Dissertation export bans food security Tanzania_SDengler

-

Upload

solene-dengler -

Category

Documents

-

view

156 -

download

1

Transcript of Dissertation export bans food security Tanzania_SDengler

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE

On the rationale to use export bans for food

security: the case of Tanzania

Candidate number: 77951

MSc Environment and Development

Wordcount: 9988

29 August 2013

2

Abstract

Export bans were used by many countries in 2008 to counteract rising food prices. Since

then, the debate on the rationale for discretionary government intervention in

agricultural markets has revived. This paper analyses the motivations for using export

bans from the perspective of the Tanzanian government, using a mixed-method analysis

including interviews and newspaper articles. Three different arguments from the

literature that support export bans as a second-best choice were investigated. Overall,

there was strong support for political incentives after 2010, while more neutral factors

such as information and market failures played a key role beforehand. There was

evidence of a strategic interaction between the private and the public sector that led to a

vicious circle between imperfect information, speculative behaviour and ad hoc

interventions from the state. Moreover, the repeated use of export bans despite evidence

of their ineffectiveness appeared to be partly due to a lack of constructive policy

dialogue between the various stakeholders involved in the process.

3

Table of contents

I Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5

II Literature review ....................................................................................................................... 8

Market and institutional failures ............................................................................................... 8

Information constraints ........................................................................................................... 10

Political economy .................................................................................................................... 12

III Case study and methodology .................................................................................................. 16

Case study ............................................................................................................................... 16

Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 18

IV Analysis and discussion ......................................................................................................... 21

Analysis ................................................................................................................................... 21

Discussion ............................................................................................................................... 32

V Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 34

Appendix 1 – Abbott’s (2010) theoretical framework ................................................................ 36

Appendix 2 – Interview participants ........................................................................................... 37

Appendix 3 – Interview guide ..................................................................................................... 38

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................ 40

4

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the interviewees for making this research possible and my

supervisor, peers and family for their invaluable support.

5

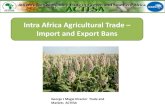

I Introduction

Export bans were used by many countries in 2008 to counteract rising food prices. Since

then, there has been an on-going debate on the rationale for discretionary government

intervention in agricultural markets (Demeke et al. 2011, p.208; Gouel 2013, pp.2–3). In

the context of this debate and given that the frequency of food crisis is expected to

increase in the future, it is of crucial importance to understand why governments use

export bans (hereinafter EBs) to ensure food security and whether they are effective.

This dissertation will focus on the impetus to use EBs in a small developing country, as

the consequences have been studied in-depth in the literature (Mitra & Josling 2009;

World Bank 2009; Sharma 2011; Porteous 2012; MAFAP 2013, pp.183–192).

The choice of analysing the question from the perspective of a small developing country

is motivated by the fact that they have in general been depicted as the victims from

beggar-thy-neighbour-policies in times of food crisis (Bouët et al. 2010; McMahon

2013, chap.6). However, the fact that a number of developing countries regularly

implement EBs shows that there must be internal motivations for using this policy tool.

This dissertation will analyse these from the perspective of the Tanzanian government,

using insights from different strands of research to interpret results. Admassie’s (2013)

paper that analyses the rationale of policies implemented in Ethiopia during the last

food crisis has been an inspiration for the research question and the methodology of this

dissertation.

Tanzania is an interesting case study for three reasons. Firstly, the government has

regularly implemented EBs since the beginning of the decade1, which will provide a

longer time frame of analysis than other studies on EBs that have mostly focused on the

crisis in 2008. Secondly, the country has officially embraced liberalisation and is seen

as the future main provider of maize in the region, which seems to be a contradiction to

the use of EBs. Thirdly, Tanzania amidst other African countries, committed at an

official G8 meeting in May 2012 (G8 Cooperation Framework 2012) to refrain from

using EBs in the future.

1 EBs have been mostly imposed on maize and the analysis will concentrate on this staple crop.

6

The literature describes a variety of economic, socio-political and institutional factors

that can warrant the use of EBs (Mitra & Josling 2009, pp.3–4; Abbott 2010, p.9;

Rausser & Roland 2010, pp.105–106). This dissertation will contribute to the literature

by undertaking an empirical study to analyse three possible explanations for the use of

EBs. The first two are described in the literature on price stabilisation, namely market

and institutional failures and political economy. The third argument that governments

may not choose the optimal alternative because of information failures or lack of

knowledge has been inspired by the literature on policy learning (Heclo 1974; Sabatier

1999; Strydom et al. 2010; Maxwell et al. 2013).

Three specific research questions were derived to analyse the question of why the

government of Tanzania used EBs for food security:

1) Was the use of EBs justified by market and institutional failures?

2) Was the use of EBs an informed decision?

3) To what extent was the decision to use EBs influenced by political actors?

This paper argues that EBs constituted a second-best choice in the short term from the

government perspective given a number of distortions in the economy, the inefficiency

of institutional mechanisms and political pressures. This is in line with Rodrik’s (1992)

argument that drastic trade reforms might not be the best choice in the short run in

developing countries.

The approach in this dissertation was to keep an open mind about the possible factors

leading to EBs in Tanzania. As the purpose was not to prove a particular theory, a

qualitative methodology that gives more flexibility for new insights to arise from the

data was chosen here. The analysis was conducted using triangulation of primary data

collected through interviews and secondary data collected from online newspapers, in

addition to, published and grey literature. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first

time that this type of data analysis has been used in the literature on EBs, and the

insights therefore complement the quantitative and theoretical analysis that has

prevailed to date.

7

Overall, this dissertation has shown that there was strong support for the political

economy argument after 2010, while more neutral factors such as information and

market failures played a key role beforehand. There was evidence of a strategic

interaction between the private and the public sector that led to a vicious circle between

imperfect information, speculative behaviour and ad hoc interventions from the state.

Moreover, the repeated use of EBs despite evidence of their ineffectiveness was

probably due to a lack of constructive policy dialogue between the various stakeholders

involved in the process.

The paper will start by describing the relevant literature that applies to this research

question. The second part will describe the case study and the methodology used. The

results will then be presented and discussed and finally, the last chapter will draw

conclusions and suggest possible avenues for future research.

8

II Literature review

This chapter will present theories and studies that are relevant to the analysis of why

EBs were used in Tanzania. The theory of EBs is still in its early stages, which is why

the literature review draws from several research fields that are important for the

analysis to follow. A description of the main three aspects investigated in this paper will

be given, namely market and institutional failures, information constraints and political

economy. This will be based on the literature on stabilisation policy and policy learning.

To conclude this section, detailed hypotheses will be derived and will then be

investigated in Part IV Analysis.

Market and institutional failures

This section will explain why market and institutional failures and the lack of

alternatives in the short term can justify EBs and will outline those that were described

in the literature and are most relevant to the analysis in Tanzania. The identification of

market and institutional failures relevant to the research question is based on Abbott’s

(2010) framework describing “Objectives relevant to stabilisation policy choices” that

can be found in Appendix 1.

