FARRELL_Camillus in Ovid's Fasti

-

Upload

valeria-messallina -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

0

Transcript of FARRELL_Camillus in Ovid's Fasti

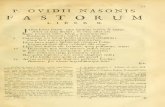

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 133

Augustan Poetry and the RomanRepublic

E D I T E D B Y

J O S E P H F A R R E L L A N D D A M I E N P N E L I S

1

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 233

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 333

Obviously one must be alert to poetic indirection in remembering the past and we must be prepared to investigate not only thematerial but also the characteristic themes and structures of history as they appear in Ovid and other poets5 But I propose to revisit thequestion of direct historical references as well These are as I notedextremely few but it seems quite likely that for this very reason they are not unimportant and if mythological episodes can be found tohave historical import then overt historical references may have aneven broader signi1047297cance than a minimalist reading would allowFollowing Hardie then I assume that Ovidrsquos references to particularevents are not only or even chie1047298y particular in their import but are in

some sense exemplary and following Wheeler I suggest that thedeployment of these references may be related to a conception of history that presents itself through discursive structures rather thanby direct narration and commentary6 In addition since these previ-ous studies focus on the Metamorphoses I will turn instead to the Fastito see whether the historical consciousness that both Wheeler andHardie detect in Ovidrsquos carmen perpetuum extends to the discontinu-ous narrative of its elegiac twin It goes without saying that anything

like a thoroughgoing survey of this subject would require muchmore space than is available here What follows then may be viewedas a test casemdashwhich if successful could become the basis of furtherresearch

My subject will be Ovidrsquos treatment of M Furius Camillus one of thegreatest heroes in all of Roman history Camillus attracts attention bothfor that reason and also because he is among the few 1047297gures from theRepublican period whom Ovid even names in his earlier poetry and he

appears in more than one episode of the Fasti as well7

The point of investigating these passages will be less to understand what Ovid has tosay about Camillus himself than to tease out what it is that Camillusallows Ovid to say about past and present

5 On Virgil see especially Delvigo in this volume6 Whereas Wheeler 2002 clearly shows that Ovid borrows the characteristic structures of

universal history however it will be seen that in my analysis the discursive structuresinvolved are not always borrowed but are sometimes also fashioned by the poet

7 Camillus is also mentioned in Amores 313 which relates Ovidrsquos attendance of afestival in honour of Juno Curitis at Falerii The close relationship between this poem andthe Fasti as it pertains to the theme of sacra has been well explicated by Miller 1991 50ndash7Camillusrsquo role in Am 313 as an emblem of Republican history merits separate consider-ation and is a second theme that I hope to address on another occasion

58 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 433

CAMILLUS AUGUSTUS AND TIBERIUS

Camillusrsquo 1047297rst appearance in the Fasti is on 16 January the natalis of theAedes Concordiae Augustae The dedicator of this temple whom Ovidnever actually names was Tiberius who had vowed to restore it inthanksgiving for his triumph over the Germans in 7 bc But the following year evidently resenting Augustusrsquo decision to prepare his grandsons ashis successors Tiberius retired from public life and began living in voluntary exile in Rhodes where he remained for ten years Whenafter the death of Lucius Caesar in ad 2 and of his brother Gaius in ad

4 Augustus had nowhere else to turn he recalled Tiberius to be his

colleague and eventually his successor in the Principate In ad 10Tiberius dedicated the new temple seventeen years after his original vow and with a different signi1047297cance than he had originally intended8

But this was not the 1047297rst time that the meaning of the Concordia cult hadevolved as Ovid himself indicates Tiberiusrsquo temple occupied a site whereseveral older Aedes Concordiae had stood Among these (tradition hasit) was one thought to have been the 1047297rst that was vowed by Camillus in3679 Ovid does not use the full title of the revamped Tiberian cult

(Concordia Augusta) but he does note that Livia mother of Tiberiusand wife of Augustus dedicated another shrine to this goddess as wellthus signifying the importance of the Concordia cult to the entiredomus10 What are we to make of Camillusrsquo appearance in this company

8 LTUR 1 317ndash19 Richardson 1992 98ndash9 sv lsquoConcordia Aedes (2)rsquo ad 7 is the date of Tiberiusrsquo triumph (Dio 5582) The temple was dedicated either in 10 (Dio 56251) or 12(Suet Tib 20)

9 Our earliest evidence for Camillusrsquo foundation is in fact this passage of the Fasti butthe episode is narrated in full by Plutarch (Cam 423ndash4) who must depend on a differentand surely an older source than Ovid On the early history of the Concordia cult see Curti2000

10 On the further signi1047297cance of 16 January see below In addition according to the fastiVerulani the following day 17 January is the anniversary of Augustus and Liviarsquos weddingOvid marks that day with only a zodiacal note (the sun passes from Capricorn to AquariusFast 1651ndash2) Critics react variously Molly Pasco-Pranger (2002 269ndash70) considers thepreceding couplet (649ndash50 the end of the Concordia passage) almost as good as an explicitreference on the following day while Carole Newlands (1995 46ndash7) 1047297nds an ironic and

even subversive comment in the rapid segue from a monogamous Jupiter to a reminder of his extramarital peccadilloes (effected via the sunrsquos passage out of Augustusrsquo astral signcf Gee 2000 137ndash42 and Volk 2009 132ndash5 146ndash53) into Aquarius (which is identi1047297ed withGanymede at Fast 2145ndash6) A typical conundrum but since even the fawning fastiPraenestini do not mention the anniversary (noting instead that the 17th was declared

feriatus to commemorate another dedication made on that day by Tiberius in honour of Augustus see Degrassi 1963 401) I am inclined not to press the point Cf Robinson 2011143ndash4 on Fast 2121

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 59

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 533

It would be easy to assume that 1047297gures like Camillus founders of templesand heroes of Republican history belong naturally within a poem thatcommemorates such occasions but this is not Ovidrsquos usual practice11

Nor can we be sure that such antiquarian information was found in actualcalendars Unfortunately we lack the entry for 16 January in our only surviving Republican calendar the fasti Antiates maiores but on otherdates when this particular calendar marks the natalis of a temple itnames only the cult involved and not the dedicator12 When we come tosources for the Julian calendar we often do get more information but notnecessarily of an antiquarian sort Here is what Verrius Flaccus says about16 January in the fasti Praenestini

Imp Caesar [Augustus est a]pell[a]tus ipso VII et Agrip[pa III co(n)s(ulibus)]Concordiae Au[gustae aedis dedicat]a est P Dolabella C Silano co[(n)sulibus)]13

Imperator Caesar was named Augustus in his seventh consulate and Agripparsquos

third [ie 27 bc] The temple of Concordia Augusta was dedicated in the

consulate of Publius Dolabella and Gaius Silanus [ie ad 10]

This entry illustrates clearly the ideological nature of Verriusrsquo calendarIts focus is on the forms of the Republican past but also on the material

of the Julio-Claudian present We know from other sourcesmdash

including Ovidmdashthat the Aedes Concordiae Augustae was not a new foundationbut a rededication and rebuilding on the site of an older temple14 ButVerrius gives no hint of this to judge by his notice alone 16 January

11 In fact Ovid generally does not record the name of a given templersquos original foundereven when he must have known it see below on the Aedes Castoris and especially on theAedes Herculis Musarum

12 It is usually assumed that the fasti Antiates maiores are typical of Republicancalendars but as it is our single surviving specimen of a pre-Julian calendar this seems tome a debatable proposition Ancient testimony about Fulvius Nobiliorrsquos calendar in theAedes Herculis Musarum indicates that it contained etymological commentary on thenames of the months (Varro Ling 663ndash4 Censorinus DN 202ndash4 229ndash13 and MacrobSat 11216ndash18) and most modern experts (eg Muumlnzer 1910 267 Boyanceacute 1955 174 n 1Degrassi 1963 xxiv and Michels 1967 125 n 18) entertain the possibility that it containedadditional learned commentary (as is suggested by Macrob Sat 11320ndash1) If so Fulviusrsquocalendar should be seen as a forerunner of the loquacious fasti Praenestini rather than of theultra-terse fasti Antiates maiores and the question of what information Republican calen-

dars lsquotypically rsquo contained would be moot See most recently Ruumlpke 1995 2006 and Feeney 2007 184ndash5

13 Degrassi 1963 115 Note that Verrius is probably correct in making this the day onwhich Augustus received his name from the senate in 27 Ovid puts the same event on 13Jan see Green 2004 271ndash2 On the ideological implications of redating the natalis of thetemple see Orlin 2007 86ndash8

