Digital Innovation in East Asia - World Bank

Transcript of Digital Innovation in East Asia - World Bank

Policy Research Working Paper 9124

Digital Innovation in East Asia

Restrictive Data Policies Matter?

Martina Francesca FerracaneErik van der Marel

East Asia and the Pacific RegionOffice of the Chief EconomistJanuary 2020

Produced by the Research Support Team

Abstract

The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent.

Policy Research Working Paper 9124

Digital technologies encourage companies to innovate with new processes, goods, and services, which ultimately enhance their competitiveness in local and global markets. This paper analyzes whether a wide set of data restrictions are negatively associated with digital innovation of firms. The paper develops an index of data restrictions that mea-sures the level of data policy restrictiveness for 15 East Asian countries over time. Using various firm-level data sets, the analysis shows that data restrictions inhibit firms’ ability to innovate. The analysis takes into account that data restric-tions are likely to have a greater impact in sectors that are

more reliant on software. Regressions show that in countries that have more restrictive data policies, firms are less likely to use foreign technologies through licensing as part of their innovation process. Country-specific cases for which data are available also show that restrictive data policies are neg-atively associated with firms’ likelihood of using intangible assets, such as patents and goodwill, for performing innova-tion (in Malaysia and China) and developing innovations as a result of research and development that are new to the market (in Vietnam). The paper concludes that open data policies are likely to foster digital innovation.

This paper is a product of the Office of the Chief Economist, East Asia and the Pacific Region. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. Policy Research Working Papers are also posted on the Web at http://www.worldbank.org/prwp. The authors may be contacted at [email protected].

Digital Innovation in East Asia: Do

Restrictive Data Policies Matter?

Martina Francesca Ferracane

University of Hamburg, ECIPE

Erik van der Marel*

Univestité Libre de Bruxelles & ECARES, ECIPE

JEL classification: O31; D22; C54; F14

Keywords: Firm‐level innovation; data policy restrictions; software.

* Corresponding author is [email protected], Senior Economist at ECIPE & Assistant Professor at the

Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), ECARES, Avenue des Arts 40, 1050, Brussels; co‐author is Martina Francesca

Ferracane, PhD, [email protected], Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute (EUI)

and Research Associate at ECIPE. We thank Prerna Rakheja, Pinyi Chen and Faruk Miguel Liriano for their

excellent research assistance. We thank Francesca de Nicola valuable advice and coordination when using the

different sets of the firm‐level data.

2

1. Introduction

The digital transformation in many economies opens a wide range of innovation opportunities for

firms. Digital technologies encourage companies to innovate with new processes, goods and

services, which ultimately enhance their competitiveness in local and global markets. Digital

innovation often happens through the internet and new online platforms to which firms increasingly

have access across borders. However, many firms today face significant restrictions when it comes to

these new digital technologies, access to the internet, the use of online platforms and the cross‐

border flow of data – most of which have been only recently enacted by governments.

This paper analyzes data restrictions that are expected to affect digital innovation that happens with

the support of data, the internet and online platforms. Together, we conveniently call them

restrictions to data. Restrictions to data inhibit firms to innovate using advanced software and more

generally data across borders, which today are an essential part of the innovation process of many

firms (Guellec and Paunov, 2018). For instance, big data, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and blockchain are

new digital technology developments that generate and make available huge volumes of data that

firms use to develop new products, services and even processes – all with the help of software.

These new technologies help create a competitive advantage for the firm. Restrictions to data are

therefore likely to slow down this competitive process.

We record data policy restrictions for 15 countries in the East Asian region and investigate whether

these barriers indeed impact the likelihood of firms to innovate.1 The reason we take the East Asian

region as a case in point is twofold. One is that digital innovation is rife in the region. According to a

recent OECD report, the increased use of digital technologies in East Asia is ushering the

transformation of economies and societies (OECD, 2019). Second, the region provides an interesting

variation of policy responses over time regarding data. On the one hand, there are countries such as

Indonesia, China and Vietnam that have either very strict data policies or have become much more

restricted with regards to data over time. On the other hand, there are countries such as the

Republic of Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines which have removed data restrictions.

For the purpose of this research, we have constructed an index that measures the extent to which

15 East Asian countries are restricted regarding data policies. This restrictiveness index builds on

previous work from Ferracane et al. (2018a; 2018b), but is expanded with new policies, such as

those related to Intellectual Property Rights (IPR), that are expected to affect more generally digital

innovation. The first step of this paper is to describe and analyze the developments of data

restrictiveness for the 15 countries in the region for which we have collected policy developments.

Then, the policy index is used to see how it correlates with firms’ performance regarding their

innovation activities in 10 East Asian countries. In doing so, we take into account that data

restrictions are likely to have a greater impact on digital innovation in sectors that are more data‐

intense, which we proxy by their software use. Finally, we select three countries (Malaysia, Vietnam

and China) for which we have specific firm‐level data and analyze further whether our restrictiveness

index has any bearing for firms’ innovation activities using different variables.

The conclusions of the correlation exercises for both the cross‐country and the three country studies

show that a more restrictive policy framework regarding data policies correlates negatively with the

extent to which firms innovate digitally. For instance, firms in countries that exhibit higher levels of

1 The countries are Cambodia, China, Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Other countries in the Southeast Asia region for which we have developed an index of data policy restrictiveness are Hong Kong SAR, China; Japan; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taiwan, China, which will be discussed.

3

restrictive data policies are less likely to use foreign technologies through licensing. In addition, the

country cases show that firms in Malaysia that face higher levels of data restrictions are less likely to

purchase foreign intangible assets, whereas firms in Vietnam that encounter higher levels of

restrictions are less likely to develop new goods and services that are new to international markets.

Together, the results show that data policy restrictions are significant obstacles for firms to develop

digital innovation in East Asia.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section provides the motivation for performing this study

and summarizes the recent literature regarding data, digital trade and digital trade policy

restrictions. Section 3 presents the estimation strategy in which the two levels of empirical analyses

we employ are discussed, i.e. the cross‐sectional regression examination as well as the country‐

specific cases of regressions. Section 4 discusses the results of both analyses and finally Section 5

concludes by putting the results in a wider policy context.

2. Motivation and Previous Literature

Despite the rising trend of data flowing across borders worldwide, research on this topic has been

surprisingly limited. Manyika et al. (2016) claim that the contribution of the cross‐border and use of

data flows to GDP has overtaken that of flows in goods as part of globalization today. The study

states that data flows currently account for $2.8 trillion of the total increased world GDP over the

last decade, thereby exerting a larger impact on growth than traditional trade in goods.

Recent literature has looked at the restrictive policies applied to data. A first attempt was performed

by Stone et al. (2015), which covers measures of data localization requirements only. Their study

notes that data flows enhance the efficiency of trade for specialized services firms both domestically

and across borders. Furthermore, work by Ferracane (2017) further categorizes the different forms

of existing data policies that affect the cross‐border movement of data. The study surveys data

policies applied across 64 major economies to show that data restrictions are implemented in many

countries, in different forms, and on different types of data. Finally, Ferracane et al. (2018b) have

developed a sophisticated index for 64 countries in which the level of data restrictiveness is assessed

covering many policy restrictions related to the cross‐border movement and domestic use of data.

An updated and expanded version of the index is used in this paper.

