Ehtiopia in the World Economy

Transcript of Ehtiopia in the World Economy

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 1/26

Ethiopia in the World Economy: Trade, Private Capital Flows, and MigrationAuthor(s): Kenneth A. ReinertSource: Africa Today, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Spring, 2007), pp. 65-89Published by: Indiana University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4187793 .

Accessed: 27/04/2011 03:55

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=iupress. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Africa Today.

http://www.jstor.org

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 2/26

Ethiopiain theWorldEconomy:Trade,

PrivateCapitalFlows, and Migration

KennethA. Reinert

Economic globalization can be evaluated with reference to

at least three dimensions: trade, private capital flows, and

migration. For each of these dimensions, pathways through

which economic globalization can alleviate or contribute to

poverty can be identified. This paper makes a preliminary

examination of globalization and poverty in Ethiopia, one of

the world's poorest countries. Ethiopia's integration with the

world economy has specific features: Ethiopia is highly depen-

dent on the exports of a few goods, imports many armaments,

is largely excluded from global foreign direct investment

flows, benefits from large inflows of remittances, and derives

few benefits from the evolving global regime of intellectual

property. Despite a number of negative trends with regard to

globalization and poverty, there is room for small-win policies

that would enhance the role of globalization in supporting

poverty alleviation.

Introduction

Economic globalization can be evaluated with reference to at least threedimensions: trade, private capital flows, and migration. For each of thesedimensions, pathways through which economic globalization can help orhurt poor people can be identified. Forexample, exports of labor-intensivegoodshave the potential of supportingpoorpeople's incomes, but imports ofarmamentscan have disastrous mpacts, especiallyforpoor children.Capitalinflows in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI)can enhance employ-ment and technological learning,but unwise bond finance and commercialbanklending can precipitate crises with devastatingeffects forpoor people.Sortingout the positive andnegative impactsof increasedglobalization fromthe perspective of poor people is therefore of great importance. This paperattempts to do so using the circumstances of Ethiopiaas a referencepoint.

A few papershave taken up issues related to Ethiopia's involvementin the process of globalization. These include Asefa and Lemi (2004), Bour-guignon et al. (2004), Dercon (2003), Ramakrishna (2002), and Tessema

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 3/26

(2003).This paper will try to place these studies in the wider context of the

globalization-and-povertyresearchagenda.The economic challenges facing

Ethiopiatend to leadobserversto conclude that little can be done to improve

Ethiopia's engagementwith the globaleconomic system. This paperwill be

somewhat more optimistic, suggesting that the strategy of a country such

as Ethiopiain engagingthe world economy is best engaged n terms of whatWeick (1984)called "small wins."2The paperexplores potential small wins

within Ethiopia's graspin orderto identify specific strategies to make its

globalization more favorableto the poor.

Poverty

The most common measure of poverty is income poverty, a deprivationof

goods consumption due to a lack of necessary purchasingpower.Measuredin terms of purchasingpower parity (PPP),gross national income (GNI) per

capita in Ethiopia was just over US$700 in 2003, up from approximately

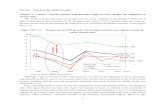

US$400 in 1985. Figure 1 comparesGNI per capita in Ethiopiawith that of

two other transitional economies, South Africa and Vietnam. What stands

out in this figureis the "flatness"of per-capita ncome in Ethiopiaovertime

in comparisonto these other countries.

In the parlance of the World Bank, individuals who subsist on less

than one dollar a day (1985 purchasing-powerparity dollars)are known as

the "extremely poor,"while individuals who exist on less than two dollarsa day (1985 purchasing-powerparity dollars)are known as the "poor."3For

Ethiopia,figureson the "poor"and "extremely poor" areavailablefor only

the year 2000. They indicate that approximately one quarterof Ethiopia's

population is "extremely poor,"but that more than three quartersof the

population is "poor."

There is a growing recognition that income poverty is not the only

importantmeasureof deprivation.With regard o health poverty,for example,

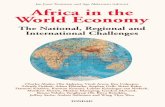

infant and child mortality are key indicators. As is indicated in figure 2,

approximatelyone in six Ethiopianchildren do not live to age five. Again,this figurecomparesEthiopiawith South Africa and Vietnam.While Ethio-

pia shows some improvementrelative to SouthAfrica, it falls far behindthe

gainsofVietnam,where infant and child mortality was cut in half in thirteen

years. Short of mortality,numerous morbidityissues are of central concern

for Ethiopia. For example, Christiaensen and Alderman refer to the "the

sheermagnitudeof child malnutrition in Ethiopia"(2004:288). n the case of

stunting,forexample,the rateis approximately60 percent ofall children,sig-

nificantlyabove an averageapproximately40 percentfor sub-SaharanAfrica.4

Bourguignonet al. (2004)note that, while downfrom its 1990level, the 2002maternalmortality rate (per 100,000 live births)was still more than 600.

Educationpoverty, including gender disparities, is important,both in

its own right and as a factor contributing to health poverty.5Bigsten et al.

(2003) suggest that primaryeducationplays an important role in translating

- -

0

0~0~

m

I

z

HIm

0

m

z0

. .

:n

0

-u

m

r)

-

0

z

0

G)

0

z

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 4/26

Figure 1. Gross national income per capita, PPP (current nternational $).

12 0 1 2 . .. . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .. . . . .. . . . . . . .. . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . .. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . ... . ............. . . ... . . . . ........... ..... . . . .. . .......... .. . .. . . .. . .. .

10000 -

8000 _ _ _ -

I~~

4000

2000 _ _ _

0

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003Yearn

Ethiopia Sout Africa - - Vienam|

Source:World Bank. (2006). WorldDevelopment Indicators.

Figure2. Under-fivemortality rate (per 1,000 population).

250!

200 --

150

, 100

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

__ .... ....

*_Ethlopia *SouthAf_,cc Ua_V_et ]

Source:WorldBank,WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006.

growth into poverty reduction in Ethiopia, albeit more for the urbanpoorthan the ruralpoor. Fortunately,it is here that we see a bit of good news.

As presented in figure 3, the gross primaryenrollment ratio has been on along-term, upward trend. More importantly, though, this ratio increased

rapidly during the 1990s, and the 2002 ratio was just under 62 percent.6That said, however, as noted by Bourguignonet al. (2004),Ethiopia'sprimarycompletion rate is below the average for sub-Saharan Africa.

-I

0z

z

I

zm

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 5/26

Figure 3. Grossprimaryenrollment ratio (percentof relevant age group).

70.0

r-L60.0

: 50.0-

0 40.0

"'O 30.0

w 20.0--

c 10.0

0.0

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

Years

- Gross Pnmary Enrollment Ratio (%)

Source: WorldBank,World Development Indicators 2006

Whetherfrom the perspectivesof income, health, oreducation, povertylevels are of grave concern forEthiopia.The orthodox view of the multilat-eral development institutions is that more domestic liberalization, growth,and globalization can help addressthis concern. Is this so? Dercon (2003)

analyzes domestic liberalization and concludes that it is poverty alleviat-ing overall, despite the fact that poor people in remote areas and with poorhousehold endowments do not necessarily benefit. With regard o growth,

Bourguignonet al. note that: "While the linkage between income growth and

income povertyreduction is quite tight, so that high growth leads to signifi-cant reductionsin income poverty, mprovementsin the other[humandevel-opment measures are]not readilyachieved from growth alone" (2004:1-2).With regard o globalizationmorebroadly,we considertrade,private capitalflows, andmigration in the remainder of this paper.

