Entertaining the Forgotten - Cambridge

Transcript of Entertaining the Forgotten - Cambridge

144TDR 65:1 (T249) 2021 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1054204320000131© The Author(s) 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press for Tisch School of the Arts/NYU

Entertaining the ForgottenSouthern Governors and the Performance of Populism

Weston Twardowski and Gary Alan Fine

On a flag-bedecked platform, before a packed audience spilling onto the stage, a tall man in a trademark red tie stood before a microphone. Tens of thousands had turned up to hear him speak truth to power. A “man of the people,” he railed against the establishment, decried the biased media who smeared his name, preached how tax cuts would bring back jobs to the for-gotten men who wanted work, and promised the abolition of the interfering and unnecessary bureaucracy of the government. Long before Ronald Reagan quipped, “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help,” or Donald Trump promised the crowds at his rallies that “we’ll take our country back,” Southern popu-lists were leading rallies that interwove racist rhetoric with antiestablishment sentiment to pro-pel themselves into powerful state offices. Indeed, while the man in the red tie may call to mind President Trump at a political rally, it was in fact a much earlier instance of American populism. The year was 1932, and the man was the next governor of the state of Georgia: Eugene “Gene” Talmadge (Logue 1981:207–09).

Perform

ance of Populism

145

In the South during the New Deal era populist, demagogic politicians generated hagiocratic personas to build loyal audiences through dynamic and highly staged political rallies. Three Jim Crow–era politicians — Talmadge of Georgia, Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, and Huey P. Long of Louisiana — who perfected their populist showmanship exemplify how populism became performative. Twentieth-century Southern politics was typified by bombastic, overtly rac-ist figures who, relying on a recurrent, highly theatricalized, homey style of performance, built support in rural districts to win elections. The performative populism of these particular politi-cians drew large audiences by delivering highly entertaining, theatricalized rallies built around their manic energy, coarse humor, and an “I am like you” dynamism. At these rallies they lever-aged a mix of racist rhetoric, class division, and crude insults of their rivals to create the typical “us vs. them” model of populist politics that helped them build loyal political bases. Talmadge and Bilbo are best remembered today for their virulently racist politics and personal beliefs, and though Long’s views on race were more nuanced, he also relied on racial animus (especially in his later career).

The performance style that emerged from this period is central to a collective image of the American South, particularly in the first 60 years of the 20th century. Indeed, the theatricalized nature of Southern politics was so recognizable that by the 1940s the figure of the loquacious Southern politician had become a mainstay of popular culture, appearing in the 1947 musical Finian’s Rainbow, the long-running 1930s–’40s Fred Allen Radio Show, Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 novel All the King’s Men (which inspired two films, in 1949 and 2006), and arrived in car-toon form in 1946 with the bloviating rooster of Looney Tunes’ Foghorn Leghorn who was featured in 29 films and is still widely available on the internet. The figure of the Southern pol-itician reflected the educational limits of the rural, white, Southern electorate. Politicians devel-oped their theatrical style to direct attention away from the impact of their policies on those whose votes they courted.1

In the South, and particularly the Deep South, white politicians publicly raised issues of race less to address substantive policy than to raise the emotional heat among their audiences. For instance, in the 1936 Georgia senatorial election, Talmadge and his opponent Richard Russell were both fully committed to maintaining white supremacy. Talmadge, however, turned to racial expletives and insults far more than Russell, who shied from talking race publicly (Mead 1981:40). The suppression of the black vote during the Jim Crow era meant that these

Weston Twardowski is a candidate in the Interdisciplinary PhD in Theatre and Drama program at Northwestern University. He holds BAs from Louisiana State University in History and Theatre Performance and an MA from the University of Houston in Theatre Studies. His dissertation, “‘They’re Tryin’ to Wash Us Away’: Performance, Civic Identity, and the New New Orleans,” focuses on the role of performance in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. [email protected]

Gary Alan Fine is the James E. Johnson Professor of Sociology and former Director of the Interdisciplinary PhD in Theatre and Drama at Northwestern University. He previously served as Department Head of Sociology at the University of Georgia. He is the author of Difficult Reputations: Collective Memories of the Evil, Inept and Controversial (2001). His current research is an ethnographic study of professional historians and history buffs whose interest is the American Civil War. [email protected]

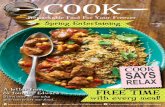

Figure 1. (facing page) Eugene Talmadge speaks to a crowd of supporters in Gainesville, Georgia, during his 1946 Gubernatorial Campaign against Ellis Arnell. (Photo courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Special Collections and Archives, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection)

1. To some extent the stereotypical character may have emerged from the “othering” of white Southerners by those with different regional, class, or political backgrounds.

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

146

2. This is an area which would benefit from further historical study, as there are doubtless more examples of black politicians beyond the few studied so far.

politicians could focus on whites. Prior to World War II, black voter registration in the South was an abysmal 3%, and those registered still met obstacles on their way to and at the polls should they attempt to exercise their right to vote (Beyerlein and Andrews 2008:68). This situa-tion didn’t improve until the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

None of the three states examined here had elected a Republican governor since the end of the reconstruction era. Gubernatorial elections essentially functioned at the primary level as the Democratic nominee was virtually assured victory. While black politicians began to find some successes during the 1930s in the North, generally for party leadership roles or positions of power within city government, it would take the sustained activism efforts of the 1950s and 1960s to bring these kinds of changes to the South (Sitkoff 1978:88). There were a few attempts by black political groups to form break-off independent Republican parties (because the Republican party refused to allow black participation), notably in Arkansas and Virginia, how-ever black campaigns were rare, and success virtually nonexistent (Harold 2016:55–58).2

The theatricality of the Democratic campaign events — the careful coordination of rheto-ric (often racist humor and antiblack screeds), delivery style, costumes, set, and sound — built the popularity of these strong-arm politicians for several reasons having to do with Southern cultural traditions, the rurality of the electorate, the racism of the white population, and the sharp divisions between rich and poor. We see these elaborate rallies throughout the 20th cen-tury: in early decades, there were the campaigns of such “populist” figures as J.K. Vardaman of Mississippi (“the White Chief”), “Our” Tom Heflin of Alabama, “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman of South Carolina, and Tom Watson of Georgia; later figures like George Wallace and Lester Maddox continued this legacy. These politicians emerged from a tradition of populism, despite voting records that did not usually reflect populist values. This strain of populist leader, built from the “everyman dynamism” persona, carries over into the present, perhaps most clearly by Donald Trump who likewise has built much of his political success on a strategy of political ral-lies as entertainment (Bender 2019).

Common tactics explain how these populists strove to unite rural white voters despite the distinct political cultures of their various states. There are multiple elements that are crucial to the success of these three populist politicians, all centered around the carnivalesque atmo-sphere of their rallies. As Mikhail Bakhtin articulates, “carnival celebrated temporary libera-tion from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions” ([1968] 1984:10). Indeed, the antielite and antiestablishment rhetoric and personas used by these politicians at their rallies served as a direct (imagined) rejection of the ruling order (political, educated, wealthy, and urban). The ral-lies functioned for the participants as a utopian performative, to use Jill Dolan’s term (2005:5). Those attending these events collectively imagined a new world order, one that would ennoble and empower their rural, white identitarian body.

Critical to the success of these rallies was immediate intelligibility: to be understood espe-cially by voters with a limited education. This was accomplished not merely through rheto-ric, but through presentation manner and style. A second element was the construction of the campaign event in time and space. In order to draw — and then satisfy — a crowd, the politician would privilege his showmanship over the substance of what he proposed. Not only were these men known for their distinctive firebrand speeches, but they also added carnivalesque elements that often included other speakers, musicians, and free food. The tremendous amounts of food and gaudy, highly decorated stages were a major draw for the impoverished in the Depression. Larger events were often scheduled for weekends (sometimes deliberately after church so groups could go directly from service to the rally); however, the politicians campaigned (and

Perform

ance of Populism

147

hosted numerous rallies a day) 6–7 days a week, so decidedly not solely on days off. Excited by advertisements in local papers and radio programs — as well as word-of-mouth notifica-tions through local political groups — rallies represented time off from labor when the white community could come together in civic celebration. Finally, after creating a unified collective presence, these politicians called out clear enemies. Racism drew distinctions between their sup-porters and the poor blacks with whom they shared many economic circumstances. The poli-ticians castigated “city politicians” and “educated elites,” accentuating divides between faithful rural voters and the city-dwellers who rarely supported them. These performances served three purposes: gathering large numbers of people, feeding them literally and with rhetoric, and lift-ing their spirits. Finally, each politician established a carefully controlled underdog narrative presenting himself as a fighter for the people, standing against the government, the powerful, educated intellectual elites, rapacious minorities, and a biased urban press — in today’s terms, “the deep state” and the “media.”