Research that analyzes the impact of data restrictions on economic outcomes is scarce. Van der

Marel et al. (2016) and Ferracane et al. (2018b) are the only two studies that explore how regulatory

policies related to data affect productivity. The authors analyze this linkage econometrically by

setting up a regulatory restrictiveness index for the cross‐border and domestic use of data from

Ferracane et al. (2018a) and extending this index over time. The authors calculate the costs

associated with restrictive data policies by regressing firm‐level productivity on a composite

indicator which measures the extent to which restrictive data regulations affect industries relying on

data using software as a proxy. They find that stricter data policies tend to have a negative impact on

the performance of firms in sectors which are more data‐intense. This paper employs a similar

identification strategy and analyzes the impact of restrictive data policies on firms’ innovation.

Other previous studies have looked specifically at one policy framework regarding data, namely the

EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and estimated the costs on the economy. Christensen

et al. (2013) uses calibration techniques to evaluate the impact of the GDPR proposal on small and

medium‐sized enterprises (SMEs) and concludes that SMEs that use data rather intensively are likely

to incur substantial costs in complying with these new rules. The authors compute this result using a

4

simulated dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model and show that up to 100,000 jobs could

disappear in the short‐run and more than 300,000 in the long‐run. Another study by Bauer et al.

(2013) uses a computable general equilibrium GTAP model to estimate the economic impact of the

GDPR. It finds that this law could lead to losses up to 1.3 percent of the EU’s GDP as a result of a

reduction of trade between the EU and the rest of the world.

Goldfarb and Tucker (2012) empirically prove the adverse link between restrictive data policies and

innovation and point out that stricter privacy regulations may harm innovative activities by

presenting the results of previous studies undertaken with respect to two sectors, namely health

services and online advertising. Both studies show that there are strong linkages between the

effective sourcing and use of data and innovation based on open markets. Recent work by Goldfarb

and Trefler (2018) discusses the potential theoretical implications of restrictive data policies such as

data localization and strict privacy regulations on innovation and trade, albeit from the perspective

of AI. The authors make clear that an expanded innovative AI industry in which data flows are an

important factor would be distorted by restrictive data policies such as data localization.

This paper combines the two strands of the literature by developing a specific yet expanded data

policy restrictiveness index based on Ferracane et al. (2018a). It then relates the index to firms’

digital innovation activities for a set of East Asian countries for which we specifically have developed

the data policy index. The index covers various measures related to data activities and is much

broader in scope than equivalent indexes used in the papers described above. For instance, in

addition to restrictions on the cross‐border flow and domestic use of data, we now also include

restrictions related to IPR for digital sectors, intermediate liability and content access for online

platforms, as well as regulatory policies regarding the telecommunication market. We expect these

data restrictions to be negatively correlated with the extent to which firms innovate, particularly in

sectors that are more reliant on data. In assessing this hypothesis, we use the identification strategy

as developed in Ferracane et al. (2018b).

3. Empirical Strategy

This section sets out the empirical strategy. We develop a composite indicator following the works of

Ferracane et al. (2018a) and Ferracane and van der Marel (2018). In these two works, a data linkage

variable is developed that interacts their data policy index with an industry‐level measure of data‐

intensity. In our case, the composite indicator is comprised of the index that covers for data

restrictions, including the ones related to IPR and telecommunication, which is interacted with

variable that measures the extent to which sector are intensive in the use of software. In our view,

this latter proxy crudely specifies how much each a sector employs data. Some sectors are more

dependent on data than others and we expect that data‐intensive sectors are proportionately more

affected by changes in restrictive data policies. To reflect this consideration, we therefore weight the

data policy index with our measure of software use that signifies data‐intensity at the industry‐level.

In a second step, we present our baseline specification for the regressions in which we use different

firm‐level variables that measure innovation and regress them on our composite indicator of data

restrictiveness. We perform regressions using two types of firm‐level data, namely one at the

aggregate cross‐country and industry level using the World Bank Enterprise Survey database, in

addition to three country‐specific firm‐level data sets for a small number of East Asian countries,

namely Malaysia, Vietnam and China. The results that derive from the two data sets are

complementary as they provide us different insights. The World Bank data represents a cross‐

5

country assembly of firms across time which would give us a collective view of the policy choices

countries made in the region. The latter data sets look specifically within Malaysia, Vietnam and

China and see whether those policies that are significant drivers for the cross‐country firm results

are also validated for firms within the three countries separately.

3.1 Data Linkage

The data linkage index builds on the methodology pioneered by Arnold et al. (2011; 2015). Their

approach in which the authors create a so‐called services linkage index has been widely used in the

empirical field. In our case, we develop a data linkage index variable for digital innovation and use

this composite indicator in our regressions. For each country, we interact the country‐specific data

policy index with software use as proxy for measuring the extent to which a sector uses data in their

production process. This identification strategy relies on the assumption that sectors more reliant on

the use of software are more affected by data restrictions. This weighted method is a more refined

way of measuring the impact of restrictive data policies rather than simply taking an unweighted

approach of regressing our data policy index on any outcome variable of innovation.

In doing so, the country‐specific index of restrictive data policies we develop is multiplied with

sector‐specific data‐intensity proxied by software use for each downstream industry j in country c.

This is how the data linkage (DL) variable is set up. In this variable, data‐intensities are expressed as

(D/L) which is measured by the sector’s software use over labor (see below). In equation (1),

therefore, the term ϛ denotes the software use for each sector j for which data is retrieved from

the US Census ICT survey. Then in equation (1), the data‐intensities are stated as a ratio over labor,

called 𝐿𝐴𝐵 , that is employed in each downstream sector j. The data for labor is retrieved from the

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). As a result, we apply the following formula:

𝐷𝑎𝑡𝑎 𝐿𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑎𝑔𝑒 DL ln∑ ϛ

∗ 𝑑𝑎𝑡𝑎 𝑝𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑦 𝑖𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑥 (1)

Note that we put the intensity indicators in logs, in line with previous literature on factor intensities.

This expression of intensities is close to the literature of comparative advantage such as Chor (2011),

Nunn (2007) and Romalis (2004).2 Finally, in equation (1), the data policy index refers to a country‐

year specific variable measuring restrictive data policy (see Section 3.3), whereas the data on

software refers to the US‐specific data on software use by industry for one year (see Section 3.2),

which is done to avoid endogeneity issues. This may occur in the event that high data‐intensive

sectors with greater digital innovation activities over time push for lower regulatory restrictions

regarding data in any particular country. The use of this common sector‐specific data‐intensity for

one country therefore makes the variable more exogenous.

2 An alternative way of measuring intensities such as the one used in Arnold et al. (2011; 2015) and Bourlès et al. (2013) is to create an indicator of dependency using input‐output matrixes, which we have also done in Ferracane et al. (2018a) and Ferracane and van der Marel (2018). We use this information as well in our paper for the country‐specific case studies. In such way, we have two approaches to data‐intensities, i.e. one based on data from surveys and one from accounting data. In our view, however, data‐intensities over labor are a more sophisticated way of measuring data‐intensities, particularly regarding innovation.

6

3.2 Data Intensities

For our measure of data‐intensity as defined in equation (1), we use information on software use

from the 2011 US Census ICT Survey. These data are survey‐based and record at detailed 4‐digit

NAICS sector‐level how much each industry and services sector spends on inputs from the ICT‐sector

in terms of ICT equipment and types of computer software in million USD.

We take computer software expenditure to compute data‐intensity. The ICT Survey records two

separate variables on software expenditure, namely capitalized and non‐capitalized. Non‐capitalized

computer software expenditure is comprised of purchases and payroll for developing software and

software licensing and service/maintenance agreements for software. Capitalized computer

software expenditures cover capital expenditures of equipment and software itself. Although this

proxy of software does not entirely capture the extent to which sectors use electronic data, it

nonetheless is the closest kind of data‐use variable we can publicly find. Note however that inside

firms, data‐based innovation is based on software and therefore provides a good reason to use

software as a proxy. We take the year 2010 for our regressions and divide this software expenditure

over labor, also for 2010, and use it for our data linkage variable.

