Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

-

Upload

indah-putri -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

1/22

Entrepreneurial andprofessional CEOs

Differences in motive and responsibilityprole

Eleni Apospori, Nancy Papalexandris and Eleanna Galanaki Athens University of Economics and Business, Athens, Greece

AbstractPurpose To shed some light on the motivational prole of entrepreneurial as opposed toprofessional CEOs in Greece.

Design/methodology/approach Based on McClellands motivational patterns, i.e. power,achievement and afliation, as well as responsibility; interviews with Greek entrepreneurial andprofessional CEOs were conducted. Then, interviews were content-analysed, in order to identifydifferences in motivational proles of those two groups of CEOs.Findings Achievement, motivation and responsibility were found to be the most signicantdiscriminating factors between entrepreneurial and professional CEOs.Research limitations/implications The current research focuses only on McClellands typology.Other aspects affecting entrepreneurial inclination are not studied in the current paper.Practical implications One of the major implications deriving from the identied characteristicsof successful entrepreneurial and professional CEOs has to do with the preparation and training of young leaders for both larger and smaller rms.Originality/value This paper studies, for the rst time, the leadership prole of CEOs in Greeceand identies differences between professional and entrepreneurial ones. This is of great value in an

SMEs dominated economy, such as Greece, where these research ndings can be used for thedevelopment of entrepreneurship.Keywords Entrepreneurialism, Leadership, Responsibilities, Chief executives, GreecePaper type Research paper

IntroductionThis paper examines possible differences in motives and responsibility betweenprofessional and entrepreneurial CEOs. The study draws on McClellands theory of Leader Motive Prole (LMP) and has been conducted as part of GLOBE, a larger,cross-cultural research project. GLOBE, running currently in 60 countries, iscoordinated by Wharton Business School and examines the effects of diverse factors onleadership behaviour and organisational practices (House, 1998). Following a brief literature review on differing motives among entrepreneurs and professionals, thepaper presents the results of a research conducted among a sample of Greekentrepreneurial and professional CEOs.

Motives of entrepreneursRecent years have witnessed a rise in the research effort devoted to entrepreneurshipand entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship is dened as a process of creating somethingdifferent with value by devoting the necessary time and effort, assuming the

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available atwww.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7739.htm

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

141

Received October 2003Revised July 2004

Accepted September 2004

Leadership & OrganizationDevelopment Journal

Vol. 26 No. 2, 2005pp. 141-162

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited0143-7739

DOI 10.1108/01437730510582572

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

2/22

accompanying nancial, psychic and social risks, for rewards of monetary andpersonal satisfaction (Hisrich and Brush, 1985, p. 15). Given the important boost inGDP and employment created by entrepreneurs, both academics and governments areaiming at encouraging entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship symbolises innovation anda dynamic economy (Orhan and Scott, 2001). Which is the prole, however, of theentrepreneuring minds? Several theories and opinions have been expressedconcerning the motivation of the entrepreneur and several characteristics have beensaid to distinguish entrepreneurs from professionals.

At one time, the entrepreneur was depicted largely in negative connotations. Theentrepreneurs were seen as ruthless robber barons who exploited people andresources while rationalizing the necessity of progress (Sexton and Bowman, 1985,p. 130), as well as cunning, secretive, with strong exploitive, narcissistic andsadistic-authoritarian tendencies (Maccoby, 1976 in Sexton and Bowman, 1985, p. 130)and not remarkably likeable people (Collins et al., 1964 in Sexton and Bowman, 1985,p. 130). Since the economists have recognised the vital role of entrepreneurs in

economic and social growth, the entrepreneur was considered the catalyst fortransforming and improving the economy. Insights into the entrepreneurs role underan economics perspective were provided by Cantillon (1931) (uncertainty-bearing roleof the entrepreneur), Jean- Baptiste Say (1845) (coordinating function), Marshall (1961),Knight (1921), Schumpeter (1934) (innovation function) and Kirzner (1981), Bosma et al.(2000), Sexton and Bowman (1985).

Apart from economics, the entrepreneur has also been approached under the light of different perspectives. Since the beginning of the century, a research stream focused onthe role that the entrepreneurs personal attributes may play in shaping entrepreneurialactivity. The personal attributes of the entrepreneur and the perspectives on whichresearch has been based are:

The entrepreneurs experiences and environment. Under this perspective, careerdissatisfaction or having parents who were entrepreneurs can be a strong motivator of entrepreneurial activity (Cromie et al., 1992; Brockhaus, 1980a, 1980b; Gartner, 1989).

The entrepreneurs socialisation process. One of the classics in this perspective isMcClelland who hypothesized that some societies produce more entrepreneurs becauseof a socialization process that creates a high need for achievement (McClelland, 1961).

The push and pull factors affecting the entrepreneur. Pull and Push factorsare now a common way of explaining different motivations to start a business (Orhanand Scott, 2001; Alstete, 2002). Push factors are elements of necessity such asinsufcient family income, dissatisfaction with a salaried job, difculty in nding workand a need for a exible work schedule due to family responsibilities. Pull factors relateto independence, self-fullment, entrepreneurial drive and desire for wealth, socialstatus and power. Entrepreneurs are driven by two opposite factors of choice andnecessity according to the relative importance of the push and pull factors.However, the situation is rarely a clear-cut selection of pull or push factors and thefactors are often combined (Alstete, 2002).

Among the entrepreneurial motivations found in most surveys carried out inindustrialized countries, independence and the need for self-achievement, both pullfactors, are always ranked rst (Hisrich et al., 1996, Orhan and Scott, 2001). Othercauses were usually found to be much less important. However, when occupational

LODJ26,2

142

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

3/22

exibility, providing choice in terms of the hours worked (a push factor), is included inthe survey, this is also identied as another important factor motivating femaleentrepreneurship in particular (Hisrich et al., 1996).

Personality traits of the entrepreneur. This perspective refers to specic qualities orfactors which identify entrepreneurs in society. Much of the empirical research onentrepreneurs has focused on exploring how they differ from other managers and howthese differences may explain their desire to start a business (Kisfalvi, 2002). Some of these characteristics include a high need for achievement (McClelland, 1961), aninternal locus of control, a moderate risk-taking propensity, a tolerance for ambiguity,self-condence, innovativeness, (Cromie, 2000) and a high need for autonomy,independence (Cromie et al., 1992; Hornaday and Aboud, 1971), dominance andself-esteem (Sexton and Bowman, 1985; Kets de Vries, 1985).

