‘Digging-up’ Utopia? Space, practice and land use heritage

-

Upload

david-crouch -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

3

Transcript of ‘Digging-up’ Utopia? Space, practice and land use heritage

Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum

�Digging-up� Utopia? Space, practice and land use heritage

David Crouch a, Gavin Parker b,*

a University of Derby, Kedleston Road, Derby DE22 1GB, UKb Centre of Planning Studies, Department of Land Management, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading RG6 6AW, UK

Received 23 April 2001; received in revised form 4 September 2002

Abstract

In this paper we explore history and heritage mobilised to do service for marginalized interests. We discuss how resources, such

as, place, texts, artefacts and practice are drawn upon to forward particular political interests. Touching on recent work in non-

representational theory we suggest that more attention be paid to the micro-politics of doing and link more formal action to that of

�everyday� practice. The examples used show how particular actors draw on history and heritage to advance their positions and howtheir performances reinforce claims based on alternative practices. The examples used illustrate how this involves the notion of

�reclaiming� historical action, historical texts and historical place. In particular how this relates to land and specifically in this paperthe metaphor, representation and practice of �digging�.� 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Politics; Space; Time; History; Heritage; Representation; Practice; Land; Claims; Citizenship; Doing; Alternative living

1. Introduction: digging and doing digging

Society, then, is unrepresentable: any representa-

tion and thus any space is an attempt to constitute

society, not to state what it is (Laclau, 1990, p. 82)

Some pasts are the liveliest instigators of the pre-

sent and the best springboards of the future When

the cathedrals were white (Le Corbusier, 1937)

In this paper we wish to highlight the way that history

and heritage is being used explicitly to rupture norma-

tive and dominant conceptions of action, space and land

use in the UK, also, how practice is sometimes appro-

priated for that purpose. Thus practice, it is contended,

provides the fabric of the political dimension as well as

the social. In terms of our focus––heritage places––we

argue that this often involves the selective use of historyto substantiate heritage credentials (cf. Samuel, 1994;

Lowenthal, 1985, 1994) and the framing of history

through an array of practical and representative action

and artefacts.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Parker).

0016-7185/03/$ - see front matter � 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00080-5

In this area of research we pursue a slightly less well-

trodden path in looking at how the past may be used as�ideological messenger� by marginalized groups and in-terests (Hollinshead, 1997, p. 177). In congruence with

this approach Walter Benjamin argued for a �blastingopen of the continuum of history� and �brushing historyagainst the grain� (cited in Game, 1991, p. 26). We takethis as an invitation for activists, as well as academics, in

seeking to highlight marginalized histories and reveal

how such histories are used to make representationsabout the future. In the same breath we do, however,

accept that attempts to challenge dominant distributions

of power and of rights tend to be attritional at best in

their effects.

In this paper we also examine the interjacency of

overt or cognisant politics and �practical� or non-cogni-sant activities. In this way we highlight that doing, or

more broadly �mundane activity� is potentially of the(micro)political. Thus the paper, while highlighting po-

litical action through �digging� points to materiality andthe appropriation of otherwise practical actions and

artefacts in rendering the banal as representational,

powerful and agentive.

We begin by looking at the way that contemporary

politics and citizenship are increasingly fluid, fragmen-

tary and mediated. This allows for multiple spaces of

396 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

resistance and challenge and we argue that practice

refigures the identity of both the land and the agent.

Through such refiguration attempts to influence wider

social conditions are also enacted. We highlight throughcase study narratives how a radical group has recently

looked to use alternative, neglected or marginalized

versions of history. How, by associating to more main-

stream aspects of history, they portray place and prac-

tices as �heritage� in order to further their interests

or claims. Enacting practice, through performance,

through doing achieves this (see Joseph, 1999; Thrift

and Dewesbury, 2000; Nash, 2000; Becker, 2000).In this process alternative trajectories can be seen as

being wrapped into notions of heritage that serve to

legitimise such messages. In this context we seek to

emphasise and link the process of �doing� alternativesand the micro-political status of practice and its repre-

sentation. In this way we address a rather neglected part

of the geographical literature in highlighting how per-

formativity and heritage has been explicitly deployed forpolitical ends in the UK. This is in contrast, or in sup-

plement, to other implicit opaque or subconscious en-

rolments of suitable pasts (see, for example; Friedman,

1994; Samuel, 1994; Lowenthal, 1985, 1994; Chesters,

2000a).

Thus we engage with the expression of self through

the landscape we construct and constitute in the process

of doing. Ingold identifies a process of dwelling wherebyencounters with objects, individuals, space and the self

progress life (Ingold, 2000). He distinguishes between

ideas for things, space and so on, as prefigured and

determinate, and the motor of �dwelling� that sustainsthe present and future, from which contemplation and

new possibilities of reconfiguring the world, in flows, can

occur.

Making embodied practice enables individuals towork their awareness of �being somewhere�; their senseof existing significance of actions, things and cultural

contexts; and having something to do through an en-

counter with inhabited volumes of the spaces and their

content. These everyday routes through the world are

worked in a practical geographical knowledge, a mate-

rial or embodied semiotics (Game, 1991; Crouch, 2001).

Thus selves can construct their own significance ofthings. The emerging process does not happen in de-

tachment from surrounding cultural contexts and their

representations, for example landscape. Our attempt at

synthesis indicates that such doings are significant, they

may be appropriated to signify and they may also be

practical actions that do signify.

Memory too can be refigured. Crang has argued the

processual, constituted character of space in practicetemporally contingent in open-ended multiple flows

(Crang, 2001). As things are done, other �events� areremembered and replaced into and through the present.

Memory is also temporalised and can reinvigorate what

one is doing now, but also it is reinvigorated, it can be

engaged afresh and can be rerouted in the �now� (Crang,2001). Memories colour the practice of the now, but not

in a rerun of the past. Performing time/spacing appearsto be more than a linear �moving on� from ideas or frommemory, and memory is operated in the active character

of what is done. As Bachelard argues, we have �onlyretained the memory of events that have created us at

the decisive instants of our pasts� (2000, p. 57). These aredrawn into a focus in moments of significance. Some-

times such significant times are realised as later events

make them important. When individuals speak of whatand how they �do� they compile events reduced to aninstant. Although we �may retain no trace of the tem-poral dynamic of the flow of time� (2000, p. 57). In thedoing, moments of memory are recalled, reactivated in

what is done, and thus, may be drawn upon in new

combinations of signification. It is less that memory is

practiced in repetition than it is in doing. It is in em-

bodied practical encounters that it is made sense of.Thus it is argued that memory and the immediate are

performed as complexities of time. Memory is worked

again and again, differently, and embodied thereby,

grasped and wound up in body-performance and inter-

action with place.

2. Present, pasts and futures in political action

Both Beck (1998) and Bauman (1998) contend that

society is obsessed with the future, and while we do not

wish to critically engage with the basic contention about

if this is true, we do explore how groups have influence

on the future. In particular in this paper, in terms of

radical or alternative groups who are interested in af-

fecting trajectories of land use and its regulation. Wedemonstrate that, in seeking to represent alternative

futures, groups explicitly draw on history as heritage in

order to undermine current structures and practices and

promote alternatives. In conceptualising the contrasting

examples used below we deploy ideas of performance or

embodied practice (see Crouch, 2001; Thrift, 1996, 1999;

Nash, 2000) to emphasise how everyday micro-politics

can affect [shared] heritages and through which attemptscan be made to reorganise time and space as memory is

mined, refigured and re-presented.

The prompt for this paper then lies in the way in

which heritages, viewed in a deconstructed fashion, in

terms of multiple aspects, fragments or selected readings

of the past, are being used and deployed as part of

alternative political projects. Lowenthal (1994, p. 302)

argues that;

The past is everywhere a battleground of rival at-

tachments. In discovering, correcting, elaborating,

inventing, and celebrating their histories, compet-

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 397

ing groups struggle to validate present goals by ap-

pealing to continuity with, or inheritance from, an-

cestral and other precursors.