There has been an explosion of research into populism since the 1990s. Much of it grows out of ideational and political-strategic thought (Kaltwasser et al. 2017:11–12). What has only recently been gaining attention is the sociocultural approach to populism, which not only addresses the ideology, but also allows for a richer understanding of how group identities are formed. The analysis of Ernesto Laclau is a touchstone for understanding not only group iden-tification, but also how social tension demands populist icons to mitigate large, disparate polit-ical entities (Laclau 2005). Populism is, in Paul Taggart’s phrasing, “of the people but not of the system” (1996:32). While theatre and performance studies have long noted the complex relationship between politics and performance, the reliance of populist politicians on specific, recognizable tropes (used to entertain) remains underexplored (Fenno 1978). Scholars such as Suk-Young Kim (2010) and Diana Taylor (1997) have thoroughly examined how states utilize performance to maintain control and even oppress their citizens. Likewise, political scientists Julia Strauss and Donal Cruise O’Brien argue that politics may be read through a dramaturgi-cal lens, pointing to trials and elections as instruments of state theatrics (2007). However, only recently have scholars such as Benjamin Moffitt (2016) and Angela Marino (2018) begun to directly engage the critical role performance plays in contemporary populist politics.

In crucial ways, a populist politician must deal with identity markers that are simultaneously at odds with each other: the populist is one of the people, yet also their leader and must offer a vision of what the followers could be without coming across as better than they. The idea of the politician’s presence is critical here. As Joseph Roach notes “‘it’ is the power of appar-ently effortless embodiment of contradictory qualities simultaneously: strength and vulnerabil-ity, innocence and experience, and singularity and typicality among them” (2007:8). Populists are aspirational figures, viewed as strong (typically in a traditionally masculine fashion), charm-ing, successful, and being “from the same place” as their followers. Oftentimes, contemporary reporting remarks on unappealing physical appearances, noting how the leader’s magnetism more than compensates for this. The use of ennobling monikers serves in this vein. They reflect to their audience a vision of themselves, but distorted, improved, and larger than life. However, in the context that we examine, the promises that the candidate makes are often cynical, not to be enacted when gaining power. After the election, many claims are forgotten, because the rural, impoverished public is no longer the core audience, shoved aside by persons of wealth and power. Of course, power corrupts, and each of the politicians we examine was mired in scandal soon after election, scandals that betrayed their campaign promises of clean government.

Democrats in the Depression era were torn between local issues and the increasing strength of the national party run by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR, with mixed results, sometimes campaigned against Southern candidates who opposed his policies (such as Senators Walter George of Georgia or Ed Smith of South Carolina). This aggravated Southerners who often viewed Roosevelt as an unwelcome and condescending outsider, and despite the popularity of the New Deal, his patrician background — which he tried to mitigate in his appearances — only added to their disapproval (Shannon 1939). The policies of Southern states and the desires of

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

148

3. Roosevelt’s direct engagement in Democratic primaries in the South irked both politicians and locals, and often aided those he openly opposed.

Southern white voters were often at odds with FDR’s domestic policies.3 The distinct roles that the populist politicians played in their home districts and their strength as entertain-ers allowed them to navigate these difficulties. The “Solid South,” which voted overwhelm-ingly Democrat and represented a major voting bloc within the party, had emerged in the wake of Reconstruction after the Civil War. These were white Southerners expressing their rejec-tion of Lincoln’s Republican party. However, as FDR advanced a more racially progressive pol-itics, Southern Democratic party loyalty began a slow, but noticeable, decline (Key 1949:667). Following Lyndon Johnson’s passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond and other leading Southern Democrats aban-doned the party for the GOP, ushering in Richard Nixon’s successful “Southern Strategy.” To this day, the Southern Strategy remains a critical part of the Republican game plan.

Surely, race was, and still is, a major element of Southern politics. The rallies for Talmadge, Bilbo, and Long were segregated spaces; the politicians supported segregation and other rac-ist policies and racist language was a tool of these three and other candidates of the period. Talmadge and Bilbo are most remembered today for their racism, having promoted white supremacy, segregation, or the deportation of blacks. Their reputations are explicitly tied to race (Hughes 1947; Lemmon 1954). Long often avoided overtly racist politics, forgoing racially tinged insults, and never endorsed the Ku Klux Klan. His most obvious segregationist language only emerged when he began campaigning at the national level (Mixon 1981:202). Recent schol-arship on these politicians has done critical work in explicating their history of racial animus. In particular, Michael Fitzgerald’s (1997) and Keisha Blain’s (2018) research on Bilbo details how racist ideology shaped much of his political policymaking in Washington. Likewise, Cal Logue’s (1989) writings on Talmadge’s rhetoric, and Michelle Brattain’s (2001) work exploring his poli-cies as they relate to social welfare and the deliberate exclusion of black citizens help reveal the racial dynamics of Talmadge’s career. Finally, Glen Jeansonne’s (1992) pointed complication of the racial legacy of Huey Long places him in a Southern context: a necessary intervention for a politician who has been widely written about but largely had his use of racism for political gain erased or reduced to only the smallest part of his legacy as a national figure.

Although incorporating the work of other scholars, we also conducted extensive archi-val research. We examined the holdings of the Howard-Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University and the Hill Memorial Library at Louisiana State University where the most extensive collection of materials related to Huey Long and his political career exist. Multiple trips were made to the vast Bilbo collection housed at the Cook Library at the University of Southern Mississippi. The majority of these files had not been previously examined. This research was supplemented by visits to the William F. Winter Archives (the Mississippi State Archives), which provided access to an extensive collection of period newspapers that reported on Bilbo’s campaigns. Research on Talmadge is more difficult because he regularly burned his personal papers (and most of the remainder was destroyed after his death). However, we con-ducted research at the Georgia Archives (housed at the University of Georgia), and worked through contemporaneous Georgia newspapers both electronically and on microfilm (such as the Atlanta Constitution and Talmadge’s personal newspaper, The Statesman).

Huey Long (1893–1935)

Huey Pierce Long Jr.’s hold on Louisiana public memory is unparalleled. In physical mani-festations such as statues, plaques, and buildings bearing his name, as well as ongoing artistic depictions (most famously the novel and film adaptations of All the King’s Men), Long, known as “The Kingfish,” remains the best known, and most divisive, figure in the state’s political history.

Perform

ance of Populism

149

4. Long was expelled after years of rallying students to misbehave and break school rules. His final act of disobedi-ence was to publish a letter attacking his teachers. During the process of his expulsion, he retaliated by generating a petition that ultimately led to the school principal’s firing.

Born in Winnfield in north central Louisiana, Long was a skilled debater and talented student, although he was expelled from his high school prior to graduation (White 2006:8).4 He then spent a few years as a traveling salesman, a profession that allowed him to hone his already keen sense of how to sway people. Though he never attended more than a semester at a university or at Tulane Law School (where he successfully enrolled with-out an undergraduate degree), he successfully petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court to allow him to take the bar exam — and passed. He began his political career in 1918, run-ning, and eventually secur-ing, a position on the Louisiana Railroad Commission (12).

