HP ENVY 4 Sleekbook HP ENVY 4 Ultrabook HP ENVY TouchSmart ...

Envy, comparison costs, and the economic theory of the firm · of the market within the firm, the...

Transcript of Envy, comparison costs, and the economic theory of the firm · of the market within the firm, the...

Strategic Management JournalStrat. Mgmt. J. (2008)

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/smj.718

Received 22 March 2006; Final revision received 16 May 2008

ENVY, COMPARISON COSTS, AND THE ECONOMICTHEORY OF THE FIRM

JACK A. NICKERSON* and TODD R. ZENGEROlin Business School, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.

An economic theory of the firm must explain both when firms supplant markets and when marketssupplant firms. While theories of when markets fail are well developed, the extant literatureprovides a less than adequate explanation of why and when hierarchies fail and of actionsmanagers take to mitigate such failure. In this article, we seek to develop a more complete theoryof the firm by theorizing about the causes and consequences of organizational failure. Our theoryfocuses on the concept of social comparison costs that arise through social comparison processesand envy. While transaction costs in the market provide an impetus to move activities inside theboundaries of the firm, we argue that envy and resulting social comparison costs motivate movingactivities outside the boundary of the firm. More specifically, our theory provides an explanationfor ‘managerial’ diseconomies of both scale and scope—arguments that are independent fromtraditional measurement, rent seeking, and competency arguments—that provides new insightsinto the theory of the firm. In our theory, hierarchies fail as they expand in scale because socialcomparison costs imposed on firms escalate and hinder the capacity of managers to optimallystructure incentives and production. Further, hierarchy fails as a firm expands in scope for thesimple reason that the costs of differentially structuring compensation within the firm to matchthe increasing diversity of activities also rises with increasing scope. In addition, we explorehow social comparison costs influence the design of the firm through selection of productiontechnologies and compensation structures within the firm. Copyright 2008 John Wiley &Sons, Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

The theory of the firm has primarily focused onthe question of firm boundaries, articulating whenfirms supplant markets and when markets sup-plant firms. Coase (1937) originally articulated thelogic that boundary choices depend on a com-parative assessment of the costs of internally and

Keywords: theory of the firm; envy; comparison costs;diseconomies of scale and scope; firm boundaries∗ Correspondence to: Jack A. Nickerson, Olin Business School,Washington University, Campus Box 1133, One BrookingsDrive, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899, U.S.A.E-mail: [email protected]

externally managing activities. When market gov-ernance is costly or markets fail, integration islikely; when internal governance is costly or orga-nizations fail, market governance is likely. Cur-rent theory provides well-developed explanationsfor the failure of markets. Markets commonly failwhen exchange demands highly specialized assets,involves measurement difficulty, or requires thetransfer of knowledge (Williamson, 1975; Klein,Crawford, and Alchian, 1978; Barzel, 1982). How-ever, as both Coase (1937) and Williamson (1985)note, a theory of market failure alone is not a the-ory of the firm, because such theory fails to resolvea basic puzzle: If firms are advantaged in manag-ing these complexities in exchange, ‘why is not all

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

production carried on by one big firm?’ (Coase,1937: 394). What precludes the firm from selec-tively using the control features of hierarchy andotherwise replicating market incentives within itsboundaries? If firms can replicate market incen-tives and utilize authority to control exchange onlywhen needed, the firm should face no boundarylimits. Indeed, absent impediments to replicatingmarket incentives within the firm, the boundariesof the firm become rather irrelevant and managersenjoy enormous flexibility in the design and struc-ture of organizations.

Existing theory provides little in the way ofexplanation for the limits of the firm or the causesof organizational failure. The prevalent view inearly writings on industrial organization was thatlimits to firm size were due to ‘diminishing returnsto management’ (Sraffa, 1926; Kaldor, 1934).Implicitly, Coase (1937) adopted a similar argu-ment, assuming that at some point, integratingadditional transactions becomes more costly thanmanaging them externally. However, Coase pro-vided no clear explanation as to the origin of thesecosts or why so-called management costs shouldrise with firm scale and scope. Indeed, Coase hascommented that the question of why the costsof internal organization increase with firm scaleand scope remains unanswered (Coase, 1988). Ourgoal is to develop a theory of organizational fail-ure, more precisely a theory of organizational dis-economies of scale and scope that is rooted inprocesses of social comparison as discussed inthe sociology and social psychology literatures.These processes of social comparison give rise towhat we label ‘social comparison costs’ (Zenger,1992; 1994). Our theory argues that while transac-tion costs in the market prompt access to author-ity through integration, social comparison costsprompt managers to limit the degree of integrationand otherwise take costly organizational actions torestrict and efficiently manage these social com-parison costs.

We are, of course, not the first to explore thequestion of organizational failure (see Hennart,1994). Some have argued measurement difficul-ties escalate with firm size and limit the capacityof large firms to offer the high-powered incen-tives prevalent in markets (Barzel, 1982; Holm-strom, 1989; Rasmusen and Zenger, 1990; Zenger,1992; Williamson, 1985). But, this argument alonedoes not explain why a large firm can’t replicatethe measurement precision of markets by creating

highly autonomous internal units and then structur-ing market-like incentives within its boundaries.Similarly, this argument does not explain why afirm cannot integrate an independent firm or activ-ity and craft incentives that fully replicate the mar-ket incentives that previously existed.

Influence activities within organizations, as dis-cussed by Milgrom and Roberts (1988; 1990a;1990b), provide a partial explanation. When anactivity is integrated within the boundaries of thefirm, it is placed in an arena in which incentivesnow exist for both those managing the integratedactivity and those positioned elsewhere in the firmto politically influence the distribution of rewardsallocated to those managing it. They argue thatsuch rent-seeking activity is wasteful and fullyabsent when the activity is autonomously con-trolled by the market. Absent integration, there issimply no one to politic and therefore no influ-ence activities. While these influence activitiesundoubtedly play an important role in shaping theboundaries of firms, they provide at best a par-tial explanation. The theory does not explain whythese organizational costs should increase withsize or scope. Thus, while Milgrom and Roberts(1988, 1990a, 1990b, 1992) explain why selec-tive intervention is costly within firms, they donot explain why the marginal transaction or activ-ity becomes increasingly costly to integrate, as thefirm increases in scale and scope. Since Milgromand Roberts’ (1988, 1990a, 1990b, 1992) argumentis invariant to size and scope, the theory fails toexplain the limits to firm size and scope.

In this study, we develop a theory of managerialdiseconomies of scale and scope, which are orga-nizational failures that constrain the boundaries ofthe firm. We begin by assuming that market fail-ures of the type commonly described in the trans-action cost economics literature provide the impe-tus to integrate activities within the boundariesof the firm. Cognizant of these transaction costsin the market that prompt the extension of firmboundaries, we develop a theory of countervail-ing social comparison costs that impel managersto restrict these boundaries or otherwise controlthese costs. Thus, while market failures create atype of centripetal force for moving activities outof the market and into a firm, our theory explainswhen and how organizational failures create a cen-trifugal force for moving activities out of the firmand into the market.

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

As a brief preview, our theory begins by examin-ing the behaviors of both individual employees andmanagers in response to the infusion of market-likeincentives within the firm. Consistent with a widerange of social science literature, we assert thatindividual employees invidiously compare theirrewards with others they deem to be within theirreferent group (for example, see Adams, 1963;Festinger, 1954). If perceived inequity arises, theresulting negative feeling—what we refer to asenvious emotion—drives individuals to expendeffort to ameliorate these perceptions of inequity.Such behaviors include reduced effort, influenceactivities, departure, noncooperativeness, or evenoutright sabotage. Such behaviors impose substan-tial costs on the firm—costs that we reference associal comparison costs.

