Do ethanol prices in Brazil follow Brent price and international gasoline price parity?

-

Upload

marcelo-cavalcanti -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

1

Transcript of Do ethanol prices in Brazil follow Brent price and international gasoline price parity?

at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433

Contents lists available

Renewable Energy

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/renene

Technical note

Do ethanol prices in Brazil follow Brent price and international gasoline priceparity?

Marcelo Cavalcanti*, Alexandre Szklo, Giovani MachadoEnergy Planning Program, Graduate School of Engineering, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Centro de Tecnologia, Bloco C, Sala 211, Cidade Universitária, Ilha do Fundão,Rio de Janeiro, RJ 21941-972, Brazil

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 9 September 2011Accepted 23 November 2011Available online 21 December 2011

Keywords:Brazilian ethanolFuel pricesPetroleum correlation

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ55 21 2562 8760; faE-mail addresses: [email protected] (M. C

(A. Szklo), [email protected] (G. Machado).

0960-1481/$ e see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Ltd.doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.11.034

a b s t r a c t

After the introduction of flexfuel vehicles in Brazil, hydrated ethanol and gasohol (gasoline blended withanhydrous ethanol at an average volumetric proportion of 75:25) became basically perfect substitutes. Thispaper tests the hypothesis that hydrated ethanol prices follow the price of gasohol in Brazil (opportunitycost of ethanol). In addition it tests the hypothesis that gasoline ex-refinery price variation in Brazil tends tofollow the variation in the Brent crude spot price. By testing these two hypotheses simultaneously, thisstudy test a more general hypothesis that expresses the influence of Brent spot prices on hydrated ethanolprices in Brazil (second order effect). Findings indicate that a variation in the Brent spot price does notautomatically cause a variation in gasoline ex-refinery prices in Brazil. The best correlation found wasbetween the Brent price fluctuation and the six-month average gasoline ex-refinery price. In case ofgasohol and ethanol pump prices, this relation is elastic over the long and short-term in the Brazilianmarket. However, the short-term elasticity is greater than that over the long run.

� 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In a previous study published in Renewable Energy, the taxationof the liquid fuels consumed by light duty vehicles in Brazil wasanalyzed [1]. This study highlighted the need to better investigatethe mechanisms through which international crude oil price canaffect Brazil’s ex-refinery gasoline prices and, hence, the opportu-nity cost and price of hydrated ethanol.

Actually, the prices of automotive fuels affect not only energyand transportation policies, but also economic, financial and socio-environmental policies of countries. In general, fuel prices arecomposed of: i) ex-refinery price, ii) taxes, and iii) wholesale andretail margins. The ex-refinery price is formed by the costs ofacquiring inputs and the cost structure of the refiner, in addition tothe net margin of the refiner/importer. The ex-refinery price plustaxes levied on the refiner/importer forms the wholesale price ofthe refiner/importer. The refiner/importer sells its products towholesalers, which add their gross margin (costs excluding thosefor purchase of the fuel, taxes and subsidies, plus net margin) andthe taxes and subsidies applicable to the sector. They then chargethis price to retailers (service stations), which also add their grossmargin, taxes and subsidies, to form the final pump price.

x: þ55 21 2562 8777.avalcanti), [email protected]

All rights reserved.

According toChouinard and Perloff [2], andDavidson [3] changesin automotive fuel prices can be mainly explained market funda-mentals, such as average consumer income, per capita number ofvehicles, oil price, and taxes. In addition, the prices of oil products(ex-taxes and ex-subsidies), even with different fuel specifications,are self-regulated by supply and demand in the world [4].Notwithstandingoil price dynamics has becomemore complex thanever as speculation could be playing a major role, currently, indefining pricemovements in addition tomarket fundamentals [4,5].

Furthermore, government pricing policies can affect the conver-gence with international prices, in structural form (with taxes andsubsidies) or conjunctural form (through delay in the pass-throughfrom international to domestic prices), as discussed by Coady et al.[6]. Yet, exchange rate variations between the domestic and referencemarketalsoaffect theconvergenceofnational and internationalprices.

Currently there is a wide range of automotive fuel pricingpolicies in the world. According to GTZ [7], these policies fall intothree broad categories: i) ad hoc decisions; ii) automatic adjust-ments via formulas; and iii) market prices.

1. Ad hoc decisions occur in countries that adjust the prices due tomacroeconomic conditions and/or internal political consider-ations. These adjustments are normally made directly by thegovernmentor throughcompaniescontrolleddirectlyor indirectlythereby. The adjustments are generally based on non-transparentcriteria andoccur at irregular intervals, leading to amismatchwith

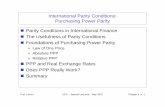

Fig. 1. Evolution of demand for liquid fuels used in light vehicles in Brazil since theintroduction of flexfuel vehicles. Sources: [23,24].

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433424

the international price. China, India and Indonesia are examples ofcountries that use this mechanism to adjust their prices [7].

