Essay on the Waldstein sonata by Beethoven.

-

Upload

konstantin-r-bozhinov -

Category

Documents

-

view

44 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Essay on the Waldstein sonata by Beethoven.

-

The Evolution of the First Movement of Beethoven's 'Waldstein' SonataAuthor(s): Barry CooperSource: Music & Letters, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), pp. 170-191Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/734475 .Accessed: 17/02/2014 19:10

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music&Letters.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

THE EVOLUTION OF THE FIRST MOVEMENT OF BEETHOVEN'S

'WALDSTEIN' SONATA BY BARRY COOPER

ANY examination of Beethoven's methods of composition is limited by several considerations. Even in works where ample sketches survive we never know what went on in the composer's head before he started sketching and between each sketch, how long he spent on each sketch, or in what precise order the sketches were written. Nevertheless, where substantial sketches do survive for a work, a detailed study of them can give considerable insight into how it evolved, as has been shown by several recent writers.' Such an investigation is most satisfactory where sketches survive from all stages of composition up to the finished autograph, and where this, too, has been preserved, providing a vital link between earlier sketches and the printed edition. All this material survives for the 'Waldstein' Sonata, unlike most of the earlier sonatas, where the autographs are lost. The 'Waldstein' autograph has even been published in facsimile,2 while what are apparently the complete sketches for all three of the original movements are found on Pp. I20-45 of the 'Eroica' sketchbook,3 though there are no extant sketches for the 'Introduzione' that replaced the original second movement, which was published separately as the 'Andante favori', WoO 57.

The present study is concerned primarily with the first move- ment, but reference will also be made to the other three movements associated with it, where this helps to illuminate a specific problem. The only previous study of the relevant sketches is in Gustav Nottebohm's account of the 'Eroica' sketchbook ;4 but Nottebohm concentrated on the 'Eroica' Symphony itself, devoting only three pages to this sonata movement-and more than half of this space consists of musical examples. Most other writers on the movement, including some who have provided detailed analyses, do not mention the sketches; those that do, refer not to the sketchbook itself but to Nottebohm's account of it.

1 See, for example, Alan Tyson, 'Stages in the Composition of Beethoven's Piano Trio Op. 70, No. I', Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, xcvii (I 970-7 I), I--I 9.

2 The autograph is in the Bodmer Collection, Beethovenhaus, Bonn. The facsimile, in colour, was published by the Beethovenhaus in I954. (Autographs survive for Opp. 26, 27 No. 2 and 28 of the earlier sonatas; the first two of these have also been published in facsimile.)

3 Kno\wn as 'Landsberg 6', this sketchbook has been missing since 1945, but a copy survives on microfilm.

4 Ein Skizzenbucl. von Beethoven aus dem Ja/hre 1803, Leipzig, I88o.

I70

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

It would be possible to consider each section or theme of the movement in turn from its origin to its final version, but it is more useful to consider the movement as a whole at each stage of its evolution. Although it is not always certain whether the order in which the sketches appear in the sketchbook is the order in which they were written down, it seems possible to analyse Beethoven's work on the movement into eight separate stages: (i) preliminary work, sketch fragments and 'concept sketches' for all three original movements; (ii) outline of the whole first movement, followed by a gap in which Beethoven turns his attention to the second and third movements; (iii) intensive work on the development; (iv) a 'con- tinuity draft' for the development, with alternatives for certain bars; (v) continuity draft for the recapitulation; (vi) the same for the coda; (vii) a second attempt at almost the complete coda; (viii) finished autograph. The following table, showing where in the sketchbook each stage of the sketching is found, will help to make this clear.

i. Preliminary sketches p. I 20, lines 9-I6; I 23/I-3, 6-I5, I7

ii. Complete outline I23/I6-I7; I22; I24/I-I I iii. Work on development I 26-7 iv. development I 28; I 29/I8 v. Continuity ) recapitulation I29/I-I4 vi. drafts coda (i) I 30/ I -9 vii. coda (2) I30/I0-I8; I3I/I, i6-i8;

I 32/I -4 viii. Autograph

STAGE I (pp. I 20, I 23) The earliest possible signs of the 'Waldstein' Sonata in the sketch- book are certain scales and keyboard exercises, mostly on two staves, to which Nottebohm has drawn attention.5 Such exercises are common in Beethoven sketchbooks, and the ones here (pp. 96 and I07) may be of no significance. But as they are in I time and mostly in C major, with one in E minor, they could be interpreted as evidence that Beethoven was working towards some kind of piano piece in C major in I time, with E as an important subsidiary key.

The first clear sketches for the sonata are on p. I 20. Staves i-8 contain a sketch for the projected opera Vestas Feuer, at which Beethoven had been working on the previous few pages, but staves 9-I6 are devoted to brief sketches for the first movement of the sonata. The first6 shows Beethoven already concerned not so much with the shape of the first subject as with the problem of how to lead into it at the end of the development--a passage that was to

5Ibid., P. 58. 6 Quoted ibid., p. 59 (Nottebohm's transcription of bars 3 and 4 is conjectural).

I 7I

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

give a great deal of trouble. The other sketches on this page are in E major and seem to be an attempt at a second subject (Ex. i) and material to follow it, though there is little similarity with the final version. The earliest sketches for the Andante (p. I 2 I /8-I 2) are also in E major; Beethoven soon changed this to F, but clearly he had decided at a very early stage that E was to be an important sub- sidiary key in the sonata.

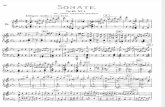

Ex. 1

7u~~ ~~ --A t$ iP

Apart from the Sonata in G, Op. 3I No. i, where the second subject starts in the mediant major but is mostly in the minor, the only other sonata where the mediant major has such prominence iS Op. 2 No. 3, which is also in C major, the slow movement being in E. One ought also to compare the Leonore Overtures 2 and 3 (i 805-6), which are both in C with the second subject in E; and another similar work is the Mass in C (I807), where the 'Christe' section is in E major, using a block-chord theme not unlike that of the 'Waldstein' Sonata. Beethoven seems to have had a special interest in the relationship of E major to C major, and from the start of his work on this sonata he was determined to exploit this interest.