There are two possible ways to explain the use of EBs. The first is from an international

perspective, where large exporting countries impose EBs to improve their terms of trade

and small developing countries respond to it to protect their populations from rising

food prices (Bouët et al. 2010; Anderson et al. 2010; McMahon 2013, chap.6). The

general conclusion from this strand is that countries should refrain from using EBs as

the domino effect induced reduces global welfare. However, the second strand of the

literature analyses EBs from an individual country’s perspective and warrants them

given a variety of economic, socio-political and institutional factors (Mitra & Josling

2009, pp.3–4; Abbott 2010, p.9; 25–30).

9

� Market failures

A combination of market failures means that although a country like Tanzania (Ihle et

al. 2010, p.3) can be self-sufficient nationally, the private sector does not supply the

market to optimum effect, and pockets of food insecurity are arising in the country on a

regular basis. These market failures justify discretionary government intervention to

enhance the efficiency of food provision and to protect agents against risk (Abbott

2010; Timmer 2010) as well as price fluctuations (Timmer 2002; Cummings et al.

2006). Timmer (2010) argues that pro-cyclical government intervention can be

explained by the lack of incentives for the private sector to finance the long-term

investments that are essential to enhance the responsiveness of producers to price

signals. Abbott (2010, pp.25–27) warrants stabilisation measures and interventions from

parastatal agencies because of market power from traders, while Gouel and Jean (2012)

emphasize uncertainty as a key reason to protect risk-averse consumers by imposing

taxes on exports.

Both types of market failures have been described in Tanzania. Firstly, physical and

financial limitations have prevented private actors to effectively take over the marketing

of inputs and output (Mahdi 2012, p.2; Musonda & Wanga 2006, p.560; Wolter 2008,

p.3; MAFAP 2013, p.178). This in turn led to poor storage, a concentration of

marketing services in easily accessible areas and a reduction of fertilizer use by farmers

that affected productivity and the capacity to respond to price increases (Musonda &

Wanga 2006, p.567). Secondly, the low price transmission between Tanzania and other

countries (Minot 2011, pp.20–21; Ihle et al. 2010, p.2) gives a high incentive for

arbitrage and therefore both formal and informal trade on the borders. Informal flows

are especially high between Tanzania and Kenya, as the country experiences regular

food shortages and therefore high domestic prices. The combination of high prices

abroad and lack of infrastructure means that external trade is more profitable than

selling to other regions in the country.

10

� Institutional failures

These market failures could arguably be solved by more efficient measures than an EB.

First of all, from a long-term perspective investment in infrastructure or the provision of

safety nets would be necessary to ensure the provision of food to remote areas.

However, to be effective safety nets need to be well-targeted and managed, which is a

lengthy procedure and therefore makes them less suitable as a response to short term

food crisis (Timmer 2010, p.7). The focus will therefore be laid on existing alternatives

that the government had at the time when EBs were used.

One of the alternatives to EBs is to import maize from other countries. However, the

ability to import in the presence of high prices will depend on the budget constraints or

on the size of aid flows in times of food crisis (Abbott 2010, p.29). Marketing boards

and public storage were introduced in African countries to handle market failures but

have been shown to be often ineffective or inefficient (Abbott 2010, p.27). Budgetary

constraints and competition from private traders were some reasons why the National

Food Reserve Agency (NFRA) in Tanzania was often unable to buy stocks from

farmers in sufficient amounts to cover eventual needs, in particular in times of high food

prices (Temu et al. 2010, p.333). Nyange and Wobst (2005) show that interventions

from the NFRA have been ineffective for the support of farmers, since they increased

producer prices during procurement but depressed them during release. They also show

that trade was more effective at reducing price volatility.

The market and institutional failures outlined above could have provided a justification

for the use of EBs in Tanzania. One of the purposes of this dissertation is to see whether

these failures were perceived by officials as important reasons to restrict the export of

food.

Information constraints

This section presents important concepts that will be used to analyse the information

aspect of the decision to use EBs. Information constraints can arise at several stages of

the decision-making process. Firstly, the accuracy of the data used to assess the food

11

security situation in the country is crucial for a sound decision base. Secondly, the

evaluation of alternatives is important to avoid using the same policy tool for situations

that would require different solutions.

Maxwell et al. (2013, p.4) describe the ideal way decisions should be made for

responses to food crisis situations. Their framework comprises the assessment of needs

and a causal analysis of underlying factors, the evaluation of first- and second-best

options and the inclusion of general factors such as logistical capacity or external

funding. However, they present results from a field study that included interviews with

staff in various organisations and conclude that choices were often made on the basis of

past experience or rapid assessments, so that a single policy choice often became a

dominant response in the institutions. Moreover, some authors argue that in African

countries agricultural policy is more ad hoc than planned and evidence-based

(Farrington & Saasa 2002). This could be due to the lack of national research capacities

(Gabre-Madhin & Haggblade 2004). Babu and Mthindi (1995, p.305) give another

explanation, namely that political survival is an essential factor to take into account, as

decision-makers will weigh up the certainty of research findings against the risks

associated with policy change. Strydom et al. (2010) confirm the multitude of factors

that influence decision-making and emphasize that the credibility of the information and

the experts as well as the compatibility of values between scientists and decision-

makers plays a crucial role for the success of communication between them. They also

state that the inclusion of policymakers in the process of knowledge creation is

important for the success of the acceptance of evidence. This draws the link to the

policy learning literature that is concerned with the dimension of collective learning

within institutions, and between institutions and actors in the economy (Rietig 2013).

The focus will be here on the aspect of non-learning that is important for the EB, which

was repeatedly implemented as a policy tool despite evidence of its ineffectiveness.

The phenomenon of non-learning is described by Heclo (1974, p.312) when

assimilation of new knowledge is hindered at the individual or institutional level. This

can be due to limited time or resources (Janis & Mann 1977) so that trial-and-error or

incrementalism (Lindblom 1979) will be preferred to a meticulous examination of

12

different policy alternatives. It can also be due to an unwillingness to learn and therefore

the task of addressing the problem will be delegated to other individuals or in time

(Janis & Mann 1977). This would meet the point from Farrington and Saasa (2002) that

agricultural policy in African countries was often characterized by defensive avoidance

of problems leading to reactive governance (Rietig 2013, p.9). Finally, individual

learning might not be transmitted to the institutional level and this “blocked learning”

can explain why policy change is a lengthy procedure (Zito & Schout 2009). Sabatier

(1999) expressed three hypothetical conditions amongst others under which a

productive dialogue to induce policy change can occur: there must be sufficient

technical resources on both sides to discuss the subject with a common understanding of

the problem, the debate has to occur in an apolitical but prestigious context and it

should be possible to measure the problems on a quantitative scale. Information

constraints and a lack of policy learning could have been reasons for the EB to be used

despite its ineffectiveness, which will be further analysed below.

Political economy

This section introduces political incentives that could have explained the use of EBs,

drawing from the literature on political economy. There is evidence of political motives

influencing interventions in the Tanzanian agricultural sector. Temu et al. (2010, p.324)

argue that maize is politically sensitive and that therefore interventions are more

frequent to ensure its availability than in the case of other crops. Moreover, Therkildsen

(2011, p.28) shows the importance of political motivations to explain the choice of

investments and the size of applied tariffs in rice production in Tanzania.

� Internal influences

The literature on the political economy of trade distortions (for an overview, see

Anderson (2010)) describes two main constituencies that the government takes into

account when making decisions on trade instruments, which are voters and lobbyists.

