Queen of the Chinese Colony Gender Nation and Belonging in Diaspora

Diaspora, Nation, And the Failure of Home Two Contemporary Indian Plays

-

Upload

raghavendra-h-k -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

1

Transcript of Diaspora, Nation, And the Failure of Home Two Contemporary Indian Plays

Diaspora, Nation, and the Failure of Home: Two Contemporary Indian PlaysAuthor(s): Aparna DharwadkerReviewed work(s):Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, Theatre, Diaspora, and the Politics of Home (Mar.,1998), pp. 71-94Published by: The Johns Hopkins University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068484 .Accessed: 09/11/2011 03:29

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toTheatre Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

Diaspora, Nation, and the Failure of Home: Two Contemporary Indian Plays

Aparna Dharwadker

Locating the Indian Theatre of Diaspora

We may speak metaphorically of the "drama of the diasporic" in the writing of

displaced Indian authors, but in a literal sense the genres of drama and theatre are

nearly absent from it. This is increasingly evident in the bibliographical and critical

work that has begun to chart the field of diaspora literature. In his editor's preface to

Writers of the Indian Diaspora: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook (1993), Emmanuel

S. Nelson lists fiction, poetry, formal essay, travelogue, biography, and autobiography as the forms in which "the artists included in the study express themselves," excluding theatre altogether.1 Among the fifty-eight "representative" figures profiled in Nelson's

sourcebook, only two Indo-British authors?Hanif Kureishi and Farrukh Dhondy? have produced a recognizable body of plays for stage, radio, and television. Both,

however, are better known for their work in other genres, and neither can be strongly associated with a "theatre of diaspora."2 In North America, anthologists and critics

Aparna Dharwadker is Assistant Professor of Drama and eighteenth-century studies at the University of Oklahoma. She has contributed essays on early modern and postcolonial theatre to such journals as

PMLA, Modern Drama, New Theatre Quarterly, Studies in English Literature, and Studies in

Philology. With fellowship support from the NEH and the American Institute of Indian Studies, she is now

completing a book on

postcolonial Indian theatre.

An earlier version of this essay was presented in December 1996 at the panel on Diaspora and

Theater arranged by the MLA Division on Drama, MLA Annual Convention, Washington, D.C. I want

to thank Joseph Roach for reading the paper in my absence, and Daniel Cottom for his comments on

that version. To Vinay Dharwadker I am grateful for dependable criticism, help with the translations

from Marathi, and that special patience which comes with sharing a home.

Emmanuel S. Nelson, preface to Writers of the Indian Diaspora: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical

Sourcebook (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1993), xii. 2 Farrukh Dhondy began writing plays for the stage and television in 1979, after having published

two successful collections of short fiction. His play "Romance, Romance," produced on BBC in 1983, won the Samuel Beckett Award, but Dhondy has received greater critical acclaim for two novels, Poona

Company (1980), and Bombay Duck (1990). Hanif Kureishi began writing plays around 1976, and became writer in residence at the Royal Court Theatre in 1981. The Mother Country, produced by the Riverside

Studio Company, won the Thames Television Playwright Award for 1980, and Outskirts won the

George Devine Award for 1981. However, the Oscar-nominated screenplay for My Beautiful Laundrette,

Stephen Frears's 1985 film about immigrant Pakistani life in England, is regarded as Kureishi's first

"major" work. His move away from the theatre is signalled by a second screenplay, for the film Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987), and the publication of a first novel, The Buddha of Suburbia (1990). See Nelson,

Writers of the Indian Diaspora, 107-13 and 159-68 for a fuller discussion of these authors' work in the

theatre.

Theatre Journal 50 (1998) 71-94 ? 1998 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

72 / Aparna Dharwadker

have approached immigrant theatre through such categories as multiculturalism,

ethnicity, diversity, and color, and in the resulting descriptions playwrights of Indian

origin are either missing or eclipsed by their Afro-Caribbean, East Asian, and

European counterparts.3 When the focus is exclusively on writers of South Asian

origin in a specific host country, the subordinate position of drama in relation to

poetry, short fiction, and the novel becomes even clearer.4 Jatinder Verma's London

based Asian performance group, Tara Arts, and his directing work at the Royal National Theatre may well be the best examples of sustained work in the theatre by an

immigrant Indian practitioner, though ironically Verma emigrated to England not

from India but from the embattled Indian diaspora in East Africa.

Given the large scale of Indian emigration to Britain, North America, Australia, and

West Asia since the 1960s, and the success with which authors of the new diaspora have practised the genres of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry in English, the marginality of theatre to diasporic experience suggests a complicated relation between genre,

language, and location. Major contemporary Indian playwrights and theatre directors

have remained unusually resistant to the possibilities of departure, choosing instead to

develop lifelong associations with particular Indian cities, theatre groups, and aca

demic institutions.5 Most of them write and direct plays not originally in English? which "travels" best by virtue of being both an Indian and a Western language?but in one or more indigenous languages that address local, regional, and national rather

3 Women Playwrights of Diversity: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook, ed. Jane T. Peterson and Suzanne

Bennett (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997), discusses one "East Indian" playwright, Sandra Rodgers

(287-89). Rodgers's Indian ancestry, however, goes back three generations to her great-grandfather, a

Scotsman who married an Indian woman while serving in India. The playwright herself lived in

England until 1986, and since then has made her home in California. Canadian Mosaic: Six Plays, ed.

Aviva Ravel (Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1995), includes No Man's Land by Rahul Varma, a first

generation Indian immigrant who is a founding member and artistic director of Teesri Duniya, a

Montreal-based multicultural theatre group, and writes plays in both Hindustani and English. A

collection like Crosswinds: An Anthology of Black Dramatists in the Diaspora, ed. William B. Branch

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), which includes plays by Wole Soyinka, Derek Walcott, Amiri Baraka, and August Wilson, among others, makes the inequalities between the African and

Indian theatres of diaspora starkly clear. 4 The Literature of Canadians of South Asian Origins: An Overview and Preliminary Bibliography, comp.

Suwanda H. G. Sugunasiri (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1987), lists no original

plays in English, one in Gujarati, and nine in Punjabi (five of which were still in progress at the cutoff

date of 1980). A more recent anthology, The Geography of Voice: Canadian Literature of the South Asian

Diaspora, ed. Diane McGifford (Toronto: TSAR, 1992), includes only two short plays: one by Rana Bose, a founding member of the intercultural theatre group Le Groupe Culturel Montreal Serai, and the

other by Rahul Varma and Stephen Orlov. 5 Among the major playwrights, Vijay Tendulkar and P. L. Deshpande are closely associated with

Bombay, Utpal Dutt and Badal Sircar with Calcutta, Mohan Rakesh and Habib Tanvir with Delhi,

Girish Karnad and Chandrashekhar Kambar with Bangalore, and Ratan Thiyam with Manipur.

Among directors, Vijaya Mehta, Alyque Padamsee, and Satyadev Dubey have managed nationally

recognized amateur theatre companies in Bombay, Shyamanand Jalan and Shombhu Mitra in Calcutta, K. N. Panikkar in Trivandrum, Jabbar Patel in Pune, and Om Shivpuri and Rajinder Nath in Delhi.

E. Alkazi has done some of his best directorial work while serving as Director of the National School

of Drama in Delhi (1962-1977). B. V. Karanth, who was Director of the National School of Drama from

1977-1981, and Director of Rang Bhavan in Bhopal from 1982-1986, now runs a state-supported

repertory company in Bangalore.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 73

than international audiences.6 Over the past four decades, their practice has also

followed a nationalist (though not necessarily a pro-nation) agenda, focusing on the

invention of a characteristically "Indian" theatre that assimilates indigenous textual

and performative traditions particular to various regions within the country while

maintaining the qualities of modernity appropriate to a contemporary urban perform ance genre. Conversely, migrant authors appear to have chosen the privacy and

relative self-sufficiency of print genres like fiction, non-fiction, and poetry over the

complications of a collaborative, public, commercial, and performance-based medium

like theatre. Theatre's dependence on institutional networks and validating cultural

contexts may in part explain why leading Indian practitioners have not identified with

the diaspora, and why diaspora authors have only sporadically turned to theatrical

genres. In the Indian case, the fundamentally double-edged experience of migrancy? with the loss and recovery of home as its central figures?may be easier to narrate than

to perform.

