FC 172-193

-

Upload

alfred-lacandula -

Category

Documents

-

view

9 -

download

0

description

Transcript of FC 172-193

Chapter 2.

Proof of Filiation

Art. 172. The filiation of legitimate children is established by any of the following: (1) The record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment; or (2) An admission of legitimate filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.In the absence of the foregoing evidence, the legitimate filiation shall be proved by: (1) The open and continuous possession of the status of a legitimate child; or (2) Any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws. (265a, 266a, 267a)Proofs of filiation: 1. Primary evidence:a. Record of birth;b. Admission in a public document or in a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.2. Secondary evidence:a. Proof of continuous open possession of the status of a legitimate child;b. Any other evidence admissible under the Rules of Court or the law. NOTE: SECONDARY EVIDENCE IS NOT ADMISSIBLE IF THE PRIMARY EVIDENCE EXISTS. Record of birth the books making up the civil register and all documents relating thereto shall be considered public documents and shall be prima facie evidence of the truths of the facts therein contained. BUT, if the alleged father did not intervene in the making of the birth certificate, the putting of his name by the mother or doctor or registrar is void; signature of the alleged father is necessary. Admission in writing A parent may admit legitimate filiation in a document duly acknowledged before a notary public, with the proper formalities, so as to become public and be admissible in suits; or also in a private handwritten document signed by the parent concerned. (e.g. notarial will, holographic will {a will entirely handwritten, dated and signed by the testator -the person making the will- but not signed by required witnesses}, a letter to a person in which the alleged father admitted that this is his child and signed). Possession of status this is the concurrence of facts which indicate the relation of filiation between an individual and the family to which he claims to belong. The possession of status must be of some long duration as may be implied from the word continuous. Of these facts, the most important are: a. That the individual has always borne the surname of the supposed father (nomen - name);b. That the father has treated him as his legitimate child, and in such capacity has attended to his education, maintenance and future (tractatus treatment);c. That the individual has been constantly recognized as such child in society and by the family (fama fame); NOTE: All those enumerated above (a, b & c) must be present. Any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws- may include the childs baptismal certificate, a judicial admission, the family bible wherein the name of the child is entered, common reputation respecting pedigree, admission by silence, testimonies of witnesses, and other kinds of proof admissible under Rule 130 of the Revised Rules of Court. Baptismal certificate The baptismal certificate is not proof of filiation. It only proves the fact of the administration of the sacrament or the act of baptism on the day specified. But it is not proof of the veracity of the statements made therein regarding he relatives or parents of the person baptized. Although allowed by the Rules of Court, it has scant proof of filiation. It is only proof to the sacrament of baptism but not the proof of filiation of the child.Fernandez vS. COURT OF APPEALS230 SCRA 130FACTS:Violeta Esguerra, single, mother and guardian ad litem of petitioners Claro Antonio Fernandez and John Paul Fernandez, pointed to respondent Carlito S. Fernandez as the father of the petitioners. She claimed that she and Carlito started their illicit sexual relationship six months after their first meeting sometime in 1983. The tryst resulted in the birth of petitioners Claro on 1984 and John Paul on 1985. Violeta averred that they were married in civil rights in October 1983. She further claimed that she did not know that Carlito was married until the birth of her two children. In March 1985, however, she discovered that the marriage license which they used was spurious.

Petitioners presented the following documentary evidence: certificates of live birth, identifying respondent as their father, the baptismal certificate of Claro which also states that his father is respondent, photographs of respondent taken during the baptism of Claro; and pictures of respondent and Claro taken at the home of Violeta Esguerra. Petitioners likewise presented witnesses Cantoria and Dr. Villanueva and Cu who told the trial court that Violeta Esguerra had, at different times, introduced the respondent to them as her husband; and Fr. Fernandez who testified that Carlito was the one who presented himself as the father of petitioner Claro during the latters baptism.

Carlito denied Violetas allegations and averred that he only served as sponsor in the baptism of Claro. Such claim was corroborated by the testimony of Pagtakhan, an officemate who also stood as sponsor to the said baptism.

The trial court ruled in favor of the petitioners. The CA reversed the decision of the trial court.

ISSUE:Whether or not the documentary evidence offered by the petitioners was insufficient to prove their filiations

HELD:No, they were insufficient. First, petitioners cannot rely on the photographs showing the presence of the private respondent in the baptism of the petitioner. These photographs are far from proofs that private respondent is the father of petitioner Claro. As explained, he was merely a sponsor to the baptism. Second, the pictures taken in the house of Violeta showing respondent showering affection to Claro fall short of the evidence required to prove paternity. Third, the baptismal certificate of petitioner Claro naming respondent as his father has scant evidentiary value because there is no showing that private respondent participated in its preparation. Fourth, the certificates of live birth of the petitioners identifying respondent as their father are not also competent evidence on the issue of paternity because, again, the records do not show that private respondent had a hand in the preparation thereof.

The petition is dismissed and the decision of CA is affirmed.

FERNANDEZ VS. FERNANDEZ363 SCRA 811FACTS:Spouses Dr. Jose Fernandez and Generosa de Venecia were childless. So they purchased from a certain Miliang a baby boy they named as Rodolfo Fernandez. Jose died in 1982, leaving his wife and Rodolfo an estate consisting of a parcel of land and 2 storey residential building. In 1989, Generosa and Rodolfo executed a deed of extra-judicial partition dividing and allocating to themselves properties of the estate. On the same day, Generosa executed a deed of absolute sale in favor of Eddie Fernandez, Rodolfos son, over the land and the residential building which was allocated to her. After learning the transaction, the nephews and nieces of the deceased Jose Fernandez filed an action to declare the extra-judicial partition of estate and deed of sale void ab initio. They alleged that Rodolfo and Eddie took advantage of the total physical and mental incapacity of Generosa, and that Rodolfo is not the son of the spouses. Meanwhile, Rodolfo presented his baptismal certificate and an application for recognition of backpay rights by Jose.

The RTC declared the deeds null and void. In so ruling, the trial court found that Rodolfo was not a legitimate or a legally adopted child of the spouses Fernandez. The CA affirmed the trial courts judgment.

ISSUE:Whether or not Rodolfos baptismal certificate is admissible as proof of filiation

HELD:While ones legitimacy can be questioned only in a direct action, this doctrine has no application in the instant case considering that respondents claim was that petitioner Rodolfo was not born to the spouses Fernandez. It is not a situation wherein they deny that Rodolfo was a child of their uncles wife.

Petitioner Rodolfo failed to prove his filiation with the deceased spouses Fernandez. While baptismal certificates may be considered public documents, they are evidence only to prove the administration of the sacraments on the dates therein specified, but not the veracity of the statements or declarations made therein with respect to his kinsfolk. Neither the family portrait offered in evidence establishes a sufficient proof of filiation. Pictures do not constitute proof of filiation.

As to the application for recognition of backpay, the public document contemplated in Art. 172 of the FC refer to the written admission of filiation embodied in a pubic document purposely executed as an admission of filiation and not as obtaining in this case wherein the public document was executed as an application for the recognition of rights to backpay.

Petitioner Rodolfo is not a child by nature of the spouses Fernandez and not a legal heir of Dr. Jose Fernandez, thus the subject deed of extra-judicial settlement of the estate of Dr. Jose Fernandez between Generosa and Rodolfo is null and void insofar as Rodolfo is concerned.

