Three Collaborative Piano Recitals: Schubert's Die schöne ...

Essay_2_Vera_Wolkowicz-Liszt's Edition of Schubert's 'Wanderer' Fantasy - Arrangement or Instructive...

-

Upload

cvrator-harmoniae -

Category

Documents

-

view

27 -

download

1

Transcript of Essay_2_Vera_Wolkowicz-Liszt's Edition of Schubert's 'Wanderer' Fantasy - Arrangement or Instructive...

Vera Wolkowicz 1

Liszt’s Edition of Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy: Arrangement or

Instructive Edition?

Introduction

In 1868 Liszt was commissioned to make an instructive edition of piano works by

Weber and Schubert.1 This edition, published by Cotta, was created as part of an

instructive collection of compositions directed by the pedagogue Sigmund Lebert for

the conservatories of Vienna, Stuttgart and Berlin. The first of Liszt’s volumes

dedicated to Schubert’s work contains the “Wanderer” Fantasy in C major op. 15 and

three sonatas. Liszt makes clear comments on how the edition should be set, and in the

“Wanderer” Fantasy he proposes many changes that exceed a pedagogical instruction

for the pianist. This paper will analyse some of the most salient changes in this edition.

While scholars of Liszt have paid some attention to this edition, studies of

Schubert have so far largely neglected this particular piece. The edition raises questions

of authorial intentions and performance, and clearly we cannot know Schubert’s final

objective for the “Wanderer” Fantasy from this edition. However, an historical analysis

may shed light on how Schubert was performed during the second half of the

nineteenth-century, or at least, how Liszt performed Schubert. Liszt’s changes to the

Fantasy clearly increase the virtuosic demands made of the pianist. This problematizes

the original aims of an “instructive” edition. His abundant remarks of articulations,

dynamics and fingerings, show his willingness to facilitate the work’s performances

however. The uncertainty regarding whether this edition is an arrangement or

instructive may, I believe, have kept scholars from confronting this material.

Lebert’s and Liszt’s “Instructive Edition”

Sigmund Lebert (1822-1884) was a pianist and teacher, co-founder of the Stuttgart

Conservatoire, and co-editor with Ludwig Stark of a piano technique manual called

Grosse Klavierschule.2

He also directed an Instructive Edition of piano works

[Instructive Ausgabe klassischer Klavierwerke] by different composers, on which he

collaborated with other musicians. Besides Liszt, the contributors were Hans von

1 I will coin the term “instructive” instead of “pedagogical” as it is used in the following edition. Franz

Schubert, Franz Schubert: Selected Compositions for the Pianoforte, Instructive Edition, ed. by Franz

Liszt, trans. by Percy Goetschius (New York: Edward Schuberth & Co., 1892). 2 See the footnote in Franz Liszt, Letters of Franz Liszt, ed. by La Mara, trans. by Constance Bache, 2

vols (New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1969), II, p. 154.

Vera Wolkowicz 2

Bülow, Immanuel Faisst and Ignaz Lachner. They edited the piano works of Haydn,

Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, and Schubert, among others.3 In 1868 Liszt was invited by

Lebert and the publishers at Cotta to participate as editor of piano works by Weber and

Schubert, to be included in this Instructive Edition.4 Liszt had a clear idea of the way in

which he wanted to construct the edition, as we read in a letter sent to Lebert in October

of that same year. He writes,

My responsibility with regard to Cotta’s edition of Weber and Schubert I hold

to be: fully and carefully to retain the original text together with provisory

suggestions of my way of rendering it, by means of distinguishing letters,

notes and signs.5

As Alan Walker states, the above comment demonstrates a modern understanding of

music editing in that Liszt distinguishes his own indications from Schubert’s text by

using different typefaces.6

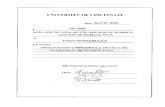

Figure 1. Liszt’s prologue to the Cotta edition.

3 The collection of this edition exists in ten volumes, located in the British Library.

4 See Cotta’s letter to Liszt of March 19, 1868 in Lajos Gracza, “Franz Liszt und das Verlagshaus Cotta in

Stuttgart”, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 45:3/4 (2004), pp. 407-434, p. 411. 5 Liszt, Letters, II, p. 160. Italics preserved from the original.

6 Alan Walker, Reflections on Liszt (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), p. 184.

Vera Wolkowicz 3

Liszt contributed to the Instructive Edition with five volumes of Schubert’s work. The

first two volumes were published in 1871, re-edited and revised again by Liszt in 1875.