Foucault (1977), in discussing the way that political

agents attempt to influence others, proposes that indi-

viduals are engaged in preparing �counter-memories�; �ause of history that severs its connection to memory, itsmetaphysical and anthropological model, and con-

structs a counter-memory––a transformation of history

into a totally different form of time� (Foucault, 1977,p. 160). In reflecting on this Hollinshead argues that the

past is generally acquired by the ruling and possessing

classes of privilege––that they �steal control of the past�(1997, p. 178). He does acknowledge that attempts to

wrest such control back do occur, but they tend to beless well documented.

This is perhaps to be expected, as authorship has also

tended to rest with those same classes of privilege. For

example Jeffries (2000) reminds us that George Orwell,

in his book 1984, foresaw that the control of history was

an important part of controlling the present (and

therefore future trajectories). 1;2 In that novel the pos-

sibility of counter-memory is not eradicated. This isdespite the best attempts of The Party to erase incon-

gruent facts, as potential future vehicles for challenge,

by editing records as soon as they became inconsistent

with prevailing Party statements.

In this paper we suggest a reflexive, knowing and

partial use of history as heritage to highlight radical

histories––a process of �past-modernisation�. For uscounter-memory can involve the selective recollectionor imagination of past events. This helps assemble the

resources for representations that challenge classes of

privilege and the structures that exist to protect power

and exclusivity (see Hartsock, 1987).

Given that politics is being increasingly mediated

numerous articles relating to what has been termed

�post-modern� and aestheticised politics have been writ-ten that highlight this self-aware, ironic form (see; forexample, Routledge, 1997; Chesters, 2000a,b; Anderson,

1997). Direct action protest during the 1990s was in-

creasingly dominated by its mediation, often such action

was significantly mobilised around an everyday micro-

politics of practice (Domosh, 1998). We assert that the

1 In line with our thesis Jeffries actively deploys Orwell�s text as anhistorical and legitimating resource. In this sense many references in

texts are attempts to bring distant deposits of authority to bear on the

present (see, also Samuel, 1994; Latour, 1999).2 In 1984 there are numerous examples where artefacts, practices,

even sounds of the everyday (and/of the past) resonate in the text (for

example; the bells of St. Clements, the glass paper-weight) and are

regarded by Winston Smith and by The Party as subversive, and read

here as micro-political representations/embodiments.

representation of protest by the media, and vice versa,

such use of the media by protesters, is a feature of late-

modern politics. This is a politics of reflexivity and

ironicism, which draws on diverse sources and referents,as well as material artefacts. This approach revels in the

mixing of disparate ingredients to produce a multifari-

ous representation of the world and particular issues.

In that process however, such actions or projects run

the risk of being �captured�, depoliticised or �used forsedative purposes� (Hollinshead, 1997, p. 179). We ac-knowledge the point that previously radical or subver-

sive discursive resources may lose their transformativepotential as a result of normative framing as heritage.

It is contended that heritage, like space, is contingent

and subject to constant renegotiation and reinterpreta-

tion.

3. The idea of lay heritage in time–space reorganisation

and relational materialism

Urry (2000, p. 115) when reflecting on the work of

George Herbert Mead, points out that reality only exists

in the present and �what we take to be the past is nec-essarily reconstructed in the present, each moment of thepast is reconstructed in the present�. It is contended thattimes and histories are multiple; they are capable of

being reflexively looped and folded, referenced and se-

lectively deployed (Crang, 2001). Increasingly, referen-

tial and observable spaces for difference and alternative

claims-making have developed as civil rights agendas

have developed and as groups become better educated

and networked (see, for example; Urry, 2000; McKay,1998; Hannigan, 1995; Etzioni, 1995). Such spaces and

technologies have enabled a range of interests to pro-

mote their positions creatively, sometimes ironically, by

revisiting, challenging and reinterpreting �facts� and il-luminating shibboleths.

Key authors such as Foucault, Baudrillard and

Lyotard have detailed the constructedness of modernity

and how cultural values influence our perceptions ofplace, self, and of history. Their post-structural critiques

have generated healthy uncertainty; adding to a wider

comprehension of the constructedness and complexity

of modernity. In related fashion Gramsci too highlights,

indeed encourages, consideration of how folklore may

be used to contest �official� conceptions of the world(1971, p. 323). �Other� histories can be more readilybrought into the present to illustrate marginal ideas.Imprints are being �dusted down� and enacted or givennew amplification. We argue in this paper that con-

temporary radical and marginalized politics in the late

1990s has begun to look increasingly and more explicitly

to history and heritage as a political resource in order to

perform institutions and other publics in attempts to

reorient the future.

398 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

3.1. Time, memory and heritage

We confront how time and past practice qua heritage,

and its portrayal as �heritage�, is being used explicitly todo service for political projects and practices; how the

construction and reconstruction of the past in the pre-

sent hold implicit political connotations. In terms of

time 3 we follow recent debates on the complexities,

flows and circulations of time enunciated by Bachelard

(Crang, 2001), where memory is open to persistent re-

figuring. In that sense where memory is counter-memory

both contra to the dominant and contra to alternativesand hence an interplaying of power-laden semiotics.

While there has been recognition in the literature that

heritage brings the past into the future and may �trans-port� the agent into the past (sic) there has been lessattention paid to the political possibilities of deploying

heritage oppositionally (Gramsci, 1971; Hollinshead,

1997; Parker and Wragg, 1999; Ravenscroft, 1999). This

type of retrieval and mobilisation presents opportunitiesto revisit, reconfigure and indicate alternative trajecto-

ries for the future. Specifically here, we focus on exam-

ples that relate to challenges about appropriate land use

and governance in the UK.

Our conceptualisation of politics is wide, incorpo-

rating personal actions taken and practiced as part of

lifestyle or belief systems. Using examples drawn from

recent political actions we show how groups and indi-viduals seek to mobilise parcels of �significant� time andrelated artefacts in order to progress and consolidate

their projects. In this vein it is noticeable how groups

such as Reclaim the Streets and The Land Is Ours

(TLIO) in the UK, draw on what has gone before: they

are �reclaiming� or reexamining the past, holding upversions and actions, texts and spaces as important

legitimation resources in arguing for political change(again, specifically for change in the governance of land

use). Of particular interest here is the process of re-

claiming or refiguring particular versions of heritage

into lay heritage through performance.

Heritage may be conceptualised as the crystallisation

of recurrent, dominant and �new� representations of pasttime, practice and place. Thus heritage can amount to

the temporal outcome of human projects (see Giddens,1984), alongside their relation with non-human pro-

jects, Philo and Wilbert (2000). Actors can call upon

temporally distant resources to mobilise and enact pre-

sent and future action and therefore to determine

futures, and thus put forward alternative claims to le-

gitimacy (Lowenthal, 1994). This may amount to a re-

3 There is a wider time dimension to be flagged here, but while not

underestimating its importance, this paper avoids an extensive

assessment of the wider debate about time (see, for example; Urry,

2000; Adam, 1995; Nowotny, 1994).

flexive post-historicist �past-modern� project where

fragments of history and particular spaces are intro-

duced and represented in the hope they have influence.

Place and materially land has become differentially andsubjectively reified, such valuations are intrinsic to the

range of activities that may be legitimately pursued on

particular sites. Attempts to challenge land use may be

read as challenges to �what society is� as much as at-tempts to reconstitute society into the future. At a basic

level then land is an anchor for both practice and poli-

tics. It can act as the stage for representations. Bender

(1993, p. 275) noted this in relation to differing con-ceptions of Stonehenge and how different conceptions of

the �preferred future� jostle for position and are deployed�out of time� and place:

. . .a cacophony of voices and landscapes throughtime, mobilising different histories, differentially

empowered, fragmented perhaps, but explicablewithin the historical particularity of British social

relations and a larger global economy.