Admittedly, this proxy for data‐intensity is not ideal. Currently there is no data on the extent to

which data is used by sectors. There are only some guesstimates on how much data are used by

countries, such as recorded by Cisco or Teleography, but even these sources provide data for only a

handful of observations. Having said that, what is clear is that the transmission of data for

innovation within and across borders over the internet is performed using software technologies.

Software is needed to develop digital innovations in its simplest form and with the help of software

data are transmitted. In addition, more technology advanced transmissions of data over the internet

are done with the help of cloud computing technologies which in themselves are a form of software.

Hence, despite not entirely capturing how much data are really being used in sectors, using the

intensity of each sector’s use of software is in our view the first‐best available proxy.

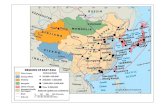

Figure 1 provides an overview of the data‐intensities for each sector calculated on the basis of non‐

capitalized expenditures of software.3 The data to construct these intensities are downloaded at

various digits levels in NAICS given that the US Census records this information at mixed levels

between 2‐digit and 4‐digit. All data are re‐concorded into the ISIC Rev 3.1 2‐digit level. Employment

data are from the US Labor statistics and given in 6‐digit level and also re‐concorded into the ISIC

Rev 3.1 2‐digit level. We have developed our own concordance matrix at the most disaggregated

level between the two data sources and then aggregated up to 2‐digit level by taking the simple

average. The reason for re‐classifying these data points is that our innovation variables are provided

in 2‐digit ISIC Rev. 3.1. Since data are given at two different aggregations across the software and

labor, we first concord all data into ISIC and then compute the intensities.

The 15 sectors in Figure 1 show the ranking sectors that have the highest data‐intensities based on

our proxy of software expenditure. Not surprisingly, telecommunication is the sector that shows the

highest data‐intensity level and is therefore very software‐intense compared to labor. Other very

high data‐intensity sectors are computer and insurance and finance, which is also unsurprising. They

also use a high amount of software compared to labor. The latter two sectors are more broadly

considered as very technological‐intensive and internet technologies have massively increased in the

3 Of note, we take that part of non‐capitalized software expenditures which measures how much each industry spends on purchases and payroll for developing software, which represents, on average, 47 percent of total non‐capitalized software expenditures. The other 53 percent of non‐capitalized software expenditures covers for each industry the software licensing and service/ maintenance agreements.

7

financial services industry. On the other side of the spectrum (not shown in the figure), sectors such

as furniture, construction, sale of motor vehicles and wearing apparel are shown to be least data‐

intense. The middle‐range of sectors using software intensively is a mix of modern and traditional

sectors such as transport services and various manufacturing industries such as basic metals.4

3.3 Data Policy Index for Digital Innovation

The second term of our data linkage variable is the data policy index, which is based on a

quantifiable set of country‐specific regulatory policies which are expected to have a restrictive

impact on digital innovation. These restrictive policies relate to the use and transfer of data, IPR,

intermediate liability, content access, as well as regulatory policies regarding the telecommunication

market. We draw on Ferracane et al. (2018a) and ECIPE’s Digital Trade Estimates (DTE) database to

develop and construct this index.5 The policies used for the analysis are those considered to create a

regulatory cost burden for firms relying on data for their innovation activities. The criteria for listing

a certain policy measure as a restriction in the database are the following: (i) it creates a more

restrictive regime for online versus offline users of data; (ii) it implies a different treatment between

domestic and foreign users of data; and (iii) it is applied in a manner considered disproportionately

burdensome to achieve a certain policy objective.

The data policy index is composed of 6 different categories, each containing a set of policy

restrictions related to a specific digital policy field which are: Intellectual property rights (IPR), cross‐

border data flows (CBDF), domestic use and processing of data (DP), intermediate liability (IL),

content access (CA), and finally infrastructure and connectivity (INF). In our view, these categories of

data‐related policies present the most important policy restrictions to digital innovation that can be

found in East Asia. As said, each category has various specific restrictions which can be further found

in Table 1. All restrictions are explained in Ferracane et al. (2018), which also provides further

information on the motivation for why they form a restriction and discusses the way of scoring their

level of restrictiveness. The index covers the years 2009‐2019. In addition, the policies in the index

have been updated with new regulatory measures found in each country.

To build up the index, each specific policy measure receives a score that varies between 0

(completely open) and 1 (virtually closed) according to how vast its scope of restrictiveness is. A

higher score represents a higher level of restrictiveness in data policies. While certain data policies

can be legitimate and necessary to protect non‐economic objectives such as the privacy of the

individual or to ensure national security, these policies nevertheless create substantial costs for

businesses performing data‐related innovation activities and are therefore taken up in our index.

Starting from the DTE database, the specific policies are aggregated into an index using a detailed

weighting scheme adapted from Ferracane et al. (2018b), which can be found in the last column of

Table 1.

4 One noticeable outlier in Figure 1 is the food products sector, which appears to have an extreme above‐average data‐intensity. One potential reason is that the US Labor Statistics only records employment data for 10 out of a total of 85 6‐digit NAICS sub‐sectors for this industry that all fall into the 2‐digit ISIC industry of food products as measured by the concordance table. Hence, it is very likely that labor is underreported for this sector which as a result increases the data‐intensity given that our measure is expressed as a ratio in which labor forms the denominator. Therefore, in the regressions we exclude the sector of food products although including this sector does not significantly alter the main results. 5 The authors have contributed to the development of the database at ECIPE. The data set comprises 64 economies and is publicly available on the website of the ECIPE at the link: www.ecipe.org/dte/database.

8

More specifically, each category of data policy restriction is weighted for the full index. In addition,

within each category, each specific policy restriction is also weighed against each other. Yet, in most

cases the policy restrictions receive equal weights within their respective category as can also be

found in Table 1. For the categories, both the IPR and the CBDF also receive an equal weight of 0.25,

which therefore together accounts for half of the overall index. The other half is covered by the four

remaining categories in which both the DP and CA categories receive a weight of 0.15. Further, the IL

and the INF categories are assigned a weight of 0.1. Note that in some occasions a new specific

policy restriction is included, such as whether a country has a data protection law in place, which

was not taken up in Ferracane et al. (2018). Annex A of Ferracane et al. (2018b) provides further

detailed information on the weights, scoring and description of the policy measures.

After applying our weighting scheme, the data policy index varies between 0 (completely open) and

1 (virtually closed). The higher the index, the stricter the data policies implemented in the countries.

Table 2 presents an overview of the final index for each East Asian country and shows how each

category of restrictions contributes to the final index score. What becomes clear is that China is most

restricted with a score of 0.91. In large part, this is caused by the high level of policy restrictiveness

in the categories of IPR and CBDF. After China comes Vietnam with a score of 0.82, and then third

both Thailand and Indonesia which both have a level of restrictiveness that scores 0.64. The least

restricted country is Hong Kong SAR, China, with a score of 0.09 and is therefore almost virtually

open. It only shows some minor restrictions related to IPR and intermediate liability. Japan is the

second least restricted country with a score of 0.20. Together the set of East Asian countries allow

for substantial variability in our data policy index as illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 4.

Figure 3 shows how the full index of data policy restrictiveness has evolved over time between the

years 2009 and 2019. The line is computed as the weighted average of the 15 East Asian countries

covered by the index with their respective GDP used as weights. The reason for doing so is that in

order to get a non‐biased trend of restrictiveness for the entire region, countries’ restrictions should

be corrected for their individual developments. A small country such as Vietnam might be very

restricted but compared to China or Indonesia has a much smaller economic impact in the region.

