ABC Pitch Vouchers Instrument... · 2020. 8. 31. · abc abc abc abc

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences*

Transcript of Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences*

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences*

ADAM S. MAIGA, Florida International University

FRED A. JACOBS, Auburn University, Montgomery and Luleå University of Technology

Abstract

This study uses structural equation modeling to investigate the association between extent of ABC use and quality, cost, and cycle-time improvements; the relations among quality, cost, and cycle-time improvements; and the association of quality, cost, and cycle-time improvements with profitability at the manufacturing plant level. Overall, the results of the structural analyses support the theoretical model, indicating that (a) extent of ABC use has a significant positive association on cost improvement, quality improvement, and cycle-time improvement; (b) quality improvement is significantly associated with both cost improvement and profitability; (c) cost improvement is significantly associated with profitability; (d) quality improvement is significantly associated with cycle-time improvement; and (e) cycle-time improvement is significantly associated with both cost improvement and profitability. However, the direct association between extent of ABC use and profitability is not significant. Rather, the association is through cost improvement, quality improvement, and cycle-time improvement acting as intervening variables.

Keywords Activity-based costing; Operational performance; Profitability

JEL Descriptors C12, C31, L25, L60, M41

The full text of this papeer begins on p. xxx of this issue.

1. Introduction

Activity-based costing (ABC) systems have been suggested as a managementinnovation that can lead to increased competitiveness and enhanced profitability byfirms (Cooper and Kaplan 1992). Because the costs associated with replacing a tra-ditional costing system with ABC, including time commitments by employees andmanagement as well as direct investments in technology and process interruptions,are not insignificant, researchers and business managers are naturally interested inwhether this innovation produces the positive financial results suggested (Cooperand Kaplan 1992). Knowledge of the linkage between ABC and firm performance,as well as the organizational circumstances under which ABC can provide perfor-mance enhancements to companies, are essential inputs to the investment andoperational decisions that companies must make before approving this important

Contemporary Accounting Research Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008) pp. 1–39 © CAAA

doi:10.1506/car.25.2.9

* Accepted by Steven Salterio. The authors would like to thank Steve Salterio (associate editor),two anonymous reviewers, Professors Edward E. Rigdon, Lynn Hannan, Ernie Larkins, NicholasMarudas, and participants in workshops where this paper has been presented. However, weremain responsible for all errors and misstatements.

2 Contemporary Accounting Research

resource allocation decision. Many companies have adopted ABC, and researchershave examined important issues related to the financial impact of this organiza-tional innovation.

Research on the link between ABC and its impact on profitability is stillevolving and many questions remain. Advocates argue that ABC provides a meansof enhancing profitability (Plowman 2001; Cooper and Kaplan 1991; Carolfi 1996)and that it provides companies with a powerful tool for improving financial perfor-mance (Dodd, Lavelle, and Margolis 2002). Findings by Rafig and Garg 2002 suggestthat there is a strong relationship between ABC implementation and profitability;however, many other studies find no relationship between ABC use and superiorfirm performance (Bromwich and Bhimani 1989; Gordon and Silvester 1999;Innes and Mitchell 1995; Ittner, Lanen, and Larcker 2002). Therefore, given theimportant investments in ABC and the related need to increase global competitive-ness in the U.S. economy, more research is needed to assist businesses in under-standing the mechanisms, if any, that contribute to profit enhancements from ABCimplementation, so that economically optimal investments may be made in theeconomy by individual businesses.

Many reasons have been posited for the inconclusive research results on thelinkage between ABC and firm performance. For example, Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (1998) suggest the potential for intervening effects of organizational variablesand call for further research that considers the role of additional relevant firm-specific variables. Similarly, Kennedy and Affleck-Graves (2001) suggest thatABC may not, per se, add value, but may merely be correlated with other variablesthat are true value drivers.1 Therefore, the current research question, related to theabove conjecture, is to investigate whether the effect of the extent of ABC use hasa significant direct impact on plant profitability and/or whether plant operationalperformance measures (i.e., quality, cost, and cycle time) act as intervening vari-ables in the relationship between extent of ABC use and profitability.

From a related theoretical and strategic perspective, additional debate amongscholars of business strategy and marketing is occurring about whether organiza-tions can achieve improvements in both cost and quality simultaneously (Porter1980, 1985) and whether quality can have both revenue-enhancing and cost-reducingeffects (Rust, Zahorik, and Keiningham 1995). For example, Porter (1980, 1985)has taken the position that organizations seldom are able to achieve cost and qualityimprovements simultaneously, while other scholars have argued that organizationsmay pursue both strategies simultaneously (Hall 1983; Murray 1988; Hill 1988;Cronshaw, Davis, and Kay 1994; White 1986). From the marketing literature, Rustet al. (1995) comment on the “duality” debate defined as whether quality improve-ments can both have a positive revenue impact and act to reduce costs. The currentresearch contributes to both streams of literature.

This study is, therefore, timely and important for several reasons. First, empir-ical findings on the direct improvement of ABC on business profitability have beenmixed (e.g., Innes, Mitchell, and Sinclair 2000; Foster and Swenson 1997; Malmi1997; McGowan and Klammer 1997; Anderson 1995; Shields 1995; [AU: Shieldsis 1997 in References; please correct here or there] Morrow and Connolly 1994;

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 3

Cooper and Zmud 1990). Second, the debate on organizations’ ability to pursueboth quality and cost improvements provides an important conceptual foundationfor investigating the extent to which extent of ABC use is associated withimproved quality and cost. Third, the study is important for academics interested inthe association between ABC and profitability to examine intervening variablesthat affect this relationship. Fourth, this study can begin an exploratory contribu-tion to the dialogue regarding whether quality can have a positive, direct effect onprofitability and on reduction of costs. Finally, an important contribution of thisstudy is that managers, too, require a more complete understanding of the condi-tions under which extent of ABC use should be expected to pay off. To our knowl-edge, no prior study has empirically tested the ABC–profitability link within thecontext of plant operational performance as measured by quality, cost, and cycletime.

To address the research issue, this study applies a more sophisticated approachto theory testing and development than that used in prior research, which enablessimultaneous estimation of the relationships among the variables in this study.More specifically, collecting survey data from a cross-section of U.S. manufactur-ing plants, the present study uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess (a)the relations between extent of ABC use and quality improvement, cycle-timeimprovement, and cost improvement and (b) the relations among quality improve-ment, cycle-time improvement, and cost improvement and their association withprofitability.2 Further, this study investigates whether extent of ABC use producesa direct improvement in plant profitability or whether this relationship is estab-lished through plant operational performance (i.e., quality, cost, and cycle-timeimprovement), as conjectured by Kennedy and Affleck-Graves 2001.

Overall, the results of this study indicate support for the hypotheses devel-oped. The extent of ABC use is significantly and positively associated with quality,cost, and cycle-time improvements and quality improvement has a significant pos-itive impact on cost improvement, cycle-time improvement, and profitability.Cycle time is significantly and positively associated with cost improvement andboth are associated with enhanced profitability. Further analysis shows that thedirect relationship between extent of ABC use and manufacturing plant profitabilityis not significant; rather, plant operational performance measures act as interveningvariables in the relationship between extent of ABC use and profitability. Therefore,this research makes an important contribution to the literature on the relationshipbetween ABC and profitability, to the debate about whether there is a strategictrade-off between investments in quality and cost improvement (Porter 1980,1985), and to the discourse on whether quality improvements can have positiveimpact on profits through both revenue enhancements and cost reductions (Rustet al. 1995).