LABAGALA VS. SANTIAGO371 SCRA 360FACTS:Jose Santiago owned a parcel of land in Manila. Alleging that Jose had fraudulently registered it in his name alone, his sisters (now respondents herein) sued Jose for recovery of 2/3 share of the property. When Jose died intestate, respondents filed a complaint for recovery of title, ownership, and possession against herein petitioner, Ida Labagala to recover from her 1/3 portion of said property pertaining to Jose but which came into petitioners sole possession upon Joses death.Respondents alleged that Joses share in the property belongs to them by operation of law, because they are the only legal heirs of their brother, who died intestate and without issue. They claimed that the deed of sale of the property executed by their brother to petitioner is a forgery.Petitioner claimed that her true name is not Ida Labagala but Ida Santiago. She claimed to be the daughter of Jose and thus entitled to his share in the subject property. She argued that the purported sale was in fact a donation to her.The trial court ruled in favor of petitioner. The CA reversed the decision of the trial court. The appellate court noted that the birth certificate of Ida Labagala presented by respondents showed that Ida was born of different parents, not Jose and his wife.ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner has adduced preponderant evidence to prove that she is the daughter of the late Jose Santiago

HELD:Art. 263 of the CC refers to an action to impugn the legitimacy of a child, to assert and prove that a person is not a mans child by his wife. However, the present case is not one impugning petitioners legitimacy. Respondents are asserting not merely that petitioner is not a legitimate child of Jose, but that she is not a child of Jose at all. Moreover, the present action is one for recovery of title and possession, and thus outside the scope of Article 263 on prescriptive periods.

The certificate of record of birth plainly states that Ida was the child of the spouses Leon Labagala and Cornelia Cabrigas. Therefore, this certificate is proof of the filiation of Ida. If he birth certificate presented in evidence is not hers, then where is hers? She did not present any though it would have been the easiest thing to do considering that according to her baptismal certificate she was born in Manila in 1969. But then, a baptismal certificate is not a proof of the parentage of the baptized person. This document can only prove the identity of the baptized, the date and place of her baptism, the identities of the baptismal sponsors and the priest who administered the sacrament, nothing more.

Further, petitioner, who claims to be Ida Santiago, has the same birthdate as Ida Labagala. The similarity is too uncanny to be a mere coincidence. Not being a child of Jose, it follows that petitioner can not inherit from him through intestate succession. Clearly, there is no valid sale in this case; Jose did not have the right to transfer ownership of the entire property to petitioner since 2/3 thereof belonged to his sisters. Neither may the purported deed of sale be a valid deed of donation.

LOCSIN vS. LocsinG.R. No. 146737 December 10, 2001FATCS:Juan Locsin, Jr., herein respondent, filed with the RTC a petition praying that he be appointed administrator of the intestate estate of the deceased Juan Locsin, Sr. He alleged that he is an acknowledged natural child of the deceased and that he is the only surviving legal heir of the decedent. The heirs of Juan Locsin, Sr., herein petitioners, filed an opposition averring that respondent is neither a child nor an acknowledged natural child of the former.

To support his claim, respondent submitted a machine copy of his certificate of live birth found in the bound volume of birth records in the office of the Local Civil Registrar. To prove its existence and authenticity, he presented the Local Civil Registrar as witness. He also offered in evidence a photograph showing him and his mother in front of a coffin bearing Juan Locsins dead body. Respondent claims that the photograph shows that he and his mother have been recognized as family members of the deceased.

In their oppositions, petitioners claimed that the certificate of live birth is spurious. They submitted a certified true copy of the certificate of live birth found in the Civil Registrar General, Metro Manila, indicating that the birth of respondent was reported by his mother and that the same does not contain the signature of the late Juan Locsin.

The trial court found the certificate of live birth and the photograph sufficient proofs of respondents illegitimate filiation. The CA affirmed the order of the trial court.

ISSUE:Which of the two documents, the certificate of live birth from the local civil registrar or certificate of live birth from the civil registrar general, is genuine?

HELD:The due recognition of an illegitimate child in a record of birth, a will, a statement before a court of record, or in any authentic writing is, in itself a consummated act of acknowledgment of the child, and no further court action is required. In fact, any authentic writing is treated not just a ground for compulsory recognition, it is in itself a voluntary recognition that does not require a separate action for judicial approval.

A birth certificate is a formidable piece of evidence prescribed by both the CC and the Art 172, FC, for purposes of recognition and filiation. However, birth certificate offers only prima facie evidence of filiation and may be refuted by contrary evidence. Its evidentiary worth cannot be sustained where there exists strong, complete and conclusive proof of its falsity or nullity. In this case, respondents Certificate of Live Birth entered in the records of the Local Civil Registry has all the badges of nullity. Without doubt, the authentic copy on file in that office was removed and substituted with a falsified Certificate of Live Birth. Where the glaring discrepancies between the Certificates of Live Birth recorded in the Local Civil Registry and the copy transmitted to the Civil Registry General, the latter prevails. What is authentic is the certificate of live birth recorded in the Civil Registry General.A persons photograph with his mother near the coffin of the alleged father cannot and will not constitute proof of filiation, lest that would encourage and sanction fraudulent claims. Anybody can have a picture taken while standing before a coffin with others and thereafter utilize it in claiming the estate of the deceased.

Bernabe vS. Alejo374 SCRA 181FACTS:The late Fiscal Bernabe allegedly fathered a son named Adrian Bernabe on September 18, 1981 with his secretary Carolina Alejo. Fiscal Bernabe died on August 13, 1993, while his wife Rosalina died on December 3 of the same year, leaving Ernestina as the sole surviving heir. On May 16, 1994, Carolina, in behalf of Adrian filed a complaint praying that Adrian be declared acknowledged illegitimate son of Fiscal Bernabe and be given his share of the deceaseds estate, which is being held by Ernestina. The RTC dismissed the complaint. Citing Article 175 of the Family Code, the RTC held that the death of the putative father had barred the action and that since the putative father had not acknowledged or recognized Adrian in writing, the action for recognition should have been filed during the lifetime of the alleged father to give him opportunity to either affirm or deny the childs filiation. The CA reversed the RTC's decision.ISSUE:Whether or not the respondent is barred from filing an action for recognition

HELD:The SC does not agree with the contention that the respondent is barred from filing an action, that Article 285 of the Civil Code has been supplanted by the provisions of the FC. The 2 exceptions provided under Art. 285 have however been omitted by Arts 172, 173 and 175 of the Family Code. Under the new law, an action for the recognition of an illegitimate child must be brought within the lifetime of the alleged parent. The FC makes no distinction on whether the former was still a minor when the latter died. Nonetheless, the FC provides the caveat that rights that have already vested prior to this enactment should not be prejudiced or impaired (Art 255). Art. 285 is a substantive law, as it gives Adrian the right to file his petition for recognition within four years from attaining majority. Therefore, the FC cannot impair or take Adrians right to file an action for recognition, because that right had already vested prior to its enactment.

Petition is denied.

DELA ROSA, et al. VS. VDA DE DAMIAN January 27, 2006FACTS:One of those claiming the estate of the late spouses Rustia is Guillerma Rustia who claimed to be the illegitimate child of Guillerma Rustia where she sought recognition on 2 grounds: first, compulsory recognition through the open and continuous possession of the status of an illegitimate child and second, voluntary recognition through authentic writing. As proof of the latter, she presented the report card that identified Guillermo Rustia, named Guillerma as one of their children.

ISSUE:Whether or not Guillerma can still claim compulsory acknowledgement from Guillermo RustiaHELD:There was apparently no doubt that she possessed the status of an illegitimate child from her birth until the death of her putative father Guillermo Rustia. However, this did not constitute acknowledgement but a mere ground by which she could have compelled acknowledgment through the courts. Furthermore, any (judicial) action for compulsory acknowledgment has dual limitation: the lifetime of the child and the lifetime of the putative parent. On the death of either, the action for compulsory can no loner be filed. In this case, Guillermas right to claim compulsory acknowledgement prescribed upon the death of Guillermo Rustia on February 28, 1974.The claim of voluntary recognition must likewise fail. An authentic writing for purposes of voluntary recognition is understood as a genuine or indubitable writing of the parent. This includes a public instrument or a private writing admitted by the father to be his. Did Guillermas report card from the University of Sto. Tomas and Josefa Delgados obituary prepared by Guillermo qualify as authentic writings under the Civil Code? Unfortunately, it did not. The report card did not bear the signature of Guillermo Rustia. The fact that his name appears there, as her parent/guardian holds no weight since he had no participation in its preparation. Similarly, while witnesses testified that it was Guillermo himself who drafted the notice of death of Josefa which was published in the Sunday Times on September 2, 1972, that published obituary was not the authentic writing contemplated by law. What could have been admitted as an authentic writing was the original manuscript of the notice, in the handwriting of Guillermo himself and signed by him, not the newspaper clipping of the obituary. The failure to present the original signed manuscript was fatal to Guillermos claim.

