Extract Pages From Marketing-strategy - WM P2

-

Upload

phuong-pham -

Category

Documents

-

view

234 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Extract Pages From Marketing-strategy - WM P2

Understanding MarketOpportunities

Cellular Telephone Business: Increasing

~~~ompetition in a Growing Market1

From London to Tokyo to Chicago, cell phoneshave become a "can’t do without it" tool of time-pressed business people, hip teenagers, and justabout anyone else who wants to stay in touch. Themarket for mobile telephone service is growingrapidly. In 1983, when the first cellular phone sys-tem began operations, it was projected that by2000, fewer than one million people would sub-scribe. As a result of dramatic growth among bothbusiness and household users, however, by 2002,the number of cell phone users had reached morethan 1 billion worldwide! In Finland and Taiwan,the number of cell phone subscribers is higher thanthe total population of the country; and HongKong is expected to join them soon.

The continuing growth in demand for mobiletelephone services generates numerous opportuni-ties in the cell phone manufacturing and cell phoneservice industries, among others. Prospective en-trants and current players considering additional in-vestments should consider, however, just how at-tractive these markets and industries really are.

The Mobile Telephony Market

By all accounts, the market for mobile telephony isan attractive one. In 2003, cell phone sales hit 500million units worldwide, surpassing analysts’ mostoptimistic projections. New features such as colorscreens, built-in cameras, and Web browsers haveattracted new users and encouraged existing usersto upgrade their phones. As a result, cell phonepenetration in 2003 exceeded 70 percent in Eu-

rope and surpassed 50 percent in North America,up from 44 percent in 2001. With this kind ofgrowth and widespread penetration, most ob-servers would agree that the market for cell phoneservice and cell phones themselves is attractive in-deed. But how attractive are the industries thatserve this market?

Cell Phone Manufacturing

Rapid-fire technological advances from Qualcomm,Ericsson, Nokia, and others have brought countlessnew features to the market, including software toaccess the World Wide Web, the ability to sendand receive photographic images, and variouslocation-based services that take advantage ofglobal positioning technology. In Europe, newphones enable mobile users to check the weatherforecast, their e-mail, stock quotes, and more. Fin-land’s Nokia has rocketed to world leadership incell phones, leaving early and Iongtime leader Mo-torola in the dust. From year to year, market sharefigures for leading cell phone manufacturers candouble or be halved, depending on whose latesttechnology catches the fancy of users. To investors’joy or dismay, stock prices follow suit. Qualcomm’sshares soared 2,600 percent in 1999, only to fallback by more than 60 percent by mid-2000, and afurther 50 percent by mid-2002. Nokia, too, sawits share price tumble in 2001. By mid-2004,Nokia’s stock reached a five-year low.

This recent history in the hotly competitive cellphone manufacturing industry suggests that a

Understanding MarketOpportunities

Cellular Telephone Business: Increasing

~~~ompetition in a Growing Market1

From London to Tokyo to Chicago, cell phoneshave become a "can’t do without it" tool of time-pressed business people, hip teenagers, and justabout anyone else who wants to stay in touch. Themarket for mobile telephone service is growingrapidly. In 1983, when the first cellular phone sys-tem began operations, it was projected that by2000, fewer than one million people would sub-scribe. As a result of dramatic growth among bothbusiness and household users, however, by 2002,the number of cell phone users had reached morethan 1 billion worldwide! In Finland and Taiwan,the number of cell phone subscribers is higher thanthe total population of the country; and HongKong is expected to join them soon.

The continuing growth in demand for mobiletelephone services generates numerous opportuni-ties in the cell phone manufacturing and cell phoneservice industries, among others. Prospective en-trants and current players considering additional in-vestments should consider, however, just how at-tractive these markets and industries really are.

The Mobile Telephony Market

By all accounts, the market for mobile telephony isan attractive one. In 2003, cell phone sales hit 500million units worldwide, surpassing analysts’ mostoptimistic projections. New features such as colorscreens, built-in cameras, and Web browsers haveattracted new users and encouraged existing usersto upgrade their phones. As a result, cell phonepenetration in 2003 exceeded 70 percent in Eu-

rope and surpassed 50 percent in North America,up from 44 percent in 2001. With this kind ofgrowth and widespread penetration, most ob-servers would agree that the market for cell phoneservice and cell phones themselves is attractive in-deed. But how attractive are the industries thatserve this market?

Cell Phone Manufacturing

Rapid-fire technological advances from Qualcomm,Ericsson, Nokia, and others have brought countlessnew features to the market, including software toaccess the World Wide Web, the ability to sendand receive photographic images, and variouslocation-based services that take advantage ofglobal positioning technology. In Europe, newphones enable mobile users to check the weatherforecast, their e-mail, stock quotes, and more. Fin-land’s Nokia has rocketed to world leadership incell phones, leaving early and Iongtime leader Mo-torola in the dust. From year to year, market sharefigures for leading cell phone manufacturers candouble or be halved, depending on whose latesttechnology catches the fancy of users. To investors’joy or dismay, stock prices follow suit. Qualcomm’sshares soared 2,600 percent in 1999, only to fallback by more than 60 percent by mid-2000, and afurther 50 percent by mid-2002. Nokia, too, sawits share price tumble in 2001. By mid-2004,Nokia’s stock reached a five-year low.

This recent history in the hotly competitive cellphone manufacturing industry suggests that a

86 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

rapidly growing market does not necessarily pro-vide a smooth path to success. Growing marketsare one thing, but turbulent industries servingthose markets are quite another.

Cell Phone Service Providers

O Industry conditions for service providershave run wild as well. The race to winglobal coverage has led to mergers of

large players such as Europe’s Vodafone withAmerica’s AirTouch in 1999. Vodafone did not stopthere, however, going on to acquire Germany’sMannesmann in 2000. Other marketers with well-known brands have also jumped into the fray.Richard Branson’s Virgin Group bought idle capac-ity from a British also-ran and launched Virgin Tele-com, picking up 150,000 customers in his firstsix weeks. All over Europe, market-by-market bat-tles for market share have raged. Prices for cell

phone service have slid, given the competitive pres-sures. To make matters worse, the cost of obtain-ing new government licenses to support new third-generation (3G) services has skyrocketed. Britain’sauction in early 2000 of 3G licenses wound up rais-ing some $35 billion in license fees, roughly 10times what was expected. Other European govern-ments took notice and followed in the U.K.’s path,and operators eventually shelled out more than~100 billion in license fees.

Unfortunately for operators, however, 3G tech-nology proved harder to implement and more dif-ficult to sell than was expected. The result? Massivewrite-downs of 3G investments, a whopping 10billion for European wireless operator mm02 alone.

Thus, while the rapidly growing market for mo-bile telephone service is clearly an attractive one,the industries that serve this market are quite an-other story.

STRATEGIC CHALLENGES ADDRESSED IN CHAPTER 4

Strategic IssueHow attractive is themarket we serve or pro-

pose to serve? Howattractive is the industryin which we wouldcompete? Are the rightresources--in terms ofpeople and their capabili-ties and comlections--in place to effectivelypursue the opportunityat hand?

As the examples of the cellular phone manufacturing and service industries show, servinga growing market hardly guarantees smooth sailing. Equally or more important are indus-try conditions and the degree to which specific players in the industry can establish andsustain competitive advantage. Thus, as entrepreneurs and marketing decision makers pon-der an opportunity to enter or attempt to increase their share of a growing market like thatfor mobile phones, they also must carefully examine a host of other issues, including theconditions that are currently prevailing in the industry in which they would compete andthe likelihood that favorable conditions will prevail in the future. Similarly, such decisionsrequire that a thorough examination of trends that are influencing market demand and arelikely to do so in the future, whether favorably or otherwise, is required.