All theories include elements that can help us explore entrepreneurial behaviour.Project Globe, on which the present study is based (House, 1998), chose as theoreticalbackground McClellands theory of non-conscious motivation. McClelland (1975)introduced a theory of entrepreneurial effectiveness based on the role of achievementmotivation. His intention was to explain aspects of leadership and in particular leaderbehavior and effectiveness as a function of a specic combination of predispositionsand motives, referred to as LMP. McClellands theory states that the motivationalaspects of human beings can be explained in terms of four non-conscious motives invarious combinations (1985). These motives are achievement, power, afliation andsocial responsibility. McClelland developed the theory of entrepreneurial effectivenessbased on the pivotal role of achievement motivation. Furthermore, he developed histheory of leader effectiveness based on assertions concerning the optimumcombination of the above four motives.

According to McClelland and Burnham (1976), all managers fall into threemotivational groups. The rst group is mostly motivated by achievement, the second

by afliation and the third by power. The achievement motive is a non-consciousconcern for achieving excellence in accomplishments through ones individual efforts(McClelland et al., 1953). Managers motivated mostly by setting goals and reachingthem, put their own achievement and recognition rst. This motive is one of the mostwidely discussed characteristics distinguishing entrepreneurs from professionalmanagers, as entrepreneurs usually score higher on it (McClelland, 1986). Afliationmotive is a non-conscious concern for establishing and restoring close personalrelationships with others. The afliative managers need to be liked more than theyneed to get things done. Their decisions are aimed at increasing their own popularityrather than promoting the goals of the organization. In terms of entrepreneurialinitiative, the afliation motive could lead to the decision to create ones own business,in order to pass something to the kids or to offer some employment security to thefamily, a motive affecting 15 per cent of decisions on small business creation (Barrow,1993). Power motive is a non-conscious concern for acquiring status and having animpact on others. Managers who are mostly interested in power recognize that you getthings done inside organizations, only if you can inuence the people around you; so,they focus on building power through inuence rather than through their ownindividual achievement. The power motive in terms of entrepreneurship motivationcould be expressed in the much discussed and established in several surveysentrepreneurial characteristics of locus of control, autonomy, and dominance

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

143

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

4/22

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

5/22

H2. To the extent that achievement has been hypothesized to be higher amongentrepreneurs, and to the extent that power has been hypothesized to be on arather high level in both groups of leaders (McClelland, 1975, 1985), we makethe hypothesis that the difference between power and achievement will besmaller for the entrepreneurs than for the professionals.

Power achievement (entrepreneurs) , power achievement (professionals).

H3. Greek entrepreneurs will score higher in afliation motives than Greekprofessional CEOs. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that theformer may be motivated to launch and run their own company for the sake of employment security for their relatives.

Afliation motive (entrepreneurs) . afliation motive (professionals).

H4. With regard to the various indicators of social responsibility, we hypothesize,for the same reasons stated in H3 , that entrepreneurs will show a higher levelof concern for others than professionals.

Concern for others (entrepreneurs) . concern for others (professionals).

H5. Finally, to the extent that entrepreneurs are described as individuals withhigh need for autonomy, independence and risk taking propensity (Cromie,2000; Sexton and Bowman, 1985), we hypothesize that they will score lower onthe indicator of internal obligation.

Internal obligation (entrepreneurs) , internal obligation (professionals).

Methodology

Sample descriptionA total of 30 entrepreneurial CEOs and an equal number of CEOs or top managers inlarger companies were initially contacted. An attempt was made to match activities of companies in the two groups. The size of the respondent companies was over 30employees. A very high response rate was achieved, as 47 out of the 60 CEOs initiallycontacted gave an interview. That is, the refusal rate was only 21.66 per cent.

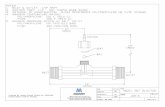

All companies selected were successful in their sector, according to traditionalmeasures of entrepreneurial success, such as the prots made by the entrepreneur, thegenerated employment by the entrepreneurial function and the survival time of thecompany (Bosma et al., 2000, p. 17). All the 47 companies examined have shown protfor the previous three years, employ at least 15 people each and have been active intheir eld for at least ve years; therefore, they show entrepreneurial success in all thethree above-mentioned measures. So it can be said that the sample consisted of overallsuccessful rms. In the sample all the sectors of the economy are represented and thecompanies differ both in size and location. As shown in Figure 1, the majority of thecompanies operate in the service sector. This is considered as an advantage of thestudy, since the majority of the Greek companies operate in the service sector (OECD,2002a). Moreover, launching an enterprise in services is easier (because of lower sunkcosts) than in the manufacturing or primary sector, so, in the services sector a morebalanced partition among entrepreneurial and professional rms is expected.

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

145

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

6/22

Data collection and description of variables

Methods of data collection. The data were collected through face-to-face structuredinterviews with the CEO of each company of the sample. All the interviews were recordedon tape and then typed exactly as initially phrased. The interviews comprised thefollowing ten questions requests concerning the characteristics, beliefs and experiences of the CEO as well as the establishment, the goals and the strategy of the company:

(1) Would you briey, taking about ve to eight minutes, describe your career todate, beginning with your education and then when you rst entered amanagement position?

(2) When you assumed your present position was there a mandate for what youwere expected to accomplish, a number of problems you were expected ordesired to solve, goals you expected or desired to achieve, or a vision of your

own or someone elses to be accomplished?(3) What were the strengths of the organization that you expected to help you

accomplish your mandate?(4) What were the major deciencies in the organization, or the major problems or

barriers facing you, in accomplishing what you hoped to accomplish?(5) What are your major strengths with respect to your functioning as a CEO in

your current position?(6) What are your major weaknesses?(7) Please describe the most important organizational changes that you plan to

implement in the near future?

(8) How do you plan to go about it? (Probe for how he or she will introduce thechange and the strategy for its implementation.)(9) Please describe your philosophy of management (this is usually already

implicitly described in the answers to the above questions). If time permitsrequest the CEO to describe the second most important change he/she wants tointroduce, and repeat question 8 with respect to this change.

(10) Are there any other considerations we need to know about in order tounderstand your role in your current position?

