ENVIRONMENT AND SECURITY IN THE AMAZON BASIN

Transcript of ENVIRONMENT AND SECURITY IN THE AMAZON BASIN

ENVIRONMENT AND SECURITYIN THE AMAZON BASIN

Woodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas • #4

Edited by

Joseph S. Tulchin and Heather A. Golding

©2002 Woodrow Wilson International Center for ScholarsWashington, D.C

www.wilsoncenter.org

ENVIRONMENT ANDSECURITY IN THEAMAZON BASIN

Astrid Arrarás

Luis Bitencourt

Clóvis Brigagão

Ralph H. Espach

Eduardo A. Gamarra

Thomas Guedes Da Costa

Margaret E. Keck

Edited by

Joseph S. Tulchin and Heather A. Golding

Latin American Program

Woodrow

Wilson Center Reports on the A

mericas • #4

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARSLEE H. HAMILTON, DIRECTOR

BOARD OF TRUSTEESJoseph A. Cari, Jr., Chair; Steven Alan Bennett, Vice Chair. Public Members: James H. Billington,Librarian of Congress; John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States; Bruce Cole, Chair, NationalEndowment for the Humanities; Roderick R. Paige, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education;Colin L. Powell, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; Lawrence M. Small, Secretary,Smithsonian Institution; Tommy G. Thompson, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and HumanServices. Private Citizen Members: Carol Cartwright, John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, DanielL. Lamaute, Doris O. Matsui, Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin

WILSON COUNCILSteven Kotler, President. Diane Aboulafia-D'Jaen, Charles S. Ackerman, B.B. Andersen, Cyrus A.Ansary, Charles F. Barber, Lawrence E. Bathgate II, Joseph C. Bell, Richard E. Berkowitz, A.Oakley Brooks, Charles W. Burson, Conrad Cafritz, Nicola L. Caiola, Raoul L. Carroll, Scott Carter,Albert V. Casey, Peter B. Clark, William T. Coleman, Jr., Michael D. DiGiacomo, Sheldon Drobny,F. Samuel Eberts III, J. David Eller, Sim Farar, Susan Farber, Charles Fox, Barbara HackmanFranklin, Morton Funger, Chris G. Gardiner, Eric Garfinkel, Bruce S. Gelb, Steven J. Gilbert, AlmaGildenhorn, Joseph B. Gildenhorn, David F. Girard-diCarlo, Michael B. Goldberg, William E.Grayson, Raymond A. Guenter, Gerald T. Halpin, Edward L. Hardin, Jr., Carla A. Hills, Eric Hotung,Frances Humphrey Howard, John L. Howard, Darrell E. Issa, Jerry Jasinowski, Brenda LaGrangeJohnson, Shelly Kamins, Edward W. Kelley, Jr., Anastasia D. Kelly, Christopher J. Kennan,Michael V. Kostiw, William H. Kremer, Dennis LeVett, Harold O. Levy, David Link, David S. Mandel,John P. Manning, Edwin S. Marks, Jay Mazur, Robert McCarthy, Stephen G. McConahey, DonaldF. McLellan, J. Kenneth Menges, Jr., Philip Merrill, Jeremiah L. Murphy, Martha T. Muse, DellaNewman, John E. Osborn, Paul Hae Park, Gerald L. Parsky, Michael J. Polenske, Donald RobertQuartel, Jr., J. John L. Richardson, Margaret Milner Richardson, Larry D. Richman, EdwinRobbins, Robert G. Rogers, Otto Ruesch, B. Francis Saul, III, Alan Schwartz, Timothy R. Scully, J.Michael Shepherd, George P. Shultz, Raja W. Sidawi, Debbie Siebert, Thomas L. Siebert, KennethSiegel, Ron Silver, William A. Slaughter, Thomas F. Stephenson, Wilmer Thomas, Norma KlineTiefel, Mark C. Treanor, Christine M. Warnke, Ruth Westheimer, Pete Wilson, Deborah Wince-Smith, Herbert S. Winokur, Jr., Paul Martin Wolff, Joseph Zappala, Richard S. Ziman

ABOUT THE CENTERThe Center is the living memorial of the United States of America to the nation’s twenty-eighthpresident, Woodrow Wilson. Congress established the Woodrow Wilson Center in 1968 as aninternational institute for advanced study, “symbolizing and strengthening the fruitful relation-ship between the world of learning and the world of public affairs.” The Center opened in 1970under its own board of trustees.

In all its activities the Woodrow Wilson Center is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, sup-ported financially by annual appropriations from Congress, and by the contributions of founda-tions, corporations, and individuals. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publicationsand programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views ofthe Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that pro-vide financial support to the Center.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface viiJoseph S.Tulchin and Heather A. Golding

Chapter 1 1The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic PerspectiveRalph H. Espach

Chapter 2 31Amazônia in Environmental PoliticsMargaret E. Keck

Chapter 3 53The Importance of the Amazon Basin in Brazil’s Evolving Security AgendaLuis Bitencourt

Chapter 4 75Drug Trafficking, National Security, and the Environment in the Amazon BasinAstrid Arrarás and Eduardo A. Gamarra

| v |

Chapter 5 99SIVAM: Challenges to the Effectiveness of Brazil’s MonitoringProject for the AmazonThomaz Guedes da Costa

Chapter 6 115SIVAM: Environmental and Security Monitoring in AmazôniaClóvis Brigagão

List of Contributors 131

| vi |

PREFACE

This report and the conferences from which it was developed arethe results of a collaborative project between the WoodrowWilson International Center for Scholar’s Latin American

Program and the Environmental Change and Security Project. RalphH. Espach, former Program Associate of the Latin American Program andGeoffrey D. Dabelko, Director of the Environmental Change and SecurityProject, through the generous support of Woodrow Wilson CenterConference Funds, hosted a series of three public conferences duringSpring 2000: Environment and Security in the Amazon Basin;Environmental Policy in Amazonia; and, Brazil’s SIVAM Project:Implications for Security and Environmental Policies in the AmazonBasin.The conferences brought together select groups of experts and pol-icymakers to discuss issues such as: environmental and sustainable initia-tives in the Amazon Basin; the roles of local, national and internationalactors; Brazil’s national security agenda in relation to the Amazon Basin;and, the rising threat of international drug trafficking.

This volume is a compilation of papers presented at the conferences.Its aim is to provide new insights into the complex and politically delicatesecurity and environmental questions at stake in the Amazon Basin.

A number of central themes on national security and the environ-ment in the Amazon region run throughout the following chapters. Forthe purpose of a short introduction, it is worth highlighting in a generalway some of the issues of prime concern to the authors. First, particulardefinitions of security play a central role in determining how theBrazilian, regional, and international actors approach the problem ofenvironmental protection of the Amazon. The traditional securityapproach, which highlights national sovereignty and the military’s role inprotecting territorial integrity of the nation, is relatively less emphasizedthan in the past, given the emergence of more expansive notions ofsecurity. As Bitencourt points out, however, the security variable cannever be ignored in considering the reaction of Brazil and its military tointernational initiatives. We also see the prominence of the concept of

| vii |

| viii |

Preface

ecological security—an “ecosystemic” approach—in the Brazilian poli-cy debate. Likewise, drug trafficking and drug interdiction are increas-ingly viewed as interrelated national security and environmental issues,and events in Colombia and elsewhere ensure that such a focus willreceive continued attention.These approaches broaden our understand-ing of Amazônia policy and promise to promote efforts at environmen-tal protection.

Second, there appears to be considerable support in this volume for astronger regional or multilateral approach to the preservation of theAmazon. Greater Brazilian leadership in international cooperation on themanagement of Amazônia would likely redound to Brazil’s benefit in var-ious ways, as Espach explains. Regional cooperation is viewed as the bestapproach, albeit an unlikely one given nationalistic concerns, to addressenvironmental problems related to drug trafficking and interdiction. Wealso see that part of the value of the System for the Protection of theAmazon (SIPAM)—or policies aimed at increasing cooperation in region-al development—consists of potential joint actions and sharing of ideasamong private, national, regional, and international entities.

