Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

-

Upload

duke-university-press -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

1/29

MARISOL

DE LA CADENA

E ARTH BEINGS

ECOLOGIES OFPR ACT ICE ACROSS

ANDE AN WORLDS

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

2/29

E A R T H B E I N G S

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

3/29

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

4/29

Te Lewis Henry Moran Lectures / 2011

presented at Te University o Rochester

Rochester, New York

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

5/29

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

6/29

MARISOL

DE LA CADENA

EARTH BE INGSEC OL OG IE S O F

PRA CT I CE ACR OSS

A N D E A N W O R L D S

Foreword by Robert J. Foster and Daniel R. Reichman

Duke University Press Durham and London 2015

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

7/29

© 2015 Duke University Press

All rihts reserved

Printed in the United States o America on acid-ree paper ♾

Desined by Mindy Basiner Hill

ypeset in Garamond Premier Pro by sen Inormation Systems, Inc.

Library o Conress Cataloin-in-Publication Data

Cadena, Marisol de la, author.

Earth beins : ecoloies o practice across Andean worlds / Marisol de la Cadena.

paes cm — (Te Lewis Henry Moran lectures ; 2011)Includes biblioraphical reerences and index.

978-0-8223-5944-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

978-0-8223-5963-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

978-0-8223-7526-5 (e-book)

1. Ethnoloy—Peru. 2. Shamans—Peru. 3. Quechua Indians—Medicine—Peru.

I. itle. II. Series: Lewis Henry Moran lectures ; 2011.

564.434 2015

305.800985—dc23 2015017937

Cover art: Collae usin photoraph by the author.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

8/29

T O M A R I A N O A N D N A Z A R I O T U R P O

A N D A L S OT O C A R L O S I V Á N D E G R E G O R I

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

9/29

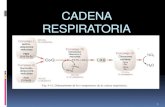

Ausangate and surroundings.

Ocongate

Pacchanta

AusangateMountain

AusangateMountain

N

0

0 4 62 8 km

3 421 5 mi

DEPARTMENTOF

CUZCO

Map Area

Lima Cuzco

P E R U

R o a d

to Cuzco

to Madre de Dios(Amazon rainforest)

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

10/29

CONTENTS

F O R E W O R D

xi

P R E F A C E

Endin Tis Book without Nazario urpo xv

S T O R Y 1

Areein to Remember, ranslatin,and Careully Co-laborin

1

I N T E R L U D E 1

Mariano urpo: A Leader In-Ayllu35

S T O R Y 2

Mariano Enaes “the Land Strugle”:An Unthinkable Indian Leader

59

S T O R Y 3

Mariano’s Cosmopolitics:Between Lawyers and Ausanate

91

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

11/29

S T O R Y 4

Mariano’s Archive:Te Eventulness o the Ahistorical

117

I N T E R L U D E 2

Nazario urpo: “Te Altomisayoq Who ouched Heaven”

153

S T O R Y 5

Chamanismo Andino in the Tird Millennium:Multiculturalism Meets Earth-Beins

179

S T O R Y 6

A Comedy o Equivocations: Nazario urpo’s Collaboration with the National Museum o the American Indian

209

S T O R Y 7

Munayniyuq: Te Owner o the Will

(and How to Control Tat Will)243

E P I L O G U E

Ethnoraphic Cosmopolitics273

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

287

N O T E S

291

R E F E R E N C E S

303

I N D E X

317

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

12/29

FOREWORD

Marisol de la Cadena delivered the Lewis Henry Moran Lectures in Octo-ber 2011, markin the fifieth anniversary o the series, which was conceivedin 1961 by Bernard Cohn, then chair o the Department o Anthropoloy andSocioloy at the University o Rochester. A ounder o modern cultural an-thropoloy, Lewis Henry Moran (1818–81) was one o Rochester’s most a-mous intellectual fiures and a patron o the University o Rochester. He lefa substantial bequest to the university or the oundin o a women’s collee.

