Education in West Papua

-

Upload

at-ipenburg -

Category

Travel

-

view

3.311 -

download

9

description

Transcript of Education in West Papua

Congress ‘Education in Papua’, Gau, Friesland, The Netherlands,

30 January to 1 February 2009

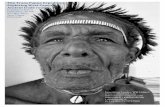

Education in West Papua1

At Ipenburg2

Summary

The paper discusses and evaluates the development of education in West Papua. It wants to

answer questions about the type of education that is most effective for Papua and for the

Papuans. What are the lessons to be learnt from history? How can Dutch organizations help

in an effective way in education for Papuans from Kindergarten to university? The paper

looks at formal and non-formal forms of education and training and also analyzes the political

and social context in which education takes place.

0. Introduction

We can distinguish five periods in Papuan history and for each period we will analyze the

role of education. These periods are (a) early period till 1900, the period where traditional

education dominated, (b) The period 1900 to 1950, the early beginnings of mission

education, mainly to train evangelist and gurus for the simple village schools, (c) The period

1950 to 1962, where the Dutch Government tried to make a giant leap forwards in education

to prepare the Papuans for self government and independence. (d) The period 1962 to 1998,

the introduction of an Indonesian curriculum, stressing the values of the Orde Baru

Government of Soeharto, (e) The period 1998 to present, a period where there are new

margins for improvement of the effectiveness of education, for foreign assistance and fro an

adaptation of the curriculum to the local conditions, including the introduction of the mother

tongue in the first years of the primary school and for literacy classes.

Papuan culture is characterized by extreme diversity. On the island of New Guinea over

1,000 different languages are spoken, divided into 60 language families. In West Papua 271

languages are spoken. 3 Only one quarter of these languages has been studied. Cultures

1 I will use West Papua for the Western part of the island of New Guinea. Previous names for this territory were: Papua Land (Tanah Papua), Nederlands Nieuw Guinee, Irian Barat, Irian Jaya and Papua. Since 2003 the Province Papua has been divided into the provinces of West Papua (the Bird’s Head and the Raja Ampat islands West of the Bird’s Head) with the capital at Manokwari and Papua with the capital; at Jayapura.2 At Ipenburg (1945), studied political science, African history (doctorate) and systematic theology in Amsterdam, London (SOAS) en Pretoria (UNISA). Ministerial studies in Leiden. Worked as lecturer and pastor in the Netherlands, Zambia and Indonesia (West Papua). Taught from 1995 to 2002 anthropology, sociology and ethics at the Theological College Izaak Samuel Kijne of the Evangelical Christian Church in Papua Land (GKI), also Director of the Master’s Program Missiology and minister of the GKI. Board member of HAPIN; candidate for D66 Democratsw at the European elections of June 2009.3 For more information about the interesting topic of linguistic diversity in West Papua see: The Ethnologue, web edition of the Summer Institute of Languages (SIL) at: http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?

1

show a similar diversity, indicating a creative genius of Papuans in this field. Traditional

forms of transfer of knowledge, like oral tradition, storytelling and rituals, have been

instrumental in preserving this diversity.

1. Early times to 1900: informal and non-formal education

For tens of thousands of years Papuans have been living on the island of New Guinea and

on other islands of the Indonesian archipelago and of the Pacific. On most islands the West

of New Guinea the Papuan population has declined, though remnants of it remain on Ceram

and Timor. People made a living by fishing, hunting, farming of sweet potatoes (batatas) and

vegetables, the pasture of pigs and the collecting of nuts and fruits in the forest.

The teaching of the skills to succeed was (and is) done in a non formal way. There is not

such a thing as a school, separated from society and specialized in the transfer of knowledge

to all age groups. Education was an integral part of traditional culture and imbedded in the

social structure. Young girls and boys were taught stories about the origins of the tribe and

clan, about the creation of the world, about the relationship between humans and the spiritual

world, with the animal and plant world in numerous stories. At the same time they were

taught all the practical skills needed for hunting and fighting to survive in a hostile

environment.