Third, as we also see below, SIPAM and the System for the Surveillanceof Amazônia (SIVAM) are central topics, yet the impact of the two instru-ments remains to be seen. SIVAM is a technologically advanced radar andsatellite network for improving the collection of regional information andmonitoring. On the one hand, the emergence of SIVAM indicates anextraordinary opportunity to take advantage of the most advanced tech-nology available today. Among SIVAM’s benefits, Guedes da Costa notes,could be the generation of knowledge that challenges the perception ofthe security threat to the region. On the other hand, SIVAM’s magnitudeand complexity raise questions of potential deficiencies in implementa-tion and evaluation. As Brigagão explains, absent SIPAM, which has faceddifficulties in getting established, SIVAM risks failing to become a fullydeveloped Amazon management tool.

Finally, and perhaps most important, is environmental politics andpolicymaking concerning the Amazon. Politics is always critical to anymajor issue of governance and, as Keck emphasizes, some conserva-tionists have ignored this advice to the detriment of their work in theregion. The question of the depth and effectiveness of the commit-ment of the Brazilian state to preservation will surely remain open.

Taking a new look at the policymaking process will help avoid theperpetuation of wrong-headed policy based on misleading concep-tions of Amazônia. It is hoped that this volume will to some degree aidin that reexamination.

CHAPTER SUMMARIES

This volumes opens with a chapter by Ralph Espach, who examines thehistory of Brazilian national security and developmental policies inAmazônia from the 1950s to the present. He particularly addresses the risein the 1970s of international interest in protection of the rainforest andthe reconceptualization of the national interest with respect to theAmazon following Brazil’s democratization and economic liberalizationin 1985. Early on, Brazil was highly critical of international environmen-talism, emphasizing a “protectionist concept of national security and sov-ereignty.” Since the mid-1980s, that policy has greatly evolved, especiallythrough increased support for the participation of multiple actors in creat-ing regional policies. Espach adds, however, that the current weak politicalcommitment to cooperative mechanisms for environmental managementpresents significant potential costs to Brazil.

Chapter two, by Margaret Keck, provides an historical review of thedevelopment of tropical deforestation as issue of international public pol-icy. Her focus is on the efforts of Brazilian and international conservation-ists to promote preservation of the Amazon and on the reaction thoseefforts have received in Brazil. She concludes by detailing five consistentpolicy-making mistakes made by conservationists seeking to protectAmazônia over the past two decades. These are: essentialism, keepingpoliticians out of the loop, assuming state officials are free and supportiveagents, failure to pay attention to the political context, and too oftenassuming money is the problem and capacity-building the solution.

In chapter three, Luis Bitencourt emphasizes the importance of under-standing Brazil’s traditional security agenda—the concepts associated withsovereignty and military force—in considering environmental protectionin the Amazon. He provides an overview of historical events and percep-tions of national security developments, including the Calha Norte Projectand SIVAM, and demonstrates the sensitivity of the Amazon theme and itspotential for forging a new military image. Bitencourt concludes that

Preface

| ix |

| x |

Preface

from the Brazilian security perspective, particularly in the military’s view,international interest in the Amazon continues to pose a large and grow-ing threat to the sovereignty of the region.

Chapter four, which examines the relationship between drug traffick-ing and environmental degradation in the Amazon Basin, is coauthored byAstrid Arrasás and Eduardo Gamarra. The authors clearly describe thedeleterious impact of the illicit drug industry on the environment.Interestingly, however,Arrasás and Gamarra emphasize that environmentaldegradation has also resulted—mostly unintentionally—from the effortsmade to halt these illegal activities. Drug interdiction in one part of theAmazon, for example, can push drug producers deeper into other parts ofthe rainforest (the so-called “balloon effect”). According to the authors,since the evolution of the drug industry and its environmental impactaffects the way countries deal with national security—and because itrequires nontraditional thinking about security—the approach to theproblem must be a coordinated regional or hemispheric effort aimed atavoiding further ecological damage.

In chapter five,Thomaz Guedes da Costa examines the justification forand creation of SIVAM, the system’s implementation, and most important,the prospects for evaluating its effectiveness.Among various potential usesof SIVAM, Guedes da Costa explains, is the repression of illegal activities,such as unauthorized mining, small arms trade, and especially drug traf-ficking.All of these are increasingly issues of national security. SIVAM canideally map areas of human presence—activities; movement by ground,air, or river; or settlements. Defining performance criteria for the evalua-tion of SIVAM is therefore critical so as to ensure its improvement andultimate success, Guedes da Costa concludes.

Clóvis Brigagão, author of the final chapter, takes a close look at whathe calls a new and expanded concept of security: “ecological security.”Ecological security, Brigagão writes, focuses on broader regional manage-ment and development of shared ecosystemic resources. Brazil’s establish-ment of SIPAM and SIVAM comprise a “new paradigm for the strategicmanagement of ecosystemic resources.” Examining the components andstatus of SIVAM, Brigagão views the highly sophisticated system as having“profound strategic value”—if the coordinated work of governmentagencies is coupled with greater participation from civil society, includinguniversities, research centers, and the business community.

This volume and the project from which it developed would nothave been possible without the help of many people. Special thanks toShanda Leather and Clair Twigg, of the Environmental Change andSecurity Project, who assisted in the organization of the conferencesthat led to this publication. Thanks are due to Leah Florence for herthorough copyediting of the chapters and to Gary Bland andJacqueline Lee, whose attention to detail was indispensable in preparingthis volume for publication. Also, special thanks to Derek Lawlor andKate Grumbacher for their excellent work on the design and layout ofthis volume.

Joseph S.Tulchin and Heather A. Golding

Preface

| xi |

CHAPTER 1

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic

PerspectiveRALPH H. ESPACH1

Brazil’s policies in Amazônia have traditionally been shaped by con-cerns of national security, in particular the need to integrate anddevelop the region in order to protect its territorial sovereignty.

This conceptual approach led to the developmentalist agenda of the 1950sto 1980s, which aimed to develop Amazônia economically and encouragemigration into the region, showing little concern for the environmentaleffects of these policies. In the eyes of a government whose overridinggoals were modernization and economic growth, the undeveloped rain-forest, inhabited mostly by Indians and missionaries, was little more thanan obstacle to national development. Until the late 1900s, the world out-side Brazil paid scarce attention.

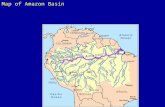

In the 1980s, however, the rise of the environmental movement in theUnited States and Europe created pressure on the Brazilian government tocrack down on deforestation. The international community declared theAmazon forests, the world’s largest contiguous tropical forest and home toover 20 percent of the world’s biological diversity and fresh waterresources, critical to the health of the global ecosystem. Brazil’s aggressivedevelopmental agenda received international condemnation. At first,Brazil responded to these pressures with a traditional nationalist argumentthat the international interest amounted to intervention and infringementon its sovereignty. In the late 1980s and 1990s, however, the shift in thenation’s political and economic strategies toward international opennessand cooperation raised the costs of its recalcitrance regarding environ-mental policy and forced it to accept the international community’s inter-est and involvement in Amazônia.

Today Brazil continues to reform its political and economic institutionsto make them more compatible with those of a global system dominated

| 1 |

by democratic, free-market nations.As a result, its economy has grown andbecome more competitive, and it has increased its importance in globaland regional politics.Amazônian policy, however, remains a sensitive pointin Brazil’s international profile. Policies at the federal level that aim to pro-tect areas of the forest and promote sustainable development are underfi-nanced, poorly integrated at the state and local levels, and engaged in astruggle against conservative political forces.These difficulties stem partlyfrom the nation’s brand of federalism, which gives significant power tostate and local governments. More importantly, the problems reflect a lackof political commitment to—and of public interest in—the welfare of theAmazonian region.