Trade

Of all aspects of globalization, international trade is held out as the greathope forpoverty alleviation.7Tradecan contribute to poverty alleviation by

expanding markets, promoting competition, and raisingproductivity, eachof which has the potential to increase poorpeople's real incomes; but, as therecenthistories of a number of countries demonstrate, it would be a mistake

to rely on tradeliberalization alone as a means of reducingpoverty.8A morecomprehensive approach,one that addressesmultiple economic and socialchallenges simultaneously and emphasizes the expansion of poor people'scapabilities, especially in health and education, is needed.9Nevertheless,trade has vital roles to play.

4s

P-t

0

0'0

I

5

~0

z

Im

0

zm

0

m

-

0

z

0

z

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 6/26

International trade is a means of expanding markets, and market

expansion can help generate employment and incomes for poor people.Comparisonsare often made between the wages of workers in poor-countryexport industries and the wages of workers in developedcountries. In these

comparisons,the wages of workers in developing-countryexport industries

often appear o be very low. Consequently,trade has often been identified asworseningpoverty;however,the more relevantcomparisonis between what

people mayhave earnedbefore and aftertradeopportunitieswere made avail-

able. From a povertyperspective,this could be between the wages of exportsector workers with agriculturalday laborers,both in the same developing

country. Here, it can often be seen that it is the alternative of agriculturaldaylaborthat is much worse. It is precisely this type of income comparisonthat draws workers into exportindustries.10

It must be kept in mind that not all exportactivity equallyraisespoor

people' s incomes. Exportingcanbest contribute to povertyalleviation whenit supports labor-intensive production, human-capitalaccumulation (botheducation andhealth),andtechnologicallearning.Inaddition, poorindividu-als' incomes depend on buoyant and sustainable export incomes, which inturn dependon exportprices.

International trade is a means of promoting competition, which in

many instances can help the poor. Increasedcompetition lowers the real

costs of consumption and production. For example, domestic monopolieschargemonopoly prices that can be significantly above competitive prices;

the competition introduced by imports erodes market power, loweringprices. These procompetitiveeffects of trade can make tight household bud-gets go fartherand lower costs of production.The latter can have additionalemployment effects advantageousto poor individualsby lowering nonwagecosts in labor-intensive production activities. Also, procompetitive effectscan arise in the case of monopsony power:here, sellers (small farmers,for

example) to the monopsony buyer can obtain higher prices for their goodsas the buying power of the monopsonist is eroded.

There is some evidence that international tradecanpromote produc-

tivity in a country, and productivity increases may in turn support poorpeople's incomes." It is not the case that exports of all types or in all coun-tries generatepositive productivityeffects, but there is evidence that this isthe case in certaininstances. Exportpostures can place the exportingfirms indirect contact with discerning international customers, facilitating upgrad-ing processes. Thereis no consensus within internationaleconomics on theextent of these upgradingeffects, but they nonetheless remain an importantpossibility, including in natural-resource-intensivesectors.'2

There are occasions where international trade can have direct health

and safety impacts on poor individuals, impacts that can be beneficial ordetrimental. Perhapsmost importantly,improvingthe poor people's healthoutcomes usually involves imports of medical products. It is impossible for asmall, developingcountrylike Ethiopiato produceall its neededmedical sup-plies, nor can it produceadvancedmedical equipment, but many developing

AO

0-I

0

0~

z

-4

m

z

-4i

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 7/26

Figure 4. Total tradeas a percent of GDP.

120

i ##

100- S

~^

~^ . 4

* 60-

-5-

40 _

20

0-

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Years

I- Etiopia - SoutAfrica - - Vietnam

Source:WorldBank, WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006

counties import largeamounts of weaponryandexportsexual services,both

of which can have dramatically negative outcomes for the health andsafetyof poor individuals.13 In addition, the production processes of some export

industries can adversely affect the health of workersin those industries, anda small but important amount of trade involves hazardous-wastedumping.

Ethiopia has increased its involvement in international trade, though

less rapidly than other countries. Figure4 plots the standardmeasure of the

sum of exports and imports as a percent of GDP for Ethiopia, South Africa,

and Vietnam. Note that, in the mid-1980s, Ethiopia was slightly moreengaged n tradingactivities than Vietnam, whereas in the most recent years,

its total trade has been less than half of Vietnam's, measured as a percentof GDP. In comparison with South Africa, however, Ethiopia has slowly

achieved parity in this measure of trade openness.Ethiopia's export profile is presentedin figure 5, which shows Ethio-

pia's dependenceon coffee exports. Primary commodity dependence of this

sort has several drawbacks rom the viewpoint of poverty alleviation. First s

the secular, downward trend in commodity prices. Second is the escalating

protection in primarycommodity markets in developed countries.'4Third isthe monopsonistic pricing along commodity chains practicedby majorcoffeemultinationals.15This dependence problem was apparent as coffee-exportrevenues fell by more thanUS$100 million between 1999 and 2001, as coffee

prices fell to a thirty-year low. As noted by Oxfam (2002a),this decline inexportrevenues more than offset the debt relief Ethiopia obtained from thehighly indebtedpoor country initiative, and many Ethiopian coffee farmers

have been forced to shift to the production of chat, a stimulant used in the

regionaround the Red Sea.

0

z

-4

I0

a

m

n0

0

0

z

r

-v

m

<DO

r-

0

m

r)

0

z0

.5

-O

0En

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 8/26

Figure 5. Ethiopia's exports by product group, 2003 (percent and US$ million).

60.-00 160

50. 00 - 140

=40.0oo -_ \ -

120

O10030.00 ~~~~~~~80

40L0.00 - _ A - 86?o

400.00 - _o - 20

0.00 X 0

Source: International Trade Centre.

We must be careful in interpreting data such as presented in figure 5.

Such descriptions exclude trade in services, which is significant for Ethiopia.

Figure 6 plots commercial service exports as a percent of total exports. This

has been on a steady, though somewhat volatile, upward trend, reaching

nearly half of total exports in 2002. As any passenger on Ethiopian Airlines

will appreciate, the bulk of Ethiopia's service exports is accounted for by

transportation services. It is therefore important to consider the full range of

Ethiopia's trade engagement, not the traditional, commodity-only view.

Despite the pressing human development needs of the poorest coun-

tries such as Ethiopia, arms imports have at times composed a significant

part of its total imports, and government military expenditures have been

a significant part of total government expenditures. This is illustrated for

various years (determined by data availability) in figure 7. The vertical bars

in this figure plot government military expenditures as a percent of total gov-

ernment expenditures. For the years in which data are available, this ranged

from just over 20 percent to nearly 55 percent. The line in figure 7 plots arms

imports in constant 1990 U.S. dollars. This peaked in 1998 at approximately

US$200 million, but has composed up to one fifth of total imports at times.

Such trade cannot be conceived of as alleviating poverty. Indeed, in the case

of Ethiopia (and Eritrea), it has been nothing less than a catastrophe, and it

is difficult to conceive of a more perverse role for trade than in facilitating

the death and injury of the very people it should be benefiting.p6

C1)

-4

0

m

z

z

m

m

m

--

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 9/26

Figure 6. Commercial service exportsas a percent of Total.

