Environmental exposure of a simulated pond ecosystem to a ...

Transcript of Environmental exposure of a simulated pond ecosystem to a ...

HAL Id: hal-01919878https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01919878

Submitted on 1 Apr 2019

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open accessarchive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come fromteaching and research institutions in France orabroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, estdestinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documentsscientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,émanant des établissements d’enseignement et derecherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoirespublics ou privés.

Environmental exposure of a simulated pond ecosystemto a CuO nanoparticle-based wood stain throughout its

life cycleMelanie Auffan, Wei Liu, Lenka Brousset, Lorette Scifo, Anne Pariat, MarcosSanles, Perrine Chaurand, Bernard Angeletti, Alain Thiéry, Armand Masion,

et al.

To cite this version:Melanie Auffan, Wei Liu, Lenka Brousset, Lorette Scifo, Anne Pariat, et al.. Environmental ex-posure of a simulated pond ecosystem to a CuO nanoparticle-based wood stain throughout itslife cycle. Environmental science .Nano, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2018, 5 (11), pp.2579-2589.�10.1039/c8en00712h�. �hal-01919878�

EnvironmentalexposureofasimulatedpondecosystemtoCuOnanoparticlebased-woodstainthroughoutitslifecycleMélanieAuffana,b,c*,WeiLiua,b,LenkaBroussetb,d,LoretteScifoa,b,AnnePariata,b,MarcosSanlesa,PerrineChauranda,b,BernardAngelettia,b,AlainThiéryb,d,ArmandMasiona,b,JérômeRosea,b,c

Indoor aquaticmesocosmswere used to assess the behavior of fragmented products of a wood stain containing CuOnanoparticles in a simulated pond ecosytem for 1 month. Byproducts of degradation containing Cu are likely to bereleasedduringtheuseandend-of-lifeofthiswoodstain.Overtwomonths,apondecosystemwasmimickedin60Ltanksand exposed in environmentally relevant conditions to fragmented products of CuO nanoparticle-basedwood stain orpristine CuO nanoparticles. Cu (bio)transformation and (bio)distribution within different environmental compartments(e.g. water, sediments, benthic grazers) were carefully analyzed. Because of the presence of the stain matrix, CuOnanoparticlescontainedinfragmentedproductswerelessbio-physical-chemicallytransformed(dissolution,complexation)withrespecttopristinenanoparticles.After28days,only1%oftheCuinjectedfollowingfragmentedproductexposureremained in thewater column (0.08 µg.L-1), against 10% for the pristine CuO nanoparticles (2.67 µg.L-1). Among these~10%, ~51% were dissolved Cu species (1.35 µg.L-1). These results are discussed with respect to the ecologicalcompartments in which they accumulated, and to the dose to which aquatic organisms with distinct life traits wereexposed.

INTRODUCTIONIna life cycleperspective, researchon the releaseofnanoparticles fromnanoproducts is a growing field 1. Engineerednano-objects, their aggregates and agglomerates (NOAA)2, 3 are incorporated in different solid or liquid matrices as in cement 4,cosmetics5,orwoodstain6thatareusedinoureverydaylives.TheseNOAAmaybereleasedduringtheproduction,theuseofthenanoproductsbyconsumers,butalsoduringtheirdisposalandend-of-life.GatheringinformationonthereleaseofNOAAatdifferentstagesofthevaluechainisthereforeimportantfordefiningthehotspotsofreleaseandforassessingthehumanandenvironmentalexposureneededforarealisticriskassessment1.Ofthe1814nanoproductsinventoriedin2015,31%usedNOAAtoconferantimicrobialprotection7.Amongthem,antibacterialcoatings are of scientific and industrial interests because they are a promising route to potential environmentally friendlyapplications8.Theyareparticularlyusedinthebuildingindustryasindoorandoutdoorcoatingsdesignedforprotectionagainstmoldandmildew.Indeed,theuseofantibacterialNOAA(e.g.TiO2,Ag,CuO,CeO2)decreasetheprobabilityofmicrobial,fungal,andalgalgrowthonthecoatedsurface9,10.CuONOAAareofparticularinterestbecauseinadditiontowoodpreservationtheyalsoprovidesaestheticfunctionalitytosoftwoodcladding1.OnceCuONOAA-basedcoatings(e.g.acrylicpaint)areappliedtothewood, the cupric ions react with carboxylic and phenolic groups from cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. This leads to thehomogenous distribution of the ions in the wood cells, including penetration through cell wall voids 11 which enhance thebactericidalandantifungalproperties.However,atdifferentstagesoftheirvaluechainallthesenano-basedcoatingsarelikelytoreleaseNOAA6intheenvironment.Inasafe(r)bydesignperspective,itisworthensuringaboutthequantity,thenature,andthespeciationofNOAAandtheirdegradationbyproductspotentiallyreleasedduringaging,disposal,discharge,etc.The main goal of this study was to assess in environmentally relevant conditions the behavior and fate of byproducts ofdegradationcontainingNOAAlikelytobereleasedfromCuONOAA-basedacrylpaintdevelopedforwoodprotection.Twomainchallengeshadtobefaced:(i)todevelopamethodologyenablingtospeedupthedegradationofthepainti.e.toincreasethesurface area at the paint/water interface while keeping material identical to the one in the real product; (ii) to assess theecosystemexposuretothepaintinenvironmentallyrelevantconditionsi.e.realisticdosesandonthemid-term.Nowacketal.(2016)developedmethodstocharacterizeandquantifyNOAAreleasedfromcompositesamplesthatareexposedtoenvironmentalstressors1.Aquickandreliableapproachprovidedmaterialsinhundredsofgramquantitiesmimickingactual

