Developmental family processes and interparental conflict: Patterns of microlevel influences.

Transcript of Developmental family processes and interparental conflict: Patterns of microlevel influences.

Developmental Family Processes and Interparental Conflict:Patterns of Microlevel Influences

Alice C. SchermerhornUniversity of Notre Dame

Sy-Miin ChowUniversity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

E. Mark CummingsUniversity of Notre Dame

Although there are frequent calls for the study of effects of children on families and mutual influenceprocesses within families, little empirical progress has been made. We address these questions at the levelof microprocesses during marital conflict, including children’s influence on marital conflict and parents’influence on each other. Participants were 111 cohabiting couples with a child (55 male, 56 female) age8–16 years. Data were drawn from parents’ diary reports of interparental conflict over 15 days and wereanalyzed with dynamic systems modeling tools. Child emotions and behavior during conflicts wereassociated with interparental positivity, negativity, and resolution at the end of the same conflicts. Forexample, children’s agentic behavior was associated with more marital conflict resolution, whereas childnegativity was linked with more marital negativity. Regarding parents’ influence on each other, amongthe findings, husbands’ and wives’ influence on themselves from one conflict to the next was indicated,and total number of conflicts predicted greater influence of wives’ positivity on husbands’ positivity.Contributions of these findings to the understanding of developmental family processes are discussed,including implications for advanced understanding of interrelations between child and adult functioningand development.

Keywords: interparental conflict, bidirectionality, daily diaries, dynamic systems methods

Several decades ago, Bell (1968) contradicted the widely heldview that parent–child relationships are unidirectional (parent tochild), arguing that children also influence their parents. Scherm-erhorn and Cummings (2008) outlined a theoretical framework forconceptualizing family influence processes that is consistent withthis perspective and with emerging views of families as consistingof interacting subsystems (Cicchetti, 2006; Cox & Paley, 1997).Described as transactional family dynamics, this approach exam-ines family members’ influence on one another, including mutualinfluence processes in interparental, parent–child, and sibling re-lationships, unfolding over various time scales. These time scalesrange from moment-by-moment developmental processes to long-term (longitudinal) developmental processes.

However, despite frequent calls for the study of reciprocaleffects of children on families and mutual influence processeswithin families, little empirical progress has been made. In thisstudy we addressed these questions in the context of maritalconflict, examining both children’s influence on marital conflict

within conflict episodes and patterns of intra- and interspousalinfluence from one conflict to the next, toward the goal of advanc-ing understanding of these family relations at the level of micro-processes.

Children’s Influence on Family

Since Bell’s work highlighting child effects, theorists haveacknowledged that children are active participants in parent–childrelationships (Cole, 2003; Emery, Binkoff, Houts, & Carr, 1983;Maccoby, 1984). Research has also demonstrated that siblingselicit differential treatment from parents (Tucker, McHale, &Crouter, 2003), and firstborn siblings’ characteristics influencesecond-born siblings’ characteristics (McHale, Updegraff, Helms-Erikson, & Crouter, 2001). Clark, Kochanska, and Ready (2000)found that maternal personality interacted with infants’ negativeemotionality to predict maternal parenting.

Yet, relatively few studies have tested child effects. Even fewerhave examined children’s influence on family systems other thanparenting, including marital functioning. Among rare exceptions,Jenkins, Simpson, Dunn, Rasbash, and O’Connor (2005) foundthat in families with high levels of marital conflict, child external-izing problems predicted increases in marital conflict. Schermer-horn, Cummings, DeCarlo, and Davies (2007) reported that chil-dren’s agentic behavior during marital conflict, defined as activehelping behavior intended to diminish conflict, predicted decreasesin marital conflict, whereas children’s dysregulated behavior dur-ing conflict, defined as misbehavior and aggression, predictedincreases in marital conflict.

Alice C. Schermerhorn and E. Mark Cummings, Department of Psy-chology, University of Notre Dame; Sy-Miin Chow, Department of Psy-chology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health andHuman Development Grant HD036261 to E. Mark Cummings.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alice C.Schermerhorn, who is now at the Department of Psychological and BrainSciences, Indiana University, 1101 East 10th Street, Bloomington, IN47405. E-mail: [email protected]

Developmental Psychology © 2010 American Psychological Association2010, Vol. 46, No. 4, 869–885 0012-1649/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0019662

869

Although children have been found to be vulnerable to theeffects of family adversity and marital conflict (e.g., Crockenberg,Leerkes, & Lekka, 2007; Valentino, Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth,2008), few studies have explored how children may help shape thedynamics of marital interactions. Moreover, studies examiningreports of family interactions are lacking. Thus, although demon-strations of these mutual influence processes in the context oflongitudinal research designs are vitally informative, there is scantcorresponding study of these patterns of influence in “real time,”for example, using reports of actual family interactions in thehome. Such work could confirm, or even dispute, findings basedon other research designs regarding children’s influence on maritalconflict.

Marital Partners’ Influence on One Another

Study of the influence of spouses on one another (Cook &Snyder, 2005) also contributes to the growing literature on dy-namic interdependency among family members. Studies have ex-amined patterns of demand/withdraw behavior and gender differ-ences in these patterns (Christensen & Heavey, 1990) and partners’efforts to influence one another during conflicts (Sagrestano,Christensen, & Heavey, 1998). Gottman, Swanson, and Murray(1999) found that spouses and their interactions influence oneanother and predict marital outcomes.

Moreover, diary studies have contributed substantially to thestudy of influence in intimate relationships (Larson & Almeida,1999). For example, Laurenceau, Feldman Barrett, and Rovine(2005) found that self- and partner disclosure and perceived part-ner responsiveness predicted more couple intimacy. Story andRepetti (2006) found that husbands’ and wives’ negative socialinteractions at work and wives’ heavy workloads predicted moremarital negativity. Furthermore, whereas both husbands and wivesbring work stress into the home, husbands’ work stress influenceswives’ completion of household work more than wives’ workstress influences husbands’ housework (Bolger, DeLongis,Kessler, & Wethington, 1989).

Using dynamical systems modeling, Boker and Laurenceau(2006) found mutual influence among husbands’ and wives’ inti-macy and disclosure. Husband intimacy and disclosure were linkedwith a slowdown in the rate of change in wives’ intimacy anddisclosure, and the same effect on husbands’ intimacy was foundfor wife intimacy. Marital adjustment was associated with greaterself-regulation of intimacy. Here, we extend this direction, includ-ing investigation of possible differences in husbands’ and wives’influence, measuring interspousal dynamics in the presence ofchild influences in an intensive repeated-measurement framework.We use methods based on dynamic systems theories to shed lighton how these dynamics unfold.

The Current Study

The current study examines family influence processes withmethods inspired by general systems theories, which emphasizethe process of development (Sameroff, 1995; Thelen & Ulrich,1991). Utilizing parents’ diary reports is an innovative approach toprocess-level assessment of marital disagreements (Cummings &Davies, 2002). In comparison with questionnaires or laboratory-based procedures, diary approaches provide a more ecologically

valid window into these processes (Laurenceau & Bolger, 2005)that focuses on everyday, spontaneously occurring family events.Marital negativity predicts children’s negative emotional re-sponses and adjustment problems (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, &Papp, 2003, 2004; Cummings, Goeke-Morey, Papp, & Dukewich,2002). Building on this work, this study examined child-to-parentinfluence.

We examine, relatedly, whether longitudinal findings demon-strating children’s influence on marital conflict over the course ofa year (Schermerhorn et al., 2007) can also be observed at amicrolevel in the context of individual conflict episodes. Second,partners’ influence on each other—that is, associations of eachpartner’s emotions and behavior in one conflict with each partner’semotions and behavior in the next conflict—is investigated. Suchcarryover is expected in a self-regulating system, as partnerscontinue to reflect on their conflicts after the conflicts end(Schermerhorn & Cummings, 2008). For example, a spouse maydecide to exercise more restraint in the next conflict, inhibitingexpressions of anger, or, alternatively, to continue to harbor angryfeelings, fostering more negativity the next time around.