60 -

50 -

40

300

20-

10 -

0

Years

Comm Ser Exp as % of Exp

Source:WorldBank, WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006

Figure 7. Arms imports and military expenditures as a percent of totalexpenditures

6 0 .0 ... .. . .. ... .. .. . ..... .. . .. . . . . ... . . ... ..2 5 0

50.0 -.- 200

40.0 - :

150

LL 30.0

100

20.0

50

10.0

.00 0

1990 1991 1997 1998 1999 2000 2002

SMectedYeam

j-=MifitaryExpenditure -*-ArmsIn9borts

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2006

p;0

m

I

0

a

:>

z

I

m

0

m

0

z

0

--

0

m

0

H

:>a

E

0

z

0

-0

m

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 10/26

Private Capital Flows

Private capital flows are an important resource for developing countries.

Capital flows augment domestic savings and can contribute to investment,growth, financial sector development, technology transfer, and poverty

reduction;however, there is substantial evidence that capital flows entailpotential costs that areboth much larger hanin the case of trade anddispro-portionatelycarriedby the poor.Additionally, t has become clear that not allcapitalflows are the same in their benefit and cost characteristics.Forthesereasons, a careful assessment of the impact of capital flows on poverty doesnot lend itself to across-the-board tatements. Rather,the cost and benefitcharacteristics of distinct types of capitalflows must be consideredin detail.Here, we distinguish among foreign direct investment, equity portfolio

investment, bond finance, and commercial bank lending.

The financial markets involved in equity portfolio investment, bondfinance, and commercial bank lending are characterizedby a number ofmarket failures. In normal circumstances, these imperfections tend to con-tribute to a certain amount of market volatility. Under circumstancesthat are not fully understood (but are particularlyimportant in emergingeconomies such as Ethiopia), they can lead to full-blown financial crises.Imperfections in financial markets appearto be particularlyproblematicwhen commercial banks in developing countries are given access to short-term foreign lending sources."7The resulting problems have three causes.

First, systems of financial intermediation in developing countries tend torely heavily on the banking sector, other types of financial intermediation

typically being underdeveloped.Second, developing countries have been

encouragedto liberalize domestic financial markets, sometimes beforesys-tems of prudentialbankregulationandmanagementareput in place. Third,developing countries have sometimes prematurely liberalized their capitalaccounts.'8Consequently,care must be takenin managingevolvingfinancialsystems and their access to international capital flows.

ForeignDirectInvestment

Foreigndirect investment can have positive impacts on poverty by creat-ing employment, improvingtechnology and human capital, andpromotingcompetition. Not all kinds of FDIcontributein this way, however, andsome,

through unsafe working conditions and environmental degradation, canadversely impact certaindimensions of poverty.Nevertheless, if we were toidentify the most promisingcategoryof capitalflows from the point of viewof poverty alleviation, FDIwould be it.'9

Many developing countries lack access to the technologies availablein developedcountries, andhosting multinational enterprises(MNEs)fromdevelopedcountries is one way to gain access to that technology. There arelimits to technology transfer,however. First, MNEs will employ the tech-nology that most suits their strategic needs and not the development needs

pa

-h

0

m

z

-H

I

za

m

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 11/26

of host countries. Forexample, MNEs can employ processes that aremuchmore capital intensive than would be desired on the basis of host-country

employment considerations.20Second, MNEs have a strong tendency to

conduct their researchanddevelopment in their home bases, rather than inhost countries.2'

Despite these limitations, in some important cases, MNEs do trans-fer technology and establish significant relationships with host-countrysuppliersvia backward linkages. If a foreignMNE begins to source inputslocally, rather than by importing them, the host countrycan gain importantbenefits. First,employment can increase, since the sourcedinputs representnew production. Second, production technologies can be better adaptedtolocal conditions, since suppliersare likelier to employ labor-intensivepro-cesses. Third, the MNE can transfer state-of-the-art business practices and

technologies to the local suppliers. Fourth,the local supplierscan coalesce

into a spatial cluster that supportsinnovation andupgrading.22Another avenue throughwhich MNEs canpositively affect host econo-

mies is through "spillovers" to other sectors of these economies. The

evidence to date suggests that such spillovers do occur in some circum-

stances and can be significant; however, in the words of Blomstrom and

Sj'oholm,they are not "guaranteed,automatic, or free" (1999: 916). Whatdetermineswhether positive technology spilloverswill occur?Manyfactorsare involved, and these include host-country policies, MNE behavior,andindustry characteristics.A key factor is the capacityof local firms to absorb

foreigntechnologies. BlomstromandKokko(2003)suggestthat learning is akey capacitythat is responsiveto varioushost-country policies, and evidencepresented in Tsang, Nguyen, and Erramilli (2004) in the case of Vietnam

supportsthis view.

There is some evidence that MNEs in Africa offer higher wages thandomestic firms.23This effect is more predominantforskilled than unskilledworkers. FDIcan therefore have differentialimpacts that exclude unskilledworkers.This can result in what te Velde (2001)calls the "low-income low-skill trap."All these considerationspoint to the role of basic education and

skill development in making the most of FDIforpoverty alleviation.24The low-income countries as a whole arelargely excludedfrom global

FDI flows. Forexample, in 2002, low-income countries received only twopercentof total FDIflows, with nearlyhalf of this going to Indiaand Vietnamalone. Figure8 compares Ethiopiawith SouthAfrica andVietnam and showsthat,with the exceptionof a few yearsin the late 1990s, FDIflows into Ethio-piahave been nearly nonexistent. This situation poses a serious challenge tothe country.As we discuss below, the countrymight be able to make betteruse of its diaspora o stimulate inflows of FDI,since these individuals will be

better able to overcome information gapsregarding he investment climatein the country.A regional approachto FDIunder the Common Market forEasternand Southern Africa (COMESA)s another possibility.

p

O-t-

-I0

Im-oz

H

0

0

:p

m0

-v

0

z

H

0z

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 12/26

Figure 8. Net foreigndirect investment as a percent of GDP.

1 4 . - --........ -- -- - --------..............

12 -

9 N~~~~~~~~~

10 /

19A,S-1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1999 1996 1997 1999 1999 2009 2901 2002 2003

8- Sot h Afic a

Source:WorldBank, WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006

EquityPortfolio nvestment

Thereis evidence that capital inflows in the form of equity portfolio invest-

ment might be more beneficial thanboth bond finance andcommercial bank

lending. Reisen and Soto (2001) have examined the impact of all four capitalinflows considered hereon growthfora sampleof forty-fourcountries.Theyfound that FDI, considered above, did indeed have a positive impact on

economic growth. The most positive growth impact, however, came from

equity portfolio flows. Bond finance, considered below, did not have anyimpact on growth,and commercial banklending, also consideredbelow, had

a negativeimpact. These results suggestthat equity inflows, alongwith FDI,could play an especially positive role in growth, development, and povertyalleviation.

Why canequity portfolioinvestment playapositive role in growthanddevelopment, at least under some circumstances? Rousseau and Wachtel

(2000) summarize research on this question with four possibilities: equity

portfolio inflows arean important source of funds for developingcountries;the developmentof equity marketshelps providean exit mechanism for ven-

ture capitalists, increasing entrepreneurialactivity; portfolio inflows helpdeveloping countries move from short-term finance to longer-termfinance

and help finance investment in projects that have economies of scale; the

developmentof equity marketsprovidesan informational mechanism evalu-

ating the performanceof domestic firms and can help provide incentivesto managersto performwell.