VERCELES VS. POSADA522 SCRA 518FACTS: Respondent Maria Clarissa Posada, young lass from the barrio of Pandan, Catanduanes, sometime in 1986 met a close family friend, petitioner Teofisto I. Verceles, mayor of Pandan. He then called on the Posadas and at the end of the visit, offered Clarissa a job. Clarissa accepted petitioners offer and worked as a casual employee in the mayors office starting on September 1, 1986. From November 10 to 15 in 1986, with other companions, she accompanied petitioner to Legaspi City to attend a seminar on town planning.

On November 11, 1986, Clarissa was told by petitioner that they would have lunch at Mayon Hotel with their companions who had gone ahead. When they reached the place her companions were nowhere. After petitioner ordered food, he started making amorous advances on her. She panicked, ran and closeted herself inside a comfort room where she stayed until someone knocked. Afraid of the mayor, she kept the incident to herself. She went on as casual employee. One of her tasks was following-up barangay road and maintenance projects.

On December 22, 1986, on orders of petitioner, she went to Virac, Catanduanes, to follow up funds for barangay projects. She went to Catanduanes Hotel on instructions of petitioner who asked to be briefed on the progress of her mission. They met at the lobby and he led her upstairs because he said he wanted the briefing done at the restaurant at the upper floor. Instead, however, petitioner opened a hotel room door, led her in, and suddenly embraced her, as he told her that he was unhappy with his wife and would "divorce" her anytime. He also claimed he could appoint her as a municipal development coordinator. She succumbed to his advances. But again she kept the incident to herself.

Sometime in January 1987, when she missed her menstruation, she said she wrote petitioner that she feared she was pregnant. In another letter in February 1987, she told him she was pregnant. Petitioner replied in a handwritten letter:

My darling Chris,

Should you become pregnant even unexpectedly, I should have no regret, because I love you and you love me.Let us rejoice a common responsibility you and I shall take care of it and let him/her see the light of this beautiful world.We know what to do to protect our honor and integrity.Just relax and be happy, if true.With all my love,

Ninoy

2/4/87

Clarissa explained petitioner used an alias "Ninoy" and addressed her as "Chris," probably because of their twenty-five (25)-year age gap. In court, she identified petitioners penmanship which she claims she was familiar with as an employee in his office. Clarissa presented three other handwritten letters sent to her by petitioner, two of which were in his letterhead as mayor of Pandan. She also presented the pictures petitioner gave her of his youth and as a public servant, all bearing his handwritten notations at the back. On September 23, 1987, she gave birth to a baby girl, Verna Aiza Posada.

Clarissas mother, Francisca, felt betrayed by petitioner and shamed by her daughters pregnancy. The Posadas filed a Complaint for Damages coupled with Support Pendente Lite against petitioner. The trial court issued a judgment in favor of respondents. CA affirms.

ISSUE: Whether or not Verna Aiza Posada was an illegitimate child of the petitioner

HELD: Yes. A perusal of the Complaint shows that although its caption states "Damages coupled with Support Pendente Lite," Clarissas averments therein all clearly establish a case for recognition of paternity. The due recognition of an illegitimate child in a record of birth, a will, a statement before a court of record, or in any authentic writing is, in itself, a consummated act of acknowledgement of the child, and no further court action is required. In fact, any authentic writing is treated not just a ground for compulsory recognition; it is in itself a voluntary recognition that does not require a separate action for judicial approval.

The letters of petitioner are declarations that lead nowhere but to the conclusion that he sired Verna Aiza. Although petitioner used an alias in these letters, the similarity of the penmanship in these letters vis the annotation at the back of petitioners fading photograph as a youth is unmistakable. Even an inexperienced eye will come to the conclusion that they were all written by one and the same person, petitioner, as found by the courts a quo.

Art. 172. The filiation of legitimate children is established by any of the following:

(1) The record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment; or(2) An admission of legitimate filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.

In the absence of the foregoing evidence, the legitimate filiation shall be proved by:

(1) The open and continuous possession of the status of a legitimate child; or(2) Any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws.

Art. 175. Illegitimate children may establish their illegitimate filiation in the same way and on the same evidence as legitimate children.

The action must be brought within the same period specified in Article 173, except when the action is based on the second paragraph of Article 172, in which case the action may be brought during the lifetime of the alleged parent.

The letters are private handwritten instruments of petitioner which establish Verna Aizas filiation under Article 172 (2) of the Family Code. In addition, the array of evidence presented by respondents, the dates, letters, pictures and testimonies, to us, are convincing, and irrefutable evidence that Verna Aiza is, indeed, petitioners illegitimate child.

DELA CRUZ VS. GRACIA594 SCRA 648FACTS: For several months in 2005, then 21-year old petitioner Jenie San Juan Dela Cruz and then 19-year old Christian Dominique Sto. Tomas Aquino lived together as husband and wife without the benefit of marriage. They resided in the house of Dominiques parents. On September 4, 2005, Dominique died. After almost two months, Jenie, who continued to live with Dominiques parents, gave birth to her herein co-petitioner minor child Christian Dela Cruz Aquino.

Jenie applied for registration of the childs birth, using Dominiques surname Aquino, with the Office of the City Civil Registrar in support of which she submitted the childs Certificate of Live Birth, Affidavit to Use the Surname of the Father (AUSF) which she had executed and signed, and Affidavit of Acknowledgment executed by Dominiques father Domingo Butch Aquino. Both affidavits attested, inter alia, that during the lifetime of Dominique, he had continuously acknowledged his yet unborn child, and that his paternity had never been questioned. Jenie attached to the AUSF a document entitled AUTOBIOGRAPHY which Dominique, during his lifetime, wrote in his own handwriting, the pertinent portions of which read:

AQUINO, CHRISTIAN DOMINIQUE S.T.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

IM CHRISTIAN DOMINIQUE STO. TOMAS AQUINO, 19 YEARS OF AGE TURNING 20 THIS COMING OCTOBER 31, 2005.[5] I RESIDE AT PULANG-LUPA STREET BRGY. DULUMBAYAN, TERESA, RIZAL. I AM THE YOUNGEST IN OUR FAMILY. I HAVE ONE BROTHER NAMED JOSEPH BUTCH STO. TOMAS AQUINO. MY FATHERS NAME IS DOMINGO BUTCH AQUINO AND MY MOTHERS NAME IS RAQUEL STO. TOMAS AQUINO. x x x.

x x x x

AS OF NOW I HAVE MY WIFE NAMED JENIE DELA CRUZ. WE MET EACH OTHER IN OUR HOMETOWN, TEREZA RIZAL. AT FIRST WE BECAME GOOD FRIENDS, THEN WE FELL IN LOVE WITH EACH OTHER, THEN WE BECAME GOOD COUPLES. AND AS OF NOW SHE IS PREGNANT AND FOR THAT WE LIVE TOGETHER IN OUR HOUSE NOW. THATS ALL.

The City Civil Registrar, respondent Ronald Paul S. Gracia, denied Jenies application for registration of the childs name. Rule 7 of Administrative Order No. 1, Series of 2004 (Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 9255 [An Act Allowing Illegitimate Children to Use the Surname of their Father, Amending for the Purpose, Article 176 of Executive Order No. 209, otherwise Known as the Family Code of the Philippines]) provides that:

Rule 7. Requirements for the Child to Use the Surname of the Father

7.1 For Births Not Yet Registered

7.1.1 The illegitimate child shall use the surname of the father if a public document is executed by the father, either at the back of the Certificate of Live Birth or in a separate document.