2. Automatic adjustments follow a certain degree of regularityand are based on formulas defined by the government ornational oil company. The advantage of this mechanism is that,albeit with some lag, prices follow global price trends.However, according to Coady et al. [6], these formulas are oftensuspended due to opposition to price adjustments. Indeed,according to Baig et al. [8], in regulated environments, peopletend to observe governmental control and then blame thegovernment for price increases. Examples of countries that useautomatic adjustment mechanisms are South Africa, Bolivia,Chile, Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Pakistan and Peru [6].

3. Most OECD countries follow the third policy mechanism(market prices), where prices derive from market fundamen-tals and the government restrains its role to taxation [7].1

The adoption of one of these three general mechanisms bya country will imply different macroeconomic, sectorial and fiscaleffects. For example, under the market price system (third mech-anism), a temporary shock in global prices can cause inflationaryeffects, especially when the prices of fuels associated with cargotransport rise [7]. In turn, governments that adopt ad hoc pricingdecisions face lower short-term political vulnerability, because theyare able to smooth out domestic prices. Nevertheless, this decisionpossibly results in mismatches with international prices. Further-more, when price shocks derive from permanent modifications inthe market fundamentals, this price misalignment implies highfiscal impacts until prices are finally adjusted to the new level. Bothtax revenue losses and price increases cause political vulnerability.

The scientific literature still lacks a comprehensive analysis onthis subject. The attempt of Kojima [9] is one of the most recentanalyses related to oil price control in developing countries, whilethe study of Wu et al. [10] analyses the effects of the floating pricemechanism on Taiwan’s gasoline and diesel markets and the reve-nues of state-owned oil company Chinese Petroleum Corporation.

In theory, taxation of fuels should satisfy four main principles: i)fuel prices (without taxation) should cover the production,wholesale and retail costs; ii) some of the revenues raised should

1 Italy, for example, liberalized the prices of automotive gasoline and diesel in1994, permitting the free entry of new suppliers in the national market, aligningdomestic with international prices (in function of the price of oil and operatingcost) [26].

help finance expansion and maintenance of the road network andpublic transit systems; iii) the taxing scheme should seek tointernalize the socio-environmental externalities and encourageenergy-efficient transportation; and iv) the taxation should alsocontribute to general government revenues [7].

The interplay of these principles is particularly complex inBrazil, which was in the 1970s the global pioneer in promotingethanol at large scale as a vehicle fuel, and is today the secondworld producer (38.2% of global production and 30.4% of demand in2008) [11]. Brazil stands apart because of the matchless competi-tiveness of its ethanol as an automobile fuel and the reduced GHGemissions over this fuel’s life cycle [12].

Competition with ethanol for fueling light vehicles in Brazil isrestricted to gasohol (gasoline blended with anhydrous ethanolcurrently at an average volumetric proportion of 75:25) andcompressed natural gas.2 However, this competition has gainedimportance in the last decade since the introduction of flexfuelvehicles in the country. The flexfuel technology gives motorists thefreedom of choice to use only hydrated ethanol or gasohol, ora mixture of these fuels in any concentration. In 2009, flexfuelvehicles accounted for 37.1% of the country’s light vehicle fleet [13].

Therefore, it is worth analyzing the price evolution of hydratedethanol in Brazil in order to evaluate if ethanol prices followgasoline price parity (opportunity cost of ethanol). In addition, thisstudy statically tests the hypothesis that gasoline ex-refinery pricevariations in Brazil tend to follow Brent spot price variations.3 Bytesting these two hypotheses simultaneously, it was evaluateda more general hypothesis that expresses the influence of the Brentcrude spot price on the fuel ethanol price in Brazil (second ordereffect). Therefore, this study also aims at helping policymakersevaluating the influence of the international petroleum market onthe country’s automotive fuels market.

2. Ethanol-gasoline market competition in Brazil

Fuel prices in Brazil have not been directly determined byadministrative decision of the government since 2002. Since 2002,oil products prices in Brazil are free to float according to interna-tional market prices [14]. However, as the state-controlled oilcompany Petrobras keeps a dominant position in the domesticmarket, it became a price-setter.

In setting its ex-refinery prices, Petrobras considers not only therelevant international parity, but also its impacts on socioeconomicsensitive oil products prices in the Brazilian market (its major andtarget market). Petrobras clearly indicates this fact by stating that“Although Petrobras’ prices for oil products are based on interna-tional prices, in periods of high international prices or sharpdevaluation of the Real, Petrobras may not be able to adjust itsprices in Reais sufficiently to maintain parity with internationalprices” [15]. Kojima [11] provides more details on this issue byconcluding that: “If there is a national oil company or an oilcompany with some state involvement that is also a price-setter(because it controls a large share of the market), the governmentmay send signals to the company to keep prices low. Petrobras, thenational oil company in Brazil, plays such a role.” Thereby, Petro-bras smooths out international price variations [15].

While ethanol-dedicated cars in Brazil date from the late 1970swhen they were first introduced as part of the Proálcool program

2 Brazilian regulations do not permit sale of passenger cars burning diesel.Notwithstanding, some light utilities vehicles focused on passenger mobility, suchas SUV and pick-up, do run based on diesel.

3 In other words, this study test the hypothesis that Brazil follows the thirdtypology of automotive fuel pricing as defined in this section (“market prices”).

Fig. 2. Logarithms of Brent and ex-refinery gasoline prices.