releasedmaterialsfromcoatingsbyproducingfragmentedproducts(FP).TheelasticitymodulusofthematrixwasproposedascriterionforFPprocessing1.Formatriceswithanelasticitymodulusintherangeof109Pa,fragmentationcanbeperformedbycryomilling tosimulate thematerials’ lifecycle.However, forviscoelasticmatrices,asanacrylicpaint (10-7Pa), itneeds tobedepositontoahardsubstratebeforefragmentation.Forstudiesinaqueousmedia,analternativewasfoundwhichconsistedintransferringFPs inMilli-Qwater justaftercryomilling.Thefragmentssuspended inwaterthenavoidedmergingevenatroomtemperature.Thisprotocolwasused togenerateFPwith larger surfaceareaof theCuONOAA-basedacrylpaintused in thisstudy.IndooraquaticmesocosmswereusedtoassesstheenvironmentaltransformationofthelatterCuONOAA-basedacrylpaintandthe ecosystem exposure to the byproducts of transformation. Mesocosms are experimental systems designed to simulateecosystems12andareaninvaluabletoolforaddressingthecomplexissueofexposureduringnano-ecotoxicologicaltesting.Thisexperimentalstrategyhasalreadybeenusedtostudythebehaviororimpactsofpristinenanoparticles(i.e.atthefirststagesofthe life cycle) 13, 14 and the release of silver from commercialized nanoproducts 15. In the current study, indoor aquaticmesocosms(60L)wereadaptedtoassesstheexposureofecosystemstotheFPofCuONOAA-basedacrylpaint(CuO_Acryl_FP)inafashionthataccommodatesthecontrolrequiredtoelucidateunderlyingmechanismsatvarioustimeandspatialscales16.Inaquatic ecosystems, CuO_Acryl_FP will be controlled by physical-chemical change (aggregation, sorption of (in)organicsubstances,redox,etc.)aswellasecologicalfactors(ecologicalfeedingtype,trophictransferpotential,etc.).Theseparametersare most of the time studied separately in the literature. Using indoor aquatic mesocosms, this study will address the(bio)transformation,(bio)distributionandbioavailabilityofthereleasedmaterialswithindifferentenvironmentalcompartments(e.g. water, sediments, biota), and will identify the compartments where concentrations will be the highest 16-18. Such anapproach is undisputable to generate reliable exposure and impact data and for their integration into environmental riskassessmentmodelsrelatedtonanotechnologies.Inthisstudy,thebehaviorandfateofCuO_Acryl_FPinapondecosystemwillbecomparedtopristineCuOnanoparticles(CuO-NOAA).Becauseofthepresenceofpaintmatrix,wehypothesizedthattheCuOcontained in the FPwill be less available to reactwith their environment (dissolution, complexation)with respect to pristinenanoparticles.Moreover,assumingthatthekineticsofbio-physical-chemical transformationsofCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FPwouldbedifferent,wewillassesswhethertheecologicalcompartmentsinwhichtheywillaccumulatewouldbeimpacted.

MATERIALANDMETHODSCuO-NOAAandacrylicpaint

Commercial CuO nanopowder (called CuO-NOAA) were provided by PlasmaChem GmbH (Germany). These NOAA werepreviouslycharacterizedbyOrtellietal.(2017).Theyweresphericalwithprimaryaveragediameterof12±8nm(TEMsize),aspecific surface area (BET) of 47m2.g-1, an average hydrodynamic diameter in their stock suspension at 140 ± 5nm, and anisoelectric point at pH 10.3 11. These NOAA were incorporated in acrylic paints serving as reference compounds for woodpreservativecoating.High-glossacrylicwoodcoatingcontaining43%whitepigmentTiO2(non-nano)passivatedwithanaluminacoatingwereused19.Theviscoelasticityofthispaintwasestimatedaround10-7Pa.ChemicalandcolloidalstabilityofCuO-NOAAinbatch

A stock suspension of CuO-NOAA in Volvic® water was prepared at a CuO concentration of 9.9 mg.L-1. From this stock, 6suspensionsat1mg.L-1CuOwerepreparedinVolvic®waterwithafinalvolumeof100mL.Twocontrolbeakerswithonly100mLofpureVolvic®waterwerealsoused.Threeofthem(onecontrolandtwoCuO-NOAAsuspensionsat1mg.L-1)wereexposedtolightusingaPhilips®400WMetalhalidelamp(UV+visible).Theotherbeakerswerecoveredwithaluminumfoilsandmaintainedinthedark.After0,2h,5h,1day,2days,7daysand16daysundermagneticstirring,10mLofeachsuspensionweresampled.Ultracentrifugationat50000rpmfor1h(UltracentrifugeBeckmanCoulter®OptimaL-100XP)wasusedtoseparateparticulatefromdissolvedCu. The upper 4mL of the supernatantwere sampled, acidifiedHNO3 67%, and analyzed by ICP-MS (NexION300X, Perkin Elmer®) for dissolved Cu.Moreover, the colloidal stability of the CuO-NOAA in Volvic® water was evaluated bymeasuringthesizedistributionandzetapotentialusingaZetasizerNanoZS(Malvern®).FragmentationoftheCuO-NOAA-basedpaint

The production of fragmented products (FP) of CuO-NOAA treated acrylic paint (called CuO_Acryl_FP)was first optimized toavoidfragmentaggregationaftermilling.Amongalltheprotocolstested,theoneleadingtothebestdispersioninsuspensionisbrieflydescribedherein.Acrylicpaint filmswith1.5% (weight)CuO-NOAAweredepositedonpolyethylene (PE) foils to formsolidfilmsafter3daysdrying.Beforegrinding,paintfilmswereremovedfromthePEfoils,cutintoca.5x5mmsquaresusingscissors, placed in a polypropylenedisposable vial and stored at -10ºC. 2.5 g of frozenpaint sampleswereplaced into agatemortarformanualgrinding.Liquidnitrogen(LN2)wasimmediatelyaddedtoavoidpaintwarm-upandmanualgrindingstartedsimultaneously.Grindingwasperformedfor2minuteswithregularLN2additiontocompensateforevaporation.Thenasievingat0.63mmwasperformedinordertoeliminatethelargestpaintFP.Aftergrinding,LN2wasevaporatedand100mLofeitherVolvic® water were used to rinse the tools (pestle and scraper) and collect paint fragments in the mortar. Suspensions of

CuO_Acrylic_FPinVolvic®waterwereanalyzedbylasergranulometryonaMasterSizer3000(Malvern®).Suspensionsweremixedvigorouslyandhomogenizedbeforebeingdiluted50timestooptimizethemeasurement.Signalaveragecorrespondedto100measurementswithabout1hourscanforeachsample.

Mesocosmsetupanddosing

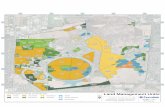

Mesocosmexperimentswereimplementedusing750x200x600mmglasstanksdescribedbyref.16,18(figure1).Brieflyeachtankiscomposedby12mm-thickmonolithicglasspanels.Fiveholesweredrilledatmid-heightofthetankandwereconnectedto the pump. Mesocosms were designed to simulate pond ecosystems. Therefore, organisms chosen for this study werepicoplankton as primary producer (bacteria, algae, protozoa, etc. from natural inoculum) and Great Ramshorm snail(Planorbariuscorneus(L.,1758))asabenthicgrazer.ThenaturalinoculumandP.corneuswerecollectedinanon-contaminatedpondpartoftheNatura2000reservenetwork(43.3464N6.259663E).

Figure1. (top)Pictureof the indooraquaticmesocosms. (bottom)TotalconcentrationofCuO injected in themesocosms followingCuO_Acryl_FPandCuO-NOAAtreatment(3timesaweekfor4weeks).TheconcentrationsweremeasuredbasedonthechemicalanalysisofCuO_Acryl_FPandCuO-NOAAsuspensionsusedforinjections.

