Environmental destruction as a counterinsurgency strategy in the Kurdistan region of Turkey

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

jacob-van-etten -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Environmental destruction as a counterinsurgency strategy in the Kurdistan region of Turkey

Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Geoforum

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate /geoforum

Environmental destruction as a counterinsurgency strategyin the Kurdistan region of Turkey

Jacob van Etten a,*, Joost Jongerden b,c, Hugo J. de Vos d, Annemarie Klaasse e, Esther C.E. van Hoeve f

a International Rice Research Institute, DAPO 7777, Metro Manila, Philippinesb Critical Technology Construction, Social Sciences, Wageningen University, Hollandseweg 1, 6706 KN Wageningen, The Netherlandsc Athena Institute, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlandsd Voswiz Consultancy,Talmastraat 12, 6706 DT Wageningen, The Netherlandse WaterWatch, Generaal Foulkesweg 28, 6703 BS Wageningen, The Netherlandsf RIONED Foundation, Postbus 133, 6710 BC Ede, The Netherlands

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:Received 9 March 2007Received in revised form 5 May 2008

Keywords:TurkeyTunceliPartiya Karkerên KurdistanTurkish Armed ForcesEnvironmentForestForest fireCounterinsurgencyArmed conflictGISRemote-sensing

0016-7185/$ - see front matter � 2008 Elsevier Ltd. Adoi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.05.001

* Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected] (J. van Etten)

We examine environmental aspects of the conflict between the Turkish state and the insurgent KurdistanWorkers Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan or PKK). Since the early 1990s, several civil society groups haveclaimed that the Turkish army burned forests and destroyed other livelihood resources in the Kurdistanregion of Turkey as it evacuated settlements. We report the results of a case study of destruction in Tun-celi, eastern Turkey, undertaken in order to evaluate support for such claims. We demonstrate the use ofgeospatial techniques in case-specific approaches to the study of armed conflict. Through the analysis ofsatellite images, we verified eyewitness reports and confirmed that substantial burnings did indeed takeplace in the study area between 1991 and 1994. We argue that this destruction was not irrational or wan-ton, but that it was part of a strategy used by the Turkish army in the early 1990s that aimed at activelytransforming the war environment.

� 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In this article we focus on the environmental aspects of thearmed conflict between the Turkish security forces and the Kurdis-tan Workers Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan or PKK). Much hasbeen written about the war between the Turkish state and thePKK (Imset, 1995; Barkey and Fuller, 1998; Yüce, 1999; White,2000; Özdag, 2003; Bozarslan, 2004; Jongerden, 2007). The envi-ronmental geography of the conflict, however, has been neglected.By paying attention to the environmental aspects of warfare from ageographical perspective, we contribute to a wider understandingof the conflict. We examine the claim that the burning of forestswas systematically practiced by the Turkish Armed Forces, as anintegral part of its overall strategy in a counterinsurgency cam-paign directed against the PKK. These claims are substantiated byan area case study.

ll rights reserved.

.

The neglect of the environmental aspects of war in southeasternTurkey corresponds to a wider trend in research. Except for thehighly visible war-related oil-spills of the Middle East, little sys-tematic research exists on the environmental impact of war,although it seems likely that contemporary war has a greater neg-ative impact on the natural environment than ever before in his-tory (Dudley et al., 2002). Assessments of the environmentalconsequences of armed conflict and their specific causes are com-plicated by several methodological obstacles (for an overview, seeBiswas, 2000). In spite of this difficulty, there is a modest recent in-crease in attention to wartime destruction of natural and liveli-hood resources (Baral and Heinen, 2005; Price, 2003; de Jonget al., 2007; Richards and Ruivenkamp, 1997; van Etten, 2004;Sperling, 1997, 2001, see also below in this section). Further meth-odological development in this field is much needed.

In this study we use geospatial methods to gain insight into theenvironmental geography of the armed conflict in southeasternTurkey. We believe that geospatial methods (including spatialanalysis, remote-sensing, and global positioning systems) havemuch potential to achieve methodological progress in conflictstudies. Until recently, spatial analysis in conflict studies was pri-

2 The case study (remote sensing, spatial analysis, focus group discussions) wascarried out by Esther van Hoeve and Annemarie Klaasse as a joint MSc thesis (vanHoeve and Klaasse, 2001). The research project was supported by the Chair GroupTechnology and Agrarian Development and the Centre for Geo-Information. Theacquisition of imagery was financed by the two involved groups. The researchersmade grateful use of the support of civil society organizations in data collection. Wewould also like to acknowledge Frans Rip of the WUR GeoDesk for supplying part ofthe data used for the elaboration of the maps in this article.

3 The approximate number of settlements depopulated and destroyed (about 3000)is not really in dispute, but the number of people affected has been a subject ofcontroversy. Human rights organizations and NGOs claim that Turkey has deliber-ately presented low numbers to camouflage the magnitude of the displacement. Someestimate the number of displaced persons to be as high as 3 million or even 4 million(Kurdish Human Rights Project, 2002). Other NGOs, however, such as the TurkishEconomic and Social Studies Foundation, TESEV (Türkiye Ekonomik ve Sosyal EtüdlerVakfı), consider the number of 3–4 million displaced persons to be a rather highestimate, and tend more towards 1.5 million (Aker et al., 2005:8). Research conductedby the Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies under the coordination ofthe Prime Ministry’s State Planning Organization, DPT (Devlet Planlama Tes�kilat), puts

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1787

marily associated with econometric comparisons of a large numberof countries or conflicts (‘large-N studies’) in conflict studies.1 Sev-eral scholars have tried to incorporate issues of geographical scaleand spatio-temporal dependence in econometric models (Gleditsch,1998; Buhaug and Lujala, 2005) and to create spatially disaggregateddatasets (Raleigh and Hegre, 2005). Large-N studies have attractedimportant criticisms, however (cf. Korf, 2006). Richards (2005) ar-gues that large-N studies, and several other approaches to armedconflict, tend to isolate conflicts from their historical social context.O’Lear (2005:300) makes a parallel case for the geography of armedconflict, arguing that ‘resources are often valued unproblematicallyas territorial features to be controlled without an adequate assess-ment of power relations, meanings, or historical contexts of resourcefeatures or how those features may be connected with other places’.

The authors cited propose an approach that is both more context-sensitive and case-specific. Richards (2005) advocates an ethno-graphic approach to account for the specific roots and dynamics ofcontemporary conflicts. Little can be taken at face value in conflictstudies, and familiarity with the particularities of the conflict stud-ied is needed to tease out the precise meaning of violent acts. Othershave countered, however, that the requirement of familiarity withthe region in conflict precludes the development of a sustainable re-search programme based on this approach. Fieldwork in war zonesnot only tends to be dangerous, but the very intimacy of researcherswith participants in the conflict is deemed problematic because itcan be used to taint research findings as partial (Buhaug, 2007).

It is clear, however, that geospatial methods are not exclusive tothe large-N comparative approach, nor incompatible with a case-specific approach. Indeed, they can be used specifically to addressthe supposedly weak points of the case-specific approach, thusenhancing the credibility, objectivity, and feasibility of studiesdone from this perspective. A small yet growing number of recentstudies show how geospatial methods can be used to study singlecountries, and areas within countries, in detail. Datasets on humanrights violations in single countries have been used in spatial andquantitative analyses (Ball, 2001; Steinberg et al., 2006;www.hrdag.org). Working on the conflicts in and around Colombia,Álvarez (2003) and Fjeldså et al. (2005) used GIS to juxtapose datafrom different sources to gain an impression of the spatial proxim-ities between the fighting factions and the natural resources of theregion. Others use remote-sensing and other geospatial techniquesin ongoing work, such as the Genocide Studies Programme at YaleUniversity (http://www.yale.edu/gsp) and the AAAS GeospatialTechnologies and Human Rights Project (http://shr.aaas.org/geo-tech; Prins, 2008).

