Desert operations. - Digital Collections · 4 Figure 5.-—Escarpment in Western Desert, Egypt sent...

Transcript of Desert operations. - Digital Collections · 4 Figure 5.-—Escarpment in Western Desert, Egypt sent...

—l marmmnmFM 31-25

WAR DEPARTMENT

BASIC FIELD MANUAL

DESERT OPERATIONSMarch 14,1942

fmsi-25

BASIC FIELD MANUAL

DESERT OPERATIONS

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICEWASHINGTON ; 1942

TI

WAR DEPARTMENT.Washington,March 14, 1942.

FM 31-25, Desert Operations, is published for the informa-tion and guidance of all concerned. Its provisions should bestudied in conjunction with FM 100-5.

[A. G. 062.11 (2-14-42).J

order of the Secretary of War :

G. C. MARSHALL,Chief of Staff.

Official :

J. A. ULIO,Major General,

The Adjutant General.Distribution :

B and H (6); R and L (3); IC 17 (5).(For explanation of symbols see FM 21-6.)

TABLE OP CONTENTSParagraphs Page

Section I. General 1-13 1II. Food, clothing, and individual equip-

ment 14-18 12HI. Transportation 19-26 16IV. Movement 27-38 22V. Camps and bivouacs 39-44 26

VI. Reconnaissance and security. 45-50 29VII. Combat 51-59 32VIII. Arms and services 60-73 34

IX. Camouflage and concealment 74-76 45X. Supply 77-86 46

Appendix I. Motor transport 50II. Distant ground reconnaissance 52

III. Organization _! 58

IV. Sanitation and first aid 59V. Supply 61

Index 67

1

FM 31-25RESTRICTED

BASIC FIELD MANUALDESERT OPERATIONS

Section I

GENERAL

■ 1. General.—a. In desert warfare certain general condi-tions will be encountered which will profoundly affect mili-tary operations. Special equipment, special training andconditioning, and a high degree of self-discipline are essen-tial to successful desert operations.

b. This manual has been compiled from a study of MIDreports, interviews with observers, and all other sources ofinformation available at the time of preparation. It is nota complete treatment of the subject of desert warfare sincenone of our troops have, up to the present, had experiencein desert operations. It is intended to suggest the more im-portant factors and conditions which must be consideredin preparation for operations in the desert. The basic tacti-cal doctrine set forth in FM 100-5 is applicable to the con-duct of operations in all types of terrain. While the in-formation included in this manual is based primarily on theexperience in the Western Desert in Africa, it is believed thatit is applicable generally to all deserts.

■ 2. Characteristics of Deserts (figs. 1 to 4, inch).—Alldeserts, regardless of latitude, have certain characteristicsin common—lack of water, absence of vegetation, large areasof sand, extreme temperature ranges, and brilliant sunlight.The terrain in deserts is not necessarily flat and level.There are hills and valleys, mountains and sand dunes, rocks,shale, and salt marshes, as well as great expanses of sand.Erosion in rocky areas produces effects similar to the rim-rock in some of our Middle Western States. These may pre-

2

Figure 1.—Trans-Jordan Desert.

Figure 2.—Trans-Jordan Desert camp.

BASIC FIELD MANUAL2

3

Figure 3, —Egypt, Western Desert.

Figure 4.—Libyan Desert.

2DESERT OPERATIONS

4

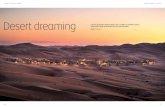

Figure 5.-—Escarpment in Western Desert, Egypt

sent obstacles which are impassable to vehicles of any sort;the escarpment near the seacoast in Egypt and Libya, severalhundred feet high at points, is such an obstacle. (See fig. 5.)

B 3. Travel in Desert.—There are few roads and trails inthe desert. Those that exist connect villages and oases.Travel is not, however, confined to roads and trails but isusually possible in any general direction. The types of ter-rain vary and present only local difficulties to movement. Inthe Sahara are found sand dunes, sand hillocks, stretches ofdeep, soft sand, rock-strewn areas, and salt marshes. Allare passable for a man on foot and for the domesticatedanimals of the region—camels, horses, and donkeys.Wheeled vehicles have traversed all parts of the African des-ert and track-laying vehicles have been used in many areas.■ 4. Sand Dunes (figs. 6 and 7).—a. These are great ridgesof deep, soft sand. In the Sahara they are found particu-larly in the Sand Sea. Dunes usually stretch along roughly

2-4 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

5446597°—42 2

Figure 6.—Sand dunes in Western Desert, Egypt.

parallel to the direction of the prevailing winds. Sincemany dunes are so high and steep that they must be detoured,a route through an area of sand dunes is long and tortuous.There are few “shifting” dunes of soft sand in Africa—-almost none in the Sand Sea. The surface of a sand duneis usually packed by the wind to a depth of about 2 inches.This wind-packed crust will support considerable distributedweight normal to its surface, but since the sand grains havelittle mutual cohesion the crust will break under driving orbraking thrust.

b. Successful vehicle operation in sand dunes is possiblewith proper equipment if drivers are given sufficient train-ing. The fundamental governing successful driving in thisterrain is to reduce unit pressure and driving thrust to aminimum. Tires should be oversize and operated at lowpressure. They should have a smooth tread. (See par. 22.)Snow or other corrugated treads will bite into the crust,break it, and dig into the soft sand underneath. Experienceddrivers, given suitable training, will develop an eye for the

4DESERT OPERATIONS

6

Figure 7.—Sand dune in Sand Sea.

ground. Such drivers, by intelligent use of momentum, care-ful pre-selection of gears, and gradual application of throttleand of brakes will be able to traverse sand dune areas.Large dunes must be detoured and the smaller ones rushed.Each vehicle must avoid the tracks of preceding ones. Softspots are frequent but can be avoided. Frequently a recon-naissance on foot will be necessary. Difficult as such drivingis, daily mileages of 100 to 150 miles during daylight havebeen made over extended periods of time by experienceddrivers with fully loaded, 4x2, trucks.

c. Up to the present, track-laying vehicles have not beenused in military operations in sand dunes. It is believedthat such vehicles, up to about 13 tons in weight, equipped toshift gears easily at speed, should be able to negotiate thistype of terrain after drivers have been carefully trained.■ 5. Sand Hillocks.—In parts of the desert, shrubs haveserved as windbreaks for wind-borne sand, causing the sandto build mounds about the base of the shrubs. These moundsare from a few inches to several feet in height and areusually so spaced that motor travel through such an area

4-5 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

7

is difficult or impossible, particularly for heavy supply col-umns. Areas of sand hillocks vary from a few acres to manymiles in extent. If such areas cannot be detoured, suitabletrails may be made with a road grader, bulldozer, or heavydrag towed behind a tractor or truck. Several miles ofpassable road can be made per hour by this method.

■ 6. Deep Sand (figs. 8 and 9).—Stretches of deep, softsand may be encountered anywhere in the desert. Theyare particularly prevalent in areas where there has beenmuch travel. The sand is seldom deep enough to preventthe passage of either wheeled or track-laying vehicles, al-though wheeled vehicles may frequently get stuck. (Seepar. 25.)

■ 7. Boulder-Strewn Areas (fig. 10).—There are many milesof such areas in the African deserts. The boulders are lime-stone, sandstone, or volcanic rock. These rocks are usuallynot large but are hard and sharp and are so numerous thatit is impossible to avoid any but the largest. Such areasmay be traversed by all types of military vehicles, but ex-

Figure 8.—Pebbly desert and soft sand, Libyan Desert.

5-7DESERT OPERATIONS

7 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

8

Figure 9.—Rocks, soft sand, and limestone, Libyan Desert.

Figure 10.—Boulder-strewn terrain, Libyan Desert.

9

cessive tire wear and track and spring breakage, as well asunusual wear and tear on vehicles due to jolting, must beexpected.

■ 8. Salt Marshes (fig. 11).—These are usually dry lake ox-stream beds and may be encountered along the coast orinland in depressions. They are generally impassable whenmoist. When dry they may be traversed by light vehicles ifthe surface is sandy and the route is reconnoitered on foot.When the surface is predominantly powdery silt, they ax-eimpassable. Roads may be made across dry silt beds byrolling or packing the silt after it is moistened with brackishor salt water as a binder, or by sand fill. Except under un-usual conditions salt marshes should be detoured.