However, the features of modern diaspora, mediated further in the case of India by a complex postcolonialism and a contested nationhood, suggest a need for rethinking the relation between diaspora and the postcolonial nation-state, which would also

lead us to reconsider the sites of performance. The dialectic of "longing" and

"belonging" which often defines diasporic relations misrepresents the experience of

diaspora as well as the status of the nation-as-home. Peter van der Veer argues that

"the theme of belonging opposes rootedness to uprootedness, establishment to

marginality. The theme of longing harps on the desire for change and movement, but

relates this to the enigma of arrival, which brings a similar desire to return to what one

has left."7 This formulation assumes that home is a rooted, secure, and established

unity, while departure is the disruptive choice that makes change and movement

possible. But departures no longer uproot as they used to, while the "postcolonial condition," to the extent that the phrase refers reflexively to the situation of the

postcolony, is primarily a condition of accelerated political, economic, social, and

cultural change.

James Clifford comments that "diasporist discourses reflect the sense of being part of an ongoing transnational network that includes the homeland, not as something

simply left behind, but as a place of attachment in a contrapuntal modernity."8 The

nature of this network becomes clearer in John Lie's distinction between miernational

migration, which "entails a radical, and in many cases a singular, break from the old

country to the new nation," and frcmsnational diaspora, "an unending sojourn across

different lands ... [that] better captures the emerging reality of transnational networks

6 Even a national audience becomes available to an Indian-language play only when it is translated

into other Indian languages. On the other hand, the description of English as an "Indian" language no

longer needs elaborate defense. Its central role as the medium of education, business, government, and

journalism in a country of nearly a billion people has been recognized for some time. Since the early

1980s, Anglophone Indian writing has also entered the ranks of the best contemporary writing in

English. As I will show, however, the status of English as a literary medium varies according to genre. 7 Peter van der Veer, 'Introduction: The Diasporic Imagination," in Nation and Migration: The Politics

of Space in South Asian Diaspora, ed. Van der Veer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1995), 4. 8

James Clifford, "Diasporas," Cultural Anthropology 9 (1994): 311.

74 / Aparna Dharwadker

and communities than the language of immigration and assimilation."9 The

postindependence Indian diaspora reflects these qualities, but with a difference. As the

homeland of diaspora, as Nelson notes, India is not a "culturally monolithic entity ...

[but] a staggering compendium of a multitude of ethnicities, languages, and tradi

tions. To speak of an Indian diaspora, then, is to insist on a claim to an essential

psychological and historical unity that undergirds the spectacular Indian mosaic."10

Earlier (nineteenth- and early twentieth-century) Indian migrations to East Asia, the

Fiji islands, Africa, and the Caribbean have also meant that some immigrant groups, like many Jewish communities, have undergone a second diaspora in migrating to the

West. Attempts to construct the new nation unambiguously as "home" in the face of

this diverse history have therefore met with two kinds of criticism: that they "ignor[e] the multiple displacements of many Indians," and that they "fai[l] to grapple with

those, such as Sikhs or Muslims, who, by virtue of India's unmistakable Brahminical

Hindu undergirdings are already outside India, even though they may appear to be

within it."11 At the other extreme is the perception that upwardly mobile Indian

immigrants in affluent locations like Europe and North America?who have already been stereotyped by the label of Non-Resident Indians or NRIs?exercise too much

material and political power to claim an agonistic "diasporic consciousness."

These ironies of the modern Indian diaspora become more acute when we consider

that the conditions of diaspora have appeared in harsher forms within the nation, but

have attracted little attention because they are tangential to the current preoccupation with transnational movements. In postindependence India, the imperatives of "mod

ernization," "progress," "development," and "integration"?necessary to the forma

tion of a modern democratic nation-state?have caused the steady erosion of tradi

tional economies, occupations, customs, beliefs, and practices. In the countryside, new

systems of land ownership, new agricultural technologies, and political mobilization

at the local level have displaced earlier forms of agrarian labor, capital, and political control. In the cities, large-scale industrialization, the emergence of new professional classes and multilayered bureaucracies, and the opening up of domestic markets to

foreign investment have transformed the nature of work, the membership of the work

force, and hence the family. Because of the uncontrolled movements of population

resulting from some of these developments, cities like Bombay and Calcutta have

realized the nightmare stereotype of the third world urban slum. In a different sphere, the ideology of secularism encoded in the constitution, and the move towards

progressive social policies have challenged, though not very successfully, the deeply divisive, hierarchical character of Indian society. Socioeconomic changes have joined

with the effects of cultural heterogeneity and religious division to fragment family and

community life in both urban and rural areas, creating conditions of rootlessness and

marginality that are often more truly disempowering than the pain of voluntary

migration beyond the nation's borders.

9 John Lie, "From International Migration to Transnational Diaspora/' Contemporary Sociology 24

(1995): 304. 10

Emmanuel S. Nelson, introduction to Reworlding: The Literature of the Indian Diaspora (New York:

Greenwood Press, 1992), x. 11

Amarpal K. Dhaliwal, "Reading Diaspora: Self-Representational Practices and the Politics of

Reception/' Socialist Review 24 (1995): 19.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 75

This essay focuses, therefore, on the loss of home at home, as it is represented in two

recent Indian plays, Mahesh Elkunchwar's Marathi Wada Chirebandi (Old Stone

Mansion, 1985), and Cyrus Mistry's English Doongaji House (1978). I argue that the

destruction of home in these plays?both as a material structure (a "house"), and as an

emotional space of ancestral memory, family attachments, and community bonds?is

the unprivileged mirror-image of the nostalgia surrounding the figure of home in

transnational diasporic consciousness. Similarly, Indian-language theatre, which in

cludes plays written originally in English, is the unprivileged converse of the diasporic

production that has become the mainstay of postcolonial theory, and that dominates

the current map of "postcolonial" Indian writing. As social texts, the plays about home

trace the collapse of historically determined, previously dominant but now precarious modes of existence in two radically different locations?a small village in the fertile

Vidarbha region of northeastern Maharashtra in the case of Elkunchwar, and metro

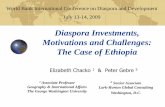

politan Bombay, the capital of Maharashtra, in the case of Mistry (Fig. 1). Written in

two languages with dissimilar histories in the theatre, they also call attention to the

relations between authorship, language, experience, and the cultures of print and

performance in a multilingual national theatrical tradition that has scarcely been

constituted as a critical object, either within or outside India. My analysis seeks to

emphasize that modern diaspora is not necessarily the primary referent in the

experience of dislocation, and diasporic writing (particularly Anglophone fiction) must take its place beside other discourses within the nation that determine and

delineate postcolonial experience.

<

GUJARAT ^~*'% MAVHYA PRADESH

KHANDBSH \

L./'

iV--1

) BOMBAY

!

AURANSABAD

MARATHWADA

?PUNE (POONA)

X

111

)

\GOA

VIDARBHA

I >

r \

" yy*

ANDHRA PRADESH

\a-v

KARNATAKA

Figure 1. Map of Maharashtra, with surrounding states. Map by Vinay Dharwadker.