From an early age Papuans tend to live in men’s houses and women’s houses. Only the very

young boys were allowed to live with their mothers in the women’s house. The libraries of

this period were the memories of the old people and also the customs, beliefs that were

connected with sacred objects, with relationships in the social structure and with particular

places in the environment, like mountains, trees, lakes and so on. The schools were the

places where collective knowledge and skills were transferred to the new generation.

However, the school as an institution did not exist. Education was holistic and a part of every

aspect of traditional society.

2. 1900-1950: Mission education

The first missionaries Carl Ottow an d Johann Geissler, arrived on Sunday 5 February 1855

in West Papua on the island of Mansinam, close to Manokwari. They began by learning the

language and they prepared a word, list and grammar of the Numfor language. In 1863 the

Utrecht Mission Society joined the effort and send J.L. van Hasselt, other theologically

trained missionaries, but also some artisans. Local development was an integral part of

name=IDP

2

mission work. Formal education played an important role in bringing people into the fold of

the church. Education in a school building separated from other activities in society, was

something completely new. The first five decades the missionaries had very little success in

luring children to their schools. They tried to entice them with small gifts for their parents, just

as church goers would receive a small gift after the service. Several of the early pupils of

mission education were former slaves, bought to their freedom by the missionaries. They had

to do household chores, but also had to attend the house services in the house of the

missionary, the church services, twice on the Sunday, and to attend school. By 1890 school

attendacnce was 60, with 32 catechesis students. In 1892 two Papuans, Petrus Kafiar and

Timotheus Awendu, were send to the Depok Seminary, close to Jakarta, for training as

evangelists.

In 1898 and 1902 the Dutch Government established government posts in Manokwari, Fak-

Fak and Merauke. However, involvement with placed not in the immediate surroundings of

these three posts was minimal. Still, in the period following the establishment there was a

considerable increase in the number of Papuans who joined the church. By 1934 the mission

counted more than 50,000 Christians, most of them from the North of West Papua. There

was a similar growth in school attendance. In the same year the Utrecht Mission Society

(Utrechtse Zendingsvereniging,UZV) had in West Papua 157 schools with 8,650 pupils. The

UZV concentrated on Village Schools with a three years’ program. This was the method of

evangelization. A guru was send into a village to establish a school at the request of the

villagers, and at the same time he would establish a candidate congregation.

By 1937 the number of pupils on this type of schools had increased to 10,000. In 1942 the

Mission had 300 of these village schools. It had started to offer education in the local Papuan

languages, like the Numfor language in Mansinam and Wandamen (Windesi). However, the

Government demanded in 1911 already the use of Malay as a condition for its grants in aid.

Only the Numfor schools in the first year were exempted from this rule. Till 1950 there was

only attention for the teaching in Malay. The Dutch language did not play a role. These

village schools provided only the most rudimentary from of education. It is likely that even

those who learnt how to read and write soon fell back into illiteracy when they did not

practice their skills of reading and writing. Only those who continued to a higher form of

education benefitted. But only a very small percentage of pupils could continue. In 1937 for

50,000 pupils on the village schools there were only 50 places on the Upper Primary School

(grades 4 and 5) and 9 places on a vocational school.

The Roman Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (MSC) of Tilburg, started in

1905 a post in the South, in Merauke. They introduced the concept of the model kampong,

3

where life for all residents was strictly regulated. It was argued that without such discipline

the Marind-anim tribe would disappear. A venereal disease had spread and taken epidemic

proportions through adherence to traditional customs and rituals, like the otiv bombari ritual

which demanded sexual relations of all members of the tribe with a few women. The idea

was not uncontroversial. For instance, the Swiss anthropologist Paul Wirz, who had done

extensive research among the Marind-anim, was vehemently opposed to the method, which

according to him took away the cultural identity of this proud people of warriors.

