Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research: a diary-based approach

-

Upload

felicity-thomas -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research: a diary-based approach

Area

(2007) 39.1, 74–82

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research: a diary-based approach

Felicity Thomas

Department of Geography, Queen Mary, University of London, London E1 4NS

Email: [email protected]

Revised manuscript received 20 November 2006

Little attention has been given to understanding the emotional well-being of peopleliving with HIV/AIDS in developing countries, despite the fact that emotions may impacton people’s sense of purpose and value, and ultimately their ability and resolve to holdlivelihood and familial responsibilities together. Drawing upon research undertaken inthe Caprivi Region of Namibia, this paper examines the use of solicited text and photodiaries in enabling insight into the emotional impacts of HIV/AIDS. The advantages andconstraints of diary methods are examined, focusing on informant-directed research andthe ethical considerations surrounding their use.

Key words:

Namibia, HIV/AIDS, emotions, well-being, solicited diaries, visual methods

Introduction

Undermining and even reversing the developmentefforts of recent decades, the HIV/AIDS pandemicconstitutes one of the most profound and complexchallenges facing poverty alleviation in ‘developing’countries. Although research on HIV/AIDS has beendominated by a focus upon the illness as solely aclinical condition requiring medical treatment, asteadily increasing literature exists to examine thesocial and economic impacts of HIV/AIDS. In parti-cular, focus has been placed upon rural livelihoods(Rugalema 1999; Mathambo Mtika 2003), micro-economic household impacts (Yamano and Jayne2004; Russell 2004), changing demographics anddependency (Foster

et al.

1997; Williams andTumwekwase 2001; Monasch and Boerma 2004),gender constraints (Gregson

et al.

2004; Seeley

etal.

2004) and macroeconomic impacts (Dixon

et al.

2001). However, much of this work has focused onthe objective and visible impacts of HIV/AIDS andwith few notable exceptions (cf. Baylies 2002; Boltonand Wilk 2004) little attention has been given tounderstanding how affected individuals and com-munities themselves perceive and subsequentlyexperience the epidemic. Research focusing on the

more subtle impacts of HIV/AIDS on emotionalwell-being has been limited to people who areaware of and able to openly discuss their HIVstatus. Much of this work has been conducted in‘developed’ countries, amongst users of HIV/AIDSsupport groups (Friedland

et al.

1996; Wilton 1999)and focus has been placed upon the process ofdiagnosis and the subsequent experience of ‘livingwith HIV/AIDS’.

While the emotional impacts of HIV/AIDS such asgrief, sorrow, anger and shame may impact onpeople’s sense of purpose and value, and ultimatelytheir ability and resolve to hold their livelihoods andfamilial responsibilities together (Seeley and Pringle2001), little attention has been given to understandingthe emotional well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS in developing countries. This is due partly tothe widespread existence of HIV/AIDS-related stigmawhich discourages HIV testing and fuels the denialor withdrawal and isolation of people living withHIV/AIDS. However, it is also reported to result froma general reluctance or perceived inability amongstthose working in ‘development’ to confront suchemotional issues (Seeley and Pringle 2001) as wellas a prevailing tendency for research in health geo-graphies to be confined to select areas of the

Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research

75

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

‘developed’ world (Kearns and Moon 2002). Drawingupon fieldwork undertaken in the Caprivi Region ofNamibia, this paper explores how the use of solicitedtext and visual diaries elicited detailed insight intothe personal experiences and emotions of a sampleof people living with long-term and stigmatizedillness. The ethical implications of the diary methodsare then examined.

Health and emotions

In his review of the medical geography literature,Kearns (1996) called for a change of direction whichrecognized not only the distribution and diffusion ofthe HIV virus, but also the emotional experiences andwell-being of people living with HIV/AIDS. In response,geographies of health and illness have been at theforefront in acknowledging that physical and emotionalexperiences are intrinsically linked (Kearns and Moon2002; Davidson and Milligan 2004; Basu 2006), andmust be seen within the context of the changingembodied relations, discourses and socio-culturalenvironments in which they are located (Bennett 2004;Thien 2005). Attempting to recast ‘subjects of researchas

persons

rather than as

patients

’ (Kearns 1995, 252),increasing focus has been placed on the emotionaland subjective perceptions of people themselves, withgrowing acknowledgement that well-being is largelydetermined by a person’s capability to ‘choose a lifeone has reason to value’ (Sen 1999, 74). Ill-healthand ill-being may therefore encompass not only thephysical impacts of the ‘disease’ or ‘affliction’, but arange of more emotional factors such as exclusion,insecurity, powerlessness, self-respect and personalbeliefs (Dean 2003).