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433 425

(established by the government in response to the two oil crises),the free choice of consumers between ethanol and gasohol isrelatively recent, dating from the introduction of flexfuel cars in2003. This technology allows the engine to run on pure hydratedethanol, gasohol (also called gasoline C) or any mixture of both. Thegrowing share of these cars in the nation’s fleet has had a significantimpact on demand for hydrated ethanol, allowing it to competedirectly against gasohol and raising demand for it, as shown inFig. 1.

According to ANFAVEA [13], Brazil’s automaker trade associa-tion, in 2009 approximately 88.2% of light vehicles sold were flex-fuel cars, while 7.4% of the market was held by gasoline cars.4 Thedemand by flexfuel cars between ethanol and gasoline C dependson a series of factors. According to Correia [16], a complex set offactors defines the relative competitiveness of ethanol at theregional level and hence the division of demand by flexfuel vehiclesbetween gasoline and ethanol. The main problem brought by thehuge popularity of flexfuel cars is the risk of volatility in thegasoline market, in function of uncertainty about the levels ofexportation of ethanol and sugar by the country in relation todomestic output [17]. For instance, in 2010 the sugarcane harvestdeclined substantially due to climate factors [18], and the risinginternational price of sugar caused less of the crop to be allocated toethanol [19]. The result was a sharp rise in the domestic price ofhydrated ethanol, prompting consumers to switch to gasoline C andcausing the country to become a net importer of gasoline afteryears as a net exporter [20].

3. Testing price correlation between Brent crude oil andBrazilian gasoline

The statistical analysis carried out here is based on Brent crudeprice series disclosed by EIA [21] and ex-refinery gasoline priceseries for Brazil [20,22].5 The statistical tests were run in Gretlsoftware (Gnu Regression, Econometrics and Time-series Library),

4 Light commercial vehicles running on diesel account for the remaining 4.5%,with the following classifications: Utility, Cargo Pickups, and Mixed-Use Pickups[13].

5 The monetary values were converted into constant reais (R$) of January 2010,using the PPI index [27] and an exchange rate of R$ 1.78/US$ [25].

which is an effective tool for compiling and interpreting econo-metric data.

The econometric analysis from the direct correlation of thelogarithms is presented in Fig. 2. The log linear model was usedbecause it proved to be superior in the statistical tests to the linearmodel, especially with respect to reducing oscillations.

Fig. 2 shows that both logarithmic series present trends, buttheir dynamics vary (see the behavior between 2003 and mid-2004, and mid-2006 to mid-2008 in the Brent price).

The simple regression model indicates that the price of gasolineis inelastic in relation to that of Brent (0.8060), with R2 of 0.87,which appears to be a good fit. But these results must be viewedwith caution (risk of overestimated significance) because of thepresence of autocorrelation (LM tests). The tests are presented inTable 1.

This regression brings the following results: i) mean of depen-dent variable (gasoline) ¼ 4.13667; ii) standard deviation of dep.var. ¼ 0.322252; iii) sum of squared residuals ¼ 1.01596; iv) stan-dard error of the regression ¼ 0.113403; v) unadjustedR2 ¼ 0.87771; vi) adjusted R2 ¼ 0.87616; vii) degrees offreedom ¼ 79; viii) Durbin-Watson statistic ¼ 0.631781; ix) first-order autocorrelation coefficient ¼ 0.668252; x) log-likelihood ¼ 62.3999; xi) Akaike information criterion ¼ �120.8;xii) Schwarz Bayesian criterion ¼ �116.011; and xiii) Hannan-Quinn criterion ¼ �118.878.

The LM test for autocorrelation can be seen in Table 2.Figs. 3 and 4 confirm that there are relatively long periods of

divergence between the series (see the behavior between 2003 andmid-2004 and again betweenmid-2006 and mid-2008 in the Brentprice).

Findings show that the series are not stationary and are notcointegrated. This requires the use of first differences in the model,instead of simple regression, as presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 1Regression of ex-refinery gasoline price on Brent price (logarithms).

Coefficient Std. error t-ratio p-value

Constant 0.884504 0.137158 6.449 8.28E-09Brent 0.806064 0.0338516 23.81 8.54E-038

Table 2LM test for autocorrelation for logarithmic regression of ex-refinery gasoline price on Brent price.

Up to order 12 - Up to order 2 - Up to order 1 -

Null hypothesis No autocorrelation No autocorrelation No autocorrelationTest statistic LMF ¼ 6.46943 LMF ¼ 31.3044 LMF ¼ 63.1827With p-value ¼P(F(12,67) > 6.46943)

¼1.73891e-007¼P(F(2,77) > 31.3044)¼1.12396e-010

¼P(F(1,78) > 63.1827)¼1.18259e-011

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433426

This regression brings the following results: i) mean of depen-dent variable (gasoline differential) ¼ 0.0140611; ii) standard devi-ation of dep. var. ¼ 0.0629537; iii) sum of squared residuals ¼0.312611; iv) standard error of the regression ¼ 0.0633075; v)unadjusted R2¼ 0.00153; vi) adjusted R2¼�0.01127; vii) degrees offreedom ¼ 78; viii) Durbin-Watson statistic ¼ 2.02927; ix) first-order autocorrelation coefficient¼�0.0387725; x) log-likelihood¼108.278; xi) Akaike information criterion ¼ �212.556; xii) Schwarz

Fig. 3. Correlation curve of Brent and gasolin

Fig. 4. Comparison of the price of gasoline and the pric

Bayesian criterion ¼ �207.792; xiii) Hannan-Quinn criterion ¼�210.646.