Other apparently early sketches for the sonata appear on p. I23 of the sketchbook. Their fragmentary nature, together with the primitive state of many of them, seems to indicate that at least some of them were made before those on p. I22, which are much more advanced and coherent. Some of the material on p. I 23 is not used at all in later sketches or the autograph-including a very strange sketch in i on stave 4 (Ex. 2), which might have been

Ex. 2

t [?] ,^^t ^#,_ .[?J wb I I mWr Ir r FE W I

intended as a possible theme for the Finale. The sketches with ideas retained up to the autograph-those on staves 6-io and I7- are all of sections that one might expect to cause difficulty: the second subject sketched in the tonic (for the recapitulation); the approach to, and first four bars of, the development; the end of the development; and the extra material incorporated near the start of the recapitulation (bars I67-73 in the final version). The latter

172

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

passage is at this early stage an extended episode of some sixteen bars that wanders into several keys and takes a long time re- establishing the tonic.7 (The final version is remarkably neat and concise by comparison.) As for the C major sketch for the second subject, it shows a slightly different melodic outline from the final version but is actually closer than the one in E major on the opposite page (I22/3), which was evidently written later-this is only four bars long and has the second phrase falling instead of rising. Both versions were superseded by one in the bottom right-hand corner of p. I23 that gives every indication of having been added fairly hastily some time after all the other sketches on these two pages. It is written in a large, bold hand, with different ink from the other sketches, and it is placed at a distance from them. It has the theme as in the final version of the recapitulation-starting in A major and modulating via A minor to C major. This sketch, unlike the others on p. I23, must belong to Stage II or perhaps even later in the compositional process.

STAGE II (pp. I22, I23/I6-I7, I24/ I-' I) The sketches on pp. I22 and I 24 give a broad survey of the whole movement-we find drafts of extended sections from the exposition, development, coda and, by implication, the recapitulation. Not all are set down in the order in which they finally appeared, however: p. I22/I is a sketch for bars 3I-34; I22/2 is of bars 78-82; I22/3 is of bars 35-38 (or possibly 39-42, the second half of the second subject); and the end of stave 3 to stave 5 is an eleven-bar sketch representing bars 66-77 inclusive. Only on stave 6 does Beethoven begin a continuity draft for a substantial portion of the exposition.

The apparently haphazard order of these lines raises several queries. Did Beethoven write down these sketches in the order in which they appear in the movement? This seems hardly likely, as he would not have set them out so illogically. Did he set them down in the same order that appears in the sketchbook? If so, he was thinking through this part of the movement in an odd way. Was he uncertain in what order the elements he had written down would finally appear? This is also hard to believe: they could scarcely appear in any order other than the one they do. A likely explanation is that hewas thinking of the whole of the second half of the exposi- tion at once and writing down any section-beginning, middle or end-which crystallized in his mind. If this is so, then we can see him working at this section from both ends, sketching first the lead-in to the second subject, and the codetta, then the second subject itself and the bars before the codetta, with a gap in the middle which still had to be thought out. At this stage there is no sign of either the triplet figuration of bars 42-57 or the semiquavers of bars 58-65, and

I Quoted ibid., p. 6o.

'73

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Beethoven probably envisaged the missing section as being no longer than about four or five bars.

Having obtained a rough idea of the second half of the exposition, Beethoven is ready on stave 6 to begin a continuity draft for the first half. Clearly he had given far more thought to this than appears in the sketchbook, for he ran straight through 30 bars without stopping and almost without alteration. There are, of course, several differences from the final version. The sketch begins with a semiquaver pattern similar to that of bars I4-I5, rather than with repeated quavers; bars 7-8 appear in the major then in the minor, with the minor version of bar 7 deleted; the figuration of bars 9-IO is less smooth than in the final version; and bar 2I iS missing. But by and large this sketch of the first half of the exposition is already not far from the final version.

By contrast the development sketches that follow (p. I22/II-I4, I5-I 8) are much less advanced; in fact, they are even more primitive than the fragmentary sketches for the second half of the exposition at the top of the page. The first sketch apparently plunges into the middle of the development with a long diminished-seventh arpeggio (Ex. 3) which, though not appearing in the final version, anticipates a similar arpeggio in the Finale (bars 46I-4). After this, triplet figuration is introduced-the first appearance of any triplets in the sketches apart from two bars on p. I23 apparently intended for the coda. But these triplets are undeveloped and occupy only four bars before giving way to semiquaver figuration representing the retransition.