Managers, of course, are not passive actors inresponding to these comparison costs. Managersanticipate social comparison costs or at least per-ceive them when they arise, and take active stepsto attenuate them. Management, we argue, hasthree structural levers at its disposal to attenu-ate social comparison costs: ‘compressing’ rewardsby decoupling pay and performance, shifting ‘pro-duction technology’ to reshape social comparisonand social referents, and redrawing the bound-aries of the firm. Our theory argues that each ofthese choices potentially imposes significant costson the firm. Therefore, the probability that man-agers will select any one of them depends onthe magnitude of social comparison costs associ-ated with each. As social comparison costs rise,managers are more likely to respond with damp-ened incentives, compromised production technol-ogy, or restricted boundaries to the firm. We arguethat the scale and scope of the firm are primarydrivers of these social comparison costs. Hence,as scale and scope increase, the need to attenuatesocial comparison costs through incentive dampen-ing, production efficiency compromises, or bound-ary restriction increases. The result is a theoryof organizational failure in which organizationalcosts rise with increasing scale and scope of thefirm. We believe our theory provides an expla-nation for managerial diseconomies of scale andscope—an argument that is independent from tra-ditional measurement, rent seeking, and compe-tency arguments—that contributes to determiningfirm boundaries.

In the pages that follow, we use a series ofillustrations to highlight the social comparison

costs that arise as managers attempt to selec-tively infuse market incentives within the firm.We then discuss the structure of these costs andidentify and describe three levers, or organiza-tional design choices, available to managementto attenuate them. We use two levels of analy-sis—employee decisions about how to attenuateenvious emotions and managerial policy decisionsabout the structure of the firm—to develop anargument for how social comparison generates dis-economies of scale and scope in firms. We thendiscuss the implications of our theory along witha few caveats and conclude.

Selective intervention and social comparisoncosts

Our theory is designed to complement, not replace,the logic of transaction cost economics. In trans-action cost economics, managers choose marketsover firms in order to access the superior incen-tives that markets provide (Williamson, 1991). Inother words, managers forego integration and thuslimit the size and scope of the firm in order toaccess the high-powered incentives of the market(Williamson, 1985). Consequently, as Williamsonargues, if managers could replicate the incentivesof the market within the firm, the firm would faceno limits to its scale and scope, and hence no limitsto its boundaries. If firms could truly complementthe virtues of internal organization with the incen-tives of the market, markets need never arise andthe boundaries of the firm face no limits. There-fore, to understand the limits to the scale and scopeof firms, it is useful to first explore why firms failas managers attempt to internally replicate marketincentives.

We are not the first to observe the difficultythat firms face in selectively replicating marketincentives for subunits or activities within the firm(Williamson, 1985; Zenger and Hesterly, 1997).Indeed, there is empirical literature that confirmsthe greater difficulty that large firms confrontin structuring market incentives within the firm(Garen, 1985; Zenger and Marshall, 2000). Fur-thermore, the literature is replete with examplesof failed attempts at such ‘selective intervention.’By examining a few notable illustrations of thesefailed efforts, we hope to highlight the genesis ofsocial comparison costs and provide a backdropfor our theory.

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

Illustration 1

Harvard’s efforts to manage internally their endow-ment portfolio provide a fascinating example ofsocial comparison costs. Until 2005, Harvard Man-agement Company was a wholly owned subsidiaryof Harvard University that managed Harvard’s$27 billion endowment portfolio. In an effort tomimic the rewards offered to fund managers ofprivately managed hedge funds, the multiple fundmanagers within the Harvard subsidiary receivedcompensation based purely on a formula thatlinked bonus compensation to their fund’s perfor-mance relative to a benchmark fund of comparablerisk and classification (see Hall and Lim, 2003).These internally managed funds quite consistentlyoutperformed the benchmark funds by a very widemargin, which resulted in extremely high com-pensation for these Harvard employees. In fiscalyear 2004, the top two fund managers received$25 million each. In fiscal year 2003, the topfund managers received $35 million each. In 2001and 2002 large sums were also paid out to fundmanagers due to exceptional relative performance,even though the funds themselves declined invalue. In 2004, opposition from students, alumni,and faculty to such pay reached a feverish pitch(Harvard Magazine, 2004). Key alumni calledfor a university-wide forum to review the matterand threatened to withhold donations. Larry Sum-mers, Harvard’s President, claimed that outsourc-ing the activity would lead to lower performanceand higher fees, while Ronald Daniel, the Uni-versity Treasurer, defended the practice by notingthat other universities which use ‘external invest-ment managers. . .do not face comparable scrutiny’(Harvard Magazine, 2004: 73). In early 2005, Har-vard Management Company significantly restrictedthe maximum levels of compensation within thesubsidiary. By March of 2005, many of the keyfund managers had departed, taking with themportions of Harvard’s endowment to manage exter-nally.

Illustration 2

Strauss’ (1955) describes a factory that manufac-tured wooden toys that sought to enhance theproductivity of a team of workers in the paintdepartment through a bonus pay system basedon team output. As a result of the market-likepay plan, productivity of this team increased

30 to 50 percent above what was traditionallyexpected. These employees consequently earneda significant premium above what other moreskilled workers earned in other parts of the plant.Because of this differential, ‘[m]anagement wasbesieged by demands that the inequity be takencare of’ (Strauss, 1955: 94). Ultimately, manage-ment returned the painting operation to its original(and less productive) pay structure, which quicklyled to the voluntary departure of workers on theteam, as well as the departure of their supervisor.

Illustration 3

In 1980 Tenneco Inc., acquired a relatively smallcompany, Houston Oil and Minerals Corpora-tion (HOMC) (see Williamson, 1985: 158; andMilgrom and Roberts, 1992: 194). To encouragethe retention of HOMC’s exploration talent, Ten-neco offered special salaries, bonuses, and ben-efits to HOMC employees—payments that werenot offered to others at Tenneco. ‘Tenneco alsoagreed to keep [HOMC] intact and operate itas an independent subsidiary rather than consol-idate the acquisition.... Despite initial enthusiasm,[HOMC’s] managers and its geologists, geophysi-cists, engineers, and landsmen left in droves duringthe ensuing year’ (Williamson, 1985: 158). Theimplementation of the customized compensationpackage had been delayed, because, as Tenneco’svice president for administration maintained, ‘Wehave to ensure internal equity and apply thesame standard of compensation to everyone. . .’(Williamson, 1985: 158).

Illustration 4

Recently, MBA students at a North American busi-ness school, which will remain anonymous, com-plained about the lack of access to the more ‘visi-ble and famous’ professors at the school. Seekingto satisfy student demand while recognizing thatthese same professors were in high demand forconsulting and speaking engagements, the deanproposed individually negotiating overload teach-ing payments to faculty. This approach wouldenable the payment of ‘market rates’ for internalteaching services. However, discussion with fac-ulty quickly led to concerns over fairness, whichcould be resolved only if there was a set rate forall faculty to do overload teaching. It is interestingto note that no such fairness concerns were voiced

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

about high speaking and consulting fees generatedfrom outside the university. Negotiation with indi-vidual faculty on overload remuneration did notproceed.

Illustration 5

At International Harvester in the 1960s, the unionrequested that management increase the speed ofparticular assembly lines where employees wererewarded in part based on output. Despite clearbenefits to the firm, management refused, con-cerned that higher pay for this group would pro-mote dissension elsewhere among those not ben-efiting from the line speed increase (reported inMcKersie, 1967: 222).