Thus, in this chapter, we address the 4 Cs that were identified in Chapter 1 as the ana-lytical foundation of the marketing management process. We provide a framework to helpmanagers, entrepreneurs, and investors comprehensively assess the atn’activeness of op-portunities they encounter, in terms of the company and its people, the environmental con-text in which it operates, the competition it faces, and the wants and needs of the customerit seeks to serve. We do so by addressing the tl’uee questions crucial to the assessment ofany market opportunity: How attractive is the market we serve or propose to serve? Howattractive is the industry in which we would compete? Are the right resources--in terms ofpeople and their capabilities and connections--in place to effectively pursue the opportu-nity at hand?

We frame our discussion of opportunity assessment using the seven domains shown inExhibit 4.1. As the seven domains framework suggests and the cellular telephony storyshows, in today’s rapidly changing and hotly competitive world it’s not enough to have alarge and growing market. The attractiveness of the industry and the company’s or entre-preneurial team’s resources are equally important. Before digging more deeply into theframework, however, we clarify the difference between two oft-confused terms: marketand industry.

~:XI!IBIT 4.1The Seven Domains

of Attractive

Opportunities

Solnre: Mullins, John, Newtlusi#ess Roadtest: What

preneurs and Executives Shonld

Do, 1st Edition, ©N/A.Reprinted by permission ofPearson Education, Inc., UpperSaddle River, NJ.

. i:t’ategic IssueMarkets are comprisedof buyers; industries arecomprised of sellers.

Macro

Level

MicroLevel

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities

Market Domains Industry Domains

T~~ ble Advanlagea ~ct Attracti,,eness "

87

D INDUSTRIES: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

We define a market as being comprised of individuals and organizations who are interested

and willing to buy a good or service to obtain benefits that will satisfy a particular need or

waut and who have the resources to engage in such a transaction. One such market con-

sists of college students who get hungry in the middle of the afternoon and have a few min-

utes and enough spare change to buy a snack between classes.

An industry is a group of firms that offer a product or class of products that are similar

and are close substitutes for one another. What industries serve the student snack market?

At the producer level, there are the salty snack industry (makers of potato and corn chips

and similar products); the candy industry; the fi’esh produce industry (growers of apples,

oranges, bananas, and other easy-to-eat fruits); and others too nnmerous to mention. Dis-

tribution channels for these products include the supermarket industry, the food service in-

dustry, the coin-operated vending industry, and so on. Clearly, these industries ate differ-

ent and offer varying bundles of benefits to hungry students.

Thus, markets are comprised of buyers; industries are comprised of sellers. The dis-

tinction is an important one because industries can vary substantially in their attractiveness

and overall profitability.

Sellers who look only to others in their own industry as competitors are likely to over-look other very real rivals and risk having their markets undercut by innovators from other

industries. Should Kodak be more concerned with Fuji, Agfa, and other longtime players

in the film and photoprocessing industries, or should it be worrying about Hewlett-

Packard, Sony, and others whose digital tecb3mlogies may make photography’s century-old

silver halide chemistry go the way of the buggy whip? With unit sales of digital camerasnow outstripping sales in the United States of cameras that use film, Kodak’s competitive

landscape has certainly changed.-’

86 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

rapidly growing market does not necessarily pro-vide a smooth path to success. Growing marketsare one thing, but turbulent industries servingthose markets are quite another.

Cell Phone Service Providers

O Industry conditions for service providershave run wild as well. The race to winglobal coverage has led to mergers of

large players such as Europe’s Vodafone withAmerica’s AirTouch in 1999. Vodafone did not stopthere, however, going on to acquire Germany’sMannesmann in 2000. Other marketers with well-known brands have also jumped into the fray.Richard Branson’s Virgin Group bought idle capac-ity from a British also-ran and launched Virgin Tele-com, picking up 150,000 customers in his firstsix weeks. All over Europe, market-by-market bat-tles for market share have raged. Prices for cell

phone service have slid, given the competitive pres-sures. To make matters worse, the cost of obtain-ing new government licenses to support new third-generation (3G) services has skyrocketed. Britain’sauction in early 2000 of 3G licenses wound up rais-ing some $35 billion in license fees, roughly 10times what was expected. Other European govern-ments took notice and followed in the U.K.’s path,and operators eventually shelled out more than~100 billion in license fees.

Unfortunately for operators, however, 3G tech-nology proved harder to implement and more dif-ficult to sell than was expected. The result? Massivewrite-downs of 3G investments, a whopping 10billion for European wireless operator mm02 alone.

Thus, while the rapidly growing market for mo-bile telephone service is clearly an attractive one,the industries that serve this market are quite an-other story.

STRATEGIC CHALLENGES ADDRESSED IN CHAPTER 4

Strategic IssueHow attractive is themarket we serve or pro-

pose to serve? Howattractive is the industryin which we wouldcompete? Are the rightresources--in terms ofpeople and their capabili-ties and comlections--in place to effectivelypursue the opportunityat hand?

As the examples of the cellular phone manufacturing and service industries show, servinga growing market hardly guarantees smooth sailing. Equally or more important are indus-try conditions and the degree to which specific players in the industry can establish andsustain competitive advantage. Thus, as entrepreneurs and marketing decision makers pon-der an opportunity to enter or attempt to increase their share of a growing market like thatfor mobile phones, they also must carefully examine a host of other issues, including theconditions that are currently prevailing in the industry in which they would compete andthe likelihood that favorable conditions will prevail in the future. Similarly, such decisionsrequire that a thorough examination of trends that are influencing market demand and arelikely to do so in the future, whether favorably or otherwise, is required.

Thus, in this chapter, we address the 4 Cs that were identified in Chapter 1 as the ana-lytical foundation of the marketing management process. We provide a framework to helpmanagers, entrepreneurs, and investors comprehensively assess the atn’activeness of op-portunities they encounter, in terms of the company and its people, the environmental con-text in which it operates, the competition it faces, and the wants and needs of the customerit seeks to serve. We do so by addressing the tl’uee questions crucial to the assessment ofany market opportunity: How attractive is the market we serve or propose to serve? Howattractive is the industry in which we would compete? Are the right resources--in terms ofpeople and their capabilities and connections--in place to effectively pursue the opportu-nity at hand?

We frame our discussion of opportunity assessment using the seven domains shown inExhibit 4.1. As the seven domains framework suggests and the cellular telephony storyshows, in today’s rapidly changing and hotly competitive world it’s not enough to have alarge and growing market. The attractiveness of the industry and the company’s or entre-preneurial team’s resources are equally important. Before digging more deeply into theframework, however, we clarify the difference between two oft-confused terms: marketand industry.

~:XI!IBIT 4.1The Seven Domains

of Attractive

Opportunities

Solnre: Mullins, John, Newtlusi#ess Roadtest: What

preneurs and Executives Shonld

Do, 1st Edition, ©N/A.Reprinted by permission ofPearson Education, Inc., UpperSaddle River, NJ.

. i:t’ategic IssueMarkets are comprisedof buyers; industries arecomprised of sellers.

Macro

Level

MicroLevel

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities

Market Domains Industry Domains

T~~ ble Advanlagea ~ct Attracti,,eness "

87

D INDUSTRIES: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

We define a market as being comprised of individuals and organizations who are interested

and willing to buy a good or service to obtain benefits that will satisfy a particular need or

waut and who have the resources to engage in such a transaction. One such market con-

sists of college students who get hungry in the middle of the afternoon and have a few min-

utes and enough spare change to buy a snack between classes.

An industry is a group of firms that offer a product or class of products that are similar

and are close substitutes for one another. What industries serve the student snack market?

At the producer level, there are the salty snack industry (makers of potato and corn chips

and similar products); the candy industry; the fi’esh produce industry (growers of apples,

oranges, bananas, and other easy-to-eat fruits); and others too nnmerous to mention. Dis-

tribution channels for these products include the supermarket industry, the food service in-

dustry, the coin-operated vending industry, and so on. Clearly, these industries ate differ-

ent and offer varying bundles of benefits to hungry students.

Thus, markets are comprised of buyers; industries are comprised of sellers. The dis-

tinction is an important one because industries can vary substantially in their attractiveness

and overall profitability.

