Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

chandmagsi -

Category

Documents

-

view

191 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises(Part 1): Developing a framework

Lew PerrenSmall Business Research Unit, Brighton Business School, University of Brighton, Mithras House, Lewes Road,Brighton BN2 4ATTel: 01273 642979; Fax: 01273 642980; E-mail: [email protected]

Received: 5th January, 1999; Revised: 3rd June, 1999; Accepted: 6th July, 1999

ABSTRACT

This research examines micro-enterprises pursuinggradual growth. While very little research has beentargeted speci®cally at the growth of micro-enter-prises, there are a host of possible in¯uencing factorssuggested by the rather broader small business litera-ture. Less research has attempted to integrate the fac-tors that in¯uence growth of small ®rms into someform of model. Those models that were found had anumber of shortfalls when it came to understandingthe development of micro-enterprises. A frameworkhas been developed through this research thataddresses these shortfalls. First, it has targeted speci-®cally gradual growth micro-enterprises; secondly,it is rigorously under-pinned through empiricalresearch; thirdly, it attempts to comprehensivelycover the range of factors that in¯uence develop-ment; fourthly, it focuses on the complex interac-tion of factors that may in¯uence development.

The research ®ndings and implications are pre-sented in two parts. Part 1 develops an empiri-cally veri®ed framework that explains howgrowth is in¯uenced by a myriad of interactingfactors. This leads to a discussion of the policyimplications of the framework. Part 2 is presentedin the next edition of the Journal of SmallBusiness and Enterprise Development(JSBED) and will explore the managerial impli-cations of the framework. This will provide adiagnostic toolkit to help micro-enterprise owner-managers and advisers pursue growth. The paperis derived from research conducted initially for thesubmission of a PhD thesis at the University ofBrighton (Perren, 1996).

MANAGERIAL AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

. Four interim growth drivers in¯uencemicro-enterprise development: owner'sgrowth motivation, expertise in managinggrowth, resource access and demand.

. The interim growth drivers are in turn in¯u-enced by a myriad of independent factors.

. Growth beyond the micro-enterprise phaserequires the combined in¯uence of theindependent factors to be positive on allfour interim growth drivers.

. There is the possibility of compensation,the phenomenon where a de®cit in one fac-tor's in¯uence against an interim growthdriver can be counterbalanced by another.

. The framework provides micro-enterpriseowner-managers and their advisers with achecklist of potential compensating factorsfor each of the interim growth drivers.This should provide an agenda for stimulat-ing growth beyond the micro-enterprisephase. This theme is developed further inthe next edition of the JSBED.

. Micro-enterprise development has beenshown to be a process of slow incrementaliterative adaptation to emerging situations,rather than a sequence of radical clear stepsor decision points.

. Micro-enterprises need timely and tailoredsupport, rather than any form of standardsupply-side policies which will be wastefuland not address real needs. What is neededis support that is owner-manager centred,rather than adviser-centred.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Volume 6, Number 4

# 1999 Henry Stewart Publications, ISSN 1462±6004, 366±385

. While the framework provides a usefulmechanism for sensitising advisers togrowth issues, it would be premature torecommend its use as a way of `pickingwinners'.

KEY WORDS

Micro-enterprises, growth, factors, development,start-up

INTRODUCTIONThis research examines micro-enterprises pursuinggradual growth.1 The research ®ndings and impli-cations are presented in two parts. Part 1 developsan empirically veri®ed framework that explainshow growth is in¯uenced by a myriad of interact-ing factors. This leads to a discussion of the policyimplications of the framework. Part 2 will be pre-sented in the next edition of the JSBED and willexplore the managerial implications of the frame-work. This will provide a diagnostic toolkit tohelp micro-enterprise owner-managers and advi-sers pursue growth.

While little research has been targeted speci®-cally at the growth of micro-enterprises, there area host of possible in¯uencing factors suggested bythe rather broader small business literature. Lessresearch has attempted to integrate the factors thatin¯uence the growth of small ®rms into someform of model. Indeed a review of the literatureonly revealed seven models:

Ð Durham University Business School's (DUBS)model (Gibb and Scott, 1985);

Ð Keats and Bracker's (1988) theory of small ®rmperformance;

Ð Bygrave's (1989) entrepreneurial processmodel, adapted from Moore (1986);

Ð Covin and Slevin's (1991) entrepreneurshipmodel;

Ð Davidsson's (1991) entrepreneurial growthmodel;

Ð Na�ziger et al.'s (1994) model of entrepreneur-ial motivation;

Ð Jennings and Beaver's (1997) management per-spective of performance.

This list only includes papers which have made areal attempt to synthesise in¯uencing factors intosome form of meaningful integrative model ratherthan simply itemising factors (for example Craggand King, 1988; Box et al., 1993) or concentrating

on a speci®c aspect of growth (for example Merzet al., 1994). Jennings and Beaver (1997) broughttogether a range of factors to suggest how theymight in¯uence a small ®rm's performance mea-sured in terms of principal stakeholder's aspira-tions. Their paper is included here as the principalstakeholders may well measure performance interms of growth.

The framework derived through the researchfrom which this paper is drawn makes a usefulcontribution to our understanding of the develop-ment of micro-enterprises as it addresses gaps inthe existing integrative models. This paper high-lights four signi®cant silences. First, with theexception of Davidsson (1991), the other modelswere not aimed at understanding the developmentof these very small ®rms: Durham UniversityBusiness School's (DUBS) model was originallyaimed at ®rms with under 50 employees that wereabout to pursue the next stage of growth (Gibband Scott, 1985); Bygrave's (1989) entrepreneurialprocess model was aimed at entrepreneurial devel-opment which is driven by innovation, and whileno speci®c size of ®rm is provided, the impressionis given of fairly rapid growth to more substantialsize; Covin and Slevin's (1991) entrepreneurshipmodel was aimed at `larger established ®rms';Na�ziger et al. (1994) and Jennings and Beaver(1997) were not speci®c about the size of ®rmthey are addressing; Keats and Bracker's (1988)theory of small ®rm performance was aimed atthe US Small Business Administration's rathervague de®nition of a small ®rm, `independentlyowned and operated and which is not dominant inits ®eld of operation', but certainly they leanttowards larger scale small ®rms.

Secondly, there was lack of empirical under-pinning within the existing models. The Keats andBracker (1988), Bygrave (1989), Covin and Slevin(1991), Na�ziger et al. (1994) and Jennings andBeaver (1997) models have all relied on existingliterature and deductive logic without any empiri-cal underpinning. Indeed Keats and Bracker(1988), Bygrave (1989) and Covin and Slevin(1991) all explained that their model would bevery di�cult to test. The Davidsson (1991) modelwas based on a study of 322 Swedish ®rms, but itonly explained 25 per cent of the variation inactual growth. Davidsson (1991) commented thatthe large share of unexplained variation may bebecause his model represents average e�ects anddoes not look at the idiosyncrasies of individualcases. The DUBS model was originally based on

Perren

367Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

16 ®rms who were seeking to develop new pro-ducts and/or markets (Gibb and Scott, 1985). Sub-sequently, DUBS reported having helped over300 ®rms using the model for consultancy (Gibband Davies, 1992). The interventionary nature ofthe model's derivation calls into question howrepresentative it is of other ®rms that are not aidedby DUBS researchers/consultants.

Thirdly, only the DUBS (Gibb and Scott,1985), Bygrave (1989) and Jennings and Beaver(1997) papers attempted to address the full range offactors in¯uencing a ®rm's development. TheKeats and Bracker (1988), Covin and Slevin (1991),Davidsson (1991), and Na�ziger et al. (1994)models concentrated much more on the interactionof in¯uences on the entrepreneurial process andbehaviour. The subsequent exchange of ideasbetween Covin and Slevin (1993) and Zahra (1993)did little to alter their original model.

Fourthly, Gibb and Davies's (1992) criticisms oftheir own model are also germane to the othermodels. None of the models say much about howthe various factors identi®ed actually interacttogether to in¯uence the development of the ®rm.The factors were identi®ed and some form ofcausality suggested, but the models do not con-sider how, at the level of individual cases, the fac-tors blend together or the process of theirinteraction.

As will be shown the framework presentedherein addresses these criticisms of the existingintegrative models. First, it has targeted speci®callygradual growth micro-enterprises; secondly, it isrigorously under-pinned through empiricalresearch; thirdly, it attempts to comprehensivelycover the range of factors which might in¯uencethe development of a micro-enterprise; andfourthly, it goes someway towards addressingGibb and Davies's (1992) criticisms by consideringhow factors may blend together to in¯uencedevelopment, thus setting an agenda for futureresearch into the complex process of interaction.