The main dilemma faced by the government in times of food crisis is between the

perceived need to protect consumers and the negative consequences of abrupt measures

13

for actors in the value chain (Chapoto et al. 2009, p.26). The general perception in the

literature is that decision-makers in developing countries are much more responsive to

needs of the median voter than to lobbying, in contrast to governments in developed

countries (Abbott 2010, p.28; Gawande & Hoekman 2010, p.243). The analysis will

purposely use a stylised view of constituencies for simplification, although it is clear

that within groups of constituencies interests may differ.

The use of EBs goes against predictions of the median voter model, as in Tanzania 75%

of the population depends on agriculture and therefore the majority of voters are also

farmers (FAO 2008). This can be explained by the “urban bias” described in the

literature, whereby African governments would favour urban constituencies - which are

the main beneficiaries from a price reduction due to the EB - at the expense of rural

constituencies (Maxwell 1999, p.3; Bezemer & Headey 2008, pp.1342–1343; Anseeuw

2010, p.248). In fact, farmers do not generally have much power in developing

countries, which has been explained by their lack of income and education (Woolverton

et al. 2010, pp.8–9; Mkunda 2010). However, Bates and Block (2010, pp.317–318)

show that although their lobbying power may be weak because of geographic dispersion

and their large number, these very factors can make farmers very powerful as voters,

which would confirm the median voter model. They show that this especially applies to

countries with competitive elections, which is the case in Tanzania.

As far as traders are concerned, the analysis of Jayne and Tschirley (2010, pp.124–128)

takes the examples of Kenya and Malawi to derive a new theory of strategic interactions

between the private and the public sector explaining discretionary interventions. Their

framework is based on the premises that the values of the private and the public sector

are different, which leads to a lack of trust between them. Moreover, there is imperfect

information so that both parties base their decisions on expectations of the other’s

behaviour. This problem arises particularly in countries where government interventions

are not always based on clear-cut pre-defined rules and where there is a lack of a

consultative process.

14

� External influences

In addition to internal constituencies, external influences from trade partners and donors

could also have played a role in the decision for EBs. As Tanzania is part of two

regional agreements and the WTO, trade partners would be expected to have an

influence on the choice of trade measures (Gawande & Hoekman 2010, p.241).

Regional trade agreements have been proven to impact on the level of protectionism in a

country (Cadot et al. 2010, pp.355–356) and in the case of the EB, trade partners are

likely to protest in particular when they are net importers. However, Gouel (2013)

argues that the choice of policies such as the EB can be individually rational when

countries do not trust each other and when there is a lack of adoption of similar policies.

Moreover, WTO regulations have a clause in article XI that allows “Export prohibitions

or restrictions temporarily applied to prevent or relieve critical shortages of

foodstuffs” (GATT 1994).

Aid has been shown to have a major influence on policies in African countries (Moyo

2009) and various aid actors have been said to play an important role in agricultural

interventions in Tanzania (Cooksey 2012, pp.22–23; Temu et al. 2010, p.334). Major

donors for Tanzania such as USAID or the World Bank have been promoting the

dismantling of EBs so that aid should not have had a major influence on the motivations

to use this policy tool. However, USAID has played a main advisory role for the

government of Tanzania where EBs are concerned, and therefore their perception of the

motivations to apply them is essential. Kagira (2009), a trade policy advisor for USAID,

explains that conflicting policies arise in Tanzania due to the primary objective of self-

sufficiency. Furthermore, he presents several motivations for EBs (Kagira 2011),

namely the preservation of national food stocks, price stability and the provision of food

to areas experiencing shortages. The key assumptions from the government were that

EBs would keep food in the country and therefore reduce prices and that the private

sector would not provide food to deficit areas because of infrastructural constraints. He

concludes that the availability of correct information and the fostering of regional

integration are key solutions for preventing the use of EBs.

15

From a review of the literature, detailed hypotheses were formulated for each of the

research questions that will be investigated in Part IV Analysis.

1) Was the use of EBs justified by market and institutional failures?

1.1) The ineffectiveness of the private sector was a reason to impose EBs.

1.2) The EB was motivated by the lack of effectiveness of alternative measures.

2) Was the use of EBs an informed decision?

2.1) The EB was based on perceptions of food shortage.

2.2) Decision-makers were not aware of the negative effects of the EB.

2.3) Decision-makers were unwilling to take into account evidence about the EB.

3) To what extent was the decision to use EBs influenced by political actors?

3.1) The government favoured concerns of consumers over farmers.

3.2) There was a strategic interaction between the private and the public sector.

3.3) Trade partners played a minor role in the decision-making process.

16

III Case study and methodology

Case study

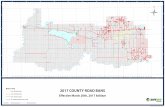

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania (URT)2 is situated in East Africa

with access to the Indian Ocean and is bordered by eight countries. The official capital

is Dodoma but the political capital Dar Es Salaam is also the principal commercial

centre and port of the country. This democratic republic is considered as a model of

political stability and governance, explaining why recent allegations of corruption have

been countered with drastic measures by the President (BBC News May 2012).

Tanzania is part of two regional agreements, the Southern African Development

Community (SADC) and the East African Community (EAC).

Agriculture is a main economic sector in this low-income country as it employs 80% of

the workforce and represents 1/3 of GDP (World Bank 2012, p.1). The agricultural

sector in Tanzania is divided between food crop and cash crop production, whereby the

latter provides most of its foreign exchange (Ponte 2002, p.52). Maize has been

traditionally the staple food and is produced mainly for own consumption (Musonda &

Wanga 2006, p.561). However, some of the poorest households are obliged to sell

cereals for their livelihoods even if it forces them to repurchase stocks later (Musonda &

Wanga 2006, p.575), which means that they are particularly vulnerable to seasonal

variations in grain prices. Tanzania has been a net importer of maize in most years

between 2000 and 2010 (FAO 2013), although these figures are likely to be distorted

because of informal trade. Expenditures on the agricultural sector constituted 9% of

total government spending in 2011, whereby 50% on average came from donor

contributions (MAFAP 2013, p.198).

The Tanzanian government officially transferred the marketing and trade of food to the

private sector at the end of the 1980s but kept a number of mechanisms in place that are

meant to ensure effective provision of food in the economy. The NFRA, which is a key

2 In the text Tanzania and The United Republic of Tanzania will be used interchangeably.

17

player in the maize market, has the function of stabilising prices by purchasing maize at

prices above the market price, and of providing food to recipients in need identified by

local authorities (MAFAP 2013, p.177). To import and export food crops, traders are

required to ask for permits that usually last one month (Kagira 2009, p.14). The decision

to hand out permits is made by the NFRA according to its assessment of the impact on

domestic food supply. The removal of export permits is the main mechanism by which

the government imposes EBs (Temu et al. 2010, p.22).

According to recent evidence (MAFAP 2013, p.183; Porteous 2012; World Bank 2009,

p.18), the government started imposing EBs on maize in 2004. In the analysis, the

chronology from MAFAP (2013, p.183) will be used for the timing of the introduction

and the lifting of EBs, which is shown in Table 1 below. EBs were lifted and

reintroduced eight times in the last decade, which indicates a persistency in the

motivations for imposing them.