Space, particularly land, can be a key object of this

process in the sense of the way that space may be

claimed and performed. Its making and representationsare refigured in a process of ownership. Ownership may

be considered in terms of space engaged in action and

ideology in a process of empowerment rather than in

terms of financial or legal position (Wiltshire et al., 2000;

Bromley, 1998). Thus the ownership of particular

readings, of spaces, may be contested. �Ownership� maybe conceptualised outside legal and financial territories,

as something (through which) individuals and identitiesare forged, or felt and where ownership may be under-

stood in terms of time and energy and be self- and inter-

subjectively-invested in processes of exploring differing

ideas of ownership. This implies the nascency or �be-comingness� of cultural ownership, territorialisation andthe development of alternative rights-claims. When

versions of ownership such as this are cornered in dis-

putes over matters of legal ownership, particularly in-tense identities may be forged. And as below competing

or oppositional claims are generated.

Cultural practice is central here. Archaeological

precedents were used to formalise �customs and traditioninto instruments of government and a defined code of

laws� (Bender, 1993, p. 260). Such formalisations are,however, predicated on dominant readings. People may

not feel able to participate in �regular� politics due totheir own feeling of (dis)empowerment and for reasons

of time, complexity and access. They may simply not be

inclined to do so by the available forms of politics they

know. Instead they may work through, and into, their

lives an everyday politics in ordinary activities and

practices of tactics in the negotiation and (re)discovery

of identities and intersubjectivities that include other

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 399

people and spaces. 4 In this sense, spatial practices may

overflow the boundaries of rationality and abstraction

and engage an embodied imagination through which

they may subvert ordinary relations, meanings andstructures. Therefore implicit in this discussion is also the

way that micro-politics influence policy and other prac-

tice (see Domosh, 1998; Latour, 1999; Parker, 1999a).

Our concerns over ownership become mobilised through

what Domosh (1998) has referred to as a micro-politics

of everyday life, whereby individuals, and groups, work

their identities, values, human and social relations

through a series of tactics, of representations. In this deCerteauian sense they may tactically appropriate arte-

facts, their meaning and their heritage. This propensity

emerges in the recent work on non-representational

geographies to which we now turn.

5 �Active�may be interrogated further, by this we infer the possibility

3.2. Non-representational theory and ‘everyday resis-

tance’

In the following paragraphs we discuss components

of a more practical and also substantively shared

working of the significance of heritage and its material

objects. Whilst everyday practice may be reflexive inways that remix, and contest, norms of identity and

reference, they may be also manoeuvred in a more

bodily way. Crossley (1995) has identified the signifi-

cance in everyday life of encountering the material world

through looking, listening and touching, whilst still at-

tached (at least semi-attached) to acquired, cultural and

habit-based forms of conduct. Making sense of the

world can happen, then, through a more sensuousdoing. The individual collects, lifts, experiences, bor-

rows, experiments, feels and imagines with numerous

resources. They are facets gathered in a practice and

expression of the self and in relation to others.

Artefacts and �heritage� are important in this process.As Radley (1990) has observed, the artefacts of our

surroundings, past and present, are used to inform our

memory that is always in process, in a process ofreworking our own and inter-subjective history. In-

dividuals encounter these artefacts in a bodily way,

we express ourselves �in the landscape� through ourphysical conduct. Individuals know, value and practice

the landscape through desires and emotions. History,

through its everyday presence metaphorically and ma-

terially is reworked and can be subverted. The embodied

encounter reworks our knowledge in the way thatShotter (1993) talks of ontological or practical know-

ledge, negotiating in a process that is simultaneously

discursive and pre-discursive, where mental reflexivity is

4 We may speculate that ethical or politicised consumption practice

is a reflection of this (see Parker, 1999b).

perpetually disturbed by embodied encounters (Crouch,

2001; Giddens, 1984).

Thus it is possible to refigure knowledge, memory and

pre-figured meaning through our own active (that ismental/bodily) involvement. Encounters like this provide

openings that can disrupt received wisdom [sic] more

actively than textual or �political� response alone. Whilstthere is a tendency in some literature on performance to

underplay and override the political potential of per-

formance (Dewesbury, 2000) there is an evident potential

in performance towards a negotiation of �holding on� and�going further�, the latter imbued with the possibility ofwhat Grosz (1999) calls �the unexpected�, the challenge,the political. Heritage is often pursued in the sense of

holding on (see Samuel, 1994; Lowenthal, 1985). In this

discussion however, it is particularly in terms of �goingfurther� and in engaging in micro-politics through per-formance that concerns us.

Thus it becomes possible to argue that landscape, its

sites and its representations of history, is practiced; notonly observed, read or understood. Practice includes

active bodily engagement, wandering round, knowing

�with both feet�. 5 We express ourselves through thelandscape we construct in the process of doing.

Individuals inhabit and constitute spaces in terms of

power relations. Crossley argued that through embodied

ways of living the individual provides �necessary groundthrough which to rethink� those relations (1995, pp. 59–60). Through practice they engage, discover, open, ha-

bitually practice and enact, reassure, become, create.

Furthermore there is the possibility of individuals

potentialising the unexpected, complexity and potenti-

alities (Dewesbury, 2000). These several strands of

happening are negotiated and �made sense� in complextime as body-thinking beings. This process of negotiat-

ing leaves room for the individual to �take it� where s/helikes. In the apparently routine there can be the trans-

formative, as Domosh suggests routine practices can

generate their own micro-politics (1998).

This may provide significant grounds for contestation

through landscape and the meaning constituted of

landscape through practice and bodily encounter. This

may be considered part of a diffuse citizenship where the

agent feels place and their own action in relation toplace, or territory. Spatial practice, political events and

artefacts from the past may be conjoined, synchronised

or otherwise assembled in order to do service for par-

ticular group interests. This may mean developing and

configuring ideology, not prefigured but adapted and

of a range of intents and realisations of doing. In this context we

include engagement physically with particular elements of the envi-

ronment. Sometimes such practice does �make� or structure place––thecustomary use of a footpath becoming a legally recognised Right of

Way is a good example of this.

400 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

�subverted�. The significance of refiguring and subvertingour own history is discussed by Game (1991) in terms of

places visited, landscapes encountered and the burden of

their mediated representations. Bodily engagement withplaces in her work involves a desire �to know what

cannot be seen� in a process of bodily, as well as mental/imaginative, discovery. Each of the landscapes she en-

counters has its official history mediated as �heritage�.For her, the complex and nuanced means of encounter

render those contexts, accessible in tourism brochures

and heritage trails, merely one resource of many, and a

resource that can be folded and torn, disrupted and castaside. However, in taking this argument further we do

not argue an opposition between the handling of rep-

resentations and the lay knowledge of performance.

Instead, representations are considered as negotiated

and negotiable; in performance, representation is refig-

ured and also (re)constituted (see Nash, 2000). In each

of the examples considered below earlier representations

are worked and engaged in taking them further, or indifferent directions, in a process of becoming and of

making (Grosz, 1999; Pred, 1984).

4. Narrative examples: digging in, up and back

We present two linked examples of the use of historyand heritage deployed to mediate political projects. Ele-

ments of both of the examples were engineered by

TLIO, a primarily UK-based land reform group and a

constituent part of the radical environmental movement

(see TLIO, 1998, 2000; Monbiot, 1998; Halfacree, 1999;

Chesters, 2000a; Parker, 2002). The examples illustrate

how the metaphor and practice of � digging� 6 is used topresent alternative possibilities for land and its gover-nance. This also presents us with the possibility of dig-

ging and other apparently mundane activities as latently

micro-political. We consider the overt use of heritage,

and deployment of time as heritage, through �persuasivestorytelling� (cf. Mandelbaum, 1991; Throgmorton,1992; Grant, 1994) and both past and future �claims-making� (Hannigan, 1995; Samuel, 1994; Parker, 2002).