The first difference model appears to be well specified, becausethere is no autocorrelation. Thus it is possible to assess the signif-icance of the regression coefficient. The first difference modelshows there is no effective relation between Brent price andgasoline ex-refinery price in Brazil, based on the data for the2002e2008 period. The prediction is not informative about

e prices in Brazil, by simple regression.

e obtained by simple regression on the Brent price.

Table 3Regression of first differences of ex-refinery gasoline and Brent prices (logarithms).

Coefficient Std. error t-ratio p-value

Constant 0.0145344 0.0072092 2.0161 0.04723D_Brent �0.0319826 0.092512 �0.3457 0.73049

Table 4LM test for autocorrelation for logarithmic regression of ex-refinery gasoline on Brent pr

Up to order 12 -

Null hypothesis No autocorrelationTest statistic LMF ¼ 0.745921With p-value ¼P(F(2,76) > 0.159176)

¼0.85313

Fig. 5. Comparison of differences (logarithms) of gasoline prices: historical data versus dadifferences of ex-refinery gasoline prices between two consecutive periods.

Fig. 6. Correlation of dispersion from differences of gasoline and Brent prices. Note: d_gasoli

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433 427

gasoline ex-refinery prices. This confirms the information thatPetrobras did not establish an immediate pass-through of inter-national prices to domestic prices. The significant correlation foundbetween the two prices is spurious. The correlation only capturesthe presence of trends in the series, but these trends are notcommon, i.e., there is no effective relation between the series.

ices in first differences model.

Up to order 2 - Up to order 1 -

No autocorrelation No autocorrelationLMF ¼ 0.159176 LMF ¼ 0.115418¼P(F(2,76) > 0.159176)¼0.85313

¼P(F(1,77) > 0.115418)¼0.734984

ta plotted from Brent prices in the first difference model. Note: d_gasoline is the log

ne is the log differences of ex-refinery gasoline prices between two consecutive periods.

Table 5Summary output of the first difference model with semiannualmean.

Regression statistics

Multiple R 0.697546434R Square 0.486571027Adjusted R Square 0.45954845Standard Error 0.096954907Observations 21

Table 6Anova of the first difference model with semiannual mean.

DF SS MS F Significance F

Regression 1 0.169261841 0.169261841 18.00609239 0.000439621Residual 19 0.178604825 0.009400254Total 20 0.347866667

Table 7Coefficient and statistical tests of the first difference model with semiannual mean.

Coefficients Standard error t Stat P-value Lower 95% Upper 95% Lower 95.0% Upper 95.0%

Intercept 0.026329296 0.022332593 1.178962777 0.252966696 �0.020413359 0.073071952 �0.020413359 0.073071952d_brent 0.482639981 0.113740088 4.243358622 0.000439621 0.244579242 0.72070072 0.244579242 0.72070072

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433428

Therefore, the relation between the series is not significant and theGretl software does not specify a relation between them in thedispersion graph (see Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 6 shows that the price-setting strategy for domestic gasolinemarket of Petrobras prevents correlation on a monthly basis of theprice of Brent crude and the Brazilian price of gasoline. From thisperspective, Petrobras does not adjust the domestic gasoline pricemerely according to the international market price mechanism(third mechanism defined in Section 1). As a matter of fact, itsopportunity cost considers not only the international prices, butalso the structure and conditions of its major and target market,Brazil, which shows different income and price elasticities, whencompared to other petroleum markets.

Since gasoline ex-refinery prices in Brazil have not been definedby direct government control (or ad hoc, using the terminology ofSection1), it remains toanalyze towhatmeasuregasolineex-refinery

Table 8Residual output of the first difference model with semiannual mean.

Observation Predicted d_gasolina Residuals

1 0.257996487 0.1420035132 0.103551693 0.0564483073 0.069766895 0.0602331054 �0.046066701 �0.0639332995 �0.036413901 �0.1235860996 0.050461295 �0.2304612957 0.089072494 �0.0490724948 0.040808496 0.1691915049 0.026329296 �0.00632929610 0.079419694 �0.08941969411 0.122857293 �0.00285729312 0.089072494 0.05092750613 0.084246094 0.07575390614 0.069766895 0.02023310515 0.011850097 �0.01185009716 0.002197297 0.02780270317 0.137336492 �0.06733649218 0.127683692 �0.08768369219 �0.103983498 0.04398349820 �0.152247497 0.12224749721 0.166294891 �0.036294891

price variations in theBrazilianmarket adjust,with some lag, toBrentprice variations (the secondpricingmechanismdefined in Section 1).