Figure 1.Partition of respondentsby activity sector

LODJ26,2

146

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

7/22

Variables/measurements. The variables used for the purpose of the present paper are:the binomial variable entrepreneurial/professional, the measures of socialresponsibility, achievement motive, afliation motive and power motive.Entrepreneurial is a categorical variable indicating whether the interviewee is anentrepreneur (1) or a professional CEO (0).

The operationalization of social responsibility is based on Winter (1985) andBarenbaumsmethodology who have developed and validated a measure of social responsibility. Themeasure has been based on quantitative content analysis of narrative text material. Theindicators of responsibility included ve components: moral standards, obligation, concernfor others, concern for consequences of ones actions, and self-judgement:

(1) Moral-legal standards of conduct is scored, according to Winter, when actions,people, or things are described in terms of some abstract standard or principlethat involves legality, morality, or virtuous conduct.

(2) Internal obligation is scored when a person/character or a group is described asobliged to act, or not to act, because of internal or impersonal forces not inresponse to the act of another person or group.

(3) Concern for others is scored when a person/character or group is described ashelping someone else (whether this help is solicited or not) or is sympatheticallyconcerned about another person.

(4) Concern about negative consequences is scored when a person/character orgroup is described as having some inner concern worry, anxiety, being upset,or even just reecting about the possible negative consequences of her ownaction, or inaction, either in anticipation or in retrospect.

(5) Self-judgment is scored when a person/character or group is described ascritically evaluating her own character (Winter, 1991).

The three measures of motives achievement, afliation and power, have also beenbased on quantitative content analysis of narrative text material (Winter, 1991). Inparticular, achievement is scored for any indication of standard of excellence. Suchstandards are expressed in one of the following forms:

. adjectives which evaluate performance positively;

. goals or performances, which are described in ways that suggest positive evaluation;

. mention of winning or competing successfully with others;

. negative feelings or concern for failure or lack of excellence; and

. unique accomplishments.

Afliation is scored for any indication of establishing, maintaining or restoringfriendship or friendly relations among persons or groups. The four basic indications of this motive are:

(1) expression of positive, friendly or intimate feelings toward others;(2) negative feelings about separation or disruption of a friendly relationship or

wanting to restore it;(3) afliative and companionate activities; and(4) friendly, nurturing acts such as helping, sympathetic concern and so forth.

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

147

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

8/22

Power motive is scored for any indication that a person or group has impact, control orinuence on another person, group or institution. According to Winter (1991) there aresix basic indicators of power:

(1) strong forceful actions which may have impact on other people;(2) control or regulation, especially through gathering information or checking up

on others;(3) attempts to inuence, persuade, convince, make or prove a point;(4) giving advice, support or help that has not been explicitly asked for;(5) impressing others; and(6) strong emotional reactions to the actions of others.

Data analysis and resultsContent analysis of interviews codication of the results. The interviews were content

analysed by two independent experts on content analysis based on the scoringconventions described above. Content analysis is a research methodology that utilizesa set of procedures to make valid inferences from text. In order to draw valid inferencesfrom the text, it is important that the classication procedure used be reliable in thesense of being consistent. Different people should code the same text in the same way(Weber, 1985). Each of the 47 interviews was considered as running text verbalmaterial of variable length (Winter, 1991). Each sentence was scored by the two expertsindependently for whichever of the above-mentioned eight indicators was present.However, consecutive sentences were not scored for the same indicator, unless someother indicator occurred between the two occurrences. Each occurrence of each of theeight indicators was scored 1; the total is divided by the number of words in the textand then multiplied by 1,000 to give a score of the interviewee for each variable per

1,000 words.After the two scores given by the two experts, a reliability check was performed foreach of the eight variables. In particular, for each interviewee, we computed percentageagreement between the two expert scorers of each variable by following the formula:

Percentage agreement

2 x number of agreements between the two scorers on thepresence of the motive

Number of times exert #1 scored the motive number of times exert #2 scored the motive

The percentage agreement is the reliability score of the variable for each of theinterviewees. Therefore, we calculated 8 47 reliability scores. Then, an overallreliability score was calculated for each interviewee.

The minimum reliability score for each of the variable as well as for the overallscore should be 0.85. For infrequently scored motives, percentage agreement scoresmay run lower, so long as the overall gure is 0.85 or higher (Winter, 1991). In thepresent research all of the reliability scores were above 0.85 with the exception of theinfrequently scored indicator of concern for consequences (0.78).

LODJ26,2

148

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

9/22

Quantitative analysis Descriptive analysis. In the quantitative data analysis stage, the rst step towards thecomparative approach was a Kolmogorov-Smirnov nonparametric test for thenormality of distribution of the variables Table I.

Several variables were found not to be normally distributed; in particular, thesevariables were obligation, for the group of professionals, self-judgment for the group of entrepreneurs, achievement motive for both of the groups, and power motive for theentrepreneurs only. Since the data show a departure from normal distribution amongseveral of the variables used in the analysis and because of the relatively small size of the sample we used a non-parametric test to explore possible differences betweenprofessionals and entrepreneurs. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test utilized for thispurpose gave the results presented in Tables I and II. However, it should be mentionedthat a t -test for difference of means gave identical results.

The moral standard variable was found to have the second lowest mean scores after concern for consequences of all the responsibility measures. Both theprofessionals group (0.44) and the entrepreneurs group (0.64) have relatively low meanscores in moral standards indicator, compared to internal obligation, concern for othersand self-judgment. Although the group of entrepreneurs have a slightly higher meanscore than the group of professionals, this difference did not prove to be statisticallysignicant (0.978) between the two groups.

Internal obligation is a very high responsibility measure for both groups. The meanscore on internal obligation for professional CEOs (3.18) is the highest and the one forentrepreneurs, (1.63) is the second highest of all the mean scores of the indicators of social responsibility after self-judgment (2.11). Although both groups score relativelyhigh, the mean score for internal obligation is substantially higher for the group of professionals than that for entrepreneurs ( p 0.001).

Concern for others is the third lower measure for the two groups, professionals and

entrepreneurs. The slight difference between the mean score of entrepreneurs (0.83)and professionals (0.65) is not statistically signicant ( p 0.756).

Kolmogorov-Smirnov (a)Entrepreneurial Statistic df Sig.