6 Here �digging� is referred to in three ways; first as a practice derivedfrom the 17th Century radical group The Diggers or the True Levellers

led by Gerrard Winstanley (see Sabine, 1973). The name relates to their

challenge to established laws and custom by cultivating common land

in Surrey, and subsequently elsewhere i.e. through the act of digging

the earth. The second use of the term relates to the contemporary use

of the term in reflection of this historical politicisation of �digging�through recent attempts by radical groups to repoliticise the act;

linking digging to a red/green or red/black agenda for land use and

environmental consciousness. The third way (sic) is to think of history

as a resource that can be drawn upon differentially by multiple interests

to forward their claims or stabilise/destabilise networks, in this sense to

�dig-in to history� (see, for example; Hollinshead, 1997; Parker andWragg, 1999).

The examples indicate, in series rather than in parallel,

how heritage can be made to fit political/environmental

ends and how heritage and �doing� are of themselvesperformances of environmental and political agendas.Historical resources can thus act as reservoirs of la-

tent, preserved power. This may be particularly true

where texts and other artefacts, landscape, space, places

(qua heritage) can be represented consciously, subcon-

sciously (or unconsciously). In the first example it is the

existence and explicit use of historical texts that are

significant components in the process of garnering sup-

port and legitimising action––in providing the script andthe theatre. Where this is done consciously the reflexive

use of history can represent alternative practice and

place. The examples discussed relate to actually disput-

ing ownership, rights, and management and illustrate

�action spaces� (Goffman, 1967; Bey, 1991) as �historic�spaces.

History is frequently situated, idealised and practiced

in terms of space. Friedman (1994) sees the constructionof the past as �an act of self-identification� and from theperspective of interest groups and marginalized political

groups what better than to (re)appropriate space and

artefacts that have been implicated in accounts of

(radical) actions and then to reconstruct these compet-

ing histories, these imagined counter-memories? They

can then be performed as �living history� and as anexplicit challenge to the dominant anticipation of thefuture.

The mediation of history over-reaches the limits of

popular mediated culture and the role of formal

knowledge/information �filters� and becomes one of

mediated practice. Through practice that is at once

mental and embodied, individuals reflexively refigure

their worlds, interacting contexts that include their own

action (Crouch and Matless, 1996; Barnett, 1999). Game(1991) refers to this process as one of materialist semi-

otics, through which process, everyday or embodied

semiotics (see Crouch, 2000) is figured and refigured.

Historical artefacts, memories and learnt histories are

part of this reconfiguration. It is also possible that once

such possibilities are uncovered a desire for others to

know and learn, or to attack rival alternatives is raised.

Past actions become resources to be drawn upon forpolitical engagement. Two examples of such practices

are outlined in this section.

The narratives presented relate to alternative visions

and practices being enacted, or reenacted, to contest

dominant land practices through a mobilisation of both

radical history and a discourse of heritage. Both of the

examples relate to TLIO actions that have been effected

during the mid to late 1990s as part of a campaign toraise the profile of land rights issues in the UK (see

TLIO, 1995, 2000; Monbiot, 1998; also, Halfacree, 1999;

Jeffries, 2000). The first examines the way that historical

referents are employed in the contemporary in order to

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 401

further a particular interest. The focus is a �heritage� siteand texts that underpinned the authenticity of the site

and the mobilisation of a particular heritage. The sec-

ond relates to the iconography and use of a poster de-rived from the Dig On for Victory image produced

during WWII in the UK and to the practice of digging

by allotment holders.

9 The Stone was sculpted by the artist Andrew Whittle.10 One of the orators was the actor who played Winstanley in the

4.1. Diggers’350: ‘Doing Space’ at George Hill/St.

George’s Hill

On April 3rd 1999 a combined march, commemora-

tion event and occupation of St. George�s Hill in Surrey,England was orchestrated by a group known as Dig-

gers350, closely associated to the land reform group

TLIO (Bebbington, 1999). 7 They intended to practice

�Digging� by planting root crops and enacting and imi-tating the recorded practices of the Diggers or �TrueLevellers� of 1649–1651 (Petegorsky, 1995; Bradstock,2000).

In the mid-seventeenth century �George Hill� nearWeybridge, Surrey was open common land. By 1999 the

site, by then St. George�s Hill, had been developed into ahighly exclusive private estate and golf course, thus

making for an ironic, but powerful, juxtaposition to

historical events and practices that had taken place therein 1649. The primary motive for selecting the Hill was

that in 1649 it was recorded as being occupied by the

Diggers who controversially practiced � Digging�. 8 Theycultivated common land on the Hill as part of an at-

tempt to set up an early utopian commune. In particular

the 17thC Diggers aimed to settle and make productive

use of the common or �waste� land. Although short-lived(see Taylor, 2000; Petegorsky, 1995) their actions rep-resented a direct challenge to the emerging Cromwellian

regime over its position on land rights and the �stake� (ornascent social contract) that was to be afforded to the

common people of England, this perhaps an early ex-

ample of a group attempting to realise the dividend of

revolution. More radical than the Levellers, they aimed

to bring all (English) land into a form of �commonownership� (see Sabine, 1973; Bradstock, 1997, 2000;Boulton, 1999). Hence historians have viewed the Dig-

gers (and in particular one of its leaders Gerrard Win-

stanley) as early communists that are said to have

influenced Marx�s thinking (Bradstock, 1997, 2000).Gerrard Winstanley has been used as a focus for

TLIO action for reasons of his philosophy and practices.

7 Diggers350 were, in effect, a subgroup of TLIO with the organisers

of the April 1999 Diggers350 march also being involved with TLIO

(see TLIO, 1999, 1998). A precursive occupation of land nearby had

been actioned by TLIO in 1995 as one of their first land occupations

(see TLIO, 2000). The 350 relates to the 350th anniversary of the

Diggers beginning their commune at St. George�s Hill in 1649.8 Here Digging as the practice of the eponymous 17thC group.

This is underpinned by the numerous writings that he

produced and which have survived in textual form to be

amplified by historians (see Hill, 1996; Petegorsky, 1995;

Sabine, 1973). His pamphlets are drawn upon by TLIOand the Diggers350 group, among others, as a political

resource. For example TLIO use the quote �for action isthe life of all, and if thou dost not act, thou doest

nothing� (taken from Winstanley�s Watchword to the

City of London published in 1649, see TLIO, 1999, 2000;

Sabine, 1973) as a rallying or mobilising piece of

rhetoric. T-shirts produced for public sale by TLIO also

carry another of his quotes and the TLIO website isladen with references to both the Diggers and the Lev-

ellers. Winstanley�s texts were politically controversialwhen they were written and in 1999 they were again used

as political resources that the Diggers350 drew upon to

inform and legitimate their own actions. Additionally

their heritage credentials lent a further veneer of ac-

ceptability to their deployment and the associated ac-

tions during April 1999. The action is described below.

4.2. St. George’s Hill as George Hill

St. George�s Hill was occupied on April 3rd byaround 350 marchers bearing a carved stone memorial

(Fig. 1), 9 various banners and other carnival-style

paraphernalia (Lodge, 1999; Bebbington, 1999; TLIO,

1999). The group had assembled at nearby Walton and

had walked in procession to the Hill. In the months

prior to the action the procession and existence of the

Stone had been publicised widely by TLIO (1998, 1999).

On reaching the summit of the Hill (now a golfcoursefairway) the crowd gathered around the memorial stone

and for a short period readings of Winstanley�s workswere performed by various individuals. 10 Then some of

the crowd moved to a pre-planned 11 location to install

the memorial stone and begin an occupation of that part

of the Hill. The occupation site, 12 owned by the local

water company, was occupied for 12 days by a band of

people forming Diggers350 (see TLIO, 1999; SurreyHerald, 1999; Walton and Weybridge Informer, 1999).