The three remaining volumes were published in 1880.7

In the “Wanderer” Fantasy, Liszt made some major changes regarding

Schubert’s text. I was unable to consult the first edition of 1871,8 however, I have used

the second Cotta edition of 1875, and an edition in English translation from 1892,

published by Edward Schuberth & Co.9 The notation of the latter is identical to the 1875

edition, except for a preface by Sigmund Lebert that is missing. This preface, signed

July 1870, was published in the Cotta 1875 copy and presumably written for the 1871

edition.10

Liszt’s source for the “Wanderer” Fantasy

Liszt’s interest in Schubert’s work does not begin with the Cotta edition. Towards the

end of the 1830s Liszt wrote a set of transcriptions of Schubert’s songs for the piano,11

and his interest in the “Wanderer” Fantasy dates back to around 1851, when he

transcribed a version for piano and orchestra.12

Later, he wrote a two piano version

derived from this former transcription.13

According to Humphrey Searle,

7 Maria Eckhardt, “L’édition des oeuvres de Franz Schubert par Franz Liszt. La Fantaisie Wanderer: une

transcription de piano pour piano”, Ostinato Rigore. Revue internationale d’études musicales, No. 18

(2002), pp. 69-84, p. 72. 8 Eckhardt notes that the first edition is lost, but she mentions a letter between Cotta and Liszt, dated June

19, 1871, confirming 1871 as the year of its publication (See Eckhardt, “L’édition”, p. 72, note 12). This

letter can be read in Gracza, “Franz Liszt”, p. 417. 9 The 1875 edition published by Cotta in Stuttgart can be found as section VI of the ten volume collection

held at the British Library. I consulted the Edward Schuberth & Co. edition of 1892 at the library of Jesus

College, Cambridge. 10

There is a contradiction at this point between the catalogues of Liszt’s work. Howard and Short include

in Searle’s catalogue Liszt’s edition of the “Wanderer” Fantasy as S565a, stating that it was first

published in 1870. According to Eckhardt and Charnin Mueller, it was published in 1871. Howard and

Short mention Eckhardt and Charnin Mueller’s catalogue as one of their sources, so that leaves us with

three conjectures: that Howard and Short made a mistake; that they based the date on Lebert’s preface, or

that they were able to see the first edition (the least likely option as it is not mentioned in their sources).

For Eckhardt and Charnin Mueller’s catalogue see Alan Walker, et al., "Liszt, Franz", Grove Music

Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed February 26, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/48265pg28. See also Michael Short

and Leslie Howard, “Ferenc Liszt. List of Works: Comprehensively Expanded from the Catalogue of

Humphrey Searle as Revised by Sharon Winklhofer”, Quaderni dell’Istituto Liszt, Vol. 3 (Milano:

Rugginenti, 2004). 11

Jonathan Kregor, Liszt as Transcriber (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 6. 12

In the foreword to the piano and orchestra transcription, Humphrey Searle states that the first

performance took place on December 14, 1851. Franz Schubert and Franz Liszt, ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy for

piano and orchestra (London: Ernst Eulenburg Ltd., 1980), p. IV. 13

Here again we have a contradiction between the catalogues. Eckhardt and Charnin Mueller state that

the first edition of the piano and orchestra version (LW H13) was published by Spina in Vienna in 1857,

and the two piano version (LW C5) was also published by Spina in 1862. Howard and Short state that the

Vera Wolkowicz 4

Liszt appears to have derived the idea of thematic transformation as a unifying

process from Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy […]. One can see the strong attraction of

this work for Liszt, and many works of his Weimar period follow this model, the

first piano concerto being a particularly clear example.14

Composed in 1822, Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy is known for its difficulty. The

history surrounding the work is that even Schubert was unable to play it well.15

Even

though Liszt wrote two previous transcriptions of the Fantasy, to write an “instructive”

version was an entirely different challenge.

