emp s Ridley Sea Turtle Lepidochelys kempii ead tart P I N SAndrés Her-rera lent a copy of his...

Transcript of emp s Ridley Sea Turtle Lepidochelys kempii ead tart P I N SAndrés Her-rera lent a copy of his...

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 10(Symposium):309–377.Submitted: 7 May 2012; Accepted: 20 February 2015; Published: 28 June 2015.

Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) Head-Startand Reintroduction to Padre Island National Seashore, Texas

Charles W. Caillouet, Jr.1, Donna J. Shaver2 and André M. Landry, Jr.3

1Marine Fisheries Scientist-Conservation Volunteer, 119 Victoria Drive West, Montgomery, Texas77356-8446 USA, e-mail: [email protected]

2National Park Service, Padre Island National Seashore, P.O. Box 181300, Corpus Christi, Texas 78480-1300USA, e-mail: [email protected]

3Departments of Marine Biology, Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, and Marine Sciences, Texas AM Universityat Galveston, P.O. Box 1675, Galveston, Texas 77553 USA, e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract.— Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) is the most endangered sea turtle and is found inthe Gulf of Mexico and North Atlantic Ocean. It nests in greatest numbers near Playa de RanchoNuevo (RN), Tamaulipas, Mexico. Historically, nesting also occurred on beaches that, in 1962, becamepart of Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS) near Corpus Christi, Texas, USA. Kemp’s Ridley washeaded toward extinction when the Mexican government began protecting clutches of eggs (i.e., nests)and hatchlings at RN in 1966, but the population continued to decline. In 1974, the U.S. NationalPark Service (NPS) proposed reintroduction of Kemp’s Ridley to PAIS. Further planning by NPS,U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), Texas Parks andWildlife Department (TPWD), and Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Pesca (INP) ensued in 1977 and ledto the bi-national Kemp’s Ridley Restoration and Enhancement Program (KRREP) implemented inJanuary 1978. Its goals were restoration of Kemp’s Ridley through enhancement of nesting successand survival at RN, and reestablishment of a breeding population at PAIS. At the time, head-start(i.e., captive-rearing to sizes thought capable of avoiding most natural predators at sea) was consid-ered essential to the second goal. Tagging and marking were necessary for identification after release,and mass-tagging hatchlings was not feasible. The NMFS Galveston Laboratory, Galveston, Texas,and collaborators head-started, tagged, and released the turtles into the Gulf of Mexico. NPS andcollaborators documented nestings. We review head-start and its relationships to the KRREP andreintroduction of Kemp’s Ridley to PAIS.

Key Words.—captive-rearing; conservation; head-starting; Lepidochelys kempii; mark-recapture; release; tagreturns; translocation; transport

Introduction

Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii), also re-ferred to as Atlantic Ridley, is the most endan-gered of the sea turtles. It has existed as a speciesfor 2.5–3.5 million y (Bowen et al. 1991). Its geo-graphic range is encompassed by the Gulf of Mex-ico (Pritchard and Márquez M. 1973; Zwinenberg1977; Márquez et al. 2004; Guzmán-Hernándezet al. 2007; Pritchard 2007; Ernst and Lovich2009) and North Atlantic Ocean (Brongersma

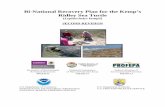

1972, 1982; Tomás and Raga 2007; Witt et al.2007; Insacco and Spadola 2010). According toNational Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) etal. (2011), most nesting takes place on beachesbordering the west-central Gulf of Mexico. Thenesting epicenter is Playa de Rancho Nuevo (RN)near the Municipio de Aldama, in the State ofTamaulipas on the northeastern coast of Mexico(Fig. 1).

Nesting also occurs on other beaches inTamaulipas, in Texas, and southward to Veracruz;

Copyright c© 2015. Chares W. Caillouet, Jr.All Rights Reserved. 309

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

Figure 1. Western Gulf of Mexico showing locations of Galveston, Padre Island National Seashore, andRancho Nuevo (map prepared by Cynthia Rubio, National Park Service).

310

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

nesting is sporadic elsewhere along Gulf of Mex-ico coasts of the U.S. and Mexico, and rare on theU.S. Atlantic coast (Márquez-M. 2001; NMFS etal. 2011). Werler (1951) was the first to report aKemp’s Ridley nesting (in 1948) in Texas, withinthe area later established in 1962 as Padre IslandNational Seashore (PAIS) near Corpus Christi,Texas (Fig. 1).

On 18 June 1947, Andrés Herrera recorded onmovie film an enormous arribada (Spanish forarrival by sea) of Kemp’s Ridley nesters near RN,representing the earliest recorded mass nestingfor this species (Carr 1963, 1967; Hildebrand1963; Burchfield and Tunnell 2004). Hildebrand(1963, 1982) estimated the size of the arribadaat 40,000 and 42,000 nesters, respectively. Carr(1967) explained how Hildebrand (1963) esti-mated the 40,000 nesters. The 40,000 estimatelater became a major benchmark among crite-ria established for Kemp’s Ridley population re-covery (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)and NMFS 1992; NMFS et al. 2011). Hildebrand(1963) noted that human exploitation of eggs atRN was a threat to survival of Kemp’s Ridleyarribadas and recommended that conservationmeasures be promulgated to prevent their extinc-tion.

Beginning in 1966, Kemp’s Ridley populationstatus was indexed by annual numbers of nests(clutches laid) at RN (Heppell et al. 2005, 2007;Márquez-M. et al. 2005; NMFS et al. 2011; Gall-away et al. 2013). Annual numbers of nests ontwo more beach segments, Tepehuajes and PlayaDos-Barra del Tordo, were later added to thepopulation index (Turtle Expert Working Group(TEWG) 2000; Márquez-M. et al. 2005; NMFSet al. 2011; Burchfield and Peña 2013; Gallawayet al. 2013).

Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de InvestigaciónesBiológico-Pesqueras, which later became the In-stituto Nacional de Pesca (INP; Guzmán del Próo2012), began protecting nests and hatchlings atRN in 1966 (Chavez et al. 1968), but annual nestscontinued to decline (Wauer 1978; FWS andNMFS 1992; NMFS et al. 2011). The decline re-

versed in 1986 (Caillouet 2006, 2010, 2014), withnests later increasing exponentially to more than20,000 in 2009 (NMFS et al. 2011; Burchfieldand Peña 2013; Gallaway et al. 2013; Caillouet2014). Unanticipated drops in combined annualnest numbers at the three index beach segmentsin Tamaulipas occurred in 2010, interrupting thepre-2010 exponential increase (Caillouet 2011,2014; Crowder and Heppell 2011; Allen 2013;Gallaway et al. 2013).

Our description of early attempts to reintro-duce Kemp’s Ridley to the lower coast of Texasis based on sources listed in Table 1. Andrés Her-rera lent a copy of his movie to Fred Lockettwho showed it at a meeting of the Valley Sports-men Club, Brownsville, Texas, in 1962, and thefilm was discussed during subsequent meetings.Club member Grover Singer began promoting theidea of starting a Kemp’s Ridley nesting colonyon South Padre Island (SPI) as an attraction forresidents and tourists. When Brownsville build-ing contractor Dearl Adams became president ofthe club, Grover Singer visited him frequentlyand further promoted the idea. Dearl Adams be-came more interested in Kemp’s Ridley afterreading the first chapter of Carr (1956). Laterhe talked with Henry Hildebrand whom he hadheard was transplanting Green Turtle (Cheloniamydas) hatchlings on the north end of Padre Is-land. Information provided by Henry Hildebrandwas enough to get Dearl Adams interested froma conservation standpoint.

In 1963, 98 Kemp’s Ridley eggs were ob-tained by Dearl Adams from Francis McDonaldwho operated a fishing camp called Campo An-drés at Barra del Tordo south of RN (see Fig. 2in Márquez-M. et al. 2005; see also Fig. 3 inBurchfield and Peña 2013). They were flownto Brownsville and transported to SPI, where91 were reburied on the beach and seven werekept in a tub of sand by Breuer (1971). Someeggs started development, but no hatchlings wereproduced. During 1964–1967, Dearl Adams andothers collected more than 5,000 eggs at RNand reburied them at SPI (Phillips 1989; Size-

311

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

Table 1. Sources covering early attempts to reintroduce Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) to the lowercoast of Texas.

Adams (1966, 1974) Phillips (1989)Breuer (1971) Sizemore (2002)Zwinenberg (1977) Burchfield and Tunnell (2004)Francis (1978) Burchfield (2005)

more 2002; Burchfield 2005). Among those as-sisting Adams were Kavanaugh Francis, Earland Olive Lippoldt, Ila Loetscher (who laterbecame recognized as the Turtle Lady of SPI)and others (Sizemore 2002; Burchfield 2005).The eggs were transported by vehicle to SPIor flown to Brownville then transported by ve-hicle to SPI. During 1964–1967, 1,227 hatch-lings were released into the Gulf of Mexicofrom SPI, with most (1,102 or 90%) released in1967 (Zwinenberg 1977; Phillips 1989; Sizemore2002; Burchfield 2005). At that time, Kemp’s Ri-dley was thought to reach maturity in 5.5–8 y(Márquez 1972; Pritchard and Márquez 1973;Francis 1978).