Long remains commonly viewed either as the people’s savior or as a demagogue who would stop at nothing until he had a dictatorial hold on the state. Shortly after his elec-tion as governor in 1928, Long faced an impeachment chal-lenge that heralded a term full of scandals. Despite this, he strong-armed — often through questionable methods — massive reforms to the educational system, public hospitals, state bureaucracy, and, most visibly, Louisiana’s roads and bridges (Brinkley 1982:9). Particularly important to Long was being recognized for his accomplishments. One cannot travel around Louisiana without encountering reminders of his impact, whether in hospitals that bear his name (the Huey P. Long Medical Center in Pineville and Huey P. Long Medical Center at Louisiana State University Shreveport), the Huey P. Long Bridge in New Orleans, or in the innumerable plaques and statues erected to commemorate his legacy at various state buildings (both the State Capital and Governor’s Mansion were built by Long and commemorate him, as well as buildings with commemorative features around LSU’s flagship campus in Baton Rouge). Long yearned for a permanent legacy. Despite this, it is not his institutional accomplishments that have set Long’s legacy, but the intangible element that most defined him: his performa-tive ability. Memories of his radio addresses, his 15-hour Senate filibuster (where he famously recited his gumbo recipe), and his campaign appearances are what concretize Long in the mem-ory of Louisianians (see Haas 1994; Vaughn 1979).

What made this image of Long as speaker so enduring? What about these performances makes them so memorable, echoing into the present? As with other successful Southern politi-cians who achieved populist support by attracting rural white voters, Long performed a “Good Ol’ Boy” character that endeared him to his voters. However, Long broke with other politi-cians on two major counts: first, while Long’s views on race matched the white supremacists of his time, he rarely used racialized language or campaigned on issues of race until his turn to national politics. Long was, unmistakably, racist. He made plain that his election was not going

Figure 2. Senator Huey P. Long tells a joke to an audience of Senate staffers in Washington, DC in 1934. (Photo courtesy of Southeastern Louisiana University, Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, and Fajoni-Lanier I and II Photo Collection, and The Long Family Photo Collection)

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

150

to benefit blacks in the state, regularly attacking opponents who claimed his free textbook pro-gram would extend to black residents ( Jeansonne 1992:269). However, as V.O. Key has noted, given Louisiana’s smaller black population in comparison to Mississippi and Georgia — coupled with the total control the white population maintained over voting in the state — Long, like most of Louisiana’s politicians, didn’t feel the same pressures to make race a foundational part of his platform and political persona ( Jeansonne 1992:272). Second, Long never presented a vision of “the South” or attempted to paint an overly romanticized view of the days gone by antebellum south that he wished to resurrect (Mixon 1981:202). This separated him from those politicians to whom he is most often compared. Whereas other Southern populists relied on an imagined collective memory of the Lost Cause, Long recounted the problems of the present, provided largely progressive solutions, and painted a vision of a rosy future.

Long’s political style is often regarded as a preeminent model of American populism. Michael Lee (2006) outlines a four-pronged system by which populists create groups that will-ingly identify as a collective: first, establish the group through common linkages of morality and character; second, identify those outside the group as enemies preventing success; third, note forms of oppression crafted by the enemy; and finally, offer a revolutionary vision of the future that the collective group may achieve. Lee notes that Long made a deliberate effort to build a unified “people” across class divides. Long’s supporters, more than a geographically bound farming coalition, included middle-class Louisianians as well, and were defined by their iden-tification and hopes to be treated as equal to the local elites. Rhetoricians J. Michael Hogan and Glen Williams suggest that “Long became the voice of the alienated and dispossessed ‘common man’ during the depression” (2004:150). Harold Mixon points to these strategies of community-building when he notes that “Long employed two basic strategies, ‘polarization’ and ‘solidification’” (1981:180). Long’s use of rhetoric to delineate himself and his followers against powerful outside forces was a dominant attribute of his political style.

Figure 3. Governor Huey P. Long addresses a crowd of supporters in 1931 on behalf of his chosen successor for governor, Oscar K. Allen. (Photo courtesy of Southeastern Louisiana University, Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, and Fajoni-Lanier I and II Photo Collection, and The Long Family Photo Collection)

Perform

ance of Populism

151

5. Different newspapers reported different numbers for the rally, with the New Orleans (and Long rival) Times-Picayune claiming it was around 2,500 total (Times-Picayune 1927a). Papers more friendly to Long however were likely to claim the total attendees numbered anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000.

Long set out to be the apotheosis of the Louisiana ethos through several hallmark tech-niques, the first of which was his energetic performance style. While speaking, his whole body rocked with a manic energy, his arms and hands waved, and he punctuated each point or joke with a stroke of the arm. Recalling him in action, Leon Gary, an executive assistant to Long’s Lieutenant Governor Paul Cyr, described his performative style saying, “he had a mannerism of always being in motion. He had a free-wheeling body. Head, hair, arms, shoulders — everything would move in a different direction and he kept the people looking at him, even two hours at a stretch in the hot sun” (Gary 1960). This energy was more than entertainment: it capti-vated his audiences and impressed his determination onto them. Ira Gleason, a young sawmill worker who saw Long speak in his town later recounted that “you can tell a man by his move-ments — I like the way Huey moved, so I told him I was going to do my best to help him get elected” (1956). Film clips demonstrate an ease to his style. He knew how to modulate his pitch and rhythm, and especially his accent, in order to make a joke land. He knew to hold for laughs while speaking, and after making a joke would flash a wide smile to the crowd and share the moment with the audience. When turning his attention to a matter of inequality or his rivals, he would lose his calm as his whole body would rock back and forward, his arms raised above his head only to come crashing down to make clear his meaning. He was able to sway easily, in the course of one speech, between these two poles of easy and friendly funnyman, and passionate and fiercely determined champion of the people.

Long also understood how to set the stage for his speeches. As one of his chief support-ers, Rev. Gerald L. K Smith, wrote: “He recognized the value of entertainment in lacing these sad, enslaved people out of bondage” (1970:86). At his 3 August 1927 campaign kickoff in Alexandria, Louisiana, the campaign carefully crafted the rally’s mise-en-scène. The event was held inside the municipal high school, with a full 3,000 attendees inside and a few thou-sand more outside listening to the day’s speeches via loudspeakers that had been set up for the occasion (Long 1928a).5 New Orleans, Louisiana’s city with the largest economy and popula-tion, famously opposed rural candidates and most of the city’s politicians had a special hatred of Long. Thus, when Long took to the streets of Alexandria to parade into the high school, he chose to march alongside hundreds of New Orleanians who had made the trip to Alexandria specifically for the rally — an embodied claim to his popularity within the city, and ability to win voters from all across the state (White 2006:17). The auditorium had been set up to show-case the range of attendees from around the state, with 150 people representing every county in the state seated onstage (Long 1928a). The rally opened with a military veterans’ brass band that played a mix of classical and popular tunes, and, of course, standard patriotic songs such as “The Star Spangled Banner” and “Dixie” (Long 1928a). Inside the auditorium itself, massive banners hung over the stage proclaiming Long’s slogan, “Every Man a King, but No One Wears a Crown” (Hair 1991:151). The mantra, which was inspired by William Jennings Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech, showed the politician’s purported vision of the world: a vote for Long is a vote for enough, for a better life and a more equal world. It also underscored the idea that Long, of the people and above the people, represented an idea that he alone, the Kingfish, knew how to pull them out of poverty and into a brighter future.