We use dynamic systems modeling tools to address how inter-parental dynamics operate at the microlevel and to examine theinfluence of children on interparental conflicts. We use the termdynamic systems to refer broadly to systems that change over time,and we define dynamic systems techniques as the repertoire oftools that can help extract and represent patterns of change. Ourkey dynamic systems model, known in the time series literature asvector autoregressive (VAR) models (Shumway & Stoffer, 2004;Wei, 1990), allows us to consider the lead–lag relationships be-tween husbands and wives as two coupled dynamic systems, whileevaluating the roles of children in influencing this dynamic pro-cess.

We formulate the autoregressive model within a mixed-effectsmodeling framework and focus on interfamily differences in de-viations from, and recovery toward, equilibrium. Within the con-text of our models, equilibrium refers to each individual’s mean ona construct over the entire span of the data after removal of thelinear trend in the data. Different individuals may have differentequilibria that reflect different degrees of marital positivity, neg-ativity, or conflict resolution. For example, when perturbed, wivesmight move back and forth past their respective equilibria beforereturning to their equilibria, whereas husbands might not be aseasily perturbed or steered away from their equilibria in the firstplace. Models like this have been useful for depicting processessuch as emotion regulation (Chow, Ram, Boker, Fujita, & Clore,2005).

The need to study complex patterns of change has arisen indiverse areas such as age differences in dynamic emotion–cognition linkages (Chow, Hamagami, & Nesselroade, 2007), thelinks between the rigidity of parent–child interactions and childexternalizing problems (Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Sny-der, 2004), the study of dyadic interaction processes (Ferrer &Nesselroade, 2003), the study of life span developmental processes(Ferrer et al., 2007), and other intensive repeated-measures studies(Walls & Schafer, 2006). The current approach advances study ofone kind of change process, namely, developmental processes infamilies. This is an important gap in contemporary studies ofdevelopmental processes. The explicit emphasis on change indynamic systems–inspired tools (Thelen & Smith, 1994; West,

870 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

1985) renders them particularly suited to these questions. Thedynamic systems approach offers the potential to yield uniqueinsights into family influence processes at a level of analysis thatcannot be captured by other techniques.

Analyzing the dynamics of microlevel developmental processesin families thus makes a novel methodological and measurementcontribution for addressing the important topic of mutual influenceprocesses in families. In this study we applied dynamic systemsmethods to examine development in the marital relationship overthe course of a 15-day period. That is, we examined husbands’ andwives’ influence on themselves and on their partners from oneconflict to the next. We also examined children’s influence on theirmothers and fathers within conflict episodes over this 15-dayperiod. In examining children’s influence, we distinguished be-tween children’s agentic behavior (i.e., intervention in maritalconflict aimed at resolving conflict) and children’s negativity (i.e.,negative emotions and dysregulated behaviors during marital con-flict). Our aim was to advance understanding of parents andchildren as participants in microlevel developmental processes infamilies with a data-intensive approach applied over a short-termperiod.

On the basis of previous work emphasizing the role of differ-ences between families in levels of functioning (e.g., Patterson,1997), we also tested marital satisfaction and number of conflictsas predictors of these developmental processes. We investigated(a) links between children’s agentic behavior and negativity duringconflict and marital conflict positivity, negativity, and resolution atthe end of interparental conflict; (b) influences of husbands andwives on themselves and on each other across occasions of con-flict; and (c) marital satisfaction and number of conflicts as pre-dictors of both (a) and (b). Children’s agentic behavior duringmarital conflict was hypothesized to predict less negative and morepositive and resolved marital functioning at the end of the sameconflict (Schermerhorn et al., 2007). Conversely, children’s dys-regulated behavior and emotional negativity were expected topredict more negative and less positive and resolved interparentalrelations at the end of conflict episodes. Additionally, we antici-pated that husbands and wives would influence one another fromone conflict to the next and that such dynamics would differ on thebasis of between-family differences in marital satisfaction and thenumber of conflicts.

Method

Participants

We collected data from a community sample of 116 cohabitingcouples from a midsized midwestern town. The data were drawnfrom a larger, longitudinal study of 299 families; the sample andstudy methods, including details of the diary methods, are de-scribed fully in Cummings et al. (2003). To be eligible to partic-ipate, couples had to have cohabited for at least two years and havea child 8–16 years old. Only participants who completed diaryreports (the first 116 families to participate in the study) wereincluded in these analyses. We were unable to use data from fivefamilies who completed the diaries because their data did not haveany variability. All analyses were, therefore, based on a sample of111 families. Children (55 male, 56 female) had an average age of10.83 years (SD � 2.15 years). Most couples (98%; n � 109) were

married; couples reported having been married for a mean of 12.65years (SD � 5.77). Mean age was 37.53 years (SD � 5.19 years)for wives and was 40.05 years (SD � 6.07) for husbands.

Participants were recruited through letters distributed throughlocal schools, referrals from other participants, flyers distributed atchurches and community events, and advertisements. Toward thegoal of obtaining a sample representative of the geographic area,we made efforts to include families of low socioeconomic status(SES) by recruiting at community events intended for low SESmembers of the community and by targeting postcard mailings tolow SES neighborhoods. In our sample, mean annual householdincomes ranged from $40,001 to $65,000. According to statisticsfor this county (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000), median householdincome was $49,653. Approximately 90.7% of children in oursample were European American; 6.5% were African American,1.8% were biracial, and 0.9% were Asian. The population byrace/ethnicity in this county in 2000 was 88% White, 8% Black,and 4% Hispanic, based on U.S. Census Bureau information. Inour sample, all wives had completed at least a high school educa-tion, and 35.1% had completed at least a bachelor’s degree; ap-proximately 98.2% of husbands had completed at least a highschool education, and 51.3% had completed at least a bachelor’sdegree. Among the population of this county in 2000, 82% hadcompleted at least a high school education and 24% had completedat least a bachelor’s degree.

Measures and Procedures

Marital satisfaction. Wives and husbands reported theirglobal marital satisfaction on the 15-item Marital Adjustment Test(MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959), which has demonstrated goodcontent and concurrent validity (Locke & Wallace, 1959). Wives’and husbands’ respective Cronbach’s alphas in this sample were.76 and .68. Some items assess the frequency of disagreementsregarding a variety of issues, such as handling finances, withanswer choices scaled from 1 (Always Agree) to 6 (Always Dis-agree). Other items assess overall happiness in the marriage andfrequency of confiding in the spouse. Response scales vary forthese items. Scores for the measure can range from 2 to 158; scoresbelow 100 suggest marital distress (Crane, Allgood, Larson, &Griffin, 1990). The mean marital satisfaction scores were 111.47for wives (SD � 23.51, range � 46.00–150.00) and 110.54 forhusbands (SD � 22.28, range � 50.83–156.00). Thirty wives(27%) and 33 husbands (29.7%) had MAT scores below 100, and48 couples (43.2%) included at least one partner with a scorebelow 100. Although percentages of distressed participants aresomewhat higher in our sample than in other community samples(e.g., McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, Lauretti, & Rasmussen, 2000), theaverage levels of distress are similar.

Marital conflict and children’s behavior. After each natu-rally occurring marital conflict, partners completed Marital DailyRecords (MDRs) and Child Report Records (CRRs; Cummings etal., 2003), providing measures of marital conflict episodes andchildren’s behavior during marital conflict over a 15-day period.We defined marital conflict as any major or minor interparentaldifference of opinion, regardless of whether it was primarily neg-ative or positive, and/or any interaction in which one or both

871DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

partners felt emotional tension, frustration, or anger. We providedeach couple with extensive training (approximately one hour),which included verbal, written, and videotaped depictions of eachitem on the MDR and the CRR. Partners were encouraged to askquestions during training, and they practiced completing the formsin the lab. For each variable, partners rated themselves and theirspouses. Parents rated their positive, angry, sad, and fearful emo-tions during and at the end of each conflict on a 10-point scalefrom 0 (none) to 9 (high) and indicated whether or not they hadengaged in (endorsed/not endorsed) any of 16 tactics during con-flicts or nine tactics at the end of conflicts. Parents also rated thedegree to which each conflict was resolved, using a 10-point scalefrom 0 (not at all) to 9 (completely). We defined a conflict endingas the point at which the parents stopped interacting. Thus, thediaries reflect discrete episodes rather than the general maritalclimate. Husbands and wives were instructed to complete theMDRs independently and to complete them as soon as possibleafter each conflict.

