Does managerial sentiment affect accrual estimates...

Transcript of Does managerial sentiment affect accrual estimates...

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Accounting and Economics

Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50

http://d0165-41

☆ WeStephenSymposCollege

n CorrE-m

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jae

Does managerial sentiment affect accrual estimates? Evidencefrom the banking industry$

Paul Hribar a,n, Samuel J. Melessa a, R. Christopher Small b, Jaron H. Wilde a

a Tippie College of Business, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USAb Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 2 December 2014Received in revised form28 September 2016Accepted 11 October 2016Available online 18 October 2016

JEL Classifications:G20G21M40M41

Keywords:SentimentEarnings qualityAccrualsLoan loss provisionBanking industry

x.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2016.10.00101/& 2016 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

appreciate helpful comments and suggestioPenman, Nick Seybert (Discussant), Chris Wium, the University of Bocconi, University of Iof Business, University of Iowa for financialesponding author.ail address: [email protected] (P. Hriba

a b s t r a c t

We examine whether managerial sentiment is associated with errors in accrual estimates.Using public banks we find (1) managerial sentiment is negatively associated with loanloss provision estimates, (2) future charge-offs per dollar of provision are positively as-sociated with sentiment when the provision is estimated, and (3) the effects of sentimentare greater for firms with more uncertain charge-offs. Results are similar for private banks,suggesting accrual manipulation related to capital market incentives is unlikely to explainthe results. Although economic fundamentals explain most of the variation in the provi-sion, we find sentiment has an incremental and economically meaningful effect.

& 2016 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

A growing body of research considers the role of sentiment in financial decisions. In common usage, the term sentimentrefers to feelings or beliefs about a situation, state of affairs, or event. Applied in the finance and accounting literature,however, the term sentiment more narrowly depicts beliefs that are unjustified based on available information (e.g., Bakerand Wurgler, 2007). While evidence indicates economic data justify the majority of beliefs about the state of the economy(e.g., Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006), research shows that sentiment has meaningful effects in both asset pricing andcorporate decision-making settings. For example, Baker and Wurgler (2006) find sentiment is associated with return re-versals in stocks that are difficult to value and arbitrage, though the effects are less evident in highly competitive and liquidmarkets where investors can arbitrage away security mispricing and discipline the potential effects of psychological biases.

ns from S.P. Kothari (editor), Robert Bloomfield (referee), Mark Bagnoli, Ted Christensen, Jed Neilson,illiams, and workshop participants from the 2015 FARS Midyear Meeting, BYU Accounting Researchowa, Michigan State University, Purdue University, and University of Texas-Dallas. We thank the Tippiesupport.

r).

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 27

Importantly, corporate decision making settings lack an easily accessible arbitrage mechanism to discipline biased decisions,increasing the likelihood that sentiment will affect individual decisions, especially in settings of high uncertainty (Bloom-field, 2010). Consequently, behavioral forces acting on individuals have the ability to influence the behavior of institutions inpredictable ways. Indeed, prior research indicates that sentiment affects analysts’ estimates (Clement et al., 2011; Hribar andMcInnis, 2012), institutional investors’ portfolio allocations (Cornell et al., 2014), and managers’ pro-forma earnings dis-closures (Brown et al., 2012).

In this study, we investigate whether managerial sentiment – managers’ unjustified beliefs about future firm outcomes – isassociated with errors in accrual estimates. Accrual estimates require managerial judgment and estimation about expectedfuture realizations. The inherent uncertainty in future outcomes allows for both strategic discretion and unintentional errors inaccrual estimates. Consistent with the aforementioned research showing that decisions of sophisticated individuals exhibitsentiment in settings of uncertainty, we posit that managerial sentiment may lead to errors in accrual estimates, wheremanagers’ over (under) optimism results in accrual estimates that are too low (high).

To study our research question, we examine bank managers’ estimates of the loan loss provision. In the banking setting,managerial beliefs that are unjustifiably optimistic (pessimistic) could lead to under (over) estimation of future charge-offsand thus a negative association between managerial sentiment and the loan loss provision. The loan loss provision is aparticularly well-suited accrual for detecting the potential effect of sentiment on accrual estimates for three reasons. First,the loan loss provision is the most significant and economically important accrual in the banking industry. Second, availabledata on loan accounts allow us to observe the economic realization (i.e., charge-offs) to which the provision relates, and thusto evaluate the accuracy of loan loss provision estimates. Third, regulators require banks to file call reports, enabling us tocollect private bank financial statement data and use a private bank sample to rule out some of the alternative explanationsfor our results that are based on capital market incentives.

Our primary tests use measures of managerial sentiment derived from the Duke University/CFO Magazine BusinessOutlook Survey, which surveys managers’ levels of optimism about their firms’ future prospects. Using the aggregate surveydata, we examine both the unadjusted quarterly measure of average managerial optimism from the survey (‘raw beliefs’),and the residual from a regression of the quarterly measure of average managerial optimism on an inclusive set of mac-roeconomic variables (which more directly captures unexplained beliefs or ‘sentiment’). The second measure follows di-rectly from sentiment reflecting managers’ beliefs unjustified by available information. Regressing the raw measure ofbeliefs on macroeconomic factors allows us to separate the justified or rational component of the survey responses, from theunjustified or sentiment component.

We first examine the association between managerial sentiment and the loan loss provision. If managerial sentimentaffects the loan loss provision, then variation in the provision should be negatively associated with managerial sentiment,after controlling for other determinants of the provision. Using quarterly data from 2002 to 2013 for publicly tradedcommercial banks, we find that both raw beliefs and the unexplained beliefs are negatively associated with loan lossprovisions. When measures of quarter t sentiment are higher, ceteris paribus, the loan loss provision estimated in quarter t islower. Consistent with prior research, we find that economic fundamentals are the primary driver of the loan loss provision.However, we also show that managerial sentiment has a nontrivial effect on the provision. On average, a one standarddeviation change in sentiment is associated with a 1.60% change in the loan loss provision, or a 1.04% change in after-tax netincome. In addition, we find that for banks where the loan loss provision is more difficult to predict, a one standard de-viation change in sentiment is associated with a 3.60–4.80% decrease in the loan loss provision, and a 2.34–3.12% change inafter-tax net income.1

We next consider whether accrual estimates made in periods of high (low) sentiment are too low (high) by examiningfuture charge-offs as the realization of the accrual. If managerial sentiment biases managers’ accrual estimates, then loanloss provisions estimated during periods of high sentiment should be associated with greater future charge-offs per dollar ofprovision compared to those estimated during periods of low sentiment. We find that the ratio of future charge-offs tocurrent loan loss provision is significantly higher when the provision is estimated in quarters when measures of sentimentare high. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in sentiment is associated with one-year ahead charge-offs that are3.25% higher per dollar of provision. These magnitudes are comparable to the effects of earnings management incentives onthe loan loss provision. For example, a one standard deviation change in earnings before the provision (tier 1 capital ratio)results in a 3.03% (6.12%) increase in future charges-offs per dollar of provision.2 Our result suggests that managerial sen-timent is associated with biased accrual estimates and mitigates concerns that the result of the test of our first hypothesissimply signals managers’ rational responses to private or public information that is correlated with our measure ofsentiment.

This test also helps us validate our decomposition of beliefs into justified and unjustified components. Regardless ofwhether managers’ beliefs are justified or unjustified, either component should lead managers to adjust their loan lossprovision. Therefore, we expect both explained and unexplained beliefs to be associated with the provision. In contrast, onlyunjustified beliefs should be associated with a change in future charge-offs relative to the current provision. Thus, if our

1 We use the volatility of charge-offs and non-performing assets to assess the level of uncertainty in predicting charge-offs. We discuss this analysis indetail in Section 4.6.

2 Bushman and Williams (2012) and Beatty and Liao (2014), among others, discuss incentives to manage the loan loss provision.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–5028

decomposition is effective, we should observe that the unexplained component of quarter t beliefs has a greater effect onthe ratio of future charge-offs to quarter t provision than does the explained component. Consistent with these expectations,we find that both the explained and unexplained components of beliefs are negatively associated with the loan loss pro-vision, suggesting that both components explain variation in the provision. Importantly, however, we find the effect ofbeliefs on the ratio of future charge-offs to the current provision is weakly significant (or insignificant) for the explainedcomponent, whereas it is highly significant for the unexplained component at both the one-quarter ahead and one-yearahead horizons. These results are consistent with the unexplained component being a more direct measure of sentimentthat leads to estimation error in the loan loss provision estimates.

Finally, to help rule out the concern that the bias in accrual estimates associated with managerial sentiment is strategic, werepeat our primary tests using a sample of private banks. Simpson (2013) argues that during high sentiment periods, managersstrategically bias accruals to induce a short-term increase in stock price or to meet overly optimistic analysts’ forecasts. Oursample of private banks has neither analyst following nor the opportunity for managers to generate short-term stock priceincreases by strategically biasing accruals. Thus, if our results are attributable to the strategic explanations in Simpson (2013),we should not observe similar findings among the private banks. Here, we find the results of the private bank tests areconsistent with the public bank results, suggesting that the bias in loan loss provisions is unlikely to be attributable to strategicaccrual manipulation arising from incentives to temporarily increase stock price or meet analysts’ expectations.