7.1.2 If admission of paternity is made through a private handwritten instrument, the child shall use the surname of the father, provided the registration is supported by the following documents:

a. AUSFb. Consent of the child, if 18 years old and over at the time of the filing of the document.c. Any two of the following documents showing clearly the paternity between the father and the child: 1. Employment records2. SSS/GSIS records3. Insurance4. Certification of membership in any organization5. Statement of Assets and Liability 6. Income Tax Return (ITR) In summary, the child cannot use the surname of his father because he was born out of wedlock and the father unfortunately died prior to his birth and has no more capacity to acknowledge his paternity to the child (either through the back of Municipal Form No. 102 Affidavit of Acknowledgment/Admission of Paternity or the Authority to Use the Surname of the Father).

Jenie and the child promptly filed a complaint for injunction/registration of name against respondent. The complaint alleged that the denial of registration of the childs name is a violation of his right to use the surname of his deceased father under Article 176 of the Family Code, as amended by Republic Act (R.A.) No. 9255, which provides:

Article 176. Illegitimate children shall use the surname and shall be under the parental authority of their mother, and shall be entitled to support in conformity with this Code. However, illegitimate children may use the surname of their father if their filiation has been expressly recognized by the father through the record of birth appearing in the civil register, or when an admission in a public document or private handwritten instrument is made by the father. Provided, the father has the right to institute an action before the regular courts to prove non-filiation during his lifetime. The legitime of each illegitimate child shall consist of one-half of the legitime of a legitimate child.

They maintained that the Autobiography executed by Dominique constitutes an admission of paternity in a private handwritten instrument within the contemplation of the above-quoted provision of law. The trial court dismissed the complaint for lack of cause of action as the Autobiography was unsigned, citing paragraph 2.2, Rule 2 (Definition of Terms) of Administrative Order (A.O.) No. 1, Series of 2004 (the Rules and Regulations Governing the Implementation of R.A. 9255) which defines private handwritten document through which a father may acknowledge an illegitimate child as follows: "2.2 Private handwritten instrument an instrument executed in the handwriting of the father and duly signed by him where he expressly recognizes paternity to the child." The trial court held that even if Dominique was the author of the handwritten Autobiography, the same does not contain any express recognition of paternity.

ISSUE: Whether or not the unsigned handwritten statement of the deceased father of minor Chrisitan Dela Cruz can be considered as a recognition of paternity in a "private, handwritten instrument" within the contemplation of Article 176 of the Family Code, as amended by R.A. 9255, which entitles the said minor to use his father's surname

HELD: Petitioners contend that Article 176 of the Family Code, as amended, does not expressly require that the private handwritten instrument containing the putative fathers admission of paternity must be signed by him. They add that the deceaseds handwritten Autobiography, though unsigned by him, is sufficient, for the requirement in the above-quoted paragraph 2.2 of the Administrative Order that the admission/recognition must be duly signed by the father is void as it unduly expanded the earlier-quoted provision of Article 176 of the Family Code.

Article 176 of the Family Code, as amended by R.A. 9255, permits an illegitimate child to use the surname of his/her father if the latter had expressly recognized him/her as his offspring through the record of birth appearing in the civil register, or through an admission made in a public or private handwritten instrument. The recognition made in any of these documents is, in itself, a consummated act of acknowledgment of the childs paternity; hence, no separate action for judicial approval is necessary.

Article 176 of the Family Code, as amended, does not, indeed, explicitly state that the private handwritten instrument acknowledging the childs paternity must be signed by the putative father. This provision must, however, be read in conjunction with related provisions of the Family Code which require that recognition by the father must bear his signature, thus:

Art. 175. Illegitimate children may establish their illegitimate filiation in the same way and on the same evidence as legitimate children.

Art. 172. The filiation of legitimate children is established by any of the following:(1) The record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment; or(2) An admission of legitimate filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.

That a father who acknowledges paternity of a child through a written instrument must affix his signature thereon is clearly implied in Article 176 of the Family Code. Paragraph 2.2, Rule 2 of A.O. No. 1, Series of 2004, merely articulated such requirement; it did not unduly expand the import of Article 176 as claimed by petitioners. In the present case, however, special circumstances exist to hold that Dominiques Autobiography, though unsigned by him, substantially satisfies the requirement of the law.

First, Dominique died about two months prior to the childs birth. Second, the relevant matters in the Autobiography, unquestionably handwritten by Dominique, correspond to the facts culled from the testimonial evidence Jenie proffered. Third, Jenies testimony is corroborated by the Affidavit of Acknowledgment of Dominiques father Domingo Aquino and testimony of his brother Joseph Butch Aquino whose hereditary rights could be affected by the registration of the questioned recognition of the child. These circumstances indicating Dominiques paternity of the child give life to his statements in his Autobiography that JENIE DELA CRUZ is MY WIFE as WE FELL IN LOVE WITH EACH OTHER and NOW SHE IS PREGNANT AND FOR THAT WE LIVE TOGETHER.

In the case at bar, there is no dispute that the earlier quoted statements in Dominiques Autobiography have been made and written by him. Taken together with the other relevant facts extant herein that Dominique, during his lifetime, and Jenie were living together as common-law spouses for several months in 2005 at his parents house in Pulang-lupa, Dulumbayan, Teresa, Rizal; she was pregnant when Dominique died on September 4, 2005; and about two months after his death, Jenie gave birth to the child they sufficiently establish that the child of Jenie is Dominiques.

In view of the pronouncements herein made, the Court sees it fit to adopt the following rules respecting the requirement of affixing the signature of the acknowledging parent in any private handwritten instrument wherein an admission of filiation of a legitimate or illegitimate child is made:

1) Where the private handwritten instrument is the lone piece of evidence submitted to prove filiation, there should be strict compliance with the requirement that the same must be signed by the acknowledging parent; and2) Where the private handwritten instrument is accompanied by other relevant and competent evidence, it suffices that the claim of filiation therein be shown to have been made and handwritten by the acknowledging parent as it is merely corroborative of such other evidence.

In the eyes of society, a child with an unknown father bears the stigma of dishonor. It is to petitioner minor childs best interests to allow him to bear the surname of the now deceased Dominique and enter it in his birth certificate.

NEPOMUCENO VS. LOPEZMarch 18, 2010FACTS: Respondent Arhbencel Ann Lopez, represented by her mother Araceli Lopez, filed a Complaint for recognition and support against petitioner Ben-Hur Nepomuceno. Born on June 8, 1999, Arhbencel claimed to have been begotten out of an extramarital affair of petitioner with Araceli; that petitioner refused to affix his signature on her Certificate of Birth; and that, by a handwritten note, petitioner nevertheless obligated himself to give her financial support in the amount of P1,500 on the 15th and 30th days of each month.

Arguing that her filiation to petitioner was established by the handwritten note, Arhbencel prayed that petitioner be ordered to: (1) recognize her as his child, (2) give her support pendente lite, and (3) give her adequate monthly financial support until she reaches the age of majority. Petitioner countered that Araceli had not proven that he was the father of Arhbencel; and that he was only forced to execute the handwritten note on account of threats coming from the National Peoples Army.

The RTC granted Arhbencels prayer for support pendente lite on the basis of petitioners handwritten note which it treated as "contractual support" since the issue of Arhbencels filiation had yet to be determined during the hearing on the merits. Petitioner filed a demurrer to evidence which the trial court granted. The trial court held that, among other things, Arhbencels Certificate of Birth was not prima facie evidence of her filiation to petitioner as it did not bear petitioners signature; that petitioners handwritten undertaking to provide support did not contain a categorical acknowledgment that Arhbencel is his child; and that there was no showing that petitioner performed any overt act of acknowledgment of Arhbencel as his illegitimate child after the execution of the note. CA reversed the trial courts decision.

ISSUE: Whether or not Arhbencels claim of paternity and filiation was established by clear and convincing evidence

HELD: The relevant provisions of the Family Code that treat of the right to support are Articles 194 to 196.

