Early Islamic Theological and Juristic Terminology Kitāb al-Ḥudūd fi 'l-uṣūl, by Ibn Fūrak...

-

Upload

matt-cascio -

Category

Documents

-

view

129 -

download

19

description

Transcript of Early Islamic Theological and Juristic Terminology Kitāb al-Ḥudūd fi 'l-uṣūl, by Ibn Fūrak...

Early Islamic Theological and Juristic Terminology: "Kitāb al-Ḥudūd fi 'l-uṣūl," by Ibn FūrakAuthor(s): M. A. S. Abdel HaleemReviewed work(s):Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 54,No. 1 (1991), pp. 5-41Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African StudiesStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/617311 .Accessed: 30/04/2012 09:05

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Cambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies are collaborating with JSTOR todigitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University ofLondon.

http://www.jstor.org

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY: KITAB AL-HUDUD FI 'L-USUL,

BY IBN FURAK

By M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

(PLATES I-IV)

In our very first grammar lesson at the primary school of al-Azhar we were introduced to al-mabddi' al-'ashara, 'The Ten Introductory Aspects'' with which the textbook began. We learnt then that these ten aspects, as handed down by the ancient tradition, were points to be considered when embarking on eachfann (branch of knowledge). 'They said: it is incumbent upon him who sets out to expound a book to deal in the introduction with certain things before he begins with the intended subject matter'.2 Such was the importance of 'The Ten' in traditional Islamic education that they were formulated in two lines of verse, in more than one version, to aid the memory of learners. One version runs:

&^ _ > , . - lr ^ J ,l ; , !

b t b I} 4 ^ 1 a ,;

_ y, .

1, _ :, -- 1 5

1. The first mabda' is al-hadd, the definition of a given subject or 'ilni. The arrangement of the other mabadi' follows the restriction of the metre and rhyme adopted, but they include:

2. al-ism, the name of the particular 'ilm; 3. al-mawduf', the subject matter of the 'ilm; 4. al-thamara, the benefit obtained from learning it; 5. al-masa'il, the issues with which it deals; 6. al-istimddd, the sources of such 'iln; 7. al-wddi', the founder of the 'ilm; 8. nisbatuh, its relation to other subjects; 9. al-rutba, its status among other subjects;

10. hukm al-sharifiTh, how the shar'a views the learning and application of such 'ilm.

The mabddi' were seen as a sound starting point which from the outset gave the reader a clear picture of the subject he was about to study and its context. This was considered to be an essential part of al-anhai' al-ta'ltmiyya '1- mustahsana ft turuq al-ta'lim-' approaches preferred in the method of educa- tion '3 in traditional Islamic education.

Lexically, hadd (pl. huduid) means a limit or boundary of a land or territory; technically, it has many meanings (s.v. El), the earliest of which is that used in the Qur'an in the plural for the restrictive ordinance of Allah which should not be transgressed (e.g. 2: 229; 65: 1). Infiqh, huduid are the fixed penalties specified for such forbidden acts as theft, adultery, etc.; the works offiqh have a chapter

' al-Tuhfa 'l-saniyya (a commentary on the condensed al-Ajrimiyya by Ibn Ajurrum of Sanhaja (dc 723/1323) by M. M. 'Abdel Hamid, Cairo. Many editions. 2 Kashshdf istildhat al-funun by M. A. F. al-Tahanawl (Calcutta, 1862), 10.

3 ibid., 11.

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

on al-hudud wa-'l-jindyat or al-hudiud wa-'l-diyat. There are also separate works on these huduid, of which M. M. al-Tihrani lists 19 in his al-Dhdri'a ild-tasdanf al- sh'a (vol. 6, nos. 1078-96), but this does not concern us here. In logic, hadd is the term of a syllogism, of which there are three, asghar, wasat and akbar, which are also of no immediate concern.

In kaldm and philosophy, hadd is a technical term meaning 'definition'. In this connexion we have hadd haqiqf, which defines the essence of a thing, and hadd lafzT, which defines the meaning of a word; there are also al-hadd al-kdmil, the perfect definition of a thing consisting of its proximate genus and differentia; and al-hadd al-ndqis, the imperfect definition of a thing referring merely to its differentia, or to the differentia and the remote genus. Brockelmann (S, III, 898) gives a list of works in which huduid is used in the various meanings given above; thus we have Huduid al-'alam, al-Hudud wa-'l-ahkdm, Hudufd al-amrad, Huduid al-ashya' wa-rusumha, and al-Hudfidfi 'l-usiul, by Ibn Furak. It is al-hudud in the sense of this last title, i.e. the definition of technical terms, that concerns us here.

As the various subjects of study developed, they acquired their own mabddi' 'ashara and technical language, elaborated by scholars in the field, ahl al- ikhtisds. In the context of such a technical language, a term would have its specific meaning, usually peculiar to ahl al-ikhtisas, known in Arabic as al- haqTqa 'l-'urfiyya 'l-khdssa.4 This usually bore some relation to the lexical meaning al-haqlqa 'l-lughawiyya but was distinct from it. In the works offiqh we find the lexical meaning followed by the technical one,5 but in usdl al-fiqh, when words are used in their technical context ma'dnin 'urfiyya shar'iyya, they must be understood in their technical rather than their lexical sense.6 As the various Islamic branches of knowledge evolved their own technical terminology, they sometimes shared the same lexical items; while these normally bore some relation to the lexical meaning, they nevertheless had a distinct technical meaning in each branch of knowledge, unknown perhaps even to scholars not initiated in the particular branch concerned.

This situation made the definition of terms (hudud) increasingly important and eventually prompted authors to devote special works to this task. In the introduction to his Mafatlh al-'ulum ('Keys to the various branches of knowledge'), al-KhwarizmT (d. 387/997-a contemporary of Ibn Furak) makes a significant observation that not only tells us something about the general situation at the time but shows that, for example, the lexical item raj'a had four different technical meanings:7

J- ouJl YjL DJ i>- e SJ\-J S5-. Z\wl JLc Q? J YJ oJL o1 JLJ

jt iy^>\ JULPj c) L e el28 A . \Jl-, L L SLJ?l <Skl\J J j . IpilP je u*WL

.*Jl JL; <j% J P 6 ;9W ^L ^ c-\s \

It is thus not surprising that defining the meaning of technical terms became first, an important task for writers, and second, one of the traditional educa- tional methods of al-anha' al-ta'lTmiyya, as the above quoted statement by al- Tahanawi (d. 1185/1771), himself an important author on technical terms, makes clear.

4 e.g. M. b. 'All al-Shawkani, Irshad al-fuhul (Cairo, 1930), 19. 5 e.g. on the definition of salah and sawm see A. al-Harrli, al-Fiqh 'ala 'l-madhdhib al-arba'a, I

(Cairo, n.d.), 175 and 541. 6 A. Khallaf, 'Ilm usul al-fiqh (Cairo, 1977), 142-3. 7 Mafdtih al-'ulum (Leiden, 1895), 2-3.

6

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

The development of technical language in Arabic first made itself evident in the treatment of religious subjects, grammar, and philosophy, with terms offiqh and hadith naturally appearing first. Early fuqaha', of the tabi'un, teachers of Abui Hanifa for instance, talked of zawdj, talaq, zihdr, etc., and studied such issues as murtakib al-kabTra, Tman, nifaq, baghy, and khurij at the time of al- Hasan al-Basri (d. 110/728) and his generation, not to speak of the discussions on salah, zakdh, hajj and jihad which were part of Islamic daily life from the beginning. Shafi''s Risala, displays for example, various features characteristic of philosophical thinking, including the definition of technical terms and classification, etc.8 Scholars of hadfth, in developing their rules of authentication and classification of ahaddth according to status-which were taken up by historians and rdwTs of language and literature 9-worked with their own set of technical terms.

Arabic grammar was also one of the early subjects to develop a specific complex of technical terms, as is witnessed in the Kitdb of Sibawayhi (d. 180/ 796). Philosophical subjects, which were introduced into Arabic via translation after the emergence and development of the religious subjects just mentioned, came equipped with their own technical language; the definition of technical terms was an already established feature of these subjects, as was the writing of separate treatises on philosophical terms, as we shall see below.

It is not intended in this introduction to draw up a definitive chronology for the separate works on hudud-a task which will probably have to wait for the appearance of more early Arabic manuscripts. The aim here is to consider some important works on the definition of technical terms in the fields of philosophy and religion, as well as a number of general works that cover a variety of subjects, in order to illustrate the importance and scope of writing on hudud and to establish the place of Ibn Fiurak's work in this context.

I. Philosophical terms As has already been said, philosophical works entered into Arabic with their

own highly technical language. The difficult task for translators and philos- ophers was to find or to coin Arabic equivalents. It was to the credit of the early translators that they tried to adapt the Arabic language to express philosophical concepts. Thus al-KindT (d. 252/866) is known to have revived some disused Arabic words to convey technical meanings, such as al-ays 'existence' and al- lays' non-existence ', from which he drew such derivations as ta'yls al-aysdt 'an lays.'? As far as our present state of knowledge is concerned, the following are among the earliest extant works:

1. Risalat al-hudud, by Jabir b. Hayyan (d. about 200/815), consisting of 92 terms." Doubts have been expressed about the attribution and dating of the corpus of works of Jabir (s.v. El). A. al-A'sam, however, using a rare manuscript (see al-Mustalah, 133), older than that which P. Kraus used in his edition, is convinced that his manuscript shows the certainty of the attribution of Risalat al-hudud to Jabir (ibid., 153) beyond any doubt (p. 12).