Te first three sets o lectures commemorated Moran’s nineteenth-century contributions to the study o kinship (Meyer Fortes, 1963), na-tive North Americans (Fred Egan, 1964), and comparative civilizations(Robert M. Adams, 1965). Marisol de la Cadena’s lecture, as well as lecturesin the subsequent two years iven respectively by Janet Carsten and Peter

van der Veer, addressed the topics o the oriinal three lectures rom the per-spective o anthropoloy in the twenty-first century. Te lecture series nowincludes an evenin public lecture ollowed by a day-lon workshop in which

a draf o the planned monoraph is discussed by members o the Depart-ment o Anthropoloy and by commentators invited from other institu-tions. Te ormal discussants who participated in the workshop devoted tode la Cadena’s manuscript were María Luones rom the University o Bin-hamton; Paul Nadasdy from Cornell University; Sinclair Tomson fromNew York University; and Janet Berlo, Tomas Gibson, and Daniel Reich-man rom the University o Rochester.

De la Cadena’s work marks an important milestone in the history o both

the Moran lecture series and ethnoraphic practice. Her book is based on

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

13/29

xii F O R E W O R D

fieldwork in the Peruvian Andes with two renowned healers (and muchmore), Mariano urpo and his son, Nazario urpo. Trouh her ethno-raphic co-labor with the urpos, de la Cadena traces chanes in the politicso indienous people in Peru, rom 1950s liberalism and socialism to the neo-

liberal multiculturalism o the 2000s. Mariano urpo was a key participantin the Peruvian land reorm movement, which in the 1960s ended a systemo debt peonae under which native people were essentially bound to thehacienda on which they were born. Decades later, Nazario urpo worked asan Andean shaman leadin roups o international tourists in Cuzco; he wasalso invited to work as a consultant on the Quechua exhibit at the NationalMuseum o the American Indian in Washinton, D.C.

De la Cadena’s work extends and critically transorms the leacy o Lewis

Henry Moran, whose landmark contributions to anthropoloy were made possible by ethnoraphic collaboration with Native American intellectu-als, particularly Ely S. Parker, a member o the onawanda Branch o theSeneca, whom Moran met while browsin in an Albany bookstore in 1844.Parker was in Albany to convince New York lawmakers that Seneca land hadbeen illeally sold to representatives o the Oden Land Company underthe reaty o Buffalo Creek. Beinnin with this chance encounter, Mor-an had a lifelon collaboration with Parker, who became Moran’s prin-

cipal source o inormation about the Iroquois. Moran dedicated his firstmajor work, Te League o the Iroquois (1851), to Parker as “the ruit o our

joint researches.”Te urpos talked about their experiences, especially their interactions

with earth-beins, in ways that many people, includin powerful Peruvian politicians, are not inclined to take seriously. Trouh the urpos’ stories—

and recursive consideration o the terms (in all senses o the word) or tell-in their stories—de la Cadena reflects on issues o paramount concern to

current anthropoloy, from the meanins o indieneity in the context omulticulturalism to the contested aency o nonhumans and material thins.Moreover, this book questions the basic premise and promise o ethnora-

phy—namely, to translate between lifeworlds that, althouh different anddistinct, remain partially and asymmetrically connected. What are the oppor-tunities and imponderables, the risks and rewards, that inhere in the work otranslation across epistemic and heemonic divides?

One o de la Cadena’s central claims in the present work is that the exis-

tence o alternative modes o bein in the world should neither be dismissed

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

14/29

F O R E W O R D xiii

as superstition nor celebrated as a diversity o cultural belies. Rather thanthinkin o cultural diversity as the rane o ways that different humanroups understand a shared natural world, we should rethink difference inontoloical terms: how do shared modes o human understandin interpret

fundamentally different, yet always entanled, worlds? Tese intellectualconcerns, which are central to anthropoloy and humanism in eneral, takeon increasinly practical importance in the context o contemporary poli-tics. As in Moran’s time, the expansion o extractive industries like mininthreatens the lives o native peoples throuhout the Americas. Te capacityto define and imaine the sensible world in terms besides those o Nature

partitioned from Humanity has therefore become a crucial instrument ostrugle. By revealin the ontoloical dimensions o contemporary politics

that shape museum exhibitions in the United States as well as public demon-strations in Peru, de la Cadena ives us a compellin example o how anthro-

poloy can promote reconition that there miht be more than one strugleoin on. Her co-labor with Mariano and Nazario urpo yields a cosmo-

political vision that prefiures the possibility o respectful dialoue amondiverent worlds.