For each conflict that the target child was able to see or hear,parents completed the CRR, rating the child’s emotional responsesduring and at the end of conflict (positive, angry, sad, afraid) on a10-point scale from 0 (none) to 9 (high) and rating the child’sbehavioral responses during conflict (15 behaviors, endorsed ornot endorsed) and at the end of conflict (16 behaviors, endorsed ornot endorsed). Items tapping children’s agentic behavior werehelping out, comforting the parents, taking sides, and trying tomake peace. Items tapping children’s negativity were negativeemotions (anger, sadness, fear) and dysregulated behaviors (mis-behaving, yelling at the parents, aggression). Children exhibitedagentic behavior during 32.1% of the conflict episodes and exhib-ited negativity during 54.2% of the conflict episodes to which theywere exposed. Moreover, during nearly two thirds (64.4%) of theconflict episodes, children exhibited either agentic behavior ornegativity or both.

Because the number of diaries an individual completed wascontingent upon the number of conflicts that occurred, the numberof diaries completed varied across participants, ranging from 3 to69 (M � 14.60, SD � 12.10). Participants demonstrated goodreliability in rating the diary items on a matching task; values ofkappa ranged from 0.74 to 0.99 (M � 0.88) for wives and from0.69 to 0.96 (M � 0.85) for husbands. Moreover, wives andhusbands reliably coded during emotions and behaviors (for fa-thers, mean � � 0.81, range � 0.62–0.96; for mothers, mean � �0.89, range � 0.76–0.99) and ending emotions and behaviors (forfathers, mean � � 0.90, range � 0.80–0.98; for mothers, mean� � 0.96, range � 0.89–1.0). A recheck of reliabilities wasconducted several weeks later, and reliabilities remained highfor during (for fathers, mean � � 0.81, range � 0.58–0.99; formothers, mean � � 0.87, range � 0.60–1.0) and ending (forfathers, mean � � 0.85, range � 0.71–0.93; for mothers, mean� � 0.88, range � 0.71–0.93). Complete details regarding theMDR and CRR methodologies, including participant training andevidence of reliability and validity, are available elsewhere (Cum-mings et al., 2003, 2004; Papp, Cummings, & Goeke-Morey,2002). For the current study, our data consisted of diary reports ofa total of 2,157 conflicts. The mean length of time between conflictepisodes and completion of the diary reports was approximately

3.75 hours; 28.5% of the reports were completed within 30 min-utes of the conflict episode, 49.5% were completed within 2 hoursof the conflict episode, and 95% were completed within 13 hoursof the conflict episode.

Data Analysis

Data reduction, time-varying covariates, and between-family predictors. Correlations between husbands’ and wives’reports of their own and each others’ behavior ranged from r � .52for husbands’ and wives’ negativity to r � .67 for husbands’ andwives’ conflict resolution. All correlations were significant at thep � .001 level. Therefore, we created composite scores by aver-aging wives’ and husbands’ respective reports at the end of eachconflict. In line with approaches used elsewhere (e.g., Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Papp, 2007), composite scores were createdfor each spouse at the end of conflict indexing negativity (givingin, withdrawal/avoidance, verbal anger, anger, sadness, and fear),positivity (compromise and positive emotion), and conflict reso-lution (degree to which the problem was solved at the end).Negativity includes negative emotions and destructive marital con-flict tactics, which are those that result in more negative thanpositive emotional reactions in children (Goeke-Morey, Cum-mings, Harold, & Shelton, 2003), and positivity includes emo-tional positivity and constructive marital conflict tactics, which arethose that result in more positive than negative emotional reactionsin children (Goeke-Morey et al., 2003). This compositing pro-duced a score for each partner for negativity, positivity, andresolution, all at the end of conflict.

We used composite scores rather than factor analytic scoresbecause the participants at times showed idiosyncratic, occasion-specific endorsements of selected items. Thus, considerable miss-ingness would result if a factor analysis model were used to definethe associations among items independent of or as part of thedynamic models we fitted. Because we wanted to examine chil-dren’s influence on marital conflict using child behavior andemotions that temporally precede parent behavior and emotions,the parent composites consisted of variables from the ends of theconflicts and the child composites consisted of variables from theportion of the conflict occurring prior to the ending (i.e., duringconflict). Once the parent composites were formed, we removedthe linear trend for each individual and each variable separatelyand retained the residuals for model-fitting purposes. Removingthe linear trend removed intraindividual linear change (increases ordecreases) over the 15-day period and scaled all individuals’equilibrium points (mean of each dependent variable over thestudy span) to zero. We also replicated the analyses using datastandardized within persons across measurement occasions. Usingunstandardized data preserves all the between-persons differencesin response variability. In contrast, using standardized data pre-cludes any preexisting individual differences in response variabil-ity (and thus, any arbitrary response biases) and, in this vein, mayfacilitate evaluation of within-family changes at the group level.We focus on reporting results based on the unstandardized dataand note discrepancies between the two sets of results.

We created time-varying covariates for children’s behavior be-cause missing child data prevented us from entering the childvariables into the dynamic portion of the model. As with themarital composites, the time-varying covariates were created with

872 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

the average of husbands’ and wives’ reports, which correlated r �.28, p � .001 for child negativity and r � .41, p � .001 for agenticbehavior. The primary source of missing child data was interpa-rental conflicts that children did not witness; parents rated theirchild’s behavior only during conflicts the child witnessed. Becauseof excessive missingness in child data (�67% for all child-relateditems)—that is, the children were usually not there when theconflicts took place—we did not use the child variables as depen-dent variables. In other words, this excessive missingness makes itless theoretically justifiable to use children as the “modelingfocus” (i.e., as dependent variables). In terms of methodology, it isalso much more practical to include these categorical child-relatedvariables as covariates than as categorical dependent variables, asthe latter approach requires the use of more complicated modelingoptions. Instead, in order to create time-varying covariates reflect-ing children’s behavior and emotions during marital conflict, wecreated two dummy variables, ChildNegt and ChildAgentt. For eachconflict, the first variable, ChildNegt, was coded as a 0 if the childeither was not present during the conflict or was present but did notshow negativity (i.e., anger, sadness, fear, dysregulated behaviors);this variable was coded as a 1 if the child did show nega-tive emotions or dysregulated behaviors. The second variable,ChildAgentt, was coded as a 0 if the child either was not presentduring the conflict or was present but did not show any agenticbehavior; this variable was coded as a 1 if the child did showagentic behavior. This allowed us to use all of the conflict episodesand to compare marital conflicts in which children were absent ordid not engage in negativity or agentic behavior with maritalconflicts in which children were present and exhibited negativityand/or agentic behavior. That is, this specification allowed us totest whether child agentic behavior and negativity led to additionaldifferences over and above those contributed by the child’s merepresence during the conflict.

We used two between-family variables (i.e., Level 2 predictors)in our mixed-effects models to evaluate differences in dynamicsacross families. We used each family’s total number of conflictsover the 15-day study period as one between-family predictor.Marital satisfaction, indicated by husbands’ and wives’ MATscores, was used as another between-family predictor. Thesebetween-family predictors were standardized prior to model fittingto aid interpretation.

Data analytic plan. Prior to model fitting, we inspected eachparticipant’s auto- and partial autocorrelation plots on all the keydependent variables to determine the order of our proposed vectorautoregressive (VAR) models. Results suggested that a vectorautoregressive model of order 1, that is, a VAR(1) model, wouldlikely be appropriate. This means that most of the predictability inthe system is accounted for once information from the immediatelypreceding time point is incorporated. We fitted a series of VARmodels using the Proc Mixed procedure in SAS (Littell, Milliken,Stroup, & Wolfinger, 1996). Using the VAR(1) model as a startingpoint, we fitted a series of mixed-effects extensions of the VAR(1)model to examine (a) children’s agentic behavior and negativity aspredictors of marital positivity, negativity, and resolution; (b)dynamics within and between husbands and wives (autoregressiveand cross-regressive paths); and (c) between-family differences in(a) and (b), as a function of marital satisfaction and the totalnumber of conflicts over the 15-day period.