We conduct a number of additional analyses to further examine the association between managerial sentiment andaccrual estimates. Consistent with theoretical and empirical work suggesting that the effects of sentiment and similar biasesare greater in settings of higher uncertainty (e.g., Hirshleifer, 2001; Daniel et al., 1998, 2002; Baker and Wurgler, 2006;Hribar and McInnis, 2012), we find the association between managerial sentiment and provision estimates is significantlylarger when charge-offs are more difficult to predict. We also find that the primary results are robust to excluding thefinancial crisis period.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. Within the financial reporting literature, prior work suggeststhat managers can identify and respond to mispricing generated by less than fully rational investors. For example, Bergmanand Roychowdhury (2008) and Seybert and Yang (2012) find evidence consistent with managers strategically responding toinvestor sentiment in their earnings forecasts. We add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that psychological biasescan also unduly influence corporate decisions (Baker and Wurgler, 2013; Ben-David et al., 2013) by showing that managerialsentiment affects accrual estimates. Our results suggest that managers can be overly optimistic (pessimistic) in periods ofhigh (low) sentiment for non-strategic reasons, especially when uncertainty is high.

In addition, our study contributes to the literature on earnings quality by providing evidence that managerial sentimentlowers earnings quality by generating bias in accrual estimates. Our results suggest the magnitude of the sentiment-inducedbias is economically meaningful, but also credible, given the presence of external auditors and regulators who monitorbanks’ financial reports. Given the central role that earnings quality plays in valuation and contracting decisions (e.g.,Penman and Sougiannis, 1998; Watts and Zimmerman, 1978; Lambert, 2001) and the fact that psychological biases are likelyto affect accrual estimates in systematic and predictable ways, we believe the results of this study will be of interest toinvestors, standard setters, auditors, and regulators.

Finally, our study contributes to the research that identifies determinants of loan loss provisions and informs thestanding debate over the accounting for credit losses (Bushman and Williams, 2012; Bikker and Metzemakers, 2005;Bouvatier and Lepetit, 2012; Beatty and Liao, 2011). Under FAS 114, current loan loss accounting uses an incurred loss modelwhich specifies that for an expected loss to be accruable, a loss-causing event must have occurred by the date of thefinancial statements. However, managers must still apply significant judgment in estimating the loss-causing events (andtheir impact) that have occurred up through the date of the financial statements (e.g., Grant Thornton, 2012). In June 2016the FASB issued an Accounting Standards Update, effective beginning in 2018, requiring banks to record credit losses onloans based on expected losses (FASB, 2016). While permitting managers to use more forward-looking models in provi-sioning for loan losses could be beneficial, these models require increased judgment and estimation from managers, whichallows for greater estimation errors.

2. Background and hypothesis development

Considerable research in accounting examines the determinants and consequences of intentional accrual manipulation,which is generally assumed to reduce earnings quality (e.g., Dechow et al., 2010). This research provides evidence consistentwith firm-level attributes (e.g., Dichev et al., 2013; Francis et al., 2005), managerial incentives (Armstrong et al., 2010),capital market incentives (e.g., Ayers et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2005; Burgstalher and Dichev, 1997), and constraints—including governance features, auditors, regulators, and other external parties—affecting managers’ accrual decisions.

In contrast, relatively few studies consider the determinants and consequences of non-strategic errors in accrual esti-mates. Examples of previously considered determinants of errors include objective difficulties in projecting future outcomesdue to environmental uncertainty, management lapses, and clerical errors (Francis et al., 2005; Hennes et al., 2008; and Levet al., 2010). Errors from these types of factors can generate noise in accruals. Other possible sources of bias in accrualestimates relate to individual psychology. While the evidence in social psychology on individual decision-making is vast,surprisingly little archival research considers whether these same forces generate bias in accrual estimates.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 29

One possible source of errors that could result in biased accrual estimates is managerial sentiment. Similar to the de-finition of investor sentiment used in prior literature (DeLong et al., 1990; Morck et al., 1990; Chan and Fong, 2004; Bakerand Wurgler, 2006, 2007; Sabherwal et al., 2011; Simpson, 2013), we define managerial sentiment as managers’ beliefsabout future firm outcomes that are not justified by the information available to them. Although our definition of man-agerial sentiment is similar to the definition of investor sentiment used in prior literature, the two constructs are distinct, asinvestor sentiment is defined as investors’ unjustified beliefs about firm value, whereas managerial sentiment refers tomanagers’ unjustified beliefs about their firms’ financial prospects.

Two conditions are necessary for managerial sentiment to impair accrual estimates. First, managers must be subject tosentiment; that is, at times, some managers hold beliefs about future firm outcomes that are unjustified by the informationavailable to them. Second, the financial reporting process must provide sufficient latitude for accrual estimates to in-corporate managers’ unjustified beliefs. Thus, a priori, it is unclear whether managerial sentiment affects accrual estimates.On the one hand, several studies suggest that managers are sophisticated individuals who are able to identify and exploitthe incorrect beliefs of investors. For example, prior research finds that managers identify and exploit investor sentiment inequity issuances (Baker and Wurgler, 2002), dividend payouts (Baker and Wurgler, 2004; Li and Lie, 2006), investment(Gilchrist et al., 2005; Polk and Sapienza, 2008), and disclosures (e.g., Bergman and Roychowdhury, 2008; Brown et al.,2012). Simpson (2013) suggests that managers cater to investor sentiment via accrual manipulation and Hribar and Quinn(2013) use managers’ trading patterns to provide evidence that managers trade against and exploit investor sentiment forpersonal gain. Taken together, these studies depict managers as sophisticated individuals who, rather than having incorrectbeliefs themselves, recognize and take advantage of the incorrect beliefs of unsophisticated investors.

On the other hand, several recent studies suggest that sophisticated individuals are subject to sentiment. Hribar andMcInnis (2012) document a positive relation between sentiment and analyst forecasts for "difficult-to-value” firms, con-sistent with analysts being subject to sentiment. Walther and Willis (2012) provide additional evidence that sentimentaffects analyst forecasts. Cornell et al. (2014) find that when investor sentiment is high, institutional investors increase theirholdings in “difficult-to-value” firms with low-quality accounting information, and sell-side stock analysts issue more fa-vorable recommendations for the same firms. Moreover, unlike investor sentiment where rational arbitrageurs can correct amispriced stock, there is no arbitrage mechanism to correct a manager’s incorrect accrual assessment, although it shouldbecome apparent when the accrual reverses.

Of particular importance to our paper are several studies that provide evidence consistent with managerial sentimentinfluencing managers’ decisions in other settings. Brown et al. (2012) study the effects of investor sentiment on the dis-closure of pro forma earnings and find that managers release higher pro forma earnings when sentiment is high. Althoughthey find evidence that managers identify periods of high investor sentiment and opportunistically report pro formaearnings to take advantage of investor sentiment, they also find some evidence suggesting that managers themselves areaffected by sentiment. In addition, Ben-David et al. (2013) find that Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are, on average, severelymiscalibrated. By showing that their miscalibration measure based on CFO forecasts of S&P 500 returns is highly correlatedwith their miscalibration measure based on CFOs’ own-firm projected returns, Ben-David et al. (2013) shed new light on thebiases in managers’ corporate forecasts and beliefs.

To investigate whether managerial sentiment is associated with accrual estimates, we consider the effect of sentiment onbanks’ loan loss provisions. We avoid using common measures of discretionary accruals in our study for two reasons. First,many accruals are not estimates. For example, there are changes in working capital accounts that constitute a substantialcomponent of aggregate accruals that might reflect a relatively small amount of estimation (e.g. purchases of inventory).Thus, using a measure of discretionary aggregate accruals would reduce the power of our tests. Second, by disaggregatingtotal accruals and focusing on a specific accrual estimate, we can test our hypotheses using an account specific model of theaccrual estimate, thereby avoiding some of the measurement issues associated with models of aggregated accruals(McNichols, 2000; McNichols and Wilson, 1988; Guidry et al., 1999; Leone and Rock, 2002).

We use banks’ loan loss provisions as our accrual estimate of interest for several reasons. First, by definition, loan lossprovisions represent managers’ estimates of incurred losses associated with banks’ loan assets. Second, banks’ loan lossprovisions are very important in terms of economic magnitude relative to other accruals. For example, using a sample ofbanks from 2005 to 2012, Beatty and Liao (2014) find that the mean of the absolute value of the loan loss provision is 56% ofthe mean of the absolute value of total accruals. Third, loan loss provisions reflect managers’ estimates of future loan charge-offs. Because banks are required to report loan charge-offs, we can use this data to evaluate the accuracy of managers’ loanloss estimates. Finally, the banking industry allows us to use a sample of private banks to more directly address concerns andcompeting explanations related to managers’ capital market incentives.