76 / Aparna Dharwadker

Social Experience, Realism, and the Inequalities of Language

Since the early 1960s, the effort on the part of Indian theatre practitioners to "make

it new" has taken two major forms. One is the use of mythic and historical narratives

to create ironic representations of a supposedly heroic past and allegories of the

present, as in Dharmavir Bharati's Andha Yuga (The Blind Age, 1955), Mohan Rakesh's

Ashadh ka ek Dina (A Day in Ashadh, 1958), and Girish Karnad's Tughlaq (1964).12 The

other is the use of folk and traditional performance genres in an aggressively

experimental theatre which seeks to establish the "contemporary relevance" of these

genres, and to revitalize urban theatre through their hybrid modernity. The aesthetic of

this "theatre of roots" is explicitly anti-realistic (and therefore anti-Western): it rejects the proscenium stage in favor of other, usually open spaces; incorporates indigenous

music and dance styles; relies on stylized movement, gesture, and delivery; and

emphasizes the theatrical use of the body. The nationalist project of this theatre is clear

from the arguments of its main proponent, Suresh Awasthi, who claims that the return

to tradition is part of the "process of decolonization of lifestyle, social institutions, creative forms, and cultural modes"; it has "reversed the colonial course of contempo

rary theatre, putting it back on the track of the great Natyasastra tradition."13 An active

cultural bureaucracy has supported the new theatre for more than thirty years, but its

icons are two plays of the early 1970s: Karnad's Hayavadana (Kannada, 1971) and Vijay Tendulkar's Ghashiram Kotwal (Marathi, 1973).14

In this context of retrospection and experiment, Elkunchwar and Mistry's adherence

to present-day narratives and realist conventions in Wada Chirebandi and Doongaji House is a deliberate gesture of resistance, intimating that non-realist theatre would be

affectively inappropriate for the experience of loss and dispersal they want to

represent. In a playful, self-deprecating account of his dramatic career presented at a

seminar at Pune's Theatre Academy in December 1985 (a form of self-reflection

unusual among Indian playwrights), Elkunchwar undertakes a systematic critique of

the practices of folk-traditional theatre. He "do[es] not feel that there is any need to

take the theatre outside the proscenium," and would prefer to preserve the "conven

tional signs" of the stage, because in his view the spectator's field of vision converts

any given performance space into a proscenium.15 For similar reasons he professes

a

lack of interest in street theatre and environmental theatre, describing bodily contact

between spectators and performers as "an assault on my physical privacy" (93-94). Concern with "Indianness" is dismissed as a form of cultural revivalism, out of place

12 The plays of Bharati and Rakesh, written originally in Hindi, are based respectively on the epic

Mahabharata and the life of the classical Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. Karnad's play, written originally in

Kannada, is about a fourteenth-century Muslim emperor of Delhi. 13

Suresh Awasthi, "'Theatre of Roots': Encounter with Tradition," The Drama Review 33 (1989): 48. 14 Hayavadana uses the Yakshagana folk form of Kamataka to recast a twelfth-century folktale about

a woman who accidentally transposes the heads on the dead bodies of her husband and her lover.

Ghashiram Kotwal uses the traditional Dashavatara form of Maharashtra to create a satiric historical

fable about Nana Phadnavis, the corrupt and powerful nineteenth-century prime minister of the

Peshwa rulers of Pune. 15 Mahesh Elkunchwar, "Majha Aajvarcha Natyapravas" (My Journey in the Theatre Until Now),

Mahesh Elkunchwar, Wada Chirebandi (Pune: Mauj Prakashan, 1987), 93. Elkunchwar's essay appears as a postscript in this original Marathi edition of the play. Subsequent references to the essay and the

play will be included parenthetically in the text. Translations from the Marathi are mine, with

assistance from Vinay Dharwadker.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 77

in a shrinking world that needs a "universal idiom" (92). But Elkunchwar reserves his

strongest criticism for the iconic texts of postindependence Indian theatre, Hayavadana and Ghashiram Kotzval, questioning the attribution of "true experimentalism" and

"authentic Indianness" to plays that in his opinion imposed folk forms artificially on

mythic and historical material.

I personally found the "form" of folk theatre unusable, because what I had to say was so

harsh and stark that I felt it would drown in the festive atmosphere of song, dance, and color in folk drama. Besides, there is always the question of the relevance of folk drama

today. The rural culture that gave birth to this art form is now nearly defunct. If the thread that links village life and folk art is now weak and even broken, how can my urban

sensibility, shaped largely by Western ideas, relate to this art form? ... I also feel no

"nostalgia" for this art form. Maybe it's because I'm from the village. But people in rural

areas have easily accepted the contradictions that arise when old ways disappear and new

ways come in, when the old and the new get mixed up in hodgepodge ways. People in the cities suffer from undue anxiety about these things.

[91-92]

Elkunchwar is careful to separate his form of social realism from protest theatre and

the literature of oppression in general, on the grounds that gestures of solidarity with

the downtrodden would seem shallow and insincere in someone of his privileged

background. But his argument that folk theatre, which is essentially a rural form, is no

longer adequate even for a play of rural life like Wada Chirebandi, indicates his interest

in historicizing the transformation of the village, and relating it to present socioeco

nomic and political contexts. Cyrus Mistry does not reflect on his practice in the same

way and his focus is metropolitan rather than rural, but the verisimilitude of his play is similarly motivated. Furthermore, both playwrights identify closely with their

subjects. Elkunchwar was born into the hierarchical and orthodox brahman wada

(country house) culture he portrays, and feels its inadequacies more acutely because it

failed to provide a home for his own family. Mistry is a Parsi playwright from Bombay

writing about Bombay Parsis, the most distinctive branch of a diasporic community with a complex colonial and postcolonial history in India. As realist plays, Wada

Chirebandi and Doongaji House draw on personal experience, and relate the crisis of

home to the end, during the postcolonial period, of the privileged status that

particular social groups and communities had acquired under colonialism.

Beyond these thematic and formal affinities, however, the textual, performative, and

broadly literary contexts of language as a creative medium in India create radical

differences between these texts. The issue of language is fundamental to the writing and reception of plays in a multilingual tradition where the status of languages as

dramatic media is sharply unequal and paradoxical. Marathi is one of the three most

successful languages of drama and theatre in modern India, the other two being

Bengali and Kannada.16 A modern urban theatre has existed in this language since the

16 Marathi and Bengali are "regional" languages, but as theatrical mediums they have the edge over

Hindi, the majority language in India, because they were the respective dominant languages of the

colonial cities of Bombay and Calcutta, where modem Indian theatre originated. The third colonial city associated with the development of modern drama?Madras?is geographically close to the Kannada

speaking areas of the state of Kamataka (formerly Mysore). Kannada's position of significance as a

theatre-language has also been consolidated in the postindependence period by playwrights like Adya

Rangacharya, Girish Kamad, and Chandrashekhar Kambar, and directors like B. V. Karanth and

Shankar Nag.

78 / Aparna Dharwadker

mid-nineteenth century; it has a complex history of anti-colonial resistance, especially between 1898 and 1910; and it has produced an extraordinary group of playwrights in

the postindependence period, including Vijay Tendulkar, C. T. Khanolkar, P. L.

Deshpande, Satish Alekar, Govind Deshpande, and Mahesh Elkunchwar.17 Bombay has a number of nationally recognized amateur theatre groups (the usual avenues of

performance for serious playwrights), and an active culture of multilingual perform ance. A mature playwright in Marathi has the advantage of being able to define

himself or herself in relation to a long-standing tradition as well as a vital community in the present. In contrast, English-language drama in India continues to be described

as "one of the twin Cinderellas of Indian writing in English," or more unsparingly, as

a lost cause and a form of writing that ought to be dead if it is not already so.18

Although drama in English has been written since the 1870s by Indians, including authors like Michael Madhusudan Dutt and Manmohan Ghose during the colonial

period, its tradition consists mainly of obscure texts for reading, not performance. In

the postindependence period, despite the output of authors like Nissim Ezekiel, Gieve

Patel, Partap Sharma, Asif Currimbhoy, and most recently Mahesh Dattani, English

language drama has not acquired a strong theatrical base or textual currency. Even

major plays remain isolated events, instead of merging into a usable tradition.