Robert J. Foster | Daniel R. Reichman

C O D I R E C T O R S Lewis Henry Moran Lecture Series

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

15/29

Nazario’s happiness April 2007—a few months before he died.

(Photographs are by the author unless otherwise indicated.)

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

16/29

P R E F A C E END ING TH IS BOOK

WITHOUT NAZAR IO TURPO

Te book that follows this preface was composed throuh a series o con- versations I had with Nazario urpo, and his ather, Mariano, both Andean peasants and much more. I met them in January 2002, and afer Mariano’s

death two years later, Nazario and I continued workin toether and even-tually became close riends. On July 9, 2007, Nazario died in a traffic acci-dent. He was commutin rom his villae, Pacchanta, to the city o Cuzco,

where he worked as an “Andean shaman” or a tourism aency. He liked the

job a lot, he had told me; he was a wae earner or the first time in his lie,makin an averae o $400 a month—perhaps a bit more, considerin thetips and ifs he received rom people who started a relationship with him astourists and ended up as riends. His job had chaned his lie, and not onlybecause Andean shamanism is a new colloquial cateory in Cuzco (createdby the converence o local anthropoloy, tourism, and New Ae practices)and thereore also a new potential subject position or some indienous indi-

viduals. It made him very happy, he said, to be able to buy medicine easily

or his wie’s le, which was rheumatic because o the constant, bitin coldin Pacchanta, which is more than 4,000 meters above sea level. o be able tobuy and eat rice, noodles, and ruit instead o potatoes, the daily (and only)bread at that altitude; and to purchase books, notebooks, and pencils or hisrandson, José Hernán (a charmin boy, who was twelve years old when Ilast saw him, immediately afer Nazario’s death)—that made him eel ood.

On many counts, Nazario was livin an exceptional lie or an indienousAndean man. His labor was crucial to the benefits that tourism enerated in

the reion, and the lion’s share o the profits rom his work went to the owner

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

17/29

xvi P R E F A C E

o the aency that hired him. Even so, Nazario’s takins were better than the vanishinly small income people in Pacchanta (and similar villaes) et rom

sellin alpaca and sheep’s wool or the international market at ever-decreasinlocal prices. Also unlike his ellow villaers (common Indians to Cuzqueñourbanites), Nazario was a well-known individual. When he died, I ot a flurryo e-mail messaes from people in Cuzco and from the many friends andacquaintances he had in the United States. Some o them wrote obituaries.

Illustratin the power o lobalization to connect what is thouht to be dis-connected, an obituary commemoratin Nazario’s lie appeared in the Wash-ington Post a month afer he died (Krebs 2007); that same day, there was a

post about his death in Harper’s blo (Horton 2007). I also wrote somethinakin to an obituary and sent it to several riends o mine to share my sadness.Parts o what I wrote appeared in a newspaper in Lima (Huilca 2007), and amonthly lef-leanin political newspaper called Lucha Indígena published the

whole two paes (de la Cadena 2007). I want to introduce this ethnoraphic

work with that piece, to honor Nazario’s memory and to conjure up his pres-

Nazario and Mariano saying good-bye. January 2003. Nazario’s job

as an Andean shaman had recently begun.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

18/29

P R E F A C E xvii

ence into the book he co-labored with me. I had thouht we would write thebook toether; it saddens me that we did not. Here is what I wrote when Na-zario died; it is my way o introducin Nazario and his ather to you.

N A Z A R I O T U R P O , I N D I G E N O U S A N D

C O S M O P O L I T A N , I S D E A D

On July 9th [2007], there was a traffic accident in Saylla, a small town near

the city of Cuzco. A minibus crashed; so far sixteen bodies have been found.

