viz. "being frightened by a dog" and "being distressed by press reports of dog attacks". Such findings have not clearly revealed the extent to which experiences are causes or consequences of fear.

Ollendick and King warned that even children's self-reports entail retrospection, and may be less valid than those of adults, so some researchers have used parents as informants. Milgrom, Mancl, King and Weinstein (1995) questioned mothers, and tried to discover what variables dis- tinctively predicted whether children had high or tow dental anxiety. Inspection of their data suggests that few if any of the predictive variables could be characterized as any kind of associ- ative experience. The only study of the role of experience in children's fear of water, by Menzies and Clarke (1993a), also obtained information from parents. One parent of each of 50 young water-phobic children was asked which, out of a list of experiences corresponding to Rachman's associative pathways, they considered to have had any influence on the origin of their child's fear. They were allowed to answer 'none', meaning that the fear had been present before any relevant experience occurred. Menzies and Clarke concluded that the results favored the nonas- sociative account, because most parents (28, or 56%) replied that the child had always been fearful. Only 14 parents mentioned any associative experience, and most of these were classified as vicarious experiences involving family members. It is possible, therefore, that associative learning played some part, but the strength of its contribution cannot be assessed because there was no non-phobic control group. Moreover, as noted above, relatives' fear may implicate gen- etic factors rather than vicarious learning.

Other published reports relevant to the etiology of fear of water are by Rose and Ditto (1983) and Phillips, Fulker and Rose (1987). They used the Fear Survey Schedule (FSS-II) of Geer (1965) which assesses self-rated fear of 51 items including three--'deep water', 'swimming alone' and 'boating'--that are water-related. Factor analysis of the FSS-II yields a Fear of Water fac- tor (Bernstein & Allen, 1969; Rubin, Katkin, Weiss & Efran, 1968).

Rose and Ditto (1983) administered the FSS-II to 354 pairs of like-sex twins aged 14-34, and carried out hierarchical regression analyses on the Fear of Water factor scores and 6 other fac- tor scores derived from the FSS-II. They found that about 20% of variance in Fear of Water scores could be accounted for by co-twin's score, and about 0.5% more by the interaction of co-twin's score and the MZ-DZ difference. The latter component, which most probably indicates genetic causation, was significant for all fear factors. The simple co-twin correlation could be genetic or environmental in origin. Phillips et al. (1987) analysed FSS-II data from 250 adult twin pairs, 91 sibling pairs (all same-sex) and their parents. They fitted a multivariate model-- incorporating standard genetic components plus a variety of other parameters e.g. assortative mating, gene-environment correlations and non-genetic (environmental or cultural) correlations between family members--to the matrix of correlations between fear scores. Heritability esti- mates for the 7 fear factors ranged from 19 to 39%, Fear of Water being almost the lowest at

94 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

20%. These values are somewhat lower than those reported by the previously cited twin studies, probably because Phillips et al.'s model separated direct inheritance from other sources of kin correlation. However they agree with previous studies that what is inherited is to some extent specific, not a general susceptibility to fear.

Phillips et al. concluded that there was some evidence for assortative mating as a secondary source of correlation between siblings, and for correlated environmental influences in the case of twins only, but not for any additional 'environmental' correlation such as cultural transmission between parent and offspring. Davey, Forster and Mayhew (1993b) comment that this con- clusion is so much at odds with clinical experience as to cast doubt on the validity of the model- ing technique. We would add that such techniques, by definition, can only specify potential causes which are correlated between relatives, and not those which are uncorrelated, e.g. idio- syncracies of experience, parent-child interaction or personality. To find whether experiences are in fact relevant, we must try to assess what specific experiences people have had.

In our study, we compared fearful and non-fearful respondents, both children and adults. Information about possible associative experiences, and relatives' swimming competence, was obtained from parents in respect of the children. The children were young enough that parents' memories should be recent. Our adult respondents, necessarily, were given retrospective ques- tionnaires. We asked what experiences or familial associations are distinctively found among water-fearful individuals.

When considering effects of any variable, experiential or familial, on fear of water, it must be borne in mind that fears of certain items are intercorrelated, and such effects might operate on a cluster of linked fears of which 'water' forms a part. As mentioned above, Geer's FSS-II (1965) contains a separate Fear of Water cluster. However, the most widely used Fear Survey Schedules, namely the FSS-III for adults (Wolpe & Lang, 1964, 1969) and the FSSC-R for chil- dren (Ollendick, 1983) include only one water-related item, for example 'Deep water or the ocean' in the FSSC-R.

Factor analysis of the FSSC-R reliably yields 5 factors, called the Unknown, Failure and Criticism, Danger and Death, Injury and Small Animals, and Medical Fears, which have been replicated in American, Australian and British samples (Fonseca, Yule & Erol, 1994). The 'Deep water' item most consistently loads on the Unknown factor, which also includes items such as crowds, dark or enclosed spaces, nightmares, isolation, thunderstorms and travel. It should be noted that in Yule et al.'s (1990) study of children who had experienced the sinking of a ship, many fears in the 'Unknown' cluster were elevated, not water-related ones alone. This may have reflected the fact that their traumatic experience directly involved travel, darkness and crowds, or rather that this entire cluster of fears was enhanced. Similarly, the twin studies which provide evidence for heritability of fears in fact analysed fear clusters or factors, rather than in- dividual items (Stevenson et al., 1992; Torgersen, 1979). Muris, Steerneman, Merckelbach and Meesters (1996), who also employed the FSSC-R factors, showed that Dutch children's factor scores were predictable from their mothers' (but not fathers') total FSS scores, over and above potential confounding variables such as trait anxiety, age and gender. They also found evidence consistent with maternal modeling, in that children's FSSC-R scores were additionally predicted by mothers' self-reported tendency to express fear in the child's presence. Because so much of the relevant evidence implicates clusters of fears, rather than individual items, we also examined the relationship of fear of water to other items in both our child and adult samples.

Factor analysis of the adult FSS-III has a more complex and controversial history which need not be reviewed here (Arrindell, Emmelkamp & van der Ende, 1984; Arrindell, Pickersgill, Merckelbach, Ardon & Cornet, 1991). Adult samples, unlike children, do not characteristically show a strong loading for the water-related item 'Sight of deep water' on any of the major identified factors.

In summary, our study comprised 2 parts:

(1) Thirty-three non-swimming children, aged 5-8, were divided into groups according to their fear of water. Their parents completed a questionnaire asking about the children's previous water-related experiences, and the water attitudes and competence of themselves and other family members. Both mother and child responded to a shortened FSSC-R.

Fear of water in children and adults 95

(2)

The aim was to determine whether the experiences of the groups differed as expected by associative models of acquisition, and whether there were familial effects in water compe- tence consistent with genetic transmission or vicarious learning. We also examined the re- lationship of water fear to others within the shortened FSSC-R. Eighty adults who had either recently or never learned to swim responded to a question- naire which tapped information about experiences and family members' water compe- tence, similar to that obtained about children in part 1. They also completed the FSS-III. The aims were to assess factors in the origin and maintenance of water fear, as in part l, and to examine the relationship of water fear to other fears.