Mesocosmexperimentsrequiredtwophases.PhaseI launchedinOctober2015consistedintheacclimationandequilibration.Tankswerefilledwith6-8cmartificialsedimentscontaining89%SiO2,10%kaoliniteand1%ofCaCO3w/w

16.Primaryproducerswerebroughtby~300gofwater-saturatednaturalsediment(sievedat200µm)laidatthesurface.Themesocosmswerethengently filledwith50LofVolvic©waterwithpHandconductivityclosetothenaturalpondwater(pH7,11.5mg.L-1Ca2+,13.5mg.L-1Cl-,71mg.L-1HCO3

2-,8mg.L-1Mg2+,6.3mg.L-1NO3-,6.2mg.L-1K+,11.6mg.L-1Na+).Aftertwodays,thephysical-chemical

parameters were stabilized (turbidity, pH, dissolved O2, redox). Then 19 adult P. corneus were added per mesocosm andacclimatizedforoneweek.Theorganismdensityandthemale/femaleratiowereselectedaccordingtothenaturalbiotope.PhaseIIwasdedicatedtotheexposureperiodtoCuO_Acrylic_FPandCuO_NOAA.Amultipledosingscenariowasselectedona4weeks-period.Atotalof12injectionsoflowandrealisticCuOconcentrationswereperformedasdetailedinfigure1.Attheendof the experiment, final concentrations of 28.2 µg.L-1 for the CuO_Acryl_FP and 25.3 µg.L-1 for the CuO-NOAAwere reached(figure 1). In addition, 2 control mesocosms without any dosing in the water column were run. During phase I and II,temperature,pH,conductivity,redoxpotential,anddissolvedO2,weremeasuredevery5minatmidheightofthewatercolumnusingmulti-parameterprobes(Odeon®OpenX)andatthewater/sedimentinterface(upto10mmbelowsurficialsediment)andmidheightofthesedimentusingplatinum-tippedredoxprobes.Aday/nightcycleof10h/14hwasappliedusingfullspectrum

light(Viva®lightT8tubes18W),androomtemperaturewaskeptconstant16.Arefillwithultrapurewaterwasperformedweeklytocompensateforevaporationwithoutincreasingtheconductivity.Mesocosmsamplingandanalysis

Chemicalanalysis.DuetothehighamountofpigmentaryTiO2withinCuOtreatedpaint(43%ofpigmentaryTiO2inmass),weattemptedtousetitaniumastracerofthepaint.Then,thedistributionofCuandTiinthemesocosmswasquantifiedbyCuandTicontentsinsurficialsediments(depthofsamplingestimatedabout0.9±0.4cm)18, inthewatercolumn(at~10cmfromtheair-water interface), and in the dissected digestive glands of P. corneus using ICP-MS (NexIon 300X, Perkin Elmer®). Surficialsedimentswere sampledat threedifferent locationsandpooledbeforedrying.All the samplesweredigestedat180°C in anUltraWAVEmicrowavedigestionsystem.Watersamples(2mL)weredigestedwith1mLHNO367%(Normatom®)and0.5mLHF47%-51%(PlasmaPure®).Forsedimentsamples(50mg),amixtureof3acids(1mLHCl34%(Normatom®),2mLHNO367%,0.5mLHF 47%-51%)was used. Finally, digestive glands ofP. Corneus were dissolved in 1mLHNO3 67%, 0.5mLH2O2 30%-32%(PlasmaPure®)and1mLHF47%-51%.All theCuandTiconcentrations inorganismspresentedareexpressed inmg.kg-1ofdrymatter.Moreover, the dissolved concentrations of Cu and Ti in thewater columnwas assessed using ultrafiltration (Amicontubes, 3KDa) and filtratemeasurements by ICP-MS (NexIon 300X, Perkin Elmer®).Other elementswere alsomeasured in thewatercolumn,sediments,anddigestiveglands(asMg,Zr,Ni,Mo,Sr), inordertousethemaspotential internaltracers.Eachmeasurementwasperformed in triplicateand themeasurementqualitywascontrolledusingcertified referencematerials (asmusseltissuesCE278kC1fromERM®).Particlecounting.Thenumberofcolloidalparticlessuspendedinmesocosmwatercolumnsweremonitoredat10cmbelowthewatersurfaceusinganopticalparticlecounter(OcchioFlowcellFC200S+HR)onceaweek.Picoplankton counting.Picoplankton (with cells between0.2 to2µm) concentrationsweredeterminedat the surfaceof thesediment (0.5±0.1mmdepth)and in thewatercolumn (10cmbelowtheair-water interface)onaweeklybasis. FivemLofwater and 15mL of sediment were sampled, treated with formaldehyde (3.7%), and stored at 4°C before counting. Beforepicoplankton counting, 1mL of eachwater column samplewas centrifuged (5.9× g at 4°C for 15min), and 200 µL of eachsedimentsamplewastreatedwith800µLof0.1mMsterile tetrasodiumpyrophosphateandvortexedwithasteelball for30seconds.Forthecounting,10µLofeachsamplewasmixedwith5µLof3µMSYTO®9GreenFluorescentNucleicAcidStainanddroppedonaglassslide.Concentrationofpicoplanktonwasthemean±standarddeviationoffivecounts.Statisticalanalysis

All the analyses were performed in triplicate and the mean and the standard deviation of the results were presented. Theanalysisofvariance(ANOVA)methodwasusedtotestthestatisticalsignificanceoftheresults,andaprobabilityvalues(p)lessthan0.05wasconsideredasstatisticallysignificant.Statisticalsignificantdifferenceswerepointedbyasterisk.

RESULTSANDDISCUSSIONColloidalandchemicalinstabilityofCuO-NOAAinVolvic®water

To optimize the design of the exposure in indoor aquatic mesocosms (sampling, duration, analysis, etc.), and to betterunderstand the physical-chemical mechanisms of transformation of CuO-NOAA, a preliminary exposure of the CuO-NOAA inabioticVolvic®waterwasperformed.Theobjectivesof thisexperimentweretodeterminethecolloidalstabilityofCuO-NOAAand their kineticsofdissolutionover time (2h,5h,1day,2days,7days,16days) in conditions close to thewater columnofmesocosms.Thisexperimentwasperformedinbatchbyvaryingtheilluminationregimen.

Figure2.Zetapotentialvs.timeinVolvic®water.Curveswereaveraged(±standarddeviation)ofthreereplicatesforCuO-NOAAsuspensionsexposedtolightordarkconditions.pHvaluesareprovidedinitalics.

ZetapotentialofCuO-NOAAsuspensionwasmeasuredjustaftertheexposure(t0)toVolvic®wateraround-15mVand-20mV

(pH7.4).Itslightlyfluctuatedoverthefirst20hofexperimentbutdidnotshowanysignificantdifferencebetweenlightanddarkconditions(figure2).ThehigherzetapotentialmeasuredforCuO-NOAAsuspensionsexposedtoUV-visibleradiationwerenottakenasarelevantfeaturesinceitwasalsoobservedatt0beforelightcouldhavehadanyinfluence.ThelackofsignificanteffectofilluminationregimenonthestabilityoftheCuOnanoparticlesdispersionswasalsoobservedbyChelonietal.(2016)ontheshort-term(<24h)20.ThezetapotentialvaluesobtainedinVolvic®waterhighlightedthecolloidalinstabilityoftheCuO-NOAAasalreadyobserved21.Misraetal. (2012)haveshownthat isotopicallymodifiedCuOnanoparticlesagglomeratedandstartedtosediment in freshwater water within an hour 22. Due to this instability, no zeta potential measurement could be done fordurations longer than 20 hours (figure 2). This aggregation corroborates the lack of accurate size measurements of CuOnanoparticlesinaqueousenvironmentintheliterature22.

