Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

-

Upload

paulo-felix -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

1/40

1314 DECEMBER 2011 | WASHINGTON, DC

IFPRI A member of the CGIAR Consortium

Derek Headey and Adam Kennedy

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

2/40

INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE2033 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006-1002 USATel.: +1 202-862-5600 Skype: ifprihomeofficeFax: +1 202-467-4439 Email: [email protected]

www.ifpri.org

Copyright 2012 Interna onal Food Policy Research Ins tute. For permission to republish, contact [email protected] .

The views expressed herein do not necessarily re ect the policies or opinions of the cosponsoring or suppor ngorganiza ons of the conference.

ISBN 978- 0-89629-797-5

DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.2499/9780896297977

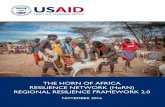

ABOUT USAIDSince 1961, USAID has been the principal U.S. agency to extend assistance to countriesrecovering from disaster, trying to escape poverty, and engaging in democra c reforms.U.S. foreign assistance has always had the twofold purpose of furthering Americasinterests while improving lives in the developing world. The Agency carries out U.S.foreign policy by promo ng human progress at the same me it expands stable, free so -cie es, creates markets and trade partners for the United States, and fosters good willabroad. Spending less than one-half of 1 percent of the federal budget, USAID works in

over 100 countries to: promote economic prosperity; strengthen democracy and goodgovernance; improve global health, food security, environmental sustainability andeduca on; help socie es prevent and recover from con icts; and provide humanitarianassistance in the wake of natural and man-made disasters.

ABOUT IFPRIThe Interna onal Food Policy Research Ins tute (IFPRI) was established in 1975 toiden fy and analyze alterna ve na onal and interna onal strategies and policies formee ng food needs of the developing world on a sustainable basis, with par cularemphasis on low-income countries and on the poorer groups in those countries. Whilethe research e ort is geared to the precise objec ve of contribu ng to the reduc on

of hunger and malnutri on, the factors involved are many and wide-ranging, requiringanalysis of underlying processes and extending beyond a narrowly de ned food sector.The Ins tutes research program re ects worldwide collabora on with governmentsand private and public ins tu ons interested in increasing food produc on andimproving the equity of its distribu on. Research results are disseminated topolicymakers, opinion formers, administrators, policy analysts, researchers, and othersconcerned with na onal and interna onal food and agricultural policy.

IFPRI is a member of the CGIAR Consor um.

mailto:[email protected]://www.ifpri.org/mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]://www.ifpri.org/mailto:[email protected] -

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

3/40

Derek Headey and Adam Kennedy

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

4/40

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

5/40

VII113

4

5

81011

1717

25

29

CONTENTSLETTER FROM USAID ADMINISTRATOR RAJIV SHAHINTRODUCTIONLIVELIHOODS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA: CONTEXTRESILIENCE 101: DEFINING AND FRAMING RESILIENCE

Building Resilience through the Productive Sa ety Net ProgrammeTHE IMPLICATIONS OF RESILIENCE

EXPLORING THE EVIDENCE BASE IN FIVE DOMAINSEconomic Growth and Trans ormationNatural Resource ManagementHealth and NutritionSocial DimensionGovernance, Institutions, and Building Peace

MOVING THE AGENDA FORWARDREFERENCESPLENARY SESSION NOTES

Resilience 101Arid and Marginal Lands Recovery Consortium (ARC) Program in KenyaDisaster Risk Reduction/Hyogo Framework Pastoralist Livelihood Initiative in EthiopiaKeynote AddressThe Nairobi Strategy: Enhanced Partnership to Eradicate Drought EmergenciesConsensus Building and the Productive Sa ety Net ProgrammeThe Links between Resilience, Confict, and Food SecuritySome Lessons rom Ethiopias PSNPThe Value Chain ModelDFIDs New Resilience AgendaEarly Lessons rom the Graduation ModelMoving Forward in the Horn

BREAKOUT SESSION NOTESDAY 1: BREAKOUT SESSIONS BY SECTOR

Natural ResourcesSocial FactorsHealth and NutritionGovernance and InstitutionsEconomics

DAY 2: MIXED GROUP BREAKOUT SESSIONSStrategies and Policies to Build Resilience

WORKSHOP AGENDA

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

6/40

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

7/40

Dear Partners,

In 2011, the Horn of Africa faced the worst drought in 60 years, leading to emergency food insecurity levels in Kenya and Ethiopia andfamine in Somalia. At the height of the drought, more than 13 million people across the region required humanitarian assistance, and morethan 700,000 refugees ed Somalia.

At the same me, many communi es showed resilience in the face of these harsh condi ons, demonstra ng e ec ve coping strategies thatreduced the economic impact of the drought and enabled them to maintain a su cient degree of food security, health, and well-being.

It is in this context that the United States Agency for Interna onal Development (USAID) hosted a workshop tled, Enhancing Resilience inthe Horn of Africa: An Evidence Based Workshop on Strategies for Success. The workshop, held December 1314, 2011, at the MadisonHotel in Washington, DC, was co-hosted by USAIDs Bureau for Democracy, Con ict and Humanitarian Assistance, Bureau for Food Security,Bureau for Africa, and Bureau for Policy, Planning, and Learning. It was facilitated by USAIDs O ce of Food for Peace-funded TOPS program,as well as the Interna onal Food Policy Research Ins tute.

Providing a pla orm for learning, the workshop iden ed successful strategies, enabling condi ons, and policies for strengthening resil -ience, as well as approaches that have been less successful. The workshop was principally designed to ini ate a dialogue among donors,private voluntary organiza ons, researchers and academics, and the private sector on evidence-based strategies for enhancing resilience inthe Horn of Africa. The dialogue centered on several key issues:

What is meant by resilience and resilience programming? What are successful strategies and enabling condi ons that can help build resilience, and what lessons can be learned from previous

e orts? What value does resilience programming have in mi ga ng the e ects of shocks, speeding recovery from them, and building path -

ways out of poverty? What are the linkages between resilience and economic growth?

More than 180 par cipants with diverse backgrounds and disciplines, including agriculture, livestock, nutri on, con ict, gender, governance,economics, and health, par cipated in the workshop. The format consisted of formal presenta ons and more informal roundtable and ple -

nary discussions to maximize par cipa on and draw from the groups broad base of knowledge. All material from the workshop, includingvideos and Power Points of the plenaries, are available at the workshop: h p://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/enhancing-resilience-horn-africa-evidence-based-workshop-strategies-success-agenda.

This workshop is part of our Agencys larger e ort to help countries and communi es withstand increasingly frequent and severe environ -mental shocks. USAID recently launched a planning process to more e ec vely link our humanitarian assistance and development programsto enhance resilience in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere. In addi on, we are suppor ng a newly established consor um of research ins tu

ons, interna onal organiza ons, and nongovernmental partners to provide analy cal support for country and regional level programming,including the development of the common program framework for ending drought emergencies in the Horn of Africa.

In support of the resilience agenda for the Horn of Africa, USAID, together with the African Union, the Intergovernmental Authority onDevelopment, and a number of other development partners, co-hosted a Joint Ministerial and High-Level Development Partners Mee ngon Drought Resilience in the Horn of Africa. The mee ng took place on April 4, 2012, in Nairobi, Kenya, and demonstrated commitment tocountry-led, regional level programming on ending drought emergencies in the Horn of Africa. It resulted in the forma on of a new partner -shipthe Global Alliance for Ac on for Drought Resilience and Growthto strengthen coordina on within the development community,spur economic growth, build new partnerships with the private sector, and reduce food insecurity. The role of the alliance will be nalizedwith development partners over the coming months.

Across USAID, we are examining our policies and opera ons to see how we can more e ec vely build resilience, a key Agency priority. It isour hope that these workshop proceedings, which combine research ndings with discussion points from the December workshop sessions,will contribute to the growing body of evidence on strategies for enhancing resilience in the Horn of Africa and help to focus collec ve ef -forts on the resilience agenda. We look forward to con nuing to work with our partners and nding new ways to collaborate.

Sincerely,

Rajiv Shah

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

8/40

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

9/401

The arid and semi-arid lowlands(ASALs) of Djibou , Ethiopia, Kenya,and Somalia are geographically, lin -guis cally, and economically very dis nctfrom the highland areas of these coun -tries. While the highland economies arelargely dominated by se led crop produc -

on and nonfarm industries, the lowlandsare heavily dominated by urban dwell -ers (1020 percent of the total ASALspopula on), pastoralism (mobile livestockrearing), and secondary livelihoods, suchas collec on of natural products for con -sump on and sale (including rewood,charcoal, and gum-resin) and dryland cropproduc on (both irrigated and rainfed).The dominance of pastoralism is a directresult of interseasonal and interannual

varia on in rainfall and abundant landresources, which require and histori -cally have allowed households to movelivestock herds in response to di erencesin grazing and water resources that ex -ist over space and me. Although exactnumbers are unavailable, it is es matedthat approximately 40 million people livein these areas, with perhaps half of themloosely amenable to being described aspastoralists (Headey, Seyoum Ta esse,and You 2012).