14 Besides the temple vowed by Camillus (Plut Cam 423ndash5) there was a shrine vowedby Cn Flavius in 304 (Plin HN 3319) and a temple vowed by L Opimius in 121 (App

60 Joseph Farrell

oetry justify

ed to indent line 2

is the size o

pe correct

of these block

s should be

e of others

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 633

could be the dedication day of a brand new temple for a brand new cult15

It is possible that Verrius elsewhere drew the connection between earlierConcordia temples and this one but in the fasti Praenestini he doesnot16 Instead he supplies the information that a temple was dedicated onthis day mdashthe anniversary of the day on which Augustus had received hisnew name from the senatemdashand that the cult was lsquobrandedrsquo as Augustanby the ruling dynasty But then as if to establish that Augustus hadreceived his name and that the temple had been dedicated under atraditional Republican form of government Verrius dates both eventsby stating the names of the eponymous consuls in each year Because ourinformation about earlier calendars is so scanty we do not know how

novel this sort of thing may have been but once again such informationis not found in our only surviving Republican calendar17 Thus we cansee Verrius as in effect lauding the regime both for its appropriation of the state cult (while perhaps suppressing any memory of the Republicanhistory of that cult) and for maintaining Republican political institutionssuch as the consulate

Ovidrsquos entry for this date is quite different (Fast 1637ndash50)18

Candida te niveo posuit lux proxima templo

qua fert sublimes alta Moneta gradus

nunc bene prospiciens Latiam Concordia turbam

B Civ 126 Plut C Gracch 176 August De civ D 325 Degrassi 1963 15) which wasreplaced by that of Tiberius

15 Richardson 1992 states that the temple built by L Opimius in 121 was probably dedicated on 22 July cf Degrassi 1963 486

16 That is to say if Verrius published a version of his commentary on the calendar inbook form he may have explained the history of cults more fully than he does in thePraeneste inscription But the scale of the fasti Praenestini is hardly restrictive so that weshould attribute any decisions that Verrius made about what information to include orexclude there to other factors As for Richardsonrsquos suggestion (see the previous note) we donot have Verriusrsquo entry for 22 July so we cannot be sure whether he noted the natalis of any earlier Concordia temple on this date but it is not his practice elsewhere to record suchinformation

17 This is as a matter of fact just the form that Ruumlpke 1995 355 says the Republican fastiought to have employed in order to be considered historical records a condition to which(he believes) they nevertheless approximated Feeney 2007 184ndash5 takes exception to

Ruumlpkersquos assertion that the recording of temple foundations and the like absent the namesof the dedicators nevertheless amount to lsquoan abbreviated symbolic image of the history of the Roman peoplersquo arguing instead that lsquoit is hard to see a distinctively political andhistorical power in such a vague form of notation in which the traces of a foundationalact by an individual are always liable to be swallowed up by the cyclical and corporatemomentum of the documentrsquo Note that both Ruumlpke and Feeney regard the terseness of the

fasti Antiates as typical of Republican calendars see n 12 above18 Green 2004 226

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 61

is any possibility of

this quotation on the

ng page and keeping it

ther that would be preferable

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 733

nunc te sacratae restituere manus 640Furius antiquam populi superator Etrusci

voverat et voti solverat ille 1047297

demcausa quod a patribus sumptis secesserat armis volgus et ipsa suas Roma timebat opes

causa recens melior passos Germania crines 645porrigit auspiciis dux venerande tuis

inde triumphatae libasti munera gentistemplaque fecisti quam colis ipse deae

hanc tua constituit genetrix et rebus et arasola toro magni digna reperta Iovis 650

640 nunc del edd hic w ut Kreussler nam Riese qua Shenkl | restituere Uzw constituere Av

The next day placed you in a snow-white temple where tall Moneta raises herlofty steps bright Concord now enjoying an excellent view of the Latian throngnow sacred hands have restored you Furius the conqueror of the Etruscanpeople had vowed a temple long ago and he had redeemed the promise of his

vow His motive was that the rabble had taken up arms and seceded from thefathers and Rome herself was afraid of her own strength The recent motive is

better Germany spreads her 1047298owing tresses in surrender to your auspicesreverend leader And so you offered gifts made possible by your triumph overthat nation and built a temple to the goddess whom you worship yourself Yourmother the only woman found worthy of great Jupiterrsquos bed has made a place forthis goddess by means of her own acts as well as an altar

This is as A J Boyle well notes lsquoa densely packed piece of writing rsquo19 Itconveys much more information than Verriusrsquo notice even if it does soin the allusive manner of a poem rather than the apparently plain-spoken

style of a public inscription Unlike Verriusrsquo calendar it sets up a numberof comparisons some explicit (melior 645) others implied And the mostimportant of these along with a certain depth of historical perspectiveare created by the introduction of Camillus

The most explicit comparison between the old and new temples (ormore strictly between the reasons for building them) implies two or eventhree others The 1047297rst of these involves Tiberius and Camillus But Ovidrsquosallusiveness and especially his decision not to name Tiberius allows the

presence of Augustus to be felt throughout the passage and so to hint at acomparison between Camillus and him as well20 Reference to Augustus

19 Boyle 2003 19220 In some such way one might read this passage as a miniature if complex elenchus

not unlike the simpler much more explicit (and rhetorically exuberant) one between

62 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 833

is implied anyway by the theme of rebuilding old temples a basicelement of Augustusrsquo public image21 Moreover Camillus is a conven-tional avatar of Augustus in the historical tradition22 Both are remem-bered as lsquosecond foundersrsquo of Rome23 Both were hailed as pater or parens patriae24 Each was represented as successfully opposing thosewho thought of moving the capital to other locations25 Each heldextraordinary of 1047297ce in times of emergency and did so repeatedly before(at least in theory) re-establishing constitutional regularity26

This last point is particularly important Camillusrsquo temple we learndated to one of the periodic lsquosecessionsrsquo threatened by the plebs whenthey were unable to wrest civil rights from the ruling patricii (643ndash4)27

The cause of this particular threat was the senatersquos refusal to ratify theleges Liciniae Sextiae of 367 which provided among other things that infuture at least one of the consuls would always be chosen from the ranksof the plebeians28 Camillus who had recently been appointed dictatorto deal with a military crisis resolved the impasse by persuading hisfellow patricians to accept the laws in return for the creation of a new

Romulus and Augustus in book 3 in which Augustus is revealed to be an improvement on alegendary national hero And this sort of elenchus was as is well known encouraged by Augustus The most ambitious expression was in the sculptural programme of the ForumAugustum which according to Suetonius ( Aug 315) Augustus intended as an exemplar against which he and his successors would be judged The princeps then invited the sort of comparison that Ovid explicitly makes between Augustus and Romulus and implicitly between Augustus or Tiberius and Camillus This comparison might have been felt stillmore strongly if Ovid had not transferred the anniversary of Augustusrsquo naming day to13 Jan (n 13)

21 This theme too would be more vividly present if in line 640 we accepted the reading restituere (found in the eleventh-century codex U and a few later witnesses) instead of constituere (the reading of the tenth-century codex A and the majority of later witnessesOvid of course explicitly mdashwhether ironically (Boyle 2003 230) or notmdashcelebrates Augustusas a restorer of temples on 1 Feb the natalis of the Aedes Iunonis Sospitae (255ndash72)

22 The essential points are well summarized by Stevenson 2000 34ndash5 For an intriguing reformulation of the communis opinio see Gaertner 2008

23 In Livy the triumphant Camillus is hailed by his soldiers as Romulus parens patriaeconditorque alter urbis (5497) cf Plut Cam 11 in malam partem 312

24 Momigliano 194225 Mommsen 1889 [1976] 175ndash6 Momigliano 1942 115 Fraenkel 1957 268 and

Gaertner 2008 27 n 1 5226 Plutarch notes that Camillus was 1047297 ve times dictator but ironically never consul and

explains this anomaly with reference to the unsettled political conditions of his times (Cam11ndash3) In effect then he makes Camillus a man of Concordia in a time of Discordia Onthis motif see further below

27 Cf turbam 639 and uolgus 644 The epithet Latiam (639) while in the 1047297rst instancehere as elsewhere in the Fasti a synonym of Romanam could also gesture obliquely towardsCamillusrsquo role in establishing Roman hegemony in Latium