Figure3.DissolvedCuvs.timeinVolvic®water.Eachpointwasanaverage(±standarddeviation)ofthreereplicatesforCuO-NOAAsuspensionsexposedtolightordarkconditionsandcontrols.Thedottedrectangularcorrespondstoazoominonthefirsthoursofexperiment.

CuO-NOAA dissolution was assessed over time and in dark and light conditions. Dissolved Cu concentrations measured inpresenceofCuO-NOAAsuspensionsweresignificantlyhigherthanbackgroundconcentrationsmeasuredincontrolbeakers(~1µg.L-1). Cu(OH)2 is expected tobe theprincipal cationichydrolysis product in theVolvic

®water. KineticsofCudissolutionaregiven in Figure 3. Cu release remained limited to 1% to 2.5% (10 to 20 µg.L-1) during the first two days of experiment, andincreasedupto~30%after7days(~250µg.L-1)whatevertheilluminationregimenwas.Chelonietal.(2016)exploredtheeffectof light with different spectral composition on the chemical stability of CuO nanoparticle and their effects to green alga(Chlamydomonasreinhardtii).Theirresultsshowedthatsimulatednatural lightand lightwithenhancedUVBradiationdidnotaffectthedissolutionofCuOnanoparticles20ontheshort-term(<24h).Interestingly,whilenotilluminationregimen-dependentduringoneweek,thedissolutionprocessbecamelight-sensitiveafter16daysofagingwith50%ofdissolvedCuunderUV-visiblelightagainst~20% in thedark (figure3).SuchadissolutionofCuOnanoparticlesappearedtobethekey factor triggering thereactiveoxygenspecies(superoxideanions,hydrogenperoxide)andDNAdamageresponsesinbacteria(Escherichiacoli)atlowsub-toxiclevels(0.1mgCu.L-1)23.Basedontheseresults,afastaggregationandsedimentationoftheCuO-NOAAwasexpectedinthemesocosmwatercolumn.Moreover, since in mesocosms CuO-NOAA were exposed to 10 h/day irradiation during 28 days (less intense irradiationcomparedtothebatchexperimentbutlongerduration),asignificantdissolutionofCuO-NOAAwasalsoexpectedinthewatercolumn.FastaggregationandsedimentationofCuO_Acryl_FPinVolvic®water

FPweregeneratedfollowingaprotocolcorrespondingto(i)thepreparationofCuONOAA-basedacrylicpaintfilmonPEfoils,(ii)themortargrindingofpaintfilm(removedfromPE) in liquidnitrogen,and (iii) thetransferofFPtoanaqueousphasebeforecompletewarmuptoroomtemperature.WhentheFPweretransferredtoVolvic®water,sizedistributionmeasurementsshowthat the average hydrodynamic diameters of the FP were larger than tens or even hundreds of microns. Freshly preparedsuspensionofCuO_Acryl_FPexhibitedonesizemodewithD10=20±4μm,D50=73±29μmandD90=190±86μm.ThediameterD10,D50, and D90 represents the smallest 10%, 50% and 90% of the particles in volume metrics. With time (two days), thehydrodynamicsizedistributionshiftedtolargersizeswithD10=28±4μm,D50=140±30μmandD90=434±117μm(Figure4).Basedonthesehydrodynamicdiametervalues,weexpectedthattheaggregationandsettlingdownoftheCuO_Acryl_FPwouldbefastin thewater columnof themesocosms. Such strong colloidal instabilitywasalsoobserved in artificial freshwaterusing FPofepoxy,polyolefin,polyoxymethylene,andcementcontainingnanoparticles24.

Favorablebio-physical-chemicalconditionsinmesocosms

Contamination (phase II) took place 3 times aweek during 28 days. During Phase II, several physical-chemical andmicrobialparametersweremonitoredtoassesstheglobalresponseofthemesocosmstothepresenceofCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FP.Physical-chemicalparametersmonitoredduringthewholeexperimentwereconstantduringthecontaminationperiod:dissolvedO2(11.1±0.6mg.L-1),redoxpotential(287±3mV)andpH(8.1±0.1)(seeSI,FigureS1).ORPprobesindicatedthatthewatercolumnwasoxidative(ca+290mV),whilereductiveconditionsprevailedinthesediments(ca-370mV).ConductivityincreasedstepbystepfromDay0(245±1µS.cm-1) toDay28(288±0.4µS.cm-1).Conductivitydropswererecordedduringtheweeklyrefillswithultrapurewater to compensate theevaporation.On thewhole,no significantdifferenceswereobservedbetweencontrolsandcontaminatedmesocosms.

Figure4.HydrodynamicdiametersmeasuredontheCuO_Acryl_FPfreshlypreparedsuspensionsand2days-agedsuspensionsinVolvic®water.

Naturalsuspendedparticlesarealsoimportanttomonitorsincetheycontrolthetransportofnanoparticlesintheenvironment25.AtDay0,40%ofthecolloidalparticleswereinthe0.4and0.9µmsizefractionwhateverthemesocosmswere(seeSI,FigureS2).Overtime,nostatisticaldifference(p>0.05)wasobservedbetweencontrolsandcontaminatedmesocosms(CuO_NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FP) in term of number of these [0.4 - 0.9 µm] colloidal particles. The increase observed at 14 days for the threeconditionstestedwaslikelyduetotheactivityofthebenthicgrazers.Finally,thenumberofpicoplankton(cellsbetween0.2and2 μm) was measured in the water column and surficial sediments (see SI, Figure S2). The total number of cells in surficialsedimentsremainedconstantovertimeandforallconditionstested(ca107cells.mL-1). Inthewatercolumn,aslight increasewasobserved from105 cells.mL-1 atDay0 to5.105-106 cell.mL-1 atDay28. Forboth thewater columnand the sediment,nosignificantdifferencesinthepicoplanktonnumberwereobservedbetweenthecontrols,contaminatedmesocosms(CuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FP).ThiswasalreadyobservedwithenvironmentallyrelevantconcentrationsofexposuretoCeO2nanoparticles17, 18.Consequently,during theexposure toFPandNOAA,ecological conditionsof the6mesocosms remained favorablewithoxygenation,pH,temperature,redoxpotential,suspendedmaterial,andnumberofprimaryproducers intherangeofnaturalconditions.Material-dependentpersistenceofCuinthewatercolumn