With regard o volatility, there is evidence that institutional investors

managing equity flows are less likely than banks to engagein herd and con-

tagion behavior;5however,in general, equity marketsareunderdevelopedn

-

0

n

i

z

zm

I

:>

m

z

H:x

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 13/26

much of the developingworld. Forexample, nearly the entire net portfolioequity inflows into sub-SaharanAfrica are accounted for by one countryalone: South Africa. The WorldBank summarized the features of developing-country equity markets as follows:

Marketcapitalizationas a shareof GDPin low-income coun-tries is about one-sixth of that in high-income countries.... Stockexchanges n developingcountriesalso tend to lag

technologicallybehinddevelopedmarkets.Technology laysa

major olein thetrading, learance,and settlementprocesses;

problems n those areas can discourage ophisticated nves-

tors. Institutions that superviseand supportthe operationof the stock exchange also tend to be weakerin developingcountries.(2004:95)

The development of equity markets in low- and middle-income coun-

tries is more complex than it might first appear.This situation reflects theincreasedglobalizationof financial services. Observershave shown a set of

domestic factorsto be particularly mportantin equity-marketdevelopment.These factors include sound macroeconomic policies, minimal degrees of

technology, legal systems that protect shareholders, and open financial

markets. However, as pointed out by Claessens, Klingebiel,and Schmukler

(2002),these areprecisely the factors that tend to promote the "migration"

of equity exchange out of developing countries to the majorexchanges infinancial capital of developed countries. This migrationprocesscomplicatesstandardnotions of equity-marketdevelopment. Steil (2001)has argued hatthe way forward s to link local marketswith globalmarkets;however,theremight remain medium-sized firms with local information needs that couldbenefit from some kind of domestic equity market. This is an area thatrequiresurgent attention for the development of novel approaches.

At present, inflows of equity investment into Ethiopiaareessentiallynonexistent. As in the caseofFDI,then, this situationrepresentsa significant

challenge to Ethiopian policymakers. We take up this challengebelow.

Bond Financeand CommercialBankLending

Inthe minds of the financialworld, there aresignificantdifferencesbetweenportfolio equity investment and debt. This shows up in the fact that, in thecase of bankruptcy,debt is given priorityover equity. This tends to supportthe preference or debtoverequity in markets,apreference hat appears o bemisplacedfrom a developmentandpoverty-alleviationperspective.At pres-

ent, inflows of bond finance into Ethiopiaarenonexistent. Froma povertyperspective, this is not a cause of greatconcern at present; greaterbenefitswould be attained from increases in FDIand equity-portfolioinflows.

With regardto commercial banks, Dobson and Hufbauer note thatbank "lending may be more prone to run than portfolio capital, because

P-3

-I

0

0~4ON

H

-vi

mI

a

z

I

0

0

z0

m

0

0m

D

H

0

z

C')

a>

--

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 14/26

banks themselves arehighly leveraged, and they arerelying on the borrow-

er's balance sheet to ensure repayment"(2001:47).The World Bank notes,"Incentives are key to limiting undue risk-takingand fraudulent behavior

in the management and supervision of financial intermediaries-especiallybanks that are prone to costly failure"(2001:3).

What can be done to supportthe safe development of banking sectorsin low-income countries such as Ethiopia?Some of the necessary steps canbe thought of in terms of information, institutions, and incentives. Withregardto information, it is importantfor banks to embraceinternationallysanctioned accounting and auditing proceduresand to make the results ofthese assessments available to the public. In the case of institutions or therules of the "banking game," risk-management practices (both credit and

currency)must be sufficiently stringent, andprudentialregulation systemsmust be well developed. With regardto currency risk, the World Bank

notes that "particularcare should be taken to ensure that foreign-currencyliabilities are appropriatelyhedged" (2004:30).26These informational and

institutional safeguardsare no small task andinevitably cannot be achievedin the short term. Consequently, they should be buttressed with incentivemeasures in the form of market-friendlytaxes on banking capital inflows.

Debt flows in the form of bondfinance and commercial bank lendingappear o have differentpropertiesthan equity flows in the form of FDIandportfolio-equity investment. They are more prone to the imperfect behav-iors that characterize financial markets, and do not appearto have positive

growth effects as largeas those associated with equity flows. Consequently,the utilization of debt finance must be cautious and sufficiently hedgedagainst exchange rate risks.

Migration

Historical analysis demonstrates that international migration can offer aneffective means forpoor people to escapepovertywhile promoting economic

growth and technological progress.27Communities can be lifted out of pov-erty via remittance flows from the country's diaspora.Also, when migrantsare successful in business endeavors, the diasporacan become involved intrade and capital flow networks that facilitate market access, investment,and technology transfer.That said, however, migration can be devastatingto those left behind. Migrantscan take with them critical skills, especiallyin the area of health. Further,the loss of household heads, innovators, andsocial leaders can cause a broadarrayof costs, including to social cohesion.As noted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

(2005)among other, the loss of highly skilled workers through emigrationcan have a deleterious impact on long-term economic development. Sincehighly skilled workers tend to generate the largest share of tax revenues,emigration can have detrimental impacts on the tax base, with additionaleffects in the areasof public services and infrastructure.Some governments

-I

0

zz

I

z

m

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 15/26

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 16/26

Figure9. Foreignremittances (currentUS$ millions).

60.0 -

50.0-

c 40.0 -

30.0-

e

20.0-

10.0

0.01996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Years

a Remitances

Source:WorldBank, WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006

Figure10. Foreignremittances as a percent of FDI.

10 0 . - -------------. ---------- ----.-----------------.-

90

80-70-60-

L 40-30-20-100

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Yearn

mRemit as1, % oFDI1

Source:WorldBank,WorldDevelopment Indicators 2006

InternationalTrade

The tradechallengefacingEthiopiafromthe viewpoint ofpovertyalleviation

is to promote labor-intensiveexports in orderto supporta widely dispersedexpansion of incomes. This practice will not occur through an automatic

comparativeadvantageprocess,andit is moreproductiveto think in terms of

potentialcompetitiveadvantagesn narrowproductcategories.It is important

to be alert to any potential cluster effectsamongthese productcategories.For

I-A.