Another aspect of the entertaining quality of Long’s rallies was the campaign’s use of music. While the Alexandria rally featured a full military brass band and choir brought in for the occa-sion, nearly every Long event featured music. There was always at least half an hour of music prior to a rally’s beginning. Oftentimes this was just school bands or local musicians. However, music was so important that later on in his career Long would have booklets made up with “Long Songs” so that even if a local band was unavailable to play before his speech the crowd

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

152

6. A clip of Huey singing the song alongside a musician is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvuSR3HXUlo.

could still join together in song. This collective music-making was critical for creating commu-nitas, to use Victor Turner’s term (1982:45). This sense of collectiveness brought about through embodied participation was necessary to bond his supporters and bring them into a cohesive group supporting him, forming an “us” group as populist figures typically do. The booklet con-tained nine songs. Of these, four (“The Star-Spangled Banner,” “Dixie,” “New Orleans,” and “My Louisiana”) were performed as written. The remaining numbers reworded popular tunes. For instance, the Cole Porter song “Fifty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong” was changed to:

When to the polls we gaily wend our wayThis is what we’re going to sayHere’s another vote for Huey Long!Because he never stoops to subterfugeSend him up to Baton Rouge!Here’s another vote for Huey LongThe time will be short ’fore our guvnor’s LongBecause old Louisiana’s voters can’t be wrongWe’re bound to win because our cause is rightHow we’ll shout on ’lection nightHere’s another vote for Huey Long! (Long 1928b)

By far the most famous “Long Song” was “Every Man a King,” played at every rally and event Long held. The song had a jaunty, simple melody that could easily be learned and remem-bered by those in attendance.6 So popular was the tune that it is still known today, probably best for being featured on the 1974 Randy Newman album Good Old Boys. The lyrics spoke to Long’s vision of raising all people out of poverty:

Every Man a King! Every Man a King!For you can be a millionaire!But there’s something belonging to others,There’s enough for all people to share.When it’s sunny June and December too,Or in the winter time or spring,There’ll be peace without end,Every neighbor a friendWith Every Man a King! (Long 1928b)

Another hallmark of a Long rally was a lineup of prominent speakers to warm up the crowd. Typically, these speakers did two things: highlighted the benefits and reasons to vote for Long and provided lengthy condemnations of his rivals. The speakers tended to be local and state politicians, along with influential businessmen and community leaders. The Alexandria rally opened with remarks from Colonel Swords R. Lee, a popular former state representative, who was followed by John H. Overton, Long’s campaign chair (Long 1928a). Overton used his time to satirically mock Long’s chief opponent, Riley Wilson (Times-Picayune 1927b). This was fol-lowed by a trio of speeches from New Orleans representatives (Nicholas G. Carbajal, J.C. Davey, and Colonel John P. Sullivan) who all castigated New Orleans’s domination of the state. Finally, Clem Ratcliff of Shreveport spoke of why Long would sweep the northern, rural vote before introducing Long’s running mate for Lieutenant Governor, Paul Cyr. Cyr endorsed Long’s platform, and then turned the stage over to Long himself.

Long’s campaign stump speech was the same everywhere, with additions of local refer-ences depending on location. It is a strong example of how he distinguished himself from his rivals. The first words of the speech drew contrast between Long and the Democratic political

Perform

ance of Populism

153

7. Often politicians hosted large barbecues or held day-long presentations with dances and car shows. These ele-ments at the rallies were crucial to why attendees would travel to hear the politicians speak: free food and enter-tainment were rarities for rural voters.

machine of New Orleans, largely run by prominent and wealthy families in the city, known as the “Ring Rule”:

Whatever career I have in this state, and whatever record I may have hereafter, were begun, have been, are now and will forever be against the evils of an Old Ring rule and undemocratic methods which I was reared and taught to be dangerous and an evil influ-ence in the public life of the state. (State Times 1927)

Long went on to recite a litany of rivals he had “always fought” (State Times 1927). He claimed that he and his listeners were deliberately targeted by the political elites, “those of us who have favored the more advanced and enlightened but a less burdened and plundered state have been made the subject of attack and derision for many years” (State Times 1927). He lev-ied his regular refrain against his rivals of “dispensing mush, slush, gush” (Flowers 1956). He called out “big business plutocrats” (Long 1928a). He was particularly fond of insinuating his opponents were overweight from the spoils of their corruption, calling them “trough feed-ers and pie-eaters” (Hair 1991). When insulting his rivals he encouraged his audiences to boo and jeer along with him, developing the popular cry of “Pour it on ’em Huey! Pour it on ’em!” (Shaw 1950:62).

After spending the first 10 minutes of his 50-minute stump speech informing the audi-ence how mistreated they had been by the prevailing powers, Long described how he intended to “uplift the masses” (State Times 1927). His platform consisted of improving education (free textbooks), better care for the disabled and mentally ill, reforming the criminal justice system, improving infrastructure (toll-free bridges, new roads), reforming state bureaucracy, and pre-serving natural resources (State Times 1927). He would often punctuate points with props. A famous example was when decrying the state for too regularly changing school textbooks and thus forcing parents to buy new ones, he’d empty a crate of pristine schoolbooks he claimed had been thrown out by the educational system (White 2006:27).

Both supporters and foes referred to Long’s staging; his speeches were not to be missed (Burns 1985). One of his rivals, Raymond Gram Swing, remarked, “Huey Long is the best stump speaker in America. He is the best political radio speaker [...] give him time on the air and let him have a week to campaign in each state, and he can sweep the country. He is one of the most persuasive men living” (1970:99). The backdrops for these performances varied widely depending on the district.7 When Long appeared in New Orleans, his campaign increased the production values. Ward by ward, Long gave a speech in every part of the city. While Long never expected to win New Orleans (his defeats there were resounding), he took advantage of the city’s entertainment opportunities, which were more plentiful than in the rural parts of the state. Prior to each New Orleans speech local papers ran ads announcing the time and place for the event, adding that there would be music and fireworks (Long 1928a). While only some of Long’s most important campaign speeches (such as the Alexandria kickoff ) were broadcast on the radio, all of his New Orleans rallies were carried by local radio stations. This was the first time such technology was integrated into the state’s politics.

The Kingfish always added local references, extemporizing and throwing in jokes and anec-dotes if he felt he was losing a crowd. He effortlessly mixed the language of a “barefoot country boy” and a well-versed rhetorician. For instance, when speaking to a Catholic audience in south Louisiana he invented a story of how he “would get up at 6 o’clock in the morning on Sunday and hitch our old horse to the buggy and I would take my Catholic grandparents to Mass. I would bring them home, and at 10 o’clock I would hitch up the old horse again, and I would

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

154

8. It is difficult to know how long Bilbo actually remained in college. While his claim to have obtained a degree is verifiably false, there is mixed evidence for how much higher education he completed. His college records indi-cated only a semester, but friends’ accounts seem to suggest two or three years of coursework.

take my Baptist grandparents to church.” Long had neither Catholic relations nor a horse as a child (White 2006:17). On the other hand, at a 1927 rally in Thibodeaux an audience mem-ber, knowing Long’s reputation for broad knowledge of famous speeches and poems, asked him to recite William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus,” which Long promptly did from memory (Long 1928a). One of Long’s favorite appeals to authentic-ity was the dramatic action of throwing away his notes prior to giving his stump speech. Of course, he gave the same mem-orized speech scores of times. While only a few aspects of the speech deviated from his regu-lar remarks, the action made the

entire performance feel spontaneously made for the occasion, as though he were speaking from his heart and not feeding the crowd prepared material.

As a master orator crafting the image of the common man with elevated ability, Long relied on a festive atmosphere, a carnivalesque reimagining of power structures uplifting the disgrun-tled “forgotten man.” He leveraged his rallies into an experience of group identity powerfully linking his electoral success to his audiences by making them feel that they were the winners. Through energized performances demanding enormous stamina — Long often performed nine times a day — the Kingfish mixed his “I’m one of you” identity with myth, elevating the layman into superman. He was a lawgiver who instilled in the voting audience a belief in the possibility of Every Man a King.

Theodore G. Bilbo (1877–1947)

Bilbo, referred to as “The Man,” was raised in Poplarville in the southern part of Mississippi. Like Long, Bilbo had a checkered relationship with education. He began studying at the University of Nashville in 1897, but never graduated.8 Subsequently, he taught math and Latin at different schools in southern Mississippi. He became a rising administrator at Aaron Academy in Hancock County in 1903 but in 1905 he was accused of having an affair with a young student and was dismissed. Following the scandal, Bilbo attended Vanderbilt University Law School from 1905 to 1906, but left prior to completing his JD degree, following accu-sations of cheating. He did, however, succeed in passing the bar and becoming a lawyer in 1906 (Green 1963:13–17). The following year he began his career in politics as a state sena-tor. He was elected governor of Mississippi for the first time in 1915. Despite being branded a corrupt and unintelligent man — accusations that were largely tied to the aforementioned

Figure 4. Governor Huey P. Long speaks to a crowd of supporters in Amite, Louisiana (c. 1930). (Photo courtesy of Southeastern Louisiana University, Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, and Fajoni-Lanier I and II Photo Collection, and The Long Family Photo Collection)

Perform

ance of Populism

155

scandals — Bilbo was elected governor twice (1915 and 1927) and senator three times (1934, 1940, and 1946). He was famous for his oratorical prowess and incendiary rhetoric, explicitly advertising himself as white supremacy’s greatest champion. Not only was Bilbo profoundly racist (his 1947 book is titled Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization), but in his rallies regularly advocated violence against blacks, charging “every red-blooded white man to use any means to keep the n[...]rs away from the polls. If you don’t understand what that means you are just plain dumb” (TIME Magazine 1946). His political strategy, much like Eugene Talmadge’s, was staging rallies where he would build himself up as the strongest defender of segregation and white supremacy — the rural white man’s (white) knight in shining armor.