More recently, an emerging interest in emotionalgeographies has brought increasing recognition thatsocial relations are lived and experienced throughemotions (Laurier and Parr 2000; Widdowfield 2000;Anderson and Smith 2001; Bennett 2004; Zautra

et al.

2004). Rather than being irrational, disruptiveand overly subjective, it is argued that emotions areintrinsically bound up with wider structures andprocesses (Bondi 2005; Thien 2005; Basu 2006) andthus affect the changing ways we perceive and reactto the people, places and environment around us(Milligan 2005; Kim-Prieto

et al.

2005). As Andersonand Smith state,

At particular times and in particular places, there aremoments where lives are so explicitly lived through pain,bereavement, elation, anger, love and so on that the powerof emotional relations cannot be ignored. (2001, 7)

Consideration of emotions is therefore central in anyattempt to understand how social relations mediatethe ways in which ‘lives are lived and societiesmade’ (2001, 7), and the dynamic sense of whomand what we are.

While much of the literature on emotional geo-graphies has focused upon the emotional processesinvolved in

doing

research (cf. Hubbard

et al.

2001;Widdowfield 2000; Meth with Malaza 2003),Bennett (2004) supports a body of literature in thewider social sciences (e.g. Katz 1999; Barbalet 2002)in stressing the importance of considering the emo-tions of the ‘researched’ in enabling contextualunderstanding of the ‘rules’ and structures that helpshape emotional behaviour and well-being. However,eliciting such emotive and often sensitive informa-tion raises a number of methodological and ethicalissues, particularly when research is carried out inother cultural contexts in which open displays ofemotion may be relatively restricted or differentlydefined.

Using solicited diaries in the Caprivi Region

This research was conducted in the Caprivi Region,located in the far north-east of Namibia. Subsistencecultivation and livestock husbandry play a centralrole in livelihoods, although most households areinvolved in an array of activities to meet food andcash requirements. The Caprivi’s status as one of theleast developed regions in Namibia (Mendelsohn

et al.

2002) is primarily caused by decreasing lifeexpectancy, caused (and exacerbated) by HIV pre-valence rates of 43 per cent amongst the adultpopulation (MOHSS 2004).

Using a range of qualitative methods, the widerresearch programme aimed to examine the impactsof HIV/AIDS on livelihoods, vulnerability and sup-port networks in three rural villages in the CapriviRegion. A livelihoods survey with 100 householdsand participatory methods were used to initiatediscussions of the perceived impacts of HIV/AIDS.Semi-structured repeat interviews with 18 case studyhouseholds enabled investigation into householdcomposition and transfers, coping strategies, beliefsystems and the perceived impacts of illness anddeath. In addition, 12 focus groups provided furtherinsight into customs and norms and local under-standings of HIV/AIDS. These methods provided in-depth understanding of the socio-cultural, economicand environmental context of the study sites, and the

76

Thomas

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

perceived impacts of HIV and AIDS on livelihoods,vulnerability and support networks. However, itbecame clear that households in which a personwas currently ill with AIDS-related symptoms wereunder-represented in the research and that opendiscussion of HIV/AIDS was only possible in a gen-eralized, non-personal context. The reluctance ofsuch households to participate was due largely totheir lack of available time between caring dutiesand livelihood activities. One way to ensure that theresearch gave voice to people experiencing illnesswas through the use of solicited text and photodiaries.

Although often overlooked as a research method,solicited diaries have proved important in researchon health and behaviour (Elliott 1997; Coxon 1999).However, as Crang (2003, 493) argues, qualitativemethods that are ‘often derided for being somehowsoft and “touchy-feely” have in fact been rather lim-ited in touching and feeling’ and the use of diarieshas tended to focus primarily on the recording ofdaily activities and bodily practices. With fewnotable exceptions (cf. Meth 2003), little attentionhas been given to eliciting the personal emotionswhich influence, and are influenced by, the experi-ences and actions of those recording the diaries. Inthis research, solicited text and photo diaries wereused to gain in-depth insight into the emotions ofpeople living with AIDS-related illness. Used inconjunction with the methods applied in the widerresearch study, this enabled deepened understand-ing of the context in which such emotions were felt,and the ways in which emotions were intimatelybound up with personal relations, identity andwell-being.