Although the Horn of Africa is full of di erent types of people and dis ncteconomies, the climate and its relatedrisks, par cularly acute vulnerability todrought, are shared across the region.Moreover, while the peoples of the re -

gion have longstanding tradi onal copingmechanismsincluding the mobility of pastoralism and tradi onal family andclan support systemsthere is consider -able evidence that these techniques arebreaking down. Mobility, in par cular, isnow thought to be much more restrictedthan in earlier mes due to the com -plex combina on of popula on growth;fragmenta on of grazing lands causedby cropland expansion, pest invasion,and land grabs; and local, regional, andinterna onal con ict (Flintan 2011). Suchstresses and shocks ini ate a viciouscycle of insecurity: tradi onal social pro -tec on systems erode, making it harderfor households to recover from shocks,which now occur more frequently and

The Horn of Africa is acutely vulnerable to food security crises that arise from complex causes, including swi shocks from thevagaries of climatepar cularly exposure to drought and oodingand slower-moving stresses like the complex nexus of rapid popula on growth, land fragmenta on, natural resource degrada on, and con ict. The 20102011 crisis in the region

emphasized the shortcomings, as well as some of the strengths, of interna onal and na onal relief e ortsnamely that while theyhave saved lives, and increasingly livelihoods, they have not su ciently increased the capacity of the region to withstand futureshocks and stresses. In short, they have not done enough to enhance resilience to the point where the region can avert crises similarto the one it endured in 20102011.

For a region like the Horn of Africa, resilience has profound implica ons for development programming. As US Agency forInterna onal Development (USAID) Administrator Rajiv Shah said, For too long we have segregated humanitarian support and ac

vi es and development ac vi es. We havent seen the beauty of the possibili es that exist when we think of these things as amore integrated whole. 1 In that sense, resiliencein both concept and ac oncan bridge the two tradi onally dis nct domainsof humanitarian assistance and development support programs.

But how exactly should we de ne resilience, and what does this concept imply for programming, capacity strengthening,ins tu on building, and development strategies as a whole? Is resilience already an important (if implicit) dimension of these ef -forts, or do we need to rethink and redesign the way our e orts are conceived and implemented? Based on previous and ongoingsubstan ve e orts to build resilience, what types of interven ons work or dont workand where is the evidence to show for it?

These ques ons and issues that arise in the programming of our work together with our development partners in the Horn of Africa are the subject ma er of much of the dialogue that took place at the Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa work -shop hosted by USAID in December 2011. The purpose of this set of proceedings is thus to present the key messages from theworkshop and communicate evidence-based strategies that were highlighted to inform future programming of humanitarian anddevelopment assistance e orts. The goal is to bridge the two in a way that maximizes the impact of development partners e orts

and enhances resilience to li millions out of poverty, food, and social insecurity in the Horn of Africa.

1. For a summary o Administrator Rajiv Shahs presentation, see page 13. See the ull presentation here: http://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/usaid-resilience-workshop-keynote-address.

LIVELIHOODS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA: CONTEXT

INTRODUCTION

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

10/40

"

DOLLO ADOREFUGEECOMPLEX

"""

DADAABREFUGEECOMPLEX

DADAABREFUGEECOMPLEX

DOLLO ADOREFUGEECOMPLEX

"

""

"

p

KAKUMAREFUGEE

CAMP

KAKUMAREFUGEE

CAMP

I N D I A N O C EA N

R E D

SE A

G u l f

o f

A d e n

SOMALI

OROMIYA

AFAR

AMHARA

SNNPR

TIGRAY

GAMBELLA

BENESHANGULGUMUZ

DIRE DAWA

HARAR ADDISABABA

MUDUG

SANAAG WOQOOYI

AWDAL GALBEED

BANADIR

BAY

BAKOOL

MIDDLE JUBA

NUGAL

SOOL

LOWER JUBA

LOWER SHABELLE

MIDDLE SHABELLE

GALGADUD

HIRAN

TOGDHEER

BARI

GEDO

WAJIR

MARSABIT TURKANA

KITUI

GARISSA

ISIOLO

TANA RIVER

MANDERA

NAROK

KAJIADO

KILIFI

SAMBURU

TAITA TAVETA

MERU

KWALE

BARINGO

LAIKIPIA

LAMU

MAKUENI

NAKURU

WEST POKOT

HOMA BAY NYERI

SIAYA

MACHAKOS

NANDI

EMBU

NITHI

MIGORI BOMET KISII KIAMBU

BUNGOMA

BUSIA

KISUMU KERICHO

KAKAMEGA

NYANDARUA

UASIN GISHU

MURANGA

E. MARAKWET TRANS-NZOIA

KIRINYAGANYAMIRA

NAIROBI

VIHIGA

MOMBASSA

DolloAdo

Kismaayo

Mombassa

Wajir

Meru

Moyale

Gambela

LokicharLoiyanggalani

El Wak

Ferfer

Megalo Gaalkacyo

Borama

Gonder

Weldiya

Dese

Hargeysa Burco

Laas Caanood

Bossaso

Garoowe

Werder

Gode

Harrar

Todenyang

Marka

Duaale

Xuder

BeletWeyne

Dhuusamarreeb

Garbahaarey

Baidoa

AfgooyeJowhar

E T H I O P I A

SUDAN

K E N YA

S O M A L I A

Y E M E N

S A U D IA R A B I A

T A N Z A N I A

U G A N D A

E R I T R E A

DJIBOUTI

E T H I O P I A

SUDAN

SOUTHSUDANSOUTHSUDAN

K E N YA

S O M A L I A

Y E M E N

S A U D IA R A B I A

T A N Z A N I A

U G A N D A

E R I T R E A

DJIBOUTI

Sanaa

Kigali

Asmara

Kampala

Nairobi

Khartoum

Djibouti

Bujumbura

Mogadishu

Addis Ababa

Dar es Salaam

0 60 120 180 240mi

0 8 0 1 60 24 0km

Source: OCHA (09/08/11)

POPULATION REQUIRINGASSISTANCE

Djibouti 165,642

Ken ya 4, 310, 587

So ma li a 4 ,0 00 ,0 00

Ethiopia 4,828,757

TOTAL 13,304,986

No acute food insecurity

Moderately food insecure

Highly food insecure

Extremely food insecure

FamineSOURCE: FEWS NET, Current Conditions

SEPTEMBER 2011

ESTIMATED FOODSECURITY LEVELS

2

leave households further exposed tosubsequent shocks (Devereux 2006). Itis within this environment that millionsof people have become con nuously de -pendent on humanitarian assistance forfood and nancial aid, and refugee situ -a ons in Kenya and Ethiopia that wereoriginally designed as temporary mi -ga ng strategies have been prolongedfor years. This is certainly unsustainableand new thinking and ac ons on how tomake these communi es resilient and ul -

mately prosperous is urgently needed.

Con ict, poor governance, and therelated breakdown in tradi onal copingmechanisms also characterize the ASALsin the Horn of Africa. These challengeslargely explain the apparently increasedvulnerability of ASAL popula ons todrought and also the regional pa ern of drought impacts. Data from the Emer -gency Events Database (EM-DAT) showthat the number of people adverselya ected by drought has been increas -ing over me (Headey, Seyoum Ta esse,and You 2012) (Figure 2). Other researchshows that con ict and poor governanceare associated with the severity of the201112 humanitarian crisis across theregion, with famine declared mainly inthe most con ict-a ected areas of south -ern Somalia (Maystadt et al. 2011). So,while climate change cannot yet be de -claredor discounted asa contribu ngfactor to the famine and food scarcity inthe Horn of Africa, it is well establishedthat the regions vulnerability to majorshocks is by no means caused solely byclimate-related in uences.

Inadequate governance is just asproblema c to building resilience ascon icta conclusion drawn from majorstudies of the successes and failures of interven ons in this region (for example,McPeak et al. 2011 and Li le et al.