28 On the legislation see Livy 634ndash42 Oakley 1997 645ndash61

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 63

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 933

magistracy the praetura which would be 1047297lled only from their ranks29

According to some sources Camillus vowed that he would build atemple to Concordia if the ordines could only 1047297nd common groundand that Ovid agrees is what happened (641ndash2)30 By thus ensuring thatthe res publica would again be ruled by consuls instead of by the boardsof military tribunes that had recently been in use Camillus restored themos maiorum and laid the cornerstone of the political consensus thatenabled Rome to grow into a great power during the Middle Republic31

In this way as well Camillus is a forerunner of Augustus who put an endto constitutional irregularity and claimed to have restored Republicangovernment Ovid does not make these points explicitly nor does he

have to they are part of the tradition that links the two menWhat then of Tiberius In effect our passage invites the reader to

compare Tiberius with both Camillus and Augustus and to 1047297nd thatTiberius surpasses Camillus much as Augustus does At the time whenOvid wrote Tiberius was Augustusrsquo adopted son and heir designated toinherit his fatherrsquos position32 The fact that he is not actually named butis addressed as dux uenerandus facilitates his inheritance of Augustusrsquo

characteristics33 In this implied reference to Tiberiusrsquo succession of

Augustus the theme of renewal which was introduced in Tiberiusrsquorestoration of Camillusrsquo temple can be seen again in a different guise

These comparisons highlight not only similarities but also differencesOvid says that Tiberiusrsquo motive for restoring the temple is lsquobetterrsquo thanCamillusrsquo reason for founding it (causa recens melior 645) Camillus

29 So Livy 642 see Brennan 2000 5930 Again our only surviving witness for this episode besides Ovid is Plutarch (Cam

423ndash4) and Plutarchrsquos immediate source which can hardly be Ovid has not beenidenti1047297ed Plutarch says that the plebs passed a law taking responsibility for the templeupon themselves Livy does not mention the temple but seems to acknowledge the traditionwhen he notes that tandem per dictatorem condicionibus sedatae discordiae sunt and ita abdiutina ira tandem in concordiam redactis ordinibus (64210 12) so Kraus 1994a ad locSee below

31 Or so it was understood On the problem of the lsquocon1047298ict of the ordersrsquo see Raa1047298aub1986

32 The problems of dating individual passages of Fasti 1 are surveyed by Green 200418ndash22 but the Concordia passage can be dated with con1047297dence to what he calls lsquophase IIrsquo of

the poemrsquos composition ad 9ndash14 if not perhaps to his lsquophase IIIrsquo ad 14ndash17 since thetemple was not dedicated until ad 10 or perhaps 12 (see n 7) Boyle and Woodard (2004181ndash2 ad Fast 1645ndash6) argue that the passage must have been written only after Augustus rsquo

death in 14 which is certainly possible but not absolutely necessary Accordingly I adopt aconservative position and assume that Ovid composed the passage when Augustus was stillalive Emphasis on concord within the Imperial family would always be reassuring but itmight seem more to the point when a succession was about to take place

33 So Fantham [1985] 2006 400 n 52

64 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1033

famous as the conqueror of the Etruscans (641) was forced to turn hisattention from external enemies to the problem of seditious activity within the state34 Tiberius 1047297nanced his refoundation from the spoils of foreign campaigns (645ndash8) This contrast instantiates a basic element of Augustan propaganda namely that civil strife is a perversion of Rome rsquosproper mission which is to conquer and rule the world Tiberius thenhas restored not just a temple but a pattern of behaviour so conventionalthat it seems almost natural And Ovid has made this point in a way thatis both tactful and sophisticated The legitimacy of Augustusrsquo govern-ment was always based on the fact that he had ended civil war andprevented its return Ovidrsquos earlier poetry is notable for taking that

accomplishment absolutely for granted and by the time when he waswriting the Fasti and particularly when he was composing passages likethis one the previous round of civil wars effectively concluded in 31 bc

by the Battle of Actium was at least forty years in the past But during allthat time it was Augustus himself who had personally ensured thecontinuation of peaceful conditions By the time Ovid wrote theselines the princeps was an old man35 The best safeguard against civilwar would be a clearly identi1047297ed successor displaying his military

prowess on the frontier against foreign foes and this is what Tiberiusprovides

Camillus then is not just a conqueror from the distant past As aparticipant in the con1047298ict of the orders he stands for civil strife and sofor Roman memories of the most recent round of civil warsmdashand also forany latent anxieties about the future Mentioning him allows Ovid toaddress this unwelcome theme but to do so indirectly In effect associ-ating the theme of civil strife with a 1047297gure from the early Republican past

is a way of suggesting that the very idea of civil strifemdash

particularly aspertains to any possible crisis of leadershipmdashbelongs to the distant pastas well In this way too Camillus is speci1047297cally a stand-in for Augustusboth men had to deal with internal as well as external con1047298ict and they did so successfully But Camillus who lived at a time when the Repub-lican system of government had not yet matured into its classical formwas called away from his proper role as conqueror to address internaldiscord36 Conversely Augustus lived at a time when the Republican

34 According to tradition Camillus had just won a decisive victory over the Gauls and hadbeen voted a triumph when the threat of secession arose (Liv 6424ndash8 and Plut Cam 40ndash2)

35 See n 3236 One could say that the lsquoreappearancersquo of Camillus as a civic leader in the Fasti after

being introduced as the conqueror of Falerii in Am 313 represents intertextually thisturning away from external to internal affairs

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 65

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1133

system was long past maturity and well into its senescence He inheriteda heavy burden of internal con1047298ict imposed peace and then turned hisattention to foreign enemies for the remainder of his life And now hischosen successor Tiberius is following in his footsteps

The new rulers surpass the ancient Republican prototype in anotherway Not only does Tiberius 1047297ght external instead of internal battles hedoes so in a way that is fully characteristic of his father His victories inkeeping with Ovidrsquos programme of celebrating arae instead of arma(Fast 113) are represented almost as religious ceremonies rather thanarmed con1047298icts as Germany falls not to the weapons but to the auspiciisof the dux uenerandus (646) and the new temple is dedicated by his

sacratae manus (640)37 Here too Camillus is an effective foil Hisreputation was not after all that of a mere soldier It was he whodefeated Veii in 394 by performing the rite of euocatio causing Juno toabandon the city by promising her a new cult in Rome38 It was he who in390 after retaking Rome from the Gauls and lsquobeing rsquo as Livy sayslsquoexceptionally dutiful in matters of religion that pertain to the immortalgods requested and obtained a decree of the senate that all religiousbuildings that had been in the possession of the enemy should be

restored and puri1047297edrsquo together with a number of additional religiousprovisions39 On that same occasion it was he who prevented his fellow citizens from relocating to Veii on the grounds that (again in Livy rsquoswords) lsquowe have a city founded in accordance with auspice and augurythere is no place in it that is not full of religious and divine signi1047297cancersquo40

Camillus is thus a convincing early Republican prototype for the kind of princeps that modern Rome requires But as Ovid says his successors areeven better

The comparison glosses over certain changes between lsquothenrsquo and lsquonow

rsquo

that are in fact quite signi1047297cant Chief among them is the cult of Con-cordia itself This had always been about the cooperation of different

37 The theme of auspices must point to Augustus as well by virtue of a shared etymology 1047297rst invoked by Ennius ( Ann 154ndash5 Sk) in a speech that refers to the founding of Romeand that is commonly attributed to Camillus himself (For the appearance of the sametheme in the corresponding speech in Livy see n 105 below) The relationship betweenCamillusrsquo and Tiberiusrsquo northern enemies could be relevant as well Camillus was the hero

who saved Rome from the Gauls but not before they entered and sacked the city Tiberiusby contrast takes the 1047297ght to the even more fearsome Germani in their own territory

38 Liv 5211ndash3 This is in fact the only explicitly attested rite of euocatio that we know39 Liv 5501ndash2 omnium primum ut erat diligentissimus religionum cultor quae ad deos

immortales pertinebant rettulit et senatus consultum facit fana omnia quoad ea hostis possedisset restituerentur terminarentur expiarenturque