Before discussing the commissioning of the dia-ries, it is important to recognize the cultural contextin which the diaries were undertaken. Socio-culturalnorms and notions play a key role in influencingdisplays of emotion (Tan

et al.

2005) and in thisresearch there was a clear distinction betweenemotions displayed in public and private spaces.Public displays of emotion were restricted, withfunerals providing one of the few public arenas inwhich emotions such as grief and sorrow wereopenly displayed and, particularly amongst women,expected.

1

When asked about emotional supportnetworks however, people frequently commentedthat they did not tend to share their negative emo-tions with others. The main reasons given for thiswas that it would not be of any help to do so, thatburdening someone else with one’s emotions was

inappropriate and shameful, and that divulging one’sfeelings may result in hurtful gossip. While talkingabout illness in a general context was not tabooed,the stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS meant that openlydiscussing people’s personal experiences of illnessrisked upsetting, offending and stigmatizing the illperson. A major advantage of the solicited diaries wasthat they enabled people to express their thoughtsand emotions in writing, thus avoiding the potentialupset and harm that may have arisen through moreconventional interviewing methods.

To commission the diaries, it was necessary towork through Home Based Care (HBC) workers inthe study sites to identify households in which aperson was currently ill, and to approach potentialdiary keepers. In each case, the HBC worker wasalready well known to the household, and was alreadyvisiting them to provide assistance. It was madeclear that diary keeping was voluntary, but all ofthose approached agreed to participate. With oneexception, all of the ‘patients’ keeping diaries in thisresearch were women living in female-headedhouseholds. This is likely to have been influencedby the fact that households were identified throughHBC workers. The gendered nature of caring in theCaprivi means that it is common for women to returnto their own relatives for care, often their motherswho, if widowed, were likely to be disadvantagedin labour and resource assets, and therefore morereliant upon assistance provided by HBC workers.

Diaries were kept by seven people living withAIDS-related illness and by their main carer, forperiods of one to six months. HBC workers maderegular visits (usually several times a week) tohouseholds to provide assistance and to monitor thediary process. Coding and analysis of the diarieswas undertaken whilst in the field, enabling rigorouscross checking of information and identification ofthemes common across the diary keepers. Diarieswere recorded in the preferred language of eachrecorder, and those not written in English weretranslated by my interpreter.

2

Although some con-sider the process of paying research informants as areassertion of power relations (cf. Ansell 2001), Iagree with McDowell (2001), who argues that it isappropriate to provide an incentive, or in some wayrecompense those involved in research, and believethat not doing so can also be exploitative and rein-force power relations over the ‘researched’. Afterdiscussions with my translator and HBC workers, itwas decided that the most appropriate payment wouldbe in the form of a small but significant sum of

Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research

77

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

money. Thus, those keeping diaries and the HBCworkers ‘supervising’ the process were each paidNS$100 (approximately £10) once the diaries hadbeen collected.

Although cultural norms and lack of resourcesmeant that self-expression through diary keepingwas not common in the Caprivi Region, popularmedia (in particular radio and newspapers) meantthat all informants had heard of, and understood therationale of diary keeping. However, rather thanbeing private documents, diaries solicited specifi-cally for research purposes ‘are written with aparticular reader and their agenda in mind’ (Elliot,1997, 9), a factor which may potentially bias theinformation recorded. Diary keepers were given abrief ‘guide’ regarding the type of information I wasparticularly interested in, namely their experiences,both positive and negative, of living with illness.However, it was made clear that they were free towrite what they wished, and that the NS$100 pay-ment was not dependent on the type of informationrecorded.

In combination with the written diaries, theresearch also drew upon autophotography to gain adeeper understanding of the emotions and experi-ences of people living with long-term illness. Whileinterviewing methods can create and reinforce thedominant frames within which knowledge is real-ized, autophotography draws upon people’s visualimaginations (Latham 2003), enabling it to be aninclusive and empowering research method whichdocuments knowledge from the perceptual orienta-tion of the informant (Markwell 2000; Harper 2002;Dodman 2003). While autophotography does notusually provide a daily reflexive account in the sameway as written diaries, it is argued that photographsare ‘deeply embedded and contextualised by thepersonal lives of the producers’ (Rohde 2001, 189),and enable access to places usually inaccessibleto a researcher (Young and Barrett 2001). In thisresearch, each diary keeper was given a disposalcamera to record people, objects or places that hadbeen important or influential in their lives sincebecoming ill, in both a positive and negative sense.To avoid misrepresentation and decontextualizationof the pictures, each person was asked to record thecontext in which each photograph was taken. Whilesome people used up their film within a few days,others took their pictures over a period of severalweeks, taking time to think about and decide uponwhich experiences they wanted to represent visually.Respondents took photographs which reflected their