DERIVATION OF A SPECULATIVEFRAMEWORK2

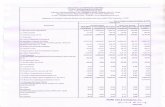

The discussion above has highlighted signi®cantgaps in our understanding of the development ofmicro-enterprises. Nevertheless, the host of possi-ble growth factors suggested by the small businessliterature can provide a speculative framework toguide the investigation. Figure 1 provides anoverview of the literature to identify 16 indepen-dent factors, each of which may interact with

four intervening growth drivers3 (Sekaran, 1992)to cause a small business to grow. It is only possi-ble to speculate from the existing literature aboutthe importance of these factors and the nature ofthe interaction between the independent factorsand interim growth drivers. The aim of thisresearch is to move beyond speculation to pro-duce an empirically veri®ed framework thatexplains how the multitude of independent factorsidenti®ed actually interact to in¯uence the gradualgrowth of micro-enterprises. The speculative fra-mework is employed in a ¯exible manner toensure that it does not restrict the free-¯ow ofideas or evidence.

METHODOLOGYSixteen case studies were selected in the followingway. A list of businesses was compiled from theclients of local ®rms o�ering accountancy serviceswho were known and respected by theresearcher.4 The resulting list was sifted so as toremove businesses that were not started by theexisting owner-manager, had grown through themicro-enterprise phase in under four years, werenot local, no longer had the original owner-man-ager involved in day-to-day management andwere not really trading (eg the business provided aconvenient front for taxation).

The reduced list was strati®ed to allow com-parison between ®rms that achieved di�erentlevels of growth and between di�erent sectors.Growth enterprises were those that had increasedemployee numbers beyond nine employees andturnover beyond £600,000. Attempted growth enter-prises, while exhibiting early growth, went on toshow marked decline in terms of employee num-bers and turnover. They never expanded beyondthe micro-enterprise level and eventually declinedto lower levels. No-growth enterprises only managedto exhibit ¯at turnover and employee ®gures.Research (such as Bolton, 1971; Curran and Bur-rows, 1993) suggested that some factors in¯uen-cing small ®rms might be sector-speci®c. Table 1shows that there are liable to be some generalsimilarities in the operations of businesses in thefour broad sectors of retailing, manufacturing,wholesaling and service. For example, retailerstend to have a large number of customers and aninformal selling process, whereas manufacturerstend to have less customers and a more formal sell-ing process. Therefore the list was further strati®edinto retailers, manufacturers, wholesalers and ser-vice providers to re¯ect potential di�erences in the

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

368 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

(F1)

D

esire

to 'b

e on

e’s

own

boss

'. Man

y re

sear

cher

s ha

ve s

ugge

sted

that

s

ucce

ssfu

l ow

ner-

man

ager

s ha

ve a

hig

h 'in

tern

al lo

cus

of c

ontr

ol',

belie

ving

th

ey h

ave

com

man

d ov

er th

eir

dest

iny

(e.g

. Bro

ckha

us a

nd H

orw

itz, 1

986;

C

aird

, 199

0; C

hell et

al.,

199

1),10

(F2)

D

esire

to s

ucce

ed. (

eg M

cCel

land

, 196

1; C

hell et

al.,

199

1),

(F3)

A

ctiv

e ris

k ta

ker.

(eg

McC

ella

nd, 1

961;

Tim

mon

s et a

l., 1

985;

Che

ll et

al.,

1991

),

(F4)

In

nova

tion.

(eg

Sch

umpe

ter,

193

4; R

othw

ell a

nd Z

egve

ld, 1

982;

Che

ll et

a

l., 19

91),

(F5)

T

rans

fera

ble

pers

onal

cap

ital. (

eg B

olto

n, 1

971;

Mas

on a

nd H

arris

on,

1

994)

,

(F6)

T

rans

fera

ble

prim

ary

skill

s. (

eg S

tanw

orth

and

Gra

y (1

991)

rep

ort t

hat

m

any

foun

ders

sta

rt u

p in

type

s of

bus

ines

s fo

r w

hich

they

hav

e pr

evio

usly

w

orke

d,

(F7)

T

rans

fera

ble

supp

ort s

kills

. (eg

Hof

er a

nd C

hara

n, 1

984;

Bos

wor

th a

nd

Jac

obs,

198

9),

(F8)

T

rans

fera

ble

netw

ork

of c

onta

cts.

(eg

Joha

nnis

son,

198

6; B

lack

burn

et

al.,

1

990)

,

(F9)

F

amily

, 'in

vest

ing'

frie

nds

etc.

(eg

Sca

se a

nd G

offe

e, 1

980;

Gill

, 198

5),

(F10

) K

ey e

mpl

oyee

s, p

artn

er. (

eg B

osw

orth

and

Jac

obs,

198

9; G

oss,

199

1),

(F11

) A

ctiv

e pr

ofes

sion

al a

dvis

ers. (

eg R

ober

tson

, 198

7),

(F12

) D

ebto

rs a

nd c

redi

tors

. (eg

Ray

and

Hut

chin

son,

198

3; S

latt

er, 1

992)

,

(F13

) S

ocie

tal a

nd o

ther

out

er fa

ctor

s. (e

g A

ndre

ws,

198

0; F

ahey

and

N

aray

anan

, 198

6),

(F14

) T

he S

tate

of t

he E

cono

my a

nd th

e G

over

nmen

t's m

anag

emen

t of t

he

Eco

nom

y. (

eg K

eebl

e et a

l., 1

993;

Lea

n an

d C

hast

on, 1

995)

,

(F15

) P

rodu

ct s

ecto

r an

d m

arke

t seg

men

ts. (e

g P

orte

r, 1

980;

Joy

ce

et a

l.,

199

0),

(F16

) C

ompe

titiv

e dy

nam

ics.

(eg

Por

ter,

198

0; C

ambr

idge

Sm

all B

usin

ess

R

esea

rch

Cen

tre,

199

2).

(G1)

Ow

ner's

gro

wth

mot

ivat

ion

is v

ital i

n su

ch s

mal

l firm

s w

here

the

ir

influ

ence

is s

o gr

eat

(eg

Sca

se a

nd G

offe

e, 1

980;

Sta

nwor

th a

nd C

urra

n,

198

6; H

akim

, 198

9),

(G2)

E

xper

tise

in m

anag

ing

grow

th is

impo

rtan

t, w

ithou

t suc

h ex

pert

ise

the

fi

rm m

ay b

ecom

e un

cont

rolle

d an

d lo

se d

irect

ion

(eg

Pen

rose

, 195

9;

Will

iam

son,

196

7; B

osw

orth

and

Jac

obs,

198

9),

(G3)

Res

ourc

e ac

cess o

f a fi

nanc

ial,

phys

ical

and

hum

an n

atur

e ar

e cr

ucia

l to

g

row

th (

eg B

olto

n, 1

971;

SB

RT

, 198

4-19

96; M

ason

and

Har

rison

, 199

4),

(G4)

Dem

and

for

prod

ucts

or

serv

ices,

whe

ther

pro

-act

ivel

y cr

eate

d or

just

in

nate

ly p

rese

nt, i

s cr

ucia

l to

succ

essf

ul g

row

th (

eg H

assi

d, 1

977;

Birl

ey

and

Wes

thea

d,19

90).

Inde

pend

ent

Fac

tors

Inte

rimG

row

th

Driv

ers

Gro

wth

of

Firm

Dep

ende

ntF

acto

r?

?

Figure

1:Specu

lativeframework

derivedfrom

theliterature

Perren

369Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

development of businesses from these broad sec-tors.

Initially the resource limitations suggested thatonly one case should be selected from each growthcategory per sector, making a total of 12 cases(three growth types multiplied by four sectortypes). Nonetheless, it was felt that more insightscould be achieved from the growth enterprises sothis group was doubled giving a total of 16; fourattempted growth cases (one from each sector);four non-growth cases (one from each sector);eight growth cases (two from each sector). Thisallowed su�cient comparison across a number of®rms for some generalisations to be made with adegree of conviction, while retaining adequatequality in the detailed analysis of each ®rm toallow the intricate con®guration of factors to beunderstood. Table 2 shows the ®rms that wererandomly selected from each strati®ed list. Therewas no statistical relevance to the randomness ofthe selection, it was simply stating that the selec-

tion was arbitrary after the strati®ed list had beencompiled.5

Multiple sources of evidence were gathered, assuggested by Yin (1993); these included taped, oralaccounts of each owner-manager's life (conductedbetween three to six months into the ®eld work),`observation' of the owner-managers and theiremployees (conducted between six to 30 monthsinto the ®eldwork), and focused semi-structuredinterviews (conducted 30 to 36 months into the®eld work).6 In addition, secondary sources wereconsulted to obtain background information onthe ®rm and its industry sector.