This paper is organized as follows. The next section provides the theoreticaljustification of the relationships examined in the study and the hypotheses. Section 3presents a discussion of the research methods that lead to the empirical results insection 4. Section 5 concludes with a summary of findings, explanation of limita-tions, and suggestions for future research.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

4 Contemporary Accounting Research

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

Extent of ABC use and quality improvement

ABC can serve as a useful information system to support effective decision-makingprocesses related to quality initiatives (Gupta and Galloway 2003). The informa-tion provided by ABC can help identify the drivers of quality problems (Armitageand Russell 1993; Carolfi 1996) by highlighting the quality-related non-value-added activities, which can therefore facilitate quality improvement (Cooper,Kaplan, Maisel, Morrissey, and Oehm 1992; Ittner 1999; Ittner et al. 2002). Jor-genson and Enkerlin (1992) describe how ABC information helped Hewlett-Packardproduct teams simulate and improve quality early in the product-design phase. Ittneret al. (2002) found that ABC use is positively related to higher quality levels.

The preceding argument is captured in the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 1. Extent of ABC use has a significant positive improvement inquality.

Extent of ABC use and cost improvement

Prior studies suggest that the information provided by ABC allows managers toreduce costs by designing products and processes that consume fewer activityresources, increasing the efficiency of existing activities, and eliminating activitiesthat do not add value to customers (Ittner et al. 2002; Gunasekaran and Sarhadi1998). Furthermore, Cooper and Kaplan (1998) argue that when an entity imple-ments ABC, its entire operation is scrutinized in great detail, its performance isanalyzed, and its employees are encouraged to suggest improvements. The follow-ing hypothesis captures the cost reduction benefits of extent of ABC use:

HYPOTHESIS 2. Extent of ABC use has a significant positive improvement incost.

Extent of ABC use and cycle-time improvement

Under ABC, non-value-added activities (e.g., counting, checking, and moving) arehighlighted (Gerring 1999; Ittner et al. 2002). As a result, ABC can assist in identi-fying activities that cost non-value-added time by providing information needed tominimize delays (Kaplan 1992; Borthick and Roth 1995). Ittner et al. (2002) foundthat ABC use is positively related to decrease in cycle time. Consequently, thefollowing hypothesis is proposed:

HYPOTHESIS 3. Extent of ABC use has a significant positive improvement incycle time.

Quality, cost, and profitability

Quality theorists and practitioners generally support the idea that quality improve-ments result in cost savings that outweigh the money spent on the quality efforts

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 5

(Slaughter, Harter, and Krishnan 1998). Quality outputs may mean lower per unitcosts because of economies of scale (Kroll, Wright, and Heins 1999). This reason-ing is in line with the learning curve theory that suggests that costs should actuallydecline more rapidly with the experience of producing high-quality products (Fine1986). Fine (1983) found that costs declined more rapidly for plants that producedhigh-quality products than for plants that produced low-quality ones. Also, follow-ing the findings of previous empirical work (Noble 1995; Ferdows and De Meyer1990), it can be assumed that the improvements on quality serve as a base for costimprovements because processes become more stable and reliable, and less timeand cost are required for rework. In line with the learning curve theory and withFerdows and De Meyer 1990, the conceptual model proposed in this paper sug-gests that, ceteris paribus, quality improvements will lead to cost improvements.3

Therefore, the following hypothesis is tested:

HYPOTHESIS 4. Ceteris paribus, quality improvement has a significant positiveimprovement in cost.

A quality improvement strategy broadly captures a firm's attempts to differen-tiate itself from its rivals using a variety of marketing and marketing-related activities(Hambrick 1983). Hill (1988) argues that firms may pursue differentiation to buildmarket share under circumstances where the cost savings realized from economiesof scale outweigh the initial investment cost of pursuing a differentiation strategy.The key to making quality improvement successful is an ability to charge abovemarket prices, which is possible because of the customer's perception that theproduct is special in some way (Berman, Wicks, Kotha, and Jones 1999). [AU: Jonesincluded as per References — ok?] This ability to command a premium pricecould, in turn, lead to greater profitability (Kotha and Vadlamani 1995; Porter1980). In addition, quality improvements could lead to greater demand in the mar-ket, which would enhance profitability even if the per unit prices were held con-stant. This implies that, ceteris paribus, improvements in quality have a significantimprovement in profitability.4 Thus:

HYPOTHESIS 5. Ceteris paribus, quality improvement has a significant positiveimprovement in profitability.

Cost-efficiency measures assess the degree to which costs per unit of outputare low (Berman et al. 1999). According to Porter 1980, this strategy of cost effi-ciency entails that the firm be constantly improving its ability to produce at costslower than the competition by emphasizing efficient-scale facilities, vigorouslypursuing cost reductions along the value chain driven by experience, tight cost andoverhead control, and cost minimization (Spanos, Zaralis, and Lioukas 2004; Wu,Lin, and Chen 2007). This strategy of cost efficiency can also provide above-averagereturns because it allows the firm to lower prices to match those of competitors andstill earn profits (Hambrick 1983; Henderson and Henderson 1979; Miller andFriesen 1986; Porter 1980, 1985). To the extent that a firm succeeds in driving

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

6 Contemporary Accounting Research

down costs per unit of output, thereby increasing gross margins, firm profitabilityshould, ceteris paribus, increase (Miller 1987; Porter 1980). Hence, cost improve-ment is expected to transfer businesses’ savings directly to the bottom line (Rust etal. 2002).5 Therefore:

HYPOTHESIS 6. Ceteris paribus, cost improvement has a significant positiveimprovement in profitability.

In summary, what is suggested in the discussion above relating to Hypothesis 4,Hypothesis 5, and Hypothesis 6 is that while quality may be directly and positivelyassociated with profitability (McGuire, Schneeweis, and Branch 1990; Powell1995), its association may also be indirect through cost improvement (Rust et al.2002) because quality firms that enjoy lower costs may lessen the pressure thatmay otherwise be intensely exerted by rivals, customers, suppliers, and firms insubstitute industries (Anderson, Fornell, and Lehmann 1994; Bettis 1983; Fornelland Wernerfelt 1987).

Quality improvement and cycle-time improvement

Quality improvement can be attained by reducing defects and rework (Harter,Krishnan, and Slaughter 2000). The rationale for this argument is that the timespent on preventing and uncovering defects early in the product development stagecan be more than recovered by avoiding rework to correct defects detected at thelater stages of product development (Jones 1997). Empirical research supports thisrationale. For example, in a study of information technology firms, Harter et al.(2000) find that higher-quality products exhibit significant reductions in cycletime. Given that quality and cycle time are known to be complementary — that is,improvements in quality directly relate to improved cycle time (Crosby 1979;Deming 1986; Nandakumar, Datar, and Akella 1993) — we develop the followinghypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 7. Quality improvement has a significant positive improvementin cycle time.

Cycle-time improvement and cost improvement

Achieving cost efficiency is increasingly important in globally competitive markets(Young and Selto 1993). Decreasing cycle time eventually means decreasingnon-value-added time and inventory, thereby lowering product cost (e.g., reducedoverhead). Even if these savings occur through reductions in overall capacity, ifexisting product volume remains constant, unit product costs will decrease (Camp-bell 1995). We therefore conjecture that cycle-time improvement will exhibit apositive association with cost improvement.6 This leads to the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 8. Ceteris paribus, cycle-time improvement has a significantpositive improvement in cost.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 7

Cycle time and profitability

Manufacturers are under pressure to get products to market quickly and stay aheadof competitors (Milligan 1999). Product development research, related to time tomarket, posits that firms compete on new-product-development cycle time as lostprofits accrue when new products are delayed in development and shipped late(Clark 1989). That is, for firms that compete by being first to market with newproducts, being able to develop products faster than competitors supports theorganization’s strategy by enabling quicker response to changing technologies andcustomer demands. Firms that succeed in developing and marketing their productsfaster than competitors can obtain first-mover advantages (Carmel 1995; Gupta,Brockhoff, and Weisenfeld 1992; Kuzmarski 1992), which can allow them to garnerdominant market share (Langerak and Hultink 2005). According to Stalk and Hout1990, “generally, if a time-based competitor can establish a response three or fourtimes faster than its competitors, it will grow at least three times faster than themarket and will be at least twice as profitable as the typical industry competitor.”