Treating all countries equally would therefore give a distorted picture of the aggregate level of

restrictiveness for the entire area. As one can see, there is a clear upward trend reflecting the fact

that data policies in the East Asian region have become more restrictive over time.

3.4 Descriptive Analysis

Before turning to the econometric assessment using firm‐level data of innovation, we first provide

some descriptive analysis of our data policy index and show how it relates to existing variables of

innovation that are computed at the level of country and sector.

We first do so by taking one of the firm‐level innovation variables from the World Bank Enterprise

Survey and average this binary information by country and sector. Admittedly, doing so has

problems as the variable is initially dichotomous and would much depend on the number of firms

included in the sample. Nonetheless, it would be worthwhile to conduct this analysis in order to

obtain a first impression of the potential direction that the econometric correlations may take. We

undertake this analysis for all sectors, but for now focus on the computer and related services sector

given that our interest lies in the responsiveness of firms in a sector that is data‐intensive. Figure 1

showed that the computer and related services sector is an intense user of software.

9

Figure 4 shows a negative relationship once we plot our data policy index of restrictiveness for each

East Asian country against our preferred variable of innovation in the computer and related services

sector that is found in the Enterprise Survey database. The figure selects the average of the h5

variable, but an equally sharp negative correlation appears for the other innovation variables that

have been selected from the same database. Clearly, countries with higher levels of data

restrictiveness appear to have lower innovation activities in the computer services sector. China is an

interesting outlier in Figure 4. The country is very restricted in data as measured by our data policy

index, but at the same time exhibits a very high degree of firm‐level innovation in computer services.

This fact is little surprising given China’s fast‐moving activities in the digital field, but the figure also

shows that the country is clearly an exception in the region.6

Another interesting correlation is illustrated in Figure 5. We use a country‐specific variable that is

plotted against our data policy index. We take a standard variable that measures how much East

Asian countries import digital services as a share of their total commercial services imports. In this

case too, we see that a tight negative correlation exists between the two variables. This suggests

that countries which are more restricted regarding data policies exhibit a lower share of digital

services imports. Although this variable of services trade is not taken up in our econometric analysis,

it nonetheless points out to close the link between digital innovation and open markets. The services

trade variable measures digital services imports performed over the internet such as software whilst

the data policy index captures restrictive trade policies that target digital technologies such as the

internet, data and online platforms.

However, in order to formally assess whether across the entire economy of each East Asian country

firms in data‐intensive sectors are truly affected in their innovation activities as a result of higher

data restrictiveness, the identification strategy takes into account the extent to which each sector is

data‐intense by employing a sector’s software use as a proxy, as explained above.

3.5 Baseline Regressions

As previously said, to measure whether the data policy index has any meaningful relation with

innovation activities at the level of the firm in East Asian, we employ two regression approaches.

The first approach takes a cross‐country dimension in which we perform regressions for 10 East

Asian countries for which we have data. Then, as the next step we select a number of countries for

which we have specifically recorded firm‐level data from a national source and evaluate whether our

cross‐country outcomes are consistent with these country‐specific regressions. There are two main

reasons why we undertake this two‐step approach. One is that the cross‐country exercise tells us

something about the differences of countries over time, whereas the country‐specific puts more

emphasis on the development of the policy restrictions as such and therefore guides for a more

specific policy advice.7 Also, the two sources of data record different innovation variables, which

6 Furthermore, Table A1 in Annex A shows that China’s high innovation activities are not caused by an exceptionally high number of firms recorded in the Enterprise Survey database. Therefore, it means that aggregating the firm‐level innovation variables into an average by country and sector does is not influence China’s extreme position. 7 Moreover, there are also technical reasons for why we exploit these two dimensions of data. One is that the source for the cross‐country approach reports years with intervals, is survey‐based and is unbalanced, whereas the country‐specific data are more complete and census‐based. Although one could argue that the latter approach is more meaningful to analyze, exploiting the two approaches is useful because of the reasons

10

therefore provides us further insights on which specific part of innovation that firms perform data

restrictions have an impact.

We start with the cross‐country approach. Equation (1) is used in our baseline regression which is

specified in equation (2) below. Equation (2) measures the correlation over time between the data

linkage index as described above and several variables of innovation (see below) measured at the

level of the firm. Hence, we regress our variables of firm‐level innovation that is recorded for each

firm f¸ for country c, in sector j, at year t, on the data linkage (DL) index which itself is specified at

country‐sector‐year level. As a result, the baseline specification for our regressions as correlations

takes the following form:

INNO 𝛷 𝜃DL 𝛿 𝜃 𝛾 𝜀 (2)

In equation (2), the vector INNO consists of four firm‐level innovation variables across our selected

group of East Asian countries. These variables are: (1) whether the firm has introduced a new

product / services over the last 3 years; (2) whether the firm has introduced a new process over the

last 3 years; (3) whether the firm uses technology that is licensed from a foreign company; and

finally (4) whether the firm has spent on new R&D (excl. market research) in the last 3 years. The

four variables are respectively indicated by h1, h5, e6 and h8, which is consistent with the labeling of

the World Bank Enterprise Survey database from where the data are sourced. Note that these firm‐

level data are cross‐sections for each year between 2009 and 2018 with intervals and as such do not

record data for the same firm each year. Tables A1, A2 and A3 and Figure A1 in Annex A provide an

overview of the cumulative firm distribution of the four innovation variables and gives summary

statistics by country and sector.

Note that our dependent variables are formulated for which responses are only allowed in a binary

way. The Enterprise Survey database reports these answers with a simple Yes or No. We have

transformed the variables in a dummy so that effectively it becomes a non‐linear estimation in the

sense that INNO ∈ 0,1 . We are therefore compelled to perform a Probit model. However, we

first perform an LPM model with fixed effects before moving into a Probit regression, as the former

provides us additional information about the direction in which the Probit results are most probably

going to when regressing.8 Moreover, for our three country cases only LPM regressions can be

performed and thus for reasons of consistency we report both types of result. We estimate our

Probit model with a conditional (fixed‐effects) logistic regression, because of the inclusion of our

various dimensions of fixed effects.

As described above, our DL variable is defined at country‐sector‐year level following equation (1)

and therefore varies over all three dimensions. Although we have data for our data policy index up

until 2019, we can only include up to 2018 as the Enterprise Survey data do not go any further.

provided above and because it effectively tests for two different kinds of variations. Moreover, the country‐specific data source reports different types of innovation variables which are used as our dependent variable. 8 There are however problems with the LPM. One of the main issues is that the LPM does not estimate the structural parameters of a non‐linear model (Horace and Oaxaca, 2006). If the Conditional Expectation Function (CEF) is linear (which means that conditional mean of a random variable is its expected value), then even an LPM regression gives the CEF. Instead, if the CEF is non‐linear the otherwise standard approach of using Probit approximates the CEF, in which case the LPM does not give any meaningful marginal effects. However, given that we do not know whether the model is truly non‐linear both LPM and Probit are useful.

11

Equation (2) also includes fixed effects by country (𝛿 ), sector (𝜃 ) and time (𝛾 ), respectively. Note

that despite the fact that our dependent variable is given at the firm‐level, we cannot include firm‐

level fixed effects because of the repeated cross‐sectional nature of the Enterprise Survey data set

and so following developments of the same firm over time is not possible. Finally, the 𝜀 is the

error term, which for the LPM regressions are clustered by sector country. For our Probit regression,

we are unable to cluster, but the data are grouped by sector.