Ex. 3

.7- IFFL19P - _ a i _ _ __ _ _ _etc. I . .

~~~~~~~~I 1 1 pir 6-LV The second development sketch (p. I22/I5 ff.) is an attempt at

a continuity draft for the whole development and on into the recapitulation.8 The first few bars are almost as in the final version, and the next few have a similar harmonic direction, through G minor and C minor to F minor, over an identical time span (I 4 bars). On reaching F (apparently major, though some flats may have been omitted), Beethoven plunges straight into four bars of triplets (Ex. 4); this is followed by a gap (stave I8) which may imply that the four bars are to recur transposed to C. If so, the next part of the sketch-two more bars of triplets and then repeated g" quavers for the right hand-follows on neatly. At the end of the line (D. I22/I8) is written 'Vi-', and the sketch continues at '-le'

' Beethoven clearly regards the development as starting at bar go rather than 86, for this is where the sketch starts and spatially it begins significantly nearer the margin than any other line on the page except the one for the start of the exposition.

I74

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex. 4 ti ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~[sicl

9 r,l , tstl

,_ O _^

P? ? ?

on p. I24/I (this confirms that most of p. I23 must have been filled already with Stage I sketches). In this sketch for the retransi- tion, unlike any others, Beethoven introduces more development material immediately after the beginning of the recapitulation:

Ex. 5

[1.21

1 1 I13

There are no more sketches for the recapitulation at this stage. Beethoven seems already to have decided that it would be perfectly regular apart from the divergence in bars I67-73. The only other problem would be the key of the second subject, which is sorted out on p. I23/i6-I7, as has already been seen. The other sketches on p. I24 are apparently all for the coda. The first two have little cohesion or sense of direction and contain material soon discarded; but the third, an alternative marked 'oder', shows Beethoven already well on the way to the final version. This sketch is worth quoting in full (Ex. 6). The coda here begins in A flat, an easy key to reach from C since the modulation can be the same as that from E to C in the first-time bars of the exposition. The word 'Cadenza' seems to indicate that there is a short episode probably of bravura figuration, the details of which had still to be worked out. Judging by the size of the rest of the coda, one would expect this 'cadenza' to last about ten or twelve bars. The word also betrays the influence of the concerto; this influence is continued in the final bars, which have something of the feeling of a final orchestral ritornello. Since the general shape of this coda sketch is preserved in the final version, it seems legitimate to regard this notion of a cadenza as having survived in bars 259-94 of the sonata as we know it, particularly in

175

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex 6

'i 1 9 1 I nJ 1 IU FE FE M = _ P I. oder 6_ if

FL]. r .q: "[if NWi00b_

A9 i Fri *i_ Cadenza-

Isici

r.i ;i LJ In sc

the passage (barS 278 if.) that begins in classic concerto fashion, with a I chord on the dominant.

By the time Beethoven had finished this sketch he had done a rough outline of the whole movement. To judge by what we know of his procedure in other cases," he would not have found it difficult to make (or at least to begin) an autograph score from these con- tinuity drafts, filling in the occasional gaps and elaborating the figuration. Had he done this, the main difference between this hypothetical score and the actual, autograph would be in length. Making due allow-ancc for bars miissing in the sketches for one reason or another, the length of the movement at this stage was about 190 bars, made up of approximately 6i, 38, 63 and 28 bars respectively for the four sections of the movement. In the final version, however, this has been expanded to 30 2bars (89 +66 +93 + 54).

How do these lengths compare with those of Beethoven's earlier sonatas? The shorter version of about 190o bars is similar to the first movements of many of them (taking into account the varying lengths of bars in different sonatas); it is slightly longer than some, slightly shorter than others, but not sufficiently different to draw attention to itself. But the final version is noticeably longer than any

9 See Lewis Lockwood's discussions on the relationship between Beethoven's sketchbooks and his autographs, in 'On Beethoven's Sketches and Autographs: Some Problems of Defini- tion and Interpretation', Acta Musicologica, xlii (I970), 32-47, and 'Beethoven's Unfinished Piano Concerto of I8I5: Sources and Problems', The Musical Quarterly, lvi (I970), 624-46.

176

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

previous one, just as the 'Eroica' Symphony, sketched earlier in the same sketchbook, is markedly longer than all earlier symphonies, although the early sketches do not suggest that it will be. In many of Beethoven's other works we also find early sketches that suggest much shorter movements than eventually emerged, and it seems to have been the material he was using that forced him to expand movements as he worked on them. He may therefore have ended up with movements much longer than originally planned, or he may have expected such expansion to take place during the course of composition. But either way, the 'Waldstein' Sonata is unusual in that the sketches of Stage II are already of a movement of normal length, even before they had undergone much expansion.

Beethoven seems to have been temporarily satisfied by the sketches of Stage II, anyway, and on p. I25 of the sketchbook he turned his attention to the Andante and Finale, writing 'Rondo' at the head of the page.10 Staves i-6 have Finale sketches, 7-I2 have Andante sketches, and I3-I8 are blank. The Andante is taking shape well, but the Finale is at this stage in I and the theme11 is totally unlike the eventual theme, which had clearly not occurred to Beethoven at this stage.

STAGE III (pp. I26-7) Having had a rest from the first movement on p. I25, Beethoven returned to it on the page-opening I26-7. The movement as it was would have been perfectly adequate as an opening sonata move- ment, but Beethoven was no longer satisfied with what was merely adequate, and his apparent temporary satisfaction, represented by the 'interval' on p. I25, now gives way to renewed determination. He is principally concerned here with the development section, though there are a few sketches for the coda, the Andante and the Finale. The first sketch (staves I-3) is of the start of the development (from bar go), and it was only at this stage that Beethoven replaced the semiquaver figuration of the main theme with repeated quavers