Table 1: Chronology of export restrictions events in the United Republic of Tanzania,

2004-2013

Date Event

2004 Withdrawal of all maize export permits given to traders and the

suspension of issuing new ones

January 2006 Export ban lifted for two months

March 2006 Export ban reintroduced

January 2007 Export ban lifted

January 2008 Export ban reintroduced

May 2008 Export ban lifted

January 2009 Export ban reintroduced

October 2010 (or

April 2010) Export ban lifted

May 2011 Export ban reintroduced

January 2012 Export ban lifted

Source: MAFAP 2013 p. 183

18

Methodology

This dissertation uses qualitative research methodologies that are considered to be the

better choice when answering “why” or “how” questions (Denzin & Lincoln 2000). The

analysis adopts a multi-method approach based on primary and secondary data, namely

interviews with key stakeholders and newspaper articles in addition to grey and

published literature. Triangulation between different research methods and views from

various stakeholders was employed to enhance the validity of this study (Guion et al.

2011; Meijer et al. 2002, p.146) and also because the expression of a critical perspective

was expected to gradually increase from statements of functionaries to information in

the newspapers.

Twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted between 15 and 29 July 2013 via

Skype, using Callnote as a recording device. The interviews were on average 45 min.

long (30 min. – 1 h 20 min). The criteria for selecting interviewees was purposive

sampling (Esterberg 2002), which means that participants were chosen according to

their expertise in agriculture and trade and their degree of involvement in the process

(see Fig. 1 below). The two types of interviewees were functionaries and advisors.

Functionaries were chosen because of their direct involvement in the decision-making

process while advisors were chosen because of their indirect influence on the decision

through providing information and expertise in matters of trade and food security.

Interviewees comprised3:

- Functionaries: four senior officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and

Cooperatives (MAFC), one official from the Ministry of Industry and Trade

(MIT)

- Advisors: one senior manager from a large trade association providing advisory

services to the government, three academics from two key research institutes in

the country, one professor at Sokoine University, one representative from USDA

(United States Department of Agriculture) and one former representative from

USAID

3 To protect anonymity, the interviewees will be referenced using numbers and quotations will not be

attributed (Appendix 2).

The semi-structured interviews were conducted using a template

therefore ensuring a certain amount of comparability between responses.

mainly gave an orientation

purpose of semi-structured interviews is to allow an interactive discu

interesting topics arising during the conversation can be further explored

2009, pp.581–582). The open

interviewer bias and therefore inaccuracy, as the

most cases the discussion could be directed towards the

directly about it. Moreover, interviewer bias is reduced for telephone interviews as

interviewees tend to talk more freely and feel less pressured

In this study, there was a clear trade

them to the interviewee. In fact, the difference in the degree of involvement in the

decision-making process meant that the questions had to be adapted accordingly.

Moreover, English not being the national language

low quality of connections to Tanzania, questions often had to be repeated or

reformulated during the interview, which constitutes a clear source of bias.

source of bias was that interviewees were asked retrospectively about the

for using EBs, while the decis

structured interviews were conducted using a template

therefore ensuring a certain amount of comparability between responses.

of the types of questions that would be asked

structured interviews is to allow an interactive discu

interesting topics arising during the conversation can be further explored

The open-ended questions were left rather neutral to reduce

interviewer bias and therefore inaccuracy, as the EB is a politically sensitive

most cases the discussion could be directed towards the topic of the EB

Moreover, interviewer bias is reduced for telephone interviews as

interviewees tend to talk more freely and feel less pressured (Novick 2008, p.3)

In this study, there was a clear trade-off between keeping similar questions and adapting

rviewee. In fact, the difference in the degree of involvement in the

process meant that the questions had to be adapted accordingly.

Moreover, English not being the national language of the interviewees

ons to Tanzania, questions often had to be repeated or

reformulated during the interview, which constitutes a clear source of bias.

source of bias was that interviewees were asked retrospectively about the

, while the decision by the government to refrain from using this policy

19

(Appendix 3),

therefore ensuring a certain amount of comparability between responses. The template

of the types of questions that would be asked since the very

structured interviews is to allow an interactive discussion where

interesting topics arising during the conversation can be further explored (Longhurst

neutral to reduce

is a politically sensitive issue. In

EB without asking

Moreover, interviewer bias is reduced for telephone interviews as

(Novick 2008, p.3).

off between keeping similar questions and adapting

rviewee. In fact, the difference in the degree of involvement in the

process meant that the questions had to be adapted accordingly.

of the interviewees and given the

ons to Tanzania, questions often had to be repeated or

reformulated during the interview, which constitutes a clear source of bias. Another

source of bias was that interviewees were asked retrospectively about the motivations

the government to refrain from using this policy

20

tool had already been taken. However, the analysis of newspaper articles was meant to

reduce this bias, and for this research question this was the best method available given

the time and resource constraints.

153 newspaper articles from January 2000 to July 2013 were retrieved from the internet

using Factiva and Google. Articles were first selected using the keyword “export ban”,

but the search was expanded to make sure that it encompassed all factors relevant to the

EB. The search for articles was also very much facilitated by the kind provision of data

from Obie Porteous at the University of Berkeley. The articles retrieved were from local

and international, independent and government-owned newspapers.

For the evaluation of both types of data, thematic analysis was used, which involves the

identification of passages in the text that are linked by a common idea and their

categorization into themes (Agar 1983). Following the approach of Fereday and Muir-

Cochrane (2006), a mixture of inductive and deductive approach was used for coding to

allow themes to emerge both from the data and from the theoretical preconceptions of

the researcher. This approach is warranted since this is mainly an exploratory study

where new themes are expected to arise (Dey 1993, pp.97–98). An open coding was

first conducted, followed by an organisation of thoughts into categories that were

partially inspired by theory. The findings will be presented in qualitative terms since in

thematic analysis the importance of a topic is not necessarily defined by its recurrence

in the text but rather whether it captures something essential related to the research

question.

21

IV Analysis and discussion

This section will present the main results from the qualitative analysis of interviews and

newspaper articles. The section is organised according to the research questions and the

hypotheses, for each of which a short answer will be given before presenting the

detailed findings. The section will conclude with a discussion of the main results.

Analysis

1) Export bans as a response to market and institutional failures

1.1) The ineffectiveness of the private sector was a reason to impose EBs.

There was no clear indication that EBs were used mainly because of pockets of food

insecurity, which would have indicated a response to market failures. However, there

was evidence of arbitrage and misuse of market power that could have justified the use

of EBs from the government’s point of view.

Interviewees mentioned a number of infrastructure constraints and price differentials

across borders that either prevented or did not incentivise traders to transport food from

surplus to shortage areas, which was also mentioned by officials in the news (Reuters

October 2011; Financial Times December 2011). Price differentials were also presented

as a key reason why the government had not been able to effectively fight informal

trade (Daily News October (a) 2012). Mostly functionaries [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] but also

advisors [2, 9] indicated that private-public partnerships or meetings were required to

coordinate national objectives with market activities. However, the EB was not

presented specifically as a response to market failures. There was a quasi-consensus that

the decision base for the EB was food shortage but interviewees defined it in different

ways such as a specific threshold [4, 8], droughts [7, 8, 10] and price increases [5].

Government officials in newspaper articles also declared EBs were a response to

various problems, namely pockets combined with price increase (Business Daily

22

April 2008) and food shortage combined with price increase (Dow Jones December

2009; Financial Times December 2011).