This paper argues that this lack of political commitment to effectivemanagement of Amazônia not only promises further destruction of therainforest, but also represents a failure to take advantage of an opportunityfor international leadership.The implementation of SIVAM, a sophisticat-ed satellite and radar system for improved surveillance of Amazônia, willincrease knowledge of the region, but is unlikely to change the politicalsituation. A national policy for the controlled management and develop-ment of Amazônia as a multi-use region, one that preserves its uniquebiological and human resources and mandates participatory local and stategovernment action and that gains from cooperation with the internation-al community, should be a central element of Brazil’s strategic internation-al agenda. By managing the discovery and development of the economicuses of the rainforest’s unique biological properties, as well as by demon-strating the capacity to preserve an increasingly scarce and valuableresource, Brazil could become the world’s leader in environmental affairs.An effective, participatory policy for environmental management inAmazônia—one supported by and enforced at the state and local levels—would improve Brazil’s control over and understanding of the region,increase the long-term economic returns from its development, and con-tribute to Brazil’s position as a regional and global power.

THE DEVELOPMENTALIST AGENDA OF THE 1950S TO 1980S

For most of Brazil’s history, the government saw Amazônia as vast, exoticterritory that should be opened for colonization and industry in order tomake economic use of it and to protect it from invasion. Factual knowl-

| 2 |

Ralph H. Espach

edge of the region’s geography, forests, and people was scarce. FewBrazilians were interested in inhabiting an environment so foreign andchallenging to a European-styled life. Except for during local booms inthe rubber industry in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the region receivedlittle migration.Though the government and especially the military wor-ried about this uncontrolled area—which constitutes over half of nationalterritory—there was little political support for an active national policy.The country’s economic and political power resided along the sugar-pro-ducing coast in the north, or in the coffee growing regions and large citiesin the south.The national security agenda focused mainly on scenarios ofconflict with Argentina, Paraguay, or Chile.2

In the middle of the 20th century the nation embarked on an ambi-tious program of industrialization and modernization.The construction ofBrasilia and the Belém-Brasilia highway, begun in 1958, attracted develop-ers, ranchers, and farmers to Amazônia. Influenced by positivist ideals thatscience, development, and industry were the keys to progress, governmentplanners viewed Brazil’s vast forests in the Amazon and other regionseither as materials for economic production or as obstacles to nationaldevelopment.3 In the late 1960s and 1970s, with lending from the WorldBank and the Inter-American Development Bank, the government builtroads and infrastructure, supported large-scale industrial projects, andoffered incentives for the clearing of the forest for economic ventures.Under the military government, the fundamental motivation of thisdevelopmentalist agenda continued to be protecting national sovereigntyand gaining international power by exploiting Brazil’s enormous naturalresources. “Intregar para não entregar,” (Integrate in order not to lose) wasthe underlying geostrategic principle. As proclamed by the father ofBrazil’s modern national security doctrine, General Golbery do Couta eSilva: “There was no middle ground for Brazil when it came toAmazônia; it could develop the region and secure grandeza, or it couldlose the region and, with it, Brazil’s grand destiny.”4

In general, this series of regional development and colonization pro-grams (which include the Polonoroeste Plan, begun in the 1950s, the Planfor National Integration of 1970, and the PolAmazônia of 1974) failed tomeet its objectives and was pursued at tremendous cost to the environ-ment. Instead of creating sustained economic growth, creating jobs, andserving as a safety valve for migration from other overpopulated regions,

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 3 |

these programs increased the rate of deforestation, worsened the concen-tration of land in the hands of speculators or wealthy investors, and exac-erbated social conflict.5 Economic production did not support the region’srapid population growth, and social welfare levels remained dismal. By themid-1980s it was widely recognized that these programs had failed togenerate expected levels of economic development. Cattle ranching inparticular, supported by government subsidies, had proven unproductiveand ill-suited to the land. Also, lawlessness prevailed in many areas openedup by the government. Fraudulent land entitlements abounded, alongwith speculation that drove up land prices, all of which contributed tofrustration and social conflicts which often turned violent.

The developmentalist agenda was also unsuccessful in its strategicobjective of protecting national sovereignty and security in Amazônia.Even with a heightened military presence (through the Calha Norte pro-gram) the government was unable to monitor or control illegal activitiesin the region.The building of roads, airplane landing strips, and a systemof scattered towns and settlements facilitated illegal mining, logging, andtrafficking operations. Also, massive infrastructure projects in Amazôniaand across the nation depended upon foreign lending and investment.Thiscontributed significantly to the growth of Brazil’s foreign debt in the1970s and 1980s, which weakened the nation’s negotiating position in theinternational community and made it vulnerable to the crippling eco-nomic crisis of the 1980s. Contrary to its nationalist security objectives, byopening the region to unregulated exploitation and increasing Brazil’sdependence on foreign lending, the developmentalist agenda contributedto the internationalization of the Amazon.6

THE RISE OF INTERNATIONAL INTEREST IN THE RAINFOREST

Beginning in the 1970s, Amazônia became a focus of an increasinglyorganized international environmental movement. As concern grew overglobal trends of deforestation and climate change, environmental groupsalready powerful within industrialized nations began to expand theirinterests globally. Brazil was an easy target. In the 1970s and into the1980s, the Brazilian Amazon had suffered deforestation at increasing ratesof between 20-30,000 km2 per year, reaching an estimated total ofapproximately 316,000 km2 between 1978 and 1988.7 An international

| 4 |

Ralph H. Espach

group of scientists, media figures, and policy makers led a campaign forgreater environmental awareness.This “epistemic community,”8 supportedby a growing body of research on the local and global effects of industrialwaste, overuse of resources, and pollution, pushed for change in the per-ceptions and policies of national governments and the international lend-ing institutions.9

The increase of international environmentalism coincided with andcontributed to increasing tensions between underdeveloped and devel-oped nations. The Brazilian government’s emphasis on a protectionistconcept of national security and sovereignty made it an outspoken criticof the internationalization of environmental policy. Brazil was a leader incriticizing the international environmental agenda, denouncing it as a newform of imperialism from the industrialized North. The world’s growinginterest in Amazônia as an “international resource,” or “the lungs of theworld,” was criticized as an open declaration of enfringement on Brazil’snational sovereignty.10

At the first major United Nations conference on the environment, heldin Stockholm in 1972, Brazil championed the interests of the less devel-oped nations, or the South.The Brazilian delegation argued that econom-ic growth must be the foremost priority of developing nations and thatpressure from Northern environmentalists was hypocritical since theNorth was responsible for most of the world’s pollution and degradation.Brazil argued that in the South environmental issues should principallyconcern problems of health and social well-being, in both rural and urbanenvironments. Pressure for environmental conservation, the delegationargued, was part of a Northern strategy to preserve those resources fortheir own exploitation. Brazil and its partners formulated these positionswithin a context of North-South tensions over a range of issues, includingtrade and investment patterns, attempts to control the spread of nucleartechnology and weapons, and external interference in domestic affairsdriven by a Cold War rationale.Though the Brazilian position was widelycriticized by the environmental movement and many Northern govern-ments, the arguments it raised did, over years, help to alter significantly theinternational community’s perceptions of responsibility for environmentaldestruction as well as its policy prescriptions for improving the globalenvironment. The Kyoto Treaty of 1996 reflects this shift in approach, somuch so that it is criticized by many in the U.S. Congress for placing dis-

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 5 |

proportionate burden on industrialized nations and letting off developingnations too easily.

During the 1980s Brazil’s refusal to accept international pressureregarding its policies in Amazônia, even as deforestation continued at his-torical rates, became seriously detrimental to its international relations.Brazil was singled out by leaders of the environmental community as achief actor in the deterioration of the global ecosystem. The Braziliangovernment refused to meet with these groups and denounced the move-ment as a tool of imperialist governments of the North. Unable to open aserious dialogue with the government, activists, and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) pressed their case on global andregional lending institutions and the United States Congress. In 1987, theNational Wildlife Fund and the Environmental Defense Fund attractedglobal attention to the plight of the Amazon forests and their people byhosting Chico Mendes, the charismatic leader of the Brazilian RubberTappers Union, on celebrated trips to Washington and to Europe.