In this article we explore further the potential contribution ofgeospatial methods to case-specific approaches in the study ofarmed conflicts. Working from a geospatial perspective, we inte-grated rather disparate types of data (geo-referenced data on hu-man rights violation claims, remote-sensing data, data obtainedfrom qualitative interviews, and demographic census data) in anevaluation of natural and livelihood resource destruction in easternTurkey. Our aim is not only to show the methodological viability ofgeospatial studies for the assessment of wartime resource destruc-tion but also to illustrate that this kind of study may produce spe-cific insights into the conflict itself. As this study will show,tracing the fate and meaning of resources during conflict – ratherthan assuming them as fixed ‘territorial features’ to be controlledor destroyed – will shed a distinctive light on the social context ofarmed conflict. We use the insights mentioned above, to substanti-ate our claim that resource destruction was a deliberate effect of thewar strategy that the Turkish army implemented in the early 1990s.

1 The large-N analyses were spurred by the consistent data collection efforts of theCorrelates of War Project and the Uppsala/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset.

In the next section we describe this change in war strategy andhow it fits in the wider social and political context of the conflict insoutheastern Turkey. We then introduce our case study of Tunceli,a province in the Kurdistan region of Turkey, for which we then de-scribe our methodology and discuss our findings.2 In the last sec-tion we draw conclusions from the case study and discuss thecontribution of geospatial methods to conflict studies.

2. Historical context

Since the early 1980s there has been an armed struggle in largeareas of eastern Turkey, between the Turkish state and the PKK. Inthe early 1990s this conflict began to take many lives. Reliable sta-tistics are not available, but the conflict may have caused as manyas 35,000 deaths. An estimated one to three million people weredisplaced as Turkish security forces systematically evacuated ordestroyed around 3000 villages.3 International human rights orga-nizations concluded at the time that a new phase in the war had be-gun. Repression has long been the response to problems in Turkey,but it was recognized that in the 1990s Turkish security forces hadstarted a full-scale ‘dirty war’ (Amnesty International, 1996). Theremainder of this section should serve the reader as a backgroundto these events.

The PKK is a political movement that arose from Kurdish andTurkish left-wing urban student environments, mainly in Ankara.For many young Kurds, violence was an attractive option becauseof the lack of alternative possibilities to negotiate their integrationinto the Turkish social and political system without completelyrenouncing their Kurdishness (Bozarslan, 2004; Barkey and Fuller,1998). The violence perpetrated by the PKK (and other organiza-tions formed in the same period) was rational-instrumental, inthe sense that it intended to change the social and political statusof the Kurds and Kurdistan (both Turkish Kurdistan and the widernational project including Iraqi and Iranian Kurdistan).

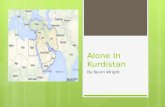

In spite of its urban derivation, the PKK was established as a polit-ical party in 1978 in Fis (Turkish: Ziyaret), a small village located innorthern Lice District of Diyarbakir Province, a mountainous areawhere government control was weak (Yüce, 1999) (see Fig. 1). Thischoice of a rural location for its foundation reveals an importantcharacteristic of the PKK, for, unlike most other illegal Kurdish andTurkish parties, which remained confined to the urban student envi-ronments in which they originated, the PKK established itself in thecountryside.4 Its distinctive political strategy was based on the ideathat it should not take over the state in a single great moment of

the number at between 950,000 and 1,200,000 (see Jongerden, 2007).4 A notable exception was the Workers Peasants Liberation Army of Turkey (Türkiye

_Is�çi Köylü Kurtulus� Ordusu), a communist organization which was mainly active in theprovince of Tunceli. However, the Turkish army began to concentrate on Tunceli onlyafter the PKK had moved into this area (see below).

Fig. 1. The conflict in southeastern Turkey.

1788 J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

change (as in the paradigmatic seizure of the tsar’s winter palace bythe Bolsheviks in 1917), but rather that it should build up counter-power and counter-institutions to eventually replace those of thestate (as in the paradigmatic establishment of the Soviet Republic ofChina by the Red Army under Mao in the early 1930s). This was bestto be organized in areas where the state was weak or absent, that is,in rural areas (Kocher, 2004; Jongerden, 2007).

In order to establish itself in the countryside, the PKK applied theprinciples of prolonged guerrilla warfare from 1984, concentratingin southeastern Turkey (Turkish Kurdistan). Guerrilla cells launchedincessant and widespread small-scale attacks on the Turkish ArmedForces. These attacks were intended to cause the armed forces totake up defensive positions in the larger settlements and aroundlines of communication and defence. This tactical withdrawal wouldrelease the rest of the countryside to the PKK. The guerrillas wouldthen build up forces in the countryside, liberate areas where theywould establish a parallel administration, and eventually deployconventional warfare techniques for their defence.

Until the first half of the 1990s, this strategy had considerablesuccess, as the Turkish army responded to the PKK attacks as ex-pected. The strategy of the Turkish army was informed by the Cold

War doctrine of a standing army statically defending territoryagainst a centrally organized and identifiable enemy, for example,an invading Soviet army. In response to the attacks of the PKK, thearmy garrisoned only towns and larger villages, leaving the smallervillages and hamlets unattended. The PKK was thus able to create asupportive rural environment composed of small settlements dis-persed over the region. The PKK gained considerable support frompeasants and agricultural workers. The rural settlements providedthe PKK with monetary resources (through taxation), shelter, re-cruits, logistics, and intelligence. Occasional army sweeps soughtto destroy the guerrillas, but these proved ineffective: as the troopsgot into position, the guerrillas merely slipped away, only to returnlater unnoticed when the army sweep had ended and the soldiersreturned to their barracks.

As its strength increased, the PKK planned to expand the areasunder its control, call for a popular uprising, and launch large-scaleattacks on Turkish positions. This final battle was to start when thepositions of the Turkish army had become untenable and its sol-diers overwhelmed and demoralized by the continuous attacks, re-signed to defeat. In 1993, the PKK announced the establishment ofa provisional parliament in Botan and called for a popular uprising

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1789

(see Fig. 1).5 However, the anticipated final battle never took place.Instead, the PKK was confronted with a sharp, ultimately decisivedeterioration of its supporting environment.

This turn in the course of the war had its roots in a major strategicchange on the part of the Turkish Armed Forces. In 1991, the Turkisharmy had announced that its new war strategy would follow a so-called field domination doctrine. This is a strategy designed to com-bat insurgency in a situation of asymmetric warfare (Tomes, 2004).6

The army had discovered that the PKK guerrillas could not be recog-nized by identity (individuals changed roles, between combatantand non-combatant) or confined to a place that was either static (highmobility was part of their strategy) or in some way central (insurgentstended to be organized in self-sustaining, spatially dispersed cells).Thus, the war against them, it was realized, could not be won by a sim-ple occupation of territory, the closure of areas to combatant move-ment, or the elimination of insurgent activity in a particular centralplace. The 1991 doctrine expressed the growing awareness that in thiswar ‘space’ was not a static entity of which one could have more orless. The Turkish army had to change its own deployment in space,and at the same time actively transform the physical and social land-scape to render it controllable.

The new war doctrine of 1991 was premised, among other things,on a restructuring of the Turkish army. The Armed Forces changedtheir relatively cumbersome divisional and regimental structure, in-tended to fight a war of position against a Soviet army, into a moreflexible corps and brigade structure. This allowed for a more rapidresponse and increased mobility, as required in an asymmetricwar of movement. The new doctrine implied a painstaking ‘clearand hold’ strategy in the territories infiltrated by PKK guerrillas,which was put into practice after 1993, when the reorganizationof the army had been completed (Özdag, 2003). The move fromthe previous strategy of ‘search and destroy’ (and then back to base)to one of ‘clear and hold’ was fundamental to the doctrine of fielddomination, and altered the whole course of the war. It also setthe scene for the environmental destruction that is our focus here.