40 Liv 5502 urbem auspicato inauguratoque conditam habemus nullus locus in ea nonreligionum deorumque est plenus

66 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1233

parties within the Roman state and not about the imposition of peacethrough military conquest abroad41 In addition most modern interpretersagree that the new cult of Concordia Augusta had less to do with foreignaffairs than with harmonious relations within the domus Augusta42 Whatthe two cults have in common as most interpreters also agree is that any cult of Concordia inevitably signals the existence of Discordia in what-ever the relevant sphere may be43 So just as Camillus vowed his templein order to address discord between the plebeians and the patriciansTiberius built his to address the perception of discord within the ruling family44 Concordia then was not just or even principally a conditionthat brought about victory over the Germans rather that what needed

celebrating was the harmony newly established within the domus Augustawhen Tiberius de1047297nitively became Augustusrsquo heir

A similar point is registered in the entry on 27 January when Tiberiusrededicated the Aedes Castoris in his own name and that of his latebrother Drusus implicitly likening the sons of Livia to the dei Ledaeithose embodiments of fraternal concord the Dioscuri (1705ndash8) This isthe only other act of Tiberius that is recorded in the Fasti It must besigni1047297cant that both entries involve temple dedications and that both

41 It is true that Enniusrsquo Discordia (fr 225 Sk) appears at the opening of a new con1047298ictimmediately after the successful conclusion of the First Punic War and Skutsch (1985 394)identi1047297es this as the destruction of Falerii Veteres Whether Ennius represented this con1047298ictas between Rome and a long-time if somewhat fractious ally as a quasi-civil con1047298ict isunclear but echoes of this passage tend to involve civil war see Lange 2009 143ndash4 andBreed Damon and Rossi 2010 4ndash6 It is impossible to say whether Naevius explicitly contrasted the harmonious nature of his Camenae (fr 1 Stz) with the theme of discord inrelation to his poemrsquos subject

42 This point has been fully appreciated see eg Levick 1978 226ndash9 Fantham [1985]2006 399ndash402 Kellum 1990 Barchiesi 1997a 169 Newlands 1995 44ndash7 and 2002 244ndash5Littlewood 2002 194 Pasco-Pranger 2002 267ndash6 and Boyle 2003 192

43 The point was 1047297rst made according to Plutarch by the anonymous composer of agraf 1047297to scrawled on the Temple of Concordia built by L Opimius aeligordf I AElig AElige

rsaquo AElig OslashE lsquoa deed of madness [or] discord produces a temple of concordrsquo (C Gracch179) on this episode see below Cf Augustinersquos often-quoted sententia on the Romanpenchant for venerating Concordia cur enim si rebus gestis congruere uoluerunt non ibi

potius aedem Discordiae fabricarunt (De civ D 325)44 The lsquoprivatizationrsquo of the Concordia cult as a means of addressing perceived tensions

between individuals had begun during the triumviral period Dio (49186ndash7) notes that thefuture Augustus following the execution of Sextus Pompeius celebrated games in theCircus and lsquoset up for Antony a chariot in front of the rostra and statues in the Templeof Concord giving him also authority to hold banquets there with his wife and childreneven as had once been voted in his own honour For he pretended to be Antony rsquos friend stilland to be consoling him for the disasters in1047298icted by the Parthians and in this way he triedto cure the jealousy the other might feel at his own victory and the decrees which followeditrsquo (trans Cary 1917 379ndash81)

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 67

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1333

emphasize familial harmony45 Further by mentioning that Livia toofounded a shrine to Concordia (1649ndash50) Ovid anticipates a fullertreatment of that monument on 11 June (6637ndash48)46 There just as hedoes in the entry concerning Tiberiusrsquo Concordia temple Ovid stressesthe conditions of marital harmony that she and Augustus enjoyed

hanc tua constituit genetrix et rebus et ara

sola toro magni digna reperta Iovis (1649ndash50)

Your mother the only woman found worthy of great Jupiterrsquos bed

has made a place for this goddess [Concord] by her own acts and by

an altar

te quoque magni1047297ca Concordia dedicat aede

Livia quam caro praestitit ipsa viro (6637ndash8)

Livia also makes you the dedication of a magni1047297cent temple

Concord which she personally offered to her dear husband

As everyone agrees Livia and Tiberius by dedicating temples toConcordia wished to advertise the existence of harmonious relationswithin the domus Augusta and so to stress that Tiberius was unambigu-ously to succeed Augustus and would do his part to maintain the favour-

able conditions that his predecessor had established But Ovid whiletactfully glancing at this underlying reality emphasizes a contrast betweenConcordia as a product of Camillusrsquo management of internal affairs onthe one hand and Tiberiusrsquo conduct of foreign wars on the other insteadof openly acknowledging the new reality mdashnamely that obtaining Con-cordia in all matters of state internal or external depends on the priorexistence of Concordia within the ruling family In other words Ovid callsthe readerrsquos attention to a contrast between different kinds of discord (civil

disturbance and foreign war) in order to mask a distinction betweendifferent kinds of concord (within the state and within a single family)All Romans would 1047297nd foreign wars more acceptable than civildisturbance but would they agree that harmony within a single family was more important than harmony within the state as a whole Obviously not unless they agreed that this was the new reality that any politicaldifferences among members of the domus Augusta far outweighed any similar differences among different components of the populus RomanusAnd precisely this is the new reality that Ovid recognizes

45 Here Ovid makes no reference to the well-known story of the original foundation orits subsequent history (on which see Boyle 2003 189ndash90) The mythical brothers are theonly explicit point of comparison

46 This monument also known as the Aedes Concordiae according to Richardson 199299ndash100 was lsquosubstantially identicalrsquo to the Porticus Liviae

68 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1433

THE LIMITS OF COMPARISON REMEMBERING

AND FORGETTING

At this point let us admit once again that Ovid does not spell out all of the comparisons that I have been making nor does he refer to all of thehistorical realities that I have adduced He does make the 1047297rst most overtcomparison between Camillusrsquo reasons for vowing a temple to Concordiaand those of Tiberius which he pronounces lsquobetterrsquo (melior 645) But heimplies several other comparisons in a way that engages and stimulates thereaderrsquos imagination And as I hope I have shown some knowledgemdashsome historical memory mdashof the individuals and events involved greatly

enhances onersquos appreciation of the passage and is in fact necessary in orderto understand it even in a fairly basic way But does more knowledgealways result in better appreciation Or at some point does more know-ledge become too much Is a more comprehensive memory always desir-able or is Ovidrsquos ideal reader blessed with some historical amnesia as wellWe have already seen some indication that the ability to forget or to forgetpartially or to overlook is one that Ovid assumes and shares with hisreader in this very passage Both Augustus and Camillus had to deal with

civil strife but Ovid manages his comparison between the two in such away that the theme attaches itself directly only to Camillus while Augustus(and with him Tiberius) emerges as a leader who has left the threat of civilstrife to the ever-receding Republican past The comparison in effectpermits the reader to forget that Augustus was ever a civil warrior orthat he and Tiberius were ever at odds The question I ask now though iswhether it requires the reader to forget these facts or permits them to beremembered as well

As an illustration of what is at stake consider the following Ovidpraises Camillus as the populi superator Etrusci (641) and Tiberius asconqueror of Germany (645ndash6) But on the occasion when Camillus vowed this Concordia temple in 367 his most recent military victory was also over a northern invader the Gauls whom he had once beforeand more famously repelled after they had captured the city in 39047 Inthe spectrum of Roman enemies the barbarians to the north be they Gauls Germans or Scyths are all of a general type They represent the

sort of threat as Ovid would have us believe that was a fact of life for himin Tomis when he was composing this very passage48 The author of the

47 Liv 543ndash55 Dion Hal 136ndash9 and Plut Cam 23ndash32 further references inBroughton 1951 195

48 Williams 1994 8ndash25 considers Ovidrsquos representation in comparison with the probablerealities

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 69

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1533

Tristia and the Epistulae ex Ponto might 1047297nd it signi1047297cant that Camillusand Tiberius were both victorious over barbarian enemies to the northeven if under different circumstances from those he himself facedIndeed a further similarity might occur to him both Camillus andTiberius were illustrious exilesmdash vindicated in fact when they wererecalled to Rome to face their respective barbarian foes49 And of courserecall to Rome was the fate for which the relegated Ovid longed This isthe central theme of the Tristia and the Epistulae ex Ponto but it iscertainly present in the Fasti (and perhaps in the Metamorphoses) aswell50 So it would be easy to extend the comparison in this directionIt would have been tactless to mention these similarities openly even if

1047297nally they do no dishonour to the ruling house Perhaps Ovid de1047298ectsany inference that he means the comparison to go so far when he callsCamillus the conqueror not of the Gauls but of Etruria In other wordsperhaps by making this choice he instructs his reader to remember Veiiand to forget about exile and the Gauls On the other hand perhaps hecounts on having readers who do not forget such things