The Instructive Edition presents Schubert’s text, with Liszt’s variants set in a

minor typeface, ossia measures and different types of articulations (see Figure 1).16

Liszt used as his source L. Holle’s edition of Schubert’s Fantasy from 1868.17

The

Fantasy was first published in Vienna in 1823 (during Schubert’s lifetime) by Cappi &

Diabelli, and according to Maurice J. E. Brown the autograph manuscript was lost until

1953.18

The critical edition of the Fantasy in Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher

Werke, is based on Cappi & Diabelli’s first edition and this recovered manuscript, held

in a private collection in Vienna.19

Alan Walker has noted that “Liszt did not have the

luxury of consulting autographs. He worked mainly from first editions”.20

Regarding

the autographs this may be correct, at least regarding the Fantasy, but after comparing

the Fantasy’s first edition, my findings confirm that Liszt did not base his version on the

latter.21

This evidence is grounded in the fact that several articulation marks that Liszt

writes as Schubert’s do not appear in the first edition; moreover there are some

repeatedly omitted accidentals of a same note in different octaves within a same

measure that are fixed in Liszt’s edition without distinguishing them as missing in the

first edition of the piano and orchestra version (S366) was published in Berlin in 1853, and the two piano

version (S653) was first published in Vienna in 1863. 14

Humphrey Searle, The Music of Liszt (New York: Dover Publications, 1966), pp. 60-61. 15

Edmondstoune Duncan, Schubert (London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1934), p. 117. 16

All the figures are taken from the Edward Schuberth & Co. edition of 1892. 17

According to the search made in the Hofmeister XIX database the Holle edition was made by F. W.

Markull. In this database it is also possible to find other editions of the Fantasy published between the

first edition and Liszt’s Instructive Edition. There is a Diabelli edition of 1850, a Breitkopf & Härtel

edition of 1867, and two editions published by Peters from 1868 and 1871. Hofmeister XIX, accessed

March 19, 2013, http://www.hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk. 18

Maurice J. E. Brown, “Schubert: Discoveries of the Last Decade”, The Musical Quarterly, 47:3 (July

1961), pp. 293-314, pp. 308-309. 19

See the section on sources (Quellen und Lesarten) in Franz Schubert, Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe

sämtlicher Werke. Serie VII-Klaviermusik, Abteilung 2: Werke für Klavier zu zwei Händen, Band 5

Klavierstücke II, ed. by Walther Dürr and Christa Landon (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984), p. 157. 20

Walker, Reflections, p. 175. 21

I consulted the 1823 Cappi & Diabelli edition of the Fantasy at the British Library.

Vera Wolkowicz 5

original source. Regarding the manuscript, Brown points out some significant misprints

between this source and its editions that are missing in Liszt’s edition as well.22

Liszt is

explicit about the sources he wants for his edition in two letters, one sent to Lebert, the

other to Cotta, respectively: “The pianoforte Duets of Schubert (Holle’s edition) please

address to Weimar, as I have no time left for revisings in Rome”;23

“L'edition de Holle

(Wolfenbüttel) me suffira pour la revision des oeuvres de Beethowen [sic] et Schubert

[…]”.24

Liszt’s edition of the “Wanderer” Fantasy

There are two types of intervention that Liszt makes in Schubert’s text. The first one

mainly regards the addition of fingerings, pedalings, articulations and dynamics.

Figure 2. Schubert/Liszt “Wanderer” Fantasy op. 15, p. 4, mm. 1-11.

As Figure 2 shows, Liszt marks are in a smaller typeface as we can clearly distinguish,

for example, between the fortissimo of Schubert’s text in measure 1, and the one added

by Liszt in measure 7. Also the articulation marks are written differently (see Figure 1

for the use of staccatos, marcatos, accents), the expression marks have different

thicknesses (compare the one in the right hand in measure 2 with the one in measure 5),

22

Brown, “Schubert”, p. 308. 23

Letter from Villa D’Este of December 2, 1868. See Liszt, Letters, II, p. 166. 24

Letter from Rome of March 28, 1868. See Gracza, “Franz Liszt”, p. 411.

Vera Wolkowicz 6

and as well as fingerings, one of Liszt’s additions is the use of the pedals written in a

smaller size.25

The second type of intervention involves some major changes in Schubert’s text

such us melodic, harmonic,26

and/or rhythmic changes that are written in ossia

measures.

Figure 3. Schubert/Liszt “Wanderer” Fantasy op. 15, p. 14, mm. 161-167.

As we can see in Figure 3, Liszt changes the rhythm of semiquavers, transforming them

in triplets, thus, also modifying the melodic line (instead of an ascending scale, there is

now always a jump of a third at some point of the scale). However, it does not modify

the general concept of what Schubert wrote; by using triplets, it slightly diminishes the

tempo, so as to emphasize a climax point at the arrival of the G major chord (the

dominant) in measure 165, and then continue to a modulatory passage that connects the

first with the second movement.