Waterandsedimentsampleswerecollectedatdays0,7,14,21and28.Aftermicrowave-assisteddigestionofthesamples,Cuand Ti were quantified by ICP-MS. Indeed, due to the high amount of pigmentary TiO2 within CuO treated paint (43% ofpigmentaryTiO2),weattemptedtouseTiastracerofthepaint.Figure5showstheCuconcentrationsmeasured inthewatercolumn as a function of time. Both Cu (figure 5) and Ti (see SI, Figure S3) were detected in the water column of controlmesocosmswithbackgroundconcentrationsaround1.37±0.12µg.L-1forCuand19.2±17.2µg.L-1forTi.Thecomparisonwithdissolvedconcentrationsmeasuredafterultrafiltrationat3kDarevealedthatca54%ofthebackgroundCuincontrolsconsistedinionicspecies,whileca98%ofthebackgroundTiincontrolswasunderparticulateform.ThiswasinagreementwiththelowsolubilityexpectedforTi-basedspecies.Regarding themesocosms contaminatedwith CuO-NOAA, an increase of the total Cu concentrationwas observed over time(figure 5). After 28 days of experiment, total Cu concentration rose up to 2.67 µg.L-1 in thewater columnwith 1.35 µg.L- ofdissolvedCu(ultrafiltrationthreshold<3kDa).Weestimatedthat~51%oftheCupresentinthewatercolumnandcomingfromCuO-NOAAwas dissolved (<3 kDa). The remaining ~49%were under particulate formor complexedwith organic compound.Indeed,Cu(OH)2 isexpectedtobetheprincipalcationichydrolysisproduct inpureVolvic

®water. Inthisoxidationstate(Cu2+),copperformsverystablecomplexeswithbothorganicandinorganic ligands.Suchcomplexation is likelytooccur inthewatercolumnofthemesocosms.After removing the background Cu concentration, we estimated that only ~10% of the total Cu injected (in the CuO-NOAAmesocosms) remained in thewater columnafter28days. Similarpercentagewas calculatedat 14days and21days. For the

mesocosms contaminatedwith CuO_Acryl_FP, no significant increase in Cu total concentrations nor dissolved concentrationswas evidenced in thewater column (always below the detection limit of 0.08 µg.L-1). This resultwas in agreementwith thestrongcolloidal instabilityoftheCuO_Acryl_FPobservedinpureVolvic®waterandhighlightsthatthe lifetimeoftheFP inthewatercolumnwasveryshort.UsingdifferentsimulatedleachingandUV/rainweatheringprotocols,Pantanoetal.(2018)assessthe release of dissolved Cu fromCuO-NOAA-treatedwood 19. The CuO acrylate barrier applied on thewood appeared to berobustandtoreleaseCuionsonly in lowquantitiesthatwereeasilymaskedbyenvironmentalortechnicalcontaminations19.OurresultsconfirmthatCuO-NOAAincorporatedintheacrylicpaintmatrix,willleadtonegligiblereleaseofCuionscontrarytopristineCuO-NOAAunderenvironmentallyrelevantconditions.Surficialsedimentsconcentratethepollution

Figure6showsthetotalCuconcentrationsdeterminedinsurficialsediments.Asinwatersamples,Cu(figure6)andTi(seeSI,FigureS3)werealreadypresentintheuncontaminatedsedimentsofcontrolmesocosms(averageof24.4±10.5mgCu.kg-1and2166±834mgTi.kg-1).Totalbackgroundconcentrationsincontrolsfluctuatedstronglyfromonesamplingpointtoanother.In contaminatedmesocosms, no specific trend in Cu and Ti total concentrations in surficial sedimentswere evidenced,withconcentrations never significantly different from control mesocosms. However, based on water column concentrations, weestimated that ~90%of CuO-NOAAand >99%of CuO_Acryl_FP injected atDay 28 settled down at the surface of sediments.AssumingthatalltheseCuwerehomogeneouslydistributedonthesediments,thisshouldhaveresultedinamaximumincreasein the surficial sediment of 6.2mgCu.kg-1 (for CuO-NOAA) and 7.7mgCu.kg-1 (CuO_Acryl_FP). These calculated valueswerebelow the standarddeviation calculated for thebackgroundCuandTi concentration in sedimentsof controlmesocosmsandexplainedthelackofsensitivityontheICP-MSmeasurementsinsediments.

Figure5.AveragetotalCuconcentrationsmeasured in thewatercolumnatdifferent timepointsof theexperiment forcontrol (CTL)mesocosmsandmesocosmscontaminated with either CuO_Acryl_FP or CuO-NOAA. Standard deviations observed between replicates were plotted in error bars. * represent data that aresignificantlydifferentfromcontrols(p<0.05).

Toincreasethesensitivityofthemeasurements,theconcentrationsofCuinsurficialsedimentwereexpressedasafunctionofNiconcentrationsthatwerehomogenouslydistributedinthesurficialsediments.TheevolutionoftheCu/Niratioovertimearepresented in figure7.Whileno significant increase in theCu/Ni ratiowasobserved in controls, time-dependent trendswereobservedforCuO-NOAAandtheCuO_Acryl_FP-contaminatedmesocosms.After2weeks,asignificantincreaseintheCu/NiratiohighlightthecontributionofCucomingfrombothCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FPinthesurficialsediments.SeveralmechanismscouldexplainsuchanincreaseoftheCuconcentrationinthesediments.ThiscouldberelatedtothecomplexationofCuionsbynaturalorganicmatterinthesurficialsediments26,theiradsorptiononsoilcomponentsasclays27,oralsotothesettlingdownoftheCuO-NOAAandtheCuO_Acryl_FP.Basedonthestrongcolloidalinstabilitypreviouslyobserved,itislikelythattheaggregationandsettlingdownmostlygovernedtheincreaseoftheCu/Niatthesurfaceofthesediment.WhilehomoaggregationofCuO-NOAAislikelytobenegligibleduetothe low particle concentrations expected in freshwaters compared to the concentrations of naturally occurring suspendedmatter,heteroaggregationattachment isexpectedtobeat theoriginof theircolloidal instability in freshwaterenvironments.The physical-chemical mechanism of hetero-aggregation of the CuO-NOAA at pH = 8.1 ± 0.1 is related to the electrostaticattractionbetweenthepositivelychargedCuOandthenegativelychargedclays(asthelateralchargesofkaolinite28)butalsopicoplankton (as bacteria, algae) 29. CuO_Acryl_FP as others breakup/fragmented/released particles of plastics, cement, andpaints 24, 30, 31were found very instable as soonas they areput in suspension. Their aggregation in thewater columnof themesoscosmwasattributedto the largesizeof theFP (D10=20±4μm,D50=73±29μmandD90=190±86μm) leading to their fastsettlingdown(Figure4).

Figure6.(A)AverageCuconcentrationsmeasuredinsurficialsedimentsat0,7,14,21and28daysofmesocosmscontaminatedwithCuO_Acryl_FPorCuO-NOAAandcontrolmesocosms. (B) Cu/Ni ratiomeasured in surficial sedimentsmeasured in controls andmesocosms contaminatedwith CuO_Acryl_FP or CuO-NOAA. Thestandarddeviationobservedbetweenreplicateswasplottedinerrorbars.*representdatathataresignificantlydifferentfromcontrols(p<0.05).