Illustration 6

In the early 1970s, Syntex and Varian Corporationestablished a joint venture to commercialize jointlydeveloped technology. The intent was to create anentrepreneurial unit free from the bureaucracy ofthe larger parent companies. Consistent with thedesire to create the feel of a truly new start-up, thehead of this new venture was given a compensationpackage characteristic of a small, entrepreneurialfirm. He was granted an equity stake and assigneda relatively small salary. As soon as the detailsof this package were revealed to senior executivesat Syntex, a major internal uproar ensued. Longbefore any value from the joint venture could berealized, the compensation package of the headof the joint venture was realigned so as to beconsistent with others at a similar level withinSyntex (former vice president of Human Resourcesto second author, personal communication).

Overview

There are several common themes revealed inthese illustrations. In each, managers within theorganization sought to develop a high-powered,market-like incentive mechanism, custom-tailoredto a specific group or activity. In each case wherethe incentive plan was in place long enough tomeasure performance, the performance results forthose engaged in the activity were quite positive.However, due to this success or anticipated suc-cess, the plans produced wide variance in compen-sation and, in particular, some very high compen-sation levels that others in the organization per-ceived as inequitable. The costs imposed by the

reactions (or anticipated reactions) of these otheremployees prompted the plans’ cessations. Notethat in each case management was forced to makea trade-off between the incentive benefits of thoseaffected by the plan, in terms of higher effort or theattraction of superior talent, and comparison costsimposed by those not attached to the plan. In eachcase the social comparison costs were determinedto outweigh the incentive benefits.

These illustrations suggest that organizationsmay fail relative to markets because social compar-ison costs limit the flexibility of managers in offer-ing the ‘optimal’ market-like incentives for specificactivities within the firm. Below, we illuminatemore completely the mechanisms that underlie thisargument. Moreover, we argue that as a firm’sscale and activity scope increase, comparison costsalso increase and with them the manager’s inflex-ibility in tailoring incentives for different inter-nal activities. These rising costs and inflexibilityamount to organizational failures that constrain theboundaries of the firm.

Social comparison and human behavior

Our theory begins with the assumption that indi-viduals engage in a process of socially comparingtheir rewards to those received by salient referents.Thus, decisions about how rewards are allocateddefine in part the nature of these social compar-isons. Research on social comparison processesand their effect on individuals are legion across thesocial sciences (Homans, 1961; Festinger, 1954;Adams, 1963; Martin, 1981). Many theories indi-cate that people engage in comparison activities,focusing especially on relative income and thebasis by which relative income is determined.Moreover, these comparisons tend to be invidi-ous in the sense that individuals identify salientreferents as those who are economically betteroff. These theories assert that people care aboutinequity; they react negatively to outcomes theydeem unfair; and they exert efforts to reduce neg-ative feelings proportionate with the inequity theyperceive (Adams, 1963). This propensity to com-pare income to salient referents and the willingnessto expend effort to reduce perceived inequity in rel-ative income, we assert, constitutes a fundamentalbehavioral assumption about human nature uponwhich our theory rests.

Modern research on social comparison processesbegins with Festinger (1954), who assumed that

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

humans have an innate propensity to self-evaluate‘based on comparison with other persons’ (1954:138). Homans’s (1961) study constructed similararguments, emphasizing that individuals particu-larly compare income.1 Equity theory as developedby Adams (1963) posits that ‘[i]nequity exists for[an individual] whenever his perceived job inputsand/or outcomes [typically measured by actualor expected income] stand psychologically in anobverse relation to what he perceives are the inputsand/or outcomes of [others]’ (Adams, 1963: 424).Relative deprivation theory similarly concludesthat feelings of deprivation arise from compar-isons of rewards to some referent (Martin, 1981).It is important to note that perceptions of inequityare not symmetric. That is, individuals commonlyhave inflated perceptions of personal contribu-tion or performance (Meyer, 1975; Zenger, 1994).The problem of establishing equity perceptions isfurther exacerbated by individuals’ propensity tocompare pay only to those perceived as compa-rable in performance, but earning more (Martin,1981). This combination of upwardly biased self-assessment and a propensity to compare incometo those earning more nearly always ensures atleast some level of inequity perception. Thus, vary-ing perspectives on social comparison and inequityperceptions are consistent with the notion that indi-viduals are envious of salient referents perceivedto receive superior income relative to their contri-butions.2

1 Homans’s classic on social behavior (1961), which builds onBlau’s (1955) social exchange theory, identifies an equivalentpropensity. Homans claims that individuals engage in exchanges,whether they are economic or social, because they receive somebenefit in excess of their costs (Homans, 1961: 72). Further,individuals ‘perceive and appraise their rewards, costs, andinvestments in relations to the rewards, costs, and investmentsof other men’ (Homans, 1961: 76). Homans’s key proposition inthis regard is that ‘the more to a man’s disadvantage the rule ofdistributive justice fails of realization, the more likely he is todisplay the emotional behavior we call anger’ (Homans, 1961:75). This proposition equates to individuals caring not only aboutthe absolute level of their income but also about relative income.Moreover, Homans acknowledges that such anger translates intoaction because individuals ‘learn to do something about it’(Homans, 1961: 77).2 At least since Aristotle, philosophers have recognized envy andjealousy as fundamental propensities of human nature. Envy isthe emotion that arises when one desires something currentlypossessed by another (Salovey, 1991). Envy is one of the sevendeadly sins (Silver and Sabini, 1978) and perhaps the most per-vasive but under-acknowledged one (Epstein, 2003). Arguably,it is envy and jealousy that generate feelings from social com-parison that give rise to actions to reduce such feelings becausepeople systematically care more about others ahead of them com-pared to those behind them. For instance, while Festinger (1954)

Social comparisons that lead to inequity percep-tions in individuals create a willingness to expendeffort to attenuate these feelings of inequity. Suchefforts increase the greater is the perceivedinequity. For instance, Adams (1963: 427) arguedthat ‘[t]he presence of inequity in [an individ-ual] creates tension in him . . .proportional tothe magnitude of inequity present’. The pres-ence of inequity ‘will drive him to reduce it.’ Aswith equity theory, feelings of relative deprivationprompt behavioral responses to alleviate or avoidsuch feelings (Martin, 1981). Generally speak-ing, the literature argues that those who perceiveinequity relative to their social referents expendeffort to eliminate this tension by restoring equity(see Walster, Berscheid, and Walster, 1973; Adamsand Freedman, 1976; Ma and Nickerson, 2007; forempirical reviews see Greenberg, 1982; Suls andWills, 1991).

An important issue underlying this research isidentifying which referents are salient. In otherwords, with whom do individuals socially comparethemselves? The general conclusion in the litera-ture is that spatial proximity, degree of interaction,and availability of information are primary deter-minants of the choice of salient referents (e.g., Fes-tinger, 1954; Kulik and Ambrose, 1992; Williams,1975). Spatial proximity means not only propin-quity, but also a variety of other demographicmeasures of social distance such as age, tenure,education, gender, and the like. As with spatialproximity, the degree of interaction and the avail-ability of information may be endogenous to firmboundaries and other organizational and produc-tion technology choices. These conclusions arereminiscent of Aristotle’s observation (Rhetoric,1388, quoted in Goel and Thakor, 2003): ‘We envythose who are near us in time, place, age, or rep-utation.’ We return to these issues below.

The literature suggests that individuals pur-sue several different behaviors or strategies toreduce envious emotions that accompany per-ceived inequity. First, individuals alter their ownbehavior. In particular, they reduce effort, bringingcontributions more in line with rewards (Adams,

did not delve into the emotional underpinnings of social compar-ison theory, Salovey (1991) argues that envy and jealousy arethe specific emotions that accompany such appraisals. Indeed,invidious comparison, envy, jealousy, or some combination ismentioned as the implicit or explicit motivation for behavior inall three of the psychological perspectives mentioned above.