25

Eckhardt, “L’édition”, p. 77. 26

The harmonic changes do not consist in varying the original harmony, but, for example, in completing

a chord in written octaves.

Vera Wolkowicz 7

It is also possible to observe other major changes, as shown in Figure 4,27

where

ascending and descending arpeggios are replaced by chords in changing octaves with a

completely different rhythmic pattern, modifying Schubert’s original texture.

Figure 4. Schubert/Liszt “Wanderer” Fantasy op. 15, p. 32, mm. 568-571.

The most notorious of Liszt’s interventions occurs in the last movement, where

he decides to print Schubert’s version but instead of using ossia measures, he rewrites

the last movement and prints it separately, following Schubert’s.

27

This Figure only shows a fragment of a larger passage.

Vera Wolkowicz 8

Figure 5. Schubert/Liszt “Wanderer” Fantasy op. 15, p. 35, mm. 631-648.

Vera Wolkowicz 9

Figure 6. Schubert/Liszt “Wanderer” Fantasy op. 15, p. 41, mm. 631-648bis.

Figures 5 and 6 show the same measures of the last movement, and the significant

changes Liszt made to Schubert’s text. Here again, as in Figure 4, Liszt replaces the

arpeggios with chords in changing octaves, and again changes the rhythmic pattern

from semiquavers to triplets in the first nine measures of the right hand, and from

semiquavers to quavers (in octaves) in the left hand of the last two systems. The final

movement is known to be very difficult to play and, although it sounds quite different,

Vera Wolkowicz 10

Liszt facilitates the pianist’s ability to perform the piece by avoiding complex passages

as the ones shown above, while still providing the pianist with some effective writing

that creates a virtuosic effect. It is important to bear in mind that the piano underwent

major changes from Schubert’s to Liszt’s time, and that many of Liszt’s modifications

take into account the new technical possibilities that the piano now offered. He

expresses this in a letter to Lebert: “Several passages, and the whole of the conclusion

of the C major Fantasia, I have re-written in modern pianoforte form, and I flatter

myself that Schubert would not be displeased with it”.28

Some questions on performance and authorial intentions

Liszt’s edition of Schubert’s work has been under-examined in current scholarship.29

Only within the last decade have Liszt scholars paid attention to his role as editor, as we

can observe in the writings of Walker, Eckhardt and Kregor, and the recordings by

Leslie Howard.30

According to Walker, this edition allows us to formulate questions on

performance such as “How did the nineteenth century itself play the music of the

eighteenth? Indeed, how did it play its own music?”31

At least in this case it is possible

to speak of how Liszt played Schubert,32

and this is not a minor issue. In 1997, David

Montgomery published an article where he criticizes Robert Levin’s performance of

Schubert’s Sonatas in A minor D537 and D major D850.33

He claims that the

interpretation of the former goes beyond what is written, while the performance of the

latter is closest to the score. According to Montgomery “Levin would appear to share

with other prominent colleagues the conviction that Schubert’s scores are minimal

documents in need of generous translation”.34

Even though Montgomery is not against

this type of performance, he criticizes that the criteria to play them is not clear. He

refers back to the pedagogical treatises of Schubert’s time in order to explain what an

“historically informed performance” should be. Levin answered this article, publicly

28

Letter from Villa D’Este of December 2, 1868. See Liszt, Letters, II, p. 166. 29

The Instructive Edition is not contemplated either in Schubert’s nor in Liszt’s critical editions. 30

Howard recorded Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy and the Impromptu op. 90 from the Instructive

Edition as part of Liszt’s complete music for solo piano series. See Hyperion-Records, accessed March

21, 2013, http://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/al.asp?al=CDA67203 31

Walker, Reflections, p. 176. 32

We can observe some technical recurrences that Liszt uses in the Instructive Edition of the “Wanderer”

Fantasy, which can also be seen in some piano parts in the transcription for piano and orchestra, where,

instead of playing scales or arpeggios with each hand, they are written to be played with both hands in

alternating octaves. 33

David Montgomery, “Modern Schubert Interpretation in the Light of the Pedagogical Sources of His

Day”, Early Music, 25:1 (February 1997), pp. 100-104; 106-118. 34

Ibid., p. 102.