A crucial, constituent part of the new strategy was the forma-tion of paramilitary village guards under the control of the army.In 1985, the government changed the Village Act in order to makeit possible to hire ‘Temporary and Voluntary Village Guards’ (Geçicive Gönüllü Köy Korucuları). This law change legally sanctioned thecreation of an irregular paramilitary force by the state. The TurkishArmed Forces effectively put into practice the institution of the vil-lage guard from 1987 onwards. Villages were expected to assignsufficient men to form a unit of village guards, which was armed,paid for, and supervised by the local gendarmerie. The villageguards were expected not only to take defensive positions againstthe PKK but also to participate in operations, some of which in-volved cross-border incursions into Northern Iraq. About 5000men joined this paramilitary force in its first year, and by 1995 thisnumber had swelled to 67,000. In 2003, the number of villageguards was almost 59,000 according to official figures (Jongerden,2007). Areas in which the take up of this program was low wereobviously more vulnerable to village evacuation and concomitantdestruction, which was the case in Tunceli (see below).

5 Botan (Bohtan, Bokhtan) is an area covering parts of northern Iraq and the Turkishprovinces of S�ırnak, Hakkari, Van, and Siirt.

6 International military advice likely played an important role in the adoption ofthis new doctrine. US specialists and Vietnam veterans instructed the special forces ofthe Turkish army in fighting the Kurdish insurgents (S�ahan and Balik, 2005), while USteaching materials were being used by the security forces (Bozarslan, 2004), whichadopted US approaches like studying guerrilla literature (see Pamukoglu, 2003;compare Halperin, 1974). In the past, Turkish counterinsurgency units had close tieswith the US army and the CIA (Deger, 1977; Roth and Taylan, 1981). The likelihoodthat such connections played an important role in formulating the new counterin-surgency strategy makes international comparisons especially relevant.

The introduction of the field domination doctrine meant achange in strategy concerning the counterinsurgency environment.The small rural settlements of eastern Turkey were now consideredimportant, as they provided a safe haven and power base for thePKK. The villages and their inhabitants furnished the PKK withmonetary resources (raised through taxation) as well as shelter, re-cruits, logistics, and intelligence. The forests in the immediate sur-roundings of the settlements provided cover and hide-outs. The‘clear and hold’ strategy required first and foremost that theseareas be cleared of whomever and whatever might offer supportand assistance to the enemy. Villages had been the targets of evac-uation and burning before 1991. However, at that time the armyhad thought of these actions solely as a means of reprisal for al-leged support of the PKK. After the implementation of the fielddomination doctrine in 1993, however, village evacuations andthe burning of buildings, crops, and forests started to become astructural element of the military strategy (Özdag, 2003; Jonger-den, 2007).

After 1994 some of the disastrous effects of the new strategybecame clear to the general public as the intensification of villageevacuation and destruction and the occurrence of forest fires ineastern Turkey began to receive attention in the media. In an inter-nationally published article, the Turkish writer Kemal (1995) ex-pressed his indignation and amazement about the fact that astate would burn its own forests just because guerrillas can hidein them. This publication led to the indictment and prosecutionof Kemal, which received considerable publicity. At the same time,civil society organizations and international and local humanrights organizations used eyewitness accounts to document howthe Turkish security forces were systematically evacuating villagesand destroying rural livelihoods by burning fields, forests, andother resources (Human Rights Watch, 1995; Stichting Neder-land-Koerdistan [Netherlands-Kurdistan Foundation], 1995; _InsanHakları Dernegi [Human Rights Foundation], 1996). From the num-bers derived from the human rights reports, it can be concludedthat village evacuation and destruction had risen to unprecedentedlevels in 1993 and 1994 (Table 1).

In spite of the public attention that forest burning and otherforms of livelihood destruction in southeastern Turkey have re-ceived, no systematic assessments of the destruction have beenundertaken. Resource destruction has been difficult to assess be-cause the areas where violations occurred were sealed off by thearmy, not only to civil society organizations attempting to obtainwitness accounts but also for high-ranking politicians, even includ-ing the Turkish prime minister (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan,1995). Moreover, evacuated inhabitants of the region tended todisperse geographically as they each made their own arrangementsto start afresh in life, further hindering comprehensive assess-ments. However, from the information available, it is clear thatthe burnings were no accident. The available witness accountsclearly indicate (1) the intentional nature of the forest burnings,(2) the active role of the Turkish state in causing the fires, and(3) their massive proportions (Box 1).

Box 1 Sample of witness accounts‘‘Twenty-four-year-old C.V. told Human Rights Watch that,

during the spring of 1994, helicopters were frequently used toburn down the forests surrounding Yaziören, a small village ofthirty homes. ‘They poured gasoline or some kind of flamma-ble liquid over the trees’, he said, ‘and then set the trees afire’.C.V. said the Jandarma [Gendarmerie] ordered villagers not toenter into the forests, which were declared free-fire zones”(Human Rights Watch, 1995:97).

‘‘[E]very now and then I went from Dersim, where I at-tended school, to Ovacık, to help my father in the drugstore.[. . .] They burn the forests [. . .] we were walking betweenburning forests. At both sides of the Munzur River the forestswere burning. That was two years ago, in 1994, at the timethe military burned down Ovacık. Because of the smoke, fly-ing insects came to Dersim [Tunceli] City. Everywhere in thecity were insects. Although the weather was good those dayswe could not see the sun because of the smoke. [. . .] Every-where was darkness.” (Jongerden et al., 1997:53).

1790 J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

3. Case study: Tunceli province

Through a case study we evaluated further the claim of massive,intentional resource destruction and examined the particular pat-tern of destruction for one part of eastern Turkey, the province ofTunceli. This area was chosen because eyewitness informationwas available indicating that Tunceli suffered large-scale, system-atic evacuation of villages and intentional burning of forests andother resources brought about by the Turkish army between1993 and 1994 (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995).

The province of Tunceli is situated in the eastern Anatolian re-gion of Turkey and covers approximately 7600 km2 (Fig. 1). Thisstudy area is part of the basin of the Munzur, one of the main trib-utaries of the Euphrates. The Munzur Mountains are rugged, withdeep valleys and high peaks that range in altitude from 950 to3463 masl. The area has a continental climate with dry summers(annual precipitation 550–1100 mm/year). Forests cover 27% ofthe territory of Tunceli (some 2100 km2), whereas 61% of the forestcoverage has a protected status.7 The protected area contains theUNESCO Munzur Valley National Park, 8 km north of Tunceli, with428 km2 of vegetation. Deciduous forests are found mostly in Tun-celi, Ovacık, Pülümür, Hozat, and Nazimiye. Pine forests predomi-nate in the north, above 1800 masl.

The province of Tunceli was created in 1937 after the bloodysuppression of a separatist uprising, the most important rebellionin the history of the Turkish Republic. Before 1937, the current ter-ritory pertained to the province Dersim (Zazaki: Dêsim, Kurdish:Dêrsim). In the north, parts of Dersim became part of ErzincanProvince. In the east and south, parts of Dersim were incorporatedby Bingöl and Elazıg provinces. The main part of Dersim (Persian,Kurdish, Zazaki: ‘silver door’) was renamed Tunceli (Turkish:‘bronze hand’). Today, in common language, the name Dersim isused as a synonym for Tunceli. This use of the name Dersim makesallusions to these past events to express political opposition to theTurkish state.

In 1990, the total population of Tunceli was 133,585(17.6 inhabitants/km2), of which 62% lived in rural areas. The mainagricultural activities in the area are animal husbandry and farm-ing. In the province and adjacent areas, Zazaki (Dersim) is the ma-jor language. The Zaza are an Iranic (Aryan) ethnic group, culturallyand ethnically related to the Kurds. Most inhabitants adhere to theAlevi religion, a (liberal) variant of Shi’ite Islam. In Tunceli, the onlyprovince in Turkey with an Alevi majority, being an Alevi is animportant aspect of the identity of the people, even though Alev-i-ness is often uncoupled from religion per se. Since Alevi reli-gion/identity crosscuts ethnic boundaries (having both Turkishand Kurdish/Zaza adherents), it is the object of complex identitypolitics.