Accounting for the loan loss provision is similar to the accounting for bad debt expense. The loan loss reserve (or al-lowance) account is a contra asset account, which reduces banks’ recognizable receivables by the amount that bankmanagers expect to be unable to collect due to loss-causing events. Managers increase the loan loss reserves through theloan loss provision with net loan charge-offs reducing the reserves as loans become uncollectible. During our sample period,FAS 114 stipulates that banks reserve for loan losses using the incurred loss model, which requires that a loss in quarter t beprovisioned for only when (1) information is available prior to the issuance of the quarter t financial statements that theasset (receivable) has been impaired (i.e. a loss-causing event has occurred) and (2) the amount of the loss is reasonablyestimable. Because many loss-causing events may not be observed until well after the events have occurred (e.g., a bor-rower’s loss of employment), managers use loss-estimation methodologies to infer the amount of loans that have likely

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–5030

been impaired. The SEC (see Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 102, “Selected Loan Loss Allowance Methodology and Doc-umentation Issues”) and bank regulatory agencies recommend that managers’ loss estimation methodologies incorporatenumerous factors such as prevailing industry conditions, national and local economic and business trends, competition,legal and regulatory requirements, and the effects of changes in credit concentrations (e.g., Grant Thornton, 2012). Althoughthese adjustment factors rationally affect managers' beliefs about loan losses, the discretion in estimating the effects of thesefactors on loan losses also provides a mechanism for sentiment to affect the provision.

We propose several hypotheses concerning the association between managerial sentiment and managers’ estimates ofloan loss provisions.3 If managerial sentiment affects the loan loss provision, then when managerial sentiment is high (low)(i.e., managers hold unjustifiably positive (negative) beliefs about expectations of future firm prospects), managers willunder (over) provision for future charge-offs, resulting in a loan loss provision that is lower (higher) than what is justified bythe information available to them. Thus, we expect the contemporaneous correlation between loan loss provisions andsentiment to be negative. We formalize our first hypothesis as follows (stated in the alternative form):

H1: The contemporaneous association between loan loss provisions and managerial sentiment is negative.

In general, managers increase (decrease) the loan loss provision when there is an increase (decrease) in the amount ofloans that are likely impaired. However, if managerial sentiment biases managers’ accrual estimates, then on average, inperiods of high (low) sentiment managers will under (over) provision for future charge-offs. Thus, for every dollar of loanloss provision estimated in a period of high (low) sentiment, we expect banks to exhibit relatively greater (lower) realizedfuture charge-offs. Therefore, we expect the ratio of future charge-offs to the period t provision to vary positively withmanagerial sentiment. If managerial sentiment does not affect provision estimates (or our measure of sentiment simplyproxies for some macroeconomic factor that affects estimates of loan loss provision), then the ratio of future charge-offs toperiod t provisions should not vary with sentiment. Consistent with the arguments above, we propose our next hypothesisas follows (also in alternative form):

H2: When current period sentiment is high, the amount future charge-offs per dollar of current period loan loss provision ishigher than when current period sentiment is low.

Simpson (2013) posits that managers use discretionary accruals to exploit investors’ incorrect beliefs about firm value inorder to maximize short-term stock prices. Consistent with the findings in Ali and Gurun (2009), Simpson argues there is a“greater price effect per unit of accruals in high-sentiment periods than in low-sentiment periods, which probably heightensincentives for managers seeking a short-term boost to stock prices to inflate accruals during high sentiment periods relativeto low-sentiment periods” (Simpson, 2013, 873). She finds a positive association between investor sentiment in quarter t�1and discretionary accruals in quarter t, and contends that managers are able to identify periods of mispricing (caused byinvestor sentiment) for their own firm, then opportunistically manage earnings to temporarily increase stock price. Al-though Simpson (2013) documents a positive relation between current accruals and lagged investor sentiment, if measuresof investor sentiment are correlated with measures of managerial sentiment and both measures are autocorrelated, it ispossible that this catering theory could explain a negative relation between loan loss provisions and contemporaneousmanagerial sentiment.

Simpson (2013) also argues that high investor sentiment may induce managers to manipulate earnings in order to meetoverly optimistic analysts’ forecasts. Thus, if investor sentiment is correlated with managerial sentiment, a negative asso-ciation between loan loss provisions and measures of managerial sentiment could result from managers manipulatingearnings in response to optimistic bias in analyst forecasts, consistent with investor sentiment affecting such forecasts.Bergman and Roychowdhury (2008) and Hribar and McInnis (2012) find that the optimistic bias in analyst forecasts in-creases with investor sentiment and prior research suggests that managers face strong incentives to meet analysts’ ex-pectations (Brown and Caylor, 2005; Graham et al., 2005). If managers manipulate accrual estimates in order to achieveearnings expectations set by analysts who are affected by investor sentiment, and measures of investor sentiment arecorrelated with measures of managerial sentiment, this behavior could explain a negative relation between loan lossprovisions and managerial sentiment.

The potential link between the strategic accrual manipulation hypothesized by Simpson (2013) and managerial senti-ment hinges on managers having incentives to manipulate accruals to meet analysts’ forecasts or to strategically exploitinvestor sentiment to temporarily boost stock price. One way to help distinguish between our main hypothesis and thestrategic response or catering hypothesis is to test for a relation between accrual estimates and managerial sentiment in asetting in which managers do not have these incentives. If the relation between managerial sentiment and con-temporaneous loan loss provisions reflects managers catering to investor sentiment, it should not exist in settings wherethese incentives are absent. However, if sentiment generates an unintentional bias in the provision, then the hypothesizednegative relation should exist even in the absence of these incentives.

Beatty et al. (2002) note that private firms have concentrated ownership structures with a relatively small number ofshareholders, a large portion of which participate in managing the firm. Shares of private companies are thinly traded, and

3 The hypotheses refer to sentiment at the construct level. When we describe how we operationalize managerial sentiment (in Section 3), we discussadditional predictions we make to validate our proxies for managerial sentiment.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 31

given the makeup of existing and potential shareholders, it is unlikely that managers of private companies have the abilityand incentives to exploit variation in the sentiment of unsophisticated investors and generate short-term increases in stockprice by intentionally manipulating accrual estimates.4 In addition, because analysts typically do not provide earningsforecasts for private banks, managers of private banks do not have incentives to manipulate earnings to meet analysts’earnings expectations. We note that managers of private banks are likely to have other incentives to manage earnings. Suchincentives could be related to capital and regulatory requirements (Beatty et al., 2002) or profitability targets. However,there is little reason to expect that these incentives are associated with sentiment. Thus, evidence of an association betweenaccrual estimates and managerial sentiment in a sample of private banks mitigates concerns that the association simplyreflects accruals manipulation related to incentives to meet analysts’ expectations or to exploit investor sentiment totemporarily boost stock price. Consistent with this discussion, we hypothesize that our predictions from H1 and H2 will holdin a sample of private banks. We formalize these hypotheses as H3a and H3b (stated in the alternative form):

H3a: The contemporaneous association between loan loss provisions of private banks and managerial sentiment isnegative.

H3b: When current period sentiment is high, future charge-offs per dollar of current period loan loss provision is higher forprivate banks than when current period sentiment is low.

3. Methodology and sample

3.1. Measuring managerial sentiment

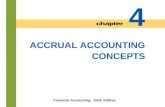

We derive our measures of managerial sentiment from the Duke University/CFO Magazine Business Outlook Survey.5 Foreach quarter, the survey aggregates the individual responses of hundreds of CFOs from both public and private companies inmany different industries. Survey questions are designed to capture inter-temporal changes in financial executives’ per-ceptions on a variety of issues including corporate optimism, growth expectations, and capital investment plans.6 Weconstruct our first measure of managerial sentiment using the median response, each quarter, to the following question:“Rate your optimism about the financial prospects of your own company on a scale of 0–100, with 0 being the least opti-mistic and 100 being the most optimistic.” We scale the median response by 100 and label it BELIEFSt.7 The solid line in Fig. 1displays the median survey responses of managers over our sample period.

3.2. Explained and unexplained beliefs

One issue with using BELIEFSt as a measure of sentiment is that macroeconomic conditions undoubtedly affect managers’beliefs and their estimates of loan loss provisions. Because we define managerial sentiment as managers’ beliefs that areunjustified by the information available to them, it is important to account for any macroeconomic factors that both affectBELIEFSt, and justifiably affect LLPi,t. Hence, we follow prior literature (e.g., Baker and Wurgler, 2006; Lemmon and Port-niaguina, 2006) and use OLS to decompose BELIEFSt into two components: a component explained by macroeconomicconditions (EXP_BELIEFSt) and a component that is not explained by macroeconomic conditions (UNEXP_BELIEFSt). BothBaker and Wurgler (2006) and Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006) discuss the construct of sentiment as being unwarrantedby fundamentals and both studies use the residuals from regressions of sentiment indexes on macroeconomic fundamentalsto develop “cleaner proxies” for sentiment. Thus, we use UNEXP_BELIEFSt as a second proxy for managerial sentiment.