■ 9. Water.—a. Adequate water supply is the problem whichdominates all others in desert operations. Excessive heatand lack of moisture in the atmosphere increase water con-sumption in an area in which water is almost nonexistent.In the Sahara there are no rivers or stagnant bodies ofwater. Except close to the seacoast, subsoil water is rarely

Figure 11.—Salt marsh in Western Desert, Egypt.

7-9DESERT OPERATIONS

10

present. The water in existing oases is scanty, usually in-fected, mostly filthy, and at best disagreeable to the taste.Troop operation is dependent on the water-carrying capacityof organic or specially allotted equipment, the training anddiscipline of the personnel in water consumption, and thepossibility of replenishment of water supplies from baseswhere an adequate quantity is available. (See par. 16.)

b. Troops from a temperate climate must be speciallyconditioned for desert operations. They require a sufficientperiod of training to accustom themselves to the heat and todevelop the ability to get along on a minimum quantity ofwater. High temperatures are normal in the desert andthe loss of body moisture through perspiration is high.■ 10. Temperature.—The daily temperature range in thedesert is excessive during all seasons. The average tempera-ture in the hottest part of the day is well over 100° P. In thesummer season the maximum temperature is so great (120°to 130° F. in the shade) that it makes very difficult extendedoperations by large bodies of troops. The daily temperaturevariation is so great, even during this season, that overcoatsor heavy sweaters and blankets are often required at night.Specially trained and equipped small patrols can operatefreely over wide areas during any period. The winter season,roughly November to March, inclusive, in the Libyan Desert,is the best period for large scale military operations. Nightsare cold during this period, the temperature oftentimes drop-ping below the freezing point. Warm clothing and three tofive blankets per man should be provided for the troops (seepar. 18).

■ 11. Wind.—Wind conditions vary in the desert as in otherterrain. In the Libyan Desert light breezes, usually fromthe north or west, are common during the day and aftersunset. Storms of hurricane velocity are not infrequentduring the day and night throughout the year. Such stormscarry large quantities of dust and sand and are frequentlyaccompanied by rapid changes in temperature—a suddendrop in the winter, a painful rise in the summer. Observa-tion and movement may be extremely difficult during a heavysandstorm.■ 12. Visibility.—a. Despite the lack of concealment, theclear skies, and the vast, relatively flat and featureless

9-12 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

11

stretches of ground, visibility as it affects terrestrial observa-tion is not usually good in the desert.

b. The position of the sun has considerable effect on obser-vation. When the sun is behind an observer he sees objectsplainly, without shawodw, whereas an observer looking in theopposite direction is not only handicapped by the glare ofthe sun itself and its reflection from the ground, but sees allobjects in shadow. In the early morning observation is bet-ter from east to west than from west to east. At midday itis much more difficult to observe into the sun, that is, to thesouth, than away from it. In the afternoon and evening theobserver looking from west to east has the best observation.During winter, when the sun is lower on the horizon through-out the day than it is in summer, these effects are accentu-ated. Forces now operating in the desert have timed theirattacks, whenever possible, so as to have the sun at theirbacks.

c. Visibility is so poor during dust storms that air obser-vation of ground forces is impossible, and terrestial observa-tion is greatly reduced, sometimes to less than 100 yards.These storms, when they were not too heavy, have been usedto facilitate surprise in carrying out approach marches overpreviously reconnoitered routes, in making surprise attackson lines of communication and supply installations, and inraids by small groups on defensive positions. They havenot been used to gain surprise for large scale attacks becausethey make control and maneuver extremely difficult andrender close artillery or air support impossible.

d. Mirage has an adverse effect on visibility and groundobservation. It is most frequent in the summer, but it isvery difficult to determine under what conditions it willoccur and what form it will take. Mirage is seen by an ob-server who is facing the sun. It is evident on a wide arcwhich increases as the sun becomes higher in the sky, both ac-cording to the season of the year and the hour of the day.Its effect generally is to magnify objects, particularly thevertical dimension. It makes recognition of vehicles verydifficult. Under certain circumstances it may give protectionfrom view at distances as close as 500 yards.

e. Wind, through its effect on dust or smoke, whether cre-ated by vehicles or shell fire, will affect visibility. Vehicles

12DESERT OPERATIONS

12

attacking down wind risk being blinded by their own dust.When withdrawing from action, movement into the wind,when possible, affords concealment by the dust created. Anattack supported by artillery should not be made from thedirection into which the dust is being blown. A movementconcealed from hostile observers by an intervening crest maybe disclosed by the dust raised, even when the vehicles can-not be seen.

/. Moonlight is normally very bright in the desert. Troopmovements at night, except during the dark of the moon orduring dust storms, are readily observed by both ground andair observers. During the dark of the moon, night observa-tion is impossible without the use of flares.

■ 13. Vegetation.—There is almost a complete lack of vege-tation in deserts. Some growth, usually palms, will befound at oases, and in certain areas thorn trees and smalltufts of grass grow. In general there will be no naturalgrowth for shade, shelter, or concealment from observation.In addition to the discomfort caused by the lack of protec-tion usually afforded by natural growths, there is a psy-chological reaction in individuals who are accustomed tomore normal terrain. This reaction produces a feeling ofnakedness, exposure to all observation, which, in many in-dividuals, results in undue apprehension of the dangers ofenemy action. Troops will require a period of time to over-come this feeling.

Section IIFOOD, CLOTHING, AND INDIVIDUAL EQUIPMENT

■ 14. Food.— a. No dependence can be placed on localsources for the supply of food for troops engaged in desertoperations. Even small long-distance patrols should be sup-plied with sufficient food to cover the period of their oper-ations as no assurance can be had that any food can beobtained at oases.

b. Normal field and emergency rations are suitable forthe nourishment of troops in the desert. However, consider-ation must be given to the fact that it will usually be im-possible to conduct unit messes in the field, hence cook-ing will have to be done by individuals and small units,

12-14 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

13446597°- 42 3

usually the occupants of one vehicle. Rations should be sopacked that they can readily be broken down for issue toindividuals and small groups. They should be of a typethat enables individual preparation with a minimum amountof water. This indicates the necessity for a high proportionof canned goods.

■ 15. Cooking.—a. Unit messing will be impossible, exceptin rear areas, and then only when the threat of low-flyingor dive-bombing air attacks is neglible. Under normalconditions meals must he prepared by individuals and smallunits. Every vehicle should be equipped with a small stove,using gasoline or canned heat as fuel, adequate for the prepa-ration of the food for the personnel transported in thevehicle.

h. When food is prepared in a unit mess, care should betaken to use salt sparingly, and the use of condiments whichinduce thirst should be avoided. Pood prepared by smallunits should be limited to articles which can be heated incans as the water used in cooking must come from the indi-vidual water rations. Water used for heating cans of foodcan then be used in the preparation, of hot beverages.

■ 16. Water.—a. The importance of water cannot be over-emphasized in desert operations. In training troops it mustbe made clear to each individual the vital part which watersupply will play in the success of the operations. Restrictedwater consumption must become a habit. Training mustcondition troops to live on a limited water ration and mustdevelop such self-discipline in the use of water as will assurethe maintenance of combat efficiency on the limited watersupply available. Rapid drinking during the day must beavoided as nearly all the water thus consumed is quicklythrown off in excessive perspiration and thus wasted. Thefirst cravings for water are lessened by moistening the mouthand throat. Small sips from the canteen will accomplishthis. All issues of water to individuals should be made bynoncommissioned officers upon the order of an officer; andno water should be taken from water supply cans exceptunder supervision at regular issue periods.

b. Troops must become accustomed to drinking water inwhich salt has been dissolved. Many of the sources of water

14-16DESERT OPERATIONS

14

supply in the desert furnish water with a relatively highdegree of salinity. The addition of salt to water will alsohelp make up for the high loss of body salts caused by ex-cessive perspiration. Salt tablets should be issued for thispurpose when possible. Hot sugared tea has been found tobe beneficial for troops in the desert and reduces thirst.Smoking, particularly during the day, increases the desirefor water and must be avoided.