a change which he later carried back to the exposition. In this sketch he reaches F minor after only ten bars, whereas in the previous sketch and the final version this takes fourteen. Staves 5-6 contain an alternative to this sketch (from bar 94) up to bar ioo, where Beethoven has reached C major or minor. Staves 7 and 9 show him trying to develop the motif 4 4n sequence, while on stave 8, marked 'oder', is another idea later discarded (Ex. 7). The lower half of the page is rather fragmentary and is concerned mainly with the coda. Most of the ideas were eventually rejected, but the second attempt at the end of the coda (stave I7) comes close to the final version (see Ex. 8).

10 Both the Andante and the Finale are in rondo form. 11 Quoted in Nottebohm, op. cit., p. 63.

I77

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex. 7

Q oderF L Jletc.-

Ex. 8

Art I r - r v I

The top line of the opposite page (I 27) is also successful: for the first time Beethoven sketches the left hand of bars I 7 I-3 exactly as it will appear in the final version, superseding the long, rambling version we saw on p. I 23.12 Stave 2 has a long scale figure (presum- ably an attempt at the right hand part of the retransition), and on staves 3-7 are more Andante sketches. On stave 8 intensive work begins on the development, the first 7 bars of which are sketched almost as in the final version; the next few bars (97-I03) are omitted, probably because Beethoven had already decided roughly their shape, and sketching is resumed from the end of bar I o3. Previously he had had difficulty in proceeding satisfactorily on reaching F minor, but now he forges ahead confidently, developing the material in a new rhythmic and harmonic pattern as in the autograph.

This takes Beethoven through to bar iii, where the triplet figuration begins. He had already used triplets at this poin:t, in Stage II, but there it was only for about ten bars, which will clearly no longer suffice. The triplet sketches on p. I 27 (staves io, i i and I5, the last apparently a continuation from stave 9) are still confused, however, and do not link together. At this stage, then, Beethoven had decided he wanted an extended triplet section-much longer than he had previously had-but had not sorted out the details of figuration or harmonic progression and how it would all fit together. The triplets are essentially non-thematic: although analysts might say they develop the 'theme' found immediately after the second subject (bar 50 of the expQsition), Beethoven had not sketched this 'theme' at this stage of his work on the triplets in the development. He must therefore have regarded them not in melodic terms but as a rhythmic contrast to the preceding semiquavers, and as a decoration to harmonic progressions that span several bars and might modulate to remote keys. We should be wary of trying to pick out themes from the triplets, either by dividing them into groups or by placing special emphasis on the first of each three or six.

On D. I27/Iq-I4 are two interesting sketches. The first (Ex. 9), 12 See note 7 above.

178

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

,. - _, fi _ I -- - - rf. i tr-

I = .X-%11* I I a

marked 'finis' and intended for the coda, is a very beautiful one, and it is a pity there was no room for it in the final version; but this does contain a development of the idea (bar 26I). The other sketch (Ex. Io), very much on its own in the bottom right-hand corner, is strikingly similar to the theme of the Finale, although it is in I time and seems to belong to the first movement. This raises several interesting questions. Had Beethoven thought of the Finale theme at this stage? Did he notice the similarity, and how close is it? Was this idea incorporated into the first movement? And if so, should one give it special emphasis in performance?

Ex. 10 l

The answer to the first question is that the Finale theme first appears on the page opposite this sketch (p. I26). It is also in the bottom right-hand corner and rather isolated; indeed, both sketches give the impression that they may have been added after the rest of these two pages. They are in a similar kind of graphic style and could well have been written down at about the same time. This suggests that Beethoven did notice their similarity. Even if they were written at different times, both would have been clearly visible at the same time, being on facing pages, and it would have been perfectly natural to look across to the sketch on the correspond- ing part of the opposite page.

Ex. I I shows the Finale sketch. The differences are obvious--in length, pitch, rhythm and range. Yet there are many similarities, especially if the last two bars of Ex. IO are ignored: both passages consist of an eight-beat phrase which is repeated; both have a low first note, a high G on the second beat, and then descend in a type of arpeggio to the lower G on the sixth beat before rising to C on the seventh. The similarity of Ex. io to the final version of the Finale

Ex. 11

'79

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

theme, where the third and fourth notes are G and E, and an extra E is added on the eighth beat, is even greater: not only are four of the seven notes the same pitch (apart from octave transposition), but both themes move in exactly the same direction-up-down-down- down-up-up. It is hard to believe that Beethoven could have overlooked such a close similarity, especially as he was working on both ideas at the same time.

The Finale sketch could easily evolve into its final version, but what happened to the other sketch? On p. I28 it appears again, this time in the middle of a continuity draft for the second half of the development of the first movement, situated just before the return to semiquavers. In the final version of the sonata these six bars become the left-hand part of bars I36-4I; the first two notes are decorated, the e' is replaced by an f'# and the last two bars are slightly different, but it is easily recognisable as the same theme, still moving up-down-down-cown-up-up. If this theme has the importance suggested earlier, it is tempting to give the left hand special emphasis in bars I36-9 while keeping the right hand soft. And the autograph provides evidence to support this interpretation (see Plate I): in bar I 36 Beethoven writes 'f ' beside both" right-hand and left-hand staves at the beginning of the bar, but only one 'p? later in the bar; this is for the right-hand stave, thus implying that the left hand remains loud. Bar I 38 has similar markings. This is a detail that editors of the sonata have in general overlooked. Most editions have just one 'f' at the beginning of the bar and one 'p' between the staves at the end. We can now see from the sketches of Stages III-IV that the leading melody at this point is actually in the left hand, and, from the autograph, that Beethoven wanted this emphasized.

STAGE IV (p. I28)

