DESERT SALTGRASS - Home | MSU Libraries › ?file= › 2000s › 2001 › 010106.pdfpopulation...

Transcript of DESERT SALTGRASS - Home | MSU Libraries › ?file= › 2000s › 2001 › 010106.pdfpopulation...

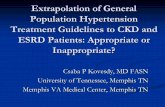

DESERT SALTGRASS:A Potential New Turfgrass SpeciesAlways on the lookout for new types of turfgrass,researchers may have found a promising species.by DAVID M. KOPEC and KEN MARCUM

Saltgrass (Distichlis) plots are being evaluated for turfgrass quality at Colorado State University. Buffalograsses (Buchloe dactyloides)are in the foreground and saltgrass selections are in the background. After many weeks of drought and no irrigation, the colordifferences are dramatic.

TIE PROBLEM of adequate wateravailability and water quality isamong the greatest issues that

turfgrass managers face in the westernUnited States. Increased populationgrowth nationwide, with a shift inpopulation demographics to the south-western United States has forcedpotable and well water use on golfcourses to become stretched to thelimit.

One way golf courses meet thischallenge is to minimize the acreageallotted to turf. In Arizona, all newcourses designed and constructedafter 1985 are 90 acres or less of turf.Still, water costs can be one third ofthe annual operations budget. The useof reclaimed municipal wastewater ispracticed wherever feasible. However,more needs to be done in the entirescheme for water conservation.

6 USGA GREEN SECTION RECORD

Bermudagrass is probably the tough-est all-around turfgrass in the southernUnited States, with low water-userates and fast growth being key assets.Even with its relatively low rate ofwater use, bermudagrass (as a turf ingeneral) is often treated as an environ-mental taboo, especially in desertclimates and other areas that receivelow rainfall. Are there any othergrasses that are water efficient andtolerant of poor quality water that cangrow in the desert? The answer -maybe.

The University of Arizona has beenevaluating an unused native grassspecies for turfgrass adaptation that iscommonly referred to as saltgrass; thegenus is Distichlis. It should not beconfused with alkaligrass, a cool-season species that includes weepingalkaligrass (Puccinellia distans) and

Lemmon alkaligrass (Puccinellia lem-manU). Those grasses are bunch-typegrasses that grow in cooler climates.Distichlis is a warm-season grassthat turns brown" in the winter, likebermudagrass.

There are several species of Distich-lis (saltgrass), but two types predomi-nate. These are coastal saltgrass (Dis-tichlis spicata) and inland or desertsaltgrass (Distich lis stricta). Botanicalliterature often lists conflicting speciesand common names for these grasses.

Distichlis produces robust, scalyunderground rhizomes, found at 4- to10-inch depths in the soil. The growthis somewhat unique, as the rhizometip will grow far away from the motherplant and then emerge at the soil sur-face. From that .point, new verticalshoots "fill in" between the outermostrhizome and the mother plant. In that

At a quick glance, Distichlis can be mistaken for bermudagrass. This warm-seasonnative grass species can be found in a wide array of geographic and climatic zones.

regard, it is very different from otherrhizomatous grasses, such as zoysia-grass, Kentucky bluegrass, or evenbermudagrass.

The leaves of saltgrass and the plantitself show an appearance similar to acoarse bermudagrass. These leavestypically project from the stem at 65°to 75° from horizontal. The stems ofsome ecotypes can be very rigid andstiff to the touch, seemingly weedyenough to "give you splinters."

Unlike bermudagrass, Distichlis canbe found in a wide array of geographicand climatic zones, such as: Yuma andthe Wilcox Playa in the southerndesert of Arizona; the Oregon coast;outside Denver, Colorado; the moun-tains of New Mexico; and Salt LakeCity, Utah. Distichlis also is found onSitting Bull Monument in northernSouth Dakota. Work being done atColorado State University will helpdefine the relationships betweenchromosome counts and geographiclocations to see if different genotypesexist (as in buffalograss). This infor-mation will improve our understand-ing of the grass and expedite develop-ment of improved turf types.

So why would anyone bother in-vestigating this species for potentialuse as a turfgrass? Because Distichliswill grow in very harsh soil conditions,endures extended drought, thrives insalty soil, and tolerates high-salt-con-tent water.

Salinity-tolerance field trials wereconducted at the University of Arizonagreenhouse testing facilities, compar-ing all the Distichlis genotypes to astandard of Midiron bermudagrass.The highest salinity level tested was60,000 ppm NaCI. For comparison,full-strength seawater is about 35,000ppm. Figure 1 shows significant varia-bility in the percentage of green leafcanopies of five saltgrass entries vs.Midiron bermudagrass. Midiron wasessentially dead at 36,000 ppm. Somesaltgrass entries were still mostly greenat 60,000 ppm (e.g., A-55), but othersdid not perform as well (e.g., C-11).This illustrates not only the tremen-dous salinity tolerance of this species,but also the genetic diversity present -a positive factor for turf breeders indeveloping this species into a usefulturfgrass.