Vera Wolkowicz 11

replying that “Montgomery would have us believe that in the generation from Mozart to

Schubert the performer ceased to have the creative role characteristic of the earlier

time”.35

Even though Levin has a point, his discourse lacks reference to a closer

historical source that can genuinely endorse his performance. Liszt’s edition might be

that source.

Perhaps the main question that Liszt’s edition of the “Wanderer” Fantasy raises is

one of definition. Is it a transcription; an arrangement; an instructive edition? All these

terms also require defining. Transcription and arrangement are intertwined concepts.

The Oxford Dictionary of Music defines them as synonyms,

Transcription.

(1) Arrangement of musical composition for a performing medium other than the

original or for same medium but in more elaborate style.

(2) Conversion of composition from one system of notation to another.36

Arrangement or Transcription.

Adaptation of a piece of music for a medium other than that for which it was

originally composed. Sometimes ‘Transcription’ means a rewriting for the same

medium but in a style easier to play. (In the USA there appears to be a tendency to

use ‘Arrangement’ for a free treatment of the material and ‘Transcription’ for a more

faithful treatment. In jazz ‘Arrangement’ tends to signify ‘orchestration’).37

As we can see, the definitions are contradictory. In the definition of “transcription” it is

for the same medium but in a more elaborate style; in the second definition

“arrangement or transcription”, the ODM cites that “transcription” means a rewriting

for the same medium but in a style easier to play. We may however be able to establish

that a transcription attempts to replicate the original, while an arrangement maintains

the integrity of the original, while distinguishing itself in its own right. The line between

them, however, is diffuse. According to Kregor, “Liszt understood transcription to be

the creation of difference; that is, an act of violation of – even violence toward – the

35

Robert Levin, “Performance Prerogatives in Schubert”, Early Music, 25:4, 25th Anniversary Issue;

Listening Practice (November 1997), pp. 723-727, p. 723. 36

“Transcription”, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, ed. by Michael Kennedy, 2nd ed., Oxford Music

Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 30, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e10386. Emphasis my own. 37

“Arrangement”, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, ed. by Michael Kennedy, 2nd ed., Oxford Music

Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 30, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e561. Emphasis my own.

Vera Wolkowicz 12

original”.38

This conception of transcription clearly is at a remove from the definition

above. Something similar happens with the concept of a “pedagogical” or “instructive”

edition. An instructive edition would probably involve something that will facilitate the

performance, though it is not clear to what extent, and what parameters should be taken

into account.

These definitions also involve another interwoven question regarding authorial

intention. Which version should be played? Schubert’s; Schubert’s with Liszt’s first

type of intervention; the complete Liszt version (as played by Howard)? Or the

performer’s choice of Schubert’s and Liszt’s? As Kregor states,

A Lisztian transcription, after all, is simultaneously a type of tool for a variety of

projects, an adaptable process, a coming-to-terms with preexisting material usually

engineered by someone else. Thus they inherently exhibit what Roger Parker has

described in operatic production as a ‘surplus of signatures,’ which ‘routinely

involves the dictates not of an authorial intention but of multiple (often vigorously

competing) authorial intentions’.39

In conclusion, it seems that modern scholarship has been reluctant to tackle this

source due to a number of factors: the “multiple and competing” authorial intentions

and thus the impossibility of finding a univocal authorial voice, and the difficulty of

defining this edition as arrangement or instructive. Where Liszt scholars have attempted

to confront the piece’s complexities, it is interesting to assess what has been said about

his role as editor of the “Wanderer” Fantasy. According to Eckhardt, Liszt’s edition is a

“transcription de piano pour le piano”.40

For Walker (talking about Schubert’s

Impromptu in G-flat Major, which can also be applied to the “Wanderer” Fantasy),

“Liszt appears to have temporarily abandoned his role as editor and adopted the mantle

of arranger”.41

Lastly, for Kregor “The editions that Liszt produced for Lebert go far

beyond mere pedagogical instruction”.42

In my own view, the reasons outlined in this paper indicate that this edition is

instructive for the virtuoso piano player. When we consider the complexities and

difficulties of playing this piece, but also understand Liszt’s pedagogical approach, he

does not create an “easier” version, but provides the performer with major technical

details.

38

Kregor, Liszt, p. 4. 39

Kregor, Liszt, p. 2. 40

Eckhardt, “L’édition”, p. 84. 41

Walker, Reflections, p. 186. 42

Kregor, Liszt, p. 164.