Our second approach is using country‐specific firm‐level data. We have firm‐level data sets from

Malaysia, Vietnam and China. Obviously, the three data sets differ in variable coverage which means

that the innovation indicators are not consistent across each other despite all three data sets report

companies’ balance sheets information. Data are available for the manufacturing sector only.

In the regression specification presented below in equation (3), the innovation variables are again

summarized in a vector called INNO in which the dependent innovation variables are dummies as

well. Hence, INNO ∈ 0,1 in equation (3). The empirical setup is largely similar compared to

equation (2) with only some minor differences. One is that our data usage indicator as defined in

equation (1) needs to be adjusted as we do not observe software use and labor in any of the

countries. Data on these two variables are hard to find for any of the East Asian countries. Second is

that the regression equation is specified for one country only so that policy changes over time are

the focus (as opposed to policy differences across countries in the cross‐section analysis). In order to

analyze this latter aspect in more detail, our DL measure will now be lagged with 2 years when

possible and 1 year otherwise.

In all, the baseline regression equation for the three countries looks as follows:

INNO 𝛷 𝜃DL 𝜇 𝜃 𝛾 𝜀 (3)

where INNO is comprised of the innovation variables recorded in each country‐specific data set for

Malaysia, Vietnam and China. The DL term is exactly similar to the one in equation (2) where the

data policy index is interacted with the data/software intensity. In our three country cases however,

given the lack of data on this variable in the region, we are left with measuring the sheer proportion

of data usage as part of total input use instead. We use national input‐output (IO) matrices to

compute the proportion of ICT‐services in total input use for each sector in the three countries. The

national IO tables are taken from the World Bank and are reported at 2‐digit ISIC Rev. 4 level. IO

tables are available for each country and therefore represent a consistent source. For each

regression, we take input coefficients at the domestic level (i.e. excluding imports) and for a year

that falls at the beginning or in the middle of the time period of analysis.

Further, the terms 𝜇 , 𝜃 and 𝛾 are the firm, sector and year fixed effects, respectively. Note that it

follows naturally that due to the fact we have three country‐specific regressions, we are unable to

include any country fixed effects. Finally, the 𝜀 is the error term, which now for the LPM

regressions are clustered by sector. Of note, due to technical constraints we cannot run the Probit

model and therefore perform LPM for all three countries.9 In addition, for China we also perform

OLS on several occasions as the type of data allows us to do so.

9 More specifically, when running a Probit model while performing the regressions the combinations of groups and observations result in a numeric overflow in the two country cases of Vietnam and Malaysia. This

12

4. Results

This section reports the results of both approaches in similar subsequent manner. The results of the

cross‐country regressions are given in Tables 3 and 4 in which the LPM and Probit results are

reported respectively. The country‐specific results are provided in subsequent tables.

4.1 Cross‐Country Results

For the LPM regressions in Table 3, results are in all but one occasion insignificant, meaning that in

most cases no statistically significant correlation is found between the data linkage variable and

firms’ innovation activities. That is, restrictive policies in data do not show any meaningful

correlation with respect to the firm’s choice to introduce a new product or service as shown in

column 1, or to introduce a new organizational procedure as reported in column 2, or to spend more

on R&D as shown in column 4. However, the data linkage variable does come out statistically

significant in column 3 which shows that restrictive data policies are significantly negative correlated

with whether a firm takes on a technology that is licensed from a foreign company.

The results for the Probit regressions reported in Table 4 are consistent in the sense that the

coefficient result in column 3 are now estimated with precision. This means that more restrictive

data policies are significantly correlated with a lower likelihood of firms to acquire a technology

licensed from a foreign company. Taking into account that the marginal impact of changing the data

policy index is not constant, a one‐unit increase in restrictions as part of the data‐linkage index

variable is therefore associated with a lower probability by firms to use foreign‐licensed technology.

The other three innovation variables remain again insignificant even though the sign in columns 1

and 4 give a negative direction, which in the LPM regression was not the case. Note as well that the

coefficient sizes increase substantially compared to the LPM results.

The fact that the variable of foreign licensed technology is significant may raise potential suspicion.

For instance, one could suggest that the foreign technology that is licensed may also include

software, which therefore may be correlated with our data policy index. This is because of the

multiplicative term of the data‐linkage variable in equation (2) also includes the extent to which each

sector uses software. However, a closer look at the Enterprise Survey variable description states the

survey question as: “Does this establishment at present use technology licensed from a foreign‐

owned company, excluding office software?” Hence, we are assured that no artificial or spurious

correlation is being picked up in our regressions.10 On the contrary, given that the coefficient results

are significant, it seems likely that foreign licensed technology as part of a firm’s innovation activity

is related to a country’s framework of regulatory policies in data. Moreover, higher levels of data

restrictiveness found in countries appear to hamper firm‐level innovation in sectors that are more

intense in using software.

effectively means that mathematical computations of our econometric performance exceed the limit for the largest number representable when an attempt is made to calculate the binomial coefficient. 10 See the Enterprise Surveys Indicator Description, page 112, which can be found here: https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/methodology/Indicator‐Descriptions.pdf.

13

4.2 Country‐Specific Results

This section presents the regression findings for the country‐specific cases of Malaysia, Vietnam and

China. Further details of the survey questions and variables covered in the regressions, as well as

some summary statistics for each of the specific country data sets for Malaysia, Vietnam and China,

are provided in Annexes B, C and D, respectively.

4.2.1 Malaysia

For Malaysia, we have data on the extent to which each firm has purchased, used and produced

intangible capital such as patent, goodwill, work in progress (including imports of both new and used

intangible assets), and to the amount of R&D spending for every firm. Used assets are the purchases

of assets previously used in Malaysia including those reconditioned or modified before acquisition in

the country. Purchased assets are newly bought assets and finally, produced assets are assets

produced by the establishment in Malaysia for its own use. Data only span the years after 2008,

because of its use of the MSIC 2008 classification which neatly corresponds to ISIC Rev. 4. However,

this leaves us with only two years for the analysis, namely 2010 and 2015, which is demanding if we

apply year fixed effects. All variables are transformed in a binary mode so that positive values of

greater than 0 will be assigned a 1 and 0 otherwise.

Before turning to the regression results, Figure 7 provides a descriptive examination of the main

variables used for the empirical specification. The graph plots the IO coefficients of ICT‐services

inputs for Malaysia on the horizontal axis against a composite indicator of all the four firm‐level

innovation variables from our Malaysian data set, which we call innovation score, and which is

summarized into the INNO term. This Innovation Score is then computed as ∑ INNO 𝑁 where N

is the total number of questions. The innovation score is averaged by sector and year. In this graph,

the fitted values line is plotted on the basis of excluding the sectors Coke & Petroleum and Other

manuf. & Repair as they appear to be extreme outliers. (Note that the two sectors are also excluded

from the regressions.) An upwards sloping correlation is visible in the sense that more ICT‐services

intensive sectors have a higher value on our innovation score. The regressions will show whether the

index of data policy restrictiveness in Malaysia, as shown in Figure 8, has any role to play.

Results are reported in Table 5. In there, the regression coefficients for R&D expenditures in column

1 gives significant results, which is somehow counterintuitive. This unexpected result could be seen

in light of a reaction by firms to perform more R&D as a consequence of the restricted access to

foreign markets for their innovation activities that otherwise is essential for digital innovation. In

column 3, the coefficient result gives a negative and significant outcome. It indicates that firms in

data‐intense sectors (proxied by their share of ICT‐services inputs) faced with higher levels of data

policy restrictions is associated with a lower use of firms’ intangible assets as part of their

production. Both variables of purchased and produced intangible assets in columns 2 and 3

respectively provide negative coefficient signs but are statistically unimportant.