In the explications that follow, we present only the equations forpositivity scores, but the same model was fitted separately to thescores for the husband–wife dyads’ positivity, negativity, andresolution. We use i as an index for family and t as an index forconflict number. We first considered an unconditional mixed-effects bivariate AR(1) model with random effects for the auto-and cross-regression parameters and no between-family predictors,expressed asModel 1 (unconditional model):

Poswit � �Posw,t-13Posw,t,iPoswi,t-1 � �Posh,t-13Posw,t,iPoshi,t-1

� �1w,iChildNeg,it � �2w,iChildAgent,it � ePos,wit, (1)

Poshit � �Posh,t-13Posh,t,iPoshi,t-1 � �Posw,t-13Posh,t,iPoswi,t�2

� �1h,iChildNeg,it � �2h,iChildAgent,it � ePos,hit, (2)

�Posw,t-13Posw,t,i � a0 � uAuto_Posw,i

�Posh,t-13Posh,t,i � b0 � uAuto_Posh,i,

�Posh,t-13Posw,t,i � c0 � uCross_Posw,i,

�Posw,t-13Posh,t,i � d0 � uCross_Posh,i, (3)

�1w,i � �1w0, �2w,i � �2w0, �1h,i � �1h0, �2h,i � �2h0,

(4)

�ePos,wit ePos,hit�’ � N�0 0�’,diag�ePos,w

2 ePos,h

2��,

(5)

�uAuto_Posw,i

uAuto_Posh,i

uCross_Posw,i

uCross_Posh,i

�� N��

0000�,�

Auto_Posw

2

0 Auto_Posh

2

0 0 Cross_Posw

2

0 0 0 Cross_Posh

2�� ,

(6)

where Poswit represents the wife’s reported positivity at the end ofthe tth conflict in family i and Poshit represents the husband’sreported positivity at the end of the tth conflict in family i.ChildNeg,it is a dummy variable indicating whether any negativitywas manifested by the child in family i during the tth conflict (0 �no, 1 � yes), and ChildAgent,it is a dummy code used to identify thepresence of the child’s agentic behaviors in family i during the tthconflict. Here, we describe elements of the model in terms of ourthree modeling objectives, that is, to examine (a) the roles ofchildren’s agentic behavior and negativity as within-family, time-varying predictors, (b) the dynamics within and between spouses,and (c) between-family differences in (a) and (b).

Children’s agentic behavior and negativity as within-family,time-varying predictors. �1w,i and �1h,i represent the family-specific influences of child negativity on the wife and husbandmanifest positivity, respectively; �2w,i and �2h,i represent thefamily-specific influences of child agentic responding on the wife

873DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

and husband positive manifest variable, respectively. In Model 1,the regression parameters associated with the child-related covari-ates were constrained to be invariant across families (i.e., they arefunctions of the group-based intercepts, �1w0, �2w0, �1h0, and �2h0,but not other family-specific variables or components). This con-straint was relaxed in later models. In the present model,�1w0, �2w0, �1h0 and �2h0 capture the general influences of agenticbehavior and negativity (time-varying covariates) as predictors ofmarital positivity.

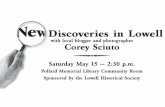

Dynamics within and between spouses. Hypotheses con-cerning the dynamics within and between husbands and wiveswere tested by evaluating the auto- and cross-regression parame-ters �Posw,t-13Posw,t,i, �Posh,t-13Posh,t,i, �Posh,t-13Posw,t,i, and �Posw,t-13Posh,t,i. Ofthese parameters,�Posw,t-13Posw,t,i is the lag-1 autoregression parame-ter capturing the influence of wife positivity at the previous con-flict (t-1) on wife positivity during the conflict at time t for familyi,�Posh,t-13Posh,t,i represents the lag-1 autoregressive influence of hus-band positivity at conflict t-1 on husband positivity for family i atconflict t,�Posh,t-13Posw,t,i represents the cross-regressive influence ofhusband positivity at conflict t-1 on wife positivity for family i atconflict t, and �Posw,t-13Posh,t,i represents the cross-regressive influ-ence of wife positivity at conflict t-1 on husband positivity forfamily i at conflict t. All of the auto- and cross-regression param-eters were represented as a function of an intercept (denoted as a0,b0, c0, and d0, respectively) and a family-specific deviation fromthe group-based intercept. The relative impact of the husband 3wife and wife 3 husband influences at the group level wasassessed with the statistical significance of the intercept parame-ters, c0 and d0. If, for example, model tests indicate that c0� 0 butd0� 0, that would indicate unidirectional coupling between hus-bands and wives, with husbands’ positivity being the “leadingindicator” of wives’ positivity. The family-specific deviation terms(i.e., uAuto_Posw,i, uAuto_Posh,i, uCross_Posw,i, and uCross_Posh,i) constitute therandom-effects components, which were assumed to be normallydistributed with a mean vector of zeros and a diagonal covariancematrix. The group-based intercepts and any between-family co-variates used to predict such deviations constitute the fixed-effectscomponents of the model. Figure 1 provides a depiction of the pathdiagram for Model 1.

Between-family differences in dynamics. To examinebetween-family differences in auto- and cross-regressive dynam-ics, we extended Model 1 to include marital satisfaction andnumber of conflicts as Level 2 predictors in Model 2. WhereasEquations 1, 2, and 4–6 remain unchanged in Model 2, Equation3 is now expressed asModel 2 (model with between-family predictors of parental dy-namics):

�Posw,t-13Posw,t � a0 � a1FMATi � a2NoConflicti � uAuto_Posw,i,

�Posh,t-13Posh,t � b0 � b1MMATi � b2NoConflicti � uAuto_Posh,i,

�Posh,t-13Posw,t � c0 � c1FMATi � c2NoConflicti � uCross_Posw,i,

�Posw,t-13Posh,t � d0 � d1MMATi � d2NoConflicti � uCross_Posh,i,

(7)

where FMATi denotes the wife’s marital satisfaction in family i,MMATi represents the husband’s marital satisfaction in family i,

and NoConflicti represents the total number of conflicts that oc-curred in family i over the study span.

To examine potential between-family differences in the roles ofchildren’s responses, we incorporated random effects into thechild-related regression parameters (Equation 4 in Model 1) andused marital satisfaction and number of conflicts as predictors ofbetween-family differences in these parameters asModel 3 (model with between-family predictors of child-relatedinfluences):

�1w,i � �1w0 � �1w1FMATi � �1w2NoConflicti � u�1w,i,

�1h,i � �1h0 � �1h1MMATi � �1h2NoConflicti � u�1h,i,

�2w,i � �2w0 � �2w1FMATi � �2w2NoConflicti � u�2w,i,

�2h,i � �2h0 � �2h1FMATi � �2h2NoConflicti � u�2h,i,

where �1w0, �1h0, �2w0, and �2h0 are the group-based intercepts ofthe effect of the child’s negativity on the wife’s positivity in familyi at conflict t, the effect of the child’s negativity on the husband’spositivity in family i at conflict t, the effect of the child’s agenticbehavior on the wife’s positivity in family i at conflict t, and theeffect of the child’s agentic behavior on the husband’s positivity infamily i at conflict t, respectively. The associated family-specificdeviations in these parameters are denoted, respectively, by u�1w,i,u�1h,i, u�2w,i, and u�2h,i.

In sum, Model 1 was used to test group-based notions about theinfluence of children’s behavior and emotions during marital con-flict on interparental positivity at the end of that conflict. That is,we examined whether and how the levels of parental positivitymight change at the end of a conflict depending on children’sbehavior and emotions during the conflict in general. In Model 2,we evaluated whether families with high marital satisfaction ormore conflicts were characterized by significantly different auto-and cross-regression parameters. That is, we sought to addresswhether the ways that marital conflicts unfolded over time mightdepend on marital satisfaction or frequency of conflict. Finally, inModel 3, we sought to assess whether children’s influence differedas a function of marital satisfaction or number of conflicts.

Instead of evaluating the roles of children aggregated across thetime points, all three models allowed children’s behaviors andemotions to influence the parents at each time point and thenextracted regularity across all the time points. Our models allowedus to examine within-person dependence and between-personcodependence in emotional and behavioral dynamics over the spanof the study.