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

1963).3 Second, individuals seek to alter others’outcomes and rewards in several ways: directlysabotaging others’ efforts, behaving noncoopera-tively with them in collaborative settings, or sim-ply lobbying those managers who assign theircompensation (Cropanzano, Goldman, and Folger,2003; Pruitt and Kimmel, 1977; Smith and Walker,2000). Finally, individuals may simply departfrom the referent group that prompts envy, forinstance, by exiting the job, firm, or industry (Fes-tinger, 1954; Mui, 1995; Salovey, 1991; Sheppard,Lewicki, and Minton, 1992; White and Mullen,1989). These behavioral strategies to reduce envi-ous emotion impose costs on the firm, which weterm social comparison costs (Zenger, 1992; 1994).

Evidence of these social comparison costs isabundant in our motivating examples. For instance,perceptions of the inequitable compensation led tointense lobbying activities to reallocate rewardsat Harvard, at the wooden toy factory, at theNorth American business school, and at Syntex.Tenneco’s insistence on ‘internal equity’ in com-pensation also implied a concern for these costs.Similarly, management at International Harvesterwas concerned with these social comparison costsin contemplating selectively rewarding a subset ofemployees based on output. In all of our illus-trations social comparison costs overwhelmed anygains that accrued or would have accrued fromoffering high power incentives to a select groupwithin the firm.

In summary then, humans have the propensityto engage in social comparisons. These compar-isons, in the presence of differences in relativeincome among salient referents, trigger percep-tions of inequity and envious emotion that indi-viduals attempt to reduce. An overarching themein the literature is that the greater the disparitiesamong salient referents, the larger is the costlyeffort individuals are willing to expend to reducetheir perceptions of inequity. The specific actionsundertaken by individuals to reduce their enviousemotion impose social comparison costs on firms.Thus, the organizing challenge of the manager is to

3 In addition to increasing or reducing effort to bring contri-butions more in line with rewards, workers might also (over)invest in capabilities through training or education based on theexpectation of future rewards. To the extent that workers chooseincreasing effort and investing in capabilities to reduce envi-ous emotions, these behavioral responses can benefit the firm.We set aside these behaviors that might benefit the firm whiledeveloping our theory and return to them in the discussion.

design an organization that attenuates these socialcomparison costs while simultaneously providingeffective incentives and efficient production tech-nology.

Economizing on social comparison costs

While transactions cost economics contends thatthe manager’s job is to economize on transactioncosts, our theory suggests that the manager’s jobis to (also) economize on social comparison costs.We maintain that managers have at their disposalthree structural or organizational levers with whichto attenuate social comparison costs: wage com-pression, the choice of production technology, andthe choice of firm boundaries. All contribute toexplaining organizational diseconomies of scale.Below, we not only highlight how these leverseconomize on social comparison costs, but alsoexamine how each choice imposes its own costson the organization. After discussing these levers,we consider their relationship to managerial disec-onomies of scale and scope.

Wage compression

Scholars from a range of disciplines suggest thatweakening the link between pay and performanceis a common response to social comparison pro-cesses (Akerlof and Yellen, 1990; Frank, 1985;Konrad and Pfeffer, 1990; Zenger, 1992). By tak-ing steps to reduce differences in income amongworkers, managers reduce the impetus for workersto envy each other’s income. Indeed, by adopt-ing uniform compensation, managers essentiallyavoid issues of distributive justice.4 When all pay

4 Even when compensation is uniform and distributive concernsare rendered rather moot, procedural justice issues may still arise.Distributive justice focuses on perceived fairness of the distri-bution of rewards (Homans, 1961) whereas procedural justicefocuses on perceived fairness of the process by which decisionsare reached (Greenberg, 1990). We do not incorporate procedu-ral justice concerns into our argument for three reasons. First,empirical research indicates that distributive justice contributesto variance of satisfaction with pay more than twice that of pro-cedural justice (Tyler, Rasinski, and McGraw, 1985; Folger andKonovsky, 1989), which suggests that distributive justice maybe far more important than procedural justice. Second, Long,Bendersky, and Morrill (2007) find that when tasks are separateand pay contingent, workers principally care about distribution ofrewards—a perspective consistent with our view. They also findthat when tasks are interdependent and wages are not contingent(i.e., wages are compressed), workers may then care more aboutprocedural justice. Their finding suggests that distributive justiceis a more important driver of structural responses by managers

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

is equal, perceptions of inequity must stem fromdiffering perceptions of performance rather thanpay. A small but growing economics literaturehas incorporated envy and social comparison intoformal models.5 These economists acknowledgethat workers care about relative income, whichcreates social forces that affect the wage pro-files within and between firms. In an early com-ment, Hicks (1955: 390) states that ‘[e]conomicforces do affect wages, but only when they arestrong enough to overcome these social forces.’Economists acknowledge that disparities in com-pensation can ‘induce discontent among employ-ees, . . . followed by uncooperative and unaccom-modating behavior’ (Pencavel, 1977: 239). Thus,economists theoretically and empirically note thatmanagers can and do attenuate social comparisoncosts by flattening the wage structure comparedto the marginal product schedule. In doing so,the firm elevates pay beyond the marginal productfor some and constrains pay below the marginalproduct for others, which may precipitate depar-ture—a phenomenon called wage compression.These economic arguments clearly resonate withthose of equity theory, relative deprivation, andsocial exchange theory discussed above.

and that procedural justice may take on importance only afterwages are compressed. Third, scholars have found the centralissue of procedural justice revolves around worker commitmentto the organization, which may be little affected by productiontechnology and organizational boundaries, which are importantlevers in our theory.5 Although still rare, economists with increasing frequency haveincorporated the concept of envy into a variety of analysestypically modeling preferences as interdependent. For instance,Foley (1967) introduced the notion of social comparison anddefined envy-free equilibria in which everyone likes his ownallocation goods at least as well as that of anyone else. Suchenvy-free equilibria are equitable and have been generalizedby Varian (1974) in welfare economics and used to investigatesuch topics as tax policies to correct distortions created by envy(Banerjee, 1990) and redistribution programs (Brennan, 1971).Others have shown that relative status may lead to risk-taking(Brenner, 1987) and may cause people to abstain from becomingsuperior to others to avoid provoking envy (Elster, 1991). Mui(1995) directly implements equity theory in a utility function andanalyzes how varying legal institutions’ and agents’ propensitiesfor envy jointly determine whether agents engage in innova-tion, retaliation, sabotage, or sharing behavior. Other theoreticaleconomics literature that is focused on the applications of envy-based preferences in certain economic situations includes Boltonand Ockenfels (2000), Charness and Rabin (2002) and Fehr andSchmidt (1999). Experimental economic evidence on envy hasbeen reported by Martin (1981), Cason and Mui (2002), andZizzo and Oswald (2001). Additional empirical evidence canbe found in Frank (1985), Pfeffer and Davis-Blake (1992) andPfeffer and Langton (1993).

It is useful to distinguish between two types ofwage compression. Horizontal wage compressionrefers to the adoption of rather flattened or moreuniform compensation for individuals in equiva-lent or identical jobs. Thus, as the costs imposedon firms by social comparison processes increase,firms adopt more horizontally compressed or moreuniform income for each position (e.g., Hicks,1955; Addison and Burton, 1981; Hamermesh,1975; Dunlop, 1947; Pencavel, 1977). Indeed, itis well documented in labor economics that work-ers undertaking the same job or occupying posi-tions within the same grade typically have minordifferences in relative income even though theirmarginal products may vary greatly. This unifor-mity of income—income that is invariant withperformance—is a decision made by management.