Stage IV is concerned with continuity drafts for the second half of the development, starting at the triplets of bar i i2. This was the part that still had not been fully worked out in Stage III. The first sketch (p. I28/I-2, 4-6) traces the section right through to bar I42, first with the triplet figuration written out and then, from bar I24, with just the harmonic progressions outlined. Although some of the details of figuration and melodic outline were to be altered sub- stantially in later versions, this sketch is exactly the same length as the passage in the final version, and moreover every bar is essentially the same harmonically. We find here for the first time harmonic progressions such as the one to E flat minor and the enharmonic change to B minor. Nevertheless the latter part of this sketch (from bar I23) is deleted in favour of a substitute on staves I0-I3, which has a slightly different melodic pattern for the left hand while keeping the same harmonies.

This second sketch carries on into the retransition and thence to

I8o

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

..........u ~ . 'V~~~~~~~~~.

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

the start of the recapitulation (bar I56). It shows that Beethoven wanted to build, on a dominant pedal, a right-hand part that would rise to high f"', hover there briefly and plunge down rapidly, without pause, into the recapitulation. The details of this needed to be worked out very carefully, however; Beethoven had already sketched the end of the retransition several times at earlier stages (on pp. I20, I22, I23, I24 and twice on I27), which shows that he was particularly concerned about it, that he was aware that it was giving difficulty, and that although he had decided on the left hand motif from the outset (p. I 20) and the rising and plunging shape of the right hand from soon after, he still had no clear vision of the length or rhythmic details of the retransition. At the present stage he was working on the link between bar I42, where his development sketches had now reached, and his previous sketches for the last two or three bars of the retransition.

The substitute sketch (staves I2-I 3) is very close to the final version but three bars shorter--eleven instead of fourteen (bars I42-55)---with the right hand rising to a top f"' quite rapidly (Ex. I2). On stave I 4 is an even shorter version of only ten bars. On staves i6-i8, still not satisfied, Beethoven tries something quite different: on reaching the dominant at bar I42, instead of retaining it he interpolates some further development of the rhythmic figures of bars 3 and 4, moving into D minor then gradually back to a G chord which becomes the dominant seventh as in previous sketches (a total of 24 bars). In the end none of these three versions was adopted; there are no sketches coinciding with the final version. Beethoven had produced several reasonably satisfactory versions of the basic shape of the retransition, ranging from about ten to twenty bars, and it is precisely because of this that he spends so long in deciding which to adopt. He seems to be hunting for some- thing neat and concise, yet sufficiently long and weighty to serve as a preparation for the recapitulation. The 24-bar version is too long, while the ten-bar one is too short and square, and brings in the seventh of the chord too early. Only when Beethoven comes to write the autograph does he find exactly the right balance between the two extremes. Ex. 12

r n ~ !i r -,J - 1 . , ,, I jP 1 1 F

4w i . F, 1 JF

l-'J~ ~~~ -I q- 1 :

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

STAGE V (p. I29/I-14) Having more or' less worked oiut the development, Beethoven turns his atten'tion to a continuity draft for the recapitulation on p. 129. This can be sketched quite quickly since it is largely regular and since a continuity draft already' existed for much of the exposition. This is followed quite closely, with the interpolation at bars I67-73 now fitting in perfectly easily. Strangely, Beethoven does not detail the divergence from the exposition that takes place at bars I8I-3 but just writes three blank bars, as if he knows roughly how he is going to consolidate the modulation to A'minor. The preparation for the second subject is sketched in fully, but the actual four-bar lead-in differs from the final version in being much squarer and rhythmically more obvious (Ex. 13). The final version of these four bars is, of course, very ingenious in the way it effectively disguises the four-square outline by means of overlapping and irregular phrase-lengths.

Ea. 13_r ti^ _

_ . u _ wr _ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- 70 -__ ___

The second subject is sketched complete but the triplet elabora- tion of it is represented largely by blank bars- Beethoven need not write out what is really a very simple decoration of a theme he has just written down. The triplet patterns of bars 2 I -I8 now appear in their diatonic form for the first time. As noted already, in the short version of the' movement (Stage II, p. I22) there were no triplets in the exposition and only a few in the development. But subsequent' work on the development resulted in an extended triplet section; now Beethoven, working backwards as it were, inserts triplets into the recapitulation (and by implication into the exposition too). Much of the remainder of this continuity draft is not derived from previous sketches, but it proceeds without any 'Vi-de' markings and almost without alteration'up to the end of the recapitulation (bar 248), which is reached on stave I4.

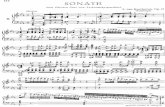

STAGE VI (p I 30/1-9) Beethoven clearly regards the coda (bars 249-302) as a separate stage of composition, for he begins a continuity draft for this on a new page rather than continuing on p. I 29 beneath the recapitula- tion. This coda sketch begins in D flat, as in the autograph (the previous coda sketch had begun in A flat). Its general outlines are similar to those of the final version but there are several important differences. As this sketch seems to show the sort of coda Beethoven

I82

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

might have written had he felt unable to use notes above f"t',13 and for purposes of comparison with the final version, it is quoted in full (Ex. 14).

Ex. 14

I I

f @ Wf lgr > IrffX prlErf>

[t?]= rXt:XrE:ftWniiD:b;:LFriLWJ

rBr:S2vlJ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~_ gol a el rECffFt

[W] C r Cl o Il S; 1[>]? Laft :rS g

[ '2:' 2 l4> > lr f - Ir $ r $ If $ -~~~~~~~~~

13 This is the first sonata to take account of the extended compass (to c"") of the Erard piano sent to Beethoven in the summer of I803.

I83

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

STAGE VII (pp. I30-32) Underneath this coda sketch, on p. I 30/ I 0-I 4, and also on p. I 3 I / I, are further short ideas for the coda. The one on p. I3I, which contains an idea eventually rejected (Ex. I5), is notable as it includes a high g"'. Below this sketch are some Andante sketches (p. I3 /2-I 5), and after Beethoven had made these he filled in the bottom four lines of p. I 30 and the bottom three of p. I 3 I (continuing overleaf to p. I32/I) with a second continuity draft for the coda, deleting all but the first three bars of the previous coda draft. This second draft also contains high notes-a top a"' followed by top g"' (p. I 3 I / I 6; see bar 276 of the final version).

Ex. 15