current emotions and experiences, as well as picturesof people or objects that had had a significant orlong lasting impact upon their lives, thus addingfurther depth to the information recorded in thediaries. As has been recorded elsewhere (Young andBarrett 2001; Latham 2003), autophotography usedin combination with other methods also enablestriangulation of data, in this case with the informa-tion recorded in the diaries and the wider researchproject.

Recording emotions

Kearns and Moon (2002) stress the need to movebeyond snapshot studies to consider the dynamicnature of the health and illness process. The time-consuming nature of the case study interviews inthe wider research meant that interviews wereconducted with HIV/AIDS afflicted households inwhich the ill person had already died. The informa-tion recorded was often based upon events fromseveral years past, which although useful in provid-ing a more reflective interpretation of the impact ofHIV/AIDS, presented a relatively static interpretationof the illness and caring process, and reflected theemotions of the interviewee only on the day inwhich the interview took place. In contrast, whilesome diary keepers provided a retrospective accountof some of their most memorable experiences, otherswrote on most days, enabling the illness ‘process’and the fluctuating emotions of the diarist to befollowed over time as they were experienced.

Fear and confusion

The intense stigma associated with HIV/AIDS meantthat it was unclear how many of the diary keeperswere aware of their HIV status. Given the low levelof HIV testing within the region, it is likely that fewpeople actually knew their HIV status, and thatthose who did felt unable to disclose this to otherhousehold members. Studies in developed countrieshave found that awareness of HIV status hasenabled people to come to terms with their positivediagnosis, ensure they are knowledgeable about thepotential implications of the illness and activelyplan their lives around this (Finerman and Bennett1995; Wilton 1999; Ezzy 2000). However, this wasclearly not the case amongst those keeping diariesin the Caprivi, and it was evident that fear andconfusion over the long term and variable nature ofthe illness dominated the emotions of ill people. Atseveral points in her diary, for example, Gertrude

78

Thomas

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

recorded her worries and confusion over theincreasing severity of her illness.

I can see that these sores will cause my death becausethey don’t get any better. When they finish they juststart to grow again. Many people are laughing at methat its HIV/AIDS otherwise I’d have been cured. I’venever seen these sores before in my life – maybesomeone has witched my body and that’s why theydon’t go away. (Gertrude, diary extract, undated)

Although it was possible to obtain basic medicineslocally, it was necessary to travel further afield andto pay fees to secure prescribed medication. Illpeople were therefore dependent upon the help ofothers to gain access to treatment, which, as Clairestates, led to considerable anxiety when help wasnot forthcoming.

My tablets have finished and I don’t know where I canget money to buy more so I think this will be the endof my life . . . I asked my father but he said I had towait. I am so confused I could easily kill myself.(Claire, diary extract, 22 April 2004)

While the changing relationship between the carerand the ill person has been addressed elsewhere(Thomas 2006), it is important to note that theresource constraints facing the household, as well asthe burden and fatigue of long-term care, meantthat the level of support provided to the ill personvaried, leaving them emotionally distressed whencare was less forthcoming than they wished. Severalpeople recorded instances when they had been leftalone in the household, sometimes without accessto basic resources such as water. Photographs takenby diary keepers recorded the important role playedby children in providing a non-judgemental andsupportive role during times when other house-hold members were absent or appeared unwilling tohelp.

Frustration and loss of purpose

It is recognized that solicited diaries can provideinsight into the taken for granted assumptions thatshape everyday actions and meanings (McGregor2006). While the ability to be independent and ‘seefor yourself’, i.e. be self-sufficient, had emergedduring the wider research study, the relevance ofthese issues in influencing identity and self respectwas brought to the fore within the diaries. The natureof AIDS-related illness meant that over time, thecaring and illness process extended over significantperiods, often several years, during which the carer

and the ill person were unable to maintain fullinvolvement in livelihood activities. All the ill peoplekeeping diaries expressed feelings of guilt andremorse over their inability to fulfil livelihoodresponsibilities and the knowledge that the cost ofresources diverted to caring and treatment wasthreatening household livelihood security. Deeplyaware of the resource costs of their illness, several,such as Patricia, expressed their desires to repaytheir relatives once they had recovered for the coststhey had incurred.