M E T H O D

Subjects

Sample 1: non-swimming children and their parents. Thirty-six children (aged 5-8) were selected. They comprised all who could not yet swim among those who were currently attending weekly swimming lessons for beginners, together with their mothers, at a sport and leisure centre in a southern English town. Three families failed to complete all measures, leaving 33 children in the sample. The children's behavior in the swimming-pool was observed by the first author, a professional swimming teacher. She scored their performance on 7 water skills suitable for non- swimmers (entering the water, walking through the water, blowing bubbles, leg kicking while holding the side, floating supine with aids, immersing face in the water, jumping into the water). For each skill, they were awarded 2 points for spontaneous completion, 1 point for hesitant or assisted completion, and 0 points if unable to perform it. Nine children scored less than 10 points overall and were classified as showing 'Current Fear' of water. Twelve children were not currently fearful but were reported by parents to have shown fear in the past, these were classi- fied as 'Losing Fear'. The remaining 12 children, who showed neither current avoidance nor past avoidance according to parents, formed the 'No Fear' group. Table 1 shows the age, gen- der, sibling and parent composition of the groups (see Results for comparisons). Socioeconomic details were not collected. All children lived either with two biological parents, or with their mother alone.

Sample 2." adults. The sample comprised 80 adults, 46 women and 34 men, ranging in age from 23 to 73 yr (mean: 46 yr 10 months) who were attending swimming lessons in two southern English towns. The inclusion criterion was either that the person could not swim, or had learned to swim within the last 5 yr and at age 18 or older.

Measures

Sample 1: non-swimming children and their parents

(1) Child Fear Origins Questionnaire. This was modeled on one used by Menzies and Clarke (1993a) and was completed by the mother with reference to the child. The purpose was to ascertain whether the water-fearful and non-fearful children differed in their exposure to aversive water-related events. One or more questions were included to investigate the occurrence of direct conditioning experiences of the S-S type (e.g. "Has an incident occurred in or near the water in which your child was really in danger?") or S-R type (e.g. "Has your child ever become upset by something while in or near the water, even though there was no physical danger?"); vicarious conditioning experiences (e.g. "Has your child ever seen someone else harmed or in trouble in or near the water?") and nega- tive information (e.g. "Have you or your partner ever told the child that water-related ac- tivities may be dangerous?"). The mother responded 'Yes', 'No' or 'Don' t know' to each question. A second section invited her to make a causal attribution for the child's fear of the water, if fear had ever been shown. In addition to the above three routes to fear, there was a 'No cause' option (in which fear had always been present from first contact), an 'Unknown cause' option (in which fear had not always been present from first contact,

96 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

(2)

(3)

had subsequently developed but from no known cause), and an 'Other cause' option, where a brief description was asked for. Family Water Attitudes Questionnaire. This was compiled by the authors, and aimed to assess familial influences on the child's fear of water. Information was collected from the parents about the current swimming ability and water attitudes of all immediate relatives (and any additional people) who had previously entered the water with the child. Each parent responded on his or her own behalf, and one parent (usually the mother) provided information about siblings or others. General swimming ability of parents and siblings was rated on a 3-point scale; 'non-swimmer', 'weak swimmer', 'average/strong swimmer'. The fear of water currently shown by any siblings was assessed on a 3-point scale (as in the FSSC-R, below)--'None', 'Some', 'A lot'. The water attitude of the parents was assessed by asking whether they currently felt apprehension toward the deep end of a swimming pool, or the sea ('Yes'/'No' response to each). Each parent also rated his or her own fear of water in childhood, on the FSSC-R 3-point scale. Shortened Fear Survey Schedule for Children--Revised. The Shortened FSSC-R, compiled by the authors, comprised 13 items plus 3 'fillers', and was designed to approximate the full 80-item FSSC-R in a format more suited to young children's attention span. To maintain the factorial balance of the original FSSC-R, the shortened version was con- structed from 20% of the items from each of the five factors. Two items, 'Deep water or the sea' and 'Not being able to breathe' were included because of their relevance to water fear. The remaining FSSC-R items were selected because they loaded well on their re- spective factors and were among those reported to be highly fear-evoking by a normal child population (Ollendick, 1983). The complete set was: 'Being punished by a parent', 'Making a fool of yourself', 'Failing a test' (Failure and Criticism factor); 'Deep water', 'Strange looking people', 'Dark places' (the Unknown factor); 'Bears or wolves', 'Snakes', 'A burglar breaking into your house', 'High places' (Injury and Small Animals factor); 'Not being able to breathe', 'Being hit by a car' (Danger and Death factor); and 'Having to go to the hospital' (Medical factor). Three non-aversive filler items ('Having a picnic with your family', 'Rabbits', 'Cartoons on television'), were added, to decrease the sever- ity of the measure. The question-response format was similar to the FSSC-R (cf. Pro- cedure). The Shortened FSSC-R was completed both by the child (in interview format) and by the mother, with reference to herself. The parental version differed only in that 'Being criticised by a work mate or friend' was substituted for 'Being punished by my parents'.

Sample 2: adults

(1) Fear Survey Schedule III (FSS) (Wolpe & Lang, 1969). This is an extended version of the standard 76-item FSS-III (Wolpe & Lang, 1964) comprising 108 items to which the self- rated degree of discomfort was expressed on a 5-point scale ('None at all' to 'Very much').

(2) Adult Fear Origins Questionnaire. This was a self-report inventory, compiled by the authors, concerned with factors potentially involved in the etiology and maintenance of adults' fear of the water. The respondent's current swimming ability was recorded on a 3- point scale ('Non-swimmer', 'Weak swimmer', 'Average/strong swimmer') and their fear of the water in childhood was rated on the FSSC-R response scale ('None', 'Some', 'A lot'). Information as to whether each of the repondents' parents could swim, and whether specific relatives (parents, siblings or children) had shown apprehension toward the water at any time, was collected using the response scale 'Yes', 'No', 'Can't remember'. Finally, the categories of aversive water-related events included in the Child Fear Origins Ques- tionnaire were listed, and respondents were asked whether "any of the following events happened, in your lifetime, which made you wary or cautious around the water". The same questionnaire was completed by all respondents, whatever their water fear or swim- ming ability. The wording was designed to elicit memories of aversive events without necessarily implying a causal attribution for lasting or current fear.

Fear of water in children and adults 97

Further details of all non-standard questionnaires are available from the authors.

Procedure

Sample 1: non-swimming children and their parents. All procedures followed with children and parents were approved by the University of Reading Ethics and Research Committee.

Each child's mother was approached at a swimming class by the first author. The mother was given copies of all questionnaires and told that we were interested in both non-fearful and fear- ful children. She was assured that whether or not she chose to participate in the study would make no difference to the swimming instruction received by her child and given a consent form to be signed by her and, if possible, the child.