Within Brazil, this international activity coincided with and fomentedan increase in domestic public awareness of environmental issues and anemergence of a network of socioenvironmental NGOs.Although democ-ratization in 1985 had opened up the political sphere to a variety of actorsand political parties, a domestic environmental movement was slow todevelop. Concern for the environment was simply not a public priority,and Brazil’s civil society—which was increasingly urban—was more moti-vated in other areas. In Amazônia, ongoing development, the concentra-tion of land ownership, and the clearing of forests led to increased socialconflict and violence, often between the ranchers, industrialists, or otherwealthy landowners who owned immense tracts of land, and disen-franchized groups such as rubber tappers and Indians, for whom thedestruction of the forest meant the end of their traditional livelihoods andcultures.This violence and the struggle over the fate of the Amazon forestsgrabbed international attention in 1988 with the assassination of ChicoMendes.

Mendes’ murder galvanized international support for these threatenedlocal groups and drew condemnation of the unwillingness or inability ofthe Brazilian government to protect the region’s forests or people fromdestruction. The Mendes murder also brought together Brazil’s nascentenvironmental movement and the well-entrenched, national social rights

| 6 |

Ralph H. Espach

movement, which traced back to the activism of the Catholic Church inthe 1960s and was strong in the industrialized south.This emergence of acommon agenda among environmentalists, social rights organizations,unions, and the Workers’ Party (Partida Trabalhista, or PT) significantlyincreased the domestic political currency of environmental issues.11 Thefuneral for Mendes, attended by 2000 people from across Brazil, includingthe rising leader of the Workers’ Party Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, was apowerful public demonstration of the common interests of labor acrossBrazil, from factory workers to rubber tappers.12

However, the primary force behind Brazil’s eventual shift inAmazonian policy was external. Under sustained pressure from this inter-national environmental campaign, the U.S. Congress threatened to with-hold funding for the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bankunless these organizations took measures to enforce environmental pro-tection standards. In 1989, the two banks canceled their support for majorenergy and road-building projects in Brazil. The demand for responsibleconservation and environmental management policies, according to thevalues of the international environmental movement, had influenced theagendas of the most powerful international institutions.With the cancela-tion of those loans, Brazilian policy makers found themselves under thethumb of a network of domestic and international NGOs and foreignpolicy makers, whose collective power derived from their ability to influ-ence and enforce international values and standards for public policies,both international and domestic.

Combined with the crippling economic crisis of the 1980s, whichwas also largely the result of external factors and Brazil’s dependenceon foreign financing, Brazilians became painfully aware of the implica-tions of the more internationalized global system for their domesticprerogatives.

THE SHIFT IN BRAZIL’S ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AS PART

OF A LARGER CHANGE IN THE NATION’S STRATEGIC VISION

Following democratization in 1985, Brazil’s foreign relations and strategicpolicies took a dramatic turn. During the “lost decade” of economic stag-nation in the 1980s, the nation had lost confidence in the import-substi-tution-industrialization economic model, and had begun to open further

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 7 |

its economy to international trade and investment. Like most of LatinAmerica, the spread of democracy and free-market economics pushedBrazil to soften its position on national sovereignty and non-intervention-ism and accept the necessity and potential benefits of enhanced interna-tional cooperation and exchange.

Brazil’s and Argentina’s newly revived democracies took steps to turntheir traditional rivalry into partnership, which led to the successfulMERCOSUL project and a range of initiatives for institutional coopera-tion. Brazil softened its official position against the interests of the Northand explored areas in which it could serve as a “strategic bridge” betweenthe industrialized and non-industrialized worlds.13 Along with its neigh-bors, Brazil abandoned its nuclear program, signed on to internationalnon-proliferation accords for chemical and biological weapons, and par-ticipated more actively in regional institutions, promoting itself as SouthAmerica’s natural regional power.

In this context of enhanced openness, increased trade, and partnershipwith the international community, the linkage between the concerns oflocal Amazônian NGOs such as the rubber tappers’ union and interna-tional environmental groups was a critical development.Though environ-mental issues were beginning to be of interest to the Brazilian voters, theynever developed high political salience.14 The influence of Brazil’s domes-tic environmental movement was limited by its failure to overcomeregional and ideological fragmentation.15 The dramatic shift in Brazilianenvironmental policy, which began during the Sarney administration(1985-1990), occurred largely because the nation’s environmental record,especially in the high-profile case of Amazônia, began to impinge uponthe achievement of its economic goals, which depended on attracting for-eign capital and increasing exports. The contradiction between Brazil’sinternationalist economic and foreign policy strategies and its nationalist,sovereignty-oriented position on Amazônia become untenable, especiallyfollowing the withdrawal of IDB and World Bank funding for develop-ment projects. Paulo Tarso Flecha da Lima, the Secretary General of theForeign Ministry, remarked that the international attention Brazil receivedat the time and the withholding of World Bank funding was “the greatestinternational pressure Brazil has lived through in the whole of its histo-ry.”16 The need for international acceptance as a respectable, modern-minded democracy forced Brazil’s hand.17

| 8 |

Ralph H. Espach

In 1988, Brazil approved a new constitution that remains today one ofthe world’s most progressive in terms of environmental conservation.President Sarney countered domestic and international criticism ofBrazil’s environmental policies by passing a series of measures namedNossa Natureza. Reflecting the president’s ties to the military, the programcombined a commitment to conservation and to exploring extractive, sus-tainable development practices with the traditional nationalist, sovereign-ty-oriented approach of the national security doctrine. Among otherthings, Nossa Natureza created IBAMA (the Brazilian Environment andRenewable Resources Institute), a federal agency for the coordination ofenvironmental policy. However, the definition of IBAMA’s mission wastoo narrow, and the bureaucratic agencies it included were too politicallyweak and poorly funded for the agency to be effective.18 At the same time,Sarney appeased the armed forces by approving the Calha Norte(Northern Trench) operation, designed to create a permanent militarypresence in the northern Amazon to protect the region from a purportedthreat of encroachment. Still, the modified language and acceptance ofsome of the principles of the environmentalist agenda—such as “sustain-able development” and the setting aside of land for extractive enterprise—indicated a new direction in Amazonian policy.

President Fernando Collor de Mello (1990-1992) quickened the open-ing of Brazil’s economy to international trade and investment and pushedfor an enhanced role for the nation in international affairs. By champi-oning internationalism and emphasizing Brazil’s purported destiny as theleader of South America and an emerging world power, Collor set thetone for Brazilian foreign policy throughout the 1990s. In line with hisdrive to draw Brazil closer to the international community, he appointeda noted environmentalist, José Lutzenberger, as Secretary of theEnvironment, created a new Secretariat for the Environment (SEMA),established a National Environment Program (PNMA), and passed a num-ber of reforms aimed at strengthening the coordination and enforcementof environmental policy. At least in the short-run, the results were a sig-nificant reduction in deforestation rates, increased demarcation of Indianlands, and more effective government action against illegal miners, loggers,and perpetrators of violence (including Chico Mendes’ assassins).