To avoid estimating too many random-effects variance compo-nents simultaneously, we evaluated Models 1–3 sequentially. Weproceeded by evaluating the statistical significance of the random-effects variances (i.e., Auto_Posw

2 , Auto_Posh

2 ,Cross_Posw

2 , and Cross_Posh

2 inEquation 6) in Model 1 and retained only random-effects compo-nents for which the corresponding variances were statisticallysignificant. Thus, in Model 2, between-family predictors wereadded only to explain auto- and cross-regression parameters withsignificant between-family differences based on results from fit-ting Model 1. Subsequently, we retained only the statisticallysignificant estimates from Model 2 before proceeding to fittingModel 3, in which between-family differences in the child-relatedregression parameters were assessed.

874 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

As a measure of effect size, the proportion of reduction invariance at the between-family level when family-level covariatesare added as predictors (Hox, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999) canbe computed as

R2,x2 �

ux�Model w/o covariates2 � ux�Model with covariates

2

ux�Model w/o covariates2

where ux�Model w/o covariates2 is the variance for a particular random

effect of interest (e.g., variance associated with a random effect inan autoregressive parameter) in a model without family-level co-variates as predictors and ux�Model with covariates

2 is the correspondingvariance for the same random effect in a model with family-levelcovariates. This proportion of reduction in variance indicates theproportion of reduction in a particular random-effect variancewhen family-level (Level 2) covariates are included in the modelcompared to a baseline model without covariates.1 We have notprovided a measure of effect size at the within-family level be-cause it was less clear what an appropriate baseline might be forevaluating within-family effects. In the literature, a more compli-cated model is typically compared to an “intercept-only” baselinemodel with random effect for the intercept. However, this baselinemodel is not applicable in the present context; because of the detrend-ing procedure we undertook during data preparation, the intercepts in

our models are zero by default and there are no between-familydifferences in intercept.

Our formulation of the VAR(1) model differs from other stan-dard approaches for incorporating autoregressive components intothe residual error processes (see, e.g., Verbeke & Molenberghs,2000, pp. 98–101). First, we created lag-1 manifest variables forwife and husband positivity, negativity, and resolution.2 We thenused the lag-1 positivity, negativity, and resolution as manifestindependent variables in the mixed-effects VAR(1) models. Unlikeother standard approaches that incorporate AR processes into theover-time residual errors, this model formulation allows us toevaluate between-family differences in the auto- and cross-

1 Effect size measures for mixed-effects models are still an active area ofresearch, and there is currently no clear consensus on the optimal effectsize measure to use. Although some researchers have cautioned against theuse of this R2 measure because it is known to yield negative R2 values insome cases (Hox, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999), we chose to report thismeasure because of its intuitive appeal.

2 That is, if Poswit represents the wife’s positivity at time t (with t � 2,3, . . . T), Poswi,t-1 was created by lagging the time series of the wife’spositivity by one time point (with t � 1, 2, . . . T � 1) so the positivity att � 2 was matched with the wife’s positivity at t � 1 and so on.

Wife Positivityt-1,i

WifePositivityt, i

WifePositivityiT

iPosPos twtw ,,1, →−β

1

Error-WifePositivityit-1

1

Error-WifePositivityit

1

Error-WifePositivityiT

1 1 1

Error-HusbandPositivityiT

2,Positivityeσ 2

,Positivityeσ 2,Positivityeσ

2,Positivityeσ

2,Positivityeσ 2

,Positivityeσ

Husband Positivityt-1,i

Husband Positivityt,i

Husband PositivityiT

Error-HusbandPositivityit-1

Error-HusbandPositivityit

iPosPos twth ,,1, →−β

iPosPos thtw ,,1, →−β

Child Agentic Behaviorit-1

Child Agentic Behavior,it

Child Negativityit-1

Child Negativityit

Child Agentic Behavior,iT

iw,2β

Child NegativityiT

ih,2β

ih,1βiw,1β

iPosPos thth ,,1, →−β

Figure 1. Trajectories of wife positivity (1a), husband positivity (1b), wife negativity (1c), husband negativity(1d), wife conflict resolution (1e), and husband conflict resolution (1f) by family.

875DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

regression parameters at Level 2.3 SAS code for fitting Models 1–3is included in the Appendix.

Notably, the Proc Mixed procedure in SAS is designed specif-ically for univariate models. To fit the bivariate equations inModels 1–3, we used the procedure described in MacCallum, Kim,Malarkey, and Kiecolt-Glaser (1997), stacking husbands’ andwives’ responses into a single vector and using dummy indicatorsto combine the two processes into a single, univariate equation.We adjusted the denominator degrees of freedom for assessingstatistical significance of the fixed effects parameters using theKenward–Roger option (Kenward & Roger, 1997; Littell et al.,1996) to control for the inflation in Type I error rate due to thepresence of residual correlations among the repeated measure-ments and the arbitrary gain in degrees of freedom resulting fromstacking the husbands’ and wives’ responses into a single columnof responses.4

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Panels a–f of Figure 2 show the changes in positivity, negativity,and resolution in all families over all the conflicts. Most familiesreported fewer than 30 conflicts over the 15-day study span. Theplots suggest the appearance of less variability in positivity, neg-ativity, and resolution over time.

The absolute number of conflicts children witnessed (M � 6.48,SD � 5.70) was positively correlated with the proportion of theparents’ total conflicts that children witnessed (r � .46, p � .001),indicating that children who witnessed relatively large numbers ofconflicts witnessed a higher proportion of their parents’ conflicts.In relating the proportion of conflicts witnessed to parents’ reportsof marital conflict, we tested whether child presence during maritalconflict is associated with conflict endings. The proportion ofconflicts children were present for was uncorrelated with childgender, marital positivity, negativity, conflict resolution, maritalsatisfaction, and number of conflicts but was negatively correlatedwith child age (r � �.24, p � .05). As expected, given how thechild behavioral variables were coded, the proportion of conflictschildren were present for was positively correlated with childagentic behavior (r � .50, p � .001) and with child negativity (r �.66, p � .001). The lack of associations between children’s pres-ence and all of the marital constructs underscores the need to movebeyond simply examining associations with children’s presence, toexamine the influence of children’s behavior and emotions onparents from conflict to conflict.

Whereas the dynamic models summarized in Equations 1–7allowed us to evaluate the direct linkages among ongoing changesin child and parental variables from conflict to conflict, severalother issues could potentially affect the results from fitting thedynamic models. We thus conducted some preliminary analyses toclarify some of their linkages. To examine possible child genderdifferences in these constructs, we conducted independent samplest tests. The Type I error rate for these tests was adjusted using theBonferroni method; thus, the p value was calculated as .05/11 �.005. We found no gender differences in any of the primaryconstructs.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations based on averagesacross all the conflicts appear in Table 1. All of the marital

behaviors were correlated with one another and with marital sat-isfaction in the expected direction; number of conflicts was posi-tively correlated with marital positivity and negatively correlatedwith husbands’ negativity, and wives’ and husbands’ marital sat-isfaction were positively intercorrelated. The preliminary analysessuggest more associations between the marital dynamic constructsand the total number of conflicts, compared with the proportion ofconflicts witnessed by the child. In contrast, whereas child age wasnegatively associated with proportion of conflicts witnessed, it wasunrelated to the total number of conflicts. We chose to test the totalnumber of conflicts as a between-families predictor in our primaryanalyses, because it provides information about all the conflicts,rather than only the portion that children witnessed. Child age wasgenerally unrelated to the other constructs in Table 1.

Children’s negativity and agentic behavior were positively in-tercorrelated (see Table 1). This association highlights one impor-tant inadequacy in contemporary studies of developmental familyprocesses, namely, children are able to react to parental conflictsonly when they are present during the conflicts. The positiveassociation between these two variables is thus to be expected. Inaddition, agentic behavior correlated positively with husbands’ mar-ital satisfaction, and children’s negativity correlated positively withboth partners’ negativity, but neither of the child variables correlatedwith any other variables. These correlational results suggest thatevaluating the linkages between child and parent variables aggregatedover time does not reveal ongoing influence of children on parents.Furthermore, whereas children’s negativity and agentic behavior wereboth related to long-term marital outcomes in previous studies, theirprecise roles in marital discord from conflict to conflict had yet to beinvestigated with dynamic models.