The development of schools in the Catholic area was much slower. However, from the late

1920s there emerged a competition between Protestants and Catholics for the establishment

of schools. The mission that had established in a village a school could claim the village for

its mission. By 1940 the Roman Catholic Mission had 30 elementary schools in the South,

and 173 schools in the West, around Fak-Fak and in the Bird’s Head, where competition with

the Protestants was strongest.

3. 1950-1962: Preparation for self determination

In 1949 the Netherlands handed over sovereignty to the Government of the Federal Republic

of Indonesia (RIS). New Guinea remained outside the agreement. Pressure from Australia

that wanted a friendly power to control New Guinea, which had been used by Japan as a

spring-board for the invasion of Australia, played a role in this decision. West Papua could

now receive the full attention from the Dutch Government. The Dutch reported progress to

the new United Nations organization, as the Papuans the Dutch, following the Charter of the

United Nations, were now preparing the Papuans for self government. Education became the

priority, and the missions were enabled to expand their educational systems enormously,

with generous grants in aid from the Government. Hundreds of teachers were recruited from

the Netherlands.

From 1938 onwards West Papua had known a so called “civilization school”

(“beschavingsschool”). The aim was “to civilize” the Papuans with subjects like order and

hygiene, playing, flute playing, singing, the preparation of parties, dancing, school gardens,

basket weaving and the Three Rs. From 1945 onwards “people’s schools” (“Volksscholen”)

were founded with a more academic curriculum of Malay, reading, drawing, writing, singing,

flute playing and handicraft. After seven years “Volksschool” the best pupils could continue

to a “Vervolgschool”, hence VVS, which provided in a three years’ course a type of basic

secondary education. The Protestants were at an advantage as they had more and better

schools, so more of their pupils could continue to more advanced education. At the VVS a

4

Papuan elite was being formed. Here Papuans were selected for further studies to become

teacher, police officer or government official. Also here those Papuans were trained, who

later represented the Territory at international conferences like those of the South Pacific.

In 1948 the Protestant Mission, the United Netherlands Mission (“Vereenigde Nederlandsche

Zending”or VNZ) had in Northern New Guinea (Hollandia, Sarmi, Serui and Biak) 34

civilization schools and a total of 154 people’s schools (“Volksscholen”) with 227 teachers, of

which, however, only 99 were fully qualified. In Western New Guinea (Fak-Fak and Sorong)

the VNZ, the Protestant Church of the Moluccas and Roman Catholic Mission had in 1953 60

people’s schools with 1,873 pupils and 98 civilization schools with 2,999 pupils. The only

school then which offered more than very basic education was the Vervolgschool with a

three years’ program, established in 1945 in Yoka on the Southern shore of Lake Sentani.

The brightest boys were recruited from all over the Territory. They were housed in a boarding

school (“asrama”).

In 1955 the number of “Volksscholen” under management of the VNZ had increased to 325,

with 16,000 pupils. It had also 100 unsupported schools, established by evangelists in

villages, with 3,000 pupils. The number of inhabitants of West Papua was estimated in 1961

to be 750,000. This means that only a very small part of the youth had access to some form

of education. The system, moreover, was very elitist. From each 100 pupils only one could

continue to the “Vervolgschool.” After the VVS only a few of the abiturients could continue to

the Primary Secondary School (“Primaire Middelbare School”or PMS) or to the Lower

Technical School or to Agriculture Schools.

There was a Primary Secondary School (“Primaire Middelbare School” or PMS) in Kota Raja

with 80 pupils, which you could attend after the six years Volksschool and Vervolgschool.

There was an effort to adapt the curriculum to the Papuan context. For instance, history

teaching was in the first grade the study of the Middle Ages and the emergence of the Dutch

state with William the Taciturn and William III, in the second grade the history of China and in

the third grade, the history of New Guinea, beginning with the voyages of the explorers.