The Child Fear Origins and Family Water Attitudes questionnaires were given to the mother, who was asked to pass a copy of the relevant section of the latter to the child's father (if avail- able) for completion of the items applying to him. They were completed at the parents' leisure and returned at a later swimming lesson. The child's interview, at which the Shortened FSSC-R was given, took place at that time.

The Shortened FSSC-R was administered to the child individually, before or after his or her weekly lesson. The interview was conducted on the poolside, equidistant between the shallow learner pool in which the child received lessons, and a large deeper pool which the child would rarely or never have entered. Each child was given the following instructions: "I am going to read you a list of things that some boys and girls are frightened of and some boys and girls are not. I want you to tell me if these things frighten you. Shall we have a practice?... Are you frigh- tened of Father Christmas?". The researcher stressed that the child should "think hard" before answering. Each item was read out in the following format: "Are you frightened of..?". If the child answered "yes", they were then asked "a little bit, or a lot?". The researcher was careful to ensure the child understood each item before answering. If necessary, the item was slightly re-worded. For example 'burglar' was more often understood as 'robber'.

Sample 2." adults. Copies of the FSS-III and the Adult Fear Origins Questionnaire were given out at swimming lessons, for completion (in the order given) in respondents' own time, and returned at a lesson or by mail. No personal details were requested other than gender and age.

RESULTS

Sample 1." non-swimming children and their parents

Many variables measured in this study employed 3-point scales which were not normally dis- tributed; when analysing those variables, we used nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U or Spearman's rho).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the three groups: No Fear, Losing Fear and Current Fear. An unanticipated finding was that the two fearful groups included relatively more first- born children, Z2(2) = 6.47, P < 0.05, and it can also be seen from the table that all the chil- dren who had two older siblings were in the 'No Fear' group. These were not consequences of the groups differing in age, F(2 ,30)= 1.09, or overall family size, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, X/(2) = 2.39. Consistent with the birth order difference, the two fearful groups were more likely to have a younger sibling, but not significantly so, X2(2) = 4.21. The groups did not differ in gender composition, ~z(2) < 1, or in the proportion of single-parent families, )~2(2) < 1.

The high proportion of firstborns in the two fearful groups raised the possibility that the differences reflected some effect of birth order on general emotionality, rather than factors specific to fear of water. That possibility is considered below in the analysis of the Shortened FSSC-R results.

Shortened FSSC-R. The intention was to use this simplified schedule to examine children's self-reported fear of water, its relationship to other fears, and parent-child correlations. The non-aversive filler items, as intended, universally received 'No' responses and could be ignored in analysis. One aversive item, 'Failing a test' seemed to be poorly comprehended by most chil- dren, so was dropped, leaving 12 items. In the case of 4 children, the mother requested that the 'burglar' question not be asked, because the family had recently suffered a burglary. Two chil-

98 Jacquel ine G r a h a m and E. A. Gaffan

Table 1. Charac ter i s t ics and FSSC-R responses of Sample 1, non - swimming chi ldren

Group: No Fear Losing Fear Current Fear (n - 12) (n - 12) (n = 9)

Mean (SD) age in months 68 (5.4) 73 (6.7) 71 (10.6) Number (%) of girls 6 (50) 7 (58) 6 (67) Number with:

No older siblings (%) 4 (33) 10 (83) 6 (67) One older sibling 3 2 3 Two older siblings 5 0 0 One younger sibling 1 4 3 Single parent 3 2 1

Mean (SD) of Shortened FSSC-R scales (range 1 3)

Deep water fear 1.9 (1.0) 2.4 (0.8) 2.1 (0.6) Average fear 1.8 (0.6) 2.0 (0.3) 1.8 (0.3)

Girls Boys (n = 19) (n = 14)

Deep water fear 2.2 (0.8) 2.1 (0.8) Average fear 2.0 (0.5) 1.7 (0.5)

dren answered 'No' to every item, and were omitted from analysis, as this might have been stereotyped behavior, which would have spuriously inflated the correlations between pairs of items. The remaining 31 children showed positive correlations among some pairs of items but not others, implying that responding was non-random. Three items were significantly correlated (P < 0.01) with 'Deep water ' - - 'Dark places' (0.48), 'Not being able to breathe' (0.48) and 'Bur- glar breaking into our house' (0.53)--and 2 correlations approached significance, 'Being hit by a car' (0.33) and 'High places' (0.35). Of those 5 items, only 'Dark places' was assigned (in com- mon with 'Deep water') to the Unknown factor in Ollendick's original analyses, the others being assigned either to Danger and Death, or to Injury and Small Animals. Either a different factor structure applied to these children's data, or Deep water had different associations.

There were other signs that the standard FSSC-R item 'Deep water' lacked validity for the purposes of this study. Table 1 shows the mean 'Deep water' fear ratings of all three groups. The Current Fear group did not report markedly higher fear than the others, contrary to what would be expected if this self-report item reflected their observed behavior in the water. The three groups' scores did not differ significantly, Kruskal-Wallis Z2(2) = 2.07. In retrospect, the 'Deep water' item may have been inappropriate for the sample, as all were non-swimmers for whom deep water would be genuinely dangerous, regardless of their fear of water in general.

As a check on the general validity of the Shortened FSSC-R, Table 1 also shows a measure of overall responsiveness, 'Average fear' i.e. the mean score across all items. It is consistently reported that girls score more highly on the FSSC-R than boys (Ollendick, 1983; Ollendick, King & Frary, 1989) therefore Table 1 also shows the 'Deep water' and 'Average fear' scores of all girls and all boys separately. As expected, the girls' means were higher in both cases. To assess the gender difference, and partial out any distorting effect it might have had on the differ- ences among fear groups, we carried out Gender x Group unbalanced ANOVAs on both vari- ables. With 'Deep water' there were no significant effects, all Fs < 1. 'Average fear' showed no effect of Group, F(2,27) = 1.24, nor any interaction, F < 1, but the Gender effect was as expected, F(1,27)= 3.85, P < 0.05, one-tailed. Thus there is evidence of validity for the 'Average fear' score.

There is a suggestion, in Table 1, that the two fearful groups' 'Deep water' scores were further above their 'Average fear' scores, than was the case in the 'No Fear' group. To check this we computed, for each child, the difference between the 'Deep water' rating and the mean rating to all other items of the Shortened FSSC-R. However these were very variable, and did not differ between groups, F(2,29) = 1.01.

The 'Average fear' measure allows a test of the possible artefact mentioned previously, that some differences among the 3 groups might stem from differing proportions of firstborns, caus- ing putatively different levels of general fearfulness. The prevalence of firstborns in the high fear groups is of course potentially important in its own right--see Discussion--but we must ask whether other group differences might simply be by-products of that.

F e a r o f w a t e r in ch i ld ren a n d adu l t s 99

We therefore computed the mean 'Average fear' score separately for the firstborns and the remaining children within each group. These were as follows. No Fear group: firstborns 1.57, others 1.85; Losing Fear group, 2.02 and 1.9; Current Fear group, 1.95 and 1.44. An unba- lanced Birth order (First/later born) x Group ANOVA showed no significant effects, all Fs < 1. Thus, in this sample, although firstborns on average showed slightly higher self-reported fear, the groups did not differ even after taking birth order into account.