We acknowledge that our decomposition of BELIEFSt into EXP_BELIEFSt and UNEXP_BELIEFSt may not perfectly separatemanagers’ justified and unjustified beliefs. For example, any systematic over- or under-reaction by managers to macro-economic fundamentals could be captured by EXP_BELIEFSt. Thus, a portion of the variation in EXP_BELIEFSt could reflectvariation in managerial sentiment. In addition, to the degree that the set of regressors used to decompose BELIEFSt isincomplete, UNEXP_BELIEFSt could reflect rational beliefs. Nevertheless, consistent with Baker and Wurgler (2006) andLemmon and Portniaguina (2006), we use UNEXP_BELIEFSt as our second proxy for managerial sentiment as UNEXP_BELIEFStrepresents the component of managerial beliefs that is orthogonal to fundamentals.

In decomposing BELIEFSt, we follow Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006) and employ a broad set of macroeconomic

4 Beatty and Harris (1999) also contend that private firms have a greater fraction of long-term shareholders and less information asymmetry and, thus,weaker incentives to manage earnings.

5 Other measures of sentiment include the Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index (e.g., Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006; Simpson, 2013) and the Bakerand Wurgler (2006) measure of sentiment (e.g., Hribar and McInnis, 2012). Prior work uses these alternative measures as proxies for investor sentiment. Toour knowledge, prior research has only used the Duke University/CFO Magazine Business Outlook Survey as a measure of managerial sentiment (e.g., Brownet al., 2012) and we believe this survey provides the most direct measure of managerial beliefs.

6 See www.cfosurvey.org for additional information about the survey.7 Although the question does not specify a horizon over which managers should assess their optimism for their firms’ prospects, the survey is ad-

ministered quarterly, other questions in the survey refer to optimism in the prior quarter, and other questions ask about expected performance over thenext 12 months. Therefore, we believe that managers are likely to assess their optimism about firm prospects over a relatively short horizon such as thenext year. This time horizon is consistent with the horizon managers should consider when estimating the loan loss provision (see Ronen and Ryan, 2009).

Time Series Variation in Sentiment and Beliefs, 2002-2013

-0.025

-0.02

-0.015

-0.01

-0.005

0

0.005

0.01

0.015

0.02

0.025

0.5

0.55

0.6

0.65

0.7

0.75

0.8

1-M

ar-1

2

1-M

ar-1

1

1-M

ar-1

0

1-M

ar-0

7

1-M

ar-0

6

1-M

ar-0

8

1-M

ar-0

9

1-Se

p-10

1-Se

p-08

1-Se

p-09

1-Se

p-07

1-M

ar-0

51-

Sep-

05

1-M

ar-0

41-

Sep-

04

1-M

ar-0

31-

Sep-

03

1-Se

p-02

1-Se

p-06

1-Se

p-11

1-M

ar-1

3

UN

EXPL

AIN

ED B

ELIE

FS

BELI

EFS

Date

BELIEFS SENTIMENT

Fig. 1. Time series variation in sentiment and beliefs, 2002–2013.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–5032

variables. Specifically, we include the return on the CRSP value-weighted index including distributions (MKTRETt), thedifference between the yields to maturity on Baa- and Aaa-rated bond yields (DEFt), the yield on the three-month Treasurybill (YLD3t), GDP growth (GDPt), personal consumption expenditures (CONSt), labor income (LABORt), the unemploymentrate (URATEt), the consumer price index inflation rate (CPIQt), and the consumption-to-wealth ratio (CAYt).8 Also consistentwith Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006), we include contemporaneous, lagged, and lead measures of the macroeconomicvariables in the model.9 We estimate the following OLS model:

∑ ∑β β β β β β β β β β

β β ε

= + + + + + + + + +

+ + + ( )= =

BELIEFS MKTRET DEF YLD GDP CONS LABOR URATE CPIQ CAY

LEADS LAGS

3

1

t t t t t t t t t t

j j k k t

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

18

19

27

where LEADS represents the leading values (quarter tþ1) of the macroeconomic variables and LAGS represents the laggedvalues (quarter t�1). The residual, ε̂t , represents the component of managers’ beliefs unexplained by macroeconomicconditions, our second measure of managerial sentiment. We label the residual from Eq. (1) UNEXP_BELIEFSt and the pre-dicted component EXP_BELIEFSt. The dashed line in Fig. 1 displays the residual from Eq. (1) over our sample period.

Although the explained portion of beliefs potentially includes some sentiment, if UNEXP_BELIEFS, as compared to EX-P_BELIEFS, is a more direct measure of beliefs that are not justified by fundamentals, then we should observe evidenceconsistent with our predictions related to H1 and H2. In particular, we predict a negative contemporaneous associationbetween the loan loss provision and both EXP_BELIEFS and UNEXP_BELIEFS, as we expect managers’ beliefs (whether justifiedor not) to affect the loan loss provision. However, the relation between the current loan loss provision and future charge-offsdiscussed in H2 should be stronger for UNEXP_BELIEFS compared to EXP_BELIEFS. Because a variety of forces can constrain orinfluence accruals, and because some of the variation in EXP_BELIEFS could be attributable to managerial sentiment, it ispossible that EXP_BELIEFS also affects the relation between the current loan loss provision and future charge-offs. However,to the extent that UNEXP_BELIEFS better captures sentiment, we predict that this component will have a greater effect on therelation between loan loss provisions and future charge-offs than will EXP_BELIEFS.

3.3. Empirical design

3.3.1. Tests of H1H1 suggests that the contemporaneous association between managerial sentiment and loan loss provisions is negative.

To test H1, we first estimate the following pooled OLS models:

β β β β β β β β β

β β β β β β ε

= + + Δ + Δ + Δ + Δ + + Δ +

+ + + + Δ + Δ + + ( )

+ − − −

− −

LLP BELIEFS NPA NPA NPA NPA LOAN EBP

CO CAPR ALW GDP UNEMP CSRET

SIZE

1 2a

i t t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t

i t i t i t t t t i t

, 0 1 2 , 1 3 , 4 , 1 5 , 2 6 , 1 7 , 8 ,

9 , 10 , 1 11 , 1 12 13 14 ,

8 See Appendix A for precise variable definitions.9 Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006) conduct their primary tests with contemporaneous and lagged variables and add lead measures in additional tests.

We include lead measures of macroeconomic variables in Eq. (1) to proxy for managers’ rational expectations about future economic conditions. Becausefuture economic conditions are unobservable at time t, managers’ expectations may differ from actual realizations. We include MKTRET to control for theportion of future macroeconomic factors unexpected at time t.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 33

β β β β β β β β

β β β β β β β β ε

= + _ + _ + Δ + Δ + Δ + Δ +

+ Δ + + + + + Δ + Δ + + ( )

+ − − −

− −

LLP UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS NPA NPA NPA NPA

LOAN EBP CO CAPR ALW GDP UNEMP CSRET

SIZE

1 2b

i t t t i t i t i t i t i t

i t i t i t i t i t t t t i t

, 0 1 2 3 , 1 4 , 5 , 1 6 , 2 7 , 1

8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 1 12 , 1 13 14 15 ,

where LLPi,t is the loan loss provision estimated for bank i in quarter t and BELIEFSt is our measure of managerial sentimentobtained from the Duke CFO survey for quarter t.10 Our interest in Eq. (2a) centers on β1. If managerial sentiment affectsestimates of the loan loss provision, then when sentiment is higher (lower), we expect the estimated provision to be lower(higher) such that β1 should be negative because an optimistic manager will reduce the loan loss provision, ceteris paribus.In Eq. (2b) we replace BELIEFS with its decomposition into expected and unexpected components: EXP_BELIEFS andUNEXP_BELIEFS.

In Eqs. (2a) and (2b), we control for numerous bank-level variables shown to affect loan loss provisions. Consistent withprior literature (Beatty and Liao, 2014; Bushman and Williams, 2012; Liu and Ryan, 2006), we include ΔNPAi,tþ1 and ΔNPAi,t

in the model to reflect the possibility that some banks use current and forward-looking information on non-performingloans in estimating loan loss provisions. We include ΔNPAi,t�1 and ΔNPAi,t�2 to capture the fact that banks use historicalinformation about non-performing loans to estimate loan loss provisions. We control for bank size (SIZEi,t�1) given thepotential differences in regulatory scrutiny or monitoring for banks of different sizes. We control for loan growth (ΔLOANi,t),as loan loss provisions may be higher when the bank extends credit to more clients with lower credit. We also follow priorresearch and include the lagged loan loss allowance (ALWi,t�1) (see Beaver and Engel, 1996; Beck and Narayanamoorthy,2013). If a bank has recognized relatively high provisions in prior quarters, then a lower current provision may be justified,as the prior quarter loan loss allowance may be sufficient to account for expected uncollectibles. Because the amount ofcharge-offs is related to the level of the allowance, which in turn affects provisions, we follow prior research and include netcharge-offs (COt) in the model (Wahlen, 1994; Collins et al., 1995; Beatty et al., 1995). We add controls for earnings before theprovision (EBPi,t) and tier 1 capital ratio (CAPR1t) to control for potential incentives to manage earnings (e.g., Bushman andWilliams, 2012; and Beatty and Liao, 2014). We scale all firm-level variables by total loans in quarter t�1. Finally, we includethe change in GDP (ΔGDPt), the return on the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index (CSRETt), and the change inunemployment (ΔURATEt), as prior literature identifies these variables as determinants of loan loss provisions (e.g., Bush-man and Williams, 2012; Beck and Narayanamoorthy, 2013).