Sellers who look only to others in their own industry as competitors are likely to over-look other very real rivals and risk having their markets undercut by innovators from other

industries. Should Kodak be more concerned with Fuji, Agfa, and other longtime players

in the film and photoprocessing industries, or should it be worrying about Hewlett-

Packard, Sony, and others whose digital tecb3mlogies may make photography’s century-old

silver halide chemistry go the way of the buggy whip? With unit sales of digital camerasnow outstripping sales in the United States of cameras that use film, Kodak’s competitive

landscape has certainly changed.-’

88 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

ASSESSING MARKET AND INDUSTRY ATTRACTIVENESS

As Exhibit 4.1 shows, markets and industries must be assessed at both the macro and microlevels of analysis. But what do these levels really mean? On both the market and industrysides, the macro-level analyses are based on environmental conditions that affect the mar-ket or industry, respectively, as a whole, without regard to a particular company’s strategyor its role in its industry. These external and largely uncontrollable forces or conditionsmust be reckoned with in assessing and shaping any opportunity, and indeed, in develop-ing any coherent marketing strategy.

At the micro level, the analyses look not at the market or the industry overall but at in-dividuals that comprise the market or industry, that is, specific target customers and com-panies themselves, respectively. We develop and apply the relevant analytical frameworksfor the macro-level analyses first; then we address the micro-level analyses.

MACRO TREND ANALYSIS: A FRAMEWORK FOR ASSESSING MARKET

ATTRACTIVENESS, MACRO LEVEL

Strategic Issue

Demography is destiny.All kinds of things aregoverned to a signifi-cant extent by demo-

graphic changes.

Assessing market attractiveness requires that important macro-environmental trends~rmacro trends, for short--be noticed and understood. The macro-environment can be di-vided into six major components: demographic, sociocultural, economic, technological,regulatory, and natural environments. The key question marketing managers and strategistsmust ask in each of these arenas is what trends are out there that are influencing demandin the market of interest, whether favorably or unfavorably.

The Demographic Environment

As the saying goes, demography is destiny. All kinds of things--from sales of music CDsto the state of public finances to society’s costs of health care to the financing of pensions--are governed to a significant extent by demographic changes. While the number of specificdemographic trends that might influence one marketer or another is without limit, there arefive major global demographic trends that are likely to influence the fortunes of many com-panies, for better or worse: the aging of the world’s population, the effect of the AIDSplague on demography, the imbalance between rates of population growth in richer versuspoorer countries, increased levels of immigration, and the decline in married householdsin developed countries.

Aging

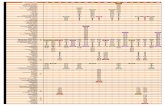

Exhibit 4.2 shows the projected increase in the portion of the population aged over 60 inseveral of the world’s most developed countries. The chart shows that in Italy, for example,about half the population will be over 60 by the year 2040, according to current projec-tions. Providers of health care, vacation homes, life insurance, and other goods and ser-vices have taken note of the graying of the world’s population and are taking steps to de-velop marketing strategies to serve this fast-growing market.

Doing so, however, isn’t always easy. Many people do not wish to be pigeonholed aselderly and some who are may not be very attracted to goods or services that remind themof their age. One marketer dealing with this challenge is Ferrari, whose average customeris nearing 50 and getting older with each passing year. "The profile of our customersmeans we have to pay attention to practicality and functionality without compromising thesportiness," says Giuseppe Bonollo, Ferrari’s strategic marketing director. "The way thedoors open on the Enzo, for example, allows part of the roof and part of the door under-molding to come away as ~vell, making it easier to enter the car.’"

;HIBIT 4.2Aging Populations% of the populationaged over 60

~Olt!72e: Norma Cohen alldClive Cookson, "The Planet lsEver Greyer: Btlt as LongevityRises Paster Than Forecast, theElderly Are Also BecomingHealthier," Financial Times,

January 19, 2004, p. 15.Reprinted by permission.

us

Australia

Canada

UK

France

Germany

Sweden

Japan

Italy

0

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 89

I

1

10 20 30 40 50*Projection

The implications of the aging trend are not as clear-cut as they might appear. There isevidence, for example, that today’s elderly generation is both healthier and fitter than itspredecessors. Thus, fears that health and other facilities will be swamped by hordes of ail-ing pensioners may be misplaced. "New data demolish such concerns," reports RaymondTillis, professor of geriatric medicine at Manchester University in the U.K. "There is a lotof evidence that disability among old people is declining rapidly.’’4

AIDS

The death toll due to HIV/AIDS in Africa, the hardest hit region, was some 8 million from1995 to 2000. Expectations are that 15 million Africans will die of AIDS from 2000 to2005? Across Africa, grandparents are raising an entire generation of children, as the par-ents have died. For more on the AIDS pandemic, see Exhibit 4.3.

Pharmaceutical companies and world health organizations are struggling to developstrategies to deal with the AIDS challenge, one that presents a huge and rapidly growingmarket, but one in which there is little ability to pay for the advanced drug therapies thatoffer hope to AIDS victims.

Imbalanced Population Growth

There are 6.3 billion people in the world today, a number that is growing by some 77 mil-

lion each year, an annual rate of just 1.2 percent. But five countries--India (21 percent),

China (12 percent), Pakistan (5 percent), Bangladesh, and Nigeria (4 percent each) account

for nearly half of that increase. Virtually all the growth in the world’s population over the

EXHIBIT 4.3

Less developed countries in Africa and Asia are facing anunprecedented crisis caused by the rapid permeationand spread of HIV/AIDS. Average life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa has been dramatically reduced to 47 from62 years. Africa remains by far the worst affected regionin the world: 3.5 million new infections occurred inAfrica in 2001, bringing to 28.5 million the total numberof people living with HIV/AIDS in the region. In contrastto the developed world, where up to 30 percent of all in-fected people receive antiretroviral therapy, fewer than30,000 people (0.1 percent) of the 28.5 million infected

The bnpact of the HIV/AIDS Pandemic

Africans were estimated to have received antiretroviraltherapy. Although this represents a huge market oppor-tunity for pharmaceutical companies, they also have toincorporate the vastly lower financing capabilities inthese nations and the almost nonexistent medical andpatient-monitoring infrastructure prevalent there.

Source: The Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic 2002: A Status Report, at

the Johns Hopkins AIDS Service, http://www.hopkins-aids.edu/publications/[eport/sept02_5html#global.

88 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

ASSESSING MARKET AND INDUSTRY ATTRACTIVENESS

As Exhibit 4.1 shows, markets and industries must be assessed at both the macro and microlevels of analysis. But what do these levels really mean? On both the market and industrysides, the macro-level analyses are based on environmental conditions that affect the mar-ket or industry, respectively, as a whole, without regard to a particular company’s strategyor its role in its industry. These external and largely uncontrollable forces or conditionsmust be reckoned with in assessing and shaping any opportunity, and indeed, in develop-ing any coherent marketing strategy.

At the micro level, the analyses look not at the market or the industry overall but at in-dividuals that comprise the market or industry, that is, specific target customers and com-panies themselves, respectively. We develop and apply the relevant analytical frameworksfor the macro-level analyses first; then we address the micro-level analyses.

MACRO TREND ANALYSIS: A FRAMEWORK FOR ASSESSING MARKET

ATTRACTIVENESS, MACRO LEVEL

Strategic Issue

Demography is destiny.All kinds of things aregoverned to a signifi-cant extent by demo-

graphic changes.

Assessing market attractiveness requires that important macro-environmental trends~rmacro trends, for short--be noticed and understood. The macro-environment can be di-vided into six major components: demographic, sociocultural, economic, technological,regulatory, and natural environments. The key question marketing managers and strategistsmust ask in each of these arenas is what trends are out there that are influencing demandin the market of interest, whether favorably or unfavorably.