In the 1950s there was a strong effort by the Catholics to catch up with the Protestants in the

area of education. In 1953 the Vicariate of Jayapura had 39 Franciscan Friars. There were

102 Catholic village schools, with 130 teachers and 3,500 pupils. Three quarters of the

schools received government grants in aid. There was a General Primary School (“Algemene

Lagere School”) that used Dutch as medium of instruction. Sorong and Fak-Fak had also

such a General Primary School with 400 pupils. In that year five Sisters from Heerlen came

5

to work in Kokonao and Enarotali. In 1958 the Catholics opened a lower secondary school

(“Primaire Middelbare School”, hence PMS) in Hollandia, which had already a Protestant PMS.

To summarize, till 1960 there were six types of primary education:

(a) The Pioneer School (DSc), (b) The Village School with a three years’ program. For most

pupils this was the final from of schooling, (c) Some Village Schools with a four years’

program, (d) The Village School with a “Vervolgschool”, (e) The Central Village School

Vervolgschool, which was of a lesser quality, compared to the Town School, and finally, (f)

The Town School (“Stadsschool” or LSB). By 1960 there was not a Teacher Training College

or “Kweekschool”.

The Government established government schools with Dutch as medium of instruction: the

General Primary School (“Algemene Lagere School” or ALS). It had two categories, the ALS

“A” for Dutch children, and the ALS “B”for Chinese children. Papua children who could prove

that at home the Dutch language was used could also attend these schools.

6. Since 1962: Indonesianisation and physical expansion of education

With the sudden, and quite unexpected, change of Government with the handing over of the

control of New Guinea, first to the UN and then to Indonesia, there was a discontinuity. The

Indonesians suspected everything that was Dutch. So from one day to the other in education

one had to change from Dutch to Malay or Bahasa Indonesia. All text books in Dutch were

taken out of the schools and burnt. All textbooks of the Dutch period were replaced by those used

in the rest of Indonesia, though the stories were in no way appropriate to the culture and scenery of

New Guinea. Papuan children had to learn about a Javanese boy named Ahmed and about

volcanoes, trains and railways stations. The educated Papuans in church, the educational system,

commerce and government were suspected of being pro-Dutch and, by implication, anti-Indonesian. In

the security approach of the Indonesian army this meant that these were people declared to be the

“enemies.” In December 1962 there was a night raid on the dormitories of the Teacher Training

College, the Civil Servants school (“Bestuursschool”), the Agricultural College and the Christian

schools in Kota Raja in Jayapura, led by Indonesian soldiers, using pro-Indonesian groups. Students

were beaten up and then transported to the military camp at Ifar Gunung, where they were imprisoned.

A considerable group of respected Papuans ended up in prison or were killed. Among them were

Eliezer Jan Bonay, the first governor of Irian Barat (Irian Jaya, West Papua), Rev. G. A. Lanta, the

former vice-chairman of the Synod of the GKI, Rev. Silas Chaay, secretary of the GKI, Rev. Osok of

the Moi tribe of the Bird’s Head, Saul Hindom, who had studied in Utrecht and was the leader of Shell

in Biak, Hank Yoka, the former secretary of the New Guinea Council, Alfeus Yoku, a leader from

Sentani and David Hanasbey, inspector of police in Jayapura. Permenas Yoku, a teacher in Sentani,

6

was killed at the end of 1963, because he refused to sign a pro-Indonesian declaration4 Johan Ariks,

former chairman of the Papua delegation at the Round Table Conference in 1949, died, at the age of

70, in Manokwari prison, after a speech he held on 1 July 1965, which was considered to be anti-

Indonesian.Even the pro Indonesian Frits Kirihio, the first Papuan university graduate, ended up in

prison. 5

In 1969 there was a plebiscite which under strong intimidation of the Indonesian army did not produce

any dissent vote. After this Act of Free Choice the Government promised azutonomy for West Papua.