DEVELOPMENT OF AN EMPIRICALLYVERIFIED FRAMEWORK

A systematic approach to data capture and analysiswas taken to ensure a clear `audit trail' betweenthe data and the conclusions that were distilled(Eisenhardt, 1989; Miles and Huberman, 1994)7.

Table 1: General features of various broad industry sectors (This table was compiled from a number ofsources including: Curran and Burrows, 1993; Kurilo� et al., 1993; Steinho� and Burgess, 1993; Dibb et al.,1994.)

Feature Retail Manufacture Wholesale Service

Customers Final Consumer Normally other®rms

Normally other®rms

Can be other ®rmsor consumer

Number ofCustomers

Tends to be large Tends to be fewer Tends to be fewer Depends on service

Selling Process Tends to beinformal/simple

Tends to be moreformal/complex

Tends to be moreformal/complex

Depends on service

Credit o�ered tocustomers

Normally no credit Normally credit Normally credit Depends on service

Value creatingprocess

Through tradingconvenience oftangible products

Throughmanufacture oftangible products

Through tradingconvenience oftangible products

Through provisionof intangiblefunctions

Stock holding Trading stock Raw material and®nished goods stock

Trading stock Tends to be no orvery low stock

Trading cycle Stock bought, heldand sold toconsumer

Raw materialbought,manufactured andsold to another ®rm

Stock bought, heldand sold to another®rm

Customer requestsservice, serviceperformed

Location Tends to be highstreet

Tends to beindustrial estates and`zoned' areas

Tends to be out oftown centre, closeto customers orgood transportfacilities

Varies depending ontype of service

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

370 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

The autobiographic and semi-structured interviewswere fully transcribed, with punctuation addedcarefully to maintain the respondent's originalmeaning (Blackburn et al., 1992) and the second-ary data were carefully catalogued. Cross-referen-cing systems were developed to allow data to beeasily located while retaining its original context;for example, the autobiographic interviews8 wereline-numbered. Anonymity has been protected bypseudonyms being used for all people and placesmentioned in quotes by owner-managers. Each®rm was examined as an entity in its own right,before any cross analysis was undertaken. It wasimportant to understand the idiosyncratic interac-tion of factors in individual cases (Bell, 1987)before looking for patterns across cases.

The oral account of each manager's life and thesemi-structured interviews turned out to be themost valuable for this study. They provided theowner-managers' longitudinal perspective of their

®rm's history and the factors that had in¯uenceddevelopment. The richness of this type of dataallowed the analysis to move beyond simple corre-lation to develop an empirically veri®ed frame-work for explaining the growth of micro-enterprises.9 This is not suggesting that case studiescan provide de®nitive cause±e�ect relationships,that is even di�cult in tightly controlled labora-tory experiments (Sekaran, 1992). Case studies,however, do allow probable cause±e�ect relation-ships to be interpreted based on evidence (Yin,1993) and these can be made with greater convic-tion when multiple cases suggest similar patterns(Eisenhardt, 1989, 1991). A largely inductiveapproach was taken to the transcription analysis.The speculative framework of factors (see Figure1) provided general guidance, but the analysis wasdriven by the data and as will be shown the specu-lative framework was shown to need amendment.The systematic approach to data cataloguing

Table 2: Description of each case

Caseletter

Broadsector

Description Maximumnumber ofemployees

Maximumturnover(adjusted to1992)

Number ofemployeesin Year 311

Number ofemployeesin Year 6

Number ofemployeesin Year 9

Number ofemployeesin Year 12

Non-growthA Retail Jewellery 1 £24,000 1 1B Wholesale Consumables 3 £187,000 2 3 3 3C Manufacture Metal

Workshop1 £84,000 1 1

D Service Assessing cars 3 £139,000 2 3 3 2

Attempted GrowthE Retail Curtains 5 £194,000 4 5 3 1F Wholesale Motor spares 7 £336,000 7 3 2G Manufacture Electro-

plating7 £121,000 4 4

H Service Recruitment 8 £580,000 4 8 5

GrowthI Retail Telephone

sales12 £656,000 4 7 12

J Retail Jewellery 26 £1,068,000 4 8 12 16K Wholesale Horse

products16 £621,000 8 13 16

L Wholesale Model trains 26 £1,300,000 3 5 9 15M Manufacture Sun glasses 42 £2,290,000 8 26N Manufacture Building

frames40 £2,900,000 8 15 40

O Service Insurance 70 £2,000,000 5 22P Service Golf School 29 £800,000 3 5 29

Perren

371Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

allowed a ¯exible approach to data analysis andcategorisation so that issues could be iterativelygrouped together until patterns emerged (Riley,1990). Care was taken to keep the interpretation asclose to the data as possible and triangulation frommore than one data source was achieved for themajority of the cause±e�ect relationships (East-erby-Smith et al., 1991).

The space constraints of this paper make itimpossible to show the evidence for the 278cause±e�ect relationships explained by theresearch, so a summarised example from case G(the electro-plating company) is provided to indi-cate the nature of interpretation. This examplelooks at the data that led to the interpretation of anegative cause±e�ect relationship between theindependent factor transferable primary skills (F6)and interim growth driver demand (G4). As thenumber and scale of processes grew the owner-manager and his employees lacked the primaryskills (F6) of electro-plating to be able to satisfydemand (G4):

[Discussion of trial and error approach tomixing chemicals] `Yes. Because we worked inother companies, the back up we got as regardschemical analysis and all the rest of it; we didn'thave so we had to learn . . . You learn by error,by mistakes . . .' (Owner-manager G's responseto the semi-structured question, `As the businessdeveloped did you feel the need to develop newskills?')

[Discussion of dropping processes] `We weredoing about nine processes and we found that totry and do nine processes, we were runningaround working all hours and we couldn'treally give the customers what they wanted . . .'(Owner-manager G's oral history)

[Discussion of processes that had to be dropped]`In the beginning we did Nickel and Chromebut then we disposed of those because we hadproblems with the Water Authority . . .'(Owner-manager G's oral history)

It is also germane to explain that the work envir-onment had become horrendous. There was anacrid stench from the chemical vats and the o�ce/sta� room facilities were housed in a seeminglyunventilated cubicle at the back of the unit.

The data from each of the cases were analysedin this way to produce 277 similar explanations of

cause±e�ect relationships within the 16 cases.Table 3 summarises this information, giving thefrequency across the 16 cases that an independentfactor either positively or negatively in¯uenced aninterim growth driver to e�ect growth. This helpsto see general patterns in the data, but it still hasits origin in the detailed analysis that was con-ducted for each case.

The speculative framework can now beamended to take account of the empirical evidence(see Figure 2). The independent factors have beenranked to indicate the likelihood of them in¯uen-cing a particular interim growth driver. While thisprovides a useful overview of an independent fac-tor's general importance, a low ranked factor maystill prove to be very signi®cant for a particular®rm.

It is now appropriate to examine more deeplyhow the independent factors actually in¯uence theinterim growth drivers. Each interim growthdriver will be considered in turn, a table summar-ising the nature of factor in¯uences constructedand illustrative case examples given.

Investigating owner's growth motivation (G1)

Table 4 synthesises the empirical evidence to showhow owner's growth motivation (G1) is poten-tially in¯uenced by ®ve factors: desire to succeed(F2); desire to be `one's own boss' (F1); active risktaker (F3); family and `investing' friends etc (F9)and competitive dynamics (F16).