Bilbo’s succinct platform for his 1911 campaign for Lt. Governor of Mississippi, “True to the People and Death on Crooks,” exemplifies how he fashioned himself throughout his decades-long political career (Bilbo 1911). Early on, Bilbo established his reputation as the people’s will personified. Rather than merely serving the com-mon folk, he reflected their mis-treatment and anger. This was tied to his second objective: to vilify those who stood against him as not merely political rivals but enemies of the state, nam-ing them “crooks” and “liars” (Green 1963:46). He denigrated his opponents with foul language and insults. For example, he referred to John J. Henry, a for-mer warden of the state peniten-tiary whom he believed had written a leaflet attacking him, as “a cross between a mongrel and a cur, conceived in a n[...]r graveyard at midnight, suckled by a sow, and educated by a fool” (41). Bilbo built a base of poor white farmers while attacking more educated urban populations.

From his earliest campaigns, Bilbo was known as a prolific and dynamic public speaker, trav-eling widely, often giving three speeches a day for several days in a row (Crawford 1911). Bilbo extemporized on a set of points adjusting his remarks to the specific concerns of his crowds. A key tool in Bilbo’s arsenal was the press. While Bilbo repelled most urban papers, he realized the importance of winning over the small-town press. For instance, in a 1911 editorial poem, “When Bilbo Came to Town” in the Southern Sentinel (republished in other Mississippi papers), “Dave Lowbrow” mythologized the politician:

I have read how Jove the thunderbolts from Mount Olympus hurled, Which forced the common causers then inhabiting the world, To tuck their tails between their legs and crawl into their holes,With their gizzards all a-trembling and sheer terror in their souls;And on Monday, as I listened to Pearl River’s gifted son, I could see that he was doing just as Jupiter had done — Hurling with the strength of Samson, and David’s skillful aim,Burning shafts of livid lightning which were sure to scorch and maim. A day all should remember, and to posterity hand down, Is Monday, the third of April, when Bilbo came to town. (Lowbrow 1911)

Figure 5. Theodore Bilbo gives a campaign speech in front of supporters in Mississippi. (Photo courtesy of McCain Library and Archives, the University of Southern Mississippi)

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

156

Over several equally long stanzas that consume a half-sheet of newsprint, “Lowbrow” com-pares Bilbo to Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great. The poem emphasizes a dichotomy between the “highbrow” enemies of the people and “rednecks” who are the good, honest, and hardworking citizens of Mississippi.

And the leaders of the caucus that disgraced our grand old state, Would be getting off quite easy if they suffered a like fate;So the “rednecks” and the “cattle” should arise in all their might,And with an avalanche of ballots bury them clear out of sight. [...]The “rednecks” opened up their lungs, and tried to see how hardThey could perforate the atmosphere, with lusty yells and cheers, And when they got a-going seemed wound up a thousand years. (Lowbrow 1911)

This vividly demonstrates the two central pillars of Bilbo’s success: how he aimed to make him-self into a figure of mythic proportion while remaining one of the “rednecks” of his base. Bilbo wanted to be seen as not merely a representative of the people but rather as the personification of their deepest held beliefs and character. Bilbo sought to make the “redneck” an aspirational figure, demonstrating to his followers that the insulting label tacked on them by the elites was in fact a mantle to be taken up proudly. In this, he not only won over his voters, but made them into acolytes to his vision of the world. It was effective, with his supporters bragging, “Bilbo folks don’t change” (Shows 1927).

Bilbo was esteemed for his dynamic oratorical prowess, his evangelical preacher’s style (Hendrix 1981:156–57; Key 1949:242– 43; Zorn 1946:282–83). He eschewed high-toned lan-guage using instead emotional appeals that encouraged the crowd to identify with him. Often beginning his speeches and rallies with religious songs that he led himself, taking out a melo-deon he carried with him, Bilbo assumed for himself the role of preacher (Zorn 1946:283). He exhorted his crowds to respond with cheers of “Hoorah for Bilbo! Amen, Hallelujah!” (Morgan 1985:41). He regularly relied on the rhetorical device of calling his audience “brethren and sis-ters” (Zorn 1946:285). Yet in the same breath he insulted and denigrated his political rivals. One time he referred to an opponent as “a vicious, malicious, deliberate, cowardly, pusillanimous, cold-blooded, lop-eared, blue-nosed, premeditated, and self-made liar” (284). This style is evi-dent in an oft-referenced speech he gave during his 1934 Senatorial campaign:

Friends, fellow citizens, brothers and sisters — hallelujah. My Opponent — yea, this oppo-nent of mine who has the dastardly, dew lapped, brazen, sneering, insulting and sinful effrontery to ask you for your votes without telling you the people of Mississippi what he is a-going to do with them if he gets them — this opponent of mine says he don’t need a platform [...] I shall be the servant and Senator of all the people [...] The appeal and peti-tion of the humblest citizen, yea, whether he comes from the black prairie lands of the east or the alluvial lands of the fertile delta [...] yea, he will be heard by my heart and my feet shall be swift [...] your champion who will not lay his head upon his pillow at night before he has asked his Maker for more strength to do more for you on the morrow [...] Brethren and sisters, I pledge [...]. (in Davenport 1935)

The gubernatorial campaign of 1927 was Bilbo’s most extravagant. Showing his redneck supporters that he was their voice, he united a politically divided state and overcame the urban areas where he was less popular (Key 1949). To bring Bilbo to the masses, his campaign orga-nized a “Bilbo Homecoming,” a multiday rally set in Bilbo’s hometown of Poplarville, a small, rural, agricultural community that verified the connection between Bilbo and his base. The Homecoming was a political performance designed to transcend all previous rallies. Planning for this event began over a year prior to the campaign with every aspect meticulously organized (Bilbo 1926a). It began with a cavalcade of cars over a 10-mile route from Biloxi to Poplarville

Perform

ance of Populism

157

culminating in a parade through the town of vehicles, marchers, and spectators (Bilbo 1926b). Drivers were instructed on when and where to meet and at what speed to travel; the banners on the cars were carefully planned (Bilbo 1926c). Advertisements appeared in papers across the state announcing the event and asking for at least 100 cars from each county with instructions on how to arrive. The parade included three brass bands from around the state, with Mayor John J. Kennedy of Biloxi intro-ducing Bilbo (Bilbo 1926a). More than 18,000 voters from across the state were fed at the rally’s enormous barbecue (Rawls 1926). The campaign committee insisted that every county send representatives, that speakers were selected from across Mississippi, and media representatives from every county were invited (Bilbo 1926a). A baseball game and dance concluded the affair, firmly rooting the day in celebrating Americana (Free Press 1926).

The Free Press of Poplarville wrote of the rally that

Cars bearing banners signifying they came from Tunica, Tishomingo, Wilkinson, Harrison, Sunflower, Warren, Hinds, Hancock, Lamar, Pearl River and many other coun-ties were lined up in the parade, which extended a distance of about three miles, and in which it was estimated twenty-seven counties were represented. The parade was so long that it took hours to get from the town to the pecan orchard where the festivities were held. (Free Press 1926)

Poplarville demonstrated Bilbo’s mass appeal. The 2,000 cars and 18,000 people from out of town overwhelmed the town’s population of 500. After watching the procession of 630 highly decorated cars, the crowd lining the road from town to a large pecan grove behind Bilbo’s home moved to the grove for the rally (Sea Coast Echo 1926). “Platformed on a truck and led by the white-clad band from the State Teachers’ College at Hattiesburg, former Governor Bilbo headed the parade that threaded the narrow main street of the town in a procession three and a half miles long, that took an hour and forty minutes to roll past the thousands standing on the curbstones” (Sea Coast Echo 1926).