This small group of �Diggers� stayed on site until theywere evicted. This generated favourable media coverage

in the local and national press. The water company, as

eponymous 1975 film directed by Kevin Brownlow. Songs dating from

the period were sung along with more recent Diggers related songs. It

may be observed that such enrolment/role-play added yet another layer

of mediation and performance to the event.11 The inner circle of Diggers350 had planned this part of the action

well in advance.12 The area used was a small wooded site amongst large houses on

the St. George�s Estate owned by the North West Surrey WaterCompany.

Fig. 1. The Winstanley Stone installed on St. George�s Hill, Surrey,December 2000. The inscription reads ‘Worke Together, Eate Bread

Together. Gerrard Winstanley––A True Leveller 1649’. The engraved

vegetables represent the peas, carrots and parsnips that Winstanley

mentions in his accounts of the commune.

13 This is particularly pertinent as Diggers350 were convinced that a

public footpath across the Hill had been obscured from the records

(i.e. the Definitive Map of public paths).14 A further chapter in the story of the Stone and the memoriali-

sation of the Diggers has since unfolded although it is beyond the

scope of this paper to describe it fully. In short the Stone has since been

found a permanent site on the edge of the Hill. Importantly for the

arguments in this paper the process was enabled partly through a

Local Heritage Initiative grant applied for by the local group (see

Parker, 2002; Surrey Comet, 2000b; Countryside Agency, 2000; Local

Heritage Initiative, 2001).15 A TLIO banner bearing the Winstanley quote referenced above

was among the slogans draped between the lamp posts lining

Parliament Square during Mayday 2000.

402 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

landowner, acted to get the Diggers group evicted from

the site; the subsequent High Court Order was served on

the 16th April and the occupiers moved off the site

peaceably. The main objectives of commemoration and

press coverage were fulfilled and the goodwill of at leastsome local people remained intact (TLIO, 1999; Surrey

Comet, 1999a,b; Surrey Herald, 1999).

The longer-term objective of Diggers350 to install the

Stone permanently on the Hill had not been achieved.

At the time of the eviction the Stone was taken from the

Hill by the Diggers350 and placed in storage at the local

museum. The occupation of the Hill had generated

much interest and courted controversy in the locality(Surrey Comet, 1999a, 2000a; Guardian, 1999a,b).

There was both opposition and support for the senti-

ment of enacting the practice of Digging and the events

were described by some as �living heritage�. The ownersof the golf course site had made it clear that they would

not want the Stone to be left on the Hill permanently. A

view echoed by the very local St. George�s Hill Resi-

dents� Association (Walton and Weybridge Informer,1999). They claimed that people would �trespass� 13 inorder to view the Stone. Other local people expressed

support for the memorialisation seeing the significanceand heritage �value� of Winstanley and the Diggers (seeSurrey Comet, 2000b). Over the following days and

weeks the objective of permanently memorialising the

Diggers on the Hill was supported by a significant

portion of the local population. A claim legitimised by

the establishment, not long afterwards, of a local group

with the primary purpose of finding a permanent home

for the Stone. 14

This example involves explicit mobilisation of his-

torical actions and spaces and their recreation, as well as

performing past practice through theatrical display leg-

itimated through the portrayal of local (and national/

global) �heritage�. This potentially radicalises heritage(while perhaps heritagising radicals) and, in this exam-

ple, challenges dominant views of land use and claims on

ownership. The Stone and other artefacts became rep-resentations and powerful in their own right. The per-

formance of stone-placing and Digging constructed a

tableau of theatrical representation in performance;

moreover this was embodied political practice and

statement of a counter-heritage.

The Diggers350 action can also be seen as an attempt

to refigure the identity of the space for the twelve days

and perhaps since then the imagination and under-standing of St. George�s Hill/George Hill has altered forthose at the action and for those reading about it.

Further radical usage of the Diggers as ideological

messenger (Hollinshead, 1997) illustrates how the St.

George�s Hill action has not neutralised the Diggers.The Diggers350 events instead played a part in protest

actions the following year, similar practices of �Digging�became central to the symbolism employed by anti-capitalist demonstrators at the Mayday 2000 rally in

central London and elsewhere around the UK (see

Chesters, 2000b). 15 In fact a few of the Diggers350

group had been informally involved in the planning

stages of parts of the Mayday demonstrations. In that

instance symbolically digging up the turf of Parliament

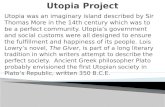

Fig. 2. (a) The WWII �Dig On� image by Peter Fraser. (b) The 1990s�Dig In� image produced by Trystan Mitchell.

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 403

Square, London, relaying it on the road and planting

seeds and plants signified resistance to unchecked �cap-italist development� (Guardian, 2000; see also Fig. 2babove). This was Digging on the very doorstep of power.

In this sense to �Dig� became a practice whose semioticswas one of a powerful act of resistance made distinctivein time–space and through a particular ownership. This

motif is invoked in a political refiguring of a very

different history, performed in everyday practice and

represented in political mobilisation. Thus the micro-

politics of the example can be seen as one that has sig-

nificance on numerous levels. It involved a perfor-

mance and a �doing of space� by the participants of theDiggers350 events. It provided the material for an am-plification of the Diggers to a wider audience of �par-ticipants� through the print media and it strengthened aconnection with local people who have become more

interested in �the Diggers� and their message.

4.3. ‘Dig in for history’: a politics of doing

This example relates to the wider heritage, politics

and practice of allotments (see; for example, Crouch and

Ward, 1997; Crouch, 1999). The narrative relates to

digging as a mundane part of what allotment holding

means. In a recent poster used to campaign for allot-

ments in Britain by TLIO the icon depicts an allotmentholder digging up tarmac to create crops in a perfor-

mance of power. The image in question very noticeably

focuses on the act of digging and the spade held by the

digger. Significantly the image is accompanied by the

banner words �Dig in for Victory�. The original poster(Fig. 2a) was created by Peter Fraser and adorned public

spaces around the UK during the Second World War.

The later image (Fig. 2b) was designed by TrystanMitchell and has been extensively by TLIO (1998, 2000).

Allotment politics have a long history that includes the

post-English Civil War Diggers, as discussed above, and

subsequent land movements to secure places to grow

food after the alienation of common ground during the

Enclosures (see Hill, 1996; Hall and Ward, 1998;

Douglas, 1976). Through the nineteenth century the

plight of rural labour combined with struggles to secureland to grow food amidst the onset of extensive urban

industrialisation (Crouch and Ward, 1997). Allotments

were the subject of more top-down politicisation during

the 1960s when a Government Inquiry (the Thorpe

(1969) Report) presumed consensus and sought to ra-

tionalise, organise, tidy and bring order to allotment

land and its use, recommendations typified by (failed)

appeals to impose uniform design on allotment sites (seeCrouch, 2002).

Politics on allotments take three forms. One is the

often-staged politics of contesting proposals to build on

them. This politics can involve the plotters in political

organisation, working out schemes of action in order to

debate, to protest, to publicise their case. A more ev-

eryday politics is the more diffuse practice of negotia-

tion; negotiating with other plotholders on issues ofwhat to do with communal areas of sites, over contested

issues of growing plants and using the ground. These

concerns can reveal deep tensions between, for example,

ways of growing things that may be felt to have an in-

fluence beyond the individual plot e.g. the blowing of

pesticide sprays or, organically tended �weeds� blowingseeds onto neighbouring plots.

16 This is resonant of �plotlands� landscapes of the early 20th century(see Hall and Ward, 1998) and contemporary low impact settlements

proposed by authors such as Fairlie (1996). In both forms, where

individuals build their own homes on their own small parcel of land.