Interactionswithbenthicgrazers

P.corneusarebenthicgrazersthateatalgaeandbiofilmsat thesediment/water interface.TheuptakeofCufromCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FPbyP.corneuswasestimatedbydissecting,digestingandanalyzingthedigestiveglandsofspecimenssampledinmesocosmsat7,14,21and28days.TheconcentrationsmeasuredforthethreedifferentconditionsarereportedinFigure7forCu,andinFigureS3insupportinginformationforTi.BackgroundCuandTiconcentrationsweremeasuredinthedigestiveglands of unexposed organisms around 10.3 ± 1.5mg Cu.kg-1 (dryweight) and around 1.2 ± 0.4mg Ti.kg-1 (dryweight). ThesamplescomingfromCuO_Acryl_FPandCuO-NOAAmesocosmsdidnotshowstatisticallydifferentconcentrationwithrespecttocontrols.Allourattemptstouseinternaltracers(asNi,Sr,Zr,Mo,Mg)didnotshowsignificantresults.Asaconsequence,theuptake of CuO-NOAA or FP of paint by the organisms was not evidenced, in spite of their strong accumulation at thewater/sediment interface. It isnoteworthythat thechoiceof realistically lowdosingconcentrations for thisexperimentmadethedetectionofCucomingfromNOAAorFPinthedifferentcompartmentsextremelydifficultandespeciallyinlivingorganisms.Croteauetal. (2014)getaroundthis lackofsensitivityusingisotopicallymodifiedCuOnanoparticles(65Cu)tocharacterizetheprocessesgoverningCubioaccumulationinafreshwatersnailLymnaeastagnalis.Theexposureconcentrationusedintheirstudywas 6.3 mg Cu.kg-1 of diatoms 32. In the current study assuming that all the Cu introduced after 28 days settled downhomogeneouslyatthesurfaceofthesediments,theCuconcentrationscomingfromtheCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FPwouldbe6.2 and 7.7mg Cu.kg-1 of sediment respectively. Croteau et al. observed that L. stagnalis efficiently accumulated 65Cu afterexposureto65CuOnanoparticlesatsuchalowexposureconcentration.Theyestimatedthat80–90%ofthebioaccumulated65CuconcentrationinL.stagnalisoriginatedfromthe65CuOnanoparticles,suggestingthatdissolutionhadanegligibleinfluenceonCuuptake from thenanoparticles under their experimental conditions 32. Thepreferential bioaccumulationsof dissolved speciescomparedtonanoparticulateformsareknowntodependonthe lifestylesoftheaquaticspecies(filterfeedersversusbenthicgrazers) 17, 33. BothL. stagnalis andP. corneus are important grazers inbenthic freshwaterhabitats 34. Theyhave similar andunspecificingestionmodethroughthegastropodradulai.e.theirpreyselectiononthelevelofindividualfooditems(e.g.algalcells)isnotpossible35.BasedontheirsimilarlifestylecomparedtoL.stagnalis,wehypothesizedthatP.corneuswouldbeableto ingest Cu coming either from settled downCuO-NOAAor CuO_Acryl_FP after exposure in surficial sediments even if non-detectedbyICP-MS.

Figure7.AverageCuconcentrationsmeasuredinthedigestiveglandsofP.corneussampledat7,14,21and28daysinmesocosmscontaminatedwithCuO_Acryl_FPorCuO-NOAA,andcontrolmesocosms.Thestandarddeviationobservedbetweenreplicateswasplottedinerrorbars.

02468

101214161820

7 14 21 28

Conc

entr

atio

n (m

g/kg

)

Days

Total Cu in digestive glands

Control CuO_Acryl_FP CuO-NOAA

DifferentenvironmentalimplicationsbetweenFPandCuO-NOAAalongthelifecycle

WeacknowledgethattheFPobtainedbyourapproacharenotthematerialsreleasedfrompaintduringtheiruseordisposal,buttheyrepresentaninterestingapproximationandallowedtheproductionofhundredgramquantitiesofmaterialsfortestinginmesocosms.SuchanapproachallowstocomparethebehaviorandfateinapondecosystemofpristineCuOnanoparticlesvs.CuOnanoparticlescontainedintheFPofanacrylicpaint.Becauseofthepaintmatrix,wepreviouslyhypothesizedthat(i)theCuO-NOAA would be less available to react with their environment and to be transformed (oxidative dissolution) onceincorporated in theacrylicmatrix, and (ii) thekineticsofbio-physical-chemical transformationsbeingdifferentbetweenCuO-NOAAandCuO_Acryl_FP,theecologicalcompartmentsinwhichtheywillaccumulatedwoulddiffer.Theanalysisofthewatercolumnandsurficialsedimentsofmesocosmsoveronemonthofmultipledosing’sofCuO_Acryl_FPandCuO-NOAAconfirmedthosetwohypotheses(Figure8).Indeed,after28days~10%oftheinjectedCuremainedinthewatercolumnof the CuO-NOAA-contaminatedmesocosms (i.e.2.67 µg.L-1),while itwas below 1% for CuO_Acryl_FP-contaminatedmesocoms. Among these ~10% of Cu coming from the CuO-NOAA, ~51% of the Cu were dissolved species (i.e. 1.35 µg.L-1).Bondarenkoetal. (2013) reviewedtheecotoxicityofCuOnanoparticlesandCusalts towardenvironmentally relevantaquaticorganisms36.TheycalculatedmedianL(E)C50valuesfordissolvedCuandnanoparticulateCuOtowardspecieslivinginthewatercolumnoffreshwaterponds.L(E)C50ofCusalts(CuSO4,CuCl2)wereestimatedat0.02mg.L-1(min:0.004mg.L-1;max:0.07mg.L-1)forcrustaceans(Daphnia)andat0.075mg.L-1(min:0.0044mg.L-1;max:13.0mg.L-1)foralgae(chlorellasp.,Pseudokirchneriellasubcapitata,Nitellopsisobtusa).TheL(E)C50valuesofCuOnanoparticlesweremeasuredabout2.1mg.L-1(min:0.08mg.L-1;max:12.3 mg.L-1) for crustaceans (Daphnia) and at 2.80 mg.L-1 (min: 0.68 mg.L-1; max: 47.0 mg.L-1) for algae (Chlorella sp., P.subcapitata,N.obtusa)36.TheconcentrationofdissolvedCureleasedfromCuO-NOAAinthewatercolumnofthemesocosmsafter1month(~1.35µg.L-1)wasinthelowerrangeoftheseL(E)C50whileparticulateCu(~1.32µg.L