The above argument suggests that the focus on cycle time, ceteris paribus,translates into bottom-line profits.7 Therefore:

HYPOTHESIS 9. Ceteris paribus, cycle-time improvement has a significantpositive improvement in profitability.

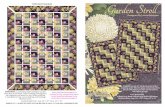

In summary, in this study we explore the relationships among extent of ABCuse, quality improvement, cost improvement, cycle-time improvement, and manu-facturing plant profitability. Figure 1 presents the basic conceptual model, whichuses extent of ABC use as the exogenous construct and quality improvement,cost improvement, cycle-time improvement, and profitability as the endogenousconstructs.

[CATCH — Figure 1 near here]

3. Research design and methods

Variable measures

The constructs are developed on the basis of theory and on items proposed and val-idated in prior studies.8 From these efforts, several items are generated to measurethe different aspects of the constructs. We use a seven-point Likert scale to increasethe sensitivity of the measurement instrument and because we believe that thisscale represents an appropriate measurement instrument for the assumptions offactor analysis used in the analysis of research findings. In addition, the use of aseven-point scale is believed to be appropriate because it is the most common scalein U.S. research (Wolak, Kalafatis, and Harris 1998). Next, the questionnaire wasevaluated by academics at two universities with expertise in accounting, manufac-turing management, and marketing. The constructs and their indicators are discussedin detail in the next section.

The questions used in the survey instrument were substantially borrowed fromthe literature; thus, we did not pretest the instrument as required under Dillman’s

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

8 Contemporary Accounting Research

1978 total design method. This practice is sometime referred to as the modifiedDillman approach and is a survey method common in other accounting research(e.g., Cagwin and Bouwman 2002; Innes and Mitchell 1995; Ittner et al. 2002;Krumwiede 1998). Nevertheless, the use of variables incorrectly assumed to bevalidated in prior studies could lead to incorrect inferences, as discussed later inthis paper.

Extent of ABC use

One would expect the benefits received from an innovation, such as ABC, todepend on the extent to which it becomes incorporated into organizational sub-systems (Cagwin and Bouwman 2002). Therefore, the construct of extent of ABCuse in this study contains the breadth of use. Following Swenson 1995 and Cagwinand Bouwman 2002, we measure this construct by asking respondents to indicatethe extent to which the following functions routinely use the ABC information fordecision making: design engineering, manufacturing engineering, and productmanagement. We also ask the extent to which ABC is used plant-wide.

Plant performance measures

This study uses four latent variables to assess plant performance.9 These measuresare based on prior literature relating to improvement in quality, cost, cycle time,and profitability. The first variable, quality improvement, is based on responsesabout three aspects of product quality: finished product first-pass quality yield inpercentage terms, scrap cost as a percentage of sales, and rework cost as a percent-age of sales (Ittner et al. 2002). We measure the second variable, cost improvement,using four categories of cost borrowed from the literature (e.g., Ittner et al. 2002):materials cost, labor cost, overhead cost, and nonmanufacturing cost. We useresponses in the following four areas to measure cycle-time improvement: newproduct introduction time — the ability to minimize the time to make improve-ments to existing products or to introduce completely new products (Safizadeh,Ritzman, Sharma, and Wood 1996; Vickery, Droge, Yeomank, and Markland1995); manufacturing lead time — the ability to minimize the time from when theorder was released to the shop floor to the time of its completion (Handfield andPannesi 1995); delivery reliability/dependability — the ability to deliver consistentlyon the promised due date (Handheld 1995; Roth and Miller 1990); and customerresponsiveness — the ability to respond in a timely manner to the needs and wantsof customers, including potential customers (Tunc and Gupta 1993; Ward, McCre-ery, Ritzman, and Sharma 1995). Four measures capture improvement in plantprofitability: market share; return on sales (ROS) — net income before corporateexpenses divided by sales; turnover on assets (TOA) — sales divided by totalassets; and return on assets (ROA). Although interdependent, ROA and ROS reflectdifferent determinants of a business success or failure (Kinney and Wempe 2002).Atkinson, Banker, Kaplan, and Young (2001) describe asset turnover as a measureof productivity — the ability to generate sales with a given level of investment —and ROS as a measure of efficiency — the ability to control costs at a given level of

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 9

sales activity. All of these performance measures relate to improvement over theprevious three years.

Sample

To address the hypotheses, we surveyed a cross-section of U.S. manufacturingplants. The plants and firms were identified from a literature review that includedthe Wall Street Journal, Journal of Cost Management, Management Accounting,Harvard Business Review, and various industrial engineering journals and books.The review covered the years 1990–2003. We selected a plant if it was mentionedin the literature as having adopted ABC. We selected a firm as a whole in a similarmanner.

From the literature review, the following steps were taken to collect informa-tion [AU: “information” OK?] from our target sample:

1. In this first step, the literature was reviewed to identify firms that have adoptedABC; if the literature identified a specific plant of a firm as an ABC adopter,we included that plant in our sample. This selection method led to 149 plantsand 57 firms.

2. In the second step, if a firm was mentioned in the literature above as an ABCadopter, a random sample was taken by selecting every third plant from thedirectory listing for each firm (without a priori knowledge of whether the plantselected was an ABC or a non-ABC adopter or if the plant had abandonedABC). [AU: is this “the first mailing”? i.e., contact with firm?] For this sam-ple selection process, we first used the 1997 Industry Week Annual Census ofManufacturers from which Ittner et al. 2002 drew their sample. To update themanagers’ addresses, we used the 2002 Dun and Bradstreet Million Dollardatabase. However, the difference with Ittner et al. 2002 is that we were inter-ested only in ABC implementers.

After submitting the questionnaire to two accounting professors, two manage-ment professors, and two marketing professors for assessment of its validity, thefollowing specific steps were taken: [AU: the following steps imply contact withfirms but there’s no explicit mention of them; include?] (a) sending a secondmailing, (b) promising confidentiality of responses, (c) including deadline datesfor reply, (d) including personalized cover letters, (e) including a postage-paid,self-addressed envelope for reply, and (f) promising to send a summary of resultson request.

As in prior studies (e.g., Ittner and McDuffie 1995; Swanson 2003), question-naires were sent to plant managers as contact persons.10 A cover letter specifiedthat we were interested in plants that are profit centers and that have been usingABC for at least the past three years.11 Initially, 2,506 questionnaires were mailed;within the first three weeks, 686 questionnaires were returned. A second mailingfollowed, and 227 new responses were received. This process resulted in 913responses. Of these, 78 were from plants that had abandoned ABC and 144 were

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

10 Contemporary Accounting Research

incomplete, leaving 691 usable responses, for a 27.57 percent usable response rate(see Table 1).