Volunteers set up camp in 1973 and begandaily patrols of the SPI beach from mid-Aprilthrough June to search for evidence of adult fe-males, and this continued annually through 1976.One Kemp’s Ridley nesting was documented in1974 and two in 1976. During 1974–1976, ad-ditional evidence of adult females in the areaincluded sightings of nesters, turtle tracks on thebeach, strandings of dead adult females (somemutilated), hatchling emergences, and one adultfemale caught (escaped unharmed) in a gill net.Francis (1978) believed the nestings resultedfrom the 1967 release of hatchlings, stating thatthere were no Kemp’s Ridley conservation pro-grams on SPI prior to 1967; he apparently dis-counted the combined releases of 125 hatch-lings (i.e., 1,227-1,102 = 125) from SPI during1964–1966. However, the observed nestings andother evidence of adult females in the SPI areaduring 1974–1976 could have been unrelated tothe hatchling releases by Dearl Adams and others(Donna Shaver, pers. obs.); e.g., they might have

involved surviving adult females from the pre-1966 residual population, or young adult femalesfrom early conservation efforts at RN.

Kemp’s Ridley Restoration and EnhancementProgram Planning Documents and Planners

Documents and planners.—Beginning inAugust 2010, one of us (Caillouet) obtainedinformation via e-mail exchanges, telephoneconversations, or both with six of the majorparticipants in the early planning (Table 2).We and Shaver and Caillouet (2015) alsoexamined unpublished planning documentsarchived at PAIS headquarters (copies havesince been archived at the National Park Service(NPS) Technical Information Center, Denver,Colorado):(1) NPS. 1974. Natural Resources ManagementPlan for Padre Island National Seashore. Pre-pared by PAIS Staff and Southwest Region Officeof Natural Science. Division of Natural Sciences,Southwest Region, NPS, Department of Interior,23 December 1974. Roland H. Wauer (ChiefScientist) recommended this 5-y plan, JohnW. Henneberger (Associate Regional Director,Professional Services) concurred, and T. R.Thompson (Acting Regional Director) approvedit; all were in the NPS Southwest Region, SantaFe, New Mexico.(2) Campbell, H.W. 1977. Feasibility Study:Restoration of Atlantic Ridley Turtle (Lepi-dochelys kempii) as a Breeding Species on thePadre Island National Seashore, Texas. Prelimi-nary Report (USNPS Order # PX7029-7-0505),Gainesville Field Station, National Fish andWildlife Laboratory, Gainesville, Florida. 2

312

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

Table 2. Six of the major participants in early planning of the Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempi) Restorationand Enhancement Program who were contacted by email, telephone, or both for information. (participant’saffiliations in 1977 are included).

Roland (“Ro”) H. Wauer, Chief, Division of Natural Resources Management, NPS Southwest Region, SantaFe, New Mexico, U.S.A.Jack B. Woody, Chief, Endangered Species, FWS Southwest Regional Office, Albuquerque, New Mexico,U.S.A.Edward F. Klima, Director, NMFS Galveston Laboratory, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A.James P. McVey, Chief, Aquaculture Research and Technology Division, NMFS Galveston Laboratory,Galveston, Texas, U.S.A.Peter C. H. Pritchard, Vice President for Science and Research, Florida Audubon Society, Maitland, Florida,U.S.A.Réne Márquez-M., National Sea Turtle Program Coordinator, INP, Mexico City, Mexico

November 1977. 23 p. including AppendicesI-III. Prepared for NPS Southwestern Region,Santa Fe, New Mexico.(3) NPS, FWS, NMFS, and Texas Parks andWildlife [Department; TPWD]. 1977. ActionPlan Restoration of Atlantic Ridley Turtle asa Breeding Species on Padre Island NationalSeashore, Texas 1978–1988. December 1977.36 p. including Appendices I-III.(4) NPS, FWS, NMFS, TPWD, and INP. 1978.Action Plan Restoration and Enhancementof Atlantic Ridley Turtle Populations Playade Rancho Nuevo, Mexico and Padre IslandNational Seashore, Texas 1978–1988. January1978. 30 p. including Appendices I–III.(5) NPS. 1978. Environmental Assess-ment/Review/Negative Declaration, Restorationand Enhancement of Atlantic Ridley TurtlePopulations Playa de Rancho Nuevo, Mexicoand Padre Island National Seashore, Texas1978–1988. NPS Southwest Region, February1978. 9 p. Roland H. Wauer (Chief, NaturalResources Management, Southwest Regionand Coordinator, Action Plan) recommendedthis assessment, and John E. Cook (RegionalDirector, NPS Southwest Region) concurred.

Correcting misconceptions.—None of us par-ticipated in the early planning or early years ofexecution of head-start or reintroduction. DonnaShaver became involved in the reintroduction ef-

forts by NPS at PAIS in May or June 1980. In Oc-tober 1981, Charles Caillouet became involved inhead-start efforts conducted by the NMFS Galve-ston Laboratory (hereinafter referred to as Galve-ston Laboratory). André Landry and his graduatestudents at Texas A&M University Galveston col-laborated in research related to head-start withthe Galveston Laboratory beginning in July orAugust 1984.

Upon close examination of the early planningdocuments, we became aware of misconceptionsand misrepresentations within the literature aboutthe planning for reintroduction, head-start, andtheir roles within the Kemp’s Ridley Restora-tion and Enhancement Program (KRREP; NPSet al. 1978 op. cit.). Unfortunately, we perpetu-ated some of the misconceptions and misrepre-sentations in our own publications. The literaturecontains varying accounts of early planning ofreintroduction and head-start, as well as varyingopinions regarding their adequacy as experimentsor conservation methods (see EVALUATIONS).In addition, many important details of early plan-ning have been overlooked, ignored, or forgottenuntil now. Fortunately, the unpublished planningdocuments were preserved and provide impor-tant details of early planning that can now becompared to published accounts in the literature.We focus needed attention on these historicaldocuments and the planners, because togetherthey provide necessary background and perspec-

313

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

tive essential to evaluation of reintroduction andhead-start. They show that early planning wasscience-based, thorough, ambitious, optimistic,and remarkably detailed.

Most of the literature covering Kemp’s Ridleyhead-start and reintroduction treat them as if theyare equivalent. They certainly were related butdefinitely not equivalent. Although head-startingof the 11 year-classes (1978–1988) that were pu-tatively imprinted at PAIS was essential to rein-troduction, reintroduction was not essential tohead-starting the 23 year-classes (1978–2000)that were putatively imprinted at either PAIS orRN. It is essential that readers keep this distinc-tion in mind, because most publications to whichour review refers do not make this distinction. At-tempts at imprinting were based on a working hy-pothesis that imprinting was essential to the goalof reintroducing Kemp’s Ridley to PAIS. Knowl-edge of the mechanisms of imprinting, naviga-tion, and homing in sea turtles was limited at thetime of early planning and initiation of Kemp’sRidley head-start and reintroduction (Allen 1981).Eggs and hatchlings taken for head-start and rein-troduction were intentionally exposed to environ-mental conditions that were expected to imprintthem to PAIS or RN. It also was expected that atleast some surviving females would later matureand return to nest at PAIS or RN, where eggs orhatchlings had been putatively imprinted. Hereinwe use the terms imprint, imprinting, and im-printed only for convenience. They are not meantto imply that the turtles actually imprinted toPAIS or RN, or that surviving females from thesetreatment groups were thereby predisposed toreturn to nest at the beaches where they wereputatively imprinted.

In addition, we acknowledge that conditionsto which the turtles were exposed during head-starting in captivity at the Galveston Laboratorymay have altered their behavior, performance,and survivability following release. We empha-size that head-start and reintroduction were notdesigned or conducted to test hypotheses aboutimprinting, navigation, or homing.

Head-start and reintroduction to PAIS havebeen referred to in the literature as experimen-tal, experiments, operations, projects, programs,and even ranching (Table 3). Kemp’s Ridleyhad previously nested at PAIS (Werler 1951;Hildebrand 1963; Carr 1967; NPS 1974 op. cit.;NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.; Wauer 1978, 2014).Most International Union for Conservation ofNature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission(SSC) guidelines for reintroductions (IUCN/SSC1998) were fulfilled during Kemp’s Ridley rein-troduction to PAIS. Nevertheless, characteriza-tion and adequacy of head-start and reintroduc-tion as experiments have been challenged (seeEVALUATIONS). We emphasize that head-startand reintroduction were not planned or executedas hypothesis-testing experiments (Klima andMcVey 1982; Woody 1986; Eckert et al. 1994;Pritchard and Owens 2005; Shaver and Caillouet2015), although necessary research and exper-imentation occurred in conjunction with both.Head-start and reintroduction were largely op-erational and highly manipulative (Meylan andEhrenfeld 2000), although scientific considera-tions influenced their planning and guided theirexecution, oversight, and evaluation.

