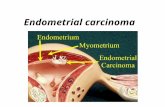

Endometrial carcinoma

-

Upload

aboubakr-mohamed-elnashar -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

209 -

download

0

Transcript of Endometrial carcinoma

Incidence

-Endometrial carcinoma is the most common

gynecologic malignancy.

-The disease predominantly affects perimenopausal

and postmenopausal women, whose median age at

diagnosis is 61 years. Only 5% of patients are

younger than 40 years.

-It is twice as common as ovarian cancer and three

times more common than invasive carcinoma of the

cervix.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Mortality

unlike ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer has a

hallmark early symptom--perimenopausal or

postmenopausal bleeding--which prompts the

physician to take an endometrial biopsy. This

biopsy leads to a diagnosis at a favorable stage in

most patients reducing mortality

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Risk Factors

Most endometrial cancers arise from a background

of endometrial hyperplasia and are the consequence

of unopposed endogenous or exogenous estrogen

on a hormonally responsive endometrium.

1. Obesity (Davies et al, 1981).

Women who are overweight by up to 22.7 kg have a

threefold increased risk for this malignancy. The

risk jumps to ninefold for women overweight by

more than 22.7 kg.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Obesity increases the risk by increasing estrogen

production and bioavailability.

A. In postmenopausal women, the ovaries and

adrenals secrete negligible amounts of estrogen.

Most estrogen is in the form of estrone, which is

produced in the peripheral conversion of

androstenedione in muscle and adipose tissue.

Increased production of estrone has been

documented in obese women (Judd et al, 1980).

B. obese women have lower levels of sex-hormone-

binding globulin, which accounts for the increased

bioavailability of circulating estrogen (Gambone et al, 1982).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

2. Total intake of calories derived from saturated or

unsaturated fats is a risk factor independent of body

weight.

A. Women reporting a high intake of animal fat and

fried food have a 2.1-fold increased risk for

endometrial carcinoma.

B. Women with a high intake of complex

carbohydrates, predominantly breads and cereals,

have a decreased risk (RR = 0.6) after controlling for

body mass (Potischman et al, 1993).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

3. History of infertility, nulliparity, early menarche, and

late menopause (Elwood et al, 1977; Kelsey et al, 1982).

4. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus are often

associated with obesity, but they may represent

independent risk factors.

5. Chronic anovulatory states, such as PCOS

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

6. Functional ovarian neoplasms, such as certain

epithelial ovarian cancers and granulosa cell tumors,

may also increase risk by the endogenous production

of unopposed estrogen.

7. In women with postmenopausal bleeding, the most

significant risk factor for endometrial cancer (and

complex endometrial hyperplasia) is age. Patients

who are older than 70 have a risk for endometrial

cancer-complex atypical hyperplasia that is six to ten

times higher than in younger women (Feldman et al, 1994).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

8. unopposed estrogen replacement therapy (Mack et al, 1976; Weiss et al, 1979).

Risk increases with estrogen dose and duration of

use. Widespread use of unopposed estrogen in the

1960s might have been responsible for the temporal

rise in the endometrial cancer rate that peaked in

1979.

The risk for endometrial cancer can be effectively

eliminated with the addition of a progestin.

Progesterone reduces estrogen-receptor synthesis

and increases the conversion of estradiol to the less

potent metabolite estrone.

Women on combined estrogen and progestin

replacement therapy actually have lower risk for

endometrial cancer than do untreated patients.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Patients on cyclic combined regimens of estrogen

and progesterone should be administered

progesterone at least 12 to 13 days each month (Paterson et al, 1980).

The trend is to use continuous combined regimens

because this eventually eliminates bleeding in most

women.

Current recommendations suggest that patients on

unopposed estrogen should undergo annual

endometrial biopsy. In addition, women who have

bleeding before day 11 of a cyclic progestin regimen

should undergo endometrial biopsy (Padwick et al, 1986).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

9. Tamoxifen has been used extensively in the

treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast

cancer in postmenopausal women. While taking

tamoxifen, these women had reductions in new

malignancies forming in the contralateral breast (Kedar et al, 1994).