One of the highlights of this strategy was Brazil’s hosting the UnitedNations’ Earth Summit in 1992, in Rio de Janeiro. The Summit suc-

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 9 |

ceeded in bringing international attention to Brazil’s improved environ-mental record. Hosting the Summit also widened domestic publicawareness of environmental issues and generated a tremendous increasein the number of environmental NGOs in Brazil and their capacity forcooperation. At the June 1990 meeting of the Brazilian Forum forEnvironmental and Developmental Social Movements and NGOs(Forúm Brasileiro de ONGs e Movimentos Sociais para o Meio Ambiente eDesenvolvimento), the number of participating groups was 40. In 1991there were 800; in 1992 1,200.19

Critics continued to argue that the heightened international activityregarding Amazônia compromised national sovereignty, but Brazil clearlybenefited from warmer relations with the international community. Thechange in the federal government’s environmental stance removed amajor sticking point in foreign lending and debt negotiations, allowingBrazil easier access to the foreign lending and investment. Strategically,Brazil’s admission that a healthy Amazônia was a legitimate interest of theglobal community opened the way for considerations as to how Brazilcould benefit from international cooperation in that area. Brazilian diplo-mats and their colleagues from other developing nations expressed thetrade-off their nations face between social and economic improvementand environmental conservation. The community of scientists andexperts that previously had targeted Brazil as an environmental villainnow sided with the nations of the South in arguing that the high con-sumption lifestyles of the North bear most responsibility for global envi-ronmental degradation. If underdeveloped nations were to preserve theirnatural resources instead of exploiting them for development, theyargued, wealthier nations should assist them in developing alternativemeans for economic growth.

Assistance for projects that support sustainable, environmentally con-scious economic activities in the Amazon was forthcoming. By far thelargest was the Pilot Program to Conserve the Brazilian Rainforests(PPG-7), an agreement made in 1991 between the Brazilian governmentand those of the Group of Seven industrialized nations to fund a variety ofprograms, with a total cost of $1.56 billion. Brazilian environmentalNGOs attracted increased funding and technical cooperation from inter-national partners, including the World Wildlife Fund and the NatureConservancy, which work in partnership with local NGOs to manage

| 10 |

Ralph H. Espach

large-scale park lands.20 After years of criticizing debt-for-nature swaps asexploitation, Brazil accepted its first one in 1991.

Under president Itamar Franco (1992-1994), the government gave lessattention to environmental policy.The government’s principal goals wereto control inflation, stabilize the economy, and broaden internationalcommercial ties. Under the current administration the emphasis on eco-nomic stability continues, but president Fernando Henrique Cardoso(1994-2002) has made a series of efforts to strengthen national environ-mental policy and to protect more Amazônian forest from destruction.The 1990s have seen the introduction of a number of major national envi-ronmental programs, and the government has reserved approximately17 percent of national territory for use as Indian lands, national parks, etc.(although much of these reserved lands have yet to be demarcated).This isthree times the amount of land reserved in this way in 1985.21 UnderCardoso, the Planafloro program progressed—after prolonged negotiationwith skeptical NGOs—and national codes were changed to requirelandowners in Amazônia to maintain forest coverage on 80 percent oftheir lands.22 The government also encouraged cooperation with localNGOs and communities on sustainable development programs. In 1995,Cardoso launched the “Green Protocol” requiring five federal banks toinclude environmental impact assessments in their evaluations for projectloans. Also, the regional network of NGOs, private enterprises, and state,local, and federal environmental agencies that cooperate on sustainabledevelopment projects has grown and become increasingly sophisticated.23

Cardoso’s political reforms, including consistent cutbacks in federalspending, have encouraged the decentralization of public policy in manyareas. In Amazônia, much interesting and exciting work is in progress atthe local level, within states and national parks, to develop sustainablefarming, ranching, and extractive practices that are compatible with theenvironment. Acre’s governor Jorge Viana, a member of the Workers’Party, is one of the more prominent regional leaders who has found polit-ical success through a conservation-oriented policy platform. “The forestis the answer, not the problem,” according to Viana.24 Viana’s success, alongwith that of other regional leaders, such as the new Secretary for theCoordination of Amazonian Policy in the Ministry of Environment, MaryAllegretti, and Senator Marina da Silva, a rubber tapper’s daughter fromAcre who is a leading proponent of biodiversity rights, demonstrates the

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 11 |

growing political value of an environmental friendliness. Although suchleaders remain a minority and face a mostly apathetic national public andvarious entrenched, well-heeled groups pushing for more development,their growing presence is an important development in the politics ofAmazônia.

Despite Cardoso’s positive initiatives, his administration’s overall envi-ronmental record is mixed. Improved monitoring of the region has indi-cated that deforestation remains a problem, mostly due to illegal burningand logging, and social violence over land remains severe.25 In 1998, firesin Roraima, which burned out of control for a month, destroyed around15 percent of that state’s forests. For over a month the Brazilian govern-ment downplayed the fires and refused offers of fire-fighting assistancefrom the United Nations,Argentina, and Venezuela. Some prominent mil-itary officers predictably denounced these offers as another ploy by whichforeigners would gain control over Brazil’s forests. As Brazil’s inability tocontrol the fires became embarassingly clear, President Cardoso had tostep in and accept the assistance of the international community.The fireswere quelled eventually by rain.

Cardoso’s environmental policy has been compromised by reductionsin the federal budget, by resistance and negotiation from state and localleaders, and by the lack of institutional and operational capacity to enforceexisting laws and to implement new ones. Under pressure from the sugarcane industry, President Cardoso in late 1997 vetoed a clause in the envi-ronmental crimes law that would have imposed fines and sentences onparties that light fires without taking environmental precautions, a deci-sion censured by Brazilian and international environmental NGOs.26

Although large-scale federal development projects are on the wane, theAmazon forests today are more threatened than ever by the lack ofresources, institutional capacity, and political commitment to law enforce-ment, so that destructive mining, logging, and forest-clearing practicescontinue. In many ways, the fate of the remaining Amazon forests lies inthe balancing of short-term political interests, such as the support Cardosoneeds from Amazonian members of Congress on other legislative issues,against the nation’s long-term interest in maintaining a thriving, globallyunique reserve of tropical forest resources.

Information regarding the progress of the hundreds of local and stateprograms, as well as federal activities, and that gives a balanced evaluation

| 12 |

Ralph H. Espach

of the state of affairs across the vast region is difficult to find. There aremany specific instances of national parklands or protected reserves inwhich local NGOs, with the support of local government and in cooper-ation with international NGOs, conduct promising sustainable develop-ment practices and improve the income and basic living standards of thelocal population.The Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve, in Acre (govern-ment funded); the Jaú National Park (cooperatively managed by the localFundação Vitória Amazônica [FVA] and the World Wildlife Fund); andthe Serra do Divisor National Park in Acre (cooperatively managed bySOS Amazônia and the Nature Conservancy) are prominent examples oflocal sustainable development and management programs.

However, these local-level endeavors do not reflect a clear nationaltrend or any defined outcome of policy making at the national level. Landuse is actually decided at the local level, where the individual interests andeconomic and political factors that determine whether an area is cleared,farmed, developed, or left alone are complex and resistant to outside inter-ference. For instance, it is apparent in some cases that protected lands,under the control of Indian communities, have been made available tologgers for a cut of the earnings. Government policy in the Amazonregion is fragmented among various bureaucratic agencies, activities at thestate or local levels, and through the nature of its relationships with variousNGOs (both domestic and international), development agencies, farmers,miners, Indians, private corporations, and other local interests. Successiveadministrations have added additional layers or components to the envi-ronmental bureaucracy to address different issues or to create the appear-ance of activity. As Senator Marina da Silva recently declared:

…we heard a lot from the government that we need to work in partnership.I repeated what I think, which is that this partnership needs to be between pub-lic institutions and civil society, but it’s fundamental, above all, that partnershipis made among our own public agencies.

How many resources, how many times, are wasted and used in isolation?!With SUFRAMA doing one thing, SUDAM another, BASA and the BNDESanother, our final objective we would like to see is never reached.27

IBAMA, SUDAM, and other federal agencies that oversee environ-mental management generally remain underfunded and politically weak.Although interest in Amazon affairs and environmental policy is growing

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 13 |

in the Brazilian Congress, for the majority of leaders these issues remain oflow political priority.