Standard responsibility Professional 0.43 27 0.000Entrepreneurial 0.38 20 0.000

Obligation responsibility Professional 0.14 27 0.200Entrepreneurial 0.19 20 0.053

Other responsibility Professional 0.32 27 0.000Entrepreneurial 0.31 20 0.000

Concern for consequences Professional 0.43 27 0.000

Entrepreneurial 0.44 20 0.000Self-judgement Professional 0.19 27 0.015Entrepreneurial 0.13 20 0.200

Achievement motive Professional 0.12 27 0.200Entrepreneurial 0.11 20 0.200

Afliation motive Professional 0.27 27 0.000Entrepreneurial 0.26 20 0.001

Power motive Professional 0.20 27 0.006Entrepreneurial 0.19 20 0.061

Table I.Kolmogorov-Smirnov

non-parametric test fornormality

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

149

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

10/22

M o r a l

s t a n

d a r d s

I n t e r n a l o b

l i g a t

i o n

C o n c e r n

f o r o t h e r s

C o n c e r n

f o r

c o n s e q u e n c e s

S e l f - j u d g m e n t

R e s p o n s

i b i l i t y

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

M e a n

0 . 4 4

0 . 6 4

3 . 1 8

1 . 6 3

0 . 6 5

0 . 8 3

0 . 2 8

0 . 4 3

2 . 2 2

2 . 1 1

M e d

i a n

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

3 . 4 9

1 . 3 7

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

1 . 8 6

1 . 7 9

M i n i m u m

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

M a x

i m u m

5 . 0 6

5 . 4 3

6 . 6 3

7 . 5 6

6 . 2 5

6 . 5 6

2 . 0 4

2 . 9 8

1 2 . 0

5

5 . 2 2

9 5 p e r c e n t c o n

d e n c e

i n t e r v a

l f o r m e a n

0 - 0 . 8 9

0 - 1 . 1 3

2 . 4 1 - 3 . 9 6

0 . 7 6

- 2 . 5

1

0 . 0 9

- 1 . 2

1

0 . 1 2 - 1

. 5 5

0 . 0 5

- 0 . 5

1

0 . 0 3

- 0 . 8

3

1 . 2 5

- 3 . 1 8

1 . 4 5

- 2 . 7

7

K o l m o g o r o v - S m

i r n o v

Z

0 . 5 0 9

1 . 9 6 4

0 . 6 7 3

0 . 4 3 6

0 . 6 5 5

S i g n

i c a n c e

0 . 7 5 6

0 . 9 9 1

0 . 7 8 5

N o t e s :

P =

P r o

f e s s

i o n a l ; E =

E n t r e p r e n e u r

Table II.Descriptive statistics of social responsibilityindicators andsignicance tests of differences

LODJ26,2

150

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

11/22

Concern for consequences was found to be the lowest responsibility measure for bothgroups; the mean score for the group of professionals is 0.28 and for the group of entrepreneurs 0.43. This difference between the groups was not found to bestatistically signicant ( p 0.991).

Self-judgment is a strong responsibility measure for both groups. In particular, forthe group of entrepreneurs the mean score on self-judgement (2.11) is the highest scoreof all the responsibility measures. For the group of professionals, the mean score onself-judgment is the second highest score (2.22). However, the slight difference betweenthe scores of professionals and entrepreneurs is not statistically signicant p 0.785).

Summing up the descriptive statistics on social responsibility, we could say thatboth groups score high on the self-judgment and internal obligation indicators.However, the group of professionals has signicantly higher scores on internalobligation than the group of entrepreneurs. Finally, tests of differences t -test as wellas non-parametric tests using one combined indicator of the overall score on socialresponsibility did not reveal signicant differences between entrepreneurs andprofessionals; in other words these two groups showed similar levels of socialresponsibility (Table III).

The descriptive ndings concerning the variables achievement motivation, powermotivation and afliation motivation for the two groups of respondents, professionalsand entrepreneurs are presented in Table III.

Comparing the two groups within each motive or within the disposition of responsibility, the overall picture coming from Table III shows that entrepreneurs aresignicantly different from professionals in terms of the achievement motive. Inparticular, we observe that the mean score of the achievement motive appears to beconsiderably higher for entrepreneurs (5.87) than for professionals (2.87). Thedifference is statistically signicant at 0.005 level. No signicant difference was foundin the afliation motive mean scores between professionals and entrepreneurs. The

power motive is relatively strong for both groups, but no signicant difference appearsto exist in power between entrepreneurs and professionals. Finally, as alreadymentioned, entrepreneurs are not signicantly different from professionals in socialresponsibility.

The employed non-parametric tests of differences shown in Table IV verifystatistically and in more details the differences among the three motives and socialdisposition within each of the groups. Starting with the group of entrepreneurs weobserve that the levels of social responsibility and achievement are comparable (sig.0.795). According to the McClellands theory, successful leaders show higher levelsof power than achievement, but, contrary to this theory, the successful Greekentrepreneurs interviewed under the current study show higher achievement thanpower motives (sig. 0.002). Moreover, Greek entrepreneurs present high socialresponsibility, which is comparable to achievement (sig. 0.795) and signicantlyhigher than power (sig. 0.013) With regard to professionals, we observe that inaccordance to McClellands theory, they score higher in power than in afliation (sig0.026). However, in contrast to this theory, the power level is not signicantlyhigher than the achievement level (sig. 0.883). Achievement is more signicant forGreek professional CEOs than afliation (sig. 0.018). Social responsibility is, amongthe measured characteristics by far the strongest among Greek professionals(sig. 0.00).