A second type of wage compression—verticalwage compression—arises among workers hold-ing different positions, or performing completelydifferent jobs. Vertical wage compression involvesreducing the variation in income across differingpositions or jobs, despite potentially widely vary-ing marginal products associated with these jobsand positions. Addressing the vertical wage com-pression phenomenon, Frank (1984a; 1984b; 1985)offered a formal theory how invidious compar-isons and variation in utility for status lead tovertical wage compression in firms. Akerlof andYellen (1990) in their fair wage hypothesis arguethat vertical wage compression is a best responseby management to counter reduced effort, whichoccurs as a response to envy among individu-als with different skills. These and other scholarsargue that preferences for perceived inequity maycause managers to vertically compress wages bynarrowing income dispersion across levels and jobs(e.g., Frank, 1984a; 1984b; Akerlof and Yellen,1990; Hicks, 1955; Addison and Burton, 1981;Hamermesh, 1975; Dunlop, 1947; Pencavel, 1977;Zenger, 1992).

Our prediction is that as social comparison costsincrease, managers are more likely to engage inwage compression both vertically and horizontally.Such wage compression offers an economic leverto ameliorate social comparison costs by reducingthe stimulus of envy. Its application, however, nec-essarily implies efficiency losses as weak incen-tives discourage high effort and trigger a patternof adverse selection among workers in which thehighly productive but underpaid depart, while theless productive but overpaid remain.

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

Technology choice

A second economic lever at management’s dis-posal in response to social comparison costs relatesto shaping a firm’s production technology, broadlydefined. From a classical microeconomic perspec-tive, for any given desired output there is an opti-mal production technology that defines the con-figuration of assets and the structure of individualand collective tasks and activities within the firm.In addition to this ‘technical’ efficiency, the choiceof production technology also defines the degree towhich output is team produced, the spatial prox-imity of workers, and the degree to which workersinteract. Thus, managers shape both productioncosts and social architecture when choosing a pro-duction technology.

The social architecture defined by a produc-tion technology is important because it shapessocial comparison processes, which can imposecosts on the organization in two ways. First, socialarchitecture affects the cost of accessing informa-tion about peers’ performance and productivity,which molds processes of social comparison. Forinstance, workers located in close proximity andperforming similar tasks are likely to identify eachother as salient referents and compare income,which, if different, can lead to social comparisoncosts. By increasing the physical distance amongworkers, management can restrict the scope ofinteraction and information sharing, thereby reduc-ing the salience of these workers as referents.6

Thus, management can reduce social comparisoncosts by increasing the physical and informationaldistance between jobs, which, however, departsfrom the technically efficient production technol-ogy.

Second, the choice of production technology,specifically the extent of team production, shapessocial comparison costs by defining the precisionwith which individual performance is measured. Inthe absence of team production, workers and man-agers can clearly observe and verify relative indi-vidual contributions (Alchian and Demsetz, 1972).While variance in worker income may stimulate

6 Managers can and often do limit the disclosure of employeecompensation (Lawler, 1990). Many companies require employ-ees to sign documents in which they agree not to discussinformation about their personal compensation. However, oftenin such organizations and in many others, there is an infor-mal agreement among employees to anonymously share theirsalary information, which is then aggregated and shared as adistribution.

envy, the absence of team production limits theefficacy of behavioral strategies that impose com-parison costs on the firm. For instance, in theabsence of team production, shirking imposes largecosts on the worker in terms of lost productivityand income and imposes rather modest costs inlost productivity for the firm. The verifiability ofindividual performance causes influence activitiesthat appeal to management to raise pay or lowerothers’ pay to be credibly met with the responsethat the worker, not management, is responsi-ble for earning less. Noncooperative behavior andsabotage are less feasible strategies because theylead to a reduction in the worker’s own produc-tivity and income. Furthermore, independent jobsreduce the opportunities for such behavior. By con-trast, the envy promoted by pay variance withindependent jobs may trigger behavioral strategiesthat positively affect worker effort and benefit thefirm, since additional effort translates directly intohigher income. Thus, social comparison processeswhen jobs are independent may lead to social com-parison benefits instead of costs.

By contrast, social comparison costs are likelyquite high when managers in a team productionenvironment attempt to link income to individ-ual performance. As the scope of team produc-tion increases, accurately observing and agree-ing on relative contribution becomes more diffi-cult for workers and managers alike. In a teamproduction setting, individual contributions are ofnecessity subjectively determined. Consequently,if managers assign pay based on these subjec-tive evaluations, this engenders influence activi-ties because managerial subjectivity can be blamedfor differences in pay. Additionally, individualswithout access to verifiable information rather eas-ily develop inflated perceptions of their marginalcontributions (Meyer, 1975; Zenger 1994), whichmay amplify willingness to engage in influenceactivities. Moreover, team production makes feasi-ble other behavioral strategies like noncooperativebehavior and sabotage as well as shirking that arenot effective in the absence of team production.Coincidentally, because of measurement difficul-ties, team production also reduces the effectivenessof behavioral strategies like increasing effort as ameans of raising income.

The underlying logic here is that in team pro-duction settings the social comparison costs thataccompany efforts to link pay and individualperformance typically overwhelm the benefits.

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

Consequently, managers increasingly compresswages to reduce envy as the degree of team pro-duction rises. Thus, Leventhal (1976) and Deutsch(1985) find that individuals prefer equal rewardsrather than performance-based rewards when theyanticipate collaborating on tasks. Similarly, Frank(1985) and Konrad and Pfeffer (1990) argue thatproduction technologies that encourage collabora-tion hinder pay based on individual contributions.

Choosing an inefficient production technologyfor the purpose of reducing social comparisoncosts obviously imposes its own set of costs. Forinstance, in our illustration of International Har-vester and the toy factory, management purpose-fully chose a technically inefficient assembly linespeed in order to avoid income dispersion thatwould generate social comparison costs. Attenuat-ing envy, while attempting to reward performance,often calls for a departure from the technologicallyefficient choice of production technology; it oftendemands spatially separating workers and limit-ing information flows to reduce social comparison.Thus, to reduce social comparison costs to a levelsufficient to allow aggressive pay for performance,managers may need to alter production technologyto reduce collaboration, increase physical distanceamong employees, or actively contain informationabout productivity and income. Thus, our predic-tion is that as social comparison costs rise, man-agers are more likely to compromise the efficiencyof production technology to mitigate these costs.

Constraining firm boundaries

The final and most dramatic structural means toconstrain social comparison costs is to limit theboundary of the firm. While social comparisonoccurs both within and across firms, the scopeof such comparison and the corresponding costsimposed play out very differently within firms thanacross firms. These differences allow managementto use the boundary of the firm as a means of influ-encing social comparison costs. The shift in socialcomparison costs at the firm’s boundary occurs fortwo reasons. Either reason is theoretically suffi-cient to generate our boundary prediction. First,within the boundaries of the firm, the presenceof the central manager who assigns compensationchanges the cost-benefit analysis that individualsface in determining their various individual behav-ioral strategies for reducing feelings of envy. We

argue that the behavioral responses to social com-parisons that occur within a firm are more costlythan the behavioral responses to social compar-isons that occur across firm boundaries. Second,the firm’s boundary may define an individual’ssalient reference group, which implies that alteringfirm boundaries alters the scope of salient refer-ents, and thus the scope of social comparison andits accompanying costs. We describe both mecha-nisms below.

Our first contention is that behavior stemmingfrom invidious comparison manifests differentlywithin the firm than across a market interface.Within the firm, the presence of a central man-ager shifts the costs and benefits of various behav-iors for reducing envious feelings. Consequently,the comparison costs imposed by these behaviorsaccrue differently within firms than across mar-kets. When comparison occurs within the firm, thecosts of both reduced effort and intense lobby-ing to restrict others’ pay are felt very directlyby the firm. By contrast, when a market inter-face separates focal individuals from those withwhom they compare themselves, the comparisoncosts that these focal individuals can impose areminimal. Across this market interface, there is nocentral authority who commonly assigns rewards.Consequently, there is very little that those whoperceive inequity across this market interface cando in response. Certainly, the external manager isunlikely to entertain pleas for cross boundary payequity from those employed with an outside firm.