4.2.2 Vietnam

In the case of Vietnam, we have a different set of variables although the first variable to use overlaps

with the Malaysian data: both report whether the firm performs the size of R&D activities. The

second innovation variable measures more precisely whether the firm’s R&D activities are targeted

14

at an innovation that is new for the market or world in which case the value of this variable takes a

1. If the innovation is only new to the firm, this observation receives a score of 0. The next two

variables measure whether the firm has any national or international patents which is also provided

in the Vietnamese data set. Finally, the last variable that is included measures whether the firm

undertakes a research collaboration in any format. All variables cover the years 2010‐2013, but due

to our lagged structure only three years can be included.

Figure 9 first provides an overview of the extent to which the IO coefficients and the Innovation

Score for the five firm‐level variables are correlated. The Innovation Score for Vietnam is computed

in similar way as for Malaysia and the IO coefficients are from the Vietnamese IO tables. An upward

sloping fitted values line is plotted indicating that, on the whole, a positive association exists

between the two variables. (Note however that for similar reasons as described above the Coke &

Petroleum sector is excluded as well as Paper & Printing sector when plotting the fitted values. The

two sectors are also excluded in our regressions.) The sector of Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals has a

much higher Innovation Score and also a high ICT‐services inputs as part of its total domestic input

use. On the other hand, a sector like Food & Beverages reports much lower levels on both indicators.

Figure 10 provides an overview of the Vietnamese developments of the data policy index.

Results of the regressions as correlations are reported in Table 6. In almost all columns the results

are statistically insignificant with positive coefficient results. The only variable that is negative and

significant at the 5 percent level is whether firms target innovations that is new to the market or

world in column 2. Interestingly, however, is the fact that also in this case the R&D variable in

column 1 is positive as in the case of Malaysia. When applying a 1‐year lag this result becomes

significant at the 10 percent level, which is also the case for the research collaboration variable in

column 5.

4.2.3 China

For China, we have different data which are not survey‐based. Data on innovation for China are

generally extremely hard to obtain. We are therefore forced to use data from the Thomson Reuters

data base that records information of private and public companies whose headquarters are in

China. Only two variables are recorded that seem relevant for our research purpose which are the

net intangible assets and R&D expenditure (both in USD). Years span a longer time period, which

therefore covers our entire duration of the data policy index, namely from 2009‐2019.11 Figure 11

provides an overview of the developments of our restrictiveness index for China. As one can see,

little variation can be detected for the country given that the level of restrictiveness is extremely

high throughout the entire period.

Figure 10 shows how the variable of R&D expenditures when divided by the number of employees

for each firm is correlated with our ICT‐services input coefficient. (Note again that the Coke &

Petroleum sector is excluded.) As one can see, the correlation is positive and tight and shows that

sectors intensive in the use of ICT services as part of their overall input structure have higher per

capita firm‐level expenditures on R&D. For the regressions, because we perform an LPM we

11 The Thomson Reuters data report data by fiscal year which may not entirely overlap with the calendar year of our restrictiveness index. Moreover, the database reports data calling each year “Fiscal Year 0”, Fiscal Year ‐1”, etc. In order to assign a calendar year value for each fiscal year, we assume that the first reporting year of the Thomson Reuters data base refers to 2019, which is Fiscal Year 0. Usually the end of fiscal years falls in the middle of the calendar year although this may vary by firm or country.

15

transform our variables into a binary mode between 1 in case firms report positive values on R&D

expenditures and intangibles; and a zero when firms do not report any values. Then, we also use the

size of R&D expenditures as well as the per capita expenditures in our regressions and perform OLS

to see if these results provide any further evidence.

Results are reported in Table 7. The first two columns show the results from the LPM regressions for

R&D expenditures and net intangible assets respectively. The results show that only the outcome on

the net intangible assets have a negative and significant sign. It therefore suggests that firms active

in ICT‐services intensive sectors reports lower levels of intangible assets when faced with higher

levels of data restrictions. Results are not significant or even have the negative expected coefficient

sign for R&D expenditures, but instead have a positive sign – consistent with the results for Malaysia

and Vietnam. However, when performing standard OLS regressions using similar variables, the

results in column 3 show that in this case R&D expenditures have a negative and significant sign. Yet

the intangible assets variable remains insignificant. The per capita variables in columns 5 and 6

neither show significant outcomes when performing OLS.

5. Conclusion

Given the importance of open markets for firms to successfully innovate with data, policy

restrictions on data, IPR, platforms and the telecom market are likely to have a knock‐on impact on

the digital innovation success of firms. Indeed, this paper finds that restrictive policies for a set of 10

East Asian countries regarding data, online platforms and other data‐related areas, are negatively

associated with the likelihood of firms to perform innovation, which appears to be particularly true

for sectors using a high amount of software. Therefore, less restrictive policies regarding data, IPR,

platforms and telecom do matter for firms to successfully innovate in the digital economy.

Using firm‐level data for 10 East Asian countries as well as using firm‐level data sets for three specific

countries in the East Asian region, this paper in particular finds that for countries with a more

restrictive set of data policies, firms are less likely to use foreign technologies through licensing as

part of their innovation activities. Moreover, the three country‐specific cases show that restrictive

data policies are negatively associated with firms’ likelihood to use intangible assets such as patents

and goodwill for performing innovation (in the case of Malaysia and China) and to develop

innovations as a result of R&D that are new to the market (in the case of Vietnam). For all cases, we

therefore conclude that open digital markets free from unnecessary and restrictive policies for data

and data‐related areas are likely to help firms to innovate.

Even though this paper only shows correlations, nothing suggests that causal inferences are unlikely

to be present too in the region. However, one should of course be careful with such conclusion. If

anything, this paper has shown that closed markets regarding data and other data‐related

technologies are unlikely to contribute to successful innovations in more digital sectors. Moreover, it

is telling that the restrictions picked up by our index also have significant bearing for firms using

intangible assets as part of their innovation process. Many countries around the world, including

East Asia, currently undergo significant transformations from a tangible economy based on goods

and commodities towards one that is increasingly based on intangibles such as services, data and

ideas. It is therefore of utmost importance that countries develop a friendly policy environment in

which firms can capitalize on these new economic developments while taking into account the

various legitimate non‐economic objectives that may exist in countries.

16

Bibliography

Arnold, J., B. Javorcik and A. Mattoo (2011) “The Productivity Effects of Services Liberalization:

Evidence from the Czech Republic”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 85, No. 1, pages 136‐

146.

Arnold, J., B. Javorcik, M. Lipscomb and A. Mattoo (2015) “Services Reform and Manufacturing

Performance: Evidence from India”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 126, Issue 590, pages 1‐39.

Bauer, M., F. Erixon, H. Lee‐Makiyama, M. Krol (2013) “The Economic Importance of Getting Data

Protection Right: Protecting Privacy, Transmitting Data, Moving Commerce”, Washington DC: US

Chamber of Commerce.

Bourlès, R., G. Cette, J. Lopez, J. Mairesse and N. Nicoletti (2013) “Do Product Market Regulations in

Upstream Sectors Curb Productivity Growth? Panel Data Evidence for OECD Countries”, The Review

of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 95, No. 5, pages 1750‐1768.

Christensen, L., A. Colciago, F. Etro and G. Rafert (2013) “The Impact of the Data Protection

Regulation in the EU”. Intertic Policy Paper, Intertic.

Ferracane, M.F. (2017), “Restrictions on Cross‐Border data flows: a taxonomy”, ECIPE Working Paper

No. 1/2018, European Center for International Political Economy, Brussels: ECIPE.