Reintroduction and head-start are generallythought to have been planned as ancillary orsubsidiary parts of the KRREP, which was notthe case (Wauer 1978). In 1974, NPS developedthe first plan for reintroduction of Kemp’s Ridleyto PAIS (NPS 1974 op. cit.; Wauer 1978), andthe combination of reintroduction and head-startwas the primary focus of planning in 1977 and1978 (Campbell 1977 op. cit.; NPS et al. 1977op. cit., 1978 op. cit.). Lest this early focus bemisconstrued, recovery priorities later shiftedappropriately toward greater focus on protectingnesting beaches, nesters, eggs, and hatchlings inTamaulipas, developing turtle excluder devices(TEDs) for shrimp trawls, and promulgatingand enforcing regulations requiring TEDs inshrimp trawls (FWS and NMFS 1992; NMFS etal. 2011). Although the early planners includedhead-start as an essential part of reintroduction,

314

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

Table 3. Sources that referred to Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) head-start and reintroduction to PadreIsland National Seashore as experimental, experiments, operations, projects, programs, or ranching.

Pritchard (1976) Donnelly (1994)Wauer (1978, 2014) Ross (1999)Woody (1981, 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991) Meylan and Ehrenfeld (2000)Klima and McVey (1982) Márquez M., R. (2001)Magnuson et al. (1990) Márquez M. et al. (2005)U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National MarineFisheries Service (1992)

National Marine Fisheries Service et al. (2011)

they made no recommendations or commitmentsin the early plans to test head-start as a separateconservation method or management tool.

Controversy and conflict.—From their begin-ning in 1978, Kemp’s Ridley reintroduction andhead-start were controversial within the sea turtlescience and conservation communities, despitethe good intentions of the early planners, unani-mous agreement among them and their agencies,and advice, concurrence, encouragement, andoversight of well-known and respected sea turtleauthorities. Bowen and Karl (1999) described seaturtle conservation as war in the sense that deeptensions exist between science and advocacy, andsuggested that scientific findings are sometimesmisused to promote conservation goals. Tensionsdeepened when sea turtle science and advocacybegan to impinge on the shrimping industry. Iron-ically, over the years some proponents becameopponents and vice versa.

Head-start and reintroduction were drawn intothe conflict over incidental capture of sea turtlesin shrimp trawls (Magnuson et al. 1990) andNMFS regulations requiring TEDs in shrimptrawls (Condrey and Fuller 1992; Iversen et al.1993; Yaninek 1995; Epperly 2003). Magnusonet al. (1990) concluded: “Of all the knownfactors, by far the most important source ofdeaths was the incidental capture of turtles(especially loggerheads and Kemp’s ridleys)in shrimp trawling. This factor acts on the lifestages with the greatest reproductive value forthe recovery of sea turtle populations.” Life

stages with the greatest reproductive value arelarge subadults and adults (NMFS et al. 2011),but all post-pelagic Kemp’s Ridley life stages arevulnerable to incidental capture in shrimp trawls.U.S. government responses to the controversyand conflict influenced the direction and durationof various components of reintroduction andhead-start, thereby adding to the challengesof carrying out these experiments. Sea turtleconservation and research require patience,resilience, and persistence.

Components of head-start andreintroduction.—Table 4 lists some sourcesthat reviewed the components of head-start andreintroduction. Most of these components wereelucidated in the video (TPWD. 2010. Sav-ing the Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle. Available fromhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=afgsYchpD_Q[Accessed 6 December 2012]). Operationalcomponents of reintroduction combined withhead-start, based on about 2,000 or fewer eggstaken annually from RN during 1978–1988,included: (1) collecting, transporting, and incu-bating clutches of eggs; (2) attempting to imprinteggs and hatchlings; (3) transporting hatchlingsto the Galveston Laboratory; (4) head-startinghatchlings at the Galveston Laboratory tosizes thought capable of avoiding most naturalpredators at sea; (5) tagging head-started turtlesin multiple ways at the Galveston Laboratory;(6) transporting head-started yearlings (7–15 moof age) to release sites in the Gulf of Mexico oradjoining bays; (7) releasing head-started year-

315

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

Table 4. Sources that reviewed the components to Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) head-start andreintroduction.

Wauer (1978, 2014) Phillips (1989)Klima and McVey (1982) Marquez-M (1994)Caillouet (1984, 1987, 2000) Shaver and Caillouet (1998, 2015)Fontaine and Caillouet (1985) Shaver (2001, 2005, 2006, 2007)Fontaine et al. (1985 1988b, 1989a, 1989b) Higgins (2003)Márquez M., R. (2001) Fontaine and Shaver (2005)Caillouet et al. (1986b, 1988, 1993, 1995a, 1995b,1995c, 1997a)

lings; (8) collecting, examining, and interpretingtag returns for head-started turtles; (9) trackingsome of the head-started turtles via radio, sonic,and satellite transmitters and receivers; and (10)documenting nestings of head-started turtles inthe wild.

Table 5 lists sources covering precautions takento prevent the eggs for the reintroduction exper-iment from coming in contact with RN sand.Eggs were carefully placed in PAIS sand withinStyrofoamTM boxes and transported to PAISwhere they were incubated in the boxes. Hatch-lings that emerged were allowed to crawl downthe PAIS beach to the surf; after swimming ashort while they were scooped up in dip nets, putin cardboard or plastic boxes, and transportedto the Galveston Laboratory to be head-started.Putative imprinting at PAIS was terminated in1989 with release of the 1988 year-class of hatch-lings (Woody 1990, 1991), but components (8)and (10) of reintroduction continued and are on-going (Shaver and Caillouet 2015). Components(1) and (2) were conducted whenever Kemp’sRidley nestings were documented at PAIS andother Texas beaches, whether laid by head-started(including PAIS-imprinted and RN-imprinted tur-tles) or wild individuals (Shaver and Caillouet2015).

Head-start also included all components, but itwas conducted on 23 year-classes (1978–2000)by the Galveston Laboratory and its collaborators.For the 1989–1992 year-classes, about 2,000 orfewer hatchlings per year were transferred di-

Table 5. Sources covering precautions taken to pre-vent clutches of Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii)eggs, collected for the Padre Island National Seashorereintroduction experiment, from coming in contactwith Rancho Nuevo sand.

Fontaine et al. (1985 1988b, 1989a, 1989b)Fontaine and Shaver (2005)Higgins (2003)Klima and McVey (1982)Shaver (2001, 2005, 2006, 2007)Shaver and Caillouet (2015)Wauer (1978, 2014)Woody (1986)

rectly from RN (where they were putatively im-printed) to the Galveston Laboratory for head-start. In 1993, the annual number of hatchlingsreceived by the Galveston Laboratory from RNwas reduced to about 200 or fewer per year (Byles1993; Williams 1993; Caillouet 2005, 2006;Shaver and Wibbels 2007). Because head-startmethods were applied to year-classes 1993–2000,we consider these year-classes to have been head-started. However, they are referred to by NMFSas captive-reared for research purposes (Ben-jamin Higgins pers. comm.). Some individualsof the 2000 year-class were not released in 2001,but were kept in captivity for use in a PIT tag mi-gration experiment (Wyneken et al. 2010) then re-leased in 2003 (Benjamin Higgins, pers. comm.).In addition, 100 Kemp’s Ridley hatchlings col-lected from SPI in 2013 were captive-reared atthe Galveston Laboratory, then survivors were

316

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

used in TED tests and released offshore of SPIin 2014 (Benjamin Higgins, pers. comm.). Thesearch for Kemp’s Ridleys that were head-startedor captive-reared by the Galveston Laboratoryand released into the wild has continued (Shaverand Caillouet 2015), whether or not they wereassociated with the reintroduction experiment.

All KRREP activities proposed by NPS et al.(1978 op. cit.) were to be conducted for 11 y(1978–1988), including the work at RN, PAIS,and the Galveston Laboratory (Woody 1986,1990, 1991). However, the emphasis on reintro-duction was clear. Under heading “III. ProgramActivities” (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.), items Aand B were related to reintroduction; item C cov-ered beach monitoring to protect nesters and eggsat RN, as well as collection of 2,000 eggs forPAIS reintroduction and up to 2,000 hatchlingsfor head-start; item D covered research at RN;and items E–G covered care of hatchlings at RNand PAIS, other operations at PAIS, transportof hatchlings to the Galveston Laboratory, head-start, release, and monitoring.

With regard to accomplishments and evalua-tions of head-start and reintroduction, our reviewfocuses on activities carried out by the Galve-ston Laboratory and its collaborators. We also re-view captive breeding, because some head-startedKemp’s Ridleys from year-classes 1978, 1979,1982, and 1984 were distributed among marineaquaria for development of a captive brood stock(Table 6). Shaver and Caillouet (2015) coverKemp’s Ridley reintroduction, related conserva-tion and research on the turtles imprinted at PAISand RN, and the labor-intensive nester searchand detection program on-going at PAIS and else-where along the Texas coast.

Details of Early Planning

The first plan.—After we learned aboutRoland Wauer’s involvement in the earlyplanning, one of us (Caillouet) found out,serendipitously, that Wauer was scheduled topresent a seminar on birds at a plant nursery

Table 6. Sources covering distribution of head-startedKemp’s Ridleys (Lepidochelys kempii) from year-classes 1978, 1979, 1982, and 1984 among marineaquaria for development of a captive brood stock.