A friend of mine was among them; he was very well known in the region,

and was admired by people in several foreign countries. He was known as a

“chamán” in the city of Cuzco, and as a curandero or yachaq (something like

a curer of ills) in the countryside. My friend’s name was Nazario Turpo. He

spoke Quechua, could write a little Spanish although he hardly spoke it, and

would have been considered an extraordinary person anywhere in the world.

He was exceptional in the Andes, because unlike other peasants like him, life

was being gracious with him—it even seemed as if his grandchildren’s future

could change, and be somewhat less harsh than their present. The most out-

standing part of it all was that he was well known—a historically remarkable

feature for an Andean herder of alpacas and sheep. The Washington Post had

published a long piece about him in August 2003. Around the same time, Ca-

retas [a Lima- based magazine that circulates nationwide] had a story about

Nazario, including several pictures of him in its glossy pages. By then he had

already traveled several times to Washington, D.C., where he was a curator

of the Andean exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American

Indian (NMAI). An indigenous yachaq mingling with museum specialists in

Washington, D.C., was certainly a news-making event in Peru.

Nazario took real pleasure relating to what, to him, was not only new but

immensely unexpected as well. Complexly indigenous and cosmopolitan, he

was comfortable learning, and completely at home showing his total lack of

awareness of things like the inside of planes, the idea of big chain hotels (and

their interiors!), subways, golf carts, even men’s bathrooms. He asked ques-

tions whenever he had doubts—just as when I or other visitors asked ques-

tions when learning how to find our way around his village, he said. (Weren’t

we always asking how to walk uphill, find drinking water, hold a llama by the

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

19/29

xviii P R E F A C E

neck and avoid its spit, wade a torrential creek—even how to chew coca

leaves? It was the same, wasn’t it?) Back at home, his travels provided stories

that he told Liberata, his wife, and José Hernán, his twelve-year-old grand-

son (who I suspect was his favorite). His journeys abroad also intensified his

appeal to tourists, and what had started as an occasional gig with a creative

tourism entrepreneur gradually became a regular job. Relatively soon, and

through New Age networks of meaning, money, and action, Nazario saw his

ritual practices translated into what began to be known as Andean shaman-

ism. During the peak tourist season, from May to August, his job became

almost full time, as it required commuting from the countryside to the city at

least four times a month, for five days at a time. When he died, he was on one

of these commutes, half an hour away from his final destination: the tourism

agency where the following day he would meet a tourist group and travel with

them to Machu Picchu, that South American Mecca for foreign visitors. Those

of us who travel that route are aware of the dangers that haunt it; yet none of

us imagined that this exceptional guy would die so common a death in the

Andes, where, as a result of a state policy that has abandoned areas deemed

remote, and a biopolitics of neglect, buses and roads are precarious at best,

and frequently fatal.

Nazario was the eldest son of Mariano Turpo, another exceptional human

being, who had died of old age three years earlier. They all lived in Pac-

chanta—a village inscribed in state records as a “peasant community” where

people earn their living by selling (by the pound and for US pennies) the meat

and wool of the alpacas, llamas, and sheep that they rear. Pacchanta is in

the cordillera of Ausangate, an impressive conglomeration of snow-covered

peaks where an annual pilgrimage to the shrine of the Lord of Coyllur Rit’i

takes place. Local public opinion has it that around 60,000 people attend the

event every year; I know they come from all over Peru and different parts of

the world. The zone is also known locally as the area where Ausangate, an

earth-being—and a mountain that on clear days can be seen from Cuzco, the

city—exerts its power and influence. In the ’60s, leftist politicians visited Pac-

chanta with relative frequency, lured by Mariano Turpo’s skillful confrontation

against the landowner of the largest wool- producing hacienda in Cuzco—

it was called Lauramarca. Mariano was a partner in struggle with nationally

famous unionists like Emiliano Huamantica, and socialist lawyers like Laura

Caller. Back then, the journey usually took two days. It started with a car ride

from the city of Cuzco to the town closest to Pacchanta (Ocongate), and then

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

20/29

P R E F A C E xix

required a combination of walking and horseback riding. Changes in the world

order have affected even this remote order of things: currently tourists arrive

[in Pacchanta] from the city in only five hours, ready to trek the paths that cut

through imposing mountains, lagoons of never-before-seen tones of blue and

green, and a silence interrupted only by the sound of the wind and the distant

hoofs of beautiful wild vicunas. This idyllic scenery is not the result of con-

servationist policies, but rather of a state politics of abandonment, which is

at times shamefully explicit. But the new visitors do not seek the revolution

like the previous ones; until his death, they were lured by Nazario’s complex

ability, which he had learned from his father, to relate with the earth-beings

that compose what we call the surrounding landscape.