Ferracane, M.F. and E. van der Marel (2018) “Do Data Flows Restrictions Inhibit Trade in Services?”,

ECIPE DTE Working Paper Series No. 2, Brussels: ECIPE.

Ferracane, M.F., H. Lee‐Makiyama and E. van der Marel (2018b) “Digital Trade Restrictiveness

Index”, European Centre for International Political Economy, Brussels: ECIPE.

Ferracane, M.F., J. Kren and E. van der Marel (2018a) “Do Data Policy Restrictions Impact the

Productivity Performance of Firms and Industries?”, ECIPE DTE Working Paper Series No. 1, Brussels:

ECIPE.

Goldfarb, A. and C. Tucker (2012) “Privacy and Innovation,” in Innovation Policy and the Economy

(eds.) Josh Lerner and Scott Stern, / University of Chicago Press, pages 65–89. See also NBER

Working Paper Series No. 17124, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge MA: NBER.

Guellec, D. and C. Paunov (2018) "Innovation Policies in the Digital Age", OECD Science, Technology

and Industry Policy Papers, No. 59, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Horrace, W. and R. Oaxaca (2006) “Results on the Bias and Inconsistency of Ordinary Least Squares

for the Linear Probability Model," Economics Letters, Vol. 90, No. 3, pages 321‐327.

Manyika, J., S. Lund, J. Bughin, J. Woetzel, K. and D. Dhingra (2016) “Digital Globalization: The New

Era of Global Flows”, McKinsey Global Institute, Washington DC: McKinsey and Company.

OECD (2019) “East Asia Going Digital: Connecting SMEs”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/going‐

digital/East‐asia‐connecting‐SMEs.pdf.

van der Marel, E., H. Lee‐Makiyama, M. Bauer and B. Verschelde (2016) "A Methodology to Estimate

the Costs of Data Regulation", International Economics, Vol. 146, Issue 2, pages 12‐39.

17

Tables and Figures

Table 1: Categories of the data policy index and weights

Categories Type of measures Weighting

1 Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) 0.25

1.1 Restrictions related to the application process 0.20

1.2 Lack of clear copyright exceptions for the digital economy 0.20

1.3 Inadequately enforced of copyrights 0.20

1.4 Mandatory disclosure of business trade secrets 0.20

1.5 Mandatory encryption standards that deviate from int. standards 0.20

2 Cross‐border data flows (CBDF) 0.25

2.1 Ban to transfer or local processing requirement 0.25

2.2 Local storage requirement 0.25

2.3 Conditional flow regime 0.25

2.4 Infrastructure requirement (residency requirements) 0.25

3 Domestic use and processing of data (DP) 0.15

3.1 Minimum / maximum period 0.25

3.2 Data protection law in place 0.375

3.3 Impact assessment (DPIA) or Appoint a data protection officer (DPO) 0.125

3.4 Government access to personal data collected 0.25

4 Intermediate liability (IL) 0.10

4.1 Safe harbor for intermediaries 0.60

4.2 Identity / monitoring requirements 0.40

5 Content access (CA) 0.15

5.1 Blocking or filtering practices 0.40

5.2 Discriminatory use of license schemes & Bans on cloud services 0.40

5.3 Other restrictions 0.20

6 Infrastructure & Connectivity (INF) 0.10

6.1 Maximum foreign equity share for investment in telecom 0.50

6.2 Anticompetitive practices in the telecom 0.50

Source: Authors’ using Ferracane et al. (2018)

18

Table 2: Data policy index by category of restriction and country.

Country IPR CBDF DP IL CA INF Final index

Cambodia 0.10 0.00 0.09 0.06 0.06 0.07 0.38

China 0.23 0.25 0.09 0.10 0.15 0.09 0.91 Hong Kong SAR, China 0.03 0.00 0.00 0.06 0.00 0.00 0.09

Indonesia 0.18 0.20 0.07 0.06 0.08 0.07 0.64

Japan 0.05 0.10 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.04 0.20

Korea, Rep. 0.05 0.15 0.06 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.37

Lao PDR 0.05 0.00 0.06 0.10 0.00 0.05 0.26

Malaysia 0.08 0.05 0.04 0.00 0.14 0.05 0.35

Mongolia 0.10 0.00 0.03 0.06 0.06 0.03 0.27

Myanmar 0.13 0.00 0.09 0.10 0.08 0.08 0.47

Philippines 0.06 0.05 0.04 0.00 0.06 0.07 0.27

Singapore 0.01 0.10 0.06 0.00 0.12 0.03 0.31

Taiwan, China 0.09 0.08 0.02 0.00 0.06 0.07 0.30

Thailand 0.10 0.25 0.08 0.03 0.12 0.07 0.64

Vietnam 0.13 0.25 0.10 0.10 0.15 0.09 0.82

Note: Latest year taken for 2019. Abbreviations in each column are consistent with Table 1 which

provides the type of restriction falling into each category. Intellectual Property Rights (IPR); Cross‐

border data flows (CBDF); Domestic use and processing of data (DP); Intermediate liability (IL);

Content access (CA); Infrastructure & Connectivity (INF). The final column represents the overall

index score computed as the sum of all sub‐categories (i.e. column 2‐7)

19

Figure 1: Data‐intensities using US Census software expenditures over labor by sector (2010)

Source: US Labor Statistics and US Census.

Figure 2: Data policy index by country and type (2019)

Source: Authors’ using Ferracane and van der Marel (2018). Note: Latest year taken for 2019.

Abbreviations in each column are consistent with Table 1 which provides the type of restriction

falling into each category. Intellectual Property Rights (IPR); Cross‐border data flows (CBDF);

Domestic use and processing of data (DP); Intermediate liability (IL); Content access (CA);

Infrastructure & Connectivity (INF).

2.7

2.2

1.81.6

1.51.4

1.2

0.8 0.7

0.50.3 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.3

01

23

(D/L

) D

ata-

inte

nsity

US

Ce

nsus

& B

LS

Post &

Tele

com

Educa

tion

Insu

ranc

e

Other

tran

spor

t

Compu

ter

Financ

e

Com. e

quipm

ent

Chem

icals

Coke

& Pet

roleu

m

Food

prod

ucts

Mot

or ve

hicles

Rentin

g m

achin

ery

Other

bus

iness

Med

ical &

Opt

ics

Recre

ation

Non-Capitalized Software Expenditures over Labour (ISIC Rev 3.1)0

.2.4

.6.8

1R

estr

ictiv

enes

s in

dex

(0-

1)

CHN VNM IDN THA MMR KHM KOR MYS SGP TWN PHL MNG LAO JPN HKG

Data policy restrictiveness index for digital innovation

CA CBDF DP IL INF IPR

20

Figure 3: Level of data policy restrictiveness over time.

Source: ECIPE. Note: Countries include the ones covered under Figure 2. A weighted average is

constructed using GDP as weights in order to reflect size of market (some markets such as

China are huge, whereas others are small such as Hong‐Kong). Checks with population have

been done with similar increasing trend (albeit smaller).

0.2

.4.6

.81

Res

tric

tive

ness

inde

x (0

-1)

2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Level of data policy restrictiveness (weighted)

21

Figure 4: Level of data policy restrictiveness over time, by country

Source: ECIPE

0.2

.4.6

.81

0.2

.4.6

.81

0.2

.4.6

.81

0.2

.4.6

.81

0.2

.4.6

.81

2010 2015 2020 2010 2015 2020 2010 2015 2020

Cambodia China Hong Kong

Indonesia Japan Korea

Laos Malaysia Mongolia

Myanmar Philippines Singapore

Taiwan Thailand Vietnam

Res

tric

tiven

ess

inde

x (0

-1)

Year

22

Figure 5: Level of data policy restrictiveness and innovation score in digital services (2018)

Source: ECIPE and World Bank Enterprise Survey Database. Note: Latest year taken for 2019. The

indicator of innovation represents the “h5” question in the World Bank Enterprise Survey Database,

which asks whether the establishment introduced new or significant improved or introduced new

process of organizational or management structures over the last 3 years. For this figure, only the

sectors of Computer and related services; Publishing, printing and recorded media; and Post and

Telecommunication (ISIC Rev. 4) have been selected and averaged by country. The trend line is

plotted excluding China.

