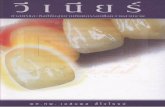

Esthetic dentistry-2001

-

Upload

said-dzhamaldinov -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

94 -

download

0

Transcript of Esthetic dentistry-2001