2010). 2 First, large-scale physical andsocial infrastructure have been neglectedin the region; policies and investmentsthat would bene t the livestock sectorthe primary sector in the regionhavealso been lacking. Educa on and health

outcomes in ASAL regions, for example,are far below those of highland regionsin these East African countries anddeplorably so in an absolute sense (forexample, o en less than 20 percent of adults can read). Governments in theregion have also emphasized sedenta -riza on of mobile communi es, without

2. See the discussion notes rom the workshopssession on governance on pages 22-23.

due understanding of the importance of mobility for livestock rearing and tradein the region. Second, where at-scaleinterven ons have taken place, they haveat best a modest track record of e cacy,sustainability, and poverty reduc on.

In the past, e orts to promote ranch-style livestock systems did not yield thebroad-based pro-poor economic impactsneeded to widely enhance resilienceamong the poorer pastoralists (McPeaket al. 2011). More recently, a numberof e orts to promote commercializa onthrough value-chain approaches have be -gun, and while a select few, par cularlylivestock traders, have bene ted from -

Source: DFID 2011.

FIGURE 1. Estimated ood insecurity at the height o the Horn o A ricaamine

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

11/40

E s t i m a t e d n u

m b e r o f p e o p l e

a f f e c t e d b y

d r o u

g h t ( m i l l i o n s )

1 9 7 0

1 9 7 2

1 9 7 4

1 9 7 6

1 9 7 8

1 9 8 0

1 9 8 2

1 9 8 4

1 9 8 6

1 9 8 8

1 9 9 0

1 9 9 2

1 9 9 4

1 9 9 6

1 9 9 8

2 0 0 0

2 0 0 2

2 0 0 4

2 0 0 6

2 0 0 8

2 0 1 0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Ethiopia

Kenya

Somalia

Djibouti

3

such programs, they tend not to be themost vulnerable and poor (Barre 2004,Hashi and Mohammed 2010). Mostprograms thus far have also operated ata rela vely small scale.

Finally, while there have been manye ec ve interven ons in the region,most have lacked scale or simply havenot been sustained. As noted in theworkshop, many development programshave been rela vely short-lived (usuallyup to ve years), which limits the scopeof poten al impact and may actuallyinduce outcomes opposite than the onesintended. Too o en governments anddevelopment partners demand rapid

results and gradua on of bene ciariesfrom assistance programs in a rela velyshort me, but enhancing resilience ap -pears to require sustained interven onand substan al commitments from allstakeholders involved. 3

3. For a summary o Karen Brookss presentation,see page 16. See the ull presentation here:http://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/usaid-resilience-workshop-plenary-presentation-moving- orward-horn.

For the most part, the limited impactof these e ortsand some mes the lackof any e ortshas stemmed from mis -concep ons about pastoralism by federaland interna onal policymakers and the

marginaliza on of ASAL communi esfrom o en distant policymakers. Thatmarginaliza on has also contributed toincreased insecurity and the breakdownof tradi onal con ict resolu on mecha -nisms. Governance issues are therefore adeeper cause of many of the problems inthe region.

Despite these problems, there ares ll some posi ve developments in theregion. Pastoralists o en emphasize

that although they are certainly vulner -able to drought, the economic oppor -tuni es of the livestock sector createsigni cant wealthwealth that could bebe er protected (for example, throughincreased mobility and be er accessto markets). 4 Moreover, high interna -

4. For a summary o Jeremy Konyndykspresentation, see page 14. See the ull presentationhere: http://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/usaid-resilience-workshop-lessons- rom-mercy-corps.

onal meat prices and substan al exportdemand in the Middle East and withinthe region itself mean that livestock is ahigh poten al sector for many (but notall) people in the Horn of Africa. Likewise

there are opportuni es for diversi ca on(for example, using irriga on and be erwater harves ng methods and engagingin various nonfarm livelihoods) and anincreasing demand for educa on, whichwould seem a necessary condi on forsuccessful economic transforma on inthe region (Headey, Seyoum Ta esse,and You 2012).

RESILIENCE 101:DEFINING ANDFRAMING RESILIENCE

In a keynote presenta on delivered atthe beginning of the workshop, JohnHoddino , deputy director of IFPRIsPoverty, Health, and Nutri on Division,explained both the concept of resilience

FIGURE 2. Number o people adversely a ected by droughts in the Horn o A rica, 19702010

Source: Headey, Seyoum Ta esse, and You (2012); estimates rom EM-DAT 2011.Notes: These estimates o the total number o people a ected are only very approximate. See Headey, Seyoum Ta esse, and You (2012) or more details.

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

12/404

and the prac ce of building it. 5 He saidthat the term resilience originally re -ferred to the abilityto [both] withstandsevere condi ons and jump back. Theterm has increasingly gained trac on invarious twen eth-century sciences, espe -cially ecology (a resilient ecosystem canwithstand shocks and rebuilding itself),psychology (coping with stress and adver -sity), and, of course, in the elds of de -velopment and disaster risk management(DRM). Development and DRM specialistsemphasize many dimensions of resilience,including social and collec ve ac on (reci -procity, trust, and social norms), economiccapital (income and savings), humancapital (educa on, health, and skills), andpoli cal capital (long-term investments,government capacity, DRM structures andplans, preparedness, and responsiveness).Some de ni ons emphasize resilienceas a process (a dynamic phenomenon)rather than a state; some see it at di er -ent levels, namely those of individuals,households, ins tu ons, communi es,ecosystems, and governments.

Building Resiliencethrough the ProductiveSa ety Net ProgrammeFrom 1993 to 2004, Ethiopia relied heavilyon emergency assistance toavert mass starva on. Althoughsuccessful to some degree, thisprac ce did not prevent assetdeple on or integrate well withongoing economic developmentac vi es that might reduce thethreat of future famine. TheProduc ve Safety Net Programme (PSNP)was created to change this by providingrecipients with a predictable source of household income either via cash trans -

5. For a summary o John Hoddinottspresentation, see page 11. See the ull presentationhere: http://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/usaid-resilience-workshop-plenary-presentation-resilience-101.

fers, food transfers, or paid labor withina public works program. This programworks in combina on with the HouseholdAsset Building Program (HABP), whichlinks people in the PSNP with the agricul -ture extension service that disseminatestechnological packages and on-farm tech -nical advice. By building ins tu ons toplan and manage public works, integra ngpublic works into woreda developmentplans and early warning systems, andworking with communi es to determinebene ciaries, the PSNP builds resilienceinto government structures and strength -ens capacity for be er governance. 6 ThePSNP is also building resilience into thenatural resource base by focusing on treeplan ng, rehabilita on of stream bedsand gullies, and terracing to prevent ero -sion.

The impacts of the PSNP can also beseen at the household level. Householdsthat received ve years of support fromthe PSNP public works programs haveseen an improvement in food security of approximately one month per year. In thedrought-prone areas where people haveexperienced two or more droughts inthe past ve years, the food security hasimproved by 0.93 months per year com -pared to those who did not par cipate

in the program for ve years. The samehouseholds experienced an improvementin livestock holdings of 0.39 tropical live -stock units (TLU) compared to those notpar cipa ng in the program (Berhane etal. 2011; Coll-Black et al. forthcoming).

6. A woreda is a division o local government similarto a county.

The impacts of including the HABPwith the PSNP are even more pro -nounced. The months of food insecuritydecrease by an addi onal half a monthper year, and households accumulate anaddi onal 0.6 TLU more than they ac -cumulated through the PSNP on its own(1 TLU under PNSP+HABP compared to0.4 TLU with PSNP alone). The HABPs addi onal impacts are thought to be the re -sult of the program providing householdswith (1) a safety net (in the form of cashor food transfers) during mes of shock,(2) working capital through public worksprograms, and (3) technical exper se.

THE IMPLICATIONSOF RESILIENCE

Various speakers and discussantsat the workshop deliberated onthe implica ons of a resilienceparadigm, which would involve rede -signing development strategies in theHorn of Africa, bridging the gaps amongtradi onally dis nct development andDRM ac vi es, monitoring and evalua on(M&E), and opera ons. 7 John Hoddinobegan by emphasizing that while muchof what USAID and others already do tswithin the resilience paradigm, the false

and discredited relief and developmentdichotomy s ll persists in USAID and otherins tu ons. A range of speakers alsoemphasized that since resilience is a pro -cessrather than a state to be achievedwithin a set meframeachieving it

7. See additional discussion on page 17.

You are dealing with very poor households in poor communities,experiencing requent drought. Yet, despite that, the program isimproving ood security and asset holding. In other words, we beginto see that this program is improving resilience.

John Hoddinott, IFPRI

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

13/405

depends on demonstrable long-term com -mitments. 8 In prac ce this means longer

meframes (for example, a minimum of ve years but op mally between ten and

twenty), less obsession with gradua on,and no more going it alonemorespeci cally, building stronger partnershipswith regional governments and otherinterna onal bodies.