The owner-manager's desire to succeed (F2) isby far the most prominent, featuring in all thecases as an in¯uence of some sort on the owner'sgrowth motivation (G1) and in 13 of the cases asthe only in¯uence. In cases A, B and D theowner-managers' modest desire to succeed (F2)and wish to only achieve a certain level of incomeappears to have constrained the growth of their®rms. The quote below from the owner-managerin case B illustrates this point:

'. . .Money motivated. De®nitely because themore I make, the less I want to do in there. I'mmotivated by money because what I want,money will make it easier for me so that I cando a 2 or 3-day week. . . ' (Owner-manager B)

In cases E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O and Pthe owner-managers had a strong desire to succeed(F2) that was directed at growing the business(G1). This is depicted well by the quote belowfrom owner-manager N:

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

372 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

`There's an in-built thing in me now, I won'tstop growing until I have wiped-out all thosethat trod on me in the sixth months periodwhen I was down. It is an out-and-outchallenge to me now. The money is of no greatinterest . . .' (Owner-manager N)

To be a positive in¯uence an owner-manager'sdesire to succeed (F2) needs not only to be strongbut also to be directed towards the growth of the®rm (G1). McCelland (1961) originally proposed`need for achievement' as an important componentof entrepreneurship (Chell et al., 1991),10 subse-quently most psychologists seem to have acceptedthis view although no de®nitive research exists(Johnson, 1990). The current research can throwsome light on the di�culties that psychologists arehaving in establishing a link. Desire to succeed

(F2) and the owner's growth motivation (G1) areseparated on the framework ie some owner-man-agers appeared to have a high desire to achieve butit was not always directed towards the growth ofthe ®rm. Some owner-managers, for example,pursued a particular perception of product and ser-vice excellence that was, unfortunately, contraryto their ®rm's growth potential (G2). Owner-manager C describes the di�culty he has with cli-ents due to being `a little bit of a perfectionist':

`I possibly am a little bit of a perfectionistanyway. In fact, a lot of my customers havelooked up and said, ``that's too good a job''(Owner-manager C)

`That led to other problems because my buyersknew exactly what they were talking about.

Table 3: Frequency of an independent factor in¯uencing a particular interim growth driver

Owner's growthmotivation (G1)

Freq Expertise inmanaging growth(G2)

Freq Resource access(G3)

Freq Demand (G4) Freq

(F2) Desire tosucceed

19 (F7) Transferablesupport skills

16 (F12) Debtors &creditors

18 (F14) State ofeconomy

22

(F1) Desire to 'beone's own boss'

1 (F10) Keyemployees,partners

7 (F3) Active risktaker

16 (F15) Productsector

21

(F3) Active risktaker

1 (F9) Family`investing' friends

5 (F5) Transferablepersonal capital

13 (F16) Competitivedynamics

21

(F9) Family,`investing' friends

1 (F11) Activeprofessionaladvisers

2 (F10) Keyemployees,partners

13 (F6) Transferableprimary skill

17

(F16) Competitivedynamics

1 (F8) Transferablenetwork

1 (F9) Family,`investing' friends

10 (F4) Innovator 15

(F8) Transferablenetwork

9 (F3) Active risktaker

14

(F14) State of theeconomy

1 (F13) Societal and`outer' factors

11

(F10) Keyemployees

10

(F8) Transferablenetwork

10

(F2) Desire tosucceed

2

(F9) Family,`investing' friends

1

Perren

373Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

They knew where to shop around and where toget the cheapest for their company. Theywouldn't come to me because of all the gear Ihad. They knew they could go down the roadand the guy ain't got that equipment and get itdone cheaper.' (Owner-manager C)

The other factors in Table 4 may have lessfrequently in¯uenced the owner's growthmotivation (G1) than desire to succeed (F2),but they were nevertheless important for theparticular cases a�ected. In case L the factorsdesire to be `one's own boss' (F1) and active risk

F1. Desire to ‘be ones own boss’

F2. Desire to succeed

F3. Active risk taker

F4. Innovator

F5. Transferable personal capital

F6. Transferable primary skills

F7. Transferable support skills

F8. Transferable network of contacts

F9. Family, ‘investing’ frie nds

F10. Key employees, partners

F11. Active professional advisers

F12. Debtors and creditors

F13. Societal and other ‘outer’ factors

F14. State of economy

F15. Product sector and market segments

F16. Competitive dynamics

Independent Factors Interim Growth Drivers

G1 Owner’s Growth Motivation

G2. Expertise in Managing Growth

G3. Resource Access

G4 Demand

Owner

Growth ofMicro-enterprise

Change to Organisation

Formalisation

Delegation

Planning

Personality

Attributes

Tra

nsferableE

xperiences

Stakeholder

Patronage

Externa

lInflue

nces

F7F10F9F11F8

F2F1F9F16

F3

F12F5F10F9F8F14

F14F15F16F6F4F3F13F10F8F2F9

Figure 2: Diagrammatic summary of the empirically veri®ed framework

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

374 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

taker (F3) combined to stimulate the owner'sgrowth motivation. He felt a `large' businesswould provide the independence he soughtwithout being exposed to the risks he feared. Incase B, as discussed above, the owner-managerappeared to be motivated to achieve a certainlevel of income, rather than to grow thebusiness. Ironically, increased competition (F16)partly compensated for his low desire to succeed(F2) and increased his growth motivation (G1),although admittedly not enough to stimulate areal attempt at growth beyond the micro-enter-prise phase.

`I put Paul out on the road to get more businessand put someone else on the lorry, I had toscrew my suppliers if I was being screwed, Iscrewed my suppliers, got better deals, certainbetter deals, to be able to compete. We'regetting more volume so I'm getting a bettermargin now, so it's knock for knock . . .'(Owner-manager B)

Investigating expertise in managing growth (G2)

Table 5 synthesises the empirical evidence to pro-vide a summary of how ®ve factors potentially

in¯uence expertise in managing growth (G2):transferable support skills (F7); key employees(F10); family, `investing' friends etc (F9); activeprofessional advisers (F11) and transferable net-work of contacts (F8).

The owner-managers in cases A, B, F, G, J, L,M, N, O and P all appear to have had transfer-able support skills (F7) which helped provideexpertise in managing growth. For example, theowner-manager in case M had a methodicalapproach to administration because of his previoustraining at a large manufacturer of sunglasses.Cases D, J, K, M, N and P all seem to have hadhighly supportive employees (F10) who o�ereduseful assistance in achieving growth for the ®rm.The quote from owner-manager K illustrates thispoint well:

`There's one which is people here in the o�ceand Amanda, who is now a director of thecompany, the company wouldn't be where itwas without Amanda. There is absolutely nodoubt about that. She has an aptitude forbusiness and is astute and has all the criteriawhich I personally think are needed in tha t. . .'(Owner-manager K)

Table 4: Independent factors in¯uencing the interim growth driver owner's growth motivation (G1)

Owner's growth motivation (G1)

Independent factors Nature of in¯uence Case references

(F2) Desire to succeed * The owner-manager having a strong desire andwill to succeed and equating success with growth ofthe ®rm can be a positive in¯uence.* The owner-manager having modest expectationsfor the growth of the ®rm can be a negativein¯uence.* The owner-manager having a strong desire andwill to succeed but in directions that are contrary tothe growth of the ®rm can be a negative in¯uence.

E,F,G,H,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P

A,B,C,D,F,G

C,E

(F1) Desire to be 'one's ownboss' and (F3) Active risktaker.

* The owner-manager's desire for independence caneven sometimes combine with risk aversion to be apositive in¯uence.

L

(F9) Family, 'investing' friendsetc,

* Di�culties in the owner-manager's family lifea�ecting his/her motivation can be a negativein¯uence, eg the owner-manager going throughmarriage di�culties.

P

(F16) Competitive dynamics * Increasing competition may reduce margins andspur the owner-manager to increase volume so he/she can retain the same level of pro®ts.

B

Perren

375Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

Cases B, C, E, H, I, K and N all had family,`investing' friends (F9), active professional advisers(F11) or transferable network of contacts (F8) whoo�ered needed expertise in managing growth(G2). For example, the spouses of owner-managersH and I helped with the administration:

`My husband is prepared to do accounts on thekitchen table after a full-time job. You have tohave support at home otherwise it's impossible.'(Owner-manager H)

`My wife, she was looking after a lot of theadmin and day-to-day paper-work, which wasquite extensive and she was doing that . . .'(Owner-manager I)

Investigating resource access (G3)

Table 6 synthesises the empirical evidence toshow how resource access (G3) is potentiallyin¯uenced by seven factors: active risk taker(F3); debtors and creditors (F12); transferable

personal capital (F5); key employees (F10);family, `investing friends' (F9); transferable net-work of contacts (F8) and the state of the econ-omy (F14).