Balazs (1979)Brongersma et al. (1979)Caillouet (2000)Caillouet and Revera (1985)Caillouet et al. (1986b, 1986c, 1988)Márquez-M et al. (2005)Mrosovsky (1979)

(Martha’s Bloomers) in Navasota, Texas on 14August 2010. He contacted Wauer and attendedthe seminar to meet and interview Wauer, whograciously gave him a copy of Wauer (1999).Wauer (1999) described early planning of aproject “to provide increased protection tonesting Atlantic Ridley turtles, and to restorea nesting population to Padre Island, Texas”;the Galveston Laboratory’s participation in theproject was also described, but not referredto as head-start. However, Wauer (1978) hadalready referred to it as head-start. Wauer (pers.comm.) indicated that a Resources ManagementPlan for PAIS contained a project statementrelevant to reintroduction (Wauer 1978). Anotherof us (Shaver) located this plan (NPS 1974op. cit.) in the PAIS headquarters archives; itcontained Project No. 9 entitled Atlantic RidleyTurtle Reestablishment. She found out fromRobert Whistler (Donna Shaver, pers. comm.)that he drafted NPS (1974 op. cit.), as ChiefNaturalist for PAIS. Robert Whistler (pers.comm.) admitted that he knew little about seaturtles at the time, but learned from HenryHildebrand who influenced development ofProject No. 9, described as follows (verbatimfrom NPS 1974 op. cit.):

Project: Atlantic Ridley TurtleReestablishment

"Padre Island was once a major nestingsite of the Atlantic Ridley turtle. Accounts

317

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

from old-time residents relate how theytraveled by wagons along the beach andhad to wait while turtles traveled fromtheir nests to the water. This speciesis no longer known to nest within theUnited States. It does nest on the coastof Mexico where it is protected, buteggs are quickly collected and sold whenauthorities are absent. The species may beendangered and should be considered forreintroduction onto Padre Island whichmay be its only protected nesting site.

Action (Research): Initiate research,and proceed with actions deemed con-ducive to the reintroduction of the species.First, vehicles must be restricted froma section of beach; vehicles should notbe permitted to drive over the nests anddestroy the eggs. At the present time,there is no feasible section. However,the Master Plan proposes closing LittleShell Beach to vehicular traffic, andthis beach could be used as a nestingarea. Investigate the desirability of acooperative agreement with Mexico forthe collection and transportation of turtleeggs. Establish liaison with other agenciesand individuals who have shown interestin the population dynamics of the Ridleyturtle. Encourage the use of Padre Islandas a natural laboratory.

Research: This study could best beundertaken by a Park Service biologist;investigations should be initiated soon ifthis species is to be saved from extirpa-tion. Research activities should include:(1) comparative habitat evaluation, (2)feasibility of collection of turtle eggs fromMexican beaches and introduction on aprotected beach of Padre Island NationalSeashore, and (3) a monitoring program.”

Oddly, Robert Whistler was not mentioned inNPS (1974 op. cit.), but Roland Wauer (pers.comm.) confirmed that Robert Whistler draftedit. Project No. 9 appears to be the earliest writ-ten proposal for reintroduction of Kemp’s Ridleyto PAIS. It provided succinct rationale and ex-plicit aims for reintroduction of Kemp’s Ridleyto PAIS and called for research that could beconsidered pre-monitoring, elements that werelater thought to have been absent in the planning(Mrosovsky 2007). A chapter drafted by RobertWhistler (Whistler, R. 2005. Padre Island Admin-istrative History Chapter Eight: Natural ResourceIssues. Available from http://www.cr.nps.gov/

history/online_books/pais/adhi8.htm [Accessed6 December 2012]); Donna Shaver pers. comm.)explained that he and Henry Hildebrand “com-bined efforts to propose the turtle project in 1974”and sought support and possible funding fromNPS and other federal agencies, but support andfunding were not forthcoming. NPS (1974 op.cit.) scheduled the reintroduction project to be-gin in the fifth year of the plan; we assume thatwas to be 1979, but it was implemented one yearearlier (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.; Wauer 1978).

Wauer (1999) indicated that Clyde J. Jones (Di-rector, National Fish and Wildlife Laboratory,National Museum of Natural History, Washing-ton, D.C.) and he “. . . had developed the idea,initiated a feasibility study that was done by[Howard W.] Duke Campbell, and had invitedseveral sea turtle scientists to participate” as mem-bers of “the initial advisory group” that includedDrs. Archie Carr, Henry Hildebrand, and RenéMárquez. Roland Wauer (pers. comm.) clarifiedthat “the idea” was the decision made in Decem-ber 1976 to pursue further planning and imple-mentation of Project No. 9 (NPS 1974 op. cit.).Woody (1989) also confirmed that “. . . NPS pro-posed discussions of a project whose goal wouldbe to establish a nesting population of [Kemp’sRidley] sea turtles at the Seashore” (i.e., at PAIS);he also confirmed that “The possibilities of such aproject were discussed in 1976 and 1977 betweenregional representatives of FWS and NPS. . . ”

318

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

NPS et al. (1977 op. cit.) listed members ofa Science Advisory Board (SAB), includingArchie Carr (University of Florida), HenryHildebrand (Texas A&I University), RenéMárquez-M. (University of Mexico), and PeterPritchard (Florida Audubon Society), who wouldserve as consultants. Roland Wauer and RobertWhistler participated in further planning during1977 and 1978, so it is surprising indeed thatneither NPS (1974 op. cit.) nor its Project No.9 were mentioned in any of the 1977–1978planning documents we examined. It is alsonoteworthy that NPS (1974 op. cit.) did notmention head-start or enhanced protection atRN, both of which were later recommended byCampbell (1977 op. cit.) of FWS.

Resumed planning.—Interestingly, Pritchard(1976) recommended head-starting as well asperfection and wide spread adoption of a trawlnet equipped with a wide-mesh guard that wouldkeep turtles out, to improve survival prospectsfor Kemp’s Ridley and to supplement ongoingMexican beach protection in Tamaulipas. Herecognized that captive-reared turtles mightbecome dependent on artificial feeding, losetheir proper fear of man, or fail to navigateproperly to their nesting beach once theyreached maturity; nevertheless, he consideredhead-start worth trying as an experiment. InMay 1977, Carr (1977) called for drastic ac-tion to prevent Kemp’s Ridley from disappearing:

“The species is clearly on the skids, andif present conditions continue it willshortly - in two years perhaps, or three,or five - be gone. The dramatic dropduring the 1950’s was caused by over-exploitation combined with very heavynatural predation pressures. The terminaldecline now in progress has been broughtabout by incidental trawler catch. Whenridleys were many and shrimping was lessintensive this factor was negligible. Todayit is wiping out the species.”

Table 7. Additional sources of information on earlyplanning of the Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii)Restoration and Enhancement Program.

Klima and McVey (1982)Woody (1986, 1989)Fletcher (1989)Dodd and Seigel (1991)Godfrey and Pedrono (2002)Caillouet, C.W., Jr. circa 1999. MarineTurtle Newsletter articles on status of theKemp’s Ridley population and actionstaken toward its recovery. Available fromhttp://www.seaturtle.org/mtn/special/kemps.shtml[Accessed 4 December 2014].

This desperate situation apparently promptedNPS, FWS, NMFS, TPWD and Mexico’s INPto begin planning the KRREP in 1977, and toimplement it in 1978 (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.;Wauer 1978). The KRREP’s stated goals wererestoration of Kemp’s Ridley through enhance-ment of nesting success and survival at RN, andreestablishment of a breeding population at PAIS.Head-start was considered essential to the secondgoal. Early planning for the KRREP was alsodiscussed by sources listed in Table 7.

Roland Wauer played the central role inguiding and facilitating the planning during1977 and early 1978. He compiled the draftaction plan (NPS et al. 1977 op. cit.) and thefinal Action Plan (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.) withinput provided by participating individuals andagencies (Wauer 1978). During the 1978 nestingseason, he traveled to RN (Pritchard and Gicca1978), assisted in collecting and packing eggs inPAIS sand for transfer to PAIS (Wauer 1978), andaccompanied the resulting hatchlings on theirflight from PAIS to Galveston (Roland Wauer,pers. comm.). We also learned that R. BruceBury accompanied Roland Wauer to RN in 1978to participate in oversight and implementationof efforts to ensure that the eggs to be moved toPAIS did not contact RN beach sand (R. BruceBury, pers. comm.). According to Pritchard

319

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

and Gicca (1978), scientific visitors that werepresent for various periods during the first seasonof work associated with the KRREP includedPatrick Burchfield (Brownsville coordinator forthe project), Bruce Bury, Howard Campbell,Thomas Fritts, Roland Wauer, and Jack Woody(Project Coordinator).

Feasibility study.—The feasibility study(Campbell 1977 op. cit.) provided rationale,explicit aims, and pre-monitoring for reintro-duction (see Mrosovsky 2007). It encompassedbiological justification as well as mechanicaland political possibility for reintroduction.This study progressed in simultaneous phasesincluding: (1) documentation of Kemp’s Ridleyas a native breeding species on the PAIS; (2)review of mechanical and biological problemsassociated with moving sea turtle eggs from thenatal beach to establish new or reintroducedcolonies; and (3) contacts with all agencies andindividuals required for an operation of suchcomplexity, to determine their willingness andpotential to contribute to the effort.