Article 194. Support compromises everything indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family.1awph!1

The education of the person entitled to be supported referred to in the preceding paragraph shall include his schooling or training for some profession, trade or vocation, even beyond the age of majority. Transportation shall include expenses in going to and from school, or to and from place of work.

Article 195. Subject to the provisions of the succeeding articles, the following are obliged to support each other to the whole extent set forth in the preceding article:

1. The spouses;2. Legitimate ascendants and descendants;3. Parents and their legitimate children and the legitimate and illegitimate children of the latter;4. Parents and their illegitimate children and the legitimate and illegitimate children of the latter;5. Legitimate brothers and sisters, whether of the full or half-blood.

Article 196. Brothers and sisters not legitimately related, whether of the full or half-blood, are likewise bound to support each other to the full extent set forth in Article 194, except only when the need for support of the brother or sister, being of age, is due to a cause imputable to the claimant's fault or negligence.

Arhbencels demand for support, being based on her claim of filiation to petitioner as his illegitimate daughter, falls under Article 195(4). As such, her entitlement to support from petitioner is dependent on the determination of her filiation.

In establisihing filiation, the relevant provisions of the Family Code provide as follows:

ART. 175. Illegitimate children may establish their illegitimate filiation in the same way and on the same evidence as legitimate children.

ART. 172. The filiation of legitimate children is established by any of the following:(1) The record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment; or(2) An admission of legitimate filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.

In the absence of the foregoing evidence, the legitimate filiation shall be proved by:(1) The open and continuous possession of the status of a legitimate child; or(2) Any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws.

The issue of paternity still has to be resolved by such conventional evidence as the relevant incriminating verbal and written acts by the putative father. Under Article 278 of the New Civil Code, voluntary recognition by a parent shall be made in the record of birth, a will, a statement before a court of record, or in any authentic writing. To be effective, the claim of filiation must be made by the putative father himself and the writing must be the writing of the putative father. A notarial agreement to support a child whose filiation is admitted by the putative father was considered acceptable evidence. Letters to the mother vowing to be a good father to the child and pictures of the putative father cuddling the child on various occasions, together with the certificate of live birth, proved filiation. However, a student permanent record, a written consent to a father's operation, or a marriage contract where the putative father gave consent, cannot be taken as authentic writing. Standing alone, neither a certificate of baptism nor family pictures are sufficient to establish filiation.

In the present case, Arhbencel relies, in the main, on the handwritten note executed by petitioner which reads:

Manila, Aug. 7, 1999

I, Ben-Hur C. Nepomuceno, hereby undertake to give and provide financial support in the amount of P1,500.00 every fifteen and thirtieth day of each month for a total of P3,000.00 a month starting Aug. 15, 1999, to Ahrbencel Ann Lopez, presently in the custody of her mother Araceli Lopez without the necessity of demand, subject to adjustment later depending on the needs of the child and my income.

The abovequoted note does not contain any statement whatsoever about Arhbencels filiation to petitioner. It is, therefore, not within the ambit of Article 172(2) vis--vis Article 175 of the Family Code which admits as competent evidence of illegitimate filiation an admission of filiation in a private handwritten instrument signed by the parent concerned.

The note cannot also be accorded the same weight as the notarial agreement to support the child referred to in Herrera. For it is not even notarized. And Herrera instructs that the notarial agreement must be accompanied by the putative fathers admission of filiation to be an acceptable evidence of filiation. Here, however, not only has petitioner not admitted filiation through contemporaneous actions. He has consistently denied it.

The only other documentary evidence submitted by Arhbencel, a copy of her Certificate of Birth, has no probative value to establish filiation to petitioner, the latter not having signed the same.

Art. 173. The action to claim legitimacy may be brought by the child during his or her lifetime and shall be transmitted to the heirs should the child die during minority or in a state of insanity. In these cases, the heirs shall have a period of five years within which to institute the action. The action already commenced by the child shall survive notwithstanding the death of either or both of the parties.

Action to claim legitimacy is imprescriptible, IF IT IS THE CHILD who claims it. In other words, he can bring the action during his or her lifetime (not the lifetime of the parents) and even after the death of the parents. If the heirs are the ones claiming, they are only given 5 years to institute the action. Instances when heirs can impugn legitimate filiation:a. When the child dies during minority;b. When the child dies in a state of insanity even if he/she is of legal age;c. If the child should die after he/she already commenced an action. Heirs cannot impugn the filiation of the child when the latter died after he/she already commenced an action IF it is an illegitimate child claiming filiation.

Art. 174. Legitimate children shall have the right: (1) To bear the surnames of the father and the mother, in conformity with the provisions of the Civil Code on Surnames; (2) To receive support from their parents, their ascendants, and in proper cases, their brothers and sisters, in conformity with the provisions of this Code on Support; and (3) To be entitled to the legitimate and other successional rights granted to them by the Civil Code. (264a)

The rights of legitimate children, conferred under Art. 174 cannot be renounced. The legitime of each child is half of the parents estate divided by the number of legitimate children.

Chapter 3.Illegitimate Children

In general, all children born of parents who are not united by a valid marriage are illegitimate. But children born of marriages under Arts. 36 and 53 are legitimate. The Civil Code classified illegitimate children into 3 main groups:i. Natural children those born of parents who, at the time of their conception, could have validly married; only the marriage of their parents is wanting;ii. Natural children by legal fiction those who are not natural children but are considered as acknowledged natural children by express provision of law; they were generally those born of void marriages.iii. Other legitimate children Writers usually group them into:a. Adulterous those born of a married person with one who is not the spouse;b. Incestuous those born of unmarried persons who cannot marry each other because of relations by blood;c. Sacreligious those born of persons who by reason of religious profession are disqualified to marry;d. Manceres those born of prostitutes.

The Family Code, however, abolished all distinctions between illegitimate children. All children conceived and born out of wedlock are illegitimate, unless the law itself gives them legitimate status. There are only 2 groups: 1) those conceived and born outside of wedlock of parents who at the time of conception of the children were not disqualified by any impediment to marry each other, formerly natural children, and 2) all other illegitimate children. The former can be legitimated, while the latter cannot be.

Art. 175. Illegitimate children may establish their illegitimate filiation in the same way and on the same evidence as legitimate children.

The action must be brought within the same period specified in Article 173, except when the action is based on the second paragraph of Article 172, in which case the action may be brought during the lifetime of the alleged parent. (289a)

Proof of illegitimate filiation same kind of evidence as provided in Art. 172. Ex. Of proof of filiation of an illegitimate child: 1) acknowledgement of paternity with the father signing at the back of birth certificate; 2) acknowledgement of paternity in a public document (notarial will) or a private handwritten instrument (holographic will or diary). If secondary proof is relied upon the child, the action to claim filiation must be brought during the lifetime of the alleged father; that is to give the father a chance to defend himself. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN LEGITIMATE AND ILLEGITIMATE: The action to claim legitimate filiation does not prescribe. On the other hand, the action to claim illegitimate filiation is barred if the action is brought after the death of the alleged parent, that is, when the evidence to prove filiation is secondary. If primary proof is used, the action to claim illegitimate filiation can be brought after the lifetime of the alleged parent. If secondary proof is used, the action must be brought during the lifetime of the alleged parent; this is to give the parent the opportunity to refute the allegations of the illegitimate child.

Art. 176. Illegitimate children shall use the surname and shall be under the parental authority of their mother, and shall be entitled to support in conformity with this Code. The legitime of each illegitimate child shall consist of one-half of the legitime of a legitimate child. Except for this modification, all other provisions in the Civil Code governing successional rights shall remain in force. (287a) Rights of illegitimate children:a. To use the surname of their mother;b. To be under the parental authority of their mother;c. To be entitled to support;d. To the legitime, which is of the legitime of a legitimate child, and other successional rights (in intestate succession). IRON RULE: All illegitimate children have no right to inherit ab intestato from the legitimate children and relatives of his father or mother, nor shall such children or relatives inherit in the same manner from the illegitimate child (Art. 992, CC). RA 9255, however, amended Art. 176, providing that illegitimate children can now use the surname of their father, under certain conditions.