Initially, PKK guerrilla activity in Tunceli was low-profile. PKKguerrilla activities were concentrated (south)east of Tunceli. How-

7 Figures found at www.tunceli.gov.tr (accessed November 26, 2007).

ever, in reaction to the implementation of the environment depri-vation strategy by the Turkish Armed Forces in the early 1990s, thePKK attempted to expand its area of movement westwards (to Tun-celi and Sivas) and northwards (towards the Black Sea coast). Withthe PKK trying to develop a habitat for its militants in Tunceli, thearmy strategy, conversely, was to destroy it (Jongerden, 2007).

One strategy of the Turkish army to contain guerrilla activitywas to limit the mobility of the civilian population (Firat, 1997).This could take the form of curfews and a ban on entering summerpastures. The measures taken included limitations on herding cat-tle and sheep, an important economic activity in the area. Theauthorities also implemented a prohibition on trade in food andother provisions without explicit authorization (Stichting Neder-land-Koerdistan, 1995). The provision of medicines became totallycontrolled by the army.

In 2003, when there were close to 60,000 village guards on thestate payroll, a mere 386 were to be found in Tunceli (Jongerden,2007). In 1994, at the height of the Turkish army campaign aimedat the degradation of potential PKK rural resources, almost no vil-lage guards were recruited in the province (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995). As indicated above, this left the area particularlyvulnerable to environmental destruction. In reference to villagedestruction and forest burning and the presence of village guardsin Tunceli, it was written that

‘‘The southern part of the province suffered much less in theoperations. The districts of Çemis�gezek and Pertek are ethni-cally somewhat mixed and are culturally speaking not con-sidered as part of Dersim [Tunceli] proper. In both there isat least one village with korucu, ‘village guards’, which isexceptional in this province. There appear not even to havebeen any attempts to recruit village guards elsewhere inTunceli, possibly because of the Dersimis’ reputation forrebelliousness” (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995:20).

The military started a wave of operations in 1994, which in-cluded forest fires starting in July and August and continuing forseveral months, as well as village evacuations in the autumn of1994 (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995). Table 2 gives abreakdown of village and forest destruction in 1994 for the prov-ince of Tunceli. A ‘well-informed’ Turkish politician with ‘closerelations to the region’ claims that 25% of the forests were de-stroyed by fire during this period (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan,1995:21).

Official population data (Table 3) are useful in establishing thecase of village evacuation in Tunceli because these data can hardlybe considered as tainted by attempts to make population changeappear less dramatic. Table 3 clearly shows an enormous popula-tion decrease in the rural areas of the whole province between1990 and 2000, the total number of people living in the Tuncelicountryside falling by a little over half. Urban population, on theother hand, rose a little on average, in some places rising signifi-cantly. We interpret this as an overall tendency of forced urbaniza-tion. Rural inhabitants established themselves in urban areasrelatively close to their original community – or else they decidedto move to cities outside Tunceli, either in the west (for example,Ankara and Istanbul) or in the south (for example, Adana and Mer-sin) (Jongerden, 2007).

In Tunceli City and the outlying towns, the displaced were leftto their own devices. Plans were made to resettle rural populationsin urban-type settlements both near cities and in the countryside(Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995). However, most of theseplans were never funded and when they were realized they arrivedonly after village destruction had already forced the rural popula-tion to leave the countryside and establish itself in urban areas(Jongerden, 2007). In Tunceli Province, only one scheme ever mate-rialized, the so-called ‘Afet Evleri – Kandolar Mahallesi’ (‘Disaster

Table 2Number of villages evacuated and burned during the autumn 1994 army operationsin Tunceli Province

District Subdistrict Totalvillages

Evacuated Burned Totalaffected

Affected(%)

Tunceli Central 15 7 3 8 53Çicekli 11 1 0 1 9Kocakoç 11 3 3 4 36Sütlücü 11 8 4 9 82Çemis�gezek 16 2 1 3 19Akçapinar 9 1 1 2 22Gedikler 14 0 0 0 0

Hozat Central 29 15 10 18 62Çaglarca 7 4 1 4 57

Mazgirt Central 26 3 0 3 12Akpazar 21 0 0 0 0Darikent 31 6 2 7 23Nazimiye 12 4 3 4 33Büyükyurt 12 2 2 2 17Dallibahçe 6 4 3 4 67

Ovacık Central 45 26 18 37 82Karaoglan 6 3 5 6 100Yes�ilyazi 14 5 3 7 50Pertek 9 0 0 0 0Akdemir 8 0 0 0 0Dere 10 0 0 0 0Pinarlar 17 0 0 0 0

Pülümür Central 10 0 0 0 0Balpayam 7 0 1 1 14Dagyolu 12 5 0 5 42Kirmiziköprü 25 10 4 11 44Ûçdam 5 1 0 1 20

Total 399 110 64 137 34

Source: Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan (1995:63).

Table 1Number of evacuated and burned villages, 1991–2001, calculated on the basis of human rights reports

Year

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Number 109 295 874 1,531 243 68 23 30 30 0 3

Source: Jongerden (2007:82).

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1791

Houses, Kandolar Quarter’), built at the outskirts of the districttown of Ovacık. This scheme comprised only 80 barracks, whichis rather insignificant in comparison to the total number of dis-placed. The halving of the rural population in Tunceli Province dur-ing the 1990s amounted to some 40,000 people, whereas in Ovacıkalone the reduction was around 9000 people (Table 3).

Comparing the population census data with recorded villageevacuation figures afforded by the eyewitness (human rights) data-set reveals that the rural exodus systematically exceeds the per-centage of recorded evacuations.8 This indicates that a substantialpart of the village evacuations may not have been included in thedataset used here. This has important implications for our casestudy, as it is likely that the eyewitnesses underreport actual evacu-ations, and in all likelihood the same applies for resourcedestruction.

An additional source of statistical data which may give an indi-cation of the impact of army destruction of local resources is a re-port published by the Platform of Unions in Tunceli (TunceliSendikalar Platformu, 1996). This report indicates that between1990 and 1995 the area of annual crops and number of fruit treesdeclined by about a quarter (Tables 4 and 5), whereas the size ofherds decreased by more than a half (Table 6). According to thesame source, forest management activities such as monitoring, treeplanting, and controlled cuttings were postponed because of thevillage evacuations. The local population was forbidden to go intothe burned and burning areas because of the continuing opera-tions. On the other hand, security forces distributed illegal cuttingpermits. Also, officials did not take any action in stopping the forestfires in this area.

As already stated, Tunceli was difficult to visit during and di-rectly after the events described here. We have been unable to ver-ify claims of human rights violations with direct observations onthe ground. This makes a methodology based on remote-sensingan appropriate choice to further confirm and examine the destruc-tion by fire of forests and other land in this area. The eyewitnessaccounts and information derived from statistical sources abovecan be validated by using remote-sensing images. The use of firein destructive actions makes remote-sensing an even more appro-priate method, as burned areas are easily identifiable on satelliteimages.

In most cases, remote-sensing cannot be used to directly estab-lish that forest fires were lit by particular persons with particularmotives. In our case, establishing the presence of burned areas isnot sufficient to hold the Turkish army responsible; other causesof fire could be supposed for any observed burned areas. In Turkeyas a whole, forest fires frequently originate as agricultural firesescaping human control (Bilgili, 2001; Kurtulmuslu and Yazıcı,2003). However, it is important to note that, in Tunceli, fire wasseldom used and was certainly not standard agricultural practice,as stated by two agricultural experts familiar with the area whomwe interviewed. Thus, if widespread burned areas are found in thesatellite images after 1993–94, it is unlikely that the rural popula-tion had inadvertently caused the fires as a result of common land-management practices.