In view of the uncertain validity of the children's self-report, especially at the level of individ- ual items, we did not analyse child and parent FSSC-R scores further.

Child Fear Origins Questionnaire. The numbers of mothers who indicated that their child had had any aversive water-related experience in the various categories are shown in the upper part of Table 2. Column totals can exceed the number of children in the group because one child could have had more than one type of experience.

The Negative Information category was most commonly endorsed, because we included under this children whose parents had warned them about risks of water, or who had been taught the Water Safety Code at school. Others were less common. The proportions of mothers responding 'Yes' vs 'No' to each category were compared, disregarding 'Don' t know' responses to that cat- egory. The groups did not differ in prevalence of reported vicarious experiences, Z2(2) = 2.74, or negative information, X2(2) = 1.36, but a difference was present for conditioning experiences, Z2(2) = 6.43, P < 0.05; mothers of children in the Losing Fear group were more likely to report those. (All but one of the conditioning experiences reported, across all groups, were categorised as S -R rather than S-S.)

Interpretation of this last finding must be cautious. The chi-square tests were unreliable due to small expected frequencies, and the questionnaire did not ask whether specific experiences occurred before or after the onset of fear. Thus, it is likely that some of the cited experiences occurred after fear began, and could not be responsible for its origin, although they could have had a maintaining role. The important negative result is that the No Fear and Current Fear groups showed very similar patterns--as has been observed in many analogous studies of pho- bias which included a control group, cf. Introduction--suggesting that the experiences did not have simple etiological relevance of the kind suggested by Rachman (1977).

Mothers who said that their child had ever shown fear of water, i.e. those in the Losing Fear and Current Fear groups, were asked to nominate the most important cause of the child's fear, either from among the events mentioned previously, or some other known or unknown cause-- or whether, alternatively, the fear had always been present, from first contact with water. Any such causes by definition must have occurred before fear onset or at a very early stage. (Mothers were also invited to name subsidiary causes, but few were mentioned and they are not analysed.) The lower part of Table 2 shows how many 'most important' attributions fell in each category. Clearly, many mothers believed the child's fear had always been present, especially in the Current Fear group (7/9, 78%) which was most comparable to the sample studied by Menzies and Clarke (1993a) who also reported a high proportion (56%) of 'always present' attributions.

T a b l e 2. Avers ive exper iences a n d p a r e n t a l a t t r i b u t i o n s for fear: Sample 1, n o n - s w i m m i n g ch i ld ren

Group: No Fear Losing Fear Current Fear (n = 12) (n = 12) (n = 9)

Number of mothers reporting: Conditioning experience 2 7 2 Vicarious experience 5 5 1 Negative information 9 11 7

Number of mothers attributing fear to:

Conditioning experience - - 4 0 Vicarious experience - - 1 0 Negative information - - 0 0 Nothing (fear present at first - - 4 7 contact) Don' t know - - 3 2

100 Jacqueline G r a h a m and E. A. Gaffan

Interestingly, the only attributions to conditioning or vicarious experiences occurred in the Losing Fear group. These were made by 5/12 mothers of children in that group, but by none of the 9 mothers of children in the Current Fear group, a significant difference (P < 0.05) by Fisher's Exact Test. This is a post hoc test whose statistical status is questionable; and, as noted above, mothers of the Losing Fear group reported more conditioning experiences anyway. Nonetheless, the three Current Fear group mothers who did report conditioning or vicarious ex- periences, did not believe they were primarily influential.

Family Water Attitudes Questionnaire--parents' and siblings' water competence. Parents responded to several items concerning their own swimming ability and fear about water, cur- rently and in childhood, and also rated the swimming ability and water fear of any siblings of the target child. The various items tended to be redundant within individuals. If parents' re- sponse to the two questions, whether they currently felt apprehension about the deep end of swimming pools and about the sea, was summed, assigning 1 to a 'Yes' response and 0 to 'No', the sum was strongly correlated with their self-rated swimming ability, 'None', 'Weak' or 'Aver- age/strong'; Spearman's rho, -0.503 for mothers (n = 33) and -0.644 for fathers (n = 26), Ps < 0.01. The same was true of siblings aged 3 or above (children below that age were too young for mothers to judge their reactions to water). Their fear of water as rated by the mother correlated with their reported swimming ability, Spearman's rho -0.79, n = 26, P < 0.001.

When classifying parents and siblings, we constructed a 3-point scale which combined the swimming ability and fear/apprehension ratings. We expressed this as 'Water competence' rather than 'fear', where 1 = Poor competence (high fear), 2 = Moderate, and 3 = Good (low fear). It is preferable to speak of competence because, as argued below, children might acquire positive as well as negative water attitudes from their relatives. All non-swimming parents showed high apprehension ('Yes' to both deep water and sea) and were rated 1 (Poor). Weak swimmers were rated 2 unless they showed no apprehension, when they were raised to 3; similarly, average or strong swimmers were rated 3 but lowered to 2 if they expressed high apprehension. Older sib- lings were scored analogously. Younger siblings were all non-swimmers and were scored accord- ing to their fear rating.

Parents' ratings of their own fear as a child correlated significantly (P < 0.01) with current water apprehension; 0.754 for fathers (n = 24) and 0.538 for mothers (n = 27). Because not all parents answered the question, and it was conceptually distinct, we analysed it separately.

Table 3 shows the mean Water Competence score of mothers and fathers (where present) of children in each group. One child in the No Fear group did not live with his father, but often went swimming with his grandfather, whose water competence was known, so the grandfather was counted as a 'father' in his case. Mean competence of older and younger siblings (over 3 yr) is shown next, across those children who had them. Where a child had 2 older siblings, their competence scores were averaged. Finally, the means of parents' ratings of their own fear of water as a child, on a scale of 1 (None) to 3 (A lot), are shown.

Parents and older siblings of the No Fear group had higher water competence than those of children in the other two groups. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs showed the groups to differ margin- ally in respect of the competence of mothers, Z2(2)= 5.12, P = 0.08, and significantly (Ps < 0.05) in competence of fathers, Z2(2) = 7.93, and older siblings, ~2(2) = 8.25. The compe- tence of younger siblings differed if anything in the opposite direction, and nonsignificantly, Z2(2) = 1.72, however there were very few younger siblings aged 3 yr or over. The result con-

Table 3. Water competence of parents and siblings of Sample 1, non-swimming children

Group: No Fear Losing Fear Current Fear (n = 12) (n = 12) (n = 9)

Mean (SD) water competence (1-3 scale) Mothers 2.8 (0.4) 2.2 (0.7) 2.7 (0.5) Fathers 2.9 (0.3) 2.9 (0.3) 2.2 (0.7) Older siblings 2.9 (0.2) 2.5 (0.7) 2.0 (0.0) Younger siblings 1.0 1.0 (0.8) 1.7 (0.6) Mean (SD) fear of water as child (1-3 scale) Mothers 2.0 (0.9) 2.1 (0.6) 1.6 (0.7) Fathers 1.5 (0.8) 1.5 (0.8) 2.2 (0.9)

Fear of water in chi ldren and adul ts 101

cerning older siblings is independent of the fact, mentioned above, that the No Fear group were more likely to have older siblings, because this analysis is confined to those children who did have at least one. Parents' fear as a child varied less consistently between groups, and not sig- nificantly [fathers X2(2) = 3.99, mothers X2(2) = 2.90].