The 600 pounds of barbecue quickly ran out. The crowd listened to speeches carefully selected to represent regions of the state, reinforcing Bilbo’s belief that he alone saw all of Mississippi. Of course, “all” meant whites only. The final speaker was Bilbo himself opening his campaign. He first focused on the special guests who’d come to the event, then he thanked those who had spoken on his behalf, and, finally, he presented his platform. He included his usual biblical allusions, portraying his supporters as blessed, in opposition to the damned. He argued for relying on state prisoners, mostly black, for free labor in these terms: “God Almighty has furnished the day, the devil will furnish the convicts, and why not save the people’s tax money and build roads that will stay?” (Sea Coast Echo 1926). He gave the bulk of his attention to the problems of his constituents: public health and education, taxation, financial support for widows and orphans, and veterans’ issues.

Figure 6. Theodore Bilbo speaks to a crowd of supporters from his customized campaign truck in Mississippi. (Photo courtesy of McCain Library and Archives, the University of Southern Mississippi)

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

158

While the individual elements of the Bilbo Homecoming — a parade with cars and bands, invited speakers, media presence — are predictable, the sheer size and reach of the event marks it as unique in Mississippi political history. The event was disseminated to the entire state, by means of radio, newspapers, and, most significantly, film. A film of the rally was shown in the-atres throughout the state.9 In these ways, Bilbo’s supporters were able to experience the rally regardless of whether they attended in person (Bilbo 1926a). The Homecoming in all its guises demonstrated how Bilbo, a true small town good ol’ boy, embodied Mississippi’s rural whites.

But it was Bilbo’s performance style that drew crowds to his rallies. A small man (5'2" tall, though he claimed to be 5'7"), his “booming” voice was notable, and allowed him to project himself as a much larger presence (Giroux 1984:23). Favorite techniques were throwing out his arm and pointing his finger at rivals or accentuating his castigations by angrily jabbing his fin-ger into the air if his opponents were not present.

As the most basic measures of civil rights legislation, such as the doomed 1934 Castigan-Wagner antilynching bill, began appearing in Washington, Bilbo’s defining qualification as a populist politician, that he was the epitome of the rural white population of Mississippi, became increasingly focused on his bigotry and racism. His campaign speech for his final senatorial election notably lacks the allusions to classical texts or even the biblical narratives that were the hallmarks of his earlier campaigns. Instead it is full of warnings that “wherever the black man and white man has tried to live side by side in any country, the end is mongrelization and destruction of both races” (Bilbo 1946).

Eugene Talmadge(1884 –1946)

“The Wild Man from Sugar Creek,” as Talmadge came to be known, was born in Forsyth, Georgia, a small town of just over 1,100 people, northeast of Atlanta. “Sugar Creek” referred to the plantation-style home he built as a retreat. Talmadge was born into a well-off family of planters, eventually graduating with a law degree from the University of Georgia (Anderson 1975:12). His career was split between the small law practice he ran, mainly aiding poor whites, and farming the land his wife had inherited after the death of her first husband. He entered public office at the age of 42 as state agricultural commissioner (Anderson 1975:75–76). Disliked by many politicians, Talmadge was seen as stubborn, bombastic, crude, and rude. He had a string of losses in pursuit of statewide office before and after his term as agricultural commissioner. Yet, his successes were plentiful as well. The factors that elevated Talmadge to the governorship four times, beginning in 1932, were tied to his willingness to make a show of himself. To this day, Talmadge is remembered, and reviled, for his oppression of black people (Baker 2016).

Talmadge’s success depended on rural, white, farming communities. His popularity in these districts sprung largely from his ability to craft a performance style that reflected and reso-nated with those populations. The Georgia Democratic primary was not based on total vote counts but, rather, was based on a county unit system where each county carried a tiered num-ber of delegates (something like the national electoral college system). Because of this structure, Talmadge only needed to win a majority of county unit votes, not the majority of votes overall. He won by focusing on the sparsely populated rural counties where he was most popular, ignor-ing unfavorable cities and districts like Atlanta (Cobb 1975:197–98).

Talmadge worked hard to depict himself as a simple farmer, just like his supporters (Anderson 1975:43; Logue 1987:391; Galloway 1995:675). He had a thick country accent and

9. Unfortunately, despite our search of a number of Mississippi Archives, it does not appear that footage from the film has survived.

Perform

ance of Populism

159

was often credited with “speak-ing like a farmer” or having “a farmer’s sense of humor” (Cobb 1975:45). He often referred to the fact that he lived “on a farm five miles from McRae” and would point out that he was “the only ‘dirt’ farmer” in the race (Logue 1989:33). He mocked out-of-state people who wasted money “in California on ele-phant pools, and aesthetic dance classes, and boondoggling” (Pathe News 1936). Much of his “farmer’s sensibility” was simply a willingness to use profane lan-guage and engage in unabashed racism. He found ways to weave bigotry — anti-Semitic as well as antiblack — into nearly any question or issue. For instance, when Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield asked him about infla-tion, Talmadge responded:

About the only fair way to inflate currency — to keep the Shylocks and the moneychang-ers from taking all of the gravy off of it — would be to put up a whole lot of money and put it in airplanes in every county and scatter it. And then if you did that, the big-gest strongest ruffian would get the most, so what we need is the ratio of certain things changed. For justice, we need the raw products to bring a better price. And if they bring a price that’s comfortable to the farmer it’ll correct all the other evils. (Atlanta History Center 2009)

Talmadge was “the Wild Man” because of his impassioned speaking style, punctuated by wild gesticulating. At a 1942 rally in Griffin, Talmadge’s arms are seldom lowered. He keeps them at shoulder level, pointing out at his audience, often raising both fists high above his head, as he leans into the microphones, calling out to the audience and constantly pulling at his shirt sleeves in a gesture of “rolling up his sleeves” — an embodiment of his willingness and readiness to work for his base. In the heat, with his hands always moving, Talmadge sweats, his hair is wet, and he dabs his underarms with a handkerchief. This dispels any notion he is “sophisticated,” underscoring a man willing to be in the heat under the Georgia sun, a man who doesn’t hide his farmer’s habits. The crowd cheers nearly every sentence that Talmadge throws at them, and he smiles repeatedly as he creates a mutual understanding. From his earliest political appearances, like Long and Bilbo, Talmadge gave numerous speeches throughout the state, often deliver-ing three or more in the same day. He routinely appeared in 10 counties in 5 days (Atlanta Constitution 1928). His small-town events attracted hundreds of spectators, and the larger cam-paign rallies often numbered between 5 and 10 thousand.

Talmadge relied on the two essential rhetorical features of Southern populism: bitter attacks on elites and the creation of an “us vs. them” division. He would lash out at rivals, calling them “brother jackass,” and loved to accuse them of corruption, once calling out an opponent and listing every relative he put on the government payroll (Logue 1989:91). He claimed to speak for the “little guy,” telling his crowds, “I am going over the heads of the petty politicians and making my appeal to the people themselves” (32). But his rhetoric only partially explains his

Figure 7. Eugene Talmadge in one of his typical gestures, raises his fists as he speaks to a crowd of supporters in Lyons, Georgia, during his 1946 gubernatorial campaign against Ellis Arnell. (Photo courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Special Collections and Archives, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection)

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

160

popularity. When Georgians attended a Talmadge rally, they wanted the “Wild Man” — and this is what they got. The New York Times wrote that “Eugene Talmadge undoubtedly has that something which makes movie stars and is the despair of the word painter — in Gene’s case it CAN’T be sex appeal so it must be personality!” (Galloway 1995:675). A rally would start with music, usually a brass band playing light, popular music and marches to create a patriotic air. Then came performers like Fiddlin’ John Carson, singing about one of Talmadge’s early signa-ture issues, the $3.00 automobile license fee replacing the $30.00 one:

I’ve gotta Eugene dog, I gotta Eugene cat, I’m a Talmadge man from ma shoes to ma hat. Farmer in the cawnfield hollerin’ whoa gee haw, Kain’t put no thirty-dollar tag on a three-dollar car. (Anderson 1975:75)

Talmadge’s rallies were nearly always outdoors so more people could attend. They were large, patriotic barbeque festivals that were compared to circuses (Logue 1989:102). Depending on local agriculture, there was pork, duck, chicken, or beef, vast quantities of bread, potato chips, and pickles, along with hundreds of gallons of lemonade; plus corn liquor, brought by attendees (Logue 1981:206–07; Anderson 1975:68–71). Talmadge asked local officials and prominent members of the community to speak prior to his address, offering support for “their Gene” (Logue 1987:207; Anderson 1975:45).