The respective careers of Elkunchwar and Mistry, and the reception of Wada

Chirebandi and Doongaji House, illustrate the dissimilar conditions of writing and

performance created by the two languages. Elkunchwar is not a professional play

wright, in the sense that he does not make a living by writing plays, but his body of

work now amounts to a substantial career in the theatre. Since 1970 he has written

nearly a dozen major plays, inviting controversy and criticism for his assaults on

bourgeois morality, ethics, psychology, and social consciousness.19 Concepts like

"performance history," "reception history," "major production," and "critical success"

are highly relative terms in a situation where the recognition of a play as a significant

literary performance vehicle depends on state patronage and high-quality amateur

productions rather than on commercial production and critical evaluation in the

17 For brief accounts of modern and contemporary Marathi theatre, see Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni,

"The Marathi Theatre," Indian Drama, rev. ed. (New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting,

1981), 90-101, and Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni, "Contemporary Marathi Theatre," Studies in Contemporary Indian Drama, ed. Sudhakar Pandey and Freya Taraporewalla (New Delhi: Prestige, 1990), 9-15. For a

discussion of theatrical companies, theatre arts, and performance in Maharashtra (mostly Bombay), see

Farley P. Richmond, "Characteristics of the Modern Theatre," Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance

(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990), 387-462, passim. For an account of British censorship on

the Marathi stage, see Rakesh H. Solomon, "Culture, Imperialism, and Nationalist Resistance:

Performance in Colonial India," Theatre Journal 46 (1994): 323-37. 18 M. K. Naik, "The Achievement of Indian Drama in English," in Perspectives on Indian Drama in

English, ed. M. K. Naik and S. Mukashi-Punekar (Madras: Oxford University Press, 1977), 180. 19

Among the plays by Elkunchwar well-known to theatre audiences in Marathi are Holi (1970),

Sultan (1970), Garbo (1973), Rudravarsha (1974), Vasanakand (1975), Yatanaghar (1977), Party (1981), Raktapushpa (1981), Wada Chirebandi (1985), Pratibimba (1987), and Atmakatha (1988). In its New Indian

Playwrights series, Seagull Books, Calcutta, simultaneously published English translations of five of

these plays in 1989. Party was translated by Ashish Rajadhyaksha; Pratibimba and Raktapushpa were

translated as Reflection and Flower of Blood, respectively, by Shanta Gokhale, and published in a single volume titled Two Plays; Atmakatha was translated as Autobiography by Pratima Kulkarni; and Wada

Chirebandi was translated as Old Stone Mansion by Kamal Sanyal.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 79

Western sense. But within these limitations, Wada Chirebandi has the attributes of a

major work. Between 1985 and 1989, for instance, the play was performed in three

languages and published in two. The original Marathi production by Kalavaibhav in

Bombay (May 1985) was directed by Vijaya Mehta, a leading Marathi stage actress (she

played the role of Aai), and a director of national standing. The same cast recorded a

shorter version of the play in Hindi for Bombay television, under the title Haveli

Buland Thi (The Mansion Was Invincible). The Hindi production of the play at the

National School of Drama, New Delhi (December 1985), was directed by Satyadev

Dubey, another nationally-reputed director based in Bombay. In February 1989, a

Bengali adaptation of the play by Subrata Nandy was staged under Sohag Sen's

direction in Calcutta. The Marathi text of the play was published in 1987 in Pune, and

the English translation in Calcutta in 1989. In the Indian theatrical situation, such rapid circulation confers the kind of "instant canonicity" that signals the arrival of a major new work.

Cyrus Mistry's career as a playwright presents a telling contrast to Elkunchwar's in

every respect. Doongaji House is his only full-length stage play?his other writing consists of fiction, screenplays, and journalism. The play won the Sultan Padamsee

Prize awarded by Bombay's Theatre Group in 1978, but did not achieve production until 1990, appeared in print only in 1991, and has not so far been translated into any other language. In an understated publisher's note to the play, Adil Jussawalla comments that the various reasons for the delay in production, "if brought to light and

scrutinized, would provide an accurate picture of the conditions in which the English

language theatre has functioned during the last fifteen years or so. The obstacles in the

way of getting an original play such as this one performed are many and are often

extremely difficult to overcome."20 With such limited exposure on the stage, the proper context for Mistry's play seems to be not so much drama (in English or any other

language), but the literature of Parsi self-representation that includes the poetry of Keki Daruwalla, Adil Jussawalla, and Kersi Katrak, the fiction of Rohinton Mistry (Cyrus's younger brother) and Bapsi Sidhwa (a Pakistani writer), and the poetry and

drama of Gieve Patel.

However, since English is a major literary language in India, the obstacles Jussawalla mentions seem to have a peculiar application to drama. The theatrical status of English

in India is paradoxical in two ways. As the original language of fiction and poetry it has been increasingly dominant since the 1960s and now commands an international

readership; as the language of performance it remains subordinate to regional languages like Marathi, Bengali, Hindi, and Kannada. In drama, English has so far

proved to be more important as the link language of translation for Indian-language plays, rather than as the language of original composition. The pattern of the last three decades has been that a major play in a language other than English soon acquires a

national, and sometimes an international, audience through translation, especially into

English, but plays written originally in English remain on the periphery of contempo rary Indian theatre and are rarely translated into other languages.

20 Cyrus Mistry, Doongaji House (Bombay: Praxis, 1991), [v]. Subsequent references to the play will be

included parenthetically in the text. The play was first produced by Stage Two at the Alliance

Fran?aise, Bombay, in June 1990.

80 / Aparna Dharwadker

This dual paradox suggests that in Indian writing, the naturalization of English has been effective when the radical of presentation is the printed word, but not when the

radical of presentation is the acted or spoken word.21 In this respect Indian drama and

theatre are very similar to Indian film, television, video, and music. India has the

largest film industry in the world, but virtually no original English-language cinema; one of the largest television audiences in the world, but little original English

language programming besides news, news programs, and documentaries; and a

gigantic popular music industry, but little original English-language music. In all these

categories?theatre, film, television, and music?there is a sizeable urban audience for

Western imports in English, since India is as open as other developing nations to the

imperialist penetration of canonical and popular Western cultural forms. But for the

creation of original performance vehicles for the stage or screen, the preferred media are the

indigenous languages, especially those which have had strong performance traditions

since the pre-colonial period.

The reason for this preference is the idea that a language corresponds to a structure

of experience in the world: theatre has the quality of lived experience when its

language is the "natural" language of the characters it represents. Mimetic representa tion is then mediated only by theatrical convention, not by the additional refractions of

language. As Girish Karnad comments ironically in a 1993 interview, "writing in

English about characters who are presumably speaking in an Indian language for

audiences for whom English is a second language is not a situation conducive to great drama."22 Such "translation" is forced, limiting, alienating. That is why the translation

of a play from one Indian language into another is usually a translation of contexts as

well: Subrata Nandy's Bengali adaptation of Wada Chirebandi is set in rural Bengal, not

Maharashtra. The plays of Mahesh Dattani are perhaps the first to challenge effectively the assumption that Indian drama written in English represents a disjunction between

language and sensibility, material and medium. Dattani does not see his choice of

English as arbitrary, as a "postcolonial" gesture, or as an example of "the empire

writing back"?a phrase which he incidentally describes as "politically incorrect."23

English is simply the language in which "he can best express what he wants to say."24 Dattani's work may signal a new phase in the naturalization of English as a theatre

medium in India, and redress some of the inequalities outlined above. But my analysis of Wada Chirebandi and Doongaji House shows that the expressive qualities of language are a subject in both plays: the characters' sense of being (or not being) "at home" is in

part a function of their own and others' speech.

Death in (and of) the House: The Politics of Caste, Land, and Family

The noun wada literally means "mansion," but in addition to wealth, it connotes

propriety, self-sufficiency, and authority; chirebandi is an adjective which means "solid,

21 Northrop Frye defined the radicals of presentation forty years ago as part of his argument that

"genre is determined by the conditions established between the poet and his public" (Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957], 247).