8 The comparison assumes that the average population size of evacuated and non-evacuated villages is roughly equal.

Based on the information presented in this section, we can de-velop several provisional hypotheses to be tested with remote-sensing data. If witness reports were accurate as to the presenceand extent of burned forests (and other areas), evidence of thiswould be clearly visible on satellite images. Also, general patternsof observations should show some degree of geographical (loca-tional) agreement with direct observations. We would also expectreported herd reductions and limited access to certain grazingareas to be reflected in a gradual conversion of grasslands intobush after 1993–94. At the same time, overgrazing and land degra-dation may have occurred because herds concentrate in certainareas as others become inaccessible due to conflict (cf. Jetten andde Vos, 1994, for Nicaragua). Finally, we can assess the statementthat fire is rarely used for agricultural purposes in the area byexamining images from before 1993–94 for evidence of burnedareas.

4. Remote-sensing and spatial analysis methodology

Two Landsat-5 Thematic Mapper images were selected so as toenable comparison of pre- and post-conflict forest coverage. Thespatial resolution of these images is 30 � 30 m (the pixel size). Thefirst image was taken in August 1990 and represents the situationjust before the change in strategy by the army (1991). The second

Table 4Reduction in (annual) area of crop cultivation (ha) in Tunceli, 1990–95

Crop 1990 1995 Reduction (%)

Wheat 35,282 28,000 21Barley 11,837 9000 24Lentils 21,300 15,000 30Chickpeas 4485 2710 40Beans 610 520 15

Total 73,514 55,230 25

Source: Tunceli Sendikalar Platformu (1996).

Table 5Reduction in number of fruit trees in Tunceli, 1990–95

Tree 1990 1995 Reduction (%)

Pear 86,180 66,713 23Quince 18,150 5330 71Prune 16,115 13,830 14Apple 69,250 56,980 18Apricot 25,500 20,470 20Cherry 20,260 16,660 18Peach 3640 3190 12Sour cherry 14,860 12,060 19

Total 253,955 195,233 23

Source: Tunceli Sendikalar Platformu (1996).

Table 6Reduction in herd size (number of animals) in Tunceli, 1990–95

Animal 1990 1995 Reduction (%)

Sheep 453,500 192,531 58Goats 226,236 75,512 67Cattle 71,871 34,950 51

Source: Tunceli Sendikalar Platformu (1996).

Table 3Population change in Tunceli, 1990–2000, compared with village evacuations

District Population, 1990 Population, 2000 Population change (%), 1990–2000 Evacuated villages (%)

Total Urban Rural Total Urban Rural Total Urban Rural

Tunceli 38,013 24,513 13,500 30,323 25,041 5282 �20 2 �61 31Çemis�gezek 12,559 3397 9162 9773 3685 6088 �22 8 �34 n.a.Hozat 11,643 4606 7037 9143 6589 2554 �21 43 �64 61Mazgirt 21,041 3751 17,290 12,957 2707 10,250 �38 �28 �41 19Nazımiye 7392 2401 4991 5604 2915 2689 �24 21 �46 n.a.Ovacık 15,316 3647 11,669 8522 5909 2613 �44 62 �78 46Pertek 18,475 5428 13,047 13,199 5737 7462 �29 6 �43 n.a.Pülümür 9145 3056 6089 4063 1893 2170 �56 �38 �64 31Total 133,584 50,799 82,785 93,584 54,476 39,108 �30 7 �53 34

Source: State Statistics Institute (1990, 2000) and Table 2 of this article (last column).

9 A hometown association regroups migrants from the same place (sharedgeographical origins), and involves mutual assistance and cultural solidarity (Hersantand Tourmarkine, 2005; Çelik, 2005). Turkish hometown associations were estab-lished in the Netherlands and other countries of western Europe, following theimmigration of Turkish workers.

10 Pre-processing of the images comprised image-to-image geometric correction,radiometric correction, and image-to-image radiometric normalization (van Hoeveand Klaasse, 2001).

1792 J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

image was taken in October 1994, representing the situation justafter reported forest fires in the summer of 1994 (Stichting Neder-land-Koerdistan, 1995). For this study, the north-eastern section ofboth images was used, covering around 95% of Tunceli Province(Figs. 2 and 3 show the analyzed section of the images).

Interpretation of satellite images requires assigning pixels of theimage to land-use classes on the basis of their spectral profiles. Un-der normal fieldwork conditions, direct observations on land-usedata for several locations are made before image processing. Onepart of these geo-referenced land-use observations is employed to‘train’ the classification software with reference to a particular im-age. This parameterizes the classification algorithm used to producea classified image. Another part of the field data (observations onland-use for other locations) is then used to assess the accuracy of

the classified image. The use of field reference data in satellite imageclassification is also referred to as ‘ground truthing’. Clearly, giventhe access problems in the investigated area, this method couldnot be used in the present study. Satellite imagery interpretationwas therefore performed with alternative ‘ground truth’ informa-tion, that is, qualitative data retrieved from various other sources.The advantage of focusing the study on burned areas is that theseare generally easily identifiable because of their particular spectralprofile, which is very distinct from other types of land cover.

We also attempted to distinguish other classes of land cover,specifically in order to test our hypothesis of simultaneous conver-sion of grassland into bush and land degradation closer to villagesdue to restrictions on herd movement. From a combination of dif-ferent types of data, an overall impression of the study area and de-tailed knowledge of sections of the landscape could be gained.

Discussions with people from the area were instrumental inthis. A Dersim hometown association in the Netherlands was con-tacted with the assistance of an anthropologist.9 We held three fo-cus group sessions with four members of the association. Thepersons interviewed migrated from Turkey to the Netherlands inthe 1980s. The specific knowledge of the contacted group includesthe cultural, historical, and political aspects of the Dersim commu-nity in and around Tunceli. They keep close contact with Tunceli;one of the informants visited the area in 1996, 1998, and 2001. Topo-graphical maps and printouts of the satellite images described wereused to facilitate discussions about land-use in the area. The partic-ipants contributed with their own visual materials, further enrichingthe discussion. Photographs of areas showed bare soil, rocks, debrisflow, riversides, rivers and streams, and forests and helped to inter-pret the images.

Also, reports and video footage of the area were gathered andinterpreted. Information from a mining company helped to inter-pret limestone and flysch-sedimentary rock formations in theimages (Tunceli and Kopdag Project). The presence of recognizableagricultural field patterns in the images helped to establish thisland cover class.

Classification of selected areas based on the available informa-tion (Table 7) then gave spectral profiles for land-use classes thatcould be used to classify the whole image employing supervisedclassification, using ERDAS 8.4.10 The identified areas consist ofthe major land cover types identified in both images, the cloudsand shadow seen on the second image of October 1994, and the

Fig. 2. Forests and villages included in the study (approximate administrative borders in gray).

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1793

burned areas. A further distinction was made between areas thatwere assumed to be burned forests and those assumed to be burnedareas with other uses. Spectral profiles for land-use types andburned areas were verified with those retrieved from the literature(Chuvieco, 1999) and proved to be nearly identical, thereby validat-ing our procedures and results.

This method of image classification gave reliable results just forbroadly defined land-use types. It was impossible, for instance, todistinguish in a reliable way among mixed landscapes of sparseforest vegetation, brush with trees, and grazing areas. With imageswith a better spatial or temporal resolution and better field data,finer distinctions could possibly have been made, although it must

be noted that conventional studies often suffer from similar classi-fication problems.

The classified image of 1994 was used to establish the size ofthe burned areas. By comparing the images, the land-use categoryin the 1990 image of areas that appeared as burned in the 1994image was established. This enabled a distinction betweenburned forest and burned non-forest. This distinction is useful be-cause of the salience of forest fires in the witness accounts. Forestfires were separately reported and codified in the data used inthis study.

GIS software ArcInfo 7/8 was used to compare the remote-sensing data with the data from the report by Stichting

Fig. 3. Burned forest and other burned areas in Tunceli, 1994.

1794 J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

Nederland-Koerdistan (1995). The latter data were geo-referencedby linking them to the locations of the villages they referred to.Obtaining the coordinates of these villages, however, proved moredifficult than expected. After having spent considerable effort onfinding cartographic data, we were able to obtain a detailedRussian topographical map, scale 1:100.000.11 As we were unableto determine the projection employed for this map, we preferredto digitize the villages directly on the geo-referenced images.