In all the cases the level of active risk taking(F3) was a key factor that conditioned if theowner-manager was willing to tap the sources ofphysical, material, ®nancial and intangibleresources necessary for starting and developing the®rm. The interaction of factors within an indivi-dual case can be quite complex. For example,owner-manager L relied on multiple sources. Heoriginally raised £10,000 through the sale of hismodel train collection (F5) and his father-in-law'sredundancy money (F9); later development wasfunded by pro®ts, extended credit from suppliers(F12) and a small overdraft facility (F12). Theinvolvement of the owner-manager's father-in-lawwas a vital resource in the early stages of develop-ment as the owner-manager was unwilling to riskgiving up the security of his job (F9, F3). In othercases resource access was in¯uenced by key

Table 5: Independent factors in¯uencing the interim growth driver expertise in managing growth (G2)

Expertise in managing growth (G2)

Independent factors Nature of in¯uence Case references

(F7) Transferable support skills * The owner-manager having management skillsdeveloped in previous employment which can helpset-up the infrastructure for growth can be a positivein¯uence.* The owner-manager not having managementskills developed in previous employment can be anegative in¯uence.

A,B,F,G,J,L,M,N,O,P

C,D,E,H,I,K

(F10) Key employees, partners etc * The ®rm employing or having access toindividuals who can o�er the owner-managersupport with the management of growth can be apositive in¯uence.* The ®rm employing unsuitable individuals to helpwith the management of growth can be a negativein¯uence.

D,J,K,M,N,P

H

(F9) Family, partner etc * The owner-manager's family o�ering the owner-manager support with the management of growthcan be a positive in¯uence.

B,C,H,I,N

(F11) Active professional advisers * The owner-manager having access to aprofessional adviser who o�ers help with themanagement of growth can be a positive in¯uence.

E,K

(F8) Transferable network ofcontacts

* The owner-manager having access to an adviserwho has set up a similar type of ®rm can be apositive in¯uence.

H

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

376 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

Table 6: Independent factors in¯uencing the interim growth driver resource access (G3)

Resource access (G3)

Independent factors Nature of in¯uence Case references

(F3) Active risk taker The level of active risk taking by the owner-manager determines how willing he/she is to tap the

various sources for obtaining resources necessary for

developing the ®rm.* The owner-manager being willing to accept

personal ®nancial risk to obtain resources can be a

positive in¯uence.* The owner-manager not being willing to accept

personal ®nancial risk can be a negative in¯uence.

A,B,C,E,F,G,H,I,J,M,N,O,P

D,K,L

(F12) Debtors and creditors * A supplier o�ering special terms of business can be

a positive in¯uence.* A supportive bank can be a positive in¯uence.

* Especially quick paying customers and good

debtor management can be positive in¯uence.* Poor debtor control can be a negative in¯uence.

* Cash based business with low stocks can be a

positive in¯uence.* A major bad debt can be a negative in¯uence.

A,E,F,G,I,J,L,M,N

B,E,F,G,H,J,K,M ,P

C,D,G,K,N

F

I,O

N

(F5) Transferable personal

capital

* The owner-manager possessing and being willing

to use his/her own personal capital to support thegrowth of the ®rm can be a positive in¯uence.

* The owner-manager being unwilling to use his/her

own personal capital to support the ®rm can be anegative in¯uence.

A,B,C,E,F,G,H,I,L,N,P

D,K

(F10) Key employees,

partners etc

* Employees providing lower cost or more

¯exibility than is normally available in the labour

market can be a positive in¯uence.* Problems with `key' employees can be a negative

in¯uence.

* Founding partner providing start-up ®nance

D,E,G,H,I,J,K,M,N,P

E,H

K

(F9) Family, `investing'

friends etc

* The owner-manager's family supplying ®nancial

support can be a positive in¯uence.

* The owner-manager's family supplying ¯exiblelabour can be a positive in¯uence.

A,H,L,N,P

B,C,E,G,H,I,L,N,P

(F8) Transferable network

of contacts

* The owner-manager's personal contact with a

supplier providing the bases of special terms of

business can be a positive in¯uence (in combinationwith factor 12).

* The owner-manager's personal contacts providing

access to some form of risk capital can be a positivein¯uence.

A,E,F,G,J,M,N,P

F,J,M

(F14) The state of the

economy and itsmanagement by

government,

* Speci®c legislation can have a negative in¯uence

on how ¯exibly the ®rm can use its resources.

G

Perren

377Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

employees, partners etc (F10), transferable networkof contacts (F8) and the state of the economy(F14). For example, owner-manager G hademployees who worked without wages for anextended period and even loaned money to helpthe business survive (F9). He also had supplier con-tacts who o�ered him chemicals and other essentialmaterials on very ¯exible terms with extendedcredit (F8, F12).

Investigating demand (G4)

Table 7 synthesises the empirical evidence to showthat demand (G4) is potentially in¯uenced by 11factors: the state of the economy (F14); productsector and market segments (F15); competitivedynamics (F16); transferable primary skills (F6);innovation (F4); active risk taker (F3); societal andother `outer' factors (F13); key employees, partnersetc (F10); transferable network of contacts (F8);desire to succeed (F2) and family, `investing'friends (F9).

Demand (G4), more than any of the otherinterim growth drivers, is in¯uenced by externalfactors which are largely outside the owner-manager's control: the state of the economy(F14), product sector and market segments (F15),competitive dynamics (F16) and societal andother `outer' factors (F13). While the cases showthat owner-managers can attempt to positiontheir ®rm as well as possible within the prevailingconditions, there is also evidence to show thatthere is an element of chance in how favourablethe conditions are for the business during itsdevelopment. Other demand (G4) in¯uencingfactors are much more determined by, or withinthe control of, the owner-manager: transferableprimary skills (F6), innovation (F4), active risktaker (F3), key employees, partners etc (F10),transferable network of contacts (F8), desire tosucceed (F2) and family, `investing' friends etc(F9).

Case N illustrates how the complex interactionof external factors and those factors more in thecontrol of the owner-manager combine to in¯u-ence demand (G4). From the outset the ®rmbene®ted from a period of expansion of theeconomy (F14) and the market being based on asingle tender system (F16). Demand was alsoencouraged by the owner-manager taking a riskon potentially low-price contracts (F3), his techni-cal and negotiating experience (F6) and his per-sonal network of contacts from his previousemployer's customer base (F8, F16).

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONSThe framework has provided a ¯exible structurethat contributes a clear agenda for analysing amicro-enterprise's growth, while allowing speci®cissues to be investigated within their environmen-tal context. It has enabled the host of factors thatmight a�ect the growth of micro-enterprises to beinvestigated.

Growth through a blend of factors

The cases reveal a clear pattern within the growthcategories. It appears that for a ®rm to achievegrowth beyond the micro-enterprise phase thecombined in¯uence of factors on all four of theinterim growth drivers must be positive. In theattempted growth cases it appears the initial in¯u-ence of the independent factors on all four interimgrowth drivers may well have been positive, butas the ®rm grew some of these switched to beingnegative.

All of the attempted growth cases experiencedsome problems with demand (G4), whereasresource access (G3) and owner's growth motiva-tion (G1) seemed far less problematic. Admittedly,as ®rms experienced development problems, theowner's growth motivation (G1) undertook a lessimportant role.

The non-growth ®rms all share negative own-er's growth motivation (G1), which is consistentwith the case selection criteria. Interestingly, casesB and D seem to enjoy a su�cient demand (G4)to warrant an attempt at growth and it appears tobe mainly the owner-manager's lack of growthmotivation (G1) which is restricting growth.

The non-growth ®rms A and C are in a di�er-ent situation. Not only does the owner-managerlack growth motivation (G1), but there alsoappears to be insu�cient demand (G4) to supportgrowth.

The cases reveal that an interim growth drivercan be in¯uenced by a number of di�erent factors.This introduces the possibility of `compensation',the phenomenon where a de®cit in one factor'sin¯uence against an interim growth driver may becounterbalanced by another factor's in¯uence. Theframework reveals possible ways that factors couldbe con®gured to compensate for a de®ciency inthe micro-enterprise's development needs.

The second part of this article (in the next edi-tion of JSBED) develops the managerial implica-tions of these ®ndings. It provides a checklist ofin¯uences for each of the interim growth drivers,highlights ways of `compensating' de®cits in parti-

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

378 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

Table 7: Independent factors in¯uencing the interim growth driver demand (G4)

Demand (G4)

Independent factors Nature of in¯uence Case references

(F14) The state of theeconomy and itsmanagement bygovernment

* The growth of the economy can be a positivein¯uence.* The decline of the economy is likely to be a negativein¯uence.* The decline of the economy may in very special casesbe a positive in¯uence.* Speci®c deregulation can be a positive in¯uence.