c. It has been found in the Western Desert in Africa thata ration of IVS U. S. gallons of water per man per daywill be sufficient for extended operations by trained troops.(See par 9.) This ration is for all purposes: drinking, cook-ing, washing, shaving, and brushing teeth. Troops on thisration cannot bathe but are limited to an occasional damprubdown. The minimum ration for the above purposes isthree-quarters U. S. gallon per man per day; however, indi-vidual efficiency will start to decrease after about 3 dayson this minimum ration. In an emergency, men conditionedto desert conditions can operate for as long as 5 days ona quart of water per man per day, if traveling is done atnight and they can find shade during daylight hours. Onsuch a ration combat efficiency will be seriously lowered.■ 17. Receptacles for Water and Food.—a. The water andfood rations for all of the occupants of a vehicle should becarried on the vehicle. Water is best carried in tins of from2- to 4-gallon capacity. Larger capacity tins involve therisk of a loss of all water in the event of a leak. The watercontainer should be provided with a screw top, fastened tothe can by a chain. A rubber washer should be used with thistop, as leather washers will foul the water. To prevent rust-ing, water cans should be galvanized or have an interiorcoating of paraffin wax with a high melting point. Everyvehicle should be provided with at least one funnel to preventwastage in issuing water rations.

b. If possible, vehicular racks should be provided for waterand ration containers. These should be readily accessibleto permit rapid unloading in the event the vehicle must beabandoned. When such racks are not built on the vehicle,wooden cases must be provided to protect water cans andrations. No case should contain more than two water cans

16-17 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

15

or 1 day’s rations for the occupants of the vehicle. A specialsoldering iron is necessary for repairing leaks in water cans.Water containers should be so loaded that they are easilyinspected for leakage. A large fixed tank is unsuitablefor carrying water rations. To the danger of loss of all waterin the event of an injury to the container is added the diffi-culty of locating and repairing leaks and of removing thecollection of sludge and other deposits that rapidly accumu-late in the bottom. In addition, the tank does not lend itselfto rapid removal of the water from the vehicle which willoften be necessary in emergencies.

■ 18. Clothing.—a. The present authorized clothing, bothsummer and winter, is suitable for desert operations. Con-sideration should be given to providing special uniform forsummer use. Both British and German troops now operat-ing in the desert are equipped with a special tropical uniformfor summer wear. The principal characteristics are the light-weight material, open-neckedshort-sleeved shirts, shorts, anda wool half stocking. This uniform allows a free circulationof air around the body, has no ill effects on the health oftroops, and does not result in excessive sunburn; the troopslike it, and the British Medical Service approves of it. Itdoes expose large areas to attack by sand flies. Because of thewide temperature range and the cool nights some sort ofwoolen garment is needed for wear at night during the hotseason. Woolen uniforms and some type of overcoat arenecessary for winter operations in the desert, as during thisperiod the weather is generally cold, raw, and disagreeable.A woolen band should be worn over the stomach, particularlyin the summer, to prevent stomach chills. The hotter theday the more necessary is this protection.

b. Various types of headgear for wear when not in combatare being used by desert troops at the present time. All havetwo necessary characteristics; provision of air space and ashield for the eyes. Sun helmets afford excellent protectionduring the summer season but deteriorate rapidly becauseof hard use. Hats similar to the campaign hat are used bysome troops and afford excellent protection against the sun.Many individuals wear a garrison cap which provides suffi-cient air space and shields the eyes. The field cap, lacking

17-18DESERT OPERATIONS

16

air space and visor, is unsuitable for desert wear. The steelhelmet is worn during combat.

c. Special individual equipment which will add to comfortand efficiency are goggles, respirators, sun glasses, neck cloth,nose cloth, and fly switches. Goggles and dust respiratorsare a necessity for all vehicle drivers, and will add to theindividual comfort of others, particularly during sandstorms.Good sun glasses are most desirable for all individuals andmust be provided for antiaircraft and antitank gun crewsand lookouts. The Arabs, as a result of centuries of desertlife, wear a cloth to protect the back of the neck from thesun’s rays and a cloth over the nose to protect the lungsfrom sand and dust during storms. Such cloths are notused by troops now operating in the African desert. Theyshould be considered in equipping troops for desert opera-tions. Sand flies are an always prevalent pest in the desertand undue exposure to them frequently results in sand flyfever. The use of horse-tail fly switches is almost universalamong British desert forces.

Section 111

TRANSPORTATION

■ 19. General.—Movement of troops on foot over any con-siderable distance is not practicable for military operationsin the desert. The great distances involved, the lack of con-cealment, the difficult ground surfaces, and the excessive wa-ter consumption produced by the exertion of marching limitmovement on foot to that which is necessary for close com-bat. Every type of military vehicle, with the exception ofmotorcycles, can be employed for operations in the desertwhen modified for use in such terrain. The rough groundsurfaces, sand, and extreme heat make motorcycles uselessfor combat purposes. Many of the difficulties which will beencountered can be overcome by foresight and careful train-ing. Certain modifications should be made and specialequipment provided for the present authorized military ve-hicles when they are to be used in desert operations. Thechanges necessary to overcome the unusual conditions whichwill be encountered are discussed in the succeeding para-graphs.

18-19 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

17

■ 20. Cooling Systems.—a. Because of the difficulty of wa-ter supply, all water-cooled vehicles should be equipped withcondensers in order to prevent wastage and reduce con-sumption. While some water is lost by evaporation, most islost by being splashed up and driven through the overflowpipe by steam. The use of condensers will prevent this.

b. The drainage cock of the cooling system should bereplaced with a screw cap, flush with the end of the pipe.It will seldom be necessary to drain the radiator, and thereis serious danger of the drainage cock being knocked offby stones thrown up by the wheels and all the water beinglost, a real calamity in the desert.

■ 21. Air Filters.—a. There is always some sand in the airin the desert, more is stirred up by the passage of vehicles,and during a sandstorm the amount may be such as toprohibit movement. Without adequate protective measuresthe sand will choke carburetors, plug feed lines, score thecylinders, damage the distributor, and increase the wear onall bearings. The oil bath air filter now standard on allmilitary motor vehicles will protect the motor if it is keptclean. Constant, close supervision and daily inspection ofair filters are the only ways of insuring that sand will notget into the motor.

b. The crankcase breather opening should be equippedwith an effective air cleaner. Air cleaners should also beprovided for any other device using an air intake, such asa vacuum booster or engine-driven compressor. Air cleanersshould be located where the air stream will have the leastdirt pollution.

■ 22. Tires.—a. Operations in the desert will require move-ment over all types of terrain discussed in section I. Tiresmust be suitable for every type of surface which will beencountered. Most difficulty will be met in sand. Experi-ence in the desert indicates that oversize balloon sand tiresare necessary for all wheeled vehicles. The tread should beof plain rib and the tire of round cross section, as a tirewith deeply corrugated tread (snow tread, for example) orwith a raised flat tread will break through the crust and digin the soft sand beneath, thus stopping the vehicle andrequiring it to be dug out (see par. 26). Air pressure must

20-22DESERT OPERATIONS

18

be varied to suit the type of ground surface. Over sandor soft powdered clay, the ground pressure per square inchshould be reduced to the minimum. By deflating the tiresthe area in contact with the ground is increased and thetire fits itself to the irregularities of the sand without break-ing through the crust. The minimum pressure must be de-termined by test for each type of vehicle. Tires on flat-baserims will spin on the rims if pressure is too low. It hasbeen found that tire life is very little shortened by runningsoft over sandy ground which does not contain rocks orimbedded boulders.

b. In rocky or boulder-strewn ground, tires must be asfully inflated as the age and condition of the vehicle permit.It must be remembered that fully inflated tires will result inan increase in the shock transmitted to the vehicle and itsload when moving over rough or rocky ground. At low pres-sure the innermost layers of canvas will be broken by theviolent inward bending when a sharp rock is struck. (Seepar. 7.) The resulting chafing will wear out the inner tubeeven though no danger is apparent from the outside of thetire. Since a normal day’s march will take a vehicle overdifferent kinds of ground, strict tire discipline is necessary.A high percentage of vehicles should be equipped with motor-driven air pumps to insure rapid adjustment of tire pressures.