2. Risalafi-huduid al-ashyd'wa-rusfimiha, by Abiu Yuisuf Ya'qiub b. Ishaq al- Kindi (d. 252/866), containing some hundred terms in logic, mathe-

8 M. 'Abd al-Raziq: TamhTd li-tdrTkh al-falsafa 'l-isldmiyya (Cairo, 1979), 7. 9 Ahmad Shakir, al-Bd'ith al-hathTth (Cairo, 1979), 7. 10 M. A. Abu Rida, Rasa'il al-kindT 'l-falsafiyya (Cairo, 1950), 19. (It should be noted that Abu

Rida does not agree with Massignon that al-Kindi died in 246 (ibid., 5.) " Mukhtdr rasd'il Jabir Ibn .Hayydn, ed. P. Kraus (Cairo, 1354/1935), 97-114 (under Kitdb al-

Huduid); A. al-A'sam, al-Mustalah al-falsafi 'ind al-'arab (Baghdad, 1985), 163-86.

7

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

matics, metaphysics, ethics, etc.12 This was thought to be probably the earliest dictionary of philosophical terms in Arabic.13

3. Risalat al-hudud wa-'l-rusum, by Ikhwan al-Safa', risala no. 41,'4 contain- ing about 250 mainly philosophical terms, but including some theological terms and thus being the first treatise that combines kalam and philosophical terms.15

4. Risalat al-h.udud, by Ibn STWa'6 (d. 428/1037), containing about 70 terms. 5. Kitdb al-hudufd, by al-Ghazal['7 (d. 505/11 11), containing about 75 terms.

It is significant that all these philosophical works bear the title hudud which is not the case in other subjects. The tradition of writing on philosophical terms had a long history,'8 and has been revived in our own day, as we see in al- Mujam al-falsafi, published by the Arabic Language Academy in Cairo (1963) and Mustalahdt al-Jalsaja, issued by the Supreme Council for Arts and Literature (Cairo, 1964).

II. Religious terms What concerns us here is the terminology related to usul al-fiqh, kaldm and

hadTth, the subjects dealt with by the Ibn Furak in his al-.Hududfi 'l-usul. We shall deal with hadTth first, and then turn to fiqh and kaldm. The question of establishing the authenticity and status of ahddlth gave rise to the science of mustalah al-hacdfth. Although Shafi'i dealt with such questions in his Risala, as did, among others, Muslim (d. 261/874), in the introduction to his Sahih, Tirmidhi (d. 279/892) at the end of his Jdmi', the first author to isolate this subject was Abfu Muhammad al-Ramahurmuzi (d. c. 360/970) in his al- Muhaddith al-fid/il. Numerous works in prose and verse have continued to appear ever since, of which we need only mention the following:

Usul 'ilm al-had[th, by al-Hakim al-Nisabufir (d. 405/0104). al-Ilmi', by al-Qad.i 'Ayyad (d. 44/1149). Muqaddimat Ibn al-Salah, by 'Uthman b. al-Salah (d. 643/1245). al-Ba'ith al-hathTth ild ma'rifat 'uluim al-had[th, by Ibn KathYr (d. 774/1372). Nukhbat al-fikarfi mustalah ahl al-athar, by Ibn Hajar (d. 852/1449).

It should be noted that mustalah al-hadFth is a highly technical subject, treatises on which consist mainly of the definitions of terms and classifications leading to further definitions.

As has already been said, fiqh terminology was the earliest to appear in Islamic studies, and usul al-fiqh terminology found more formal expression in Shafi'i's Risala. Discussion on kalam started in the first century of the Hijra and developed to full maturity in the third and fourth centuries. Yet we do not find separate works on the hudid of usul al-fiqh or kaldm before around the middle of the fourth century. Technical terms were contained in the body of texts written by the main authors in both subjects-Shafi'l and Ash'arl, for instance. It may well be that separate works on terminology in these subjects were written

12 Abui Rida, Rascd'il al-kindi, 19, 165-80; al-A'sam, al-Mustalah, 189-203. In this connexion we should mention al-Farabi's work: Kitdb al-huruf. Other works by him, such as Kitdb al-alfdz al- musta'malafi 'l-mantiq and Ihsa' al-'ulum, are relevant in regard to the definition of terms.

13 Abu Rida, Rasa'il al-kindl, 164. 4 Cairo, 1928, 359--72.

15 H. M. al-Shafi'l (ed'), al-Mubn fi sharh alfdz al-hukdma' wa-'l-mutakallimrn (Cairo, 1983). 16 A. al-A'sam, al-Mustalah, 56-699; 229-263; see also A. M. Goichon, Kitdb al-hudud li Ibn Snad

(Cairo, 1963); A. al-'Abd, in al-hudud fi thaldth rasd'il (Cairo, 1978). 17 al-A'sam, al-Mustalah, 265-301; al-Ghazali, Mi'vdr al-'ilm, ed. H. Sharara (Beirut, 1964),

196-230. 18 See H. M. al-Shafi', al-Mub[n, 31-2.

8

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL ANI JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

but are still to be discovered.'9 The explanation may, in addition, lie in how much of a need was felt for separate compilation, in view of the familiarity in Islamic life offiqh terminology and to a large extent--apart from discussion on qiyas and on al-qawd'id al-usuliyya 'l-lughawiyya-of usul al-fiqh terminology. Nor was the need felt, I am inclined to say, for separate works on technical terms of kalam in the early stages of its development when the majority of its terms were based on Qur'anic vocabulary, before kaldm gradually came to be combined with philosophical concepts and terms. The situation is made clearer by contrast with philosophy, where an acute need for special treatises on technical terms was felt very early. This is demonstrated in the early works, mentioned above, of Jabir b. Hayyan and al-Kindi, Jabir in particular stressing the great importance of the knowledge of hudud.'2 Although early works were written on the gharib of the Qur'an and had[th, and lexical treatises, similar to those on technical terms, were written on separate subjects such as horses, trees and rain,2' which should have acted as a model for writing on kalain and usul terms, the fact that many of the extant early works in this field use the term hudud in their title suggests that the first inspiration for title and format came from the treatises of Jabir, al-Kindi, Ikhwan al-Safa' and Ibn Sina. A brief account of some of the works on kalcdm and usu.l is given below:

1. Kitdb al-zTnah fi 'l-kalimat al-isldmiyya 'l-'arabiyya, by Abu Hatim Ahmad b. Hamdan al-Razi, an Isma'iil author who died in 322/933. The first extant work on kaldm terms, this was considered to be the earliest work on technical terminology after that of al-Kindi.22 It was edited by H. F. Hamdani and published in two volumes in Cairo, A.D. 1957-58. The preface to the first volume states that the book contains about 400 items which are religious terms that occur in the Qur'an and hadUth or were current amongst religious scholars, and that all need to be explained (p. 9). As we are dealing here with terms and their definitions (huduid), it is necessary to describe some of the features of this important early text. Only the second volume is concerned with technical terms. The first contains a general discussion on the superiority of Arabic among 'the four best languages: Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac and Persian' (p. 61), and on Arabic poetry, etc.; the last twenty pages or so deal generally with Islamic names and their meanings. In 229 pages of the second volume the author discusses asmd' alladh al-husnd and 126 pages of the remainder are devoted to other kalim terms. The customary lay-out of books on kalam is not followed here; instead of the usual limited number of sifat relevant to kalam discussions, the author for the greater part deals with ' all the most beautiful names', and there is nothing on prophethood. The format is not that of huduid, or definition, but rather that of encyclopaedic information. Each terms is dealt with under a separate bah; sometimes related terms are grouped together in one explanation and the author cites numerous verses (e.g. bab al-wdlhid al-ahad, Ii, 32-42). The work was clearly not inspired by the philosophical treatises and does not bear the title huduid, or even mustalahdt or ta'rPfut: it is al-zina fi 'l-kalimdt al- isldmiyy '- 'arabiyya, in fact a genre of its own.

2. Kitab al-hududfi 'l-usul, by Abiu Bakr Muhammad b. al-Hasan b. Fuirak (d. 404/1015). The manuscript published here for the first time is to our knowledge the first extant work on huduid proper in religious subjects,

19 ibid., 20. 20 Z. N. Mahmfid, Jiabir ibn .Hay.van (Cairo, 1961), 52. 21 M. M. Omar, Muhddarat fi 'iln al-lugha (Cairo, 1968), 199. 22 H. M. al-Shati'i, al-MubTn, 26.

9

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

the first to be written by a Sunni author-the work just discussed, however one classifies it, being by an Isma'Til Shl'i-and the first to combine terms of kaldm and usul al-fiqh. As will be seen later, kalam for this Sunni author was related more to usul al-fiqh than to philosophy. It should be mentioned here that among current bibliographers and authors only F. Sezgin-who does not mention his source-states that this work was published in Beirut in 1324 A.H. (A.D. 1906).23 We know that another work by Ibn Furak, ' Muqaddima fi nukat min usul al-fiqh ', in Majmu' rasa'ilfi usul al-fiqh (I, 1-14), was published in Beirut in that year, but it is not on huduid and is exclusively concerned with usul al-fiqh. Perhaps the word usul and the name of Ibn Furak on the title page led to the wrong assumption that this was Kitdb al-hudid. But usul in al-Huduid is usul al- din as well as usul al-fiqh, as we shall see later. Given the content of Kitdb al-hudud, it is highly unlikely that anyone would have published it in Beirut in 1906 as being a work on usul al-fiqh. Be that as it may, no evidence has been found to show that Ibn Furak's Kitdb al-hudud was printed in Beirut at any time: Brockelmann, like all the Arab biblio- graphers and authors, is of the opinion that Kitdb al-hudud is still a manuscript.