To perform this test, an attempt was made to smooth out thefluctuations of the Brent price and their interference in the reali-zation price of Brazilian gasoline. In this case the average of theprices charged every half year was used. This estimate took intoconsideration the econometric relation between the variations (ordifferences) of the logarithms of the six-month means of theseprices in the period from 1999 to 2009.

Interestingly, on a semiannual basis, the first difference model iswell specified, because there is no autocorrelation. Therefore, it ispossible to evaluate the significance of the regression coefficient(see Tables 5e8 and Fig. 7):

The results presented in Tables 5e8 and Fig. 7 indicate there wasa relation between the spot market Brent price and the realizationprice of gasoline in Brazil in the 1999e2009 period. The bestrepresentation of the historical relationship between these twoprice series is given by the equation below:

Pgasoline ¼ Exp ln gasolineðt�1Þ þ Constant� �io

n h

þ Cd Brent* ln Brentt � ln Brentðt�1Þ

where Pgasoline ¼ ex-refinery price of gasoline; ln_gasolinei ¼logarithm of ex-refinery gasoline price in period “i”;Constant ¼ fixed coefficient of regression, which represents thepoint where the vertical axis is crossed by the forecast curve, whenthe independent variable (difference of Brent price logarithmsbetween two periods) is zero; Cd_Brent ¼ slope of log difference ofBrent prices; ln_Brenti ¼ logarithm of Brent price in period “i”.

Any regression model minimizes the mean prediction error.Thus, the values found should reflect the tendency of the gasolineprice, given the Brent price. For example, if the Brent price does notdecline (or declines very slightly), the ex-refinery price trend ofgasoline is upward.

Thus, Brent price correlate with gasoline ex-refinery price inthe Brazilian market, through an adjustment with a lag of six-month. The final (pump) price of gasoline in Brazil is deter-mined with the introduction of costs, margins, freight charges andtaxes. The ex-refinery price refers to base gasoline (as it leaves therefinery),6 while in an intermediate step (distribution, 20e25%anhydrous ethanol is blended in, changing the physical andchemical characteristics, which then becomes gasohol (or gasolineC). This blend competes with hydrated ethanol to fuel flexfuel carsin Brazil.

Section 4 compares the pump prices of gasohol and ethanol andtests whether they are correlated. If so, this will indicate theinfluence of the opportunity cost on the formation of the price ofethanol in Brazil.7 By extension, based on the results of the presentsection, this will show the influence (albeit with a lag) of variationsof the Brent spot price on ethanol price variations in the Brazilianmarket.

6 Known as gasoline A in Brazil.7 This influence was pointed out by Scandifio, Francescato and Wang [28e30].

None of these authors measures it, however.

Fig. 7. Comparison of the log differences of gasoline prices: historical data versuspoints plotted from Brent prices in the first difference model with semiannual mean.Note: In the axes of Fig. 7, both d_gasoline and d_brent are, respectively, the logarithmsof the differences of ex-refinery gasoline and Brent prices between two consecutivesperiods.

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433 429

4. Testing price correlation between gasohol and hydratedethanol in the Brazilian fuel market

The statistical analysis performed here is based on the series ofgasohol and ethanol prices, according to ANP [20], since the entryof flexfuel vehicles in 2003 through the end of 2009. This study ranthe statistical tests of the logarithms of the average monthly pumpprices in Brazil.

Fig. 8 shows that the prices of gasohol and hydrated ethanolpresent tendencies, but their dynamics appear different, with moreextreme peaks and troughs for ethanol than for gasohol (see thebehavior in 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2009).

The statistical tests of the simple regression model indicate thatthe price of ethanol can be considered isoelastic in relation to thatof gasohol (coefficient ¼ 0.98), with R2 of 0.85 (Fig. 9).

Despite the good fit observed in Fig.10, the results must again beviewed with caution (overestimated significance) due to the

Fig. 8. Prices of gasohol and hydrated

presence of autocorrelation (LM tests) e see Tables 9 and 10 andFigs. 10 and 11.

This regression brings the following results: i) mean of depen-dent variable (ethanol) ¼ 0.208297; ii) standard deviation of dep.var. ¼ 0.210133; iii) sum of squared residuals ¼ 0.522814; iv)standard error of the regression ¼ 0.0798485; v) unadjustedR2 ¼ 0.85735; vi) adjusted R2 ¼ 0.85561; vii) degrees of freedom ¼82; viii) Durbin-Watson statistic ¼ 0.260316; ix) first-order auto-correlation coefficient ¼ 0.87659; x) log-likelihood ¼ 94.1417; xi)Akaike information criterion ¼ �184.283; xii) Schwarz Bayesiancriterion ¼ �179.422; xiii) Hannan-Quinn criterion ¼ �182.329.