c. Many vehicles and weapons mounted on pneumatic tireshave been lost in recent desert operations due to their inabilityto move rapidly on tires punctured by bullets. The so-called“run-flat” tire, made with a heavy side wall, an inner rimcushion, and a special tube, which will not collapse whenpunctured, should be provided for use on all wheeled combatvehicles and pneumatic-tired weapons. It must be remem-bered that these tires are not designed to run flat except inemergency and their life when so used is only about 80 to100 miles. Whenever a run-flat tire is punctured, if thetactical situation does not require the vehicle to continue,the tire should be changed and repaired before it is usedagain.

d. As a result of many trials, both by military forces in thedesert and by commercial companies operating there, it isbelieved that a dual tire is unsuitable for desert travel. Theopposing lateral forces exerted by the two tires breaks the

22 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

19

crust on sand, soft sand piles up in front of the tires, exces-sive driving thrust is exerted, and the vehicle is stalled.When the vehicle is stalled in this manner it must be dug out.

e. The life of tires, as of all rubber, will be short at bestdue to the heat, sand, and rough ground surfaces. Provisionmust be made for tire replacements greatly in excess of ex-pectations for normal terrain. It must also be rememberedthat tires will deteriorate very rapidly in storage in thedesert and special covered, ventilated, storage facilitiesshould be provided when possible. Latex-filled puncture-proof tubes in storage must be frequently turned to preventthe accumulation of the latex at one point and the conse-quent unbalancing and weakening of the tube.

■ 23. Spare Parts.—The heat, sand, and rough ground sur-faces all combine to shorten the life of motor vehicles andincrease the need of spare parts. Parts of all kinds must bereadily available in quantities greater than are planned foroperations in normal terrain. Standardization of vehicles isparticularly important due to difficulties of transportationand storage facilities, as well as the high replacement per-centage. Cracked blocks due to overheating will occur muchmore frequently than is to be expected under more normalconditions. The following parts have been found particu-larly necessary by past experience;

a. Rear axles and axle bearings.b. Spring shackles, shackle bolts, complete sets of front

and rear springs, and spare leaves.c. Water pump and gasket, fan belt, water hose, and

clamps.d. Distributor parts, condensers, brushes, spark plugs,

wire, clamps, and tape.e. Wheel and tire lug nuts, plugs for oil drainage fittings,

spare caps for gas tank, radiator, and storage batteries.f. Extra speedometer and cables for all vehicles which

may be called upon to function alone, that is, scout carsand other reconnaissance vehicles.

Note.—Odometer readings are a vital part of desert navigation.

g. Windshields (frequently so damaged by sandstorms asto be useless).

h. Carburetors and fuel pumps.

22-23DESERT OPERATIONS

20

■ 24. Maintenance.—Maintenance as prescribed in presentmanuals will keep vehicles in condition to operate in thedesert. (See PM 25-10.) The importance of maintenancemust be impressed on all concerned, with special emphasisplaced on first and second echelon maintenance. Super-vision will be difficult under combat conditions, as vehiclescannot be brought close together for inspections or otherchecks. (See par. 28.) Break-downs on a march, particu-larly of patrols or other small units, may result in the lossof all the occupants as well as the vehicle itself. The im-portance of driver maintenance must be impressed on everymember of a unit. The excessive jolting makes it necessaryto tighten frequently all body bolts and nuts. Driversmust be trained to make this a regular part of their dailyroutine.■ 25. Special Equipment.—a. Every wheeled vehicle mustbe provided with the equipment necessary to extricate itfrom soft sand. Driving wheels must be given a firm sur-face. For vehicles with single tires on driving wheels anexcellent solution is the provision of a pair of steel chan-nels 4 or 5 feet long, carried on the sides of the vehiclebody. In cross section the channel should have a curvedbottom wide enough to take the whole width of the tire atlow pressure. It should be bent up sharply at the sides toprevent the tires running off, and then down again toform a rounded flange on each side to strengthen the chan-nel. Two angle irons projecting from the underside andholes punched in the bottom will prevent the channel fromslipping under driving thrust. Mats should be provided toform a roadway for front wheels. Canvas strips, stiffenedby lateral rungs of steel sewn between two thicknesses ofcanvas, have been found excellent for this purpose. Suchmats can be rolled up for transport and rolled out in frontof each front wheel when needed.

b. Lightweight and mediumweight dual-tired vehicles maybe provided with a single round wooden spar instead of chan-nels. The spar should be placed between the tires and usedas a rail. Heavy dual-tired vehicles should be provided witha pair of double channels similar to those provided for single-tired vehicles. Dual-tired vehicles will be stuck in sandmuch more frequently than single-tired vehicles. (Seepar. 22.)

24-25 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

446597° —42 4

c. All vehicles should be equipped with at least two short-handled shovels for digging out of soft sand. Tow hooks andtow cables should be provided for every vehicle. Power-drivenwinches to extricate stalled vehicles will be of great value intraversing bad stretches of desert.■ 26. Driver Training.—Practice in driving through stretchesof soft sand and among sand dunes is necessary for all vehicleoperators. Desert driving calls for the highest skill on thepart of the driver, since the necessity for dispersion and foravoiding the tracks of a preceding vehicle require a high de-gree of individual effort. It will take a great deal of experienceto develop the quick eye necessary to select the best groundand the proper gear, the skill required to make maximum useof momentum and to shift gears rapidly, and the care to avoidsudden driving or braking thrust. Even with the most skilleddriving, vehicles will frequently be stuck in the sand. Thefollowing points must be firmly impressed on every driver byrepetition in training:

a. The driver must be taught to give up all efforts to get outof the sand by means of his motor the instant the vehicle hasbroken through the crust and ceased to move. Otherwise,the driving wheels will merely sink deeper into the sand andextrication will be made more difficult.

b. The driver, vehicle commander, or one of the crew mustreconnoiter the ground both ahead and to the flanks for thenearest patch of firm surface. While this is being done thechannels, mats, and shovels should be unloaded. Based oncareful reconnaissance, a decision must be made whether togo ahead or to back out.

c. Adequate excavations must be made in front (or, if back-ing out, in rear) of the wheels so that the near ends of thechannels or mats are on a level with the bottom of the tiretread, and so that the slope of the channels is not too steep.If this is not done the motor will be unable to set the vehicle inmotion up the initial slope to enable the wheels to begin todrive against the firm surface of the extricating equipment.Once in motion, the vehicle should be driven to firm ground orstopped headed down a slope to avoid getting stuck again afterthe channels have been loaded on.

d. To avoid breaking through the crust when starting, ve-hicles should always halt, when possible, on hard ground orheaded down a slope.

25-26DESERT OPERATIONS

22

Section IVMOVEMENT

■ 27. General.—lt will usually be impossible to conceal largemovements of troops or supplies in the desert, except nightmovements during the dark of the moon. While heavysandstorms will conceal troops from observation, these stormsalso make movement over any but the shortest distances verydifficult (see par. 12). Because of the difficult driving con-ditions and navigation difficulties, movements have beenhabitually made during the hours of daylight, except whenin close proximity with enemy ground forces. Since thereare almost no roads and but few good desert tracks exist,movement will usually be across country. Desert conditionspreclude the movement of troops on foot except during actualcombat. The necessity for dispersion makes movement byunits larger than a battalion very difficult to control. Bat-talions should normally stay within visual distance of adjacentunits.