Vera Wolkowicz 13

Sources

Hofmeister XIX, accessed March 19, 2013, http://www.hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk.

Dürr, Walther, Christa Landon, et al., eds., Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher

Werke. Serie VII-Klaviermusik, 12 vols (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1972-2011).

Dürr, Walther and Christa Landon, eds., Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher

Werke. Serie VII-Klaviermusik, Abteilung 2: Werke für Klavier zu zwei Händen,

Band 5 Klavierstücke II (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984).

Lebert, Sigmund, ed., Instructive Ausgabe klassischer Klavierwerke. Ausgewählte

Sonaten & Solostücke für das Pianoforte von Franz Schubert. Bearneitet von Franz

Liszt. Revidirte Auflage. Erster Band. Fantasien und Sonaten (Stuttgart: Cotta,

1875).

Liszt, Franz, ed., Franz Schubert: Selected Compositions for the Pianoforte, Instructive

Edition, translated by Percy Goetschius (New York: Edward Schuberth & Co.,

1892).

Schubert, Franz, Fantaisie pour le Piano-Forte, Oeuvre 15 (Vienna: Cappi & Diabelli,

1823).

Schubert, Franz, and Franz Liszt, ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy for piano and orchestra

(London: Ernst Eulenburg Ltd., 1980).

Sulyok, Imre, Imre Mezö, Adrienne Kaczmarczyk, et al., eds., Franz Liszt: Neue

Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke/New Edition of the Complete Works. Serie II: Free

Arrangements and Transcriptions for Piano Solo, 24 vols (Budapest: Editio Musica,

1986-2005).

Bibliography

Badura-Skoda, Paul, “Schubert as Written and as Performed”, The Musical Times,

104:1450 (December 1963), pp. 873-874.

Brown, Maurice J. E., “Schubert: Discoveries of the Last Decade”, The Musical

Quarterly, 47:3 (July 1961), pp. 293-314.

––––––, “Old and Rediscovered Schubert Manuscripts”, Music & Letters, 38:4 (October

1957), pp. 359-368.

Duncan, Edmondstoune, Schubert (London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1934).

Eckhardt, Maria, “L’édition des oeuvres de Franz Schubert par Franz Liszt. La Fantaisie

Wanderer: une transcription de piano pour piano”, Ostinato Rigore. Revue

internationale d’études musicales, No. 18 (2002), pp. 69-84.

Vera Wolkowicz 14

Gracza, Lajos, “Franz Liszt und das Verlagshaus Cotta in Stuttgart”, Studia

Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 45:3/4 (2004), pp. 407-434.

Kennedy, Michael, ed., “Arrangement”, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed.,

Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 30, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e561.

––––––, “Transcription”, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed., Oxford Music

Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 30, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e10386.

Kregor, Jonathan, Liszt as Transcriber (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

La Mara, ed., Letters of Franz Liszt, translated by Constance Bache, 2 vols (New York:

Haskell House Publishers, 1969).

Levin, Robert, “Performance Prerogatives in Schubert”, Early Music, 25:4, 25th

Anniversary Issue; Listening Practice (November 1997), pp. 723-727.

Montgomery, David, “Modern Schubert Interpretation in the Light of the Pedagogical

Sources of His Day”, Early Music, 25:1 (February 1997), pp. 100-104; 106-118.

Searle, Humphrey, The Music of Liszt (New York: Dover Publications, 1966).

Shawe-Taylor, Desmond, Paul Hamburger, Maurits Sillem, et al., “Schubert as Written

and as Performed”, The Musical Times, 104:1447 (September 1963), pp. 626-628.

Short, Michael, and Leslie Howard, “Ferenc Liszt (1811-1886). List of Works:

Comprehensively Expanded from the Catalogue of Humphrey Searle as Revised by

Sharon Winklhofer”, Quaderni dell’Istituto Liszt, Vol. 3 (Milano: Rugginenti, 2004).

Walker, Alan, et al., “Liszt, Franz”, Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford

University Press, accessed February 26, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/48265pg28.

Walker, Alan, Reflections on Liszt (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005).

––––––, Franz Liszt, 3 vols (London: Faber, 1997).

Williams, Adrian, ed., Franz Liszt: Selected Letters (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

Winter, Robert, et al., “Schubert, Franz”, Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

Oxford University Press, accessed February 23, 2013,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/25109pg2.