Figs. 11 and 12 confirm that there were periods when the rela-tion between the series shifted, although these are not long lasting.To avoid potential spurious regression, the non-cointegrationbetween the series was tested. Findings show that the two seriesare not stationary, but are cointegrated. This indicates a stable long-term underlying relation between the logarithms of the prices ofthe variables. The modeling of the relation between gasohol andethanol prices, corrected for autocorrelation, was determined bythe dynamic model. The autocorrelation tests suggest a secondorder model to better capture the correlation between the series,according to the following equation:

Pethanol ¼ ExpnConstantþ

hgasohol*

�ln gasoholt

�

þ gasohol*1�ln gasoholðt�1Þ

�

þ gasohol*2�ln gasoholðt�2Þ

�

þ ethanol*1ðln ethanolðt�1ÞÞþ ethanol*2ðln ethanolðt�2ÞÞ

io

where Pethanol ¼ pump price of hydrated ethanol;Constant¼ fixed coefficient of the regression, which represents thepoint where the vertical axis is crossed by the forecast curve, whenthe independent variable (log difference of Brent prices betweentwo periods) is zero; gasohol ¼ coefficient of the regression rep-resenting the short-term effect on the logarithms of the ethanolprice based on the logarithm of the gasoline price in the sameperiod; gasohol1 ¼ coefficient of the regression representing theeffect on the logarithms of the price of ethanol based on the

ethanol in Brazil. Sources: [23,25].

Fig. 10. Logarithms of hydrated ethanol prices: historical versus plotted from regression with gasohol.

Fig. 9. Logarithms of final prices of gasohol and hydrated ethanol.

Table 9Logarithmic regression of hydrated ethanol on gasohol.

Coefficient Std. error t-ratio p-value

Constant �0.482794 0.0323268 �14.9348 <0.00001Brent 0.982173 0.0442427 22.1996 <0.00001

Table 10LM test for autocorrelation for logarithmic regression of hydrated ethanol on gasohol.

Up to order 12 -

Null hypothesis No autocorrelationTest statistic LMF ¼ 29.375With p-value ¼P(F(12,70) > 29.375)

¼1.29256e-022

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433430

logarithm of the gasoline price in the immediately precedingperiod; gasohol2 ¼ coefficient of the regression representing theeffect on the logarithms of the ethanol price based on the logarithmof the gasoline price in two previous periods; ethanol1¼ coefficientof the repression representing the effect on the logarithms of theethanol price based on the ethanol price in the immediatelypreceding period; ethanol2 ¼ coefficient of the repression

Up to order 2 - Up to order 1 -

No autocorrelation No autocorrelationLMF ¼ 177.115 LMF ¼ 246.795¼P(F(2,80) > 177.115)¼4.11925e-030

¼P(F(1,81) > 246.795)¼2.61851e-026

Fig. 11. Logarithms of hydrated ethanol and gasohol prices with least squares fit.

Fig. 12. Logarithms of ethanol prices: historical versus plotted from regression with gasohol in the second order model.

Table 11Logarithmic regression of hydrated ethanol on gasohol prices, in the second ordermodel.

Coefficient Std. error t-ratio p-value

Constant �0.0819595 0.0279625 �2.9311 0.00446Gasohol 1.64268 0.263939 6.2237 <0.00001Gasohol1 �2.02075 0.484764 �4.1685 0.00008Gasohol2 0.528288 0.324765 1.6267 0.10794Ethanol1 1.28038 0.103665 12.3511 <0.00001Ethanol2 �0.413272 0.111949 �3.6916 0.00042

Table 12LM test for autocorrelation of logarithmic regression of hydrated ethanol on gasohol pri

Up to order 12 -

Null hypothesis No autocorrelationTest statistic LMF ¼ 1.11294With p-value ¼P(F(12,64) > 1.11294)

¼0.365689

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433 431

representing the effect on the logarithms of the ethanol price basedon the ethanol price in the two previous periods;ln_gasoholi ¼ logarithms of the gasohol prices in period “i”;ln_ethanoli ¼ logarithms of ethanol prices in period “i”.

The regression below is not autocorrelated in the residuals, at 5%significance, as can be seen in the LM autocorrelation tests (seeTables 11 and 12).

This regression brings the following results: i) mean of depen-dent variable (ethanol) ¼ 0.212692; ii) standard deviation of dep.var. ¼ 0.210442; iii) sum of squared residuals ¼ 0.0798758;

ces in the second order model.

Up to order 2 - Up to order 1 -

No autocorrelation No autocorrelationLMF ¼ 2.64296 LMF ¼ 0.150473¼P(F(2,74) > 2.64296)¼0.0778606

¼P(F(1,75) > 0.150473)¼0.699182

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433432

iv) standard error of the regression ¼ 0.0324191; v) unadjustedR2 ¼ 0.97773; vi) adjusted R2 ¼ 0.97627; vii) F-statistic (5, 76) ¼667.417 (p-value < 0.00001); viii) Durbin-Watson statistic ¼1.95562; ix) first-order autocorrelation coefficient ¼ 0.0198282;x) Durbin’s h ¼ 0.495836; xi) log-likelihood ¼ 167.941; xii) Akaikeinformation criterion ¼ �323.882; xiii) Schwarz Bayesiancriterion ¼ �309.442; xiv) Hannan-Quinn criterion ¼ �318.085.

Fig. 12 shows a much better fit between the series in this modelthan in the simple correlation model. Hence, there is a correlationbetween the prices of gasohol and hydrated ethanol.