Post hoc comparisons (Mann-Whitney U) showed that the Current Fear group were signifi- cantly worse than the No Fear group in competence of the father and older siblings. The Losing Fear group, although intermediate on most measures, were only marginally inferior to the No Fear group in mother's competence; indeed, they were significantly better than the Current Fear group in paternal competence. In the Losing Fear group it was the mothers who tended to be less water-competent, while in the Current Fear group it was the fathers. This pat- tern tends to confirm the suggestion, raised in the section on etiology, that the two fearful groups were qualitatively different.

The familial differences especially between Current Fear and No Fear groups are consistent with the reported genetic influence upon many fears and phobias (see Introduction), but could-- alternatively or additionally--reflect children's opportunity for vicarious learning from relatives who accompany them in the water. The next section attempts to dissociate the two factors.

Evidence for social learning from parents? All parents were asked how often they accompanied their children in the swimming pool. Inspection of the distribution of responses suggested a split into 3 ranges, 'Never', 'Occasionally' (1-5 times per year) and 'Regularly' (6 or more times per year). The fathers of the No Fear group were marginally more likely than fathers of the other groups to accompany their child regularly as opposed to occasionally or never, •2(2) = 4.80, P < 0.10, but the groups did not differ in how frequently their mothers accompanied them, Z2(2) = 1.17. This preliminary analysis, however, takes no account of how water-competent each parent was-- that is considered in more detail as follows.

Several patterns of parent-to-child social influence can be postulated. Relatively frequent con- tact with a highly competent parent might either protect a child from acquiring fear, or help it to lose preexisting fear; while relatively frequent contact with a parent whose competence or confidence is low might cause a child to become fearful, or prevent it from losing fear. We already know that the No Fear group are more likely to have competent parents than are the other 2 groups, so any tests of predictions concerning parental contact must control for parental competence. A possible prediction is that, given a highly competent parent, children in the No Fear group have more contact with him or her than do those in the Current Fear group. Conversely, given a parent of low competence, the No Fear group have less contact with him or her than do the Current Fear group. The Losing Fear group should present an intermediate pic-

Table 4. Parents ' wa te r competence and frequency of accompany ing child in pool: Sample 1, non- swimming chi ldren (omi t t ing parents who never accompanied child in pool)

Water competence: Poor or moderate Good Frequency: Occasional Regular Occasional Regular

1. Mothers Group:

No Fear 2 0 4 5 Losing Fear 4 2 4 1 Current Fear 2 1 5 1

2. Fathers Group:

No Fear 1 0 3 4 Losing Fear 1 0 7 1 Current Fear 2 1 3 0

3. Less competent (or only) parent Group:

No Fear 3 0 3 6 Losing Fear 4 2 5 0 Current Fear 3 2 2 0

4. More competent of 2 parents Group:

No Fear 0 0 4 4 Losing Fear 1 0 6 2 Current Fear 1 0 6 1

102 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

ture; contact with a poorly competent parent may engender fear, but contact with a highly com- petent parent may help to cure it.

Table 4 presents the distributions of parental water competence and frequency of contact in the pool, separately for each group. The first two sections refer to mothers and fathers. The fol- lowing sections illustrate a different categorization of parents into the less water-competent (or only) parent, and the more water-competent which, post hoc, proved informative. In 4 cases where 2 parents had equal competence but different contact frequency, the less competent parent was defined either as the only one who ever went in the pool with the child (2 cases) or at ran- dom. The parents in the 'less competent' section comprise 13 mothers and 5 fathers, plus 15 cases where mother and father scored identically. The 'more competent ' parents comprise all those not defined as 'less competent', i.e. the remaining parents from 2-parent families. The two ways of splitting the data are, of course, non-independent, as less competent parents are more likely to be mothers.

For the purpose of testing the above predictions, 2 mothers and 3 fathers who never ac- companied their child in the pool must be ignored. That is not to say they could not exert social influence elsewhere, but we cannot estimate its amount in the way we can with time in the pool, so any social influence of such a parent cannot be unconfounded from his or her genetic effect. Thus Table 4 includes only parents who occasionally or regularly accompanied their children. Very few of these fell into the Poor competence category, so only 2 competence bands are distin- guished, Poor/Moderate and Good.

Table 4 reflects the fact, already demonstrated, that the No Fear children were more likely to have competent parents than were the other two groups. To control for that effect, we looked at each competence level separately. Among parents of Poor/Moderate competence, there is no sign of a group difference; in all groups, such parents are more likely to join their children oc- casionally than regularly. However, among parents whose competence is Good, the No Fear group shows a distinctive pattern in that both mothers and fathers are more likely to accom- pany the child regularly, compared to the Losing Fear and Current Fear groups, very few of whose parents accompany them regularly. If data from the Losing Fear and Current Fear groups are combined for comparison with the No Fear group, the group difference in frequency is significant for fathers (Fisher's Exact, P -- 0.04) and nearly so for mothers (P = 0.09). It is similarly present if the parents are classified as the less or more competent in the family; the group difference is particularly clear among the less competent parents (P = 0.01). The similar pattern across, for example, mothers and fathers, is not simply a product of correlated beha- viour between parents of the same child; taking all cases where one parent regularly ac- companied the child, in fewer than half those cases did the other parent also accompany him or her regularly.

What do these results mean in terms of the hypotheses stated above? They offer no support for the idea that parents who themselves are fearful or incompetent, socially transmit fear to the child. The extent of contact with Poor/Moderate parents did not differ across groups (but of course, very few parents represented here were highly fearful). However, competent parents may enhance a child's confidence, or prevent it becoming fearful in the first place, because among children with highly competent parents, those whose parents accompanied them regularly were more likely to be in the No Fear group. On the other hand, there is no sign that competent parents can 'cure' fear, because the Losing Fear group did not have more regular contact with them than did the Current Fear group.

Unfortunately we have no information about the regularity of contact with siblings. It is note- worthy that it was only in the competence of older siblings that the Fear groups differed, con- sistent with the most likely direction of social influence. Genetic effects should be seen equally in older and younger siblings. However, the paucity of younger siblings prohibits a firm con- clusion.

Sample 2: adults

The adults were divided into two groups on the basis of their response to the FSS-III item 'Sight of deep water'. Thirty-eight people who reported 'a fair amount ' , 'much' or 'very much' fear of water comprised the High Fear group. Twenty-six of them were female and their mean

Fear of water in chi ldren and adul ts 103

age was 47 yr 3 months (range 26-67). The remaining 42 people who reported 'a little' or 'none at all' fear of deep water formed the Low Fear group. Twenty were female and their mean age was 46 yr 5 months (range 23-73). The groups did not differ significantly in gender ratio, ~(2(1) = 2.73, or age, t < 1.