22 Girish Kamad, "Performance, Meaning, and the Materials of Modem Indian Theatre," interview

with Aparna Dharwadker, New Theatre Quarterly 44 (1995): 365. 23 Mahesh Dattani, Final Solutions and Other Plays (Madras: Manas, 1994), 11.

24 Ibid., 9.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 81

hewn from stone." Relating the play Wada Chirebandi to his family origins in his 1985

address, Mahesh Elkunchwar describes the deteriorating brahman wada as a postcolonial site where an unusable past meets an intolerable present:

The collapse of the wada [as an institution] did not affect us, because all of us left home

early. (Only one of my brothers remained behind by arrangement.) But all around me I watched the other wadas crumbling and people being crushed under them. In the period after independence, I could see very clearly the slow, agonizing death of brahman families,

especially in the villages. This process is not yet over.

[89]

This reaction to home coincides with the geopathology that, according to Una

Chaudhuri, characterizes the problem of place and location in modern realist drama.

Chaudhuri notes that the geopathic imagination in drama articulates the discourse of

home through two main structural and thematic principles: "a victimage of location and a heroism of departure. The former principle defines place as the protagonist's funda

mental problem, leading her or him to a recognition of the need for (if not an actual

enactment of) the latter."25 In Elkunchwar's play the condition of victimage encom

passes four generations of the Deshpande family, which include the ninety-year old

matriarch Dadi, her son Venkatesh ("Tatyaji," whose death is the occasion for the

family gathering), Tatyaji's wife Aai, their children Bhaskar (married to Vahini), Sudhir (married to Anjali), Prabha, and Chandu (both unmarried), and Bhaskar's

teenage children Parag and Ranju. With the exception of Sudhir, who has lived in

Bombay for twenty years, all the other members of the family continue to inhabit the

wada while regarding it as the defining problem in their lives. But just as father-son

relations in the play are anti-oedipal in nature, there is no escape from home through

departure, nor is departure conceived as heroic. Elkunchwar's characters do not

(cannot) make the choice that he did.

Home is both setting and subject in Wada Chirebandi, and its failure is material as

well as ideological. As a structure which provides the Deshpande family with its

physical environment and the theatre audience with a visual frame, the "ancient and

respectable but dilapidated mansion" is the obsessive center of family discourse and a

constant source of anxiety. It is mostly uninhabitable, consumes scarce resources in the

present, and exacts relentless labor, from the women in the family but also from a

feminized male like Chandu, who "toils like a beast of burden" within the house (58).

Throughout the play a number of visual-verbal motifs?the absence of electricity, the

shape of a tractor sunk into the front yard, the rats who seem to have "gnawed holes

into the whole mansion" (50), and the dust that falls unpredictably from the ceiling?

keep the ecology of home in the foreground. As an ideological construct, the wada

embodies the alliance between caste and land which the zamindari system of land

ownership, institutionalized by the British, maintained from the end of the eighteenth

century to the middle of the twentieth. By giving "permanent, heritable, and transfer

able property rights" to zamindars (landowners) who were traditionally high-caste brahmans and kshatriyas, the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 instituted patterns of

caste ascendancy throughout British India which were not challenged seriously until

25 Una Chaudhuri, Staging Place: The Geography of Modern Drama (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995), 15.

82 / Aparna Dharwadker

the postindependence abolition of zamindari by separate legislative acts in the various

states during the 1950s. As landowning brahmans in the Vidarbha region of the 1970s, the Deshpandes have witnessed the dissolution of the colonial partnership between

high ritual status and economic-political power, but are unable to adapt either to the

altered culture of the village or to the new agricultural technologies. Their failure is

displaced onto home as a place of burdensome fixity: as Bhaskar complains to Sudhir, "The times have changed, but the economy of this house has stayed exactly the same"

(44). Although the family is a closed circle (no outsider actually appears in the play), its

conduct is dictated by the village community's presumed memory of "the honor and

prestige of the Deshpandes."

Such a state of entrapment involves the psychosociology of caste as well as the

politics of land, both of which appear in Elkunchwar's play as crucial determinants of

sociocultural and economic identity. The transformation of home into anti-home?a

place of oppression, resentment, and anxiety rather than nurture and support?is

mainly the result of inflexible attitudes to caste within the wada. With patriarchal

legitimation and rather timid matriarchal support, Bhaskar has adopted the position that his claims of ritual purity and supremacy ought to remain unchallenged despite the loss of economic and political power.26 Since the play is set during the thirteen-day

ritual mourning period for Tatyaji, the semiotics of caste is fully in evidence, in the text

but even more so in performance. The death of the father imposes rituals of

purification, penance, and gift-giving that are among the most difficult disciplines of

brahman dharma (law, duty), especially for the eldest son. In both the Kalavaibhav and

the National School of Drama productions of the play (May and December 1985), Bhaskar appeared with the shaved head, clean-shaven face, traditional white cotton

clothes, and ash-smeared forehead that would mark him as the male heir and chief

mourner, making his callow behavior all the more unseemly (Fig. 2). As the visitor

from the city, bearded (in the Kalavaibhav production) and in ordinary Western dress, Sudhir then becomes the natural spokesman against taboo and ritual, especially when

the prospect of ritually feeding the entire village on the thirteenth day of mourning threatens to deprive the family of its last few acres of land. But the lives closest to

Elkunchwar's image of slow strangulation within the wada are those of Prabha and

Chandu, Bhaskar's unmarried middle-aged siblings, who were denied higher educa

tion and modern occupations because such independence would have compromised the family's prestige. The recriminations between Bhaskar and Sudhir rarely rise

above irony because they are driven by selfishness, but Prabha's bitter anger against her male guardians and Chandu's dumb loyalty to the house are tragic.

26 Elkunchwar's treatment of caste in Wada Chirebandi connects remarkably well with recent debates

among sociologists and anthropologists regarding essentialist and instrumentalist approaches to caste.

The essentialist view grounds the ideology of caste in the opposition between purity and impurity, and

the subordination of power to ritual status. The instrumentalist view asserts that in independent democratic India, variables like property status, political power, education, and occupation have

greatly modified the hierarchical relations dictated by caste. See Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchichus:

The Caste System and its Implications, rev. ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); Subrata

Mitra, "Caste, Democracy, and the Politics of Community Formation in India," in Contextualizing Caste:

Post-Dumontian Approaches, ed. Mary Searle-Chatterjee and Ursula Sharma (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994),

49-71; and Searle-Chatterjee and Sharma, "Introduction," in Contextualizing Caste, 1-24.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 83

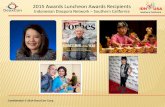

Figure 2. Dolly Ahluwalia as Anjali, Shri Vallabh Vyas as Bhaskar, Uttara Baokar as Vahini, and

Anang Desai as Sudhir in the National School of Drama Repertory Company production of Virasat, the Hindi version of Mahesh Elkunchwar's Wada Chirebandi. New Delhi, December 1985.

Photograph printed by permission of the National School of Drama Photography Department.

In keeping with the social history of the region, the problem of caste in the play is also inseparable from the politics of land. The traditional rural elite and dominant

landowning caste in Maharashtra are not brahmans but Marathas, members of the

kshatriya (warrior) caste-group whose modern icon is Shivaji, the late-seventeenth

century warrior-king. The Deshpandes' position as brahman landowners in Dharangaon is therefore not typical but atypical. The anti-brahman, anti-caste, and land reform

movements in Maharashtra have also been among the strongest in twentieth-century India, creating a powerful awareness about the problems of untouchability and

dispossession, but also mobilizing a form of reverse discrimination against the upper castes.27 When in Elkunchwar's play Bhaskar blames the "brahman haters" in the

village and the city for the loss of his patrimony (44), he is rationalizing his failures as a cultivator, landowner, and manager of family affairs, but he is also invoking?