No matter how we decide about barbarians and exiles it is clear thatwhatever point Ovid is making here can hold only if one remembers and

forgets just the right things about the careers of Camillus Tiberius andAugustus And this problem only becomes more intense and moreintriguing when one remembers that this passage is not just aboutCamillus Tiberius and Augustus themselves but about a monument

MONUMENTUM MONERE MONETA

Monuments like the Aedes Concordiae were particularly rich reposi-tories of cultural memory51 In terms of their design and of the other

49 Camillus was exiled in 391 and was living in Ardea at the time of the Gallic invasion(Liv 5328ndash9 Val Max 532a and Plut Cam 12ndash13 Henderson 2000) Tiberius hadreturned from Rhodes but was living in Rome as a privatus at the time of Gaiusrsquo death whenhe was immediately dispatched to deal with an emergency on the German frontier (SuetTib 15ndash16 and Dio 5510andash13)

50 The theme of exile is quite overt in the Fasti (eg 2444 3595 and 4791) in the Metamorphoses it is represented mainly by heroes like Cadmus and Aeneas who leave theirhome to found a new city (a prominent motif in the Fasti as well particularly in connectionwith Evander 1477ndash97 539ndash40 and 591) and the theme of exile from Rome is altogetherabsent (in contrast to the Fasti see 6665ndash6)

51 On the built environment of Republican Rome and particularly on the wealth of manubial temples in the city as a representation of collective memory see Houmllkeskamp2004 (with further reading 492ndash3) Individual temples have tended to be viewed as

70 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1633

monumenta that they contained (works of art spoils of war cult objectsand so forth) they were like the memory palaces of rhetorical theory andas such they offered an extraordinary number of powerful stimuli forhistorical memory52 And such stimuli are dif 1047297cult to limit or control Itis true that all monuments have an intended meaning one that presum-ably does honour or at least is not embarrassing to the dedicator53 ButOvid himself in another context states that no one could make visitorsto temples remember only what they were supposed to remember andforget the rest Writing to Augustus in the second book of the Tristia heexplains that it is impossible to avoid sending unintended messages inpoetry by arguing that even in temples built to honour the gods one is

surrounded by reminders of divine peccadilloes (287ndash302) The argu-ment is self-serving and speci1047297cally concerns mythology and sexualmorality But it has a potentially wide application to history as wellWhen Ovid mentions the foundation of an old cult like that of Con-cordia and especially when he calls attention to its age by contrasting what was thought to be its original foundation in the extremely distantpast with its most recent refoundation it is dif 1047297cult to see what he coulddo to limit the readerrsquos imagination and prevent him or her from

remembering other episodes of refoundationmdashor indeed any otherhistorical lore about the cult or the site that he or she might possess

A reader might admit this and yet still feel that the entire history of amonument is not necessarily relevant to every entry in Ovidrsquos Fastimdashthatit is only the monumentrsquos intended meaning that counts and that thereader is to forget as if by tacit agreement any aspect of its history thatOvid does not make interpretatively relevant by mentioning it openly Inthis case then only the foundation of the Aedes Concordiae by Camillus

and its refoundation by Tiberius would be admissible elements in aninterpretation of this passage But another reader might counter that to

museums and as venues for celebrating the accomplishments and taste of the latestdedicatee but it seems clear that refounded and restored temples possess the capacity toembody and represent social memory as a collective process characterized by a complex stratigraphy The latest founder will always in one sense have the last word but evenattempts by him to eradicate traces of earlier instantiations can amount to a form of

remembering52 The extraordinarily strong linkage between architecture and memory in Roman

culture has been and continues to be explored see in particular Vasaly 1993 especially chapters 1 and 2 pp 15ndash87 Jaeger 1997 especially chapter 1 lsquoThe History as a Monumentrsquopp 15ndash29 Small 1997 especially chapter 14 lsquoIndirect Applications of the Art of Memory rsquopp 198ndash212 Walter 2004 Houmllkeskamp 2005 249ndash71 Lamour and Spencer 2007 and Sumi2009 167ndash86

53 On the intended signi1047297cation of the Concordia temple see above all Kellum 1990

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 71

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1733

forget most of what one knows would be a paradoxical way of interpret-ing a monumentum the function of which is monere a word that coversa range of meanings that is broader than but that includes lsquoto remindrsquo54

And lest we forget this fact Ovid does mention at the very beginning of our passage that the temple of Concordia stood close to that of JunoMoneta (638) Ancient authorities were divided as to the origin of thiscult but most agreed that its name like monumentum derives frommoneremdasheven if ironically again they disagreed about what warning orreminder earned Juno this title55

There are clear indications that the presence of Moneta in this passageis anything but casual Ovidrsquos ostensible point is simply to distinguish

this Concordia monument from others that stood in different locationsOr else to remind us of them And it is reminding that comes to the foreat the end of the passage where we learn that Livia too is the dedicatrix of a Concordia monument (649) These two Aedes Concordiae ded-icated by mother and son prove to be a framing device not just of thispassage but of the entire poem56 For the natalis of Liviarsquos shrine is11 June and the entry describing it is found at 6637ndash48mdasha positionwithin book 6 that is closely analogous to that occupied by Tiberiusrsquo

temple in book 1 (637ndash50)57

So beyond merely distinguishing thesetwo temples from one another Moneta plays her traditional role by reminding the reader that there are more than one Aedes Concordiaeand thus signalling that Ovidrsquos treatments of both monuments framehis poem

Furthermore it is not surprising that Ovid should mention any of Junorsquos cults in a passage that features Camillus who has a strong af 1047297nity for the goddess58 In the Fasti passage when Ovid calls Camil-

lus the conqueror of Etruria (1641) the reader may well remember hisevocatio of Juno during the siege of Veii and his vow to install her in

54 Varro Ling 64955 Cicero (Div 1101) is sceptical about the derivation from moneo but offers no

alternative See Meadows and Williams 2001 on Moneta lsquoas a goddess connected withaccurate memory and recording and the accurate preservation of records from the pastrsquoand lsquoas unimpeachable guardian of recordsrsquo (28) together with a discussion of the AedesIunonis Monetae lsquoas a centre for the recording of past eventsrsquo (48)

56 Here I accept argumenti causa the idea that the six books of the Fasti are structured asa complete poem that thematizes its apparently fragmentary nature The most compelling consideration of lsquothe endrsquo of the Fasti remains that of Barchiesi 1997a 259ndash72

57 Note that in both passages Ovid addresses Concordia (te 1637 and 6637) and alludesto the marital bliss that Livia and Augustus enjoyed (1650 and 638) cf Tiberiusrsquo appear-ance as heres (6646)

58 Again cf Camillusrsquo prominent appearance in connection with a festival of Juno at Am 3132

72 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1833

Rome as Juno Regina59 But Moneta is a particularly appropriatecompanion for Camillus as we learn when we reach her templersquosdedication day 1 Junemdashwhich is therefore like Liviarsquos Aedes Concor-diae also in book 6

Arce quoque in summa Iunoni templa Monetae

ex voto memorant facta Camille tuoante domus Manli fuerat qui Gallica quondam

a Capitolino reppulit arma Iovequam bene di magni pugna cecidisset in illa

defensor solii Iuppiter alte tui vixit ut occideret damnatus crimine regni

hunc illi titulum longa senecta dabat (6183ndash90)

Also on the top of the citadel they say is a temple built for Juno Moneta asa result of your vow Camillus Previously it was the house of Manlius whoonce drove Gallic weapons away from [the temple of] Jupiter CapitolinusGreat gods how good it would have been if he had fallen in that battle asa defender of your throne high Jupiter He lived only to die condemnedon a charge of wanting to be king that was the title that extreme old agegave him

The reappearance of Moneta in the company of Camillus links thispassage to the entry on the Aedes Concordiae in book 160 The twoentries functionmdashmuch as we saw in the case of Tiberiusrsquo and LiviarsquosConcordia templesmdashas a framing device for the Fasti Concordia stands637 lines after the beginning of book 1 and Moneta 622 lines before theend of book 6 In fact because of the many elements that link all threepassages it makes sense to see them as components of a single ratherextensive and elaborate framing structure61 Andmdashonce again as in the