■ 28. Movement During Daylight.—a. Combat vehicles andpersonnel carriers must move in a dispersed formation be-cause of the constant danger of air attack. The formationmust be irregular, the vehicle echeloned and dispersed bothin width and in depth. Intervals and distances must neverbe less than 100 yards and must be increased to 200 or 300yards when enemy air forces are active. The same dis-tances and intervals that are maintained during the marchmust be kept during daylight halts. Lines of vehicles mustbe avoided, both when moving and at a halt. Movementsof combat vehicles should be protected from hostile groundforces by a covering screen of fast-moving armored vehiclesto the front, flanks, and rear. These security troops mustinclude antitank and antiaircraft weapons capable of imme-diate action. (See sec. VJ.)

b. Trains must move in a dispersed formation similarto that adopted by combat vehicles and personnel carriers.Protection should be provided by attaching combat vehicles,Infantry in personnel carriers, and antitank and antiaircraftweapons. The strength of such protective forces will begoverned by the situation. The vehicles of this protective

27-28 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

23

force should move at the front, flanks, and rear of the for-mation. Antitank and antiaircraft weapons should normallymove on the flanks, disposed in depth.

c. An average speed of from 15 to 20 miles an hour, de-pending on the terrain, can usually be maintained for shortmovements in a dispersed formation during daylight hours.Supply convoys do not usually exceed a rate of march ofabout 10 miles per hour for trips of more than 25 miles.■ 29. Night Movements.—Movements at night should bemade without any vehicular tactical or night driving lights.Smoking and the use of flashlights must be forbidden. Ifthe moon is bright, march formations similar to those usedduring daylight should be used. When night movements aremade during the dark of the moon, units should be formedin small columns of 15 or 20 vehicles, with columns travelingabreast. Distances usually should not exceed 5 yards betweenvehicles and intervals should be about 10 yards betweencolumns. Maximum speed must be reduced to 10 miles perhour or less, depending on the visibility and terrain. Anti-tank and antiaircraft weapons should be in the flank col-umns. In train movements the escorting vehicles shouldmove at the head of each column and on the flanks of themarch formation. (See sec. VI.)

■ 30. Movements on Roads.—Such movements will be un-usual in desert operations. Where roads do exist and whenthere is no threat of hostile ground attack, movements maybe made in column. A vehicular density of 10 to 15 vehiclesto the mile should be maintained. Greater density will offerexcellent targets for air attack; lesser density will result inloss of control. Antiaircraft protection must be providedand should take position on the flanks of the column in theevent of air attack. Antitank weapons should cover possibleapproaches of hostile armored vehicles.■ 31. Navigation.—The almost complete absence of roads,trails, and landmarks in the desert makes it necessary touse special equipment and methods for maintaining direc-tion and for locating positions. Maps are of value primarilyas charts from which the magnetic bearings for movementsare determined. As installations are established in a given

area the locations are plotted by coordinates on the map.

28-31DESERT OPERATIONS

24

The bearing of a desired movement is then determined fromthe map by protractor. The methods used for navigatingwill depend upon the type of the terrain to be traversed, theknowledge of the area in which the movement is to be made,and the length of the march to be taken. Various provenmethods are indicated in the following paragraphs.

■ 32. Magnetic Compass.—ln making short moves whenvisibility is good, a course may be laid by magnetic compassand odometer. Such a course must be checked frequently,will be quite inaccurate, and will result in a slow rate ofmarch since the compass operator must stop his vehicle,dismount, and move away from the vehicle so that it willnot influence his compass. The bearing of the desired courseis determined from the map by protractor. Using a com-pass, the leader’s vehicle is turned until its long axis ispointed in the proper direction and the odometer readingis noted. The driver picks out some object or location tohis front and drives to it where the move is plotted on themap and the procedure repeated.

■ 33. Predetermined Course with Sun Compass.—This isthe simplest method of navigation over any considerabledistance. A map and protractor, sun compass, accurateodometer, two accurate watches, and an almanac are required.The desired direction is determined by the map and pro-tractor (or the prismatic compass). The sun compass iscorrected for the date, sun time, and latitude of the startingpoint, the vehicle turned until the shadow of the pointerfalls along the shadow needle and the vehicle is on the correctbearing. The odometer reading is noted. The shadow needlemust be corrected every 15 minutes to maintain the course.The principal objection to this method is the reluctance toalter a course once set, with the consequent tendency todrive straight through areas of bad going instead of makingdetours around them. In sand dune or in rocky areas itis impossible to hold to a straight course for any considerabledistance.

■ 34. Dead-reckoning Navigation.—This is the most usefulmethod for all movements and is the only satisfactory methodso far developed for movement over long distances or in un-known terrain. It requires a good sun compass which indi-

31-34 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

25

cates directly and continuously the bearing on which thevehicle is travelling, no matter what that bearing may be,and which will permit readings to be taken by the eye alone,Without requiring any part to be set by hand whenever areading is desired. The general direction of movement isplotted with map and protractor. The commander is freeto pick his route over the best terrain as he goes along. Thenavigator notes the compass reading for each change indirection and the odometer readings and plots the actualcourse followed on the map or a chart. Errors in a courseplotted by dead-reckoning, by an experienced navigator usingthe above method, should not be over 3 percent in distanceand 1 Vz ° in bearing.

■ 35. Position-Finding.—Since navigation errors are liableto accumulate from day to day, it will be necessary, on longmarches, to take astronomical fixes of the position each night.This requires a sextant or theodolite, radio time receiver,two reliable watches, an almanac, navigation (mathematical)tables, and plotting equipment.

■ 36. Night Navigation.—Magnetic compasses are ordinarilyused for night navigation. Some sun compasses can beadapted to night navigation when the moon is bright. Ingeneral, less accuracy is expected in night navigation thanin daylight. One method widely used with a magnetic com-pass has been to take the magnetic bearing of a low starand drive on it, rechecking every 15 minutes if the star isgenerally in the north or south and every 30 minutes for onein the east or west.

■ 37. Other Navigating Instruments.—Magnetic aerocom-passes have been tried for desert navigation by dead-reck-oning. The difficulty of compensatingsuch compasses againstthe errors introduced by the vehicle, its moving steel parts,and the movement of metallic loads and of weapons has,up to the present, made them too uncertain for long move-ments over unknown country. Magnetic compasses are notusually dead-beat (nonoscillating) as is a sun compass, andthe constant shifting of the needle makes accurate readingof a course bearing extremely difficult when the vehicle isin motion. A gyroscopic compass is dead-beat but must be

34-37DESERT OPERATIONS

26

corrected every 10 minutes or so for precision. This correc-tion must be made from the magnetic compass and will usu-ally require the vehicle to be stopped because of needlefluctuation. In addition, it does not eliminate the difficultyof accurate magnetic compass adjustment discussed above.Further development may eliminate the difficulties hereto-fore encountered. Provision of a suitable compass of thetype used in air navigation will increase the rate of marchwhich is now held down by navigation difficulties.

■ 38. Navigators.—Every officer and noncommissioned officerof a force intended for desert operation must be able tonavigate with magnetic and sun compasses and odometer.Every unit which may be called upon to operate independ-ently must have one and preferably two navigators who aretrained and equipped to determine position by astronomicalmeans. (See par. 35.) Each member of a patrol shouldhave an oil prismatic compass and map on his person. Heshould know how to use his compass, note bearings and dis-tances, plot with protractor and scale, and should know theodometer correction of his vehicle. (See par. 32.) It mustbe remembered that unit trains will frequently be requiredto navigate to and from supply installations, and sufficienttrained personnel will be required to direct their movements.

Section V

CAMPS AND BIVOUACS

■ 39. General.—ln camps and bivouacs, as in movement,dispersion is the primary means of protection against airattacks. During daylight hours there is a constant threat ofair attack and, in forward areas, of ground attack from anydirection. At night the threat of air attack is considerablyreduced but the danger of ground attack, particularly raids,is increased. Maximum use must always be made of camou-flage. (See sec. IX.)

■ 40. Daylight Bivouac. —During the hours of daylight unitsshould form a dispersed bivouac. Vehicles should be dis-posed in generally the same manner as when moving duringthe day. Intervals and distances may be still further in-creased for protection against air attack. (See par. 28.)

37-40 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

27

Care must be taken to avoid lines of vehicles. An all-arounddefense should be maintained and patrols, with suitablemeans for communication, sent well out to give early warn-ing of hostile ground threats. Artillery, antitank, and anti-aircraft weapons must be placed in position and manned atall times. Slit trenches should be dug for all personnel.