Model-Fitting Results

We organized the results into three sections: marital positivity,negativity, and resolution. In each section, we discuss findings perti-

3 For comparison purposes, we fitted a simplified version of Model 1wherein all the random effects components in the mixed-effects modelswere omitted and a state–space maximum likelihood procedure imple-mented in a Fortran-based program, mkfm6 (Dolan, 2002), was used toestimate the model parameters. The parameter estimates and their associ-ated standard errors obtained using both approaches were very close to oneanother.

4 In the context of our modeling example, it is substantively meaningfulto allow the residuals of the husbands and wives (e.g., ePos,hit and ePos,wit inEquations 1 and 2) to be correlated. Current restrictions in SAS do notallow for correlations between husbands’ and wives’ residuals to be in-cluded in a straightforward way without imposing additional correlationsacross time points within these residuals, for example, AR(1) structure.However, such time dependency had already been explicitly incorporatedinto the fixed-effects structure of our proposed models. Including corre-lated residuals would thus lead to model redundancy and other estimationissues. This, together with the inclusion of bivariate responses and the useof the Kenward–Roger adjustment of degrees of freedom, limited us toadopt a simpler structure (i.e., a diagonal structure) for the residual errorsof husbands and wives. We did, however, compare the parameter estimatesobtained in SAS when no random effects and correlation between residualswere included to those obtained from fitting a comparable model in mkfm6(see Footnote 3) wherein correlation between the residuals was included.The estimates from SAS were very close to those obtained from mkfm6despite the omission of the correlation parameter.

876 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

nent to the child predictors (negativity and agentic behavior), theinterparental dynamics, and any between-family differences. We fo-cus on the unstandardized data, but we also discuss findings fromanalysis of the standardized data that differ from those of the unstand-ardized data. In each section, we report the results from the mostcomplicated, best fitting models based on Model 3; we also includethe estimates from the best fitting versions of Model 2 in Table 2.

Positivity. We hypothesized that children’s negativity wouldpredict decreases in marital positivity, that children’s agentic be-havior would predict increases in marital positivity, and thatspouses would influence their own and each others’ positivity.Results from fitting Model 3 indicated that children’s negativityduring interparental conflict was linked with less positivity be-tween the parents at the end of conflict and that children’s agentic

Figure 2. Path diagram of Model 1. t denotes the current conflict, t-1 denotes the preceding conflict, T denotesall of the conflicts, and i represents the individual family. �1w,i and �1h,i represent the family-specific influencesof child negative emotional or behavioral responding on the maternal and paternal manifest positivity, respec-tively; �2w,i and �2h,i represent the family-specific influences of child agentic responding on the maternal andpaternal positivity manifest variable, respectively. �Posw,t-13Posw,t,i represents the lag-1 autoregressive influence ofwife positivity at the previous conflict (t-1) on wife positivity during the conflict at time t for family i,�Posh,t-13Posh,t,i represents the influence of husband positivity at conflict t-1 on husband positivity for family i atconflict t, �Posh,t-13Posw,t,i represents the cross-regressive influence of husband positivity at conflict t-1 on wifepositivity for family i at conflict t, and �Posw,t-13Posh,t,i represents the cross-regressive influence of wife positivityat conflict t-1 on husband positivity for family i at conflict t. The family-specific deviation terms (e.g.,Error-Wife Positivityit, Error-Husband Positivityit) constitute the random-effects components, and e,Positivity

2

represents the variance of the random-effects components.

877DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

behavior, on the other hand, was associated with more positivity(see Table 2). Thus, children’s negativity is associated with lessmarital positivity, and agentic behavior is associated with moremarital positivity.

Our hypothesis of influence from one conflict to the next waspartially supported for interparental positivity. We found that

husbands’ positivity was influenced by husbands’ positivity at theend of the immediately preceding conflict; when husbands re-ported levels of positivity that were above their own average, theytended to report lower levels of positivity at the end of the nextconflict. Husbands’ negative autoregressive weight suggests thathusbands’ trajectory tended to fluctuate considerably around a

Table 1Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Between the Marital and Child Constructs

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

1. C agentic —2. C negativity .49��� —3. W positivity .10 �.15 —4. H positivity .14 �.11 .91��� —5. W negativity .03 .20� �.44��� �.36��� —6. H negativity .09 .24� �.44��� �.50��� .76��� —7. W resolution .14 �.07 .76��� .69��� �.42��� �.42��� —8. H resolution .12 �.11 .76��� .73��� �.32��� �.42��� .94��� —9. C age .01 �.17† �.07 �.13 .11 .18† �.10 �.10 —

10. W satisfaction .12 �.10 .26�� .20� �.31��� �.18† .17† .13 .01 —11. H satisfaction .19� �.03 .31�� .28�� �.29�� �.28�� .31��� .30�� .05 .50��� —12. No. conflicts �.08 �.10 .21� .22� �.15 �.19� .17† .14 .14 �.05 �.05 —M .11 .19 2.81 2.90 .80 .76 5.12 5.29 10.83 111.47 110.54 19.48SD .12 .15 .73 .73 .54 .53 1.40 1.41 2.15 23.51 22.28 13.11

Note. N � 111. Means, standard deviations, and correlations were computed on the unstandardized data prior to detrending. C � Child; W � wife; H �husband; agentic � agentic behavior; C negativity � child negativity; positivity � positive marital emotions/behaviors; W/H negativity � negative maritalemotions/behaviors; resolution � marital conflict resolution; satisfaction � Marital Adjustment Test marital satisfaction; No. conflicts � number of conflictepisodes; SD � standard deviation.† p � .10. � p � .05. �� p � .01. ��� p � .001.

Table 2Parameter Estimates for the Final Models

Final Model 2 Final Model 3

Parameter Positivity Negativity Resolution Positivity Negativity Resolution

�1w �.40 (.08)��� .22 (.04)��� �.77 (.18)��� �.40 (.08)��� .22 (.04)��� �.77 (.18)���

�1h �.42 (.08)��� .22 (.05)��� �.79 (.17)��� �.42 (.08)��� .21 (.05)��� �.79 (.17)���

�2w .21 (.10)� � 0 .58 (.23)� .21 (.10)� � 0 .58 (.23)�

�2h .25 (.10)� � 0 .76 (.23)��� .25 (.10)� � 0 .76 (.23)���

�Xw,t-13Xw,t� 0 �.06 (.02)� � 0 � 0 �.06 (.02)� � 0

�Xh,t-13Xw,t� 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

�Xh,t-13Xh,t�.05 (.03)† � 0 � 0 �.05 (.03)† � 0 � 0

�Xw,t-13Xh,t� 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

NoConflict � �Xw,t-13Xw,t� 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

NoConflict � �Xh,t-13Xw,t� 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

NoConflict � �Xh,t-13Xh,t� 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

NoConflict � �Xw,t-13Xh,t.09 (.03)�� � 0 � 0 .09 (.03)�� � 0 � 0

NoConflict � �1w � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0NoConflict � �1h � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0NoConflict � �2w � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0NoConflict � �2h � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 � 0

Note. The unstandardized regression coefficients are reported, followed by the standard errors in parentheses. Marital satisfaction is not depicted in thetable because it was not a significant predictor of any of the between-family differences. The proportion of reduction in variance at the between-family levelresulting from adding number of conflicts as a predictor of the wife3 husband positivity cross-regression was .14. The “X” in the equations for the dynamicmodel (e.g., �Xw,t-13Xw,t) represents positivity, negativity, or conflict resolution, depending on the marital construct being modeled. The equal sign before thezero indicates parameters that we fixed equal to zero. �1w � influence of child negativity on the wife; �1h � influence of child negativity on the husband;�2w � influence of child agentic behavior on wife; and �2h � influence of child agentic behavior on husband; �Xh,t-13Xh,t � autoregressive path for husbands;�Xw,t-13Xw,t � autoregressive path for wives; �Xw,t-13Xh,t � cross-regressive path for wives at time t-1 to husbands at time t; �Xh,t-13Xw,t � cross-regressive pathfor husbands at time t-1 to wives at time t. NoConflict � total number of conflict episodes; the rows that include NoConflict represent the tests of numberof conflicts as a predictor of between-family differences in the auto-, cross-, and child-related regression parameters.† p � .10. � p � .05. �� p � .01. �� p � .001.