Chapter 4Legitimated Children Art. 177. Only children conceived and born outside of wedlock of parents who, at the time of the conception of the former, were not disqualified by any impediment to marry each other may be legitimated. (269a)

LEGITIMATION It is a remedy by means of which those who in fact were not born in lawful wedlock and should therefore be considered illegitimate children, are by fiction considered legitimate, it being supposed that they were born when their parents were validly married. The legitimation takes place without judicial approval.

LEGITIMATED CHILDREN Illegitimate children, who, because of the subsequent marriage of their parents are, by legal fiction, considered legitimate. Requisites for legitimation:1. The child was conceived and born outside wedlock;2. The parents, at the time of the childs conception, were not disqualified by any impediment to marry each other. Not all illegitimate children can be legitimated. Those born of parents who could not be validly married due to some impediment at the time of conception of the child cannot be legitimated. The child of a couple, either or both being minors, cannot be legitimated. Non-age is an impediment which makes the child unqualified for legitimation. The couples recourse here is to adopt the child.

Art. 178. Legitimation shall take place by a subsequent valid marriage between parents. The annulment of a voidable marriage shall not affect the legitimation. (270a) If the subsequent marriage of the parents of the natural child is void, in legal effect there is no marriage; hence the child is not legitimated. Annulment of marriage of the parents does not affect the legitimation of the child. M and W lived exclusively as husband and wife, both are legally capacitated. W gave birth to A. 3 years later, M & W got married and their marriage was solemnized by the justice secretary, where the parties believed in good faith that the solemnizing officer had authority to do so. W then gave birth to B. A year later, M left W and married Y but M and Ws affair continued. W then gave birth to C. a. What is the status of A? Illegitimate but can be legitimated.b. What is the status of the marriage of M & W? VOID. Because good faith applies only to priests.c. What is the status of B? Illegitimate but can be legitimated.d. What is the status of C? Illegitimate because he was born of a bigamous marriage. The subsequent marriage took place without declaration of nullity of the first marriage. M and W lived exclusively as husband and wife, both are legally capacitated. W gave birth to A. 3 years later M left W and legally married Y. Despite the marriage, M and Ws affair continued. W gave birth to B. A year later Y died. 8 months after the death of Y, W gave birth to C. After Cs birth, M and W got married. W gave birth to D. a. What is the status of A? Legitimated.b. What is the status of B? Illegitimate.c. What is the status of C? Illegitimate but cannot be legitimated because at the time of his conception, there was a legal impediment on the part of M. At the time of Cs conception, M is still legally married to Y.d. What is the status of D? Legitimate. Art. 179. Legitimated children shall enjoy the same rights as legitimate children. (272a) Art. 180. The effects of legitimation shall retroact to the time of the child's birth. (273a) Effect of retroactivity to successional rights of the child: The hereditary rights of the child, as a legitimate child, began from the date of his/her birth.Art. 181. The legitimation of children who died before the celebration of the marriage shall benefit their descendants. (274) Effect of retroactivity: The subsequent marriage of the parents makes the child legitimate from the time of his birth, and from that moment he has all the rights of a legitimate child. If he dies, even before the parents have married, his rights as legitimate child are transmitted to his descendants, who benefit from the subsequent legitimation and inherit by representation of the legitimate child. Art. 182. Legitimation may be impugned only by those who are prejudiced in their rights, within five years from the time their cause of action accrues. (275a) The legal heirs (testamentary or intestate) can impugn the legitimation. Some grounds for impugning legitimacy: 1) The subsequent marriage of the childs parents is void; 2) The child allegedly legitimated is not natural;3) The child is not really the child of the alleged parents (sired by another man). Legitimation may be impugned within 5 years from the time the cause of action accrues, which is from the death of the putative parent because before that, the heirs of the child have no personality to bring the action.TITLE VIIADOPTION

DEFINITION: ADOPTION

A juridical act which creates between two persons a relationship, similar to that which results from legitimate paternity and relations.

PURPOSE: ADOPTION For the benefit of the adopter: persons who had no children were allowed to adopt so that they may experience the joys of paternity and have an object for the manifestations of their instinct of parenthood To extend to the orphan or to the child of the indigent, the incapacitated or the sick, the protection of society in the person of the adopter. To give children born of illegitimate unions the same consideration as those born in lawful wedlock.

In determining whether adoption shall be allowed, the welfare of the child is the primary consideration. Provisions on adoption are found in the following:a. Family Code approved on August 8, 1988.b. Inter Country Adoption Act of 1995 (RA 8043) approved on June 7, 1995.c. Domestic Act of 1998 (RA 8552) approved on February 25, 1998.

Art. 183. A person of age and in possession of full civil capacity and legal rights may adopt, provided he is in a position to support and care for his children, legitimate or illegitimate, in keeping with the means of the family.

Only minors may be adopted, except in the cases when the adoption of a person of majority age is allowed in this Title.

In addition, the adopter must be at least sixteen years older than the person to be adopted, unless the adopter is the parent by nature of the adopted, or is the spouse of the legitimate parent of the person to be adopted. (27a, E. O. 91 and PD 603)

Art. 184. The following persons may not adopt: (1) The guardian with respect to the ward prior to the approval of the final accounts rendered upon the termination of their guardianship relation; (2) Any person who has been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude; (3) An alien, except: (a) A former Filipino citizen who seeks to adopt a relative by consanguinity; (b) One who seeks to adopt the legitimate child of his or her Filipino spouse; or (c) One who is married to a Filipino citizen and seeks to adopt jointly with his or her spouse a relative by consanguinity of the latter.Aliens not included in the foregoing exceptions may adopt Filipino children in accordance with the rules on inter-country adoptions as may be provided by law. (28a, E. O. 91 and PD 603)

Art. 185. Husband and wife must jointly adopt, except in the following cases: (1) When one spouse seeks to adopt his own illegitimate child; or (2) When one spouse seeks to adopt the legitimate child of the other. (29a, E. O. 91 and PD 603)

Art. 186. In case husband and wife jointly adopt or one spouse adopts the legitimate child of the other, joint parental authority shall be exercised by the spouses in accordance with this Code. (29a, E. O. and PD 603)

Art. 187. The following may not be adopted: (1) A person of legal age, unless he or she is a child by nature of the adopter or his or her spouse, or, prior to the adoption, said person has been consistently considered and treated by the adopter as his or her own child during minority. (2) An alien with whose government the Republic of the Philippines has no diplomatic relations; and (3) A person who has already been adopted unless such adoption has been previously revoked or rescinded. (30a, E. O. 91 and PD 603)

Art. 188. The written consent of the following to the adoption shall be necessary: (1) The person to be adopted, if ten years of age or over, (2) The parents by nature of the child, the legal guardian, or the proper government instrumentality; (3) The legitimate and adopted children, ten years of age or over, of the adopting parent or parents; (4) The illegitimate children, ten years of age or over, of the adopting parent, if living with said parent and the latter's spouse, if any; and (5) The spouse, if any, of the person adopting or to be adopted. (31a, E. O. 91 and PD 603)

Art. 189. Adoption shall have the following effects: (1) For civil purposes, the adopted shall be deemed to be a legitimate child of the adopters and both shall acquire the reciprocal rights and obligations arising from the relationship of parent and child, including the right of the adopted to use the surname of the adopters; (2) The parental authority of the parents by nature over the adopted shall terminate and be vested in the adopters, except that if the adopter is the spouse of the parent by nature of the adopted, parental authority over the adopted shall be exercised jointly by both spouses; and (3) The adopted shall remain an intestate heir of his parents and other blood relatives. (39(1)a, (3)a, PD 603)