The 1990s have seen a decline in the intensity of international atten-tion to the management of the Amazon. International public interest inenvironmental issues has subsided from its peak in the early 1990s, largelythe victim of the perceived success of many of the environmental move-ment’s earlier high-profile campaigns, such as saving whales and baby seals.Also, the international media turned their focus to human disasters such asfamine and the rise of brutal ethnic fighting in Africa and Eastern Europe.Although deforestation in the Amazon continues, the short-termimprovement in deforestation rates in the early and mid-1990s quelledinternational panic over the destruction of the rainforest.

Domestically, in the second half of the 1990s the Brazilian governmenthas labored to address other profound national problems, such as the needfor economic liberalization, political reform, and improved social welfare.Cardoso’s focus on much needed political reforms and the difficulties he hasfaced in maintaining his coalition of support in Congress have limited hiseffectiveness in other areas.The shared agenda among social rights activists,urban NGOs, and the environmental movement has frayed, weakening thenational political power of environmental NGOs relative to others whoadvocate for other causes, such as urban issues and land reform. In somecases the interests of environmentalists are less compatible than before withthose of their former partners, even if they both still share their generalopposition to large business, industry, and conservative political forces.28

With the decline in international attention and Brasilia’s limited politi-cal interest in Amazonian issues, national security concerns continue tohave significant influence on the formulation of regional policies.Although legitimate national security issues, including drug traffickingand forest fires, must be addressed, the persistence of traditional, national-ist concepts of sovereignty and security, which argue for the aggressivedevelopment of Amazônia and its isolation from international interests,contradict the nation’s larger strategic agenda. I will discuss the question ofnational security regarding Amazônia further on, but first I want todescribe how the current institutionalized international system requiresnational security perceptions and policies more coherent with Brazil’sincreasing international role and its agenda of insertion into the group ofglobal powers.

| 14 |

Ralph H. Espach

THE MANAGEMENT OF AMAZÔNIA AS A CRITICAL ELEMENT

OF BRAZIL’S STRATEGY FOR INSERTION IN THE

INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM

I accept the basic premise of the increasingly dominant institutionalistcamp of international relations theory, which states that a prominent fea-ture of the post-Cold War international system is the growing importanceof multilateral institutions. Institutions are “persistent and connected sets ofrules and practices that prescribe behavioral roles, constrain activity, andshape expectations.”29 Countries tend to join or to form cooperative insti-tutions or “regimes” because the rules and behaviors they support lead toimproved stability, provide structures for negotiation, increase the pre-dictability of states’ actions, and reduce the costs and risks of internationaltransactions.30 Although countries that wield more power in the realistsense tend to wield more influence within institutions as well, institutionaldecision-making opens space for dialogue, negotiation, and compromise.The behavior that derives from membership in a collective institutionrestricts the likelihood that powerful states will act unilaterally because itraises the punitive costs of such action. Institutionalism diffuses power, andprovides normative—and in some cases legal—structure for internationalbehavior. For less powerful countries, participation in international regimesopens avenues for negotiation and insertion in policy making that wouldnot be available to them if they were acting alone or if they depended onnegotiating one-on-one with more powerful countries.31

It is argued that the interdependence that comes with the globalizationand increased institutionalization of international relations restricts statesovereignty. Sovereignty, however, is a complex concept based on anabstract ideal. Indeed, any influence on a state’s autonomy in makingdomestic policy can represent an erosion of operational sovereignty—its abil-ity to do what it wants when it wants. On the other hand, interdepend-ence and cooperative membership in an institutionalized system reinforcesa state’s formal sovereignty—its ability to negotiate and participate as anequal in the international arena.32 A nation’s refusal to accept to somedegree the values and rules of the game of the international system canlead to severe violations of its operational and formal sovereignty, as in thecases of Iraq and Yugoslavia in the 1990s. In the late 1980s, external pres-sure on Brazil’s domestic environmental policy threatened its operational

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 15 |

sovereignty by raising the costs of maintaining its economic developmentstrategies in the Amazon region. However, by accepting the principles andnorms of the international community regarding environmental manage-ment, Brazil strengthened the validity of its claim as a responsible interna-tional partner and increased its maneuvering space and leverage in negoti-ations over the costs, trade-offs, and responsibilities of environmental con-servation. This strengthened position was manifest in Brazil’s success, incooperation with other nations of the South, at negotiating the terms ofthe Kyoto Treaty of 1996.

The values and behavior of international institutions are no more stat-ic than are those of the nations of which they are constituted. As scientif-ic understanding, technologies, and social values change over time, so dostandards and values for international behavior. In the institutionalizedinternational system, “rule-taker” nations—those that have little power bythemselves to influence the global system—can seek to expand theirinfluence and further their interests by affecting the evolution of the rulesof the game. Joseph Nye states that international politics in an inter-con-nected world increasingly involve what he terms “soft power,” or the abil-ity to attract through cultural or ideological appeal.33 While Nye refersprimarily to the influence of the United States, nations such as Canada,Sweden, and Chile—in the economic development model it representedin the late 1980s and 1990s—enjoy a higher profile in the internationalcommunity than is proportionate to their military or economic power(i.e. their “hard power”). Their soft power comes from the respect theyhave earned among their neighbors and around the world for the effec-tiveness of their diplomacy, their involvement and leadership in interna-tional institutions or projects, or the successes of their policies. Soft poweris stimulated and spread through the sharing of information, values, ortechnologies. In a hierarchical world where hard power is hard to gain andtenuous or expensive to maintain, the pursuit of soft power throughimproved influence and bargaining capacity within the institutions thatshape interstate conduct, is an attractive strategy for states traditionallyseen as rule-takers.

In Brazil’s case, where its geography blesses it with a treasure chest of arare and increasingly valuable global resource—biodiversity—there istremendous opportunity for the expansion of influence as a key player ininternational environmental policymaking. Enhancement of Brazil’s

| 16 |

Ralph H. Espach

international position will require increased participation in the activitiesof the international community and the demonstration that it is capable ofimplementing cooperative environmental management and developmentprojects worth imitating.

From the start, as environmental issues rose to prominence in interna-tional politics in the 1960s, Brazil has always been a major player. Brazilplayed a lead role in the 1972 U.N. conference in Stockholm, and in the1980s and 1990s, Brazil and its partners influenced effectively the percep-tions of responsibility, cost, and cost-sharing on the protection of the envi-ronment in developing nations. The federal government promotes coop-eration on research and sustainable development projects with the WorldBank and IDB. It also accepts the active involvement of NGOs in thedesign and implementation of local programs. Brazil is working coopera-tively with corporations, both foreign and national, in the exploration andresponsible management of Amazônian resources. One very promisingfederal program, Probem, encourages cooperation with foreign companiesas partners at a biotechnology lab to be built in Manaus.34 Instead of view-ing these resources in a purely physical sense or through the prism of tra-ditional security concerns, the government has realized that the informa-tion and knowledge that come from research in the rainforests is poten-tially of far higher value than any possible use of the land cleared of itsunique flora and fauna.

Building cooperation on environmental problems and designing insti-tutions that arbitrate among the conflicting interests of states, corporationsand investors, NGOs and other actors is a highly complicated task.35

Values, standards, and codes of conduct must be negotiated among a vari-ety of conflicting political and economic interests. However, because theseissues are still relatively young in international politics, there is ample spacefor non-traditional actors to insert themselves in the formulation of therules of the game. In the last twenty years, international environmentalNGOs capitalized on this opportunity to fortify their interests across theworld. Rule-taker states likewise can bolster their international positionsby acting energetically and collectively. This is a natural opportunity forBrazil to build upon the leadership it has already demonstrated andassume a lead role in the negotiation of terms that pertain to the conser-vation and development of its environmental resources through, for exam-ple, biodiversity accords.

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 17 |

The issue of “biopiracy” and “bioroyalties” is particularly contentious,and Brazil is active in the promotion of the 1992 Convention onBiological Diversity. A national version of a law that requires “bioroyali-ties” is under consideration in the Brazilian Congress, including a measurethat prohibits foreigners from conducting research without a local part-ner.36 Belonging to the Convention has benefited Brazil by encouraginginternational support for a national bio-diversity program, Pronabio,which was established in 1996 along with a national biological trust fund,Funbio. These programs are partly funded by the World Bank and aredesigned to strengthen public-private collaboration to protect nationalbiodiversity and to support an active NGO and government information-al network.