[CATCH — Table 1 near here]

Nonresponse bias is always a concern in survey research. To investigate thelikelihood of nonresponse bias in the data, we test for statistical differences inthe responses between the early and late waves of survey respondents, with the lastwave of surveys received considered representative of nonrespondents (Armstrongand Overton 1977). The mean scores of the early and late responses are comparedusing t-tests. The t-tests yield no statistically significant differences among the sur-vey items, suggesting that nonresponse bias is not a problem in this study.

Given the reflective nature of the measures used in this study, the analysis ofthe data was done using structural equation modeling (SEM). Reflective measurescontain items that tap into or reflect a pre-existing level on the underlying constructof interest. Reflective indicator items should be correlated with each other, andreflective scales should have high internal reliability, because an individual’sresponses to all the items are influenced by the underlying construct (Diamanto-poulos and Winklhofer 2001; Edwards and Bagozzi 2000; Jarvis, MacKenzie, andPodsakoff 2003). Following previous studies, these measures are treated as reflectiveindicators of existing latent constructs. In evaluating the reflective measurementmodel, we consider path loadings to be acceptable at 0.70 or higher (Limayem,Khalifa, and Chin 2004).

4. Results

In this section, we first present the descriptive statistics. Then we examine theresearch model depicted in Figure 1 using SEM. Numerous researchers have pro-posed a two-stage model-building process when applying SEM (Joreskog andSorbom 1993; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black 1995; Maruyana 1998), inwhich measurement models are tested before testing the structural model. Themeasurement models specify how hypothetical constructs are measured in terms ofobserved variables (Pijpers, Bemelmans, Heemstra and van Montfort 2001; Tan2001), while the structural model depicts the hypothesized relationships betweenlatent constructs. Hence, we examine the measurement model first, then the struc-tural model.

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics in Table 2, panel A provide the profile of the respondingcompanies, showing that they constitute a broad spectrum of manufacturers asdefined by the two-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code. The samplecomposition has the largest representation in electronic and electrical equipment(16.35 percent), followed by paper and allied products (14.04 percent), chemicaland allied products (13.31 percent), food and kindred products (12.01 percent),and apparel and other textile products (9.26 percent). Table 2, panel A also showsthe percentage of targeted sample based on SIC code. Additional information onrespondents’ characteristics is provided in Table 2, panel B. Answers to the ques-

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 11

tion regarding number of years with the manufacturing plant showed that therespondents have a mean of 10.56 years in their current position. To the questionregarding number of years in management, respondents indicated a mean of 17.31years. It appears from their positions and tenure that the respondents are knowl-edgeable and experienced, have access to information on which to base reliableperceptions, and are otherwise well qualified to provide the information required.The results also show that the mean [AU: “mean” per table; change from“average” ok?] number of employees is 947. Next, we calculate their minimum,maximum, mean, and standard deviation for each of the latent variables used in thestudy. Table 3 presents the summary statistics for all the constructs used in this study.

[CATCH — Tables 2 and 3 near here]

The pair-wise correlations in Table 4 show significant correlations betweenextent of ABC use and quality improvement (r � 0.209), cost improvement(r � 0.245), and cycle-time improvement (r � 0.211). Also, significant positivecorrelations are demonstrated between quality improvement and cycle-timeimprovement (r � 0.226), quality improvement and cost improvement (r � 0.486),and cycle-time improvement and cost improvement (r � 0.379). Finally, qualityimprovement, cost improvement, and cycle-time improvement are significantly cor-related with profitability (r � 0.532, 0.539, and 0.674, respectively).

[CATCH — Table 4 near here]

Assessment of the measurement models

Given the reflective nature of the measures used in this study, the data were ana-lyzed using SEM. The SEM procedure allows the researcher to specify both therelationships among the conceptual factors of interest and the measures underlyingeach construct. First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is conducted to examinethe reliability and validity of the proposed constructs. In addition, two importantdimensions of construct validity are assessed: convergent and discriminant validity.In the CFA, convergent validity is examined by reviewing the t-tests for the factorloadings. Hatcher (1994) [AU: please provide page no. for quote] notes that “ifall factor loadings for the indicators measuring the same construct are statisticallysignificant, this is viewed as evidence supporting the convergent validity of thoseindicators”. Table 5 lists the results of the measurement model CFA. It is importantto note that all the indicators are statistically significant (i.e., t-values greater thanthe 1.96 threshold) for large sample at p � 0.05 level and have strong loadings(� 0.70) on their respective latent factors.

Multiple measures have been used to assess model fit. The rule of thumb isthat �2/df should be less than 3.00 (Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, and Summers 1977),while the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and normed fitindex (NFI) should be greater than 0.90 (Bentler and Bonnett 1980), and the resid-ual mean square approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.10 (Kline 1998;Steiger 1990). As shown in Table 5, the final results of CFA indicate that the mea-surement model fits the data reasonably well. The fit indices are � 2/df � 2.751,

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

12 Contemporary Accounting Research

GFI � 0.931, CFI � 0.943, NFI � 0.938, and RMSEA � 0.074.12 The fit loadings,along with t-values, provide evidence of convergent validity.

[CATCH — Table 5 near here]

Next, we assess the discriminant and convergent validity. The average vari-ance extracted (AVE) determines the average variance shared between constructsand its measures and the variance shared between the constructs, which are thesquare correlations between the constructs. To demonstrate the discriminant valid-ity of the constructs, the AVE for each construct should be greater than the squarecorrelations between the constructs and all other constructs (Fornell and Larcker1981). Table 6 shows that the AVE (on diagonal) is greater than the square correlationmatrix (off diagonal) of the constructs. Fornell and Larcker (1981) also suggestthat the AVE can be used to evaluate convergent validity. A test of convergent valid-ity shows that the AVE exceeds 0.50 for all constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981;Chin 1998). Hence, the findings in this study demonstrate high discriminant andconvergent validity.

Reliability estimation is left for last because reliability is almost irrelevant(Torkzadeh, Koufteros, and Doll 2005) unless there are invalid constructs. Toassess the reliability of responses across the measures, we calculated the internalreliability of each construct using two methods: Cronbach's alpha and compositereliability (Djurkovic, McCormack, and Casimir 2006). According to Nunnally’s1978 0.70 criteria for Cronbach’s alpha, all of the scales had satisfactory internalreliability (see Table 6). Composite reliability is similar to Cronbach’s alpha andneeds to exceed 0.70 to indicate satisfactory internal consistency (Gefen, Straub,and Bourdeau 2000). The composite reliabilities for the constructs were satisfac-tory and exceeded the 0.70 acceptable threshold (also shown in Table 6).13

[CATCH — Table 6 near here]

The questionnaire groups questions according to the underlying constructsbeing tested to aid reader understanding. However, control for common methodbiases was accomplished by the design of the study’s procedures (procedural rem-edies), including (a) assuring respondents of anonymity, (b) careful construction ofthe variable constructs (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff 2003), and(c) not requiring responses that were self-incriminating or sensitive. In addition,upon collection of the survey data, the statistical method CFA was used to examinewhether common method bias represented a serious problem. A single-factormodel in which all the model items were assumed to load on one factor was com-pared with a five-factor model in which the construct items were assumed to loadon the scale or factor they represented. It has been suggested that in conducting aCFA to test for the possibility of a common method bias that the best evaluationmeasure is the relative noncentrality index (Gerbing and Anderson 1993). [AU: thisappears as 1988 in References; please correct or add 1993 reference] Theresults of a single-factor model CFA produced a relative noncentrality index of0.352, while the relative noncentrality index for the five-factor model was 0.817.Other evaluation measures (see the assessment of the measurement model above)

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 13

also strongly indicated that the fit for the five-factor model was superior to the single-factor model. These results suggest that the common method bias is not a problemin the study.