My parents lost a cow and $1000 for the traditionalhealers, hospital, transport and food. My worry is howI will get a job so that I can pay back what they havelost. (Patricia, diary extract, 1 May 2004)

In cases, the pressure to avoid becoming a burdento others led to ill people denying their needs anddepriving themselves of treatment. As Henry explains,his mother refused to go to hospital for treatment,fearing that the household would be encumberedwith the cost of a coffin should she die there.

My mother said that it’s better for her to die in thevillage rather than at the hospital because no-one willbe able to give us money to buy a coffin. I had to trickher to go to the hospital – when she realised she wasthere she was so angry with me. (Henry, diary extract,undated)

The loss of purpose felt by those unable to carry outlivelihood duties was exacerbated by the difficultiesthey faced in fulfilling familial responsibilities. Duringperiods of illness, diary keepers expressed concernsregarding the care that their children were receiving,and their inability to provide adequately for themwhilst they were ill. Patricia and Gertrude’s diariesshowed clearly their concern over the current andfuture security and well-being of their children.

My thoughts today are that when I’m sick my childrenworry me because care is lacking and they are noteating and wearing [clothes] the way I want them tobe as a mother . . . they feel lonely because they missme as I’m the only one they trust in their lives. I didn’tsee any help because my carer is still not around.(Patricia, diary extract, 9 March 2004)

Now I think when I will die where will my childrenremain and what are they going to eat and who willpay for them in school, so they will drop out fromschool when I will die. This is the most serious thingI think about when I’m very sick. (Gertrude, diaryextract, undated)

Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research

79

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

Optimism and sense of purpose

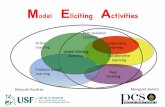

While many of the emotions expressed through thediaries were understandably negative, the illnessexperience was a dynamic process, with significantperiods of enhanced well-being recorded duringperiods of illness remission. While this was due inpart to people’s optimism that they were recoveringfrom the illness, their ability to be independent andfulfil familial and livelihood roles was of paramountimportance in enhancing their sense of value andpurpose. Miriam, for example, recorded her happi-ness at being able to continue her livelihoodactivities, while the photographs illustrated inPlate 1 demonstrate the importance attached to‘seeing for yourself’ and achieving at least a level ofindependence.

I was so excited when I woke up – I washed mysandals on my own and no-one helped me. I asked mybrother to take a picture while I was doing this as I wasso happy not to feel any pain. (Miriam, diary extract,10 May 2004)

Ethics and emotions

The use of solicited diaries for undertaking emotionalresearch clearly raises a number of ethical issues.Of paramount significance is that the very processof diary keeping undoubtedly played a role in creat-ing some of the emotions recorded. Whilst conduct-ing research that is potentially upsetting disruptsthe over-riding and usually unquestioned ethicalobjective of ‘avoiding harm’, it also raises importantquestions regarding how harm is defined and bywho, what level of harm is deemed (un)acceptableand how the costs to individuals are weighed upagainst the collective needs or potential benefits ofraising awareness of the particular group in question(Robson 2001; Meth with Malaza 2003). This alsolinks into debates concerning confidentiality andexploitation, and these issues will be examined now.

Plate 1 Photographs taken by people living with long-term illness to demonstrate the importance of

‘seeing for yourself’. (a) ‘Some of my goods like sugar, flour, maize-meal, cooking oil. It helps me because it’s

where I get money for the clinic and for food when I make cakes to sell’ (Carina). (b) ‘These tablets are

what I take for TB. They help me to be able to wash my clothes and cook for myself’ (Miriam). (c) ‘This is me pounding sorghum. I have to do this because I cannot afford to buy a bag of maize. But this pounding makes

my chest hurt because I have TB’ (Caroline)

80

Thomas

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

Whilst the diaries were translated in the field,the delay between the writing and translation of theinformation meant that it was not possible to followup issues raised at the exact time that the diaries andassociated emotions were recorded. Any emotionalissues discussed when clarifying diary entries weretherefore retrospective to the emotions actuallyexperienced. While my translator and I were able tolisten sympathetically on occasions when peopledid choose to discuss their feelings and experiences,and inform people about the new anti-retroviraltreatment scheme starting in the region, not being atrained counsellor meant that it was not appropriateto try and offer direct counselling support to diarykeepers. On reflection, it is possible that more sup-port and counselling could have been sought fromprofessionally trained personnel, although this in turnwould have raised issues regarding confidentialityand anonymity, and, given the limited public displaysof emotion in the Caprivi, would possibly have beenconsidered culturally inappropriate.