Much of Talmadge’s success was due to his storyteller’s approach. In a speech during his 1932 gubernatorial campaign, Talmadge assailed the lazy rich and praised the suffering farmer:

Rich men don’t work hard enough to wear out many clothes and shoes, and they don’t eat any more than we do. Not as much, because most of them have got dyspepsia any-way. The basis of the buying power of this country is in the wallet of the man behind the plow: the man who lays brick, drives spikes or operates a lathe. When a man gets money in his pockets the first thing he spends it for is food, and then he pays the rent and last year’s doctor bill. Then he buys Mary a dress and himself some overalls. If there is any left he is sure to buy an automobile or some new tires, and maybe some fresh curtains for the living room and a chair or two. Then he looks around and about the time that that hole in the roof gets big enough to throw a chicken through, he will buy a roll of rub-beroid roofing and patch it. It won’t be long then before the factory wheels will begin to turn again; the thousands of men who now ride freight trains free will buy tickets or drive their own cars, and the merchants will have to give up their checker games; lawyers will blow the dust from their books and the stream of commerce will once more flow in unobstructed channels. (Atlanta Constitution 1932)

Talmadge rarely sounded like an evangelical preacher, his oratorical style being more the foul-mouthed storyteller and crowd rouser. Most of Talmadge’s stories and cusses were con-sidered too offensive to print and were written up by reporters as “smutty yarns” and “vulgar stories” (Logue 1989:60). However, from those examples that do exist it is clear he generally relied on crass humor and racist jokes. For instance, during a victory speech he waved away various accusations his opponent had leveled at him, except to say he had had to hold his wife back from the press when she wanted to defend him against a reference to his having “a three-penny nail” in his trousers (Atlanta History Center 2009). While running for Senate in 1936 he accosted his rivals as “name callers,” and then made the following comparison: “Did you ever think about a n[...]r’s way of getting into court? Just let two n[...]rs have a fight and the one that can get to the courthouse first he thinks he is clear if he goes there and prosecutes the other, regardless of how it is, if he beats the other man there” (Logue 1989:264). To whip his audiences into a frenzy, Talmadge deliberately picked significant phrases to elongate or punch out and grew increasingly loud and high towards the summation of his arguments (3–13). He also used audience plants who would spur him on. For instance, a veteran might raise a ques-

Perform

ance of Populism

161

Figure 8. Buses of (white, male) students from the University of Georgia travel to Gainesville, Georgia to support Talmadge’s 1942 Campaign. (Photo courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Special Collections and Archives, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection)

10. Talmadge’s lifelong associate Chip Robert allegedly warned Franklin Roosevelt against letting Talmadge seek fed-eral office, saying, “You can’t let Gene Talmadge put on the show he’d put on. He’d be a menace.” (Anderson 1975:175)

tion regarding military issues. Or plants were told to refer to one of Talmadge’s oppo-nents so that the “Wild Man” could rail against the enemy (206). Talmadge was known for his trademark suspenders, and his most ardent fans copied the look, the suspenders being the MAGA hat of the day (Galloway 1995:677).

In his later years, Talmadge struggled. By the late 1930s, he had been battered by years of scandal, the most serious being the theft of $20,000 from the state that he claimed to have used to raise the price of hogs; but he could not provide receipts. Also, he had a public break with the Democratic Party when he opposed Roosevelt’s New Deal, a decision that led to a humiliating defeat in the 1936 Senate campaign against Richard Russell.10 When his campaigns grew more difficult, Talmadge lost control of his crowds. Rallies were no longer carnivalesque, as an exasperated Talmadge repeatedly failed to persuade his audiences. Fistfights broke out with national guardsmen separating the candi-date from the crowds. At several events, there were arrests, further tarnishing Talmadge’s image (Mead 1981:37).

In his final campaigns Talmadge was explicitly racist. He always had been a notorious bigot: one of Talmadge’s chief complaints against the New Deal was that it would also benefit black people. Russell told the crowd that Talmadge’s “n[...]r, n[...]r, n[...]r” rhetoric wouldn’t trick whites (Logue 1989:145). In the 1940s Talmadge’s chief opponent for Governor was Ellis Arnell, an economic and racial progressive who is best remembered for abolishing the poll tax and lowering the voting age to 18. Facing Arnell brought out Talmadge’s most extreme stances regarding race. His platform increasingly was fueled by white supremacist posturing. At his opening campaign rally Talmadge declared that “before God, friends, the n[...]rs will never go to a school where I am governor” (Logue 1989:220). As the campaign went on, he took to open intimidation telling blacks to not vote and encouraging his supporters to physically prevent blacks from voting. At a rally in Swainsboro, Talmadge said:

Stay in your place. [Do] not be misled by carpetbaggers and scalawags who do not under-stand you. Wise Negroes will stay away from the white folks’ ballot boxes July 17. We are the true friends of the Negroes, always have been, and always will be as long as they stay in the definite place we have provided for them. But the white folks will just take so much

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

162

11. The three men referenced were frequent Talmadge foes. Julius Rosenwald was a wealthy businessman and philan-thropist whose Rosenwald Fund provided money for the education of black children in the rural South. Talmadge had a notable fight with the Georgia board of regents over the use of Rosenwald Fund money. Jim Cox ran the Atlanta Constitution, which regularly attacked Talmadge. Henry Wallace earned Talmadge’s ire firstly for his firmly progressive stance as secretary of agriculture during the New Deal, and later as vice president for his fierce criti-cism of European and US colonial practices.

12. Think here of Long’s promise of “a chicken in every pot” or Talmadge’s pledge to reduce the cost of an automo-bile license to three dollars, effectively making owning a car affordable for farmers.

from Rosenwald, Ohio Jim Cox, Henry Wallace,11 and others operating under the influ-ence of Russia. (Atlanta Constitution 1946)

While black people attending Talmadge rallies were exceedingly rare, because his rallies were amplified and also on local radio stations, it is likely the message reached the black citizens of Swainsboro. The final comment about Russia also demonstrates how Talmadge continued to use his tactic of making wild accusations against his rivals. Talmadge’s message reached the white audience, reminding them of the “dangers” of black voting. In earlier rallies, Talmadge said, “failure to prohibit Negro voting in the primaries would result in social equality,” arguing that if black people could vote, “negro candidates for public office will be thick as flies around a jug of molasses” (Logue 1989:226). Talmadge’s stoking the racist fears of his base worked. He won the governorship again in 1946, but died before he could take office.

Performative Populism

Long, Bilbo, and Talmadge demonstrate a clear, and often successful, political strategy based upon performative populism. They utilize a three-pronged approach of holding highly theatri-calized rallies that were popular entertainments for rural white populations. First, through these rallies they provided, both rhetorically and sensorially, a sense of the carnivalesque where their audiences radically reimagined power structures — visualizing themselves as “kings” or over-throwing “elites.”12 Second, they used these rallies to help foster a sense of group identity tied to race and class, through a use of “us vs. them” rhetoric, presenting marginalization narratives, and promising their supporters various forms of “winning.” Finally, they worked hard to be seen as representative of the “best of” the rural, white populations they won over through a mix of humor, references to local concerns, and the use of various signifiers (such as accents and coarse language) to sound like their constituents. This helped distinguish them from politicians such as FDR, whom they mocked for his patrician accent, despite occasional overlapping economic pol-icies that aided working-class Southerners. Each could recite biblical passages, and often turned to favorite poems or quotations to impress their audiences. This ability to navigate plain-speak and highbrow elocution reflects the importance of being both a common man and a cut above all the rest. They bitterly attacked their political rivals to mark how they were separate from them. While emotionally connected to the populations they represented, they did not necessar-ily put forth policies that corresponded to the interests of their constituents.