Assessment of the structural model and hypotheses

Before testing the hypotheses, it is important to assess the measures of fit. The over-all fit statistics in Table 7 indicate that the model has adequate fit ( �2/df � 2.866,GFI � 0.922, CFI � 0.939, NFI � 0.927, RMSEA � 0.083). This is followed bythe assessment of the hypotheses.

[CATCH — Table 7 near here]

We examine the standardized parameter estimates for our model by usingthe significance of individual path coefficients to evaluate the hypotheses. Consis-tent with theoretical expectations, the standardized parameter estimates indicatethat extent of ABC use is significantly associated with cost improvement (path coef-ficient � 0.171, p � 0.036), quality improvement (path coefficient � 0.205,p � 0.000), and cycle-time improvement (path coefficient � 0.190, p � 0.000).Similarly, the effects of quality improvement on both cost improvement (path coef-ficient � 0.282, p � 0.000) and profitability (path coefficient � 0.223, p � 0.001)are significantly positive. Also, cost improvement is significantly associated withprofitability (path coefficient � 0.690, p � 0.000), and quality improvement issignificantly associated with cycle-time improvement (path coefficient � 0.337,p � 0.000). Finally, cycle-time improvement is significantly associated with bothcost improvement (path coefficient � 0.188, p � 0.000) and profitability (pathcoefficient � 0.191, p � 0.004). Thus, Hypotheses 1 through 9 are supported.Table 7 and Figure 2 show the estimates and significance of the hypothesized pathsfor the conceptual model.

Next, we assess the square multiple correlations (R2), shown in Table 7, whichindicate that the model explains a low amount of variance in cost improvement(0.174), cycle-time improvement (0.175), and quality improvement (0.142), and ahigh amount of variance in profitability (0.743).

The conceptual framework (see Figure 1) suggests that extent of ABC useaffects profitability through quality, cost, and cycle-time improvements that act asintervening variables. To explore this conjecture, we followed recommendationssuggested by Bollen 1989 and others (e.g., Hayduk 1987; Joreskog and Sorbom1993; Medsker, Williams, and Holahan 1994; Quintana and Maxwell 1999).

To test whether extent of ABC use has a significant positive direct associationwith profitability or whether this relationship is achieved through intervening vari-ables (i.e., cost, quality and cycle-time improvements), we first assess the followingconditions: (a) the independent variable, extent of ABC use, must be related to theintervening variables, (b) the intervening variables must be related to the depen-dent variable (i.e., profitability), and (c) the independent variable must have noeffect on the dependent variable when the intervening variables are held constant(Baron and Kenny 1986; Prussia and Kinicki 1996).

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

14 Contemporary Accounting Research

For the first condition, the structural model results show that extent of ABC usehas significant positive improvement in cost, quality, and cycle time (see Table 7and Figure 2). The second condition is also satisfied as the results show that cost,quality, and cycle time have significant positive improvement in profitability (seeTable 7 and Figure 2).

[CATCH — Figure 2 near here]

To evaluate the last condition, between-model comparisons were undertakenusing the �2 difference test recommended by Bollen 1989 and others (e.g., Hayduk1987; Joreskog and Sorbom 1993; Medsker et al. 1994), along with differences inthe fit indices (Gerbing and Anderson 1992; Medsker et al. 1994; Tanaka 1993).More specifically, we test the appropriateness of the research model (nestedmodel) by comparing it to the full model, which includes the direct effect of extentof ABC use on profitability. A �2 difference test between these two models (�2 dif-ference � 1.279, df � 1) indicates no significant difference between them. Thusthe nested model is accepted as the better representation (Joreskog and Sorbom,(1993). Equally important, the lack of significance of the direct paths in the fullmodel (� � 0.05, p � 0.624) provides statistical support for the basic premise ofthis research: that is, extent of ABC use does not have a direct association withprofitability. Rather, extent of ABC use is associated with profitability throughspecified aspects of operational performance measures (quality improvement,cycle-time improvement, and cost improvement) that act as intervening variables.14

[AU: original notes 14 and 15 combined; CAR does not allow immediatelysuccessive notes]

However, the survey approach is not without potential problems. In collectingdata through mail questionnaires, a tradeoff is made with respect to efficiency(e.g., lower cost, time, and staff requirements) versus accuracy (e.g., lower degreeof objectivity in the data). Surveys measure beliefs, which may not always coin-cide with actions (Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal 2005). Surveys lack variablemanipulation (Krumwiede 1998); therefore, "cause" cannot be inferred from thisstudy. In addition, the survey method, as presented in this study, does limit the useof open-ended questions and face-to-face data gathering and the richness such dataprovides. Another potential problem with survey data is that questions, no matterhow carefully crafted, either might not be properly understood or might not elicitthe appropriate information. It is also possible that the survey items may not sur-vive an interpretability test with a set of likely respondents or survive intact after areview using Dillman’s 1978 complete methods. Therefore, the analyses we per-form and conclusions we reach must be interpreted with caution.

As stated above, we did not pretest our variables as required under Dillman’s1978 total design method. Rather, since our variables were used and validated inprior studies (see Appendix), we used a modified Dillman approach, a surveymethod that is common in other accounting research, perhaps due to a presumptionthat published research has gone through a rigorous review process and any qualitycontrols would have been required as a condition of publication (e.g., Cagwin andBouwman 2002; Innes and Mitchell 1995; Ittner et al. 2002; Krumwiede 1998).

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 15

However, to the extent that researchers borrow survey questions from publishedpapers that have not gone through the rigor of pretesting, including interpretabilitytesting, as suggested by Dillman 1978, Forza 2002, and others, this lack of pretestis unfortunate and could potentially lead to incorrect inferences from the datagathered. Given that there is some positive probability that even untested surveyinstruments can provide data of suitable quality to lead to accurate inferences andconclusions, researchers may consider the cost and the benefit of engaging in newresearch programs that remedy old errors by using the most recognized surveytechniques to examine questions that have been examined in earlier publications.An important consideration is that if new research, with adequately tested surveyinstruments, is used and old questions revisited, will it be publishable in top jour-nals if the findings are qualitatively similar to those of the older research, whichused less-than-perfect instruments? Notwithstanding the answer to this question,the questions addressed are so important that it is desirable to at least begin usingthe best methods and techniques available and known to the researchers.

5. Conclusions, limitations, and extensions

With a sample of 691 manufacturing plants, this study uses structural equationmodeling to examine the relationships among extent of ABC use, cost improvement,quality improvement, cycle-time improvement, and profitability. Results indicatethat extent of ABC use is significantly associated with quality improvement, cycle-time improvement, and cost improvement. Quality improvement is significantlyassociated with cycle-time improvement, cost improvement, and profitability.Cycle-time improvement is significantly associated with both cost improvement andprofitability. Also, cost improvement is significantly associated with profitability.Extent of ABC use is not directly associated with plant profitability; rather therelationship is through operational performance measures (quality improvement,cycle-time improvement, and cost improvement) that act as intervening variablesbetween extent of ABC use and profitability.