404 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

Allotments began to attract the curiosity of the eco-

logically politically active in the 1970s. Traditional

plotholders, who identified more with the work allot-

ments required than with a broader politics that is im-plicit in an environmental campaign, were joined on the

plots by more ideologically committed plotholders.

These shifts intensified during the last decade and set the

scene for current contestation. Throughout these de-

cades local allotment movements often became fiercely

active and articulate in defending and promoting their

perspective and their rights, still in law, to be able to

cultivate a piece of land. In order to promote this, theyhave rediscovered a piece of official, institutional history

and remade it in their ideology. This brings together the

two dimensions of history that are the concern of this

paper. History can be refigured as a very different poli-

tics. That history is identified also through an appar-

ently simple, everyday micro-politics of working land in

the exploration of the self, expressively engaging the

material world. This may be informed by the encounterthat results from that practice; reworking that encounter

into a development of ideology that has brought in-

creasing mutual recognition between those habitually

politicised and those who �merely� wanted to cultivatethe ground.

Furthermore there is a more intimate politics of ne-

gotiation with oneself, developing ideas and attitudes to

using land and developing values about non-commodityvalues, forms of human relationships, love and care

(Gorz, 1984) and actions and ways of doing things.

Since many plotholders have little desire towards poli-

tics they frequently explore their own agency through

these apparently softer, but possibly no less significant

practices. Everyday practice requires physical, bodily

encounter that can rupture a learnt way of �makingsense� because it uses non-linguistic encounter, feelings,emotions, and provides conduits through which our

desires can be expressed, through our encounter with

space and other subjects. Here it is possible for indi-

viduals alone and inter-subjectively to refigure identity

and how the world makes sense, to take direct action in

terms of the environment and to negotiate aspects of the

world through their own action. Many allotment hold-

ers do not start with a distinctive politics nor work a plotto pursue an ideology, yet many discover values about

land through what they do (Crouch and Ward, 2002).

As Oakes (1997) argues �. . .it is the deeper realisation ofone�s contradictory subjectivity that informs action

more than a priori political consciousness�. Carol(quoted in Crouch and Ward, 2002) expresses this per-

formatively:

Working outdoors feels much better for you some-

how. . . more vigorous than day-to-day housework,much more variety and stimulus. The air is always

different and alerts the skin. . . Unexpected scents

are brought by breezes. Only when on your hands

and knees do you notice insects and other small

wonders. My allotment is a central part of my life.

I feel strongly that everyone should have some ac-cess to land, to establish a close relationship with

the earth, something increasingly missing in our so-

ciety, but essential as our surroundings become

more artificial.

In �doing� her allotment her ideas develop and valuesare grasped through performance or embodied prac-

tice, thus constituting her ontological knowledge. Her

knowledge are opened up through what she does and the

�feeling of doing� it engenders in her. Each time she doesthis it is the performing that reasserts her beliefs and

enlivens them, moves her on, in a process of becoming.

4.4. Representing digging

During the Second World War the British Govern-

ment encouraged people to dig. In the First World War

era allotments signified the fight for food amidst exter-

nal difficulties and containment (see Douglas, 1976). As

mentioned, in the early 1940s the Government used a

close-up photograph of a boot being pushed against a

spade into the earth, exertive and proud (see Fig. 2a).

This icon and its meaning are significantly reworked inthe new image in �Dig in for Victory� (Fig. 2b). Thedepicted digger (sic) is young, androgynous, resonant of

a new generation of more overtly politically active

plotholders. Practice is represented in the image to be

digging up tarmac, an icon of capitalist and non-

ecological development of the land. The foreground is

planted with crops that lead off to a background of

windmills and a teepee. 16 One representation is refig-ured into another, but threads of the prior representa-

tion remain: the significance of land, the empowerment

of its practice.

The new �fight� is for land that this image represents,although here exaggerated by �new age� symbolism, for�ordinary� people to use. The image asserts the signifi-cance of political ideology and attitude. The political

importance and depth of feeling associated with land asheritage and the right to grow food remains. Whilst the

representation of gardener, spade and earth character-

ised consensual national identity in the original poster,

in this reworking this combination represents internal

conflict. Although the new poster is used by a more

overtly �political� campaign organisation, it mirrors theexpressed feeling of a much wider population involved

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 405

with allotments today. Many of these people are not

habitually or ideologically inclined to a formal politics.

However, through their discovery of the significance of

working with land, of being empowered through aphysical practice, discovering non-commodity values

and relations, have constituted their own politics and

ideology and identified with the more overtly political

side of the movement. It is this politics that underlies

the TLIO/Diggers350 action on St. George�s Hill. TheDiggers350 used heritage and created artefacts (e.g. the

memorial stone) to amplify and legitimise a land occu-

pation that was designed to �show-off� Digging and raiseconsciousness about broader land-related/environmen-

tal issues to a wider public.

5. Refiguring heritage in new political mobilisations

The appropriation of historical action, texts, arte-

facts, the media and place may be read as discursive

practices aimed towards or embodying preferred fu-

tures. Here they are cast as the performance of counter-

memory (Hartsock, 1987). Mandelbaum (1991) sees

such an approach as one (while involving the presenta-

tion of alternative histories) that is part of a morecommon strategy whereby discourses and alternative

�voices� are competitively mobilised as part of �persuasivestorytelling about the future� (see also Throgmorton,1992). In the second example there is an emphasis on the

performance of heritage and of the appropriation of

heritage through performance, as well as the refiguring

of representations. Moreover the second cameo expli-

cates embodied practice or performance that may bemade in an apparently mundane doing, and as a route to

ideas of ownership––lay constitutions of citizenship and

ideology in a performance of practical ontology. In both

examples we argue that heritage was drawn into and

associated to the actions and the artefacts as a legiti-

mising discourse. It is used to soften and appeal to au-

diences that view heritage as benign or somnambulant

and who might be open to learning something aboutthemselves by examining the past. In this sense it is a

method of preparing another�s counter-memory so thatit is imbued with a form of cultural capital. Thus the

TLIO approach invites politicisation through both ac-

tually doing, and also through the mediation of that

doing to a wider audience. In each example practice and

representations are mutually engaged and produced.

Popular imaginings are more and more weigheddown and yet supplied by the past and by the burden of

recorded and refigured history. We think that history is

used as a method of attempting to delineate the pre-

ferred future and that, after Benjamin; by brushing

against the grain alternative, perhaps radical, futures are

groomed (as well as dominant histories and identities

being otherwise protected). Such a process of imagi-

neering the future using the past to contest politics of the

present involves the representation of place and prac-

tices as multiple time–spaces; the St. George�s Hill, asgated community becomes (again) George Hill, the com-mune. The presentation of pasts which destabilise the

present therefore aim to influence and disturb power

relations through the representation of history. Another

typical example might involve a local group drawing on

recovered �heritage� to resist the plans for a development(cf. Throgmorton, 1992; Parker and Wragg, 1999). Re-

sultant negotiations may lead to compromise, conflict or

both and may provide further knowledge upon which tobase further contestations.

Engaging theory on performance presents everyday

history-as-knowledge as a basis for politics and micro-

politics, freeing analysis from the limits of official and

received histories and overt or institutional politics. No

longer can we adequately grasp versions of heritage

adequately in texts alone, but also in performance. This

has been discerned by at least some groups who performtheir politics. Even radical �revolutionary� heritage canmake for digestible and persuasive political storytelling.