27 In the late-colonial and early-postcolonial period, the most powerful critique of caste in Maharashtra

came from B. R. Ambedkar, the leader and intellectual who was bom an "untouchable" Mahar, became independent India's first law minister, and was instrumental in the constitutional abolition of

untouchability. It was in part due to his critique that Gandhi moved away from his tolerant attitude

towards caste, named the untouchables "Harijans" (children of God), and made their enfranchisement a cornerstone of his social and political philosophy. In 1956, disenchanted by continued discrimination

against the lower castes in independent India, Ambedkar led the mass conversion of 200,000 Mahars to Buddhism in Nagpur, the largest city in the Vidarbha region where Elkunchwar's play is set.

84 / Aparna Dharwadker

especially for a Marathi audience?the long- and short-term cultural history of the

state. In addition, the Vidarbha and Marathwada regions have had a strong farmers'

movement which seeks to transform the political and cultural economy of the

countryside. As Gail Omvedt reminds us, such a movement is no longer about

sharecroppers or poor peasants fighting their landlords: it involves "'independent

commodity producers/ peasants caught up in the throes of market production,

dependent on the state and capital for their inputs of fertilizer, pesticides, seeds,

electricity and water and for the purchase of their products."28 As cultivators, the

castes that have been "low" in the traditional ritual hierarchy have become economi

cally empowered as well as politically enfranchised in recent decades. For a contempo

rary Indian audience, therefore, the high-toned helplessness of the Deshpandes in

Wada Chirebandi confirms that their obsolete methods of cultivation have failed in a

fiercely competitive agrarian economy, while their pride of birth has become irrelevant

in an entrepreneurial culture.

The problems of caste and land are thus most pertinent to the family's relations with

the outside world. Bhaskar's adversarial relationship with Sudhir and Anjali, the

"Bombay couple," recasts the problem within the house as a tension between village and city, and between the cultures of two regions within Maharashtra, Vidarbha and

Konkan. Sudhir's migration to the metropolis twenty years earlier for the sake of

better professional prospects was part of the process of recession that has left only the

"dregs" in the village. The rest of the family is acutely aware of this attrition because

the mimicry of urban pop culture in the village of Dharangaon has already ruined the

youngest generation of Deshpandes, turning Parag into an alcoholic and Ranju into a

self-centered fantasist. Sudhir has fashioned for himself in Bombay a difficult goal oriented lower-middle class existence in a two-room flat, but for his village relations

his life appears to have all the romance of freedom and self-sufficiency. Sudhir's

journey replicates on a smaller scale the geographical, material, psychological, and

cultural displacements of diaspora?from periphery to centre, from plenty to scarcity, from community to isolation, and from constraining tradition to ambiguous freedom.

Predictably, he feels the same kind of nostalgia for home and the desire for eventual

return that members of a diaspora feel for the homeland. That is why he refuses to

jeopardize the house for the sake of Tatyaji's funeral expenses: "It's because of this

house, because it calls to us so strongly, that we come running. If this goes, then our

home will be gone" (45).

The one truly liminal figure in this crisis of opposed loyalties is Anjali, Sudhir's

Bombay-born Konkani wife, who was ostracized by the family for years because of her

lower caste status. In the course of the play, the politics of family become polarized around the geopolitical terms "Varhad" (the vernacular Marathi name for Vidarbha

that the family uses), and "Konkan," with the Varhadis being associated with ritual

superiority, ancestral pride, tradition, generosity, innocence, and warmth, but also

with wastefulness and impotence, and the Konkanis with a self-centered modernity,

territoriality, coldness, and cunning, but also with beauty, intelligence, and success. A

major feature of the original Marathi play is the difference of speech between Anjali

28 Gail Omvedt, Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India

(Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, 1993), 100-101.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 85

and the Deshpande family, with Sudhir suspended between the registers of the city and the country; regrettably, this is "a dimension which could not be accommodated in

the [English] translation."29 Anjali finds it irritating that her husband should begin

talking like the locals whenever he visits home, while Sudhir teases her about her

unresponsiveness to "the sweetness of the Varhadi language" (52). The family resents

Anjali's indifference to its many troubles, but the ambivalence of belonging/not

belonging and the insidious power of place emerge at the end when she unknowingly

lapses into local forms of speech.

The various thematic strands in the play?caste and land, tradition and modernity, wealth and impoverishment?come together in the symbolism of two antithetical

objects, the tractor sunk into the ground in the Deshpandes' front yard, and the family

gold (in the form of women's ornaments) that Bhaskar has concealed from everyone else within the house. Both objects are useless in the present, but their potential for use

calls up past failures and future possibilities. The tractor is a ruined artifact of

technology, which Bhaskar could not control even though his family's well-being

depended on it. Its condition is exactly like that of the decrepit mansion: in a parody of myth, Vahini compares it to the ceremonial bull, Nandi, which guards Shiva's

temple, and confers on the Deshpandes the divinity they claim by virtue of their ritual

status. In practice, the tractor is a daily menace to family members, causing injury to

several of them in the dark. The gold is an inert but real form of wealth which, unlike

everything else around it, has remained unchanged in appearance, and appreciated

unimaginably in value. It is also "much more" than just gold. In the play's most

theatrical scene (64-65), the only moment when the feminine tradition within the

mansion asserts itself, Vahini puts on all the gold ornaments at night at her husband's

urging, and feels transformed by the ghostly touch of the female ancestors who have

passed down the heirlooms over a century (Fig. 3). Conversely, as a saleable

commodity, the gold represents the only hope of a new life somewhere else for Aai,

Prabha, and Chandu. But Aai also has the moral sense to recognize that this wealth,

although a feminine possession, was created by the labor of generations of peasants, and the Deshpandes have no real claim to it.

The symbolism of these two objects, the tractor and the gold, culminates when they become the final agents of dynastic collapse. A cut in the dark against the tractor

causes gangrene in Chandu's leg, bringing him close to amputation, if not death;

Ranju steals the gold and elopes to Bombay with her English tutor in the hope of

fulfilling her fantasies of movie stardom. In a pathetic attempt to preserve the family honor, Bhaskar refuses to report the loss to the police, and sells the remaining acres of

family land at a throwaway price to meet the obligatory expense of Tatyaji's last rites.

Filled with the dead and the dying (Tatyaji, Dadi, Aai, Prabha, Chandu,, the decaying structure of the house is all that is left at the end, though in a moment of overdetermined

irony, Vahini invites Anjali and Sudhir to return whenever they wish to because it is

still their "home."

29 Samik Bandyopadhyay, "Introduction," Makesh Elkunchwar, Old Stone Mansion, trans. Kamal

Sanyal (Calcutta: Seagull, 1989), ix.

86 / Aparna Dharwadker

Figure 3. Uttara Baokar as Vahini and Shri Vallabh Vyas as Bhaskar in the National School of

Drama Reportory Company production of Virasat, the Hindi version of Mahesh Elkunchwar's

Wada Chirebandi. New Dehli, December 1985. Photograph printed by permission of the National School of Drama Photography Department.