While there was broader agreementon the value of explicitly moving towarda resilience paradigm, there was li leconsensus on what this meant in prac -

ce. USAID Administrator Rajiv Shahand various assistant administratorsemphasized the importance of internallyreorganizing the way the Agency doesbusiness by developing more e cientprocurement systems and exible fund -ing streams, improving the linkages andsynergies between relief and develop -ment, and sustaining donor commitmentin the long term.

Given the complexity of quan fyingresilience outcomes and processes, M&Ewill also be cri cal, and a en on shouldbe given to addressing the signi cantchallenges to conduc ng it in isolatedand highly mobile communi es. But howshould resilience be measured? Work -shop par cipants discussed whetherthere should mul ple indicators withperhaps one or two primary ones to cap -ture overall achievements. For example,some speakers emphasized decreaseddependence on food aid as an overalltarget while others noted the advantagesof more objec ve indicators, such asnutri on outcomes, which could indicateperformance in both acute and chronicundernutri on and food insecurity. Therewas a general consensus, however, thatthe mul ple domains of resilienceeconomic, poli cal, social, ecological,

8. See presentations here: http://agrilinks.kdid.org/library/enhancing-resilience-horn-a rica-evidenced-based-workshop-strategies-success-summary.

individual, community, and various levelsof governmentnecessitate mul pleindicators of both the quan ta ve and

qualita ve variety.

EXPLORING THEEVIDENCE BASE INFIVE DOMAINS

In addi on to the more generic dis -cussions of the organiza onal andopera onal implica ons of a resilienceparadigm, much of the workshop fo -cused on exploring the evidence base of resilience building within the domains of economic development; natural resourcemanagement; health and nutri on; socialdevelopment; and governance, ins tu -

ons, and con ict. These delibera ons in -volved a mix of presenta ons, small-groupdiscussions, open oor plenary speeches,informa on-sharing across the variousdomains, and stocktaking of key lessons. 9

1. Economic Growth and

Trans ormationEconomic growth and transforma onwould seem to be a necessary if insuf -

cient condi on for li ing ASAL peopleout of poverty, increasing their capacityto withstand and bounce back fromshocks, and decreasing their vulner -ability to those shocks from the outset.Transforma on entails both movementsof people and resources out of tradi -

onal agriculture and herding, but also amoderniza on of those tradi onal sectorsand their accompanying technologies,physical capital forma on, and increasedhuman capital. Exis ng transforma onparadigms have largely ignored the role of resilience, however, which is a goal in andof itself, but also an instrumental factorfor asset accumula onas the literatureon poverty traps indicates (Barre and

9. See breakout session discussion summariesbeginning on page 17.

McPeak 2006; Barre , Carter, and Ike -gami 2008). In the ASAL context, there issome evidence that much of the regionstransforma on to date involves peoplefalling out of pastoralism into low-returnand highly unsustainable ac vi es, suchas rewood/charcoal collec on (Devereux2006). Thus, a push-pull paradigm may bethe best approach, with some ac ons de -signed to pull the poor into new ac vi esthat have lower, less-risky entry pointsand some designed to push them to takemore risks by building up their technicalcapacity. The Household Asset BuildingProgram (HABP) in Ethiopia is an exampleof a mul faceted push-pull approach. Itinvolves training and extension to coverskill and managerial development of poorhouseholds, rural savings and credit co -opera ves, and micro nance ins tu onson the nance side; traders and farmerson the input-technology side; improvedstorage, processing, and quality controlon the marke ng side; and strengtheningmanagement capacity on the governmentside. But there is also evidence suggest -ing limited absorp ve capacity of irriga -

on and urbaniza on, as compared tothe substan al economic poten al of thelivestock sector and its downstream valuechain ac vi es (Headey, Seyoum Ta esse,and You 2012).

In addi on to strong export growthin livestock (in Ethiopia), there have alsobeen successful emergency destockinginterven ons (Aklilu and Wekesa 2002;Catley, Aklilu, Admassu, and Demeke2007), high returns to animal healthservices and improved market access(Nin-Pra , Bonnet, Jabbar, Ehui, andHaan, 2004), and viable prospects forformalizing informal trade and increas -ing government revenue (Negassa etal. forthcoming). In short, these makethe case for a balanced developmentstrategy, something that has largely beenmissing in much of the region. There is

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

14/406

also wide acknowledgement of the in -terac ons with other resilience domains,par cularly the sustainability of thenatural resource base for livestock andcrop-based farming (and the implica onfor livelihood diversi ca on), the role of educa on and health invest -ments in economic develop -ment, and the cri cal roleof governance and con ictresolu on in the region.

There was further dis -cussion of other possibleinterven ons in the region,including index-based live -stock insurance (currently in a trial phasein Kenya), educa on investments, andtraining and extension programs. Whilethere was no consensus on the poten alof each of these interven ons, there wasgeneral agreement on the need for moreinnova ve experimenta on and learningin these se ngs, balanced with cau onin the face of o en excessive enthusi -asm.

2. Natural ResourceManagementDeple on and degrada on of the naturalresource base is a major cause of deterio -ra ng livelihoods in the arid and semi-aridlands of the Horn of Africa, so naturalresource management is an importantfounda on upon which to build resiliencein the region. The prevalence of naturalresource degrada on is mainly due to un -sustainable and unregulated produc onac vi es that decrease the provision of ecosystem services and thereby increasethe vulnerability of peoples livelihoods.Due to underdeveloped managementprac ces, weak and unenforced propertyrights ins tu ons, and common propertyresource governance, greater compe onfor resources has led to increasing inci -dences of violent con ict. In some casescon ict over resource ownership and

use has led to displacement of popula -ons to other areas, further exacerba ng

resource-related con ict. In cases wheredisplacement has not taken place, con ictarises from unequal access to resourcesby compe ng groups.

Degrada on of natural resourcesdue to overuse has led to diminishedproduc ve agricultural and livestockareas, nutrient deple on of soil, soilerosion, and declining quality of range -lands and watersheds. With the declinein input quality has come a subsequentdecline in yields and overall produc v -ity. The combined e ects of unregulatedresource compe on and degrada onhave created hazardous condi ons thatwill likely get worse without e ec veinterven ons.

Strategies and programs must im -prove resource-use rights (including landrights and grazing rights for pastoralists),protect and bolster exis ng resourcesthat are threatened by degrada on(through, for example, conserva onagriculture), and promote improvedmanagement strategies for exis ng re -sources (such as rainwater harves ng orcommercial destocking). Other successfulini a ves to protect natural resourceshave included early warning systems(although these have been plagued bypoor response me), long-term educa -

on, community-based conserva on andmanagement programs, grazing associa -

ons, and community gardens for pasto -ralist drop-outs. Examples of natural re -source management (NRM) interven ons

from other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa,including the Sahel; were noted at theworkshop, however, there was a generalconsensus that much is yet to be learnedregarding how these interven ons wouldbe applicable in the par cular arid and

semi-arid environments of the Horn of Africa.

Generally NRM has been shown towork best when integrated within mul -sectoral approachescombining eco -nomic development, improved farmingprac ces, clear incen ves, and increasedawareness and behavioral change. Inaddi on, community ownership wasiden ed as cri cal par cularly becauseof the o en high labor e orts and costsinvolved in such projects.

S ll, many knowledge gaps in NRMthat need to be lled by research remain,par cularly with regards to the con -ten ous issue of whether human andlivestock popula ons exceed the carryingcapacity of land and water resources.Many ASAL popula ons (both humanand livestock) are es mated to havemore than doubled in size in recentdecades. They are con nuing to growdespite signi cant constraints on naturalresources and mobility.

3. Health and NutritionSurveys of pastoralist community devel -opment priori es regularly uncover thatimproved health and nutri on outcomestop the list (McPeak et al. 2011; Devereux2006). This is not surprising insofar ashealth outcomes and services in ASAL

For too long we have segregated humanitarian support andactivities and development activities. We havent seen thebeauty o the possibilities that exist when we think o thesethings as a more integrated whole.

Rajiv Shah, Administrator, USAID

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

15/407

regions are far below those in highlandregions in these countries while health-related shocks rapidly diminish householdassets as the assets are instead usedto smooth out consump on changes,thereby magnifying the incidence of acutenutri on and health problems (Hoddino2006). There is also growing evidence thatmalnutri on early in childhood and duringgesta on lowers cogni ve development,achievement in school, and future earningpoten al; even temporary shocks to nutri -

onal status in early childhood can havelas ng irreversible consequences (Beh -rman, Alderman, and Hoddino 2004;Black et al. 2008).