C1)I

z

z

m

"I

-4

m

z

m

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 17/26

example, Ethiopia'sexport profile suggests that it is possible to think about

the emergence of cotton productsand leather clusters. Given the success of

the African Cotton Initiative in the WorldTradeOrganizationdispute-settle-

ment process,the future of cotton mightbebrighter han in the past.With the

right marketinganddocumentation, Ethiopiahas potential in organiccotton-

productniches in Europeand the United States. Moregenerally, t could takeadvantageof the increase in China's demand for cotton that accompanies

China'srapidlyexpandingexportsof clothing.Withregardo leatherproducts,the presence of the COMESALeatherand Leather Products Institute (LLPI)in Addis is a positive sign; such institutes are often at the center of emerg-

ing clusters. With regard o both cotton and leatherproducts,the EthiopianMinistry of Trade and Industry's nvolvement in the 2004 United Nations

IndustrialDevelopment Organizationworkshopon these sectors is apositive

step, particularly or strengtheningthe leathersupply chain.32

In the case of coffee, the promotion of "fairtrade" certification wouldensure the maximum value for developing country producers n the face of

export price declines.33As noted by Oxfam, "At the OromiyaCoffee Farm-

ers Cooperative Union in Ethiopia,farmerscan get 70 percent of the export

price for coffee that sells as FairTrade,while those in the Jimma zone of

Ethiopia's Kafaprovince, selling in the open market, get only 30 percent"(2002a:41).Given the magnitudeof the coffee crisis, it is difficult to disagreewith Oxfam's assessment that "whether or not Fair Trade can be appliedin the mainstream, the lack of alternatives and the absence of government

safetynets forpoor producersmake this sort of supportto farmersan entirelyjustifiableandappropriate ttempt to cope with the human cost of the rigorsof the free market" (2002a:42).Expansion of fair-tradeopportunities for

Ethiopia'scoffee farmers is thereforea key priority, especially in light of thedifficulties outlined by Talbot(2002) n attemptingforward ntegration alongthe coffee commodity chain.34Forwardntegration alongthe tea commodity

chain is easierthan forcoffee, but promotingfair-tradeopportunitiesfor the

expandingtea sector is also important.The movement of naturalpersons(WTOMode4 of servicestrade)offers

large potential benefits to a countrysuch as Ethiopia.Though Ethiopia s nota member of the WTO, it needs to make as much use of this service-trademode as possible through bilateral arrangements.As Winters et al. (2002)have shown, the gains for developing countries from an increase of only 3

percent in their temporary aborquotas would exceed the value of total aidflows andbe similar to the expected benefits from the Doha Roundof trade

negotiations, with most of the benefits to developing countries coming fromincreased access of unskilled workersto jobs in developed countries.35

Ethiopia's exportof tourist services remains largely untapped, and the

potential for cultural tourism and ecotourism is great, especially so giventhe country'sairline and its diaspora's nvolvement in travel agencies. In arelated area, Ethiopia is largely excluded from the evolving global regimeof trade-related, ntellectual property.The government needs to follow thelead of India and begin to construct a traditional knowledge digital library

0

I

00

z

00

m

S

-1i

z

0

m

0

r-

z

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 18/26

containing a formal inventory of all culturalpropertythat its citizens mightexploit.36This inventory is important to prevent the theft of the country's

cultural patrimony. One importantarea s that of music copyright,but there

are others.37

As has been recently noted by a number of researchers, develop-

ing countries play a role in trade as nodes in global production networks(GPNs).38GPNs refer to the process whereby the productionof a final goodhaving previously taken place in a single country is broken down into dis-

crete steps, each taking place in differentcountries. The evolution of GPNs

has responded to technological progress n transportation,communication,

and data processing;reducedrestrictionson FDI nflows;and trade iberaliza-

tion. As noted by the WorldBank(2003),to date,Africahas been largelyleft

out of this important globalization process, and the United Nations Confer-

ence on Tradeand Development (2002)has questionedthe benefits involved

in GPN participation.It is unclear whether Ethiopiawill achieve the neces-sary policy and infrastructureprerequisitesto be a potential GPN partici-

pant,but sustained trade-related apacity building supportedby multilateral

financial institutions could potentially change this situation.

CapitalFlows

Both the Ethiopiangovernment and the Addis AbabaChamberof Commerce

have investigated the possibility of organizing an equities exchange-no

small endeavor.39 hough the presenceandupgradingof the Nairobi equitiesexchange in Kenya indicates that it might be possible, the first priority withregardto capital flows would be to ensure the prudential regulation of the

banking sector, with care given to strenuously conditioning its borrowing

in foreign currencies. Given this first step, one possibility would be to link

any nascent exchange to the one in Johannesburgn order o tap into existing

technology.More realistic still would be to give serious considerationto the

suggestion of Mwenda and Muuka (2001)for cooperation within COMESA

to form a regional equity market in orderto promote multiple listings and

cross-border quity investments. Given the liquidity requirements of equityexchanges, this would appear o be a wise option.

With regard o direct investment, the Ethiopia Investment Authority

(EIA) ould make better use of the country's foreign population to facilitateFDIflows. Inaddition,it makes sense to link the EIAtightly to the proposedCOMESARegional Investment Agency. As discussed above, it is simply acharacteristicof modern, global production that it involves international andregional networks. Attempting to "go it alone" with regardto investment

projectsis therefore shortsighted.

Migration40

Improving the benefits of migration includes strengthening the financialinfrastructure supporting remittances. New e-commerce technologies,

C)

-I0

00

7;mz

zm

I

m

zm;D

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 19/26

including foreign exchange markets andelectronic cards,offergreatpotential

to reduce the overall transaction costs. The availability of accessible remit-

tance services in expatriate communities and near the destination of the

people to whom the funds are to be transferred,which offer simple processes

in languages understood by the migrants, can greatly facilitate remittance

flows and can encourage the movement of remittances from unofficial andunregulated networks into regulatedflows-which is important to address

security andpoverty concerns. Beforerecommendingtax measures, official

savings associations, andother government-ledmechanisms to increase the

beneficial impact of remittances, care must be taken to ensure that these

will be welcomed by the diasporaitself. Otherwise, they will reduce their

remittances or revert to unofficial channels.To some degree, governments can influence skilled people's decisions

to leave and to keep their capital in the country by shaping the overall

environment for skilled people, providinga safe and secureworkingenviron-ment, reachingout to skilled people, andseeking their involvement in deci-

sionmaking. However, given the gapsin earningpowerand the attractions of

cosmopolitan environments, this holding power is limited, particularlyfor

poorcountries such as Ethiopia.Some countrieshave implemented programsto direct remittances into development-orientedinvestments. Forexample,the Mexican government has assisted Mexican emigrants in establishing"hometown associations," which support infrastructureand enterprisein

home communities and "economic development funds," in which contri-

butions are matched by the Mexican government. This effort has spawnedsimilar policies by El Salvadorand its emigrantcommunity.4'

Within the context of the African continent, the South African Net-

work of Skills Abroad (SANSA) offers a model for harnessing expatriates'

skills.42A primarypurposeof SANSA is to gatherinformation aboutexpatri-

ate South Africansin orderto assess how their skills can be best matched to

local needs. Modes of contribution by expatriates include participationin

training programs, echnology transferactivities, researchresult dissemina-

tion, and facilitation of business contacts and development.43Since South

Africa andEthiopiashare the characteristicof having diasporasconcentratedin relatively few countries, the SANSA model holds out some promises for

Ethiopia and could perhaps be replicated. Highly skilled migrants couldbe tracked through a data bank and catalogued for future consultationassignments. This data-gathering xercise could be achieved through volun-

tary, web-basedregistration, passenger surveys on Ethiopian Airlines, and

inquiries by embassy staff.44

Summary

Globalization is not a panacea,but small-win policy changes affecting trade,capital flows, and migration can benefit Ethiopia's poor. Trade, FDI, andmigrationcan be harnessedsynergisticallyto deliver a modicum of benefits

0-

-I

00

-4

I

0-40

z0

-4

-4q

x

C'

0

0

z0

:E

m

<

m

-

0

z

0

z

G0

K

--

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 20/26

from the inevitable process of globalizationthe country confronts. Leverag-

ing fair tradeand promoting natural resource clusters can provide gains in

export expansion. Of all capital flows, FDI andequities hold the most prom-

ise with regard o long-term povertyreduction.Ethiopiashould give serious

consideration to regional efforts within COMESA,with regard o a regional

investment agency and the development of a regional equities exchange.To prevent future crises, prudential regulation of commercial banking is

a priority.As a country with a diasporathat involves many highly trained

and motivated individuals, it can exploit the potential of this network, par-

ticularly because the country's position in air-transportationservices can

effectively tie it into this network.