3. al-.Hudud wa-'l-haqd'iq, by al-Sharif 'Ali b. al-Husayn b. Musa 24 (d. 436/ 1044). This deals solely with kaldm terms but shows that the subject was beginning to tend towards philosophy.25

4. al-Muqaddimafi 'l-kaladm, by Abiu Ja'far al-Tusi (d. 460/1067).26 5. al-.Hudid wa-'l haqd'iq, by Sharaf al-Din Sa'id al-Barnid al-Abi (sixth/

twelfth century) on the terms of ithnd' asharT kalim.27 6. Risdila fi 'l-hudud al-musta'amala ft 'ilm al-kaldm wa usul al-fiqh wa-'l-

mantiq, by an unknown author, a manuscript copied in 631/1233, no. 115, Institute of Arabic Manuscripts of the Arab League.

7. al-Mubinfi sharh ma'lnT alfdz al-hukamd' wa-'l-mutakallimin, by Sayf al- Din al-Amidi (d. 631/1233), on the terms of kalam and philosophy. This reflects the 'new kaladm ', al-kaldm al-jadTd,28 connected more to philos- ophy than to usul al-fiqh, as was Ibn Furak's work. Although the word does not appear in the title, the work is concerned with hudid and is much more systematic than that of Ibn Ffurak.29

8. .Hudfid al-alfdz al-mutaddwala fi usul al-fiqh wa-'l-din, by Shaykh al-Islam Zakariyya b. M. al-Ansari (d. 926/1519-20), a manuscript (Dar al-Kutub, Egypt), no. 21580B; Brockelmann, S. ii, p. 118, no. 45.

9. Risdla f-ma'dni 'l-hudiud, by al-Ustadh al-Amidi, copied in 1282/1865 in 92 pages, containing terms offiqh/usiul/kaldm and mundzara.30

This last work, together with those listed under 6 and 8 above, shows the continuation of a tradition that began with Ibn Fiurak and was carried on by a number of authors until recent times-that is, the combining of terms of usul al- fiqh, usul al-din and some jadal terminology to show the connexion between

23 Geschichte des arabischen Schriftums, i, 611. 24 University of Mash-had, al-Dhikra 'l-alfiyya li 'l-shaykh al- .Tusf, n (Meshed, 1972), 150-81. 25 ibid., 219-33; al-Tihrani in his al-DharF'a, 6, no. 1612, gives al-Baridi as al-Burdi, perhaps a

printing error. 26 University of Mash-had, al-Dhikra. 27 H. M. al-Shafi'i, al-Mubfn, 28. 28 ibid., 46. 29 al-MubTn was published in Cairo in 1983 in an excellent edition with introduction by Dr.

Hasan Mah. mud al-Shafi'? of Cairo University; in Baghdad by al-A'sam in his al-Mustalah, 303-88. 30 al-A'sam, 32.

10

PLATE I

. ..' .. . -

. . :? ,:.,:: ... '

T'I

^ -'C'/. ~' "' 'd " " " ' ' " .w% ; ' ,'.. : ' ..' -,, - ,'" ' ' '.. ;: '' - *'

4- Y 64 4 . -

? . .. .:~ . , . ,

' . *

*"...: '...r-....'. ,. . .; ....

t;> . .^ A.+.:

.. ;' i^''~ . 9v'

. - ..- ? .- :'

", *.' -? . *...,,'

w ' :^ ,^

' ' V

:"'1,; :" ;" "'"" "' * ' .... "*;~ I '^ -^?' .1 i

*; <? ??: y ..-;. -.',;":...' ",'.':;'-.", ^. ^.'.. ' , '" .',, ,, ' .' - ,:.

^^^^^-^*^ ' -'' '" '

.' -^ v ,

I^" ' T"' ' ' '

?:.

'"'. .. ,' .;-'..',.."-,... .: .'.';,,'',,.....---

.

.

'

?t'?

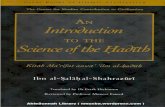

British Museum MS no. 421, Add. 9383/7. title page

BSOAS LIV]

? .. , ; :*,,,' . '.

.

- .**,',"..",...' t.

' , ? ? J,.,

'

^ A-^-^^*,'' "

-~~~~~~1

1 ,; _'** ..':

' '

," ,' * .' : "

,''t '

-*

J, p - t"< "^

AXJ . WL \k..

^t.^i ^i^l'X'Se- .S, . .,,, .. W .. f .s

I~ ? d . ? ? 2

d 5 i * ~ ~ -

.

'

British Museum MS no. 421, Add. 9383/7 'first folio British Museum MS no. 421J Add. 9383/7:;first folio

PLATE II

I BSOAS LIV]

.?

PLATE III

L05L~~~~~.

British Museum MS no. 421, Add. 9383/7. second.folio

BSOAS LIV]

PLATE IV

British Museum MS no. 421, Add. 9383/7. last folio

BSOAS LIV]

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

these subjects, even after kalam al-muta'akhkhirTn came more and more into the sphere of philosophy, a trend that found its best expression in the tajrTd al- i'tiqdd of Nasir al-Din al-Tus1 (d. 672/1273).31

Perhaps the most recent work on fiqh/usuil al-fiqh terms is al-ta'rlfat al- fiqhiyya, by Muhammad Amin al-Ihsan al-Mujaddidi al-Barakati (Dakka, 1380/1960), in which the author has relied on many previous works listed in his introduction. The material is extensive, very clearly arranged, and shows the continuing need, especially in non-Arab Muslim countries, for this type of work.

III. General works on terminology These contain terms of fiqh/usul, and kalam, among many other topics.

Compilers of such works relied on specialist authors of works on specific subjects and in most cases list side by side various definitions of a given term common to a number of areas, a method which is particularly useful for comparison and distinction. Of this general type we will mention the following:

1. Mafadt.h al-'ulum, referred to earlier, by Muhammad b. Ahmad al- Khwarizml (d. 387/997). This consists of two parts (maqala). The first deals with Islamic Arabic subjects in six sections (abwdb): fiqh, kaldm, then nahw, etc., each containing a number of subsections (fusul). The second maqala deals with subjects introduced into Arabic from other cultures, such as philosophy, medicine, engineering, music, etc. The two parts contain in 'll 15 sections which include 93 subsections.32

2. Kitdb al ta'r[fdt, by 'Ali b. M. al-Sharif al-Jurjani (d. 816/1413). First published by G. Flugel in 1845 and reprinted in Beirut, 1969, this contains terms with their definitions in all varieties of subjects arranged alphabetically for easy reference (p. 4).

3. Kashshdf istilahdt al-'ulufm wa-'l-funun, by Muhammad b. 'AIl al- Tahanawi compiled in 1158/1745, an extensive dictionary published in India in two volumes (1564 pages) in 1862 and in Cairo in 1963.

4. Jdmi'al-'ulum fi'stildhdt al-funun, compiled in 1173/1759 33 by 'Abd al- Nabi b. 'Abd al-Rastul al-Ahmad Nakiri al-Hindi. This is another extensive dictionary on terminology of various subjects, known as Dustur al-'ulamd, published in India in four volumes in 1329/1911.

Kitdb al-hudfidfi 'l-usul, by Ibn Ffrak The title is given on the title page as Kitdb al-hudid fi 'l-usul; in the

introduction the author states he has been asked to dictate hudidan wa- muwdda'dt wa ma'dnT 'ibdrdt; and in the final paragraph he says: najaza kitdb al- huduid wa-'l muwdda'at.

I have chosen to use the first title, which is the one adopted by biographers and bibliographers as well as by the copier of the manuscript; it is also shorter and more directly indicative of the subject matter as borne out by the content, the format, and the author's own definition of al-hadd, no. 5 and al-asi, no. 125. In praising the book the copier speaks of it as a majmu', but this is clearly not meant as a title, and it recalls the description majmua'dt used earlier by Imam al- Haramayn for treatises by Ibn Ffurak.34 In the works on terminology cited we

31' Nasir al-Din al-Tufisi and his Tajrid al-i'tiqad: an edition and a study', by H. M. 'Abdel Latif, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lcndon, 1977.

32 pp. 5-6. The second maqdla was isolated in a separate risdala of al-.Huduid al-falsafiyya in the manuscript discovered by al-A'sam and published in his al-Mustalah, 205-28.

33 See the introduction to the kashshdf of Tahanawi (Cairo, i963) p. [d]. 34 al-Burhdn fi usul al-fiqh, I (Qatar, 1399/1978), 449.

VOL. LIV PART 1. 2

11

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

note a variety of expressions for the words ' terms ' and ' definitions '. For the first, Ibn Fuirak used muwdda'dt and 'ibdrdt dd'ira bayn al-'ulamd'; al-Amidi used alfdz al-hukama' wa-'l-mutakallim[n; both Jurjani and Tahanawi used istilahdt. For 'definitions' Ibn Fiurak used hudud (preferred by philosophers and the majority of writers on kaldm); al-Amidi used sharh ma'dn, as he was asked to do, although his material consists of technical definitions; al-Jurjani uses ta'rTfdt, less formal than hudud, but more commonly used in works onfiqh; Tahanawi uses kashshdf ' revealer of meanings'.

By usul, Ibn Ffurak, judging from the content, clearly means usuil al-din 'theology' and usdl al-fiqh 'jurisprudence ', even though he refers to the latter in the introduction asfuru' al-dTn as they relate to al-ahkdm al-'amaliyya rather than al-ahkdm al-i'tiqddiyya which is the domain of theology. The relationship between the two types of usul was strong from the beginning: Abtu Hanifa's book, al-Fiqh al-akbar, is on kaldm; the term usuliyyun was, moreover, used for scholars of both subjects.35 We have also seen a continuing tradition of combining the terminology of the two subjects, even after kaldm had become more strongly connected with philosophy. As to the exact designation of kaldm, it is interesting to note that Ibn Ffurak talks of usul al-din, and 'Abd al-Qahir al- Baghdadi calls his book on kaldm 'usul al-d7n ', whereas al-Ghaz.ali has iljdm al- 'awdmm 'an 'ilm al-kaldm, and al-Amidi has ghdyat al-mardm fi 'ilm al-kaldm; while Muhammad 'Abduh's book is entitled Risdlat al-tawhTd.