To further illuminate this argument, consider twoactors, Gen and Will. Assume they are engagedin similar tasks, that Will views Gen as a salientreferent, and that Gen receives a higher income,which is known to Will. Because relative incomeis transparent to both parties, Will envies Genand is motivated to take action to reduce thisperceived inequity. The critical question is howWill’s actions to reduce feelings of envy differwhen Will and Gen are in the same versus differentfirms.

When Gen and Will are employed by the samefirm, Will can engage in influence activities thataffect Gen’s income or behavior. Will can lobbythe central manager to reduce Gen’s pay or tochange the nature of her job and thereby indi-rectly reduce her pay. Moreover, he can affect herbehavior by engaging in subtle and perhaps not-so-subtle forms of retribution and sabotage. Withinthe firm, Will is likely to have close access to

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

Gen’s work location and possess information use-ful to Gen, which could allow him to interfere withGen’s tasks. Such efforts in the anthropology lit-erature (e.g., Knauft 1991) are sometimes referredto as leveling and are exemplified in all of ourillustrations. While policies against retribution orsabotage may limit such behavior, the monitoringrequired to reduce these behaviors or to monitoreffort are clearly costly themselves.

In the case that Gen and Will are employed bydifferent firms, Will can take actions to affect hisown behavior such as working harder or invest-ing in his ability if it would increase income,engaging in influence activities to increase his ownincome, or reducing his effort. Alternatively, Willcan depart from the referent group. Will has lit-tle opportunity to affect Gen’s behavior or moreimportantly Gen’s income because, as Milgromand Roberts (1988, 1990a) argue, influence activi-ties are not effective across firms. Will might con-sider noncooperation and sabotage outside of thefirm; but, engaging in these activities may lead tointervention by civil authorities or social approba-tion.7

While the costs and benefits of these alternativeresponses depend on particular circumstances orcontext, it is nonetheless clear that the costs andbenefits of the alternative actions Will can taketo reduce feelings of envy shift when salient ref-erents are within the firm’s boundaries rather thanacross a market interface. The primary effect of theboundary of the firm in this context is to definethe ways in which Will can affect Gen’s behav-ior and rewards. This effect may also come in amore indirect manner. Gen, knowing that Will cansuccessfully alter her output and pay even if sheworks hard, may simply shirk in anticipation ofsuch behavioral responses by Will. Thus, enviedworkers may find it in their best interest to share

7 Other arrangements, of course, could exist. For instance, con-sider the case where Gen is a well-paid contractor working for agovernment agency for which Will is an employee. If Gen andWill are colocated and he views her as a salient referent, thenWill may envy Gen because of income differences. The numberand type of behavioral strategies available to him to reduce hisenvious emotions expands because of colocation (i.e., sabotageis now made feasible). Even so, not all behavioral strategies areavailable to him at low cost. For instance, political influenceactivities are unlikely to be effective because Gen belongs to adifferent organization. Influencing his manager to affect Gen’sincome likely would require revisiting the contract between twoorganizations, which, while not fully explored here, is likely tobe far more costly to change than the income of coworkers.

output or shirk to attenuate envy, which is a well-known and common response (Foster, 1972; Elster,1991; Mui, 1995). Such behavior introduces effi-ciency loss because it affects the envied worker’sincentive for high effort.

The boundaries of the firm not only influencethe costs imposed when rewards are compared, butthese boundaries also define patterns of compari-son. By defining these comparison patterns, firmboundaries further shape the magnitude of socialcomparison costs. Individuals within a firm seldomview those outside the firm as salient referents andvice versa. Individuals outside the firm are unlikelyto impose comparison costs on the focal firm, inpart because those inside the firm are less likely tocompare compensation with those outside. A vari-ety of arguments may explain the greater intensityof internal comparison. Closer physical proxim-ity or more intense social interaction within thefirm provides a partial explanation, though manywho are not employees of the firm may still haveclose physical proximity and extensive social inter-action with those within the firm. Organizationscholars argue that firm boundaries shape individ-uals’ sense of identity (e.g., Kogut and Zander,1992). Because individuals ‘identify’ with theiremployer, they compare pay to those within theorganization. The hierarchical structure in whichpay levels are essentially ratified or endorsed sup-ports this identification with the firm. The hier-archical structure used to allocate rewards alsocreates a de facto comparison process across gapsin the organization, either geographic or structural,which would otherwise prevent direct comparisonamong employees. While distance or the absenceof social contact may preclude direct comparisonsamong employees, managers compare the compen-sation of their subordinates with the compensationof other managers’ subordinates. Equity concernsand the capacity of managers to socially com-pare promote implicit comparisons among all thosewithin the borders of the organization. As a conse-quence, there are strong pressures to standardizepay policies even across geographically distinctorganizational units (Beer et al., 1984). Thus, ourprediction is that as the social comparison costsassociated with maintaining high powered incen-tives within an activity rise, managers are increas-ingly likely to outsource that activity.

In sum, our arguments suggest that managersface a fundamental trade-off between enduring

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

the comparison costs that accompany high pow-ered rewards, and enduring the productivity lossesthat accompany compressed compensation struc-tures, suboptimal production or task structures,and compromised boundary decisions. Managersmust balance the social comparison costs that arisefrom envy with the costs imposed by horizontallyand vertically compressing wages, adopting inef-ficient production technology, and reconfiguringorganizational boundaries. We contend that man-agement’s best response to expected social com-parison costs is often to use the structural leversat its disposal to reduce the stimuli of envy, bynarrowing the set of salient referents, or shiftingthe behavioral strategies individuals’ employ intheir effort to reduce envious emotions. Figure 1describes the basic relationships within our the-ory. Management selects the firm’s productiontechnology and social architecture, its compensa-tion and incentive structure, and its boundaries.These choices not only create an incentive struc-ture and production technology that employeesoperate within for producing output, but also cre-ate a particular pattern of social comparison withinand without the firm. Individuals respond to thispattern of social comparison and impose socialcomparison costs. Management expecting thesesocial comparison costs or updating its selectionchooses production technology, firm boundaries,and incentives structures in a way that balancesthe costs imposed by compromising choices oforganizational design and boundaries with socialcomparison costs.

Comparison costs and organizationaldiseconomies of scale and scope

Our arguments, thus far, highlight the role thatthe choice of incentives, production technology,and boundary decisions play in shaping com-parison costs. Our theory suggests that for anygiven activity a manager examines the comparativegovernance costs, both transaction and compari-son costs, of several alternatives: (1) governancethrough the market with high powered incen-tives, (2) governance within the firm with highpowered incentives, though perhaps with a pro-duction technology that reduces social compari-son, and (3) governance within the firm, but withrather weak, compressed incentives. Nothing tothis point, however, highlights how the selectionamong these choices is influenced by the scale orscope of the existing firm. Yet, empirically thereis evidence that scale and scope do matter inselecting among these alternatives. For instance,empirically, large firms are more inclined to com-press wages than small firms (Garen, 1985; Zenger,1994; Rasmusen and Zenger, 1990). We arguebelow that as scale or scope increase, social com-parison costs rise and consequently firms are morelikely to respond with wage compression, produc-tion technology compromise, or a limit to the scopeof the firm. Thus, decisions about how to governthe marginal activity depend on the scale and scopeof existing activities. To advance this argument,we examine a simple organization that can varyalong two dimensions: the scope of activities that

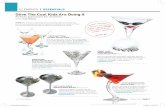

Management actions• compress wages• craft social architecture• select firm boundaries

Individual actions• influence activities• effort• turnover• cooperation

Socialcomparison costs

imposed byindividual behavior

Costs imposed by‘suboptimal’

organization design

Scope and patternof social comparison

Figure 1. Balancing social comparison costs and suboptimal organizational design

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

it performs and the scale of (i.e., the number of)participants within these activities.