The determinants of health and nutri -on outcomes in ASAL regions are par c -

ularly complex and mul faceted, so im -proving them will require interven onson mul ple fronts, including agriculture,livestock and livelihood programs, watermanagement, hygiene and sanita on,and disaster risk manage -ment. These interven ons,when accompanied by otherinvestments in communica -

on strategies that promoteposi ve behavior within thelocal context, have beenshown to improve nutri onoutcomes (Ber , Krasevec,and FitzGerald 2004; Faber,Jogessar, and Benad 2001; Ruel 2001).However, there is a need for more expost impact evalua ons of behavioralchange communica on methods todetermine how to improve programma csuccesses. Strategies that, by design, in -clude preventa ve methods as opposedto reac ve methods have also been moree ec ve both in cost and impact (Rueland Menon 2003).

4. Social DimensionDisintegra ng social networks have re -sulted in an erosion of tradi onal coping

mechanisms, rising ethnic strife, and aconcurrent breakdown in the structureof acknowledged means of resolving con -

icts and deriving sustainable resolu ons.While faced with uncertainty and mount -ing stress on the structure of societalrela onships, individuals have becomeincreasingly fatalis c and lack a broader,op mis c vision of the future. Surveyresults on a tudes indicate that low as -pira ons are widespread and characterizeindividuals as becoming more risk aversewhen dealing with issues pertaining tothe future (Bernard, Dercon, and SeyoumTa esse 2011). Research has shown thatbeing discouraged about posi ve out -comes in the future has led many to forgoinves ng in long-term well-being andinstead to focus on immediate survival(Bernard et al. 2011).

Discriminatory a tudes toward wom -en were also noted as having resulted insystemic undervaluing of womens role in

agriculture and other income-genera ngac vi es and womens exclusion fromaccess to resources and absence fromposi ons of importance in poli calstructures of varying complexity. Whilethere are many constraints on socialresilience in the region, it was pointedout that tradi onal coping mechanismsmust be recognized and strengthened.The need to impart new mindsets,skills, and facilita on mechanisms wasalso iden ed. Moreover, public safetynets such as the Produc ve Safety NetProgramme are important because they

have tremendous bene ts to society thatoutweigh the social costs associated withsuch programs.

Other interven ons that were men -oned as being e ec ve include mental

health and psychosocial support servicesin Dadaab, which involved case manage -ment sessions, community-based psychosocial ac vi es, life skills training, savingsand loans groups, support in se ng upself-help groups and revitaliza on of tradi onal resources, training in problemsolving, community health and nutri onprograms, strengthening social networks,peacemaking, value chain development,and natural resource management. Toboost social resilience, there is a needto address the immediate stressors orcauses of trauma; iden fy posi ve andhopeful role models; establish oppor -tuni es for future empowerment; buildsocial networks and ins tu ons to helpcope with challenges; and maintain links

with services, markets, and economicopportuni es. Some of the hindrances tosocial resilience pointed out at the work -shop include insu cient a en on to psy -chosocial stressors and trauma, poli calinstability, unresolved con ict, isola on,

and dissolu on of social networks.

5. Governance, Institutions,and Building PeaceGovernance and ins tu ons in the Hornof Africa were described as a fundamen -tal centerpiece to enhancing resiliencebut signi cant challenges were acknowl -

This year there was a crisis comparable to 20022003 in Ethiopia, andthere [were] 4.6 million bene ciaries. Thats a lot less than the 14.6million that [had to be] covered in 20022003. We can de nitely saythat PSNP reversed the trend to destitution across the areas it wasworking in.

John Graham, USAID/Ethiopia

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

16/408

edged, including the lack of coordina onand ability to enforce policies of variousde jure ins tu ons. There was recogni onthat several levels of governance exist(community, subna onal, na onal, andregional) and that these need to be inharmony while maintaining na onal sov -ereignty to e ec vely enhance resilienceof the whole region. Two important levelson which posi ve changes haverecently begun are the countrylevelthrough the Comprehen -sive Africa Agriculture Devel -opment Programme (CAADP)frameworkand the regionallevel, where governance ins tu -

ons under the African UnionsIntergovernmental Authority onDevelopment (IGAD) are comingtogether with developmentpartners to facilitate trade andinvestments in the ASALs. These ins tu -

ons have allowed for a country-led ap -proach that can also be matched with theregional development agenda. A summitheld in Nairobi in September 2011 signi -

ed the level of poli cal commitment thathas arisen to bu ress the regional ins tu -

ons to facilitate trade, investments, andsecurity at the regional level. The involve -ment of the African Union and na onalgovernments at this heightened level hasset the stage for concrete ac on to follow.Of par cular concern were the con nuingsecurity challenges in Somalia, which re -main despite several governments withinthe region a emp ng to address them.

At the subna onal levels the pri -mary source of local con ict was said topertain to livestock raids and disputesover grazing and water-use rights alonglivestock trading routes, which are in es -sence a coping mechanism for livestocklosses, par cularly during drought whenpastoralists have to traverse extensiveareas to feed their livestock and conducttrade. Hence, approaches that seek to

address both causes and consequencesof con ict with peace-building e orts(namely, dialogue and dispute-resolu ontraining) and tools (including economicdevelopment, natural resource manage -ment prac ces, and youth interven ons)were said to have had the most success.One speaker highlighted the importantrole of nongovernmental organiza ons

and presented a hybrid model of peace-building tools that incorporated dispute-resolu on training that links customarycon ict resolu on methods with supportfor reconcilia on processes, therebyleading to localized peace agreements atthe community and subna onal levels.The need to couple these tools with eco -nomic opportuni es was stressed, sincemuch of the localized con ict arises fromcompe on for economic opportuni esand access to resources.

MOVING THE AGENDAFORWARD

The workshop culminated in severaldelibera ons on how best to movethe resilience agenda forward inthe region. There was real consensus thatresilience programming had value added,par cularly if it resulted in long-termstrategies that were process oriented andcapable of bridging the divide betweendevelopment and relief. Among opera -

ons and implementa on partners, there

was also some consensus on what kindsof steps could make resilience program -ming an e ec ve reality. First, it wasargued that there might be real value ina common framework to help guide boththe design and implementa on. Concep -tually, this could entail re ning the typeof framework that the UK Department forInterna onal Development has already

developed to include addi onal emphasison di erent levels and domains in whichresilience operates. 10 Opera onally it maymean something similar to the crisismodi er approach used in the Pastoral -ist Livelihoods Ini a ve in Ethiopia. Thisapproach allowed relief resources to beprogrammed through a standup develop -ment mechanism in a way that assuredcomplementarity of relief and devel -opment programming. The la er waspar cularly viewed as useful in establish -ing that development and relief ac vi esshould never undermine each other.

A common framework will also needa signi cantly more rigorous monitoringand evalua on (M&E) system, comprisedof greater e orts to collect indicatorsand to establish impact through morerigorous research and evalua on. Whilethere was no consensus as to what anideal summary indicator of resilienceisor whether such an indicator isneededthere were many produc ve

10. See Andrew Prestons presentation summaryon pages 1516.

The workshop rein orced that we have a critical moment o alignment: heads o state, regional institutions, UN agencies,nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector have allconverged in their understanding that resilience is critical as we seek

to reduce su ering and increase the ability o amilies to survive theinevitable shocks o drought, foods, and other natural disasters. Wehave the tools to address the challenges ahead, but it is clear thatnone o us can succeed alone.

Nancy Lindborg, USAID

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

17/409

ideas on which indicators suited whichresilience domains. In health and nutri -

on, M&E systems are highly developed,for example, and largely consist of well-established physical indicators. Ingovernance and con ict thereis a greater need for qualita veindicators, and where possiblethe development of more ob - jec ve quan ta ve indicators(such as number of violentcon icts). In natural resourcemanagement, indicators of technologyuptake, con ict incidences, aerial data,and geographic informa on systems dataare all relevant. Economic developmentis perhaps the most challenging domain,given the di cul es of systema callysurveying mobile and dispersed popula -

ons and of quan fying livestock, theirmost important asset.

Beyond M&E, there is clearly abroader need to strengthen and expandthe evidence base for policymaking inthe Horn of Africa, where some of themost fundamental ques ons remainunanswered.

1. What has actually been happeningin the region in terms of economicgrowth, poverty, and asset owner -ship (par cularly herd sizes)?

2. To what extent are human andanimal popula on growth strainingthe carrying capacity of the regionsnatural resource base?

3. To what extent should resourcesbe devoted to pastoralism versusother sectors?

4. How should development strate -gies vary across di erent regions,given the heterogeneity of peoples

and places in the Horn?5. To what extent do cultural and

behavioral factors constrain in -vestment, entrepreneurship, andcoopera on in the region?