KHM

CHN

IDN

LAO

MYS

MNG

MMR

PHL

THA

VNM

0.1

.2.3

.4.5

Indi

cato

r of

inno

vatio

n in

dig

ital s

ecto

r

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1Restrictiveness index (0-1)

Data policy index & Digital innovation

23

Figure 6: Level of data policy restrictiveness and ICT‐services imports (2018)

Source: ECIPE and World Bank Development Indicators. Note: Digital services include computer,

communications and digital services such activities as international telecommunications, and postal

and courier services; computer data; news‐related service transactions between residents and non‐

residents; construction services; royalties and license fees; miscellaneous business, professional, and

technical services; and personal, cultural, and recreational services. The trend line is plotted with

China included.

KHM

CHN

HKGIDN

JPN

KOR

MNG

PHL

SGP

THA

2030

4050

60C

ompu

ter

serv

ices

(%

of

com

me

rcia

l ser

vice

impo

rts)

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1Restrictiveness index (0-1)

Data policy index & ICT-services imports

24

Table 3: LPM results for regressions as correlations

(1) (2) (3) (4)

h1 h5 e6 h8

Index * ln(D/L) 0.016 0.025 ‐0.041** 0.003

(0.310) (0.215) (0.025) (0.881)

Constant 0.265*** 0.432*** 0.135*** 0.188***

(0.000) (0.000) (0.000) (0.000)

Observations 8775 7694 7654 7773

R2A 0.142 0.140 0.033 0.143

R2W 0.000 0.000 0.001 0.000

RMSE 0.397 0.454 0.380 0.359

Note: * p<0.10; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01, representing p‐values not standard errors. The dependent

variable h1 stands for whether a new product / services has been introduced over the last 3 years?

Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable h5 whether the firm has new process introduced over the last 3 years?

Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable e6 whether the firm has used technology licensed from a foreign

company? Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable h8 whether the firm spent on new R&D (excl. market research)

in last 3 years? Yes = 1 | No = 0. The term (D/L) is comprised of non‐capitalized computer software

expenditures over labor. Fixed effects by country, sector and year applied separately. Robust standard

errors clustered by country‐sector.

Table 4: Probit estimates for regressions as correlations

(1) (2) (3) (4)

h1 h5 e6 h8

Index * ln(D/L) ‐0.014 0.121 ‐0.336*** ‐0.122

(0.887) (0.283) (0.001) (0.297)

Observations 9988 8855 9276 8933

LR chi2(10) 1193.96 1072.52 215.74 947.12

No. groups 32 32 24 12

Log likelihood ‐4690.1 ‐5207.8 ‐4045.7 ‐3475.1

Note: * p<0.10; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01, representing p‐values not standard errors. The dependent

variable h1 stands for whether a new product / services has been introduced over the last 3 years?

Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable h5 whether the firm has new process introduced over the last 3 years?

Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable e6 whether the firm has used technology licenced from a foreign

company? Yes = 1 | No = 0. The variable h8 whether the firm spent on new R&D (excl. market research)

in last 3 years? Yes = 1 | No = 0. The term (D/L) is comprised of non‐capitalized computer software

expenditures over labor. Fixed effects by country, sector and year applied separately. Data is grouped

by sector.

25

Figure 7: Correlation between Innovation Score and IO Coefficient of ICT‐services (2015), Malaysia

Source: World Bank. Note: the IO Coefficients are computed as the fraction of ICT‐services usage in

total input use for each industry in Malaysia using IO tables. Innovation represents a composite

indicator varying between 0‐1 of all innovation variables from the Malaysian firm‐level dataset (see

text for further explanations). The fitted values line is plotted on the basis of excluding Coke &

Petroleum and Other manuf. & Repair.

Figure 8: Malaysia’s level of data policy restrictiveness (2010‐2015)

Source: ECIPE

Basic metals

Chemicals & Pharm.Coke & Petroleum

Computer & Electr.

Electrical equipment

Food & Beverages

Machinery and equip.

Metal products

Motor vehicles

Non-metallic mineral

Other manuf. & Repair

Other transport

Paper & Printing

Rubber & Plastics

Textiles & Wearing

Wood products

.02

.04

.06

.08

.1In

nova

tion

Sco

re

0 .001 .002 .003 .004 .005IO Coefficients (Domestic)

Innovation Score and IO Coefficient

0.1

.2.3

.4D

ata

inno

vatio

n re

stric

tiven

ess

2010 2015

Level of data innovation restrictiveness

26

Table 5: LPM estimates for regressions as correlations for Malaysia

(1) (2) (3) (4)

R&D Intg. Assets

Purch. Intg. Assets

Used Intg. Assets

Prod.

Index * (D/T) 1.296** ‐0.754 ‐0.090** ‐0.017 (0.043) (0.177) (0.045) (0.572)

Constant ‐0.006 0.126*** 0.011*** 0.005** (0.897) (0.009) (0.004) (0.043)

Observations 39206 39206 39206 39206

R2A 0.476 0.245 0.067 0.064

R2W 0.005 0.002 0.000 0.000

RMSE 0.216 0.214 0.059 0.060

Note: * p<0.10; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01, representing p‐values not standard errors. The term (D/T) is

computed as the proportion of ICT‐services as input in total input expenditure for each sector. R&D is

Research and Development activities in thousands RM. Assets Purch. is other assets (such as patent,

goodwill, work in progress) new purchases including imports of both new and used assets in thousands

RM. Assets used is other assets (such as patent, goodwill, work in progress) purchases of assets

previously used in Malaysia including those reconditioned or modified before acquisition in thousands

RM. Assets prod. is other assets (such as patent, goodwill, work in progress) assets produced by the

establishment for its own use, the costs of all works done during the year should be recorded in

thousands RM. All dependent variables are transformed into a binary mode varying between 0‐1 with

a value of 1 assigned for any value > 0. Robust standard errors clustered by sector. Fixed effects by

firm, sector and year are applied. A lag of 1 year is also applied.

27

Figure 9: Correlation between Innovation score and IO Coefficient of ICT‐services (2013), Vietnam

Source: World Bank. Note: the IO Coefficients are computed as the fraction of ICT‐services usage in

total input use for each industry in Vietnam using IO tables. Innovation variable in this figure

represents a composite indicator measuring (i) whether the firm undertakes R&D; (ii) whether R&D

is new to the market or world; (iii) whether the firm has national and international patents; (iv)

whether the firm is involved in any research collaborations. The fitted values line is plotted on the

basis of excluding Paper & Printing. Coke & Petroleum is omitted because of lack of credible data.

Figure 10: Vietnam’s level of data policy restrictiveness (2010‐2013)

Source: ECIPE

Basic metals

Chemicals & Pharm.

Computer & Electr.Electrical equipment

Food & Beverages

Machinery and equip.

Metal products

Motor vehicles

Non-metallic mineral

Other manuf. & Repair

Other transport

Paper & Printing

Rubber & Plastics

Textiles & Wearing

Wood products.02

.04

.06

.08

.1In

nova

tion

Sco

re