Hence, this study contributes to the literature by improving our understandingof how ABC improves quality, cost, and cycle time, which, in turn, improve plantprofitability. The importance of improving quality while improving cost and cycletime also becomes critical to managers interested in retaining customers and enticingthem to buy products from their facilities. Thus, this study provides strong evidenceto suggest that ABC implementation efforts by managers generate an increasedtendency toward improved profitability through operational performance (improvedquality, cycle time, and cost). Consequently, management’s ability to utilize bothABC and operational measures to manage their interplay is vital to firm financialsuccess. The framework presented in this paper provides managers with ideasabout how ABC can be successfully implemented. Specifically, within thisframework, managers need to utilize ABC information to make decisions aboutoperational performance measures that are expected to be positively associatedwith firm profitability.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies that suggest that, to be success-ful, companies must be capable of manufacturing products of high quality and/or

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

16 Contemporary Accounting Research

low cost (Drury 1990; Kaplan 1983) and delivering them on time to meet customerdemands (Banker, Porter, and Schroeder 1993). The findings are also consistentwith prior theoretical research, which emphasizes the role of intervening variablesin explaining the relationship between ABC and firm profitability (Chenhall andLangfield-Smith 1998; Kennedy and Affleck-Graves 2001; Shields, Deng, and Kato2000).

The results are of particular interest to practicing and academic accountantsbecause they are often the primary proponents and designers of ABC systems. Theresults are also of particular interest to both manufacturing and marketing managerswho are interested in preserving their quality image in order to influence repeatpurchase activities, while delivering their products on time and controlling theircosts. The importance of meeting customers’ product quality expectations thusbecomes critical to marketing managers interested in retaining and enticing cus-tomers to buy products from them. Hence, the results of this study should enhancepractitioners’ confidence in operational performance as a facilitator of the linkbetween ABC and profitability. We believe that our study model helps to buildintuition about the mechanisms driving these relationships. The model should helpto inform the development of more detailed models and help guide future empiri-cal work with different sampling and industries.

As with any study of this type, our results are subject to a number of limita-tions. First, the correlation between ABC and profitability is not significant, nor isa direct effect. As in Ittner et al. 2002, this may be attributed to the endogenouschoice of ABC. Further studies may investigate the issue of endogeneity, for exam-ple, by estimating the probability that the plant makes extensive use of ABC as afunction of four sets of variables that are not captured in this study.15 Theseinclude product mix and volume, manufacturing practices (discrete and hybrid),new product introductions, and advanced manufacturing practices (Ittner, Lanen,and Larcker 2002). Second, all plants in the study have implemented ABC forthree or more years; however, we do not know the exact length of implementationto assess the time lag effects of extent of ABC use. Further studies can assess themodel variable relationships using and comparing subsamples based on length ofABC adoption. Third, given the difficulty in collecting “harder numbers”, perhapsnot based on respondent perceptions, we have relied on a survey to collect a samplesize large enough for structural equation modeling to test the hypotheses. Furtherinvestigation is warranted using field study methods to corroborate our findings.Fourth, although our research focuses on manufacturing plants, the nature andstrength of the findings suggest that we can extend some of their implications tothe service industry as well. Fifth, our study supports both the direct and indirect(through cost improvements) association between quality and profitability. How-ever, it is worth noting that the return on quality framework (Rust et al. 1995)shows that firms investing in quality improvements contribute to the bottom linethrough two routes. The first pertains to downstream, revenue-enhancing outcomesof increased customer satisfaction (revenue emphasis), while the second pertains tooperational efficiencies and improvements that decrease costs (cost emphasis)(Rust et al. 1995). Therefore, further study is necessary to investigate whether

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 17

firms can achieve profitability through both customer satisfaction and cost reduc-tion. Finally, this study uses perceptual measures for both exogenous and endoge-nous variables. In summary, the challenge for further research is to provideinsights that are relevant and useful for practitioners, to allow managementaccounting research to have more of an impact on practice.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study have implications for boththeory and practice. From a theoretical or research perspective, we are againreminded by this study that organizations are composed of complex sets of interrela-tionships, making it challenging to evaluate the impact of any single managementinnovation and suggesting that the path analytical model is well suited to studiesseeking to learn more about the relationships of variables in complex businessenvironments. Thus, the conjecture by Kennedy and Affleck-Graves 2001 thatABC may enhance profitability only indirectly through its impact on other variablesthat ultimately add value is supported in this research and implies opportunity foradditional research examining more of the rich relationships found in businessorganizations. Management learns from this research that in order to achievegreater returns from their investment in ABC, they must also use ABC to improveboth internal quality drivers and cycle time while using fewer resources to achieveboth of these objectives. Thus, if managers believe that their organization’s strate-gic emphasis must be either on quality or cost improvement, but not both, thenthey may behave suboptimally. In addition, managers who believe that using ABCto drive new quality enhancement initiatives can result in both revenue expansionand cost reduction, the “dual emphasis” according to Rust et al. 1995, can findsupport in this research. Therefore, the findings of this research make importantcontributions to the literature on the ABC–profitability link, to the debate aboutthe belief that organizations must focus on either quality or cost improvement to besuccessful (Porter 1980, 1985) and that attempts to achieve both will leave an orga-nization “stuck in the middle” (Mittal, Sayrak, Tadikamalla, and Anderson 2005),and to the discourse on whether quality improvements can have a positive impacton profits through both revenue enhancements and cost reductions (Rust et al.1995). The good news for managers from this research is that the extent of ABCuse and its financial consequences are to a large degree under their control. However,rather than providing final solutions to a complex puzzle, this research providesimportant signals for a way forward for researchers and managers to makeimprovements in both research and practice.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

18 Contemporary Accounting Research

Appendix

In this project, we are investigating the relationships between extent of ABC use,quality improvement, cost improvement, cycle-time improvement, and profitability.The focus is on manufacturing plants that are profit centers with at least three yearsof ABC adoption.

Please answer the questionnaire (or pass it to the most appropriate personwithin the plant and return it to the address mentioned in the cover letter.

The answers in this questionnaire will be treated in the strictest confidence andno information gained from this survey will be identified with any particular personor manufacturing plant.

Part I.Different overhead cost allocation methods are used in various business set-tings. Of the following three overhead cost allocation methods, please indicatethe method used at your plant (Krumwiede 1998).

A. Individual plant-wide overhead rate: allocates all indirect manufacturingcosts via a single overhead cost rate (e.g., 200% of direct labor, etc.).

B. Departmental or multiple plant-wide overhead rates: allocates all indirectmanufacturing costs using either different rates by department or multiple plant-widerates (e.g., or 66.2 percent).

C. Activity- or Process-based Costing Method (“ABC”): assigns indirectcosts to individual activity or process (rather than departmental) costs pools, thentraces costs to users activities (e.g., products, customers, etc.) based on morethan one cost driver.

Question:Which of the above overhead cost allocation methods (A, B or C) is used at yourplant? Please tick against A, B or C below.

A _________B _________C _________

If you’ve ticked “C” above, please fill out the rest of the questionnaire.Otherwise, please stop and return the questionnaire.

Part II.Below, we seek to assess the extent to which ABC is used at your plant. Forthis purpose, using the survey scale below, please provide the extent to whichthe following functions routinely use the ABC information for decision-makingat your plant (Swenson 1995, Cagwin and Bouwman 2002):

1. Design engineering

Extremelylow use

1

Verylow use

2

Belowaverage use

3

Averageuse4

Aboveaverage use

5

Veryhigh use

6

Extremelyhigh use

7

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 19

2. Manufacturing engineering

3. Product management

4. Plant-wide

Please use the seven-point scale below to indicate the extent to which yourplant has experienced improvement in product cost (direct materials, directlabor, and overhead) and non-manufacturing costs over the last three years(Ittner et al. 2002).