The Demographic Environment

As the saying goes, demography is destiny. All kinds of things--from sales of music CDsto the state of public finances to society’s costs of health care to the financing of pensions--are governed to a significant extent by demographic changes. While the number of specificdemographic trends that might influence one marketer or another is without limit, there arefive major global demographic trends that are likely to influence the fortunes of many com-panies, for better or worse: the aging of the world’s population, the effect of the AIDSplague on demography, the imbalance between rates of population growth in richer versuspoorer countries, increased levels of immigration, and the decline in married householdsin developed countries.

Aging

Exhibit 4.2 shows the projected increase in the portion of the population aged over 60 inseveral of the world’s most developed countries. The chart shows that in Italy, for example,about half the population will be over 60 by the year 2040, according to current projec-tions. Providers of health care, vacation homes, life insurance, and other goods and ser-vices have taken note of the graying of the world’s population and are taking steps to de-velop marketing strategies to serve this fast-growing market.

Doing so, however, isn’t always easy. Many people do not wish to be pigeonholed aselderly and some who are may not be very attracted to goods or services that remind themof their age. One marketer dealing with this challenge is Ferrari, whose average customeris nearing 50 and getting older with each passing year. "The profile of our customersmeans we have to pay attention to practicality and functionality without compromising thesportiness," says Giuseppe Bonollo, Ferrari’s strategic marketing director. "The way thedoors open on the Enzo, for example, allows part of the roof and part of the door under-molding to come away as ~vell, making it easier to enter the car.’"

;HIBIT 4.2Aging Populations% of the populationaged over 60

~Olt!72e: Norma Cohen alldClive Cookson, "The Planet lsEver Greyer: Btlt as LongevityRises Paster Than Forecast, theElderly Are Also BecomingHealthier," Financial Times,

January 19, 2004, p. 15.Reprinted by permission.

us

Australia

Canada

UK

France

Germany

Sweden

Japan

Italy

0

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 89

I

1

10 20 30 40 50*Projection

The implications of the aging trend are not as clear-cut as they might appear. There isevidence, for example, that today’s elderly generation is both healthier and fitter than itspredecessors. Thus, fears that health and other facilities will be swamped by hordes of ail-ing pensioners may be misplaced. "New data demolish such concerns," reports RaymondTillis, professor of geriatric medicine at Manchester University in the U.K. "There is a lotof evidence that disability among old people is declining rapidly.’’4

AIDS

The death toll due to HIV/AIDS in Africa, the hardest hit region, was some 8 million from1995 to 2000. Expectations are that 15 million Africans will die of AIDS from 2000 to2005? Across Africa, grandparents are raising an entire generation of children, as the par-ents have died. For more on the AIDS pandemic, see Exhibit 4.3.

Pharmaceutical companies and world health organizations are struggling to developstrategies to deal with the AIDS challenge, one that presents a huge and rapidly growingmarket, but one in which there is little ability to pay for the advanced drug therapies thatoffer hope to AIDS victims.

Imbalanced Population Growth

There are 6.3 billion people in the world today, a number that is growing by some 77 mil-

lion each year, an annual rate of just 1.2 percent. But five countries--India (21 percent),

China (12 percent), Pakistan (5 percent), Bangladesh, and Nigeria (4 percent each) account

for nearly half of that increase. Virtually all the growth in the world’s population over the

EXHIBIT 4.3

Less developed countries in Africa and Asia are facing anunprecedented crisis caused by the rapid permeationand spread of HIV/AIDS. Average life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa has been dramatically reduced to 47 from62 years. Africa remains by far the worst affected regionin the world: 3.5 million new infections occurred inAfrica in 2001, bringing to 28.5 million the total numberof people living with HIV/AIDS in the region. In contrastto the developed world, where up to 30 percent of all in-fected people receive antiretroviral therapy, fewer than30,000 people (0.1 percent) of the 28.5 million infected

The bnpact of the HIV/AIDS Pandemic

Africans were estimated to have received antiretroviraltherapy. Although this represents a huge market oppor-tunity for pharmaceutical companies, they also have toincorporate the vastly lower financing capabilities inthese nations and the almost nonexistent medical andpatient-monitoring infrastructure prevalent there.

Source: The Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic 2002: A Status Report, at

the Johns Hopkins AIDS Service, http://www.hopkins-aids.edu/publications/[eport/sept02_5html#global.

90 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.4 Melting Pot Britain: Past, Present and Future

[] 1600s: About 50,000 French Protestants,known as Huguenots, admitted afterreligious persecution in France. TheHuguenots give the word "refugee" to theEnglish language

1840s: An estimated 1 m Irish flee famineand flock to Britain’s new industrial centres

1890s: About 100,000 Jews arrive inBritain from central and eastern Europe

1930s" 56,000 Jews fleeing from Nazipersecution join the earlier group

1955-62:472,000 Commonwealth citizens,primarily from the Caribbean and southernAsia move to Britain. Many were activelyrecruited abroad by big employers includingthe London Underground

1970s: 30,000 Asians forced out of Ugandaby General Idi Amin allowed to settle in UKby Edward Heath

Turnstile Britain: how migration is increasing

The line, and right-hand500 000s -- scale, show the net

number of people400 ~ coming into the UK

2O0

100

0OUTFLOW

2O0

300 m ,left-hand scale, show

400 -- the total number bothentering and leaving

500 i i i ~ i I ~1971 76

~25O

200

150

-1I--1I-1- 0:~ -100

.L~L._I~L_--200

I81 86 91 94 97 2000 01 02

Somve: Chart: Melting Pot Britaiu: Past, Prcsenl, and Future, The Sundqv Times, November 16, 2003, Focus, p. 16. Reprinted by permission.

next half century, some 2.6 billion according to the UN forecast, will be in developing

countries." Of this number, 1 billion will be in the least developed countries that only com-

prise 718 million people today. On the other side of the coin, 33 countries are expected to

have smaller populations in 2050 than today--Japan, Italy, and Russia among them.

For marketers, these changes are important. For makers of capital goods, population

growth in Asia and Africa means a growing need for capital goods to satisfy growing de-

mand for manufactured goods to serve local and export markets. For Western consumer

goods companies seeking to grow, Asia and Africa are where the action will be, though

strategies to serve the much lower income customers in those markets will have to differ

from those developed for richer Western markets. Procter & Gamble, for example, has be-

come a market leader in shampoo in India by packing its products in small sachets that pro-

vide enough gel for a single shampoo, in response to the modest purchasing power of its

Indian customers. No large economy size here!

Increased hnmigration

Not surprisingly, the increasing imbalance between the economic prospects for those liv-

ing in more developed versus less developed countries is leading to increased levels of im-

migration. With the 2004 enlargement of the European Union from 15 to 25 countries,

fears have grown that some countries in the "old EU" would be swamped with immigrants

from the accession countries in Eastern Europe, where per capita GDP is only 46 percent

of the EU 15 average.7

In one sense, this wave of immigration is nothing new, for melting pot countries like the

United States and U.K. have for centuries welcomed immigrants to their shores (see Ex-

hibit 4.4). In the United States, many years of immigration from Mexico and Latin Amer-

ica have made the sun belt a bilingual region, and many now view Miami as the crossroads

of Latin America. The implications for marketers seeking to gain market share among His-

panic Americans are obvious.

! i:rategic IssueSociocultural trends cantake a generation ormore to have significantimpact. Within thisbroadly stable pattern,however, sociocultural

trends can and do exertpowerful effects.

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 91

Declining Marriage Rates

A generation ago, a single, 30-something professional woman out with her single friendsfor a night on the town would have been considered an aberration. No more. Marriage inmuch of the Western world is on the wane. In the United States, married couples, whichcomprised 80 percent of households in the 1950s, now account for just 50.7 percent?Young couples are delaying marriage, cohabitating in greater numbers, forming same-sexpartnerships, and are remarrying less after a wedding leads to divorce. Later in life, theyare living longer, which is increasing the number of widows.

Implications for marketers? For one, consider the implications of marrying in one’s 30s,well into one’s career, rather than in one’s 20s. It’s less likely that the parents of the bridewill handle the wedding arrangements--not to mention the hefty bills that must be paid!-so couples are planning and managing their weddings themselves. In the U.K. a new mag-azine, Stag and Groom, hit the market in 2004 to take the fear out of the wedding processfor the clueless grooms who must now play a more important role. Who buys it? That’sright, brides buy it on the newsstand and give it to their husbands-to-be!