The study began in May 1977 with a literaturereview and contacts with authorities expectedto possess unpublished data, including ArchieCarr, Henry Hildebrand, Frank Lund (Universityof Florida, Gainesville, Florida), Réne Márquez-M., and Peter Pritchard; all of them contributedcollectively and significantly to this data gather-ing effort. Early participation by such highly re-spected sea turtle scientists who were particularlyknowledgeable of Kemp’s Ridley is noteworthy.Ila Loetscher (Sizemore 2002) and Earl Lippoldtalso provided valuable unpublished data. In July-August 1977, physical suitability of the PAISbeach was examined by land and from the air andcompared to that at RN. Contacts also were madewith representatives of TPWD, NMFS, FWS (Of-fice of Endangered Species), and various aca-demic and conservation organizations to discusstheir interest in and potential contributions to theprogram, and the challenges of the program.

Campbell (1977 op. cit.) contained results andrecommendations for consideration in furtherplanning and commitment of resources. His wasthe first planning document to mention head-start,among those we examined. Campbell (1977 op.cit. Appendix II) recommended that head-start becombined with transplanting eggs and hatchlingsto reintroduce Kemp’s Ridley to PAIS. Clearly,tagging of head-started turtles was needed to pro-vide the essential means of linking them to head-start and reintroduction after their release. Oth-erwise, it would have been necessary to tag andrelease hatchlings to make it possible to evalu-ate reintroduction and head-start. At that time,the technology for mass-tagging Kemp’s Rid-ley hatchlings had not been developed (Pritchard1979; Allen 1981; Fontaine et al. 1993; Higginset al. 1997).

The literature review and correspondence con-ducted by Campbell (1977 op. cit.) produced noevidence of large-scale breeding aggregations ofKemp’s Ridley at PAIS, but indicated that individ-ual nestings had occurred with some regularityat PAIS over the preceding decade, not only byKemp’s Ridley but also by other sea turtle species.Hatching success of Kemp’s Ridley and otherspecies showed that eggs were fertile and phys-ical characteristics of the beach were suitablefor incubation. No obvious physical problemswere discovered regarding the PAIS beach, andstrong similarities were revealed between nestingbeaches at PAIS and RN. Beach slope and profile,sand grain size, and other physical characteristicswere essentially the same. Differences in air andwater temperatures at the two nesting sites wereminimal during the nesting season and thereforeconsidered unimportant. Mechanical and biolog-ical problems associated with transplanting seaturtle eggs were considered resolved over manypreceding years, and the process of transplant-ing eggs was considered routine for experiencedpersonnel. Moving and incubating eggs, hatch-ing them, and rearing young sea turtles had beenaccomplished throughout the world and were con-tinuing. The only area of uncertainty identified

320

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

by the feasibility study was that of “actually es-tablishing new colonies on new beaches.” Noclearly successful transplant had previously beenachieved. Apparent failure of previous transplantattempts was attributed to poor understandingof imprinting of hatchlings to their natal beach,enormous first-year mortality of hatchlings, andlack of a suitable method for tagging hatchlingsso they could be recognized later when they wereadults. There also was concern that the popu-lation could not support any removal of eggsfrom RN for reintroduction to PAIS. Recogniz-ing that this was subjective and difficult to assess,Campbell (1977 op. cit.) recommended an ini-tial approach designed to be compensatory andminimize this potential problem. For reintroduc-tion, 2,000 eggs would be transferred from RN toPAIS and the resulting hatchlings transferred tothe Galveston Laboratory for head-start; in addi-tion, 2,000 hatchlings would be transferred fromRN to the Galveston Laboratory for head-start.Campbell (1977 op. cit.) expected that “captiverearing of as many hatchlings from the Mexicanbeach as are removed to Texas should return moreadults to Mexico than would the natural recruit-ment from the eggs removed to Texas if the “headstarting” concept has any validity at all.” How-ever, 2,000 eggs were not equivalent to 2,000hatchlings (i.e., hatch rate was less than 100%).In any case, Campbell (1977 op. cit.) apparentlyexpected hatch rate as well as survival rate dur-ing head-starting to be higher than had these eggsor hatchlings been left at RN. In retrospect, aslong as enough head-started turtles survived andreturned to reintroduce nesting to PAIS, it didnot matter whether or not head-starting increasedsurvival from hatchling to nester life stages tothe extent expected by Campbell (1977 op. cit.).It is also possible that Campbell (1977 op. cit.)included such ambitious expectations to elicitagreement from all parties. A related questionis whether Campbell (1977 op. cit.) expectedhigher survival rates in head-started Kemp’s Ri-dleys after their release than those of wild coun-terparts of the same sizes and ages, but there

is no way to answer this question. Regardless,head-starting was essential to grow the turtles tosizes at which they could be safely tagged, sothey could be linked (by their tags, after releaseinto the Gulf) to experimental reintroduction andhead-start upon recapture or nesting. Interest inand concern for Kemp’s Ridley was high amongall individuals and agencies contacted by Camp-bell (1977 op. cit.), and support among the agen-cies for the proposed reintroduction was unani-mous.

Campbell (1977 op. cit. Appendix II) listedfive options (paraphrased, but in their originalorder) for recovery of the Kemp’s Ridley popula-tion: (1) protection of the known nesting beach,(2) reduction in incidental kill by fisheries opera-tions, (3) establishment of breeding populationsin protected areas in Texas, (4) enhancement ofrecruitment into the Mexican population, and (5)establishment of a captive breeding population.Options (3) and (4) constituted the core of thereport’s recommendations. Interestingly, option(5) was considered highly desirable and perhapscritical for egg production if the natural breedingstock were lost before full recovery. Option (1)was recognized as ongoing and critical to long-term survival of Kemp’s Ridley, but in need ofemphasis. Option (2) was in progress and con-sidered necessary for survival of most sea turtlespecies, but unlikely to be realized within theexpected 2–10 y remaining for Kemp’s Ridley.Campbell (1977 op. cit.) noted that PAIS repre-sented a potentially secure breeding ground forKemp’s Ridley where disturbance to breedingand nesting could be controlled with minimumenforcement effort.

Campbell (1977 op. cit.) listed the followingfactors as the minimum necessary for potentialsuccess of the proposed reintroduction, recog-nizing that some of them were too new to befully evaluated before they were attempted: (1)incubation of eggs in sand from PAIS to avoidpossible chemical imprinting to RN sand, andessentially natural orientation exposure of hatch-lings to the natal beach and offshore waters at

321

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

PAIS, (2) captive-rearing for 0.5–1 y to a sizeat which mortality due to predators is reduced,(3) adequate technique for marking young tur-tles to allow their recognition as adults, and (4)release of captive-reared turtles of a given year-class in an area and habitat consistent with theirage, place, and time of naturally occurring (i.e.,wild) young of the same year-class. All these fac-tors considered necessary for potential successwere operational, and much less stringent than themore elaborate evaluation criteria that were lateradded as reintroduction and head-start efforts pro-gressed (see EVALUATIONS). The above list offactors also suggests that establishing more strin-gent evaluation criteria to measure success beforereintroduction was attempted would have beenpremature, because the immediate and primarygoal was saving the declining Kemp’s Ridley pop-ulation from extinction (see Mrosovsky 2007).

Roland Wauer, Howard Campbell, and JohnC. Smith (Non-Game Project Leader, TPWD,Rockport, Texas) presented results and recom-mendations of the feasibility study to the JointSecretary’s and Southwest Regional AdvisoryBoards at Padre Island on 26 September 1977(Campbell 1977 op. cit. Appendix I). Weassume these “Advisory Boards” represented theSecretaries of the U.S. Department of the Interior(for NPS and FWS) and the U.S. Departmentof Commerce (for NMFS, within the NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration,NOAA), and the Southwest Regional Directorsof NPS and FWS; however, the NMFS SoutheastRegional Director was not mentioned. Afterthe 26 September 1977 presentation, TPWDexpressed interest in conducting negotiationswith government agencies in Mexico. AppendixI in Campbell (1977 op. cit.) was a veryimportant memorandum from Theodore R.Thompson (Deputy Regional Director, NPSSouthwest Regional Office) to the Directorof the NPS [whose name was not shown, butWilliam J. Whalen held the position], dated7 October 1977. Its subject was “Restorationof the Atlantic Ridley Turtle as a Cooperative

Interagency Project”; it summarized the meetingof 26 September 1977 and stated that: “The Stateof Texas already has talked with Mexico aboutobtaining turtle eggs. The Texas Department ofParks and Wildlife will host a meeting in lateNovember for agency personnel to develop aplan of attack and a timetable. I believe thatthis gathering should heavily involve Regionallevel personnel, who will follow through onactivities already started. It is particularlyimportant that the National Park Service, Fishand Wildlife Service, and the National MarineFisheries Service cooperate fully. Each agencymust play a significant role if the project is tobe successful.” This memorandum confirmedthat the State of Texas negotiated the transferof Kemp’s Ridley eggs from RN to PAIS forreintroduction, and it also mentioned the meetingthat TPWD would later host in Austin, Texason 17 November 1977, as scheduled in Camp-bell (1977 op. cit.) and NPS et al. (1977 op. cit.).