However, instead the territory got the status of Daerah Operasi Militer (DOM), which made the army

and police all powerful in the control of the people. There was a large influx of transmigrants, who

received plots of lands and grants, something that was not offered to local inhabitants. Moreover, a

great number of free migrants entered to settle. They occupied the major sections of the economy, like

building an retailing, but also the pasar, where products like vegetables and fish are sold. Papuans

cannot get in most cases a place in the market, but have to sell outside. According to the latest

statistics the number of indigenous people to immigrants is 52 to 48.6

The Indonesian Government made an effort to extend the educational system enormously. In 1971

already about 30,000 children over 10 years of age were at school.7 In 1980 the number of primary

schools had increased to 1,445, with almost 155,000 pupils and the number of lower and higher

secondary schools to 126, with almost 30,000 pupils. The University Cenderawasih in Abepura,

established in 1963, with four schools, had in 1976 1,039 students. 8 In 1996 of the 1.5 million

inhabitants of West Papua (Papuans and non-Papuans) 422,703 had completed their primary

education, 370,994 some form of secondary education or vocational training and as many as 11,682

had a university degree. 9

In May 1998, with the downfall of Soeharto and the ascent of Habibie, the era of Reformasi

began. There were hopes for a New Papua, but the period of Papuan Spring, were short-

lived. West Papua received a Special Autonomy Law in 2001 to meet the legitimate

aspirations of the Papuan people. It was offered as the same as Independence except for the

name. It did, however, not lead top real improvements in the situation of the Papuans as

many of the regulations of the law were never implemented. The number of immigrants

increased enormously, making the Papuans virtually a minority in their own land.

4 Z. Sawor, 1969: 40-45, quoting a Report by Silas Papare, member of the People’s Congress, Jakarta, 13 March 1967. Zacharias Sawor studied tropical agriculture in Deventer, the Netherlands, till 1962. He was treasurer of Parkindo, West Irian Section, from 1963 till 1965. He was in prison from August 1965 till August 1966. In June 1967 he fled to Australian New Guinea. Since October 1968 he lives in the Netherlands.5 Frits Kirihio had been in the Dutch period leader of the Christian National Trade Union, which had at that time 800 members.6 West Papua Fact Sheet, Franciscans International, 20097 Sensus Penduduk 1971, March 1974, Central Statistical Office, Jakarta.8 Irian Jaya Dalam Angka 1980, Kantor Statistik Irian Jaya 9 Irian Jaya Dalam Angka 1996, Kantor Statistik Irian Jaya

7

7. Conclusion

One should not idealize the short educational effort by the Dutch in the period 1950 to 1962.

The real value of it is in its principles of an education with the interest of the indigenous

people at heart. One could debate the efficacy of the system. The system only reached a

very small part of the youth in the relevant age group. Those who left school, without any

continued education in a “Vervolgschool” could easily fall back into illiteracy. Nevertheless,

those who continued all the way played later important roles in Papuan society. Many of

these were perceived by the Indonesian military and civil authorities as a threat and when

some of them were to critical they were murdered without a form of process. Later also

outspoken Papuan leaders like Arnold Ap, Thomas Wanggai and Theys Eluay were

imprisoned and murdered. The perpetrators were never being brought to court.

After 1962 Indonesia made a great effort to extend education and there was an enormous

increase in the number of schools and colleges. Immediately, in 1963, West Papua got a

university, the Cenderawasih University (UNCEN). However, notwithstanding this effort West

Papua remained relatively deprived educationally. The adult illiteracy level is 26 %, while in

Indonesia as a whole it is 11 %. 10 Moreover, the competition with migrants from other parts

of Indonesia is strong and generally speaking Papuans have a disadvantage on the labour

market because of prejudice against them. Mainly in enclaves, like the church and schools

and colleges under management by the churches, Papuans have an opportunity to advance.

Recommendations

1. Ongoing advocacy for Papuan human rights, political rights and the right to self

determination as these rights are instrumental for an effective system of education.

2. Specific support in the form of scholarships, combined with a form of super vision and

counseling of the bursaries, individual help with the preparation of a study plan and training

in study skills. training to make written assignments and theses.

3. Study facilities connected to a school or institution where the bursaries study or to the

asrama where they live in th form of a class room or study room with simple PCs and

printers.