The Sociocultural EnvironmentSociocultural trends are those that have to do with the values, attitudes, and behavior of in-

dividuals in a given society. Cultures tend to evolve slowly, however, so some sociocultu-

ral trends can take a generation or more to have significant impact, as people tend to carry

for a lifetime the values with which they grow up. Within this broadly stable pattern, how-

ever, sociocultural trends can and do exert powerful effects on markets for a great variety

of goods and services. Two trends of particular relevance today are greater interest in eth-

ical behavior by businesses and trends toward fitness and nutrition.

Business Ethics

For years, the world’s leading coffee marketers, including Kraft and Nestld, resisted callsto pay premium prices for coffee grown in a sustainable manner, on farms that pay theirworkers a living wage and respect the enviromnent. In 2003, l<h’aft, running neck and neckwith Nestl~ for the number one spot in market share globally, reached agreement with theRainforest Alliance, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve the working, social, andenvironmental conditions in agriculture in the third world. The agreement calls for Kraftto buy £5 million of Rainforest Alliance-certified coffee from Brazil, Colombia, Mexico,and Central America in 2004, paying a 20 percent premium to the farmers/

Why did Kxaft take this step? "This is not about philantbxopy," says Kraft’s AnnemiekeWijn. "This is about incorporating sustainable coffee into our mainstream brands as a wayto have a more efficient and competitive way of doing business." In short, Kraft made thejump because consumers demanded it.

Fitness and Nutrition

Running. Working out. Fitness clubs. The South Beach and Atkins diets. These days, nat-

ural and organic foods are in (see Exhibit 4.5). Sugar and cholesterol at least the bad

LDL cholesterol--are out.’° The implications of these sociocultural trends are playing out

in grocery store produce departments, where entire sections are now devoted to organic

produce; in the farming connnunities of North America and Europe, where fields formerly

farmed ~vith fertilizers are being transformed into organic ones; and on restaurant menus,

where selections are being revamped to make them appeal to customers who have adopted

new eating habits. The 20-ounce T-bone steak is a thing of the past, at least in some circles.

These trends are driving more than just the food business, however. Attendance at heath

and fitness clubs is booming. Sales of home exercise equipment are up, along with advice

on how to purchase and use it to best advantage.II

90 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.4 Melting Pot Britain: Past, Present and Future

[] 1600s: About 50,000 French Protestants,known as Huguenots, admitted afterreligious persecution in France. TheHuguenots give the word "refugee" to theEnglish language

1840s: An estimated 1 m Irish flee famineand flock to Britain’s new industrial centres

1890s: About 100,000 Jews arrive inBritain from central and eastern Europe

1930s" 56,000 Jews fleeing from Nazipersecution join the earlier group

1955-62:472,000 Commonwealth citizens,primarily from the Caribbean and southernAsia move to Britain. Many were activelyrecruited abroad by big employers includingthe London Underground

1970s: 30,000 Asians forced out of Ugandaby General Idi Amin allowed to settle in UKby Edward Heath

Turnstile Britain: how migration is increasing

The line, and right-hand500 000s -- scale, show the net

number of people400 ~ coming into the UK

2O0

100

0OUTFLOW

2O0

300 m ,left-hand scale, show

400 -- the total number bothentering and leaving

500 i i i ~ i I ~1971 76

~25O

200

150

-1I--1I-1- 0:~ -100

.L~L._I~L_--200

I81 86 91 94 97 2000 01 02

Somve: Chart: Melting Pot Britaiu: Past, Prcsenl, and Future, The Sundqv Times, November 16, 2003, Focus, p. 16. Reprinted by permission.

next half century, some 2.6 billion according to the UN forecast, will be in developing

countries." Of this number, 1 billion will be in the least developed countries that only com-

prise 718 million people today. On the other side of the coin, 33 countries are expected to

have smaller populations in 2050 than today--Japan, Italy, and Russia among them.

For marketers, these changes are important. For makers of capital goods, population

growth in Asia and Africa means a growing need for capital goods to satisfy growing de-

mand for manufactured goods to serve local and export markets. For Western consumer

goods companies seeking to grow, Asia and Africa are where the action will be, though

strategies to serve the much lower income customers in those markets will have to differ

from those developed for richer Western markets. Procter & Gamble, for example, has be-

come a market leader in shampoo in India by packing its products in small sachets that pro-

vide enough gel for a single shampoo, in response to the modest purchasing power of its

Indian customers. No large economy size here!

Increased hnmigration

Not surprisingly, the increasing imbalance between the economic prospects for those liv-

ing in more developed versus less developed countries is leading to increased levels of im-

migration. With the 2004 enlargement of the European Union from 15 to 25 countries,

fears have grown that some countries in the "old EU" would be swamped with immigrants

from the accession countries in Eastern Europe, where per capita GDP is only 46 percent

of the EU 15 average.7

In one sense, this wave of immigration is nothing new, for melting pot countries like the

United States and U.K. have for centuries welcomed immigrants to their shores (see Ex-

hibit 4.4). In the United States, many years of immigration from Mexico and Latin Amer-

ica have made the sun belt a bilingual region, and many now view Miami as the crossroads

of Latin America. The implications for marketers seeking to gain market share among His-

panic Americans are obvious.

! i:rategic IssueSociocultural trends cantake a generation ormore to have significantimpact. Within thisbroadly stable pattern,however, sociocultural

trends can and do exertpowerful effects.

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 91

Declining Marriage Rates

A generation ago, a single, 30-something professional woman out with her single friendsfor a night on the town would have been considered an aberration. No more. Marriage inmuch of the Western world is on the wane. In the United States, married couples, whichcomprised 80 percent of households in the 1950s, now account for just 50.7 percent?Young couples are delaying marriage, cohabitating in greater numbers, forming same-sexpartnerships, and are remarrying less after a wedding leads to divorce. Later in life, theyare living longer, which is increasing the number of widows.

Implications for marketers? For one, consider the implications of marrying in one’s 30s,well into one’s career, rather than in one’s 20s. It’s less likely that the parents of the bridewill handle the wedding arrangements--not to mention the hefty bills that must be paid!-so couples are planning and managing their weddings themselves. In the U.K. a new mag-azine, Stag and Groom, hit the market in 2004 to take the fear out of the wedding processfor the clueless grooms who must now play a more important role. Who buys it? That’sright, brides buy it on the newsstand and give it to their husbands-to-be!

The Sociocultural EnvironmentSociocultural trends are those that have to do with the values, attitudes, and behavior of in-

dividuals in a given society. Cultures tend to evolve slowly, however, so some sociocultu-

ral trends can take a generation or more to have significant impact, as people tend to carry

for a lifetime the values with which they grow up. Within this broadly stable pattern, how-

ever, sociocultural trends can and do exert powerful effects on markets for a great variety

of goods and services. Two trends of particular relevance today are greater interest in eth-

ical behavior by businesses and trends toward fitness and nutrition.

Business Ethics

For years, the world’s leading coffee marketers, including Kraft and Nestld, resisted callsto pay premium prices for coffee grown in a sustainable manner, on farms that pay theirworkers a living wage and respect the enviromnent. In 2003, l<h’aft, running neck and neckwith Nestl~ for the number one spot in market share globally, reached agreement with theRainforest Alliance, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve the working, social, andenvironmental conditions in agriculture in the third world. The agreement calls for Kraftto buy £5 million of Rainforest Alliance-certified coffee from Brazil, Colombia, Mexico,and Central America in 2004, paying a 20 percent premium to the farmers/

Why did Kxaft take this step? "This is not about philantbxopy," says Kraft’s AnnemiekeWijn. "This is about incorporating sustainable coffee into our mainstream brands as a wayto have a more efficient and competitive way of doing business." In short, Kraft made thejump because consumers demanded it.