I was lured to Pacchanta by Mariano’s knowledge. If tourists learned about

Nazario through networks of spiritualism generally identified as New Age, my

networks were those of peasant politics, development NGOs, and anthro-

pology. Mariano had built and nurtured complex connections during his years

as a local organizer, and though the individuals changed as people grew old,

and politics and the economy changed too, the networks survived. When I ar-

rived in Pacchanta, it was not politics that wove those networks, but tourism.

They continued to connect the village to Cuzco and Lima—but this time links

also existed with Washington, D.C., New York, New Mexico . . . and through

me, in California. As they had been from the beginning, Cuzco anthropologists

were prominent in the networks, which did not surprise me given their hege-

monic (and almost exclusive) interest in “Andean culture.”

I admired Mariano profoundly. He was very strong, extremely courageous,

and relentlessly analytical; although he did not intend it, I constantly felt

dwarfed by him. An exceptionally talented human being, it was, without a

doubt, an honor to have met him. His cumulative actions—physically con-

fronting the largest Cuzco landowner, and then following up this confrontation

legally and politically through union organizing among Quechua speakers—

had been crucial at effecting the Law of Agrarian Reform in 1969, one of the

most important state-sponsored transformations Peru underwent in the last

century. Mariano was undoubtedly a history maker. Yet, in contradiction with

the far-reaching networks he built, the national public sphere—leftist and con-

servative—had always ignored this local chapter of Peruvian history. As a

monolingual Quechua speaker, Mariano’s deeds could amount only to local

stories—if that. And of course he had stories to tell; those were the ones I had

gone after and listened to for many months.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

21/29

xx P R E F A C E

His community had chosen him as its leader, among other things, be-

cause he could speak well— allinta rimay , in Quechua—and because he was a

yachaq—a knower, also in Quechua. This resulted in his unmatched ability to

relate assertively with his surroundings, which included powerful beings of all

sorts, human and other-than-human. Mariano used to describe his activities

as fighting for freedom—he said the word in Spanish, libertad —against the

landowner, who he qualified as munayniyuq, someone whose will expresses

orders that are beyond question and reason. Being a yachaq, Mariano had the

talent to negotiate with power, which in his world emerged both from the let-

tered city and from what we know as nature; the hacendado also drew power

from both but was also firmly anchored in the first. To negotiate with all aspects

of power, and enable his own negotiations with the lettered world, Mariano

built alliances; his networks ramified unpredictably, even to eventually include

someone like me, a cross-continental connection between the University of

California, Davis, and Pacchanta—and, of course, to Lima and Cuzco. The

networks also cut across local social distances and included individuals who

did not identify as indigenous in the nearby villages, the hacienda, and the sur-

rounding towns. Reading and writing were crucial assets that Mariano strived

to include—and he also found them at home. Mariano Chillihuani—Nazario’s

godfather—could read and write, and was perhaps Mariano Turpo’s closest

collaborator; his puriq masi , “companion in walking” in Quechua. The two

Marianos traveled to Lima and Cuzco, talked to lawyers, hacendados, politi-

cians, state officials, and, according to many, they even had an audience with

Peruvian President Fernando Belaúnde. “They always walked together,” Na-

zario recounted, “my father talked, my padrino read and wrote.” That means

that together they could talk, read, and write.