Activity scale

We begin by discussing how the scale of an activ-ity within the firm shapes the comparison costs thataccompany efforts to link individual pay and indi-vidual performance within that activity. Of course,the sensitivity of comparison costs to activity scaledepends in part on the nature of the productiontechnology. When jobs are completely separateand independent, comparison costs in linking payto individual performance are quite limited andthus increasing the scale of the workforce intro-duces no real scale diseconomy. Individual perfor-mance is completely observable to all and employ-ees through their behavioral strategies can imposerather few costs on the firm. At the same time,when managers simply forego efforts to link indi-vidual performance and pay, due to high compari-son costs, and instead adopt horizontally and fullycompressed (flat) wages in response to high levelsof team production, then again there is no real scalediseconomy present. While there is a clear degra-dation in employee effort, horizontally flat wagesare fully scalable within an activity, that is, com-parison costs per worker do not rise when wagesshow no dispersion. However, our interest is inshowing that when attempting to link pay to indi-vidual performance within an intermediate level ofteam production, activity scale increases pressuresto compress wages, adopt a less efficient produc-tion technology, or even restrict the scale of anactivity.

To illustrate, consider a firm that performs a sin-gle activity staffed by multiple employees engagedin collaborative production. Assume that the firmdraws workers from a labor market pool in whichthe workers are heterogeneous in their ability tocontribute. As a starting point for our logic, assumethat the workers are paid what the firm estimates tobe each worker’s marginal product of labor. How-ever, because output is collaboratively producedand inputs are imprecisely measured, the assign-ment of individual contributions is both somewhatarbitrary and imprecise, which provides no veri-fiable information to counter inflated perceptionsof their marginal contribution. Also assume thateach worker considers all other workers within

the activity (or in this case, the firm) as socialreferents.8

Envy arises when differences in income emerge,especially among workers engaged in an activityinvolving team production. In our simple, singleactivity firm, differences in compensation arisebecause of differences in the manager’s assessmentof each worker’s marginal product—assessmentsinfluenced both by ability differences and by mea-surement error. A difference in pay between twoworkers gives rise to perceived inequity and envywithin the lower paid worker. If we assume thatfeelings of envy, and hence the effort the worker iswilling to expend to reduce these feelings increase,the greater is the pay differential between the twoworkers, then, at an aggregate level, perceptions ofinequity increase as the dispersion of pay increasesamong workers engaged in identical activities.

We contend that dispersion (the differencebetween the maximum and all others) in themarginal productivity of labor, and therefore thedispersion of resulting pay among those engagedin an activity, increases with the scale (or number)of individuals engaged in that activity. Under most,if not all reasonable distributional assumptions,dispersion of ability and hence dispersion in payincreases with the number of workers, because thelikelihood of drawing extremely high or low abil-ity workers from the distribution increases with thenumber of workers drawn (i.e., firm scale). Basedon this model, the more employees that a firm has,the greater will be the dispersion of worker abili-ties. Because greater dispersion in ability generatesfocal individuals of very high ability and there-fore very high pay, as scale increases so does themagnitude of envy and resulting social compari-son costs. Thus, unless management takes steps toalleviate these envious feelings, the firm can expectsocial comparison costs from reduced effort, non-cooperativeness, influence activities, departures,sabotage, or departure to increase with scale.9

8 While there are clearly limits to the number of comparisonsin which an individual can engage, the hierarchical structure oforganizations generates de facto comparisons; workers compareto focal workers and managers compare pay of their subordinateswith other managers’ subordinates. Our assumption is that evenin the absence of direct personal contact, word of inequity travelsrapidly through the hierarchy. In particular, word of the highestpaid worker, what we refer to as the focal worker, travels thefastest.9 While not a focus of our study, note that firms will oftenseek to actively reduce the variance in ability by screening outthose at either the low or high tail of the organization. Some

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

Consequently, as the scale of the activity in-creases, the pressure to attenuate the stimulusto these rising comparison costs also increases.As the social comparison costs of rewarding themarginal productivity of labor increase, the man-ager becomes more likely to either horizontallycompress pay, for instance, paying everyone theaverage marginal productivity of labor, or to com-promise the technologically efficient productiontechnology in a way that reduces interaction amongworkers and limits their ability to view each otheras salient referents. Either choice imposes its ownset of costs on the firm. A decision to compresspay imposes predictable costs of reduced workereffort and adverse selection. For instance, highability workers are likely to exit the firm in searchof firms that will pay them their marginal prod-uct of labor, while low ability workers will beparticularly attracted to this compensation policyfrom other firms paying the marginal product oflabor (see Zenger, 1992). While the manager mayelevate pay to retain these high ability workers(Akerlof and Yellen, 1990), this choice has pre-dictable costs. The manager must either overpayfor the low ability employees also attracted to thefirm or heavily invest in screening procedures thatreduce their number.

A decision to subdivide an activity into geo-graphically or socially isolated groups may de-crease social comparison and social comparisoncosts, but at the expense of any scale economiesthat arise from team production that is compro-mised by this technology choice. For instance,subdividing workers into colocated groups maydecrease social comparisons across the entire orga-nization by shaping social referents and inhibitinginformation flow and affect individual responses toenvy by decreasing opportunities to engage in non-cooperative behavior. Yet, it is not clear that suchinternal subdivisions are particularly effective inconstraining these social comparisons. Managersalso are susceptible to invidious comparisons and,according to our view, invest in actions to reducetheir own feelings of envy that arise from com-parisons with other managers regarding the com-pensation of subordinates. For instance, managersexperience envy or anticipate feelings of envy

organizations conclude that extremely high ability individualsare simply ‘too costly’ to retain, where these costs are not merelythe direct costs paid to the retained high ability individuals, butrather the additional comparison costs triggered throughout theremainder of the organization.

from their subordinates, when they observe oth-ers managers’ subordinates earning more than theirsubordinates. Consequently, subdividing an activ-ity within the firm may do little to increase themanager’s capacity to differentially reward thesegroups. To truly reduce comparison costs mayrequire changing the boundaries of the firm andreducing activity scale.

Thus, as the scale of an activity increases, thesocial comparison costs of rewarding the marginalproduct of labor rise. As a consequence, the man-ager must choose to either weaken incentives,assigning a common level of pay to all work-ers, or simply compromise production technology.This compromise can take two forms: breakingthe firm into smaller internal units that are some-what socially or geographically isolated, or moredramatically curtailing the boundary of the firmitself. Thus, our prediction is that in attempting tolink individual pay to performance, as the scale ofan activity increases, social comparison costs riseand as a consequence compressing wages, compro-mising production technology, or constraining firmboundaries all become more likely.

Activity scope

We now turn our attention to how a firm’s activ-ity scope influences social comparison costs. Ourargument is that social comparison costs grow asthe marginal productivity across activities becomesincreasingly dispersed. To explore this argument,consider a firm that manages an array of het-erogeneous activities that differ in their marginalproductivity. For convenience, assume that allemployees engaged in each activity receive theaverage marginal product of labor for the activ-ity. In essence, we offer employees a horizon-tally compressed wage within activities in order tofocus on the effects of variation across activities.We say a firm displays scope when it integratesinto two or more activities with varying averagemarginal products. The scope of the firm increasesthe more dispersed the average marginal product ofactivities. Also assume that the production technol-ogy of the firm requires at least some interactionamong the diverse activities, which implies thatthere exist efficiency benefits from colocation ofactivities and that the combination of this coloca-tion and interaction of workers across the differ-ent activities ensures that the firm represents eachemployee’s salient reference group. Note again

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm

that some of this social comparison may occurindirectly through the managerial hierarchy.