1. Direct materials costs

2. Direct labor costs

3. Overhead costs

4. Non-manufacturing costs

Extremelylow use

1

Verylow use

2

Belowaverage use

3

Averageuse4

Aboveaverage use

5

Veryhigh use

6

Extremelyhigh use

7

Extremelylow use

1

Verylow use

2

Belowaverage use

3

Averageuse4

Aboveaverage use

5

Veryhigh use

6

Extremelyhigh use

7

Extremelylow use

1

Verylow use

2

Belowaverage use

3

Averageuse4

Aboveaverage use

5

Veryhigh use

6

Extremelyhigh use

7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

20 Contemporary Accounting Research

Please use the seven-point scale below to indicate the extent to which yourplant has experienced improvement in quality over the last three years (Ittneret al. 2002):

1. Finished product first pass quality yield in percentage terms

2. Scrap cost as a percentage of sales

3. Rework cost as a percentage of sales

Please use the seven-point scale below to indicate the extent to which yourplant has experienced improvement in cycle time over the last three years:

1. New product introduction time (the ability to minimize the time to make productimprovements / variations to existing products or to introduce completely newproducts) (Safizadeh et al. 1996, Vickery et al. 1995):

2. Manufacturing lead time (the ability to minimize the time from when the orderwas released to the shop floor to the time of its completion) (Handfield and Pannesi1995):

3. Delivery reliability /dependability (the ability to deliver consistently on thepromised due date) (Handheld 1995, Roth and Miller 1990):

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 21

4. Customer responsiveness (the ability to respond in a timely manner to the needsand wants of the plant’s customers including potential customers (Tunc and Gupta1993, Ward et al. 1995):

Please use the seven-point scale below to indicate the extent to which yourplant has experienced improvement in profitability over the last three years(Kinney and Wempe 2002, Atkinson et al. 2001):

1. Market share (of products produced at your plant)

2. Return on sales (net income before corporate expenses divided by sales)

3. Turnover on assets (sales divided by total assets)

4. Return on assets (net income before corporate taxes divided by total assets)

Part III.Please answer the following:1. What is your plant two-digit SIC code? ____________2. Number of years at this position? ___________3. Number of years in management? __________4. What is the number of employees at your plant? ________

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

Extremely low

improvement1

Very lowimprovement

2

Belowaverage

improvement3

Averageimprovement

4

Aboveaverage

improvement5

Very highimprovement

6

Extremely high

improvement7

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

22 Contemporary Accounting Research

Endnotes1. Since its inception, ABC has been mainly used for product costing (Börjesson 1994).

However, its real power lies in its ability to identify cost-reduction opportunities (Cooper and Kaplan 1998; Shank and Govindarajan 1992). The second-generation ABC model has been claimed to contain two dimensions: the cost view and the process view (Cagwin and Bouwman 2002; Mévellec 1990; Lorino 1991; Turney 1991, p. 81). [AU: Turney page no. necessary? it consorts oddly with other references]

2. Shields (1997) reviews management accounting research and calls for a greater use of new research methods, such as structural equation modeling. Smith and Langfield-Smith (2002) review articles in management accounting using structural equation modeling and suggest that there are many potential benefits of its greater use.

3. A “ceteris paribus” environment implies that the net effect of improving quality is to reduce certain, but potentially not all, costs in the value chain. Thus, “ceteris paribus” is used to limit the impact to the variable relationship examined. We show empirically that quality improvements drive costs down in addition to impacting cycle time and profitability directly.

4. A “ceteris paribus” environment implies that an improvement in quality can have a “revenue effect” as defined by Rust et al. 1995, which could include higher absolute or relative prices or stable prices but increases in market share with resulting increases in total margin. The impact of quality enhancements on price elasticity of demand will determine the specific nature of the revenue effect. Thus, the “ceteris paribus” limitation is used to limit the impact to the variable relationship examined and exclude the impact of improvements in quality impacting costs and cycle time.

5. SEM is an iterative, maximum likelihood process with all coefficients estimated simultaneously in each iteration. Thus, cycle time and quality are held constant by being included as predictors of profitability. Hypothesis 6 may be criticized as obvious or even a tautology; however, a tautological relationship would have something predicting itself and would result in an R2 closer to 1. [AU: source of the following quotation? please provide author, year, and page no., and add to the References if necessary] “The presence of cost improvement in the equation gives meaning to the finding that quality improvement and cycle-time improvement make incremental contributions to profitability. So even if Hypothesis 6 is obvious, Cost improvement must be part of this equation — otherwise, the model would be misspecified.”

6. A “ceteris paribus” environment implies that we are limiting the impact of the relationship to the variable(s) examined. It is possible that improvements in costs due to ABC and cycle time, could lead to decreases in costs but not higher profits due to the other variables impacting total costs even more.

7. A “ceteris paribus” environment implies that we are limiting the impact of the relationship to the variable(s) examined. It is possible that improvements in cycle time could lead to increases in profitability independently of the effects of other variables, but those increases could be offset by the negative contribution of other variables on profitability.

8. See the appendix for an abbreviated copy of the research questionnaire used to measure the variables.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 23

9. Prior studies have demonstrated statistically significant correlations between perceptual and corresponding objective measures of performance (Dess and Robinson 1984; Vickery, Droge, and Markland 1997; Ward, Leong, and Boyer 1994; Wall, Michie, Patterson, Wood, Sheehan, Clegg, and West 2004), indicating that perceptual ratings of performance can be considered reliable indicators.

10. Managers were asked to fill out the questionnaire or to forward it to the most appropriate person within the plant.

11. It is expected that three years allows enough time for ABC to be imbedded in the organizations (Krumwiede 1998).

12. While we meet liberal fit measures, it is important to note that more conservative fit indices are � 0.95 and RMSEA is � 0.05).

13. However, a more conservative measure is 0.80 as used in the marketing literature.14. We also ran a one-stage multiple regression model to assess the direct effect of extent

of ABC use on profitability. Results indicate no significant effect. When these relationships are further analyzed within the context of total quality management (TQM) and level of information technology (IT) to determine whether TQM and IT are complementary to ABC use, results show that, overall, manufacturing plants with TQM/high IT perform better than those with non-TQM/low IT.

15. Omitted variables will only cause endogeneity if they are correlated with both ABC and performance.

ReferencesAnderson E. W., C. Fornell, and D. R. Lehmann. 1994. Customer satisfaction, market share,

and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing 58: 53–66. [AU: issue no.?]

Anderson, S. W. 1995. A framework for assessing cost management system changes: The case of activity-based costing implementation at General Motors 1986–1993. Journal of Management Accounting Research 7: 1–51. [AU: issue no.?]

Armitage, H., and G. Russell. 1993. Activity-based management information: TQM's missing link. Cost & Management: 7–12. [AU: volume and issue no.?]

Armstrong, J. S., and T. S. Overton. 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail survey. Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3): 396–421.

Atkinson, A. A., R. D. Banker, R. S. Kaplan, and S. M. Young. 2001. Management Accounting, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Banker, R. D., G. Porter, and R. G. Schroeder. 1993. Reporting manufacturing performance measures to workers: An empirical study. Journal of Management Accounting Research 5: 33–55. [AU: issue no.?]

Baron, R. M., and D. A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [AU: issue no.?]

Bentler, P. M., and D. G. Bonnet. 1980. Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin 88: 588–600.

Berman, S. L., A. C. Wicks, S. Kotha, and T. M. Jones. 1999. Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 42: 488–508. [AU: issue no.?]

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

24 Contemporary Accounting Research

Bettis, R. A. 1983. Modern financial theory, corporate strategy and public policy: Three conundrums. Academy of Management Review 8: 406–15. [AU: issue no.?]

Bollen, K. A. 1989. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.Börjesson, S. 1994. What kind of activity-based information does your purpose require?