-1)was60to500timeslowerthantheminimumL(E)C50values. Ina lifecycleperspective, these resultshighlighted thatat theearly stages (i.e. productionand formulation)a specificattentionhastobepaidtoplanktonicorganismsandfilterfeedersthatcouldbeaccidentlyexposedontheshort-termtoCuionsreleased from pristine CuO-NOAA. However, during the use and end-of-life stages, the release of Cu from CuO-NOAAincorporatedinacrylicpaintwasverylowinthewatercolumnandnosignificantexposureoforganismslivingand/orfeedinginthewatercolumnisexpected.However,CuO_Acryl_FP(asCuO-NOAA)endedupquickly insurficialsediments(90%to99%ofCu)beingpotentiallyavailableforshort-andlong-termexposuretobenthicgrazers.Inotherwords,thesurficialsedimentswerefound to concentrate the Cu pollution coming from pristine CuO-NOAA and FP of CuO-based paint in a simulated pondecosystematalllifecyclestagesi.e.fromtheproduction,totheuse,andtheend-of-life.During the 28 days of exposure in mesocosms, the survival rates of P. corneus (< 2 % of mortality, data not shown) andpicoplankton(seeSI,FigureS2)wasnotaffectedbythepresenceofCuO-NOAAorCuO_Acryl_FP.Noacutetoxicitywasobservedduringonemonthonthetwotrophiclevelsi.e.benthicandpelagicpicoplankton’sandbenthicgrazers.Nevertheless,athoroughcharacterization of the biological responses (at the individual, sub-individual, and community level) is still needed to betterunderstandthebiologicalmechanismsofinteractions.Indeed,benthicandplanktonicmicrobialcommunitiesmightbeaffectedby theexposure tonanoparticulateordissolvedCuasalreadyobserved forbacterial community fromsoils 37.Moreover, theexposure of P. corneus to Cu via the surficial sediments might impact the mollusk physiology mainly on the hemolymphregulation;P.corneus’shemocyaninbeingametalloproteincontainingcopperatomsreversiblybindtoasingleoxygenmolecule38.

Figure8.DistributionoftheCufollowingCuO-NOAA(left)andCuO_Acryl_FP(right)afteronemonthofcontaminationoffreshwateraquaticmesocosmmimickingapondecosystem.Initalics:calculatedvalues.

CONFLICTSOFINTERESTTherearenoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWethankMargarethSwerdloffandAthenaNghiemfortheirhelpsduringbatchexperiments.Thisworkwassupportedbytheproject on SustainableNanotechnologies (SUN) that receives funding from the EuropeanUnion Seventh Framework Program(FP7)undergrantagreementnumber604305,and (ii) theFrenchANRfunding for theANR-3-CESA-0014/NANOSALTprogram.Theproject leadingtothispublicationhasreceivedfundingfromExcellence InitiativeofAix-MarseilleUniversity -A*MIDEX,aFrench“Investissementsd’Avenir”program,throughitsassociatedLabexSERENADEproject.ThisworkisalsoacontributiontotheOSU-InstitutPythéas.Finally,theauthorsacknowledgetheCNRSfundingfortheGDRiiCEINT.

REFERENCES1. B.Nowack,A.Boldrin,A.Caballero,S.F.Hansen,F.Gottschalk,L.Heggelund,M.Hennig,A.Mackevica,H.Maes,J.Navratilova,N.

Neubauer,R.Peters,J.Rose,A.Schäffer,L.Scifo,S.v.Leeuwen,F.vonderKammer,W.Wohlleben,A.WyrwollandD.Hristozov,Meeting the Needs for Released Nanomaterials Required for Further Testing—The SUN Approach, Environmental Science &Technology,2016,50,2747-2753.

2. I.T.12901-1,Nanotechnologies-Occupationalriskmanagementappliedtoengineerednanomaterials.Journal,2012.3. I.T.12901-2,Nanotechnologies-Occupationalriskmanagementappliedtoengineerednanomaterials.Journal,2012.4. N.Bossa,P.Chaurand, J.Vicente,D.Borschneck,C. Levard,O.Aguerre-Charioland J.Rose,Micro-andnano-X-raycomputed-

tomography: A step forward in the characterization of the pore network of a leached cement paste, Cement and ConcreteResearch,2015,67,138-147.

5. C. Botta, J. Labille,M. Auffan, D. Borschneck, H.Miche,M. Cabié,M. A., J. Rose and J.-Y. Bottero, TiO2-based nanoparticlesreleasedinwaterfromcommercializedsunscreensinalife-cycleperspective:structuresandquantities,EnvironmentalPollution,2011,159,1543-1548.

6. L.Scifo,P.Chaurand,N.Bossa,A.Avelan,M.Auffan,A.Masion,B.Angeletti,I.Kieffer,J.Labille,J.-Y.BotteroandJ.Rose,Non-linear release dynamics for a CeO2 nanomaterial embedded in a protective wood stain, due to matrix photo-degradation,EnvironmentalPollution,2018,inreview.

7. M.E.Vance,T.Kuiken,E.P.Vejerano,S.P.McGinnis,M.F.Hochella,Jr.,D.RejeskiandM.S.Hull,Nanotechnologyintherealworld:Redevelopingthenanomaterialconsumerproductsinventory,BeilsteinJournalofNanotechnology,2015,6,1769-1780.

8. A. Kumar, P. K. Vemula, P.M.Ajayan andG. John, Silver-nanoparticle-embedded antimicrobial paints basedon vegetable oil,NatureMaterials,2008,7,236.

9. S.Meghana,P.Kabra,S.ChakrabortyandN.Padmavathy,Understandingthepathwayofantibacterialactivityofcopperoxidenanoparticles,RSCAdvances,2015,5,12293-12299.

10. S. Chen, Y. Guo, H. Zhong, S. Chen, J. Li, Z. Ge and J. Tang, Synergistic antibacterial mechanism and coating application ofcopper/titaniumdioxidenanoparticles,ChemicalEngineeringJournal,2014,256,238-246.

11. S.Ortelli,A.L.Costa,M.Blosi,A.Brunelli,E.Badetti,A.Bonetto,D.HristozovandA.Marcomini,ColloidalcharacterizationofCuOnanoparticlesinbiologicalandenvironmentalmedia,EnvironmentalScience:Nano,2017,4,1264-1272.

12. FAO,Foodandagricultureorganizationoftheunitednations.Journal,2009.13. J.L.Ferry,P.Craig,C.Hexel,P.Sisco,R.Frey,P.L.Pennington,M.H.Fulton,I.G.Scott,A.W.Decho,S.Kashiwada,C.J.Murphy

andT.J.Shaw,Transferofgoldnanoparticlesfromthewatercolumntotheestuarinefoodweb,NatNano,2009,4,441-444.14. G.V.Lowry,B.P.Espinasse,A.R.Badireddy,C. J.Richardson,B.C.Reinsch,L.D.Bryant,A. J.Bone,A.Deonarine,S.Chae,M.

Therezien,B.P.Colman,H.Hsu-Kim,E.S.Bernhardt,C.W.MatsonandM.R.Wiesner,Long-TermTransformationandFateofManufacturedAgNanoparticlesinaSimulatedLargeScaleFreshwaterEmergentWetland,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2012,46,7027-7036.

15. D.Cleveland,S.E.Long,P.L.Pennington,E.Cooper,M.H.Fulton,G.I.Scott,T.Brewer,J.Davis,E.J.PetersenandL.Wood,Pilotestuarinemesocosmstudyontheenvironmental fateofSilvernanomaterials leachedfromconsumerproducts,ScienceofTheTotalEnvironment,2012,421–422,267-272.

16. M.Auffan,M. Tella, C. Santaella, L. Brousset, C. Pailles,M. Barakat, B. Espinasse, E. Artells, J. Issartel, A.Masion, J. Rose,M.Wiesner,W.Achouak,A.Thieryand J.-Y.Bottero,Anadaptablemesocosmplatform forperforming integratedassessmentsofnanomaterialriskincomplexenvironmentalsystems,Scientificreports,2014,4,5608.