Home Under Siege: The Politics of Religion and Community

In Wada Chirebandi, the mansion's inhabitants maintain an oppositional relation to

home as physical and ideological space even as they submit to its codes: if only they could get away, they would find a better life somewhere else. In contrast, Cyrus

Misery's Doongaji House creates a relationship of identity between home and its

occupants because there is nowhere else to go, and together they are paradigmatic of

the minority Parsi community negotiating majority Hindu culture in metropolitan

Bombay. An exclusively Parsi residential building in a predominantly Parsi neighbor hood, Doongaji House shows "alarming signs of age and degeneration" at the

beginning, and collapses with the arrival of the first monsoon rains, killing its oldest

resident and displacing all the others. But unlike the wada, it is not so much a subject in itself as a figure for the collective alienation of Parsis in a city they had dominated

for more than a century, during the latter half of the colonial period. This homology between decaying structures and the state of the community seems to be common

place. Tanya M. Luhrmann's recent ethnographic account of Parsis begins with a

vignette of Fort House, the central Bombay residence of Sir Jamshetji Jeejeebhoy, a

wealthy Parsi businessman who became the first Indian baronet: "gutted by fire and

abandoned by commerce, the facade is an icon of a community in decline."30 Mistry

30 Tanya M. Luhrmann, The Good Parsi: The Fate of a Colonial Elite in a Postcolonial Society (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1996), 1.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 87

also describes the building in his play as "a metaphor for the community as a whole,"31 and notes in his stage directions to Doongaji House that in performance the same

thematic effect may be created through abstract rather than naturalistic visual means

(viii).

The narrative of Parsi ascent and decline can be understood only with reference to

the community's unique, millennium-long history in India. Parsis are Zoroastrians

who arrived in western India sometime after the Muslim Arab conquest of Persia in

the seventh century, and for several centuries remained concentrated in the state of

Gujarat, especially around the port of Surat. Their association with Bombay began in

the seventeenth century, when the British decided to develop the cluster of islands

acquired from the Portuguese in 1662 as a major port city, and invited Parsi craftsmen

to help with shipbuilding. Over the next two centuries, Parsis contributed more than

any other Indian community to Bombay's development as India's leading colonial

port and financial capital. At the height of their influence in the later nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries, they controlled a large portion of Bombay's industry,

banking, business, and trade, and were also prominent in the professions of law,

medicine, and education.32 This transformation of a diasporic community into a

colonial elite depended on a range of deliberate choices. Parsis identified completely with British colonial culture and enterprise, in the belief that these were inherently

superior to the Indian models, and also allowed the best traits in the Parsi character to

emerge after centuries of suppression. Luhrmann comments that "under colonial rule, the attributes of the good Parsi became hierarchized, in part through the adoption of

hierarchized British self-description: like the British colonizer, the good Parsi was

more truthful, more pure, more charitable, more progressive, more rational, and more

masculine than the Hindu-of-the-masses."33 The differences of race and religion from

the Indian majority, which had always set the Parsis apart, now became the basis of

arguments for racial and religious superiority to the "natives," leading to an obsession

with endogamy and eugenics. In the late colonial period, this sense of separation from

the rest of India also meant the detachment of most Parsis from the dominant Hindu

Muslim polarities of Indian history, culture, and politics. This insularity was volun

tary, not forced: the Parsis' relation to the native majority was radically different from

that of other diasporic rninorities, such as the Jews in North Africa, who regarded "colonization by the French, the English, and the Italians ... as a guarantee of

survival."34

The principal difficulty for the contemporary Indian Parsi community is that their

attitudes of racial, religious, and cultural exclusiveness carried over from the colonial

into the postcolonial period, without the contexts that had provisionally sustained

them. Again, as Luhrmann notes, "Parsis identified themselves with the symbolic discourse of colonial authority, and in the absence of that authority have applied the

low-status end of the hierarchical symbolism to themselves. They have been trapped, as it were, by a colonial world view that has not yet (for Parsis in India, at any rate)

31 Comment by Cyrus Mistry to Tanya M. Luhrmann, reported in Luhrmann, Good Parsi, 60. 32 See Luhrmann, Good Parsi, 83-125, passim, for an account of Parsi settlement in India and the

community's role in the development of Bombay. 33

Luhrmann, Good Parsi, 16. 34

Albert Memmi, Jews and Arabs, trans. Eleanor Levieux (Chicago: J. Philip O'Hara, 1975), 12.

88 / Aparna Dharwadker

adjusted to the change in power of the postcolonial era."35 The thousand-year history of the Parsis in western India has thus been foreshortened into a colonial/postcolonial

opposition, because Parsi memory itself still circulates within the boundaries of

colonial-era glory and postcolonial disempowerment. But there is also another

problem here?that of a minority community not being able to find a place for itself in

a new nation?which suggests a similarity between the Parsis and other postcolonial

ethnoreligious minorities, such as the Tunisian Jews described by Albert Memmi: "The

religious state of nations being what it is, and nations being what they are, the Jew finds himself, in a certain measure, outside of the national community.

... I feel more

or less set apart from that life of communal nationality; I cannot live spontaneously the

nationality modern law grants me (when it does grant it).... Whether I like it or not, the history of the country in which I live is, to me, a borrowed history."36 Although

Parsis continue to be unusually prominent in "the life of communal nationality," a

community that demographically represents about one sixth of one percent of the total

Indian population is bound to experience a revision of roles in a heterogeneous society.

Mistry's play incorporates these constitutive features of Parsi identity with ethno

graphic thoroughness. The aging protagonist Hormusji Pochkhanawalla displays the

eccentric combination of Zoroastrian orthodoxy, colonialist nostalgia, and evident

poverty which has created the stereotype of the crazy Parsi bawaji (old man). He in

turn regards his two sons as irresponsible, weak-willed young men of the type that the

community holds largely responsible for its rapid decline: the older one, Rusi, has

emigrated to Canada, and the younger, Fali, is an alcoholic bookie. Since both sons

have also violated the rules of endogamy?Rusi marries a Canadian and Fali a

Christian woman employed as a nanny?Hormusji considers them guilty of miscege nation, and feels that "the blood has been polluted" (20). This paternal outrage is

ironic because, following the loss of his family business thirty years earlier, Hormusji has lived off the labor of two women, his wife Piroja, and his daughter Avan, whose

salary supports the household. The look of disuse, decay, and impoverishment in the

Pochkhanawallas' three-room flat completes the community profile of once elegant but now forgotten lives, exposed to the outside world in all their oddity when the

building collapses and brings in outsiders for the first time:

Purveyor_What a house this is! By God! I didn't know such places existed. It's a museum

piece. A zoo! Such samples I've met today ... one better than the other. This house should

have been certified unfit for habitation years ago!

[58]

Mistry's most important tool for evoking the quality of Parsi life is language. The

native language of Bombay Parsis is a dialect of Gujarati called Parsi-Gujarati, though a substantial number of them choose to be monolingual in English. Mistry uses a

Gujarati-inflected English that places the speakers simultaneously in the two worlds of

their experience. In the medium of this language, Hormusji's childhood memories of

sacred kashti prayers and the Parsi Towers of Silence (funeral sites) can coexist with

memories of classical western music, family silver, French confectionary, imported

liquor, and games of rummy. Both his Zoroastrianism and his deep-rooted Europhilia

35 Luhrmann, Good Parsi, 17.

36 Albert Memmi, Portrait of a Jew, trans. Elizabeth Abbott (New York: Orion Press, 1962), 196-97.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 89

become credible. In addition, the dialect has the political effect of separating the tribe

from the majority languages of the city, Gujarati and Marathi.

Mirrored in language, the colonial/postcolonial dialectic that occupies present-day Parsis assumes a highly personalized form in Hormusji's consciousness, because he

regards political independence as simply an event that reversed his community's relation to the majority Hindu culture. In a double-edged critique that implicates both

minority and majority attitudes, Mistry confines Hormusji to a posture of immobiliz

ing rage which finds relief in fantasies of domination and violence. His most vivid

memory, for instance, is of the Prince of Wales's visit to Bombay in 1921, when Parsis

proclaimed their loyalty to the Crown by attending celebrations which were boycotted

by Indian nationalists. Hormusji recalls the event as a Parsi triumph because the

community overcame its Hindu opponents in the riots that left fifty-three people dead.

For him, the end of colonialism was therefore the end of personal and community

might, as well as civility and culture, and Hindu dominance in the present is an

illegitimate usurpation of colonial power.

You don't understand these people, Piroja . ..

They've got completely out of hand. They think it is their Raj now_Sometimes I just feel like taking a horsewhip and flaying them! . . . But those days are gone. The Parsis of old are all gone. This is a

generation of

schoolgirls.