Despite the benefits to be gained from this international activity, thereremains a strong measure of protectionist sentiment that would prefer tosee the Amazon less open to foreign interests. International biodiversityrights are not secured.The Convention on Biological Diversity still lacksmembership from many key nations of the North, including the UnitedStates. Nevertheless, Brazil would suffer from a policy that restricts explo-ration and research in the Amazon region. Such a policy would furtherpostpone or lose forever the opportunity for greater understanding of theresources of Amazônia, while the logging, mining, fires, and populationpressures in the region would continue. International research and coop-eration brings a higher degree of technical skill and resources into Brazil,materials and knowledge that will be used by and for Brazilians as much asby foreign researchers.What is needed is a national and international legalframework that protects the interests and property rights of the nation andpeople of the Amazon.

The shift between 1987 and 1992 in Brazil’s Amazônian policy—amove away from an emphasis on development and toward the principlesof conservation and sustainable development—was largely a response tothe nation’s changing status within the international system.The country’sinsertion into the international community and its growing economicinterdependence made it increasingly vulnerable to external pressures,while external interest in its domestic policies in Amazônia had reachedan apex. Like all nations, Brazil faced increasing economic pressures fromthe process of globalization, in which it competes for foreign investmentand export markets with other newly opened or developing economies.

| 18 |

Ralph H. Espach

At the end of the 1990s, Brazil’s insertion into the international systemcontinues. Its importance as a regional power and a key player in the glob-al economy is increasingly evident, and Brazil demands greater attentionas an economic and political partner and as a participant in internationalinstitutions. The trend over recent decades for the institutionalization ofinternational affairs offers Brazil and other “middle-” or “emerging-power” nations a range of opportunities to balance their interests againstthe political power of the dominant nations and to improve their politicalpositions for the pursuit of their international interests. For example,Brazil’s foremost strategic goal of accession to permanent membership onthe U.N. Security Council depends largely on the legitimacy it can gen-erate within the international community as a responsible, capable actorand as an active partner in cooperative initiatives. The continuance andconsolidation of its policies for a more open, more cooperative approachto the management of Amazonian resources—one that includes the par-ticipation of local NGOs as well as the controlled, transparent involve-ment of international NGOs, researchers, and where appropriate, theresources of foreign governments—will strengthen its legitimacy. Thisstrategy improves Brazil’s capacity to understand, control, and manageeffectively its Amazonian territory, and thereby strengthens national secu-rity, whereas a traditional security-based approach that emphasizes devel-opment would likely continue the historical pattern of uncontrolledexploitation. The improved legitimacy gained from being the effectivesteward of and sovereign over a unique set of global resources wouldenhance Brazil’s power and importance in global affairs.

AMAZÔNIA AND BRAZILIAN NATIONAL SECURITY

Although the Brazilian government’s approach to the Amazon shifted dra-matically between 1985 and 1995, developmentalist thinking remainspowerful, particularly within the military and conservative political camps.The environmental movement within Brazil has not succeeded in generat-ing public awareness and activism at the level seen in industrialized nations.This is partly the result of institutional weakness and the lack of channelsfor the expression and influence of non-traditional parties (minoritygroups, the poor, etc.) within Brazil’s political system.Also, some scholars ofBrazilian culture claim that Brazilians’ perceptions of their inland forests

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 19 |

and wetlands have always been antagonistic and exploitative.37 Land and theenvironment are perceived to exist to be conquered and reshaped forhuman ends (a perception not at all limited to Brazil). Structuralists suggestthat this attitudinal tendency is also supported by Brazil’s position histori-cally at the periphery of the global capitalist system.38

Whatever the cause of this predisposition, these perceptions were sig-nificantly altered by the diffusion of international environmentalism in the1980s and 90s, and today the Brazilian media cover environmental issueson a regular basis.A congressional debate over the proposed weakening ofthe national forestry code in May 2000 generated a high-level of nationalattention. Except for these ephemeral bursts of outrage, however, theBrazilian public shows shallow interest in experiencing or conserving itsnational resources. Few Brazilians have ever visited the Amazon region orthe Pantanal. Most reside in cities and naturally place political priority onjob creation, economic stability, reducing crime, improved health andeducation systems, and other urban issues instead of the welfare of therural environment. This general lack of public concern, today as in thepast, often leaves Amazônian policy under the influence of powerful spe-cial interests such as regional industrialists, large-scale agribusiness corpo-rations, and politically connected landowners.

The end of the Cold War introduced a need for new definitions ofnational security and for a reconsideration of the role of the armed forces.For Brazil, like many countries, the threat of state-based military conflicthas diminished while nonstate, transnational phenomena—internationalcrime, terrorism, illegal migration, and the cross-border transfers of nar-cotics or arms, for example—has grown. Especially in Latin America,where interstate military conflict is relatively rare, the concept of nationalsecurity has broadened to include threats to a population’s economic,social, environmental, and even cultural life. In Brazil’s case, the end of tra-ditional rivalry with Argentina, the growing importance ofMERCOSUL, and warming relations with Chile, Paraguay, and Boliviadramatically altered the long-standing national security agenda. One ofthe military’s traditional missions, monitoring the borders with Argentina,Paraguay, and Bolivia for military activity, was made obsolete. Financialhardship and fiscal cost-cutting threatened the budget of the armed forcesat the same time that their primary mission—preparation for war againstArgentina and other neighbors—was diminished.

| 20 |

Ralph H. Espach

With democratization and a more cooperative regional foreign policy,the national security agenda shifted to other concerns, including a newemphasis on the protection of the Amazon. The Calha Norte operationindicated that traditional national security interpretations were still influ-ential in strategic thinking about Amazônia. Though Calha Norte hasnever been fully implemented, the statements of military officers and con-servative political leaders show that the topic of security in the Amazonstill generates strong emotions. For example, in June 1999, Senator LuizOtavio (PPB party member, Parana), denounced the presence of interna-tional NGOs in Amazônia:

It’s important, at this moment, to recall the NGOs that, with great hysteria,pretended to be more realist than the king of our Amazônia. For this, it is diffi-cult to establish an understanding with these organizations. … These organiza-tions (NGOs) are led by the headlines of the media. Greenpeace, by the way,will set up a base there in Amazônia; they will have their own boat there totravel our territories, our riches, also to interfere with the ecological balanceand our resources, of our riches. I give you my alert: por aí, não!39

Recently the Brazilian media has reported the alleged presence ofinternational terrorists in Amazônia (members of Peru’s Sendero Luminosoand Mexican Zapatistas, who are purportedly there to help train theMovimento dos Sem Terra [MST]) and the unmonitored activity of U.S.Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents involved in antidrug operationsin the Amazon.40 In accordance with the historical pattern, the sovereign-ty issue is invoked and military officials and politicians express their “pre-occupations” with territorial control.The expansion of drug trafficking inthe region is a serious threat, as are potential incursions by foreign insur-gents such Colombian guerilla groups and illegal miners or loggers.Nevertheless, these concerns are routinely exaggerated by military officersand conservative nationalist groups in order to provide a rationale formore state-based control and less openness or cooperation with NGOs,local or international. Some analysts argue that generating fears overnational security breaches in the Amazon is a traditional ploy to defendthe armed forces’ budgetary interests.41 The armed forces, whose preoccu-pation with the pursuit of “control” of Amazonia coincides politicallywith the interests of the region’s industrialists and landowners, remain apowerful actor in Amazonian affairs.Their geostrategic, traditionalist con-

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 21 |

ceptions of security and sovereignty continue to influence the formula-tion of regional policy.