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

151

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

12/22

A c h

i e v e m e n t

A f l i a t i o n

P o w e r

S o c i a l r e s p o n s

i b i l i t y

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

M e a n

2 . 8 7

5 . 8 7

1 . 5 1

1 . 4 8

3 . 0 8

2 . 8 3

6 . 7 8

5 . 6 4

M e d

i a n

2 . 8 0

5 . 7 0

0 . 9 5

7 . 0 0

2 . 6 7

1 . 9 3

5 . 9 1

5 . 5 0

M i n i m u m

0 . 0 0

0 . 9 9

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 0 0

0 . 4 2

0 . 0 0

M a x

i m u m

8 . 3 9

1 1 . 2 4

1 2 . 0

4

8 . 7 5

1 6 . 3 0

1 2 . 3

7

1 4 . 7

1

1 3 . 6

2

9 5 p e r c e n t c o n

d e n c e i n t e r v a l

f o r m e a n

1 . 9 0

- 3 . 8

3

4 . 5 2 - 7 . 2

2

0 . 5 5

- 2 . 4

8

0 . 4 2

- 2 . 5

4

1 . 6 1

- 4 . 5

4

1 . 3 3

- 4 . 3

3

5 . 4 2

- 8 . 1 3

4 . 2 0

- 7 . 0

9

K - S

Z

1 . 7 4 5

0 . 5 0 8

0 . 3 9 5

0 . 7 6 6

S i g n

i c a n c e

0 . 0 0 5

0 . 9 5 9

0 . 9 9 8

0 . 6 0 1

N o t e s :

P =

P r o

f e s s

i o n a

l ; E =

E n t r e p r e n e u r

Table III.Descriptive statistics forachievement andsignicance tests of differences, afliation,power motives and socialresponsibility

LODJ26,2

152

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

13/22

Wilcoxon signed rankstest

Ranks n Mean rankSum of ranks Z

Asymp. sig.2-tailed

EntrepreneursAfliation achievement Negative a 18 10.17 183.00

Positive b 1 7.00 7.00Ties c 1Total 20 2 3.541 0.000

Power afliation Negative d 3 6.00 18.00

Positive e 10 7.30 73.00Ties f 7Total 20 2 1.922 0.055

Power

achievement Negativeg

17 9.18 156.00Positive h 1 15.00 15.00Ties i 2Total 20 2 3.070 0.002

Social responsibility achievement Negative j 10 8.20 82.00

Positive k 7 10.14 71.00Ties l 3Total 20 2 0.260 0.795

Social responsibility afliation Negative m 0 0.00 0.00

Positive n 18 9.50 171.00Ties o 2Total 20 2 3.724 0.000

Social responsibility power Negative p 4 8.25 33.00

Positive q 15 10.47 157.00Ties r 1Total 20 2 2.495 0.013

ProfessionalsAfliation achievement Negative a 15 10.27 154.00

Positive b 4 9.00 36.00Ties c 8Total 27 2 2.374 0.018

Power afliation Negative d 7 9.29 65.00

Positive e 16 13.19 211.00Ties f 4Total 27 2 2.220 0.026

Power achievement Negative g 13 10.23 133.00

Positive h 9 13.33 120.00Ties i 5Total 27 2 0.211 0.833

( continued )

Table IV.Within-group

comparisons of motivesand social responsibility

(ranks test)

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

153

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

14/22

Discriminant analysis. Furthermore, in order to assess how well the disposition of obligation and the motive of achievement can discriminate entrepreneurs from

professionals we performed discriminant analysis using the stepwise method. Thediscriminant function is based on linear combinations of the predictor variables thatprovide the best discrimination between the groups. As expected from the previousresults, only the variables of obligation and achievement contributed signicantly tothe model, while the rest of the variables stayed out in the step-wise process.

Since we had to discriminate between two groups only, professionals andentrepreneurs, the procedure generated one discriminant function, that is a functionthat discriminated the two groups. Parenthetically, it should be mentioned that formore than two groups discriminant analysis generates a number of functionsdepending on the number of groups to be discriminated. As shown in Table V thevariable of achievement motive (Wilks Lambda statistic 0.752, Exact F statistic 14.861, Sig. 0.000) and the variable of internal obligation (Wilks

Lambda statistic 0.672, Exact F statistic 10.754, Sig. 0.000) contributesignicantly to the discriminant function.

Wilcoxon signed rankstest

Ranks n Mean rankSum of ranks Z

Asymp. sig.2-tailed

Social responsibility achievement Negative j 3 10 30

Positive k 23 13.96 321.00Ties l 1Total 27 2 3.695 0.000

Social responsibility afliation Negative m 0 0.00 0.00

Positive n 25 13 325Ties o 2Total 27 2 4.372 0.000

Social responsibility power Negative p 2 24.50 49.00

Positive q 25 13.16 329.00Ties r 0Total 27 2 3.363 0.001

Notes: aAfliation , achievement; bAfliation . achievement; cAchievement afliation; dPower, afliation; ePower . afliation; f Afliation power; g Power , achievement; hPower .achievement; iAchievement power; j Social resp. , achievement; k Social resp, . achievement;lSocial resp. achievement; m Social resp. , afliation; nSocial resp. . afliation; o Social resp. afliation; p Social resp. , power; q Social resp . power; r Social resp. powerTable IV.

Step Entered Statistic F statistic Sig.

1 Achievement motive 0.752 14.86 0.002 Obligation disposition 0.672 10.75 0.00

Table V.Discriminant analysis:stepwise statistics variables entered

LODJ26,2

154

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

15/22

The discriminant power of the function is 81 per cent. (Table VI). That means that thediscriminant function based on the linear combination of the two variables classied 81per cent of the cases correctly. In other words, the disposition of obligation and themotive of achievement were able to classify 22 out of the 27 professionals to their groupwhile they misclassied ve professionals to entrepreneurs. Also, these two variablesclassied correctly 16 out of the 20 entrepreneurs while they misclassied four of themto the group of professionals.It appears from Table VI that only 19.1 per cent of the original grouped cases were notcorrectly classied. Those correspond to nine companies, ve entrepreneurial and fourprofessional out of the total 47. In other words, ve actually entrepreneurial companieswere predicted to be professional and four actually professional were predicted tobelong to the entrepreneurial group.

The interviews of those outliers were carefully studied and it came up that theyshared certain attributes, namely:

. In the case of the professional companies, wrongfully predicted to be

entrepreneurial, in three out of the four cases, the CEO interviewed had begunworking in the company when very young, had spent more than a decadeworking for the company and had taken up high responsibility posts earlyduring his career in the company. Consequently, we could assume that theseprofessional CEOs seem to consider the company they work for, as their owncompany, and, therefore, present characteristics similar to the ones of entrepreneurs.

. In the case of the entrepreneurial companies, wrongfully predicted to beprofessional, all of the ve CEOs interviewed either belonged to the secondgeneration of the family business or had bought out an already existingcompany, rather than establishing the company from scratch. Again, we couldassume that these entrepreneurs are somehow at a distance from theircompany and that may be the reason that they present characteristics differentfrom the other entrepreneurs and more similar to the professional CEOs.