11 Joint Stock Company SK-IMPEX Moscow, Russia Glavnoe Upralenie Geodezii iKartografii pri Sovete Ministrov SSSR, Sheets J-37-18, J-37-19, J-37-20, J-37-30, J-37-31,J-37-32, J-37-42, J-37-43, J-37-44. Scale 1:100,000. 1970–94.

Locations of the settlements were determined on the satellite imageusing topographical and geomorphological characteristics, as well ascolour indications on the satellite image. A sample of 143 villageswas included in this study. This number included 30 villages notmentioned in the Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan report but clearlyvisible on the satellite image and present on the topographicalmap. Of the remaining 113 villages, 53 were listed in the report ashaving escaped both forest fire and home destruction; in 40 cases,fire was reported, and, in 20, home destruction.

The forest fires identified on the satellite images were com-pared with incidences described in the Stichting Nederland-Koerd-istan report. The eyewitness reports were analyzed distinguishing

Table 7Training area classes and their size (number of pixels) for the two satellite images

Class description 1990 1994

Forest 67,096 9616Debris flow 33,921 33,921Water 204,327 204,327Rock or bare soila 115,925 54,136Urban area or bare soilb 437,547 61,141Field type a (fallow?) 7221 5821Field type b (fallow?) 2083 5151Field type c (grassland) 8034 20,657Riverside 7590 7994Sparse vegetation 29,394 30,879Cloud – 22,896Shadow – 9444‘‘Heavily” burned (probably forest) – 2739‘‘Slightly” burned (probably non-forest) – 2153

a Visible as blue on a false colour RGB-743 image.b Visible as pink on a false colour RGB-743 image.

14 Observations of the absence of human rights violations and/or data on theobservation frame (e.g., the presence/absence/trajectory of observers in time andspace) may prove useful to avoid this problem in the future and assist in the fullerexploitation of geospatial approaches in this domain. Compare with note 16.

15 If village-level data on ethnic composition were to become available in the future,this issue could be analyzed in more detail (ethnicity is absent in official Turkish

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1795

villages with (1) recorded forest fires and (2) home destruction. Toassess the presence of forest fires around a village, the study de-fined a village as having burned forest when the satellite imageshowed within a 1.2 km radius from the centre of the village (a cir-cle of 452 ha) a minimum of 4.5 ha (1%) of burned forest. This is areasonable method, given that the human rights data include onlyforest fires in the direct vicinity of villages (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995).

5. Case study findings

The procedure used classified 10.3% of the surface of the entirestudy area as forest in both 1990 and 1994 (Table 8).12 In the imageof 1990, no burned areas were observed. This is additional evidenceshowing that under normal conditions the use of fire was rare in thearea. In 1994, however, around 0.8% of the study area was occupiedby burned forest (forest in 1990, ‘heavily’ burned in 1994). This im-plies that 7.5% of all forests (approximately 110 km2) were burned inthe period prior to October 1994.13 The above-mentioned estimateof a Turkish politician that 25% of the forests were burned shouldbe considered on the high side, if it is interpreted as making refer-ence to the whole territory of Tunceli. Interestingly, however,26.6% of the forests that were located within the 1.2 km radiusaround villages were classified as burned. Thus, for those forestsmost relevant to local livelihoods, the 25% estimate would beremarkably accurate.

More burned non-forest than burned forest areas were found,the former amounting to 520 km2. Burned non-forest areas wereespecially common near areas of burned forest, suggesting com-mon causality (Figs. 2 and 3). Occurrence of fires in non-forestareas could be ascribed to destruction of harvests and orchards.Certainly, witnesses report harvest and orchard burning from thetime, whereas the documentation of a decrease in orchards in Tun-celi in this period has been referred to above (Table 5).

Villages for which reports of burnings and other forms ofdestruction were available showed relatively more burned forestareas than those for which these were not reported or those vil-lages for which no information was available (villages in categoriesA and B versus those in C and D, Table 9). On the basis of this, it canbe concluded that the overall geographical pattern of resourcedestruction implied in the eyewitness accounts is confirmed by

12 Figures are for the whole intersection of the two images.13 A tiny fraction (0.04%) of the image was ‘‘slightly” burned forest. This was

expected to have been non-forest in the 1990 image on the basis of the spectralprofile in the 1994 image (Table 6). In the subsequent analysis, it was included as afraction of the burned area of non-forest land use.

the remote-sensing data. That many burned forest areas werefound in the areas for which no forest fires were reported indicatesthat the data contain a considerable degree of uncertainty. Ofcourse, any absence of observations of this phenomenon offers lit-tle to no evidence of the absence of the phenomenon itself. Lack ofevidence is not negative evidence; reasoning ex silencio is not validhere. Primarily, the discrepancy between forest fires as reported inthe literature and as detected with remote-sensing seems just topoint to areas of information lacking in the witness reports. Thecomparison of human rights report data of village evacuationsand official census population data above also showed that the hu-man rights dataset tends to be incomplete.14 A second possible rea-son for uncertainty, other than that of human rights datasetomissions, is that the geographical references may contain errorsdue to the ambiguity in village naming in the region. Many placeshave the same names, and all villages have at least two names: amodern name and a traditional name of Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish,or Zaza origin (Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995).

For three districts (Çemis�gezek, Nazımiye, and Pertek), humanrights data were indeed completely lacking, although migrationout of all these districts was strong (Table 3). The remote-sensingdata indicate that the effects of counterinsurgency in Nazımiye,in the northern half of the province, have been far more severethan in the other two districts, located in the south. This confirmsthe statement of Stichting Koerdistan-Nederland (quoted above)that the northern districts were more affected than the southerndistricts, which awaited full confirmation due to a lack of eyewit-ness observations for several districts. The north–south contrastis also evident in the outmigration rates, which are the lowestfor the southern districts.15 Taken as a whole, this evidence doessuggest that the overall levels of violence and destruction differedbetween the north and the south of the province. The northern dis-tricts have a more distinctive Alevi and Kurdish identity, whereas, inthe southern ones (Cemis�gezek and Pertek), a proportion of the pop-ulation is Sunni and considers itself Turkish. The presence of largeforests in the north may have also played a role.

Most, although by no means all, cases of reported fires accord-ing to eyewitness accounts were confirmed by satellite image(60%; category A in Table 9). The surprisingly high number of re-ported forest fires that could not be confirmed (40%) may refer toforests outside the 1.2 km radius around the village for which fireswere reported, or to forest fires affecting less than 4.5 ha. Althoughthe fires in the eyewitness data should refer to fires in the vicinityof villages only, the reported location of fires may be inaccuratewhen the observation was from a distance and especially whenonly smoke was observed and the fire hidden from view, a likelysituation in the mountainous landscapes of Tunceli. Another possi-bility is that a number of fires occurred not in the vicinity of thecentral villages, but around hamlets within their territory.16

Equally, the criterion that at least 4.5 ha of land in its vicinity shouldbe burned to count a village as having burned forest in the area isobviously not a stipulation expected of witness observations. This

documentation, such as census records and passport/ID card details).16 In the future, it might be advisable for human rights agencies to not only codify

these claims, but also data on the observations on the basis of which a particularclaim is made (type of observation, time, and location). This would enable GISmethods to be used in order to assess the accuracy of observations according to thetype of observation (based on smoke only, etc.) and the visibility of the observed areain relation to the location of the observation.

Table 9Comparison of eyewitness reports with satellite image classification results

Village category Totalnumber ofvillages inthiscategorya

Number of villageswithin each categorywith burned forestaccording to the satelliteimageryb

A. Forest fire (with or without otherforms of village destruction) wasreported for the immediatevicinity of the village

40 24 (60%)

B. Home destruction but no forest firewas reported for the village

20 17 (85%)

C. Eyewitnesses had knowledge aboutthe evacuation of the village, butdid not mention an observation offire or other forms of destruction

53 22 (42%)

D. The village was not mentioned byeyewitnesses, so no data thateither confirm or deny fire ordestruction

30 8 (27%)

a From Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan (1995) for a total of 143 villages.b Defined as >4.5 ha of burned forest within 1.2 km of village centre.