3.3.2. Tests of H2H2 predicts that the amount of realized future charge-offs per dollar of loan loss provision estimated in quarter t is

increasing in the level of quarter t sentiment. We test this hypothesis by estimating the following pooled OLS model:

β β β β ε= + + + + ( )+ −CO LLP BELIEFS EBP CAPR/ 1 3ai t i t t i t i t i t, 1 , 0 1 2 , 3 , 1 ,

β β β β β ε= + _ + _ + + + ( )+ −CO LLP UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS EBP CAPR/ 1 3bi t i t t t i t i t i t, 1 , 0 1 2 3 , 4 , 1 ,

In Eq. (3a), our interest is in assessing whether current period sentiment is related to the amount future charge-offs perdollar of current period provision. Therefore, in Eq. (3) we include control variables that prior research suggests may bias theprovision (i.e., affect the provision but not future charge-offs). We include EBPi,t and CAPRi,t�1, to account for managers’incentives to smooth earnings (e.g., Bushman and Williams, 2012) and meet regulatory capital requirements (Beatty andLiao, 2014). A positive coefficient on BELIEFSt indicates that an increase in quarter t sentiment is associated with more futurecharge-offs per dollar of quarter t provision. This association is consistent with managers under (over) provisioning for loanlosses due to unjustified optimism (pessimism) about the future collection of receivables. If managerial sentiment is notassociated with estimates of the loan loss provision, we expect the loan loss provision to reflect only economic funda-mentals, and sentiment should not affect the ratio of COi,tþ1 to LLPi,t (i.e., β1 in Eq. (3a) should be statistically indis-tinguishable from zero).

We replace BELIEFSt with UNEXP_BELIEFSt and EXP_BELIEFSt in Eq. (3b). We expect the coefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt to bepositive. We are also interested in the difference in the coefficients between UNEXP_BELIEFSt and EXP_BELIEFSt. IfEXP_BELIEFSt captures justified beliefs while UNEXP_BELIEFSt measures unjustified beliefs (sentiment), then β1 should besignificantly greater than β2 because, relative to justified beliefs, unjustified beliefs lead to greater estimation error in theprovision.

A potential challenge with using realized future charge-offs is that it is not a perfect proxy for an unbiased expectation offuture charge-offs (i.e. realized charge-offs is the sum of both expected and unexpected future charge-offs). If the un-expected component is uncorrelated with the regressors in the models (3a) and (3b), then the coefficient estimates will beunbiased. However, if the unexpected component is correlated with any of the regressors, then the coefficient estimatescould be biased.

Thus, as an alternative approach to testing H2, we adapt our primary LLP models in Eqs. (2a) and (2b) by adding futurecharge-offs, the interaction of future charge-offs with sentiment, and abnormal returns in quarter tþ1 ( +BHARi t, 1) as modelregressors. If sentiment has the predicted effect on the relation between future charge-offs and current period sentiment

10 We winsorize all bank-level variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The Appendix provides definitions and data sources for all variables used in ourtests.

Predicted Relation between Loan Loss Provision and Future Charge-offs

Loan Loss Provisioni,t = + Charge-offsi,t+1 + errori,t

SENTIMENTt LLPt COt+1 β

High 100 × (γ - θ) 100 (γ - θ)

None 100 × γ 100 γ

Low 100 × (γ + θ) 100 (γ + θ)

Fig. 2. Predicted relation between loan loss provision and future charge-offs. Loan Loss Provisioni,t¼αþβ Charge-offsi,tþ1þerrori,t.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–5034

(H2), we expect sentiment to interact negatively with future charge-offs. We include abnormal returns in quarter tþ1( +BHARi t, 1) as a proxy for the unexpected component of future charge-offs, which allows us to control for correlation be-tween the unexpected component of future charge-offs and other regressors. This approach is similar to prior research thatuses future returns to mitigate measurement error arising from future events that affect future outcomes but were notanticipated in period t (Collins et al., 1994). Although Collins et al. (1994) use returns to partial out the unexpected com-ponent of future earnings, we use returns to partial out the unexpected component of future charge-offs, using the analogouslogic that unexpected future charge-offs should be reflected in future stock returns.

To illustrate our expectation for how sentiment will affect the relation between the loan loss provisions and futurecharge-offs, consider the following (simplified) model:

α β= + − ++Loan Loss Provision Charge offs errori t i t i t, , 1 ,

where the period t loan loss provision estimated for bank i (LLPi,t) is related to its period tþ1 charge-offs. If there is nomanagerial sentiment in period t when the provision is estimated, then we expect β to reflect a “normal” positive asso-ciation between the provision and future charge-offs (γ). If, however, the provision is estimated during a period of high (low)sentiment, then we expect the association between the provision and future charge-offs to be γ θ γ θ− ( + ), where θ is greaterthan zero. Fig. 2 illustrates this point. When there is no managerial sentiment in period t, a dollar increase in future charge-offs corresponds to an increase in LLPi,t of γ . When managerial sentiment is high (low) in period t, a dollar increase in futurecharge-off corresponds to an increase in the loan loss provision that is less than (greater than) γ , consistent with managersunder (over) provisioning for future charge-offs. To examine this association, we estimate the following pooled OLS models:

β β β β β β β β

β β β β β β β β

β β ε

= + × + + + + Δ + Δ + Δ

+ Δ + + Δ + + + + + Δ

+ Δ + + ( )

+ + + + −

− − − −

LLP BELIEFS CO BELIEFS CO BHAR NPA NPA NPA

NPA LOAN EBP CO CAPR ALW GDP

URATE CSRET

SIZE 1

4a

i t t i t t i t i t i t i t i t

i t i t i t i t i t i t t

t t i t

, 0 1 , 1 2 3 , 1 4 , 1 5 , 1 6 , 7 , 1

8 , 2 9 i,t 1 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 1 14 , 1 15

16 17 ,

β β β β β

β β β β β β β β

β β β β β β β ε

= + _ × + _ × + _ + _

+ + + Δ + Δ + Δ + Δ + + Δ

+ + + + + Δ + Δ + + ( )

+ +

+ + + − − −

− −

LLP UNEXP BELIEFS CO EXP BELIEFS CO UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS

CO BHAR NPA NPA NPA NPA LOAN

EBP CO CAPR ALW GDP URATE CSRET

SIZE

1 4b

i t t i t t i t t t

i t i t i t i t i t i t i t

i t i t i t i t t t t i t

, 0 1 , 1 2 , 1 3 4

5 , 1 6 , 1 7 , 1 8 , 9 , 1 10 , 2 11 i,t 1 12 ,

13 , 14 , 15 , 1 16 , 1 17 18 19 ,

If sentiment affects loan loss provisions, then we expect β1 in Eq. (4a), the coefficient on the interaction betweenmeasures of sentiment in quarter t (BELIEFSt) and charge-offs in quarter tþ1 (COi,tþ1), to be negative and significant. Anegative coefficient indicates that a unit increase in charge-offs in quarter tþ1 is associated with less of an increase in thequarter t provisionwhen managers exhibit positive (or high) sentiment in quarter t as compared to quarters when managersexhibit negative (or low) sentiment. If managerial sentiment is not associated with estimates of the loan loss provision, weexpect the loan loss provision to reflect only economic fundamentals, and sentiment should not affect the relation betweenLLPi,t and COi,tþ1 (i.e., β1 in Eq. (4a) should be statistically indistinguishable from zero).

We replace BELIEFSt with UNEXP_BELIEFSt and EXP_BELIEFSt in Eq. (4b). Here, we expect the coefficient on the interactionbetween COi,tþ1 and UNEXP_BELIEFSt to be negative. We are also interested in the difference between the coefficients forUNEXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1 and EXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1. As before, if EXP_BELIEFSt captures justified beliefs, and UNEXP_BELIEFStcaptures mangerial sentiment, then we expect the coefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1 to be more negative than thecoefficient on EXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1.

H3 posits that our predictions from H1 and H2 will hold in a sample of private banks. We base this prediction on thenotion that managers of private banks do not have the opportunities or incentives to exploit prevailing investor sentiment totemporarily increase stock price or meet analysts’ expectations. To test H3, we conduct the previously outlined tests using asample of private banks.

3.4. Sample

Our primary sample consists of COMPUSTAT bank-quarter observations with the necessary data to construct our modelvariables for the period 2002:4 to 2013:2. The resulting data set includes 19,840 bank-quarter observations. We construct

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 35

our measure of sentiment using data from the Duke/CFO Magazine Business Outlook Survey available at www.cfosurvey.org.We obtain market returns from CRSP and macro variables from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.11

In constructing our sample of private banks, we use call report data from SNL Financial. We identify public ownershipusing data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, FDIC, and SNL Financial. Specifically, we determine whether a bank(or its parent) has ever been publicly traded. Then, we restrict our private bank sample to banks that are private and forwhich all variables required by our regression models are available. Finally, consistent with Ng and Roychowdhury (2013),who suggest that S-corporations have different loss provisioning processes, we remove S-corporations from the sample. Ourfinal private bank sample consists of 107,959 private bank-quarters over the period 2005 to 2011.