59 Liv 520 The probable dedication day is 1 September (Richardson 1992 216 col 2and Degressi 1963 504ndash5)

60 One can also catch a faint echo of Am 313 as well cf

Cum mihi pomiferis coniunx foret orta Faliscis amoenia contigimus||victa Camille t ibi b

casta sacerdotes||Iunoni|festa|parabant cet celebres ludos indigenamque bovem d ( Am 3131ndash4)

with arce quoque in summa||Iunoni|templa|Monetae c

ex voto memorant||facta Camille t uo b (Fast 6183ndash

4)61 Moreover although Concordia herself unlike Moneta does not appear in both

passages she does appearmdashalong with Junomdashin the passage that immediately precedesthe entry on 1 June the proemium to book 6 And Juno rsquos parental role comes into play aswell In book 6 she is explicitly the mother of Iuuenta (667 68 and 76) and the collocationof temples to Juno and Mars on the 1047297rst day of Junorsquos month (6183ndash92) recalls what Marssays about the worship of his mother Juno on the 1047297rst day of his month (3251) In book 1Juno frames the passage on the Aedes Concordiae 1047297rst as Concordiarsquos neighbour Juno

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 73

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 1933

case of the two Concordia entriesmdashthese two temples founded by Camillus are clearly meant to comment on one another

The identity of lsquoCamillusrsquo in the Moneta passage happens to beuncertain According to Valerius Maximus (183) the Moneta templewas dedicated by the same person who Ovid says was responsible forthe Aedes Concordiae But according to Livy (7284ndash6) Moneta wasdedicated in 345 by a son of the great Camillus62 Ovid says nothing that would decide the matter It has been claimed that Ovidrsquos matter-of-factness in naming this Camillus indicates that he must mean thefather63 To this one could add that the appearance in this passage of T Manlius Capitolinus a contemporary of the elder Camillus takes

us in the same direction (More on Capitolinus immediately below)R Joy Littlewood however believes that lsquoOvid hails the vowerof the temple as ldquoCamillerdquo and although this was in fact the son of M Furius the younger Camillusrsquo act of pietas conjures up his illustriousfatherrsquo64 If she is right then perhaps Ovidrsquos canny deployment of names in his treatment of Camillus pater et 1047297lius recalls that of anotherfamous father Augustus and son the dux uenerandus who wouldsucceed him65

It may be ironic that Ovid has to fudge the question of which Camillusactually founded the cult of Moneta66 But surely it is signi1047297cant in amore straightforward way that he honours the goddess by reminding hisreader of what had been on the site of her temple before it was builtWhat better way in fact to celebrate Moneta goddess of memory andnot oblivion In case we forget this point he begins the entry with anetymological gloss on the cult title ( Moneta memorant 183ndash4) beforemoving on to tell us about what had been on this site prior to the

building of Camillusrsquo temple (185

ndash90)

67

The contrast with Concordia

Moneta (638) then as Livia who is both wife of JupiterAugustus (648) and again mother( genetrix 649) of Tiberius dedicator of the temple

62 Or perhaps his grandson Broughton 1951 132 n 1 The son as dictator in 350played his part in circumventing the leges Liciniae Sextiae that his father had seen throughand then commemorated with his temple to Concordia in the elections for 349 over whichhe presided he himself was elected consul along with a patrician colleague (Liv 72411)

63 Meadows and Williams 2001 3164 Littlewood 2006 lxxvi while stressing Ovidrsquos debt to Livy in book 6 of the Fasti65 Identi1047297cation of Camillus in book 6 as the son would gain support from the observa-

tion that the two Concordia temples are dedicated by parent and child66 Any confusion over the origin of the cult would only contribute to the increasing

aporia at the end of the poem see Barchiesi 1991 with the supplementary remarks of Fantham 1995 370

67 Elsewhere in Ovid it is quite clear that Juno rsquos cult titles have great poetic signi1047297cance In Amores 313 the title of Juno Curitis resonates both with the ritual slaying of the sacri1047297cial

74 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2033

in book 1 is intriguing unlike that entry the Moneta passage doesnot extend the monumentrsquos history forward in time from the age of Camillusmdashthere is in this notice no explicitly Augustan or Tiberian frameof referencemdashbut backward dwelling on the history of the site beforeCamillus built his temple68 On the other hand it does not go as far back as it might have according to tradition this same spot was the site of T Tatiusrsquo home after he made peace with Romulus69 Recalling thistradition would have resonated with the theme of concord sounded inthe earlier passage where this temple is mentioned (and the knowl-edgeable reader might make the connection even without such prompting)Instead Ovid focuses on the 1047297gure of M Manlius Capitolinus another

hero during the Gallic invasion of 390 As Ovid tells the story his househad once occupied the site and during the invasion he had saved thetemple of Jupiter Capitolinus from destruction70 This same Manliushowever was a staunch supporter of the plebeian cause in the con1047298ictof the orders and as Ovid also reminds us he was later accused by hisopponents of having designs on regnum and in 384 was executed71

Eventually his house was razed and Camillus whether father or son builthis temple there72

We 1047297nd this striking motif of lsquowhat was here beforersquo repeated later inbook 6 when we come to none other than Liviarsquos Aedes Concordiae apassage that is about as similar to that of the Moneta temple as it couldpossibly be

she-goat in the festival held at Falerii Veteres with Camillusrsquo capture of the city rsquos walls

and with the use of a spear to part the hair of Roman brides In the Fasti on 1 February thenatalis of the Aedes Iunonis Sospitae (lsquothe savedrsquo or lsquothe saviourrsquo) the cult title pointsironically to the fact that this temple has not been saved but has fallen into ruins and beenlostmdashin contrast to the many temples restored and rebuilt by Augustusrsquo restoration pro-gramme (255ndash66) A similar bit of etymologizing occurs on 1 March dedication day of theAedes Iunonis Lucinae (3255) a passage in which reference to memory (memini 248) isbrought into play for good measuremdashperhaps adding a new item to the devices surveyed by Miller 1993

68 In fact our knowledge of this temple in aftertimes is scant We do know that a mintwas established there in 273 (Suda 1220 Adler) and that it was not moved until the 1047297rst

century ad also that besides the natalis on 1 June another celebration was held there on 10October perhaps commemorating a restoration so Richardson 1992 215 who also com-ments on how strange it is that information about such an important monument should beso scarce but see the excellent account of it by Meadows and Williams 2001

69 Plut Rom 2014 and Solinus 12170 Liv 5471ndash871 Liv 62013 Val Max 631a and Plut Cam 36 see Jaeger 1997 57ndash9372 Liv 7285

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 75

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2133

The effect of Ovidrsquos mentioning the house of Vedius Pollio in thepassage on Liviarsquos Aedes Concordiae has been much discussed73 If wecompare that passage to the two others that we have been consideringwe see that they share the theme of lsquoimprovementrsquo Tiberiusrsquo Concordiatemple was built for a better reason than that of Camillusrsquo and Liviarsquostemple is contrasted favourably with Polliorsquos monstrous house As forMoneta a story about razing the house of a regal pretender (or populist

reformer) and replacing it with a temple dedicated to a goddess of remembrance and warning is not too dif 1047297cult to interpret from thededicatorrsquos point of view at least the new structure is certainly animprovement But once again the problem of what and in this casealso of how to remember is thrown into sharp relief And in view of these similarities and cross-references it seems to me that when we goback to book 1 we are not only permitted but virtually required to takeMonetarsquos appearance behind and above Tiberiusrsquo temple as a signal to

forget nothing

THE REPUBLICAN CULT OF CONCORDIA

Because of this poetic and institutional heritage it seems reasonable togive the cult title Moneta its full etymological and poetic force and toallow the goddess to do her work which is de1047297ned by the verb monereand to grant the same opportunity to all of the monumenta that Ovidcelebrates It seems particularly appropriate to do so on the natalis of the

6183ndash90

a Arce quoque in summa Iunoni templa Monetae

ex voto memorant facta Camille tuo

b ante domus Manli fuerat qui Gallica quondam

a Capitolino reppulit arma Iove

quam bene di magni pugna cecidisset in illa

defensor solii Iuppiter alte tui

c vixit ut occideret damnatus crimine regni

hunc illi titulum longa senecta dabat

6637ndash48

a Te quoque magni1047297ca Concordia dedicat aede

Livia quam caro praestitit ipsa viro

b disce tamen veniens aetas ubi Livia nunc est

porticus immensae tecta fuere domus

urbis opus domus una fuit spatiumque tenebat

quo brevius muris oppida multa tenent

c haec aequata solo est nullo sub crimine regni

sed quia luxuria visa nocere sua

sustinuit tantas operum subvertere moles

totque suas heres perdere Caesar opes

sic agitur censura et sic exempla parantur

cum vindex alios quod monet ipse facit

73 Scott 1939 459ndash62 Syme 1961 23ndash30 Flory 1984 309ndash30 Purcell 1986 78ndash105Herbert-Brown 1994 145ndash56 and Newlands 2002 231ndash43