Fitness and Nutrition

Running. Working out. Fitness clubs. The South Beach and Atkins diets. These days, nat-

ural and organic foods are in (see Exhibit 4.5). Sugar and cholesterol at least the bad

LDL cholesterol--are out.’° The implications of these sociocultural trends are playing out

in grocery store produce departments, where entire sections are now devoted to organic

produce; in the farming connnunities of North America and Europe, where fields formerly

farmed ~vith fertilizers are being transformed into organic ones; and on restaurant menus,

where selections are being revamped to make them appeal to customers who have adopted

new eating habits. The 20-ounce T-bone steak is a thing of the past, at least in some circles.

These trends are driving more than just the food business, however. Attendance at heath

and fitness clubs is booming. Sales of home exercise equipment are up, along with advice

on how to purchase and use it to best advantage.II

92 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.5

Tracey Daugherty, a 33-year-old mother from Pittsburgh,grew up eating Kraft macaroni and cheese. Today,though, Kraft’s marketing strategists have queasy stom-achs because Daugherty and others won’t feed it to theirown children. "Kraft’s products definitely have a child-hood nostalgia," she says, "so it’s hard to completelygive up on them, but they’re not on my shopping list."When she’s pressed for time, Daugherty is more likely topull an organic frozen dinner out of the freezer than boilup a batch of Kraft Mac and Cheese. On most nights,what’s on her family’s dinner table includes fresh pro-duce and chicken or fish from Whole Foods, the fast-growing American grocery chain that built its reputationon natural and organic foods.

To cope with American’s growing preference for freshand natural foods rather than prepackaged andprocessed ones, the big food companies are having torethink their businesses, find new suppliers, and aug-ment their product lines with new, healthier versions oftheir longstanding best-sellers. Kraft, which owns brands

Health Trends Give Kraft a Stomach Ache

such as Oscar Mayer (hot dogs, with their high animalfat content, are not known as a health food), JelI-O gel-atin (mostly sugar, a no-no on today’s low carbohydratediets), and Nabisco (whose cookies and crackers areladen with both carbs and trans-fats, the latest additionto health experts’ "avoid" lists), has struggled to meet itsdouble-digit growth targets, as consumers increasinglyshift their food dollars to healthier fare.

As Wharton Marketing Professor Patricia Williamspoints out, the question for the food giants is, "To whatextent is the Atkins diet and the whole Iow-carb thing afad and to what extent is it a genuine shift in consump-tion patterns that will remain with us for a significant pe-riod of time." It’s a question that Kraft and others in thefood industry cannot afford to take lightly.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal Europe (staff produced copyonly) by Sarah Ellison. Copyright 2004 by Dow Jones & Co. Inc.Reproduced with permission of Dow Jones & Co. Inc. in the for-mat textbook via Copyright Clearance Center.

Strategic Issue

Take robnst economichealth, for exalnple, it’sgood for everyone,right?

The Economic EnvironmentAmong the most far-reaching of the six macro trend components is the economic envi-

ronment. When people’s incomes rise or fall, when interest rates rise or fall, when the fis-

cal policy of governments results in increased or decreased government spending, entire

sectors of economies are influenced deeply, and sometimes suddenly. As we write, the

Western world is struggling with a variety of economic challenges: a jobless recovery in

the United States, where robust growth in gross domestic prodnet (GDP) has not yet been

accompanied by much growth in employment; and persistent stagnation in Western Eu-

rope, where economic growth is stalled at very low levels in some countries.

The implications of trends like these can be dramatic for marketers, to be sure, but they

can be far subtler than one might imagine. Take robust economic health, for example. It’s

good for everyone, right? Not if you’re the operator of a chain of check-cashing outlets or

pawn shops, which thrive when times are tough and people need to turn unwanted assets

into cash quickly. Or consider the newest wave in franchising, brick-and mortar stores that

help people sell their unwanted goods online on eBay. California-based AuctionDrop

raised $6 million in venture capital to roll out a franchised chain of such stores.I-’ If the

economy gets healthier, will people need such stores to help them dispose of unwanted

goods? Time will tell.

Economic trends often work, to pronounced effect, in concert with other macro trends.

For example, the move of the baby-boomer generation into middle age in the 1990s, a de-

mographic trend, combined with a strong global economy and low interest rates, both eco-

nomic trends, led to booming demand for condominiums and vacation homes in resort

areas like the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and the south of Spain and Portugal.

The Regulatory EnvironmentIn every country and across some countries--those that are members of the EU, for ex-

ample-there is a regulatory environment within which local and multinational fu’ms op-

erate. As with the other macro trend components, political and legal trends, especially

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 93

those that result in regulation or deregulation, can have powerful impact on market

attractiveness.

In September 2003, voters in Sweden resoundingly rejected the euro, preferring to

maintain their own Swedish currency and thereby retain independent domestic control of

their country’s fiscal policy and remain freer than those in the euro-zone of what some see

as stifling overregulation froln Brussels.~ Indications are that Derunark and Britain may

also stay out of the conmmn currency. For marketers involved in import or export busi-

nesses in Europe, the implications may prove significant, as uncertainties inherent in pre-

dicting foreign exchange rates make trade and investment decisions more tenuous.

The power of deregulation to influence market attractiveness is now well-known. Gov-

ermnent, business, and the general public throughout much of the world have become in-

creasingly aware that overregulation protects inefficiencies, restricts entry by new com-

petitors, and creates inflationary pressures. In the United States, airlines, trucking,

railroads, telecommunications, and banking have been deregulated. Markets also are beingliberated in Western and Eastern Europe, Asia, and many of the developing countries.

Trade barriers are crumbling due to political unrest and technological innovation.

Deregulation has typically changed the structure of the affected industries as well as

lowered prices creating rapid growth in some markets as a result. For example, the period

following deregulation of the U.S. airline industry (1978 1985), gave rise to a new airline

categor~the budget airline. The rise of Southwest and other budget airlines led to lower

fares across all routes, and forced the major carriers to streamline operations and phase out

underperforming routes. ’~ A similar story has followed in the European market, where dis-

count airlines Ryanair, Easy Jet, and others have made vacations something to fly to rather

than drive to.

As regulatory practices wax and wane, the attractiveness of markets often follows suit. For

example, the deregulation of telecormnunications in Europe, following earlier deregulation

in the United States, is opening markets to firms seeking to offer new services and take mar-

ket share fi’om the established monopolies. The rise of Internet retailing and Internet tele-

phony has policy makers arguing over the degree to which these Internet activities should be

subject to state and federal tax in the United States. The outcome of these arguments may

have considerable effect on consumers’ interest in buying and calling on the Web.

The Technological Environment

In the past three decades, an amazing number of new technologies have created new

markets for such products as video recorders, compact disks, ever-more-powerful and ever-

smaller computers, fax machh~es, new lightweight materials, and highly effective genetically

engineered drugs. Technological progress over the next 10 years is predicted to be several

times that experienced during the past 10 years, and much of it will be spurred by the need

to find solutions to our environmental problems. Major technological innovations can be ex-

pected in a variety of fields, especially in biology and electronics/telecommunications. ’-~

Technology can also change ho~v businesses operate (banks, airlines, retail stores, and

marketing research firms), how goods and services as well as ideas are exchanged, and how

individuals learn and earn as well as interact with one another. Consumers today enjoy

check-free banking, the death of the invoice, and ticketless air travel.

These innovations are the result not only of changes in computing systems but also

of reduced costs in comlnunicating (voice or data). For example, the cost of processing an

additional telephone call is so small it might as well be free. And distance is no longer a

factor it costs about the same to make a trans-Atlantic call as one to your next-door

neighbor.’6

At the dawn of the new millennium, developments in telecolnmunications and com-

puting have led to the rapid convergence of the telecommunications, computing, and

92 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.5

Tracey Daugherty, a 33-year-old mother from Pittsburgh,grew up eating Kraft macaroni and cheese. Today,though, Kraft’s marketing strategists have queasy stom-achs because Daugherty and others won’t feed it to theirown children. "Kraft’s products definitely have a child-hood nostalgia," she says, "so it’s hard to completelygive up on them, but they’re not on my shopping list."When she’s pressed for time, Daugherty is more likely topull an organic frozen dinner out of the freezer than boilup a batch of Kraft Mac and Cheese. On most nights,what’s on her family’s dinner table includes fresh pro-duce and chicken or fish from Whole Foods, the fast-growing American grocery chain that built its reputationon natural and organic foods.