Tamoxifen has antiestrogenic and estrogenic

properties. It has been shown to reduce the risk for

osteoporosis while increasing rates of endometrial

hyperplasia and neoplasia.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

The risk for endometrial cancer is reduced by

1. Combied oral contraceptive pill. (50%)

Most modern preparations are progestin dominant,

and the degree of risk reduction is related to

duration of use and total progestin dose. The

protective effect may be greatest in non- obese,

nulliparous women.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

2. Smoking:

A.It increases concentrations of sex-hormone-

binding globulin, thereby lowering levels of

bioavailable estrogen.

B. It has been linked to early menopause.

Such benefits of smoking, however, are clearly

outweighed by the marked increase in risk for lung

cancer and cardiovascular disease (Friedman et al, 1987).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

No identifiable risk factors

Not all endometrial adenocarcinomas arise as a

result of physiologic conditions of relative estrogen

excess. There is a subset of adenocarcinomas that

arise in women with no identifiable risk factors.

These tumors may be of high grade and of

unfavorable histologic type (for example, papillary

serous, clear cell, or adenosquamous variants). T

hey develop de novo, not in an environment of

endometrial hyperplasia, and are often aggressive

tumors.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Hereditary forms of endometrial cancer

Rare

including the Lynch II family cancer syndrome.

This syndrome includes nonpolyposis colorectal

cancer, ovarian, and endometrial cancer (Lynch et al, 1989).

A careful family history should always be obtained

from patients with cancer.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Clinical picture

1. The most common symptom of endometrial

cancer, abnormal vaginal bleeding, occurs in

more than 80% of patients. When this hallmark

symptom occurs in postmenopausal women, it is

dramatic, disturbing, and likely to prompt an

immediate response from patient and physician.

The amount of bleeding is not correlated with the

likelihood of cancer because even a small

amount of spotting may represent cancer .

2. Late symptoms: pain, pressure symptoms, urinary

symptoms, cachexia

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Signs:

1. The patient is usually obese, hypertensive,

diabetic, infertile with lng history of menstrual

disorders.

2. There may be pallor due to increased blood loss.

3. Palpation of the uterus:

a. Enlagement:

b. Fixation at late stages

c. Secondaries in vagina, ovary

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Screening

Cytological screening:

•50% of patients with endometrial cancer have

abnormal results on Papanicolaou smear.

•This makes the test unsatisfactory for screening.

•Evaluation of endometrial cytologic preparations has

not gained broad acceptance because of the

difficulty in interpretation (Meisels and Jolicoeur, 1985).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

1. Routine screening is not recommended

2. High risk groups:

A. Detection of endometrial cells on a Papanicolaou

smear in a postmenopausal woman indicates the

need for endometrial biopsy (Zucker et al, 1985).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

B. Gronroos et al (1993)

mass screening (Ultrasonography & endometrial

biopsy) of women, 45 to 69 years of age, who have

diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Among women with diabetes, 6.3% were found to

have neoplasia.

Among women with hypertension, 1.3% were found

to have neoplasia.

Eighty percent of women ultimately bleed, and 75%

have highly curable stage 1 disease at this first sign

of abnormality. Because of this, it is unclear how

much benefit would be gained by screening women

with diabetes mellitus and hypertension, especially

in light of the costs of screening the 90% of patients

who do not have cancer at the time of screening.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

C. Women taking tamoxifen for breast cancer have

an increased risk for endometrial neoplasms.

This increased risk is partly a result of the estrogen

agonist effects of tamoxifen on the endometrium.