Art. 190. Legal or intestate succession to the estate of the adopted shall be governed by the following rules: (1) Legitimate and illegitimate children and descendants and the surviving spouse of the adopted shall inherit from the adopted, in accordance with the ordinary rules of legal or intestate succession; (2) When the parents, legitimate or illegitimate, or the legitimate ascendants of the adopted concur with the adopter, they shall divide the entire estate, one-half to be inherited by the parents or ascendants and the other half, by the adopters; (3) When the surviving spouse or the illegitimate children of the adopted concur with the adopters, they shall divide the entire estate in equal shares, one-half to be inherited by the spouse or the illegitimate children of the adopted and the other half, by the adopters. (4) When the adopters concur with the illegitimate children and the surviving spouse of the adopted, they shall divide the entire estate in equal shares, one-third to be inherited by the illegitimate children, one-third by the surviving spouse, and one-third by the adopters; (5) When only the adopters survive, they shall inherit the entire estate; and (6) When only collateral blood relatives of the adopted survive, then the ordinary rules of legal or intestate succession shall apply. (39(4)a, PD 603)

General effect of adoption: The general effect of the decree of adoption is to transfer to the adopting parents the parental authority of the parents by nature, to the same extent as if the child has been born in lawful wedlock of the adopting parents, except as limited by law. HOWEVER, the relationship established by adoption is limited to the adopting parent, and does not extend to his other relatives, except as expressly provided by law. The adopted cannot be considered as a relative by the ascendants and collaterals of the adopting parents, nor of the legitimate children which the adopting parents may have before or after adoption. The adopted child is entitled to inherit from 2 sources: 1) the adopting parent and 2) the parents and other relatives by blood. QUERY: Can an adopted child represent his deceased (adopting) father from the parents of his adopting father?ANS: NO. The fiction of law is only between the adopted child and adopting parent and does not extend to grandparents (parents of the adopting parent). There is no right of representation. It is as if the grandparents and the adopted child are strangers.

Example: Aminah will inherit properties of her father Papi when he dies. If Aminah predeceased Papi, will Jamaludin Jr. (Aminahs child) inherit the properties that will be acquired by his mother from Papi?Ans: YES, by right of representation.In case Jamaludin Jr. is an adopted child, will he inherit Papis properties by right of representation?Ans: NO. The FC only allows establishment of relationship between the adopting parent and the adopted child. Ascendants are excluded.

Art. 190 governs the property of the child in case he dies without a will (he dies intestate). If he left a will, the provisions of the will shall govern. Succession by adopter (Intestate): As a general rule, the adopter cannot inherit from the adopted, except in cases allowed by law:a. The adopter survives with the parents, legitimate or illegitimate, or the legitimate ascendants, of the adopted: of the estate goes to the adopter, and the other half to the parents or ascendants by nature, the parents excluding the ascendants.b. The adopter survives with illegitimate children or the spouse of the adopted: of the estate goes to the adopter, and the other half to the illegitimate children or the surviving spouse. c. The adopter survives with the illegitimate children and the surviving spouse of the adopted: 1/3 of the estate goes to the adopter, 1/3 to the illegitimate children, and the last third goes to the surviving spouse.d. The adopter survives alone: he gets the entire estate.

Adopted child is survived by:

1) Legitimate children +Illegitimate children + descendants + surviving spouseOrdinary rules on legal or intestate succession. Illegitimate childs legitime is of the legitime of a legitimate child.

2) Parents (legitimate or illegitimate) OR legitimate ascendants+Adopters

to parents or ascendants to adopters

3) Surviving spouse OR illegitimate children +Adopters

to surviving spouse or illegitimate children to adopters

4) Illegitimate children AND surviving spouse +Adopter

1/3 to illegitimate children1/3 to surviving spouse1/3 to adopters

5) Adopter Entire estate to adopter

6) Only collateral blood relativesOrdinary rules of legal or intestate succession

Art. 191. If the adopted is a minor or otherwise incapacitated, the adoption may be judicially rescinded upon petition of any person authorized by the court or proper government instrumental acting on his behalf, on the same grounds prescribed for loss or suspension of parental authority. If the adopted is at least eighteen years of age, he may petition for judicial rescission of the adoption on the same grounds prescribed for disinheriting an ascendant. (40a, PD 603)

Art. 192. The adopters may petition the court for the judicial rescission of the adoption in any of the following cases: (1) If the adopted has committed any act constituting ground for disinheriting a descendant; or (2) When the adopted has abandoned the home of the adopters during minority for at least one year, or, by some other acts, has definitely repudiated the adoption. (41a, PD 603)

Art. 193. If the adopted minor has not reached the age of majority at the time of the judicial rescission of the adoption, the court in the same proceeding shall reinstate the parental authority of the parents by nature, unless the latter are disqualified or incapacitated, in which case the court shall appoint a guardian over the person and property of the minor. If the adopted person is physically or mentally handicapped, the court shall appoint in the same proceeding a guardian over his person or property or both. Judicial rescission of the adoption shall extinguish all reciprocal rights and obligations between the adopters and the adopted arising from the relationship of parent and child. The adopted shall likewise lose the right to use the surnames of the adopters and shall resume his surname prior to the adoption. The court shall accordingly order the amendment of the records in the proper registries. (42a, PD 603)

ADOPTION

Provisions common to the:

a) Family Code approved on August 8, 1988;b) Inter Country Adoption Act of 1995 (RA 8043) approved on June 7, 1995 and;c) Domestic Act of 1998 (RA 8552) approved on February 25, 1998.

1) Adopter must be at least 16 years older than the adopted except: i) Adopter is the biological parent;ii) Spouse of the biological parent (under the Family Code the spouse of the legitimate parent of the person to be adopted). 2) If married, husband and wife must jointly adopt;

Exceptions: Under the Family CodeUnder RA 8552

a. When one spouse seeks to adopt his own illegitimate child (repealed by RA 8552); ora. When one spouse seeks to adopt the illegitimate child of the other;

b. When one spouse seeks to adopt the legitimate child of the otherb. One spouse seeks to adopt his/her illegitimate child provided the other spouse signified his consent thereto; or

c. if the spouses are legally separated

3) If an alien, must come from a country with whom the Philippines has diplomatic relations;4) Trial custody for a period of at least 6 months but under RA 8552, if adopter is a Filipino, the period may be reduced if the Court finds the same to be in the best interest of the adopted. FC is silent as to trial custody.

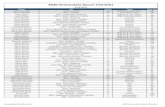

ADOPTION

FAMILY CODEAugust 3, 1988RA 8043INTER-COUNTRY ADOPTION ACTApproved June 7, 1995RA 8552DOMESTIC ADOPTION ACTApproved February 25, 1998

Who may adopt

1. In generalA person of age and in possession of full civil capacity and legal rights, provided:

1. He is in a position to support and care for his children, legitimate or illegitimate, in keeping with the means of the family.

2. At least 16 years older than the person to be adopted, unless the adopter is:a. The parent by nature of the adoptedb. The spouse of the legitimate parent of the person to be adopted.

3. Has not been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude.Any alien or a Filipino citizen permanently residing abroad:

1. At least 27 yo and at least 16 years older than the child to be adopted, at the time of the application unless the adopter is the parent by nature of the child to be adopted or the spouse of such parent.

2. If married, his spouse must jointly file for the adoption. 3. Has the capacity to act and assume all rights and responsibilities of parental authority under his national laws, and has undergone the appropriate counselling from an accredited counselor in his country.

4. Has not been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude. 5. Is eligible to adopt under his national law.

6. Is in a position to provide for the proper care and support and to give the necessary moral values and example to all his children, including the child to be adopted.

7. Agrees to uphold the basic rights of the child.

8. Comes from a country with whom the Philippines have diplomatic relations, and that adoption is allowed under the national law.

9. Possesses all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications.Any Filipino citizen or alien or guardian with respect to the ward.

For Filipino:1. Of legal age, in possession of full civil capacity and legal rights, of good moral character.