As Cloke

et al.

(2000) state, the process of researchimpacts not just upon the ‘researched’, but alsoindirectly, upon those who belong to their socialworlds. Because diaries were recorded in the privatesphere of the household, it is not possible to knowhow their recording impacted upon intra-householdrelations. Tensions between ‘patient’ and carer wererecorded in several diaries (cf. Thomas 2006), and itis possible that these issues were exacerbated by thediary-keeping process, although this was never statedto be the case. Separate books and pens were pro-vided for each diarist, thus limiting the opportunityfor potentially upsetting statements to be seen byeach person. Given the nature of the householdcompounds, it would, however, have been difficultfor diary keepers to keep books hidden. One solutionto this would have been to store diaries with a neutralparty such as a HBC worker, although this again wouldhave raised issues of confidentiality and safe storage,as well as prevented the diary keeper from recordingtheir experiences and emotions as they happened.

It is also not possible to rule out the possibilitythat participating in the diary keeping increasedstigma directed against the ill person. In an attemptto avoid this, it was ensured that a wide range ofhouseholds, a number of which had not beendirectly affected by HIV/AIDS, participated in thewider research programme. However, I was acutelyaware of the potential sensitivities of the diary keep-ing, and asked diary keepers and HBC workers toinform me as soon as possible if they felt that partic-

ipation in the research was impacting adverselyupon them. During informal discussions with partic-ipants, it was in fact found that as well as relievingboredom, the diary-keeping process was found bysome to be therapeutic and that involvement in theresearch had made them feel that their opinionswere valid. On reflection, a greater understanding ofwhat role, if any, the diary keeping played in enablingdiarists to unburden any feelings of guilt, regret orsadness that they had been unable to talk about withrelatives or friends would also have been interesting,and would have added greater depth to understand-ing the process of diary keeping.

One key advantage of the diaries was that theygave authorial control to the diarist, enabling themto set their own agenda and reveal information asthey wished. While it is recognized that informationcould also be concealed (a problem faced equallythrough interview methods), the diaries gave inform-ants time to think through, define and prioritize theissues and experiences that they felt were mostimportant to them and to raise them as and whenthey wished. Rather than taking up significant chunksof their time as would have been the case withinterviews, informants were able to write as little oras much as they liked at times that suited them. Thiswas deemed an important consideration when thesehouseholds already faced serious pressures upontheir time and resources.

The time and emotional costs of the diary keepingraises questions about how, if at all, it was best toprovide short- and long-term support to participants.All of the households concerned were engaged insubsistence-based livelihoods, and time spent writingthe diaries diverted them away from these activities.The cash incentive was therefore provided to recom-pense them for their time. Participants were also givencopies of the photographs they had taken, which formany was considered important, especially when theyhad taken pictures of family and friends. There werealso times when I helped out by giving people lifts tothe clinic and occasionally providing food. Whilst theethics of these actions may be considered contentious,I was clearly in a position in which I could providesuch help and I would argue that the ethics of doingnothing in such a situation are morally dubious.

Another form of support identified as a result ofthe diaries concerned the role of the HBC workers.HBC workers reported that because they wereinvolved in monitoring the diaries, they visitedhouseholds and helped them with respite care andsupport more frequently than would have otherwise

Eliciting emotions in HIV/AIDS research

81

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

been the case. They also reported that they weremore aware of, and thus able to respond more fullyto the needs of the ill person and the carer.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that when used in conjunc-tion with other qualitative methods, solicited textand photo diaries can elicit in-depth and sensitiveinformation on the emotional impacts of HIV/AIDS.Whilst the findings are in no way intended to begeneralized to a wider population, they clearlyindicate that living with long-term and stigmatizedillness can play a central role in shaping people’sidentity, self-worth and well-being. From a policyperspective, such findings clearly indicate the needfor the development of locally appropriate coun-selling services which address the emotional andpsychological impacts of living with chronic illness,as well as encourage HIV testing, disclosure andsupport to reduce stigma and delay the onset ofAIDS-related illness. Given the time and resourcecosts of accessing formal health facilities, HBCworkers are well placed to play a central role insuch a development.