Table 5 shows the distributions of responses by the two groups to the Adult Fear Origins Questionnaire. In the case of questions where there were missing or 'don't know' responses, the numbers of group members contributing (n) are shown. Chi-square values are given for items on which the pattern of response of the two groups differed at least marginally. Although the self-rated swimming ability of the groups differed, with Low Fear respondents being more likely to rate themselves as average or strong swimmers, the groups contained similar proportions of complete non-swimmers, meaning that their degree of lifetime exposure to water was not grossly different. There was evidence of consistency between current fear and reported fear as a child.

The next group of items show how many people reported the various types of lifetime experi- ences which had 'made them wary or cautious around water'. Unlike the children of Sample 1, whose mothers reported predominantly S-R experiences, both S-S and S-R were reported by the adults. All categories were somewhat more likely to be endorsed by the High Fear group, but the only individual category for which the trend approached significance was S-R condition- ing. However, the tendency of the High Fear group to report one or other of the types is con- firmed by the fact that the Low Fear group were significantly more likely to claim that they had n e v e r experienced any of them. But, like the data from the children of Sample 1, the responses of the fearful and non-fearful adults are more notable for their similarity than for their differ- ence.

The final section of Table 5 shows the reported swimming ability and water fear of first-degree relatives. The fear scores are drawn only from those respondents who provided data for every type of relative, so, to avoid further reduction through missing data (e.g. where respondents lacked one parent) we show the numbers who reported fear in either parent, any sibling etc. Parental swimming ability of the two groups was not very different but, again resembling the children, there were clear differences in relatives' fear, particularly parents'. Few described sib- lings as fearful, but the High Fear group were far more likely to describe parents as fearful, or to have at least one fearful relative.

The age range of the sample was wide, and it was possible that some effects came predomi- nantly from younger or older respondents. Such differences would hardly be expected if familial effects were genetic in origin, but might occur if they stemmed from social influence, as there have been secular changes in parents accompanying children to swimming pools. We therefore divided each group at the median age, which in both groups was 45 yr, and carried out loglinear

Table 5. Sample 2, adults: famil ial effects and aversive, experiences

Group: Low Fear High Fear X 2 (n = 42) (n - 38)

Self-rated swimming ability: 6.61, 2 df, P < 0.05 Non-swimmer (%) l 1 (26) 7 (22) Weak 20 28 Average or strong 11 3

Fear of water as a child (n): (34) (34) 7.90, 2 df, P < 0.05 None 9 3 Some 15 10 A lot 10 21

Aversive experiences (n): (40) (37) S-S conditioning (%) 14 (35) 15 (40) S-R conditioning (%) 13 (32) 19 (51) 2.81, 1 df, P < 0.10 Vicarious learning (%) 10 (25) 11 (30) Negative information (%) 12 (30) 14 (38) None of the above (%) 14 (35) 3 (8) 8.08, 1 df, P < 0.01

Parent who could swim: Father (%) 20/37 (54) 13/34 (38) Mother (%) 11/37 (30) 11/37 (30)

Relatives with fear of water (n): (36) (32) At least one parent (%) 16 (44) 25 (78) 8.03, 1 df, P < 0.01 At least one sibling (%) 4 (11) 8 (25) At least one child (%) 2 (5) 2 (6) No relative with fear (%) 17 (47) 5 (16) 7.73, 1 df, P < 0.01

104 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

analyses to test whether the variables which differentiated the Low and High Fear groups (Table 5)interacted with older vs younger age group. In no case did age have an influence. The variables themselves were similarly distributed over the age groups (largest X 2 = 1.57, 1 df, for presence of fearful sibling) and none of the significant effects of Fear group was moderated by age group (largest Z 2 = 1.03, 2 df, for fear of water as a child). Inspection of the remaining vari- ables, which did not differ overall between fear groups, revealed no sign of opposite patterns in the two age groups which might have been masked by combining them. The conclusions above, then, are consistent across a wide range of adult ages.

Relation of fear of water to other fears. The responses of all 80 adults to the first 76 items of the FSS-III (which make up the most widely used version) were subjected to a confirmatory principal-axis factor analysis, specifying 5 factors in accordance with Arrindell et al. (1984). Four of the 5 factors were clearly interpretable (from the pattern of primary loadings greater than 0.3) as Social fears, Medical/Injury fears, Small Animal fears and Agoraphobic fears. Also in agreement with earlier findings, 'Sight of deep water' did not load strongly on any factor, its highest loadings being on the Social factor (0.297) and Agoraphobia (0.202). Compared to chil- dren, then, adults' fear of water occupies a more unique position relative to other fears, consist- ent with its forming a separate factor in the FSS-II (Geer, 1965; see Introduction).

DISCUSSION

Our main findings can be summarised as follows.

(1) Within the sample of 5-8 yr old non-swimmers, it was useful to distinguish between chil- dren who were never fearful of water, either by our observation or by parental report (No Fear), those who were visibly fearful (Current Fear), and those whom parents described as having been fearful but who were not now observably so (Losing Fear). The latter group differed from each of the others in several respects, see below.

(2) There was little or no difference between currently-fearful groups (Current Fear children, High Fear adults) and their low-fear control groups (No Fear children, Low Fear adults) in terms of previous aversive experiences with water. Where differences were observed (e.g. the excess of S-R experiences reported by the High Fear adults) they were as plausi- bly a consequence of fear as a precursor. The majority of fearful children had, according to their mothers, shown fear of water from first contact with it. Therefore, we found no evidence that specific aversive experiences played a causal role in the onset of lasting fear.

(3) Mothers of children in the Losing Fear group were more likely to report that children had had conditioning or vicarious experiences, and to attribute their child's fear to those, than were mothers of Current Fear children, who were more likely to report that the child had always been fearful. Therefore, mothers' reports of experiences were associated with transient, not lasting fear.

(4) There were clear family resemblances in water fear, among child and adult samples. Children in the Current Fear and Losing Fear groups were more likely to have parents and older siblings whose water competence was poor (by parental report) than were the No Fear children. High Fear adults were more likely to report that their relatives, par- ticularly parents, had been fearful, than were Low Fear adults, a difference which was found across a wide age range.

(5) Familial influences could be genetic, social or both. Certain features of the data are con- sistent with social mediation. First, water-fearful children were more likely to be first- borns (and this was not simply a by-product of higher general fearfulness as assessed by the FSSC-R). Second, among children whose parents were highly water-competent, those whose parents frequently accompanied them in the water were most likely to be free of fear themselves. (However, the converse pattern was not found; among children whose parents were lower in competence, frequent contact did not have an adverse effect.) Third, the Current Fear and Losing Fear groups differed in which parent tended to be low in competence; in the Current Fear group it was the father, in the Losing Fear group, the mother. None of these observations rules out a genetic component, but they

Fear of water in children and adults 105

suggest, hardly surprisingly, that family members exert multiple influences. (6) The relationship of self-rated water fear to other fears differed between adults and chil-

dren. For the adults, it did not load strongly on any factor of the FSS-III, showing at most a marginal association with the Social Fear factor. Our sample of adults had elected to take swimming lessons, so their water fear might plausibly be linked to social perform- ance anxiety. For the children, it was associated with other fears within the Unknown and Danger clusters of the FSSC-R. Despite that similarity to the findings of Ollendick (1983), and a sex difference in overall fear which also agrees with previous research, the children's self-reported fear of deep water within the shortened FSSC-R lacked concur- rent validity; it did not reflect observed group differences in behavioral water avoidance.