However, women with a history of breast cancer are

also at increased risk for ovarian or endometrial

cancer, regardless of tamoxifen use. In addition,

some studies of women taking tamoxifen report an

excess number of malignancies that carry poor

prognoses, among them clear cell carcinoma and

papillary serous carcinoma (Cohen et al, 1993; Magriples et al, 1993).

Given these findings, yearly endometrial biopsies,

or intermittent progesterone treatment of patients on

long-term tamoxifen therapy, should be considered.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Pathology

Most forms of cancer arising in the endometrium are

adenocarcinomas.

There are distinct histopathologic types that evince

very different biologic behaviors.

Endometrioid adenocarcinomas are the most

common.

These lesions may be papillary, secretory, or

ciliated.

Squamous differentiation is a common feature.

When the squamous tissue is anaplastic, it is

designated as an adenosquamous variant. Variants

that have been described are mucinous, clear cell,

and pure squamous carcinoma.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

The degree of carcinoma differentiation may be

based on cytologic or architectural criteria. For

endometrial carcinomas, FIGO has established

architectural criteria that may be applied to most cell

types.

A grade 1 tumor is defined as a tumor that has less

than 5% solid area.

A grade 3 tumor is more than 50% solid.

Tumor grade predicts the biologic behavior of

endometrial cancer.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Well-differentiated lesions tend to be associated with

superficial invasion and have little propensity for

nodal spread.

Poorly differentiated lesions are often deeply invasive

and metastatic. Clear cell carcinoma and papillary

serous carcinoma are two particularly virulent forms

of endometrial cancer.

They represent less than 15% of all endometrial

cancers combined, but they encompass a large

proportion of the treatment failures (Kurman and Scully, 1976; Christopherson et al, 1982).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA

1) Endometrioid :

Usually diffuse thickening of the endometrial

surface

Often a shaggy, ulcerated surface with an

underlying friable white gray mass

Deep myometrial invasion and extension into the

cervix indicate more advanced disease.

Grading of the tumor depends on the architectural

features.

Well differentiated tumors are composed of back to

back glands with low nuclear grade.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

A variation of well differentiated endometrioid

carcinoma is the papillary or villoglandular type with

usually slender fibrovascular cores and lack of

stratification and nuclear pleomorphism

Poorly differentiated tumors have a solid growth

pattern. | lo mag | hi mag

Variants: secretory and ciliated

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

2) Serous:

5 - 10 % of all endometrial carcinomas.

Aggressive with tendency to deep myometrial

invasion.

Complex papillary fronds that are usually broad.

Budding and tufting of the papillae.

Often the lining cells have a high nuclear gradewith

marked nuclear pleomorphism and prominent

nucleoli.

Mitoses are common.

High propensity to invade lymphatics.

Psammoma bodiesoften present. ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

3) Clear cell:

4 % of all endometrial carcinomas.

Aggressive.

Often associated with an advanced stage of

disease and thus, poor prognosis.

Solid, tubular or papillarypatterns of growth

Large clear cells and hobnail cells.

Nuclear grade is usually high.

4) Mucinous:

Primary adenocarcinoma of endometrium in which

most of the cells contain prominent intracytoplasmic

mucin and resemble colonic epithelium. ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

5) Squamous:

Pure squamous carcinomas of endometrium are

rare.

Associated with steam treatment of endometritis in

pre-antibiotic era.

Should be diagnosed only in the absence of a

cervical primary.

6) Adenocarcinoma with squamous

differentiation:

Squamous differentiation is very common | lo-mag

hi-mag

Prognosis related to differentiation of glandular

component ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

7) Undifferentiated carcinoma:

Relatively uncommon.

Variety of patterns: small cell type with

neuroendocrine differentiation ( lo-mag| hi-mag ,

giant cell, or spindle cell types.

8) Mixed:

Combination of the types described above.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Pretreatment Evaluation

1. Complete history and physical examination should

be performed. Often, patients with endometrial

cancer are obese and have hypertension or

diabetes and possibly significant intercurrent

medical problems.