In truth, we have quite incompleteanswers to all of these ques ons andmany others. So, how can opera ons inthe region receive be er support fromresearch ins tu ons, such as the CGIARConsor um, land grant universi es in theUnited States, and educa onal ins tu -

ons in Africa? Indeed, while there arealready e orts underway to provideshort term assistance on this front, US -AID and other development partners alsoneed to develop research capacity anddemand in the long run. Research shouldalso help improve program learning.

Some workshop par cipants felt thatthere was too much emphasis on successstories and not enough on failures, whichcan also be instruc ve. Similarly, a be erunderstanding of the adapta ons thatoccur in moving from strategy and pro -gram design to program implementa onwill provide opportuni es to learn andiden fy examples of adap ve responses.However, it was also stressed that manyimpact assessments and evalua ons leadto evidence that is not always translatedinto program design or implementa onguidance. Indeed, one ac vity for thenear future is to engage the research

community in dra ing technical paperssummarizing the long-term research al -ready carried out in the Horn of Africa onthe e ec veness of various approaches.

Finally, there was a consensus that

greater e ec veness entails tackling theproblem at scale, working more closelywith na onal governments and devel -opment partners, being there for thelong haul, and developing both greater

exibility in funding streams and moree cient procurement mechanisms. Inher blog post about the workshop, NancyLindborg, assistant administrator of USAIDs Bureau for Democracy, Con ict,and Humanitarian Assistance, noted that,The workshop reinforced that we havea cri cal moment of alignment: heads of state, regional ins tu ons, UN agencies,nongovernmental organiza ons, and theprivate sector have all converged in theirunderstanding that resilience is cri -cal as we seek to reduce su ering andincrease the ability of families to survivethe inevitable shocks of drought, oodsand other natural disasters. We have thetools to address the challenges ahead,but it is clear that none of us can succeedalone. The next step is to make workingtogether a reality.

Donors have di erent priorities, expertise, and resources; creating aconsensus around a speci c agenda is not only straight orward butthe PSNP has shown that it is possible and can be e ective.

Alemayehu Seyoum Ta esse, IFPRI

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

18/4010

Aklilu, Y., and M. Wekesa. 2002. Drought,Livestock and Livelihoods: Lessons from

the 19992001 Emergency Response inthe Pastoral Sector in Kenya . London:Network.

Barre , C., S. Osterloh, P. D. Li le, and J.G. McPeak. 2004. Constraints Limit-ing Livestock Marketed O ake Ratesamong Pastoralists. Research Brief 04-06-PARIMA. Davis, CA, US: GlobalLivestock Collabora ve Research Sup -port Program (GL-CRSP), University of CaliforniaDavis.

Barre , C. B., and J. G. McPeak. 2006. Pov -erty Traps and Safety Nets. In Poverty,Inequality and Development , edited byA. de Janvry and R. Kanbur, 131154.New York: Springer.

Barre , C. B., M. Carter, and M. Ikegami.2008. Poverty Traps and Social Protec-

on . Washington, DC: World Bank SocialProtec on.

Behrman, J. R., H. Alderman, and J. Hoddi -no . 2004. Malnutri on and Hunger.In Global Crises, Global Solu ons , edit -ed by B. Lomborg, 363420. Cambridge,UK: Cambridge University Press.

Berhane, G., J. Hoddino , N. Kumar, and A.Seyoum Ta esse. 2011. The Impact of Ethiopias Produc ve Safety Nets and Household Asset Building Programme:20062010 . Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Bernard, T., S. Dercon, and A. SeyoumTa esse. 2011. Beyond Fatalism: AnExplora on of Self-E cacy and Aspira -

ons Failure in Ethiopia . DiscussionPaper 1101. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Ber , P. R., J. Krasevec, and S. FitzGerald.2004. A Review of the E ec veness

of Agriculture Interven ons in Improv -ing Nutri on Outcomes. Public HealthNutri on 7 (5): 599609.

Black, R. E., L. H. Allen, Z. A. Bhu a, L.E. Caul eld, M. de Onis, M. Ezza ,C. Mathers, et al. 2008. Maternaland Child Undernutri on: Global andRegional Exposures and Health Con -sequences. The Lancet 371 (9608):243260.

Catley, A., Y. Aklilu, B. Admassu, and F.Demeke. 2007. Impact Assessments of

Livelihoods-Based Drought Interven-ons in Moyale and Dire Woredas .

London: Orana.Coll-Black, S., D. O. Gilligan, J. Hoddino ,N. Kumar, A. Seyoum Ta esse, andW. Wiseman. 2012. Targe ng FoodSecurity Interven ons in Ethiopia: TheProduc ve Safety Net Programme.In Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia:Progress and Policy Challenges , editedby P. Dorosh and S. Rashid. Washington,DC: IFPRI.

Devereux, S. 2006. Vulnerable Livelihoodsin Somali Region, Ethiopia . Brighton,UK: Ins tute of Development Studies,University of Sussex.

DFID (UK Department of Interna onalDevelopment). 2011. De ning Disaster Resilience: A DFID Approach Paper .www.d d.gov.uk/Documents/publica -

ons1/De ning-Disaster-Resilience-DFID-Approach-Paper.pdf.

Faber, M., V. B. Jogessar, and J. Benad.2001. Nutri onal Status and DietaryIntakes of Children Aged 25 Years andTheir Caregivers in a Rural South AfricanCommunity. Interna onal Journal of Food Sciences and Nutri on 52 (5):401411.

Flintan, F. 2011. The Poli cal Economy of Land Reform in Pastoral Areas: Lessonsfrom Africa, Implica ons for Ethiopia.Paper presented at the Interna onalConference on the Future of Pastoral -ism, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, March2123.

Hashi, A. M., and A. Mohamed. 2010. Live Animal and Meat Export Value Chains inDjibou and Somalia . ACTESA Working

Paper. Alliance for Commodity Trade inEastern and Southern Africa.

Headey, D., A. Seyoum Ta esse, and L. You.2012. Enhancing Resilience in the Hornof Africa: An Explora on into Alterna -

ve Investment Op ons . IFPRI Discus-sion Paper 1176. Washington, DC, andAddis Ababa, Ethiopia: IFPRI.

Hoddino , J. 2006. Shocks and TheirConsequences across and within House -holds in Rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Development Studies 42 (2): 301321.

Mahmoud, H. 2006. Innova ons in Pasto -ral Livestock Marke ng: The Emergence

and the Role of Somali Ca le Traders-cum-Ranchers in Kenya. In Pastoral Livestock Marke ng in Eastern Africa:Research and Policy Challenges , editedby J. G. McPeak and P. D. Li le, 129-144. Warwickshire, UK: IntermediateTechnology Publica ons.

Maystadt, J. F., A. Mabiso, and O. Ecker.2011. Clima c Variability, Livestock and Con ict in Somalia . Washington, DC:IFPRI.

McPeak, J. G., P. D. Li le ,and C. Doss.2011. Risk and Social Change in an

African Rural Economy: Livelihoods inPastoralist Communi es . New York:Routledge.

Nin-Pra , A., P. Bonnet, M. Jabbar, S. Ehui,and C. Haan. 2004. Bene ts and Costsof Compliance of Sanitary Regula onsin Livestock Markets: The Case of RiValley Fever in Ethiopia. Paper pre -sented at the 7th Annual Conference onGlobal Economic Analysis, Washington,DC, June 719.

Negassa, A., S. Rashid, B. Gebremedhin,and A. Kennedy. 2012. Livestock Pro -duc on and Marke ng. In Food and

Agriculture in Ethiopia: Progress and Policy Challenges, edited by P. Doroshand S. Rashid. Washington, DC: IFPRI,forthcoming.

Ruel, M. T. 2001. Can Food-Based Strate-gies Help Reduce Vitamin A and IronDe ciencies? Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Ruel, M. T., and P. Menon. 2003. Childcare,Nutri on and Health in the Central Pla -teau of Hai : The Role of Community,

Household and Caregiver Resources .Washington, DC: IFPRI.

USAID (US Agency for Interna onal Devel -opment). 2011. Ongoing FY2011 USG

Assistance to the Horn of Africa. Ac-cessed July 20, 2012. h p://transi on.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_as -sistance/disaster_assistance/countries/horn_of_africa/template/maps/fy2012/hoa_10072011.pdf.

REFERENCES

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

19/4011

Resilience 101 John Hoddino , Senior Research Fellow,IFPRI Resilience has tradi onally been un -derstood in two di erent ways. In onesense, resiliency, as adopted from theecological literature, is about tolera ngdisturbance without collapse. In psychol -ogy, however, resilience is portrayed in aslightly more nuanced way and is de nedas somebodys ability to bounce backfrom shock or stress. In the psychologicalsense, resiliency is therefore a processand not an outcome.