~~~~~~~~O PF; I ,D 1A

I e./

lThe appearance of these high notes is of considerable interest. Before Stage VII there are no clear examples of any notes abovef"'. One note on p. I22/I looks like anf '", but it could be a d "'p, which would make equal musical sense. There is also a section in the recapitulation sketch (bars 229-34) where higher notes are implied, and are indeed used in the autograph, but this, too, proves nothing, for there are many such implications in sketches for earlier sonatas, where the printed edition avoids them somehow-often rather uncomfortably. Thus evidence that Beethoven might have envisaged occasionally using higher notes is flimsy, and against it must be set these facts: (a) up to p. I30 there has not been a single high g "', though this would be an obvious note for a C major sonata (it often appears in Finale sketches after p. 131); (b) high f"' frequently occurs, which might imply that this was the highest note on the keyboard and that Beethoven had devised a sonata that would fit the compass exactly; (c) certain figurations that might naturally have used the higher notes, for example the diminished seventh arpeggio of Ex. 3, turn back on themselves as if restricted by the compass of the keyboard. Thus the evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that Beethoven did not initially intend to use notes above f"', and it was only at Stage VII, when he came to revise the coda sketch, that he at last admitted them.

Can we deduce from this that the Erard piano arrived when Beethoven had completed Stage VI, and induced him to revise the coda to take advantage of the higher notes? Here we must turn to external evidence. It is known fromtn the archives of the Erard firm that Beethoven was sent one of tiheir pianos on 6 August i803.14

14 See Thayer's Life of Beethoven, ed. Elliot Forbes, Princeton, I964, i. 335.

184

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

To date the sketches, however, it is necessary to consider where they stand in relation to sketches for other works composed about the same time. Work on the sonata as a whole occupies pp. 120-145 of the sketchbook; practically nothing else is found on these pages. Scattered over pp. 96-I20 (only) are sketches for part of Vestas Feuer; and from p. I46 onwards are the first sketches for Leonore. Since the sonata fits so exactly into the pages between these two works, with neither any gap nor any overlap (indeed the sketches for Vestas Feuer stop on p. 12o/8 and those for the sonata begin on p. I 20/9), it is highly probable that the sonata was not begun until about the time Beethoven abandoned Vestas Feuer, and that it was fully sketched by about the time he began work on Leonore.

Beethoven undertook to write Vestas Feuer in the spring of I803, but he made a slow start, for we read in a letter dated 2 November I803, 'I am only now beginning to work at my opera'.15 He never really got beyond the 'beginning' stage, but the implication is that he would not have reached p. I 20 at the date of the letter. By the end of the year, however, he had returned the libretto to Schikaneder (its author), and in a letter dated 4 January I804 he writes: 'I have quickly had an old French libretto adapted and am now beginning to work on it'.16

If the 'Waldstein' Sonata was sketched in its entirety between the time Beethoven abandoned Vestas Feuer and the time he began Leonore, the outer date limits must be 2 November I 803 and 4January I 804. He therefore had the upper notes of the Erard piano available throughout the time of sketching the sonata, and yet did two com- plete sketches of the first movement, plus several short sketches for the last two, without using these notes. But one must remember that Beethoven was not writing purely for instruments in his own possession, nor was his piano the only one in Vienna with the larger compass. Such pianos, some actually made in Vienna, were gradually becoming more and more common at the time,17 and so Beethoven would have been bound to decide at some point that they were now sufficiently plentiful for him to risk using the extra notes that he wanted. He seems to have made this decision, as we now see, when he reached pp. I30-3I of the sketchbook, by which time he had almost finished sketching the first movement of this sonata.

This second draft of the coda on p. I 30 differs in many ways from the first. The first was one bar longer than the final version, but this sketch is longer still, having bars 249-52 repeated in E flat minor (going to B flat minor) before proceeding with material correspond- ing to bars 253 if. This time the right hand is sketched for bars 255-8, and this fits with the previous draft (which showed the left hand),

15 The Letters of Beethoven, trans. and ed. Emily Anderson, London, I96I, i. ioo. 16 Ibid., i. I05-6. 17 See William Newman, 'Beethoven's Pianos versus his Piano Ideals', Journal of the

American Musicological Society, xxiii (0970), 492.

I85

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

though both differ slightly from the final version. Thereafter there are two main sections that differ from the previous coda sketch: one is the' passage bars 271-82, which is now better organised and has a clearer sense of direction; the other is the cadence at bars 288-95, which is altered and extended by four bars."'

STAGE VIiI (Autograph) Beethoven was now ready to write out the autograph without, apparently, making any more sketches for the movement, and it would have been possible to work directly from the sketchbook drafts, incorporating any alterations he had decided on mentally since making the sketches. The autograph of the first imovement has very few deletions, showing that Beethoven had a clear 'idea of almost all the details before writing it out. By contrast the 'Intro- duzione' which replaced the original second movement has numer- ous alterations, deletions and 'Vi-de' marks. No sketches survive for it, as we have already observed. Did Beethoven write it without any preliminary sketching?

The autograph of the exposition has, in addition to many minor differences from the only continuity draft for it-differences such as the addition of grace-notes in bar 4 and so on-several alterations of fundamental ideas. These include the substitution of repeated quavers for a semiquaver tremolo in bars J-2 and a more continuous semiquaver figuration in bar i i. Many of the alterations, however, including these two, can be found as early as the continuity draft for the recapitulation, and so we must deduce that, when writing out the autograph of the exposition, Beethove n worked not from exposition sketches but from the sketch for the recapitulation. This would have caused no problem as the recapitulation is almost entirely regular.

The first half of the development (bars 90-iII) follows the sketches closely too; a few of the right-hand motifs are a third higher or transposed up or down an octave, but there are no other significant differences. In the second half of the development Beethoven had harmonically speaking reached the final version of bars i I2-42 at Stage IV, as'we have seen, so when he wrote the autograph he had merely to work out the details of the triplet figuration, which he presumably considered relati7vely unimportant. We have also seen that he draws attention to the left-hand part of bars 136-9, and that he had made numerous unsuccessful attempts at the retransition (bars 142-55). In the autograph bars i42-6 follow one of the sketches (p. I 28), but bars 147-5 I differ considerably from anything in the sketchbook. Beethoven may have sketched these bars separ- ately on some scrap of paper, now' lost, immediately before writing out the autograph. This supposition is perhaps strengthened by a

18 Quoted in Nottebohm, op.cit., p. 6o.

i86

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

pencil sign at the end of bar 146 of the autograph, which might be a reminder to switch from one sketch to another at this point. Bars 152-5 show only minor differences from the sketches.