The struggle to control history is in the present through

everyday mediated practice. Actions engaged in may

enable a relearning of skills that dominant power rela-

tions (and readings of history) have otherwise margi-

nalized or (exclusively) commodified. This enriches the

possibility of inter-subjective history learnt and workedthrough local projects and incidental events. Here they

are happenings focused and mobilised through the re-

figuring of old representations (Crang, 1996, 1998; Local

Heritage Initiative, 2001). Thus heritage and �doing�maybe both political statement and learning process. At

other times and in other contexts perhaps neither out-

come (qua position taking or policy change) will obvi-

ously result.It appears however, that knowledges and skills

transmitted through practice may be important forms of

learning and can challenge other modes of being and

doing and their outcomes. Thus a politics of mediation

is a politics about the learning and relearning of practice

and wider behaviours. Heritage becomes a contempo-

rary process of ownership and practice where authen-

ticity is refigured (see Crouch, 1999). The discourse ofheritage can provide a legitimating and a normalising

discourse for alternative ways of being and doing: en-

gaging with nature and society and challenging domi-

nant modes of practice. Within this proposition the

examples above have implicated a range of artefacts in

the performances discussed; landscape, tools, crops and

plants are crucial objects in the mediation of the

counter-memory.�Digging-up� history can therefore be read as a refig-

uring of identities. This refiguring is a reflexive process,

engaging mental reflexivity (Crouch and Matless, 1996)

and relates to more recent work on practice, embodied

406 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

semiotics and on active citizenship (Crouch, 2003; Par-

ker, 2002; Matless, 1998). It also implies that represen-

tation and representing overlap and that embodied

semiotics are processual. There are at least two mainlessons here. First that people use and appropriate,

contest and challenge authority using a complex range

of resources and use increasingly complex and subtle

networks. The second is that ebbs and flows of politics

and practice are the very stuff of culture and therefore of

a diffuse politics. Redoing or consciously reenacting can

be but a step away from doing. Both can provide in-

spiration and an embodiment of cultural, social andpolitical values and a �making sense�. They also indicatethat visual iconography can be transformed into aids for

a different micro-political agency. This interpretation

presents new grounds through which to consider the

everyday use of one political iconography in favour of

another, of one representation of citizenship to a con-

temporary, dynamic present. Representations can be

embodied and signified in performance and this per-formance can constitute new resources and versions of

representation.

The notion of embodied and performed space, lay

geographies and �making sense�, alongside representa-tions, can inform broader conceptualisations of citizen-

ship (Thrift, 1996; McKian, 1995; De Certeau, 1992;

Shotter, 1993). We contend that on some level all action

is in some sense �political� in, for example, that agencycan both challenge and legitimate institutional struc-

tures and outcomes. Further, mediated politics can en-

courage certain practices to be appropriated for more

overt political use (and in other contexts for commercial

purposes e.g. the tourism and advertising industries). In

this paper one aspect of such political action has been

focused and situated, indeed choreographed, in cultural

and geographical theory.The insights discussed prompt a wider avenue for

research to understand how exhortations and examples

of practice are performed for political amplification or

how practice influences or activates the political con-

sciousness of the agent. In consequence, attention in

politics and in heritage studies to the way things are

done and claims are made, is necessary in order to fol-

low through on issues and projects that challengedominant positions; to see how they are received, in-

corporated, refigured, resisted and mobilised vis-�aa-visdominant positions. In addition this requires attention

to �work done� in micro-political practice and discourseas well as dominant politics in repositioning and refig-

uring processes. This �going further� appears as a �goingback�. To many perhaps a seductive, comforting play onthe appeal of heritagised counter-memory.The process of association and formulation of coali-

tions using history as a resource can, perhaps, destabilise

the popular grasp of what heritage may be, and involve

a range of tactics, ploys and arguments. Actors have

pulled in resources (e.g. artefacts, places and texts) in

constructing and legitimating a �heritage discourse� thatlegitimises, but may possibly obscure, a more radical

intent, or a more radical implication. The Diggers bringa narrative to bear that speaks to the present, but which

presents the counter-memory as a persuasive storytelling

or performance about the future. The predictability of

the re-presentation of selective heritage that people also

�live� themselves in their own practices is deserving ofinvestigation. This attention to everyday practices and

their potential for refiguring space includes the popular

use of textual resources and their repositories such aslibraries or the Internet (as Crang, 1996 has explored

with regard to local history workshops), as well as the

media and elite representations of heritage and their

contestation. We feel that the process of unravelling

history and assumed truths, and also the notion of �be-coming citizen� may be better understood through thisapproach.

In the light of this we highlight the need to deepenunderstandings of both memory and counter-memory.

The partiality and selectivity of memory and counter-

memory as used here may be better expressed for our

work in terms of �encountered memory�. Furthermorethis suggests considerable space for further evaluation of

�doing� through a close investigation of contents andprocesses across a plurality of practices/claims/authen-

ticities; investigating the claims and processes of power,ownership, and elites; and how empowerment, claims

and identities are being constructed and contested.

There is, for example, strong evidence that allotment

holders are becoming more radical in their land claims

(Crouch, 1999; Wiltshire et al., 2000). They are more

informed and intuitive in negotiating claims with sur-

rounding regulators. Local people living near to St.

George�s Hill or others visiting the memorial stone(virtually or otherwise) that features in this paper may

carry away or further explore the ideas of the Diggers,

or perhaps question dominant assumptions about spaces

and practices. In a more dissipated way the action of

digging for those, may trigger memory or significance

beyond the mundane. As argued here the degree to

which �staged� and otherwise embodied performancesand their amplification penetrate everyday discourse,lives, practices and reflexivities amongst a wider popu-

lation, and the processes of flow, trajectory and multiple

impacts and intimations of history deserve to be further

investigated.

References

Adam, B., 1995. Time Watch. The Social Analysis of Time. Polity,

Cambridge.

Anderson, A., 1997. Media, Culture and the Environment. UCL Press,

London.

D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408 407

Barnett, C., 1999. Deconstructing Context: exposing Derrida. Trans-

actions of the IBG NS 24 (3), 277–294.

Bauman, Z., 1998. Globalisation. Its Human Consequences. Polity,

Cambridge.

Bebbington, S., 1999. Diggers March Squats Des Res Land. TLIO

Press.

Beck, U., 1998. Politics of risk society. In: Franklin, J. (Ed.), The

Politics of Risk Society. Polity, Cambridge.

Becker, K., 2000. Picturing a field: relationships between visual culture

and photographic practice. In: Anttonen, P. (Ed.), Folklore,

Heritage Politics and Ethnic Diversity. Multicultural Centre,

Botkyrka, Sweden, pp. 100–121.

Bender, B., 1993. Stonehenge––contested landscapes (medieval to

present-day). In: Bender, B. (Ed.), Landscape: Politics and

Perspectives. Berg, Providence, RI.

Bey, H., 1991. The Temporary Autonomous Zone and Ontological

Security. Autonomedia, New York.

Boulton, D., 1999. Gerrard Winstanley and the Republic of Heaven.

In: Dales Monographs. Dent, Cumbria.

Bradstock, A., 1997. Faith in the Revolution. SPCK, London.

Bradstock, A. (Ed.), 2000. Winstanley and the Diggers 1649–1999.

Frank Cass, London.

Bromley, D., 1998. Rousseau�s revenge: the demise of the freeholdestate. In: Jacobs, H. (Ed.), Who Owns America? University of

Wisconsin Press, Madison.

Chesters, G., 2000a. The new intemperance: protest, imagination and

carnival. Ecos 21 (1), 2–9.

Chesters, G., 2000b. Guerrilla Gardening––the end of the world as we

know it. Ecos 21 (1), 10–13.

Countryside Agency, 2000. Scheme Puts Heritage in the Hands of

Locals. Countryside Focus, Issue No. 6 Feb./March 2000. Coun-

tryside Agency, Cheltenham.

Crang, M., 1996. Envisioning urban histories: Bristol as palimpsest,

postcards and snapshots. Environment & Planning �A� 28 (3), 429–452.

Crang, M., 1998. Cultural Geography. Routledge, London.

Crang, M., 2001. Rythmns of the City: temporalised space and motion.

In: May, J., Thrift, N. (Eds.), Time/Space: Geographies of

Temporality. Routledge, London.