The use of solicited text and photo diaries facili-tated the collection of in-depth information onpeople’s emotional experiences, and enabled a levelof informant-directed research. However, whetherthese methods are emotionally harmful remainsunclear and the ethical implications of their usemust be fully considered in light of the context inwhich they are to be used.

Notes

1 Prior to the coffin being brought into the funeral ceremony,female relatives would gather in the courtyard of thedeceased to show collective displays of grief through loudwailing and screaming.

2 There are six major languages in use in the Caprivi Region.Because my translator spoke all of the languages of thearea fluently, it was possible for diarists to write (andspeak) in their preferred language during the research. Mytranslator was a trained Home Based Care Worker fromthe region who I recruited with the assistance of the localhospital.

References

Anderson

K and Smith

S J

2001 Editorial: emotional geogra-phies

Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers

26 7–10

Ansell

N

2001 Producing knowledge about ‘Third Worldwomen’: the politics of fieldwork in a Zimbabwean sec-ondary school

Ethics, Place and Environment

4 1010–16

Barbalet

J

2002

Emotions and sociology

Blackwell, Oxford

Basu

A M

2006 The emotions and reproductive health

Pop-ulation and Development Review

32 107–21

Baylies

C

2002 The impact of AIDS on rural households inAfrica: a shock like any other?

Development and Change

33 611–32

Bennett

K

2004 Emotionally intelligent research

Area

36414–22

Bolton

P and Wilk

C M

2004 How do Africans view theimpact of HIV? A report from a Ugandan community

AIDSCare

16 123–8

Bondi

L

2005 Making connections and thinking throughemotions: between geography and psychotherapy

Trans-actions of the Institute of British Geographers

30 433–48

Cloke

P, Cooke

P, Cursons

J, Milbourne

P and WiddowfieldR

2000 Ethics, reflexivity and research: encounters withhomeless people

Ethics, Place and Environment

3 133–54

Coxon

A P M

1999 Parallel accounts? Discrepancies betweenself-reported (diary) and recall (questionnaire) measures ofthe same sexual behaviour

AIDS Care

11 221–34

Crang

M

2003 Qualitative methods: touchy, feely, look-see?

Progress in Human Geography

27 494–504

Davidson

J and Milligan

C

2004 Editorial: Embodying emo-tion sensing space: introducing emotional geographies

Social and Cultural Geography

5 523–32

Dean

H

2003 Discursive repertoires and the negotiation ofwell-being: reflections on the WeD frameworks

WeDWorking Paper 4

Research Group on Wellbeing in Devel-oping Countries, Bath

Dixon

S, McDonald

S and Roberts

J

2001 AIDS and eco-nomic growth in Africa: a panel data analysis

Journal ofInternational Development

13 411–26

Dodman

D R

2003 Shooting in the city: an autophotographcexploration of the urban environment in Kingston, Jamaica

Area

35 293–304

Elliott

H

1997 The use of diaries in sociological research onhealth experience Sociological Research Online (http://www.socresonline.org.uk/2/2/contents.html) Accessed 5February 2005

Ezzy

D

2000 Illness narratives: time, hope and HIV

SocialScience and Medicine

50 605–17Finerman R and Bennett L A 1995 Guilt, blame and shame:

responsibility in health and sickness Social Science andMedicine 40 1–3

Foster G, Makufa C, Drew R and Kralovec E 1997 Factorsleading to the establishment of child-headed house-holds: the case of Zimbabwe Health Transition Review 7155–68

Friedland J, Renwick R and McColl M 1996 Coping andsocial support as determinants of quality of life in HIV/AIDS AIDS Care 8 15–31

Gregson S, Terceira N, Mushati P, Nyamukapa C andCampbell C 2004 Community group participation: can ithelp young women to avoid HIV? An exploratory study of

82 Thomas

ISSN 0004-0894 © The Author.Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007

social capital and school education in rural ZimbabweSocial Science and Medicine 58 2119–32

Harper D 2002 Talking about pictures: a case for photo elic-itation Visual Studies 17 13–26

Hubbard G, Backett-Milburn K and Kemmer D 2001Working with emotion: issues for the researcher in fieldworkand teamwork International Journal of Social ResearchMethodology 4 119–37

Katz J 1999 How emotions work University of Chicago Press,Chicago IL

Kearns R A 1995 Medical geography: making space for dif-ference Progress in Human Geography 19 251–9

Kearns R A 1996 AIDS and medical geography: embracingthe Other? Progress in Human Geography 20 123–31