However, the econometric relation obtained is complex. Tointerpret this regression, it is worth considering the gasohol pricecoefficients as short-term effects. Therefore, an increase of 1% in theprice of gasohol is reflected in an increase of 1.6% in the price ofethanol in the same month. However, in the next month, this samegasohol price increase will represent a 2.02% decline in the price ofethanol. The long-term effect (LTE) of gasohol to hydrated ethanolis given by the following equation:

LTE¼ðgasoholþgasohol1þgasohol2Þ=½1�ðethanol1þethanol2Þ�

Substituting the values yields (1.64e2.02 þ 0.528)/(1e1.28 þ 0.413) ¼ 1.1307, in other words, an elastic effect ofgasohol on ethanol prices.

5. Final comments

The statistical tests performed in this study show the complexrelationship between the spot price of Brent and the prices ofgasohol and ethanol in the Brazilian automotive fuels market. Thecorrelation between Brent spot price and Brazil’s gasoline ex-refinery price indicated that a variation in the former does notautomatically affect the latter. The best correlation is that whichsoftens the fluctuation of Brent prices by considering the six-monthaverage. That evidence suggests that the Petrobras, although it doesnot determine the ex-refinery price of gasoline on an ad hoc basis,does adjust this price in relation to variations in the spot marketprice of Brent crude, with a time lag.

In the case of the relation between the pump prices of gasoholand ethanol, this relation is elastic in both the long and short run.However, this elasticity declines over time. Thus, a rise in the priceof gasohol at first leads to a more than proportional increase in theprice of ethanol, but this proportion decreases gradually. Thisevidence suggests that part of the market made up of flexfuel carowners, at a second moment, reacts to the higher price of ethanoland switches back to gasohol.

Finally, it is worth noting that this study focused on the averagefuel prices for Brazil as a whole, which is highly influenced by theweight of the state of São Paulo in ethanol consumption. Theexistence of regional disparities in prices, costs and margins indi-cates the need for specific research to know the degree of regionaldisparities in the country. In addition, it would be important toelucidate whether an evolution in fuel distribution logistics wouldaffects the relative prices of ethanol and gasohol.

Also, Petrobras frequently states that it looks for smoothing theinternational price volatility, which is in harmonywith our findings.However, similar tests should be made to different periods in orderto evaluate if there is a general “six-month lag rule of adjustment”or this finding concerns only to the period considered in our study.

In addition, the result that proves the relationship between ex-refinery gasoline price and ethanol price in Brazil between 2003and 2009 is valid only because, during this period, therewas no lackof supply in the ethanol market. This situation changed in 2010,when sugar price spikes (which changed the preferences of sugar-cane producers between ethanol and sugar) allied to an extended

dry season impacting sugarcane crop in Southern Brazil and theincrease of ethanol demand, created the condition of short ethanolsupply. Under this new circumstance, ethanol and ex-refinerygasoline prices decoupled and the rule of opportunity costs basedon gasoline prices seen in this paper was no longer valid. Instead,the opportunity cost for ethanol in 2010 was, apparently, based onsugarcane prices rather than on gasoline prices. Therefore, it isworth expanding our analysis to this new period, when a shortethanol supply and a sugar price spike altered the relationshipshown in our study. However, there is no comprehensive data yet toperform this new analysis at this moment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eduardo Pontual for his contribution during earlierstages of this paper. We also acknowledge the financial supportfrom the National Research Council (CNPq). Finally, we thankseveral anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on theoriginal draft. The conclusions expressed in this manuscript aresolely our own.

References

[1] Cavalcanti M, Szklo A, Machado G, Arouca M. Taxation of automobile fuels inBrazil: does ethanol need tax incentives to be competitive and if so, to whatextent can they be justified by the balance of GHG emissions? RenewableEnergy 2012;37:9e18.

[2] Chouinard H, Perloff J. Incidence of federal and state gasoline taxes, Wash-ington State University. Economics Letters Elsevier 2004;83:55e60.

[3] Davidson P. Crude oil prices: "Market fundamentals" or speculation? Journalof Post Keynesian Economics. Available at: http://bus.utk.edu/econweb/faculty/davidson/challenge%20oilspeculation9wordpdf.pdf; 2008 [accessedin June 21, 2011].

[4] Kaufmann R. The role of market fundamentals and speculation in recent pricechanges for crude oil. Energy Policy 2011;39:105e15.

[5] Büyüksahin B, Harris J. Do speculators drive crude oil futures prices? TheEnergy Journal 2011;32:167e202.

[6] Coady D, Gillingham R, Ossowski R, Piotrowski J, Tareq S, Tyson J. Petroleumproduct subsidies: costly, inequitable, and rising, international monetary fund(IMF). Fiscal Affairs Department; 2010, February.

[7] GTZ. International fuel prices, Deutsche Gesellschaft Für Technische Zusam-menarbeit, Eschborn e GTZ. Available at: 6th ed., http://www.gtz.de/de/dokumente/gtz2009-en-ifp-full-version.pdf; 2009 [accessed in august 20].

[8] Baig T, Mati A, Coady D, Ntamatungiro J. Domestic petroleum product pricesand subsidies: recent development and reform strategies. Washington:International Monetary Fund (IMF); 2007. IMF Working paper 07/71.