The range and circumstances of the writing of the .Hudu-d Ibn Ffurak's .Hudud contains 133 definitions, each labelled ' hadd'. However,

he sometimes includes additional material related to a term he has isolated for definition with the label' hadd' (see 44, 68, 89, 92, 94, 130-32). The result of this practice is that we have in the .Hudud a much higher figure than the 133 definitions numbered there.36 Numbers 1-92 are taken up by the definition of introductory items in kaldm, e.g. 'ilm, nazar, etc. and then terms relating to the section known in kaldm as ildhiyyat, with only passing reference to ' reward and punishment' (which is part of al-sami'yydt in kaldm); 93-8 deal with the section on nubawwdt (there is nothing on imdma, which became a customary chapter in kaldm); 99-133 with usul al-fiqh. Under hadd al-'illa (133) he brings in 8 terms of jadal and defines them, presumably because the discussion of the subtle points of 'illa always give rise to debate.

This distribution of definitions shows that about 74% of the Hudud is actually on kaldm and only 26% can be said to be on usul1 al-fiqh. Thus both Brockelmann and Sezgin were wrong to classify Ibn Fuirak's work as usul al- fiqh.

They were no doubt led to do so by the British Museum Catalogue which translated the title Kitdb al-Hududfi 'l-usul as Liber definitionum jurisprudentiae. The compiler of the entry, apparently without examining the content of the work, clearly understood usul in what had become the more commonly used sense of the word, i.e. as usul al-fiqh. Surprisingly, both Brockelmann and Sezgin say the .Hudud is on Hanafi usul; Ibn Fuirak is well-known as a Shaifi'i, in spite of the fact that Ibn Qutlubugha includes him in his Tdj al-tardjim on Hanafi tabaqdt. But by comparison with the several pages Subki dedicates to Ibn Furak in his Shfi'T

. tabaqdt, Ibn Qutlubugha devotes less than three lines to

35 See A. S. al-Nashshar, Manahij al-bahth 'ind mufakkir[ al-islam (Beirut, 1984), 99; Sa'd al-Din al-Taftazani, Sharh al-'aqd'id al-nasafiyya (Damascus, 1974), 4-5.

36 Incidentally, the only work we have before Ibn Ffurak that repeats the word hadd with every new entry is Risdlat al-hudid, by Jabir b. Hayyan.

12

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

the subject (no. 185), with no bibliography, and gives Ibn F-urak's name merely as Muhammad b. al-Hasan al-Wa'iz al-Isfahanl. Perhaps it was this that led Brocklemann and Sezgin to their conclusion. It is possible, too, that someone was influenced by an inscription in the margin of the back page of the manuscript of Kitdb al-hudiud which states that its owner was a Hanafi judge. The fact is that Ibn Fiirak's other work (the muqaddima mentioned above) is definitely on Shafi'i usul and, as we shall see, some of the material there is identical with that in the Hudid. (See also hadd no. 112 and footnote.)

After praising God and invoking His blessing and peace upon the Prophet and his family, Ibn Fuirak addresses his students:

'As you have asked memay God continue to gU ide you!to dictat. Je to

' As you have asked me-may God continue to guide you!-to dictate to you some definitions, terms, and meanings of expressions current amongst scholars of theology and sharV'a, such as have been accepted by our teachers, the validity of which I consider well established, and to make them brief so that they may be accessible and easily memorized. I respond to your request desiring thereby the reward from God and bounteous recompense when we return to Him. Thus I say-and God is the One who guides (us) to what is correct ....

This suggests that the Hudiud was written when Ibn Fiurak settled in Nishapur and was teaching there in the school built for him, from which a number of pupils in kaldm and usul al-fiqh graduated under his tutelage.37 It was written to meet a need felt by his pupils, and it was they who suggested the form and the word hudud, probably inspired by the form and word already used by philosophers like Jabir b. Hayyan and al-Kindi. It is not unlikely that 'ibdrdt dd'ira bayn al-'ulamd' bi-usul al-din wa-furiu'ih mimma'rta.ddh shuyukhund meant that such terms, at least among the Sunni Ash'ari, were at that stage being isolated and defined by Ibn Ffurak for the first time in this form. 'Such as have been accepted by our teachers' may be understood in the light of the fact that writings of Shi'i terms appeared first. The concise style and considered opinion of the master would seem to confirm that the author wrote the Hudu7d at the stage we have suggested. From a comparison made in the footnotes to the Arabic text between some of Ibn Furak's definitions and those given by other authors we can see the conciseness, clarity and effective use of language which marks the text of the .Hudfid and fits the purpose he had in mind: ' to make them brief so that they may be accessible and easily memorized'.

The attribution of Kitdb al-hudiud We have only one manuscript copy of the JHudud, but its attribution to Ibn

Fuirak is confirmed by a number of factors. It is agreed by all biographers that he was a scholar and author of books on usul, and al-.Huduid in particular has been named as being his. Examples of material and ideas in the .Hudiud appear, sometimes verbatim, in other works by him, such as the Muqaddima, or are attributed to him in the works of early writers, including al-Qushayri, who was a

37 Ibn 'Asakir, TabyTn kadhib al-muftar (Damascus, 1347/1928), 232; Ibn Taghribirdi, al-Nujtum al-zahira (Cairo, 1933), iv, 240).

13

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

pupil of Ibn Fiurak, Imam al-Haramayn and Subki.38 Moreover, the Ash'arite spirit of this work, in which he set out to give the definition of terms ' such as have been accepted by our teachers' is similar to that of his Kitdb mushkil al- hadTth wa-baydnih where he set out to refute the views of such ' deviators' as al- jahmiyya wa-'l-mu'tazila wa-'l-khdwarij wa-'l-rdfi.da wa-'l jismiyya.39

It should be remembered that the manuscript copy we have of the Hudfid belonged to a man learned in usul, a Yemeni q.ddi who writes on the back page that he himself had' copied it for his own use and for whoever came after him as God willed '. He considered himself greatly favoured to have possession of this work of Ibn Ffurak. More important is the fact that it was fortunately copied from an original, compared with at least one other copy, possibly more, and then checked carefully, as the copier states on the title page:

and on the last page: .-v Jj 4,Jl . L . In five instances, on folios y?, P0, V, ~?, '. the copier has added

words which he had clearly missed in the first instance, then inserted the sign of correction C" : It is clear from nn. it, rn, ot, on, V'n, o, in our edited text that the copier had more than one original to compare with. He gives the author's full name on the title page and at the beginning of the text. So what we in fact have here is not an ordinary single copy of a manuscript but one that had been carefully checked by a scholar against other copies. All these factors taken together leave little room for doubt as to Ibn Fiirak's authorship of this text.

The significance of Kitdb al-hudfid The importance of this text, published here for the first time, lies firstly in the

fact that it is, as far as we know, the first book of definitions written by a Sunni Ash'arite scholar. It lies outside the scope of this article and the space available to give a full account of the Ash'arite theological stance in comparison with Mu'tazilism and Shl'ism with reference to works by Muslim and European authors. Our remarks here are intended to give an idea of Ibn Fuirak's standpoint on the hudfid in particular: it is hoped that the works referred to in this section and in the footnotes to the Arabic text give a sufficient basis for expansion.

The difference between al-Hudid and the Shi'l works is obvious. We need only to compare Ibn Fiurak's definition of imdn (61-2) with that given by Shl'i authors in the works on definitions cited above. Ibn Fuirak defines imdn merely as knowledge of God (in which belief is implied), whereas the Sh'il author adds knowledge of the Prophet and of the Imams as stipulated in usul al-dTn.40 Shi'i texts also include definitions of Imam and Imdmiyya 41 and Ibn F-urak has no place for either. His simple definition of taqiyya (79) as 'fear of doing an act or

38 See for instance, al-Risala 'l-qushayriyya (Cairo, 1972), 661-2; al-Burhdn fi-usul al-fiqh (Qatar, 1399/1978), 354-5, 820; Tabaqdt al-shdfi'iyya (Cairo, 1966), iv, 134-5; Kitdb al-hudud, nos. 93-4, 112. In Hudud no. 17 Ibn Ffurak talks of God as al-rabb, using a Qur'anic word, rather than wajib al- wuju-d, as did later theologians. That this is his standpoint is confirmed by his views as cited by 'AhI 'Umar al-Sakfini in 'Uyin al-munazardt (University of Tunis, 1976), 277-8. Compare also .Hudud 109 with p. 9 in the Muqaddima of Ibn Fuirak; 111-12 with p. 5; 113 with p. 10; 114, 128 with p. 6, where we find wording identical with Hudud 113, and almost so with 112. We find also these same ideas of Ibn Fuirak's expressed in Hudad 112-13, and attributed to him in al-Burhdn of Imam al- Haramayn, i, 449-50, which in this case confirms Ibn Ffirak's Shafi'i rather than HanafT standpoint. Compare also nn. 47-8 below.