■ 41. Night Bivouac.—The following methods have been de-veloped by troops now engaged in desert warfare. When ahalt is made for the night, units the size of a battalion forma close bivouac. Vehicles form a triangle or square, withall vehicles facing in the direction in which they are to movein the event of a night alarm. The subordinate units occupya leg or side of the bivouac formation with 10 to 15 yardsbetween vehicles. Trains should be brought forward afterdark and moved inside the triangle or square. If trains haveto form a close bivouac without protection from their ownunit, the train defense vehicles (see par. 28) form an outercircle within which the supply vehicles take up an irregularformation.) Night listening posts are established at sufficientdistance from the bivouac to give warning of ground attack.Communication should normally be by wire or messenger be-cause of the necessity for radio silence. Frequently it willbe advisable to patrol between listening posts. Before dawnthe trains should move out of bivouac and take up open for-mation to the rear. At dawn the unit establishes an open(dispersed) bivouac, adopts the dispersed formation formovement, or the prescribed formation for combat. Whenthere is no danger of an attack by hostile ground forces theopen bivouac formation is used both day and night for airprotection. Separate organizations smaller than a battalionadopt formations similar to those of the battalion. Unitslarger than a battalion should not form a close bivouac.■ 42. Security Measures in Bivouac. —Whenever a unit goesinto bivouac, plans and preparations must immediately bemade to move out if the necessity arises. The ground inthe vicinity of each unit is reconnoitered so that units canmove out without confusion. Vehicles are headed in thedirection of movement, are serviced, and supplies are issued.Slit trenches are dug for cover, air lookouts posted, and allantiaircraft weapons constantly manned. Antitank weapons

40-42DESERT OPERATIONS

28

and machine guns should be so sited along the perimeter of aclose bivouac as to cover adequately all possible approaches.Lights necessary for administration, maintenance, or cook-ing after dark must be carefully concealed from air or groundobservation. Radio silence should be observed for at leasta half hour before going into bivouac and during the hoursof darkness except in an emergency. Close bivouacs areusually formed about dusk. If there is any danger of beingobserved from the air or ground, close bivouac should notbe established until after dark. If a bivouac has beenestablished during daylight hours it should be moved afterdark. Troops in contact with the enemy, in static position,normally form close bivouac by company or battery duringthe night, securing the bivouac with listening posts andpatrols.

■ 43. Camps.—lt will be impossible to conceal the existenceof camps of a permanent or semipermanent nature. Pro-tection of such installations will normally be gained by dis-persion over such a large area that air attack directed atthe whole installation will be unprofitable and by the use ofdummy installations. Camouflage and camouflage disciplinemust be used to insure the concealment of the more im-portant locations, such as command posts, telephone centrals,etc., from possible point attack. Roads should be clearlymarked and military police must control traffic. No vehicleshould be permitted to approach closer than 300 or 400 yardsto a command post or similar installation. Vehicle parkingareas should be concealed and dispersed.

■ 44. Shelter.—ln bivouac, individuals And shelter in ve-hicles, in tents, in slit trenches, or in dugouts. Except in thewinter along a coast line, rain usually will not be encounteredin the desert, hence sleeping bags may be used on the openground. Shelter will be needed from the wind, particularlyin the winter. Tents should be dug in and camouflaged.Where positions may be occupied for relatively long periodsof time, dugouts should be constructed for shelter. Com-mand vehicles must be provided with lightproof shelters,preferably capable of extension to the sides to provide suffi-cient working space. Slit trenches must always be dug toprovide cover in the vicinity of the shelter.

42-44 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

29446597°—42 5

Section VIRECONNAISSANCE AND SECURITY

■ 45. General.—The almost complete freedom of maneuverin the desert, generally limited only by supply considerations,demands all-around security measures and aggressive andcontinuous reconnaissance. Air reconnaissance during day-light hours, unless conditions of haze or sandstorms exist,should discover the movements and locations of large forcesin sufficient time to prevent surprise. It will, however, bedifficult to discover from the air small patrols and raidingparties which use hit-and-run tactics. These must be soughtout by ground patrols. In order that full advantage maybe taken of freedom of maneuver the ground must be care-fully reconnoitered to insure that movement is made throughthe most suitable areas. Failure to execute tactical groundreconnaissance has frequently resulted in armored forcesbeing decoyed into antitank ambushes with disastrous re-sults. While danger from hostile mine fields will frequentlyprohibit night movements in areas which have been in thehands of the enemy, the same mine fields will not preventthe enemy from moving at night. Therefore it is vital thatnight bivouacs be secured against hostile action.

■ 46. Security.—-a. During daylight.—Security is providedby adopting a dispersed formation during movement andat halts, and by the use of patrols to the front, flanks, andrear. (See par, 28.) Surprise attack by ground forces ispractically impossible if adequate reconnaissance measuresare taken. The threat of hostile air attack is always presentand antiaircraft lookouts must be posted, antiaircraft weap-ons manned at all times, and an adequate warning systemestablished.

b. At night.—Movement of large forces will be difficultat night. It should not be attempted unless a protectivescreen has been established during daylight around the areathrough which the movement is to be made, routes havebeen reconnoitered and marked, and guides provided.Night bivouac areas should be occupied after dark to preventair attack and the formation adopted should be a closebivouac unless there is no danger of raid by ground forces.

45-46DESERT OPERATIONS

30

(See par. 41.) Security of a night bivouac is obtained bythe close formation, the siting of defensive weapons on theperimeter, the use of all-around listening posts, and nightpatrols. Sound carries very well at night and listening postswill normally provide adequate warning of hostile raids. Theoperations of security patrols at night will require carefulcoordination with the listening posts in order that the patrolswill not confuse listening posts with resulting false alarms.Patrolling should be intensified before daylight to assure safemovement to the dispersed daylight formation. (See par.28.) Slit trenches should be dug for cover against groundattack. Security from air attack is provided by light dis-cipline, radio silence, and plans for dispersal in the eventof air attack.

■ 47. Ground Reconnaissance. —Highly mobile patrolsequipped with radio and armed with suitable weapons forprotection against armored and air attack should be usedfor ground reconnaissance. Each patrol must be preparedfor all types of desert navigation (see sec. IV). Patrolsshould never have less than two vehicles in order to pro-vide against vehicle break-down. Normally personnel usedfor this duty should be specially trained.

■ 48. Day Patrols. —a. These patrols must be mounted invehicles capable of high speed in order to extricate them-selves from any sudden attack by superior forces. Pastarmored vehicles are particularly well suited for day patrols.Antiaircraft and antitank weapons and radio communicationare essential. Among missions for day patrols will be thefollowing:

(1) To maintain contact with the enemy and to report hismovements, composition, and disposition.

(2) To observe and report the enemy’s tactics, methods,formations, employment, and types of transport.

(3) To locate hostile defense positions, gun and machine-gun posts, wire, mine fields, and other obstacles.

(4) To collect identifications such as measurements oftrack and wheel marks, letters and documents, and piecesof uniform and equipment.

(5) To obtain thorough information of the terrain for itsfuture tactical use.

46-48 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

31

b. Day patrols are very vulnerable to air attack. Constantlookout must be maintained for hostile air attack. A widelydispersed formation must be used. Halts should be madeon ground most suited for concealing vehicles and maxi-mum use made of camouflage. When attacked from the air,the personnel should scatter away from the vehicle and fireat the attacking airplanes. Aircraft always attack thevehicle. In static situations, patrols must avoid habituallyfollowing the same route in order to protect themselvesagainst ambush or mine fields laid overnight.

■ 49. Night Patrols. —a. Night patrols are essential in thedesert both for security and reconnaissance. Such missionsare best performed by motorized Infantry. Armoredvehicles are generally unsuitable for night missions. Theoperations of a night patrol will usually entail an approachmarch by motor to a detrucking point and an advance onfoot toward the objective, the close reconnaissance or pene-tration and assault of the objective, and finally the with-drawal of the patrol to the entrucking point and a returnmarch. The strength of a night patrol must be sufficientto provide protection for the vehicles at the detrucking pointin addition to the troops necessary to accomplish the dis-mounted mission.

b. Night patrols in the desert demand excellent physicalcondition and a high degree of training on the part of thetroops used. Patrols may be required to cover considerabledistances on foot during the night, lie still for long periodsclose to enemy positions, and operate under extremes ofheat and cold. The accomplishment of such a missiondemands—

(1) Careful organization of the patrol and study of allinformation of the terrain to be covered.

(2) Accurate navigation both while in vehicles and on foot.(3) Ability to negotiate difficult terrain rapidly and silently

and to maintain formation.

■ 50. Distant Ground Reconnaissance. —Because of thegreat areas involved and the almost total absence of majornatural obstacles to movement, desert operations permit theeffective use of ground patrols operating over distances ofhundreds of miles from their bases. Patrols used for this

48-50DESERT OPERATIONS

32

purpose must be specially organized, equipped, and trained(see app. II). Their missions will include the obtaining ofdetailed topographical information, discovery of hostilemovements or other activities in distant areas, and raidsfor the destruction of supply dumps, harassing supply col-umns, and diverting hostile forces to protect isloated postsand lines of communications.