10 West Papua Fact Sheet, Franciscans International, 20098

4. Pastoral guidance by a student chaplain. He or she would help the student to remain close

to the values received from the family and the congregation of origin of the church. Church

participation should be encouraged as it helps to give the student a feeling of personal value.

5. Specific training to improve one’s chances on employment, like courses in English, simple

accounting courses, courses in ICT, like web site design.

6. A special training unit for preparing aspiring Master and PhD students for the TOEFL

exam to increase their chances for a scholarship.

7. Lobby for special places for Papua deserving students at institutions, sympathetic to the

Papua case, like the Christelijke Hogeschool Ede, the Theological University Kampen, the

Free University Amsterdam, The ISS, similar to the schems offered to Black students from

South Africa during Apartheid.

8. Scholarships to neighboring countries, like the Philippines, PNG, Australia, New Zealand

and Fiji.

9. Special support for study and research to Papua music, dance, sculpture and art. Attention

for Christian art.

10. Setting up a system, in collaboration with theological colleges in Papua, to analyze and

preserve local languages. The collecting of traditional stories and myths. Encouraging the

use of local languages in worship. Translating parts of Scripture in these languages, setting

up and encouraging literacy ;programs using local languages.

11. Support for the organization of sport competitions among students to learn fair play,

discipline and team effort.

12. Helping with informal forms of education, for instance by the churches to improve lay

leadership. A good example of this is the Sekolah Al Kitab Malam (SAM), set up by Rev

Scheuneman in various towns

Bibliography

http://www.papuaweb.org/sitemap.html

Boelaars, J. 1991. Met Papoea’s samen op weg. Deel 1: De pioniers. Het begin van een missie,

Kampen: Kok (Series Kerk en Theologie in Context, Vol. 18)

9

Boelaars, J. 1995. Met Papoea’s samen op weg. Deel 2: De baanbrekers. Het openleggen van het

binnenland, Kampen: Kok (Series Kerk en Theologie in Context, Vol. 31)

Boelaars, J. 1997. Met Papoea’s samen op weg. Deel 3: De begeleiders. Kampen: Kok (Series Kerk

en Theologie in Context, Vol. 35)

Cornelissen, J. F. L. M. 1988. Pater en Papoea. Ontmoeting van de Missionarissen van het Heilig Hart

met de cultuur der Papoea’s van Nederlands Zuid-Nieuw Guinea (1905-1963), Kampen: Kok (Series

Kerk en Theologie in Context, vol. 1)

De Neef, Alb. J. Heidendom op Nieuw Guinea, Oegstgeest: Het Zendingbureau

Giay, Benny 1995. Zakheus Pakage and His Communities, Amsterdam: Free University Press (Ph.D.

Thesis)

Giay, Benny 1999. The Conversion of Weakebo. A Big Man of the Me Community in the 1930s, in: The

Journal of Pacific History, 34, 2

GKI dalam arus-pokok masa kini. Sidang Synode Umum GKI ke-V pada tgl 15-27 Oktober 1968 di

Sukarnopura, diterbitkan oleh Dinas Penerangana, Propinsi Irian Barat, Sukarnopura (GKI, 1968)

Haripranata SJ (ed) 1967. Ichtisar Kronologis Sedjarah Geredja Katolik Irian-Barat, Djilid 1,

Sukarnapura: Pusat Katolik, Idem: Djilid 2, 1969 and Djilid 3, 1970

Hayward, Douglas J. 1980. The Dani of Irian Jaya. Before and After Conversion, Sentani: Regions Press

Ipenburg, A. N. 1999. Een Kerk van Migranten; Een Kerk van het Volk. Tegenstellingen in Irian Jaya, in:

Wereld en Zending, 28, 4: 78-82

Ipenburg, A. N. 2001. Melanesian Conversion, in: Missionalia, 29, 3:

Ipenburg, A N 2008. A History of the Church in West Papua, in: Karel Steenbrink and Jan

Aritonong, 2008, A History of the Church in Indonesia and East Timor, Leiden: Brill

Kamma, F. C. 1953. Kruis en Korwar. Een Honderdjarig Vraagstuk op Nieuw Guinea, Den Haag:

Voorhoeve

Kamma, F. C. 1972. Koreri. Messianic Movements in the Biak-Numfor Culture Area, The Hague:

Martinus Nijhoff, 1972.