Mariano and Nazario’s knowledge was inseparable from their practice;

it was know- how, which was also simultaneously political and ethical. And

not infrequently, these practices appeared as obligations with humans and

other-than-humans: the failure to fulfill certain actions could have conse-

quences beyond the practitioner’s control. Their political experience enabled

them to communicate with and participate in modern institutions; their ethical

know-how worked locally, and traveled awkwardly because not many beyond

Ausangate’s reach can understand that humans can have obligations to what

they see as mountains. Some of the obligations are satisfied through what the

anthropology of the Andes knows as “ritual offerings”; the most charismatic

and currently popular among tourists are despachos (from the Spanish verb

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

22/29

P R E F A C E xxi

despachar , to send or dispatch). These are small packets containing different

goods, depending on the specific circumstance of the despacho and what

it wants to accomplish. Mariano and Nazario were well known for the effec-

tiveness of their dispatches, the way they offered them, what they contained,

the places they sent the offering from, and the words they used to do so.

The popularity of despachos even reached former President Alejandro Toledo,

who, in indigenist rapture, inaugurated his term as president with this ritual

in Machu Picchu. Nazario Turpo was among the five or six “authentic indige-

nous experts” invited to the ceremony. The invitation had reached Pacchanta

through Mariano’s networks, which as they had in the past, included state offi-

cials. This was 2001, however; multiculturalism was the name of the neoliberal

game, tourism its booming industry, and “Andean Culture” one of its uniquely

commodifiable attractions. Mariano was too old for the journey, so Nazario

went instead. “I did not perform the despacho,” he told me, “I cured Toledo’s

knee. Remember how he was limping? After I cured him he did not limp any-

more.” He did not explain how he did it—and I did not ask. I imagine that he did

Nazario’s death was covered by La República, one of the most important

nationwide newspapers; the title means “The Altomisayoq Who Touched

Heaven,” and the piece contributed to Nazario’s prominence as a public shaman.

It also featured an excerpt of my writing—the obituary that I also present here.

The smaller photographs, taken at the inauguration of National Museum of

the American Indian, in Washington, D.C., are mine.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

23/29

xxii P R E F A C E

what he knew, like when a U.S. traveler fell when she was climbing a small hill

near Nazario’s house. After carefully lifting her, he wrapped her body—actu-

ally bandaged it—in a blanket to prevent her bones from moving and hurting

even more. Once in the bus, he took care of her all the way from Pacchanta to

the city. I met the woman during what would be my last sojourn with Nazario

in his village; she assured me that Nazario’s treatment had helped. That she

went back to the remoteness of Pacchanta was proof to me that she believed

what she said.

Nazario was aware (indeed!) that, depending on the circumstances, many

knowledges, things, and practices were more effective than what he knew and

did. Once I asked him why he was not able to cure José Hernán, his grandson,

who was suffering from stomachaches. He looked at me, and with a you’ve-

got-to-be-kidding-me smile said, Because up here I do not have antibiotics.

But learning, in this case about antibiotics, did not replace Nazario’s healing

practices; rather, it extended his knowledge: knowing about antibiotics meant

to know more, not to know better. Following him, I learned about the complex

territorial and subjective geometry that his practices cut across; their bound-

aries are not single or simple. His practices indeed may be incommensurable

with the “extraneous” forms of doing and thinking that they have cohabited

and negotiated with for more than 500 years. Yet, most complexly, Nazario’s

practices—and those of others like him—variously relate to these “different”

forms of doing without shedding their own—or as I said above, thinking that

“now they know better.” An anecdote may provide a concrete illustration. As

part of the inaugural ceremonies for the NMAI in Washington, D.C., the indige-

nous curators were invited to a panel at the World Bank, and Nazario Turpo

was of course among them. Nazario gave his presentation in Quechua and

requested funding from the Bank to build irrigation canals in his village. The

water was drying out, he explained, “due to the increasing amount of airplanes

that fly over Ausangate, making him mad and turning him black.” I do not know

who told him what, but later at the hotel he explained to me: Now I know that

these people call this that the earth is heating up; that is how I will explain it

to them next time. And half seriously, half jokingly we talked about how, after

all, in Spanish to heat up, calentarse, can also mean to be mad. In the end,

I was sure that Nazario’s will to understand “global warming” was far more

capacious than that of the World Bank officials, who could not even begin to

fathom taking Ausangate’s rage seriously. Nazario certainly outdid them in

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

24/29

P R E F A C E xxiii

complexity; he had the ability to visit many worlds, and through them offer

his as well. Today all those worlds are mourning because Nazario is no more.