Kearns R and Moon G 2002 From medical to health geography:novelty, place and theory after a decade of changeProgress in Human Geography 26 605–25

Kim-Prieto C, Diener E, Tamir M, Scollon C and Diener M2005 Integrating the diverse definitions of happiness: atime-sequential framework of subjective well-beingJournal of Happiness Studies 6 261–300

Latham A 2003 Research, performance, and doing humangeography: some reflections on the diary-photograph,diary-interview method Environment and Planning A 351993–2017

Laurier E and Parr H 2000 Emotions and interviewing inhealth and disability research Ethics, Place and Environ-ment 3 98–102

Markwell K 2000 Photo-documentation and analyses asresearch strategies in Human Geography AustralianGeographical Studies 38 91–8

Mathambo Mtika M 2003 Family transfers in a subsistenceeconomy and under a high incidence of HIV/AIDS: thecase of rural Malawi Journal of Contemporary AfricanStudies 21 69–92

McDowell L 2001 ‘It’s that Linda again’: ethical, practicaland political issues involved in longitudinal research withyoung men Ethics, Place and Environment 4 87–100

McGregor J 2006 Diaries and case studies in Desai V andPotter R B eds Doing development research Sage, London200–6

Mendelsohn J, Jarvis A, Roberts C and Robertson T 2002Atlas of Namibia: a portrait of a land and its people DavidPhilip, Cape Town

Meth P 2003 Entries and omissions: using solicited diaries ingeographical research Area 35 195–205

Meth P with Malaza K 2003 Violent research: the ethics andemotions of doing research with women in South AfricaEthics, Place and Environment 62 143–59

Milligan C 2005 From home to ‘home’: situating emotionswithin the caregiving experience Environment and Plan-ning A 37 2105–20

MOHSS 2004 HIV/AIDS sentinel survey results MOHSS,Windhoek

Monasch R and Boerma J T 2004 Orphanhood and childcarepatterns in sub-Saharan Africa AIDS 18 S55–65

Robson E 2001 Interviews worth the tears? Exploring dilemmasof research with young carers in Zimbabwe Ethics, Placeand Environment 4 135–42

Rohde R 2001 How we see each other: subjectivity, photo-graphy and ethnographic re/vision in Hartmann W, Silvester Jand Hayes P eds The colonising camera: photographs inthe making of Namibian history Out of Africa Publishers,Windhoek 188–92

Rugalema G H R 1999 Adult mortality as entitlement failure:AIDS and the crisis of rural livelihoods in a Tanzanian vil-lage Unpublished PhD thesis Institute of Social Studies,The Hague

Russell S 2004 The economic burden of illness for house-holds in developing countries: a review of studies focusingon malaria, tuberculosis, and Human ImmunodeficiencyVirus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome AmericanJournal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 71 147–55

Seeley J and Pringle C 2001 Sustainable livelihoodsapproaches and the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a preliminaryresource paper Overseas Development Group Universityof East Anglia, Norwich

Seeley J, Grellier R and Barnett T 2004 Gender and HIV/AIDS impact mitigation in sub-Saharan Africa – recognisingthe constraints Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS 1 87–98

Sen A 1999 Development as freedom Oxford UniversityPress, Oxford

Tan J A C, Härtel C E J, Panipucci D and Strybosch V E 2005The effect of emotions in cross-cultural expatriate experi-ences Cross Cultural Management 12 4–15

Thien D 2005 After or beyond feeling? A consideration ofaffect and emotion in geography Area 37 450–6

Thomas F 2006 Stigma, fatigue and social breakdown:exploring the impacts of HIV/AIDS on patient and carerwell-being in the Caprivi Region, Namibia Social Scienceand Medicine 63 3174–87

Widdowfield R 2000 The place of emotions in academicresearch Area 32 199–208

Williams A and Tumwekwase G 2001 Multiple impacts of theHIV/AIDS epidemic on the aged in rural Uganda Journal ofCross-Cultural Gerontology 61 221–36

Wilton R D 1999 Qualitative health research: negotiating lifewith HIV/AIDS Professional Geographer 51 254–64

Yamano T and Jayne T S 2004 Measuring the impacts ofworking-age adult mortality on small-scale farm householdsin Kenya World Development 32 91–119

Young L and Barrett H 2001 Adapting visual methods:action research with Kampala street children Area 33 141–52

Zautra A J, Davis M C and Smith B W 2004 Emotions, per-sonality, and health: introduction to the Special IssueJournal of Personality 72 1097–104