The recapitulation is almost entirely predictable, if we bear in mind that it would more or less match the exposition except in the few places that the sketches indicate it will not. The coda (bars 249-302), however, shows several new ideas. There had been two continuity drafts for it, one of which was crossed out, but the autograph coda is something of an amalgam, drawing sometimes on one, sometimes the other, sometimes both (where they coincide) and sometimes neither. Bars 249-54 follow the earlier draft, but bars 255-8 differ slightly from both drafts. Bars 259 and 26I-70 follow both, while bar 260 follows just the later one; bars 27 i-6 approximate to the later sketch but are very different from the earlier one; bars 27 7-83 are considerably different from either draft, though much closer to the later; bars 284-9 follow both sketches; bars 2go-6 follow the earlier but are very different from the later; and bars 297-302 more or less coincide with both versions. Thus it would not have been strictly necessary for Beethoven to write out a draft matching the final version of the coda, for he had written down almost all the material already. But he must have thought hard about the overall shape of it, and considered mentally the various options available, before deciding exactly which com- bination of ideas to adopt in the autograph.

All that remains to be considered now is the alterations to the autograph itself. They can be grouped into three basic types. In the first type there is no change of actual concept: either Beethoven writes down something he does not intend, through carelessness, or else because of some notational difficulty he realises that what he has written or is writing is not entirely clear. A surprisingly large number of alterations come into this category, and in general all alterations should first be considered for this possibility, before they are regarded as compositional adjustments."' An example of carelessness is the first left-hand note of bar I 72, where Beethoven writes an ab and has to alter it tof, which had already been decided on in the sketchbook. The greatest notational problems come in the left-hand parts of bars II4 and iI8, where although the idea is simple the notation has to be quite complex; both these bars are crossed out and rewritten, though by the time the figure reappears in bar I22 the difficulty has been overcome. It is not always abso- lutely certain whefher a correction is of this first type or not, but

For example, the alterations in Op. 26 to which Lewis Lockwood has devoted so much attention (see 'On Beethoven's Sketches and Autographs', p. 32) are probably of this type. It would have been easy for Beethoven to alter what Lockwood calls 'A I' to 'A 2' simply by adding an upward crotchet tail to the Ab and filling in the bass; but by the time Beethoven got as far as he did with 'A I' he probably realised that adding an upwAard tail would look confusing when followed by the next bar, where he wanted a downward tail to the Ab Which would be tied to the previous Ab. Thus rather than allow this he preferred to write out the bar again with the tails pointing in the opposite direction.

i87

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

there seem to be at least ten examples in the movement-in bars 46, 73, 90, I 04, I I 4, I I 8, I 30, I 66, I 72 and 288 (first alteration).

The second type is the simple change of mind, without any direct link with the sketchbook. The change may be made immediately or it may be made much later-conceivably even some weeks after the autograph has been finished. The alteration to bar 42, for ex- ample, must have been made immediately, for the earlier version, which had a different triplet pattern, is deleted and the whole bar is written out immediately afterwards, before bar 43. The change in the left hand in bar 27, however, where the notes B-e-g-b are replaced by a#-b-g-e, must have been made somewhat later, for the earlier version is still found in the recapitulation and is similarly altered. Other alterations that can be classed as 'simple changes' are those in bars i8, 96, two in 229 (both right hand) and 246. The latter is interesting: Beethoven initially wrote a first-time bar and a repeat of the entire development and recapitulation, but there is no sign of this intention in the sketches.

The third type, perhaps the most interesting, is where the earlier version coincides with the continuity draft in the sketchbook. In these cases Beethoven could either have deliberately copied the sketch and then decided to make an alteration, or have decided on a new version but temporarily forgotten about it while copying from the sketchbook. This type of alteration is rare-there are only three in the whole movement. The first is in bar 25, where in the right hand Beethoven initially writes a crotchet b" tied to a semiquaver, as in bar 23. This version appears in the sketches for both the exposi- tion (p. I 22/9) and the recapitulation (p. I29/4); only after this is copied into the autograph does he decide that it is better to let the music run on with continuous semiquavers in the right hand. The amendment must have been made fairly promptly, for the earlier version does not appear in the autograph of the recapitulation. The second case is in the left hand of bars 228-30, where in the earlier version the quaver passage is begun on a g (Ex. I 6). This is as in the

Ex. 16

sketchbook (p. I 29/ I I), though this version had not been used in the exposition and presumably would not have been intended in the recapitulation. Probably Beethoven copied the passage directly from the sketchbook before realising he had wanted a slightly lower version. The other example of an alteration in this third type is the substitution of a'4 for a't in bar 239. In the sketch, bars 235-8 were in the major and 239-42 in the minor; in the autograph 235-8 are in the minor and Beethoven begins the next four bars in

i 88

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

the minor, either deliberately or through following the sketchbook too closely, before altering it to major. The a'Q's in bar 240 are clearly marked and are not altered from flats.

These three alterations of the third type show how closely the final continuity draft is related to the autograph. In all probability Beethoven had the sketchbook open in front of him when writing out the autograph. The only real alteration from still later was the substitution ofJ for j in the left hand in bar I05; this happened after the music had been engraved, at the proof stage, as is clear from marks at this point in the original edition.20

It seems reasonable to assume that the most important features of the movement were generally those Beethoven conceived first, and that towards the end of his work he was concerned mainly with sorting out minor details. Two principal features of the movement are therefore the contrast between the key areas of C and E, and the nature of the retransition, which is most unusual in building up toff and then plunging without pause straight into a pp recapitulation. Both features are present from the very start; the basic outline of the retransition is present in all the sketches for it, and it is just the precise details, and the length, that took so long to work out. A similar order of priorities is visible in other parts of the movement-- for example, the melodic shape of the development triplets is less important than the fact that this is a rhythmic contrast to the first half of the development.