We have presented the results at face value, but their validity needs to be critically considered. We relied on parental report for evidence of children's experiences, and the current water com- petence of themselves and other relatives; and on retrospective report by the adult sample, for similar purposes. The potential inaccuracies and biases in retrospective reports about temporally remote personal experiences have often been pointed out (see Introduction). Parental information might also be distorted. Although children's experiences with water were quite recent, their mothers might not have had good knowledge about events which had impact on the child. Correlations between parents' ratings of their own and relatives' water attitudes, and fear on the child's part, might have reflected their expectations, particularly in the Losing Fear group where the only basis for ascribing fear to the child was the mother's report. It was impractical for us to check parental information against independent evidence. Despite these objections, our con- clusions (2) and (4) above are strengthened by the similarity of the pattern of results across chil- dren and adults. The methodology used with the two samples was different; although each method carries potential biases, the biases are not necessarily of the same kind, so the conver- gence of results is important.

Furthermore, both conclusions echo many other studies in the literature. Those reviewed in the Introduction generally accord with our conclusion (2); when the experiences of people (particularly adults) who have specific fears or phobias are compared with those of non-fearful controls, there is relatively little difference, suggesting that specific aversive experiences were not of major importance in the genesis of fear. As noted under (3), we replicated Menzies and Clarke's (1993a) finding that parents often report children's fear to be present from earliest con- tact. We know that salient associative experiences do sometimes give rise to fear, from studies of sequelae of trauma such as Yule et al. (1990). From the data of the Losing Fear group, we speculated that associative learning might play a part, because their mothers were quite likely to report conditioning or vicarious learning. However, some caution is advisable. As remarked above, the only evidence that these children had been fearful was their mothers' report. Perhaps mothers who knew for sure that the child had had an aversive experience were prone to believe that she or he subsequently became fearful, or to overestimate the magnitude of fear thereafter. Even if such learning took place, it must have been transient, because the children were observa- bly no longer fearful.

The methods of our and similar studies may be inadequate to discover the role of experience in the origin of fear. Quite apart from problems of reporting bias, discussed above, Davey (1992) and Menzies and Clarke (1994) have argued that etiologically important experiences may not fit the criteria for any of Rachman's pathways. The case vignettes in Davey, De Jong and Tallis (1993a) and Menzies (in press) illustrate how individuals may attribute the onset of their phobia to an experience which, at the time, is non-threatening, but later gives rise to strong, ir- rational fear, through cognitive revaluation or some other cumulative process. To understand such processes, especially over the lifetime of adults, calls for more detailed and analytic methods. We still know very little about the 'natural history' of adult water fear (Menzies, in press).

Turning to conclusion (4), our finding of family resemblances in water competence is consist- ent with many studies reviewed in the Introduction. The obvious question arises whether the resemblances reflect inherited predispositions to develop a specific fear of water or (more plausi-

106 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

bly) the fear factor or trait to which water fear is linked--or alternatively, whether they reflect social learning or shared experience.

Our study yields some evidence for non-genetic familial effects, summarised under (5). The tendency for children with Current Fear to be firstborns (a pos t hoc finding which we unfortu- nately could not investigate in the adult sample) cannot be an artefact of informants' bias. Ear' studies of birth order suggested that firstborns showed stronger physiological stress responses than later-born children (Weiss, 1970) or that firstborns tended to react affiliatively and depen- dently in stressful situations (Schachter, 1959), implying that they would cope less confidently with a new and challenging environment such as deep water. Later research, which looked more critically at demographic factors, has not supported the idea that firstborns are generally prone to anxiety or dependency, but explains birth order effects in terms of the total family environ- ment--parents plus older and younger siblings--and the opportunity to acquire expertise in that context (Sutton-Smith, 1982; Zajonc & Markus, 1975). Although that approach certainly implicates social learning, the learning is cumulative and positive rather than episodic and aver- sive (as envisaged by traditional associative learning models). In respect of water fear, later-born children would have more opportunity to learn confidence or un-learn initial fear, via exposure to older siblings or more skilled parents. Our observation that the No Fear children benefited from regular contact with water-competent parents, and possibly older siblings, is consistent with this type of model. In theory, children could acquire fear through learning (episodic or gra- dual) from a nervous parent, but our data, while not ruling out that possibility, provide no explicit evidence in its favor. Finally, some of these associations may reflect reciprocal influences between parents and children; if a child is confident, that may encourage its parents to take it swimming.

The third finding which is, at first sight, inconsistent with genetic determination, is that the Current Fear group had relatively fearful fathers (not mothers)--the Losing Fear group, vice versa. Once again, the possibility arises that the Losing Fear group's data are artefactual. The mother was the informant, so the correlation between her own fear and the child's might reflect her expectations. If so, we must conclude that the Losing Fear group are actually similar to the No Fear group, in having non-fearful fathers, and there is a simple relationship between the child's observable current fear (which was low in both Losing Fear and No Fear groups) and the father's fear, but not the mother's.

This finding is hard to interpret, and goes the opposite way to an unpublished study reported by Menzies (in press). A genetic effect should stem equally from fathers and mothers. The weaker association with mothers' fear is unlikely to be a consequence of statistical range restric- t ion-Table 3 shows no gross differences in variability between fathers and mothers. Table 4 shows that, if anything, children were more likely to be accompanied to the swimming pool by their mothers, so fathers did not have an obviously greater opportunity to exert a social effect. One possible explanation, compatible with the results shown in Table 4, is that the actual range of frequency/intensity of contact with fathers was wider than the range of mothers' contact. Another analogous suggestion is that the self-rated bands of water fear and swimming ability in the Family Water Attitudes Questionnaire were scaled differently in respect of mothers and fathers--perhaps fathers' competence spans a wider range in practice than mothers'. Without independent rating of actual frequency, water attitudes etc., the issue cannot be resolved. Studies of parent-offspring similarity in other fears and phobias have also found quantitatively different effects, in both directions, of mothers' and fathers' attitudes (Davey et al., 1993b; Muris et al., 1996).

Our general conclusion from the familial effects is that there is evidence that social learning within the family can work against the development of water fear, but very little evidence for a primary causal role. Where positive correlations exist between children's fear and that of their relatives, there is as much reason to attribute them to the heritable propensity to develop fear of the Unknown and Danger (Stevenson et al., 1992) with which children's water fear is strongly correlated, as to specific vicarious learning experiences.