Market power was seen as a foremost constraint that required interventions from the

government. Advisors and functionaries [1, 4, 5, 12] explained that traders could use

their information advantage to transmit higher transaction costs to farmers as well as

buying their crops before harvesting to store them and then re-sell them during food

scarcity. One of the advisors [5] described the “middlemen competition syndrome”

(Daily News October (b) 2012) and said that middlemen were artificially inflating

prices by denying market entrance and making large profits by using their market power

over farmers. Another advisor [6] talked about speculation by traders from

neighbouring countries who would import food from Tanzania and then re-sell it to the

country in times of food scarcity. The issue of market power from traders was also

highlighted by President Kikwete (All Africa July 2012).

Farmers would be forced by poverty, lack of savings and insurance to sell their products

at low prices and so bear all the risks. This vicious circle would justify trade measures

according to one government official: “…the role of the government is because the

people themselves they can sell everything but very few months to come then they are

crying4 because they have no food. So through that experience the government has to

intervene to make sure that all products have to be sold at a limited number.” Moreover,

the government explicitly stated that it is putting an emphasis on the control of trade

flows, which has the purpose of avoiding scarcity in the country (Daily News March

2012) and to prevent traders setting high prices in the market as their registration

enables tracking (Daily News May 2011).

1.2) The EB was motivated by the lack of effectiveness of alternative measures.

Constraints on imports and especially the ineffectiveness of the NFRA seemed to be

important factors justifying the use of EBs. This can also explain why EBs were not

4 “Cry” was a term often used in interviews and the media and from the context means that people will

bring something to the government’s attention through various means, including discussions in

Parliament, the media, protests or advocacy.

23

solely used in the event of a national food shortage but also for price stabilisation and

avoiding pockets of food insecurity, which are the responsibility of the NFRA.

Interviewees described different measures used in times of food crisis. At the national

level, the most important option mentioned was importing [1, 4, 7, 8, 9, 11]. On a

regional and district scale, the release of food stocks from the NFRA and international

assistance were seen as the main options [4, 7, 9, 10]. One of the advisors said that an

EB was simply the easiest measure to implement [10].

There was a recurrent theme about the constraints on imports. Surprisingly, only one of

the advisors mentioned budget constraints for imports [8] while three functionaries and

one advisor repeated in the conversation that imports had to be constrained by the

government [1, 3, 4, 5, 7]. The reasons mentioned were that farmers complained about

unfair competition, that there needed to be a control for diseases and that imports were

often not reaching vulnerable populations so that the food remained in the market and

depressed prices.

The NFRA was described by a majority of interviewees as playing a key role in the

country, but was described by one as expensive to manage [10] and not very effective

for food security, mainly because of the lack of funds [3, 6, 7]. Newspapers reported

lack of capacity and of budget to pay the farmers (Black sea grain online September

2010; Tanzania Reports November 2012; IPP Media April 2013). One article talked

about the lack of transparency of NFRA activities that leads to unpredictability for

market actors (Daily News June 2012) while the Deputy Chairperson of the Tanzania

Chamber of Commerce blamed the NFRA, accusing it of having favoured rich

commercial actors instead of farmers (Daily News February 2012). Even President

Kikwete admitted the ineffectiveness of the NFRA in an article in 2010 (Black sea grain

online September 2010). The NFRA and the EBs were often presented by interviewees

and in the news (RATIN February 2007; Daily News September 2011) as

complementary measures. In one of the articles the EB was described as a measure to

keep food stocks in the country, while the distribution of food from the NFRA had the

function of stabilising domestic prices (BBC Monitoring Africa July 2011).

24

2) Objectivity of the decision base and policy learning

2.1) The EB was based on perceptions of food shortage5.

Even though the EB was officially triggered by reports from the Early Warning System,

there were several indications of subjectivity in the decision base for the EB, in

particular for 2011. Moreover, there was mentioning of incentives to distort estimates of

food shortages.

There seems to be a divergence of opinions between functionaries and advisors on the

subjectivity of the decision base for the EB. Functionaries tend to see the decision base

as very much data-driven and objective [1, 3, 4, 5]. Two advisors [9, 10] however

emphasised that measures for food security are in practice triggered by more subjective

perceptions such as “markets [that] are not having grain” or “once you’re convinced that

people are dying”.

The official basis for food shortage calculations was described to me as follows [4]: The

Early Warning System receives information about production forecasts from districts

and compares that with the minimum caloric intake assumed per household. This is

complemented by information about coping mechanisms of households that will ensure

their food access, so that food self-sufficiency ratios can be recalculated and then

aggregated. The coping mechanisms are identified in preliminary assessments

conducted normally in February and June while the final assessment is published in

December. This information is assessed by the Food Security Unit of the MAFC and the

Disaster Management Department from the Prime Minister’s Office before the decision

for or against the EB is made. Therefore, the EB in March 2006 was probably based on

the information of the second vulnerability assessment and the EBs in January 2008 and

2009 on the final focus report.

5 This hypothesis was inspired by a collaborative study coordinated under USAID’s SERA project (Feed

the Future February 2013) whose major finding was that the method used in Tanzania tended to

overestimate food shortages because it considered maize to be more important in diets than it was in

practice. However, the study has not been published yet, neither in the official nor in the grey literature.

http://feedthefuture.gov/article/research-findings-maize-strengthen-case-end-export-bans-tanzania

25

However, the EB in May 2011 was imposed in a period of harvest and in-between

reports from the Early Warning Unit. In fact, one government official stated that the

decision in 2011 about the EB was “a really quick decision” and “not very much

supported by the statistics on the ground”. He also stated that the evidence in the final

report in December would not have supported such a measure. The public also

questioned the rationale behind the EB in 2011 (The Citizen September 2011) since

rainfall was expected soon and therefore increased production. The measure was

justified by the Minister of Agriculture (Diaspora Messenger September 2011) to ensure

food security until food availability would be clearly assessed, which shows again that

the EB had been imposed hastily.

The methodology for harvest prediction was challenged by two of the advisors [10, 12],

one of them saying that calculations were likely to lead to an overestimate of shortages

because private storage capacities were not included. One of the functionaries

highlighted the subjectivity of the surveys they undertake during the vulnerability

assessments [4]. There was also evidence of distortions in data reporting: one of the

advisors [10] reported that there is a rationale for district commissioners to overestimate

food shortages because of the fear of losing their jobs if they gave optimistic yield

estimates and a food crisis then occurred.

This statement from a government official represents very well the dilemma faced by

the EWS: “Our system is governmental and it's to give the government information that

can be probably adequately accurate but it can be less accurate. As you know early

warning is sending out information very early, sometimes it's an issue, time is an issue

more than accuracy. Accuracy will follow later.”

2.2) Decision-makers were not aware of the negative effects of the EB.

It seems that decision-makers were aware of the negative effects of the EB but that there

were fundamentally different views about how to ensure food security that prevented

learning. There are several lines of evidence of “blocked learning” where transmission

from functionaries to the institution was prevented.