Draft action plan.—A draft “Restoration Planfor the Atlantic Ridley Turtle” was distributedby letter dated 28 November 1977 from RolandWauer to “all of the Austin participants” (Table8); the reference to “Austin participants” appar-ently referred to the 17 November 1977 meet-ing held in Austin, Texas (Campbell 1977 op.cit.; NPS et al. 1977 op. cit.). Roland Wauer didnot refer to this draft as an action plan, but hementioned head-start. Interestingly, the “Austinparticipants” represented NPS, FWS, NMFS,and TPWD, but not Mexico. Roland Wauer in-dicated that he had corresponded with “Archie,Peter, Henry and Rene” (i.e., Carr, Pritchard,Hildebrand, and Márquez-M., respectively) ask-ing them to serve on the “Science Board” (i.e.,the SAB), but did not mention whether theywere sent copies of the draft plan. We assumethey were sent copies, because Wauer’s letterrequested that recipients of the draft plan add de-tails on what was planned for the RN phase ofthe program so that he could prepare the finalplan, and he expressed hope that the plan would

322

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

Table 8. List of all Austin participants to whom Roland Wauer sent copes of the Draft Restoration Plan forthe Atlantic Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) via his letter 28 November 1977.

Bill Brownlee, Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPWD), Austin, Texas, U.S.A.Dr. Duke Campbell, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Gainesville, Florida, U.S.A.Ted Clark, TPWD, Austin, Texas, U.S.A.John Dennis, National Park Service (NPS) Washington Support Office (WASO-550), Washington, D.C.,U.S.A.Dr. Don Eckberg, National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S.A.Hal Irby, TPWD, Austin, Texas, U.S.A.Dr. Clyde Jones, FWS, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.Carol Justice, FWS. Washington, D.C., U.S.A.Dr. Ed Klima, NMFS, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A.Dr. James P. McVey, NMFS, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A.Floyd E. Potter, Jr., TPWD, Austin, Texas, U.S.A.John Turney, NPS PAIS, Corpus Christi, Texas, U.S.A.Robert G. Whistler, NPS PAIS, Corpus Christie, Texas, U.S.A.Jack Woody, FWS, Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S.A.

be finalized before mid-December 1977.NPS et al. (1977 op. cit.) probably was the

draft plan mentioned in Roland Wauer’s letterof 28 November 1977 because it did not includedetails of “research to be conducted at RanchoNuevo.” Item C on p.14 of NPS et al. (1977 op.cit.) suggested that adding such research detailswould be the responsibility of Howard Campbell.The primary focus of this draft action plan(NPS et al. 1977 op. cit.) was reintroduction ofKemp’s Ridley to PAIS. Although the sectionof NPS et al. (1977 op. cit.) entitled “RanchoNuevo Beach Monitoring and Egg Collection”included protection of nesting turtles and theireggs from native and human predators during thenesting season at RN, it also included collectionof eggs at RN for reintroduction to PAIS. NPSet al. (1977 op. cit.) named Jorge Carranza(Director of INP) as a member of the AgencyCoordinating Committee (ACC), along with Don[Donald] Ekberg (Director, NMFS SoutheastRegional Office, St. Petersburg, Florida), Hal[Harold] Irby (TPWD, Austin, Texas), Ro[Roland] Wauer, and Jack Woody. NPS et al.(1977 op. cit.) indicated that members of theSAB would serve as consultants throughout thecourse of the program, and that NPS would serve

as coordinating agency for the SAB. Permitrequirements were identified, including a permitfrom Mexico, a [U.S.] Endangered SpeciesPermit and a Texas permit. This draft planemphasized that “the key to the entire programis Mexico’s participation and support” and that“Don Ekberg and a Texas representative willmeet with Mexico’s Jorge Carranza regardingthe program on December 7–9, 1977.” It statedthat “Jack Woody will initiate a request forauthorization to handle and transport eggsand turtles immediately upon completion ofthis plan,” and that “Bill Brownlee [TPWD]will initiate a request for authorization of theState of Texas upon receipt of a copy of theEndangered Species Permit application.” Agencyresponsibilities were designated as follows: (1)beach monitoring and egg collections at RNwould be the responsibility of Mexico and theFWS, “with special assistance by National ParkService personnel,” (2) incubation of eggs atPAIS and exposure of hatchings to the beachand surf at PAIS would be the responsibilityof the PAIS Superintendent, and (3) rearingfrom hatchlings until the head-started turtleswere tagged and released, as well as monitoringthereafter, would be the responsibility of NMFS.

323

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

This early assignment of responsibility to NMFSfor monitoring the turtles following their releaseis important, especially in the context of itslater reiteration by NMFS’ National Sea TurtleCoordinator: “NMFS will place special emphasison detecting tagged turtles in the wild” (Williams1993). Beach monitoring at RN apparentlyreferred to protection of nesting turtles, eggs,and hatchlings from natural predators and humantake during the nesting season. However, itmay also have encompassed counting nests,eggs, and hatchlings. Special assistance by NPSpersonnel referred to the collection of 2,000eggs at RN, depositing them in PAIS sandwithin StyrofoamTM boxes, and transportingthem to PAIS. Another 2,000 eggs were to becollected and incubated at RN. Descriptionsof the “Rearing Project” and “Release andMonitoring” by the Galveston Laboratory wereincluded. However, other than indicating thatthe turtles would be tagged with numbered tagsand selected individuals would receive sonic tagsfor tracking, NPS et al. (1977 op. cit.) gave noadditional details regarding monitoring of theturtles after release. Also absent from NPS etal. (1977 op. cit.) were planned activities aimedat documenting head-started Kemp’s Ridleynestings at PAIS, RN, or elsewhere, althoughnestings were essential to accomplishing thestated goals of head-start and reintroduction(Shaver and Caillouet 2015). Documentingnestings of head-started Kemp’s Ridleys remainsessential to evaluating reintroduction andhead-start, together as well as separately.

Final action plan.—The finalized Action Plan(NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.) reiterated most of thedraft action plan (NPS et al. 1977 op. cit.). Withregard to the requirement that Jack Woody initiatea request for authorization to handle and transporteggs and turtles under an Endangered SpeciesPermit, a “Convention Permit” was added, appar-ently referring to the Convention on InternationalTrade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna andFlora (CITES). No mention was made of the need

for personnel at the Galveston Laboratory to bepermitted, but they certainly were required tocarry copies of all necessary permits while en-gaged in head-starting and related activities. Thesame was true of all who collaborated with theGalveston Laboratory; e.g., NPS personnel alsohad permits from Texas and FWS. In addition,when head-started Kemp’s Ridley releases tookplace off Florida, Florida Department of NaturalResources (FDNR) permits were required.

The following responsibilities and require-ments were specified (they are paraphrased here)for the Galveston Laboratory within NPS et al.(1978 op. cit.): (1) hatchlings received fromPAIS and RN will be placed in flow-throughsystems in tanks and raceways, (2) each groupof hatchlings (PAIS and RN) will be maintainedseparately, (3) turtles will be fed a diet ofchopped, boneless, scaleless fish, shrimp, andother marine foods available, at rates of 5–8%of body weight per day or at whatever volumeof food they will consume in 3–4 h, (4) afterNovember 15, turtles will be placed in specialheated containers (with water temperatureapproximately 22◦ C) equipped with the bestdesigns of water treatment facilities to handlewastes produced by the turtles, (5) water willbe exchanged whenever it is determined tobe below quality for the turtles, (6) turtleswill be maintained for periods up to one yearthen released, (7) turtles imprinted at RN andthose imprinted at PAIS will be released atperiods up to one year, at locations and timesdetermined to be the most logical for youngturtles to occur, (8) turtles will be placed inStyrofoamTM transport boxes, kept moist, cool,and ventilated, and moved by boat to releaselocations, (9) turtles will be released on grassflats off Florida’s west coast and lower Gulf ofMexico, and other areas where yearlings havebeen observed, (10) all turtles will be taggedwith numbered tags and selected individuals willalso be tagged with sonic tags and tracked, and(11) in the second year (i.e., 1979), some 1 yold turtles will be tagged with radio transmitters

324

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

and tracked from aircraft and satellites. TheAction Plan (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.) gave nofurther details regarding monitoring head-startedturtles after release, or searching for and docu-menting their nestings at PAIS, RN, or elsewhere.

The captive breeding option.—Establishmentof a captive breeding colony was amongoptions considered by Campbell (1977 op.cit. Appendix II), but it was not among theactions recommended by NPS et al. (1978op. cit.). However, after NPS et al. (1978op. cit.) was implemented, Brongersma et al.(1979) recommended establishment of a captivebreeding colony of Kemp’s Ridleys at CaymanTurtle Farm Ltd. (CAY), Cayman Island, BritishWest Indies, “to ensure preservation of thisgenetic entity, if efforts to preserve the speciesin the wild should fail.” They recommendedusing existing aquarium specimens, accidentallycaught individuals, and hatchlings of the 1978year-class at the Galveston Laboratory. Balazs(1979) recommended further that the reservoirof breeding Kemp’s Ridleys be establishedthrough dissemination of hatchlings of the 1978year-class to responsible and consenting aquaria,oceanaria, and appropriate zoological facilities inthe U.S., Mexico, and other countries (Table 6).