2. Not been convicted of any crime involving moral turpitude.

3. Emotionally and psychologically capable in caring for the children. 4. At least 16 years older than the adoptee, unless the adopter is:a. biological parent of the adoptee b. spouse of the adoptee's parent

5. In position to support and care for his children in keeping with the means of the family.

For aliens, refer to discussion below.

2. If aliensNOT qualified UNLESS: (a) a former Filipino citizen who seeks to adopt a relative by consanguinity;

(b) one seeking to adopt the legitimate child of his/her Filipino spouse; and,

(c) if one is married to a Filipino citizen and seeks to adopt jointly with his spouse a relative by consanguinity of the latter.QUALIFIEDQUALIFIED but should possess the same qualifications as Filipinos.

In addition: 1. His country has diplomatic relations with the Philippines.

2. He has been living in the Philippines for at least 3 continuous years prior to the filing of the application for adoption and maintains such residence until the adoption decree is entered.

3. He has been certified by his diplomatic or consular office or any government agency that he has the legal capacity to adopt in his country.

4. His government allows the adoptee to enter his country as his adopted child.

Exceptions to the residency requirement as well as certification of aliens qualification:

(1) A former Filipino citzen who seeks to adopt a relative within the 4th degree of consanguinity or affinity;

(2) One who seeks to adopt the legitimate child of his Filipino spouse; or

(3) One who is married to a Filipino citizen and seeks to adopt jointly with his/her spouse a relative within the 4th degree of consanguinity or affinity of the Filipino spouse.

3. Guardians with respect to their wardsAllowed but only after the approval of the final accounts rendered upon the termination of their guardianship relation.SilentOnly after the termination of the guardianship and clearance of his financial accountabilities.

Who May Be Adopted1. Minors may be adopted except:

a. Child by nature of adopter or his/her spouse; or,

b. Prior to the adoption, said person had been consistently treated by the adopter as his own child during minority;

2. An alien with whose government the RP has diplomatic relations;

3. An adopted child whose adoption had been previously revoked or rescinded.Only a legally free child.

Legally free child - below 15 years old unless sooner emancipated by law, voluntarily or involuntarily committed to DSWD in accordance with the CYWC.1. Any person below 18 years who has been administratively or judicially declared available for adoption;

2. Legitimate child of one spouse by the other spouse;

3. Illegitimate child by a qualified adopter to improve his/her status to that of legitimacy;

4. A person of legal age if, prior to adoption, said person has been consistently treated by the adopter as his own child during minority;

5. An child whose adoption has been previously revoked or rescinded;

6. A child whose adoptive or biological parent has died; provided that no proceedings shall be initiated within 6 months from the time of the death of the parents.

Rules with respect to adoption by husband and wifeMust jointly adopt, except:

1. When the spouse seeks to adopt his own illegitimate child.

2. When one spouse seeks to adopt the legitimate child of the other.

In case husband and wife jointly adopt or one spouse adopts the legitimate child of the other, joint parental authority shall be exercised by the spouses.Must jointly file for adoption.Must jointly adopt, except:

1. If one spouse seeks to adopt the illegitimate son of the other.

2. If one spouse seeks to adopt his own illegitimate son, provided that the other spouse has signified his consent thereto.

3. If the spouses are legally separated from each other.

In case husband and wife jointly adopt or one spouse adopts the illegitimate child of the other, joint parental authority shall be exercised by the spouses.

Who shall give consent in writing1. The person to be adopted, if 10 years or over;

2. Parents by nature of the child, or legal guardian, or proper government entity;

3. Legitimate and adopted children, 10 years or over, of adopter;

4. Illegitimate children, 10 years or over, of adopter, if living with said parent and the latters spouse, if any;

5. Spouse, if any, of the adopter or adopted.For the biological or adopted children above 10 years of age, the written consent must be in the form of a sworn statement.1. The adoptee, if 10 years or over;

2. Biological parents of the child, if known, or the legal guardian, or the proper government instrumentality which has legal custody of the child;

3. Legitimate and adopted children, 10 years or over, of the adopter(s) and adoptee;

4. Illegitimate children, 10 years or over, of the adopter, if living with said adopter and the latters spouse;

5. Spouse, if any, of the person adopting or to be adopted.

Where to file applicationFamily Court (RTC)Either Philippine RTC (Family court) having jurisdiction over the child; or with the Inter-Country Adoption Board, through an intermediate agency, whether governmental or an authorized and accredited agency in the country of the prospective adoptive parents.Family Court (RTC)

Effects of adoption1. For civil purpose, the adopted shall be deemed the legitimate child of the adopters, and both shall acquire the reciprocal obligations arising from the relationship of parent and child, including the right to use the surname of the adopters;

2. Parental authority of parents by nature over the adopted shall terminate and be vested in the adopters, except that if the adopter is the spouse of the parent by nature of the adopted, parental authority over the adopted shall be exercised jointly by both spouses;

3. The adopted shall remain an intestate heir of his parents and other blood relatives.

4. If the adopter dies prior to the decision of the adoption, the status of the petition is dismissed.Silent1. Except in cases where the biological parent is the spouse of the adopter, all legal ties between the biological parent and the adoptee shall be severed and the same shall then be vested on the adopter.

2. The adoptee shall be considered the legitimate child of the adopter for all intents and purposes and as such is entitled to all the rights and obligations provided by law to legitimate children born to them without discrimination of any kind.

3. In legal and intestate succession, the adopter and the adoptee shall have reciprocal rights of succession without distinction from legitimate filiation. However, if the adoptee and his parents had left a will, the law on testamentary succession shall govern.

4. If the adopter dies prior to the decision of the adoption, the adoption shall be issued.

Rescission of the decree of adoptionThe adopted or the adopter may rescind the adoption.SilentOnly the adoptee may ask for rescission.

Adoption, being in the best interest of the child, shall NOT be subject to rescission by the adopter. However, the adopter may disinherit the adoptee for causes provided in Art. 919 of the CC.

GROUNDS FOR RESCISSION

SilentSilentUpon petition of the adoptee, with the assistance of DSWD if a minor or if over 18 years old but is incapacitated, as guardian/counsel:

1. Repeated physical and verbal maltreatment by the adopters despite having undergone counseling;

2. Attempt on the life of the adoptee;

3. Sexual assault or violence; or

4. Abandonment and failure to comply with parental obligations.

Effects of rescissionEffects of adoption shall be effective only upon issuance of decree of adoption and the entry in the civil registry.Silent 1. Parental authority of the adoptee's biological parent, if known, or the legal custody of DSWD shall be restored if the adoptee is still a minor or incapacitated.

2. The reciprocal rights and obligations of the adopter and the adoptee to each other shall be extinguished.

3. The court shall order the Civil Registrar to cancel the amended certificate of birth of the adoptee and restore his original birth certificate.

4. Succession rights shall revert to its status prior to adoption, but only as of the date of the judgment of judicial rescission. Vested rights acquired prior to judicial rescission shall be respected.

OthersNo child shall be matched to a foreign adoptive family unless it is satisfactorily shown that the child cannot be adopted locally.

The adoptive parents, or any one of them, shall personally fetch the child in the Philippines.

The governmental agency or the authorized and accredited agency in the country of the adoptive parents which filed the application for inter-country adoption shall be responsible for the trial custody and care of the child. The trial custody shall be for a period of 6 months from the time of the placement. Only after the lapse of the period of the trial custody shall a decree of adoption be issued in the said country.Supervised trial custody for at least 6 months. The court may motu proprio or upon motion of any party reduce the trial period if it finds the same to be in the best interest of the adoptee. For alien adopter(s), he must complete the 6-month trial custody except those exempted from presenting residency requirement as well as certification of aliens qualification.

Decree of adoption shall be effective as of the date of the original petition was filed. This shall also apply in case the petitioner dies before the issuance of the decree of adoption to protect the interest of the adoptee.

No binding commitment to an adoption plan shall be permitted before the birth of the child.

An amended certificate of birth shall be issued by the civil registry. The original certificate of birth shall be stamped cancelled. The new birth certificate shall not bear any notation that it is an amended issue.