26

One advisor [12] said that research in academic circles was unlikely to reach the

government, unless it was commissioned by it. However, advisors have been talking

about numerous workshops organised to inform the government [7, 8, 11, 12] about the

EB and one of the advisors [7] said that these had started in 2010, for which there was

also evidence in the news (The Citizen November 2010). One advisor talked about

advocacy and lobbying that had started around 2008 [6], when they had access to

evidence showing that the EB was not effective.

One functionary [2] mentioned studies that had shown the ineffectiveness of the ban and

that they had learned from it. There were two instances before 2012 where high level

officials acknowledged the ineffectiveness of the EB, namely the Minister of East

African Cooperation Diodorus Kamala in June 2010 (The Citizen June 2010) and the

Minister for Agriculture in April 2011 (In2EastAfrica April 2011). However, the EB

was reintroduced in May 2011, which shows that the learning process has been blocked.

An alternative explanation is that the political motivations to take symbolic measures

against food price increases were very strong in 2011, which will be further elaborated

in the next section.

There was evidence of fundamentally different views about ways to ensure food

security. One advisor said that the government saw food production as a means for

security, including interventions of the NFRA, while other actors in the economy saw it

as a means for their livelihood [7]. Others added [6, 9] that it was an awareness problem

rather than unwillingness on the part of the government to align its action with

liberalisation. One government official [9] talked about the opposition in views between

the public and the government in 2008. The public protested against EBs that were

considered as harmful for farmers, and the government’s response was that the mandate

was to ensure food security notwithstanding the costs. This followed a general pattern in

discussions with interviewees that I noticed, namely that food security and trade were

seen as separate from each other and that the former was placed above the latter. This is

also represented at an institutional level: interviewees mentioned a general collaboration

between the MIT and the MAFC but not for trade measures to ensure food security,

27

where the latter would be responsible. Therefore, the possibility of learning across

institutions having possibly differing interests was low.

2.3) Decision-makers were unwilling to take into account the evidence about the EB.

The evidence indicates that before 2012 non-learning could have been due to a

defensive approach of the government and that a change in approach meeting all three

conditions for a constructive dialogue outlined by Sabatier (1999).

One of the advisors said that a report in 2008 that described the drawbacks of EBs had

not been considered by the government “because what they care is to ensure national

food security”. He added that the recent combined effort from various stakeholders

including USAID had been effective.

Various advisors [7, 9, 10, 12] mentioned key studies that had convinced the

government to refrain from EBs in October 2012, namely reports from the SERA

project from USAID, MAFAP (Monitoring African Food and Agricultural Policies) and

studies from the ASARECA (Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in

Eastern and Central Africa). Prime Minister Pinda said that his decision had been based

on the findings from the SERA project (ACDI VOCA February 2013; Feed the Future

May 2013) and the Minister of Agriculture stated his support for the ASARECA

research project (IPP Media October 2012). The reports from the SERA project had

several characteristics that apparently differed from studies carried out before. Firstly, it

involved several well-known international organisations. Secondly, one advisor [10]

emphasized that the evidence was an empirical analysis as opposed to previous studies

that were mainly qualitative in nature. Thirdly, another advisor [12] said that the change

in approach to further engage the government in the evaluation and discussion of the

evidence within technical groups had led to a change in the position of the government

from “defensive” to “cooperative” since 2011.

28

3) Influence of political actors on the decision to use export bans

3.1) The government favoured concerns of consumers over farmers

It seems that generally consumers were favoured at the expense of farmers. In 2010, the

increase in attention paid to farmers’ concerns about the EB could have been related to

public opinion and the wish to win electoral votes in the countryside. This would match

the statement from Brian Cooksey (GREAT Insights September 2012) that there was

growing discontent in 2010 among the rural majority, usually the main supporters of the

CCM.

Several functionaries emphasized the role of the government to ensure low and stable

prices [1, 4, 5, 7] for consumers. One of the functionaries highlighted the fact that

consumers are being hurt by high prices and that “they will cry”. In 2011 there was

evidence of pressure from the public following the rise of food prices (Business Times

March 2011; Reuters July 2011; All Africa August 2011). Moreover, the government

has explicitly used EBs to limit the price increase in 2011 (Daily News September

2011). In 2011 the government issued directives to ensure that the urban poor would

receive enough food (Business Daily May 2011). One of the advisors said that the

government also needs to ensure that enough food is kept in the country because of

political motivations [10]. He explained that it would be very negative for election

outcomes if the government were to be seen as “insensitive” to food shortages.

Functionaries talked about the opposition of farmers to the EB, one of them mentioning

the discussions in Parliament where farmer representatives expressed their disapproval

(TradeMark Southern Africa April 2010; Diaspora Messenger September 2011; Daily

News April 2013). One of the advisors mentioned that the public opposition to the EB

in line with farmers started in 2008 and then continued to grow (The Citizen

September 2011).

There were numerous articles reporting about the government neglecting farmers and

not keeping electoral promises (Daily News August 2011; Daily News February 2012;

Daily News April (a) 2012; Tanzania Reports November 2012), while favouring

29

businessmen (Daily News April (b) 2012) and consumers (Daily News April 2013).

This would mean that the government was not very responsive to farmer’s interests.

However, the lifting of the EB in April 2010 was presented as a response to the protests

of farmers against the measure (Daily News April 2010; TradeMark Southern Africa

April 2010). In one article there is mention of the Prime Minister advising the President

to lift the ban during his political campaign6 in Rukwa, one of the centres of agricultural

production in the country (Black sea grain online September 2010).

3.2) There was a strategic interaction between the private and the public sector

There is evidence indicating a strategic interaction between the private and the public

sector, since the three main premises from the framework of Jayne and Tschirley (2010)

could be identified.

In my conversations with functionaries, there appeared to be striking opposition

between the usual decision-making process and the way decisions were made for the EB

[2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12]. The usual process would involve consultation with stakeholders

and approval by Parliament. The EB would be decided directly by the Prime Minister

and announced by the Minister of Agriculture, even though it was discussed in

Parliament [1, 3]. Interviewees also confirmed that there was no law or rule [1, 3, 8, 10]

clearly indicating when the EB should be implemented. This ad hoc implementation

gave insufficient time to the private sector to adapt.

Three advisors and two government officials talked about a difference in interests

between the private and the public sector [3, 4, 6, 7, 9]. One government official

mentioned that the reason for implementing EBs was because farmers were interested

mainly in business and getting the right price, and would therefore sell abroad even

when there are pockets of food insecurity, while the government aims to ensure that

everyone in the country is food secure. The advisors confirmed this opposition several

6 The elections were held on 31 October 2010 (CEPPS 2013), which means that the campaign was in its

final stages.

30

times. One functionary explicitly mentioned that trade measures were justified given the

lack of reliability and transparency of private-sector action [5].

At the national level, two advisors and one functionary [1, 4, 9, 12] have reported about

the problem of hoarding and lack of information about private stocks in the country.

Notably, one of them reported about the dilemma faced by the government in 2008:

“1: So you said that maize was not imported because the price was too high?

2: No, it was clearly whether we don't have maize or the maize is stored in the private

warehouses. That was a very tricky situation. Because the government decided to do a

rapid assessment of the situation of warehouses, there was no proper cooperation from

the private sector so the government decided to use the NFRA to release food.

[...]

1: So there were enough stocks... but why then did they use the export restrictions if

there were enough stocks?