Nazario was not only a co-laborer in this ethnoraphic work. He was a veryspecial riend; we shared pleasurable and strenuous walks and talks between2002 and 2007. We communicated across obvious boundaries o lanuae,culture, place, and subjectivity. We enjoyed our times toether—thorouhly.

We lauhed toether and were scared toether; we areed and disareed witheach other; and we also became impatient with each other when we ailed tocommunicate, which usually occurred when I insisted on understandin in

my own terms. I have already told you enough about suerte—you cannot knowwhat it is, how many times do I have to explain suerte to you? You do not under-

stand, and I am repeating, and repeating , he told me the last December I sawhim, in 2006. And I pleaded: “Just one more time, I will understand Nazario,I promise.” But o course I did not understand, and I cannot remember i herepeated the explanation or not. Tis is what Nazario had said: Apu Ausan-

gate, Wayna Ausangate, Bernabel Ausangate, Guerra Ganador, Apu Qullqi

Cruz, you who have gold and silver. Give us strength or these comments, these

things we are talking about, so that we have a good conversation. Give us ideas, give us thoughts, give us suerte now, in the place called Cuzco, in the place called Peru. Ten he looked at me and said, I you want you can now chew coca, i you

do not want to, do not do it . But I intuited that it would be better, I would havesuerte i I did it, and I wanted to explore that intuition. Suerte is a Spanish

word whose equivalent in Enlish is luck, and I was not askin or a linuis-tic translation—I do not need it. Rather, I wanted to understand the ways in

which Nazario paired suerte (was it luck?), thinkin, and the entities that he

reerred to as Apu, which are also mountains, and whose names he had in- voked beore startin our conversation. Amon tirakuna, or earth-beins—a

composite noun made o tierra, the Spanish word or “earth,” and pluralized with the Quechua suffix kuna—Apu ( apukuna is the plural) can be the most powerul in the Andes. Nazario’s reusal to explain aain was one o many

sinificant ethnoraphic moments—those moments in our conversation thatslowed down my thouhts as they revealed the limits o my understandinin the complex eometry o our conversations. In this eometry, tirakuna

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

25/29

xxiv P R E F A C E

are other-than-human beins who participate in the lives o those who callthemselves runakuna, people (usually monolinual Quechua speakers) wholike Mariano and Nazario, also actively partake in modern institutions thatcannot know, let alone reconize, tirakuna.

My relationship with the urpo amily started with an archive—a collec-tion o written documents that Mariano had kept as part o an event thatlasted for decades, which he explained as the fiht he enaed in aainst alandowner and or liberty. When we worked with the documents, Mariano

would always start our interaction by openin an old plastic ba where hekept his coca leaves and rabbin a bunch. Afer invitin me to do the samethin, he would search in his bunch or three or our o the best coca leaves,careully straihten them out, an them like a hand o cards, and then hold

them in ront o his mouth and blow on them toward Ausanate and its rela-

The author and Nazario say goodbye in the town of Ocongate

as Nazario gets ready to take the bus to the city of Cuzco where

a group of tourists awaits him. July 2004. Photograph by Steve

Boucher. Used by permission.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

26/29

P R E F A C E xxv

tives—the hihest mountains and most important earth-beins surround-in us. Tis presentation o coca leaves is known as k’intu; runakuna offerit amon themselves and to earth-beins on social occasions, bi or small,everyday or extraordinary. Offerin k’intu to earth-beins, Mariano was

doin what Nazario had also done when I asked about suerte (and he reusedto explain): they were welcomin tirakuna to participate in our conversa-tions. And they were doin so hopin or ood questions and ood answers,or ood rememberin, and or a ood relationship between us and all thoseinvolved in the conversation. Nazario’s reusal to explain suerte sent me backto this moment, or Mariano’s practice sugested a relationship between thetwo o us, the written documents, and the earth-beins. All o us—includinthe documents and tirakuna—had different, even incommensurable, rela-