Factor analysis. Another approach taken to explore possible differences amongprofessionals and entrepreneurs is factor analysis. Although, factor analysis, per se, isnot a comparative method, it can be used in an exploratory way to generate hypothesesregarding correlational mechanisms. Utilizing exploratory factor analysis for the samevariables in two different groups of cases in this study professionals andentrepreneurs we can explore possible differences in the ways variables areinterrelated between the different groups of cases.

Predicted group membershipProfessional Entrepreneurial Total

Count Professional 22 5 27Entrepreneurial 4 16 20

Percentage Professional 81.5 18.5 100Entrepreneurial 20.0 80.0 100

Note: 80.9 per cent of original grouped cases correctly classied

Table VI.Discriminant analysis:

classication results

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

155

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

16/22

Factor analysis performed for the group of professionals (Table VII) revealed that theeight variables used in the analysis are grouped into three factors. The rst factorloads mainly on the variable of self-judgment from the ve indices of responsibility(0.925) and on the variable of the afliation motive (0.926); we call this factor sensitivityfactor. It shows that professionals who tend to have high-level afliative motives alsotend to be more self-critical. We would expect the variable of concern for others to loadon the sensitivity factor, but it did not.

The second factor loads on the variables of moral standard (0.789) and of concernfor consequences (0.663) among the indices of social responsibility. We call this factormoral conduct. It shows that those among professionals who are concerned about theconsequences of their own actions are also concerned with the moral standards

The third factor loads on concern for others (0.692) and obligation (0.652) among theindices of responsibility and on the variable of the power motive, (0.617). We call itpower factor. It shows that the professional CEOs who show high levels of impact onothers also show a higher tendency to help others, as well as a higher tendency to actbecause of an internal locus of control. The motive of achievement does not load on anyof the three factors. This means that achievement for professionals variesindependently of the other characteristics used for this analysis.

With regard to the group of entrepreneurs, factors analysis revealed three factors aswell. However, the components of the factors in the case of entrepreneurs are quitedifferent (Table VIII). The rst factor loads on afliation (0.895) and self-judgment

Factors1 2 3

Professionals Sensitivity Moral conduct Power

Afliation motive 0.926 2 0.162 0.009

Self-judgment responsibility 0.925 0.001 2 0.154Moral standard responsibility 0.003 0.789 2 0.007Concern for consequences responsibility 0.001 0.663 0.006Achievement motive 2 0.120 0.406 0.002Concern for others responsibility 0.409 2 0.217 0.692Internal obligation responsibility 2 0.339 0.003 0.652Power motive 2 0.166 0.187 0.617

Table VII.Factor loadings for thegroup of professionals

Factors1 2 3

Entrepreneurs Sensitivity Locus of control Strive for success

Afliation motive 0.895 2 0.197 0.244Concern for others responsibility 0.877 0.119 2 0.210Self-judgment responsibility 0.584 2 0.577 0.256Internal obligation responsibility 0.008 0.818 2 0.001Concern for consequences responsibility 0.000 0.787 0.001Standard responsibility 2 0.241 0.256 0.009Power motive 0.009 0.199 0.898Achievement motive 0.001 2 0.335 0.771

Table VIII.Factor loadings for thegroup of entrepreneurs

LODJ26,2

156

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

17/22

(0.584), as it was in the case of professionals, but it also loads on concern for others(0.877). We call this factor sensitivity factor as well. The sensitivity factor is morecomplete in the case of entrepreneurs, because, as was expected, it includes the variableof concern for others. This means that entrepreneurs who show afliative motives forothers are also concerned for others and are more self-critical.

The second factor loads on obligation (0.818) and concern for consequences (0.787),but it also loads on self-judgment ( 2 0.577). We call this factor locus of control. It showsthat entrepreneurs who act because of an internal feeling of obligation also are moreconcerned for the consequences of their actions and are less self-critical. We assumethat because of this internal locus of control, these entrepreneurs tend to be lessself-critical.

The third factor among entrepreneurs loads clearly on achievement (0.771) andpower (0.898) motives. It shows that for entrepreneurs achievement and power are twoclosely related indicators. Finally, the variable of moral standards does not loadsubstantially on any of the three factors. This means that, moral standards forentrepreneurs vary independently of the other characteristics used in this analysis.

DiscussionThe present study, based largely on McClellands theoretical framework on leadershipeffectiveness in general and on entrepreneurial effectiveness in particular (1975, 1985,1986), and being the rst empirical study of this type in the milieu of Greek businesses,described and compared entrepreneurial and professional CEOs. It drew on 47 content-analysed interviews with Greek entrepreneurial and professional CEOs and itcompared professional and entrepreneurial CEOs on eight indicators: Those were threemotives, achievement, afliation and power, and ve indicators of social responsibility,that is, moral-legal standards, sense of obligation, concern for others, concern forconsequences of ones own actions and self-judgment.

Apart from descriptive statistics and normality tests on all variables, all thevariables have been compared with one another for each group of respondents. For thegroup of professionals, social responsibility proved to be the strongest variable,followed by power and achievement motivation, while, for the group of entrepreneurs,achievement is the strongest variable, followed by social responsibility. Furthermore,discriminant analysis was conducted, in order to establish which predictor variablesprovide the best discrimination between the two groups. It came up that there are twodiscriminant factors, achievement motivation and obligation disposition, at an 81 percent discriminant power. Finally, factor analysis was conducted in order to explorepossible differences among professionals and entrepreneurs. A total of three factorswere identied for each group. For the group of professionals, however, power was

combined with concern for others and obligation, while for the group of entrepreneurs,with achievement.

Initial hypothesesH1. Our hypothesis on the difference in achievement motivation among entrepreneursand professional CEOs was conrmed and achievement was found to be adiscriminating factor among the two groups. Entrepreneurs score higher on thismotive. This nding is in accordance with previous research stating achievement as a

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

157

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

18/22

primary characteristic of entrepreneurs (McClelland, 1986; Hisrich et al., 1996; Orhanand Scott, 2001).

H2. Our second hypothesis was also conrmed, since power was not found to bedifferent among the two groups, while achievement was found to be higher for thegroup of entrepreneurial CEOs. Effective leadership requires high level of power andmoderate level of achievement compared to power (McClelland, 1975, 1985). In the caseof Greek CEOs, among both entrepreneurs and professionals, the motive of achievement is stronger than the motive of power. However, in accordance with ourhypothesis, entrepreneurs score signicantly higher on achievement thanprofessionals. We found that the difference between power and achievement (powerachievement) is signicantly bigger but negative, for the entrepreneurs and smaller butnegative and not signicant for the professionals. So, the data are in the same directionwith the logic of our hypothesis.