But although Beethoven begins by working on basic fragments, and later fills in details of figuration, he can also be seen to work through the movement in four sections, from exposition to coda. The analysis of sonata movements into four sections is so funda- mental that composers are more or less obliged to work at four independent compositional problems. Thus in this movement pp. I20 and I23 are mainly fragments; p. I22 is mainly on the exposition and development; p. I24 consists of more fragments (mainly links); pp. I26-8 are devoted mainly to the development; p. I29 contains the recapitulation and pp. I 30-32 have coda sketches. Once a section is sketched more or less complete it is usually abandoned until the autograph; we find no exposition sketches after p. I22, very few development sketches after p. I28 and no recapitulation sketches after p. I29. The development comes nearest to upsetting this scheme, for parts of it needed several sketches. It was clearly the most difficult part to compose not surprisingly since, unlike the exposition, there was no set plan for the composer to follow. Beethoven also worked through the three movements roughly in order; he did not simply allocate a different

20 See Dagmar Weise, 'Zum Faksimiledruck von Beethovens Waldsteinsonate', Beethoven- Jahrbuch, ii (1955-6), 102-I I.

I 89

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

part of the sketchbook to each, for there are a few sketches for the last two movements mixed up with the main work on the first.

Several other points have emerged from this study. For the performer the most significant is probably the discovery that in bars I36-9 the left hand has the tune and should be played forte throughout. For the analyst there is the likelihood that these bars are directly related to the Finale theme, even if the exact nature of the relationship is uncertain. (A possible interpretation, for example, is that Beethoven's work on these bars, moving away from his original idea, affected his work on the Finale theme, which develops towards the shape of this sketch. Details rejected in one movement can be successfully adapted in another.) The analyst should also consider the influence of the concerto on this movement. Several writers have commented on the concerto-like style of some sections--for example the second subject, which is stated in a quasi-orchestral version and repeated with pianistic decorations-- and the movement could almost be analysed on ritornello principles. To these features can now be added the cadenza actually labelled in the sketchbook. Another analytical point is that the contrast between bars i and I 4 is essentially one of register, not of figuration; Beethoven originally sketched the opening as a semiquaver tremolo and only altered it halfway through the sketches--presumably because such rapid figuration at such a low pitch would lack clarity.

The first movement is considerably longer than in any previous piano sonata, yet this was not conceived as a primary feature, for continuity drafts on pp. I22-4 clearly represent a much shorter movement. Indeed Beethoven seems to have been temporarily satisfied with this, for he turned his attention to the second and third movements on p. I 25. When he returned to the first movement on p. I 26 it was primarily to the development, which had previously been the least satisfactory part of the movement, and this was the section to which most attention was given in the sketches as a whole. Beethoven found the main themes of the movement fairly easily but had trouble over the non-thematic parts, which include most of the development; he was well rewarded, however, for the development is a magnificent piece of expansive writing in which the material slowly unfolds over a relentless rhythmic drive that allows not a single proper breathing space throughout. And it seems to have been the expansion of the development that really deter- mined the eventual size of the movement as a whole; its long triplet section demanded balancing sections in the exposition and recapitulation. Beethoven's preliminary work on the other two movements--especially the Andante--on pp. I2 i and I 25, may also have influenced the size of the first movement. As well as increased length there is the increased keyboard compass required, the highest note being a"' (not until the 'Appassionata', Op. 57, did he

I 90

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

require a top c""). But as we have seen, this cannot be directly related to his Erard piano since this probably arrived several months before the earliest sketches, which do not use the higher notes.

Many of the conclusions reached contain an element of conjec- ture; far more must have taken place in Beethoven's mind than is written down on paper. Yet however skeletal the sketches and even the autograph are from this point of view, they show certain definite features from which reasonable deductions may be made about their most probable interpretation.21

21 I should like to acknowledge the generous assistance given by ProfessorJoseph Kerman and Dr. Alan Tyson in the preparation of this article.

I () I

This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Mon, 17 Feb 2014 19:10:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Article Contentsp. 170p. 171p. 172p. 173p. 174p. 175p. 176p. 177p. 178p. 179p. 180[unnumbered]p. 181p. 182p. 183p. 184p. 185p. 186p. 187p. 188p. 189p. 190p. 191

Issue Table of ContentsMusic & Letters, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), pp. 127-268Front MatterThe First Version of Beethoven's G Major String Quartet, Op. 18 No. 2 [pp. 127-152]Antonie Brentano and Beethoven [pp. 153-169]The Evolution of the First Movement of Beethoven's 'Waldstein' Sonata [pp. 170-191]Yet Another 'Leonore' Overture? [pp. 192-203]Notes on the Sources of Beethoven's Opus 111 [pp. 204-215]Reviews of BooksReview: untitled [pp. 216]Review: untitled [pp. 217-218]Review: untitled [pp. 218-219]Review: untitled [pp. 219-222]Review: untitled [pp. 223-224]Review: untitled [pp. 225-226]Review: untitled [pp. 226-227]Review: untitled [pp. 227-228]Review: untitled [pp. 228-229]Review: untitled [pp. 229-230]Review: untitled [pp. 230-232]Review: untitled [pp. 232-234]Review: untitled [pp. 234-235]

Reviews of MusicReview: untitled [pp. 236-240]Review: untitled [pp. 240]Review: untitled [pp. 241-242]Review: untitled [pp. 242-244]Review: untitled [pp. 244-245]Review: untitled [pp. 246]Review: untitled [pp. 247]Review: untitled [pp. 247-249]Review: untitled [pp. 249-250]Review: untitled [pp. 250-251]Review: untitled [pp. 251]Trio Sonatas [pp. 252]Review: untitled [pp. 252-253]Review: untitled [pp. 253-254]Review: untitled [pp. 254]Review: untitled [pp. 255]Review: untitled [pp. 255-256]Review: untitled [pp. 256-257]Living British Composers: Central Music Library Scheme [pp. 257]

CorrespondenceMahler: 'Smtliche Werke', Bd. III[pp. 258]Burney's Correspondence [pp. 258]The Easter Sepulchre Drama [pp. 259]Alkan Society [pp. 259]The Rsler-Rosetti Problem[pp. 259]

Books Received [pp. 260-261]Music Received [pp. 261-268]Back Matter