Table 8Land cover classification results for the analyzed section of the satellite image

Land cover 1000 ha %

Forest in both 1990 and 1994 141 10.3Forest in 1990, heavily burned in 1994 11 0.8Other land-use in 1990, slightly or heavily burned in 1994 52 3.8Clouds and shadows in 1994 77 5.6Other 1087 79.4

Total 1369 100.0

1796 J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797

kind of consideration might be relevant to, for example, a failed orprematurely curtailed burning.

As many as 85% of the villages that were reported as having suf-fered destruction but not forest burning did, in fact, suffer forestfires, according to the results presented here (category B in Table9). This suggests that home destruction almost always went handin hand with burning of forests (as well as orchards and fields)around the village, even if these fires were not reported. It is strik-ing that this percentage is even higher than that of accurate obser-vations of forest fire alone (category A in Table 9). Indeed, given themethodology used, home destruction (without observation of for-est fire) is found to be a more reliable indicator of forest fires thanthe positive affirmation of such. This remarkable finding may bepartly due to the different degrees of spatial uncertainty involvedin the different kinds of witness observations. Village destructionalways refers to a neatly circumscribed space, but recorded fieldobservations of forest fire may be of less spatial accuracy or spec-ificity, as indicated above.

It still needs to be explained, however, why forest fires, whichthe satellite image-based evidence shows to have taken place inmost of the evacuated villages (54% of the villages in categories Band C in Table 9 taken together), were not reported by eyewit-nesses in most of these villages, although they were able to observeother violent actions. One explanation could be that fires were litafter the evacuation was completed. Villagers did not see the burn-ing simply because they were not there; at the time of burning, fewpersons or only security personnel were left to observe events onthe ground. This may have been a planned effect of a deliberatestrategy of concealment, as the military would probably prefer tohide the true extent of its pyrogenic activities.

Finally, qualitative comparisons of the two images indicate anincrease in areas with grasslands, sparse vegetation, and shrubs.This is suggestive of land that was affected by destruction early

in the investigated period and is now in regeneration, or else ofan effect of the decreased use of grasslands (because the land-usershave migrated perhaps, or because access to the land was deniedby security forces). With the methods employed in this study, wecould not clearly establish land degradation closer to villages, an-other hypothesized effect of the limitations on herd movements.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Our analysis has shown that the eyewitness accounts and theremote-sensing data display the same broad spatial pattern, buthas also revealed that the observations on the ground suffer partic-ular limitations in space and time. More intensive observation inareas close to settlements led to overestimation of the total area af-fected by forest burning, whereas the absence of observations aftervillage evacuations probably led to an under-reporting of the num-ber of villages affected by forest fire. Likewise, comparisons of hu-man rights report data with official population data suggested anunderestimation of village evacuations in the eyewitness data.The population and remote-sensing data provide additional evi-dence for certain areas for which ground observation data arescarce, and allow for confirmation of the differences in the inten-sity of destruction between the northern and southern parts ofthe study area. Juxtaposing various types of data in a spatial frame-work allowed for an improved assessment of the impact of vio-lence and destruction.

The case study for Tunceli thus provided conclusive evidence toconfirm the claim of substantial resource destruction. The destruc-tion documented in this study involved a considerable loss of eco-logical values in the area, including forests that enjoy internationalprotection status, and deprived a large population of importantlivelihood resources while forcing the people to leave. The eco-nomic impact of these incisive changes was probably not limitedto rural areas, but extended to urban areas, which were deprivedof significant portions of their economic hinterland, and which insome cases had to absorb impoverished rural populations.

The two findings, (1) that the proportion of burned forest areaswas higher around settlements than in unpopulated areas and (2)that village evacuation was often accompanied by forest burning,provide additional evidence for our interpretation of the army’sstrategic change in the early 1990s. We have argued that the armysought to actively transform the space of war, driving a wedge be-tween the rural population and the PKK combatants. In the early1990s and before, PKK fighters hid especially in the forests closeto settlements, where they could obtain various resources fromthe villages and at the same time enjoy the protection of forest cov-er. Retrospectively, it is clear that the new military strategy indeedachieved the desired effect. After the village evacuation and re-source destruction of the first half of the 1990s, guerrilla cells wereforced to live in uninhabited areas and to develop more survivalistlivelihoods (Pamukoglu, 2003). The burned forests around ruralsettlements are thus a very clear, tangible expression of this sepa-ration of social spaces.

The study illustrates that geospatial data and tools can increasethe objectivity of case-specific studies of armed conflict. Satelliteimages provided an objective and accurate way to determine thevisible impact of military intervention in the area. Different data-sets could be linked and compared in sensible ways within a spa-tial framework using GIS. The approach followed may providehuman rights activists with new tools to verify witness accountsas well as opportunities to form partnerships with academicresearchers to make assessments of wartime resource destruction(de Vos et al., 2008, see also http://shr.aaas.org/geotech). In conflictstudies, the geospatial approach followed may have true comple-mentary value to ethnographic fieldwork. We have not only pro-duced a more accurate quantification of resource destruction

J. van Etten et al. / Geoforum 39 (2008) 1786–1797 1797

than possible on the ground but also provided further support forspecific aspects of our interpretation of the conflict. In work onland-use change, it has been found that remote-sensing data mayeven surprise ethnographers with a long-standing relation to a cer-tain area (Guyer and Lambin, 1993). Where and when possible, acombination of geospatial analysis and detailed fieldwork shouldbe attempted, as this could produce the strongest results in thesearch for knowledge about (disputed) wartime events (cf. Turner,2003). However, for situations in which this is not possible, thestudy has shown that detailed data on the effects of actions duringarmed conflict can be produced and analyzed without one havingbeen physically present in the area under study. Geospatial dataand tools thus strengthen the case-specific approach as a viableway forward in conflict studies.

References

Aker, A.T., Çelik, B., Kurban, D., Ünalan, T., Yükseker, D., 2005. The Problem ofInternal Displacement in Turkey: Assessment and Policy Proposals. TESEV,Istanbul.

Álvarez, M.D., 2003. Forests in the time of violence: conservation implications of theColombian war. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 16 (3/4), 47–68.

Amnesty International, 1996. No Security without Human Rights. AmnestyInternational, London.

Ball, P., 2001. Making the case: The role of statistics in human rights reporting.Statistical Journal of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe 18(2–3), 163–173.

Baral, N., Heinen, J.J., 2005. The Maoist people’s war and conservation in Nepal.Politics and the Life Sciences 24 (1–2), 2–11.

Barkey, H., Fuller, G.E., 1998. Turkey’s Kurdish Question. Rowman & LittlefieldPublishers, Boston.

Bilgili, E., 2001. Fire situation in Turkey. In: FAO, Global Forest Fire Assessment1990–2000. Forest Resources Assessment Working Paper 055. <www.fao.org/docrep/006/ad653e/ad653e69.htm>.

Biswas, A.K., 2000. Scientific assessment of the long-term environmentalconsequences of war. In: Austin, J.E., Bruch, C.E. (Eds.), The EnvironmentalConsequences of War: Legal, Economic and Scientific Perspectives. CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, pp. 303–315.

Bozarslan, H., 2004. Violence in the Middle East: From Political Struggle to Self-sacrifice. Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton.

Buhaug, H., 2007. The future is more than scale: a reply to Diehl and O’Lear.Geopolitics 12 (1), 192–199.

Buhaug, H., Lujala, P., 2005. Accounting for scale: measuring geography inquantitative studies of civil war. Political Geography 24 (4), 399–418.

Chuvieco, E., 1999. Remote Sensing of Large Wildfires in the EuropeanMediterranean Basin. Springer, Berlin.