Our finding (6) implies that self-reported fear of water loses its link with those generic fear clusters over the course of adult life, and becomes relatively independent. This change might result from individually varying positive or negative experiences. Although we concluded above

Fear of water in children and adults 107

that specific negative experiences are relatively unimportant in the early origin of fear, we did not study the role of adult experience in any detail. If, as suggested by our data, fear of water in our adult sample had some connection with social or performance anxiety, its etiology may be different from that of children's fear. The idea that fears which form part of a generic cluster may develop differentially as a result of experience is analogous to the suggestion by Davey (1994) that fears of certain invertebrates (wasps and bees) lose their linkage to 'disgust sensi- tivity' because of individual aversive experiences.

Overall, our findings favor the view of Menzies and Clarke (1993a) that fear of water arises with no or minimal learning, perhaps enhanced by a heritable propensity towards fears in the Unknown and Danger categories. The role of children's experience is usually to prevent or diminish the strength of fear, rather than to instigate it.

R E F E R E N C E S

Arrindell, W. A., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & van der Ende, J. (1984). Phobic dimensions: I. Reliability and generalizabil- ity across samples, gender and nations. The Fear Survey Schedule (FSS-III) and the Fear Questionnaire (FQ). Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 6, 207-254.

Arrindell, W. A., Pickersgill, M. J., Merckelbach, H., Ardon, A. M., & Cornet, F. C. (1991). Phobic dimensions: III. Factor analytic approaches to the study of common phobic fears: An updated review of findings obtained with adult subjects. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy, 13, 73-130.

Barlow, D. H. (1988). Anxiety and its disorders. New York: Guilford Press. Bernstein, D. A., & Allen, G. J. (1969). Fear Survey Schedule (II): Normative data and factor analyses based on a large

college sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 7, 403-407. Clarke, J. C., & Jackson, J. A. (1983). Hypnosis and behavior therapy: The treatment of anxiety and phobias. Berlin:

Springer. Cook, M., & Mineka, S. (1991). Selective associations in the origins of phobic fears and their implications for behavior

therapy. In P. Martin (Ed.), Handbook of behaviour therapy and psychological science (pp. 413-434). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Darwin, C. (1877). A biographical sketch of an infant. Mind, 2, 285-294. Davey, G. C. L. (1989). Dental phobias and anxieties: Evidence for conditioning processes in the acquisition and modu-

lation of a learned fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 51-58. Davey, G. C. L. (1992). Classical conditioning and the acquisition of human fears and phobias: A review and synthesis

of the literature. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 14, 29-66. Davey, G. C. L. (1994). Self-reported fears to common indigenous animals in an adult UK population: The role of dis-

gust sensitivity. British Journal of Psychology, 85, 541-554. Davey, G. C. L., De Jong, P. J., & Tallis, F. (1993a). UCS inflation in the aetiology of a variety of anxiety disorders:

Some case studies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31,495-498. Davey, G. C. L., Forster, L., & Mayhew, G. (1993b). Family resemblances in disgust sensitivity and animal phobias.

Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 41-50. de Jongh, A., Muris, P., ter Hurst, G., & Duyx, M. P. M. A. (1995). Acquisition and maintenance of dental anxiety:

The role of conditioning experiences and cognitive factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 33, 205-210. Di Nardo, P. A., Guzy, L. T., Jenkins, J. A., Bak, R. M., Tomasi, S. F., & Copland, M. (1988). Etiology and mainten-

ance of dog fears. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 26, 241-244. Doogan, S., & Thomas, G. V. (1992). Origins of fear of dogs in adults and children: The role of conditioning processes

and prior familiarity with dogs. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 30, 387-394. Fonseca, A. C., Yule, W., & Erol, N. (1994). Cross-cultural issues. In T. H. Ollendick, N. J. King & W. Yule (Eds.),

International handbook of phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum Press. Fyer, A. J., Mannuzza, S., Chapman, T. R, Martin, L. Y., & Klein, D. F. (1995). Specificity in familial aggregation of

phobic disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 564-573. Fyer, A. J., Mannuzza, S., Gallops, M. S., Martin, L. Y., Aaronson, C., Gorman, J. M., Liebowitz, M. R., & Klein, D.

F. (1990). Familial transmission of simple phobias and fears. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 252-256. Geer, J, H. (1965). The development of a scale to measure fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 3, 45-53. Gray, J. A. ( 1971). The psychology of fear and stress, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson. Hofmann, S. G., Ehlers, A., & Roth, W. T. (1995). Conditioning theory: A model for the etiology of public speaking

anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 567-571. Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Kessler, R. C., Heath, A. C., & Eaves, L. J. (1992). The genetic epidemiology of phobias

in women: The interrelationship of agoraphobia, social phobia, situational phobia in simple phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 273-281.

Marks, I. M. (1987). Fears, phobias and rituals: Panic, anxiety and their disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press. McNally, R. J., & Steketee, G. S. (1985). The etiology and maintenance of severe animal phobias. Behaviour Research

and Therapy, 23, 431--435. Menzies, R. G. (in press). Water phobia. In G. C. L. Davey (Ed.), Phobias." A handbook of theory, research and treat-

ment. Chichester: Wiley. Menzies, R. G.. & Clarke, J. C. (1993a). The etiology of childhood water phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31,

499-501. Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1993b). The etiology of fear of heights and its relationship to severity and individual re-

sponse patterns. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 355-365.

108 Jacqueline Graham and E. A. Gaffan

Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1994). Retrospective studies of the origins of phobias: A review. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 7, 305-318.

Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1995a). The etiology of acrophobia and its relationship to severity and individual re- sponse patterns. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 795-803.

Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1995b). The etiology of phobias: A nonassociative account. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 23-48.

Milgrom, P., Mancl, L., King, B., & Weinstein, P. (1995). Origins of childhood dental fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 313-319.

Muris, P., Steememan, P., Merckelbach, H., & Meesters, C. (1996). The role of parental fearfulness and modeling in chil- dren's fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 265-268.

Ohman, A., Dimberg, U., & Ost, L. -G. (1985). Animal and social phobia: Biological constraints on learned fear re- sponses. In S. Reiss & R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy (pp. 123-175). New York: Academic Press.

Ollendick, T. H. (1983). Reliability and validity of the Revised Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSSC-R). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21,685-692.

Ollendick, T. H., & King, N. J. (1991). Origins of childhood fears: An evaluation of Rachman's theory of fear acqui- sition. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 117-123.

Ollendick, T. H., King, N. J., & Frary, R. B. (1989). Fears in children and adolescents: Reliability and generalizability across gender, age and nationality. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 19-26.

Ost, L. -G. (1991). Acquisition of blood and injection phobia and anxiety response patterns in clinical patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 323-332.

Ost, L. -G., & Hugdahl, K. (1981). Acquisition of phobias and anxiety response patterns in clinical patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 19, 439-447.

Ost, L. -G., & Hugdahl, K. (1983). Acquisition of agoraphobia, mode of onset and anxiety response patterns. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21,623-631.