There are a number of commonali esthat can be found in the various de ni -

ons of resilience that can guide the waywe understand it. First, resiliency can beseen at di erent levels and in di erentdomains such as the individual, house -hold, or the ecosystem. People shouldalso be able to adapt to adverse eventsor shocks without permanent conse -quences. We must also remember thatresiliency is not just about economicsand requires the development of govern -ment ins tu ons, building appropriatesocial structures, maintaining a naturalresource base, and developing humancapital (health, nutri on, educa on).Finally, ini a ves that build resilienceinvolve reducing the likelihood andseverity of adverse events, enhancing themagnitude and speed of the response tocope with shocks, and diminishing theimpacts of adverse events.

The Produc ve Safety Net Programme(PSNP) is an example of building resil -ience at scale. From 19932004, Ethiopiarelied heavily on emergency assistanceto avert mass starva on and althoughsuccessful to some degree, this did notprevent asset deple on or integrate wellwith ongoing economic developmentac vi es that might reduce the threat

of future famine. The PSNP was createdto change this by providing recipients

with predictable cash transfers, foodtransfers, or paid labor within a pub -lic works program to generate regularincome. This program is complementedby the Household Asset Building Program(HABP). The HABP ensures that people inthe PSNP receive technological packagesand on-farm technical advice through anagriculture extension service. Also, thePSNP builds resilience into governmentstructures and improves governance ca -

pacity by construc ng ins tu ons to planand manage public works, integra ngpublic works into woreda developmentplans and early warning systems, andworking with communi es to deter -mine bene ciaries. The PSNP also buildsresilience into the natural resource basethrough an emphasis on plan ng trees,rehabilita ng stream beds and gullies,and terracing to prevent erosion.

Drawing on the experiences of PSNP,

USAID could improve its resiliencyprogramming by beginning to be erintegrate relief programming with devel -opment ini a ves. Addi onally, buildingresilience is a process and as such it re -quires long-term commitment especiallygiven that the impacts of many resilienceprograms are not seen un l ve or moreyears a er the program began. Withoutthat long-term commitment, expec ngmutual commitment from partners isunrealis c. USAID must also con nue towork in partnership with other donorsand governments given the magnitudeof these programs and the size of theinvestment.

We have a strong evidence base avail -able for a number of programs designedto strengthen resilience. This providesimportant insights into what worksand what does not work both strategi -

cally and programma cally. This sessionhighlighted three programs that have

achieved results.

Arid and Marginal LandsRecovery Consortium(ARC) Program in KenyaShep Owen, Regional Director, Food for the Hungry The Arid and Marginal Lands RecoveryConsor um (ARC) program in Kenyadecided that with the right investmentsthere was the poten al for posi vechange in the pastoralist areas. This proj -ect strove to increase agricultural produc -

vity, to protect and diversify householdasset bases, and to strengthen livelihoodop ons to increase household purchasingpower. By making strategic investmentsin crea ng livestock markets, the projectensured that sales of US$185,000 in 2005(the rst year of the program) quadrupledto reach US$850,000 annually. In addi on,sales have been surprisingly buoyant dur -ing the latest drought. Likewise, marketprices for livestock have gone up due tokey contribu ons from the program toimproving community veterinary services,raising the quality of animals, regular -iza on of market days, and transpar -ent market informa on. The ac vity of the market indicates that with the rightinvestments, such as market crea on andother services, pastoralists are willing tosell animals.

The program has provided a posi velearning opportunity. The engagementwith the private sector was essen al inproviding credit and stable demand frombuyers to maximize market opportuni -

es. The accessibility of the market isalso important, and the construc on of a main road by the Kenyan governmentmay have made a signi cant contribu -

on to the success of the project. With

PLENARY SESSION NOTES

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

20/4012

capacity in the region low, the long-termengagement of the program with com -munity workers, the private sector, andpastoralists also was essen al to improv -ing the provision and usage of technicalservices such as veterinary care, savingsand loans programs, and business opera -

on. There is, however, s ll a need forbe er monitoring and evalua on of theproject, switching the focus from inputsand outputs to outcomes and impact.Achieving this will require a harmoniza -

on across donors and more exibility.

Disaster Risk Reduction/Hyogo Framework Harlan Hale, Principal Regional Advisor

for Southern Africa, O ce of US ForeignDisaster Assistance, USAIDThe USAID O ce of US Foreign DisasterAssistance implements a disaster riskreduc on program to targetdisaster-prone areas. It is fo -cused on reducing losses ratherthan increasing incomes, inalignment with the UNs Inter -na onal Strategy for DisasterReduc on Hyogo Framework.The Southern Africa Regionaldisaster risk reduc on pro -gram comprises mul ple components,all of which cater to the southern Africanenvironment. The rst of these focuseson conserva on agriculture, a prac ce inwhich soil llage is reduced, causing resi -dues to remain on the soil surface. Thiscreates mulch that reduces weeds andgroundcover that reduces moisture losses.The program also emphasizes small-scalewater harves ng and irriga on to extendthe growing season, regulate variablerainfall, and allow for diversi ca on out -side of rainy seasons. Through this worksmallholders are seeing an addi onalthree to four months of produc vity dur -ing the dry season and no longer need tofocus as much e ort on charcoal and brick

making, which signi cantly degrade theenvironment when prac ced on a large-scale. Given the addi onal produc vity,farmers are becoming more food secureand are able to dedicate more money toschool fees and diversify into other assetssuch as livestock or businesses.

Through crop diversi ca on, anothercomponent of the program, families haveincreased the diversity of their plots,which now include more drought-toler -ant varie es and leguminous species thatimprove soil fer lity and help to increaseprotein intake and diversify diets. Thechallenges that the communi es nowface have shi ed from food scarcity topost-harvest losses, the development of value chains for legumes and hor culturecrops, and the lack of business skills.These challenges are important and willbe addressed with addi onal support.

Pastoralist LivelihoodInitiative in Ethiopia

Abdifatah Ismail, Somali Regional StatePresident Advisor on Humanitarian and Development, Government of EthiopiaThe 19992000 drought in the Somaliregion of Ethiopia showed the need for alarge-scale ini a ve to improve the rateat which food and nutri on assistancewas provided in mes of need. Whendrought again came in 20022003, thehumanitarian response rate had improvedbecause of intragovernmental coordina -

on, but there was s ll a signi cant lossof animalsthe main livelihood of thepopula on. The Pastoralist Livelihood Ini -

a ve (PLI) was created to make a strong

link between emergency response anddevelopment, on the principle that emer -gencies should not undermine long-termprogress. The Ini a ve has chosen tofocus on saving livelihoods by maintainingthe asset base of pastoralists and reduc -ing chronic dependence on humanitarianassistance.

There have been several componentsthat have contributed to the programssuccess. First, the program is stronglylinked to early warning systems. Thisallows the ini a ve to respond faster toshocks and trigger livestock destockingprograms and the provision of emergen -cy water and fodder provision. The verysuccessful destocking programthe rstof its kind in Ethiopiabegan in 2006and in that year alone was responsiblefor the purchase of 100,000 animals.Fostering linkages between the highlands

and the lowlands has also improved mar -ket linkages and the commercial o -takeof animals. The program has also foundthat cereal banks are an e ec ve tool tostabilize grain prices and that by workingwith pastoralist communi es it is pos -sible to establish grazing reserves.

The PLI has also partnered with Tu sUniversity to implement a system of monitoring and evalua on, which has ledto the crea on of a best prac ces guideadopted by the Ethiopian government.In addi on, rigorous academic impactevalua on has shown that the PLI hasbeen a very e ec ve use of resources inthe region, with a bene tcost ra o of 44 to 1.

Weve concluded that pastoralism is a viable livelihood and thatwith the right investments in the area, the arid and marginal landso Kenya can not only begin to overcome the trend o perpetual

decline, but they can grow and contribute signi cantly to nationalgrowth. Shep Owen, Food or the Hungry

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

21/4013

Keynote AddressDr. Rajiv Shah, Administrator, USAIDThe best way for the development com -munity to demonstrate what has beenlearned from past crises is through ourac ons and responses to the present crisisin the coming months and years. Thiscrisisthe worst in a long me, a ec ngmore than 13 million peopleis a mani -festa on of weak and abusive governancein Somalia, drought, and low-performingagriculture in the region. This has led toacute hunger, loss of livestock and assets,and displacement not only in Somalia but

in other countries in the region.The US government has been able

to mount a signi cant humanitarianresponse, which accounts for more than50 percent of the global total. Some of that response has come in the form of improved and for ed foods targetedespecially toward women and children.This food aid response has helped to re -duce malnutri on rates over the last vemonths, in some places to pre-famine

levels. We have also seen a response inAl-Shabab-controlled areas, which manythought, given the challenges, was notpossible. This has been in large partbecause of local partners.