39 Kitdb mushkil al-had[th, 4. 40 al-Dhikra 'l-alfiyya li 'l-shaykh al-TusT, ii, 219. 41 ibid., 153, 240.

14

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

abstaining from it' makes it different from the technical Shi'l taqiyya, which has special significance for the Shi'Ts and is regarded by some as their distinguishing feature.42

In many instances the Hudfd clearly shows Ibn Ffurak as an Ash'arite whose opinions differ from those of Mu'tazila. In the definition of al-'dlim (2), for instance, he considers the sifdt as being ghayr al-dhdt. He also defines al-shay' (13) as being al-maujud, whereas to the Mu'tazila, it is that which will happen, even though it does not yet exist, because it is implied in the knowledge of God. Ibn Fiurak emphasizes his opinion by saying al-ma'dfm (14) laysa bi-shay'. His Ash'arite definition of Kasb (19) clearly differs from the Mu'tazilite view.43 The same can be said of his opinion on 'what can be seen' (57) according to which God can be seen.44 Similarly, his definition of 'adl (87 and see 85) is different from that of the Mu'atazila, on which they built their belief that it is an obligation on God to do what is beneficial to man. Finally he expresses the Ash'arite view (explicitly saying ''ala 'l-sad[d min madhhabind') when he gives for the meaning of kaldm, al-kaldm al-nafsl (under 95).

Secondly, Ibn Ffurak's Hudad is significant in that it combines terms of kaldm and usul al-fiqh.45 This was in an early phase of kaldm (al-kaldm al- gadTm).46 An example of the strong early connexion between kaldm andfiqh has been seen in Abui Hanifa's book on the theology, al-Fiqh al-akbar. There are also two recognized approaches in usul al-fiqh; the first is tar[qat al-mutakallimTn or al-shdfi'iyya; the second, tarTqat al-fuqahd' or al-ahndf.47 Biographers often talked of a scholar as being a master of al-aslayn, and of the connexion between usul al-fiqh and usil al-din as like that between a branch and a stem. Early scholars like Ibn Fiurak, and other authors who followed his approach, e.g. Ibn Taymiya, seem to have wished to relate usul al-dTn to usul al-fiqh and to avoid the approach of the Greek logicians (of which Ibn Taymiya wrote a refutation), unlike other authors, such as al-Ghazali, al-Razi, and Nasir al-Din al-Tus1.

The fact that the .Hudud is an example of the early kaldm is confirmed by the introductory terms, which deal with al-'ilm and al-nazar, etc. These are also to be found in the works of such early authors on kalam as al-Baqillan1, 'Abdel- Qahir al-Baghdadi, whereas later works usually begin with more philosophical terms, such as al-wujud wa-'l 'adam or al-ashkil al-arba'a, as we see in Tuisi's tajrTd,48 or combine the earlier terms of 'ilm, nazar, etc. with those of philo- sophy, as did al-Razi in his Muhassal afkdr al-mutaqaddim[n wa-'l-muta'akhirin. It is, moreover, noticeable that most of the terms Ibn Fuirak defined are of Qur'anic origin, e.g. 'ilm (1), nazar (6), kasb (19), ibtidd' and i'dda (35-36), rather than derived from Greek philosophy. From no. 58 to no. 100, for instance (i.e. 42 terms), there are only four that can be said to be non-Qur'anic (70, 73, 77, 90). Thus the proportion of Qur'anic words is not less than 90%. This contrasts sharply with al-MubTn, by al-Amid1, where the percentage is clearly much lower. A comparison between al-Hudfid of Ibn Fiurak and al- Mub[n of al-Amidi (which is on philosophical and kaldm terms) is interesting: the former has 133 definitions, 98 of which are kaldm; the latter has 223 definitions. Of the 98 on kalam in the Huduid only 26 (20%) can be found in al-

42 See ' Takiya', El; Razi, Muhassal afkar al-mutaqaddim[n wa-'l-muta'akhkhir[n (Beirut, 1984), 365-6.

43 See al-Amidi, Ghdyat al-mardm fj 'ilm al-kalam (Cairo, 1971), 206-7. 44 ibid., 156-67. For a general view of the Mu'tazilite theology see the El. 45 We have seen earlier that this combination was continued later by a number of authors. 46 For the two types see Ibn Khaldfun, Muqaddima (Beirut, 1886), 465-6; al-Taftaz.ani, Sharh al-

'aqd'id al-nasafiyya, 5-6. 47 A. Khallaf, 'Ilm usul al-fiqh, 18. 48 See H. M. Shafi'i,'al-MubTn, 566-92.

15

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

Mub[n. al-Amidi died 230 years after Ibn Ffurak and both men were Sunni authors. Our comparison here may serve as an indication of how far 'the new kaldm' had moved towards adopting philosophical terminology.

Another feature indicating the early date of the IHudud is the components Ibn Fturak uses to make up his definition. Sometimes he merely gives one word, as in nos. 13, 26 and 31. What we have here is certainly not the Aristotelian Perfect, or even Imperfect, Definition, which is concerned with the essence or quiddity of a thing; the definition of early usuliyy[n seeks merely to distinguish a thing from what is other than it (see no. 5).49

al-Hu.dfid, then, provides a good example of early kaldm. We may none the less discern a trace of philosophical influence upon it. I have already argued that the title and, I think, the format, were inspired by work on philosophical hudud. Ibn Fiurak includes al-jawhar (20) and al-'arad (23) for definition, but the number of such terms is very small and they have become well known to scholars. Ibn Fiurak clearly chose not to go deeper in this direction; thus under his definition of al-'illa (132) he noted how al-'ilal al-shar'iyya are different from al-'ilal al-'aqliyya; the latter concept is philosophical, discussed in later kaldm by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.50 The fact remains, however, that the .Hudud is dis- tinguished in being the earliest extant book of definitions of early Sunni kalam, which it combines with usul al-fiqh.

Ibn Furak's life and works Abu Bakr Muhammad b. al-Hasan b. Fiurak al-Ansari al-Isbahani, was

born about 330/941, perhaps in Isfahan. Not much is known about his early life. He studied Ash'arite kalam under 'Abdallah b. Ja'afar al-Isbahani, and became a scholar of kalam, usul al-fiqh, tafsir, hadith and grammar, as well as a celebrated preacher. From Iraq he went to Rayy and there he aroused the enmity of ahl al-bida'who defamed and slandered him, upon which a delegation of admirers requested al-Amir Nasir al-Dawla Abfu '1-Hasan M. b. Ibrahim to write to Ibn Fuirak to invite him to Nishapur; there he built him a house and a school from which a number offuqaha' graduated. Among those who narrated hadTth on his authority were Abu Bakr al-Bayhaqi, Abu '1-Qasim al-Qushayri and Abu Bakr Ahmad b.' Ali b. Khalaf. His biographers tell stories that testify to his piety and to the high esteem in which he was held by pupils and audience. He was also involved in much fierce dispute with members of the Karramiyya sect who were probably responsible for his being summoned to Ghazna by Sultan Mahmiud, to whom it was alleged that Ibn Fufirak was a heretic who believed that the Prophet Muhammad was dead in his grave and that his Prophethood had ceased. Upon hearing Ibn Furak's denial of all this the sultan showed him generosity and ordered that he be returned in honour to his home in Nishapur. On his way back Ibn Furak is said to have been poisoned and he died in 406/1015; his body was carried to Nishapur and buried at Hira, where his grave became something of a shrine.

Numerous bio/bibliographies of Ibn Fturak have been compiled, and perhaps the most important source is Ibn 'Asakir (465/1072) in his tabyTn, to which subsequent authors, such as al-Qifti (646/1248), Ibn Khallikan (681/ 1262), and Safadi (764/1362) have not added anything new. al-Subki (771/369) in his Tabaqdt al-Shdfi'iyya brought useful information, while Ibn Taghribirdi (874/1469), Ibn al-'Imad (1089/1678), then Brockelmann, S. i, 277-8, Sezgin, I,

49 See A. S. Al-Nashshar, Mandhij al-bahth, 102-4. 50 ibid., 579-81.

16

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

610-11, and El, (new ed.), III, 766-7, and all modern Arab bibliographers have repeated the earlier material.

Ibn Fiurak was an important Ash'ari theologian of the second generation after 'Abui '-Hasan al-Ash'ari and was in fact responsible for the best available bibliography of al-Ash'ari's works, which was preserved by Ibn 'Asakir in his taby[n.5' Reference to Ibn Fiurak's ideas on kaldm and usul al-fiqh and other subjects are found in such early works as al-Risdla 'l-Qushayriyya by his pupil al-Qushayri (d. 465/1072) (about 20 references) and al-Burhdnfi usul al-fiqh, by Imam al-Haramayn 'Abd al-Malik b. 'Abdallah (d. 478/1088) (8 references).52 His views on usuil al-fiqh were quoted by such important authors on usul as al- Isnawi, al-Bayd. awi and Ibn al-SubkT.53

Ibn Fiurak's works are said by his biographers to have numbered about a hundred. Most seem to have been short treatises (in al-Burhan, I, 449, Imam al- Haramayn referred to Ibn Fuirak's majmu'at) and most have unfortunately been lost. Of particular importance are the following:

Kittb mushkil al-had[th wa-baydnih (with variations in the title), Hyderabad, 1362/1943, 241 pp.; partially translated into German under the title Baydn Mugkil al-Ahddit by R. Kobert (not R. A. Robert, as in Sezgin), Analecta Orientalia, 22, 1941. This is the better-known work of Ibn Fiurak, in which he attempts to explain difficult phrases in the hadTth which were claimed to imply anthropomorphism and, at the same time, to refute the views of the Jahmites, Mu'tazilites, Rafidites and others.54 Kitdb al-Hududfi 'l-usul, the manuscript edited here. Muqaddima fi nukat min usuil al-fiqh, Beirut, 1324/1906, 14 pp. al-NizdmT fi usul al-dTn, which he wrote for al-wazir Nizam al-Mulk,

Ayasofia 2378, 156 fols. 790 A.H.

Mujarrad maqdldt AbT 'l-Hasan al-Ash'arT, 'Arif Hikmat, Medina; ed. D. Gimaret, Beirut, 1987.