4. Results

4.1. Sentiment and macroeconomic factors

As discussed in Section 3, we measure managerial sentiment in two ways. Our first proxy is managers’ beliefs aboutfuture firm prospects (based on CFO survey responses). Our second proxy is the component of managers’ beliefs that isunexplained by (or orthogonal to) macroeconomic fundamentals. We obtain our second measure by estimating Eq. (5). Asshown in Table 1, the results indicate that macroeconomic fundamentals explain about 90% of the variation in managers’beliefs (adjusted R-squared is 0.907). This result is consistent with our expectation that economic fundamentals are theprimary driver of managers’ beliefs. It is also comparable with the results in Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006), who reportadjusted R-squared values between 0.80 and 0.90 in similar regressions using consumer sentiment. We derive our secondproxy for sentiment (UNEXP_BELIEFSt) as the set of residuals obtained from this regression. Fig. 1 plots both BELIEFSt andUNEXP_BELIEFSt over our sample period.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the key dependent and independent variables over the sample period. Panel Areflects variables in Eq. (1) and Panel B reflects the variables used in tests of H1 and H2. We find that LLPi,t has a mean of0.002 indicating that, on average, the loan loss provision is 0.2% of lagged total loans. Panel B also indicates that the dis-tributional statistics for charge-offs are identical to those for LLPi,t; on average, charge-offs are also 0.2% of total loans. Thisconsistency is not surprising as the loan loss provision is meant to capture future charge-offs. The means (standard de-viations) for BELIEFSt and UNEXP_BELIEFSt are 0.659 (0.046) and 0.000 (0.008), respectively. These statistics further highlightthe difference in the variances of BELIEFSt and UNEXP_BELIEFSt, and reinforce the notion that managers’ unexpected (orunjustified) beliefs constitute a relatively small portion of their total beliefs.

Table 3 presents both Pearson and Spearman correlations between the variables used in our analyses. Panel A tabulatesthe correlations among the macroeconomic variables used in the Table 1 regression and Panel B tabulates the correlationsamong the variables used in the regression analyses to test H1 and H2. We report Pearson correlations above the diagonaland Spearman correlations below. We focus on the Pearson correlations and make the following observations. First, Panel Aindicates that BELIEFSt are significantly correlated with seven of the macroeconomic variables included as independentvariables in Eq. (1). The magnitudes of these correlations are substantial; of the significant correlations, the absolutemagnitudes range from 0.295 to 0.817. Second, in Panel B we find that the unconditional correlation between LLPi,t andBELIEFSt is negative (�0.345) and statistically significant, although the univariate correlation between LLPi,t andUNEXP_BELIEFSt is not statistically distinguishable from zero. Third, consistent with prior research, we find a positive cor-relation between LLPi,t and each of the changes in non-performing assets (ΔNPAi,tþ1, ΔNPAi,t, ΔNPAi,t�1, and ΔNPAi,t�2).Finally, the correlation between LLPi,t and COi,t (charge-offs), 0.788, is significant as expected.

4.3. Results for H1

Table 4 presents the results from estimating several models derived from Eqs. (2a) and (2b). In these models we regressLLPi,t on our measures of sentiment and various control variables. In model (i) we use BELIEFSt as our measure of sentimentand include the control variables from Eq. (2a). In model (ii), we estimate Eq. (2b) by replacing BELIEFSt with UNEXP_BELIEFStand EXP_BELIEFSt. In models (iii) and (iv) we add lagged measures of sentiment BELIEFSt�1 and UNEXP_BELIEFSt�1 to Eqs.(2a) and (2b), respectively. We add these measures to account for the relation between lagged investor sentiment anddiscretionary accruals documented in Simpson (2013). In Table 4 (and the remaining tables), we include year fixed effectsand estimate coefficients using within-year variation in managerial beliefs because we believe large temporal shifts inbeliefs are more likely attributable to changes in fundamentals than changes in sentiment. We exclude the year fixed effectsin robustness tests (discussed in Section 5.4). We cluster standard errors at the firm level (Petersen 2009).

Consistent with H1, the results of estimating model (i) indicate a negative relation between LLPi,t and BELIEFSt. More

11 We obtain consumption-to-wealth ratio data from Sydney Ludvigson, available at http://www.econ.nyu.edu/user/ludvigsons/.

Table 1Macroeconomic determinants of managerial beliefs.

β β β β β β β β β β Σβ Σβ ε= + + + + + + + + + + + + ( )BELIEFS DIV DEF YLD GDP CONS LABOR URATE CPIQ CAY LEADS LAGS3 5t t t t t t t t t t j k t0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Variables BELIEFSt

Coeffic. p-Value

MKTRETt �0.001 0.397DEFt 0.062 0.020YLD3t 0.073 0.005GDPt 0.001 0.895CONSt 0.040 0.008LABORt �0.022 0.200URATEt �0.046 0.073CPIQt 0.002 0.360CAYt �0.451 0.734Constant 0.562 o0.001Adjusted R-squared 0.907Observations 44

Table 1 reports the results from regressions of managerial beliefs on macroeconomic factors. The sample consists of quarterly observations from 2002 to 2013. Our measure of managerial beliefs (BELIEFS) is derivedfrom the Duke University/CFO Magazine Business Outlook Survey. See Appendix A for variable definitions and measurements. p-values are computed using heterskedasticity-robust standard errors. Lead and laggedmacroeconomic determinants are untabulated.

P.Hribar

etal./

Journalof

Accounting

andEconom

ics63

(2017)26

–5036

Table 2Descriptive statistics.

Variable N Mean Std. Dev. Q1 Median Q3

Panel A:

BELIEFSt 44 0.660 0.046 0.631 0.655 0.699MKTRETt 44 2.139 9.070 �1.964 2.670 7.728DEFt 44 1.163 0.502 0.890 1.000 1.290YLD3t 44 1.564 1.715 0.120 0.985 2.705GDPt 44 0.434 0.669 0.254 0.563 0.808CONSt 44 1.002 0.760 0.858 1.149 1.297LABORt 44 0.232 0.746 �0.183 0.265 0.590URATEt 44 6.839 1.909 5.098 6.033 8.598CPIQt 44 0.596 1.107 0.020 0.616 1.486CAYt 44 �0.017 0.010 �0.023 �0.017 �0.010

Panel B:

BELIEFSt 19,840 0.659 0.046 0.631 0.656 0.698UNEXP_BELIEFSt 19,840 0.000 0.008 �0.003 0.000 0.004EXP_BELIEFSt 19,840 0.659 0.046 0.636 0.653 0.691LLPi,t 19,840 0.002 0.003 0.000 0.001 0.002ΔNPAi,tþ1 19,840 0.001 0.007 �0.001 0.000 0.002ΔNPAi,t 19,840 0.001 0.007 �0.001 0.000 0.002ΔNPAi,t�1 19,840 0.001 0.006 �0.001 0.000 0.002ΔNPAi,t�2 19,840 0.001 0.006 �0.001 0.000 0.002SIZEt�1 19,840 7.432 1.493 6.398 7.100 8.137ΔLOANi,t 19,840 0.018 0.049 �0.008 0.012 0.035EBPi,t 19,840 0.006 0.004 0.004 0.006 0.008COi,t 19,840 0.002 0.003 0.000 0.001 0.002CAPR1i,t�1 19,840 0.119 0.033 0.097 0.113 0.135ALWi,t�1 19,840 0.016 0.008 0.011 0.014 0.018COi,tþ1/LLPi,t 18,593 1.036 1.777 0.212 0.653 1.189COi,tþ1234/LLPi,t 18,593 4.929 7.494 1.616 3.153 5.539BHARi,tþ1 17,415 �0.017 0.163 �0.093 �0.020 0.058BHARi,tþ1234 17,284 �0.069 0.303 �0.228 �0.069 0.089ΔGDPt 19,840 0.930 0.785 0.787 1.106 1.334ΔURATEt 19,840 0.050 0.375 �0.158 �0.061 0.152CSRETt 19,840 0.391 2.143 �1.280 0.196 2.474

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for variables used in our tests. The sample consists of bank-quarter observations from 2002 to 2013. Panel A reflectsvariables in Eq. (1) and Panel B reflects the variables used in tests of H1 and H2. All firm-specific variables have been winsorized at the 1st and 99thpercentiles. See Appendix A for variable definitions and measurements.

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 37

specifically, the coefficient on BELIEFSt is �0.005 (po0.001). The signs of the estimated coefficients for the firm-levelcontrol variables are generally consistent with findings in prior literature, and the adjusted R-squared for model (i) is 0.696.Results from estimating model (ii) are similar to those from model (i). Again, consistent with our hypothesis, the coefficienton UNEXP_BELIEFSt is negative (�0.004) and statistically significant (p¼0.018). The results for models (iii) and (iv) arecomparable to those in models (i) and (ii) and indicate that even after controlling for lagged sentiment, our con-temporaneous measures of sentiment are negatively associated with loan loss provision estimates. Finally, as expected, thecoefficient for EXP_BELIEFSt in model (iv) is negative (�0.005) and significant (po0.001) indicating that the component ofmanagerial beliefs that is explained by macroeconomic fundamentals is also associated with loan loss provision estimates.