878 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

point of equilibrium, or baseline (Wei, 1990). Thus, when theirpositivity is pushed away from its equilibrium, it tends to moveback and forth past the equilibrium to a significant degree. That is,husbands’ behavior and emotions during one conflict episodecould be predicted from husbands’ behavior and emotions at thepreceding time point in a negative direction. In other words, if ahusband had a high level of positivity at one time point, he tendedto have a low level of positivity at the next time point. Notably,there was no evidence of predictability from one time point to thenext for the wives. That is, there was no continuity, or predictabil-ity, in how wives “self-regulate” these constructs back to theirequilibria.

There were no significant cross-lagged regression relationshipsbetween husbands’ positivity and wives’ positivity in the sampleas a whole, but there were significant between-family differencesin the wife 3 husband cross-lagged regression parameter. Thetotal number of conflicts was a significant predictor of thesedifferences such that families with frequent conflicts manifested ahigher degree of positive coupling from wives’ positivity to hus-bands’ positivity. In other words, having relatively frequent con-flicts was associated with a stronger positive association betweenwives’ positivity in one conflict and husbands’ positivity in thenext conflict. That is, for couples with relatively frequent conflicts,husbands’ positivity in one conflict could be predicted from wives’positivity in the preceding conflict. Therefore, because wives’positivity had no continuity (or predictability) across time points,and because for couples with relatively frequent conflicts hus-bands’ positivity could be predicted from wives’ positivity in thepreceding conflict, having relatively frequent conflicts tended toattenuate or diminish the continuity in the husbands’ positivity,thereby offsetting the regularity in the husbands’ positivity.

There were no significant between-family differences in theregressions relating child negativity or agentic behavior to maritalpositivity. Table 2 presents the parameter estimates for the final,best fitting variations of Models 2 and 3, in which only parameterestimates that were statistically significant were retained.

Negativity. We hypothesized that children’s agentic behaviorwould predict decreases in marital negativity, that children’s neg-ativity would predict increases in marital negativity, and thatspouses would influence their own and each others’ marital neg-ativity. Results from fitting Model 3 indicated that children’snegativity during interparental conflict was linked with more neg-ativity between the parents at the end of conflict, but children’sagentic behavior was not associated with less marital negativity atthe end of conflict. Thus, we found support for our hypothesis thatchildren’s negativity was associated with more marital negativity.

Our hypothesis of influence from one conflict to the next waspartially supported for interparental negativity. The intercept of thewife autoregression parameter was significantly different fromzero. That is, when wives reported elevated negativity (i.e., abovetheir own average) at the end of one conflict, they tended to reportlower levels of negativity at the end of the next conflict. Nosignificant between-family differences were found in this param-eter. Although there was no evidence of predictability from onetime point to the next for husbands’ negativity in the sample as awhole, statistically significant between-family differences werefound in this parameter. Significant between-family differenceswere also found in the husband 3 wife cross-regression parame-ter, and marginally significant between-family differences were

observed in the wife 3 husband cross-regression. In addition,between-family differences in the regressions relating child nega-tivity to husbands’ negativity were present at trend level. However,neither the number of conflicts nor marital satisfaction predictedbetween-family differences in any of these parameters. Parameterestimates for the final, best fitting Models 2 and 3, in which onlystatistically significant estimates were retained, are summarized inTable 2.

Conflict resolution. Finally, we tested our hypothesis thatchildren’s agentic behavior would predict increases in maritalconflict resolution, that children’s negativity would predict de-creases in resolution, and that spouses would influence their ownand each others’ resolution. Results from fitting Model 3 indicatedthat children’s negativity during interparental conflict was linkedwith less conflict resolution between the parents at the end ofconflict, and children’s agentic behavior was associated with moreresolution at the end of conflict (see Table 2). Thus, our hypoth-eses regarding children’s negativity and agentic behavior weresupported.

Our hypothesis of marital influence from one conflict to the nextwas not supported for interparental conflict resolution. That is,none of the auto- or cross-regressions were significant. Althoughthe overall wife3 husband cross-regression effect was not statis-tically significant, there were significant between-family differ-ences in this parameter. However, these differences were notpredicted by marital satisfaction or number of conflicts. In addi-tion, there were no significant between-family differences in theregressions relating child negativity or agentic behavior to parents’resolution. Table 2 presents the parameter estimates for the final,best fitting Models 2 and 3, in which only parameter estimates thatwere statistically significant were retained.

Tests using standardized data. Results from model fittingusing the standardized data were largely consistent with thoseobtained using the unstandardized data, with a few minor discrep-ancies. When compared with the results of model fitting with theunstandardized data, there were a few differences for the finalmodels (Model 3). For positivity, children’s agentic behavior didnot predict wives’ positivity, and husbands’ autoregression wassignificant, instead of showing marginal significance (B � �.06,SE � .03, t � �2.20, p � .05). The between-family differences inthe wife 3 husband cross-regression parameter found with theunstandardized data remained significant with the standardizeddata, but the between-family differences in husbands’ autoregres-sion and in the husband 3 wife cross-regression did not, and themarginally significant between-family differences in the regres-sion relating child negativity to husbands’ negativity for the un-standardized data was also nonsignificant with the standardizeddata. For resolution, number of conflicts significantly predictedbetween-family differences in the wife 3 husband cross-regression, whereas it did not predict between-family differencesin the unstandardized data; this coefficient was larger for familieswith more conflicts (B � .07, SE � .03, t � 2.45, p � .05). In sum,several additional within-family parameter estimates were found tobe significant when the standardized data were used, but all thewithin-family estimates that were statistically significant on thebasis of the unstandardized data were still observed to be reliablydifferent from zero when the standardized data were used. Inaddition, some of the significant between-family variance esti-mates obtained with the unstandardized data were no longer sig-

879DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

nificant with the standardized data. Our speculation was thatstandardizing the data reduced idiosyncratic differences in themodel structures, leading to less variability (i.e., standard errors) inthe parameter estimates and, consequently, greater power for de-tecting statistically significant fixed effects and regression param-eters but smaller between-family differences in some of the pa-rameters. We have focused more on discussing results of theunstandardized data because some of these idiosyncratic familydifferences may, in our view, reflect true between-family differ-ences.

Discussion

Children’s Influence on Marital Conflict

Consistent with hypotheses, children’s agentic behavior duringinterparental conflict was linked with better marital conflict end-ings (more positivity, less negativity, more resolution), and chil-dren’s negative emotions and dysregulated behavior during con-flict were associated with worse conflict endings (less positivity,more negativity, less resolution). Thus, these findings provideevidence of children’s influence on marital functioning withinconflict episodes, similar to findings observed longitudinally overthe course of one year (Schermerhorn et al., 2007).

This is a novel finding that adds to the literature on child effectsin important ways. Although theoretical perspectives have sug-gested that children influence marital conflict (Emery & Kitzmann,1995) and empirical work has documented such influence over thecourse of one or two years (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2005), this is thefirst empirical demonstration of children’s influence within maritalconflict episodes. Demonstrating process relations at a microana-lytic level increases confidence in findings based on longer timeframes, by providing evidence of process associations in short aswell as long time frames. Thus, the influence of children on maritalprocesses identified here, reiterated over and over, may contributeto long-term effects. In addition, the modeling tools employed hereyielded information not provided by other analytic approaches. Forexample, the correlational analyses suggested that children’s pres-ence during conflict and agentic behavior and negativity werelargely unrelated to parents’ marital emotions and behaviors, butthe dynamic analyses demonstrated that children’s agentic behav-ior and negativity predict parents’ marital emotions and behaviorfrom conflict to conflict. Furthermore, using diary reports ofconflicts occurring at home lends ecological validity to the find-ings. Thus, these findings suggest child behavior and emotionsshould not be viewed solely as dependent variables in the contextof marital conflict but also as independent variables, predictingsubsequent marital conflict, in a complex pattern of reciprocalrelations.

The conceptual distinction between children’s agentic behaviorand negativity merits further discussion. Agentic behavior involveschildren’s intervention in marital conflict aimed at resolving con-flict, and negativity involves negative emotions and dysregulatedbehaviors during marital conflict. Notably, just as we considerchildren’s agentic behavior intentional, children’s negative behav-iors might also be intentional. That is, children may behave in adysregulated way to distract their parents from an episode ofconflict, in an effort to diminish the conflict. One question forfuture research involves understanding children’s intent. At the

same time, it may be that children’s intent is less important thanthe valence of children’s affect.