Section VII

COMBAT

■ 51. Characteristics.—Because of the conditions found indeserts, combat in such terrain is marked by the followingcharacteristics:

a. Forces have almost complete freedom from those re-strictions on mobility normally imposed by natural tacticalobstacles. Hence, maneuver and all-around protection areemphasized, and the maximum use of motor transportationis possible.

b. The scarcity of roads and railways increases supplydifficulties and limits the radius of action of mechanized andmotorized forces.

c. The almost total absence of natural concealment, otherthan that provided by haze or mirage increases the impor-tance of dispersion and deception.

d. The absence of good landmarks reduces the value ofmaps, necessitates accurate navigation by use of compass, sun,and stars, and increases the difficulties of controlling maneu-ver and of cooperation between various arms and differentunits.

■ 52. Maneuver.—Ultimate success in battle in the desert willgenerally be dependent upon the success of the armored ele-ments. Quick and flexible maneuver of armored and motor-ized units is essential to exploit fully enemy weaknesses andmistakes, and bring full fire power to bear on the enemyunder the most favorable conditions. Quick and flexiblemaneuver requires use of the most suitable formation, main-tenance of direction, and correct use of speed and ground.

■ 53. Formations.—Formations must be adapted to securerapid movement and protection against surprise. There is

50-53 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

33

a constant struggle between dispersion and control. The everpresent threat of air attack makes a dispersed formationessential, yet the greater the dispersion the greater the diffi-culty of control. The basic unit for the movement of Ar-mored Forces or motorized Infantry is the battalion. Inorder to control this unit the development of battle drill isessential. In a dispersed formation, change of direction andchanges of position of subordinate units are very difficult. Toassist in such actions commanders of all units should marchwell forward, and all vehicle commanders and drivers mustbe thoroughly familiar with the signals and the types ofmaneuver which may be used.

■ 54. Maintenance of Direction.—Navigation is always diffi-cult. Constant training of navigators for all units is neces-sary. Bearings for the direction of movement are given be-fore the movement starts. Changes of direction are verydifficult to make in a dispersed formation. Practice in battledrill is the only method by which the necessary flexibilitywill be developed.

■ 55. Speed.—Proper use of speed is essential for success.Driving beyond the economical speed of the vehicles must beavoided. Past driving of vehicles will result in frequentmechanical failures and in high wear and tear on vehicles.High rate of movement is obtained by intelligent anticipa-tion by commanders, by good judgment in the use of ground,and by good driving. Commanders of all echelons must an-ticipate the possible employment of their commands andmake early readjustment in the disposition of their subordi-nate units in order that they may be quickly employed whereneeded. While the ground in the desert is relatively openand flat, there will always be areas of good going and badgoing. The commander’s intelligent use of ground for maneu-ver may frequently force the enemy into using rocky or otherpoor ground, while comparatively good ground conditionsare used by the commander’s own troops. Such use of groundrequires taking every opportunity for personal reconnais-sance, and the development of a keen and quick eye fordesert terrain in order to select ground which is especiallysuitable for fire action and for the employment of reserves.The importance of good driving cannot be overemphasized.

53-55DESERT OPERATIONS

34

The individual driver’s ability to keep his place in the forma-tion and to get his vehicle to the proper place at the propertime without exceeding the economical speed of his vehiclewill often be vital to success in combat.

■ 56. Security (see sec. Vl).—Since the enemy has equalfreedom of maneuver, all-around protection is necessary atall times. Lack of concealment permits the use of smallerunits for advance, flank, and rear guards than are requiredin less open terrain. Formations and the disposition of unitsmust permit entry into action in any direction.

■ 57. Radius of Action.—The supply difficulties which at-tend desert operation, due to lack of roads and railways, andthe use of motor vehicles limit operations to the available fuelsupplies. The problems of supply are discussed in section X.While lack of obstacles permits free maneuver; the radiusof such maneuver is definitely limited by the fuel supply.Since fuel consumption varies with the type of ground tra-versed and with the continuity of movement, frequent peri-odic checks on the amount of fuel on hand are necessaryduring operations.

■ 58. Lack of Concealment.—The surprise which conceal-ment permits in other terrain cannot be counted on indesert combat. Even with air superiority it will rarely bepossible to eliminate all hostile air observation. Reservesshould be so located that they will be readily available whenneeded and maximum use made of their mobility to deceivethe enemy as to their composition as well as place of employ-ment.■ 59. Liaison.—The absence of good landmarks presentsdifficulties in cooperation between different units and arms.Training must develop the maximum use of visual signals,pyrotechnics, and other visual means of identification of unitand target locations. Liaison between all units and servicesmust be highly developed.

Section VIIIARMS AND SERVICES

■ 60. General.—a. Combat experience in rolling or flat desertareas indicates that all arms and services must be provided

55-60 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

35

with motor transportation. Although foot troops are em-ployed in defensive positions or fortified localities, in closecontact with and in the assault on hostile defensive posi-tions, and in mopping up and exploiting areas which havebeen overrun by armored units, the foot troops must bebrought to the areas of these operations by motor. Other-wise, hampered by the difficult footing, the heat, and thelack of water, they may arrive too late or so fatigued as tobe unfit for combat. The lack of concealment and covermakes slow-moving foot troops lucrative targets for hostileair and armored forces.

b. Operations in mountainous desert areas require specialtransportation facilities. From such knowledge of theseareas as is now available, few if any roads and only a limitednumber of trails exist. Because of the difficult terrain con-ditions and the lack of water, operations probably will belimited to native troops and specially selected task forces.The composition and strength of such forces will be influ-enced primarily by water supply.

■ 61. Infantry.—ln the attack. Infantry will generally havethe subordinate role of supporting the operations of ar-mored units. Infantry attacks have little hope of successin bare, open desert terrain unless there are present at leastsome of the following favorable conditions: supporting tanks,overwhelming supporting fires, close support combat aviation,and darkness, smoke, or dust storms. The open desert placesa premium on the speed, the shock, and the fire power of thearmored vehicle. Infantry moves by motor; it supports thearmored action by executing reconnaissance, by protectingassembly, refueling, and bivouac areas and the passage ofdefiles (that is, escarpments, extremely rough ground, softsand, and salt marshes which frequently restrict the move-ment of mobile forces). Infantry may be used to establishbridgeheads through mine fields, tank traps, and other ob-stacles to armored unit operations, and to follow closely thearmored attack to hold the ground gained, to mop up remain-ing hostile forces, and to exploit the success achieved. Itmay be used to protect or escort the supplies of armoredunits. In combination with other forces it may be employedin pursuit to block routes of retreat at defiles or other crit-

60-61DESERT OPERATIONS

ical terrain while armored elements complete the destructionof the trapped enemy. The Infantry must be amply pro-vided with antiaircraft and antitank guns and be reinforcedwith artillery and engineer troops.

■ 62. Daylight Reconnaissance. —Since enemy air and ar-tillery action will be most effective and hostile armoredvehicles will probably be operating during daylight, mobileground reconnaissance for the main forces will normallybe executed by armored patrols. In many situations, observa-tion posts manned by Infantry must be operated duringdaylight hours. Such posts may be established to advantageprior to daylight and withdrawn either during the middaymirage or after dark. When these posts are established thepersonnel must dig cover and conceal their vehicles. A con-siderable distance will often have to be traversed on foot totake full advantage of the ground and to prevent the soundof the vehicles from disclosing the location of the post. Somepersonnel must always remain with the vehicles to protectthem or to permit rapid get-away should that become neces-sary. These posts must have adequate signal communicationfacilities to their supports or main bodies. It may frequentlybe possible to set up forward radio stations connected byremote control or by telephone or runner to one or moreobservation posts. When runners are used, covered routesshould be available for their movement. Specially equippedand trained motorized Infantry may be used for long-rangeground reconnaissance. (See app. II.)