A,B,D,E,F,G,H,I,J,K,N,O,P

A,C,F,G,H,M,O,P

L

I

(F15) Product sectorand market segments

* The growth of the sector can be a positive in¯uenceand the decline of the sector can be a negative in¯uence.* Increasing concentration in the market can be anegative in¯uence.* Protection by a large customer can be a positivein¯uence.* Low opportunities for targeting speci®c niches can be anegative in¯uence.* Good opportunities for targeting speci®c niches can bea positive in¯uence.

A,D,E,F,G,H,I,J,K,M,N,P

A,C,F,G,H,M

B,M

D,E,G

L

(F16) Competitivedynamics

* The ®rm opening in an area with low competition canbe a positive in¯uence.* Appropriate targeting can be a positive in¯uence.* Inappropriate targeting or targeting too small a marketcan be a negative in¯uence.* Expansion or start-up requiring entry into geographicareas where larger ®rms are already established can be anegative in¯uence.* The ®rm being `protected' by `close' contacts withclients or suppliers can be a positive in¯uence.* The competition in a local area increasing can be anegative in¯uence.

H,I,J

E,K,L,PA,E,F,G

A,H,J

B,F,I,K,M,N,O

B,C

(F6) Transferableprimary skills

* The owner-manager's knowledge of the technicalaspects of the ®rm's core tasks developed prior to startingthe ®rm can be a positive in¯uence.* The owner-manager's skill at negotiating developedprior to starting the ®rm can be a positive in¯uence.* The owner-manager's lack of knowledge of thetechnical aspects of the ®rm's core tasks can be a negativein¯uence.

B,C,D,E,F,G,K,L,N,P

A,F,H,I,J,K,M,N,O,P

G

(F4) Innovation * The owner-manager actively searching for and able tospot market opportunities for the ®rm can be a positivein¯uence.* The owner-manager's lack of ability to search and spotmarket opportunities for the ®rm can be a negativein¯uence.

B,G,K,M,O,P

A,C,D,E,F,H,I,J,L

(F3) Active risk taker * The owner-manager being willing to accept the risk ofchallenging orders or opportunities can be a positivein¯uence.* The owner-manager being unwilling to accept risk ofchallenging orders or opportunities can be a negativein¯uence.

B,E,F,G,H,I,J,M,N,O,P

D,K,L

Perren

379Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

cular factors and suggests methods to help owner-managers (and advisers) to think creatively aboutdevelopment opportunities.

The framework starts to address Gibb andDavies's (1992) criticisms (that they do not con-sider how factors interact together) by showinghow independent factors blend together throughinterim growth drivers to in¯uence a ®rm's devel-opment. The patterns which exist in the growthdrivers are encouraging, but should be viewed inthe context of the individual cases. Other research-ers have suggested that the processes of growth are

so complex that they can appear almost accidental(eg Go�ee and Scase, 1995; Ram, 1997). Theframework provides a useful mechanism forsynthesising the data, but must be seen in the con-text of the complexity that occurs at the level ofeach case. Indeed, each case has an individualblend of factors in¯uencing its development. Forexample, a comparison of the factors that in¯u-enced the resource access of cases M and N (seeTable 6), both manufacturers who achievedgrowth, reveals a distinctive combination of ele-ments. Owner-manager M obtained ®nancial

Table 7: Continued

Demand (G4)

Independent factors Nature of in¯uence Case references

(F13) Societal andother `outer' factors

* Speci®c changes can have micro-level implicationswhich have a positive in¯uence eg increase in localpolicing of health laws can increase demand for relatedproducts (B13).* Speci®c changes can have micro-level implicationswhich have a negative in¯uence eg increase in awarenessof drink driving can decrease demand for car accidentrelated services (D13).* Speci®c demographic changes can have a positivein¯uence, eg large increase in local population of townwhere founding branch is located (J13).* Speci®c demographic changes can have a negativein¯uence, eg decline in area where branch is located(A13).* Technological developments by suppliers of coreproducts can have a positive in¯uence.

B,D,E,I,J,K,L,P

D

J

A

I,M

(F10) Key employees,partners etc

* Employees/partners with sales ability can be a positivein¯uence.* Problems with key sales employees can have a negativein¯uence.* Employees supplying core technical knowledge can bea positive in¯uence.* Employees leaving the ®rm and setting up incompetition can be a negative in¯uence.* Employees bringing contacts or expertise can be apositive in¯uence.

E,H,J,K,M

H

I

E

L,P

(F8) Transferablenetwork of contacts

* The owner-manager's personal customer contactspreviously established can be a positive in¯uence (links tofactor 16).

B,C,D,F,G,K,M,N,O,P

(F2) Desire to succeed * The owner-manager having a strong desire for the®rm to operate in a market that is contrary to marketneeds can be a negative in¯uence.

C,E

(F9) Family, `investing'friends etc

* Member of family with sales ability can be a positivein¯uence.

B

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

380 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

support from a business contact (F8) and a suppor-tive bank (F12), whereas, owner-manager N reliedon his personal capital (F5) and a £10,000 loanfrom his sister (F9).

The need to organise the complexity of evi-dence without losing its richness led to the variablefocus approach. At times, a broad view is takenwhen examining across cases, at other times aspotlight is thrown onto speci®c issues within acase but it is important to maintain a holistic per-spective, so that even when the attention is on thespeci®c it is seen within the context of the moregeneral. Equally, when the focus is on the moregeneral it needs to be remembered that its deriva-tion was from the speci®c. Some methodologistsspeak of `data reduction' (Miles and Huberman,1994), and to an extent this captures the notionbeing described, but misses the vital issue of levels.It suggests data loss, almost as if this is a require-ment to be able to understand. What is proposedhere is not data loss but a holistic view uniting thespeci®c with the general, with a clear audit trail ofhow one is connected to the other.

Further research of this type is needed. A mul-tiple case approach allows the idiosyncrasy of indi-vidual cases to be explored while allowing thetotal data to be analysed into some form of mean-ingful pattern (Chetty, 1996, provides a usefulexplanation of the application of case studymethod in a small ®rm context).

Growth through an evolution of factors

The existing integrative models (with the excep-tion of Davidsson, 1991 and Jennings and Beaver,1997) impose rather simplistic stages on the processof development. For example, Bygrave (1989)suggests a sequence of innovation, followed by atriggering event, which leads to implementationand ®nally growth. Gibb and Davies (1992) pro-pose a three-step process including assessing thebase performance, examining the base potentialand ®nally planning growth in a `conventionalbusiness plan format'. Kimberely et al. (1980) havepointed out there is no inevitable sequence ofstages in organisational life. This criticism is wellsupported by evidence from this research that sug-gests that development is often much more a pro-cess of slow incremental iterative adaptation toemerging situations, than it is a sequence of radicalclear steps or decision points.

By de®nition the non-growth and attempted-growth cases do not ®t with the pre-determinedgrowth stages, but even when the ®rms that

developed beyond the micro-enterprise phase areexamined such models are found lacking. Indeed,many of the cases started pursuing a particularmanner of development that failed and adaptationswere made. For example, case I had a number ofdevelopment directions that were aborted, but itstill went on to develop beyond the micro-enter-prise phase:

`We've had a couple of dismal failures. One wasthat we were persuaded by other people that weshould open up a cubicle o�ce in Linkton[name of distant town] and put somebody indown there. That was a dismal failure becauseLinkton and Cranston [name of town wheremain branch is] are 90 miles apart and I wasgoing down there twice a week, trying to holdthe thing together and get it going, andcouldn't do so . . . One of the things that Iwanted to do about two years ago was to takesome of the workload from me on the adminside . . . so we were approached by a local guywho had a few bob and the arrangement wasthat he would look after the total admin and dothe whole thing. It never worked . . .' (Owner-manager I's chronicle)

Models based on stages can be persuasive, asStanworth and Curran (1976) pointed out; at asuper®cial level they `contain a considerable ele-ment of truth', they ®t with anecdotal real-lifeexamples and provide a simple framework forconceptualisation. As the current research shows,however, when the detailed history of a ®rm isinvestigated and compared with the simplicity ofthese frameworks, they are often found wanting.

Davidsson (1991), Jennings and Beaver (1997),and the framework developed from this researchare less open to criticism as they do not imposesimplistic stages onto a complex reality but theydo not fully address Gibb and Davies's (1992) criti-cism of existing models, including their own, thatthey miss the complex temporal process of factorinteraction. The cases from this research supportthe importance of this temporal view, showingthat even when cases are in¯uenced by a similarfactor this may occur at very di�erent times in thehistory of development. For example, cases B andM both bene®ted from the protection of a largecustomer (F15) (see Table 7), but in case B thisoccurred at start-up, whereas, in case M it waslater in the development of the ®rm. The caseshere suggest that further research should focus on

Perren

381Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

the timing of factor events, perhaps employing theframework with some form of time-orderedmatrix will reveal `underlying processes or ¯ows'(Miles and Huberman, 1994).