tions with each other, yet throuh Mariano, we could enae in conversation.Mariano’s capacity to mediate hihlihted an interestin eature o our re-lationship. On the one hand, he could interact with Ausanate and the othertirakuna who could influence our conversation, and he had also learned, atleast to an extent, the lanuae o the documents. On the other hand, I couldread the documents and access them directly; I could access tirakuna onlythrouh Mariano and Nazario and perhaps other runakuna. With my usualepistemic tools, I could not know Ausanate—not even i I ot lucky.

Nazario’s refusal “to explain aain” hihlihts the inevitable, thick, andactive mediation o translation in our relationship—and it worked both

ways, o course. I could not but translate, move his ideas to my analytic se-mantics, and whatever I ended up with would not, isomorphically, be identi-cal to what he had said or mean what he meant. Tereore, he had already toldme enouh about suerte to allow me to et as much as I could. Our worlds

were not necessarily commensurable, but this did not mean we could notcommunicate. Indeed, we could, insoar as I accepted that I was oin to leave

somethin behind, as with any translation—or even better, that our mutualunderstandin was also oin to be ull o aps that would be different oreach o us, and would constantly show up, interruptin but not preventinour communication. Borrowin a notion rom Marilyn Strathern, ours wasa “partially connected” conversation (2004). Later in the book I will explainhow I use this concept. For now, I will just say that while our interactionsormed an effective circuit, our communication did not depend on sharinsinle, cleanly identical notions—theirs, mine, or a third new one. We shared

conversations across different onto-epistemic ormations; my riends’ expla-

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

27/29

xxvi P R E F A C E

nations extended my understandin, and mine extended theirs, but there

was a lot that exceeded our rasp—mutually so. And thus, while inflectinthe conversation, the urpos’ terms did not become mine, nor mine theirs.I translated them into what I could understand, and this understandin wasull o the aps o what I did not et. It worked the same way on Mariano andNazario’s side; they understood my work with intermittencies. And neithero us was necessarily aware o what or when those intermittencies were. Tey

were part o our relationship that, nevertheless, was one o communicationand learnin. For Nazario and Mariano such partial connections were not a

novel experience; their lives were made with them. I will not dwell on this

A cross marks the place of the traffic accident where Nazario

Turpo died. September 2009.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

28/29

P R E F A C E xxvii

now, or this historical story o partial connections is what the whole book isabout. For me, however, the realization that a “appy” circuit o connections

was what I would write fom (and not only about ) was an important insiht.It made me think back to Walter Benjamin’s (1968) sugestion o makin the

lanuae o the oriinal inflect the lanuae o the translation. But o courseI had to tweak this idea too, or ollowin Nazario’s reusal to explain more,I could not access the oriinal—or rather there was no oriinal outside oour conversations: their texts and mine were coconstituted in practice, andthouh they were “only” partially connected, they were also inseparable. Teconversation was ours, and neither a purified “them” (or him) and “us” (or I)could result rom it. Te limits o what each o us could learn rom the other

were already present in what the other revealed in each o us.

Rather than chapters, I have divided this book into stories because I com- posed it with the accounts Mariano and Nazario told me. Story 1 presents

the conceptual, analytical, and empirical conditions o my co-labor with theurpos; I intend it to take the place o the usual introduction. Te rest othe book is divided into two sections o three stories each, both precededby a correspondin interlude. Te first one introduces Mariano urpo; his

political pursuits with humans and earth-beins are the matter o the fol-lowin three stories. Te second interlude presents Nazario, whose activities

as “Andean shaman” and local thinker occupy the rest o the book. Ausan-ate, the earth-bein that is also a mountain, occupies a prominent place inour joint endeavor or it made our conversations possible in its “more thanone less than many” (see Haraway 1991 and Strathern 2004) ways o bein.

-

8/20/2019 Earth Beings by Marisol de la Cadena

29/29

The road to Mariano’s house. January 2002.