Tafs7r al-Qur'dn, Feyzallah 50, III, c. 200 fols.

The manuscript the Kitdb al- .Hu.dud To sum up, the manuscript copy of the .Huduid edited here (British Museum

MS no. 421, Add. 9383/7) dates back to 988 A.H. (not 991 as in Sezgin) and was owned by Muhammad b. 'All al-Hamawi al-Hanafi, a qd.di in the Yemen. It consists of 13 fols. (51-63), including the title page. The main text pages include 15 lines each, written in good, clear naskh (copies of the title page, the beginning of the manuscript and of the final page are reproduced here by way of example). I have already mentioned how meticulous the copier was, how the manuscript was checked throughout and compared to at least one other original. In the present edition I have followed modern orthographic conventions, supplied serial numbers for the huddud as well as an Arabic index at the end. The index includes the terms Ibn Fuirak isolated for definition under hadd and these are followed by their numbers. It also includes terms which occur in the body of his text, but which he did not isolate under hadd, and these are followed by the number of the page of the Arabic text on which they occur.

51 Tabyfn kadhib al-muftarf..., 126-7, 136. 52 See index of al-Risala al-Qushayriyya; al-Burhan fi-usuil alfiqh. 53 A. M. al-Maraghi al-Fath al-mubfn fi tabaqdt al-usuliyyfn (Cairo, n.d.) I, 239. 54 See article on Ibn Fuirak in EI.

17

18

- I-vt, I-.l. "i. ;,G.l ? (k

, inTcj,,,4+.t ^.. ?:YI,yt I . * 1. ;t, <ij T J t uw1k L*,<JL

j^" ^ ^ ' J 8 < 9 J.?.J A J.7.4 J 1 AilI :I J^4 c

. () 4I p / W 1 JJ (1)

; i IS < l < .li C)ltJl i *JXll ? :J1 AJI. (2)

. z ,,-1 jti La i s "^/ .]Az i Y ^i ( (i) *4J c A >1 - SI J' 1Jul x) (

-!..j --ii I VA4W I^J A l ol

1

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

,? (..J-1.: , . - 4. t .f ,:, s.. J. j,(a)I l : . 1,j J ( ) .( 38) z..

A. ,Ij j I4u . , J , ( (L )

*( ) J .-J L4uj '.I^ IJil l i jL 2 (5)

r\y ,\ (8r) ; d^ o ^^ ^^lll # jJ Lo (9)

. L

jr- -JF <J^ >tj ^^l A *Xlyl JA L^ W , J C IJ11 iJ j L.As5l cj '11 (M 1

,,,I ' v~. . ..,...- ~ Jt,:. " ~ . ,. J x .,I ,: . j. *j Li .,. 'j. u U. 'j LI u a:wI c( ~l

.(38) l

J

-

s ^.ij. Sl 6 \^s^ ct-l 9 Jl ,^ j-\. A 'NO Y <.ll A jui ^ . 41S' qj^d 4 i. (A)

" u - 4 A ^t )

19

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

* r1j ^ JJ >-^>lI tLa 6_ A1 A . J (10)

. ~8. L#lJb> OOj^<3^j! l awlj^ (12)

.?(o) a.All ..: ,l,. (13)

? . ^J . i LL s ' r A. - 11 - (14)

. aL11 J o u + lc a j l ;: ?.r11 (15)

.( C ) o5. ~z,jj .% '.1- e_J.1. ll Ul . & .Jjt ~.scL ' ej.,J.l 5 (16)

,(~^) l.. ..,J ]! 04 %' (w?) ,1 %, cj C ill . . J, (17)

* jn. Sj Llj l LJ ^ j oll

* 'L.jA^t j^ j^L 4J : 4Uaj, 4LjJ &;1 J?i 1 ! (18)

^^1^1 <;SYL ; . JJ I u ;,I J J 1 ( 19) .(")<.jjjjAL

o.; J..~. ,:.,. ~A ~ ~-1 L,C J,l. X.l II, ~ J I- 'IJ

A.L?-? Jj ,,,,r I JJ (\A)

? &J ,~ ..,~. :-J~ (

w s s r wJI > 1s^1 j.^ J 1 1 2 Y, (1 5 A U ,p, Z ow,l ,Z , - J.eI; I ; . )L ^ I * (TWA y3. I 4;L;LI ,l l ) AJI j T L1

4 4. Ji 1k J^ J 1

." J1.S {*WJ!:ajjJll JJ. ,;1l;jJAjjj1"TTTr , sj-U 1l1l^'C,jt (>s)

3

20

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

&r . <,ItX> U1 A1Y ^i,t ; g A^ j4 J., \ 1 (20)

? . jl i ? ~.t j (21)

Ij5. ) l? )A ;j.,U.1P CV. 4I (! 4, .l ,i1 ~ )l U , );.,, l (22)

' <?^-.^ <~ j ̂ *4'. 1 ?4^ o . .^A.JU Ja" t lJ U (23)

LAj^ 't,J ^. bt - (~) u. .l. (24)

oti r^ 1., LA v ^L SZ ? a J^ L o tx1 lL (25)

.(* ) Jl>,.Jl l. ZjI. (26)

.(TT) J~ Ne. Ji i30< ''j, 0-1 J^ ^ jJlj 1. ,? < j.Ll (27)

^ jA l jt I. ,L ); ( ̂ $JL 1 , s l J W (28)

*. J J ~ . 1 i *.~ :J i 4: .J1i1 OLI _ ?.i tl .K (29)

. o. _- TiA t v 1 I 1L^J9 L@ fK 23 ^ 1 &,.W 1 , 1I (v.)

w* i1 aJliL I J * u 4 - j J l *q S (IT U)

. T WL. "^ lI|, .9 . bW I3LjljI

(T0> 1^ 1 Y ;jl a^ 1s W,, ̂ jj 9 1. t1 b W- . .- * ^| 1i @^ js jAW ^ (Vi)

4

21

22 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

.j, ?.. . Llj, j - .l .~ .. - (30)

? ;; , ^^"j1 ~(31)

~j._jt.Ki :

L^ jt " 3 .. 2u. 1 b .. IJ j, u, L ..L (32)

jA1 * j -t < JI t ?^ j^l^ aJ l 41 L Li; ' >J-1 j (33)

. Y). .ijj f.,lj L,L ,-. Oj ,,t, b. ;,' jJ.1 j (34)

,)(36) . .,e-.J ) l I .? , I .. (35)

L A4Lr I <o jJ * w L^ l ( jj 1;.3 *rlcH (36)

. (T") ,, 4 Ij , la I j, o L. 4 I\ %. (37)

*. o ..'d..~ 'C..t . . ^1%. (38) iji . (38)

* ~.g..x. 0~ , ^ . I UJ .. (40)

Lilllff,. l 0~'l da j,^ ?.^\ d. 'c.ila,li <, Jl ,^ ., .L j (41) U.: wS ol1Yl1Jx1 I ^ i . <l 'JL. ,^ L ..ua " , . ,I j(4?

(I^) 1 ' l

.2 S (TV)

. ''^t (TA)

5

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY 23

. (') IU. '

. ~ j.sjl (42)

.(r.) ?A.2f.l j ! ^jI ;h.a.~ ",,.j j o ;ibYl^.4~.j ^(43)

zo S3 5 J . La . j Y o L^ 4 J1 (44)

L;) J I 1 wY ^J 4,, ^l? <'^ , dLLllSj . 44L j1 &J

U. t).1U lj Y l ? ;L!2 %. (45)

. Y ̂jt 3 l^ jlv , t 114 Yll p | 1 (46)

Vly Jl L4 A q Jif , J - fSii Jl 1 (47)

. (rT) c<5j%'l 'l, ,! .). 6. uL o Il. (48)

?LA L., j J^ .;j . oy J- 4 s1^

,

.I, LI,%. (49) . <Jc

^ i ,, . , (50)

. t1 L* j UJt ;k L.... * ~,; , J~. fo ^ ^ ? i,- .:D- _- ,:" ,u.a1 5 (, )

. *i ;y (V ) ?Z.L

6

24 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

? o <t > ^;6 ep;JI A i* jiji I * I Lsa jIlj Lo LJ 't J jij

* ,A^L Y! t Y <jl SU^ 1Il

. jlrL^I^ ? o^j3tj^ (51)

, ~.i<, 1 ja: .j^1l 2 (52)

J3; a ,:..,.

-

?.J . ;:J1j U ,-f ~lyE1 ;,'l ,^: J^l.& j. (53) .1> s_Wo iNe US SJjIl s oJ AjJI J?. 4 <^1;>s;1 ei *U1I

.(rr) ,Jd l ' < . 1 , . " , Of J: 1 (54)

. -U-J. . ,. u -.< o., oJ,I .i .;1. u\ (55)

. ,. ?11 i.[j " j ;L- : >s^J , x1 (56)

.(r) '^l a s.s* ,jt jEZ L (57)

*,s;

,,\y^ ^ ^...^ j I (58)

^ ^! ^U^, Jj^ 'jlj ^) lU 4I ^i^'^ 'To)j^^l J

(59)

. >'YI 2 (TT>}U^( JUI , ^ tW1 \ - ?I ;Q ;1 fit 8 ." Y ^ 1, v A.] , (TT)

* TV/- ki . (^ 1?1 *AJ

to llj TO'r1 1

Irf'^ ?*Llj *Ai (^ 1 JjU@ . .b1. I- 1^Jl oB

(13)A vi jA Ll(^.l I(Ti)

L i As^\iJ y ^ "

Q ^ ,t s 1 Y (To)

. ffi1 2^ t*; H. (J) J^y ^1 i (Tr^)

7

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

l. j. .&L 1.d-, ^i.3 ,,~ .L. 4 xi ,.l x4. (60)

*LII - *JUL) IJ l ^-A ' L>L-?^~ i (66)

.(w) ,J3

?. - 2 , . .. <,1^ ,>J~ ! ; (62)

Y LS JS .9 JLA: < ,j^a Y.l IL. I, I < L l. . j(A6)

(T) bY Y\ (TA) 1> as A # J

f. 1 I, ,J ?. .-:

.