[10]

The absence of such colonialist regret in Wada Chirebandi points to the fundamental

difference between Hindu and Parsi perceptions of colonial culture. Upper-caste zamindars were also privileged during the colonial period, but that does not lead the

Deshpandes in Elkunchwar's play to regard colonialism itself as an era of privilege. This disparity merely emphasizes the extent to which the Parsis' comprador status in

the colonial regime depended on their sense of racial and religious difference.

The present situation exacerbates Hormusji's contempt and hatred for the majority Hindu population because Mistry also incorporates in his play the political develop ments which have launched a new phase in the history of communal relations in

Bombay. Since its inception in 1968, the Shiv Sena (the "Army of Shiva"), a militant

Hindu organization, has argued for greater control of Bombay's economy and politics

by "sons of the soil," and expressed its larger territorial ambitions in the slogan "Maharashtra for the Maharashtrians." Based on language and caste, the Sena's

chauvinism is directed against all "outsiders"?Hindus from South India, Muslims,

Christians, or left-wing activists. But it is particularly infuriating to the Parsis because

of their deep involvement in the history and development of the city of Bombay. The

point is not whether Parsis are specifically targeted by the Sena's politics, but that

Hindu fundamentalism alienates, frightens, and angers this once-powerful minority, and that its writers regard communal differences as the defining condition of Parsi life.

Moreover, the Parsi-Hindu antagonism is a version of the more deadly enmity between Hindus and Muslims, which forms a backdrop of violence in Doongaji House.

In these respects, Cyrus Mistry's play is closely intertextual with Such a Long Journey (1991), the first novel by his younger brother, Rohinton Mistry, which also offers the same family- and community-centered narrative with a Parsi building at its core. In

the novel, Dinshawji, a close friend of the central character Gustad Noble, regards Shiv

Sena politics as a continuation of the violence that accompanied the demand for a

90 / Aparna Dharwadker

separate Maharashtra in the early 1950s, and blames the Sena for "wanting to make the

rest of us into second-class citizens."37 When passages from the two works are

juxtaposed, they reinforce each other's rhetoric of outrage:

Hormusji: A bunch of illiterates! That's what they are_Maharashtra for the Maharashtrians!

Indeed! After we Parsis have built the whole city! . . . Now if the British were here, they would have just flogged one or two of them in a public place.

[26]

What to do with such low-class people? No manners, no sense, nothing. And you know

who is responsible for this attitude?that bastard Shiv Sena leader who worships Hitler and Mussolini. He and his "Maharashtra for Maharashtrians" nonsense.

They won't stop till they have complete Maratha Raj.38

Aside from the language riots of the early 1950s, the city of Bombay had avoided

serious civic confrontation until the communal riots of January 1993, which happened in the wake of the Babri Masjid episode in Ayodhya. Yet an atmosphere of frustration,

fear, and violence prevails in Doongaji House, which was written in 1978?the sign of a

postcolonial politics which deliberately, and tragically, manipulates religious and

communal difference.

The similarity between the two Parsi texts by the Mistry brothers and the anxiety of

the central female character in Rahul Varma's No Man's Land, a play about an

immigrant Indian Muslim family in Montreal, introduces yet another perspective on

disenfranchisement. It suggests that the situation of the Bombay Parsis is not unlike

that of a diasporic minority confronting separatist and chauvinistic movements

among the majority population in the host country, which endanger one's already

endangered home, but under conditions of peculiar powerlessness.

Jeena: (internal) Lately the separatists are gearing up to do their thing again, (sarcastically) "Le Qu?bec aux Qu?b?cois." I remember such slogans back in India the year we lost

everything. If it wasn't for them, we wouldn't have fled our home in the first place. And I wouldn't have been killing myself to make a home because we had a home back home. I

want to grab hold of one of those separatists and shake him up: "Do you know what you are doing? Look at me. This is what fleeing home has done to me. It is for people like you that a man has to run away with a brick in his hand." Companies

are closing all over since

the separatists got active again.... Just the thought that I may be uprooted a second time

in my life frightens me to death.39

The expatriate woman in Varma's play has a major stake in her city of adoption, but no

sense of affiliation with the host culture, and no political power in Canada. The Parsis'

alienation from the majority community in India is so intense that they seem still to be

in diaspora, although their anger is stronger because the Hindu majority wants to take

away precisely what they think they had created and possessed. Jeena's memories of

loss in India also suggest that for minority communities, there is little difference

37 Rohinton Mistry, Such a Long Journey (1991; New York: Vintage, 1992), 39. The formative idea

behind the state of "Maharashtra" was that it would be the home of the Marathas. The demand for the

state led to months of language riots between Marathi and Gujarati speakers in Bombay, and the state

was eventually carved out of territories belonging to the Bombay Presidency and two other states of

British India, Gujarat and the Central Provinces. 38 Rohinton Mistry, Such a Long Journey, 73. 39 Rahul Varma, No Man's Land, in Ravel, Canadian Mosaic, 190.

DIASPORA, NATION, AND THE FAILURE OF HOME / 91

between "homeland" and diaspora: they feel equally unwanted in both, and diaspora

merely reproduces the conditions that had led to the loss of home in the homeland. But

it is also possible to formulate the relation between the home-nation and diaspora in

another way: diaspora offers the promise of a home that the nation denied, but for

those who do not or cannot leave (like Hormusji and Piroja), the loss of home is

irrevocable.

Re-Locating Postcolonial Indian Theatre

Wada Chirebandi and Doongaji House are postcolonial texts in that the crises they enact are rooted in colonial history and the dynamics of decolonization. In terms of a

recent definition of the features of postcolonial drama, they represent "acts that

respond to the experience of imperialism, whether directly or indirectly."40 They also

represent gender and nationhood in ways that coincide with current emphases in

postcolonial theory, but can only be mentioned in passing here. In both plays the

destruction of home results from the anachronistic impositions of an ineffective or

corrupt male will?that of Tatyaji and Bhaskar in Wada Chirebandi, and Hormusji in

Doongaji House. Both also show the patriarchal order as being easily undermined, by a

subversive female will that deconstructs the identity between female virtue and family honor (Ranju's flight to Bombay in Wada Chirebandi), or a liberated female will that

rejects male authority (Avan's departure from home at the end of Doongaji House). Women are the more resourceful and resilient gender, whether they resort to cautious

territoriality (Vahini, Anjali, Avan) or offer sympathetic community (Prabha, Aai,

Piroja). Furthermore, the critique of patriarchy in both plays extends to the nation as a

male conception. The analogy here is between home as a male possession and material

construct (something deliberately put together), and the nation as an imagined

community?the disintegration of the former points to a fundamental conceptual flaw

which destroys the latter. In Elkunchwar's play, the mansion is said to be on the verge of collapse because "there is no upkeep" (22), but it cannot be kept up because it is so

large?the very grandeur of the conception makes the edifice unsustainable. Likewise,

Hormusji wonders at the end of Mistry's play why the owner did not use "a sturdier

stone, a faster cement, when [he] decided to raise this house" (62), a lament that

applies both to the Parsi community and the nation, which now appears to be an

under-imagined or perhaps unimaginable community. These are conscious allegories of the crisis of secular nationhood in India, which is an important referent in the

postcolonial theorizing of the nation.

However, the dominant modern approaches to Indian performance and the current

emphases of postcolonial studies work against the constitution of contemporary Indian theatre as a postcolonial field. As Rakesh H. Solomon notes, "[o]rientalist refractions have often over-stressed the sacred, spectacular, and traditional aspects of

Indian performance but neglected its historical engagement in the contests of power. ... Shorn of the exotic features of 'Oriental' performance... the modern Indian theatre

has received little attention in the West, even though this theatre has played a pivotal

political role in both colonial and postcolonial India."41 This neglect remains unaddressed