2. A complete blood count to rule out anemia

secondary to vaginal bleeding should be performed.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

3. Abnormal liver function test results may suggest

occult metastatic disease.

4. A chest x-ray should be obtained to rule out

pulmonary metastases.

5. Intravenous pyelography, gastrointestinal series,

and barium enema are not required in asymptomatic

patients. A bone scan adds little to the initial

evaluation.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

6. Magnetic resonance imaging has proven to be

accurate in the evaluation of myometrial invasion and

lymph node involvement (Yazigi, 1989).

7. Transvaginal sonography has been used to assess

myometrial invasion but with less success (Yamashita, 1993).

These modalities are expensive and less accurate

than data derived from surgical staging. They may be

helpful in evaluating patients in whom comorbid

disease precludes surgical staging, but they are not

required for surgical staging.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

8. Although originally described as a tumor marker

for ovarian cancer, serum levels of CA-125 have

been shown to be elevated among patients with

endometrial cancer (Niloff et al, 1994).

It is unusual for early-stage disease to cause an

abnormal level, and because most patients seek

treatment at an early stage, it is not indicated as a

routine test. In most studies, more than 80% of

patients with elevated CA-125 levels are found to

have extrauterine disease at the time of exploratory

laparotomy (Pastner and Mann, 1988).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Endometrial cancer is a surgically staged disease.

Therefore, imaging to assess the depth of

myometrial invasion and tumor markers to suggest

disseminated disease are not required before

exploration.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Staging

In 1988 FIGO abandoned the clinical staging system

after the completion of prospective surgical staging

trials (Boronow et al, 1984; Creasman et al, 1987).

These studies establish the importance of cell type,

histologic grade, depth of myometrial invasion, and

nodal, adnexal, or peritoneal spread as prognostic

variables.

The previous clinical staging system, which

determined uterine size and endocervical

involvement at a fractional D & C, is now used only

for patients treated with primary radiation therapy.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Surgical staging begins with a vertical abdominal

incision. Any collection of free pelvic fluid should be

aspirated for cytologic evaluation. If no fluid is

present, saline washings should be obtained.

Thorough exploration of the abdomen, including

palpation of the diaphragm, bowel mesentery, and

para-aortic nodal groups, is essential.

Biopsy specimens should be taken of suspicious

areas. Total extrafascial hysterectomy and

adnexectomy are then performed. In selected

patients, para-aortic or pelvic lymph nodes may be

sampled, and any enlarged lymph nodes must be

removed. ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Omentectomy or omental biopsy is indicated for

patients with the papillary serous variant.

Para-aortic or pelvic lymph node sampling may lead

to morbidity and may be technically difficult in an

obese patient.

Nodal involvement risk is predictable based on

histologic cell type, tumor grade, and depth of

myometrial invasion.

Stage I, grade 1 lesions with superficial invasion

rarely metastasize to the pelvic or para-aortic nodes,

whereas up to 45% of women with deeply invasive

grade 3 lesions have nodal metastasis.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Therefore, for patients with presumed stage I

endometrial cancer, gross or frozen-section

evaluation of the depth of myometrial invasion at the

time of hysterectomy is invaluable in guiding

intraoperative decision making. Lymph node

sampling should be strongly considered for patients

with presumed stage I, grade 3 lesions or for lesions

of any grade with significant myometrial invasion.

Patients with stage II or III disease or with disease of

an unfavorable histologic type should also undergo

para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling.

Vaginal hysterectomy remains an appropriate

alterna- tive to abdominal surgery for stage I, grade

1 endometrial cancer. ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Recent advances in operative laparoscopy have led

to innovative approaches to the surgical staging of

endometrial cancer. Childers and Surwitt (1993)

report their experience with laparoscopically

assisted surgical staging of endometrial cancer,

including laparoscopic nodal sampling and vaginal

hysterectomy. Preliminary data suggest that this

investigational technique is well tolerated and that it

significantly reduces hospital stays. Laparoscopy

allows for upper abdominal exploration, node biopsy,

and salpingo-oophorectomy. These procedures are

not possible using a purely vaginal approach.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Postoperative Care

After primary therapy, patients with endometrial

cancer should be examined at regular intervals with

complete physicals and Papanicolaou smears.