76 Joseph Farrell

nt

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2233

Aedes Concordiae because Ovid unlike the author of the fasti Praenes-tini calls attention to the entire history of the Concordia cult from itsfoundation by Camillus in 367 to its refoundation by Tiberius in ad 10By so doing he makes the temple a witness to all but the very earliestphase of Republican history So if we allow the entire history of this cultto stimulate our memory what will we recall

The 1047297rst point to make ironically is that we cannot be sure whetherCamillus really did found the cult of Concordia If he did it is not clear thathe caused a temple to be built74 But the conditions of civil unrest underwhich he is supposed to have done so are characteristic of the cultrsquos laterhistory mdashand indeed of late Republican political history as a whole The

most notorious dedication to this goddess was the immediate forerunner of Tiberiusrsquo templemdashthe only such structure in fact that we can be sure actually was built during the Republic This is the Aedes Concordiae dedicated in121mdashprobably on the day noted in the fasti Antiates 22 July mdashby L Opimius75 This temple was a political statement of particularly Orwelliancharacter a declaration of victory in what was probably the bloodiestepisode of civil disturbance in Rome prior to the war between Mariusand Sullamdashand so in effect a triumphal monument to a civil war76 As

consul during the tribunate of C Gracchus and forti1047297ed by the senatusconsultum ultimum (which was passed on this occasion for the 1047297rst timein history) Opimius supervised the murder of Gracchus and his imme-diate followers then rounded up and executed hundreds and perhapsthousands of additional Gracchani Having thus restored lsquoharmony rsquo tothe body politic he dedicated again on the orders of the senate a templeto Concordia77 Years later in 63 another consul would assemble thesenate in that same temple to denounce a political opponent would

himself obtain the sc ultimum and would again execute Roman citi-zens without a trial78 Turbulent internal affairs at the end of the

74 LTUR 1 317 reports that traces have been found of a fourth-century structure underthe remains of Tiberiusrsquo temple cf Maetzke 1986

75 Degrassi 1963 1576 For temples as triumphal monuments see Ziolkowski 1992 Julius Caesar outraged the

people by displaying images of his Roman opponents such as Cato in his triumphal

procession (App B Civ 2101) and great care was taken to avoid the appearance thatAugustus (then Octavian) intended his triumphs in 29 to be regarded as celebrations of

victory over Antonius (Dio 51195ndash6) Mary Beard (2007 35ndash6) makes the point that forLucan a civil war is by de1047297nition one that can produce no triumph (bella nullos habituratriumphos 112)

77 Sall Iug 132 Diod 3429ndash30 Val Max 631 Vell 265 272ndash3 Plut C Gracch 17ndash19Flor 236 App B Civ 126 Auct De vir ill 656 Oros 5129ndash10 and Aug De civ D 325

78 Cicero Cat 321 Sest 26 Dom 11 Phil 219 and Dio 58114

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 77

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2333

Republic made this temple an appropriate setting for several otherepisodes of order imposed by force79 With such a history this AedesConcordiae both when it was built and for hundreds of years after-wards was the object of bitterly sarcastic commentary80 More thanany other monument in Rome it illustrates Barbara Levick rsquos conten-tion that the lsquonatural rolersquo of Concordia was lsquoas a slogan of those inpowerrsquo81

Ovid of course says nothing about Opimius and it would be easy toassume that to mention him would have been tactless at least andperhaps even self-defeating But is that really so Opimiusrsquo temple isnot entirely out of harmony with the point that Ovid seems to be making

here the new Concordia is better than the old The egregious nature of Opimiusrsquo gloating the effrontery of his wrapping himself in the mantleof Concordia might well seem something to forget But Ovidrsquos powers of invention were enormous his imagination incredibly fertile Could henot have found some way to draw a useful and appropriate contrastbetween Opimiusrsquo temple and that of Tiberius Opimius violated thesacrosanct person of a tribune and the rights of the plebs imposed orderby force and declared the result to be civic concord 1047297 ve years later he

was dead having reaped a just reward for his sacrilege82

Tiberius incontrast was in effect a tribune himself by virtue of holding the trib-unicia potestas83 His wars were against foreigners not his own peopleSurely Ovid could have drawn an effective contrast between the new princeps and this butcher84 But whether Ovid mentions him or not no

79 Cic Phil 51980 Plut C Gracch 176 and August De civ D 32581 Levick 1978 220 cf 223 cited by Newlands 2002 24482 Plut C Gracch 18183 Tiberius 1047297rst received a 1047297 ve-year grant of the tribunicia potestas in 6 bc (Levick 1976

32 238 n 26 cf Swan 2004 85 294) although he spent the entire period sulking in Rhodeshe presumably continued to hold this privilege until 2 bc Upon his adoption by Augustusin ad 4 he received a ten-year grant of tribunicia potestas along with imperium maius (VellPat 21042 Tac Ann 133 Suet Tib 161 and Dio 55132) both of which were renewedin ad 13 (Aug RG 62 Tac Ann 1107 and Dio 56218)

84 On the other hand Opimiusrsquo temple might have been represented as a monument to

the continuing tradition of resisting regnum Tiberiusrsquo temple to Concordia as we haveseen is implicated in a framing structure that involves Liviarsquos temple to the same goddessand Camillusrsquo temple to Juno Moneta And both of those structures are in turn implicatedin the theme of regal pretensions the Moneta temple replaced the house of ManliusCapitolinus a plebeian leader who was thought to have designs on regnum while thePorticus Liviae that was adjacent to or perhaps identical with her Aedes Concordiaereplaced the house of Vedius Pollio who is said not to have had designs on regnummdashastatement calculated to raise as many suspicions as it allays so Newlands 2002 233 If as

78 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2433

one else seems to have forgotten Opimius85 Can our poet after invoking the goddess of memory and marking this cult as one that could boastsuch a long history really expect his readers to do so

At least one additional monument that was built on this site beforethat of Opimius suggests that the answer is no86 It is described not as atemple but as a shrine the Aedicula Concordiae dedicated in 304 by CnFlavius and this monument has an interesting history of its own87

Inevitably it too was built as a result of civil unrest in a later phase of the same lsquocon1047298ict of the ordersrsquo that led to Camillusrsquo temple like himFlavius vowed his aedicula in an effort to effect a resolution to theproblem Flaviusrsquo speci1047297c dif 1047297culty however is worth noting himself a

plebeian he had antagonized the nobility by divulging information thathad formerly been kept under strict control And not just any infor-mation This Flavius in the words of Pliny the Elder lsquoby making publicthe dies fasti obtained such in1047298uence among the plebs that he was electedcurule aedilersquo88 Or to put the matter more plainly Flavius was the 1047297rstman in Rome to publish the fasti Should his example remind us of anyone else

The precise nature of Flaviusrsquo intervention is somewhat uncertain but

the historicity of the event is not in question It was well known to Ciceroand Livy and it remained known to later writers89 The likelihood thatOvid did not know of it is minimal That he would forgo the opportunity to comment on this episode in a poem on the calendar is thereforenoteworthy to say the least Again it might be thought that he passesover it as he does Opimiusrsquo temple as an episode of ill omen in thehistory of this cult But again surely Ovid if anyone could have found away to turn the episode to rhetorical advantage In those days he might

I have suggested the many structural and thematic linkages that draw these passagestogether cause them to supplement and to comment upon one another does this notopen the possibility of reading the Concordia temple of book 1 in terms of regnum as well

85 It seems noteworthy that Opimius receives a favourable notice at least in contrast tothe pejorative treatment of Gracchus in the periochae of Livy (ex libro LXI C Gracchusseditioso tribunatu acto cum Aventinum quoque armata multitudine occupasset a L Opimiocos ex SC vocato ad arma populo pulsus et occisus est et cum eo Fulvius Flaccus consularissocius eiusdem furoris) On Livy rsquos general hostility to populares see Seager 1977

86 An aedes Concordiae in Arce dedicated by L Manlius in 217 and struck by lightning in 211 is also attested (Liv 26234)

87 Liv 9466 and Plin HN 331988 HN 3317 publicatis diebus fastis tantam gratiam plebei adeptus est ut aedilis

curulis crearetur On the whole question see Michels 1967 108ndash1889 Cic Att 618 (which indicates that the episode 1047297gured in a lost portion of Rep) and