While this phenomenon was particularly clear in the Depression-era South, performative populism is alive and well in the campaigns of Donald J. Trump. Also to some degree in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders. Although on opposite sides of the political spectrum, both Trump and Sanders forged campaigns that used political rallies to build and maintain fervently loyal bases (Bender 2019; Gonyea 2020). Trump rallies in particular were (and remain) entertain-ment. His long history as a TV and media personality prepared him to entertain a built-in audi-ence excited to see him in person. Trump’s skillset is well honed to engage his audience and form a loyal base.

Also notable is that Talmadge and Trump did not, do not, enjoy majority support. Regarding Long, following his election as governor, he got voting reforms passed that made it nearly

Perform

ance of Populism

163

impossible for another candidate to be elected. Talmadge gamed a highly disproportionate pri-mary system to ensure victory, as did Trump, who lost the 2016 national popular vote by nearly 3,000,000. Long, Bilbo, and Talmadge sought exclusively white voters, as Trump primarily does, recognizing that the disenfranchisement of blacks would allow them to win. All the American populists view rallies as critical to their base support and election chances. Likewise, we see sim-ilar trends with populist figures such as Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Narendra Modi of India.

Undoubtedly, performative populism will continue to be a powerful force of the political landscape in years to come. While this form of politics may yield mixed results, it will continue to build on certain fundamental principles, not least among them an understanding of how to theatricalize politics to entertain and develop loyal publics.

References

Anderson, William. 1975. The Wild Man from Sugar Creek: The Political Career of Eugene Talmadge. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Atlanta Constitution. 1928. “Eugene Talmadge Speaks This Week in Ten Counties.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers, 2 September (500237209).

Atlanta Constitution. 1932. “New U.S. Loan Bank Scored by Talmadge.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers, 21 July (501453978).

Atlanta Constitution. 1946. “Stay Away from White Folks’ Ballot Boxes–Gene to Negroes.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers, 11 July (24731609).

Atlanta History Center. 2009. “Hartsfield Film Collection - Eugene Talmadge.” YouTube, 10 December. Accessed 17 May 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPXg9Rk4cfI&t=2s.

Baker, Peter C. 2016. “A Lynching in Georgia: The Living Memorial to America’s History of Racist Violence.” The Guardian, 2 November. Accessed 10 October 2018. www.theguardian.com/world/2016 /nov/02/a-lynching-in-georgia-the-living-memorial-to-americas-history-of-racist-violence.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. (1968) 1984. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bender, Michael C. 2019. “Trump’s Rallies Aren’t a Sideshow. They Are the Campaign.” The Wall Street Journal, 22 October. Accessed 7 May 2020. www.wsj.com/articles/trumps-rallies-arent-just-part-of -his-campaign-they-are-the-campaign-11571753199.

Beyerlein, Kraig, and Kenneth T. Andrews. 2008. “Black Voting During the Civil Rights Movement: A Micro-level Analysis.” Social Forces 87, 1:65–93. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0095.

Bilbo, Theodore. 1911. Campaign Materials, 18 May. Box 1, Folder 4, Theodore G. Bilbo Papers. McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries.

Bilbo, Theodore. 1926a. Letter to Ed Ott, et. al, 30 June. Box 1, Folder 15, Theodore G. Bilbo Papers. McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries.

Bilbo, Theodore. 1926b. Campaign letter from Theodore Bilbo, 30 June. Box 1, Folder 15, Theodore G. Bilbo Papers. McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries.

Bilbo, Theodore. 1926c. Letter to John Street, 26 June. Box 20, Folder 18, Theodore G. Bilbo Papers. McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries.

Bilbo, Theodore. 1946. Senator Theodore Bilbo Campaign Speech, 7 May, online transcript. Mississippi Department of Archives. Accessed 16 May 2020. www.mdah.ms.gov/arrec/digital_archives/vault/projects /OHtranscripts/AU1008_120959.pdf.

Blain, Keisha N. 2018. Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Brattain, Michelle. 2001. The Politics of Whiteness: Race, Workers, and Culture in the Modern South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brinkley, Alan. 1982. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Twar

dow

ski/

Fine

164

Burns, Ken. 1985. Huey Long. Documentary. New York: Corporation for Public Broadcasting. DVD and streaming video, 88 min.

Cobb, James C. 1975. “Not Gone, But Forgotten: Eugene Talmadge and the 1938 Purge Campaign.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 59, 2:197–209.

Crawford, J.B. 1911. Letter to J.B. Gardner, 6 April. Box 1, Folder 4, Theodore G. Bilbo Papers. McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries.

Davenport, Walter. 1935. “Brethren and Sisters.” Colliers, 16 March:19, 53–55.

Dolan, Jill. 2005. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fenno, Richard F. 1978. Home Style: House Members in Their Districts. New York: HarperCollins.

Fitzgerald, Michael W. 1997. “‘We Have Found a Moses’: Theodore Bilbo, Black Nationalism, and the Greater Liberia Bill of 1939.” Journal of Southern History 63, 2:293–320.

Flowers, Paul. 1956. Interview with T. Harry Williams, 29 October, Memphis. Range 34, Box 19, Folder 63. Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Free Press. 1926. “Homecoming Day Big Success.” 22 July:1.

Galloway, Tammy Harden. 1995. “‘Tribune of the Masses and a Champion of the People’: Eugene Talmadge and the Three-Dollar Tag.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 79, 3:673–84.

Gary, Leon. 1960. Interview with T. Harry Williams, 10 December, Baton Rouge. Range 34, Box 19, Folder 74. Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Giroux, Vincent Arthur, Jr. 1984. “Theodore G. Bilbo: Progressive to Public Racist.” PhD diss., Indiana University, Bloomington.

Gleason, Ira. 1956. Interview with T. Harry Williams, 26 December. Range 34, Box 19, Folder 77. Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Gonyea, Don. 2020. “Bernie Sanders’ Hallmark Rally Strategy.” NPR, 25 January. Accessed 20 May 2020. www.npr.org/2020/01/25/799470782/bernie-sanderss-hallmark-rally-strategy.

Green, A. Wigfall. 1963. The Man Bilbo. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Haas, Edward F. 1994. “Huey Pierce Long and Historical Speculation.” History Teacher 27, 2:125–31.

Hair, William Ivy. 1991. The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Harold, Claudrena N. 2016. New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Hendrix, Jerry A. 1981. “Theodore G. Bilbo: Evangelist of Racial Purity.” In The Oratory of Southern Demagogues, ed. Cal M. Logue and Howard Dorgan, 151–74. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Hogan, J. Michael, and Glen Williams. 2004. “The Rusticity and Religiosity of Huey P. Long.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 7, 2:149–71.

Hughes, Langston. 1947. “Here to Yonder: The Death of Bilbo.” Chicago Defender, 30 August:14.

Jeansonne, Glen. 1992. “Huey Long and Racism.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 33, 3 (Summer):265–82.

Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy. 2017. “Populism: An Overview of the Concept and the State of the Art.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, ed. Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, 2–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Key, V.O., with Alexander Heard. 1949. Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Kim, Suk-Young. 2010. Illusive Utopia: Theater, Film, and Everyday Performance in North Korea. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

Perform

ance of Populism

165

Lee, Michael J. 2006. “The Populist Chameleon: The People’s Party, Huey Long, George Wallace, and the Populist Argumentative Frame.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 92, 4:355–78.

Lemmon, Sarah McCulloh. 1954. “The Ideology of Eugene Talmadge.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 38, 3 (September):226– 48.

Logue, Cal M. 1981. “The Coercive Campaign Prophecy of Gene Talmadge, 1926–1946.” In The Oratory of Southern Demagogues, ed. Cal M. Logue and Howard Dorgan, 205–30. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.