[9] Kojima M. Government response to oil price volatility: experience of 49developing countries. Available at: The World Bank, http://www.signallogic.net/government-response-to-oil-price-volatility.html; 2011. accessed in July31.

[10] Wu J, Huang Y, Liu C. Effect of floating pricing policy: an application of systemdynamics on oil market after liberalization. Energy Policy 2011;39:4235e52.

[11] EIA. International energy statistics: biofuels production and consumption of2008, energy information administration. Available at: U.S. Department ofEnergy, http://www.eia.doe.gov/cfapps/ipdbproject/IEDIndex3.cfm?tid¼79&pid¼79&aid¼1; 2010 [accessed in December 15].

[12] Wang M, Wu M, Huo H. Life-cycle energy and greenhouse gas emissionimpacts of different corn ethanol plant types. IOP Publishing, EnvironmentalResearch Letters, Center for Transportation Research; 2007. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/2/2/024001.

[13] ANFAVEA. Vendas internas no atacado de nacionais por tipo de produto ecombustível. Statistical data available at: Associação Nacional dos Fabricantesde Veículos Automotores (ANFAVEA), http://www.anfavea.com.br/; 2010[Retrieved in November 2010].

[14] Brazil, Law 10.453/02: Dispõe sobre subvenções ao preço e ao transporte doálcool combustível e subsídios ao preço do gás liqüefeito de petróleo - GLP, edá outras providências, Brasília; 2002 [accessed in July 2, 2011].

[15] Petrobras, Risk factors, Prospectus supplement (to prospectus dated August14, 2002), Morgan Stanley, Bear Stearns, 19e32.

[16] Correia E. Mercado de Gasolina: Impacto da introdução dos veículos flexfuel,Resumo Estratégico Petrobras; 2005, July. Rio de Janeiro.

[17] Correia E, A Retomada do Uso de Álcool Combustível no Brasil, Master’s thesisin applied economics, FEA/UFJF e Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, 2007,December.

[18] Conab. Acompanhamento da Safra Brasileira de Cana-de-Açúcar: Safra 2010/2011. Available at: Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento (Conab), http://www.conab.gov.br/OlalaCMS/uploads/arquivos/11_01_06_09_14_50_boletim_cana_3o_lev_safra_2010_2011.pdf; 2011 [accessed in February].

M. Cavalcanti et al. / Renewable Energy 43 (2012) 423e433 433

[19] Brazil, Alta do açúcar noexterior vai favorecer balança comercial, dizMinistério daAgricultura.PortalBrasil.Available at:http://www.brasil.gov.br/noticias/arquivos/2010/11/05/alta-do-acucar-no-exterior-vai-favorecer-balanca-comercial-diz-ministerio-da-agricultura; 2011 [accessed in February].

[20] ANP. Dados Estatísticos de Preços e Vendas de combustíveis. Agência Nacionaldo Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis (ANP), dados disponíveis em,www.anp.gov.br; 2010 [accessed in December 17].

[21] EIA. Spot prices: crude oil in dollars per barrel. Available at: Energy Infor-mation Administration, U.S. Department of Energy, http://www.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_spt_s1_d.htm; 2010 [accessed in October 22].

[22] CONFAZ. Atos Cotepe e Convênios ICMS, Conselho Nacional de PolíticaFazendária (CONFAZ). Available at: http://www.fazenda.gov.br/confaz; 2010[accessed in May 17].

[23] ANP. Anuário Estatístico Brasileiro do Petróleo e do Gás Natural e 2010.Available at: Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis(ANP), http://www.anp.gov.br/?pg¼31286; 2010 [accessed in November 19].

[24] MAPA. Mistura Carburante - Variação de Percentual. Ministério da Agricultura,Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA). Available at: http://www.agricultura.gov.br/portal/page?_pageid¼33,3900254&_dad¼portal&_schema¼PORTAL; 2010[accessed in August 19].

[25] BCB. Taxa de Câmbio. Banco Central do Brasil (BCB). Available at: http://www4.bcb.gov.br/pec/taxas/port/ptaxnpesq.asp?id¼txcotacao; 2010 [accessed inNovember 15].

[26] Di Giacomo M, Piacenza M, Turati G. Are “Flexible” taxation mechanismseffective in stabilizing fuel prices? An evaluation considering the Italian fuelmarkets. Universita Degli Studi Di Torino, Department of Economics andPublic Finance “G.Prato”; 2009, October. Working paper n. 7.

[27] BLS, Commodity data: all commodities (producer price index - PPI),United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS),Available at: http://www.bls.gov/data/home.htm, accessed in August 19,2010.

[28] Scandiffio M. Análise prospectiva do álcool combustível no Brasil e cenários2004e2024, Campinas, São Paulo, Doctoral thesis, Campinas State University,School of Mechanical Engineering, Campinas, 2005.

[29] Francescato M. O Impacto dos Mercados de Açúcar e Petróleo Americano naVolatilidade do Açúcar Brasileiro, Master of Science thesis, IBMEC São Paulo.School of Economics and Administration, 2006.

[30] Wang X. The impact of fuel ethanol on motor gasoline market: modelingthrough a system of structural equations, Master of Science thesis, Universityof Missouri-Columbia, 2008.