2: No it's because now it was not very sure whether these guys they have food or no

food because then they can still decide to sell it to Kenya, that's where the market was

lucrative or to sell it Sudan, you understand. But by putting that EB they forced them to

sell in the domestic market.”

3.3) Trade partners played a minor role in the decision-making process

From the evidence below, regional partners had little influence on decisions for the EB,

as the government of Tanzania placed national over collective interests.

Interviewees were aware that, as a main provider of grain for the region, Tanzania was

constrained in its decisions to impose trade restrictions [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12] by “the spirit

of regional cooperation”, as one advisor formulated it. It was striking that in many

interviews there was a repeated emphasis on the temporary nature of the EB [1, 3, 4, 12]

and that it was “not a policy” [2, 8], possibly because this is the conditionality for EBs

31

at the WTO. Regional cooperation was also mentioned as a key reason why the

government decided against EBs in 2012 [11].

Members of the EAC generally have to inform the EAC Secretariat before

implementing any trade measures but two functionaries and one advisor clearly stated

that this had not been followed in the case of EBs [3, 4, 12], which had been negatively

received by trading partners in the EAC. When functionaries and advisors talked about

the cooperation between Ministries responsible for trade and food security, none

mentioned the Ministry of EAC.

Newspapers reported that there were considerable pressures from members of the EAC

to lift the EB in 2011 (The Citizen July 2011; Standard Digital News August 2011;

TRAC Fund September 2012). However, the government refused to lift the EB, even

after negotiations with the delegation of Kenya that was experiencing a major food

crisis. The government explained that despite a national food surplus, exports could not

be allowed because of pockets of food insecurity (Standard Digital News August 2011)

and inflation (TRAC Fund September 2012). The Deputy Prime Minister Christopher

Chiza also mentioned that the measure was only temporary and therefore not at odds

with the principles of regional integration (The Citizen August 2011). The bans were

seen as “efforts to frustrate the actualising major East African Community Goals”

(Standard Digital News September 2012) and did real damage to the diplomatic

relations of Tanzania with regional partners.

32

Discussion

The figure below summarizes the main factors that were identified in the analysis as

motivating the use of EBs in Tanzania. This should be interpreted as a schematic

representation that could be complemented by further applied research.

Source: author, based on the literature and research findings described above

There were a number of market and institutional failures arising in the analysis of

interviews and newspaper articles that would have justified government intervention

according to certain authors (Rodrik 1992; Abbott 2010; Timmer 2010). Constraints in

terms of infrastructure and price differentials certainly existed across borders.

Moreover, the ineffectiveness of the NFRA and a lack of sufficient revenues for

importation constrained the government in its choices, even though there also appeared

to be protectionist motives to deliberately restrict imports.

Figure 2: Internal motivations to use export bans in Tanzania

33

Both market power and uncertainty mentioned by Abbott (2010) and Gouel and Jean

(2012) were recurrent themes in the analysis and led to hoarding and speculative

behaviour. Market power was especially pictured as the misuse of information

advantage from traders over farmers. Moreover, there appeared to be a vicious circle as

in the framework of Jayne and Tschirley (2010) between the lack of information about

private stocks, the uncertainty about each other’s behaviour and the government feeling

compelled to impose EBs.

The government had no real alternatives at hand for the EB, which could explain why

research on the ineffectiveness of the tool was not taken into account before 2012. Other

possible reasons were blocked learning (Zito & Schout 2009) from bureaucrats to the

institutional level, the lack of inclusion from the government in the evaluation of

evidence and the lack of thorough quantitative evidence, therefore an absence of the key

factors for informed decision-making from Strydom et al. (2010). Overall, the decision

on EBs seemed to be only partially informed before 2012, meeting mainly the parts in

the framework of Maxwell et al. (2013) regarding the assessment of needs and

consideration of external factors.

After 2010, the decision seemed to be based on subjective perceptions of food shortage

while the EB increasingly became a politicised subject, which would confirm insights

from Babu and Mthindi (1995). There was evidence of an urban bias Bezemer and

Headey (Bezemer & Headey 2008) as farmers’ protests about the EB were neglected

until 2010, when their power as voters appeared to be a main reason for the lifting of the

ban, confirming Bates and Block (2010). As pressures from regional partners were

unheard in 2011, their influence on decisions for EBs seemed to be negligible.

Therefore, the advice from Kagira (2011) to solve information constraints seemed

retrospectively to be a more important measure to avoid EBs in Tanzania than

promoting regional integration.

In 2012 a constructive dialogue in the sense of Sabatier (1999) seemed to be a key

factor for the change of attitude by the government. However, the increase in farmers’

power after 2010 and the growing support from donors for commercialisation also

arguably played a role here.

34

V Conclusion

This dissertation aimed to analyse the motivations for implementing EBs from the

perspective of the Tanzanian government and to show evidence that could support it as

being a second-best choice. EBs seemed to be the best choice in the short term given the

combination of misaligned incentives from traders, the ineffectiveness of the NFRA and

the lack of knowledge about feasible alternatives. In addition, political incentives played

an increasingly important role in particular after 2010. However, given the

methodological limitations outlined above and the small number of interviews, the

results should be interpreted with caution and seen as possible, but not exhaustive

explanations for the use of EBs.

There were three main causes that were identified as important for the choice of EBs

from a political economy perspective. Firstly, there was evidence of a strategic

interaction with the private sector leading to a vicious circle between uncertainty and ad

hoc interventions. Secondly, there was evidence of an urban bias and the reason why

interests of farmers were taken into account in 2010 was probably because of upcoming

elections. Thirdly, regional partners had little influence on the government’s decisions

as national interests were prioritised, even when EAC members commonly disapproved

of the measure in 2011.

There was evidence that the use of EBs was not an entirely informed decision. Although

decisions were officially based on information from the Early Warning System, there

were instances where decisions were taken hastily and seemed to be based on subjective

perceptions of food shortage. Moreover, research on the ineffectiveness of EBs was not

really taken into account, which could be explained in part by the lack of involvement

of the government that led to a defensive attitude.

Although this study was meant to be exploratory, the tentative conclusions have

implications for future research. The advice often heard to counter the implementation

of EBs is to strengthen international regulations and foster regional integration.

However, in the case of Tanzania it was shown that in times of crisis national interests

of food security were prioritised “no matter what the costs”, including diplomatic

relationships. It would therefore be interesting to conduct similar studies in other

35

countries such as Zambia or India and for other crops, to confirm whether internal

factors are found to be as important as for EBs on maize in Tanzania. Other conclusions

are likely to be derived from these studies, which could further deepen the

understanding of motivations for using EBs in developing countries.

The commitment from the government of Tanzania in May 2012 to refrain from using

EBs was received with enthusiasm by national constituencies, regional trade partners

and the international community. A number of programmes have been set up to foster

commercialisation and production. For example, the Southern Agricultural Growth

Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) aims to enhance the functioning of the value chain

with investments in infrastructure and partnerships between agri-business, the

government and donors. If those initiatives manage to build trust between the private

and the public sector and enhance linkages in the country to avoid problems of localised

food shortages, the risk of policy reversal experienced in the past would be reduced.