■ 63. Night Reconnaissance.—Reconnaissance at night willbe a most important infantry task. Such a mission will fre-quently require movement by motor and on foot. Thestrength of reconnaissance units for these missions must besuch as to assure protection of the vehicles during the opera-tions of the dismounted personnel. (See par. 49.)

■ 64. Defense and Delaying Action.—Motorized infantryunits, heavily reinforced with artillery and antitank guns,will be particularly well adapted to defense and delayingaction because of their great automatic fire power and thespeed with which reserves can be moved to reinforce anythreatened point. Depth in defense is not so important unlessa protracted defense is indicated. A defensive line taken up

61-64 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

DESERT OPERATIONS 64-65

with the primary purpose of checking hostile armored andmotorized columns should always, if possible, be based on anatural or artificial tank obstacle. This will permit a muchlonger line to be held. A short line is of little value againsthighly mobile forces as it will be speedily and inevitably out-flanked. When a long line is occupied, it will usually befound possible to concentrate the bulk of the antitankweapons on the most likely approaches and to observeand patrol areas which are less suitable for armored vehicles.Although such a line, particularly with artillery support,can impose considerable delay during daylight, it will be ofsmall value at night against an enemy who may be able tobring up Infantry to reconnoiter and attack the position.At night close bivouac should be formed and positions organ-ized which command the most likely enemy approaches.

■ 65. Protection.—a. General.—lnfantry will be required toprotect itself and other forces at the halt, on the march, byday and by night. By day the force protected and its escortshould move or halt in a formation which provides well-con-trolled dispersion, thus giving the enemy a difficult targetto engage whether from the air or ground, and giving thecommander an opportunity to maneuver at speed and therebyavoid engagement with superior enemy forces. Since attacksmay come from the air or from any direction on the groundthe protective measures taken should provide—

(1) Air sentries and ground patrols, both with adequatesignal communication so as to give early warning of animpending attack.

(2) A mobile reserve at the immediate call of the com-mander to engage enemy attacks.

b. Air attack. —For protection against air attack the fol-lowing measures are necessary:

(1) An air sentry in every vehicle on the move, and asrequired at the halt.

(2) Dispersion of vehicles in width and in depth. Whenmoving across country or when halted in daylight, intervalsand distances of from 100 to 300 yards between vehiclesmust be maintained. Personnel must remain dispersed ata halt.

(3) All antiaircraft weapons must be constantly mannedand ready to open Are. Location of antiaircraft weapons

38

BASIC FIELD MANUAL

at the front, flanks, and rear of the formation will be mosteffective, providing the entire area occupied can be coveredby some or all of the weapons.

(4) Strict discipline must be maintained as to lights anddirection and rate of movement. Dust raised by rapid move-ment may disclose vehicles which otherwise would be un-noticed. On roads, movement should be as rapid as isconsistent with driving safety in order to reduce the timespent in the danger area. Antiaircraft weapons should, whenpossible, protect such movements from positions on the flankand not in the column.

c. Night.—For administration and protection some degreeof concentration is usually necessary at night. No matterwhat the formation, plans must be made for complete all-around defense, adequate ground patrols and listening posts,and for the rapid resumption of movement. All troops musthave definite alarm positions suitable for both air and groundattack. Indiscriminate firing at night must be avoided as itdiscloses the position to enemy aircraft and to ground patrols.All troops must be impressed with the relative ineffectivenessof fire at night, owing to the fact that aim cannot be takenin the dark. Night firing is often more dangerous to friendthan to foe. Hostile combat patrols, once they have gainedaccess to a close bivouac, will attempt to create confusionand cause uncontrolled firing to cover the accomplishmentof their missions.

■ 66. Armored Forces.—a. General.—The lack of natural ob-stacles to movement makes desert terrain most suitable forthe use of armored forces. The final decision in a desertcampaign will depend upon the success of the armored ele-ments. The composition and action of other arms andservices is of importance to the degree in which they areable to contribute to the success of the armored elementsof the command. (See par. 69c.)

b. Battle maneuver. —Lack of concealment will make it rel-atively impossible to hide the presence of armored units.All forces operating in the Libyan Desert have made greatuse of camouflage to make armored vehicles appear to beother types of vehicles. They have also made considerableuse of dummy tanks. Surprise in armored operations canbe gained sometimes by night movements but primarily by

65-66

39

the use of the speed and mobility of the tank. In orderto make full use of these factors, battle maneuver must bedeveloped. The necessity for dispersion makes control diffi-cult. Constant drill and maximum efficiency will be requiredin the use of radio and visual signals in order to developin all personnel the familiarity with signals and types ofmaneuver necessary.

c. Replenishment.—Tank action in present desert opera-tions has made refueling and replenishing of ammunitionduring intervals between tank actions vital to success. Thespeed necessary to accomplish these tasks effectively will onlyresult from perfect teamwork on the part of both tank crewsand the personnel of supply vehicles, developed by carefultraining. Dispersion must be maintained during this opera-tion. Expert navigation is a necessity to assure all vehiclesarriving at refueling areas.

d. Recognition.—Failure to identify tanks has resultedboth in the loss of many tanks by the action of friendly air,ground, and other tank forces, and in losses inflicted onfriendly ground troops by their own tanks. Flag recognitionsignals have proved inadequate because of the great cloudsof dust and sand which usually envelop a tank during move-ment. A simple visual signal code, to be given when calledfor, using Very lights or colored smoke, is a necessity. Sucha code must be capable of frequent variation.

e. Recovery.—An efficient recovery system must be de-veloped. German armored forces operating in the LibyanDesert have their recovery crews accompany the tank ele-ments at all times and recovery is normally started duringa tank battle. Consequently, they have been unusually suc-cessful in returning a large percentage of vehicle casualtiesto operating condition within a relatively short period oftime.

/. Artillery support.—Armored artillery, preferably self-propelled, should accompany the armored forces. The greatimportance of artillery support in tank action has beenproved in all operations in the desert. Prior to the tank-versus-tank action its missions will include denial of certainareas to hostile tanks, antitank fires, fires which deceive theenemy as to the direction of attack, blinding observationby smoke, and counter battery fires. During a tank-versus-

66DESERT OPERATIONS

40

tank action the principal artillery mission will be counterbattery fire and interference with movement of hostile re-serves and with hostile replenishment efforts. Armoredartillery must have protection by motorized Infantry.

g. Organization.—The operations which have taken placein the Libyan Desert during the present war have involveda comparatively small number of troops which have hadrelatively great areas over which to operate. Under theseconditions the commanders of the highly mobile units, par-ticularly the armored units, have usually had the choice,limited only by the availability of fuel, of accepting or refusingcombat. As a result of these special conditions, both forceshave tended to increase the proportion of supporting troopsand reduce the number of tanks in a task force. (See

app. III.)

■ 67. Cavalry.—The lack of water prohibits the use of horsecavalry in the desert. Mechanized cavalry will be valuablefor the performance of reconnaissance and security missionsand in delaying actions. The reconnaissance and securitymissions for motorized Infantry can be executed by mecha-nized cavalry. (See par. 61.)

■ 68. Engineers.—a. Principal tasks.—The principal engi-neer tasks in desert operations will be the reconnaissance andremoval or destruction of antitank obstacles, development ofwater supply, destruction of disabled hostile armored vehiclesand, in withdrawal, of water supplies, the establishment oftransport and of port facilities, the construction of fortifi-cations, and road development.

b. Antitank obstacles. —The construction of antitank ob-stacles, particularly mine fields, is relatively easy in desertterrain. The sand permits easy digging and the wind causesthe sand to obliterate quickly all marks. Thorough and con-stant reconnaissance by engineers will be necessary duringthe preparations for an attack on any position which theenemy has had time to protect. Large mine fields can bereadily installed or shifted overnight. Engineer troops willbe necessary with any force attempting to establish a bridge-head through antitank obstacles prior to an armored attack.

c. Water supply.—(l) The most difficult and the most im-portant problem in desert operations is water supply. He

66-68 BASIC FIELD MANUAL

41

who possesses water supplies in the desert and is able todestroy his opponent’s is assured of victory. Engineer troopsmust be equipped to exploit to the fullest degree all pos-sible sources of water. Along the coast, distillation of saltwater will frequently be possible. Drills and pumps must beprovided for development of subsurface water and of oases.The necessity for dispersion requires the use of multiplewater-distributing points.