Frequency of visits and duration of follow-up must be

based on the likelihood for disease recurrence in

each patient. Among women with stage IA, grade 1

and stage IB endometrial cancer, hormone

replacement therapy may be initiated after informed

consent is obtained. In these patients, the risk for

tumor recurrence is low and the benefits of

replacement therapy far outweigh the risks (Lee et al, 1990).

Estrogen replacement therapy may be

contraindicated in advanced-stage, high-grade

lesions. ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Adjuvant Therapy

After surgical staging and treatment, adjuvant therapy

may be required for patients at significant risk for

disease recurrence in the pelvis or abdomen. Patients

are at high risk if they have been found to have para-

aortic lymph node metastasis or adnexal or peritoneal

spread.

Postoperative radiation to the pelvic and aortic areas

may cure up to half the patients with advanced

disease (Potish et al, 1985).

Radiation treatment of the pelvis remains

controversial. Most studies show a reduction in local

recurrences but no significant impact on survival

rates.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Prognosis

Overall, 72% of women with stage I adenocarcinoma

of the endometrium survive at least 5 years.

The 5-year survival rate falls to 56% for stage II

disease and 30% for stage III disease.

Unfortunately, only 10% of women with stage IV

lesions survive at least 5 years (Pettersson, 1988).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Recurrence

Endometrial cancer may metastasize

intraabdominally, hematologically, or through the

lymphatics. The most common site of local

recurrence is the vaginal cuff. Distant metastasis

may be seen in lung, liver, or abdomen. Most

recurrences develop within 3 years of initial

diagnosis. Distant metastasis is associated with a

grim prognosis because of a lack of effective

systemic hormonal therapy or chemotherapy.

However, an isolated vaginal recurrence, without

pelvic extension, may be effectively treated with

surgical excision or local irradiation. As many as 45%

of women with this recurrence survive 10 years (Paulsen and Roberts, 1988).

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Staging of Cancer of the Uterine Corpus

IA G123

Tumor limited to endometrium

IB G123

Invasion to 50% myometrium

IC G123

Invasion to 50% myometrium

IIA G123

Endocervical glandular involvement only

IIB G123

Cervical stromal invasion

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

IIIA G123

Tumor invades serosa and/or adnexa and/or there is

positive peritoneal cytology

IIIB G123

Vaginal metastases

IIIC G123

Metastases to pelvic and/or paraaortic lymph nodes

IVA G123

Tumor invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa

IVB

Distant metastases including intraabdominal and/or

inguinal nodes

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

Treatment of Recurrent Endometrial Cancer

Treatment of patients with distant recurrences of

endometrial cancer is challenging and rarely results

in cure. Local irradiation may control pain or disability

from focal metastases.

To control systemic disease, progestational agents or

cytotoxic chemotherapy may be used.

Response rates to progestin therapy may be as high

as 15% to 20%, particularly in well-differentiated

cancers that are more likely to be estrogen-receptor

and progesterone-receptor positive.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR

The role of cytotoxic chemotherapy in the treatment

of endometrial cancer is limited. The reported

complete clinical response rate is only 15%.

Regimens that contain platinum or doxorubicin

hydrochloride have the highest overall response

rates, but these responses tend to be short lived, and

survival is not prolonged (Park et al, 1992).

Given the toxicity associated with cytotoxic

chemotherapy, progestin treatment is a rational first

step in treating recurrent disease. Progestins have

some desirable secondary effects, particularly as

appetite stimulants, and minimal toxicity. If progestin

treatment fails, cytotoxin therapy may be considered.

ABOUBAKR ELNASHAR