Growth through tailored and timely support

This research has revealed complex patterns in theinteraction between the independent factors andthe interim growth drivers. This con®rms theneed for tailored and timely support to be o�eredto micro-enterprises, rather than any form of stan-dard supply-side policies which will be wastefuland not address real needs. It would be inappropri-ate if the framework was used in an overly pre-scriptive way, with the owner-manager beinginstructed as to how the business should be run.There is a risk of such directive approaches result-ing in alienation of the owner-manager and inap-propriate formalistic techniques being appliedwithout su�cient adaptation to the ®rm's speci®ccontext. Perhaps more importantly, suchapproaches do not empower or develop theowner-manager, but simply address a speci®c pro-blem. This may leave the owner feeling less con®-dent and in a dependent relationship with theexternal adviser. What is needed is support that isowner-manager centred, rather than adviser-centred. Some form of participatory action(Reason, 1994) may be appropriate, where a coun-sellor uses the framework with the owner-man-ager to try and understand the ®rm's currentsituation and to develop growth strategies for thefuture.

The agenda provides a useful mechanism forsensitising owner-managers and advisers to issues,but it would be premature to recommend its useas any form of predictive tool for `picking win-ners' without further research; especially with therisk of temporal distortion identi®ed above. `Pick-ing winners' has important policy implications,but it has eluded small ®rm researchers and policyadvisers for decades (Hakim, 1989; Storey, 1993).The framework would be better employed at thisstage as an agenda to support micro-enterprises,rather than a mechanism to exclude some ®rmsfrom support.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe author is grateful to Professor Aidan Berry,Professor John Bessant, Professor Robert Black-burn, Professor Tom Bourner, Peter Hovell,Barry Le Scherer, Dr. David Paskins, ProfessorMonder Ram, Professor Adrian Woods and the

anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedbackon this research.

NOTES(1) European Commission has de®ned micro-

enterprises as ®rms with fewer than tenemployees (Stanworth and Gray, 1991). Theterm is now accepted by the small businessresearch community; for example, Robertson(1994) and Storey (1994) have both referredto micro-enterprises. For this research gra-dual growth is de®ned as taking four yearsor more to grow beyond the micro-enter-prise phase.

(2) Some of the discussions of methodology anddata analysis have the bene®t of hindsightand have been stimulated by the reviewers'helpful comments.

(3) An intervening factor emerges as a functionof an independent factor(s) acting in a givensituation, `and helps to conceptualise andexplain the in¯uence of the independent' fac-tor(s) on the dependent factor (Sekaran,1992, p. 70).

(4) The initial list is essentially a conveniencesample that was then re®ned through a formof theoretical or dimensional sampling(Eisenhardt, 1989; Cohen and Manion, 1994).While the list is a convenience sample andthere is no intended statistical signi®cance, itis with hindsight perhaps worth noting forcompleteness that one of the ®rms o�eringaccountancy services included some prospec-tive clients, others only provided a partial listof their clients. However, there were alsofour pilot cases.

(5) The `random' selection of the cases was felt tobe important in the original research design,but with hindsight it is not that important asthe theoretical sample (Eisenhardt, 1989) wasafter all based on a non-probability conveni-ence sample of ®rms (Cohen and Manion,1994). Convenience samples of this type havethe advantage of giving access, but there canbe issues of researcher re¯exivity, researcherbias and protecting anonymity. To reducethese e�ects the paradigmatic lens of an `out-side observer's account' (Cohen and Manion,1994, p. 228) is adopted. This focuses on the`formally' collected data, with sampling, datacollection and data interpretation presented astransparently as the constraints of protectinganonymity will allow (Miles and Huberman,

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

382 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

1994). In this way the reader is empowered tochallenge the researcher's interpretations.There are still potential re¯exivity and biasissues between the researcher and cases, butthe reliance on `formally' collected data and itshistoric nature empowers the reader to act as amediator and to reduce such e�ects.

(6) A coherent and structured approach to datacollection and analysis was adopted for theoral accounts of each owner-manager's life,the semi-structured interviews and the analy-sis of secondary sources. A less structured andmore passive approach was taken to the con-tact and data collection for the intervening 6to 30-month `observation' phase. The datacollection methods for the `observation'phase varied between ®rms but mightinclude such measures as visits, telephoneinterviews and face-to-face interviews withother people associated with the business. Inthe original research design it was arguedthat a passive approach was needed duringthis period to reduce the researcher's in¯u-ence on the ®rms and to ensure the owner-manager did not feel he/she was being cross-checked. The less structured data obtainedduring the `observation' phase has provedless useful than the structured data. In hind-sight, since these are essentially historic casestudies then the emphasis on a passiveapproach was probably not needed and amore structured approach in the interimperiod would have been preferable.

(7) This method of analysis was felt to be mostappropriate for understanding the factorsin¯uencing growth, but other methods ofanalysis have been employed on the samedata to expore other issues of interest.

(8) The autobiographic interview, after beingfully transcribed, was suitably summarised togive a chronological account in the owner-manager's own words. The summary's keypoints had been agreed later in the autobio-graphic interviews with the owner-manager.

(9) This is not suggesting that de®nitive causa-tion can be established, rather the investiga-tion has moved beyond simple correlationspotting to explore the processes that are atwork and to suggest patterns of causationbased on evidence.

(10) Chell et al. (1991) provides a helpful reviewof the literature on the psychology of entre-preneurship.

(11) For ease of presentation, in some cases thenumber of employees has been approximatedor the reading given that was nearest to theages of the ®rm in the table.

REFERENCESAndrews, K. R. (1980) The Concept of Corporate Strat-

egy, Irwin, Homewood, Illinois.Bell, J. (1987) Doing Your Research Project, Open Uni-

versity Press, Milton Keynes.Birley, S. and Westhead, P. (1990) Growth and perfor-

mance contrasts between types of small ®rms,Strategic Management Journal, 11, 535±57.

Blackburn, R. A., Curran, J. and Jarvis, R. (1990)`Small ®rms and local networks: some theoreticaland conceptual explorations', paper presented tothe 13th Small National Firms' Policy andResearch Conference.

Blackburn, R. A., Curran, J. and Woods, A. (1992)`Exploring enterprise cultures: small service sectorenterprise owners and their views', in M. Robert-son, E. Chell and C. Mason (eds) Towards theTwenty-First Century: The Challenge for Small Busi-ness, Nadamal Books, Maccles®eld.

Bolton, J. E. (1971) Small Firms Ð Report of the Com-mittee of Inquiry on Small Firms, Cmnd. 4811,HMSO, London.

Bosworth, D. and Jacobs, C. (1989) `Management atti-tudes, behaviour, and abilities as barriers togrowth', in J. Barber, J.S. Metcalf and M. Porte-ous (eds) Barriers to Growth In Small Firms, Rou-tledge, London.

Box, T. M., White, M. A. and Barr, S. H. (1993) `Acontingency model of new manufacturing perfor-mance', Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(2),31±45.

Brockhaus, R. H. and Horwitz, P. S. (1986) `The psy-chology of the entrepreneur', in D.L Sexton andR.W. Smith (eds) The Art and Science of Entrepre-neurship, Ballinger, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Bygrave, W. D. (1989) `The entrepreneurship para-digm (1): a philosophical look at its researchmethodology', Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,14(1), 7±26.

Caird, S. (1990) `What does it mean to be enterpris-ing', British Journal of Management, 1(3), pp. 137±145.

Cambridge Small Business Research (1992) The State ofBritish Enterprise, Department of Applied Eco-nomics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Chell, E., Haworth, J. and Brearley, S. (1991) TheEntrepreneurial Personality, Routledge, London.

Chetty, S. (1996) `The case study method for researchin small and medium sized ®rms', InternationalSmall Business Journal, 15(57), 73±85.

Cohen, L. and Manion, L. (1994) Research Methods inEducation, Routledge, London.

Perren

383Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

Covin, J. G. and Slevin, D. P. (1991) `A conceptualmodel of entrepreneurship as ®rm behavior',Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7±25.

Covin, J. G. and Slevin, D. P. (1993) `A response toZahra's critique and extension of the Covin±Slevin entrepreneurial model', EntrepreneurshipTheory and Practice, 17(4), 23±28.