To cope with American’s growing preference for freshand natural foods rather than prepackaged andprocessed ones, the big food companies are having torethink their businesses, find new suppliers, and aug-ment their product lines with new, healthier versions oftheir longstanding best-sellers. Kraft, which owns brands

Health Trends Give Kraft a Stomach Ache

such as Oscar Mayer (hot dogs, with their high animalfat content, are not known as a health food), JelI-O gel-atin (mostly sugar, a no-no on today’s low carbohydratediets), and Nabisco (whose cookies and crackers areladen with both carbs and trans-fats, the latest additionto health experts’ "avoid" lists), has struggled to meet itsdouble-digit growth targets, as consumers increasinglyshift their food dollars to healthier fare.

As Wharton Marketing Professor Patricia Williamspoints out, the question for the food giants is, "To whatextent is the Atkins diet and the whole Iow-carb thing afad and to what extent is it a genuine shift in consump-tion patterns that will remain with us for a significant pe-riod of time." It’s a question that Kraft and others in thefood industry cannot afford to take lightly.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal Europe (staff produced copyonly) by Sarah Ellison. Copyright 2004 by Dow Jones & Co. Inc.Reproduced with permission of Dow Jones & Co. Inc. in the for-mat textbook via Copyright Clearance Center.

Strategic Issue

Take robnst economichealth, for exalnple, it’sgood for everyone,right?

The Economic EnvironmentAmong the most far-reaching of the six macro trend components is the economic envi-

ronment. When people’s incomes rise or fall, when interest rates rise or fall, when the fis-

cal policy of governments results in increased or decreased government spending, entire

sectors of economies are influenced deeply, and sometimes suddenly. As we write, the

Western world is struggling with a variety of economic challenges: a jobless recovery in

the United States, where robust growth in gross domestic prodnet (GDP) has not yet been

accompanied by much growth in employment; and persistent stagnation in Western Eu-

rope, where economic growth is stalled at very low levels in some countries.

The implications of trends like these can be dramatic for marketers, to be sure, but they

can be far subtler than one might imagine. Take robust economic health, for example. It’s

good for everyone, right? Not if you’re the operator of a chain of check-cashing outlets or

pawn shops, which thrive when times are tough and people need to turn unwanted assets

into cash quickly. Or consider the newest wave in franchising, brick-and mortar stores that

help people sell their unwanted goods online on eBay. California-based AuctionDrop

raised $6 million in venture capital to roll out a franchised chain of such stores.I-’ If the

economy gets healthier, will people need such stores to help them dispose of unwanted

goods? Time will tell.

Economic trends often work, to pronounced effect, in concert with other macro trends.

For example, the move of the baby-boomer generation into middle age in the 1990s, a de-

mographic trend, combined with a strong global economy and low interest rates, both eco-

nomic trends, led to booming demand for condominiums and vacation homes in resort

areas like the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and the south of Spain and Portugal.

The Regulatory EnvironmentIn every country and across some countries--those that are members of the EU, for ex-

ample-there is a regulatory environment within which local and multinational fu’ms op-

erate. As with the other macro trend components, political and legal trends, especially

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 93

those that result in regulation or deregulation, can have powerful impact on market

attractiveness.

In September 2003, voters in Sweden resoundingly rejected the euro, preferring to

maintain their own Swedish currency and thereby retain independent domestic control of

their country’s fiscal policy and remain freer than those in the euro-zone of what some see

as stifling overregulation froln Brussels.~ Indications are that Derunark and Britain may

also stay out of the conmmn currency. For marketers involved in import or export busi-

nesses in Europe, the implications may prove significant, as uncertainties inherent in pre-

dicting foreign exchange rates make trade and investment decisions more tenuous.

The power of deregulation to influence market attractiveness is now well-known. Gov-

ermnent, business, and the general public throughout much of the world have become in-

creasingly aware that overregulation protects inefficiencies, restricts entry by new com-

petitors, and creates inflationary pressures. In the United States, airlines, trucking,

railroads, telecommunications, and banking have been deregulated. Markets also are beingliberated in Western and Eastern Europe, Asia, and many of the developing countries.

Trade barriers are crumbling due to political unrest and technological innovation.

Deregulation has typically changed the structure of the affected industries as well as

lowered prices creating rapid growth in some markets as a result. For example, the period

following deregulation of the U.S. airline industry (1978 1985), gave rise to a new airline

categor~the budget airline. The rise of Southwest and other budget airlines led to lower

fares across all routes, and forced the major carriers to streamline operations and phase out

underperforming routes. ’~ A similar story has followed in the European market, where dis-

count airlines Ryanair, Easy Jet, and others have made vacations something to fly to rather

than drive to.

As regulatory practices wax and wane, the attractiveness of markets often follows suit. For

example, the deregulation of telecormnunications in Europe, following earlier deregulation

in the United States, is opening markets to firms seeking to offer new services and take mar-

ket share fi’om the established monopolies. The rise of Internet retailing and Internet tele-

phony has policy makers arguing over the degree to which these Internet activities should be

subject to state and federal tax in the United States. The outcome of these arguments may

have considerable effect on consumers’ interest in buying and calling on the Web.

The Technological Environment

In the past three decades, an amazing number of new technologies have created new

markets for such products as video recorders, compact disks, ever-more-powerful and ever-

smaller computers, fax machh~es, new lightweight materials, and highly effective genetically

engineered drugs. Technological progress over the next 10 years is predicted to be several

times that experienced during the past 10 years, and much of it will be spurred by the need

to find solutions to our environmental problems. Major technological innovations can be ex-

pected in a variety of fields, especially in biology and electronics/telecommunications. ’-~

Technology can also change ho~v businesses operate (banks, airlines, retail stores, and

marketing research firms), how goods and services as well as ideas are exchanged, and how

individuals learn and earn as well as interact with one another. Consumers today enjoy

check-free banking, the death of the invoice, and ticketless air travel.

These innovations are the result not only of changes in computing systems but also

of reduced costs in comlnunicating (voice or data). For example, the cost of processing an

additional telephone call is so small it might as well be free. And distance is no longer a

factor it costs about the same to make a trans-Atlantic call as one to your next-door

neighbor.’6

At the dawn of the new millennium, developments in telecolnmunications and com-

puting have led to the rapid convergence of the telecommunications, computing, and

94 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.6 The Search Engine Revohttion

As the Internet and the World Wide Web grew, it be-came increasingly difficult to find what you were lookingfor. Early search engines started off as directories of Webpages or links, for example Yahoo. Most early search en-gines evolved into net portals--places that people begintheir search for information. Today search is a sophisti-cated science, measured more by the relevance of theanswers to a query rather than the number of Webpages returned.

In the aftermath of September 11, news sites such as

CNN were overwhelmed by people looking for the latestinformation. The search engine Google stepped in, bysaving copies of the news pages and serving them up

from its cache. Search services are now a vital intermedi-ary, and among the most frequented sites on the Webwith millions of hits or visits every day. Because of thismany search engines have morphed into advertising en-gines, driven by the need to become profitable. Compa-nies can purchase "key words" with search engines, andwhen users search on these key words, the advertiser’sWeb page is displayed first in the results.

Sources: Ben Elgin, Jim Kerstetter, with Linda Himelstein, "WhyThey Are Agog over Google," BusinessWeek September 24, 2001.