. j (64)

.j iij ij:l l < Z~jLl a Y, l ^ 1 (65)

. 14+ jj P ^tJ ^ ^l ^(66)

(J OJ u;2! ̂ l if > J , ^^ o 2! J s ?Sl^LI I , '1 ' (67)

o *1A oll U 31AlJ *ll8j I I.y4 S .11

. J 1-J;I ,-,l .1 4, U IAL U ;JLaYI X.. j.;Q1 3

. TiNo iSu 1 p vl)%1s (TA)

^;1 ;jL ,i iJj, , j^l ; 5 >\ f Ji 1S 1Ij1 *. LjL,; jjj .L ij i J (1.)

8 -~ ~. (~* 4 ,,)y1 Jz ;r 8

25

26 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

.J , $ J b * AI ,x 3', 4 - U'- - .21

a . , 1 < 1. -.J .,,-l,j, ; 1,3 S" - -,L,o, .;clj J^,J S1 ,jJ

. -&C.j - ,.J1' ~' l c u s 1,,,. -.l (69)

i. ~ 1 *l (,,; i 1. J 1, lj.~^i; , *.. t x.. (70)

~.(tt),;z11 ?J; tJ t lU0j (72)

it. ~ ~; ;. 1 j~^ ? &LJ"l Y. (73)

. ~. C 7t.1,,1 i-\ ^ .ji~l j^ * ~jlt.I j. (74)

. o\ Wc.\ : J5|d;,:

. (,i,) .l ,. , L , l, ? -L (75)

'. "c& ,, ',<.1<1 j, (76)

*yjLJ j^l - - J1 L; (t,)

,. J - p^~~l ̂U ~ s~ , ~ > ., . . .t JSL. J. a., '.\ ' d ~ ., . (ti)

. ,^*, wt. l, r. .s ,, , t.l:j !'Jb A.^ 1t ̂ L^;j, 1ll J* 6k^ v; . J (-I)

. rw T * ' '1 . . -

^ (i J j . j I , J l i t (i)

. e-TAt

9

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

&jJ j.. J. i & -,.4j Il . ll,I1 d : J.q.lj L~~l (77)

J. (av) ,3 ,Jf jJ J' j[ & . J~lI jA ? ,Id, I (79)

, " ! DI r l , , ; I . , 4 , , a I- 4\, (80)

? J,44., kj2 j (tA) ,t aij (8 )

J a jb^ Y! 4 J< <> i9 a- 2 )L l U1 JI L I (82)

. ~I o^z o.. ~ Y JLi (,^) , l J.u , . L (84)

.j 1-J9j l , I

1. - xj J o-. LI ? :. a A ~ L SY1 ~ . J e. JA1 j. X ( 84)

* 10*

+ i~

Qll J-1(85)

. ^ ^; - j ,., ;r ^i99 4 (LA)

*w1 t'-^ U. IA^ l z^ " .Ij . 11 x1 CL-, ,,+O <S1, j ", 1L-1 J.i ( v

10

VOL. LIV PART 1.

27

28 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

*. 'd2L l L, U , L. J .l (87)

j 4l l ^ ijJ'd , xil_l JL1lI A :; Jt xo (88)

. ,uJ JsLjJI,, J,..

1 A ..a-~ ^7.l! '3 3_..._, J,I '<.* ; 2t ^ ,L(). ,: (89)

1l??jLJij JLJI a iz J I < W U jj i^Y L IJ ,,L

'I k t .

a 1 . ,j ' 1' \ j (91)

. !'. .i,p I .1J. (92)

,,i L.. ,- b. 1 '.. ',. ;L ', ' J ', ,I -to .. o31 I...

fL. j ,: c-.. J .,: ,v ..S AO(o~)

L* I

. ;,J _. 6L;jW;Y j A1 iij JALI .3 1 (o.)

* J^U (ON)

11

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

L. : ~~ . \. \.\ ,.j : ^ .(o.) o; l

\;~~~~~~~~ <^i4JL] * ̂ jLjJ)\ i ;

e

Jis;lo;j f \^JUJ iJL^5 (jla) A a2 1 > 1 > '' - C96 * 21 f C.- s IL

, ~ ;:L, JI 4.~- jL,. o'~W3I~ ~ ~ ~~4. ,ilI &,? .,e J ., .ll~(

. * _ajj dL-?j n.J.j.j J^-jJI j-?l yk: *,L p *

11A o^ ^^^ * "^-J ' ^^ ,? r! M ,^^1 ^

* sVssr

jy L . <^j 18<11 a iL z..UI :iA I. ^ ,~ I -l, (93)

L"' 4ZcUA A'LLj J ( 0) <j 1 JJ t ? Wl W 0Atj L;

Lfi (94; )+u . 4j<i^j *- ^ ^^ ^ l^ L. Is < oaW^Ul .; jL; .,j t |;?1a5

r - tl u, ^ ' ,.I,JI j (94)

.^ ~l.a, * J..:. ~] ,j : ..:o , jL j,:it (o.j.i . -^

. (OV) ;$u fY=Y1

- .^LJ1 &f - isJLH , 41^31 4jQ

;L.1=11 4^ ,<< j la i <.ji;Wl ^^ vt * (OA) ;?(A

^ ^ ~~. t;"u1 A^.1 Lj ,^ U 1\ 1^ij ;<n ; . Ti^i ,- wrS Wi -.9UA o1 . llt bl

^l ^l ? @ Wt &'la IJ - ^.^ TW o^ "^

zu' ^JI (ot

* "Xf v. "!y" Si U (oo) * Js LJ ^Jl ^1^ ^ JIr J- j i 91 "V" jLi (O.)

. 1 pt ^ ;1 Y sJ^ * . VT ra JR ^ ; 1 TULyI I (oy) * ; .__1 i#b ( 4;T ;s] ,;sHt s lj ) . ^ . ^] ,^1j1 j lj 4;l 4z^jJ.l L (oA)

12

29

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

c SL- L. 1 .,J .l. L * J .@^ ~ ? :i %.L1 j (95)

.. , p .uL ? 1j1 . j. iK. ( 1 00

i) ;u1 4\1j ^ Jij <J^l)lj1 j^G1 -oA L j e U1

. L?jt jl lij^ ot j\ & \021M ̂ ^JJl ^ < jJ-l (96)

. (") w otL^^. y : LJ'll jo (97)

. t ̂! JS ci^ ^ ^1 M :1 ̂ j^ll j^(98)

.(') J&IJuaJL> I II J vI (99)

. I2QJ^ll^^IllJ^ :1 ̂ lllj^(100)

o?<_- ja Iq .3 L,j j za l^i, ? , W- Y (101)

Ju Ij zl j 4JL Jj.J I < , jt

. X;;L U. L9 LU1 Z- -J (oN)

. x i--, "?1 XI" J ^ 4JUL:I *J. it 0;4 . ;JLJl } ;j Ij l j" ;2wj 44. -J (mC)

j *> , j 1 J L, ; i-3. ..; 1 i, .j + , 1 4;J| J | I g u<l tL L;^ ('NT)

13

30

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

> Jxi X ^L ,t sA ^ b s <^ ? jt , W L (102)

. 1.a. j

Jal~A (103)

N\ " ' I t 3 JI (4 () jI Aj Yji . j l i (104)

l. :al C .b,tj, (105)

"h x^l

;1. o.)l.. 1, .? d'j ,JLI ja

~ ,.i.r ^LA, _ ! r4..1 J (106)

. 4L , .

.4 l <

O t) &L;^JIfJJJ s uij t (107)

. i 4i L9 ll 4 jl l (108)

.0?) U-1 11> J l s iul^ : l jI (109)

Vto;1 ? b ; \1 >I jj ?0 , ,jl. j (110)

. M ^, wvS . . U6,.i: I 4:Ii U LJLJI _1 I;1 ;vi;1 I 4 J

;;1 ^t0l4 S3 vV " . X j4- 41^ ^

" 4 s ,t l '

t-Ut3 aj^ j9 Y v j zL1ij.0 :et . YtO ;i 1T^ ;t>;1 ?WY ",^" ^- s1; J iO to %i "J^-YI <c tY1 S Zl . ;Ull 2 Sp 0

14

31

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

. ('^) <..?2 jt 4JU .. ,.-/ ?' jt

.(C>^) jU ^j J1 |1: JsI &1^u^L4 (12) \2

l v > Q A1 4 * m, . , J , 1 1 3)

* \^{^JjV (o ^Ij (114)

; * 4s * jt ^ M xu ^. u :t jili (I 17)

. isLtak | <A^Jb| J iA . (118)

jp-;-j ? JjJY J1 ? j lll ;, > JIJI J; 1 v : l^ - Y (119)

*. 4 S.A ,.J

. ~ ~ .tYSI u ,yo~ i,j .*. , ,.*;. ?i . U .l. ', ".o" . ia , 1..! , (V\)

i... . l. ao.t Su ,a .. 4 . ~ .l,), Y Li

,

. . "

, .-" '

Jz (J( )

z. "1 .." - . . . (114) t_.l @ ?1 J -,I . oLl.