Kamma, F. C. 1976. “Dit Wonderlijke Werk,” Het Probleem van de Communicatie tussen Oost en West

Gebaseerd op de Ervaringen in het Zendingswerk op Nieuw Guinea (Irian Jaya) 1855-1972. Een Socio-

missiologische Benadering, 2 vols, Oegstgeest: Raad voor de Zending der Ned. Hervormde Kerk

10

Lewis, Rodger 1995. Karya Kristus di Indonesia. Sejarah Gereja Kemah Injil Indonesia Sejak 1930,

Bandung: Kalam Hidup, 1995

Miedema, J and W A L Stockhof (eds), 1991. Memories van Overgave van de Afdeling Noord Nieuw

Guinea. Irian Jaya Source Materials No 2 Series A No 1, Leiden, Jakarta

Miedema, J and W A L Stockhof (eds), 1993. Memories van Overgave van de Afdeling West Nieuw

Guinea. Part II. Irian Jaya Source Materials No 6 Series A No 3, Leiden, Jakarta

Neilson, David John 2000. Christianity in Irian (West Papua), Ph. D. Thesis, University of Sydney,

Australia (unpublished)

Rauws, J. 1919. Nieuw-Guinea, Den Haag: Zendingsstudieraad (Serie: Onze Zendingsvelden)

Rumaimum, F. J. S. 1966. Sepuluh Tahun G.K.I. Sesuduh Seratus Tahun Zending di Irian Barat,

Soekarnapura: GKI

Sawor, Zacharias 1969. Ik ben een Papua, Een getuigeverslag van de toestanden in Westelijk Nieuw

Guinea sinds de gezagsoverdracht op 1 October 1962, Groningen: De Vuurbaak

Sejarah Gereja Katolik Indonesia, Jilid 3A, 1974. Jakarta: Bagian Dokumentasi Penerangan KWI

Slump, F. 1935. De Zending op West-Nieuw-Guinee, Oegstgeest: Zendingsbureau (reprint from

‘Mededelingen.’ Tijdschrift voor Zendingswetenschap).

Sunda, James 1963. Church Growth in the Central Highlands of West New Guinea, Lucknow: Lucknow

Publishing House

Tanamal, Goeroe Laurens 1952. De Roepstem Volgend. Autobiografie van Goeroe Laurens Tanamal,.

(tr. and ed. by F. C. Kamma) , Den Haag: Voorhoeve (Serie: Lichtstralen op de Akker der Wereld, 53, 2)

Trompf, G. W. 1991. Melanesian Religion, Cambridge: University Press

Ukur, F. and F. L. Cooley 1977. Suatu Survey Mengenai Gereja Kristen Irian Jaya, (Serie: Benih Yang

Tumbuh 8), Jakara: DGI

Van den Broek, OFM, Theo P. A. (et. al.) 2001. Memoria Passionis di Papua. Kondisi Sosial Politik dan

Hak Asasi Manusia Gambaran 2000, Jakarta: Sekretariat Keadilan dan Perdamaian (SKP) Keuskupan

Jayapura and Lembaga Studi Pers dan Pembangunan (LSPP)

Van Baal, J. 1966. Dema. Description and Analysis of Marind-Anim Culture (South New Guinea) (with

the collaboration of Fr. J. Verschueren MSC), The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff

Van Hasselt Jr, F. J. F. 1926. In het Land van de Papoea’s, Utrecht: Kemink & Zoon

Vlasblom, Dirk. 2004. Papoea. Een geschiedenis, Amsterdam: Mets & Schilt

11

Vreugdenhil, C. G. 1991. Vreemdelingen en Huisgenoten, Houten: Den Hertog

12