Reprinted by permission,

Strategic IssueSavvy marketers andentrepreneurs who fol-low technological trendsare able to foresee newand previously unheardof applications such as

these, sometimes earn-ing entrepreneurialfortunes in the process.

entertainment industries. Music-hungry consumers have been downloading music fromlegal and illegal sites, and have forced the music industry to change the way they distrib-ute music. In June 2002, three of the five major music labels--Universal, Sony, and WarnerMusic announced that they would make thousands of songs available for download overthe Internet at the discount price of 99 cents eachJ7 Cell phone users in Europe and Asiacheck sports scores, breaking news, stock quotes, and more using text messaging or SMS.’’~

Savvy marketers and entrepreneurs who follow technological trends are able to foreseenew and previously unheard of applications such as these and thereby place themselvesand their firms at the forefront of the innovation curve, sometimes earning entrepreneurialfortunes in the process.

In addition to creating attractive new markets, teclmological developments are having aprofound impact on all aspects of marketing practice, including marketing communication(ads on the Web or via e-mail), distribution (books and other consumer and industrialgoods bought and sold via the Web), packaging (use of new materials), and marketing re-search (monitoring supermarket purchases with scanners or Internet activity with digital"cookies"). The search engine revolution (see Exhibit 4.6) is one example of these devel-opments. We explore the most important of these changes in the ensuing chapters in thisbook.

The Natural EnvironmentThe natural environment refers to changes in the earth’s resources and climate, some ofwhich have significant and far-reaching effects. The world’s supply of oil is finite, for ex-ample, leading automakers to develop new hot-selling hybrid gas-electric vehicles such asthe Toyota Prius, which can go more than 50 miles on a gallon of gas.

One of the more frightening enviromnental scenarios concerns the buildup of carbondioxide in the atmosphere that has resulted from heavy use of fossil fuels. This carbondioxide "blanket" traps the sun’s radiation, which leads to an increase in the earth’s aver-age temperature. One computer model of the climate predicts a cooling of Europe; Africa,East Asia, and South America warming a lot; and less rain in East Asia, Southern Africa,most of South America, Mexico, and parts of the United States. While the evidence is in-creasing that greenhouse gases are changing the climate, there is considerable disagree-ment over the details of the warming effects and what to do about them.

In general, discussion of the problems in the natural environment has stressed thethreats and penalties facing business throughout the world. But business can do a number

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 9~

of things to turn problems into opportunities. One is to invest in research to find ways tosave energy in heating and lighting. Another is to find new energy sources such as low-costwind farms and hydroelectric projects.

Businesses also have seen opportunities in developing hundreds of green produels(those that are environmentally friendly) such as phosphate-free detergents, recycled motoroil, tuna caught without netting dolphins, organic fertilizers, high-efficiency light bulbs,recycled paper, and men’s and women’s casual clothes made from 100 percent organic cot-ton and colored with nontoxic dyes.’~

On the other hand, if global warming continues, it may play havoc with markets for win-ter vacationers, snowmobiles, and other products and services whose demand depends onthe reliable coming of Old Man Winter. Other natural trends, such as the depletion of nat-ural resources and fresh groundwater, may significantly impact firms in many industriesserving a vast array of markets. Tracking such trends and understanding their effects is animportant task.

~’,fOUR MARKET IS ATTRACTIVE: WHAT ABOUT YOUR INDUSTRY?

As we saw at the outset of this chapter, consumers and business people have becomehooked on cell phones, and the market for mobile co~mnunication has grown rapidly. Bymost measures, this is a large, growing, and attractive market. But are cell phone manu-facturing and cellular services attractive industries? An industry’s attractiveness at a pointin time can best be judged by analyzing the five major competitive forces, which we ad-dress in this section.

?trategic IssueFive competitive forcescollectively determinean industry’s long-termattractiveness

Porter’s Five Competitive Forces~°

Five competitive forces collectively determine an industry’s long-term attractiveness--rivalry among present competitors, threat of new entrants into the industry, the bargainingpower of suppliers, the bargaining power of buyers, and the tlueat of substitute products(see Exhibit 4.7). This mix of forces explains why some industries are consistently moreprofitable than others and provides further insights into which resources are required andwhich strategies should be adopted to be successful. A useful way to conduct a five forcesanalysis of an industry’s attractiveness is to construct a checklist based on Porter’s seminalwork.=’

The strength of the individual forces varies from industry to industry and, over time,within the same industry. In the fast-food industry, the key forces are rivalry anaong

I~XHIBIT 4.7 The Major Forces That Determine Industry Attractiveness

Bargaining powerof suppliers

Threat of new entrants

Rivalry amongexisting competitors

tThreat of substitute products

Bargaining powerof buyers

94 Section Two Opportunity Analysis

EXHIBIT 4.6 The Search Engine Revohttion

As the Internet and the World Wide Web grew, it be-came increasingly difficult to find what you were lookingfor. Early search engines started off as directories of Webpages or links, for example Yahoo. Most early search en-gines evolved into net portals--places that people begintheir search for information. Today search is a sophisti-cated science, measured more by the relevance of theanswers to a query rather than the number of Webpages returned.

In the aftermath of September 11, news sites such as

CNN were overwhelmed by people looking for the latestinformation. The search engine Google stepped in, bysaving copies of the news pages and serving them up

from its cache. Search services are now a vital intermedi-ary, and among the most frequented sites on the Webwith millions of hits or visits every day. Because of thismany search engines have morphed into advertising en-gines, driven by the need to become profitable. Compa-nies can purchase "key words" with search engines, andwhen users search on these key words, the advertiser’sWeb page is displayed first in the results.

Sources: Ben Elgin, Jim Kerstetter, with Linda Himelstein, "WhyThey Are Agog over Google," BusinessWeek September 24, 2001.

Reprinted by permission,

Strategic IssueSavvy marketers andentrepreneurs who fol-low technological trendsare able to foresee newand previously unheardof applications such as

these, sometimes earn-ing entrepreneurialfortunes in the process.

entertainment industries. Music-hungry consumers have been downloading music fromlegal and illegal sites, and have forced the music industry to change the way they distrib-ute music. In June 2002, three of the five major music labels--Universal, Sony, and WarnerMusic announced that they would make thousands of songs available for download overthe Internet at the discount price of 99 cents eachJ7 Cell phone users in Europe and Asiacheck sports scores, breaking news, stock quotes, and more using text messaging or SMS.’’~

Savvy marketers and entrepreneurs who follow technological trends are able to foreseenew and previously unheard of applications such as these and thereby place themselvesand their firms at the forefront of the innovation curve, sometimes earning entrepreneurialfortunes in the process.

In addition to creating attractive new markets, teclmological developments are having aprofound impact on all aspects of marketing practice, including marketing communication(ads on the Web or via e-mail), distribution (books and other consumer and industrialgoods bought and sold via the Web), packaging (use of new materials), and marketing re-search (monitoring supermarket purchases with scanners or Internet activity with digital"cookies"). The search engine revolution (see Exhibit 4.6) is one example of these devel-opments. We explore the most important of these changes in the ensuing chapters in thisbook.

The Natural EnvironmentThe natural environment refers to changes in the earth’s resources and climate, some ofwhich have significant and far-reaching effects. The world’s supply of oil is finite, for ex-ample, leading automakers to develop new hot-selling hybrid gas-electric vehicles such asthe Toyota Prius, which can go more than 50 miles on a gallon of gas.

One of the more frightening enviromnental scenarios concerns the buildup of carbondioxide in the atmosphere that has resulted from heavy use of fossil fuels. This carbondioxide "blanket" traps the sun’s radiation, which leads to an increase in the earth’s aver-age temperature. One computer model of the climate predicts a cooling of Europe; Africa,East Asia, and South America warming a lot; and less rain in East Asia, Southern Africa,most of South America, Mexico, and parts of the United States. While the evidence is in-creasing that greenhouse gases are changing the climate, there is considerable disagree-ment over the details of the warming effects and what to do about them.

In general, discussion of the problems in the natural environment has stressed thethreats and penalties facing business throughout the world. But business can do a number

Chapter Four Understanding Market Opportunities 9~