' 1 Z .IO L - >. 1 . "i-? " a W UL j~ ~ j L. U - (I A)

0^1Sl @ j"I tS >9 Lei g ji < . , , "V " . NY s Ia ;.bu il 4 i

J^v. P <1 zI ;)J I v sT N oW u 11 j ^ LJ I . L., %j i;A zJ" 1 l (v. )

. :16

15

32

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY 33

(vE) J: M'L; uj u.j ^ 1'.^:. : IjI. (121)

)1 us J.-.. s * I (Jl, 4J 1 w ,J1 t jj + Ai1 j 4(122)

., < >k J^U l? : *JL>.J 7^^ /J ^^ J??,T.,..^ < (YT), A i : A .

.J

j /J^ ,I ^ l ,.JI ? L.,JT. .:. I Jj L-, j1I (123)

1! ~b di, * ~cJ~l ,z ~, jl ~, ~.Y ,~.\ c,-- oi ,1,

16* j.,F jl(124)

. ^ #^ ifj La , : (125)

*. a^ jAiK G 4^ b31 ^ (126)

.,.l 1 ^ ) ^^ : &Ji1 - (127)

.(* aiJ y u ( 128)

. f ju b @ 4 A l ! I

L- (129)

.(V) S*Uj i^ l ^JJIJ lil^ :0 ^LLi j- (130)

. <-5l j \ ^ : IjJl

* TOw j T4u 1 , Jsb U

16

34 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

. ? .6 I . - J , . :a1

s~ - stJ bYI . - 4 ,.l L " jl L

. 3.^i1

' :.~.1

*. :l1.1 < ..j I

*(w) 1 -/

3 ..,... ;.. ?u. i,C, JL., . ~...,AW '

v,,.,

. buSl.

.. N D.JJ oll 1 S1 I A1 \I . j I ill

1 i I L I1

L j?Li ^ l l> V ? Ul (va)

^ur )1 ";.]1 )l>.j x,; l L-1 ;r {LLz a-ti L 2 * J.I S j S L. by- (w)

-ji L .Li i j!U L . 1U j j j l. -JI VA ;a64,j .lA ,lj C A1 C - , 4 (VA)

51. Cl ^ L-JII JJ.jj 4 ^

17

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

,YI ~ : ~ ., : r(v^).

'

, .,. '. L, ? JI . (132)

cLj ^t o;;1 . j < c j i? *J ^ y ̂ ^ J

-J(

* 4y1;4YI+ * (A *aY <

1 * * st j J Yl,:^^/^^/^j 2h a Y ;JaY ^

< ̂ ^JL JL (A) W L Jd (Ar ) U r

,,^Jl, , , ,LY (AA) (T)

* t.1,

' *, j J j \ ?<.f.. . .I., (A ,x1 ) 1

.5 j 4 Y L a.i :(^) :Jl

'. 4, '~ n '4. ' (A-:

;,'~ . ,\^ \;- U.l . J c1 ' . j^ ,* ~.Ja,a L. U @' "~" 3.-G (^.)

* .-1 ,, " L, (A\)

,. ,., '1 ~ ~, , Ijr.l IJ *1 J c r^ Jb ? 3 LJI J: :til . , 1 . 6 j ; . (A^)

. A\-OVY

. r .i^ ".311 SI b 6,- " J .j ., "(Jj .'1r .tU ; (AT)

i W yl JI XJJIj \^\L<I iJ. '

(At)

^Ul *2_Ac c \ {,A,I J f tI ' , 1 s . V e ;l lI) 6'1 -J Jol V U^kQl i (Ao)

. ILJI C.L.. L JjLJLlj . IL X\ }

j <;4

* Jj1 . Ip ;- rtwJ l [\ JI I." 4 Wi * C1 ;o >JiL e (A\)

18

35

36 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

. L1^(Ay) 4li ^ 1 _t& . J^LiI

.WI J (^1) t 1I ju I iX

. & 1?+4 1jul jllXJ

* p lt u $ 1

j~~~~~~~ (AA yi^ . Irj^ljJ

* ̂ (^ ^ -^^^ ZJ^ 1 Z ! i11

Lo Aij < 7- 4-< a L o LJ \aL o : JWS A t J91 F J928 M A;1L

JUj * 4 Li X ;1 - >

A; ka *': v u.-

4

IY1 \N> 9>LIS i b JA j 91 J

0vJtJ ( ^fi^ " Jj^. ,5? <1J ,? f^^ U^?s1 ^J (

.s (A<<) ?1 "

~ O~J^ j^ y . ?LY1 ( J yfj Jl (AV)

* ^^ l4! ^;I~ ^ ^~j~ < . ^t ^1|~ 9 j l ^(Ai ) ^

()

^ l< ,t l1 jt . <L ji ^^ t I j4I h1^h 4 (

<^LJ? ̂Ifr Jk-jJI <>-J>J-^ J^AJ ( ^,;.>Jl) JAAII (jLu (^*) JL^U "(J^ j" .. I, (AN)

j^S ot J'<^ ,,>- ,,t ,^-< e; ̂ fr^dl XLu^ [j] . <^jJ r NT _ijj- foj^i AJA |^ < 4^L jj _iJ o J^ -c ^jy ^

. ") r L ia 2t (A

r1 W.0 (AA)

.L - b J,.l ^u* -^ T.- ,^ J^ ^Ul 2a l tl (A\)

* (112) jJ l r . .UJ l4-l at 4M? @j i (fi8

19

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY 37

.n j, 8 .u*Y1 9 ^Lh!l - ( 1j?l ( 33)

20

3?r ja ,Cf Ij I (NY)

M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

tl,.^1 . 50 J:^Y I 24 "YI . 35 olijAl . 105 6lYl (S1)

l* - YI . 43 o10.jl I 18 J Il r- ls 17 . 3 I . 109

,.1 J ,J . 125 ^., . 67 ?.. . 14 , lo t . 119

. 80 o, 25 31YI . 18 , ; 316 36 ;a 107

61 jl,1 . 101 .l. 991,U 65 A1l

. 34 J1 . 121 .LJI . 40,Uj. 11 J.UI (.)

.?.l.. 17 W-Ul . 77 l,3- -L> . 127 &J", () .79 I.l. 133 .ai-l . 29 -Jl,1 3 I" 3 il. 19 I .

,59 .l 82 .y1 . 46 U3l . 76 .1 69 ..1

? 9 ll.'1 17 " -l1l

11o a. ill 11 , -1 (6)

86 j1.21 ^.1. 19 ,-1-1.' 19 " Ja.- -.

20,,1.

. 26 LJ. . . 14 " .. 5 L..l 3 o-. l . (z)

123 :'1 11 " .l . 91 -l . 74 j,2.I

, 15 L -Jl l--' , 46 ;?-. ,l 11 o I .l 53 J -lI

, 55 Lil . 116 ,,,\ , 73 ,Ji..1 .I 96 ( ) 31 &i..iL

.. - c. ..L j ,,,J. s j-Jy .r~I *

21

38

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

JJJ1 9 au-.x I j I 1 13 tLlaS Is 8 JJL (X)

.8 8 Pij> 10, 1

.90 JiI (?)

.12, ,, l L , 17 O,. l. (1)

?19 w J..1 131 ZI - , 27 LJ1, 19 Oa Jl (k)

, 11 ., ,17 o L ^ AJI , 18 o 3_1. , 11 . t II (t) . 13 A.1. 45 ;^

. 10 o, -J1.97 1j-. 10 1" . 17 1 (I ) . 22 ;, I1

, 38 I,i1

.9o Jo, 1 , 33 ,.AJl (I )

.18 w a3.1, 72 I X17 (1,)

52,211 , 16 ,p 1.1, 85 ~WI , 115 jWll (J)

, 81 j,ll 17 Oa -l, 87 JxA , 88 ;aL1 . 2 1 (.) , 132 ;lJI 7 J3I , 84 yI.Jl , 75 i_l , 23 ;v,Jl

0,1 , 1 9 1 z , 19 o a.1 L.1 , 19 o .u;1\1 XI

.18 O .KJi , 114 fl , 4 ..,. l J1 , 3 jj,, Il

. 32 &OW I. 17 O &W1 I.. 12 .W51 ()

22

39

40 M. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM

, 63 .;l , 126 t[.I 117 . L.LI L? 6 66 j,il (j)

lj.11, 41 *L Ul 17 " ,CUJIL 108 ....1 17 J-al

.17 ,

, 15 I.^*ll , 42 ;?JaiIl , 92 .~1 . 37 .: , 1 (J)

, 19 O, . 17 o, L . 71 .l1 . 12 o l*1l

. 118 oLyl;

. 44 l.AJI . 94 <1,.1 . 98 l.~L , 95 qLl (J)

, 13 , ?531 62 1 , 18 I .- 1 , 19 9 .....' 1

28 11 ' 51 oi?l

.9 , 0 .lI (J)

, 30 . \ , 130 .A-Ll 106 t.Il , 57 , O1.)N. i ' (?) , 16 IA.I , 47 JL.-,L . 128 -l. I, 124 jL.U

, 56 sal1 . 11 ral l 122 d11 , 14 ~ j l

. 93 ;.1 17 - .l. 13 o, , tj,. , 17 , ..kl

.il 9 ,J, guill. 19 o Jj2~k , 14 j.Il I 118 ji&ul

,4.! ~. l , 6 LL.1J , 54 l1 ., 117 Il . 129

60 .1 . 49 ll , 78 .L . 104

, 6 .1 , 1 1 I aJ1 , 120 JI1 , 103 .jJl, 12";j- l (-) , 99 o2I , 6 " Jtl1- , 18o,, O;i l1 14 jo :i l, 64 W3i l

.70 LJI

.68 1jl41 (A)

23

EARLY ISLAMIC THEOLOGICAL AND JURISTIC TERMINOLOGY

, 12 ,' , , 58 .,l . 14 o a . 1 11 , 102 .i1 (,)

. 39 .I. 1

24

41