Mur 25 Liv 9465 Plin HN 33 Val Max 252 and Macrob Sat 1159 whilst Gell NA79 (citing Calpurnius Piso) suggests that he also knew the story

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 79

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2533

have said no one knew how to make the calendar work smoothly so thenobility kept its workings from the people and publishing such thingsmight get you into trouble nowadays the princeps himself has 1047297xedthe calendar promotes the understanding of itmdashand Ovid might haveadded hopefully favours those who assist him in this enterprise Butapparently Ovid preferred to say nothing about this important forerun-ner of both Augustus and Tiberius (as a calendrical innovator andworshipper of Concordia respectively) Very well but can it really bethat he simply did not expect his readers to notice Or that he hoped asmuch

Anyone who could believe this would have his or her faith shaken at

the very end of book 6 where Ovid repeats this strange pattern of remembering and forgetting The 1047297nal episode of the Fasti takes placein the Aedes Herculis Musarum another refoundation of the Augustanperiod it was dedicated by L Marcius Philippus Augustusrsquo stepfather tocommemorate his triumph ex Hispania in 3390 In this case as before inthe case of the Aedes Castoris Ovid gives no hint that there had everbeen such a monument before Philippusrsquo dedication91 But as everyoneknows the temple rebuilt by Philippus was originally dedicated by

M Fulvius Nobilior to commemorate his triumph ex Ambracia in 187from which he brought to Rome for the 1047297rst time a cult of the Muses92

90 On the date of the triumph see Degrassi 1947 569ndash7091 And in fact if one were desperate to sweep this problem under the rug one might

resort to the explanation that was offered in the case of Verriusrsquo notice regarding the AedesConcordiae Augustae 30 June is de1047297nitely the date of Philippusrsquo rededication but it cannotbe the natalis of any previous temple simply because in the Republican calendar June hadonly twenty-nine days (as is noted by Boyle 2003 270) So one could suppose that Ovidmight have conscientiously said something about the earlier foundation somewhere inbooks 7ndash12 In fact though Ovid never does this in books 1ndash6 when the opportunity presents itself His policy whether he acknowledges one or several (re)foundations of agiven temple is to treat them all as if they had occurred on the same day

92 And there are reasons to think that Junorsquos role as a goddess of memory also comesinto play The Muses are quite important 1047297gures in the Fasti They appear collectively asMuses Camenae and Pierides and six of them are called by their proper names Camena(e)3275 4245 Musa(e) 1660 2359 483 Pieris(-ides) 2269 4222 5109 6798ndash799Calliopea 580 Clio 554 6801 811 Erato 4195 349 Polyhymnia 59 53 and Thalia

and Uranie 554ndash55 Their presence and importance only increases towards the end of thepoem as they frame the 1047297nal two books And it is at the midpoint between these books on1 June that the dedication day of Juno Moneta is found Livius Andronicus of course usedMoneta to render the Greek Mnemosyne And Livius was something of an expert on Junohaving also composed a partheneion to appease her (in the guise of Juno Regina) Virgiladopted and adapted Junorsquos musal and mnemonic capacities at the beginning of the Aeneid the plot of which is set in motion lsquobecause of savage Junorsquos remembering angerrsquo (saevaememorem Iunonis ob iram 14)

80 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2633

This was not only an important event in itself it was celebrated by Q Ennius 1047297rst in a fabula praetexta entitled Ambracia and then(according to the theory of Otto Skutsch now widely accepted) as theclimactic episode in the 1047297rst 1047297fteen-book edition of the Annales93 Quiteapart from the fact that the Annales had not yet faded into obscurity itwas presumably a text that Ovid expected at least his better-informedreaders to recognize as an important source and model both for the Fastiand for the Metamorphoses94 In fact most students of the Fasti now regard the poemrsquos 1047297nal episode set in Philippusrsquo temple as an allusion tothe end of Annales 15 and so as a major element in an importantintertextual relationship

There is of course more Fulviusrsquo temple contained fasti probably inthe form of a painted inscription on the walls of the temple notionally composed by himself95 This calendarmdashthe Republican calendar of course not the Julian onemdashmay still have been in the temple afterPhilippusrsquo restoration unless Philippus simply replaced it with a Julianone but conceivably examples of both were on display We cannot besure about anything mdashexcept for the fact that Ovid says nothing aboutany of it Why not Are we to think that he regarded Philippusrsquo rededi-

cation as simply and completely obliterating all memory of Fulviusrsquooriginal foundation Did Ovid suppose similarly that his poem in somesense replaced that of Ennius Is the point of the Fasti to argue againstthe facts that RomulusNuma and JuliusAugustus were the only calen-drical innovators there ever were and that in the long history of theRepublic the interventions of Flavius Fulvius and many others countedfor nothing And in the realm of poetry are we to assume that Ovid rsquos Metamorphoses and Fasti do not take advantage of intertextual dialogue

with earlier masterpieces but instead were designed simply to drive allprevious competitors from the 1047297eld

93 Skutsch 1944 79ndash80 1963 89 1985 553ndash494 Barchiesi 1997b95 Macrob Sat 11216 attests the bare existence of fasti in or on the temple (Fuluius

Nobilior in fastis quos in aede Herculis Musarum posuit ) but says nothing about the

form and gives no indication of whether this calendar was in the shape of an inscriptionrather than a book whether it was painted on the interior or exterior walls of the templeand so on Ruumlpke 2006 has argued persuasively that Fulviusrsquo calendar was a paintedinscription and more to the immediate point that its content was composed with Enniusrsquohelp If this is so to what extent might the Annales have re1047298ected this fact Quite beyondthe 1047297nale of book 15 to what extent did the poem take calendrical themes into accountAnd what might these have involved For chronographic themes in the Annales seeFeeney 1999

Camillus in Ovid rsquo s Fasti 81

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2733

In the case of Ennius and Fulvius the answer seems clear it is unimagina-ble that Ovid expected to 1047297nd for his Fasti a readership suf 1047297ciently cluelessabout Roman literary and cultural history and about the conventionsof Roman poetry that they would not be attuned to the rather obviousintertextual gamesmanship that modern interpreters working with muchless evidence have found at the end of the poem and indeed throughout itThis being so Ovidrsquos reticence about Flaviusrsquo calendar and his AediculaConcordiae comes to look much less casual as well In fact it seems to mehighly characteristic that a missing bit of calendrical doctrina unites theAedes Concordiae in book 1 with the Aedes Herculis Musarum in book 6And if we glance at that passage some now familiar tell-tale signs are there

to see

lsquoTempus Iuleis cras est natale Kalendis

Pierides coeptis addite summa meis

dicite Pierides quis vos addixerit isti

cui dedit invitas victa noverca manusrsquosic ego sic Clio lsquoclari monimenta Philippi

aspicis unde trahit Marcia casta genus

Marcia sacri1047297co deductum nomen ab Anco

in qua par facies nobilitate suapar animo quoque forma suo respondet in illa

et genus et facies ingeniumque simul

nec quod laudamus formam tu turpe putaris

laudamus magnas hac quoque parte deas

nupta fuit quondam matertera Caesaris illi

o decus o sacra femina digna domorsquo

sic cecinit Clio doctae adsensere sorores

adnuit Alcides increpuitque lyram (Fast 6797ndash810)

lsquoTomorrow is the time when the Kalends of July are born Muses add the

1047297nishing touches to my efforts Say Muses who assigned you to him who

accepted his defeated stepmotherrsquos unwilling surrenderrsquo So said I and so said

Clio lsquoYou are looking at the monumenta of brilliant Philippus from

whom chaste Marcia draws her lineage a name descended from Ancus the

sacri1047297cer Marcia in whom are united lineage beauty and character Nor

should you think it unworthy that we praise her looks we praise the

great goddesses in these terms as well Caesarrsquos aunt was once married to

Philippus what an ornament what a woman worthy of that sacred housersquo Sosang Clio and the learned sisters agreed Hercules nodded his assent and

struck his lyre

82 Joseph Farrell

8122019 FARRELL_Camillus in Ovids Fasti

httpslidepdfcomreaderfullfarrellcamillus-in-ovids-fasti 2833

Quite apart from the missing calendar a variety of motifs link thispassage to the Concordia temple of book 1 Juno appears in the earlierpassage both as Moneta and as Livia and then again here as the noverca