In two respects, the focus of this paper s too narrow.First, as the work

of Bourguignonet al. (2004)makes clear, progresson an inclusive set of pov-

erty measures in Ethiopiawill dependon foreign resources, in the form not

just of privatetradeincomes, capital inflows, and remittances, but of publicor quasi-public foreign aid. Properly securing and managing these flows is

crucial for poverty reduction, but it involves a set of considerationsbeyond

the scope of this paper. Second, any amount of small-win policy changes in

Ethiopia, important as they are,will not change the external environment,

which remains, in many crucial respects, antagonistic to the success of

low-income countries. Protectionism, agricultural ubsidies, inappropriately

definedprotection of intellectual property,and resistance to the temporary

movement of labor-intensive service providersconstrain success. Forthese

reasons, the challenges facing Ethiopia are manifold and numerous indeed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thispaperdrawson a fruitful ollaborationwith IanGoldinandAndrewBeathon the subjectof glo-

balization nddevelopment,and Iam verygrateful o both of these individuals. have also benefited

fromconversationswithSisayAsefa,GelayeDebebe, and DaveKaplan, nd from comments by two

anonymousreferees.

NOTES

1. As noted by Eichengreen 2004),an "average"r"typical"inancialcrisiscan claim up to 9

percentof GDP. omeof the worstcrises, uch as those inArgentina ndIndonesia, educed

GDPby morethan 20 percent,declinesgreater hanthat whichoccurred n the UnitedStates

during the GreatDepression.This situationhas particular elevancefor potentialcapital-account iberalizationnAfricanountries, ince,as noted bySingh 1999),banking ectors n

this region arenotoriously ragile.Additionally, s documented by Stiglitz 2001)andWade

(2001),Ethiopiahas inthe pastbeen underpressureby the InternationalMonetaryFund o

liberalizetscapitalaccount.

p-

00

a0w

m

zm

-i

zm

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 21/26

2. Weicknoted,"Changinghe scaleof a problemcanchangethe qualityof resources hatare

directed at it. Callinga situationa mere problemthat necessitates a small win moderates

arousal, mprovesdiagnosis,preservesgains,andencourages nnovation"1984:48).

3. See Chenand Ravallion2004).

4. See alsoSilva 2005).

5. Ongenderdisparitiesneducation,see Schultz 2002).6. Theprimaryompletionratewasjustunder40 percent n2003,upfrom 15percent n 1993.

7. See Dollar ndKraay2004), orexample.Analternative iewisgiveninRodriguez ndRodrik

(2001).Athoroughreviewof tradeandpoverty sprovidedbyWinters,McCulloch,ndMcKay

(2004).

8. The fact that the trade-povertyalleviation inkageis not automatic has been stressed by

the United NationsConferenceon Tradeand Development(2004)in the case of the least-

developedcountries.

9. Oxfamnotes that,"In tself, rade is not inherentlyopposed to the interestsof poorpeople.

Internationalrade can be a force for good, or for bad.... The outcomes are not pre-determined.They reshapedbythe wayinwhich nternationalraderelationsaremanaged,

andbynationalpolicies"2002a:28).

10. In he case of Bangladesh, orexample,see Zohir 2001)and Oxfam 2002b).

11. Fora reviewof the evidenceon tradeliberalization ndproductivity,ee Winters,McCulloch,

andMcKay2004).

12. Onthe latterpoint,see de Ferrantit al.(2002).

13. Thispoint isemphasizedby Reinert 2004).

14. Tobefair, snotedbyOxfam,"importariffsntorich-countrymarkets renot the mainbarrier

for mostcoffee producers"2002a:33).15. This ssue was raisedby Brownand Tiffen 1992) and morerecently nthe case of coffee by

Oxfam 2002a). n he case ofcoffee,the mainplayersareKraft,Nestle,Procter&Gamble, nd

SaraLee.See alsoTalbot 2002).

16. The authorcannot resistrelating he observationof an individualromthe region that the

borderconflictbetween Ethiopiaand Eritrea as been like"twobald men fighting over a

comb"'

17. TheWorldBanknotes that"Ifinance sfragile,banking sthe mostfragilepart"2001:11).

18. For critique f prematureapitalaccount iberalization,ee Stiglitz 2000).As heWorldBank

notes,"Poorequencingoffinancialiberalizationna poorcountry nvironment asundoubt-edlycontributed o bank nsolvency"2001:89).Hanson,Honohan, ndMajnoni otethat"the

riskiness fcapitalaccount iberalization ithout iscaladjustment.. andwithoutreasonably

strongfinancialregulationand supervisionand a sound domesticfinancial ystem,is well

recognized"2003:10).Onpressures orpremature apitalaccountliberalizationn Ethiopia,

see Stiglitz 2001)and Wade 2001).

19. Thepresentpaper s inbroadagreementwithSingh, hatthe"experience f manyAsianand

LatinAmericanountrieswithportfolio apital lows .. indicate sic]thatthe Africanountries

would benefit fromusingtheirefforts and institutional esources o attractFDI ather han

portfolio lows"1999:356).tdoes,however,distinguishbetweenportfoliolows ntheformofequityinvestmentandthose inthe formof bondfinance,with a preferenceor the former.

20. Cavesnoted,"Survey vidence indicates hat MNEs o some adapting (of technologies to

labor-abundantonditions),butnot a greatdeal, and itappears hatthe costs of adaptation

commonlyarehighrelative o the benefitsexpected byindividual ompanies"1996:241).

-I

0

I

5

:0

z

H

I0

a

0

m

z0

Dm

0

m

-

0

m

z

0

-I

H

0

in

-om

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 22/26

21. Dunningnoted,"Withhe exceptionof some European-basedompanies, he proportion f

R&Dctivityby MNEs ndertakenoutsidetheir home countries sgenerallyquitesmalland,

in the case of Japanese irms,negligible"1993:301).

22. For he role of clusters in naturalresource-baseddevelopment,as might be important o

Ethiopia, ee Ramos 1998).

23. See te Veldeand Morrissey2003).24. Borensztein,DeGregorio, ndLee(1998) ind that it isthe combination f FDI nd education

that hasa statisticallyignificantmpacton growth.

25. Thisevidence isreviewed nchapter1of Dobsonand Hufbauer2001).Singh 1999), o some

extent,contests this conclusion.

26. Mistakesmadeinthese areashave proved o be too costly o the poor nthe pastforcountries

to relax heirvigilance.Prasad t al.conclude hat:"The elativemportance f different ources

of financing ordomestic investment,as proxiedbythe followingthreevariables,has been

shown to be positivelyassociatedwiththe incidenceand the severityof currency ndfinan-

cial crises: he ratioof bankborrowing rother debt relative o foreigndirect nvestment;heshortnessofthe term structure f externaldebt;and the shareof externaldebt denominated

inforeigncurrencies"2003:49).