The mysterious meeting.—Also mentionedin the literature (e.g., Klima and McVey 1982;Woody 1989), and by some of the early plannerswho were contacted in 2010 (by Caillouet), wasa multi-agency planning meeting purportedlyheld in January 1977 in Austin, Texas. Wewere unable to corroborate that such a meetingtook place at that time, based on the planningdocuments we examined. Perhaps the meetingin question was the one hosted by TPWD on 17November 1977 (Campbell 1977 op. cit.; NPS etal. 1977 op. cit.), or the one held in January 1978during which the Action Plan (NPS et al. 1978op. cit.) was approved by attendees. We areunaware of any additional planning documentsthat might corroborate a January 1977 meeting.

If it did take place, it may have been informal(Jack Woody, pers. comm.), and therefore notdocumented in a planning document or report.

Oversight.—We stress that agencies andindividuals that participated in various com-ponents of reintroduction and head-start didnot proceed without direction, approval, andoversight of their work. Each agency had internalprocedures to approve, control, and evaluateits work. NPS et al. (1978 op. cit.) requiredannual reviews to evaluate past, current, andfuture phases of the KRREP. Initially, the ACCand SAB provided oversight and guidance to allagencies participating in the KRREP. Additionaloversight and guidance were provided by aSea Turtle Working Group established in 1977within the MEXUS-Gulf Program, a formalfisheries agreement between INP and the NMFSSoutheast Fisheries Science Center in Miami,Florida (Berry 1987). References to a Kemp’sRidley Working Group (KRWG) can also befound in the literature (e.g., NMFS et al. 2011;Burchfield and Peña 2013). In any case, afterthe KRREP was initiated, a consortium ofrepresentatives of NPS, FWS, NMFS, TPWD,and INP (or its successor agencies) met annuallyto review progress and discuss and approve plansfor the next year’s work. At these meetings,oral presentations and recommendations weremade, proposals were distributed, results wereevaluated, and proposed work was discussed,modified as needed, and approved. Scientistsfrom non-government organizations (NGOs) anduniversities occasionally participated in thesemeetings. If agreement on a proposal was notunanimous, that did not necessarily prevent itsimplementation. However, participants wereusually in agreement and worked cooperativelyin making decisions and providing guidance.In some cases, annual reports were preparedand distributed (e.g., Pritchard and Gicca 1978;Pritchard 1980; Caillouet 1997; Shaver 2012;Burchfield and Peña 2013). All participatingagencies involved in the KRREP had permitting

325

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

Table 9. Previous reviews of major accomplishments of Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) head-start,reintroduction, and research activities, and reviews of Kemp’s Ridley head-start at the Galveston Laboratory.

Reviews of Major Accomplishments Reviews of Head-startCaillouet et al. (1995c) Wauer (1978, 2014)Caillouet (2000) Woody (1981, 1986)Shaver (2001, 2005, 2006, 2007) Caillouet (1984, 1987)Higgins (2003) Caillouet and Koi (1985)Fontaine and Shaver (2005) Fontaine and Caillouet (1985)Shaver and Wibbels (2007) Fontaine et al. (1985, 1988b, 1989a, 1989b,

1990a)Caillouet et al. (1986b, 1986c, 1988, 1993,1995c, 1997a)Manzella et al. (1988b)Duronslet et al. (1989)Leong et al. (1989)Shaver (2001, 2005, 2006, 2007)Shaver and Caillouet (2015)

authority over some aspect of the work. Ifsomething objectionable to a given agencywas proposed, and that agency had authorityto withhold a necessary permit, it could haveprevented implementation simply by refusingto issue the permit. A good example is FWS’prevention of annual importation of 2,000Kemp’s Ridley hatchlings into the U.S. forhead-start at the Galveston Laboratory in 1993,simply by not issuing the necessary FWS permit(Byles 1993; Williams 1993). Therefore, variouscontrols were in place to reconsider and modifygoals, objectives, and direction of the KRREP atany time.

Public awareness.—High public profiles ofreintroduction and head-start greatly enhancedawareness of the plight of Kemp’s Ridley as wellas the need for conservation of all sea turtles.Especially effective in this regard were Kemp’sRidley conservation advocacy efforts of Carole H.Allen (Allen 2013), Chairperson of the organiza-tion she founded and managed (Help EndangeredAnimals-Ridley Turtles; i.e., HEART), a stand-ing committee of the non-profit Piney WoodsWildlife Society of Houston, Texas. Carole Allenand HEART not only had strong educational fo-

cus involving children and parents, but also ad-vocated use of TEDs, raised funds, and providedfunding and other support for Kemp’s Ridleyconservation, as well as head-start and relatedresearch at the Galveston Laboratory, PAIS, RN,and Texas A & M University in College Stationand Galveston. Availability of sea turtles in cap-tivity at the Galveston Laboratory provided op-portunities for public viewing during scheduledtours and NOAA open houses in which Allenand others representing HEART sometimes par-ticipated (off site). Also effective was public ex-posure to releases of hatchlings produced fromclutches laid by head-started and wild Kemp’sRidleys at PAIS (Shaver and Caillouet 2015).

Accomplishments

The challenges of rearing marine turtles in cap-tivity are so great that Tonge (2010) consideredthem unsuitable even for laboratory usage andgave them little attention in his discussion ofmaintenance and husbandry of aquatic reptiles.Mass rearing Kemp’s Ridleys for 7–15 moin captivity was much more challenging andexpensive than rearing laboratory specimensor rehabilitating live-stranded individuals that

326

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

are injured or ill. Sources summarizing majoraccomplishments and contributions of theNMFS Galveston Laboratory, NPS Padre IslandNational Seashore, and their collaborators tohead-start, reintroduction, and related researchare listed in Table 9. Kemp’s Ridley head-start atthe Galveston Laboratory was also previouslyreviewed by sources that provided details about(1) housing, raceways, and rearing containers,(2) seawater source, storage, quality, heating,monitoring, and replacement, (3) hygiene, (4)yolk absorption in hatchlings, (5) measuringand weighing turtles, (6) natural foods andcommercial feeds and feeding, (7) survival,(8) growth, and (9) prophylaxis, diagnosis andtreatment of diseases, all of which improved overtime (Table 9).

Collaborative research.—Availability of largenumbers of Kemp’s Ridleys in captivity, aswell as fewer Loggerhead (Caretta caretta)and Olive Ridley (L. olivacea) turtles, affordedopportunities for collaborative research at theGalveston Laboratory (Caillouet et al. 1986b,1988, 1995c; Fontaine et al. 1990a; Caillouet1997, 2000). The Galveston Laboratory col-laborated with individuals in federal and stateagencies, universities, and NGOs, as well as withveterinarians including Drs. Joseph Flanagan(Houston Zoo, Houston, Texas), Richard Hen-derson (Galveston, Texas), and Elliott Jacobson(University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida).Collaboration provided part-time employment,research experience, and career development forgraduate students, especially those associatedwith the Texas Sea Grant College Program,Texas A & M University, the University ofTexas Medical Branch, and the Louisiana StateUniversity Sea Grant College Program. TheGalveston Laboratory also participated in the SeaTurtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN),providing additional part-time employment forgraduate students. Collaborative research topicsincluded hatchling yolk-absorption, naturalfoods and commercial feeds and feeding, wastes

from sea turtles and excess feed in seawater,diseases and treatments, necropsy, behavior,growth, survival, morphometrics, compositionof Rathke’s gland secretions, genetics, swim-ming performance, physiology (reproductive,metabolic, and respiratory), tags and tagging,radio-, sonic-, and satellite-tracking, geographicdistribution, strandings, rehabilitation, threatsat sea, captive breeding, TED testing andcertification, incubation temperature dependentsex-ratios, olfactory imprinting, and trace metals.Caillouet and Landry (1989) chaired the FirstInternational Symposium on Kemp’s Ridley SeaTurtle Biology, Conservation and Management,held in October1985 at Texas A & M Universityat Galveston. For copies of Galveston Laboratorypublications and reports related to head-start,reintroduction, and the KRREP, see Caillouet(1997) and (NOAA Fisheries, Galveston Labo-ratory, Galveston Publications. Available fromhttp://www.galvestonlab.sefsc.noaa.gov/publications/ [Accessed 7 December 2014]).

Initial work with Loggerhead.—Klima (1978)clearly intended that the Galveston Laboratorytest practicality of a rearing and release pro-gram as a viable conservation and managementtool, not only for Kemp’s Ridley but also forother sea turtle species including Loggerhead,Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), Hawksbill(Eretmochelys imbricata), and Green Turtle (seealso Bullis 1978). However, consultation withArchie Carr, Peter Pritchard, Henry Hildebrand,and Galveston Laboratory staff led to a decisionto conduct the initial head-start trial on Logger-head, a threatened species (Klima 1978; EdwardKlima, pers. comm.; Jack Woody, pers. comm.).Leong et al. (1980, 1989), Klima and McVey(1982), and Clary and Leong (1984) describedcaptive-rearing of Loggerheads at the GalvestonLaboratory during 1977. Loggerhead was clas-sified as a threatened species, and its captive-rearing allowed the staff to gain experience be-fore attempting to head-start Kemp’s Ridleys.

In September 1977, 1,060 Loggerhead hatch-

327

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

lings were received from FDNR, Jensen Beach,Florida. They were reared in communal groupswithin large tanks and fed mostly raw fishthat had been frozen. Initially, seawater wasrecycled, but recycling was replaced later on bycontinuous, gradual flow-through. Almost allthe hatchlings became ill at one time or another.Sick turtles were removed from communal tanks,isolated individually in 10-liter plastic bucketscontaining seawater replaced daily, and providedexperimental chemotherapy (Leong 1979; Leonget al. 1980, 1989; Clary and Leong 1984). Whentheir condition improved they were returned tocommunal tanks. Overall survival was only 9%after 10 mo of rearing.