Cragg, P. B. and King, M. (1988) `Organizational char-acteristics and small ®rms' performance revisited',Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 13(2), 49±64.

Curran, J. and Burrows, R. (1993) `Shifting the focus:problems and approaches in studying the smallenterprise in the service sector', in R. Atkin, E.Chell and C. Mason (eds) New Directions in SmallBusiness Research, Avery, Aldershot.

Davidsson, P. (1991) `Continued entrepreneurship: abil-ity, need, and opportunity as determinants ofsmall ®rm growth', Journal of Business Venturing,6, 405±429.

Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W. M. and Ferrell, O. C.(1994) Marketing: Concepts and Strategies,Houghton Mi�in, Boston, Massachusetts.

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. and Lowe, A. (1991)Management Research: An Introduction, Sage,London.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989) `Building theories from casestudy research', Academy of Management Review,14(4), 532±150.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1991) `Better stories and better Con-structs: The case for rigour and comparativelogic', Academy of Management Review, 16(3),620±627.

Fahey, L. and Narayanan, V. K. (1986) Macro-environ-mental Analysis For Strategic Management, West, StPaul, Minneapolis.

Gibb, A. A. and Davies, L. (1992) `Development of agrowth model', The Journal of Entrepreneurship,1(1), 3±36.

Gibb, A. A. and Scott, M. G. (1985) `Strategic aware-ness, personal commitment and the process ofplanning in the small business', Journal of Manage-ment Studies, 22(6), 597±632.

Gill, J. (1985) Factors A�ecting the Survival and Growth ofthe Smaller Company, Gower, Aldershot.

Go�ee, R. and Scase, R. (1995) Corporate Realities: TheDynamics of Large and Small Organisations, Routle-dge, London.

Goss, D. (1991) Small Business and Society, Routledge,London.

Hakim, C. (1989) `Identifying fast growth small ®rms',Employment Gazette, January, 29±41.

Hassid, J. (1977) `Diversi®cation and the ®rm's rate ofgrowth', Manchester School, 45, 16±28, reported inD. A. Hay and D. J. Morris (1991) Industrial Eco-nomics and Organisation: Theory and Evidence,Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Hofer, C. W. and Charan, R. (1984) `The transition to

professional management: mission impossible?',American Journal of Small Business, IX(1), 1±11.

Jennings, P. and Beaver, G. (1997) `The performanceand competitive advantage of small ®rms: a man-agement perspective', International Small BusinessJournal, 15(2), 63±75.

Johannisson, B. (1986) `Network strategies: manage-ment of technology for entrepreneurship andchange', International Small Business Journal, 5(1),19±30.

Johnson, B. R. (1990) `Toward a multidimensionalmodel of entrepreneurship: the case for achieve-ment motivation and the entrepreneur', Entrepre-neurship Theory and Practice, 14(3), 39±54.

Joyce, P., Woods, A., McNulty, T. and Corrigan, P.(1990) `Barriers to change in small businesses',International Small Business Journal, 8(4), 49±58.

Keats, B. W. and Bracker, J. S. (1988) `Toward atheory of small ®rm performance: a conceptualmodel', American Journal of Small Business, 12(4),41±58.

Keeble, D., Walker, S. and Robson, M. (1993) NewFirm Formation and Small Business Growth in theUnited Kingdom: Spatial and Temporal Variationsand Determinants, Employment Department,Research Series No. 15, University of Cambridge,Cambridge.

Kimberely, J. R. and Miles Associates (1980) The Organ-isational Life Cycle, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Kurilo�, A. H., Hemphill, J. M. and Cloud, D. (1993)Starting and Managing the Small Business, McGrawHill, New York.

Lean, J. and Chaston, I. (1995) `Critical in¯uences uponthe growth performance of post start-up microbusinesses: evidence from Devon and Cornwall',paper presented to the Small Business and Enter-prise Development Conference.

Mason, C. and Harrison, R. (1994) `Informal venturecapital in the UK', in A. Hughes and D. J. Storey(eds) Finance and the Small Firm, Routledge,London.

McCelland, D. C. (1961) The Achieving Society, VanNostrand, Princeton, New Jersey.

Merz, G. R., Weber, P. B. and Laetz, V. B. (1994)`Linking small business management with entre-preneurial growth', Journal of Small Business Man-agement, 32(4), 48±60.

Miles, M. B. and Huberman, A. M. (1994) `Data man-agement and analysis methods', in N. K. Denzinand Y. S. Lincoln (eds) Handbook of QualitativeResearch, Sage, Thousand Oaks, California.

Moore, C. F. (1986) `Understanding entrepreneurialbehaviour', in J. A. Pearce II, and R. B. Robinson(eds) Academy of Management Best Papers Proceed-ings. 46th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Man-agement, Chicago.

Na�ziger, D. W., Hornsby, J. S. and Kuratko, D. F.

Factors in the growth of micro-enterprises (Part 1): Developing a framework

384 Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

(1994) `A proposed research model of entrepre-neurial motivation', Entrepreneurship Theory andPractice, 18(3), 9±42.

Penrose, E. T. (1959) The Theory of the Growth of TheFirm, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Perren L. (1996) The Development of Micro-enterprises,unpublished PhD thesis, University of Brighton.

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive Strategy: Techniques forAnalyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press,New York.

Ram, M. (1997) `Professionals at work Ð transition ina small service ®rm', paper presented at 20thISBA National Small Firms Policy and ResearchConference, Belfast.

Ray, G. H. and Hutchinson, P. J. (1983) The Financingand Financial Control of Small Enterprise Develop-ment, Gower, London.

Reason, P. (1994) `Three approaches to participativeinquiry', in N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds)Handbook of Qualitative Research, Sage, ThousandOaks, California.

Riley, J. (1990) Getting the Most From Your Data, Tech-nical and Educational Services Ltd, Bristol.

Robertson, M. (1987) `The great mismatch', paperpresented to the 10th National Small Firms Con-ference.

Robertson, M. (1994) `Strategic issues impacting onsmall ®rms: their promise, their role, their pro-blems and vulnerability, their future and the wayforward', paper presented to the 17th NationalSmall Firms' Policy and Research Conference.

Rothwell, R. and Zegveld, W. (1982) Innovation andthe Small and Medium-sized Firm, Frances Pinter,London.

Scase, R. and Go�ee, R. (1980) The Real World of theSmall Business Owner, Croom Helm, London.

Schumpeter, J. (1934) The Theory of Economic Develop-ment, Harvard University Press, reported in A. A.Gibb and L. Davies (1992) Development of agrowth model, The Journal of Entrepreneurship,1(1), 3±36.

Sekaran, U. (1992) Research Methods for Business: A SkillBuilding Approach, Wiley, Chichester.

Slatter, S. (1992) Gambling on Growth: How to Managethe Small High-Tech Firm, Wiley, Chichester.

Small Business Research Trust (1984±1996) Small Busi-ness Research Trust: Quarterly Survey of Small Firmsin Britain, Small Business Research Trust.

Stanworth, J. and Curran, J. (1976) `Growth and thesmall ®rm Ð an alternative view', Journal of Man-agement Studies, 13(2), 7 and 96±110.

Stanworth, J. and Curran, J. (1986) `Growth and thesmall ®rm', in J. Curran, J. Stanworth and D.Watkins (eds) The Survival of the Small Firm,Volume 2, Gower, Aldershot.

Stanworth, J. and Gray, C. (eds) (1991) Bolton 20 yearsOn: The Small Firm in the 1990s, Paul ChapmanPublishing, London.

Steinho�, D. and Burgess, J. (1993) Small Business Man-agement Fundamentals, McGraw Hill, New York.

Storey, D. J. (1993) `Should we abandon support tostart-up businesses?' in F. Chittenden, M. Robert-son and D. Watkins (eds) Small Firms Recessionand Recovery, Paul Chapman Publishing, London.

Storey, D. J. (1994) Understanding the Small Firm Sector,Routledge, London.

Timmons, J. A., Smollen, L. E. and Dingee, A. L. M.(1985) New Venture Creation, Irwin, Homewood,Illinois.

Williamson, O. E. (1967) `Hierarchical control andoptimum ®rm size', The Journal of Political Econ-omy, 75(2), 123±138.

Yin, R. K. (1993) Applications of Case Study Research,Sage, Newbury Park, California.

Zahra, S. A. (1993) `A conceptual model of entrepre-neurship as ®rm behavior: a critique and exten-sion', Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(4),5±21.

Dr Lew Perren, Small Business Research Unit,

Brighton Business School, University of Brighton.

Perren

385Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development