H3. According to the third hypothesis, entrepreneurs were expected to score higheron the motive of afliation than professionals. The ndings did not support ourhypothesis. Although it has been established in the literature that the afliation is veryprominent among entrepreneurs, it was not found to be a motive that woulddifferentiate at signicant level entrepreneurs from professionals. The assumptions very common in Greece that some people choose to become entrepreneurs in order tooffer some employment security to their relatives or leave something for theirchildren were not supported. Furthermore, afliation was found to be a weak motivefor Greek CEOs in general, that is, both entrepreneurs and professionals.

H4. With regard to the ve indicators of social responsibility, we expected,according to our fourth hypothesis, entrepreneurs to score higher on concern for othersfor the same reason that they would score higher in afliative motive. Contrary to ourhypothesis, entrepreneurs were not proved to be different from professionals inconsidering others.

H5. To the extent that entrepreneurs are described as individuals with high need forautonomy, independence, personal deviance, and risk taking propensity (Cromie, 2000;Sexton and Bowman, 1985), we expected them, according to our fth hypothesis, toscore lower on the indicator of internal obligation. Indeed, our data showed thatprofessional CEOs have a tendency to refer to obligations more often thanentrepreneurs. Despite the particular difference on internal obligation, both groups of Greek CEOs score very high on overall social responsibility.

Discriminant analysis outcomes: achievement and obligationOverall, the motive of achievement and the indicator of obligation are points that candifferentiate successfully the groups with a probability over 80 per cent. The twovariables failed to discriminate two groups of cases that showed characteristics of the

opposite group:(1) Second-generation entrepreneurs, that is, entrepreneurial CEOs, who, however

were not the founders of the company, but kids or nephews who succeeded thefounder.

(2) Professional CEOs who had spent a decade or more in their company, or evenhad started their career in their company and assumed characteristics of entrepreneurial CEOs. Perhaps, they felt some sort of ownership to thecompany.

LODJ26,2

158

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

19/22

Factor analysis outcomesThe exploratory factor analysis of the eight variables revealed some further interestingdifferences between entrepreneurs and professionals. For professionals, factor analysisidentied three factors: sensitivity, moral conduct and power. Factor analysis forentrepreneurs, also revealed three factors, but of different consistency: sensitivity,locus of control and strive for success.

Professionals who have stronger afliative motives also tend to be more critical withthemselves; this is a combination that connotes rather sensitive criteria of conduct. Thesame factor is found among entrepreneurs, but in a more complete consistency; thesensitivity factor for them includes their concern for others. For professionals, concernfor others groups with their tendency to act out of internal obligation and with theirdesire to inuence others. This is a combination of characteristics that underlinesprofessional conduct. Perhaps the latter effect could be attributed to the reportedmanagers uidity in changing from a superior to a subordinate role (Kets de Vries,1985, p. 161), which entails the motivation for power to be coupled with higher concernfor others, mostly their subordinates, and higher obligation.

The factor of moral conduct results for professionals from the combination of moralstandards and concern for consequences of their actions. Professionals who care aboutthe impact their actions tend to appeal to morality. However, for entrepreneurs concernfor their own actions does not group with morality; it groups with the sense of internalobligation to act in a certain way and with self-criticism. Entrepreneurs who care aboutthe impact of their actions, act out of internal forces and tend to be lessself-judgmental, probably because they feel they do things right. This combination of characteristics is the essence of internal locus of control. Finally, the last factor forentrepreneurs reveals that success and power are inextricably connected.Entrepreneurs who look for higher levels of achievement tend to exercise theirpower at the maximum. So, the power motive and the achievement motive actsimultaneously and in the same direction for entrepreneurs, while this is not the casefor professionals. We call this combination strive-for-success factor.

Conclusions future researchTo sum up, it could be sustained that achievement motivation and obligation-responsibility are the two factors distinguishing entrepreneurial from professionalCEOs. That is, entrepreneurial CEOs are more motivated by achievement, andachievement motivation is connected to power motivation, while for professional CEOs,responsibility is the stronger variable, which also is connected to power motivation.

Successful professional CEOs, show a high sense of obligation and powermotivation.They t the model-type of the institutional manager, as conceptualised byMcClelland and Burnham (1976); this type has been described as being mostly

Institutionalmanager

Greek professionalCEOs

Greek entrepreneurialCEOs

Power motive High High ModerateAchievement motive Moderate Relatively high HighAfliation motive Low Low LowResponsibility High High Moderate

Table IX.Motives and

responsibility of idealinstitutional manager

and of Greek CEOs

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

159

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

20/22

interested in power, showing, however a high sense of responsibility towards hiscompany. According to McClelland, this is the most effective type of manager. Theonly difference among McClellands institutional manager and the prole of theprofessional CEOs of our sample is the latters relatively high achievement motivation.This could be viewed as a common element of Greek managers, which is also true forentrepreneurs, who also exhibit very high though much higher than professionals achievement motivation.

Entrepreneurial CEOs in our sample show a different prole, with high achievementmotivation, coupled with moderate power motivation. Consequently, they do not t theinstitutional manager type. A question to be asked is whether the role of entrepreneurial CEO requests different characteristics than the effective leadershipprole of McClellands institutional manager in Greece. And, if so, it would be usefulto verify the motive and responsibility characteristics of successful entrepreneurialCEOs that were identied in the current paper. Table IX shows the differences inmotives and responsibility disposition between McClellands institutional managerand the Greek professional and entrepreneurial CEOs.

Moreover, it would be interesting, not only to build on the ndings of the currentpaper, on the motivation and responsibility disposition of entrepreneurial andprofessional CEOs, but also to relate the motives and responsibility disposition of theCEO with the organisational culture, as well as with the nancial, commercial or othersuccess indicators of their company.

One of the major implications deriving from the identied characteristics of successful entrepreneurial and professional CEOs, has to do with training of youngleaders. Responsibility, for example, which was found to characterise successfulprofessional CEOs should become a major educational target to be developed byBusiness Schools and professional training offered to junior managers. Furthermore, itwould be useful to develop the power motive among young managers-to-be in BusinessSchools, while the achievement motive should be developed in all educational levels, inorder to enhance entrepreneurial spirit.