Under these assumptions, a firm with only oneactivity incurs low social comparison costs becausepay is uniform within the activity and there is noother activity with a different pay level with whichto compare. When the firm integrates a secondactivity that differs in its average marginal productfrom the first, workers within these two activitiesbecome the salient referent group and the poten-tial for envy arises. We assume that the greater thescope of activities, where scope is here defined asthe dispersion (the difference between the maxi-mum and all others) of average marginal products,the greater will be feelings of inequity among thoseworkers receiving lower income. According to ourlogic, in response workers pursue behaviors toreduce these envious emotions thereby imposingsocial comparison costs on the firm. Thus, feel-ings of inequity and the corresponding comparisoncosts increase directly with the scope of activitieswithin the firm.

If disparate activities—activities with dispersedaverage marginal products of labor—are bundledwithin one firm, the manager faces a range ofoptions to address the potentially high comparisoncosts that would result from efforts to compensatebased on average marginal productivity. Managerscan compress wages vertically and no longer paythe average marginal product for each activity.However, much like horizontal wage compression,such vertical wage compression also imposes sig-nificant costs on the firm. If those employed inactivities with high average marginal productivityof labor are paid well below that average, thenthose engaged in these high productivity activi-ties are likely to exit the firm in search of firmsthat do not vertically compress wages or that com-press wages less so. Our Harvard, Tenneco, and toyfactory illustrations all provide evidence consistentwith this scenario. If the firm instead chooses tosimply elevate the wages of those engaged in activ-ities with lower average marginal product of laborto be more similar to those with higher averagemarginal product of labor, this imposes its ownobvious costs of overpayment.

Alternatively, the manager can constrain socialcomparison costs by departing from the technolog-ically efficient production technology, for instance,isolating disparate activities and limiting what maybe highly valuable interaction among them. Ofcourse, such efforts may only partially constrain

comparison costs and impose their own additionalcosts in terms of foregone productivity. In deter-mining their best response, managers must con-sider the fundamental trade-off between socialcomparison costs arising from envy and productiv-ity losses coming from the adoption of inefficientcompensation and technology. Moreover, as activi-ties become more dispersed in terms of the averagemarginal product of labor, both the comparisoncosts of rewarding average marginal product andthe costs of vertically compressing wages rise. As aconsequence, as activities become more dispersedin their average marginal products, constraining thevertical boundaries of the firm may become theeffective response.

Note that the increase in comparison costsimposed by dispersion in the marginal productiv-ity of activities is operative at both ends of thedistribution. Managers who internalize activitieswith low average marginal productivity activitiesfind it very costly and difficult to maintain lowpay. The envy felt and the resulting comparisoncosts are reduced by placing the activity in anorganization composed of activities with more sim-ilar average marginal productivity and more simi-lar pay. Indeed, much outsourcing occurs becausemanagers are unable to adopt or maintain ‘mar-ket’ wages for low productivity activities. Instead,social comparison costs in the form of influenceactivities or reduced effort drive managers to ele-vate these wages. On the other end of the spectrum,managers who internalize activities with very highmarginal productivity also find it costly to adoptmarket wages for these high productivity activ-ities because low marginal productivity workersimpose social comparison costs. Thus, our predic-tion is that social comparison costs associated withproviding market-like incentives increase as theactivity scope of the firm increases. Consequently,the more divergent is an activity’s average individ-ual output from the average individual output of allother activities within the firm, the more likely thatactivity will be outsourced or the wages of thosewithin the activity vertically compressed to matchthe other activities of the firm.

Interactions between scale and scope

To this point in our discussion of scale and scope,we have examined two simplifications of the firm.In examining scale, we limited the firm to a sin-gle activity. In examining scope, we limited the

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

J. A. Nickerson and T. R. Zenger

firm to rewarding average marginal compensationfor each activity, that is, horizontally compress-ing wages within activities. However, firm scaleand scope can interact in an important way toshape firm boundaries. In particular, we contendthat the social comparison costs that accompany anincrease in the firm’s activity scope can increasewith the aggregate scale of the firm. Thus, con-sider two single activity firms, one that is ratherlarge with 10,000 workers and another that is quitesmall with 50 workers. When the small firm seeksto add a new activity with a higher marginal prod-uct of labor and to reward those engaged in thatactivity, based either on average marginal prod-uct or individual marginal product of labor, the50 lower paid workers engage in comparison, feelenvy, and impose comparison costs. When thelarger firm attempts to add the same activity andreward marginal product of labor, 10,000 employ-ees engage in comparison, feel envy, and imposecomparison costs. Of course, admittedly some ofthis comparison is indirect, because not all employ-ees will have direct contact with the newly addedemployees. Indeed, it is likely that a greater per-centage of employees in the small firm will havedirect contact with the newly added activity. How-ever, as we have previously discussed, the manage-rial hierarchy, as well as informal networks withinthe firm, will ensure that comparison costs, thoughperhaps at a diminished level, extend beyond theboundaries of those who directly observe theseindividuals. Thus, as long as there are positivecomparison costs imposed by all within the bound-aries of the firm, then the comparison costs ofadding this additional activity rise with the aggre-gate scale of the firm. Consequently, larger firmsin terms of the number of employees, whetherthey are engaged in common or disparate activities,confront higher comparison costs in attempting toincrease the activity scope of the firm than smallerfirms. As firm size increases, vertical pay compres-sion becomes more likely. Similarly, as firm sizeincreases, management is more likely to either con-strain the boundary of the firm, and forego integra-tion, or compromise on production technology byisolating geographically this newly added activity.

DISCUSSION

Our theory suggests that social comparison costsplay a pivotal role in shaping the boundaries and

internal design of firms. We see our theory of socialcomparison costs as playing a role in organiza-tional failure that is analogous to the role thattransaction costs play in market failure. Whiletransaction cost economics views hierarchy as adevice to attenuate high transaction costs associ-ated with market failures, social comparison costeconomics views the market as a device to atten-uate high social comparison costs associated withorganizational failures. Thus, while market failurescreate a type of centripetal force for moving activ-ities out of the market and into a firm, our theoryexplains when and how organizational failures cre-ate a centrifugal force for moving activities out ofthe firm and into the market.

Our theory of social comparison costs also hasdirect implications for the scope and scale of thefirm. We argued that the larger the scale of anactivity within a firm involving an intermediatedegree of team production, the more likely the firmis to horizontally compress wages with the accom-panying reduction in incentives. Consequently, thelarger the activity, the more likely the firm is topartially outsource the marginal addition to thatactivity. Thus, a small firm is better able to offerworkers their marginal product of labor. Theseincentives yield a more productive set of work-ers than larger firms. Our toy factory illustrationmay provide a case in point. It might have beenwiser for the toy manufacturer to outsource the toypainting activity and benefit from the high levelof worker productivity through a market interfacerather than keep the activity inside the firm, whichultimately led to compressed wages, a loss of pro-ductivity, and the departure of specially trainedworkers.

A firm may also benefit from outsourcing whenits necessary activities are diverse in scope. Ourtheory predicts that the firm may benefit by out-sourcing those activities that are most distant interms of their individual marginal product from theaverage activity. For instance, Tenneco’s acquisi-tion of HOMC internalized a set of activities witha very different set of individual marginal prod-ucts compared to other activities within the firm.The resulting horizontal and vertical wage com-pressions experienced by HOMC employees ledto a high departure rate and, ultimately, an effi-ciency loss for Tenneco. Structuring a relationshipwith HOMC through a contractual interface mighthave led to a superior outcome. Of course, movingan activity outside the boundaries of the firm may

Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strat. Mgmt. J. (2008)DOI: 10.1002/smj

Envy, Comparison Costs, and the Economic Theory of the Firm