27. Thissection drawson Beath,Goldin,and Reinert 2006).

28. See Lowell 2001).

29. See,forexample,CarringtonndDetragiache 1999).

30. Similar videnceforrisk haringwasfoundin the case of MalibyGubert 2002).

31. See Dugger (2004).Thishas the advantage of preventinga brain drain of health-sector

personnel.

32. UNIDOupports he roleof Ethiopian the International etworkforBambooandRattan, ndthis couldhave some futurepromise.

33. See Raynolds2000)and references herein.

34. Given he natureofcoffeeproduction,he onlyrealroom or orwardntegration s into nstant

coffee production.

35. Aspointedout by Puri,here s animportant enderelementhere:'Forhe majority fwomen,

Mode4 provides he onlyopportunity o obtainremunerativemploymentwithtemporary

movementto provide ervicesabroad. thas been found to have a net positiveeffect on the

economy and povertyreduction n the home country"2004:8).

36. Forexamples,see Sahai 2003)and Das 2006.37. The contributions o Silverman1999)are relevant nthisregard.

38. See,forexample,Bairand Gereffi 2001),Clancy 1998),Hendersonet al. (2002),andWorld

Bank 2003).

39. See Tessema 2003).

40. Someof the suggestions here draw romBeath,Goldin,andReinert2006).

41. See Stalker2001).Aspointed out by Kiggundu nd Oni(2004),Ethiopia id benefitforsome

time from the InternationalMigrationOrganization's eturnand Reintegration f Qualified

AfricanNationals;t hasbeen some time,however, ince thisprogramhas been inexistence.

42. SANSAs ajoint projectof the SouthAfricanNationalResearchFoundation ndDepartmentof Science andTechnology.

43. For urther nformation, ee http://sansa.nrf.ac.zand Kaplan1997).

44. The EthiopianNorthAmericanHealthProfessionalsAssociation s already nvolved n such

Activities;ee www.enahpa.org.

-I0V

00_n

m

zm

I

--.

zm

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 23/26

REFERENCES

Aredo,Dejene. 1998. SkilledLabourMigrationromDevelopingCountries:AnAssessmentof Brain

Drain romEthiopia. n HumanDevelopmentnEthiopia,dited by S.Siyoumand A.Siyoum.

AddisAbaba:EthiopianEconomicAssociation.

.2005. MigrationRemittances, hocksandPovertynUrbanEthiopia: nAnalysis f MicroLevelPanelData.AddisAbabaUniversity. ypescript.

Asefa,Sisay,and AdugnaLemi.2004. Challenges o RegionalIntegrationn Africa:mplicationsor

Ethiopia.Department f Economics,WesternMichiganUniversity. ypescript.

Bair,ennifer, ndGaryGereffi. 001. LocalClustersnGlobalChains:The ausesandConsequencesof

ExportDynamismnTorreon's lueJeansIndustry.WorldDevelopment 9:1885-1903.

Barratt rown,Michael, ndPaulineTiffen.1992.ShortChanged:Africand World rade. ondon:Pluto

Press.

Beath,Andrew, an.A.Goldin,and KennethA.Reinert. 006. Migration.nGlobalizationorDevelop-

ment,edited by 1.A.Goldinand KennethA. Reinert.London:PalgraveMacMillan.Bigsten,Arne,BereketKebede,Abede Shimeles,and MekonnenTaddesse.2003. Growthand Pov-

erty Reduction n Ethiopia:Evidence rom Household PanelSurveys.WorldDevelopment

31:87-106.

Blomstrom,Magnus,and AriKokko.2003. TheEconomics f ForeignDirectInvestment ncentives.

Cambridge,Mass.:NationalBureau f EconomicResearch,WorkingPaper9489.

and Fredrikjoholm.1999.TechnologyTransfer ndSpillovers:Does LocalParticipation ith

MultinationalsMatter?European conomicReview 3:915-923.

Borensztein, duardo,ose DeGregorio,ndJong-WhaLee.1998.HowDoesForeignDirect nvestment

AffectEconomicGrowth? ournal fInternationalconomics5:115-135.Bourguignon, rancois,Maurizio ussolo,HansLofgren,HansTimmer,ndDomiquevanderMensbrug-

ghe. 2004.TowardsAchievinghe MDGsnEthiopia: nEconomywideAnalysis fAlternative

Scenarios.WorldBank.Typescript.

Carrington,William .,and EnricaDetragiache.1999. HowExtensive s the BrainDrain?Finance nd

Development 6:46-50.

Caves,Richard .1996.MultinationalnterpriseandconomicAnalysis.nded.Cambridge: ambridge

University ress.

Chen,Shaohua,and MartinRavallion.004.HowHave heWorld's oorestFared incethe Early980s?

World ankResearchObserver 9:141-169.Christiaensen,Luc,and HaroldAlderman. 004. ChildMalnutritionn Ethiopia:CanMaternalKnowl-

edge Augment he Roleof Income?EconomicDevelopmentandCulturalChange2:287-312.

Claessens,Stijn,DanielaKlingebiel, ndSergioL.Schmukler.002. TheFuture f StockExchangesn

EmergingEconomies: volution ndProspects.Brookings-Whartonapers nFinancialServices

2002:167-202.

Clancy,Michael. 1998. CommodityChains,Services and Development:Theoryand Preliminary

Evidence rom heTourismndustry.Review fInternationalolitical conomy :122-148.

Das,Anupreeta.2006. India:Breath sic]In,and HandsOff OurYoga.Christian cienceMonitor,

February.de Ferranti,David,GuillermoE.Perry,DanielLederman, ndWilliamF.Maloney. 002. FromNatural

Resourceso theKnowledge conomy: radendJobQuality.Washington,D.C.:WorldBank.

Dercon,Stefan.2003.Globalisationnd the Poor:Waiting orNike nEthiopia.TijdschriftoorEconomie

enManagement 8:603-617.

"-A

0

;z

0

m

I-Qi

z

I

0

0

r

m

z0

m

0

m

r-

-a

0

z

0

0

In

-o

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 24/26

Dobson,Wendy, ndGaryC.Hufbauer.001. World apitalMarkets:ChallengeotheG-1O.Washington,

D.C.: nstitute or International conomics.

Dollar,Dollar, nd AartKraay.004.Trade,Growth, nd Poverty.EconomicJoumal14:22-49.

Dugger,C.W.2004. LackingDoctors,Africa sTraining ubstitutes.New York imes, 3 November.

Dunning,John H. 1993. Multinational nterprisesnd the GlobalEconomy.Workingham,England:

Addison-Wesley.Eichengreen,Barry. 004. Financialnstability. erkeley:University f California.ypescript.

El-Khawas,Mohamed. A. 2004. Brain Drain:Putting Africa between a Rock and a HardPlace.

Mediterranean uarterly5:37-56.

Gubert, Flore.2002. Do Migrants nsureThose Who Stay Behind?Evidence rom the KayesArea

(WesternMali).OxfordDevelopment tudies30:267-287.

Hanson, amesA.,PatrickHonohan,andGiovanniMajnoni. 003. Globalization nd NationalFinancial

Systems: ssuesof Integration nd Size.InGlobalizationndNationalFinancialSystems,dited

byJ.A.Hanson,P.Honohan,and G.Majnoni.WorldBank,Washington,D.C.