Crossley, N., 1995. Merleau-Ponty, the elusive body and carnal

sociology. Body and Society 1, 43–62.

Crouch, D., 1999. The intimacy and expansion of space. In: Crouch,

D. (Ed.), Leisure/Tourism Geographies. Routledge, London.

Crouch, D., 2000. Places around us: embodied lay geographies in

leisure and tourism. Leisure Studies 19, 63–77.

Crouch, D., 2001. Spatiality and the feeling of doing. Social and

Cultural Geography 2 (1), 61–75.

Crouch, D., 2002. The Art of Allotments. Five Leaves Press,

Nottingham.

Crouch, D., 2003. Ecology, performance and practice: stretching

ground subjectivities: lay Geographies and the performance of

nature. In: Szerszynski, B., Wallace Heim, H., Waterton, C. (Eds.),

Nature Performed: Environment, Culture and Performance. Black-

well/Sociological Review, Oxford, in press.

Crouch, D., Matless, D., 1996. Refiguring geography: the parish maps

of common ground. Transactions of the Institute of British

Geographers NS 21 (1), 236–255.

Crouch, D., Ward, C., 1997. The Allotment: its Landscape and

Culture. Five Leaves Press, Nottingham.

Crouch, D., Ward, C., 2002. The Allotment: its Landscape and

Culture, second ed. Five Leaves Press, Nottingham.

De Certeau, M., 1992. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of

California Press, Berkeley.

Dewesbury, J.-D., 2000. Performativity and the event. Environment

and Planning D: Society and Space 18, 473–496.

Domosh, M., 1998. Those gorgeous incongratuities. Annals of the

American Association of Geographers 88 (2), 209–226.

Douglas, R., 1976. Land, People and Politics. Allison & Busby,

London.

Etzioni, A., 1995. The spirit of community. Fontana Press, London.

Fairlie, S., 1996. Low Impact Development. Jon Carpenter, Charlbury,

Oxon.

Foucault, M., 1977. Language, Counter-memory, Practice. Selected

essays and interviews. Blackwell, Oxford.

Friedman, J., 1994. Cultural Identity and Global Process. Sage,

London.

Game, A., 1991. Undoing the Social. OUP, Buckingham.

Giddens, A., 1984. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Material-

ism. Polity, Cambridge.

Goffman, E., 1967. Interaction Ritual. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Gorz, A., 1984. Ecology as Politics. Pluto, London.

Gramsci, A., 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Lawrence &

Wishart, London.

Grant, J., 1994. On some uses of planning �theory�. Town PlanningReview 65 (1), 59–76.

Grosz, E., 1999. Thinking the new: of futures yet unthought. In: Grosz,

E. (Ed.), Becomings: Explorations in Time, Memory and Futures.

Cornel University Press, Ithaca, NY.

The Guardian, 1999a. 350 years on, Diggers try to reclaim fairways as

common treasury for all. The Guardian, 5th April 1999, p. 12.

The Guardian, 1999b. Levels of Optimism. The Guardian––Society,

24th March 1999, p. 2.

The Guardian, 2000. Protests Erupt in Violence. The Guardian, 2nd

May 2000, p. 1.

Halfacree, K., 1999. Anarchy doesn�t work unless you think about it:intellectual interpretation and DIY culture. Area 31 (3), 209–220.

Hall, P., Ward, C., 1998. Sociable Cities. Wiley, London.

Hannigan, J., 1995. Environmental Sociology. Routledge, London.

Hartsock, D., 1987. Remaking modernism: minority versus majority

theories. Cultural Critique 7, 141–170.

Hill, C., 1996. Liberty Against the Law. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Hollinshead, K., 1997. Heritage tourism under post-modernity: truth

and the past. In: Ryan, C. (Ed.), The Tourist Experience. Cassell,

London.

Ingold, T., 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on

Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, London.

Jeffries, J., 2000. Land for Life and Livelihoods––a Campaign for

Land Rights. Ecos 21 (1), 45–48.

Joseph, M., 1999. Nomadic Identities: The Performance of Citizen-

ship. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Laclau, E., 1990. New Reflections on Modernity. Polity, Cambridge.

Latour, B., 1999. On recalling ANT. In: Law, J., Hassard, M. (Eds.),

Actor Network Theory and After. Blackwell, Oxford.

Le Corbusier, 1937. When the Cathedrals were White. Pantheon,

London.

Local Heritage Initiative, 2001. Website located at <http://www.lhi.

org.uk/>.

Lodge, A., 1999. An Account of Things (posted on the Diggers350

egroup discussion list 8th April, 1999). Archived via the TLIO

website at <www.oneworld.org/tlio>.

Lowenthal, D., 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. CUP, Cam-

bridge.

Lowenthal, D., 1994. Archaeologists and others. In: Gathercole, P.,

Lowenthal, D. (Eds.), The Politics of the Past, second ed.

Routledge, London.

Mandelbaum, S., 1991. Telling stories. Journal of Planning Education

and Research 10, 209–214.

Matless, D., 1998. Landscape and Englishness. Reaktion, London.

McKay, G. (Ed.), 1998. DIY Culture. Verso, London.

McKian, S., 1995. That great dust-heap called history: recovering the

multiple spaces of citizenship. Political Geography 14 (2), 209–216.

Monbiot, G., 1998. Reclaim the fields and country lanes. The Land Is

Ours Campaign. In: McKay, G. (Ed.), DIY Culture. Verso,

London, pp. 174–186.

408 D. Crouch, G. Parker / Geoforum 34 (2003) 395–408

Nash, C., 2000. Performativity in practice: some recent work in

cultural geography. Progress in Human Geography 24 (4), 653–

664.

Nowotny, H., 1994. Time. The Modern and Postmodern Experience.

Polity, Cambridge.

Oakes, T., 1997. Place and the paradox of modernity. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers 87 (3), 509–531.

Parker, G., 1999a. Rights, symbolic violence and the micropolitics of

the rural. A case study of the parish paths partnership scheme.

Environment and Planning �A� 31, 1207–1222.Parker, G., 1999b. The role of the consumer-citizen in environmental

protest in the 1990s. Space & Polity 3 (1), 67–83.

Parker, G., 2002. Citizenships, Contingency and the Countryside.

Routledge, London.

Parker, G., Wragg, A., 1999. Networks, agency and (de)stabili-

sation. The issue of navigation on the River Wye. Journal

of Environmental Planning and Management 42 (2), 471–

487.

Petegorsky, D., 1995. Left Wing Democracy in the English Civil War.

Alan Sutton, London.

Philo, C., Wilbert, C. (Eds.), 2000. Animal Spaces, Beastly Places.

Routledge, London.

Pred, A., 1984. Place as historically contingent process: structuration

and the time-geography of becoming places. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers 74 (2), 279–297.

Radley, A., 1990. Artefacts, memory and a sense of the past. In:

Middleton, D., Edwards, D. (Eds.), Collective Remembering. Sage,

London.

Ravenscroft, N., 1999. The created environment of heritage as leisure.

International Journal of Heritage Studies 5 (2), 68–74.

Routledge, P., 1997. The imagineering of resistance: Pollok Free State

and the practice of postmodern politics. Transactions of the IBG

NS 22, 359–376.

Sabine, G., 1973. The Works of Gerrard Winstanley. Russell &

Russell, London.

Samuel, R., 1994. Past and Present in Contemporary Culture. In:

Theatres of Memory, vol. 1. Verso, London.

Shotter, J., 1993. Cultural Politics of Everyday Life. OUP, Milton

Keynes.

Surrey Herald, 1999. �Victorious� Diggers March Off. Surrey Herald,22nd April 1999, p. 3.

Surrey Comet, 1999a. New Levellers Set up at St. George�s. SurreyComet, 5th April 1999, p. 7.

Surrey Comet, 1999b. � Diggers� Beat the Bailiffs. Surrey Comet, 16thApril 1999, p. 1.