Appendix 1 – Abbott’s (2010) theoretical framework

Source: Abbott 2010 p. 26

Abbott’s (2010) theoretical framework

36

37

Appendix 2 – Interview participants

Table 2: Interview participants

No. Occupation

1 Senior official from the MAFC

2 Senior official from the MAFC

3 Senior official from the MAFC

4 Senior official from the MAFC

5 Official from the MIT

6 Senior manager from a trade association

7 Academic from a research institute

8 Academic from a research institute

9 Academic from a research institute

10 Professor from Sokoine University

11 Representative from USDA

12 Former representative from USAID

38

Appendix 3 – Interview guide

Introduction

1. Can you tell me about your position and main responsibilities at X [Ministry,

Research Institute…]?

2. How long have you been working at X?

Stakeholders

1. Who is the most important decision maker for trade measures related to food

security?

� For advisors: How does X support the government for decisions on trade and

food security?

2. Who are the experts or organisations that advise the Ministries for trade measures?

� What is the role of research institutes in Tanzania to inform trade policy?

3. What other actors influence the decision on trade measures?

Decision making

1. How does the government of Tanzania intervene when there is a food crisis?

2. When trade measures are to be implemented, what are the steps that need to be

taken? What is the legal basis for trade restrictions?

� What is the role of the Ministry in the creation of policies? What is the role of

the Parliament?

� How has the decision making processes changed over time?

3. What information do ministries require in order to make decisions on trade

measures?

Motivations for the export ban

1. How important are trade measures for food security? Have they been effective?

2. Who is affected by trade measures to ensure food security in Tanzania?

3. Did other policies exist to solve the problem of food security? Why were they not

adopted?

39

4. How did the government of Tanzania consider the impact on other countries when

implementing export restrictions?

5. Why did the government decide to stop implementing export restrictions? Is it a

legal commitment?

6. How did the government of Tanzania react to the media coverage on export

restrictions?

Conclusion

1. Do you have any questions for me or is there anything that you would like to add?

2. Can you recommend anyone that I should speak to at X?

40

Bibliography

Abbott, P., 2010. Stabilisation Policies in Developing Countries after the 2007-08 Food Crisis. In Global

Forum on Agriculture 29-30 November 2010 Policies for Agricultural Development, Poverty

Reduction and Food Security. OECD Headquarters, Paris. Available at:

http://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/46340396.pdf.

ACDI VOCA February, 2013. Tanzania pledges to eliminate export ban on staple foods. 20 February

2013. Available at: http://www.acdivoca.org/site/ID/news-Tanzania-Eliminates-Export-Ban-on-

Staple-Foods-Embraces-Regional-Trade/.

Admassie, A., 2013. The political economy of food price The case of Ethiopia. UNU-WIDER Working

Paper No. 2013/001. Available at: http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-

papers/2013/en_GB/wp2013-001/ [Accessed August 25, 2013].

Agar, M.H., 1983. Political talk. thematic analysis of a policy argument. Policy Studies Review, 2(4),

pp.601–614.

All Africa August, 2011. Tough Lifestyle Changes As Food Prices Continue to Rise. 15 August 2011.

Available at:

global.factiva.com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/hp/printsavews.aspx?pp=Save&hc=Publication.

All Africa July, 2012. (A. R. Green and B. Scott) Getting Commodity Prices Right. 4 July 2012.

Available at:

global.factiva.com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/hp/printsavews.aspx?pp=Save&hc=Publication.

Anderson, K., Nelgen, S. & (Centre for Economic Policy Research), 2010. Trade barrier volatility and

agricultural price stabilization. Discussion Paper 8102. Available at:

www.cepr.org/pubs/dps/DP8102.asp.

Anseeuw, W., 2010. Agricultural policy in Africa : renewal or status quo? : a spotlight on Kenya and

Senegal. In The political economy of Africa. London: Routledge, pp. 247–261.

Babu, S. & Mthindi, G., 1995. Costs and Benefits of Informed Food Policy Decisions. A Case Study of

Food Security and Nutrition Monitoring in Malawi. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture,

34(3), pp.292–308.

Bates, R.H. & Block, S., 2010. Political Institutions and Agricultural Trade Interventions in Africa.

American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93(2), pp.317–323.

BBC Monitoring Africa July, 2011. Hunger across east Africa said causing food smuggling. 6 July 2011.

Available at:

global.factiva.com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/hp/printsavews.aspx?pp=Save&hc=Publication.

BBC News May, 2012. Tanzania leader sacks ministers amid corruption scandal. 4 May 2012, (May).

Available at: www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-17957767.

Bezemer, D. & Headey, D., 2008. Agriculture, Development, and Urban Bias. World Development, 36(8),

pp.1342–1364.

Black sea grain online September, 2010. Tanzania. Lift maize export ban, farmers plead with govt. 14

September 2010. Available at: www.blackseagrain.net/agonews/tanzania.-lift-maize-export-ban-

farmers-plead-with-govt.

41

Bouët, A., Debucquet, D.L. & IFPRI, 2010. Economics of Export Taxation in a Context of Food Crisis: A

Theoretical and CGE Approach Contribution. Discussion Paper 00994, (June). Available at:

http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ifpridp00994.pdf.

Business Daily April, 2008. (A. Odhiambo) Minister Faces Hard Task of Easing Food Crisis. 24 April

2008, (December 2007). Available at:

global.factiva.com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/hp/printsavews.aspx?pp=Save&hc=Publication.

Business Daily May, 2011. (A. Odhiambo) Tanzania Exports Ban Heralds Rise In Maize Prices. 20 May

2011. Available at: www.marsgroupkenya.org/multimedia/?StoryID=330560.

Business Times March, 2011. MDGS and a better life for all Tanzanians. 4 March 2011. Available at:

www.businesstimes.co.tz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=793:mdgs-and-a-

better-life-for-all-tanzanians&catid=1:latest-news&Itemid=57.

Cadot, O., Olarreaga, M. & Tschopp, J., 2010. Trade Agreements and Trade Barrier Volatility. In K.

Anderson, ed. The Political Economy of Agricultural Price Distortions. Cambridge University

Press, pp. 332–357.

CEPPS, 2013. Election Guide. Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening. Available

at: http://www.electionguide.org/country.php?ID=211 [Accessed August 25, 2013].

Chapoto, A., Jayne, T. & MSU International Development, 2009. The impacts of trade barriers and

market interventions on maize price predictability: Evidence from Eastern and Southern Africa.

Working Paper 102. Available at: http://purl.umn.edu/56798 [Accessed August 25, 2013].

Cooksey, B., 2012. Politics, Patronage and Projects: The Political Economy of Agricultural Policy in

Tanzania. Future Agricultures Consortium Working Paper 40. Available at:

http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/Futureagriculture/FAC_Working_Paper_040.pdf.

Cummings, R., Rashid, S. & Gulati, A., 2006. Grain price stabilization experiences in Asia: What have

we learned? Food Policy, 31(4), pp.302–312.

Daily News April, 2010. (O. Kiishweko) Excitement as Government Lifts Ban on Food Export. 21 April

2010. Available at:

global.factiva.com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/hp/printsavews.aspx?pp=Save&hc=Publication.

Daily News April, 2013. Tanzania Government urged to protect farmers against post harvest losses. 24

April 2013. Available at: http://www.dailynews.co.tz/index.php/biz/16702-government-urged-to-

protect-farmers-against-post-harvest-losses.