Two case studies. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 14 (12): 79–99

Borthick, A. F., and H. P. Roth. 1995. Accounting for time: Reengineering business processes to improve responsiveness. In Readings in Management Accounting, ed. S. M. Young. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bromwich, M., and A. Bhimani. 1989. Management accounting: Evolution, not revolution. London: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants.

Cagwin, D., and M. J. Bouwman. 2002. The association between activity-based costing and improvement in financial performance. Management Accounting Research 13: 1–39. [AU: issue no.?]

Campbell, R. J. 1995. Steering time with ABC or TOC. Management Accounting 76 (7): 1–36.

Carmel, E. 1995. Cycle-time in packages software firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management 12 (2): 110–23.

Carolfi, I. A. 1996. ABM can improve quality and control costs. Cost and Management: 12–6. [AU: volume, page, and issue no.?]

Chenhall, R. H., and K. Langfield-Smith. 1998. The relationship between strategic priorities, management techniques and management accounting: An empirical investigation using a system approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23: 234–64. [AU: issue no.?]

Chin, W. W. 1998. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research, ed. G. A. Marcoulides, 295–336. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Clark, K. B. 1989. Project scope and project performance: The effects of parts strategy and supplier involvement on product development. Management Science 35 (10): 1247–63.

Cooper, R., and R. S. Kaplan. 1991. Profit priorities from activity-based costing. Harvard Business Review: 130–35. [AU: volume and issue no.?]

Cooper, R., and R. S. Kaplan. 1992. Activity-based systems: Measuring the costs of resource usage. Accounting Horizons: 1–19. [AU: volume and issue no.?]

Cooper, R., and R. S. Kaplan. 1998. Cost and effect: Using integrated cost systems to drive profitability and performance. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Cooper, R., R. S. Kaplan, L. Maisel, E. Morrissey, and R. Oehm. 1992. Implementing activity-based cost management. Montvale, NJ: Institute of Management Accountants.

Cooper, R., and R. W. Zmud. 1990. Information technology implementation research: A technological diffusion approach. Management Science 36: 123–39. [AU: issue no.?]

Cronshaw, M., E. Davis., and J. Kay. 1994. On being stuck in the middle or good food costs less at Sainsbury’s. British Journal of Management 5: 19–32. [AU: issue no.?]

Crosby, P. B. 1979. Quality is free. New York: McGraw-Hill.Deming, W. E. 1986. Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Advanced

Engineering.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

Extent of ABC Use and Its Consequences 25

Dess, G. G., and R. B. Robinson Jr. 1984. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal 5 (3): 265–73.

Diamantopoulos, A., and H. M. Winklhofer. 2001. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 269–77.

Dillman, D. A. 1978. Mail and telephone surveys: The total design method. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Djurkovic, N., D. McCormack, and G. Casimir. 2006. Neuroticism and the psychosomatic model of workplace bullying. Journal of Managerial Psychology 21 (1–2): 73–88.

Dodd, G. D., W. K. Lavelle, and S. W. Margolis. 2002. Driving profitability with activity based costing: An executive white paper. Madison, WI: Economy ABC Print.

Drury, C. 1990. Management and cost accounting, 4th ed. London: International Thomas Business Press.

Edwards, J. R., and R. P. Bagozzi. 2000. On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psychological Methods 5 (2): 155–74.

Ferdows, K., and A. De Meyer. 1990. Lasting improvements in manufacturing performance: In search of a new theory. Journal of Operations Management 9 (2): 168–83.

Fine, C. H. 1983. Quality learning and learning in production systems. PhD dissertation, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University.

Fine, C. H. 1986. Quality improvement and learning in productive systems. Management Science 32: 1301–15. [AU: issue no.?]

Fornell, C., and D. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variable and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [AU: issue no.?]

Fornell, C., and B. Wernerfelt. 1987. Defensive marketing strategy by customer complaint management: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research 24: 337–46. [AU: issue no.?]

Forza, C. 2002. Survey research in operations management: A process-based perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 22 (2): 152–95.

Foster G., and D. Swenson 1997. Measuring the success of activity-based costing management and its determinants. Journal of Management Accounting Research 9: 109–41. [AU: issue no.?]

Gefen, D., D. Straub, and M. C. Boudreau. 2000. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the AIS (4:7): 1–70. [AU: please clarify, is this to be “4 (7): 1–70”?]

Gerbing, D. W., and J. C. Anderson. 1988. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research 25: 186–92. [AU: issue no.?]

Gerring, J. 1999. What makes a concept good? A critical framework for understanding concept formation in the social sciences. Polity 31 (3): 357–93.

Gordon, L. A., and K. J. Silvester. 1999. Stock market reactions to activity-based costing adoption. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 18 (3): 229–35.

CAR Vol. 25 No. 2 (Summer 2008)

26 Contemporary Accounting Research

Graham, J. R., C. R. Harvey, and S. Rajgopal. 2005. The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 40: 3–73. [AU: issue no.?]

Gunasekaran, A., and M. Sarhadi. 1998. Implementation of activity-based costing in manufacturing. International Journal of Production Economics 56-57: 231–42. [AU: volume and issue no.?]

Gupta, A. K., K. Brockhoff, and U. Weisenfeld. 1992. Making trade-offs in the new product development process: A German/U.S. comparison. Journal of Product Innovation Management 9 (1): 11–8.

Gupta, M., and K. Galloway. 2003. Activity-based costing/management and its implications for operations management. Technovation 23: 131–8. [AU: issue no.?]

Hair, J. F., Jr., R. E. Anderson, R. J. Tatham, and W. C. Black. 1995. Multivariate data analysis and readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hall, W. K. 1983. Survival strategies in a hostile environment. In Strategic Management, ed. R. G. Hammermesh. New York: Wiley.

Hambrick, D. C. 1983. High profit strategies in mature capital goods industries: A contingency approach. Academy of Management Journal 26: 687–707. [AU: issue no.?]

[AU: Are “Handheld, R. B.” and “Handfield, R. B.” two different people? If not, please correct]

Handheld, R. B. 1995. Re-engineering for time-based competition. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Handfield, R. B., and R. T. Pannesi. 1995. Antecedents of lead-time competitiveness in make-to-order manufacturing firms. International Journal of Production Research 33 (2): 511–37.

Harter, D. E., M. S. Krishnan, and S. A. Slaughter. 2000. Effects of process maturity on quality, cycle-time, and effort in software product development. Management Science 46 (4): 451–66.

Hatcher, L. 1994. A step-by-step approach to using the SAS system for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

Hayduk, L. A. 1987. Structural equation modeling with LISREL: Essentials and advances. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press.

Henderson, B., and D. Henderson. 1979. Corporate strategy. Cambridge, MA: Abt Books.Hill, C. W. L. 1988. Differentiation versus low cost or differentiation and low cost: A

contingency framework. Academy of Management Review 13 (3): 401–12Innes, J., F. Mitchell, and D. Sinclair. 2000. A survey of activity-based costing in the UK’s

largest companies: A comparison of 1994 and 1999 survey results. Management Accounting Research 11: 349–62. [AU: issue no.?]

Innes, J., and F. Mitchell. 1995. A survey of activity-based costing in the U.K.’s largest companies. Management Accounting Research 6 (2): 137–49.

Ittner, C. D. 1999. Activity-based costing concepts for quality improvement. European Management Journal: 492–500. [AU: volume and issue no.?]

Ittner, C. D., and J. P. MacDuffie. 1995. Explaining plant-level differences in manufacturing overhead: Structural and executional cost drivers in the world auto industry. Production and Operations Management 4 (4): 312–34.