Kemp’s Ridley eggs and hatchlings forhead-start.—In 1978, the number of live Kemp’sRidley hatchlings received by the GalvestonLaboratory included 1,226 from RN and 1,854from PAIS (an additional hatchling from PAISwas dead on arrival) (Caillouet et al. 1986b,1987; Manzella et al. 1988b; Duronslet et al.1989; Fontaine et al. 1989b, 1990a). Thereafter,fewer hatchlings were received annually (exceptfor 2,025 received in 1990) by the GalvestonLaboratory to be head-started (ibid.; Caillouet1995b; Shaver and Wibbels 2007; BenjaminHiggins, pers. comm.). Within the period1978–1992, the number of Kemp’s Ridleyeggs taken from RN for the reintroductionexperiment (22,507 eggs), plus the estimatednumber (13,518 eggs) that produced hatchlingsat RN for head-start, represented 2.8% (or22,507 + 13,518 = 36,025 eggs) of the totalproduction of 1,286,900 eggs at RN during sameperiod (Caillouet 1995b). The annual take ofeggs that produced hatchlings for head-startduring 1993–2000 was ≈ 1/10 the annual takeof eggs during 1978–1992. Hatchlings fromyear-classes 1978–1988 were received by theGalveston Laboratory from PAIS as part of thereintroduction experiment (Shaver and Caillouet2015), and others were received directly fromRN (year-classes 1978–1980, 1983, 1989–2000)

and CAY (year-classes 1987–1988) (Caillouet1995b; Caillouet et al. 1995b). Hatchlings fromRN were transported by U.S. Coast Guard(USCG) or TPWD aircraft to Galveston. Inretrospect, the takes of eggs and hatchlings fromRancho Nuevo for Kemp’s Ridley head-startduring 1978–1985 did not prevent the populationdecline from reversing in 1986, although it mayhave prevented an earlier reversal.

Rearing turtles in groups.—During July-August 1978, Kemp’s Ridley hatchlings receivedby the Galveston Laboratory were initiallyreared in communal groups in large fiberglassraceways with seawater replaced thrice weekly,and they were fed a commercial, pelletized feed(Clary and Leong 1984; Leong et al. 1989).Every turtle contracted one or more diseases orinfections, some similar to those exhibited earlierby Loggerhead as well as other maladies thathad not been observed in Loggerhead. Kemp’sRidley hatchlings were very aggressive andbit or scratched each other causing injuriesthat led to further complications (Leong 1979;Klima and McVey 1982; Clary and Leong 1984;Fontaine et al. 1985). Sick individuals wereisolated and treated successfully in bucketsby techniques developed for Loggerhead, butmaladies recurred when successfully treatedturtles were returned to communal rearing.Further details concerning diseases in Kemp’sRidleys reared at the Galveston Laboratory, aswell as prophylaxis and treatment, can be foundin sources listed in Table 10.

Rearing turtles separately.—The practice ofcommunal rearing of Kemp’s Ridleys wasstopped after six months and replaced by rear-ing individuals separately, one per container (ini-tially in the same kind of buckets used earlierfor isolation and treatment of sick turtles); multi-ple containers were suspended side by side, par-tially submerged, in seawater within the race-ways. Bottoms of the buckets were perforatedwith holes that allowed seawater exchange and

328

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

turtle excrement and debris from uneaten feedto escape. Various sizes of individual containers,all with perforated bottoms, were later used toaccommodate the increase in size of turtles (Ta-ble 11). Some containers were purchased; plasticflower pots used for hatchlings and plastic buck-ets used after the turtles grew too large for theflower plots. Larger containers were fabricatedfrom purchased materials, to accommodate fur-ther increase in size of the turtles. All containerswere made of resilient, corrosion-resistant (ex-cept for some metal fasteners), non-toxic materi-als. The containers had smooth inside surfaces toprotect the turtles from abrasion and to preventtheir biting off pieces, since they would ingestnon-feed items if available. The location of eachcontainer within the raceway was coded for pur-poses of record keeping. Suspension of contain-ers in groups within raceways facilitated thrice-weekly draining of seawater, removing sea turtlewastes and debris from uneaten feed, cleaningraceways, containers, and turtles, and refillingraceways with clean seawater. When a racewaywas drained, the turtles remained out of water onthe bottoms of their suspended containers untilthe raceway was cleaned and refilled.

Isolation rearing was confining, but providedadequate space for the turtles to swim around,submerge completely, and rest on the bottom oftheir individual containers. However, there wasearly concern that such confinement reduced the

Table 10. Sources covering diseases in Kemp’s Ri-dleys (Lepidochelys kempii) reared at the GalvestonLaboratory, as well as prophylaxis and treatment.

Leong (1979)McLellan and Leong (1981, 1982)Fontaine et al. (1983, 1985, 1990b)Clary and Leong (1984)Caillouet et al. (1986b)Leong et al. (1989)Robertson and Cannon (1997)Higgins (2003)Jacobson (2007)

turtles’ physical fitness. Physical fitness of head-started juveniles was tested in captivity, by ex-perimentally exposing a sample of turtles, oneat a time, to a controlled-current exercise reg-imen within a laminar flow tank (Stabenau etal. 1988, 1992). Each turtle in the sample wassubjected to this regimen 1 day each week overa six month period; the turtles swam againstthe current and their fitness showed signs of im-provement over time (Stabenau et al. 1988, 1992;Valverde et al. 2007). However, this exercise reg-imen could not be adopted as a routine practicefor all head-started turtles, because of limited per-sonnel, equipment, and funds, as well as the largenumber of turtles being reared.

Seawater temperatures were maintained withinan approximate range of 20–30C, mostly near26–30C, and rarely fell below 20C (Caillouet etal. 1986b; Fontaine et al. 1988b, 1989b; Cail-louet 2000; Higgins 2003). Forced-air heatersand heated seawater controlled air and seawa-ter temperatures during winter. Forced-air venti-lation controlled air and seawater temperaturesduring summer. Clean and warm seawater wereessential to successful rearing and disease pre-vention.

Malone and Guarisco (1988) analyzedseawater containing Kemp’s Ridleys, theirwastes and uneaten feed, and results were usedthereafter to guide seawater management duringhead-starting. They assessed seawater qualitybased on biochemical oxygen demand, totalKjeldahl nitrogen, ammonia nitrogen, nitritenitrogen, suspended solids, volatile suspendedsolids, and settleable solids. Wang (2005)

Table 11. Sources covering containers used to head-start Kemp’s Ridleys (Lepidochelys kempii) at theGalveston Laboratory.

Fontaine et al. (1985, 1988b, 1989b, 1990a)Caillouet et al. (1986c, 1988)Manzella et al. (1988b)Caillouet (2000)Higgins (2003)

329

Caillouet, Jr. et al.—2010 Head-starting Symposium: Head-starting and reintroduction of Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtle in Texas.

studied trace metal accumulation in Kemp’sRidleys during head-starting. Various indicatorsof seawater quality were routinely monitoredduring head-starting (Caillouet et al. 1986b;Fontaine et al. 1988b, 1989b; Duronslet et al.1989; Higgins 2003).

Artificialities of captive-rearing.—The turtleswere reared out of view of each other, but wereable to see their surroundings and caretakersabove their containers. Rearing exposed them toadditional artificialities of feeds, feeding, light,temperatures, sounds, and other physical andchemical characteristics of their captive environ-ment that may have predisposed them to maladap-tive post-release behaviors and survivability ascompared to their wild counterparts. Post-releasebehaviors considered abnormal or aberrant werereported for some head-started Kemp’s Ridleysobserved after release into the Gulf of Mexico(Fontaine et al. 1989a; Meylan and Ehrenfeld2000; Shaver 2007; Shaver and Wibbels 2007).Tag returns and short-term tracking by sonic, ra-dio, and satellite methodologies made it possibleto link post-release behaviors to head-start andreintroduction. However, the potential for suchdetrimental effects (Pritchard 1976; Woody 1990,1991) did not dissuade the early planners or theiragencies from approving and implementing head-start and reintroduction (NPS et al. 1978 op. cit.).

Conditions of captive care may also affect wildKemp’s Ridleys taken from their natural environ-ment for medical treatment and rehabilitationafter being found live-stranded, injured, or ill.Exposure of wild Kemp’s Ridleys to extendedhuman care and artificial conditions in captivityis not an issue when the turtles have permanentdisabilities, infirmities, or infectious diseasesthat prevent their return to the wild. However,when wild Kemp’s Ridleys are temporarilyheld in captivity for medical treatment andrehabilitation, human care may also predisposethem to maladaptive, abnormal, or aberrantbehaviors following their return to the wild.This potential apparently has not discouraged

medical treatment, rehabilitation, and releaseof such turtles (Caillouet 2012b; NOAA, U.S.Department of Commerce. 2010. NOAA’sOil Spill Response: Rehabilitated Kemp’sRidley Sea Turtles Released. Available fromhttp://www.noaa.gov/factsheets/new%20version/