Henderson, effrey,PeterDicken,MartinHess,NeilCoe,andHenryW.-C.Yeung.2002. GlobalProduc-tion Networksand the Analysisof EconomicDevelopment.Review f International olitical

Economy :436-464.

Kaplan,David.1997.Reversinghe BrainDrain:The ase orUtilising outhAfrica's nique ntellectual

Diaspora. cience,TechnologyndSociety2:387-406.

Kiggundu,MosesN.,and BankoleOni.2004.AnAnalysis f the MarketorSkilledAfricanDevelopment

Management rofessionals:owardtrategiesnd InstrumentsorSkills etentionnSub-Saharan

Africa.Harare: fricanCapacityBuildingFoundation.

Lowell,BriantLindsay. 001. PolicyResponseso the InternationalMobility f SkilledLabor.Geneva:

International aborOffice.Mwenda, KennethK.,and GerryN. Muuka.2001. Prospectsand Constraints o CapitalMarket

IntegrationnEastern nd SouthernAfrica.JournalofAfricanusiness :47-73.

Organizationor EconomicCooperation nd Development.2005. TrendsnInternationalMigration-

2004. Paris.

Oxfam nternational.002a.Mugged: overtynYourCoffeeCup.Oxford.

2002b.RiggedRules nd DoubleStandards: rade,Globalization,nd theFightagainstPoverty.

Oxford.

Prasad,Eswar,KennethRogoff,Shang-JinWei,and M.AyhanKose.2003. Effectsof FinancialGlobal-

izationon Developing Countries: ome Empirical vidence.Washington,D.C. nternationalMonetaryFund.Typescript.

Puri,L.2004.TheEngendering f Trade orDevelopment:AnOverview.UnitedNationsConference n

TradeandDevelopment.Typescript.

Ramakrishna, . 2002.Growth,Povertyand Inequalitiesn Ethiopia:An Assessmentof the Impactof

Globalization. konomskastrazivanjaEconomicResearch 5:5-18.

Ramos,Joseph. 1998. A Development Strategy Founded on NaturalResource-BasedProduction

Clusters.CEPALeview 6:105-127.

Raynolds,Laura. .2000.Re-EmbeddingGlobalAgriculture: he InternationalOrganicand FairTrade

Movements.AgriculturendHumanValues 7:297-309.Reinert,KennethA. 2004. OutcomesAssessmentin TradePolicy Analysis:A Note on the Welfare

Propositions f the 'Gains romTrade."Journalf Economic ssues38:1067-1073.

Reisen,Helmut,and MarceloSoto. 2001.WhichTypesof Capital nflowsFosterDeveloping-Country

Growth? nternationalinance :1-14.

-I

0

z

z

H

I

zm

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 25/26

Rodriguez, rancisco, nd DaniRodrik.001.TradePolicyandEconomicGrowth:ASkeptic'sGuide o

the Cross-National vidence. nMacroeconomicsnnual2000,edited by BenBernanke nd

K.S.Rogoff.Cambridge,Mass.:MIT ress.

Rousseau,Peter L.,and PaulWachtel.2000. EquityMarkets nd Growth:Cross-Countryvidenceon

Timing and Outcomes, 1980-1995. Joumal of Banking and Finance 24:1933-1957.

Sahai, Suman. 2003. IndigenousKnowledgeand Its Protection n India.In Tradingn Knowledge:DevelopmentPerspectives on TRIPS, radeandSustainability, edited by C.Bellmann, G.Dutfield,

and R.Melendez-Ortiz.ondon:Earthscan.

Schultz,T. Paul.2002. WhyGovernmentsShould Invest Moreto EducateGirls.WorldDevelopment

30:207-225.

Silva, Patricia.2005. Environmental Factorsand Children'sMalnutrition n Ethiopia. Policy research paper

3489.Washington,D.C.:WorldBank.

Silverman,RaymondA.,ed. 1999.Ethiopia: raditionsf Creativity. ansing,Michigan:MichiganState

UniversityMuseum.

Singh,Ajit.1999.ShouldAfricaPromoteStockMarketCapitalism?ournal fInternationalevelopment11:343-365.

Stalker, Peter. 2001. The No-Nonsense Guide to International Migration. Oxford: New International

Publications.

Steil,Benn.2001.CreatingSecuritiesMarketsn DevelopingCountries:ANewApproachor the Age

of AutomatedTrading. ntemational inance :257-278.

Stiglitz,Joseph. E. 2000. Capital MarketLiberalization, conomicGrowth,and Instability.World

Development 28:1075-1086.

.2001. ThanksorNothing.AtlanticMonthly,October, 6-40.

Talbot,John. M.2002.TropicalCommodityChains,ForwardntegrationStrategiesand InternationalInequality: Coffee, Cocoa and Tea. Review of International PoliticalEconomy 9:701-734.

Tessema,Asrat. 003.ProspectsandChallengesorDevelopingSecuritiesMarketsnEthiopia.African

Development Review/Revue Africaine de Developpement 15:50-65.

teVelde, DirkW.2001. GovemmentPolicies towardInwardForeign Directlnvestmentin Developing Coun-

tries.Paris:OECDDevelopmentCentre.

,and Oliver.Morrissey.003. DoWorkersnAfricaGet a WagePremium fEmployed n Firms

Owned by Foreigners? Journal ofAfrican Economies 12:41-73.

Tsang, EricW. K.,Duc T. Nguyen, and M. KrishnaErramilli.004. Knowledge Acquisitionand

Performancef InternationalointVenturesntheTransition conomy fVietnam. ournal fInternational Marketing 12:82-103.

UnitedNationsConference nTrade ndDevelopment. 002.Trade ndDevelopment eport.Geneva.

.2004. TheLeastDeveloped CountriesReport 2004. Geneva.

Wade,Robert.H.2001.Capital ndRevenge:The IMF ndEthiopia.Challenge 4:67-75.

Weick,Karl.E. 1984. SmallWins:Redefining he Scale of Social Problems.AmericanPsychologist

39:40-49.

Winters,L.Alan,TerrieL.Walmsley,Zhen K.Wang,and RomanGrynberg.2002. Negotiating he

Liberalizations of the TemporaryMovement of Natural Persons. Discussion paper in economics

87. Sussex:University f Sussex.Winters,L.Alan,Neil McCulloch, nd AndrewMcKay. 004. TradeLiberalization nd Poverty:The

Evidence So Far.Journal of Economic Literature42:72-115.

World Bank.2001. Finance forGrowth:PolicyChoices in a VolatileWorld.Washington, D.C.

4)

-I00

0o00

mI

m

a

zHI

0

m

0

m

n0z0

f)H

0

-

-C

0z0

H)

0

z

8/7/2019 Ehtiopia in the World Economy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/ehtiopia-in-the-world-economy 26/26

. 2003. GlobalEconomicProspects nd the DevelopingCountries:nvesting o UnlockGlobal

Opportunities.Washington,D.C.

. 2004. GlobalDevelopmentFinance:HarnessingCyclicalGains or Development.Washington,

D.C.

. 2006. World evelopmentndicators006.CD-ROM. ashington,D.C.

Zohir,SalmaChaudhuri.001. SocialImpactof the Growthof [the] Garment ndustry n Bangladesh.BangladeshDevelopment tudies27:41-80.

p;

-I0

a

m

zm

I

z

Hm

--I