To provide a sense of the economic significance of the effect of sentiment on the loan loss provision, we estimate theeffect of a one standard deviation change in unexpected beliefs. We find that a one standard deviation change in unexpectedbeliefs is associated with a 1.60% decrease in the provision. This is comparable in magnitude to the effect of the tier 1 capitalratio (CAPR1), a previously documented earnings management incentive, where a one standard deviation increase in tier1 capital reduces the provision by 1.65% (untabulated). In terms of its effect on net income, our results indicate that a onestandard deviation change in sentiment is associated with a 1.04% change in income before extraordinary items for theaverage bank in our sample.12 Overall, the results in Table 4 are consistent with a negative and significant contemporaneousrelation between loan loss provisions and managerial sentiment that is robust to controlling for bank-level factors that priorresearch documents as being associated with loan loss provisions as well as macro-level control variables shown to in-fluence either loan loss provisions or measures of sentiment.

12 Mean income before extraordinary items for the sample is 0.002. In assessing economic magnitudes, we calculate the after-tax effect on net income,we assume a tax rate of 35%.

Table 3Correlations.

Panel A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1 BELIEFSt 1 0.204 �0.817 0.627 0.576 0.763 0.295 �0.609 0.305 0.160 – – – – – – – – –

2 MKTRETt 0.031 1 �0.287 �0.024 0.511 0.451 0.137 0.144 0.203 �0.357 – – – – – – – – –

3 DEFt �0.755 0.019 1 �0.335 �0.731 �0.849 �0.206 0.299 �0.323 0.041 – – – – – – – – –

4 YLD3t 0.596 �0.161 �0.306 1 0.101 0.291 0.117 �0.827 0.150 0.435 – – – – – – – – –

5 GDPt 0.377 0.365 �0.404 �0.042 1 0.773 0.156 �0.085 0.264 �0.123 – – – – – – – – –

6 CONSt 0.706 0.155 �0.571 0.405 0.356 1 0.147 �0.269 0.554 �0.035 – – – – – – – – –

7 LABORt 0.255 0.101 �0.141 0.110 0.110 0.186 1 �0.091 �0.061 �0.305 – – – – – – – – –

8 URATEt �0.662 0.192 0.465 �0.881 �0.048 �0.369 �0.124 1 �0.122 �0.678 – – – – – – – – –

9 CPIQt 0.230 �0.107 �0.184 0.147 �0.082 0.386 �0.007 �0.145 1 �0.089 – – – – – – – – –

10 CAYt 0.211 �0.325 �0.011 0.575 �0.086 0.099 �0.243 �0.608 �0.100 1 – – – – – – – – –

Panel B 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

1 BELIEFSt 1 0.174 0.984 �0.345 �0.129 �0.153 �0.154 �0.147 �0.024 0.214 0.188 �0.286 �0.021 �0.189 �0.049 0.036 0.749 �0.666 0.5652 UNEXP_BELIEFSt 0.196 1 �0.006 0.003 0.032 0.019 0.036 0.011 �0.010 0.006 0.024 0.005 �0.042 �0.001 �0.002 �0.135 0.023 �0.003 �0.0903 EXP_BELIEFSt 0.959 �0.041 1 �0.351 �0.137 �0.159 �0.163 �0.151 �0.022 0.216 0.187 �0.291 �0.014 �0.192 �0.049 0.061 0.757 �0.675 0.5914 LLPi,t �0.412 0.027 �0.434 1 0.100 0.198 0.224 0.249 0.100 �0.209 �0.203 0.788 �0.075 0.391 �0.069 �0.160 �0.253 0.252 �0.2925 ΔNPAi,tþ1 �0.056 0.034 �0.062 0.073 1 0.158 0.187 0.126 �0.011 0.056 �0.033 �0.033 �0.047 �0.179 �0.057 �0.120 �0.195 0.289 �0.2326 ΔNPAi,t �0.098 0.030 �0.099 0.158 0.168 1 0.145 0.172 �0.012 0.069 �0.047 �0.020 �0.050 �0.133 �0.005 �0.174 �0.209 0.277 �0.2257 ΔNPAi,t�1 �0.118 0.036 �0.126 0.185 0.186 0.154 1 0.139 �0.013 �0.048 �0.066 0.136 �0.065 �0.046 0.007 �0.117 �0.185 0.261 �0.2038 ΔNPAi,t�2 �0.139 0.013 �0.140 0.203 0.150 0.174 0.143 1 �0.010 �0.072 �0.078 0.169 �0.065 �0.002 �0.001 �0.095 �0.142 0.207 �0.1819 SIZEt�1 �0.038 �0.011 �0.037 0.139 0.008 0.011 0.013 0.013 1 �0.026 0.309 0.119 �0.174 0.113 0.027 0.014 �0.012 0.005 �0.01210 ΔLOANi,t 0.287 0.000 0.295 �0.217 0.071 0.042 �0.056 �0.086 �0.034 1 0.196 �0.292 0.082 �0.281 �0.091 0.055 0.133 �0.060 0.17411 EBPi,t 0.183 0.032 0.177 �0.084 �0.035 �0.050 �0.072 �0.074 0.327 0.231 1 �0.198 0.139 �0.097 �0.059 0.143 0.211 �0.160 0.24612 COi,t �0.379 0.008 �0.397 0.690 �0.048 �0.022 0.098 0.120 0.249 �0.382 �0.105 1 �0.069 0.578 0.021 �0.091 �0.157 0.114 �0.22013 CAPR1i,t�1 �0.051 �0.041 �0.044 �0.085 �0.100 �0.099 �0.106 �0.094 �0.145 0.033 0.147 �0.059 1 0.042 �0.023 0.046 0.036 �0.114 0.05714 ALWi,t�1 �0.244 0.005 �0.258 0.364 �0.190 �0.141 �0.072 �0.029 0.141 �0.308 0.006 0.522 0.108 1 0.149 0.004 �0.021 �0.103 �0.04015 COi,tþ1/LLPi,t �0.132 0.004 �0.141 0.083 �0.063 0.030 0.019 0.021 0.202 �0.186 �0.032 0.250 �0.050 0.207 1 �0.031 �0.029 �0.006 �0.06516 BHARi,tþ1 �0.007 �0.115 0.011 �0.078 �0.106 �0.150 �0.114 �0.084 0.016 0.074 0.140 �0.047 0.056 0.020 �0.029 1 0.152 �0.097 0.08617 ΔGDPt 0.620 0.141 0.577 �0.253 �0.141 �0.170 �0.154 �0.136 �0.027 0.195 0.231 �0.214 0.005 �0.046 �0.101 0.093 1 �0.678 0.64718 ΔURATEt �0.390 �0.055 �0.383 0.200 0.302 0.279 0.281 0.231 0.003 �0.034 �0.125 0.083 �0.145 �0.136 0.010 �0.101 �0.405 1 �0.54919 CSRETt 0.508 �0.077 0.538 �0.341 �0.244 �0.251 �0.232 �0.219 �0.026 0.222 0.280 �0.262 0.062 �0.006 �0.132 0.103 0.610 �0.479 1

Table 3 provides Pearson (above) and Spearman (below) correlation for variables used in our regression analysis. Panel A reflects variables in Eq. (1) and Panel B reflects the variables used in tests of H1 and H2. Allfirms specific variables have been wisorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Bold typeface indicates significance at the 1% level and italic typeface indicates significance at the 5% level. See Appendix A for variabledefinitions and measurements.

P.Hribar

etal./

Journalof

Accounting

andEconom

ics63

(2017)26

–5038

Table 4Test of H1: the effect of managerial sentiment on loan loss provision estimates.