The Brazilian armed forces must have a presence and a defined missionin support of Brazil’s national policy for Amazônia.Today’s threats, howev-er, are different from the fears of invasion by Venezuelan, Guyanese, orU.S. troops, as was hypothesized earlier in the century when the nation’smodern concept of security was formed. Brazilian policy makers and mil-itary officials have been working to establish the bureaucratic and institu-tional means to apply the armed forces to nontraditional challenges. In1999, following Roraima’s disastrous fires in 1998, IBAMA began coordi-nating with the military to use helicopters for the monitoring of forestfires in the region.42 This involvement of the military in nontraditionaloperations such as policing or fire fighting carries risks.The armed forcesare not culturally nor bureaucratically designed to take on nonmilitarytasks that involve cooperation with local police and civilians.The militarycan carry out policing or assistance functions in the short term or in spe-cific situations, but applying the armed forces to nontraditional operationsfor a long period of time can confuse their role within the state and affecttheir preparedness to carry out their principal task of armed combat.TheBrazilian armed forces are quick to recognize this fact and are reluctant toaccept an expanded version of their duties, as has happened in Venezuela,for instance, where President Chávez has utilized national troops to fulfilllocal social policy needs such as the distribution of medical supplies androad building. Brazil’s armed forces also have been cautious toward grow-ing pressure from congress for a militarized response to domestic drugtrafficking. They are mindful of the corruption that has infected thearmed forces of Mexico, Colombia, and other nations as they were drawninto combating the drug trade.

The mission of the armed forces in Amazônia should be specific andwell defined and must be formulated and overseen by the civilian govern-ment it serves. The Brazilian armed forces currently do not have undueinfluence over the policy making of civilian officials in the Amazonregion, although they do seek to protect their budget and relative autono-my. In the first decade of this new century, the militarization of the regionor regional policies is extremely unlikely. However, if security problemslike drug trafficking, social violence, and uncontrolled fires continue toincrease in Amazônia or if the democratic government comes to be con-

| 22 |

Ralph H. Espach

sidered incapable of controlling regional events, history indicates thatthere would be strong popular support for an increased military role in theregion. For this reason, the government and in particular the new Ministryof Defense must present a clear, specific regional mission for the armedforces that balances security concerns with developmental, economic, andsocial goals.

Determining the appropriate role the armed forces should play inmodern Amazônia is a complicated task with domestic and internationalpolitical and security implications.The vastness of the region and the den-sity of its forests make effective monitoring and enforcement difficult, andillegal activities and social violence continue to take place on a regularbasis.43 There is no shortage of laws and provisions covering Amazônia.The Brazilian constitution is regarded as one of the most environmentallyprogressive in the world. The problem is that these laws are poorlyenforced.

One significant step toward better monitoring and understanding ofAmazônia is the creation of SIVAM (Sistema de Vigilância da Amazônia), aregional satellite and radar surveillance network. This technologyimproves the nation’s ability to monitor and study the dynamics ofAmazônia, including its ecology, deforestation, vulnerability to fires, agri-cultural potential, and the location and extent of developmental activities,legal and otherwise. SIVAM and the information it generates are powerfultools for the management of Amazônia. The principal question is howBrazil’s institutions for scientific research, public policy, and enforcementcan best assess this new information and put it to good use.

In many areas—ecological and agricultural study, territorial demarca-tion, and demographic analysis—Brazil benefits by cooperating with tech-nologically sophisticated, well-funded international NGOs and multilat-eral institutions. Regarding security, some degree of cooperation isundoubtedly necessary to confront transnational threats such as drug traf-ficking. However, the operational or institutional requirements of effectiveregular collaboration or partnership are extremely difficult to meet. Anycooperative initiative must be carefully defined to suit the capacities of theinstitutions involved. Cooperation with a partner that has superior tech-nology, training, and resources (such as the United States) must involve, onsome level, the sharing of that training or capacity with Brazilian institu-tions, and at all times these cooperative operations must be transparent and

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 23 |

under the supervision of civilian authorities.This requires effective, activedomestic institutions both to take advantage of this cooperation—researchinstitutions, government ministries, university programs, etc.—and tooversee and protect national and local interests—i.e. legal enforcement—so that the national community can participate responsibly and can maxi-mize its gains and minimize the costs of the interaction.

Political obstacles, domestic and international, complicate cooperationin Amazônia. The nations that share the Amazon River basin haveattempted in the past to collaborate on economic development, trade, andother objectives. These projects have had little effect due to a paucity ofresources and political commitment. Although regional dynamics do pro-duce “externalities,” or cross-border spillover effects both good and bad,these externalities are not of sufficient political or security importance togenerate a strong response.44 The Amazon basin remains relatively unpop-ulated and poorly understood, and the fate of its Indians, rivers, miners,trees, and generally low-income population simply is not a high priorityfor national politicians. Crises such as the fires in Roraima or the massacreof Indians in Eldorado in 1996 bring momentary cries of outrage, but thisinterest is not sustained.

The forest fires that ravaged Roraima’s forests in 1998 offer a trenchantdemonstration of the challenges facing international cooperation in theAmazon Basin. Brazilian conservatives, especially the armed forces, react-ed to offers of external assistance and the international criticism the coun-try received for its inability to control the fires with their traditionalresponse: any such assistance and interference is a threat to national sover-eignty. To quiet these complaints and to reassert Brazil’s official opennessto international cooperation, President Cardoso welcomed this assistancepublicly, even while he asserted (against all evidence) that he had confi-dence in the national armed forces’ ability to protect Brazil’s sovereignty.45

One can imagine that if these fires were consuming thousands of acres ofRio Grande do Sul or São Paulo, the government would have reactedmore quickly, and an international team of firefighters—composed per-haps of MERCOSUL and U.S. members—would promptly have beenaccepted as a natural facet of regional relations.The point is that interna-tional cooperation with Brazil’s neighbors to the north and northwest lagsfar behind the institutionalized integration the country has establishedwith those to the south, and the people of Amazônia pay the price not

| 24 |

Ralph H. Espach

only in relative vulnerability to security threats such as fires, but also interms of economic and social underdevelopment.

If sustainable development projects such as eco-tourism, biochemicalresearch, and extractive export industries were to increase in economicvalue, so naturally would the importance of regional stability and thepolitical and economic impacts of regional externalities. All the govern-ments of the region, like Brazil, stand to gain international prestige andleverage from a well-managed, responsibly developed Amazônia that isprotected from looting by more effective local enforcement of laws andtighter national and international legal codes. These externalities—thelosses and gains that result from either further destruction or the responsi-ble management of Amazon resources—exist today, although they areundervalued.The sooner these nations recognize the importance of suchresources for sustainable economic development and international lever-age and then work together to secure the benefits, the greater will be theirfuture gains as the proprietors of a thriving and productive Amazônia.

CONCLUSION

Brazil’s policy toward Amazônia has evolved significantly since democrati-zation in 1985.Today the region shows a wider variety of land use, greaterconservation, improved monitoring and legal enforcement, and significantareas of promising experimentation with projects for sustainable econom-ic development. Most importantly, the nation’s democratic system hasshown the capacity to support the participation of multiple actors andinterests—local, national, public and private—in the formulation ofregional policies.

Nevertheless, deforestation and environmental degradation continuebeyond government control. Brazil’s national policy on the managementof Amazônian resources is weakened by fragmentation among variousgovernment agencies, a scarcity of political will and public resources, andinstitutional weakness. Laws often go unenforced, either through ineffec-tive monitoring, poor enforcement, corruption of public officials, or thefailure to adjudicate cases in a timely and effective manner. Individuals,special interest groups, corporations, and even politicians negotiate dealsand find ways to bypass laws for their own advantage.46 As a result, despitewhat is now a long record of progressive legislation for environmental

The Brazilian Amazon in Strategic Perspective

| 25 |

preservation or management, and a host of public-private and NGO-sponsored partnerships for local level development, the unique biologicaland human resources of Amazônia continue to disappear.This record con-tinues to be a prominent stain on Brazil’s international profile.