CIA, 1986. Kurdish Areas in the Middle East and the Soviet Union. Map available at<www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/middle_east_and_asia/kurdish_86.jpg>.

de Jong, W., Donovan, D., Abe, K., 2007. Extreme Conflict and Tropical Forests.Springer, Heidelberg.

de Vos, H., Jongerden, J., van Etten, J., 2008. Images of war: using satellite images forhuman rights monitoring. Disasters (EarlyOnline).

Deger, M.E., 1977. CIA, Kontrgerilla ve Türkiye. Ankara, Imge.Dudley, P., Ginsberg, J.R., Plumptre, A.J., Hart, J.A., Campos, L.C., 2002. Effects of war

and civil strife on wildlife and wildlife habitats. Conservation Biology 16 (2),319–329.

Firat, G., 1997. Sozioökonomischer Wandel und etnische Identität in der kurdisch-alevitischen Region Dersim. Bielefelder Studien zur EntwicklungssoziologieBand 65. Verlag für Entwicklungspolitik Saarbrücken, Saarbrücken.

Fjeldså, J., Álvarez, M.D., Lazcano, J.M., León, B., 2005. Illicit crops and armed conflictas constraints on biodiversity conservation in the Andes region. AMBIO: AJournal of the Human Environment 34 (3), 205–211.

Gleditsch, N.P., 1998. Armed conflict and the environment: a critique of theliterature. Journal of Peace Research 35 (3), 381–400.

Guyer, J.I., Lambin, E.F., 1993. Land use in an urban hinterland: ethnography andremote sensing in the study of African intensification. American Anthropologist95 (4), 839–859.

Halperin, M., 1974. Bureaucratic Politics and Foreign Policy. The BrookingsInstitution, Washington, DC.

Human Rights Watch, 1995. Weapons Transfer and Violations of the Laws of War inTurkey. Human Rights Watch, Washington, DC.

_Imset, _I.G., 1995. The PKK: Freedom Fighters or Terrorists? American KurdishInformation Network, Washington, DC. <http://kurdistan.org/Articles/ismet.html>.

_Insan Hakları Dernegi, 1996. The Burned and Evacuated Villages, _Istanbul.Jetten, A., de Vos, H.J., 1994. Bomen voor de vogels, land voor de mensen: het

landbouwfront, agro-ecologische zonering en agrarische ontwikkeling in zuid-oost Nicaragua. In: de Vos, H.J., Vellema, S. (Eds.), Tot op de Bodem. VijfOpstellen over Landdegradatie, Ontbossing en Sociale Verhoudingen.Wageningen, Leerstoelgroep Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling,Studium Generale.

Jongerden, J., 2007. The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis ofSpatial Politics, Modernity and War. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden andBoston.

Jongerden, J., Oudshoorn, R., Laloli, H., 1997. Het Verwoeste Land, Berichten van deOorlog in Turks-Koerdistan. Breda, Uitgeverij Papieren Tijger.

Kemal, Y., 1995. Campaign of Lies. Der Spiegel 2. <www.xs4all.nl/�tank/kurdish/htdocs/lib/yasar_kemal.html>.

Kocher, M., 2004. Human ecology and civil war. PhD Thesis in Political Sciences,University of Chicago.

Korf, B., 2006. Cargo cult science, armchair empiricism and the idea of violentconflict. Third World Quarterly 27 (3), 459–476.

Kurdish Human Rights Project, 2002. Internally Displaced Persons: The Kurds inTurkey. Kurdish Human Rights Project, London.

Kurtulmuslu, M., Yazici, E., 2003. Management of forest fires through theinvolvement of local communities in Turkey. In: FAO, Community-Based FireManagement: Case Studies from China, The Gambia, Honduras, India, the LaoPeople’s Democratic Republic and Turkey. FAO, Rome. <www.fao.org/docrep/006/ad352t/AD352T08.htm#P0_3>.

O’Lear, S., 2005. Resource concerns for territorial conflict. GeoJournal 64 (4), 297–306.

Özdag, Ü., 2003. The PKK and Low Intensity Conflict in Turkey. Ankara, Frank Cass.Pamukoglu, O., 2003. Unutulanlar Dıs�ında Yeni Bir S�ey Yok, Hakkari ve Kuzey Irak

Daglarındaki Askerler. Harmony, Ankara.Price, S.V., 2003. War and Tropical Forests: Conservation in Areas of Armed Conflict.

Food Products Press (Haworth Press), New York.Prins, E., 2008. Use of low cost Landsat ETM+ to spot burnt villages in Darfur, Sudan.

International Journal of Remote Sensing. 29 (4), 1207–1214.Raleigh, C., Hegre, H., 2005. Introducing ACLED: an armed conflict location and

event dataset. Paper presented to the Conference on ‘‘Disaggregating the Studyof Civil War and Transnational Violence,” University of California Institute ofGlobal Conflict and Cooperation, San Diego, CA, 7–8 March 2005.

Richards, P., 2005. New war: an ethnographic approach. In: Richards, P. (Ed.), NoPeace No War, An Anthropology of Contemporary Armed Conflicts. James Curryand Ohio University Press, Oxford, pp. 1–21.

Richards, P., Ruivenkamp, G., 1997. Seeds and Survival: Crop Genetic Resources inWar and Reconstruction in Africa. IPGRI, Rome.

Roth, J., Taylan, K., 1981. Die Turkei – Republik Unter Wolfen. Verlag Lamuv,Bornheim.

S�ahan, T., Balık, U., 2005. _Itirafçı. Bir J_ITEM’ci Anlattı. Aram, _Istanbul.Sperling, L., 1997. The effects of the Rwandan war on crop production and varietal

diversity: a comparison of two crops. AgREN Network Paper 75, 19–30.Sperling, L., 2001. The effect of civil war on Rwanda’s bean seed systems and

unusual bean diversity. Biodiversity and Conservation 10 (6), 989–1009.State Statistics Institute [Devlet Istatistik Enstitüsü], 1990. General Population

Count [Nüfus Genel Sayimi], Ankara.State Statistics Institute [Devlet Istatistik Enstitüsü], 2000. General Population

Count [Nüfus Genel Sayimi], Ankara.Steinberg, M.K., Height, C., Mosher, R., Bampton, M., 2006. Mapping massacres GIS

and state terror in Guatemala. Geoforum 37 (1), 62–68.Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, 1995. Forced Evictions and Destruction of Villages in

Dersim (Tunceli) and the Western part of Bingöl, Turkish-Kurdistan, September–November 1994. Stichting Nederland-Koerdistan, Amsterdam. www.let.uu.nl/�martin.vanbruinessen/personal/publications/Forced_evacuations.pdf.

Tomes, R.R., 2004. Relearning counterinsurgency warfare. Parameters 34 (1), 16–28.Tunceli and Kopdag Project. n.d. <www.mmaj.go.jp/mmaj_e/project/mece/

tunceli.html> (Web site no longer available).Tunceli Sendikalar Platformu, 1996. Tunceli Sendikalar Platformun raporu. _Ilimizin

sorunları. In: Dersim, Tunceli Kültür ve Dayanis�ma Dernegi Yayın Organı, Yıl 2Sayı 4, Ekim, pp. 17–26.

Turner, M.D., 2003. Methodological reflections on the use of remote sensing andgeographic information science in human ecological research. Human Ecology31 (2), 255–279.

van Etten, J., 2004. Changes in farmers’ knowledge of maize diversity in highlandGuatemala, 1927/37-2004. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2 (12).

van Hoeve, E., Klaasse, A., 2001. Images of war: an analysis of war-related land usechanges by integrating expert knowledge and remote sensing. Thesis ReportGIRS-2001-30, Wageningen University.

White, P., 2000. Primitive Rebels or Revolutionary Modernizers? The KurdishNational Movement in Turkey. Zed, London, New York.

Yüce, M.C., 1999. Dogu’da Yükselen Günes�. Zelal, Ankara.