Separating the Men from the BoysIn November of 1995, the Univer-

sity of Arizona embarked on a Dis-tichlis "hunting trip" into Colorado.Hundreds of plants were collected

from roadsides, an abandoned militaryair base, and old lawns. The collectionwas narrowed down to 100 plants(individual genotypes) based on theirability to propagate readily. Each ofthese 100 genotypes was cut into fourpieces to make identical copies. Fourhundred plants were then mowedwith hand clippers at 1.75 inches threetimes a week for four months.

Plants that could tolerate the mow-ing stress filled up the pots almostcompletely and had high shoot den-sities and short leaf internodes (leavesare close together on the stem). Thus,mowing pressure demonstrated that(1) there was genetic variation ingrowth habit among the differentplants collected and (2) the desirableturf-type growth habit was present inabout 10% of the population. The testwas repeated again a year later withthe same plants emerging as "winners"in both tests.

Fourteen of the plants screened atthe University of Arizona, along withseven from Colorado State University,have been planted as field plots. Turfswere established by placing threeplants in the ground in 4 foot by 6 footplots in August of 1998. Plywoodframes were installed to providesidewalls 24 inches deep in the soil.The frames were necessary to avoidplots from growing into one anotherdue to the aggressive rhizome forma-tion. Plots were mowed two to threetimes per week with a rotary mower at2.0 inches.

In 1999, the turf received two springflood irrigations. In 2000, the weatherwas extremely hot and dry, with lessthan 1.25 inches of rain from

November 1999 to April 2000. Still,despite this minute amount of totalwater, most of the 21 entries greenedup and held color. The plots wereagain flood-irrigated on April 11 andon May 13, 2000. Salt blocks (50 lb.animal-grade salt licks) were added tothe irrigation plumes to add somestress and to help eliminate any sur-face weeds in the alleyways. Many ofthe Distichlis genotypes maintainedgreen color from May 13 to June 15under scorching temperatures of morethan 100°F and arid, sunny conditions.In contrast, bermudagrass would lastabout a week under those conditions.From June 15 to September 1, the sitereceived about 1.25 inches from fivesmall rain events. The Distichlis didnot receive any additional irrigationduring that time. Under these types offield conditions we want to identifystress-hardy types that have an accept-able turf-type growth habit.

There are about five or six geno-types (single plant selections) thatqualify as acceptable turf types. Theseplants have filled in the plots, main-tained green color, have a high shootdensity, and have stems with tips thatare not sharp, mowed-off culms.Rather, there is a true leaf that unfurlsfrom the stem, making for the best turftypes.

Although not yet measured in tests,Distichlis also seems to adapt to trafficand compaction better than otherwarm-season grasses. Distichlis hasbeen found growing on highly com-pacted sites, such as gravel roadwaysat truckstops and unpaved parkinglots in Arizona and New Mexico. It re-mains to be seen how different selec-

JANUARYIFEBRUARY 2001 7

tions, with different growth habits,respond to different kinds of com-paction.

Since Distichlis is found in salty anddroughty conditions where basicallyno other grasses gro\v, it probably isnot a grass for areas that receive asignificant amount of rainfall. How-ever, geographical findings do supportits existence from the low deserts tothe high mountain areas. Casual ob-servations of its many good charac-teristics warrant further investigation.

,100

o 12 a'&24' 36,'S~.linity ;(ppm >< 1000)

It would be nice to have a grass thatcould go three to four weeks betweenirrigations, or even two weeks underheavy traffic. Distichlis may fit the bill.

What is in the Future?Currently, the best turf types would

be suitable for roughs, which aregrowing smaller in acreage on newgolf courses due to water-use restric-tions. No fairway types have beenidentified yet; however, two of the 21entries in the existing test may tolerate

closer mowing, perhaps to 7/8 inch.Further testing will be necessary.

As with any other new species,commercial propagation will be animportant issue to resolve. Distichlishas some genetic limitations for seedproduction, but information from thestudies at Colorado State Universitymay help shed new knowledge on thissubject. If not, then vegetative optionswill be investigated. Distichlis growsmore slowly than bermudagrass, butmore quickly than zoysiagrass. Itsleeps, creeps, and then leaps, similarto buffalograss, when established byplugs. We have screened and main-tained our selections under continu-ous mowing stress and devoid of waterand fertilizer as much as possible. Weare optimistic that Distichlis will be atough grass for tough times. It takes along time to develop a species into anew turfgrass, but Distichlis hasshown the potential to be worth con-siderable effort.

Do you have any Distichlis on yourgolf course? If so, we would like tocollect a sample. Contact Dr. DavidKopec at [email protected], orcall (520) 318-7142.

DR. DAVID M. KOPEC is the TurfgrassExtension Specialist at the University ofArizona in Tucson.DR. KENNETH B. MARCUM is theAssistant Professor of Turfgrass Manage-ment at the University of Arizona inTucson. His specialty is environmentalstress of turfgrass management.

One hundred genotypes of Distichlis were clipped in pots to simulate mowing stress.Plants that could tolerate the mowing stress filled the pots almost completely.

8 USGA GREEN SECTION RECORD