17. M.Tella,M.Auffan,L.Brousset,E.Morel,O.Proux,C.Chaneac,B.Angeletti,C.Pailles,E.Artells,C.Santaella,J.Rose,A.Thieryand J. Y. Bottero, Chronic dosing of a simulated pond ecosystem in indoor aquatic mesocosms: fate and transport of CeO2nanoparticles,EnvironmentalScience-Nano,2015,2,653-663.

18. M.Tella,M.Auffan,L.Brousset,J.Issartel,I.Kieffer,C.Pailles,E.Morel,C.Santaella,B.Angeletti,E.Artells,J.Rose,A.ThieryandJ.-Y.Bottero,Transfer, transformationand impactsofceriananomaterials inaquaticmesocosmssimulatingapondecosystem,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2014,48,9004–9013.

19. D.Pantano,N.Neubauer,J.Navratilova,L.Scifo,C.Civardi,V.Stone,F.vonderKammer,P.Müller,M.S.Sobrido,B.Angeletti,J.RoseandW.Wohlleben,TransformationsofNanoenabledCopperFormulationsGovernRelease,AntifungalEffectiveness,andSustainabilitythroughouttheWoodProtectionLifecycle,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2018,52,1128-1138.

20. G.Cheloni,E.MartiandV.I.Slaveykova,InteractiveeffectsofcopperoxidenanoparticlesandlighttogreenalgaChlamydomonasreinhardtii,AquaticToxicology,2016,170,120-128.

21. N.Odzak,D.Kistler,R.BehraandL.Sigg,Dissolutionofmetalandmetaloxidenanoparticles inaqueousmedia,EnvironmentalPollution,2014,191,132-138.

22. S.K.Misra,A.Dybowska,D.Berhanu,M.N.Croteau,S.N.Luoma,A.R.BoccacciniandE.Valsami-Jones, IsotopicallyModifiedNanoparticlesforEnhancedDetectioninBioaccumulationStudies,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2012,46,1216-1222.

23. O.Bondarenko,A.Ivask,A.KäkinenandA.Kahru,Sub-toxiceffectsofCuOnanoparticlesonbacteria:Kinetics,roleofCuionsandpossiblemechanismsofaction,EnvironmentalPollution,2012,169,81-89.

24. M.J.B.Amorim,S.Lin,K.Schlich,J.M.Navas,A.Brunelli,N.Neubauer,K.Vilsmeier,A.L.Costa,A.Gondikas,T.Xia,L.Galbis,E.Badetti, A. Marcomini, D. Hristozov, F. v. d. Kammer, K. Hund-Rinke, J. J. Scott-Fordsmand, A. Nel and W. Wohlleben,EnvironmentalImpactsbyFragmentsReleasedfromNanoenabledProducts:AMultiassay,MultimaterialExplorationbytheSUNApproach,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2018,52,1514-1524.

25. M. Therezien, A. Thill and M. R. Wiesner, Importance of heterogeneous aggregation for NP fate in natural and engineeredsystems,ScienceofTheTotalEnvironment,2014,485-486,309-318.

26. Z.-L.Ren,M.Tella,M.N.Bravin,R.N.J.Comans,J.Dai,J.-M.Garnier,Y.Sivry,E.Doelsch,A.StraathofandM.F.Benedetti,Effectofdissolvedorganicmattercompositiononmetalspeciationinsoilsolutions,ChemicalGeology,2015,398,61-69.

27. I.Atanassova,CompetitiveEffectofCopper,Zinc,CadmiumandNickelon IonAdsorptionandDesorptionbySoilClays,Water,Air,andSoilPollution,1999,113,115-125.

28. E. Tombacz and M. Szekeres, Surface charge heterogeneity of kaolinite in aqueous suspension in comparison withmontmorillonite,AppliedClayScience,2006,34,105–124.

29. A.Thill,O.Zeyons,O.Spalla,F.Chauvat,J.Rose,M.AuffanandA.M.Flank,CytotoxicityofCeO2NanoparticlesforEscherichiacoli.Physico-ChemicalInsightoftheCytotoxicityMechanism,Environ.Sci.Technol.,2006,40,6151-6156.

30. W.Wohlleben,S.Brill,W.MeierMatthias,M.Mertler,G.Cox,S.Hirth,B.vonVacano,V.Strauss,S.Treumann,K.Wiench,L.Ma-Hock and R. Landsiedel, On the Lifecycle of Nanocomposites: Comparing Released Fragments and their In-Vivo Hazards fromThreeReleaseMechanismsandFourNanocomposites,Small,2011,7,2384-2395.

31. T. Hüffer, A. Praetorius, S. Wagner, F. von der Kammer and T. Hofmann, Microplastic Exposure Assessment in AquaticEnvironments: Learning from Similarities and Differences to Engineered Nanoparticles, Environmental Science & Technology,2017,51,2499-2507.

32. M.-N.Croteau,S.K.Misra,S.N.LuomaandE.Valsami-Jones,BioaccumulationandToxicityofCuONanoparticlesbyaFreshwaterInvertebrateafterWaterborneandDietborneExposures,EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2014,48,10929-10937.

33. P.-E.Buffet,M.Richard,F.Caupos,A.Vergnoux,H.Perrein-Ettajani,A.Luna-Acosta,F.Akcha,J.-C.Amiard,C.Amiard-Triquet,M.Guibbolini, C.Risso-DeFaverney,H. Thomas-Guyon,P.Reip,A.Dybowska,D.Berhanu, E.Valsami-Jones andC.Mouneyrac,AMesocosm Study of Fate and Effects of CuONanoparticles on Endobenthic Species (Scrobicularia plana,Hediste diversicolor),EnvironmentalScience&Technology,2012,47,1620-1628.

34. J. D. Jones, Aspects of respiration in Planorbis corneus L. and Lymnaea stagnalis L. (gastropoda: pulmonata), ComparativeBiochemistryandPhysiology,1961,4,1-29.

35. S.GroendahlandP.Fink,Highdietaryqualityofnon-toxiccyanobacteriaforabenthicgrazeranditsimplicationsforthecontrolofcyanobacterialbiofilms,BMCEcology,2017,17,20.

36. O. Bondarenko, K. Juganson, A. Ivask, K. Kasemets,M.Mortimer andA. Kahru, Toxicity of Ag, CuO and ZnOnanoparticles toselectedenvironmentallyrelevanttestorganismsandmammaliancellsinvitro:acriticalreview,ArchivesofToxicology,2013,87,1181-1200.

37. J. Rousk, K. Ackermann, S. F. Curling and D. L. Jones, Comparative Toxicity of Nanoparticulate CuO and ZnO to Soil BacterialCommunities,PLOSONE,2012,7,e34197.

38. M.Gutternigg,S.Bürgmayr,G.Pöltl, J.RudolfandE.Staudacher,NeutralN-glycanpatternsof thegastropods limaxmaximus,cepaeahortensis,planorbariuscorneus,ariantaarbustorumandachatinafulica,GlycoconjugateJournal,2007,24,475-489.