The resiliency agenda must includeother types of interven ons that makeuse of modern technology. We have seenthe success and uptake of index-basedlivestock insurance provided by theprivate sector that relies on independent

veri ca on through satellite imageryto trigger payout. We have also seenhow low-cost, high-yield public healthinterven ons can be equally, if not more,e ec ve at preven ng fatali es in mesof crisis. The US Feed the Future Ini a -

ve has tried to build on this, providingnot only emergency assistance but also,together with FAO, providing produc veagricultural technologies. For far too longwe have segregated these two approach -

es and not realized the poten al syner -gies of these two things as an integratedwhole.

The US government is commi ed tousing its resources to make sure that wedemonstrate that we have learned a lotas we recover from the crisis in the Hornof Africa. We intend to invest resources,planning e orts, and our intellectualleadership in building a resilience strat -egy that is robust, that is country-owned,that connects to and is a part of our Feedthe Future program and agricultural de -velopment strategies country by country,and that really does represent the bestintegrated thinking of all par es and allpartners.

The Nairobi Strategy:Enhanced Partnershipto Eradicate DroughtEmergenciesH.E. Elkanah Odembo, Ambassador, Em -bassy of the Republic of Kenya, Washing -ton, DC

During a regional mee ng in September2011 to discuss the current drought,several heads of state admi ed that theyhave not made su cient investments inthe semiarid and pastoralist communi esin the Horn of Africa. There was also wideacknowledgement that there is a need forlong-term programming. Within a ma erof weeks Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan,and Djibou had developed medium- andlong-term plans to begin to address the

longstanding crisis in the region.This mee ng was followed by another

in Djibou three months later to rea rmdevelopment commitments and outlineprogram strategies. During this mee ng,heads of state agreed to support theIntergovernmental Authority on Develop -ment (IGAD) Climate Predic on and Ap -plica ons Center (ICPAC), invest in be erwater management and harves ng prac -

ces, improve ecosystem management

to build resilience in natural systems,and integrate the Drought Risk Reduc onframework and climate change adapta -

on into development planning andresource alloca on frameworks.

D eveloping a C ommon

a genDa for B uilDing

r esilienCe : l essons i DentifieD from r eCent

e fforts anD g aps

r emaining

Consensus Building andthe Productive Sa ety NetProgramme

John Graham, Senior Policy Advisor,USAID/EthiopiaThe formula on and development of many of Ethiopias food security programshas o en come on the heels of a crisis.The 20022003 drought a ected nearly14.6 million people in Ethiopia and wasthe impetus for the forma on of thePSNP and the PLI. Similar programs werestarted in the produc ve highland areas in2008 to improve produc vity and combatfood price in a on during the food crisis.With the latest crisis in the Horn, there isnow the opportunity to create pla ormsfor disaster risk reduc on.

The experience of working to developthe PSNP o ers many lessons that cannow be applied elsewhere. First, analysisformed an integral part of the formula -

on of the project and that prepara onhelped to consolidate viewpoints andcreate a common agenda. Second, fordevelopment partners and donors, sup -por ng the PSNP meant a combina onof direct budget support and grants toimplementa on partners. Direct budgetsupport provided the Ethiopian govern -ment with ownership of the project whiledirect funding to implemen ng partnersallowed development partners like USAID

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

22/4014

exibility in their partner funding.The results of the project can be seen

at scale. Whereas in 20022003 theprogram supported nearly 14.8 millionindividuals, with the latest crisis therewere only 4.6 million bene ciaries. With -out the PSNP these individuals wouldhave been given food aid but it wouldhave been disorganized and late andthere would have been a deteriora onof livelihoods. With the PSNP in place, ashas been shown by Berhane et al. (2011),we can see that peopleactually have accumulatedassets even in the face of crisis.

While the PSNP did notaccomplish everything,we can de nitely say thatPSNP reversed the trend to des tu onacross the areas it was working in. Thatsa huge number of households. The PSNPwas a huge step forward.

The Links betweenResilience, Confict, andFood Security

Jeremy Konyndyk, Policy and Advocacy Director, Mercy CorpsThe second presenta on by JeremyKonyndyk addressed the nexus betweencon ict and food security and its impacton resilience. The presenta on outlinedthese linkages and how they manifestthemselves in the Horn of Africa whilealso addressing how this issue could bemore fully addressed through changes tothe focus of policies and programs.

Frequently in the development para -digm, con ict is seen as an exogenousfactor and not necessarily somethingthat we can address. When householdsfear con ict or violence, seasonal migra -

on and herd spli ng become di cult,as does accessing markets for destockingor purchasing nonfarm goods.

Mercy Corps approach is a hybrid

of peace-building tools such as disputeresolu on training, linking customarycon ict resolu on forums with formalins tu ons, and suppor ng reconcili -a on processes that lead to localizedpeace agreements. These are linked withdevelopment tools, which o en addressthe root causes of con ict such as thelack of economic opportuni es or naturalresource scarcity.

While the outcomes presented arepreliminary, communi es thus far have

reported that, because of the peace pro -cess, elders are be er able to nego ateshared access to scarce grazing resourcesand that pastoralists are able to enjoygreater freedom of movement and fewercon ict-related obstacles when access -ing pasture and water. Likewise, familiesare be er able to access markets, whichincreases their trade opportuni es com -pared to those of the control groups thatwere not targeted by the program. Thishas provided them with greater econom -ic opportuni es and alterna ve coping

strategies in mes of crisis.

Some Lessons romEthiopias PSNP

Alemayehu Seyoum Ta esse, ResearchFellow, IFPRI

The Produc ve Safety Net Programme hasprovided an example of how emergencyaid and programs to enhance resilienceand promote development can be in -cluded in a large-scale program. It has alsoprovided an example of how a programcan work at scale, covering nearly 8 mil -lion people and 300 woredas , with theright mixture of commitment and coordi -

na on by government and developmentpartners.

There are several principles whichcontributed to the success of the PSNP.Coordina on between the nine develop -ment partners and the various ministriesof government was essen al in creat -ing agreement on the framework of thePSNP and a common agenda. By workingtogether in partnership, the Ethiopiangovernment was able to internalize thePSNP and assume ownership. This fur -

ther contributed to the integra on of thePSNP within the broader food securityagenda and the na onal developmentplan.

Monitoring and evalua on (M&E)were also a part of the ini al design andmutual understanding of the PSNP. Withgovernment support, the M&E frame -work was able to integrate the exper seand capacity of the na onal sta s calagency and external evaluators. Thelearning opportunity that came out of in -terim evalua ons also allowed the PSNPto adjust the program to be er targetthose in need.

p athways o ut of p overty :

e xploring the l inkages

Between r esilienCe anD

e ConomiC g rowth

The Value Chain ModelSteve McCarthy, Senior Technical Direc -tor, Enterprise Development, ACDI/VOCAEconomic growth can be achieved by thegrowth of industries and the private sec -tor but economic growth alone is insu -cient for reducing poverty unless the poor

Resilience implies that transitory adverse events should not havepermanent consequences, and that agents can adapt to adverse events.

John Hoddinott, IFPRI

-

7/31/2019 Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa

23/40

example: survive, cope, recover, learn,transform

CAPACITY

R e s i l i e n c e t o w h a t ?

Bounce back be er

Bounce back

Recover, but worse than before

Collapse

SYSTEMOR

PROCESS

SHOCKS

STRESSES

E X P O S U R E

S E N S I T I V

I T Y

A D A P

T I V E

C A P A

C I T Y

example: social group, region,ins tu on

CONTEXTDISTURBANCE

R e s i l i e n c e o f w h a t

?

REACTIONcapacity to deal with disturbance

example: natural hazard, conict, insecurity,food shortage, high fuel prices

Source: DFID 2011.

15

are linked to growth opportuni es. Poorhouseholds tend to be more isolated fromthe mainstream economy and as a conse -quence do not have the ability to maxi -mize produc vity of their land and labor.They o en lack non-physical assets such

as social rela onships, skills, and educa -on, which can be important to par cipat -

ing in new economic opportuni es.We therefore need push strategies

that help vulnerable households to par -cipate in value chains through capacity

building to take advantage of opportuni -es and to improve household ability to

take more risks. Households and privatesector rms must remove key constraintsand take advantage of opportuni es to