Planned future research by the authors of this paper will test this model in thecontext of Greek culture, both societal and organizational. Overall, Greeks arecharacterized by a desire to advance socially and secure social recognition; but, at thesame time, research has shown that they believe that their society is not performanceoriented (Papalexandris, 2003). Could the preoccupation with overachievement explainlower levels of performance in Greek society and, perhaps, in Greek organizations? Aforthcoming analysis of empirical data collected under the GLOBE project may shedsome light to this Greek paradox.

References

Alstete, J.W. (2002), On becoming an entrepreneur: an evolving typology, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research , Vol. 8 No. 5, pp. 222-34.

Barrow, C. (1993), The Essence of Small Business , Prentice-Hall, Hemel Hempstead.Bosma, N., van Praag, M. and de Wit, G. (2000), Determinants of successful entrepreneurship,

Research Report 0002/E , SCALES (SCientic AnaLysis of Entrepreneurship and SMEs),programme nanced by the Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs, The Hague.

Brockhaus, R.H. (1980a), Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 509-20.

LODJ26,2

160

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

21/22

Brockhaus, R.H. (1980b), Psychological and environmental factors which distinguish thesuccessful from the unsuccessful entrepreneur: a longitudinal study, Academy of Management Proceedings , Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 368-72.

Cantillon, R. (1931), Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Ge ne ral , H. Higgs, Macmillan, London.

Carland, J., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. and Carland, J.A. (1984), Differentiating entrepreneurs fromsmall business owners: a conceptualization, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 9 No. 2,pp. 354-9.

Collins, O.F., Moore, D.G. and Unwalla, D.B. (1964), The Enterprising Man , MSU BusinessStudies, East Lansing, MI.

Cromie, S. (2000), Assessing entrepreneurial inclinations, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 7-30.

Cromie, S., Callaghan, I. and Jansen, M. (1992), Entrepreneurial tendencies of managers:a research note, British Journal of Management , Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1-5.

Gartner, W. (1989), Who is an entrepreneur? Is the wrong question, Entrepreneurship Theoryand Practice , Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 47-68.

Hisrich, R.D. and Brush, C.G. (1985), The Woman Entrepreneur: Characteristics and Prescriptions for Success, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

Hisrich, R.D., Brush, C., Good, D. and De Souza, G. (1996), Some preliminary ndings onperformance in entrepreneurial ventures: does gender matter?, Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research , Babson College, Wellesley, MA.

Hornaday, J.A. and Aboud, J. (1971), Characteristics of successful entrepreneurs, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 141-55.

House, R.J. (1998), A brief history of GLOBE, Journal of Managerial Psychology , Vol. 13 No. 3-4,pp. 230-41.

Kets de Vries, M. (1985), The dark side of entrepreneurship, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 63No. 6, pp. 160-7.

Kirzner, I.M. (1981), Uncertainty, discovery and human action, paper presented at the NewYork University Liberty Fund Centenary Conference on Ludwig von Mises, New York,NY, September.

Kisfalvi, V. (2002), The entrepreneurs character, life issues, and strategy making: a eld study, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 489-518.

Knight, F.H. (1921), Risk, Uncertainty and Prot , Houghton Mifin, New York, NY.

McClelland, D.C. (1961),The Achieving Society , Van Nostrand Rinehold, Princeton, NJ.

McClelland, D.C. (1986), Characteristics of successful entrepreneurs, Keys to the Future of American Business, Proceedings of the 3rd Creativity, Innovation and EntrepreneurshipSymposium , US Small Business Administration and the National Center for Research inVocational Education, Framingham, MA (addendum, pp. 1-14).

McClelland, D.C. and Burnham, D.H. (1976), Power is the great motivator, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 100-10.

McClelland, D.C., Atkinson, J.W., Clark, R.A. and Lowell, E. (Eds.) (1953), The Achievement Motive, Appleton-Century-Crofts, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Maccoby, M. (1976), The Gamesman , Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York, NY.

OECD (2002a), Economic Surveys: Greece , OECD Economic Surveys, Paris.

OECD (2002b), Small and Medium Enterprise Outlook , OECD, Paris.

Entrepreneurialand professional

CEOs

161

-

8/9/2019 Entrepreneurial and Professional CEOs - Differences in Motive and Responsibility Profile

22/22

Orhan, M. and Scott, D. (2001), Why women enter into entrepreneurship: an explanatory model,Women in Management Review , Vol. 16 No. 5, pp. 232-43.

Papalexandris, N. (2003), From ancient myths to modern realities, The GLOBE Anthology Book.

Ratnatunga, J. and Romano, C. (1997), A Citation Classics analysis of articles in contemporarysmall enterprise research, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 197-212.

Say, J.B. (1845), A Treatise on Political Economy , Grigg & Elliot, Philadelphia, PA.Schumpeter, J.A. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development , Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA.Sexton, D.L. and Bowman, N. (1985), The entrepreneur: a capable executive and more, Journal

of Business Venturing , Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 129-40.Weber, R.P. (1985), Basic Content Analysis , Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.Winter, D.G. (1991), Measuring personality at a distance: development of an integrated system

for scoring motives in running text, in Stewart, A.J., Healy, J.M. and Ozer, D.J. (Eds), Perspectives in Personality: Approaches to Understanding Lives , Jessica Kingsley, London,

pp. 58-89.Winter, D.G. and Barenbaum, N.B. (1985), Responsibility and the power motive in women and

men, Journal of Personality , Vol. 53 No. 2, pp. 335-55.

Further readingHisrich, R.D. (2000), Can phychological approaches be used effectively? An overview,

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 93-6.House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S.A., Dorfman, P.W., Javidan, M., Dickson, M. and

Gupta, V. (1999), Cultural inuences on leadership and organizations: project GLOBE, inMobley, W. (Ed.), Advances in Global Leadership , Vol. 1, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.

Observatory of European SMEs (2002), SMEs in Europe , including a rst glance at EU candidatecountries, No 2, Ofce for Ofcial Publications of the European Communities,Luxembourg.

Papalexandris, N. (1999), Understanding and Measuring Organizational Culture , DanskManagement Forum, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, August.

LODJ26,2

162