Moreover, the implications of these findings for child mentalhealth are substantial. That is, when children engage in agenticbehavior, their parents’ conflicts may become less negative andmore positive over time, but if children engage in negative, dys-regulated behavior, their parents’ conflicts may become morenegative and less positive over time. Previous research has docu-mented an association between destructive marital conflict andsubsequent child mental health problems (for a review, see Cum-mings & Davies, 2002). Thus, if children behave in ways thateventually worsen marital conflict, they may contribute to pro-cesses ultimately with negative implications for their own mentalhealth.

At the same time, previous research also suggests children’sinvolvement in marital conflict may have negative implications forchild adjustment. In studies examining triangulation in parents’conflicts (i.e., inappropriate involvement or enmeshment in par-ents’ conflicts), associations have been reported between triangu-lation and child internalizing and externalizing problems (Franck& Buehler, 2007; Grych, Raynor, & Fosco, 2004). Moreover,children’s helping behavior in the context of depressed interparen-tal interactions might contribute to children’s own dysphoria(Davis, Sheeber, Hops, & Tildesley, 2000). However, agenticefforts by children to resolve interparental conflict are differentfrom triangulation and may contribute positively to the familyenvironment and support children’s well-being (Schermerhorn etal., 2007). Future research should examine the replicability ofassociations between agentic behavior and child outcomes andfurther test for differences between triangulation and agentic be-havior as mediators or moderators of child and interparental out-comes.

Influence of Husbands and Wives Across Conflicts

In addition to assessing children’s influence on conflicts, westudied influences of parents on themselves and on each other at amicrolevel of development. Examining the dynamics betweenhusbands and wives, we found that husbands tended to show morerapid fluctuations in their positivity (but not negativity or conflictresolution) and wives tended to show more rapid fluctuations intheir negativity (but not positivity or conflict resolution) from oneconflict to the next. That is, husbands and wives tended to havevery different behavior and emotions from one time point to thenext and oscillated back and forth around their baseline levels.That is, deviations in the husbands’ positivity and wives’ negativ-ity at one time point could be predicted in a negative directionfrom deviations in their positivity/negativity at the preceding timepoint. This does not mean that the husbands’ negativity andwives’ positivity were unpredictable in a dysfunctional sensebut simply that, for example, an unusually high or low nega-tivity on one occasion did not help indicate husbands’ negativ-ity at the next conflict. Individuals who show consistently highor low positivity (and thus, very little deviation relative to thebaseline), for instance, may manifest no continuity in the formof autoregression weight because of the lack of systematicdeviations that persisted from one conflict to another. Adding toprevious research examining gender differences in marital be-havior (e.g., Christensen & Heavey, 1990), our findings suggest

880 SCHERMERHORN, CHOW, AND CUMMINGS

that parents’ gender may be associated with some differences inmarital positivity and negativity. Such gender differences mayhave either adaptive or maladaptive implications for maritalquality. For example, differences in marital behavior may bepart of the process by which partners regulate their behavior asa couple, recovering from conflict. Alternatively, gender-related differences in marital behavior may result in communi-cation difficulties, if they create a sense of difficulty in under-standing one’s partner.

Marital Satisfaction and Number of Conflicts

We also examined between-family factors that we anticipatedmight help explain differences between families in the maritaldynamics. These analyses build on the correlational analyses,which suggested the marital conflict constructs were associatedwith marital satisfaction and number of conflicts. The results of theprimary analyses were surprising in that marital satisfaction didnot alter marital dynamics. However, the number of conflicts thatoccurred in the 15-day diary report period was associated withdifferences in marital positivity. In particular, the wife3 husbandassociation for marital positivity was stronger for couples whohad more conflicts than for couples who had fewer conflicts.This finding is interesting, because it suggests that for coupleswith more frequent conflict, wives’ positivity in one conflictmay trigger husbands’ positivity in the next, which may be partof the process by which these couples regulate their interac-tions. There may be something about experiencing more fre-quent conflicts that prompts couples to engage in this sort ofself-regulation. This notion is bolstered by the panels of Fig-ure 2, which suggest some consistency in how families whohave a lot of conflicts handle their conflicts. Our results areconsistent with the notion that the more conflict episodes fam-ilies have, the fewer possibilities they have for handling conflict(Cummings & Davies, 1994).

An alternative possibility is that the decrease in variability atgreater numbers of conflict episodes reflects a “practice effect”resulting from increased familiarity with completing the diaries.Another possibility is that couples who have more interspousalregulation of positivity have more frequent, but not necessarilymore intense or destructive, conflicts. Marital satisfaction did notpredict between-family differences in the positive association be-tween wives’ and husbands’ positivity, suggesting that this asso-ciation is not specific to couples with low marital satisfaction.Further research is needed on all of these issues and on theimplications of these relations for development over longer periodsof time.

Moreover, children’s influence on marital conflict endings wasnot isolated or specific to subpopulations. Thus, for the sample asa whole, children’s agentic behavior during conflict predictedmarital positivity and conflict resolution at the end of conflict, andchildren’s negativity during conflict predicted all three maritalconflict endings. This finding builds on preliminary analyses in-dicating no child gender or age differences in any of the primaryconstructs of interest, and it further suggests that children’s be-havior may be such a strong stimulus that it might influencemarital conflict, regardless of between-family differences in mar-ital satisfaction and conflict frequency. That is, findings did notvary by marital satisfaction or by number of conflicts. The findings

of children’s influence on conflict resolution are particularly in-teresting because previous work has documented the importance ofconflict resolution for children (Goeke-Morey et al., 2007), but toour knowledge, this is the first study to show that children alsoinfluence marital conflict resolution.

Children’s presence may be another “child effect,” linked withparents being less likely to engage in conflict with one another. Forexample, Papp et al. (2002) reported that although children werepresent for only about one third of their parents’ conflicts, theconflicts that children were present for were more negative. Thus,although children’s presence may prompt parents to postponeengaging in conflict most of the time, for the most anger-arousingconflicts, parents may be unable or unwilling to postpone theirconflicts.

Limitations and Future Directions

A number of limitations of the study merit discussion. Becauseof missing child data, the potential models that could be examinedwere limited. For example, we did not run models with childagentic behavior and negativity as continuous variables with tri-variate couplings (mother–father–child) because the children werepresent in only a relatively small proportion of the conflicts. Theprimary source of missing child data was interparental conflictsthat the child did not witness, rather than an error in parents’reporting. Examination of whether these findings apply to othersamples and other populations, such as clinical populations, isneeded. The current analyses do not rule out the possibility otherfactors may be important in these family processes. For example,marital conflict intensity and the presence of siblings, who them-selves may well exhibit agentic behavior and/or negativityduring conflicts, may uniquely influence marital conflict.Rather than examining the interplay among marital positivity,negativity, and resolution, in the current study, we focused onone marital construct at a time. However, we do not assume thatthese processes operate independently. For example, positivityin the preceding conflict might influence resolution of thecurrent conflict, and examining these processes concurrentlymight have produced different results. Further, child age andgender and marital conflict topics might moderate associationsbetween children’s behavior and parents’ conflict. Similarly,the proportion or absolute number of conflicts children witnessmight have different implications for family dynamics than thetotal number of conflicts. These are important questions forfuture research.

Caution is needed in interpreting the auto- and cross-regressiveweights, because of the possibility that the dynamic parametersresulted from individuals’ discrepant responses to indicators thatwere intended to measure the same, underlying construct. Further-more, although we used conflict number as the time index in ourmodels to circumvent the need to deal with the irregular timeintervals in the data, the time elapsed between successive conflictsmay play an important role in determining the intensity anddynamics of subsequent conflicts. Thus, continuous-time for-mulations of the VAR models should be explored in futureresearch to accommodate the irregular intervals between con-flicts (e.g., Harvey, 2001; Oud & Jansen, 2000). Alternatively,growth curve models utilizing “time” as an independent vari-able in the mixed-effects formulation may be used, with the

881DEVELOPMENTAL FAMILY PROCESSES

appropriate error structure defined to handle the irregular inter-vals in the data (see, e.g., Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000),although this approach does not allow for random effects in theauto- and cross-regressive parameters, which were of interest inthe current investigation.