β β β β Δ β Δ β Δ β Δ β

β Δ β β β β β Δ β Δ β ε

= + _ + _ + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + ++ − − −

− −

LLPi t UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS NPA NPA NPA NPA SIZE

LOAN EBP CO CAPR ALW GDP URATE CSRET

,

1

t t i t i t i t i t i t

i t i t i t i t i t t t t i t

0 1 2 3 , 1 4 , 5 , 1 6 , 2 7 , 1

8 , 9 , 10 , 1 11 , 12 , 1 13 14 15 ,

Variables LLPi,t

(i) (ii) (iii) (iv)

Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value

BELIEFSt �0.005 o0.001 �0.005 o0.001UNEXP_BELIEFSt �0.004 0.009 �0.004 0.008EXP_BELIEFSt �0.005 o0.001 �0.006 o0.001BELIEFSt�1 �0.002 0.033UNEXP_BELIEFSt�1 �0.002 0.241ΔNPAi,tþ1 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001ΔNPAi,t 0.072 o0.001 0.072 o0.001 0.072 o0.001 0.072 o0.001ΔNPAi,t�1 0.024 o0.001 0.024 o0.001 0.024 o0.001 0.024 o0.001ΔNPAi,t�2 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001 0.025 o0.001SIZEi,t�1 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001ΔLOANi,t 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001EBPi,t �0.025 0.001 �0.025 0.001 �0.025 0.001 �0.025 0.001COi,t 0.833 o0.001 0.833 o0.001 0.833 o0.001 0.833 o0.001CAPR1i,t�1 0.001 0.164 0.001 0.165 0.001 0.167 0.001 0.164ALWi,t�1 �0.009 0.027 �0.009 0.027 �0.009 0.028 �0.009 0.027ΔGDPt �0.000 0.002 �0.000 0.002 �0.000 0.002 �0.000 0.003ΔURATEt �0.000 0.027 �0.000 0.020 �0.000 0.005 �0.000 0.010CSRETt 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001 0.000 o0.001Constant 0.003 o0.001 0.003 o0.001 0.004 o0.001 0.004 o0.001

Year Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes YesAdjusted R-squared 0.696 0.696 0.696 0.696Observations 19,840 19,840 19,840 19,840

Change in LLP from a one standard deviation change inUNEXP_BELIEFS

�1.60% �1.60%

Change in net income from a one standard deviation change in UN-EXP_BELIEFS (assuming 35% tax rate)

�1.04% �1.04%

Table 4 reports the results of tests examining the effect of beliefs (BELIEFS) and unexplained beliefs (UNEXP_BELIEFS) on loan loss provision estimates (LLP).The sample consists of bank-quarter observations from 2002 to 2013. All variables are defined in Appendix A. All firm-specific have been winsorized at the1st and 99th percentiles. p-values are computed using standard errors clustered by firm (one-tailed test if a prediction is made and sign is consistent withthe prediction and two-tailed test otherwise).

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–50 39

4.4. Results for H2

Table 5 reports the results of our first tests of H2. In model (i) we find that the coefficient on BELIEFSt is statisticallyindistinguishable from zero. However, in model (ii) when we replace BELIEFSt with UNEXP_BELIEFSt and EXP_BELIEFSt, wefind that the coefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt is positive and significant (po0.10) whereas the coefficient on EXP_BELIEFSt isinsignificant. Testing for equality of coefficients confirms that the coefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt is significantly more po-sitive than the coefficient on EXP_BELIEFSt (p¼0.034), as predicted. These results are consistent with higher sentimentleading to a greater level of charge-offs per dollar of loan loss provision, whereas justified beliefs do not have the sameeffect. In terms of economic magnitude, we find that the effect of sentiment is similar to the effects of earnings managementincentives on the provision (e.g. Bushman and Williams, 2012; Beatty and Liao, 2014). Specifically, a one standard deviationincrease in sentiment is associated with one-quarter (one-year) ahead charge-offs that are 2.25% (3.25%) higher per dollar ofprovision, a one standard deviation change in earnings before the provision is associated results in a 5.54% (3.41%) increasein one-quarter (one-year) ahead future charges-offs per dollar of provision, and a one standard deviation change in the tier1 capital ratio results in a 6.31% (6.12%) increase in one-quarter (one-year) ahead future charges-offs per dollar of provision.

As an additional test of H2, we modify Eqs. (3a) and (3b) by replacing COi,tþ1 with COi,tþ1234, which is the sum of charge-offs for quarters tþ1, tþ2, tþ3, and tþ4. Under the incurred loss model, the timing difference between provisioning forloan losses and charging off actual loans can vary, but guidance from bank regulators suggests that banks provision forcharge-offs expected to occur within a relatively short time horizon, such as one year (Ronen and Ryan, 2009). In model (iii)

Table 5Test of H2: the effect of managerial sentiment on the relation between future charge-offs and loan loss provision estimates.

β β β β β ε= + _ + _ + + ++ −CO LLP UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS EBP CAPR/ 1i t i t t t i t i t i t, 1 , 0 1 2 3 , 4 , 1 ,

Variables COi,tþ1/LLPi,t COi,tþ1234/LLPi,t

(i) (ii) (iii) (iv)

Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value

BELIEFSt �0.137 0.760 4.361 0.016UNEXP_BELIEFSt 2.919 0.055 20.012 0.002EXP_BELIEFSt �0.218 0.619 3.944 0.053EBPi,t �14.515 o0.001 �14.357 0.001 �42.820 0.036 �42.013 0.039CAPR1i,t�1 �1.984 o0.001 �1.982 o0.001 �9.148 o0.001 �9.139 o0.001Constant 1.012 o0.001 1.040 o0.001 1.584 0.243 1.727 0.204Test: β14β2 3.137 0.034 16.07 0.008

Year Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes YesAdjusted R-squared 0.015 0.015 0.046 0.046Observations 18,593 18,593 18,593 18,593

Change in COi,tþn/LLPi,t from a one standard deviation change inUNEXP_BELIEFS

2.25% 3.25%

Change in COi,tþn/LLPi,t from a one standard deviation change inEBP

�5.54% �3.41%

Change in COi,tþn/LLPi,t from a one standard deviation change inCAPR1

�6.31% �6.12%

Table 5 reports the results of tests examining the effect of unexplained beliefs (UNEXP_BELIEFS) on the relation between the ratio of future charge-offs (CO)and loan loss provision estimates (LLP) at time t. The sample consists of bank-quarter observations from 2002 to 2013. All variables are defined in AppendixA. All firm-specific have been winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. p-values are computed using standard errors clustered by firm (one-tailed test if aprediction is made and sign is consistent with the prediction and two-tailed test otherwise).

P. Hribar et al. / Journal of Accounting and Economics 63 (2017) 26–5040

we find that the coefficient on BELIEFSt is positive and significant (po0.05) as predicted, and in model (iv) we find that thecoefficients on both UNEXP_BELIEFSt and EXP_BELIEFSt are positive and significant (p¼0.002 and 0.053, respectively). Thecoefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt (20.012) is also significantly greater than the coefficient on EXP_BELIEFSt (3.944), consistentwith UNEXP_BELIEFSt being a more direct measure of managerial sentiment than EXP_BELIEFSt.

Table 6 presents the results of the alternative tests of H2 (estimating Eqs. (4a) and (4b)). In regression models (i) and (ii),we interact quarter tþ1 charge-offs (COi,tþ1) with quarter t sentiment, BELIEFSt and UNEXP_BELIEFSt, respectively. Consistentwith our prediction that the positive association between loan loss provisions and future charge-offs is attenuated when theprovision is estimated during periods of high managerial sentiment, we find that the coefficient on the interaction termbetween charge-offs and sentiment is negative and significant in both models. For model (i) the coefficient estimate is�0.789 (p¼0.001) and for model (ii) the coefficient estimate is �4.134 (po0.001). In model (ii), we find that the coefficienton EXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1 is also negative. However, the magnitude of the coefficient is only one-fourth of the magnitude ofthe coefficient on UNEXP_BELIEFSt�COi,tþ1 and the difference is statistically significant (p¼0.002), suggesting thatUNEXP_BELIEFSt is a more direct proxy for managerial sentiment than EXP_BELIEFS. The results are even stronger in models(iii) and (iv) when extending the window for future charge-offs to one year (i.e. COi,tþ1234). We find that the coefficients onthe interactions between future charge-offs and quarter t measures of sentiment are negative and highly significant atconventional levels (po0.01).13 Taken together, the results in Table 6 provide evidence consistent with managerial senti-ment affecting estimates of the loan loss provision and suggest that our measures of sentiment are not simply proxies formacroeconomic fundamentals.

4.5. Results for H3

Table 7 provides the results for tests of H3a and H3b. Panel A reports the results of re-estimating the models from Table 4using the sample of private banks (H3a). To the extent that managers are subject to sentiment, we also expect to find anegative relation between LLPi,t and sentiment among private banks. However, we do not expect to observe a significant

13 In untabulated tests we re-estimate the models in Table 6 after dropping the control variable for abnormal returns, BHAR. The results are very similarto those reported in Table 6 and all inferences remain unchanged.

Table 6Alternative test of H2: the effect of managerial sentiment on the relation between future charge-offs and loan loss provision estimates.

β β β β β β β β Δ

β Δ β Δ β Δ β β Δ β β β

β β Δ β Δ β ε

= + _ × + _ × + _ + _ + + +

+ + + + + + + +

+ + + + +

+ + + + +

− − − −

−

LLP UNEXP BELIEFS CO EXP BELIEFS CO UNEXP BELIEFS EXP BELIEFS CO BHAR NPA

NPA NPA NPA SIZE LOAN EBP CO CAPR

ALW GDP URATE CSRET

1

i t t i t t i t t t i t i t i t

i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t

i t t t t i t

, 0 1 , 1 2 , 1 3 4 5 , 1 6 , 1 7 , 1

8 , 9 , 1 10 , 2 11 , 1 12 , 13 , 14 , 1 15 ,

16 , 1 17 18 19 ,

Variables LLPi,t

(i) (ii) (iii) (iv)

Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value Coeffic. p-Value